1. Introduction

Formative research constitutes a fundamental pillar in university education, fostering the development of scientific, technological, and reflective competencies from the early academic cycles [

1,

2]. In the field of health sciences, particularly in nursing education, it is essential to promote a sustainable research culture that prepares professionals capable of addressing social and health challenges based on scientific evidence [

3,

4].

In recently established institutions, such as emerging public universities in Latin America, this challenge is intensified by structural, territorial, and technological limitations that hinder access to active methodologies and innovative teaching resources. Therefore, it is necessary to implement accessible, contextualized, and sustainable pedagogical strategies that foster meaningful learning, critical thinking, and research autonomy from the early stages of professional training [

5,

6,

7].

In recent years, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been consolidated as a global priority framework. Goal 4 (SDG 4), focused on ensuring inclusive, equitable, and quality education, is particularly crucial for achieving sustainable development. This goal is closely linked to SDG 10, which seeks to reduce inequalities within and among countries [

7,

8]. In the educational context, this articulation implies ensuring that all students, regardless of their geographic, socioeconomic, cultural, or linguistic background, have access to meaningful and relevant learning opportunities [

9]. The incorporation of innovative pedagogical approaches—culturally and technologically contextualized—can help close educational gaps and promote equitable participation in vulnerable contexts [

10]. Thus, joint action on SDG 4 and SDG 10 supports progress toward more inclusive and resilient educational systems capable of responding to both local and global challenges of the 21st century.

This study proposes the application of the problem-solving method based on Pólya’s framework [

11,

12,

13] as an effective strategy for developing sustainable research competences. This strategy is complemented by a STEM educational kit developed in the Huancavelica region, designed to facilitate university learning through accessible technological solutions. This kit consists of thematic electronic boards and sensors that allow students to design technological solutions to real public health problems in their environment [

14].

The study was conducted with first-year nursing students at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Tayacaja Daniel Hernández Morillo (UNAT), a Peruvian public university with seven years of academic activity. Located in the Andean region, the institution faces challenges typical of emerging educational contexts, justifying the need to apply active methodologies using low-cost, high-impact resources. Through a quasi-experimental design and the development of contextualized technological projects, the impact of the intervention was analyzed in terms of strengthening research competencies and promoting a more equitable, technological, and sustainable education aligned with SDGs 3, 4, and 10 [

7,

15].

In this context, it is essential to promote strategies that integrate research training from the early stages of higher education. Formative research, understood as a process that connects learning with the production of knowledge, enables students not only to assimilate scientific foundations but also to apply research as a tool to solve real-world problems. In nursing programs, this approach is especially relevant as it focuses on community health issues that require contextualized, critical, and proactive responses.

Accordingly, this study aims to evaluate whether the implementation of a problem-solving method based on Pólya’s methodology and complemented with a STEM electronic educational kit contributes to strengthening the research competences of first-year nursing students at a public university in Peru. The pedagogical intervention was framed within formative research, addressing real community health problems previously identified. Activities were developed following the four phases of Pólya’s problem-solving method: understanding the problem, planning activities, executing the plan, and reviewing the solution. These were integrated with technological tools that facilitated the development of practical solutions, represented through functional models programmed using visual tools. This experience allowed for the hypothesis to be tested in a contextualized, sustainable, and meaningful educational environment.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Formative Research

From a pedagogical perspective, formative research is grounded in inquiry-oriented teaching methods and practices that have been implemented by faculty and universities with positive results. Strengthening this approach in higher education requires collaborative and interdisciplinary work that encourages the active participation of both faculty and students within a comprehensive and cross-cutting educational model in the university [

16]. This type of research contributes to the development of essential skills such as critical reading and academic writing, enabling students—even in technical fields like engineering—to produce academic work with the potential for publication in indexed journals [

17].

In this context, formative research is conceived as a teaching function with a clear pedagogical intention, developed within the curricular framework. It presents two distinctive features: it is led and guided by the teacher as part of their educational role, and it is carried out by students in training, rather than by established researchers. Its implementation requires a suitable methodological strategy, supported by scientific evaluation and continuous feedback, aimed at strengthening research competences from the earliest stages of university education, particularly in fields such as engineering and health sciences [

18,

19].

This approach promotes a teaching model based on active methodologies, in which the student plays a leading role in their own learning process. Through exploration and inquiry, it fosters a deeper understanding of knowledge while stimulating curiosity, critical thinking, and skepticism—essential pillars for the development of research competences [

1].

However, its implementation in the early years of university presents certain limitations. Since it takes place within the curricular framework and does not follow the rigor of formal scientific research, it is typically carried out over short periods, usually within a single academic semester. Furthermore, it is essential that the technological resources used—both hardware and software—are accessible and appropriate for the students’ cognitive level in order to effectively enhance learning and the development of research skills [

20,

21].

2.2. Problem-Solving Method Based on Pólya’s Proposal

The problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal is a pedagogical strategy adapted from George Pólya’s classical framework [

22], aimed at developing research competences in students through a structured process comprising four phases: understanding the problem, designing activities, implementing activities, and reviewing the solution [

12]. This approach combines active problem-solving methodologies with the use of accessible educational technologies, such as STEM educational kits, sensors, and visual programming environments [

11,

23,

24].

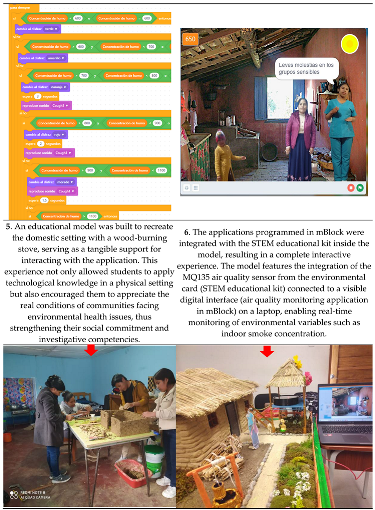

Figure 1 illustrates the phases of the method and the main activities associated with each stage.

The proposed method links scientific thinking with technological action. In other words, the student not only analyzes a problem situation, but also proposes, executes, and validates solutions through experimentation with technological tools, thereby developing functional products (such as models, prototypes, or applications). The following describes the research activities carried out in each phase:

Understanding the problem: involves the search for scientific and technological information, analysis of real-life situations, and visual representation of causes and effects through graphic organizers. This phase develops skills in observation, critical analysis, and the formulation of researchable questions.

Designing activities: focuses on planning research actions, reviewing background information, and logically structuring tasks. It fosters the ability to methodologically structure formative research.

Executing activities: students interact with technological tools such as sensors and actuators, programming their behavior using visual software like mBlock. This phase allows for active experimentation, application of technical knowledge, and reinforcement of collaborative work.

Reviewing the solution: the results obtained are verified, optimized, and reflected upon. Critical thinking, continuous improvement, and metacognition are promoted by evaluating the impact and relevance of the proposed actions in relation to the original problem.

This method is particularly relevant in fields such as Nursing, where learning must go beyond theoretical knowledge and promote the ability to respond to real-world problems. By linking the research process with concrete technologies, formative research becomes a meaningful, interdisciplinary, and innovation-oriented experience.

Various studies support its effectiveness, showing that such methodologies improve students’ attitudes toward research, strengthen logical thinking, and foster autonomy in learning [

25,

26]. Moreover, implementing the proposed method using STEM educational kits facilitates the acquisition of digital competences, which are essential for today’s professional training.

2.3. STEM Educational Electronic Kit

Currently, there are commercially available educational technologies, such as the Arduino board and its integrated development environment (IDE) based on the C++ language, which are widely used in education for the development of projects and technological activities. However, these solutions present limitations when applied to learning experiences focused on solving real-world problems in social contexts. In particular, they are not well-suited for students who are just beginning their university education, as their programming interfaces are not sufficiently intuitive or accessible for beginners. Furthermore, they lack hardware components (sensors, actuators, and specialized boards) specifically designed to address issues relevant to local or regional contexts [

27].

Therefore, the creation of customized hardware prototypes using boards like Arduino and ESP8266 has proven to be an effective alternative. These prototypes are not only cost-effective but also promote the development of skills such as abstraction, problem-solving, and algorithmic thinking. Previous studies have shown that such solutions can be as illustrative as commercial educational technologies and can be complemented by visual programming environments designed for teaching purposes [

26,

28].

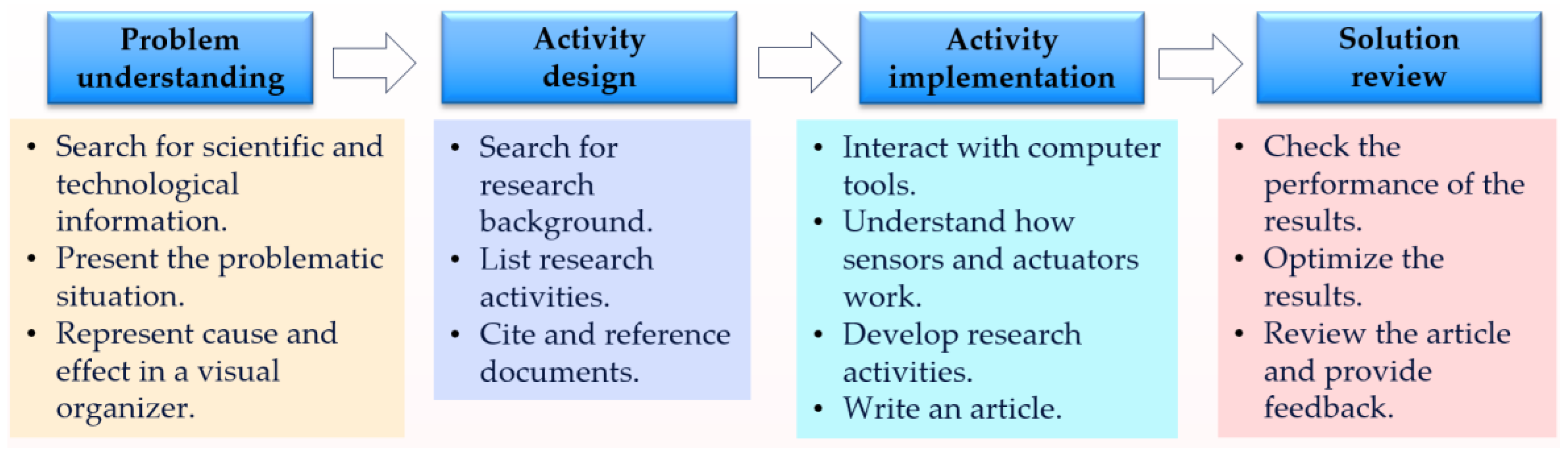

In response to the limitations mentioned above, a STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) educational electronic kit was designed and implemented. It consists of six themed electronic boards: agriculture, aquaculture, environment, health, education, and livestock [

14]. These boards are specifically designed to support the development of investigative activities related to real-world problems in regional contexts, incorporating relevant sensors and actuators for each theme [

29].

Interaction with the kit is carried out through a block-based visual programming interface developed on the mBlock platform, using libraries written in Python. This platform includes customized programming blocks that allow users to easily control the sensors and actuators on each electronic board. As a visual and intuitive environment, mBlock motivates students to design technological solutions in response to community-based challenges, providing immediate feedback throughout the process. This approach not only promotes the learning of programming but also encourages logical structuring of problems, creative thinking, and the practical application of knowledge in real-world contexts [

21].

Figure 2 presents the electronic boards included in the STEM educational kit and the visual programming environment based on mBlock used in its implementation.

2.4. Educational Sustainability in Health Sciences

Educational sustainability refers to the capacity of educational systems to adapt, innovate, and endure over time, ensuring quality, equity, and relevance across diverse contexts. In the 21st century, sustainable education involves not only access and inclusion, but also the development of enduring competencies that prepare students to face social, technological, and environmental challenges [

6,

7].

In the health sciences, educational sustainability is particularly relevant due to the dynamic and complex nature of healthcare systems. Sustainable educational models in nursing and public health aim to train students with research competencies, critical thinking, digital skills, and problem-solving abilities that can be continuously applied to improve healthcare delivery [

15]. These models promote interdisciplinary learning, evidence-based practice, and community engagement as essential pillars for developing resilient professionals.

Technological integration plays a key role in educational sustainability. Accessible, scalable, and context-sensitive technologies—such as STEM kits and visual programming environments—enhance student participation and autonomy, reduce learning barriers, and promote equity in education [

11,

30]. When these tools are integrated into active pedagogical frameworks, they strengthen both cognitive and socio-emotional dimensions of learning, making education more inclusive and sustainable over time.

Sustainable Learning in the educational field involves more than teaching about sustainability; it focuses on developing the capacities that allow students to engage in continuous learning and adapt to complex situations. This approach includes four key elements: renewal and relearning, both individual and collaborative learning, active participation, and the ability to apply acquired knowledge in various contexts. By integrating both practical and reflective educational methods, Sustainable Learning becomes a key strategy for strengthening and promoting lifelong learning competencies, which are essential for achieving sustainable development [

31].

The problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal and the STEM educational kit presented in this study align with the principles of sustainable education by fostering critical and technological competencies from the early stages of university education, with direct connections to the social needs of the students’ communities. This approach ensures that students are not only recipients of knowledge but also problem-solvers and active agents of sustainable development in their local environments.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Approach and Participants

This study employed a quasi-experimental design using a pretest–posttest approach, with a non-probabilistic, purposive sampling strategy under a quantitative framework. The participants were students enrolled in the course Information Management, part of the Nursing program at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Tayacaja Daniel Hernández Morillo, located in the Andes of Peru. All participants were in their first academic year and registered during the second semester of 2024. Most students were under 21 years of age, and the total number of participants was 64, consisting of 53 women and 11 men.

Data collection was conducted using a validated instrument that assesses research competencies within the framework of formative research, structured according to the phases of the problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal [

32]. The instrument includes 24 items distributed across four phases: understanding the problem (7 items), designing activities (5 items), executing activities (5 items), and reviewing the solution (7 items). Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 corresponds to “never,” 2 to “almost never,” 3 to “sometimes,” 4 to “almost always,” and 5 to “always.”

Table 1 presents the items of the instrument.

The instrument was validated by three international experts: a specialist in education, one in computer science, and another in computer engineering. In addition, its internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha statistical test, applied at three different times (2020, 2021, and 2022), yielding reliability coefficients of 0.957, 0.965, and 0.924, respectively, which demonstrates high reliability.

The instrument was administered at two points: before (pretest) and after (posttest) the pedagogical intervention in the classroom, with a total of 64 students.

Table 2 presents the distribution of items by phase of the problem-solving method and the internal consistency of the instrument for assessing research competencies (Cronbach’s alpha).

3.2. Proposal and Implementation of Formative Research Projects in the Classroom

3.2.1. Formative Research Projects and the STEM Educational Kit

Table 3 presents the Formative Research (FR) projects proposed to be developed in groups by nursing students under the guidance of the course instructor. Each project is linked to a health-related issue identified in the students’ local environment, which helps contextualize the research activity and make it more meaningful. Each group was assigned a specific card from the STEM educational kit, equipped with corresponding sensors, in order to carry out investigative activities using educational technologies.

For instance, in FR Project 1, the green card (agriculture) was used with a capacitive soil moisture sensor. In FR-2, the black card (environment) was combined with the MQ135 air quality sensor. FR-3 employed the yellow card (livestock) with the HC-SR04 ultrasonic sensor. In FR-4, the blue card (aquaculture) was used with the water turbidity sensor, while in FR-5, also with the blue card, the DS18B20 water temperature sensor was applied. Finally, FR-6 involved the red card (health) and the MLX90614 body temperature sensor.

All the electronic cards were programmed using the mBlock visual block-based programming environment, which facilitated interaction with the sensors and the development of contextualized technological solutions.

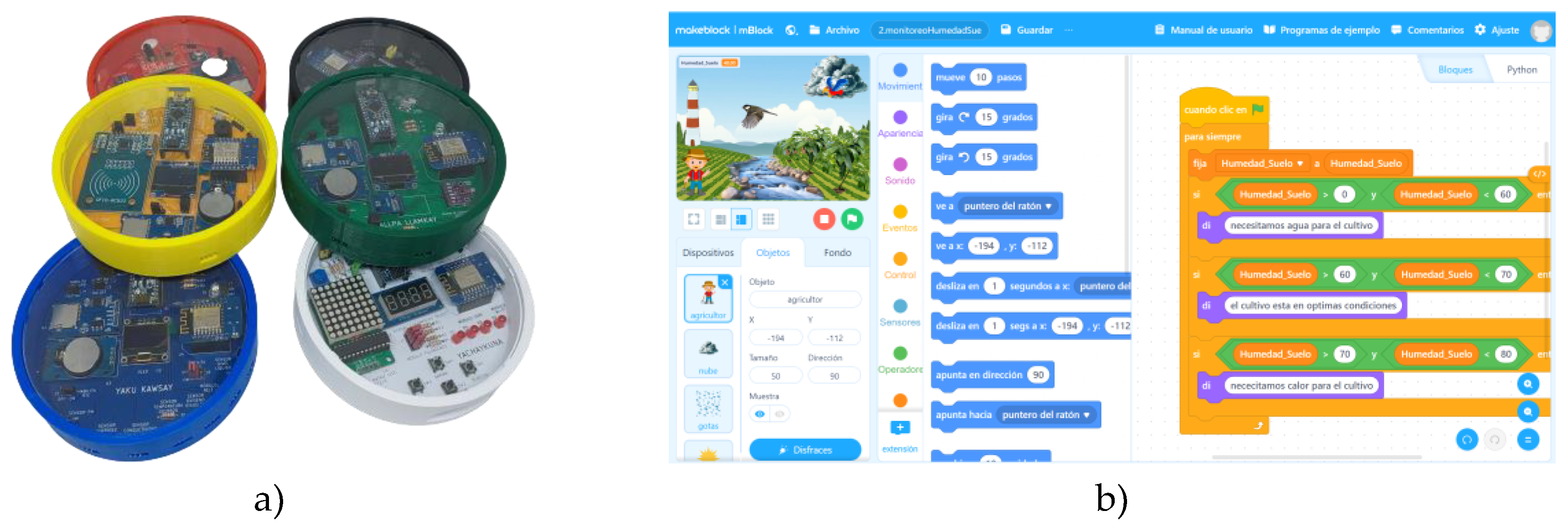

3.2.2. Development of Research Activities in the Classroom

Figure 3 shows the distribution of sessions and resources used during the educational intervention, based on the problem-solving method proposed by Pólya. The planning was organized around the four phases of the method: understanding the problem, planning activities, executing activities, and reviewing the solution. In each phase, specific technological tools were used: academic search engines (Google Scholar, Scopus, SciELO), artificial intelligence tools (ChatGPT), reference managers (Mendeley), visual programming platforms (mBlock), and the STEM educational kit (six electronic boards) with sensors.

The sessions were carried out over 16 academic weeks, progressively strengthening the research and technological competencies of nursing students. The research activities were conducted in the “Information Management” course, corresponding to the second semester of the Nursing program, with 4 hours per week over 16 sessions. These activities took place in the classroom, under constant supervision and continuous feedback from the instructor.

The following describes the activities carried out by the students, following the phases of the problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal: understanding the problem, planning activities, executing activities, and reviewing the solution.

Understanding the problem (5 sessions). In this phase, students carried out various tasks aimed at understanding the issue related to their assigned research topic. Among the main actions was the search for information using artificial intelligence applications (ChatGPT), academic search engines (Google Scholar, Scopus, SciELO), among others. Subsequently, students conducted a process of analysis and synthesis of the collected information, from which they prepared a descriptive sheet or page with scientific citations using reference managers (Mendeley) about the problem situation. In addition, they represented the cause-and-effect relationship of the issue using a visual organizer, which allowed them to better structure their ideas and achieve a deeper understanding of the proposed topic.

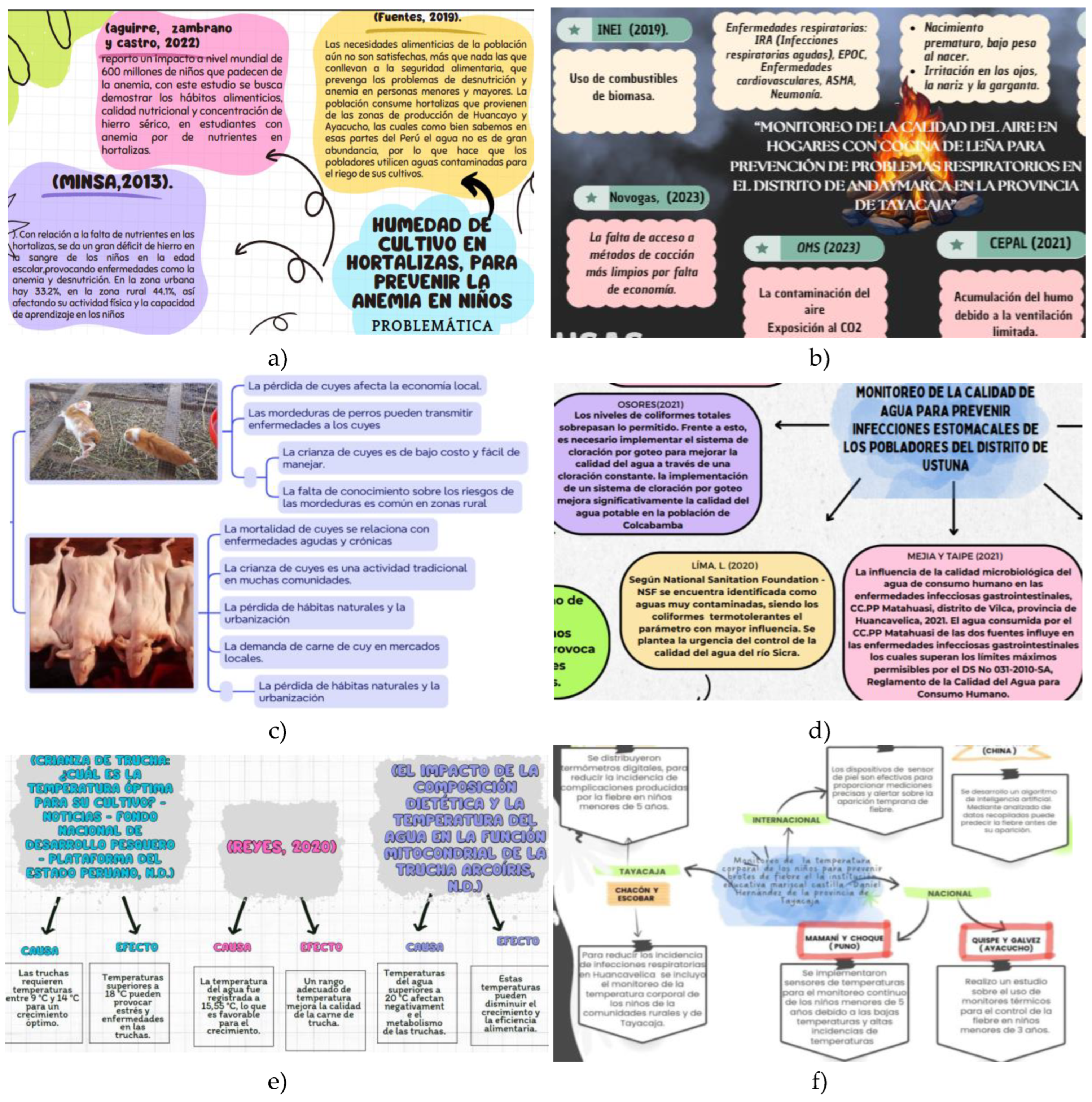

Figure 4 shows a sample of the diagrams developed, highlighting the visual representation of causes and effects related to the research topics selected by the students.

Designing activities (3 sessions). In this phase, students researched background information related to their selected research topics. To do this, they consulted various scientific sources such as Scopus, Google Scholar, among others. Once the information was gathered, they proceeded to analyze it and identify similar experiences or previously developed activities. Based on this analysis, they created a list of proposed actions aimed at offering viable solutions to the issues raised in each research topic. These activities were designed considering the local context, technical feasibility, and the use of the STEM educational kit.

Table 4 presents the set of activities proposed by the students according to the research topics developed in class.

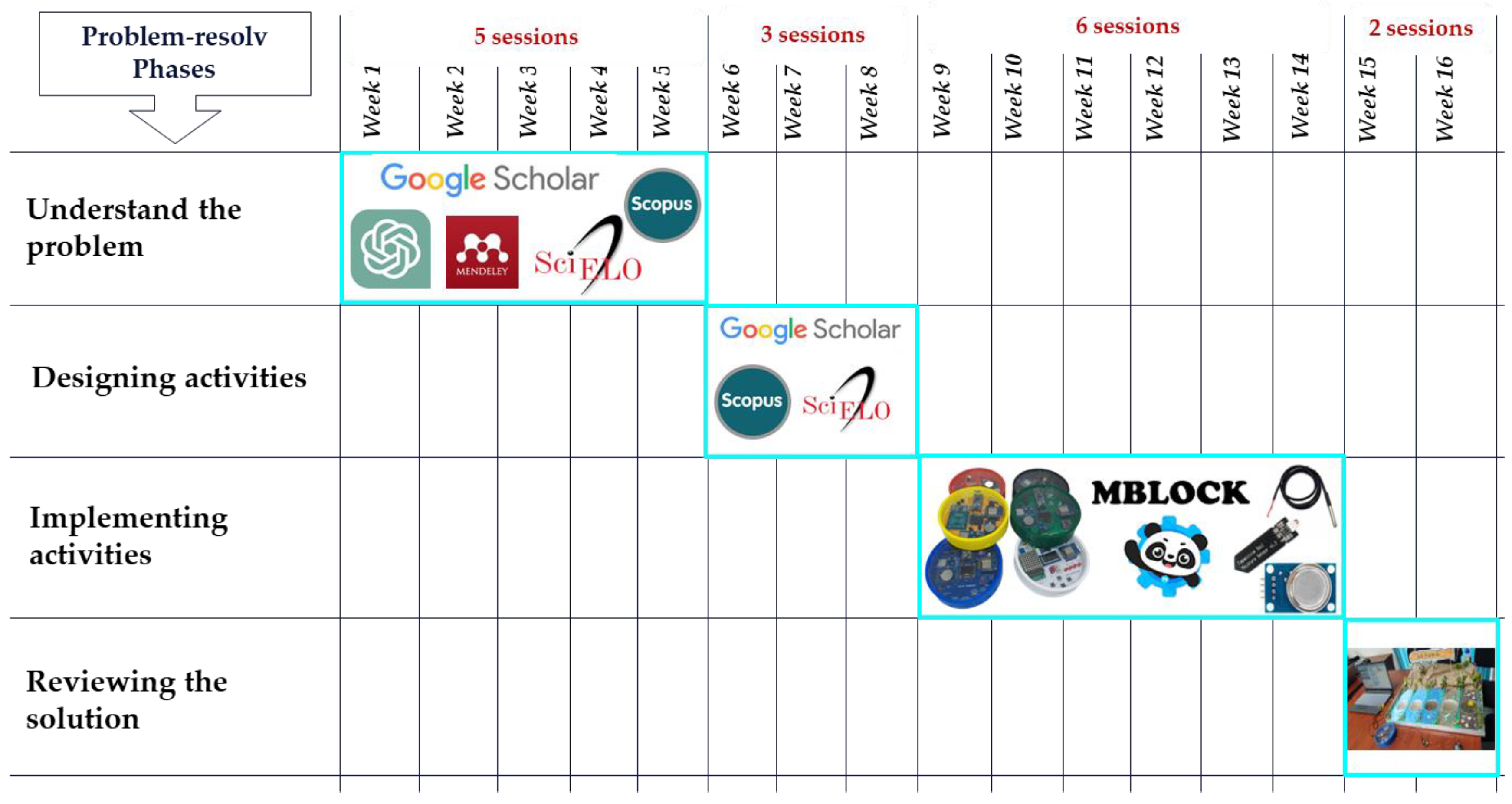

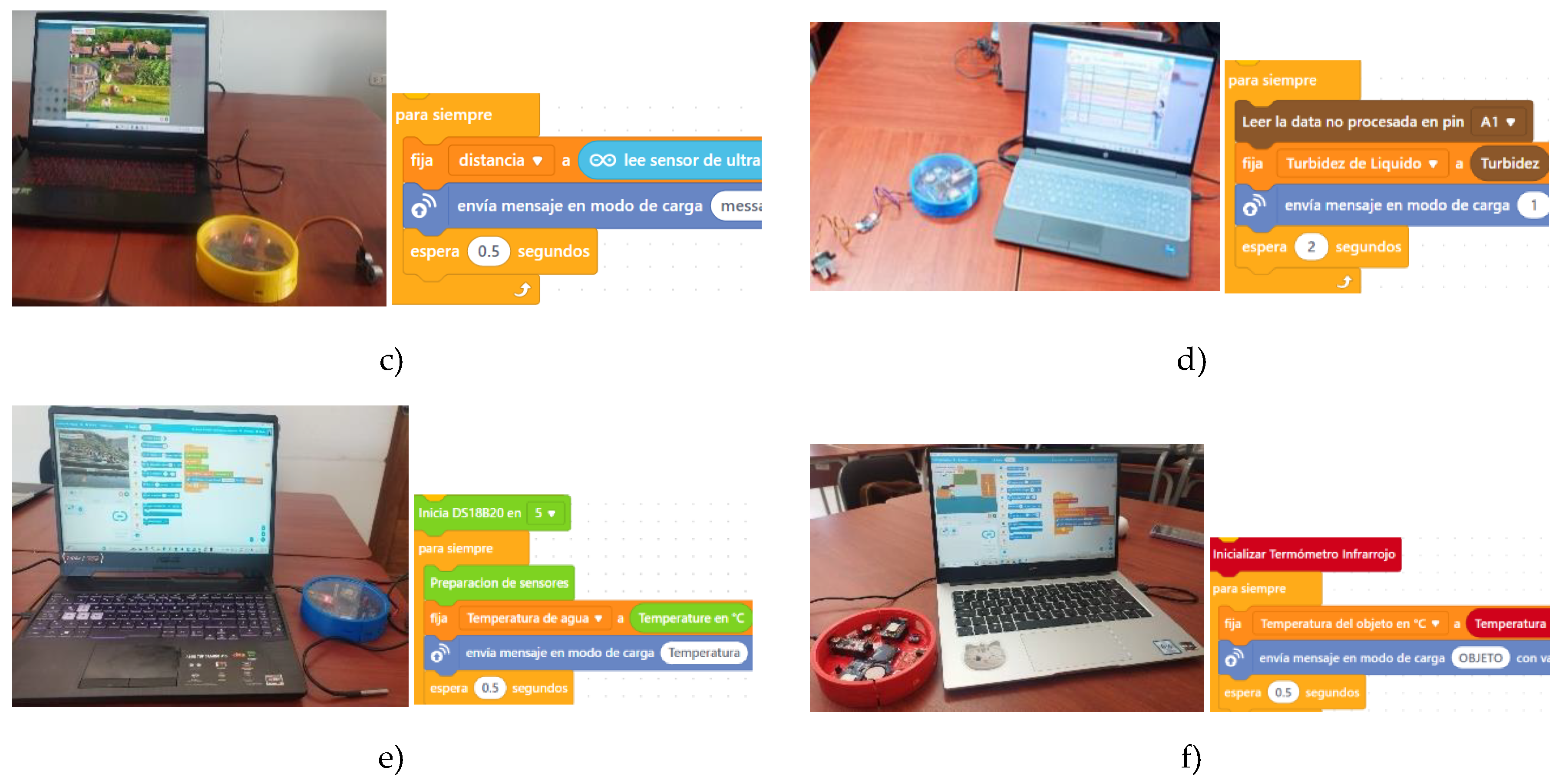

Implementing activities (2 sessions). In this stage, students addressed the identified problem through the implementation of the previously designed activities. As a first step, they familiarized themselves with the operation of the STEM educational kit’s electronic boards, sensors, and actuators by following a laboratory guide prepared for this purpose. Once the basic knowledge was acquired, they proceeded to assemble the circuits and connect them to their laptops. Next, they developed applications using the visual programming environment mBlock, with the objective of monitoring various health-related parameters such as air quality, water turbidity, body temperature, soil moisture, water temperature, and distance. In addition, the students built a model to simulate the proposed solution by integrating the STEM educational kit’s electronic boards and sensors with the application developed in mBlock. They also wrote a report that documented the information obtained during the experience.

Figure 5 shows part of the activity implementation process, highlighting the use of STEM kit electronic boards, their associated sensors, and the programming routines developed in mBlock.

Table 5 presents the methodological sequence followed in the development of applications using mBlock, within the framework of six formative research projects carried out by nursing students. This sequence integrated various activities: from selecting visual scenarios representative of the local context, designing digital characters, programming the logic of operation, to building interactive physical models. As an illustrative example, the application developed in project FR-2 is presented, titled “Monitoring air quality in households using wood-fired stoves to prevent respiratory problems in the district of Andaymarca, in the province of Tayacaja.” This process allowed students not only to develop technical skills related to programming, design, and data interpretation, but also to integrate cultural, linguistic, and social expressions from the Andean context—thus promoting a pedagogical experience that was contextualized, interdisciplinary, and culturally relevant.

Solution Review. In this phase, students verified the results obtained from the research activities carried out in the classroom. They evaluated the functionality of the models developed after integrating the electronic boards from the STEM educational kit and programming their behavior using the mBlock platform. Subsequently, they optimized the results based on the observations and suggestions provided by the instructor and completed the preparation of their research article.

Figure 6 presents a series of models built by the students, simulating different health-related problem contexts. The cases addressed include: vegetable cultivation in relation to anemia, the impact of wood-fired kitchen smoke on respiratory health, safety in guinea pig farms against predators and its effect on human health, water turbidity and its link to stomach infections, water temperature variation in fish farms and its impact on human health, and monitoring of children’s body temperature in educational settings. These problems were monitored through applications developed in mBlock, using sensors integrated into the electronic boards for data collection and analysis, aiming to validate the functionality of the solutions proposed by the students themselves.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Evaluation of Research Competence According to the Problem-Solving Phases

Table 6 presents the statistical summary of research competence within the context of formative research, according to the phases of problem-solving. The results show improvements across all evaluated phases after the intervention, with increases in both means and medians indicating a general positive effect. In most cases, the decrease in standard deviation suggests that responses were more consistent in the post-test.

4.2. Hypothesis Testing of Research Competence According to the Phases of the Problem-Solving Method

The statistical analysis begins with the normality test of the collected data. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic was used because the sample size exceeds 50.

Table 7 shows the p-values for the pre- and post-test related to the assessment of research competencies according to the phases of the problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal. The results indicate a p-value less than 0.001; this value is lower than the significance level (0.05), indicating that the corresponding data do not follow a normal distribution.

Since the scores obtained do not follow a normal distribution, the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test for related samples was used to test the hypothesis: “The implementation of a problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal and complemented with an electronic STEM educational kit contributes to the strengthening of research competencies in nursing students.”

Table 8 presents the results of the hypothesis test applied to each phase of the problem-solving method.

Since all p-values are < 0.05, the null hypothesis (H₀) is rejected in each of the phases, concluding that the educational intervention had a statistically significant effect on the development of research competencies. These findings support the effectiveness of the implemented methodological approach, highlighting its usefulness in promoting critical analysis, autonomous planning, technological application, and reflective evaluation processes among first-year nursing students. The results demonstrate the hypothesis that “The implementation of a problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal and complemented with an electronic STEM educational kit contributes to the strengthening of research competencies in nursing students.”

4.3. Analysis of Research Competence Development According to the Problem-Solving Phases

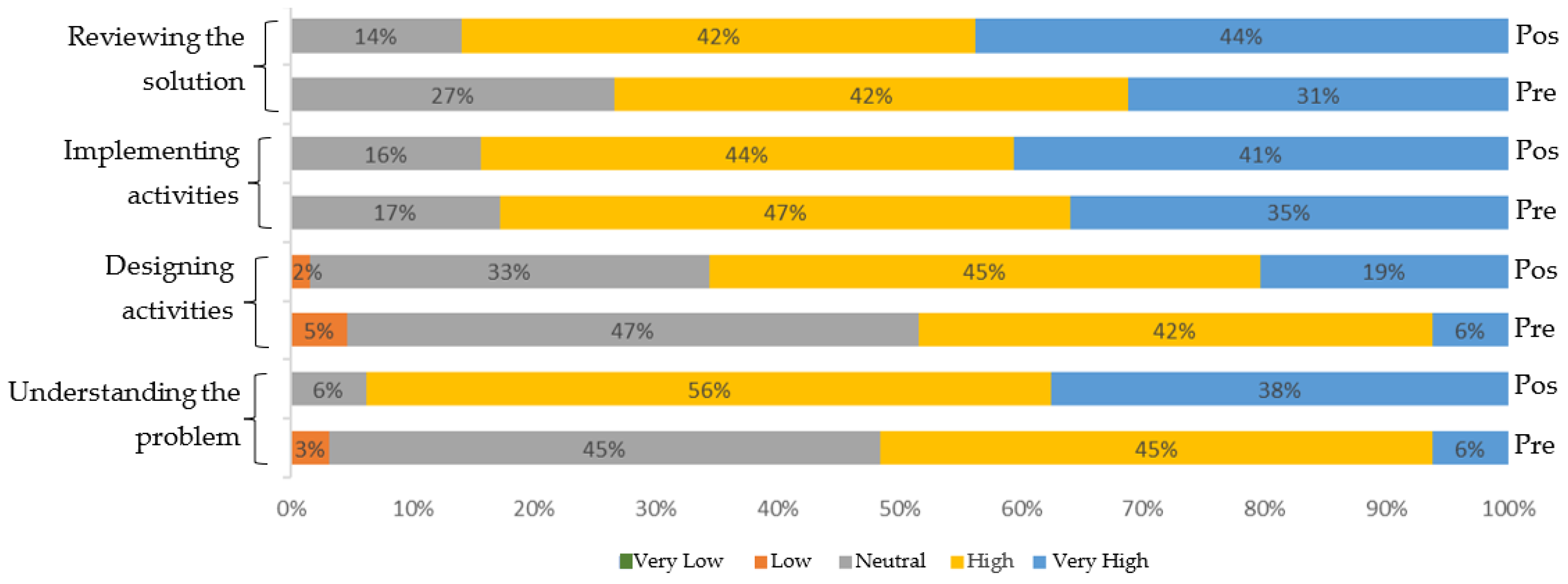

The results shown in

Figure 7 highlight the development of research competence in nursing students following the application of the four-phase problem-solving method, supported by a STEM educational kit. The analysis is structured according to the four phases: understanding the problem, planning activities, executing activities, and reviewing the solution.

In the understanding the problem phase, a significant improvement is observed. The “high” and “very high” levels increased from 45% and 6% (pre-test) to 56% and 38% (post-test), respectively. At the same time, the “neutral” level decreased from 45% to 6%, and the “low” level disappeared in the post-test.

During the planning of activities phase, a notable improvement is also evident. The “high” and “very high” levels increased from 42% and 6% (pre-test) to 45% and 19% (post-test), while the “neutral” level decreased from 47% to 33% and the “low” level dropped from 5% to 2%. These results suggest that students were able to design activities with greater autonomy, logic, and relevance. It is worth noting that low performance levels practically disappeared.

In the execution of activities phase, an increase in the “high” level is observed, rising from 35% (pre-test) to 41% (post-test). However, there is a slight decrease in the “neutral” level, from 47% to 44%, and the “very high” level is not present in either measurement. These results indicate a gradual consolidation of students’ ability to apply technological tools and to implement activities in a structured and sequential manner.

Finally, in the reviewing the solution phase, the percentage of students at the “very high” level increases from 31% to 44%, reflecting a strengthening of critical thinking and the ability to evaluate and improve their own solutions. The “high” level remains constant at 42%, while the “neutral” level drops from 27% to 14%.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study confirm that the application of the problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal, combined with the use of a STEM educational kit, had a positive effect on the development of research competencies in nursing students from a recently established public university. This methodological approach allowed the research process to be structured into four well-defined phases: understanding the problem, designing activities, executing activities, and reviewing the solution—thus providing a clear and guided didactic framework for students in the early stages of their academic training [

33,

34].

Descriptive results showed a sustained increase in the “high” and “very high” levels across all evaluated phases, with the most notable improvement in the execution and review phases. These results were statistically supported by the non-parametric Wilcoxon test (p < 0.05), demonstrating that the proposed method effectively contributed to strengthening research skills related to identifying problems, planning or designing activities, implementing solutions, and critically evaluating outcomes [

35,

36,

37].

A key aspect of the intervention’s success was the integration of the STEM educational kit, which provided a tangible and practical experience for nursing students. Through interaction with sensors, electronic boards, and the mBlock visual programming environment, students were able to materialize technological solutions to real-world health problems, developing functional applications and representative models. These activities bridged theoretical knowledge with the students’ social context and promoted meaningful learning through inquiry, design, and experimentation [

11].

The problem-solving method based on Pólya’s approach, by incorporating accessible technologies and a logical sequence of activities, proved to be appropriate for the cognitive level of first-year students. The tasks not only developed technical skills—such as programming, using sensors, and designing prototypes—but also transversal competencies like collaboration, scientific communication, and informed decision-making. This finding aligns with studies by Molina [

38], Fronza [

26], and Ortega and Asensio [

25], who highlight the effectiveness of combining problem-solving strategies with visual educational technologies to enhance research attitudes and strengthen skills in novice students [

12,

23].

Regarding the activity execution phase, there were noticeable improvements in performance levels, although some students showed slight delays, possibly due to the learning curve associated with new technologies. For this reason, future research might consider longer intervention periods or more intensive technical support strategies to enhance the impact of this phase [

39].

Overall, the obtained results support the conclusion that the problem-solving method based on Pólya’s approach and the STEM educational kit constitute an innovative and relevant pedagogical strategy for fostering formative research in the health field. This experience demonstrated the feasibility of integrating active methodologies with educational technology in nursing programs, enabling not only the development of research competencies but also the training of professionals capable of addressing real-world problems from a scientific, technological, and contextualized perspective [

40,

41].

These findings not only reveal a strengthening of students’ research competencies but also contribute to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 4 (Quality Education) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities) [

7]. By implementing active pedagogical strategies supported by technology, more equitable, inclusive, and context-sensitive education is promoted—especially relevant for higher education institutions in vulnerable regions [

15,

42]. Furthermore, the use of STEM educational kits and problem-solving-centered methodologies drives the formation of critically thinking professionals capable of addressing social and environmental challenges in their communities, aligning with a long-term vision of sustainable development [

10].

6. Conclusions

The implementation of the problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal—structured into four phases (understanding the problem, designing activities, executing activities, and reviewing the solution)—has proven to be an effective pedagogical strategy for strengthening research competencies in nursing students at a recently established public university in Peru.

A key component of this approach was the integration of the STEM educational kit, which enabled students to develop applied projects using sensors and visual programming with mBlock. These projects were materialized in functional models that simulated technological solutions to real-world problems related to public health, sanitation, and prevention.

Classroom experience showed that the use of the STEM kit not only facilitated active learning and conceptual understanding, but also promoted autonomy, critical thinking, and the transfer of knowledge to real-life contexts. This technological approach improved students’ perception of their own ability to investigate, analyze problems, and propose practical solutions.

In addition to progress in research competencies, transversal skills such as collaborative work, effective communication, and informed decision-making were also strengthened—key elements for the comprehensive training of health professionals.

Overall, this experience suggests that the problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal, together with technological tools such as the STEM educational kit, represents a relevant and scalable pedagogical alternative for promoting formative research in degree programs such as nursing, with high potential for replication in other higher education disciplines.

In summary, the methodological approach employed in this study not only positively impacts the development of research competencies, but also aligns with the principles of educational sustainability. By promoting meaningful, technological, and contextualized learning, it contributes to the construction of resilient educational systems capable of reducing structural gaps and fostering a citizenry committed to addressing environmental and social challenges. This type of educational intervention offers a replicable model for advancing toward a more equitable, ethical, and sustainable professional education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.P.-C., R.Y.M.-R. and P. J.G.-M.; methodology and formal analysis, R.P.-C., R.Y.M.-R. and P. J.G.-M.; investigation, R.P.-C. and R.Y.M.-R..; resources and data curation, R.P.-C. and R.Y.M.-R..; writing—original draft preparation, R.P.-C. and P. J.G.-M.; project administration and funding acquisition, R.P.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Council for Science, Technology and Technological Innovation (CONCYTEC – Peru).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- E. E. Espinoza, “La investigación formativa. Una reflexión teórica,” Revista Conrado, vol. 16, no. 74, pp. 45–53, 2020.

- O. Turpo-Gebera, P. M. Quispe, L. C. Paz, and M. Gonzales-Miñán, “Formative research at the university: Meanings conferred by faculty at an Education Department,” Educacao e Pesquisa. 2020; 46, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- L. Rivas, R. Loli, and M. Quiroz, “Percepción de estudiantes de enfermería sobre la investigación formativa en pregrado,” ECIMED, vol. 3, no. 36, pp. 1–15, 2020.

- A. Hernández, M. Illesca-Pretty, K. Hein-Campana, and J. Godoy-Pozo, “Percepción del estudiante de enfermería sobre investigación formativa Perception of nursing students about formative research,” AMC, vol. 6, no. 24, pp. 774–785, 2020. Available online: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5779-6167.

- M. Llanos de Tarazona, “Uso de tecnologías de información y comunicación y habilidades investigativas en estudiantes de enfermería,” Revista Peruana de Ciencias de la Salud, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 185–190, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Sterling, Sustainable Education – Re-visioning learning and change. 2001. Accessed: Jun. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.greenbooks.co.uk/sustainable-education.

- UNESCO, “Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap,” París, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Portillo, El aprendizaje servicio, la educación para el desarrollo sostenible y las competencias transversales, una vía hacia sociedades sostenibles. 2018. [Online]. Available: http://hdl.handle.net/10433/6323.

- UNESCO, Descifrar el código: La educación de las niñas y las mujeres en ciencias, tecnología, ingeniería y matemáticas (STEM). 2019. [Online]. Available: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366649?posInSet=1&queryId=d5f381da-86f6-442b-8f3b-a86a83220043.

- United Nations, “Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.” Accessed: Jun. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

- R. Paucar-Curasma, K. O. R. Paucar-Curasma, K. O. Villalba-Condori, J. Mamani-Calcina, D. Rondon, M. G. Berrios-Espezúa, and C. Acra-Despradel, “Use of Technological Resources for the Development of Computational Thinking Following the Steps of Solving Problems in Engineering Students Recently Entering College,” Educ Sci (Basel). 2023; 13, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Paucar-Curasma et al., “VISUAL PROGRAMMING AND PROBLEM-SOLVING TO FOSTER A POSITIVE ATTITUDE TOWARDS FORMATIVE RESEARCH,” Visual Review, vol. 1, no. 17, pp. 111–126, 2025.

- R. Paucar-Curasma, K. O. R. Paucar-Curasma, K. O. Villalba-Condori, S. H. Gonzales-Agama, F. T. Huayta-Meza, D. Rondon, and N. N. Sapallanay-Gomez, “Technological Resources and Problem-Solving Methods to Foster a Positive Attitude Toward Formative Research in Engineering Students,” Educ Sci (Basel), vol. 14, no. 12, Dec. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PROCIENCIA-CONCYTEC, “Investigadores de Huancavelica desarrollan dispositivo educativo para facilitar aprendizaje sencillo para universitarios - Noticias - Programa Nacional de Investigación Científica y Estudios Avanzados - Plataforma del Estado Peruano.” Accessed: Jun. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/prociencia/noticias/919234.

- D. S. Boakye, A. A. Kwashie, S. Adjorlolo, and K. A. Korsah, “Nursing Education for Sustainable Development: A Concept Analysis,” Nurs Open, vol. 11, no. 10, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- U. Lapa-Asto, G. Tirado-Mendoza, and A. Roman-Gonzalez, “Impact of Formative Research on Engineering students,” in 2019 IEEE World Conference on Engineering Education (EDUNINE), 2019.

- F. Alvarado, G. Villar-Mayuntupa, and A. Roman-Gonzalez, “The formative research in the development of reading and writing skills and their impact on the development of indexed publications by engineering students,” in 2020 IEEE World Conference on Engineering Education (EDUNINE), 2020.

- J. Zúñiga-Cueva, E. Vidal-Duarte, and A. Padrón Alvarez, “Methodological Strategy for the Development of Research Skills in Engineering Students: A Proposal and its Results,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 2021, pp. 2525–2536.

- D. Llulluy-Nuñez, F. V. Luis Neglia, J. Vilchez-Sandoval, C. Sotomayor-Beltrán, L. Andrade-Arenas, and B. Meneses-Claudio, “The impact of the work of junior researchers and research professors on the improvement of the research competences of Engineering students at a University in North Lima,” in Proceedings of the LACCEI international Multi-conference for Engineering, Education and Technology, Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Sánchez Carlessi, “La Investigación Formativa En La Actividad Curricular,” Revista de la Facultad de Medicina Humana. 2017; 17, 0–3. [CrossRef]

- R. Paucar-Curasma, I. Frango, D. Rondon, Z. López, and L. Porras-Ccancce, “Analysis of the Teaching of Programming and Evaluation of Computational Thinking in Recently Admitted Students at a Public University in the Andean Region of Peru Ronald,” in Congreso Internacional de Tecnología e Innovación Educativa, Arequipa, 2022, p. 10.

- G. Polya, How to Solve It, 2da ed. New York: Princeton University Press, Doubleday Anchor Books, 1945.

- R. Paucar-Curasma et al., “Development of Computational Thinking through STEM Activities for the Promotion of Gender Equality,” Sustainability (Switzerland). 2023; 15, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- R. Paucar-Curasma, K. O. Villalba-Condori, S. C. F. Viterbo, J. J. Nolan, U. T. R. Florentino, and D. Rondon, “Fomento del pensamiento computacional a través de la resolución de problemas en estudiantes de ingeniería de reciente ingreso en una universidad pública de la región andina del Perú,” RISTI - Revista Ibérica de Sistemas e Tecnologias de Informação, no. 48. 2022; 23–40. [CrossRef]

- B. Ortega and M. Asensio, “Evaluar el Pensamiento Computacional mediante Resolución de Problemas: Validación de un Instrumento de Evaluación,” Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 153–171. 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Fronza, L. Corral, and C. Pahl, “Combining block-based programming and hardware prototyping to foster computational thinking,” SIGITE 2019 - Proceedings of the 20th Annual Conference on Information Technology Education. 2019; 55–60. [CrossRef]

- A. Fidai, M. M. Capraro, and R. M. Capraro, “‘Scratch’-ing computational thinking with Arduino: A meta-analysis,” Think Skills Creat, vol. 38, no. July, p. 100726, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Melo, M. Fidelis, S. Alves, U. Freitas, and R. Dantas, “A comprheensive review of Visual Programming Tools for Arduino,” in 2020 Latin American Robotics Symposium, 2020 Brazilian Symposium on Robotics and 2020 Workshop on Robotics in Education, LARS-SBR-WRE 2020, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Paucar-Curasma, A. Gamarra-Moreno, D. Rondon, R. Unsihuay, and F. Huayta-Meza, “Design of a Hardware Prototype with Block Programming to Develop Computational Thinking in Recently Admitted Engineering Students,” in Congreso Internacional de Tecnología e Innovación Educativa, Arequipa, 2022, p. 7.

- G. Falloon, “What’s the difference? Learning collaboratively using iPads in conventional classrooms,” Comput Educ. 2015; 84, 62–77. [CrossRef]

- A. Bustamante-Mora, M. Diéguez-Rebolledo, J. Díaz-Arancibia, E. Sánchez-Vázquez, and J. Medina-Gómez, “Inclusive Pedagogical Models in STEM: The Importance of Emotional Intelligence, Resilience, and Motivation with a Gender Perspective,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 17, no. 10, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Paucar-Curasma, “Influencia del pensamiento computacional en los procesos de resolución de problemas en los estudiantes de ingeniería de reciente ingreso a la universidad,” Chimbote, 2023. Accessed: Sep. 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://repositorio.uns.edu.pe/handle/20.500.14278/4199.

- F. H. Fernández and J. E. Duarte, “El aprendizaje basado en problemas como estrategia para el desarrollo de competencias específicas en estudiantes de ingeniería,” Formacion Universitaria. 2013; 6, 29–38. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Pinto and O. F. Cortés, “Qué piensan los estudiantes universitarios frente a la formación investigativa,” 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Neo, J. K. A. H. Neo, J. K. Wong, V. C. Chai, Y. L. Chua, and Y. H. Hoh, “Computational Thinking in Solving Engineering Problems – A Conceptual Model Definition of Computational Thinking. 2021; 11, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. Pluhár and H. Torma, “Introduction to Computational Thinking for University Students,” 2019, Springer, Faculty of Informatics, Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, Hungary. [CrossRef]

- P. Karmawan and W. Djamilah, “STEM: Its Potential in Developing Students’ Computational Thinking,” KnE Social Sciences, pp. 1074–1083, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Á. Molina, N. Á. Molina, N. Adamuz, and R. Bracho, “La resolución de problemas basada en el método de Polya usando el pensamiento computacional y Scratch con estudiantes de Educación Secundaria,” Handbook of Educational Psychology, pp. 287–303. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Ortega-Ruipérez, “Pedagogía del Pensamiento Computacional desde la Psicología: un Pensamiento para Resolver Problemas.,” Cuestiones Pedagógicas, vol. 2, no. 29, pp. 130–144. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Suárez, J. R. Suárez, J. Cabrera, and I. Zapata, “Specialized nursing professional. Does this specialist make the best use of technology in care?,” Revista Habanera de Ciencias Médicas, vol. 3, no. 21, pp. 1–5, 2022, [Online]. Available: http://www.revhabanera.sld.cu/index.php/rhab/article/view/4056.

- R. Rossi-Rivero and C. Padilla-Choperena, “Tecnología, globalización e investigación en enfermería: aproximaciones para un nuevo modelo de formación profesional,” Revista Cultura del Cuidado Enfermería, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 89–98, 2019.

- U. Müller, D. U. Müller, D. Hancock, C. Wang, T. Stricker, and Q. Liu, “Implementing Education for Sustainable Development in Organizations of Adult and Continuing Education: Perspectives of Leaders in China, Germany, and the USA,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 17, no. 10, May 2025. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Problem-Solving Method Based on Pólya’s Proposal.

Figure 1.

Problem-Solving Method Based on Pólya’s Proposal.

Figure 2.

STEM Educational Kit with Visual Programming Environment: a) Six educational electronic boards and b) mBlock visual programming interface.

Figure 2.

STEM Educational Kit with Visual Programming Environment: a) Six educational electronic boards and b) mBlock visual programming interface.

Figure 3.

Distribution of sessions and resources used during the educational intervention through the phases of the problem-solving method.

Figure 3.

Distribution of sessions and resources used during the educational intervention through the phases of the problem-solving method.

Figure 4.

Cause-and-effect representation of the problematic situation in the proposed research topics: a) FR-1, b) FR-2, c) FR-3, d) FR-4, e) FR-5, and f) FR-6.

Figure 4.

Cause-and-effect representation of the problematic situation in the proposed research topics: a) FR-1, b) FR-2, c) FR-3, d) FR-4, e) FR-5, and f) FR-6.

Figure 5.

Implementation of research activities in the classroom: a) FR-1, b) FR-2, c) FR-3, d) FR-4, e) FR-5, and f) FR-6.

Figure 5.

Implementation of research activities in the classroom: a) FR-1, b) FR-2, c) FR-3, d) FR-4, e) FR-5, and f) FR-6.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of research results: ) FR-1, b) FR-2, c) FR-3, d) FR-4, e) FR-5, and f) FR-6.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of research results: ) FR-1, b) FR-2, c) FR-3, d) FR-4, e) FR-5, and f) FR-6.

Figure 7.

Development of research competences according to the phases of the problem-solving method.

Figure 7.

Development of research competences according to the phases of the problem-solving method.

Table 1.

Items of the instrument.

Table 1.

Items of the instrument.

| Understanding the Problem |

| 1 |

Do you read the project or assignment statement several times? |

| 2 |

Do you understand the project or assignment statement? |

| 3 |

Can you explain the problem of the project or assignment in your own words? |

| 4 |

Can you easily identify the cause and effect of the problem? |

| 5 |

Is it easy for you to represent the problem using a visual organizer? |

| 6 |

Can you easily identify the most important data of the problem? |

| 7 |

Can you identify a problem similar to the one in your project or assignment? |

| Designing activities |

| 1 |

Can you easily find a similar project or assignment? |

| 2 |

Do you recognize the project activities slightly differently in another project? |

| 3 |

Do you find or identify an activity from another project that helps you plan your own? |

| 4 |

Do you break down the solution into several parts? |

| 5 |

Can you identify the technological resources needed to develop the project activities? |

| Implementing activities |

| 1 |

Do you carry out everything planned in the previous step? |

| 2 |

Do you use technological resources during the execution of the project activities? |

| 3 |

Do you carry out the tasks step by step? |

| 4 |

Do you demonstrate that the activities are executed in an orderly and sequential manner? |

| 5 |

Do you perform the activities in an orderly and sequential way? |

| Reviewing the Solution |

| 1 |

Do you review or test the functionality of the solution results? |

| 2 |

Do you verify the functionality of each component or part of the solution results? |

| 3 |

Do you analyze if there are other alternatives to solve the project problem? |

| 4 |

Is it easy for you to apply the solution results to solve another project problem? |

| 5 |

Does the solution cover all parts of the problem? |

| 6 |

Do you identify any component or part of the solution to improve or optimize? |

| 7 |

Do you identify any component or part of the solution that can be reused in another project? |

Table 2.

Items by Problem-Solving Phase and Cronbach’s Alpha.

Table 2.

Items by Problem-Solving Phase and Cronbach’s Alpha.

| Problem-Solving Phase |

Items |

Pre-test |

Post-test |

| Understanding the problem |

7 |

0.950 |

0.950 |

| Designing activities |

5 |

0.950 |

0.949 |

| Implementing activities |

5 |

0.949 |

0.949 |

| Reviewing the solution |

7 |

0.949 |

0.949 |

Table 3.

Formative Research Projects and STEM Educational Kit.

Table 3.

Formative Research Projects and STEM Educational Kit.

| ID |

Formative Research Project |

Description |

Sensor |

STEM Educational Kit |

| FR-1 |

Monitoring soil moisture in vegetable crops to prevent anemia in school-age children in the district of Acraquia, Tayacaja province. |

The project involves monitoring soil moisture in vegetable crops to prevent anemia in school-age children in Acraquia, Tayacaja province. For this, the agriculture board, a capacitive soil moisture sensor, and the mBlock programming environment were used. |

Capacitive Soil Moisture Sensor Capacitive Soil Moisture Sensor |

Agriculture card Agriculture card |

| FR-2 |

Monitoring air quality in homes with wood-burning stoves to prevent respiratory issues in the district of Andaymarca, Tayacaja province. |

The project focuses on monitoring air quality in homes using wood-burning stoves to prevent respiratory problems in Andaymarca, Tayacaja. The environment board, MQ135 air quality sensor, and mBlock were used. |

MQ135 Air Quality Sensor MQ135 Air Quality Sensor |

Environment card Environment card |

| FR-3 |

Monitoring guinea pig pens to prevent salmonella transmission in Santa Rosa community, Tayacaja province, which could affect human meat consumption. |

The project involves monitoring guinea pig pens to prevent attacks from predators and avoid the consumption of contaminated meat in the Santa Rosa community, Tayacaja. The livestock board, ultrasonic distance sensor, and mBlock were used. |

HC-SR04 Distance Sensor |

Livestock card Livestock card |

| FR-4 |

Monitoring water quality to prevent stomach infections among residents of the district of Ustuna, Tayacaja province. |

The project consists of monitoring water quality to prevent stomach infections in the population of Ustuna, Tayacaja. The aquaculture board, turbidity sensor, and mBlock environment were used. |

Water Turbidity Sensor Water Turbidity Sensor |

Aquaculture card Aquaculture card |

| FR-5 |

Monitoring water temperature in the “La Cabaña” fish farm to avoid trout mortality and potential consumption of contaminated meat in Tayacaja province. |

The project consists of monitoring water temperature in the “La Cabaña” fish farm to prevent trout deaths and avoid the consumption of contaminated meat in Tayacaja. The aquaculture board, DS18B20 temperature sensor, and mBlock were used. |

DS18B20 Water Temperature Sensor DS18B20 Water Temperature Sensor |

Aquaculture card Aquaculture card |

| FR-6 |

Monitoring children’s body temperature to prevent fever outbreaks at IE Mariscal Cáceres school in Daniel Hernández Morillo district, Tayacaja. |

This project focuses on monitoring children’s body temperature to prevent fever outbreaks at IE Mariscal Cáceres school in the district of Daniel Hernández Morillo, Tayacaja. The health board, MLX90614 sensor, and mBlock environment were used. |

MLX90614 Body Temperature Sensor MLX90614 Body Temperature Sensor |

Health card Health card |

Table 4.

List of activities proposed to solve the identified problems: a) FR-1, b) FR-2, c) FR-3, d) FR-4, e) FR-5, and f) FR-6.

Table 4.

List of activities proposed to solve the identified problems: a) FR-1, b) FR-2, c) FR-3, d) FR-4, e) FR-5, and f) FR-6.

− Identify and understand the issue related to the supervision and production of vegetables in the district of Acraquia.

− Design the circuit using the agriculture board and soil moisture sensor.

− Program the sensors to acquire soil moisture parameters.

− Develop an application to monitor soil moisture.

− Build a model simulating a greenhouse for measuring soil moisture parameters.

|

− Identify and understand the problem of air pollution caused by the use of wood-burning stoves in the district of Andaymarca.

− Design the circuit using the environment board and the MQ135 air quality sensor.

− Identify parameters related to Air Quality Index (AQI).

− Develop an application to monitor air quality using mBlock, allowing visualization of the AQI.

− Build a prototype simulating a household with wood-burning stoves for measuring air quality parameters.

|

| a) |

b) |

− Test the functionality of the livestock board and the HC-SR04 ultrasonic sensor. − Develop an application to alert about predator attacks on guinea pigs and to display health information using mBlock. − Build a model simulating guinea pig farming. |

− Recognize and test the functionality of the aquaculture board and turbidity sensor. − Design a turbidity monitoring system using the aquaculture board. − Develop an application for water turbidity monitoring using mBlock software. − Build a model simulating water quality level. |

| c) |

d) |

− Implement the circuit using the aquaculture board and DS18B20 water temperature sensor. − Develop an application in mBlock to measure water temperature variation. − Build a model representing the “La Cabaña” fish farm in Acostambo. − Verify the correct operation of the application. |

− Implement the circuit using the health board and MLX90614 body temperature sensor. − Develop an application using mBlock to display body temperature values in a user-friendly way. − Build a prototype simulating a system for monitoring body temperature parameters. |

| e) |

f) |

Table 5.

Development of Applications in mBlock (FR-2).

Table 5.

Development of Applications in mBlock (FR-2).

Table 6.

Summary Statistical Analysis.

Table 6.

Summary Statistical Analysis.

| Phases of the Problem-Solving Method. |

Mean |

Median |

Standard Deviation |

| Pre-test |

Pos-test |

Pre-test |

Pre-test |

Pos-test |

Pre-test |

| Understanding the problem |

4.31 |

4. 45 |

4.00 |

4.00 |

0.665 |

0.588 |

| Designing activities |

3.50 |

3.84 |

3.00 |

4.00 |

0.690 |

0.761 |

| Implementing activities |

4.19 |

4.25 |

4.00 |

4.00 |

0.710 |

0.713 |

| Reviewing the solution |

4.05 |

4.30 |

4.00 |

4.00 |

0.765 |

0.706 |

Table 7.

Kolmogorov–Smirnov Normality Test.

Table 7.

Kolmogorov–Smirnov Normality Test.

| Kolmogórov-Smirnov |

| N |

|

64 |

|

| Statistic |

|

0.361 |

|

| Valor p |

|

< 0.001 |

|

Table 8.

Hypothesis testing with Wilcoxon test.

Table 8.

Hypothesis testing with Wilcoxon test.

| Hypothesis |

| H0 = “The implementation of a problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal and complemented with an electronic STEM educational kit does not contribute to the strengthening of research competencies in nursing students” |

| H1 = “The implementation of a problem-solving method based on Pólya’s proposal and complemented with an electronic STEM educational kit contributes to the strengthening of research competencies in nursing students” |

Significance Level: 5%

Decision Rule: If p ≥ 5%, do not reject H0. If p < 5%, reject H0. |

| Phases of the Problem-Solving Method |

Wilcoxon p-value |

Decision |

| Understanding the problem |

0.001 |

H₀ is rejected |

| Designing activities |

0.002 |

H₀ is rejected |

| Implementing activities |

0.002 |

H₀ is rejected |

| Reviewing the solution |

0.006 |

H₀ is rejected |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Capacitive Soil Moisture Sensor

Capacitive Soil Moisture Sensor Agriculture card

Agriculture card MQ135 Air Quality Sensor

MQ135 Air Quality Sensor Environment card

Environment card

Livestock card

Livestock card Water Turbidity Sensor

Water Turbidity Sensor Aquaculture card

Aquaculture card DS18B20 Water Temperature Sensor

DS18B20 Water Temperature Sensor Aquaculture card

Aquaculture card MLX90614 Body Temperature Sensor

MLX90614 Body Temperature Sensor Health card

Health card