1. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution, characterized by rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI), big data, and the Internet of Things (IoT), necessitates educational approaches that foster competencies that are essential for sustainable societal development [

1,

2,

3]. As these technologies become integral to daily life, students require a blend of technical skills and advanced cognitive and social capabilities to effectively navigate and contribute to a digitally interconnected world [

4,

5]. Key among these competencies are collaborative problem-solving (CPS), computational thinking (CT), and robust communication skills. These skills collectively enable learners to tackle complex challenges and engage proactively in community-oriented sustainability efforts. The rise of large language models and multimodal generative AI further highlights the transition from merely managing vast amounts of data to emphasizing data quality and practical utility, enabling personalized and contextualized learning experiences [

6,

7]. This technological shift significantly influences classroom strategies and curricular designs, promoting educational models that immerse students in real-world problem-solving activities where they can collaboratively analyze authentic data and communicate findings effectively. In alignment with these evolving educational needs, South Korea’s 2022 revised elementary informatics curriculum emphasizes collaborative communication (CC) and interdisciplinary, project-based learning approaches, positioning CPS as crucial for bridging classroom knowledge with tangible community engagement [

8].

Existing educational models, however, frequently lack mechanisms for sustained community involvement and structured communication, limiting their potential to cultivate the in-depth, transferable skills required for sustainability-oriented problem-solving [

9,

10]. To address these gaps, this study proposes the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving model(or Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model), integrating community-based collaboration, computational thinking, and structured communication within elementary informatics education. Leveraging the Living Lab approach—an open innovation method involving collaboration among educational institutions, communities, and societal stakeholders—the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model aims to enhance essential skills through meaningful and relevant community engagement. This study evaluates the model’s efficacy in fostering CPS, CT, and CC, providing a structured framework that merges theoretical knowledge with practical sustainability applications [

11].

Specifically, this research study two key questions:

RQ1: How can a Living Lab-based educational model be systematically developed and implemented to effectively integrate collaborative problem-solving, computational thinking, and collaborative communication within elementary informatics education for sustainable community engagement?

RQ2: What methodologies accurately evaluate the effectiveness of the Living Lab-based educational model in enhancing elementary students’ collaborative problem-solving, computational thinking, and collaborative communication competencies?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Integrating CPS, CC, and CT

The rapid evolution of digital technologies and the increased complexity of societal challenges highlight the necessity for educational frameworks that cultivate competencies such as CPS, CC, and CT [

12,

13]. These competencies are crucial for preparing learners to address multifaceted sustainability challenges through data-driven and collaborative approaches. CPS involves collective efforts in identifying, analyzing, and resolving shared tasks, significantly enhancing group adaptability and coordination [

14]. Effective communication, which is integral to CPS, ensures clarity, reduces misunderstandings, and facilitates consensus-building, thereby improving collaborative outcomes [

15]. Despite its importance, structured communication is frequently undervalued in educational contexts, resulting in ineffective problem-solving processes [

16].

CT offers a methodological approach to problem-solving, emphasizing problem decomposition, algorithmic reasoning, and iterative processes, thus enabling students to systematically manage complex problems [

17,

18]. For instance, iterative processes can be carried out through repeated algorithm refinement during student-led data analysis projects, allowing learners to test and improve their solutions incrementally. Incorporating CT within collaborative frameworks not only generates robust solutions but also deepens learners’ understanding and the practical application of informatics concepts [

19,

20]. To bridge theoretical learning and practical application, the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving model integrates CPS, CT, and CC within authentic community contexts—such as school-based initiatives to reduce local energy consumption or analyze transportation accessibility—promoting meaningful engagement and tangible contributions to sustainability.

2.2. Limitations of Existing Educational Approaches

Various instructional methods, including inquiry-based learning, cooperative learning, and project-based learning, have been developed and applied to encourage collaborative problem-solving in classrooms [

21,

22]. These models typically revolve around stimulating student curiosity, prompting them to explore topics, and guiding them to propose or prototype potential solutions. While such approaches can indeed spark engagement and a fundamental grasp of core concepts, they frequently fall short of offering iterative, hands-on experiences that stretch beyond the classroom context. Additionally, students in these environments may not always receive the structure or scaffolding needed to seamlessly weave computational thinking into their collaborative endeavors, which can hinder their ability to tackle large-scale, data-intensive problems effectively [

23,

24]. Similarly, informatics education has been identified as a promising domain for cultivating higher-order thinking skills, including logical reasoning and problem-solving using algorithmic methods. However, practical implementations of informatics education often concentrate on teaching specific coding languages or software tools rather than enabling students to engage with complex, real-world issues [

21,

25].

AI-driven educational platforms typically prioritize individualized learning but often overlook the importance of collaborative and communicative aspects, thus inadequately preparing learners for real-world group dynamics [

26]. Moreover, classroom-based collaborative tasks usually restrict interactions to small-scale, hypothetical scenarios, failing to expose learners to the complexity and diversity of real-world challenges. Therefore, educational frameworks must explicitly integrate community-based collaborations and structured communication strategies to enhance learners’ empathy, negotiation skills, and consensus-building capabilities, essential for addressing authentic sustainability issues.

2.3. Theoretical Foundations of the Living Lab-based Collaborative Problem-Solving Educational Model

The Living Lab approach has increasingly been recognized as a powerful educational model, fostering authentic, co-creational learning environments that effectively integrate theoretical knowledge and practical experiences. Research by Chapagain and Mikkelsen (2023) highlights how LL methodologies support collaborative learning by involving students in real-world community projects, promoting active participation and meaningful engagement [

11]. Lakatos et al. (2024) further underline LL’s role in addressing complex sustainability challenges through open innovation networks, emphasizing stakeholder collaboration and iterative experimentation [

27]. In alignment with these perspectives, Rogers et al. (2023) demonstrate the effectiveness of LL settings in enhancing students’ experiential learning, emphasizing that authentic tasks significantly enhance learners’ intrinsic motivation and practical problem-solving abilities [

28]. Complementing this, Leminen et al. (2012) position Living Labs as open-innovation environments, where students not only acquire theoretical knowledge but actively participate in innovation processes through structured collaboration with various stakeholders [

29]. Son and Kim (2024) provide critical insights into how informatics-based competencies intersect with interdisciplinary educational goals within the 2022 revised elementary curriculum [

30]. Their competency analysis underscores the necessity of systematically integrating collaborative problem-solving, computational thinking, and communication within educational frameworks to foster holistic learner development. Specifically, their study highlights computational reasoning and collaborative engagement as foundational competencies, proposing the structured integration of these skills can significantly enhance interdisciplinary problem-solving capabilities in elementary education contexts.

a. Building upon these theoretical foundations, the Living Lab-based educational model explicitly integrates three instructional pillars to address existing pedagogical gaps identified in related studies:

b. Authentic problem-solving: Engages students in real-world community issues, fostering intrinsic motivation and ethical considerations in technology application.

c. Computational thinking Integration: Encourages systematic problem-solving through iterative prototyping, algorithmic reasoning, and structured data analysis, preparing students to handle complexity effectively.

d. Structured communication Development: Provides explicit training in effective dialogue, negotiation, and constructive feedback, recognizing communication as a skill that requires deliberate instructional strategies rather than implicit acquisition.

The Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model operationalizes these pillars into an instructional framework, guiding learners from initial problem observation through iterative community collaboration toward meaningful societal impact. Consequently, the development and application of sustainable Living Lab-based educational models, such as the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model framework, are critical for equipping learners with essential competencies to effectively address complex sustainability challenges in dynamic societal contexts.

3. Materials and Methods

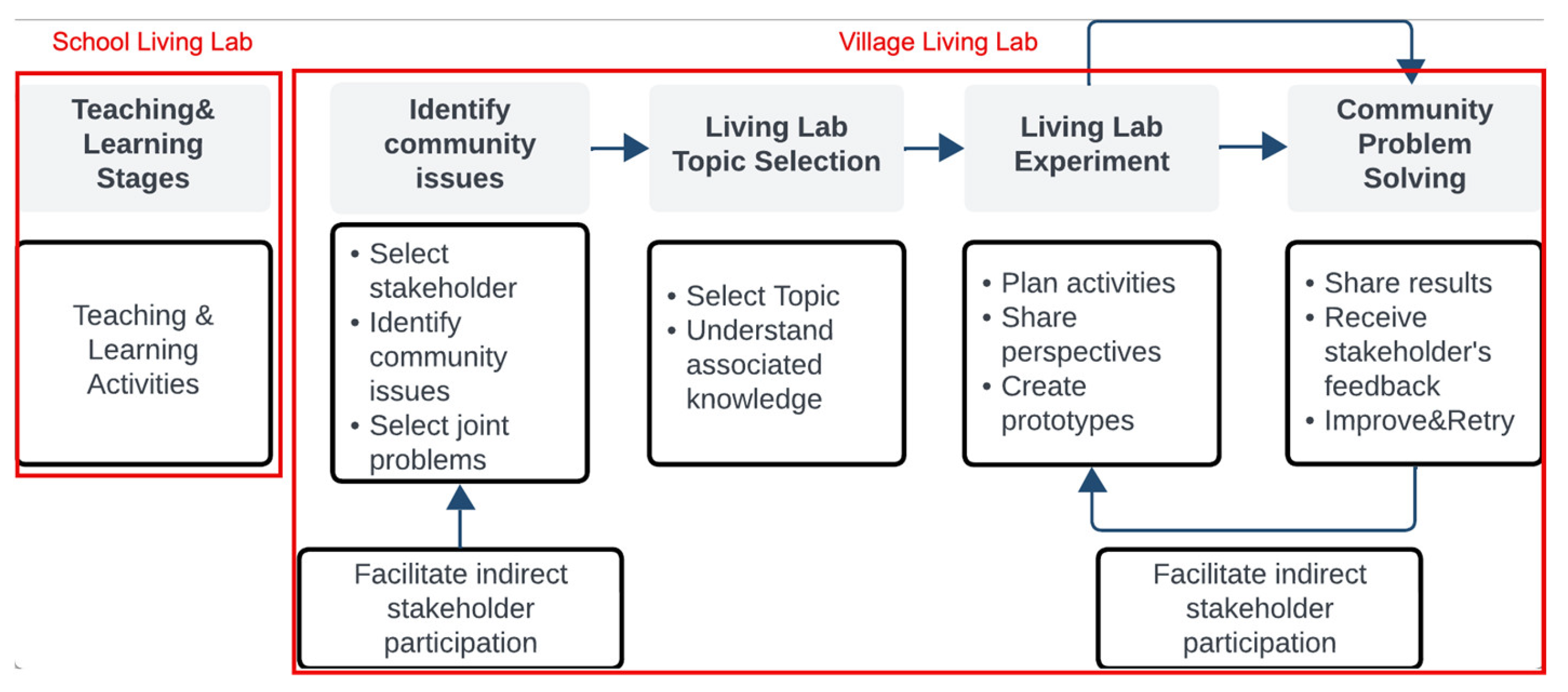

Prior to detailing the competency classification process, it is essential to outline the overall framework guiding the implementation of the Living Lab model. The existing Living Lab curriculum has been systematically divided into two distinct yet complementary environments: the School Living Lab and the Village Living Lab. The School Living Lab emphasizes structured classroom-based learning activities aimed at developing foundational competencies such as CPS, CT, and CC. In contrast, the Village Living Lab extends these competencies into practical, community-based experiences, providing students with opportunities to apply their skills in authentic, real-world contexts.

Figure 1 visually represents this division of the Living Lab curriculum into school-based and village-based educational contexts, clearly illustrating how the two components interconnect and complement each other to enhance experiential and competency-based learning [

30].

3.1. Competency Classification through Natural Language Processing

To systematically analyze and classify informatics-based competencies that are essential for interdisciplinary learning and real-world sustainability challenges, leveraging advanced computational techniques such as natural language processing (NLP) is crucial. NLP methods offer the capability to efficiently process extensive textual data, uncovering semantic relations and enhancing precision. In preparation for implementing the School Living Lab, this study specifically analyzed the competency definitions provided in the curricula of five elementary school subjects—language, mathematics, social studies, and science. Although these subjects emphasize similar core competencies, such as CPS, CC, and CT, their definitions vary significantly across the curricula. This targeted, definition-based analysis ensures a comprehensive understanding of how these competencies intersect and differ within fundamental educational contexts, effectively supporting the structured design and development of the School Living Lab framework as part of the broader integrated educational model.[

31,

32,

33]. The detailed NLP methodology employed in this study comprises several sequential stages, illustrated in

Table 1.

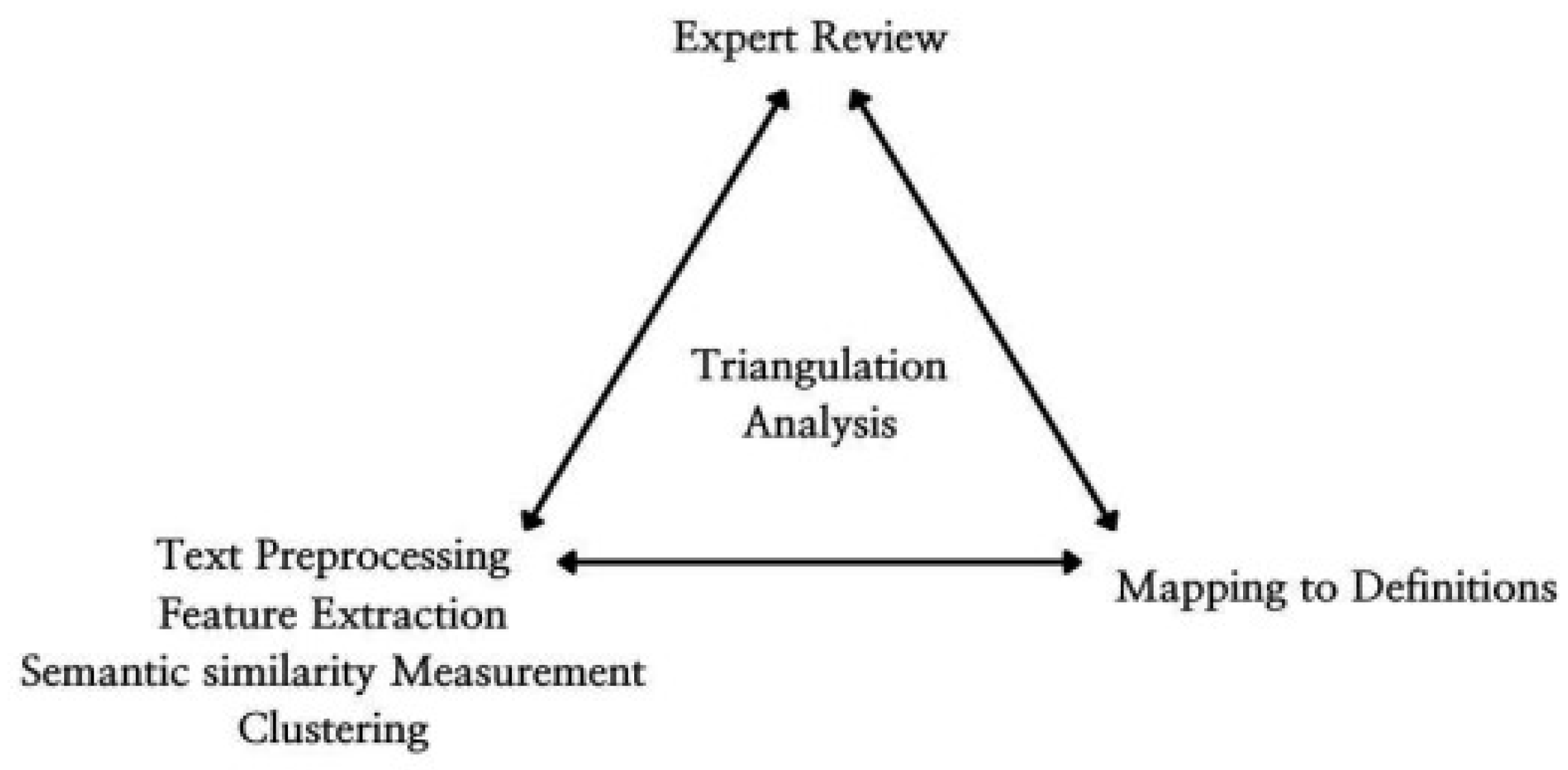

Three computer education experts independently reviewed the mapped competencies using a triangulation approach to ensure accuracy and validity. Due to cosine similarity scores often falling below the meaningful threshold of 0.4, methodological and researcher triangulation approaches were utilized. Methodological triangulation involved quantitative text analysis methods, including tokenization, lemmatization, stopword removal, vectorization, cosine similarity measurement, and hierarchical clustering. Researcher triangulation consisted of independent expert analyses and subsequent comparisons. Cohen’s Kappa was applied to evaluate reliability, with values above 0.6 indicating strong agreement among researchers [

34,

35,

36]. This comprehensive approach confirmed the robustness and validity of the competency classification results, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

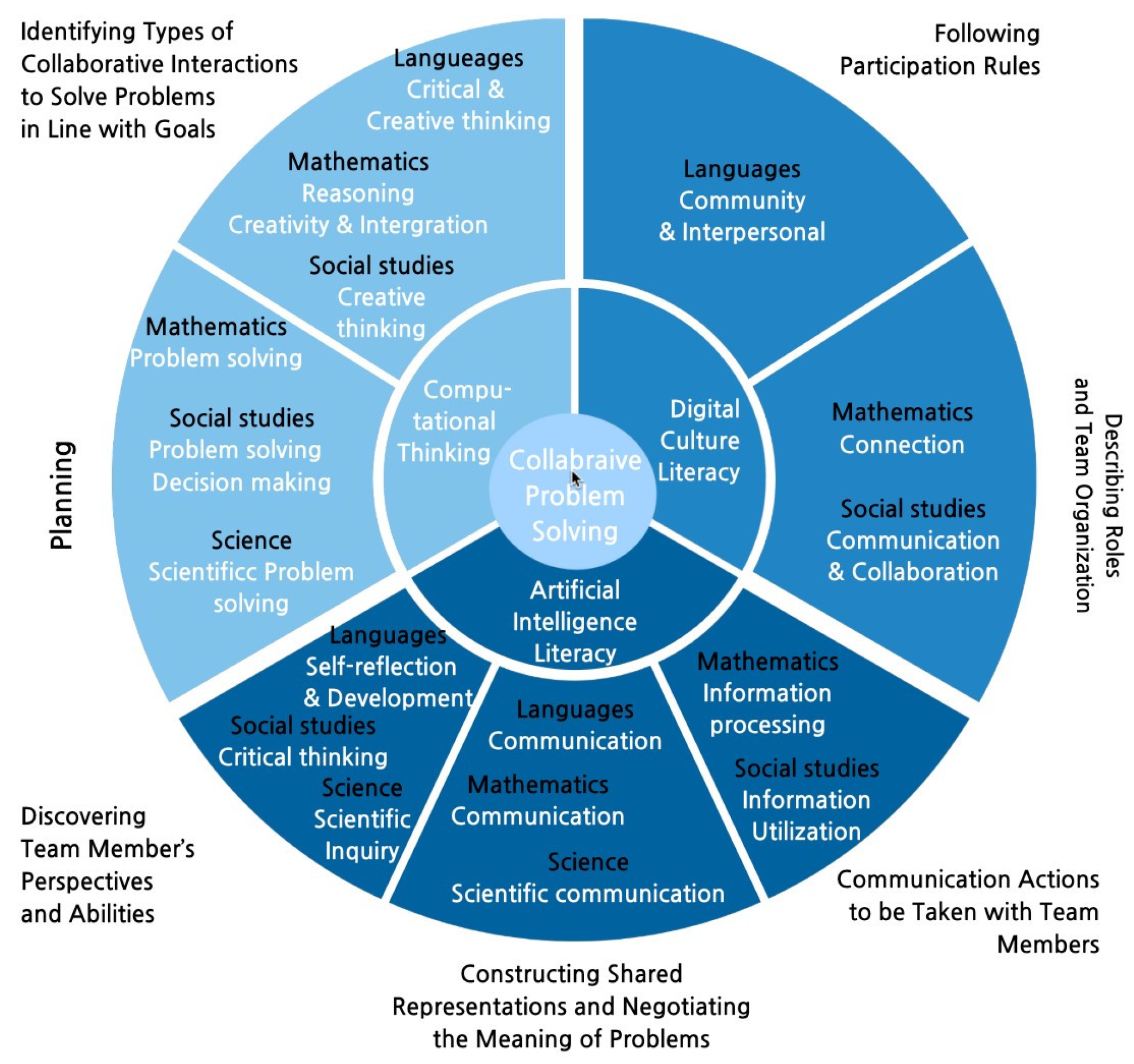

The results indicated that the curriculum included many core competencies directly related to CPS, which were supported by other competencies in a complementary role, as illustrated in

Figure 3. Consequently, this relationship and the centrality of CPS were considered to be critical factors in developing and validating the effectiveness of the educational framework.

3.2. Building Living Lab-based Collaborative Problem-Solving educational model

In developing a comprehensive Living Lab-based educational model, this study utilized a structured approach incorporating detailed factor analysis and iterative design processes. This methodological strategy aimed to effectively integrate CPS, CC, and CT within educational contexts, enhancing practical applicability and community engagement.

3.2.1. Designing Educational Activities Based on Factor Analysis of CPS, CC, and CT

To effectively integrate the competencies of CPS, CC, and CT, this study utilized validated assessment tools and expert reviews to identify and select four specific measurement variables for each competency. These selected variables include establishing collaborative methods, and applying problem-solving strategies, fair participation and feedback, and ICT usage (CPS); information gathering, listening, creative communication, and understanding others’ perspectives (CC); and problem comprehension, abstraction, algorithmic procedures, and automation (CT) [

37,

38,

39]. Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted to verify the relevance and applicability of these variables, as presented in

Table A1.

Based on these analyses, a draft educational model was constructed, consisting of sequential stages: critical observation and problem identification in the surrounding environment; recognizing and applying data-driven rules; creatively forming new rules collaboratively; abstraction and algorithm design; and expressing understanding through interactive play activities. Each stage includes structured guidance, relevant data considerations, problem-solving tasks, and cooperative interactions designed to reinforce the core competencies. This systematic approach bridges theoretical concepts with practical problem-solving skills, fostering active learner participation and the meaningful integration of computing concepts within real-world contexts.

3.2.2. Refining the Living Lab Model through Educational Community Design

The Village Living Lab is systematically structured through the community design method, emphasizing active participation, communication, and collaboration among community members. Over time, scholars have significantly evolved the community design paradigm. Yamazaki Ryo (2012), in particular, reshaped the community design concept by defining it as "designing connections among people," emphasizing participation, relationships, and communication as core values. Community design, therefore, integrates creative activities within the framework of interpersonal and community relationships, transforming public spaces into multifaceted platforms for community interaction [

40].

Based on these principles, this study proposed key elements of the Village Living Lab, which were reviewed by nine experts. These elements are outlined in

Table 2:

Building upon these paradigms and elements, stakeholders extensively discussed redefining the community concept specifically for educational applications within the Living Lab context. The concept serves as a common understanding framework, aiding judgment and shared experiences among participants. Given the multifaceted and complex nature of the Living Lab community, premature or overly rigid conceptualization could restrict learner thought and universal understanding. Therefore, experts employed a collective intelligence approach, focusing on cooperative systems between schools and external communities. Utilizing the nominal group technique (NGT), a structured method leveraging participants’ experiences, skills, and feelings, the experts generated innovative and original keyword-based ideas [

41]. These keywords were subsequently clustered according to related meanings and functions, creating an abstract conceptual framework.

Students begin by forming groups around common interests in applying technology to real-world problems, such as environmental sustainability or education. They identify relevant local experts, create collaborative strategies, and refine their projects through expert feedback. The effectiveness of these technology-based solutions is evaluated through peer, teacher, and expert feedback, along with reflections on the broader social impact and personal learning experiences. This comprehensive process integrates community collaboration, practical problem-solving, and reflective evaluation, effectively enhancing students’ competencies in collaborative problem-solving, computational thinking, and collaborative communication. Based on these structured interactions and learning processes, detailed educational design principles were systematically compiled and they are outlined in

Table A2. These principles serve as foundational components for the final Living Lab framework and evaluation methodology presented in the subsequent section, ensuring logical coherence and systematic alignment across the educational model.

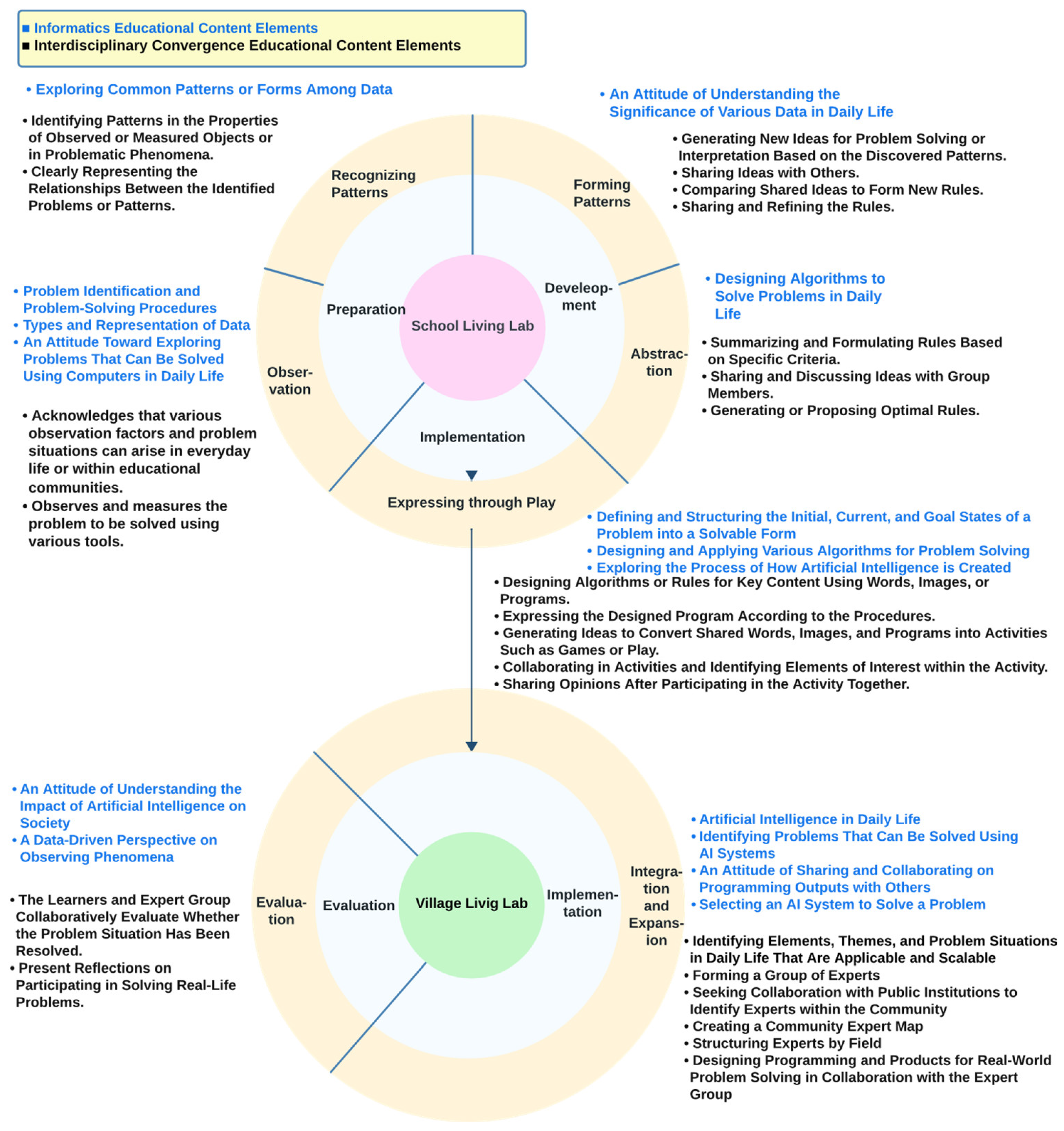

3.3. Final Living Lab Framework and Evaluation Methodology

The final Living Lab framework, as illustrated in

Figure 4, integrates both School and Village Living Lab environments into a cohesive educational model. This framework systematically embeds the core competencies of CPS, CC, and CT within practical and theoretical contexts, creating a dynamic, community-driven educational experience.

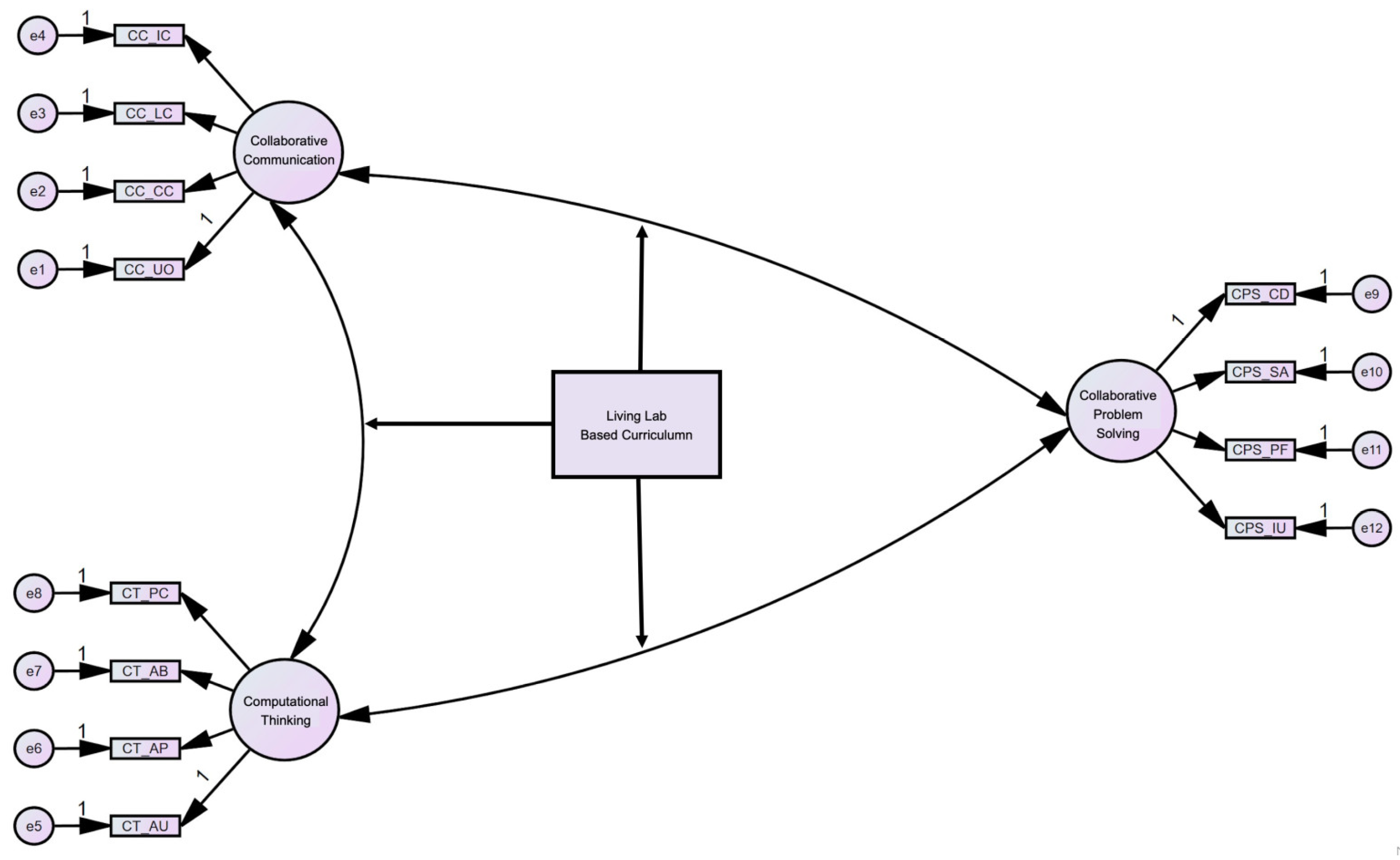

To rigorously assess the effectiveness of this framework, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and multiple regression analysis (MRA) will be conducted. CFA was chosen to statistically validate whether the identified competency factors(CPS, CT, and CC)appropriately represent the underlying theoretical constructs that guided the framework’s development. This method assesses the internal validity and reliability of competency measures, confirming the structural integrity of the proposed model.

Subsequently, MRA will be employed to examine how well the validated competency factors predicted educational outcomes within the Living Lab framework. MRA enables an understanding of the relative impact and significance of each competency (CPS, CC, and CT) on students’ overall learning achievements and skill development. Through these combined analyses, as depicted in

Figure 5, the robustness of the Living Lab framework is thoroughly evaluated, confirming its effectiveness and suitability for fostering interdisciplinary competencies and practical skills in real-world contexts.

3.4. Research Participants and Sample Selection

To rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of the Living Lab framework described in the previous sections, the study engaged 196 K-12 students (Grades 3–6) enrolled in software education aligned with the informatics curriculum. A cluster sampling method was employed, grouping students by their respective schools and class units, to ensure comprehensive representativeness across grade levels, regional backgrounds, and previous informatics experience [

42]. This methodological approach provided a diverse sample essential for thoroughly validating the proposed educational model.

This study utilized a quasi-experimental design to systematically assess the effectiveness of the Living Lab-based Collaborative Problem-Solving educational model compared to traditional teaching methods. The independent variable in this design was the Living Lab-based Collaborative Problem-Solving instructional approach, characterized by an integrated framework explicitly combining CPS, CC, and CT within informatics education. The dependent variables were the CPS, CC, and CT competencies, which were measured to observe their development over time among participants.

Ethical considerations were rigorously observed throughout the research process. The study received prior approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Korea National University of Education (Approval Number: KNUE-202302-ETC-0013-01). A complete research proposal, including participant information sheet, informed consent form, and survey instruments, was submitted for review, and necessary modifications were made to ensure full ethical compliance before implementation.

Given that the participants were minors under the age of 18, both written informed consent from legal guardians and assent from the students themselves were obtained. All participants and their guardians received detailed explanations via official school notices regarding the study’s objectives, duration, procedures, potential risks and benefits, data protection protocols, and the voluntary nature of participation. It was emphasized that participation would not affect students’ academic performance or classroom evaluations, and that withdrawal was permitted at any time without any disadvantage.

No personally identifiable information was collected during the study, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality. Participants received no financial compensation or academic incentives. Additionally, procedures were in place to respect the autonomy of participants, including the immediate withdrawal and disposal of any data upon request. In practice, no participants withdrew from the study.

This careful adherence to ethical standards reinforced the reliability and integrity of the study, supporting a valid interpretation of the outcomes presented in the subsequent results section.

To enable a clear comparative analysis, two distinct groups were established. The experimental group participated in Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model-based lessons designed to align informatics concepts closely with community-driven tasks, explicitly incorporating iterative computational activities and structured communication training. Conversely, the control group experienced traditional teacher-led instruction aimed at the same curricular objectives but without systematic integration into real-world problem-solving scenarios or specialized communication strategies. Both groups underwent an identical 15-week instructional period, and standardized lesson outlines and assessment guidelines were provided to instructors to control for potential biases.

Pre-tests and post-tests were conducted to accurately measure changes in students’ CPS, CC, and CT competencies before and after the instructional period. This measurement approach enabled the precise tracking of students’ growth in collaborative abilities, communication effectiveness, and computational thinking skills attributed specifically to the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model instructional method. By comparing outcomes between the experimental and control groups, this study aimed to determine whether targeted, community-oriented instructional practices produced statistically significant improvements in these key competencies.

4. Results

The effectiveness of the Living Lab-based educational model was rigorously evaluated through detailed pre- and post-test comparisons between control and experimental groups across several core competencies.

Table 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the statistical findings, clearly illustrating differences in competency development between the two instructional approaches.

In the control group, which experienced traditional instructional methods, improvements were minimal and limited to specific competencies such as ICT usage (Factor 4), information gathering (Factor 5), and algorithmic procedures (Factor 11). These findings indicate that while traditional instructional methods may address certain isolated competencies, they fall short in comprehensively enhancing broader competencies, particularly those requiring complex cognitive processing and collaborative interactions. This limited improvement underscores the constraints inherent in conventional teaching methods, highlighting their inadequacy in fostering the holistic development of CPS, CC, and CT. In stark contrast, students exposed to the experimental group, utilizing the structured and community-oriented Living Lab-based educational model, demonstrated substantial and widespread competency advancements. Specifically, significant gains were documented in applying problem-solving strategies (Factor 2), fair participation and feedback (Factor 3), ICT usage (Factor 4), listening skills (Factor 6), creative communication (Factor 7), understanding others’ perspectives (Factor 8), problem comprehension (Factor 9), algorithmic procedures (Factor 11), and automation (Factor 12). These substantial improvements suggest that the Living Lab-based educational model, with its emphasis on authentic, iterative, and community-linked problem-solving tasks and structured communication practices, effectively addresses the multidimensional nature of these competencies. Students in this group were clearly able to develop more sophisticated, integrated skill sets, reflecting a deeper cognitive and interpersonal engagement fostered by the structured experiential learning environment.

4.1. Pre- and Post-Test Comparisons within Control and Experimental Groups

The clear contrast between the outcomes of the control and experimental groups highlights the importance and efficacy of systematically structured, authentic, and community-oriented instructional approaches. These findings emphasize the necessity of embedding iterative computational activities, structured collaborative interactions, and explicit communication training within educational frameworks. Furthermore, these robust comparative results lay a solid foundation for subsequent analytical procedures, including multiple regression analyses, to further elucidate predictive relationships among the competencies fostered by the Living Lab-based educational model. This detailed investigation helps clarify the model’s capability to support comprehensive, sustainable competency development, crucial for addressing real-world interdisciplinary challenges.

4.2. Multiple Regression Analysis

To further explore the predictive relationships among competencies enhanced by the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model, detailed multiple regression analyses were conducted, as summarized in

Table 4. These analyses aimed specifically to identify how CC and CT competencies specifically influenced CPS and its individual sub-factors. The comprehensive results and interpretations for each specific analysis are elaborated below.

In assessing the establishment of collaborative methods, the analysis revealed four significant predictive competencies: problem comprehension (, ), creative communication (, ), automation (, ), and understanding others’ perspectives (, ). Collectively, these variables explained 43.1% of the variance. Problem comprehension’s significance underscores the need for a clear, shared understanding of collaborative objectives. Creative communication again emerged as essential, highlighting its role in fostering innovative and inclusive interaction methods. Automation’s contribution indicates the beneficial integration of structured and efficient processes to enhance collaborative effectiveness. Lastly, understanding others’ perspectives underscores empathy and effective interpersonal dynamics as vital to establishing cooperative working environments.

The multiple regression analysis for the application of problem-solving strategies identified problem comprehension (, ) and automation (, ) as significant predictors, explaining 46.2% of the variance. The pivotal role of problem comprehension reaffirms its central importance, reflecting how well students grasp the complexity and nuances of a problem before selecting appropriate strategies. Automation’s significant contribution suggests the efficient, systematic application of standardized processes enhances the consistent implementation of strategic solutions. This finding emphasizes the need for educational approaches that systematically guide students in structured, automated problem-solving methods.

For fair participation and feedback, significant predictors included problem comprehension (, ), abstraction (, ), and listening skills (, ). Together, these variables accounted for 35.2% of the variance. Problem comprehension’s predictive strength suggests that a clear, collective understanding of group tasks facilitates equitable participation. Abstraction’s contribution points to the importance of generalizing key ideas and effectively communicating these during collaborative feedback processes. The significant predictive role of listening skills emphasizes active and empathetic engagement with peers’ contributions, enhancing fairness and constructive group interaction.

ICT usage analysis indicated that problem comprehension (, ), information gathering (, ), and abstraction (, ) were significant predictors, collectively explaining 42.7% of the variance. The strong predictive impact of problem comprehension highlights the necessity of accurately interpreting and understanding problems to effectively utilize ICT tools. Information gathering underscores the importance of effectively sourcing and integrating data and resources via ICT platforms, while abstraction emphasizes simplifying and generalizing complex information into accessible formats for efficient technology-driven solutions.

These multiple regression analyses, as detailed in

Table 4, collectively underscore the interconnectedness of the competencies developed through the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model. Each analysis reveals distinct yet complementary roles of computational thinking, collaborative communication, and structured problem-solving skills, further validating the integrated approach of the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model framework in achieving comprehensive educational outcomes.

5. Discussion

5.1. Interpretation of Findings

The results of this study highlight the effectiveness of the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model in significantly enhancing elementary students’ competencies in collaborative problem-solving (CPS) and computational thinking (CT). The Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model-which integrates real-world, community-linked tasks into informatics education-facilitated substantial improvements in various critical areas, including problem comprehension, algorithmic thinking, abstraction, automation, and ICT usage. These outcomes align closely with existing research indicating that authentic, structured, and contextually meaningful tasks significantly contribute to deeper cognitive engagement, enhanced learning retention, and practical skill application. Specifically, the experimental group’s substantial gains in problem comprehension reflect the students’ increase ability to thoroughly analyze and understand complex problems before devising strategic solutions. This aligns with the recognized importance of initial problem identification and comprehension as foundational steps in effective problem-solving processes. Additionally, improvements in algorithmic thinking and automation suggest that students were effectively guided in adopting structured, systematic approaches, enabling them to apply learned problem-solving strategies consistently and efficiently. Enhanced abstraction skills indicate that students successfully learned to distill and generalize complex information, which is essential for transferring knowledge and skills across varied contexts.

Despite these considerable advancements in CPS and CT competencies, the observed improvements in CC were comparatively modest, particularly concerning creative communication, active listening, and understanding others’ perspectives. This discrepancy highlights the inherent complexity of developing interpersonal communication skills, which typically require more extensive, deliberate instructional support compared to technical competencies. Communication involves nuanced, subtle interpersonal dynamics and social interactions that may not naturally emerge from group tasks without explicit intervention. The findings suggest that collaborative communication skills necessitate structured and targeted instructional strategies, such as guided reflective dialogues, structured feedback mechanisms, empathy-building exercises, and explicit practice in perspective-taking and active listening.

Therefore, this study underscores the need for comprehensive instructional frameworks that balance the explicit teaching of technical and cognitive skills with targeted communication strategies. By explicitly incorporating structured and reflective communication practices within educational interventions, educators can effectively address the complexity of communication skill development, thereby promoting balanced and holistic competency enhancement. These considerations identify both the strengths and limitations of the current LL-CPS model, indicating specific areas for instructional refinement to optimize student learning outcomes comprehensively.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This research study contributes significant theoretical advancements in informatics education by introducing and validating the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model. The Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model presents a comprehensive and integrated framework that sustainably develops core competencies in CPS, CC, and CT within authentic community-linked contexts. This approach significantly extends beyond traditional, fragmented competency development methods by highlighting systematic interconnections among these essential competencies. Furthermore, this study provides empirical evidence supporting the theoretical assertion that explicitly addressing communication competencies through structured instructional interventions is critical. It advances theoretical understanding by clearly demonstrating how structured and deliberate communication training enhances interpersonal skill development, which is vital for effective collaboration and sustained educational outcomes.

5.3. Practical Implications

This study offers substantial practical implications for educators and instructional designers by detailing a structured, systematic instructional approach through the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model. Practically, the model’s clearly delineated instructional stages—preparation, development, execution I, execution II, and evaluation—provide educators with actionable strategies that can be directly implemented in classroom settings. Each stage outlines specific activities-from initial problem identification and data collection to solution refinement, evaluation, and reflection-facilitating clear and coherent instructional planning.

Moreover, the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model’s dual structure, consisting of the School Living Lab and Village Living Lab, extends the learning environment beyond traditional classroom boundaries, enabling meaningful engagement with real-world community challenges. This extended approach significantly enhances student motivation, as learners actively participate in authentic, impactful tasks, experiencing direct connections between academic content and real-life applications. Educators are encouraged to integrate targeted and structured communication-focused strategies into their instructional practices. Methods such as guided reflective dialogues, structured peer feedback, explicit instruction in active listening, empathy training, and role-playing activities are emphasized. These structured interventions are designed to systematically cultivate students’ collaborative communication skills, addressing identified gaps in typical instructional practices. Additionally, the successful implementation of the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model necessitates ongoing professional development for educators. Continuous training programs should equip teachers with competencies in interdisciplinary instruction and data-driven problem-solving, and facilitate collaborative and community-oriented learning experiences. Regular workshops, peer mentoring, and professional learning communities can provide essential support for educators, ensuring sustained instructional effectiveness and adaptability to evolving educational demands.

Overall, by adopting the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model, educators gain a robust framework that promotes the comprehensive, sustainable development of key competencies, preparing students effectively for collaborative, interdisciplinary problem-solving in diverse real-world contexts.

5.4. Policy Implications

From a policy standpoint, the findings advocate for curricular frameworks that emphasize interdisciplinary, collaborative, and real-world problem-solving tasks. Policymakers should ensure adequate resource allocation for technology integration, facilitate robust school-community partnerships, and adopt flexible, comprehensive assessment methods that value both collaborative processes and outcomes. Recognizing and explicitly supporting structured communication instruction within these frameworks can significantly enhance holistic educational outcomes, preparing students to navigate complex, technology-driven societies effectively.

5.5. Future Research Directions

This research suggests multiple promising areas for future inquiry. Longitudinal studies could explore how competencies, particularly communication skills, develop over extended periods under the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model. Comparative studies across different educational contexts and cultural settings could provide insights into effectively adapting the educational model more broadly. Additionally, the incorporation of advanced technological tools, such as AI-driven analytics, could offer valuable insights into real-time communication dynamics, further refining instructional methods and enhancing their effectiveness.

6. Conclusions

This study establishes the Living Lab-based Collaborative Problem-Solving educational model as an effective and sustainable approach for developing elementary students’ collaborative problem-solving, computational thinking, and- to a lesser degree-collaborative communication competencies. Through the structured integration of authentic, community-oriented tasks, the Living Lab-based collaborative problem-solving educational model significantly enhances critical cognitive and technical skills essential for problem-solving in real-world contexts. However, explicit and targeted instructional strategies are necessary to fully address the identified gaps relating to communication skill development.

The theoretical, practical, and policy implications presented emphasize the model’s comprehensive and sustainable nature, highlighting opportunities for further refinement and application. Future research is encouraged to explore longitudinal effects, cross-contextual adaptability, and technological integration in order to continually enhance instructional effectiveness. Ultimately, the Living Lab-based educational model offers a robust framework that prepares learners comprehensively to meet complex collaborative and technological challenges, effectively contributing to the goal of building a sustainable and interconnected future.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Descriptive statistical results of selected competency variables

Table A1.

Descriptive statistical results of selected competency variables

| Competency |

Variable |

M |

SD |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

| CPS |

Establishing collaborative methods |

3.43 |

0.96 |

-0.35 |

-0.39 |

| |

Applying problem-solving strategies |

3.48 |

0.85 |

0.15 |

-0.86 |

| |

Fair participation and feedback |

3.54 |

0.88 |

0.16 |

-1.38 |

| |

ICT usage |

3.43 |

0.86 |

0.11 |

-0.66 |

| CC |

Information gathering |

3.49 |

0.95 |

-0.02 |

-1.16 |

| |

Listening |

3.35 |

0.96 |

0.13 |

-0.91 |

| |

Creative communication |

3.34 |

1.06 |

-0.22 |

-0.84 |

| |

Understanding others’ perspectives |

3.44 |

0.89 |

0.06 |

-0.74 |

| CT |

Problem comprehension |

3.49 |

0.94 |

-0.51 |

0.03 |

| |

Abstraction |

3.43 |

0.91 |

-0.01 |

-0.60 |

| |

Algorithmic procedures |

3.37 |

0.99 |

0.04 |

-0.97 |

| |

Automation |

3.49 |

0.92 |

0.03 |

-0.82 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Educational design principles and descriptions

Table A2.

Educational design principles and descriptions

| Design Principle |

Description |

| Observation |

Students explore their school or community, identifying areas for improvement [43]. They select a specific issue to investigate [44]. Learners determine the types of data needed to address their chosen problem [45]. They collect and measure relevant information, including opinions from peers or community members [46]. |

| Recognizing Patterns |

By analyzing collected data, students identify emerging pattern, test initial hypotheses, and predict possible trends [47]. Students examine how identified patterns relate to their selected problem [48,49]. They visually map connections between patterns and viable solutions. |

| Forming Patterns |

Learners reflect on the significance of collected data, documenting insights and refining problem definitions [47,50]. Students generate diverse ideas to solve the issue recording multiple possibilities and evaluating their feasibility [51]. |

| Abstraction |

Small-group discussions allow learners to merge overlapping concepts and refine solutions [52]. Feedback loops ensure iterative improvements. Students focus on essential components of the problem [53,54]. They design simplified algorithms to capture key solution principles [55,56]. |

| Expressing through Play |

Learners use creative play to represent problem states and transitions [57,58]. Algorithmic thinking is applied to plan sequential steps toward a solution. Students form specialized teams based on IT applications [16], identifying areas where additional knowledge is required. |

| Implementation |

With teacher guidance, learners create an expert map, identifying professionals who can provide insights. Through direct communication or virtual meetings, students collaborate with specialists to refine their project ideas [59,60]. |

| Evaluation |

Students assess whether their proposed solution effectively addresses the problem [61,62]. Feedback is collected from peers, teachers, and community stakeholders [63,64]. Learners examine broader ethical and societal considerations related to IT. Findings are synthesized into presentations highlighting computational solutions and social responsibilities [65,66]. |

References

- Schwab, K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution; Crown Currency, New York: 2017.

- Brynjolfsson, E., McAfee, A. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. W. W. Norton & Co, New York, NY, USA: 2014 pp. 306. 978-0-393-23935-5.

- Shenkoya, T. , Kim, E. Sustainability in Higher Education: Digital Transformation of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and Its Impact on Open Knowledge. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leopold, T.A., Ratcheva, V.S., Zahidi, S. The Future of Jobs Report 2018: Insight Report Centre for the New Economy and Society. Technical report, World Economic Forum. 2018. 978-1-944835-18-7.

- Di Battista, A., Grayling, S., Hasselaar, E., Leopold, T., & Li, R., Rayner, M., Zahidi, S. The Future of Jobs Report 2023. World Economic Forum. 2023. 978-2-940631-96-4.

- Al-Dokhny, A. , Alismaiel, O., Youssif, S., Nasr, N., & Drwish, A., Samir, A. Can Multimodal Large Language Models Enhance Performance Benefits Among Higher Education Students? An Investigation Based on the Task–Technology Fit Theory and the Artificial Intelligence Device Use Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, N. , Lu, Z., Gao, Y. Towards artificial general intelligence via a multimodal foundation model. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 3094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoE. The National Framework for the Elementary and Secondary Curriculum. Technical report, Ministry of Education. 2022.

- Seong, J.E. , Jeong, S.H., Han, K.Y. Analysis of Living Lab Cases in R&D Initiatives for Solving Societal Problems and Challenges. Journal of Science and Technology Studies. [CrossRef]

- Seong, J. , Han, K., Song, W., Kim, M. Current Status and Tasks of Campus Living Labs as a New Model for Innovation. The Journal of Social Science. [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, M.R.; Mikkelsen, B.E. Is a Living Lab Also a Learning Lab?—Exploring Co-Creational Power of Young People in a Local Community Food Context. Youth 2023, 3, pp–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD PISA 2015 Collaborative Problem-Solving Framework. OECD Publishing, Paris: 2017. [CrossRef]

- Fiore, S., Graesser, A., Greiff, S., Griffin, P., Gong, B., Kyllonen, P., Massey, C., O’Neil, H., Pellegrino, J., Rothman, R., Soulé, H., von Davier, A. Collaborative Problem Solving: Considerations for the National Assessment of Educational Progress. National Center for Education Statistics, Alexandria, VA: 2017.

- Tongal, A. , Yıldırım, F.S., Özkara, Y., Say, S., Erdoğan, Ş. Examining Teachers’ Computational Thinking Skills, Collaborative Learning, and Creativity Within the Framework of Sustainable Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McComb, S. , Kennedy, D. Team Communication in Theory and Practice. In: McComb, S., Kennedy, D. (Eds.), Computational Methods to Examine Team Communication: When and How to Change the Conversation. Springer International Publishing, Cham: Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T. Learning Together and Alone: Cooperative, Competitive, and Individualistic Learning. Allyn and Bacon: 1999. 978-0-205-28771-0.

- Wing, J.M. Computational Thinking. Communications of the ACM. [CrossRef]

- Grover, S. , Pea, R. Computational Thinking in K–12: A Review of the State of the Field. Educational Researcher. [CrossRef]

- Grover, S. , Pea, R. Computational Thinking: A Competency Whose Time Has Come. Computer Science Education: Perspectives on Teaching and Learning in School. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I. , Martin, F., & Denner, J., Coulter, B., Allan, W., Erickson, J., & Malyn-Smith, J., Werner, L. Computational Thinking for Youth in Practice. ACM Inroads. [CrossRef]

- Seong, J.E. , Jeong, S.H., Han, K.Y. Analysis of Living Lab Cases in R&D Initiatives for Solving Societal Problems and Challenges. Journal of Science and Technology Studies. [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A. , López, R., Pereira, F.J., Blanco Fontao, C. Impact of Cooperative Learning and Project-Based Learning through Emotional Intelligence: A Comparison of Methodologies for Implementing SDGs. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seong, J. , Han, K., Song, W., Kim, M. Current Status and Tasks of Campus Living Labs as a New Model for Innovation. The Journal of Social Science. [CrossRef]

- He, Z. , Wu, X., Wang, Q., Huang, C. Developing Eighth-Grade Students’ Computational Thinking with Critical Reflection. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J. , Yuan, B., Sun, M., Jiang, M., & Wang, M. Computer-Based Scaffolding for Sustainable Project-Based Learning: Impact on High- and Low-Achieving Students. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X. , Chu, X., Chai, C.S., Jong, M.S.Y., Istenic, A., Spector, M., Liu, J.-B., & Yuan, J., Li, Y. A Review of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education from 2010 to 2020. Complexity 2021, 2021, 8812542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, E.S. Pacurariu, R.L. Bîrgovan, A.L. Cioca, L.I. Szilagy, A.; Moldovan, A.; Rada, E.C. A Systematic Review of Living Labs in the Context of Sustainable Development with a Focus on Bioeconomy. Earth 2024, 5, 812–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ROGERS, Steven, et al. Experiential and authentic learning in a Living Lab: the role of a campus-based Living Lab as a teaching and learning environment. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S. , Westerlund, M., Nyström, A. G. Living Labs as Open-Innovation Networks: A New Approach to Innovation Management. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. [CrossRef]

- Son, J. , Kim, T. Competency Analysis of Elementary Interdisciplinary Informatics Education Focused on Improving Collaborative Problem Solving Ability for the 2022 Revised Educational Curriculum. The Journal of Korean Association of Computer Education. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A. Similarity measures for text document clustering. InProceedings of the sixth new zealand computer science research student conference (NZCSRSC2008), Christchurch, New Zealand; 2008. 4. pp. 9-56.

- Chowdhury, Gobinda G. Introduction to modern information retrieval. Facet publishing: 2010.

- Singhal, Amit. Modern information retrieval: A brief overview. IEEE Data Eng. Bull. 2001, 24(4), pp. 35-43.

- Denzin, N.K. The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods (1st ed.). Routledge: 2009. [CrossRef]

- Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ. The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum. [CrossRef]

- Heale R, Forbes D. Understanding triangulation in research. Evid Based Nurs. 16(4), 98. [CrossRef]

- OECD. PISA 2015 Assessment and Analytical Framework: Science, Reading, Mathematic, Financial Literacy and Collaborative Problem Solving. OECD Publishing: 2017. 978-92-64-28182-0.

- Sung, J. Assessing young Korean children’s computational thinking: A validation study of two measurements. Educ Inf Technol 2022, 27, pp–12969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novıana, Ayu, et al. Development and validation of collaboration and communication skills assessment instruments based on project-based learning. Journal of Gifted Education and Creativity. [CrossRef]

- Ryō, Y, Komyunitī, D. The Age of Community Design. Chūkō Shinsho: Tokyo: 2012. 978-89-70-59653-2.

- Delbecq, Andre L., Andrew H. Van de Ven. A group process model for problem identification and program planning. The journal of applied behavioral science. [CrossRef]

- Ahrens,A. , Zascerinska, J.Principles of Sampling in Educational Research in Higher Education. Society, Integration, Education: Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference 2015, 1, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. SAGE Publications: 2017. 978-15-06-33618-3.

- Glover, A. , Stewart, S. Using a Blended Distance Pedagogy in Teacher Education to Address Challenges in Teacher Recruitment. Teaching Education. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W., Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. SAGE Publications: 2017. 978-14-83-34698-4.

- Mariani, M.M. , Machado, I., Magrelli, V., Dwivedi, Y.K. Artificial Intelligence in Innovation Research: A Systematic Review, Conceptual Framework, and Future Research Directions. Technovation 2023, 122, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, J.M. Computational Thinking. Communications of the ACM. [CrossRef]

- Jonassen, D. Learning to Solve Problems: A Handbook for Designing Problem-Solving Learning Environments. Learning to Solve Problems: A Handbook for Designing Problem-Solving Learning Environments 2010, 1, 1–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council, N.R. Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC: 2012. [CrossRef]

- Engler, J. O. , Abson, D. J., von Wehrden, H. Navigating cognition biases in the search of sustainability. Ambio 2019, 48, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, M.-F. , Belghiti, K., Auriac Slusarczyk, E. Philosophy for Children and the Incidence of Teachers’ Questions on the Mobilization of Dialogical Critical Thinking in Pupils. Creative Education 2017, 8, pp–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D.L. , Bransford, J. A Time for Telling. Cognition and Instruction 1998, 16, 475–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wing, J.M. Computational Thinking and Thinking about Computing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2008, 366, 3717–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, E. , Foverskov, M. Rehearsing and Performing in Design and Living Labs: Situated, Relational, and Embodied Participatory Design Roles in Partnerships. In: Proceedings of the Participatory Design Conference. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 2024. pp. 98–111. [CrossRef]

- Cormen, T.H., Leiserson, C.E., Rivest, R.L., Stein, C. Introduction to Algorithms. MIT Press: 2022 978-02-62-04630-5.

- Di Eugenio, B. , Fossati, D., Green, N. Intelligent Support for Computer Science Education: Pedagogy Enhanced by Artificial Intelligence, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root-Bernstein, R. Arts and crafts as adjuncts to STEM education to foster creativity in gifted and talented students. Asia Pacific Education Review 2015, 16, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnamnia, N. , Kamsin, A., Ismail, M.A.B., Hayati, A. The Effective Components of Creativity in Digital Game-Based Learning Among Young Children: A Case Study. Children and Youth Services Review 2020, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normore, A, Mitch J, Larry L, eds. Handbook of Research on Strategic Communication, Leadership, and Conflict Management in Modern Organizations, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Resta, P. , Laferrière, T. Technology in Support of Collaborative Learning. Educational Psychology Review. [CrossRef]

- Black, P. ,Wiliam, D. Assessment and Classroom Learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice. [CrossRef]

- Boud, D. , Cohen, R., Sampson, J. Peer Learning and Assessment. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education. [CrossRef]

- Webb, Mary E. Challenges for IT-enabled formative assessment of complex 21st century skills. Technology, knowledge and learning 2018, 23, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, B. , Dede, C.,& Means, B. Teaching and technology: New tools for new times. Handbook of research on teaching 2016, 5, 1269–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. Experience and education. In The educational forum 1986, September 50(3). pp. 241-252. Taylor & Francis Group. [CrossRef]

- Acar, S. , Dumas, D., Organisciak, P., Berthiaume, K. Measuring original thinking in elementary school: Development and validation of a computational psychometric approach. Journal of Educational Psychology. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).