1. Introduction

In the era of globalization, maritime transportation is not only a key driver of international trade and economic development but also the backbone of the global supply chain, connecting markets and cultures around the world. As global shipping rapidly expands, growing attention has been paid to the safety and efficiency of vessels. Maritime transport plays an indispensable role in maintaining supply chain stability, promoting economic growth, and protecting the marine environment. Against this backdrop, this study aims to develop a ship detention risk prediction model under Port State Control (PSC) using machine learning techniques, specifically the Random Forest algorithm. The focus is on the PSC inspections and detention cases in the Port of Singapore, with the goal of enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of maritime safety management. As a vital artery of the global economy, maritime transport is invaluable in facilitating international trade and ensuring the stability of global markets. However, the increasing volume of seaborne traffic also raises the risk of maritime accidents, which not only endanger crew and cargo but may also inflict irreversible damage on the marine environment. Therefore, improving vessel safety and reducing transportation risk has become a critical issue in maritime research.

Port State Control (PSC) is an internationally recognized maritime safety and environmental protection measure designed to ensure that foreign ships in port comply with international standards, thereby reducing the likelihood of maritime accidents and environmental pollution. Nevertheless, the diversity of ship types and the complexity of maritime operations pose considerable challenges to port states during inspections. Thus, developing a model capable of effectively predicting ship detention risk holds significant practical value in improving inspection efficiency and guiding shipping companies in enhancing vessel management.

According to UNCTAD [

1], despite the impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war and the COVID-19 pandemic, Asia remains the world’s largest hub for maritime cargo handling. This study uses PSC inspection data under the Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding (Tokyo MoU), focusing on the Port of Singapore. Situated in a key geographical location in Asia, Singapore is one of the busiest ports in East and Southeast Asia. Its strategic position makes it a critical node in international trade, which results in a high demand for ship inspections. Additionally, Singapore has a well-established legal framework and port management system, making its inspection practices more representative. The port is also equipped with advanced inspection facilities and trained personnel, which contribute significantly to the efficiency and accuracy of PSC procedures. Therefore, Singapore’s inspection practices offer valuable insights for analysis.

This study conducts an in-depth analysis of PSC inspection data from the Port of Singapore from 2014 to 2023, starting from the implementation of the New Inspection Regime (NIR) under the Tokyo MoU. By applying the Random Forest algorithm, this research not only predicts ship detention risk but also explores various factors affecting maritime safety. Through the application of machine learning, the study aims to provide new analytical approaches and strategic recommendations for maritime safety management. The findings are expected to support decision-making for shipping companies, port authorities, and policymakers, while promoting a shift towards data-driven decision-making in the maritime sector. Furthermore, the results offer valuable references for other global shipping hubs and have profound implications for enhancing international maritime safety standards and promoting the sustainable development of global shipping.

2. Literature Review

Port State Control (PSC) plays a vital role in maintaining maritime safety and environmental protection by verifying that foreign ships comply with international regulations. To enhance inspection efficiency, regional Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) have adopted risk-based approaches such as the New Inspection Regime (NIR), which ranks ships based on factors like vessel type, age, flag, and inspection history. Despite these advancements, current systems still rely on fixed-weight criteria, limiting their responsiveness to emerging risks. Consequently, researchers have explored more data-oriented approaches, including statistical analysis and rule-based modeling, to refine inspection strategies and improve the fairness and consistency of ship selection. This section reviews the evolution of PSC inspection mechanisms and the key factors influencing inspection outcomes.

2.1. Development of PSC Ship Selection Mechanisms

Currently, the global Port State Control (PSC) system is composed of approximately ten regional agreements, covering the majority of the world’s ports and coastlines. Kara et al. [

2] noted that while these regimes all conduct inspections on foreign ships entering their ports based on international maritime safety and pollution prevention regulations, variations still exist in how these inspections are implemented across regions. Yang et al. [

3] mentioned that after years of preparation, the highly anticipated New Inspection Regime (NIR) was launched on January 1, 2011, representing one of the most significant transformations and modernizations in PSC systems in recent years. In their study, Yang et al. [

3] also highlighted that the NIR introduced the Ship Risk Profile (SRP), which classifies ships into different risk categories to help port states prioritize inspection intervals and frequency. Zheng [

4] pointed out that many regional memoranda have begun implementing NIR to improve PSC effectiveness. For instance, under the Tokyo MoU, the NIR—enforced since January 1, 2014—assesses vessel risk based on ship type, age, flag, recognized organization, company performance, deficiency history, and detention records, assigning weights to each factor and computing an overall risk score to determine inspection priority.

In addition to the inspection mechanisms established by PSC MoUs, many scholars have conducted research aiming to improve the fairness and efficiency of ship selection mechanisms. Cariou and Wolff [

5] applied quantile regression to explore the relationship between ship types and their deficiency profiles. Fan et al. [

6] combined binary and linear regression models to estimate the likelihood of a ship being selected for inspection. Hanninen and Kujala [

7] utilized Bayesian network models to analyze the interrelationships among various deficiencies found during PSC inspections, as well as their correlation with maritime accidents. Knapp and Franses [

8] developed a logistic regression model to predict casualty risks by integrating PSC inspection records, ship-specific information, classification societies, ownership data, flag states, and inspection frequency.

2.2. Key Factors Influencing PSC Inspection Outcomes

Fan et al. [

6] found that the likelihood of a ship being selected for inspection depends not only on its inspection history but also on specific prioritization criteria, with ship age identified as the most critical factor. Hanninen and Kujala [

7], through the application of Bayesian networks, discovered that ship type, the nature of the inspection, and the number of structural deficiencies were key indicators in explaining the causes of maritime accidents and assessing potential safety risks. Research has consistently shown that many factors significantly affect vessel risk, including ship age, type, and size.

Cariou et al. [

9]confirmed the importance of ship age by analyzing PSC databases and identifying it as a major factor influencing inspection focus and detention decisions. In a follow-up study, Cariou and Wolff [

5] found that up to 40% of detentions were associated with older vessels. The Australian CSIRO Mathematical and Information Sciences Unit [

10], after analyzing inspection records, concluded that ship age remains the most critical parameter for assessing vessel quality. Other influential factors include ship type, past inspection history, and vessel size. Knapp and Velden [

11] compared the inspection focuses of various PSC regimes and found that Paris MoU member states particularly emphasize deficiencies in ship stability, structural integrity, and safety equipment.

2.3. Summary

In summary, the Port State Control (PSC) regime has evolved into an indispensable component of the international maritime safety and environmental protection framework. With the implementation of various international conventions and the continuous revision of IMO resolutions, the PSC system has become increasingly mature in terms of inspection procedures, assessment criteria, and enforcement consistency. In particular, the adoption of the risk-based New Inspection Regime (NIR) has significantly improved the efficiency and focus of inspections.

Nevertheless, several challenges remain. First, although regional Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) provide a common institutional framework, discrepancies in enforcement standards and inspection priorities persist across regions, potentially undermining fairness and consistency. Second, inspection outcomes may still be influenced by subjective judgment, particularly in the discretionary authority of Port State Control Officers (PSCOs), indicating a need for further standardization and quantification of inspection practices. Third, current ship selection mechanisms largely rely on historical records and static indicators, limiting their capacity to identify newly emerged or high-risk vessels in advance.

To address these limitations and respond to the dynamic nature of international shipping and technological advancement, the PSC system must continue to evolve toward greater intelligence, coordination, and adaptability, thereby sustaining its central role and effectiveness in global maritime safety governance.

3. Methodology

This study adopts an empirical research design to construct and validate a predictive model for identifying ships with a high risk of deficiencies using historical PSC inspection data from the Port of Singapore. The methodology consists of data collection and processing, feature selection, model construction, and performance evaluation, as detailed below:

3.1. Data Source and Sample Description

The primary data source is the public PSC inspection results database of the Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding (Tokyo MoU). We extracted all PSC inspection records conducted at the Port of Singapore from January 2014 to December 2022, totaling 10,736 entries. Each record corresponds to a single vessel inspection and includes multiple attribute fields such as: vessel information (ship name, IMO number), technical specifications (type, gross tonnage, year built), operational data (flag state, classification society, managing company), and inspection results (number of deficiencies, detention status). We calculated vessel age (years in operation) based on the year built and inspection date. The ship risk profile (high/low risk), as classified by the Tokyo MoU, was used as an input feature. Additionally, the dataset includes company performance ratings (based on historical deficiency and detention records) and the flag state’s position on the Tokyo MoU’s black-grey-white list. Notably, only about 3.9% of inspections resulted in detentions, indicating a severe class imbalance. Using detention as the prediction target could bias the model toward predicting all vessels as non-detained for high superficial accuracy. To address this, we used “high deficiency count” as an alternative target. Based on the distribution of deficiencies and international practices, we defined a high-risk inspection as one with five or more deficiencies. This threshold aligns with Tokyo MoU’s criteria for serious substandard performance and increases the proportion of positive samples (approximately 5–10%), which is more suitable for training. Each inspection was labeled as 1 (high risk) if deficiencies ≥5, and 0 (low risk) otherwise.

3.2. Data Preprocessing

Before feeding the data into the model, we performed thorough data cleaning and transformation. Incomplete or inconsistent records were removed or corrected (e.g., records with tonnage = 0). Field values were standardized. Categorical variables (e.g., flag state, classification society, company name) were converted into numerical formats suitable for modeling. We derived new features such as operational years (age) by calculating from the build year and inspection date. The ship risk profile provided by Tokyo MoU was included as a supportive feature, but its influence was closely monitored to prevent over-reliance. For categorical features, we used One-Hot Encoding or numerical substitutions (e.g., black/grey/white list coded as 3/2/1). The processed dataset was split into training and testing sets using an 80:20 ratio. Stratified sampling was applied to preserve the distribution of high-risk cases across both sets, maintaining class balance and avoiding sampling bias.

3.3. Feature Selection

Prior to training, feature selection was conducted to optimize input variables, reduce dimensionality and noise, and enhance model performance. Given the diverse nature of initial features—ranging from vessel specifications to company and flag ratings—some variables were redundant or of little predictive value. We employed the feature importance metric from Random Forests [

12], which calculates the average contribution of each feature to impurity reduction (Gini importance). Features were ranked based on their importance scores. As expected, variables such as gross tonnage, vessel age, company performance, flag state, and risk profile had the highest weights, while identifiers like IMO number or port name were nearly irrelevant. Two strategies were used: (1) selecting the smallest subset that explains 90% of importance variance; (2) retaining the top-ranked features. Both yielded similar results. We ultimately selected seven predictive features: gross tonnage, operational years (age), company performance rating, ship risk profile, flag state list category, classification society, and vessel type. These features collectively reflect vessel size and age, management quality, inherent risk, and technical attributes—factors widely regarded as relevant in PSC contexts.

3.4. Model Development

We adopted classification algorithms to build the PSC high-risk ship prediction model. A standard decision tree was first constructed as a baseline model. Although intuitive and interpretable via recursive binary splits, single decision trees are prone to overfitting and variance from data fluctuations.

To enhance predictive performance, we introduced two ensemble learning methods: Random Forest and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [

13]. Random Forest uses Bagging by training multiple decision trees on randomly sampled data and features, reducing variance and improving stability. XGBoost, a Boosting method, trains sequential weak learners (trees) that learn from prior residuals and combines them with weighted averaging to improve accuracy. XGBoost is known for handling imbalanced data effectively and training efficiently, making it suitable for this study.

Model development was implemented using Python’s scikit-learn and xgboost libraries. We applied 5-fold cross-validation to tune hyperparameters and ensure generalizability. For Random Forest, we adjusted tree count, maximum depth, and minimum samples per leaf; for XGBoost, we tuned learning rate, max depth, and L1/L2 regularization. Grid search and cross-validation helped identify optimal parameter combinations. For example, Random Forest performance plateaued at about 100 trees with moderate depth (under 10), suggesting further complexity was unnecessary.

We also explored adjusting classification thresholds to balance precision and recall, aligned with regulatory practice favoring high recall (i.e., better to over-warn than miss a high-risk vessel).

4.5. Model Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess model performance in predicting high-risk vessels, we adopted multiple classification metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score. Accuracy reflects overall correctness but may be misleading under class imbalance. Precision measures how many ships predicted as high-risk were truly high-risk (prediction accuracy), while Recall measures how many actual high-risk ships were correctly identified (sensitivity). The F1 Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall and summarizes predictive performance for positive cases.

We also analyzed confusion matrices to assess false negatives (missed high-risk vessels) and false positives (erroneously flagged low-risk vessels). Given the operational cost of missing a high-risk vessel is higher than over-flagging, we prioritized optimizing recall.

After training, models were tested on the hold-out test set and evaluated using the above metrics. We compared the performance of the baseline decision tree, Random Forest, and XGBoost models to validate the advantage of ensemble approaches.

To enhance model interpretability, we evaluated the trained Random Forest model using permutation importance, which measures the change in model performance when each feature’s values are randomly shuffled. This approach quantifies the relative importance of each input variable by assessing its impact on prediction accuracy. For example, the model’s accuracy may significantly decrease when vessel age or flag state is permuted, indicating their strong influence on inspection risk predictions. These findings help confirm whether the model prioritizes features consistent with maritime domain knowledge, thereby improving transparency and building trust among inspectors and stakeholders.

4. Empirical Results

Through the training and testing procedures described above, we evaluated and compared the performance of the baseline Decision Tree, Random Forest, and XGBoost models in predicting high-deficiency-risk vessels.

Table 1 summarizes the key performance metrics for each model on the test dataset, while

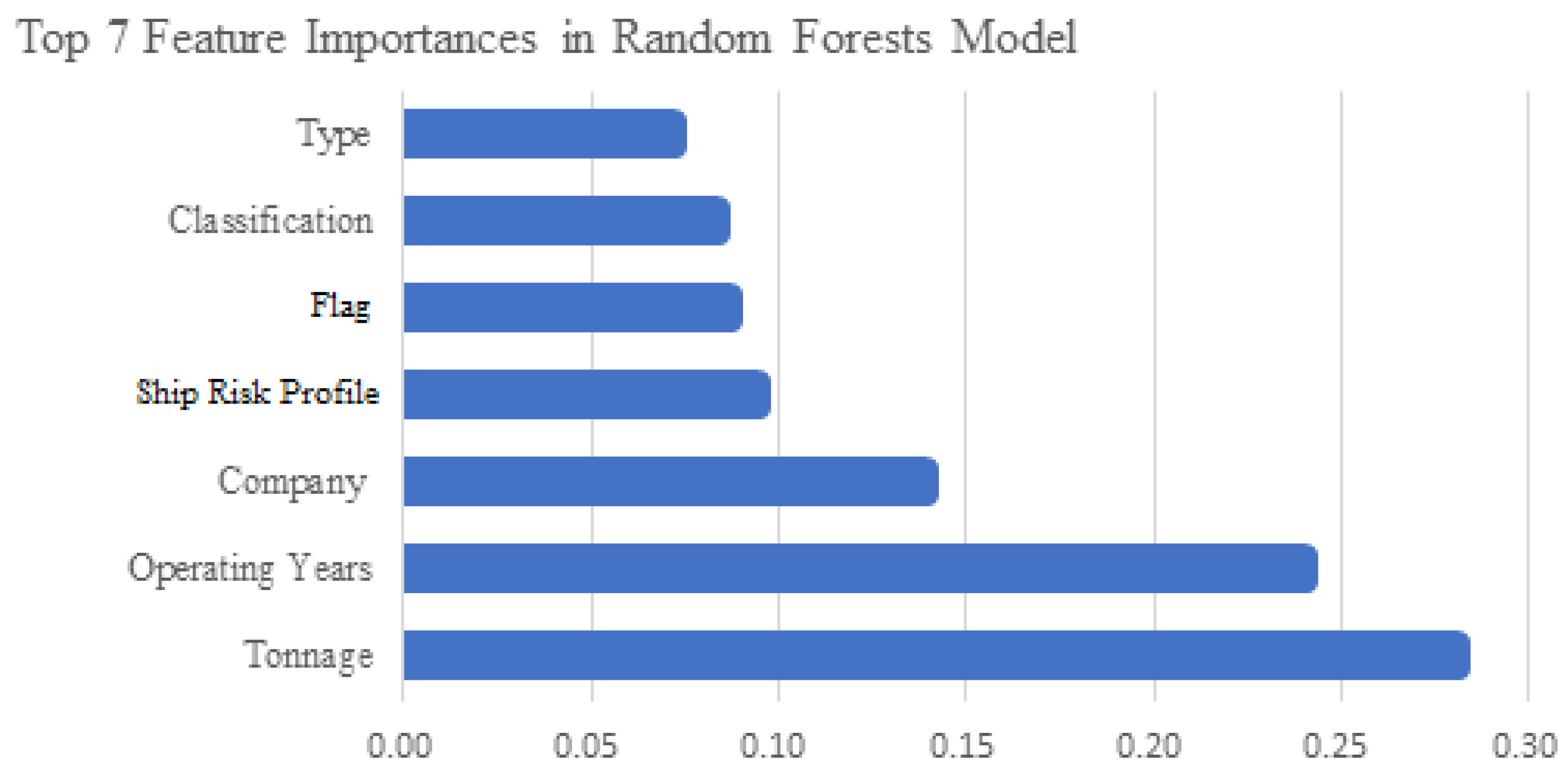

Figure 1 illustrates the feature importance rankings generated by the Random Forest model.

From

Table 1, it is evident that the Random Forest model shows a significant improvement over the baseline Decision Tree. On the test data, Random Forest achieved an accuracy of approximately 81.8%, representing a nearly 10-percentage point improvement. Its precision (80.5%) and recall (83.0%) also outperformed the Decision Tree by more than 10%, resulting in an F1 score of 0.817. Notably, the higher recall indicates that the model is more capable of capturing truly high-risk vessels (reducing false negatives), while the simultaneously improved precision suggests that false positives (misclassifying low-risk vessels) did not increase significantly—thus improving prediction reliability.

XGBoost performed similarly to Random Forest, with minor variations in some metrics. Specifically, it achieved the highest recall (84.2%), indicating excellent sensitivity toward high-risk cases, though its precision was slightly lower than that of Random Forest, suggesting more false positives. Overall, Random Forest offered a more balanced trade-off between precision and recall, with a marginally higher F1 score, which led us to select it as the primary model for further analysis. XGBoost results also reaffirm the robustness of ensemble learning compared to single decision trees and offer a viable alternative for future model optimization.

To better understand the model’s decision-making process, we analyzed the feature importance derived from the Random Forest model.

Figure 1 shows the top seven features and their relative importance weights based on the training process. Gross Tonnage and Operating Years (Vessel Age) ranked as the two most influential features, significantly outweighing others. This suggests that larger and older vessels are more likely to accumulate five or more deficiencies during inspections. On one hand, larger vessels are structurally more complex and contain more equipment, increasing potential deficiency points. On the other hand, older vessels are more prone to deterioration and may struggle to adapt to updated standards, contributing to higher deficiency rates.

Company Performance followed closely in importance, indicating that the quality of safety management by the operating company significantly influences inspection outcomes. Companies with strong safety records typically maintain rigorous internal audits and maintenance procedures, reducing the likelihood of severe deficiencies. Conversely, vessels managed by less safety-conscious companies are more prone to violations. The fourth most important variable was the Risk Profile, the Tokyo MoU’s official risk rating for the vessel at the time of inspection. It is intuitive that vessels classified as high risk are more likely to be found with numerous deficiencies. However, the model did not overly rely on this variable (its weight was lower than tonnage, age, and company rating), suggesting that the machine learning model extracted additional insights beyond merely repeating official risk scores.

The remaining features included Flag State, Classification Society, and Ship Type. The black-grey-white list status of the flag state reflects a country’s fleet compliance and regulatory quality—vessels from blacklisted states are more likely to have deficiencies. Classification Societies, as technical inspection bodies, vary in their standards and rigor; prior studies have shown their relevance to detention likelihood, and the model confirms their moderate impact. Ship Type had relatively lower importance but still contributed to prediction—possibly due to certain types such as bulk carriers or older passenger ships historically showing more deficiencies, while niche ship types (e.g., offshore support vessels) were underrepresented in the dataset.

Taken together, the model successfully identified a combination of key predictors associated with vessel deficiency risk, largely consistent with previous literature and expert experience [

6,

7,

14].

Overall, the Random Forest model demonstrated strong predictive performance and logical feature reasoning, validating the feasibility and effectiveness of using machine learning for PSC high-risk vessel prediction. It achieves high accuracy while capturing the majority of truly high-risk vessels—clearly outperforming traditional rule-based or single-factor approaches. In the next section, we will further explore the implications of these findings for maritime risk management.

5. Discussion

The PSC high-deficiency-risk ship prediction model developed in this study demonstrated strong performance and interpretability in the empirical case of the Port of Singapore. This section discusses the implications of model performance, recommendations for policy and practice, and potential limitations and areas for improvement.

5.1. Implications of Model Performance

The outstanding predictive performance of ensemble learning models such as Random Forest underscores the significant potential of machine learning approaches in PSC risk warning applications. Compared to traditional ship selection mechanisms that rely on human judgment or fixed-weight scoring rules, the model proposed in this study dynamically learns patterns from historical data, making it more adaptable to the complexity and variability of real-world scenarios. The model’s high recall (>83%) is particularly significant—it means that the vast majority of genuinely high-risk ships can be identified in time, reducing the number of “slipping through the cracks.” For port state authorities, this translates into a higher detection rate, allowing limited inspection resources to be more effectively allocated. At the same time, a precision of around 80% indicates that most ships predicted as high risk do indeed have a higher number of deficiencies, with a relatively low false positive rate. While a “better safe than sorry” approach is common in regulatory practice, excessive false positives can waste manpower and potentially alienate compliant operators. Thus, maintaining an acceptable precision level supports regulatory cost-efficiency and industry perception. The balance our model achieves between precision and recall represents a major improvement over traditional methods. Previously, port officers relying on subjective judgment may have missed high-risk ships or made inaccurate decisions due to incomplete information. The findings of this study demonstrate that big data analytics can simultaneously enhance detection accuracy and identification coverage, thereby improving the overall effectiveness of PSC inspections. Moreover, the model’s quantification of key risk factors and their relative importance provides a novel perspective for understanding PSC inspection results. For example, the high rankings of vessel age and tonnage reaffirm that older, larger ships require more attention—an insight valuable to port states and the IMO when developing inspection guidelines. The high weight assigned to company performance also suggests that regulators should strengthen oversight at the company level. Measures such as increasing inspection frequency for companies with repeated high-deficiency vessels or issuing early warnings can help improve safety management at the source.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on our findings, we propose the following recommendations for PSC regulatory policy:

(1) Integrate Intelligent Decision Support Systems: Port state authorities are encouraged to incorporate machine learning prediction models into existing PSC information systems as a powerful supplement to current risk scoring methods. This could involve developing a risk-warning platform that automatically retrieves up-to-date ship data (e.g., vessel status, recent inspections) and computes risk scores in real time for incoming ships, providing actionable insights to inspectors. Practically, the system could interface with the Tokyo MoU’s central database to offer pre-arrival risk rankings for vessels scheduled to call at ports.

(2) Optimize Inspection Resource Allocation: Using model predictions, port authorities can better allocate personnel and time. For example, senior surveyors and extended inspection windows can be assigned to predicted high-risk vessels, while low-risk ships could be fast-tracked or exempted to improve overall efficiency. This stratified risk management approach aligns with IMO regulatory trends and enhances port operational effectiveness. Importantly, implementation should emphasize transparency and fairness to prevent perceptions of discrimination. Authorities should clearly communicate key model factors and provide incentives for good performance.

(3) Strengthen International Coordination and Data Sharing: Improving model performance depends on data quality and scale. PSC MoUs and the IMO should consider building stronger data-sharing mechanisms, such as integrating PSC inspection data globally to form a comprehensive maritime safety big data platform. This would enable better tracking of vessel performance and early warnings for ships operating across regions. International coordination should also aim to standardize risk prediction metrics so that AI-assisted regulation can follow consistent frameworks across countries.

(4) Promote Industry Self-Regulation: Beyond government oversight, regulators should provide feedback to shipping companies based on model results to encourage voluntary improvement. Authorities could issue periodic reports showing a company’s fleet risk rankings, motivating them to improve performance for lower-ranked vessels. Companies could also use similar models internally to conduct pre-departure risk assessments, identifying potential issues before inspection. In the long run, as operators recognize that such models can accurately identify safety gaps, a peer pressure and incentive system may emerge—driving investments in safety and fostering a virtuous cycle of improvement.

5.3. Potential Application Scenarios

The results of this study are not only applicable to the Port of Singapore but also hold broader application potential:

(1) Regional Risk Warning Centers: Regional PSC organizations such as the Tokyo MoU could use our method to establish regional early warning centers. These centers could consolidate inspection data from member countries and generate pre-arrival risk rankings for all vessels entering the region. This would enhance regional coordination and enable tighter monitoring of high-risk ships. For instance, if a vessel with multiple deficiencies is flagged in Japan, Singapore could receive early warnings before the vessel’s arrival.

(2) Port Operations and Berthing Management: Apart from regulatory purposes, port operators could use risk predictions for operational planning. If a vessel is predicted to be high risk and likely to be detained, the port could anticipate potential delays and adjust berth allocations accordingly. Conversely, low-risk vessels could be fast-tracked to improve port throughput and service efficiency.

(3) Insurance and Finance: Ship insurers and financial institutions could incorporate such models into their risk assessment frameworks. Vessels with high predicted risk scores may indicate greater safety concerns, prompting insurers to adjust premiums or require additional surveys. Lenders could also reference safety scores when evaluating ship asset or loan risk. With quantifiable risk indicators, market mechanisms may accelerate the phasing out of high-risk assets, indirectly improving overall industry safety.

5.4. Model Limitations and Future Improvements

While this study achieved meaningful results, several limitations remain for future research to address:

(1) Data Scope Limitation: Our model is based on historical data from the Port of Singapore, which may contain region-specific or sample-specific biases. The applicability of the model to other ports or PSC systems requires further validation, as fleet composition and violation characteristics may vary. Future work could expand the dataset to include multiple countries, enhancing the model’s generalizability.

(2) Feature Completeness: Although several relevant factors were considered, some potentially important variables were not included due to data unavailability—such as crew competence (certification and training) or voyage characteristics (e.g., degradation of vessel condition after long-distance sailing). Future access to detailed records (e.g., ISM audit reports, maintenance logs) could further enhance prediction accuracy.

(3) Model Complexity and Interpretability: While ensemble models offer high performance, they are relatively “black box” in nature. We have used feature importance and SHAP analysis to improve transparency, but complex nonlinear interactions are still challenging to interpret intuitively. Future studies may explore more interpretable approaches such as rule-based models or hybrid methods that retain performance while improving explainability. Techniques such as local interpretability models or designed feature interaction indicators could also aid understanding.

(4) Real-Time Deployment: In practical applications, models need frequent updates to reflect the latest data. Our study used offline batch training and did not address real-time updating mechanisms. Future work could explore online learning techniques to dynamically adjust parameters as new PSC data become available. Moreover, deploying AI models in port IT environments requires attention to system integration, computing efficiency, and cybersecurity—areas that may benefit from collaboration with IT and systems engineering experts.

In conclusion, this study highlights the practical significance of developing a predictive model for high-risk ships under PSC in improving maritime regulatory effectiveness. It also offers actionable policy and operational recommendations. With appropriate policy support and technological investment, machine learning models could become powerful tools for port state control, helping countries effectively identify substandard ships amidst growing international traffic—ultimately safeguarding lives, assets, and the marine environment.

6. Conclusions and Future Recommendations

This study successfully developed a machine learning-based model to predict high-deficiency-risk ships under PSC and validated its effectiveness using inspection data from the Port of Singapore. By applying algorithms such as Random Forest, we demonstrated that data-driven models significantly improve the accuracy and coverage of high-risk vessel identification compared to traditional rule-based or experience-based methods.

The results indicate that vessel age, gross tonnage, company performance, and flag state are significant predictors of deficiency risk—consistent with international understanding—and quantitatively emphasize their importance. Furthermore, unlike existing risk rating systems such as the Tokyo MoU’s New Inspection Regime (NIR), our model possesses dynamic learning capabilities, uncovering hidden interactions from historical data to generate more contextually relevant predictions.

Practically speaking, this study provides a functional intelligent risk warning tool. Port state authorities can leverage it to optimize inspection resource allocation and strengthen oversight of substandard vessels. Meanwhile, shipping companies can use the model’s insights to proactively address fleet maintenance and safety management shortcomings. More broadly, this research highlights the value of machine learning in the maritime safety domain and introduces innovative thinking into traditional regulatory models, aligning with the digital transformation trends of the shipping industry.

Future Research Directions

We propose the following key areas for future research and development:

(1) Expansion of Data Scope: Apply the model to other ports or regional PSC datasets to test its cross-regional applicability. Alternatively, a generalized model can be retrained using multi-country data to identify universal risk factors. It would also be valuable to incorporate data from other MoU regimes (e.g., the Paris MoU) to compare model performance under different regulatory environments.

(2) Enhancement of Feature Engineering: Continue optimizing the model’s feature set. New features such as inspection frequency, route risk level, or the number of critical crew certifications can be explored. Feature interaction and polynomial terms can also be constructed—for example, creating a composite indicator by combining flag state category and company history—to capture more nuanced patterns. Advanced feature engineering helps uncover risk factors that may be overlooked by current rule-based systems.

(3) Model Architecture Innovation: Beyond Random Forest and XGBoost, future studies can explore advanced algorithms like Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) for prediction tasks. Though deep learning requires larger datasets and higher computational power, its ability to model complex nonlinear relationships may further enhance prediction accuracy. Additionally, ensemble approaches that combine outputs from multiple models (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, and DNNs) can exploit the strengths of different architectures to improve overall robustness.

(4) Development of a Real-Time Warning System: To move from research to practice, a real-time operational warning system must be developed. A future initiative could involve designing a software platform that integrates the prediction model, enabling automatic retrieval of new vessel data, real-time risk scoring, and alert dispatch. Incorporating a continuous learning mechanism will ensure that the model is regularly retrained or recalibrated using the latest inspection outcomes to maintain accuracy over time.

(5) Cost-Benefit and Social Impact Assessment: Subsequent studies should evaluate the potential economic and social impacts of implementing this model in practice. For instance, metrics such as the increase in major deficiency detection rates, avoided accident costs, and human resource savings from reduced unnecessary inspections can be quantified. It is also essential to assess the shipping industry’s acceptance and feedback to guide iterative improvements in model design and deployment strategies.

Developing a machine learning-driven PSC risk prediction model represents a critical step toward intelligent maritime regulation. This study lays a foundational framework, and with continued e maritime transport nrichment through more diverse datasets, refined algorithms, and real-world application, a new model of proactive prevention and precision-based port state control can be realized. Ultimately, this will contribute to reducing maritime incident rates, safeguarding lives and property at sea, and supporting the sustainable and healthy development of the global shipping industry.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding (Tokyo MoU). [Tokyo Memorandum of Understanding (Tokyo MoU)] [

https://apcis.tmou.org/public/].

References

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Review of Maritime Transport 2022. 2023.

- Kara, E. G.; Oksas, O.; Kara, G. The similarity analysis of Port State Control regimes based on the performance of flag states. Proc. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part M Journal of Engineering for the Maritime Environment. 2020, 234(3).

- Yang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Teixeira, A. P. Comparative analysis of the impact of new inspection regime on port state control inspection. Transport Policy. 2020, Volume 92, pp. 65-80. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L. The Effectiveness of New Inspection Regime on Port State Control Inspection. Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2020, 8, pp. 440-446. [CrossRef]

- Cariou, P.; Wolff, F.-C. Identifying substandard vessels through Port State Control inspections: A new methodology for Concentrated Inspection Campaigns, Marine Policy. 2015, 60, pp. 27–39. [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Luo, M.; Yin, J. Flag choice and Port State Control inspections—Empirical evidence using a simultaneous model, Transport Policy. 2014, 35, pp. 350–357. [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, M.; Kujala. P. Bayesian network modeling of Port State Control inspection findings and ship accident involvement, Expert Systems with Applications. 2014, 41, pp. 1632–1646. [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, M.; Kujala. P. Bayesian network modeling of Port State Control inspection findings and ship accident involvement, Expert Systems with Applications. 2014, 41, pp. 1632–1646. [CrossRef]

- Cariou, P.; Mejia, M. Q.; Wolff, F.-C. Evidence on target factors used for port state control inspections, Marine Policy. 2009, 33, pp. 847–859. [CrossRef]

- CSIRO Ship Inspection Decision Support System (SIDSS). Available online: www.finance.gov.au/archive/comcover/docs/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Knapp, S.; Velden, M. v. d. Visualization of differences in treatment of safety inspections across Port State Control regimes: a case for increased harmonization efforts, Transport Reviews. 2009, 29(4), pp. 499–514. [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Machine Learning. 2001, 45(1), pp. 5–32. [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining. 2016, pp. 785-794. [CrossRef]

- Heij, C.; Knapp, S. Predictive power of inspection outcomes for future shipping accidents–an empirical appraisal with special attention for human factor aspects. MARITIME POLICY & MANAGEMENT 2018. 2018, 45(5), pp. 604–621. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).