Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

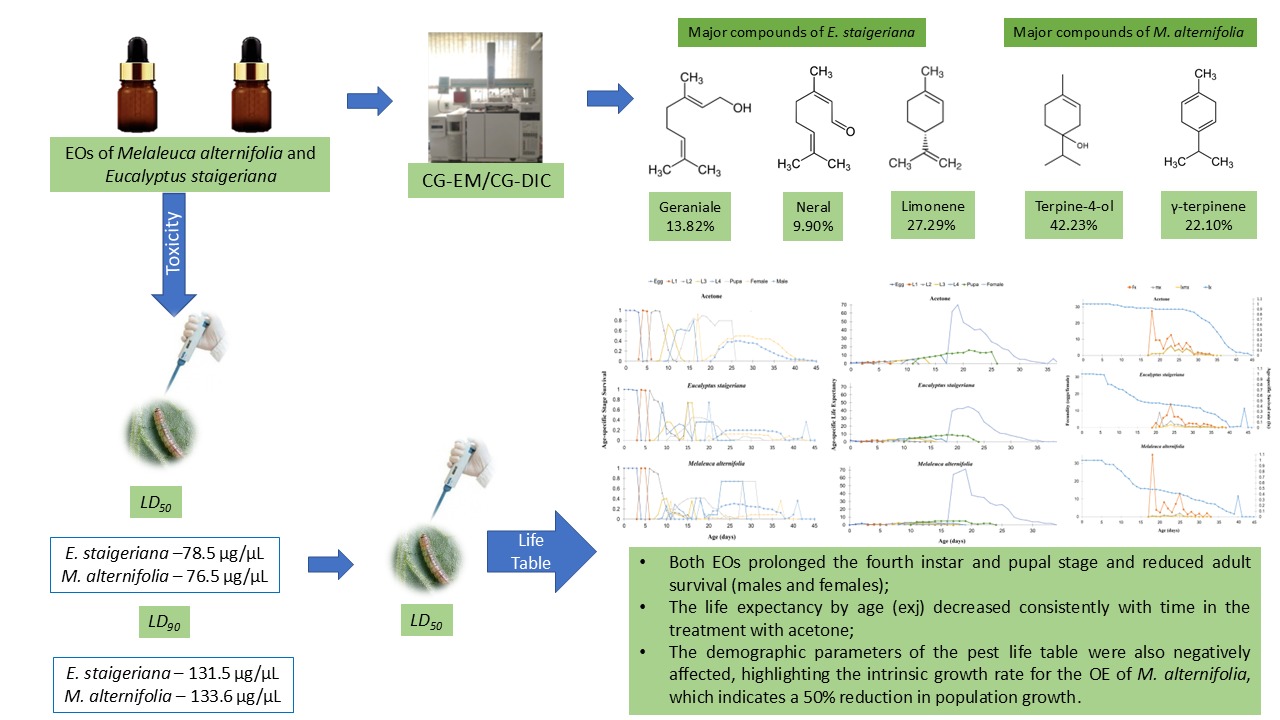

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Material and Experimental Conditions

2.2. Obtention and Chemical Characterization of EOs

2.3. Acute Toxicity of EOs in a Topical Application Against P. absoluta

2.4. Dose–Response and Time–Response Bioassays of EOs

2.5. Effects of Sublethal Doses of EOs on the Life History Parameters of P. absoluta

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Chemical Characterization of EOs

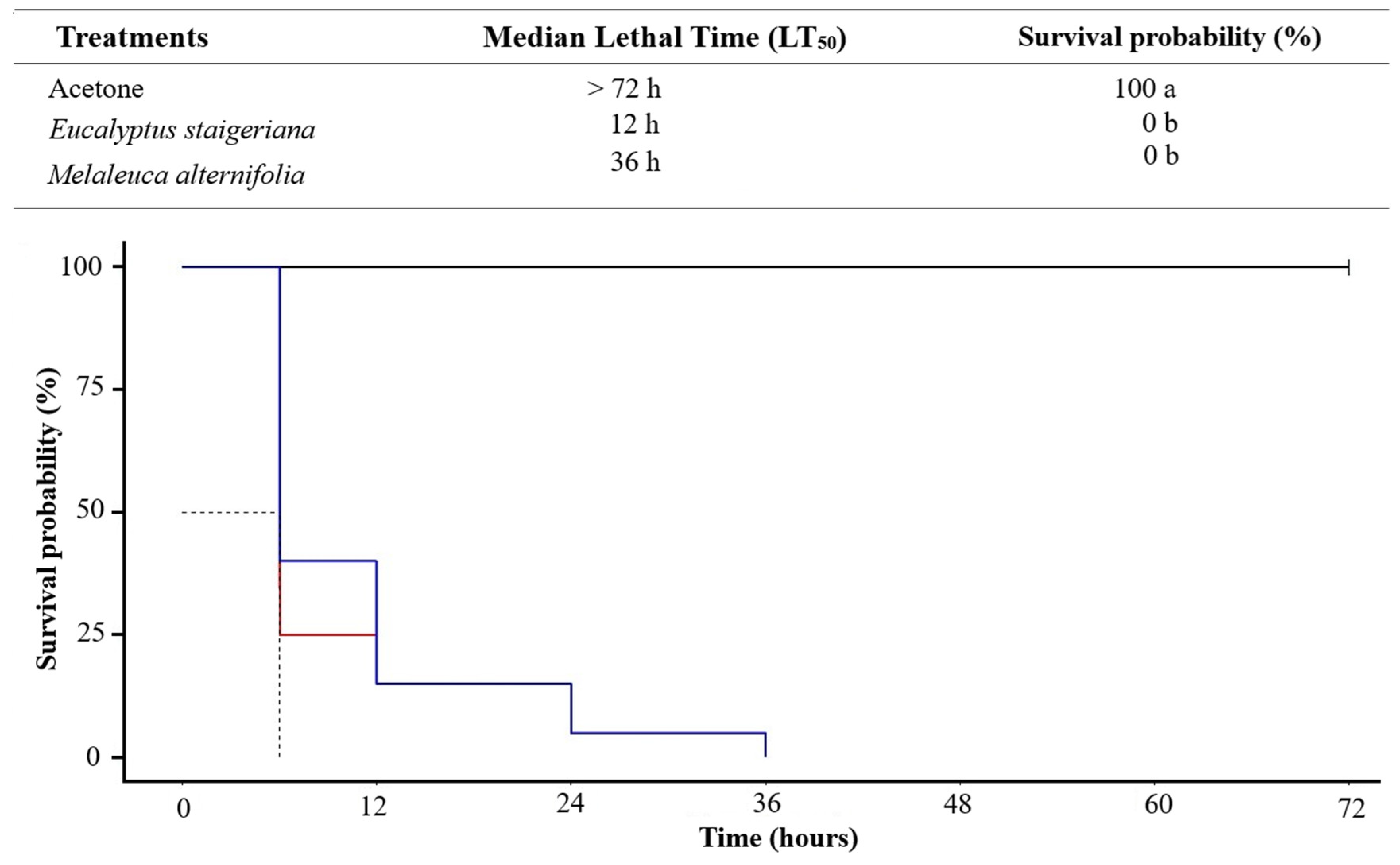

3.2. Acute Toxicity of EOs in a Topical Application Against P. absoluta

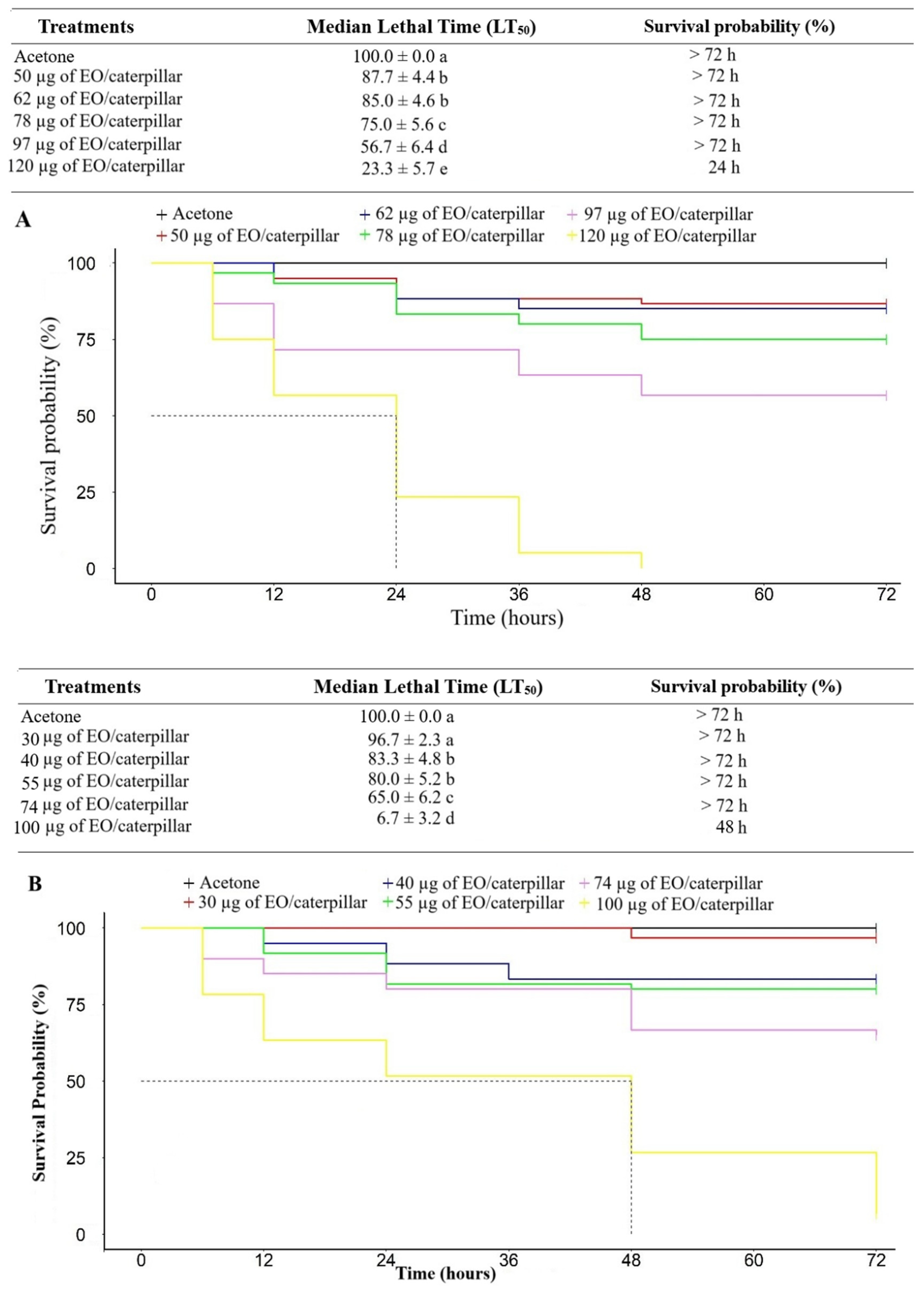

3.3. Determination of Dose‒Response and Time-Response Curves of EOs

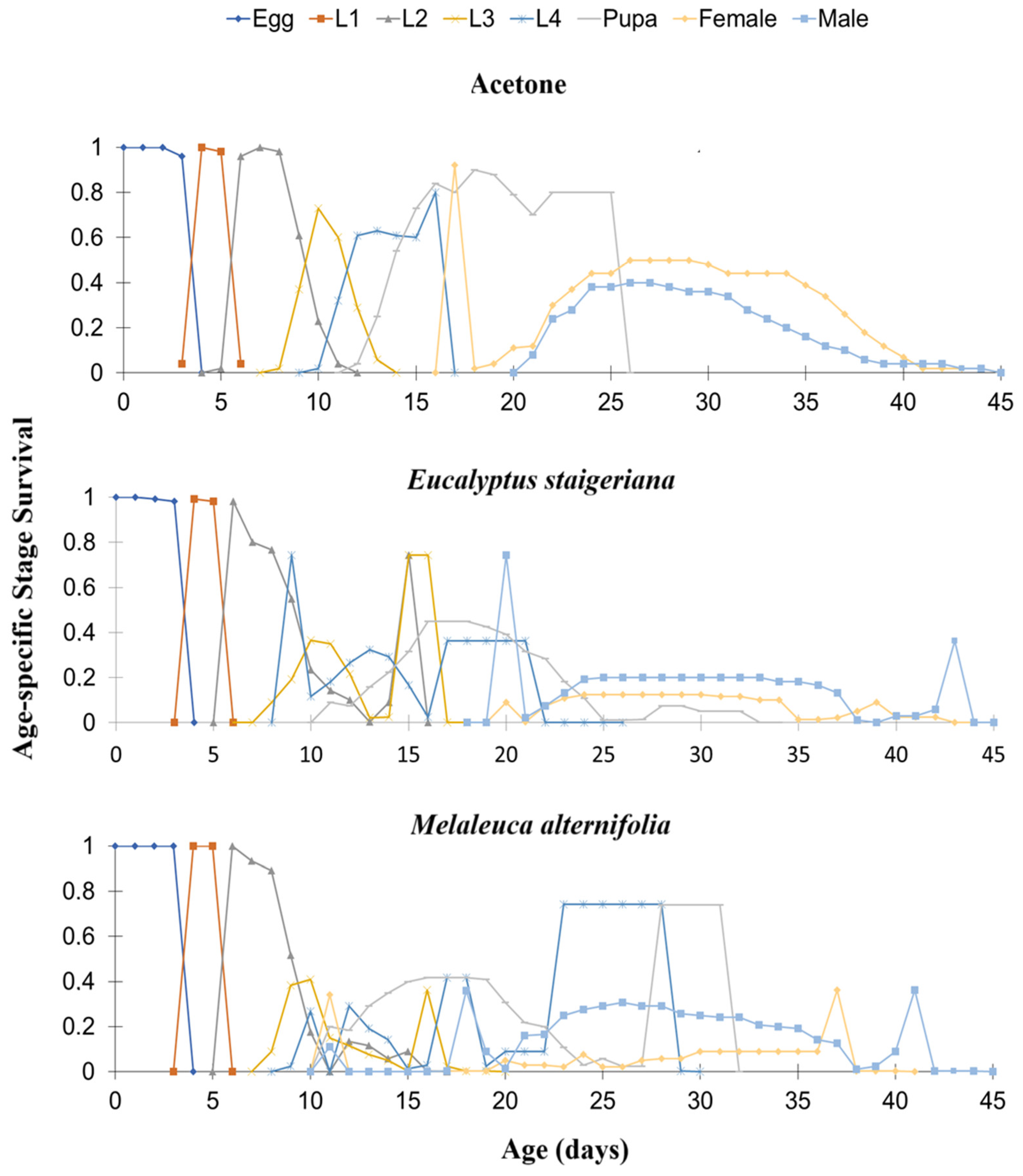

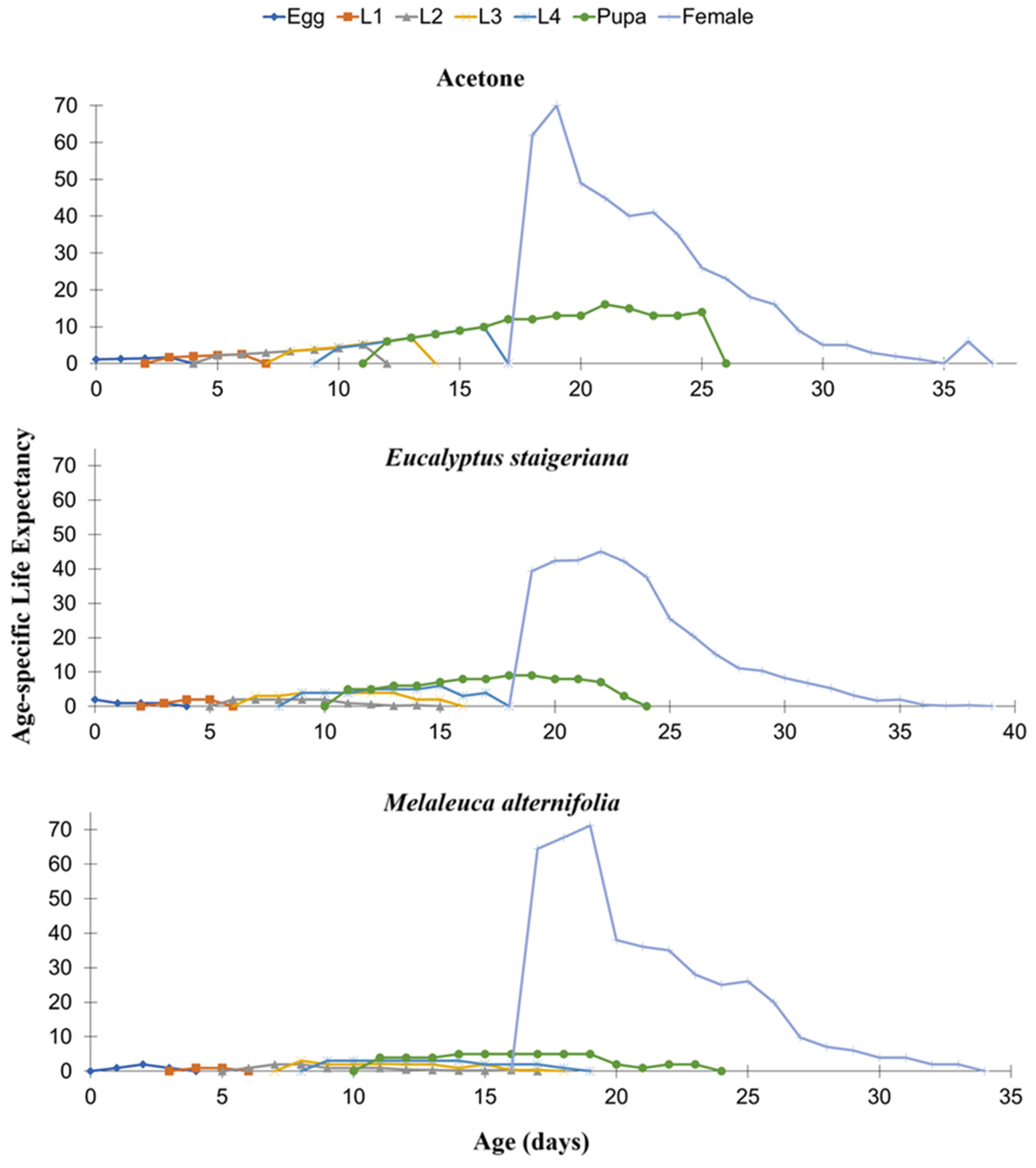

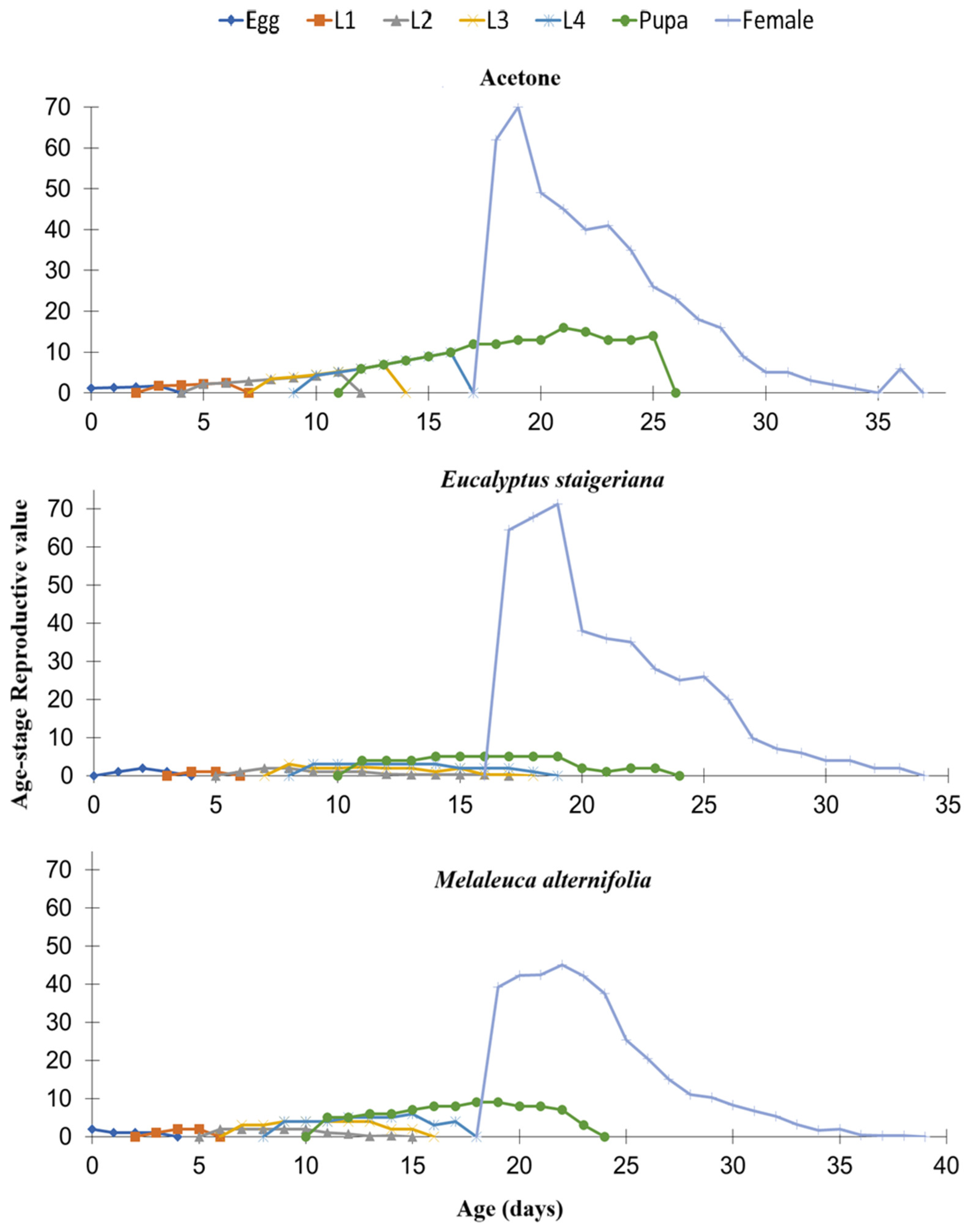

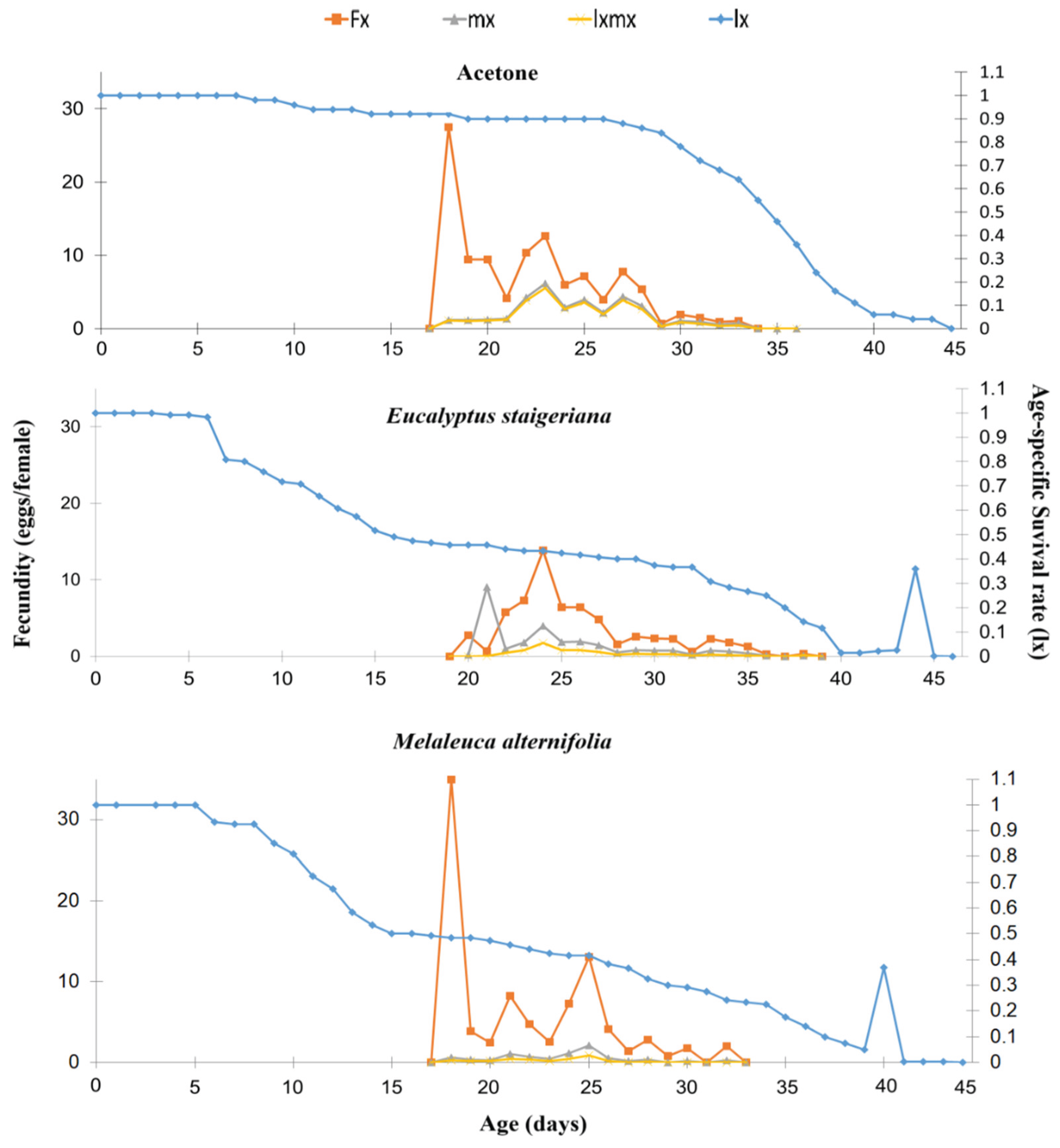

3.4. Effects of Sublethal Doses of EOs on the Life History Parameters of P. absoluta

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EOs | Essential Oils |

| EO | Essential Oil |

References

- EPPO. Tuta absoluta (GNORAB). Available online: https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/GNORAB/distribution (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Simoglou, K.Β.; Stavrakaki, M.; Alipranti, K.; Mylona, K.; Roditakis, E. Understanding Greenhouse Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Growers’ Perceptions for Optimal Phthorimaea absoluta (Meyrick) Management—A Survey in Greece. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Jeong, D.; Lee, G.-S.; Paik, C. First report of Phthorimaea absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae) in Korea. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2024, 15, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R.N.C.; Picanço, M.C. The tomato borer Tuta absoluta in South Aamerica: Pest status, management and insecticide resistance. EPPO Bull 2011–2016. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, A.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Wan, F.H.; Desneux, N. Ecology, worldwide spread, and management of the invasive South American tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta: Past, present, and future. Annu. Rev. Entomol 2018, 63, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biratu, W. Review on the effect of climate change on tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) production in Africa and mitigation strategies. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2018, 8, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mahlangu, L.; Sibisi, P.; Nofemela, R.S.; Ngmenzuma, T.; Ntushelo, K. The differential effects of Tuta absoluta infestations on the physiological processes and growth of tomato, potato, and eggplant. Insects 2022, 13, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddi, K.; Berger, M.; Bielza, P.; Rapisarda, C.; Williamson, M.S.; Moores, G.; et al. Mutation in the ace-1 gene of the tomato leaf miner (Tuta absoluta) associated with organophosphates resistance. J. Appl. Entomol 2017, 141, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddi, K.; Berger, M.; Bielza, P.; Cifuentes, D.; Field, L.M.; Gorman, K.; et al. Identification of mutations associated with pyrethroid resistance in the voltage-gated sodium channel of the tomato leaf miner (Tuta absoluta). Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol 2012, 42, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, R.N.C.; Roditakis, E.; Campos, M.R.; Haddi, K.; Bielza, P.; Siqueira, H.A.A.; et al. Insecticide resistance in the tomato pinworm Tuta absoluta: Patterns, spread, mechanisms, management and outlook. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 92, 1329–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.A.; Picanço, M.C.; Bacci, L.; Crespo, A.L.B.; Rosado, J.F.; Guedes, R.N.C. Control failure likelihood and spatial dependence of insecticide resistance in the tomato pinworm, Tuta absoluta. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, A.; Zappalà, L.; Stark, J.D.; Desneux, N. Do biopesticides affect the demographic traits of a parasitoid wasp and its biocontrol services through sublethal effects? PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 76548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roditakis, E.; Skarmoutsou, C.; Staurakaki, M. Toxicity of insecticides to populations of tomato borer Tuta absoluta (Meyrick) from Greece. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 69, 834–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sola, P.; Mvumi, B.M.; Ogendo, J.O.; Mponda, O.; Kamanula, J.F.; Nyirenda, S.P.; et al. Botanical pesticide production, trade and regulatory mechanisms in Sub-Saharan Africa: Making a case for plant-based pesticidal products. Food Secur. 2014, 6, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.A.; Campos, M.R.; Passos, L.C.; Carvalho, G.A.; Haro, M.M.; Lavoir, A.V.; et al. Botanical insecticide and natural enemies: A potential combination for pest management against Tuta absoluta. J. Pest Sci. 2019, 92, 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, A.M.; Arismendi, N.; López, M.D.; Vargas, M.; Schoebitz, M.; Palacio, D.A.; et al. Stability of the oil-based nanoemulsion of Laureliopsis philippiana (Looser) and its insecticidal activity against tomato borer (Tuta absoluta Meyrick). Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B. Botanical insecticides in the twenty-first century-fulfilling their promise? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, J.H.; Isman, M.B. Metabolism of citral, the major constituent of lemongrass oil, in the cabbage looper, Trichoplusia ni, and effects of enzyme inhibitors on toxicity and metabolism. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 133, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, A.F.; do Prado, R.L.; Gonçalves, G.L.P.; Maimone, N.M.; Gissi, D.S. de Lira et al. Searching for bioactive compounds from solanaceae: Lethal and sublethal toxicity to Spodoptera frugiperda and untargeted metabolomics approaches. J. Pest Sci. 2022, 95, 1317–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.F.; Ribeiro, L.P.; Lira, S.P.; Carvalho, G.A.; Vendramim, J.D. Growth inhibitory activities and feeding deterrence of solanaceae-based derivatives on fall armyworm. Agriculture. 2023, 13, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossa, A.-T.H. Green pesticides: Essential oils as biopesticides in insect-pest management. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 354–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nollet, L.M.; Rathore, H.S. Green pesticides handbook: Essential oils for pest control; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Acheuk, F.; Basiouni, S.; Shehata, A.A.; Dick, K.; Hajri, H.; Lasram, S.; et al. Status and Prospects of Botanical Biopesticides in Europe and Mediterranean Countries. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibiano, C.S.; Alves, D.S.; Freire, B.C.; Bertolucci, S.K.V.; Carvalho, G.A. Toxicity of essential oils and pure compounds of lamiaceae species against Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) and their safety for the nontarget organism Trichogramma pretiosum (Hymenoptera: Trichogrammatidae). Crop Prot. 2022, 158, 106011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, A.K.; Singh, V.K.; Kedia, A.; Das, S.; Dubey, N.K. Essential oils and their bioactive compounds as eco-friendly novel green pesticides for management of storage insect pests: Prospects and retrospects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 15, 18918–18940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tak, J.-H.; Isman, M.B. Enhanced cuticular penetration as the mechanism for synergy of insecticidal constituents of rosemary essential oil in Trichoplusia ni. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 12690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngongang, M.D.T.; Eke, P.; Sameza, M.L.; Ngo, M.N.L.; Lordon, C.D.; et al. Chemical constituents of essential oils from Thymus vulgaris and Cymbopogon citratus and their insecticidal potential against the tomato borer, Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2022, 42, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essoung, F.R.E.; Tadjong, A.T.; Chhabra, S.C.; Mohamed, S.A.; Hassanali, A. Repellence and fumigant toxicity of essential oils of Ocimum gratissimum and Ocimum kilimandscharicum on Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 37963–37976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarou, B.B.; Bawin, T.; Boullis, A.; Heukin, S.; Lognay, G.; Verheggen, F.J.; et al. Oviposition deterrent activity of basil plants and their essentials oils against Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 29880–29888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherif, A.; Mansour, R.; Ncibi, S.; WHached, W.; Grissa-Lebdi, K. Chemical composition and fumigant toxicity of five essential oils toward Tuta absoluta and its mirid predator Macrolophus pygmaeus. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2025, 132, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Pinto, M.; Vella, L.; Agrò, A. Oviposition deterrence and repellent activities of selected essential oils against Tuta absoluta Meyrick (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae): Laboratory and greenhouse investigations. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2022, 42, 3455–3464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouri-Ganbalani, G.; Ebadollahi, A.; Nouri, A. Chemical composition of the essential oil of Eucalyptus procera Dehnh. and its insecticidal effects against two stored product insects. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants. 2016, 19, 1234–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebadollahi, A. Essential Oils Isolated from Myrtaceae Family as Natural Insecticides. Annu. Res. Rev. Biol. 2013, 3, 148–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrotti, C.; Trentin, T.R.; Cavião, H.C.; Vilasboa, J.; Scariot, F.J.; Echeverrigaray, S.; et al. Eucalyptus staigeriana essential oil in the control of postharvest fungal rots and on the sensory analysis of grapes. Pesqui. Agropecuária Bras. 2022, 57, 02782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, J.P.; Baptistussi, R.C.; Funichello, M.; Oliveira, J.E.M.; de Bortoli, S.A. Efeito de óleos essenciais de Eucalyptus spp. sobre Zabrotes subfasciatus (Boh., 1833) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) e Callosobruchus maculatus (Fabr., 1775) (Coleoptera: Bruchidae) em duas espécies de feijões. Boletín Sanid. Veg. 2006, 32, 573–580. [Google Scholar]

- Gusmão, N.M.S.; de Oliveira, J.V.; Navarro, D.M.A.F.; Dutra, K.A.; da Silva, W.A.; Wanderley, M.J.A. Contact and fumigant toxicity and repellency of Eucalyptus citriodora Hook., Eucalyptus staigeriana F., Cymbopogon winterianus Jowitt and Foeniculum vulgare Mill. essential oils in the management of Callosobruchus maculatus. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2013, 54, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.M.N.; Oliveira, J.V.; França, S.M.; Navarro, D.M.A.F.; Barbosa, D.R.S.; Dutra, K.A. Toxicity and repellency of essential oils in the management of Sitophilus zeamais. Rev. Bras. Eng. Agrícola e Ambient. 2019, 23, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, M.V.; Morais, S.M.; Bevilaqua, C.M.L.; Silva, R.A.; Barros, R.S.; Sousa, R.N.; et al. Chemical composition of Eucalyptus spp. essential oils and their insecticidal effects on Lutzomyia longipalpis. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 167, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, G.S.; Wanderley-Teixeira, V.; Oliveira, J.V.; D’Assunção, C.G.; Cunha, F.M.; Teixeira, Á.A.C.; et al. Effect of trans-anethole, limonene and your combination in nutritional components and their reflection on reproductive parameters and testicular apoptosis in Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017, 263, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Chen, S.; Lin, G.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, X.; et al. The chromosome-level Melaleuca alternifolia genome provides insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying terpenoids biosynthesis. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 189, 115819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Xiao, J.-J.; Zhou, L.-J.; Yao, X.; Tang, F.; Hua, R.-M.; et al. Chemical composition, insecticidal and biochemical effects of Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil on the Helicoverpa armigera. J. Appl. Entomol. 2017, 141, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, S.M.; Hassan, N.A.; Wahba, T.F.; Shaker, N. Chemical composition and bioactivities of Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil and its main constituents against Spodoptera littoralis (Boisaduval, 1833). Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2022, 46, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, T.; Chohan, T.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Q.; Min, L.; Cao, H. Repellency, toxicity, gene expression profiling and in silico studies to explore insecticidal potential of Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil against Myzus persicae. Toxins (Basel). 2018, 10, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.A.C.; Ferreira, L.S.; Garcia, I.P.; Santos, H.L.; Ferreira, G.S.; Rocha, J.P.M.; et al. Eugenia uniflora, Melaleuca armillaris, and Schinus molle essential oils to manage larvae of the filarial vector Culex quinquefasciatus (Diptera: Culicidae). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 34749–34758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, C.; Baty, F.; Streibig, J.C.; Gerhard, D. Dose-response analysis using R. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 0146021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therneau, T. A package for survival analysis in R. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- R CoreTeam R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2023.

- Chi, H.; Güncan, A.; Kavousi, A.; Gharakhani, G.; Atlihan, R.; Özgökçe, M.S.; et al. R. TWOSEX-MSChart: The key tool for life table research and education. Entomol. Gen. 2022, 42, 845–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos-Segura, C.; Fornoni, J.; Núñez-Farfán, J. Evolutionary changes in plant tolerance against herbivory through a resurrection experiment. J. Evol. Biol. 2014, 27, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callander, J.T.; James, P.J. Insecticidal and repellent effects of tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) oil against Lucilia cuprina. Vet. Parasitol. 2012, 184, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isman, M.B.; Miresmailli, S.; MacHial, C. Commercial opportunities for pesticides based on plant essential oils in agriculture, industry and consumer products. Phytochem. Rev. 2011, 10, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nóbrega, F.F.F.; Salvadori, M.G.S.S.; Masson, C.J.; Mello, C.F.; Nascimento, T.S.; Leal-Cardoso, J.H.; et al. Monoterpenoid terpinen-4-ol exhibits anticonvulsant activity in behavioural and electrophysiological studies. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, A.P.; Abraham, Z. Chemical composition of essential oils obtained from plant parts of Alpinia calcarata Rosc. (Lesser Galangal) germplasm from South India. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2015, 27, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldissera, M.D.; Grando, T.H.; Souza, C.F.; Gressler, L.T.; Stefani, L.M.; da Silva, A.S.; et al. In vitro and in vivo action of terpinen-4-ol, γ-terpinene, and α-terpinene against Trypanosoma evansi. Exp. Parasitol. 2016, 162, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhakad, A.K.; Pandey, V.V.; Beg, S.; Rawat, J.M.; Singh, A. Biological, medicinal and toxicological significance of Eucalyptus leaf essential oil: A Review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 833–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khammassi, M.; Polito, F.; Amri, I.; Khedhri, S.; Hamrouni, L.; Nazzaro, F.; et al. Chemical composition and phytotoxic, antibacterial and antibiofilm activity of the essential oils of Eucalyptus occidentalis, E. striaticalyx and E. stricklandii. Molecules 2022, 27, 5820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macedo, I.T.F.; Bevilaqua, C.M.L.; de Oliveira, L.M.B.; Camurça-Vasconcelos, A.L.F.; Vieira, L.S.; Oliveira, F.R.; et al. Anthelmintic effect of Eucalyptus staigeriana essential oil against goat gastrointestinal nematodes. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 173, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, W.L.C.; Macedo, I.T.F.; dos Santos, J.M.L.; de Oliveira, E.F.; Camurça-Vasconcelos, A.L.F.; de Paula, H.C.B.; et al. Activity of chitosan-encapsulated Eucalyptus staigeriana essential oil on Haemonchus contortus. Exp. Parasitol. 2013, 135, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhi-Bo, G.; Zhi-Qing, M.; Jun-Tao, F.; Xing, Z. Inhibition of Na+,K+-ATPase in housefly (Musca domestica L.) by terpinen- 4-ol and its ester derivatives. Agric. Sci. China. 2009, 8, 1492–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Du, L.; Liu, T.; Ma, R.; Liu, X.; Yuan, H.; Liu, S. Insecticidal activity of a component, (-)-4-terpineol, isolated from the essential oil of Artemisia lavandulaefolia DC. against Plutella xylostella (L.). Insects 2022, 13, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajashekar, Y.; Raghavendra, A.; Bakthavatsalam, N. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition by biofumigant (coumaran) from leaves of Lantana camara in stored grain and household insect pests. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, C.S.; Pott, A.; Elifio-Esposito, S.; Dalarmi, L.; Fialho, K.N.; Burci, L.M.; et al. Effect of donepezil, tacrine, galantamine and rivastigmine on acetylcholinesterase inhibition in Dugesia tigrina. Molecules. 2016, 21, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.O.; Abolaji, A.O.; Omale, S.; Longdet, I.Y.; Kutshik, R.J.; Oyetayo, B.O.; et al. Benzo[a]Pyrene and Benzo[a]Pyrene-7,8-Dihydrodiol-9,10-Epoxide induced locomotor and reproductive senescence and altered biochemical parameters of oxidative damage in canton-S Drosophila melanogaster. Toxicol. Reports 2021, 8, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.H.; He, Y.P.; Gao, X.W. Comparative studies on acetylcholinesterase characteristics between the aphids, Sitobion avenae and Rhopalosiphum padi. J. Insect Sci. 2013, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboh, G.; Ademosun, A.O.; Olumuyiwa, T.A.; Olasehinde, T.A.; Ademiluyi, A.O.; Adeyemo, A.C. Insecticidal activity of essential oil from orange peels (Citrus sinensis) against Tribolium confusum, Callosobruchus maculatus and Sitophilus oryzae and its inhibitory effects on acetylcholinesterase and Na+/K+-ATPase activities. Phytoparasitica 2017, 45, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Feng, M.; Ji, Y.; Wu, W.; Hu, Z. Effects of Celangulin IV and V from Celastrus angulatus Maxim on Na + /K + -ATPase Activities of the Oriental Armyworm (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). J. Insect Sci. 2016, 16, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, J.D.; Banks, J.E. Population-level effects of pesticides and other toxicants on arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2003, 48, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, H. Life-table analysis incorporating both sexes and variable development rates among individuals. Environ. Entomol. 1988, 17, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Compound | RI* | RIL | Area (≥0.1%±SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. staigeriana | M. alternifolia | ||||

| 1 | α-thujene | 910 | 924 | 0.279 ± 0.003 | 0.710 ± 0.002 |

| 2 | α-pinene | 913 | 932 | 2.981 ± 0.050 | 3.074 ± 0.013 |

| 3 | α-phelandrene | 937 | 1002 | Nd | 0.635 ± 0.002 |

| 4 | α-terpinene | 950 | 1014 | 0.179 ± 0.023 | 10.44 ± 0.091 |

| 5 | sylvestre | 957 | 1025 | Nd | 2.109 ± 0.005 |

| 6 | β-pinene | 974 | 974 | 1.454 ± 0.022 | 0.618 ± 0.002 |

| 7 | γ-terpinene | 975 | 1054 | Nd | 22.102 ± 0.129 |

| 8 | NI | 990 | - | 1.085 ± 0.003 | Nd |

| 9 | α-phellandrene | 1004 | 1002 | 2.257 ± 0.025 | Nd |

| 10 | o-cymene | 1022 | 1022 | 2.150 ± 0.001 | 3.378 ± 0.157 |

| 11 | limonene | 1027 | 1024 | 27.298 ± 0.330 | Nd |

| 12 | 1.8-cineol | 1030 | 1026 | 4.133 ± 0.055 | 2.241 ± 0.005 |

| 13 | (Z)-β-ocimene | 1035 | 1032 | 0.227 ± 0.001 | Nd |

| 14 | (E)-β-ocimene | 1045 | 1044 | 0.435 ± 0.002 | Nd |

| 15 | γ-terpinene | 1055 | 1054 | 1.882 ± 0.016 | Nd |

| 16 | terpinolene | 1087 | 1086 | 8.919 ± 0.076 | 3.353 ± 0.010 |

| 17 | linalool | 1100 | 1095 | 1.562 ± 0.009 | Nd |

| 18 | NI | 1170 | - | 0.847 ± 0.315 | Nd |

| 19 | terpinen-4-ol | 1176 | 1174 | 0.887 ± 0.316 | 42.235 ± 0.100 |

| 20 | α-terpineol | 1190 | 1186 | 1.089 ± 0.016 | 3.386 ± 0.139 |

| 21 | nerol | 1228 | 1227 | 2.063 ± 0.019 | Nd |

| 22 | neral | 1241 | 1235 | 9.905 ± 0.024 | Nd |

| 23 | geraniol | 1255 | 1249 | 6.386 ± 0.048 | Nd |

| 24 | geranial | 1272 | 1264 | 13.825 ± 0.079 | Nd |

| 25 | methyl geraniate | 1324 | 1322 | 3.787 ± 0.021 | Nd |

| 26 | neryl acetate | 1366 | 1359 | 1.166 ± 0.012 | Nd |

| 27 | geranyl acetate | 1385 | 1379 | 3.246 ± 0.046 | Nd |

| 28 | α-gurjunene | 1406 | 1409 | Nd | 0.293 ± 0.001 |

| 29 | E-caryophyllene | 1415 | 1417 | 0.146 ± 0.001 | 0.224 ± 0.001 |

| 30 | aromadendrene | 1435 | 1439 | Nd | 1.238 ± 0.005 |

| 31 | allo -aromadendrene | 1456 | 1458 | Nd | 0.364 ± 0.001 |

| 32 | trans-cadina-1(6),4-dieno | 1470 | 1475 | Nd | 0.169 ± 0.001 |

| 33 | viridiflorene | 1492 | 1496 | Nd | 1.277 ± 0.004 |

| 34 | δ-cadinene | 1521 | 1522 | Nd | 0.900 ± 0.004 |

| Total | 98.188 | 99.220 | |||

| Treatment | n | X2 | P | *b | *e | DL50 (μg.μL-1) (LS –LI) | DL90 (μg.μL-1) (LS –LI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. staigeriana | 60 | 186 | 0.56 | -4.259 | 78.514 | 78.5 (72.0 – 85.0) | 131.5 (111.2– 151.8) |

| M. alternifolia | 60 | 285.9 | 0.68 | -3.947 | 76.571 | 76.5 (70.3 – 82.8) | 133.6 (110.0– 157.3) |

| Parameter | Stage | Acetone | Melaleuca alternifolia | Eucalyptus staigeriana | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean ± SE | N | Mean ± SE | N | Mean ± SE | ||

| Development time (days) Longevity (days) |

Egg | 100 | 3.96 ± 0.02 a | 120 | 3.00±0.00a | 100 | 3.00±0.00a |

| L1 | 100 | 2.06 ± 0.03 a | 120 | 2.00±0.00a | 100 | 2.00±0.00a | |

| L2 | 96 | 3.83 ± 0.09 a | 92 | 6.86±0.71b | 51 | 7.39±0.38b | |

| L3 | 96 | 2.16 ± 0.04 a | 84 | 8.41±0.59b | 48 | 4.33±0.23c | |

| L4 | 92 | 2.36 ± 0.07 a | 55 | 3.74±0.27ab | 48 | 4.12±0.24b | |

| Pupa | 90 | 8.00 ± 0.12 b | 49 | 5.63±0.23a | 46 | 5.63±0.15a | |

| Egg - Pupa | 90 | 22.44 ± 0.18 a | 49 | 12.14±0.47a | 35 | 11.83±0.37ab | |

| Adult | 90 | 34.02 ± 0.79 a | 49 | 39.00±0.00a | 35 | 37.63±0.58b | |

| Life cycle (days)* |

Female | 50 | 37.36 ± 0.47 a | 9 | 32.22 ± 1.99 b | 16 | 37.73 ± 1.03 a |

| Male | 40 | 35.00 ± 0.66 b | 40 | 34.85 ± 0.82 b | 23 | 38.48 ± 0.93 a | |

| Egg - Adult | 90 | 36.31 ± 0.41 b | 49 | 34.37 ± 0.78 c | 39 | 38.2 ± 0.69 a | |

| Parameter | Acetone | Melaleuca alternifolia | Eucalyptus staigeriana | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean ± SE | N | Mean ± SE | N | Mean ± SE | |

| Total fecundity (O/F) | 50 | 62.76 ± 4.28 a | 9 | 46.78 ± 9.97 a | 15 | 56.13 ± 6.23 a |

| Fertility (O/F)* | 44 | 71.32 ± 3.08 a | 8 | 60.14 ± 6.03 a | 14 | 60.14 ± 5.12 a |

| Oviposition (days) | 44 | 4.57 ± 0.26 b | 8 | 4.00 ± 0.22 b | 14 | 5.50 ± 0.36 a |

| PPOA (days) | 44 | 1.73 ± 0.17 a | 8 | 2.29± 0.64 a | 14 | 1.71 ± 0.22 a |

| PPOT (days) | 44 | 24.02 ± 0.39 a | 8 | 22.86 ± 0.96 a | 14 | 23.29 ± 0.42 a |

| TFM (O/F) | - | 107 | - | 74 | - | 93 |

| DFM (O/F) | - | 70 | - | 50 | - | 39 |

| Demographic parameter | Acetone | M. alternifolia | E. staigeriana |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | Mean ± SE | |

| Intrinsic growth rate (r) | 0.13 ± 0.005 a | 0.05 ± 0.017 b | 0.07 ± 0.010 b |

| Finite growth rate (λ) | 1.14 ± 0.006 a | 1.05 ± 0.018 b | 1.08 ± 0.011 b |

| Net reproductive rate (R0) | 31.38 ± 3.800 a | 3.51 ± 1.324 b | 7.02 ± 1.847 b |

| Average generation time (T) | 25.81 ± 0.422a | 25.03 ± 1.011 a | 26.66 ± 0.425 a |

| Gross reproductive rate (GRR) | 35.80 ± 4.073 a | 8.40 ± 3.056 b | 17.42 ± 4.233 ab |

| Intrinsic growth rate (r) | 0.13 ± 0.005 a | 0.05 ± 0.017 b | 0.07 ± 0.010 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).