Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Crude Extract and Fractionation Samples

2.2. Cell Culture

2.3. Nitric Oxide Assay

2.4. Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)

| Gene | The Sequences of the Primers |

| iNOS | F-CCAAGCCCTCACCTACTTCC |

| R-CTCTGAGGGCTGACACAAGG | |

| COX-2 | F-CATCCCCTTCCTGCGAAGTT |

| R-CATGGGAGTTGGGCAGTCAT | |

| IL-6 | F-AGTCCTTCCTACCCCAATTTCC |

| R-TAACGCACTAGGTTTGCCGA | |

| TNF-α | F-ACCGTCAGCCGATTTGCTAT |

| R-TTGGGCAGATTGACCTCAGC | |

| IL-12p40 | F-AGACCCTGCCCATTGAACTG |

| R-CAGGAGTCAGGGTACTCCCA | |

| IL-23p19 | F-CAGCAGCTCTCTCGGAATCT |

| R-CAGACCTTGGCGGATCCTTT | |

| IL-13 | F-GTATGGAGTGTGGACCTGGC |

| R-ATTTTGGTATCGGGGAGGCTG | |

| TGF-β | F-CTGCTGACCCCCACTGATAC |

| R-GGGGCTGATCCCGTTGATTT | |

| CD40 | F-GCTATGGGGCTGCTTGTTGA |

| R-GGTGGCATTGGGTCTTCTCA | |

| CD86 | F-ATGGACCCCAGATGCACCA |

| R-TGTGCCCAAATAGTGCTCGT | |

| GAPDH | F-CTCATGACCACAGTCCATGC |

| R-CACATTGGGGGTAGGAACAC |

2.5. Western Blotting

2.6. Immunofluorescence

2.7. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

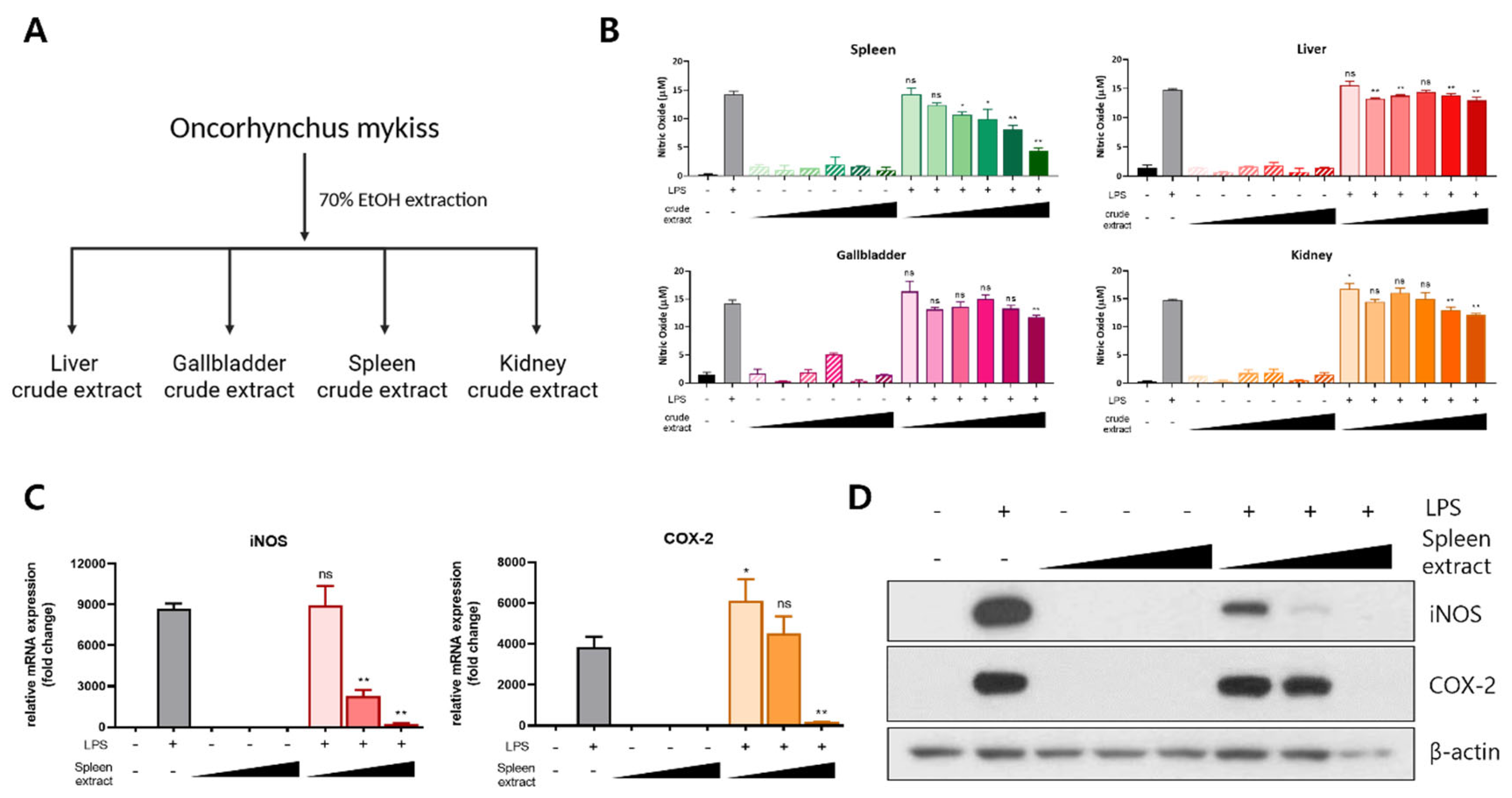

3.1. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Rainbow Trout Spleen Crude Extract in LPS-Stimulated RAW264.7 Cells

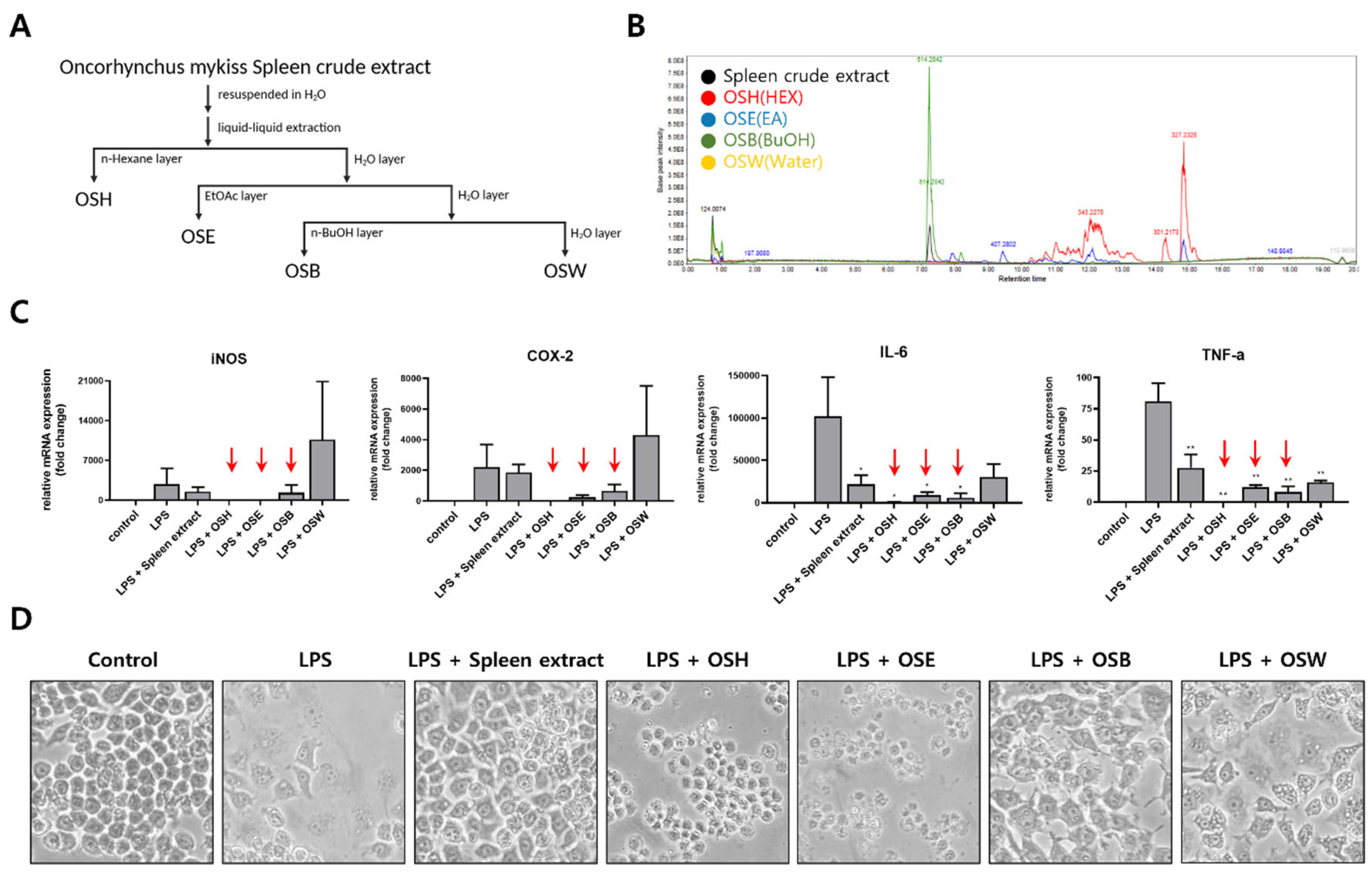

3.2. Fractionation of Rainbow Trout Spleen Crude Extract and Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Each Fraction

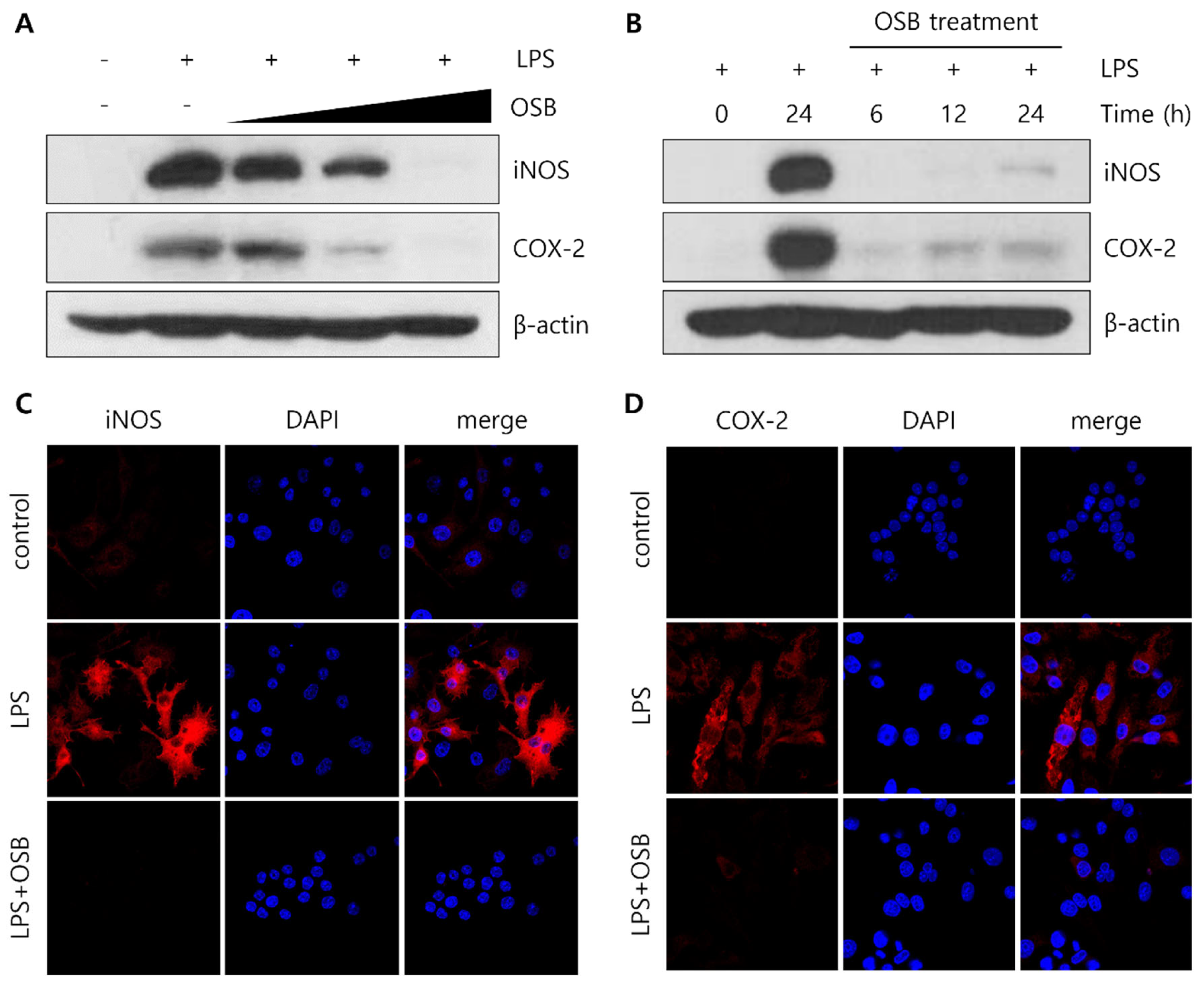

3.3. Regulatory Effect of OSB on iNOS and COX-2 Expression

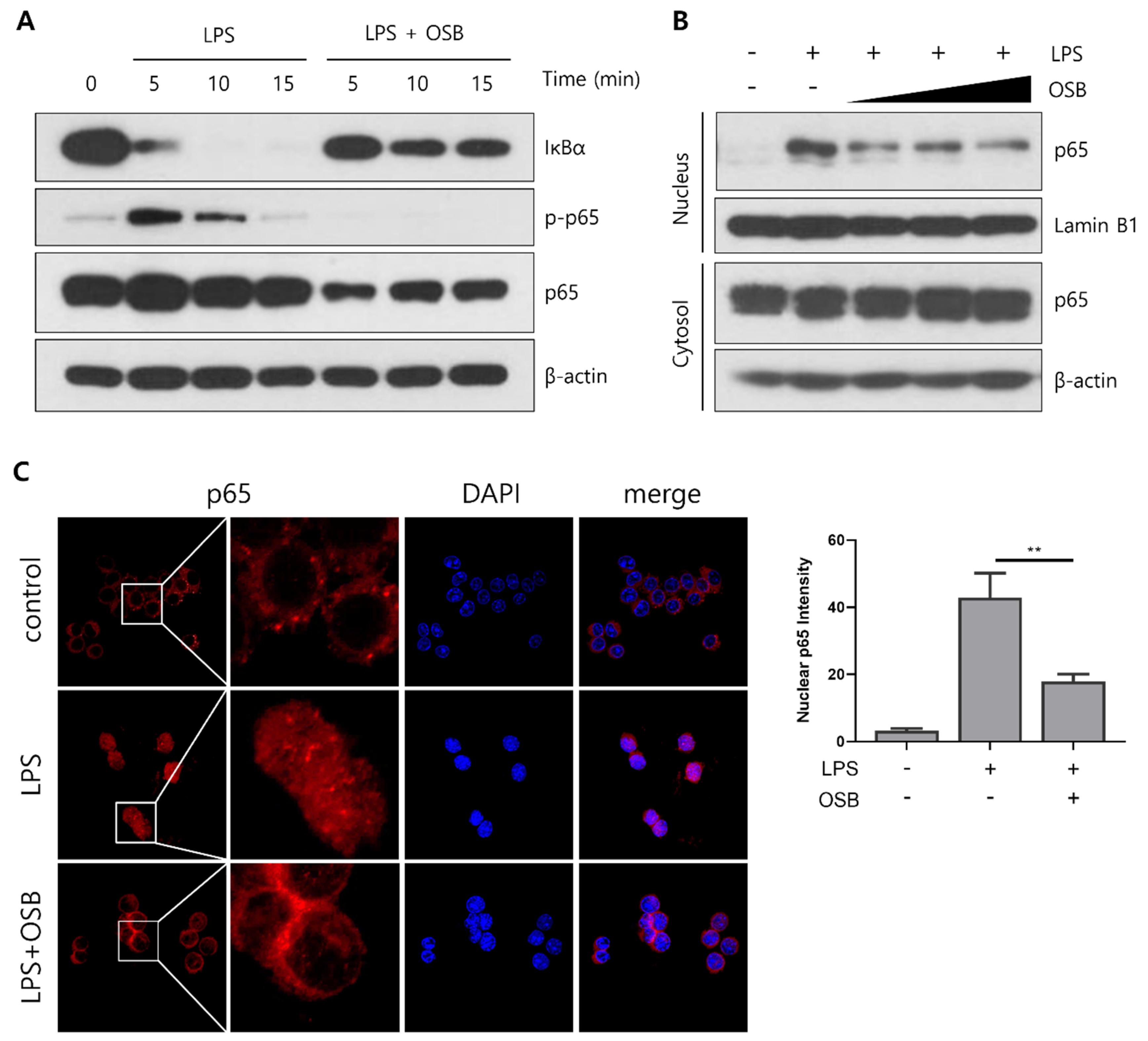

3.4. Regulatory Effect of OSB on the NF-κB Signaling Pathway

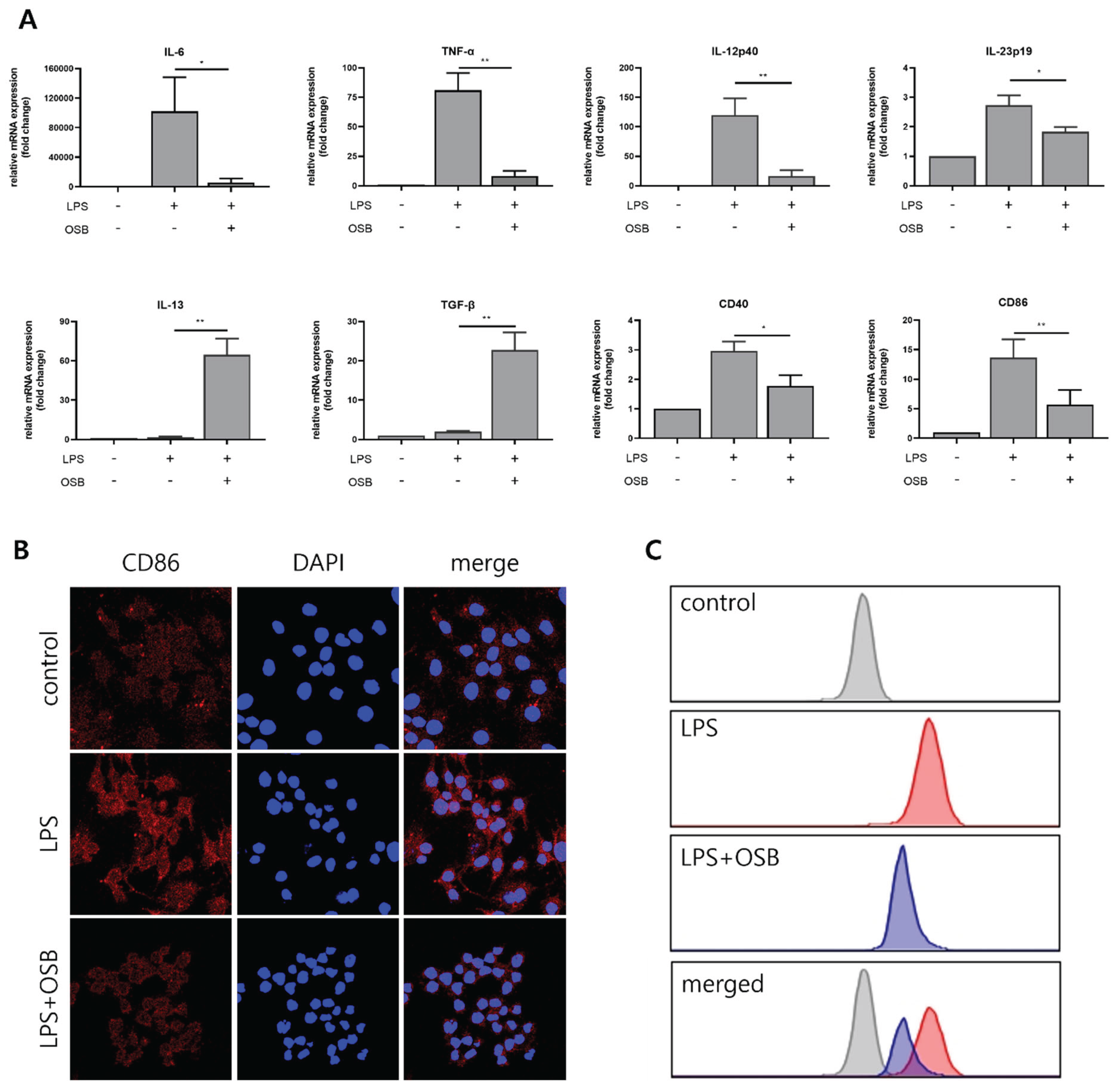

3.5. Regulatory Effect of OSB on M1 Macrophage Polarization

4. Discussion

References

- Wallach, D.; Kang, T.-B.; Kovalenko, A. Concepts of tissue injury and cell death in inflammation: a historical perspective. Nature Reviews Immunology 2014, 14, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuti, A.; Fazio, D.; Fava, M.; Piccoli, A.; Oddi, S.; Maccarrone, M. Bioactive lipids, inflammation and chronic diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2020, 159, 133–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opal, S.M.; DePalo, V.A. Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines. Chest 2000, 117, 1162–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, D.S. The multisystem adverse effects of NSAID therapy. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1999, 99, S1–s7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindu, S.; Mazumder, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and organ damage: A current perspective. Biochem Pharmacol 2020, 180, 114147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossol, M.; Heine, H.; Meusch, U.; Quandt, D.; Klein, C.; Sweet, M.J.; Hauschildt, S. LPS-induced cytokine production in human monocytes and macrophages. Crit Rev Immunol 2011, 31, 379–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wu, Y.H.; Zhu, Y.T.; Li, M.X.; Pei, H.H. Requirement of Rab21 in LPS-induced TLR4 signaling and pro-inflammatory responses in macrophages and monocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 508, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Huang, J.; Zhou, P.; Li, L.; Zheng, Q.; Fu, H. The role of TLR4/NF-kB signaling axis in pneumonia: from molecular mechanisms to regulation by phytochemicals. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.; Wang, D.; Yang, Z.; Wang, T. Pharmacological Effects of Polyphenol Phytochemicals on the Intestinal Inflammation via Targeting TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejban, P.; Nikravangolsefid, N.; Chamanara, M.; Dehpour, A.; Rashidian, A. The role of medicinal products in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) through inhibition of TLR4/NF-kappaB pathway. Phytother Res 2021, 35, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Neill, L.A. Primer: Toll-like receptor signaling pathways--what do rheumatologists need to know? Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2008, 4, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winand, L.; Sester, A.; Nett, M. Bioengineering of Anti-Inflammatory Natural Products. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-X.; Zhou, M.; Ma, H.-L.; Qiao, Y.-B.; Li, Q.-S. The Role of Chronic Inflammation in Various Diseases and Anti-inflammatory Therapies Containing Natural Products. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 1576–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, R.; Jachak, S.M. Recent developments in anti-inflammatory natural products. Med Res Rev 2009, 29, 767–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D.J.; Cragg, G.M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. J Nat Prod 2020, 83, 770–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Varatharajan, V.; Peng, H.; Senadheera, R. Utilization of marine by-products for the recovery of value-added products. Journal of Food Bioactives 2019, 6, 10–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, D.; Lauritano, C.; Palma Esposito, F.; Riccio, G.; Rizzo, C.; de Pascale, D. Fish Waste: From Problem to Valuable Resource. Marine Drugs 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketnawa, S.; Liceaga, A.M. Effect of microwave treatments on antioxidant activity and antigenicity of fish frame protein hydrolysates. Food and bioprocess technology 2017, 10, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, N.R.A.; Yusof, H.M.; Sarbon, N.M. Functional and bioactive properties of fish protein hydolysates and peptides: A comprehensive review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2016, 51, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Im, J.; Marasinghe, S.D.; Jo, E.; Bandara, M.S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, J.; Park, G.-H.; Oh, C. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Cutlassfish Head Peptone in RAW 264.7 Macrophages. Antioxidants 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardhana, H.H.A.C.K.; Liyanage, N.M.; Nagahawatta, D.P.; Lee, H.-G.; Jeon, Y.-J.; Kang, S.I. Pepsin Hydrolysate from Surimi Industry-Related Olive Flounder Head Byproducts Attenuates LPS-Induced Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in RAW 264.7 Macrophages and In Vivo Zebrafish Model. Marine Drugs 2024, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saisavoey, T.; Sangtanoo, P.; Reamtong, O.; Karnchanatat, A. Free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory potential of a protein hydrolysate derived from salmon bones on RAW 264.7 macrophage cells. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2019, 99, 5112–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmontesi, M. Polydeoxyribonucleotide for the improvement of a hypertrophic retracting scar—An interesting case report. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 2020, 19, 2982–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, I.-G.; Hwang, J.J.; Chang, B.S.; Kim, S.-H.; Jin, J.-J.; Hwang, L.; Kim, C.-J.; Choi, C.W. Polydeoxyribonucleotide ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via modulation of the MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathway in rats. International Immunopharmacology 2020, 83, 106444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano, M.; Bitto, A.; Altavilla, D.; Minutoli, L.; Polito, F.; Calò, M.; Lo Cascio, P.; Stagno d'Alcontres, F.; Squadrito, F. Polydeoxyribonucleotide stimulates angiogenesis and wound healing in the genetically diabetic mouse. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2008, 16, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizzardi, S.; Galli, C.; Govoni, P.; Boratto, R.; Cattarini, G.; Martini, D.; Belletti, S.; Scandroglio, R. Polydeoxyribonucleotide (PDRN) promotes human osteoblast proliferation: A new proposal for bone tissue repair. Life Sciences 2003, 73, 1973–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.; Yang, C.E.; Roh, T.S.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, W.J. Scar Prevention and Enhanced Wound Healing Induced by Polydeoxyribonucleotide in a Rat Incisional Wound-Healing Model. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, A.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.H.; Cho, S.-R.; Kim, H.J. Anti-inflammatory Effect of DNA Polymeric Molecules in a Cell Model of Osteoarthritis. Inflammation 2018, 41, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; Heo, S.Y.; Oh, G.W.; Heo, S.J.; Jung, W.K. Applications of Marine Organism-Derived Polydeoxyribonucleotide: Its Potential in Biomedical Engineering. Mar Drugs 2021, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Kim, M.-J.; Kweon, D.-K.; Lim, S.-T.; Lee, S.-J. Polydeoxyribonucleotide Activates Mitochondrial Biogenesis but Reduces MMP-1 Activity and Melanin Biosynthesis in Cultured Skin Cells. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology 2020, 191, 540–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Pintado, M.; Tavaria, F.K. A systematic review of natural products for skin applications: Targeting inflammation, wound healing, and photo-aging. Phytomedicine 2023, 115, 154824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Wan, X.; Wang, J. Fucoxanthin: A promising compound for human inflammation-related diseases. Life Sci 2020, 255, 117850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almutary, A.G.; Begum, M.Y.; Kyada, A.K.; Gupta, S.; Jyothi, S.R.; Chaudhary, K.; Sharma, S.; Sinha, A.; Abomughaid, M.M.; Imran, M.; et al. Inflammatory signaling pathways in Alzheimer's disease: Mechanistic insights and possible therapeutic interventions. Ageing Res Rev 2025, 104, 102548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, E.A.; Kang, N.; Kim, J.; Yang, H.W.; Ahn, G.; Heo, S.J. Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Turbo cornutus Viscera Ethanolic Extract against Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated Inflammatory Response via the Regulation of the JNK/NF-kB Signaling Pathway in Murine Macrophage RAW 264.7 Cells and a Zebrafish Model: A Preliminary Study. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Li, Q.; Shen, X.; Yao, Y.; Li, L.; Ma, H. Dehydroepiandrosterone attenuates LPS-induced inflammatory responses via activation of Nrf2 in RAW264.7 macrophages. Molecular Immunology 2021, 131, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.-J.; Ryu, B.; Sun Park, W.; Choi, I.L.W.; Jung, W.-K. Inhibitory Effects and Molecular Mechanism of an Anti-inflammatory Peptide Isolated from Intestine of Abalone, Haliotis Discus Hannai on LPS-Induced Cytokine Production via the p-p38/p-JNK Pathways in RAW264.7 Macrophages. Journal of Food and Nutrition Research 2025, 4, 690–698. [Google Scholar]

- Nikoo, M.; Benjakul, S.; Yasemi, M.; Ahmadi Gavlighi, H.; Xu, X. Hydrolysates from rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) processing by-product with different pretreatments: Antioxidant activity and their effect on lipid and protein oxidation of raw fish emulsion. LWT 2019, 108, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).