Submitted:

01 July 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Physicochemical Aspects of Single Nanochannel System

2.1. Single Nanochannel Fabrication: Materials and Methods

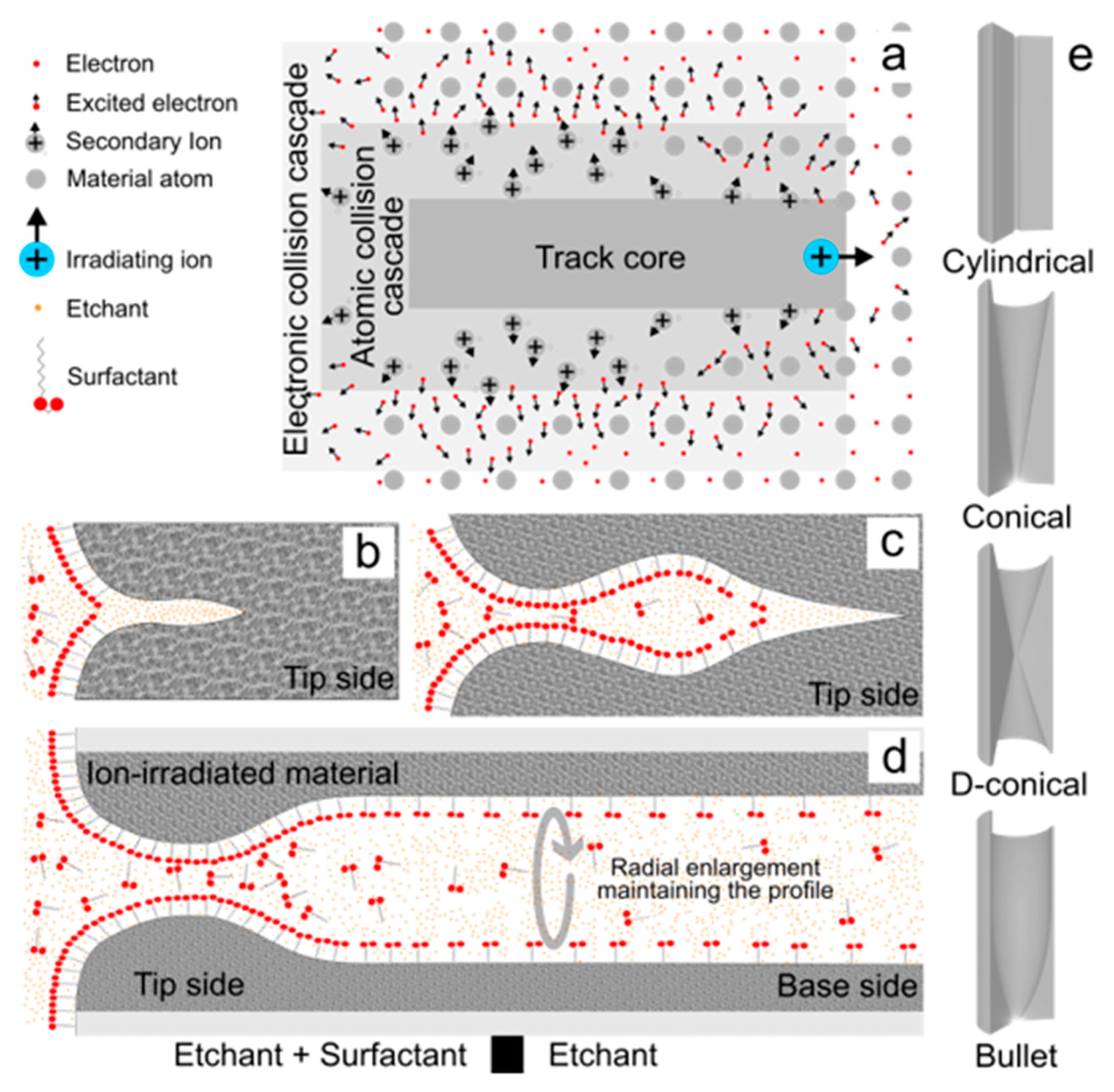

2.1.1. Ion-Track Chemical Etching

| Support | Fabrication specifications (tip side|base side) 1 | Shape | Etching time (minutes) | Etching T (°C) | Size(nm)2 (tip/base/length) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PET |

Ion track- asymmetrical chemical etching (6 M NaOH + 0.05% w/w Dowfax 2a1|6 M NaOH) 6 minutes, 60°C |

Bullet | 6 | 60 | (90/600/12000) | [103] |

| (76/560/12000) | [104] | |||||

| (55/500/12000) | [92] | |||||

| (60/600/12000) | [91] | |||||

| (No specified) | [90] | |||||

| (85/600/12000) | [89] | |||||

| (55/900/12000) | [88] | |||||

| Si3N4 | Photolithography- RIE -FIB Ga+ 30 kV 1pA | Cylindrical | 0.025 | Ion beam | (50/50/100000) | [105] |

| PI | Ion track- chemical etching (NaClO4 | NaClO4), etching stop with addition of 1M KI | Double conical | Electrochemically controlled etching stop time | 25 | (25/1300/12000) | [96] |

| PET | Ion track-UV sensitized asymmetrical etching (1 M KCl + 1 M HCOOH|9M NaOH) etching stop with addition of 1 M KCl + 1 M HCOOH | Conical | 30 | (30/860/12000) | [99] | |

| PET | Conical | 25 | (8/210/12000) | [106] | ||

| PET | Ion track-UV sensitized etching 35h (4 M NaOH + 0.02% v/v Dowfax 2a1|6M NaOH) etching stop with addition of 1 M HCl | Conical | 60 | (20/2500/12000) | [107] |

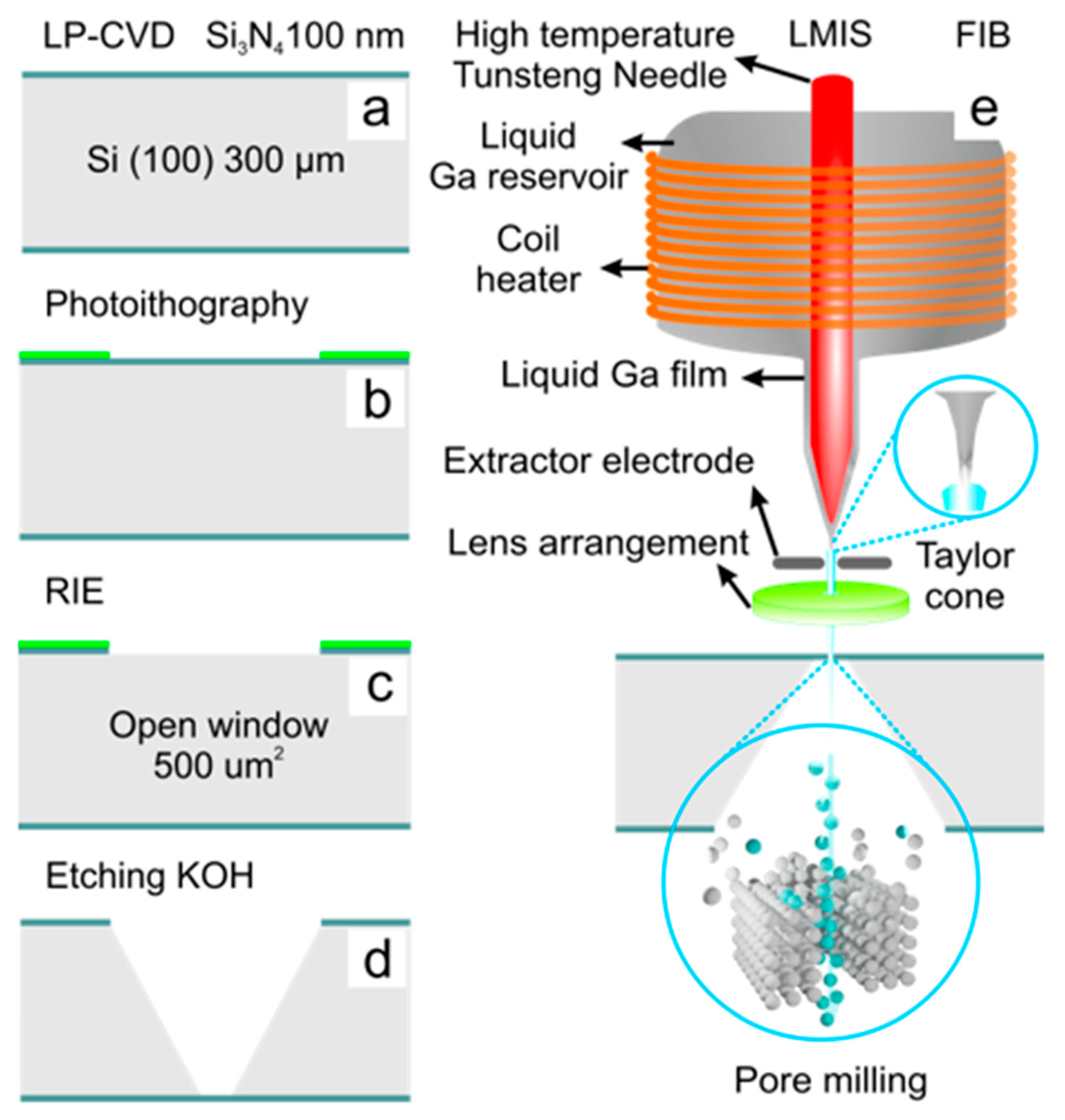

2.1.2. Photolithography-Reactive ion Etching-FIB

2.2. Single Nanochannel Physical and Chemical Properties

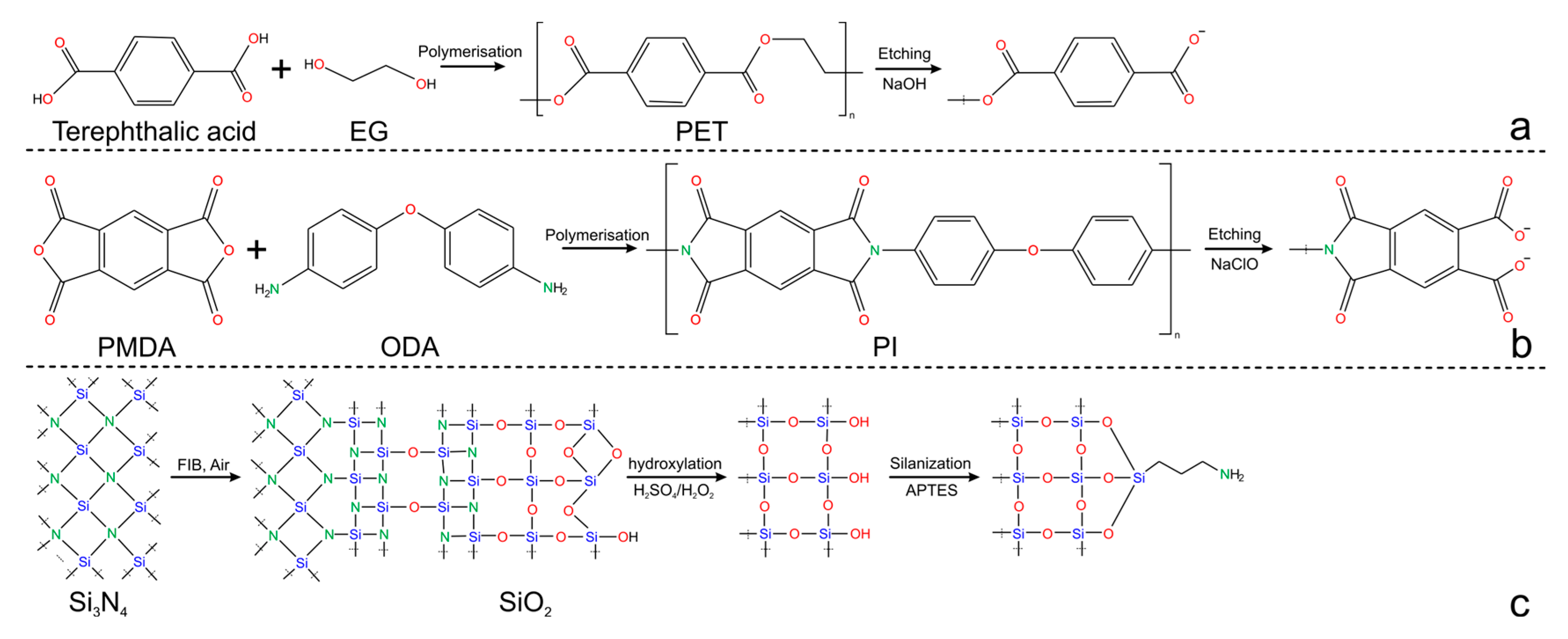

2.2.1. Morphology and Surface Chemistry

2.2.2. Wettability

2.3. Transport in Single Nanochannels

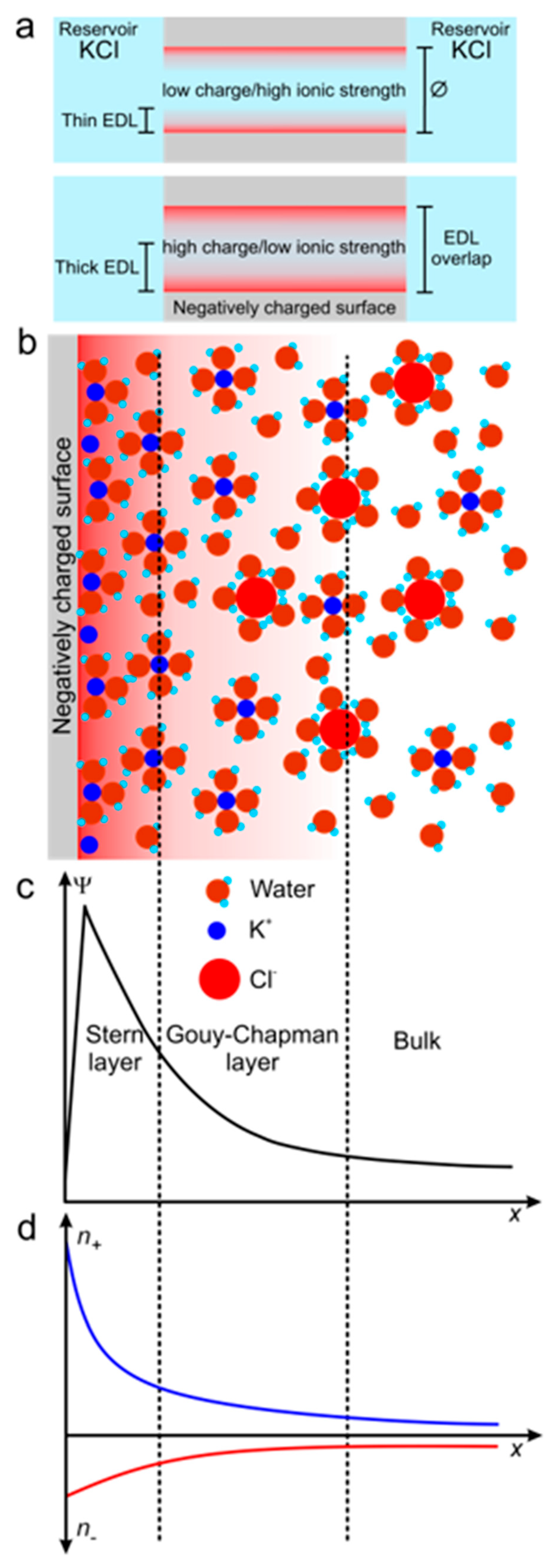

2.3.1. The Nanoconfinement Effects

2.3.2. Forces Regulating Ion Behavior

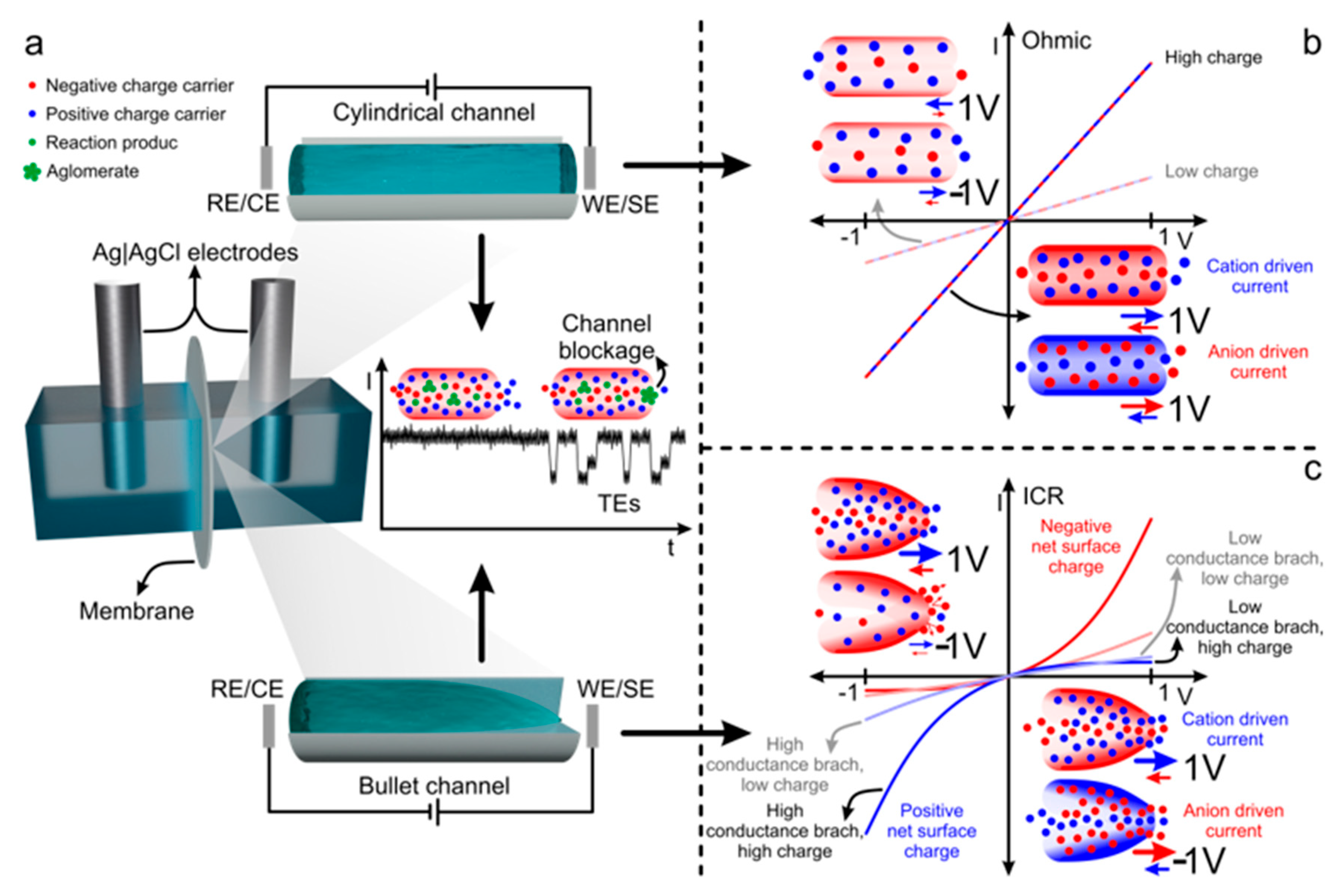

2.3.3. Signal Sources in Nanochannels: Iontronic Current, ICR and TEs

3. Sensing Platform Nanoarchitecture

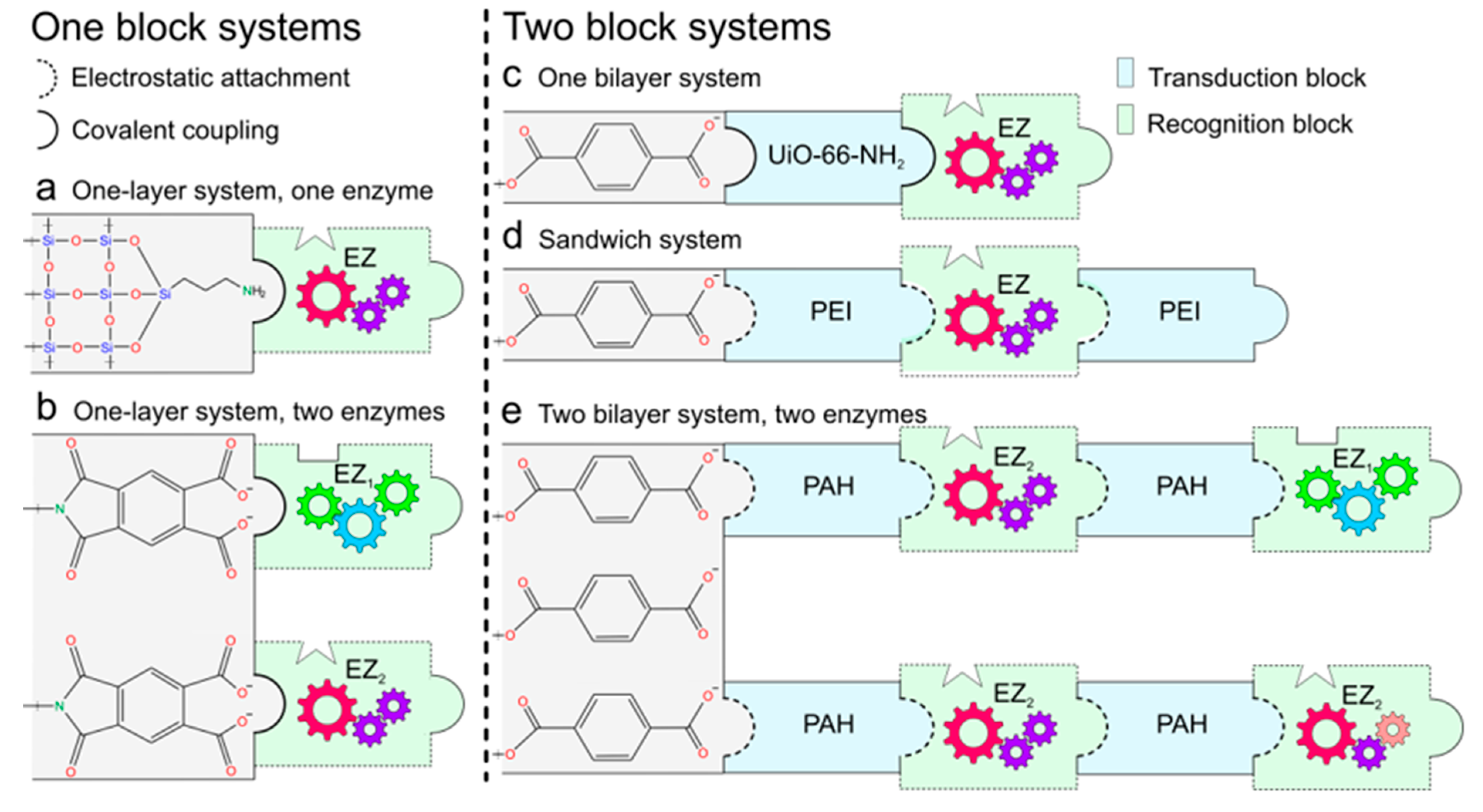

3.1. Functional Blocks Integration

3.1.1. One Block Systems

3.1.2. Two Blocks System

| Building blocks layers | Blocks Integration | Transduction mechanism | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| UiO-66-NH2-Urease | One-pot MOF synthesis, DVS-mediated crosslinking by Drop-coating | pH change effect over frec, single reaction | [103] |

| PAH/ADA/PAH | Layer by layer self-assembly by Dip-coating and Drop-coating | pH change effect over frec, single reaction | [104] |

| PAH/Urease/PAH/Urease: Arginase | Layer by layer self-assembly by Dip-coating | pH change effect over frec, cascade concerted functions | [92] |

| PEI/CD/PEI | Layer by layer self-assembly by Dip-coating and Drop-coating | pH change effect over frec, single reaction | [91] |

| PAH/Urease | Layer by layer self-assembly by Dip-coating | pH change effect over frec, steric obstruction | [90] |

| PEI/AchE | Layer by layer self-assembly by Dip-coating and Drop-coating | pH change effect over frec, single reaction | [89] |

| PAH/Urease | Layer by layer self-assembly by Dip-coating | pH change effect over frec, single reaction | [88] |

| HRP | EDC-NHS covalent coupling |

Translocation events (ABTS●+ aggregates) | [105] |

| GOx/HRP | pH change influence over transmembrane current-cascade concerted functions | [96] | |

| GOx | pH sensitive, single reaction | [99] | |

| HRP | Steric obstruction, specific interaction | [106] | |

| HRP | ABTS●+ sensitive, electrostatic interaction and steric obstruction | [107] |

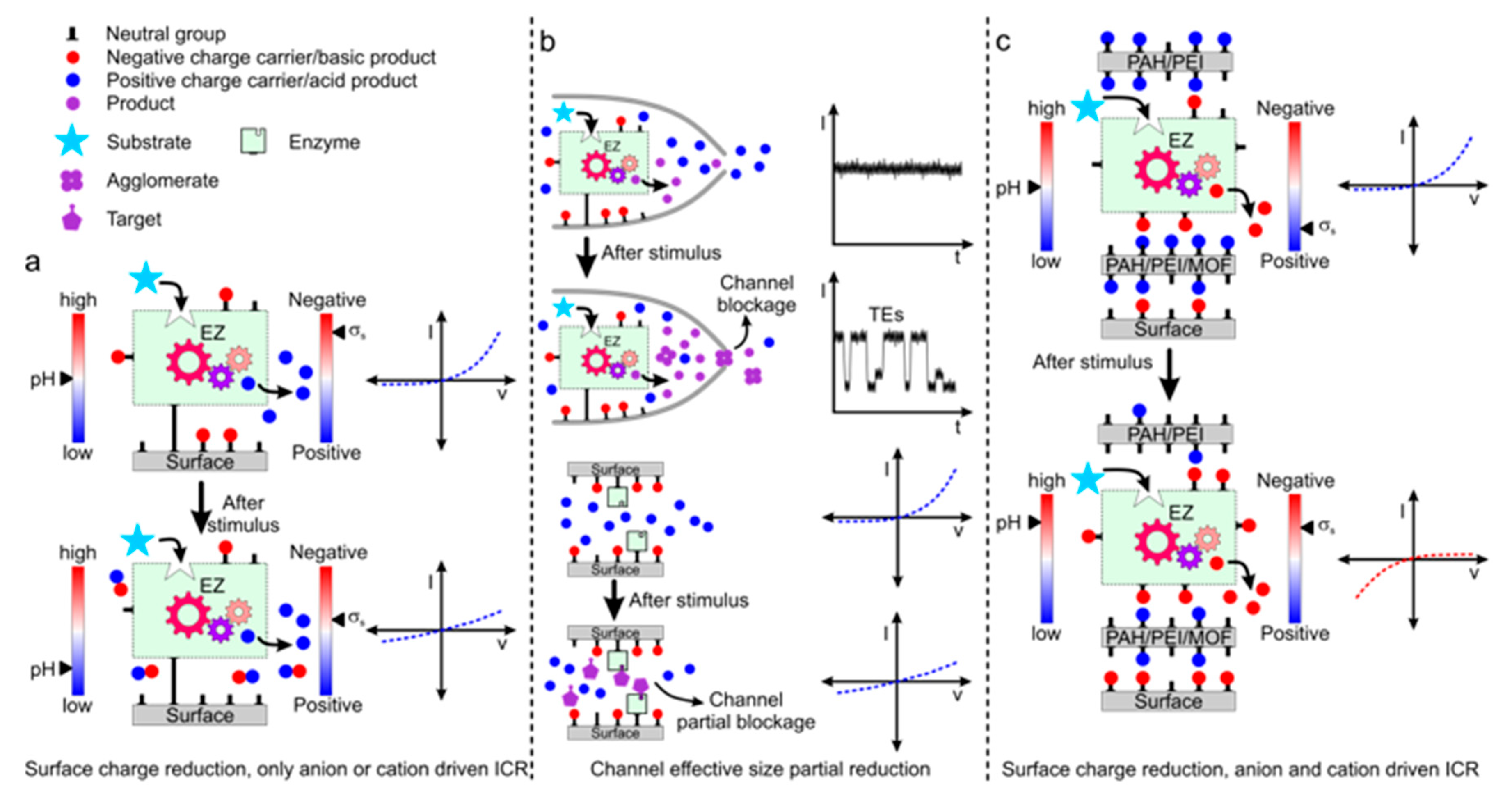

3.2. Recognition and Transduction Mechanism

4. Enzyme-Based SSNs Platforms

5. Challenges: Toward Future Developments

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations and Symbols

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PC | Polycarbonate |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| CR39 | Poly (allyl diglycol carbonate) |

| frec | Rectification factor |

| TEs | Translocation events |

| PNP | Poisson–Nernst–Planck |

| ICR | Ion current rectification |

| PI | Polyimide |

| PBD | Protein data bank |

| SSNs | Solid state nanochannels |

| EBL | Electron beam lithography |

| RIE | Reactive ion etching |

| FIB | Focused ion beam |

| IBS | Ion beam sculping |

| EE-PEO | Embedding electrospun polyethylene oxide |

| EB | Electron bean |

| LMIS | Liquid metal ion source |

| PFA | Perfluoroalkyl passivation |

| EDC | 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide |

| NHS | N-Hydroxy succinimide |

| MOF | Metal organic framework |

| DVS | Divinyl sulfone |

| PAH | Poly (allylamine Hydrochloride) |

| PEI | Polyethyleneimine |

| EZ | Enzyme |

| GOx | Glucose oxidase |

| ADA | Adenosine deaminase |

| CD | Creatinine deaminase |

| AchE | Acetyl cholinesterase |

| HRP | Horseradish peroxidase |

| PLL | Poly-L-Lysine |

| Con A | Concanavalin A |

| CV | Cyclic voltammetry |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| LP-CVD | Low pressure chemical vapor deposition |

| EDL | Electrical double layer |

| Surface charge density | |

| Faraday constant | |

| Gas constant | |

| Surface density | |

| Net charge | |

| Valence of ion | |

| Electron charge | |

| Electric potential | |

| Vacuum permittivity | |

| Relative permittivity | |

| Boltzmann constant | |

| Spatial coordinate | |

| Absolute temperature | |

| Bulk volume density | |

| Volume density | |

| Debye length | |

| Debye-Hückel parameter | |

| Ionic strength | |

| Conductance | |

| Mobility | |

| Fluid velocity | |

| Length | |

| Radial coordinate | |

| Current | |

| Potential | |

| Diffusion coefficient | |

| Flux per area | |

| Electric potential | |

| Concentration | |

| Density | |

| Viscosity | |

| Pressure |

References

- Atkinson, A.J.; Colburn, W.A.; DeGruttola, V.G.; DeMets, D.L.; Downing, G.J.; Hoth, D.F.; Oates, J.A.; Peck, C.C.; Schooley, R.T.; Spilker, B.A.; et al. Biomarkers and Surrogate Endpoints: Preferred Definitions and Conceptual Framework. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2001, 69, 89–95. [CrossRef]

- Demirci-Çekiç, S.; Özkan, G.; Avan, A.N.; Uzunboy, S.; Çapanoğlu, E.; Apak, R. Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2022, 209, 114477. [CrossRef]

- Hansson, O. Biomarkers for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nature Medicine 2021 27:6 2021, 27, 954–963. [CrossRef]

- Brucker, N.; do Nascimento, S.N.; Bernardini, L.; Charão, M.F.; Garcia, S.C. Biomarkers of Exposure, Effect, and Susceptibility in Occupational Exposure to Traffic-Related Air Pollution: A Review. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2020, 40, 722–736. [CrossRef]

- Alaimo, A.; Vaira, V.; Sarhadi, V.K.; Armengol, G. Molecular Biomarkers in Cancer. Biomolecules 2022, Vol. 12, Page 1021 2022, 12, 1021. [CrossRef]

- Karaboğa, M.N.S.; Sezgintürk, M.K. Biosensor Approaches on the Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Diseases: Sensing the Past to the Future. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2022, 209, 114479. [CrossRef]

- Xing, G.; Ai, J.; Wang, N.; Pu, Q. Recent Progress of Smartphone-Assisted Microfluidic Sensors for Point of Care Testing. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2022, 157, 116792. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; He, T.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Z.; Lee, C. Artificial Intelligence Enhanced Sensors - Enabling Technologies to next-Generation Healthcare and Biomedical Platform. Bioelectron Med 2023, 9, 17. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Seo, B.; Jeong, Y.; Park, I. A Review of Recent Advancements in Sensor-Integrated Medical Tools. Advanced Science 2024, 11, 2307427. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Cao, M.; Du, Y.; Liu, Q.; Emran, M.Y.; Kotb, A.; Sun, M.; Ma, C.-B.; Zhou, M. Artificial Enzyme Innovations in Electrochemical Devices: Advancing Wearable and Portable Sensing Technologies. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 44–60. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Rohilla, R.; Rana, S.; Rani, S.; Prabhakar, N. Recent Advances in Protein Biomarkers Based Enzymatic Biosensors for Non-Communicable Diseases. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2024, 174, 117683. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Ulstrup, J. Towards Continuous Potentiometric Enzymatic Biosensors. Curr Opin Electrochem 2024, 46, 101549. [CrossRef]

- Lino, C.; Barrias, S.; Chaves, R.; Adega, F.; Martins-Lopes, P.; Fernandes, J.R. Biosensors as Diagnostic Tools in Clinical Applications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2022, 1877, 188726. [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.; Aguilar, M.R.; Pattiya Arachchillage, K.G.G.; Chandra, S.; Rangan, S.; Ghosal Gupta, S.; Artes Vivancos, J.M. Biosensors for Public Health and Environmental Monitoring: The Case for Sustainable Biosensing. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2024, 12, 10296–10312. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chung, K.; Yu, S.; Lee, L.P. Nanoplasmonic Biosensors for Environmental Sustainability and Human Health. Chem Soc Rev 2024, 53, 10491–10522. [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, C.M.; Paradisi, F. Looking Back: A Short History of the Discovery of Enzymes and How They Became Powerful Chemical Tools. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 6082–6102. [CrossRef]

- Tamanoi, F. History of The Enzymes: 1950–2023. In The Enzymes; Academic Press, 2023; Vol. 54, pp. 3–11 ISBN 9780443136917.

- Colin J. Suckling Enzyme Chemistry; Suckling, C.J., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1990; ISBN 978-94-010-7317-2.

- Clark Jr, L.C.; Lyons, C. Annals. New York Academy of Sciences 1962, 102, 29–145. [CrossRef]

- Updike, S.J.; Hicks, G.P. The Enzyme Electrode. Nature 1967 214:5092 1967, 214, 986–988. [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, F.T.T.; de A. Falcão, I.R.; da S. Souza, J.E.; Rocha, T.G.; de Sousa, I.G.; Cavalcante, A.L.G.; de Oliveira, A.L.B.; de Sousa, M.C.M.; dos Santos, J.C.S. Designing of Nanomaterials-Based Enzymatic Biosensors: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Electrochem 2021, 2, 149–184. [CrossRef]

- Maghraby, Y.R.; El-Shabasy, R.M.; Ibrahim, A.H.; Azzazy, H.M.E.-S. Enzyme Immobilization Technologies and Industrial Applications. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 5184–5196. [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, R. Potassium Channels and the Atomic Basis of Selective Ion Conduction (Nobel Lecture). Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2004, 43, 4265–4277. [CrossRef]

- Agre, P. Aquaporin Water Channels. Biosci Rep 2004, 24, 127–163. [CrossRef]

- Scrimin, P.; Tecilla, P. Model Membranes: Developments in Functional Micelles and Vesicles. Curr Opin Chem Biol 1999, 3, 730–735. [CrossRef]

- Matile, S.; Som, A.; Sordé, N. Recent Synthetic Ion Channels and Pores. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 6405–6435. [CrossRef]

- Gokel, G.W.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Synthetic Models of Cation-Conducting Channels. Chem Soc Rev 2001, 30, 274–286. [CrossRef]

- Siwy, Z.; Apel, P.; Baur, D.; Dobrev, D.D.; Korchev, Y.E.; Neumann, R.; Spohr, R.; Trautmann, C.; Voss, K.O. Preparation of Synthetic Nanopores with Transport Properties Analogous to Biological Channels. Surf Sci 2003, 532–535, 1061–1066. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Janot, J.; Balme, S. Track-Etched Nanopore/Membrane: From Fundamental to Applications. Small Methods 2020, 4, 2000366. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, D.; Keçeci, K. Review—Track-Etched Nanoporous Polymer Membranes as Sensors: A Review. J Electrochem Soc 2020, 167, 037543. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Schmitz, F.; Isaksson, S.; Glas, J.; Arbab, O.; Andersson, M.; Sundell, K.; Eriksson, L.A.; Swaminathan, K.; Törnroth-Horsefield, S.; et al. High-Resolution Structure of a Fish Aquaporin Reveals a Novel Extracellular Fold. Life Sci Alliance 2022, 5, e202201491. [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, D.; Zoumpoulakis, A.; Veloso, R.F.; Peverini, L.; Shi, S.; Pozza, A.; Kugler, V.; Bonneté, F.; Bouceba, T.; Wagner, R.; et al. Biochemical, Biophysical, and Structural Investigations of Two Mutants ( <scp>C154Y</Scp> and <scp>R312H</Scp> ) of the Human Kir2.1 Channel Involved in the Andersen-Tawil Syndrome. The FASEB Journal 2024, 38, e70146. [CrossRef]

- Stoikov, I.I.; Antipin, I.S.; Konovalov, A.I. Artificial Ion Channels. Russian Chemical Reviews 2003, 72, 1055–1077. [CrossRef]

- Kan, X.; Wu, C.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L. Biomimetic Nanochannels: From Fabrication Principles to Theoretical Insights. Small Methods 2022, 6, 2101255. [CrossRef]

- Steinbacher, S.; Bass, R.; Strop, P.; Rees, D.C. Structures of the Prokaryotic Mechanosensitive Channels MscL and MscS. In Current Topics in Membranes; Academic Press, 2007; Vol. 58, pp. 1–24 ISBN 0121533581.

- Tanaka, Y.; Hirano, N.; Kaneko, J.; Kamio, Y.; Yao, M.; Tanaka, I. 2-Methyl-2,4-pentanediol Induces Spontaneous Assembly of Staphylococcal A-hemolysin into Heptameric Pore Structure. Protein Science 2011, 20, 448–456. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Caaveiro, J.M.M.; Morante, K.; González-Manãs, J.M.; Tsumoto, K. Structural Basis for Self-Assembly of a Cytolytic Pore Lined by Protein and Lipid. Nature Communications 2015 6:1 2015, 6, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Haque, F.; Guo, P. Engineering of Protein Nanopores for Sequencing, Chemical or Protein Sensing and Disease Diagnosis. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2018, 51, 80–89. [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; de Souza Santos, M.; Li, Y.; Tomchick, D.R.; Orth, K. High-Resolution Cryo-EM Structures of the E. Coli Hemolysin ClyA Oligomers. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0213423. [CrossRef]

- Grahame, D.A.S.; Bryksa, B.C.; Yada, R.Y. Factors Affecting Enzyme Activity. In Improving and Tailoring Enzymes for Food Quality and Functionality; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 11–55 ISBN 9781782422976.

- Feng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wu, D.; Su, Z.; Chen, G.; Liu, J.; Li, G. Recent Advances in Enzyme Immobilization Based on Novel Porous Framework Materials and Its Applications in Biosensing. Coord Chem Rev 2022, 459, 214414. [CrossRef]

- Bolivar, J.M.; Woodley, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Is Enzyme Immobilization a Mature Discipline? Some Critical Considerations to Capitalize on the Benefits of Immobilization. Chem Soc Rev 2022, 51, 6251–6290. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Luo, C.; Liu, W.; Lou, X.; Jiang, L.; Xia, F. Solid-State Nanochannels for Bio-Marker Analysis. Chem Soc Rev 2023, 52, 6270–6293. [CrossRef]

- Laucirica, G.; Toum Terrones, Y.; Cayón, V.; Cortez, M.L.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Trautmann, C.; Marmisollé, W.; Azzaroni, O. Biomimetic Solid-State Nanochannels for Chemical and Biological Sensing Applications. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2021, 144, 116425. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, C.; Wu, Y.; Kong, X.-Y.; Wen, L. Bioinspired Solid-State Nanochannels for Molecular Analysis. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 1225–1237. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Li, F.; Liu, J. Bioinspired Artificial Nanochannels: Construction and Application. Mater Chem Front 2021, 5, 1610–1631. [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Gao, P.; Ma, Q.; Wang, D.; Xia, F. Biomolecule-Functionalized Solid-State Ion Nanochannels/Nanopores: Features and Techniques. Small 2019, 15, 1804878. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Si, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, D.; Wu, X.; Gao, P.; Xia, F. Functional Solid-State Nanochannels for Biochemical Sensing. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2019, 115, 174–186. [CrossRef]

- Kuanaeva, R.M.; Vaneev, A.N.; Gorelkin, P. V.; Erofeev, A.S. Nanopipettes as a Potential Diagnostic Tool for Selective Nanopore Detection of Biomolecules. Biosensors (Basel) 2024, 14, 627. [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yu, R.-J.; Ying, Y.-L.; Long, Y.-T. Electrochemically Confined Effects on Single Enzyme Detection with Nanopipettes. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2022, 908, 116086. [CrossRef]

- Bulbul, G.; Chaves, G.; Olivier, J.; Ozel, R.E.; Pourmand, N. Nanopipettes as Monitoring Probes for the Single Living Cell: State of the Art and Future Directions in Molecular Biology. Cells 2018, 7, 55. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tang, H.; Qiu, X.; Li, Y. Solid-State Glass Nanopipettes: Functionalization and Applications. Chemistry – A European Journal 2024, 30, e202400281. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wu, M.; Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Qian, R. Nanopipettes for Chemical Analysis in Life Sciences. ChemBioChem 2025, 26, e202400879. [CrossRef]

- Stanley, J.; Pourmand, N. Nanopipettes—The Past and the Present. APL Mater 2020, 8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Reisner, W. Fabrication and Characterization of Nanopore-Interfaced Nanochannel Devices. Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 455301. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Stein, D.; McMullan, C.; Branton, D.; Aziz, M.J.; Golovchenko, J.A. Ion-Beam Sculpting at Nanometre Length Scales. Nature 2001, 412, 166–169. [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.J.; Aref, T.; Bezryadin, A. Fabrication of Symmetric Sub-5 Nm Nanopores Using Focused Ion and Electron Beams. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 3264–3267. [CrossRef]

- Fürjes, P. Controlled Focused Ion Beam Milling of Composite Solid State Nanopore Arrays for Molecule Sensing. Micromachines (Basel) 2019, 10, 774. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, Z.; Ma, J. A Simple Cost-Effective Method to Fabricate Single Nanochannels by Embedding Electrospun Polyethylene Oxide Nanofibers. ChemistryOpen 2024, 13, e202400008. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Galusha, J.; Shiozawa, P.G.; Wang, G.; Bergren, A.J.; Jones, R.M.; White, R.J.; Ervin, E.N.; Cauley, C.C.; White, H.S. Bench-Top Method for Fabricating Glass-Sealed Nanodisk Electrodes, Glass Nanopore Electrodes, and Glass Nanopore Membranes of Controlled Size. Anal Chem 2007, 79, 4778–4787. [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhou, L.; Lei, Z.; Hou, Y.; Hou, X. Current Progress in Glass-Based Nanochannels. Int J Smart Nano Mater 2024, 15, 222–237. [CrossRef]

- Sha, J.; Ni, Z.; Liu, L.; Yi, H.; Chen, Y. A Novel Method of Fabricating a Nanopore Based on a Glass Tube for Single-Molecule Detection. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 175304. [CrossRef]

- Kamai, H.; Xu, Y. Fabrication of Ultranarrow Nanochannels with Ultrasmall Nanocomponents in Glass Substrates. Micromachines (Basel) 2021, 12, 775. [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yu, S.; Harrell, C.C.; Martin, C.R. Conical Nanopore Membranes. Preparation and Transport Properties. Anal Chem 2004, 76, 2025–2030. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, P.; Shen, W.; Ding, S.; Wang, Y. Fabrication and Application of Nanoporous Polymer Ion-Track Membranes. Nanotechnology 2019, 30, 052001. [CrossRef]

- Apel, P.Y.; Blonskaya, I. V.; Dmitriev, S.N.; Orelovitch, O.L.; Presz, A.; Sartowska, B.A. Fabrication of Nanopores in Polymer Foils with Surfactant-Controlled Longitudinal Profiles. Nanotechnology 2007, 18, 305302. [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, T.W.; Apel, P.Yu.; Schiedt, B.; Trautmann, C.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Karim, S.; Neumann, R. Investigation of Nanopore Evolution in Ion Track-Etched Polycarbonate Membranes. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 2007, 265, 553–557. [CrossRef]

- Fink, D.; Hnatowicz, V. Transport Processes in Low-Energy Ion-Irradiated Polymers. In; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004; pp. 47–91 ISBN 978-3-662-10608-2.

- Wang, P.; Laskin, J. Ion Beams in Nanoscience and Technology; Hellborg, R., Whitlow, H.J., Zhang, Y., Eds.; Particle Acceleration and Detection; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; ISBN 978-3-642-00622-7.

- Apel, P. Track Etching Technique in Membrane Technology. Radiat Meas 2001, 34, 559–566. [CrossRef]

- Apel, P.Y.; Blonskaya, I. V.; Lizunov, N.E.; Olejniczak, K.; Orelovitch, O.L.; Sartowska, B.A.; Dmitriev, S.N. Asymmetrical Nanopores in Track Membranes: Fabrication, the Effect of Nanopore Shape and Electric Charge of Pore Walls, Promising Applications. Russian Journal of Electrochemistry 2017, 53, 58–69. [CrossRef]

- Apel, P.Y.; Blonskaya, I.V.; Didyk, A.Y.; Dmitriev, S.N.; Orelovitch, O.L.; Root, D.; Samoilova, L.I.; Vutsadakis, V.A. Surfactant-Enhanced Control of Track-Etch Pore Morphology. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 2001, 179, 55–62. [CrossRef]

- Trautmann, C.; Brüchle, W.; Spohr, R.; Vetter, J.; Angert, N. Pore Geometry of Etched Ion Tracks in Polyimide. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 1996, 111, 70–74. [CrossRef]

- Vlassiouk, I.; Apel, P.Y.; Dmitriev, S.N.; Healy, K.; Siwy, Z.S. Versatile Ultrathin Nanoporous Silicon Nitride Membranes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2009, 106, 21039–21044. [CrossRef]

- Toum Terrones, Y.; Laucirica, G.; Cayón, V.M.; Cortez, M.L.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Trautmann, C.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Ionic Nanoarchitectonics for Nanochannel-Based Biosensing Devices. In Materials Nanoarchitectonics; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 429–452 ISBN 9780323994729.

- Bodansky, D. Nuclear Energy; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2005; ISBN 978-0-387-20778-0.

- Basu, D.; Miroshnik, V.W. The Political Economy of Nuclear Energy; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-27028-5.

- Fleisher, R.L.; Price, P.B.; Walker, R.M. Nuclear Tracks in Solids: Principles and Applications. Berkeley 1975.

- Fleischer, R.L. Etching Nuclear Tracks. In Tracks to Innovation; Springer New York: New York, NY, 1998; pp. 1–25 ISBN 978-1-4612-4452-3.

- Saifulin, M.M.; O’Connell, J.H.; Janse van Vuuren, A.; Skuratov, V.A.; Kirilkin, N.S.; Zdorovets, M.V. Latent Tracks in Bulk Yttrium-Iron Garnet Crystals Irradiated with Low and High Velocity Krypton and Xenon Ions. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 2019, 460, 98–103. [CrossRef]

- Fink, D. Transport Processes in Ion-Irradiated Polymers; Springer Series in Materials Science; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004; Vol. 65; ISBN 978-3-642-05894-3.

- Young, D.A. Etching of Radiation Damage in Lithium Fluoride. Nature 1958 182:4632 1958, 182, 375–377. [CrossRef]

- Price, P.B.; Walker, R.M. Chemical Etching of Charged-Particle Tracks in Solids. J Appl Phys 1962, 33, 3407–3412. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dai, Y.; Sun, J.; Shen, J.; Lin, M.; Xia, F. Solid-State Nanopore/Nanochannel Sensors with Enhanced Selectivity through Pore-in Modification. Anal Chem 2024, 96, 2277–2285. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, X.-Y.; Gao, L.; Tian, Y.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L. Fabrication of Nanochannels. Materials 2015, 8, 6277–6308. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, L. Building Bio-Inspired Artificial Functional Nanochannels: From Symmetric to Asymmetric Modification. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2012, 51, 5296–5307. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L. Bioinspired Smart Asymmetric Nanochannel Membranes. Chem Soc Rev 2018, 47, 322–356. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Mitta, G.; Peinetti, A.S.; Cortez, M.L.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Trautmann, C.; Azzaroni, O. Highly Sensitive Biosensing with Solid-State Nanopores Displaying Enzymatically Reconfigurable Rectification Properties. Nano Lett 2018, 18, 3303–3310. [CrossRef]

- Toum Terrones, Y.; Laucirica, G.; Cayón, V.M.; Fenoy, G.E.; Cortez, M.L.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Trautmann, C.; Mamisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Highly Sensitive Acetylcholine Biosensing via Chemical Amplification of Enzymatic Processes in Nanochannels. Chemical Communications 2022, 58, 10166–10169. [CrossRef]

- Peinetti, A.S.; Cortez, M.L.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Azzaroni, O. Nanoprecipitation-Enhanced Sensitivity in Enzymatic Nanofluidic Biosensors. Anal Chem 2024, 96, 5282–5288. [CrossRef]

- Parra, L.M.H.; Laucirica, G.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Marmisollé, W.; Azzaroni, O. Sensing Creatinine in Urine via the Iontronic Response of Enzymatic Single Solid-State Nanochannels. Biosens Bioelectron 2025, 268, 116893. [CrossRef]

- Gramajo, M.E.; Otero Maffoni, L.; Hernández Parra, L.M.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Cortez, M.L.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Peinetti, A.S.; Azzaroni, O. Harnessing Concerted Functions in Confined Environments: Cascading Enzymatic Reactions in Nanofluidic Biosensors for Sensitive Detection of Arginine. Chemical Communications 2025, 61, 697–700. [CrossRef]

- Apel, P.Y.; Blonskaya, I. V.; Orelovitch, O.L.; Root, D.; Vutsadakis, V.; Dmitriev, S.N. Effect of Nanosized Surfactant Molecules on the Etching of Ion Tracks: New Degrees of Freedom in Design of Pore Shape. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 2003, 209, 329–334. [CrossRef]

- Apel, P.Yu.; Blonskaya, I.V.; Dmitriev, S.N.; Mamonova, T.I.; Orelovitch, O.L.; Sartowska, B.; Yamauchi, Y. Surfactant-Controlled Etching of Ion Track Nanopores and Its Practical Applications in Membrane Technology. Radiat Meas 2008, 43, S552–S559. [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.; Ensinger, W.; Mujahid, S.A.; Maaz, K.; Khan, E.U. Effect of Etching Conditions on Pore Shape in Etched Ion-Track Polycarbonate Membranes. Radiat Meas 2009, 44, 779–782. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yan, J.; Li, J. Small-Molecule Triggered Cascade Enzymatic Catalysis in Hour-Glass Shaped Nanochannel Reactor for Glucose Monitoring. Anal Chem 2014, 86, 10546–10551. [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, D.; Boda, D.; He, Y.; Apel, P.; Siwy, Z.S. Synthetic Nanopores as a Test Case for Ion Channel Theories: The Anomalous Mole Fraction Effect without Single Filing. Biophys J 2008, 95, 609–619. [CrossRef]

- Siwy, Z.S. Ion-Current Rectification in Nanopores and Nanotubes with Broken Symmetry. Adv Funct Mater 2006, 16, 735–746. [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Zhang, H.; Xie, G.; Xiao, K.; Wen, L.; Li, S.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, L. Ultratrace Detection of Glucose with Enzyme-Functionalized Single Nanochannels. J Mater Chem A Mater 2014, 2, 19131–19135. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Mitta, G.; Marmisolle, W.A.; Burr, L.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Trautmann, C.; Azzaroni, O. Proton-Gated Rectification Regimes in Nanofluidic Diodes Switched by Chemical Effectors. Small 2018, 14, 1703144. [CrossRef]

- Apel, P.Yu.; Blonskaya, I.V.; Orelovitch, O.L.; Dmitriev, S.N. Diode-like Ion-Track Asymmetric Nanopores: Some Alternative Methods of Fabrication. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B 2009, 267, 1023–1027. [CrossRef]

- Froehlich, K.; Scheuerlein, M.C.; Ali, M.; Nasir, S.; Ensinger, W. Enhancement of Heavy Ion Track-Etching in Polyimide Membranes with Organic Solvents. Nanotechnology 2022, 33, 045301. [CrossRef]

- Angel L. Huamani; Gregorio Laucirica; María Eugenia Toimil-Molares; Waldemar Marmisollé; Omar Azzaroni; Matías Rafti Expanding the Synergy between MOFs and Solid-State-Nanochannels: Post-Synthetic Modification for the Covalent Anchoring of Urease in Urea Detection (to be submitted).

- L. Miguel Hernandez Parra; Marcos E. Gramajo; Lautaro Otero Maffoni; Laucirica Gregorio; Ana S. Peinetti; M. Lorena Cortez; M. Eugenia Toimil-Molares; Waldemar, A.M.; Omar Azzaroni Single Nanochannel-Based Iontronic Detection of Adenosine at Nanomolar Concentrations. Chemistry - A European Journal 2025, Submitted.

- Zhu, L.; Gu, D.; Liu, Q. Hydrogen Peroxide Sensing Based on Inner Surfaces Modification of Solid-State Nanopore. Nanoscale Res Lett 2017, 12, 422. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Ramirez, P.; Tahir, M.N.; Mafe, S.; Siwy, Z.; Neumann, R.; Tremel, W.; Ensinger, W. Biomolecular Conjugation inside Synthetic Polymer Nanopores via Glycoprotein–Lectin Interactions. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 1894. [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Tahir, M.N.; Siwy, Z.; Neumann, R.; Tremel, W.; Ensinger, W. Hydrogen Peroxide Sensing with Horseradish Peroxidase-Modified Polymer Single Conical Nanochannels. Anal Chem 2011, 83, 1673–1680. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, K.; Fardoost, A.; Mhatre, N.; Rajan, J.; Boisvert, D.; Javanmard, M. A Thorough Review of Emerging Technologies in Micro- and Nanochannel Fabrication: Limitations, Applications, and Comparison. Micromachines (Basel) 2024, 15, 1274. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Chen, S.; Dai, H.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Peng, W.; Shan, W.; Duan, H. Recent Advances in Focused Ion Beam Nanofabrication for Nanostructures and Devices: Fundamentals and Applications. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 1529–1565. [CrossRef]

- Melngailis, J. Focused Ion Beam Technology and Applications. Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B: Microelectronics Processing and Phenomena 1987, 5, 469–495. [CrossRef]

- Kant, K.; Losic, D. FIB Nanostructures; Wang, Z.M., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Nanoscale Science and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2013; Vol. 20; ISBN 978-3-319-02873-6.

- Chen, X.; Zhang, L. Review in Manufacturing Methods of Nanochannels of Bio-Nanofluidic Chips. Sens Actuators B Chem 2018, 254, 648–659. [CrossRef]

- Tseng, A.A. Recent Developments in Nanofabrication Using Focused Ion Beams. Small 2005, 1, 924–939. [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, D.; Malyshev, G.; Ryzhkov, I.; Mozharov, A.; Shugurov, K.; Sharov, V.; Panov, M.; Tumkin, I.; Afonicheva, P.; Evstrapov, A.; et al. Focused Ion Beam Milling Based Formation of Nanochannels in Silicon-Glass Microfluidic Chips for the Study of Ion Transport. Microfluid Nanofluidics 2021, 25, 51. [CrossRef]

- Crnković, A.; Srnko, M.; Anderluh, G. Biological Nanopores: Engineering on Demand. Life 2021, 11, 27. [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Nothling, M.D.; Zhang, S.; Fu, Q.; Qiao, G.G. Thin Film Composite Membranes for Postcombustion Carbon Capture: Polymers and Beyond. Prog Polym Sci 2022, 126, 101504. [CrossRef]

- Heimann, R.B. Silicon Nitride Ceramics: Structure, Synthesis, Properties, and Biomedical Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 5142. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabagh, A.M.; Yehia, F.Z.; Eshaq, G.; Rabie, A.M.; ElMetwally, A.E. Greener Routes for Recycling of Polyethylene Terephthalate. Egyptian Journal of Petroleum 2016, 25, 53–64. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, V.; Patel, M.R.; Patel, J. V. Pet Waste Management by Chemical Recycling: A Review. J Polym Environ 2010, 18, 8–25. [CrossRef]

- Stephans, L.E.; Myles, A.; Thomas, R.R. Kinetics of Alkaline Hydrolysis of a Polyimide Surface. Langmuir 2000, 16, 4706–4710. [CrossRef]

- Sypabekova, M.; Hagemann, A.; Rho, D.; Kim, S. Review: 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) Deposition Methods on Oxide Surfaces in Solution and Vapor Phases for Biosensing Applications. Biosensors (Basel) 2022, 13, 36. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, C.I.; Rao, S.; Sansom, M.S.P. Water in Nanopores and Biological Channels: A Molecular Simulation Perspective. Chem Rev 2020, 120, 10298–10335. [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Li, P.; Zhao, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Kong, X.-Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xiao, K.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L. Light- and Electric-Field-Controlled Wetting Behavior in Nanochannels for Regulating Nanoconfined Mass Transport. J Am Chem Soc 2018, 140, 4552–4559. [CrossRef]

- Birkner, J.P.; Poolman, B.; Koçer, A. Hydrophobic Gating of Mechanosensitive Channel of Large Conductance Evidenced by Single-Subunit Resolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, 12944–12949. [CrossRef]

- Beckstein, O.; Sansom, M.S.P. Liquid–Vapor Oscillations of Water in Hydrophobic Nanopores. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003, 100, 7063–7068. [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.R.; Cleary, L.; Davenport, M.; Shea, K.J.; Siwy, Z.S. Electric-Field-Induced Wetting and Dewetting in Single Hydrophobic Nanopores. Nat Nanotechnol 2011, 6, 798–802. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Zhou, Y.; Kong, X.-Y.; Xie, G.; Li, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L. Electrostatic-Charge- and Electric-Field-Induced Smart Gating for Water Transportation. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 9703–9709. [CrossRef]

- Junk, A.; Riess, F. From an Idea to a Vision: There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom. Am J Phys 2006, 74, 825–830. [CrossRef]

- Gouaux, E.; MacKinnon, R. Principles of Selective Ion Transport in Channels and Pumps. Science (1979) 2005, 310, 1461–1465. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhou, R.; Zhao, Z.; Bai, B. Nanoconfined Fluids: What Can We Expect from Them? J Phys Chem Lett 2020, 11, 4678–4692. [CrossRef]

- Plecis, A.; Schoch, R.B.; Renaud, P. Ionic Transport Phenomena in Nanofluidics: Experimental and Theoretical Study of the Exclusion-Enrichment Effect on a Chip. Nano Lett 2005, 5, 1147–1155. [CrossRef]

- Silies, L.; Andrieu-Brunsen, A. Programming Ionic Pore Accessibility in Zwitterionic Polymer Modified Nanopores. Langmuir 2018, 34, 807–816. [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Saidi, M.H.; Moosavi, A.; Kröger, M. Tuning Electrokinetic Flow, Ionic Conductance, and Selectivity in a Solid-State Nanopore Modified with a PH-Responsive Polyelectrolyte Brush: A Molecular Theory Approach. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2020, 124, 18513–18531. [CrossRef]

- Gilles, F.M.; Tagliazucchi, M.; Azzaroni, O.; Szleifer, I. Ionic Conductance of Polyelectrolyte-Modified Nanochannels: Nanoconfinement Effects on the Coupled Protonation Equilibria of Polyprotic Brushes. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2016, 120, 4789–4798. [CrossRef]

- Tagliazucchi, M.; Azzaroni, O.; Szleifer, I. Responsive Polymers End-Tethered in Solid-State Nanochannels: When Nanoconfinement Really Matters. J Am Chem Soc 2010, 132, 12404–12411. [CrossRef]

- Tagliazucchi, M.; Szleifer, I. Stimuli-Responsive Polymers Grafted to Nanopores and Other Nano-Curved Surfaces: Structure, Chemical Equilibrium and Transport. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 7292. [CrossRef]

- Laucirica, G.; Hernández Parra, L.M.; Huamani, A.L.; Wagner, M.F.; Albesa, A.G.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Marmisollé, W.; Azzaroni, O. Insight into the Transport of Ions from Salts of Moderated Solubility through Nanochannels: Negative Incremental Resistance Assisted by Geometry. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 12599–12610. [CrossRef]

- Kurupath, V.P.; Coasne, B. Mixture Adsorption in Nanoporous Zeolite and at Its External Surface: In-Pore and Surface Selectivity. J Phys Chem B 2023, 127, 9596–9607. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, J.; Pan, S.; Qian, J.; Pan, B. Metastable Zirconium Phosphate under Nanoconfinement with Superior Adsorption Capability for Water Treatment. Adv Funct Mater 2020, 30, 1909014. [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Li, Y.; Fu, Y.; Li, Y. Enzyme Catalysis Induced Polymer Growth in Nanochannels: A New Approach to Regulate Ion Transport and to Study Enzyme Kinetics in Nanospace. Electroanalysis 2018, 30, 328–335. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ye, D.-K.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Lu, T.; Xia, X.-H. Insights into the “Free State” Enzyme Reaction Kinetics in Nanoconfinement. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 1546. [CrossRef]

- Daiguji, H. Ion Transport in Nanofluidic Channels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 901–911. [CrossRef]

- Emmerich, T.; Ronceray, N.; Agrawal, K.V.; Garaj, S.; Kumar, M.; Noy, A.; Radenovic, A. Nanofluidics. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 2024, 4, 69. [CrossRef]

- Tagliazucchi, M.; Szleifer, I. Transport Mechanisms in Nanopores and Nanochannels: Can We Mimic Nature? Materials Today 2015, 18, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Schoch, R.B.; Han, J.; Renaud, P. Transport Phenomena in Nanofluidics. Rev Mod Phys 2008, 80, 839–883. [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Davoodabadi, A.; Huang, D.; Luo, T.; Ghasemi, H. Transport Phenomena in Nano/Molecular Confinements. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 16348–16391. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Liu, G.; Han, Y.; Jin, W. Artificial Channels for Confined Mass Transport at the Sub-Nanometre Scale. Nat Rev Mater 2021, 6, 294–312. [CrossRef]

- Karayannidis, G.P.; Chatziavgoustis, A.P.; Achilias, D.S. Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Recycling and Recovery of Pure Terephthalic Acid by Alkaline Hydrolysis. Advances in Polymer Technology 2002, 21, 250–259. [CrossRef]

- Karnik, R.; Fan, R.; Yue, M.; Li, D.; Yang, P.; Majumdar, A. Electrostatic Control of Ions and Molecules in Nanofluidic Transistors. Nano Lett 2005, 5, 943–948. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Revil, A. Electrochemical Charge of Silica Surfaces at High Ionic Strength in Narrow Channels. J Colloid Interface Sci 2010, 343, 381–386. [CrossRef]

- Stein, D.; Kruithof, M.; Dekker, C. Surface-Charge-Governed Ion Transport in Nanofluidic Channels. Phys Rev Lett 2004, 93, 035901. [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.A.; Abbas, Z.; Kleibert, A.; Green, R.G.; Goel, A.; May, S.; Squires, T.M. Determination of Surface Potential and Electrical Double-Layer Structure at the Aqueous Electrolyte-Nanoparticle Interface. Phys Rev X 2016, 6, 011007. [CrossRef]

- Doblhoff-Dier, K.; Koper, M.T.M. Modeling the Gouy–Chapman Diffuse Capacitance with Attractive Ion–Surface Interaction. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2021, 125, 16664–16673. [CrossRef]

- Martinsen, Ø.G.; Heiskanen, A. Bioimpedance and Bioelectricity Basics; Elsevier, 2023; ISBN 9780128191071.

- Stojek, Z. The Electrical Double Layer and Its Structure. In Electroanalytical Methods; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; pp. 3–9 ISBN 978-3-642-02915-8.

- Saboorian-Jooybari, H.; Chen, Z. Calculation of Re-Defined Electrical Double Layer Thickness in Symmetrical Electrolyte Solutions. Results Phys 2019, 15, 102501. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.J..; Ottewill, R.H..; Rowell, R.L.. Zeta Potential in Colloid Science : Principles and Applications. 2014, 399.

- Zhou, K.; Perry, J.M.; Jacobson, S.C. Transport and Sensing in Nanofluidic Devices. Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry 2011, 4, 321–341. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Alibakhshi, M.A.; Xie, Q.; Riordon, J.; Xu, Y.; Duan, C.; Sinton, D. Exploring Anomalous Fluid Behavior at the Nanoscale: Direct Visualization and Quantification via Nanofluidic Devices. Acc Chem Res 2020, 53, 347–357. [CrossRef]

- Sparreboom, W.; van den Berg, A.; Eijkel, J.C.T. Principles and Applications of Nanofluidic Transport. Nat Nanotechnol 2009, 4, 713–720. [CrossRef]

- Haywood, D.G.; Harms, Z.D.; Jacobson, S.C. Electroosmotic Flow in Nanofluidic Channels. Anal Chem 2014, 86, 11174–11180. [CrossRef]

- Qiao, N.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lu, W.; Li, C. Ion Current Rectification in Asymmetric Nanochannels: Effects of Nanochannel Shape and Surface Charge. Int J Heat Mass Transf 2023, 208, 124038. [CrossRef]

- Laucirica, G.; Albesa, A.G.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Trautmann, C.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Shape Matters: Enhanced Osmotic Energy Harvesting in Bullet-Shaped Nanochannels. Nano Energy 2020, 71, 104612. [CrossRef]

- Karimzadeh, M.; Seifollahi, Z.; Khatibi, M.; Ashrafizadeh, S.N. Impacts of the Shape of Soft Nanochannels on Their Ion Selectivity and Current Rectification. Electrochim Acta 2021, 399, 139376. [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, S.; Sherwood, J.D.; Chang, H.-C. Solid-State Nanopore Hydrodynamics and Transport. Biomicrofluidics 2019, 13, 11301. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Guo, W.; Jiang, L. Biomimetic Smart Nanopores and Nanochannels. Chem Soc Rev 2011, 40, 2385. [CrossRef]

- Kubeil, C.; Bund, A. The Role of Nanopore Geometry for the Rectification of Ionic Currents. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2011, 115, 7866–7873. [CrossRef]

- Cervera, J.; Schiedt, B.; Neumann, R.; Mafé, S.; Ramírez, P. Ionic Conduction, Rectification, and Selectivity in Single Conical Nanopores. J Chem Phys 2006, 124. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, P.; Apel, P.Y.; Cervera, J.; Mafé, S. Pore Structure and Function of Synthetic Nanopores with Fixed Charges: Tip Shape and Rectification Properties. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 315707. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, L. Asymmetric Ion Transport through Ion-Channel-Mimetic Solid-State Nanopores. Acc Chem Res 2013, 46, 2834–2846. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, P.Y.; Hsu, J.P. Influence of Shape and Charged Conditions of Nanopores on Their Ionic Current Rectification, Electroosmotic Flow, and Selectivity. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp 2023, 658, 130696. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Wen, L.; Jiang, L. Biomimetic Solid-State Nanochannels: From Fundamental Research to Practical Applications. Small 2016, 12, 2810–2831. [CrossRef]

- White, H.S.; Bund, A. Ion Current Rectification at Nanopores in Glass Membranes. Langmuir 2008, 24, 2212–2218. [CrossRef]

- Vlassiouk, I.; Smirnov, S.; Siwy, Z. Ionic Selectivity of Single Nanochannels. Nano Lett 2008, 8, 1978–1985. [CrossRef]

- Yameen, B.; Ali, M.; Neumann, R.; Ensinger, W.; Knoll, W.; Azzaroni, O. Ionic Transport Through Single Solid-State Nanopores Controlled with Thermally Nanoactuated Macromolecular Gates. Small 2009, 5, 1287–1291. [CrossRef]

- Punekar, N.S. ENZYMES: Catalysis, Kinetics and Mechanisms; Springer Nature Singapore: Singapore, 2025; ISBN 978-981-97-8178-2.

- Berg, J.M.; Gatto, G.J.; Hines, J.K.; Tymoczko, J.L. Biochemistry (-2024); Macmillan Learning, 2024; ISBN 1319417469.

- Gao, Y.; Kyratzis, I. Covalent Immobilization of Proteins on Carbon Nanotubes Using the Cross-Linker 1-Ethyl-3-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)Carbodiimide—a Critical Assessment. Bioconjug Chem 2008, 19, 1945–1950. [CrossRef]

- Arafat, A.; Giesbers, M.; Rosso, M.; Sudhölter, E.J.R.; Schroën, K.; White, R.G.; Yang, L.; Linford, M.R.; Zuilhof, H. Covalent Biofunctionalization of Silicon Nitride Surfaces. Langmuir 2007, 23, 6233–6244. [CrossRef]

- Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Rocha-Martin, J.; Moreno-Gamero, D. Enzyme Immobilization Strategies for the Design of Robust and Efficient Biocatalysts. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem 2022, 35, 100593. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yin, Y.; Yang, Y.; Russell, T.P.; Shi, S. Layer-by-Layer Engineered All-Liquid Microfluidic Chips for Enzyme Immobilization. Advanced Materials 2022, 34, 2105386. [CrossRef]

- Ariga, K.; Ji, Q.; Hill, J.P. Enzyme-Encapsulated Layer-by-Layer Assemblies: Current Status and Challenges Toward Ultimate Nanodevices. In; Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010; pp. 51–87 ISBN 978-3-642-12873-8.

- Argaman, O.; Ben-Barak Zelas, Z.; Fishman, A.; Rytwo, G.; Radian, A. Immobilization of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase on Montmorillonite Using Polyethyleneimine as a Stabilization and Bridging Agent. Appl Clay Sci 2021, 212, 106216. [CrossRef]

- Mantione, D.; del Agua, I.; Schaafsma, W.; ElMahmoudy, M.; Uguz, I.; Sanchez-Sanchez, A.; Sardon, H.; Castro, B.; Malliaras, G.G.; Mecerreyes, D. Low-Temperature Cross-Linking of PEDOT:PSS Films Using Divinylsulfone. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2017, 9, 18254–18262. [CrossRef]

- Morales-Sanfrutos, J.; Lopez-Jaramillo, F.; Elremaily, M.; Hernández-Mateo, F.; Santoyo-Gonzalez, F. Divinyl Sulfone Cross-Linked Cyclodextrin-Based Polymeric Materials: Synthesis and Applications as Sorbents and Encapsulating Agents. Molecules 2015, 20, 3565–3581. [CrossRef]

- Ruckenstein, E.; Rajora, P. Optimization of the Activity in Porous Media of Proton-generating Immobilized Enzymatic Reactions by Weak Acid Facilitation. Biotechnol Bioeng 1985, 27, 807–817. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; An, P.; Qin, C.; Sun, C.-L.; Sun, M.; Ji, Z.; Wang, C.; Du, G.; Liu, J.; Xie, Y. Bioinspired Dual-Responsive Nanofluidic Diodes by Poly-L-Lysine Modification. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 4501–4506. [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Hou, L.; Duan, X.; Shi, T.; Li, W.; Shi, A.-C. Translocation of Micelles through a Nanochannel. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 6487–6492. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wang, D.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, L. Ion/Molecule Transportation in Nanopores and Nanochannels: From Critical Principles to Diverse Functions. J Am Chem Soc 2019, 141, 8658–8669. [CrossRef]

- Perez Sirkin, Y.A.; Vigil De Maio, M.; Tagliazucchi, M. Mechanisms of Enzymatic Transduction in Nanochannel Biosensors. Chem Asian J 2022, 17, e202200588. [CrossRef]

- Vilozny, B.; Actis, P.; Seger, R.A.; Pourmand, N. Dynamic Control of Nanoprecipitation in a Nanopipette. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 3191–3197. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Jimenez, M.; Lugli-Arroyo, J.; Fenoy, G.E.; Piccinini, E.; Knoll, W.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Transduction of Amine–Phosphate Supramolecular Interactions and Biosensing of Acetylcholine through PEDOT-Polyamine Organic Electrochemical Transistors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16, 61419–61427. [CrossRef]

- Laucirica, G.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Dangerous Liaisons: Anion-Induced Protonation in Phosphate–Polyamine Interactions and Their Implications for the Charge States of Biologically Relevant Surfaces. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2017, 19, 8612–8620. [CrossRef]

- Laucirica, G.; Pérez-Mitta, G.; Toimil-Molares, M.E.; Trautmann, C.; Marmisollé, W.A.; Azzaroni, O. Amine-Phosphate Specific Interactions within Nanochannels: Binding Behavior and Nanoconfinement Effects. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2019, 123, 28997–29007. [CrossRef]

| Technology | Materials | *Diameter (nm) | Shape | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EBL + RIE | Si3N4 | Around 20 | Rectangular | [55] |

| RIE/ FIB + IBS | Si3N4 | 1,8-100 | Cylindrical-bowl shaped cavity | [56] |

| FIB + IBS | Si3N4 /Si | >1 | Cylindrical-bowl shaped cavity | [57] |

| FIB | Au/Si3N4/Au; PFA/Si3N4/PFA | 20-140 | Conically narrowing | [58] |

| EE-PEO | PDMS | >100 | Cylindrical |

[59] |

| Bench-Top | Glass based | > 86 | Conical | [60] |

| Bench-Top/Laser pulling | Glass based | > 40 | hourglass | [61] |

| Thermal pulling | Glass based borosilicate | Around 30 | Surficial (rectangular and conical) | [62] |

| EB + Dry etching + FIB | Silica glass substrate | 58-655 |

Conical-Trumpet shaped | [63] |

| Ion track + Dry Plasma etching | PC | 10-1000 variable | Etching dependent | [64] |

| Ion Track + UV exposure + Chemical etching | PET, PC, PP, PVDF, PI | 5-300 variable | [65] | |

| PET | 50-600 variable | [66] | ||

| Ion Track + UV exposure + Chemical/Electrochemical etching | PC | > 2 nm variable | [67] | |

| Ion Track + Chemical/Electrochemical etching | PET, PC, PI, PVDF | [30] | ||

| Ion Track + Chemical Etching |

PET, PC, PI, PVDF, PP | [68] | ||

| PET, PC, PI, PVDF, SiO2, Mica | [69] | |||

| PET, PC, PI, PVDF, PP, CR39 | [70] | |||

| PET | [71] | |||

| PET, PC | > 100 variable | [72] | ||

| PI | 10-1000 variable | [73] | ||

| SiN | >100 | [74] |

| KCl (M) | Debye length (nm) |

| 10 | 0.3 |

| 10-1 | 1.0 |

| 10-2 | 3.1 |

| 10-3 | 9.6 |

| 10-4 | 30.5 |

| 10-5 | 96.3 |

| Year | target | LOD (µM) | Dynamic ranges (µM) | Response time (min) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 | Urea | 10 | 10-10000 | ≈1 | [103] |

| 2025 | Adenosine | 0.01 | 0.01-500 | 4 | [104] |

| 2025 | Arginine | 3 | 30-3000 | 5 | [92] |

| 2025 | Creatinine | 0.005 | 0.005-100 | 2.5 | [91] |

| 2024 | Urea | 0.0001 | 0.0001-0.01 and 0.001-1 | ≈3 | [90] |

| 2022 | Acetylcholine | 0.016 | 0.001-22.5 and 25-100 | ≈3 | [89] |

| 2018 | Urea | 0.001 | 0.001-1 | 1.5 | [88] |

| 2017 | H2O2 | 500 | 500 Qualitative analyses | 0.01-1.4 | [105] |

| 2014 | Glucose | 15 | 15-100 | ≈10 | [96] |

| 2014 | Glucose | 0.001 | 0.001-1000 | N/F | [99] |

| 2011 | Concanavalin A | 10 | 10 Qualitative analyses | 180 | [106] |

| 2011 | H2O2 | 0.01 | 0.01-1 | 0.8-1.6 | [107] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).