Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

02 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

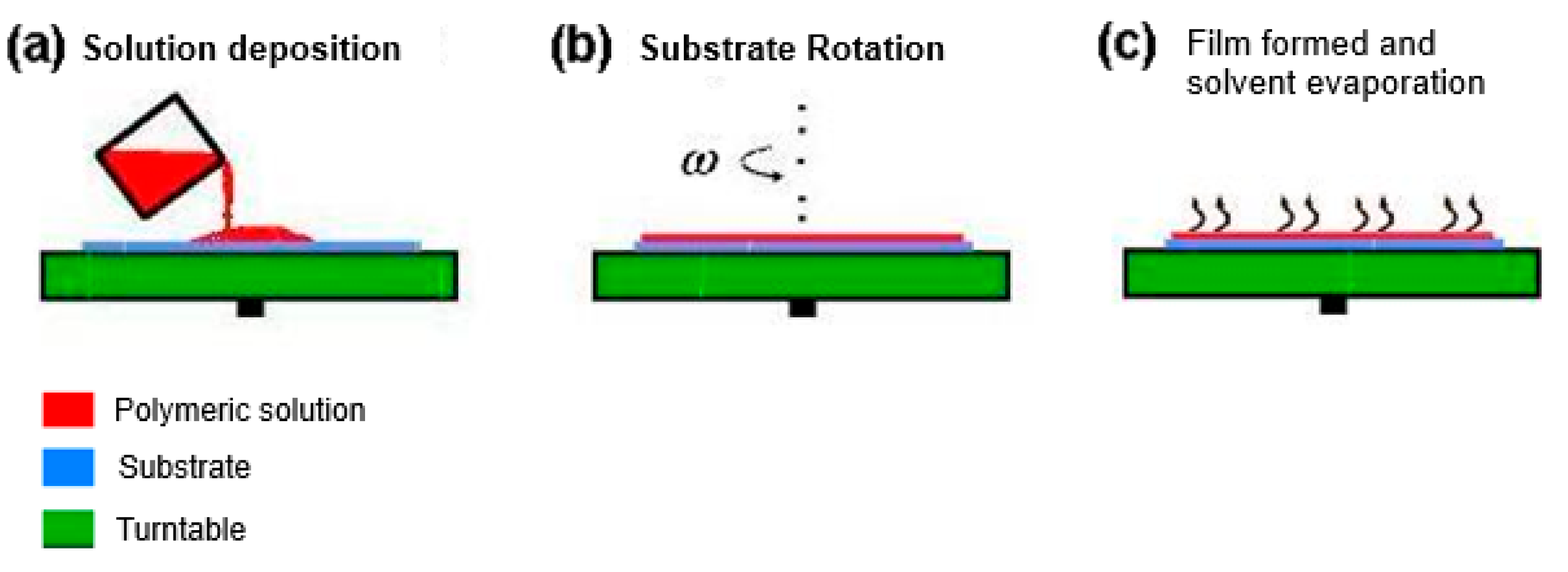

2.1. PMMA Thin Films Deposition

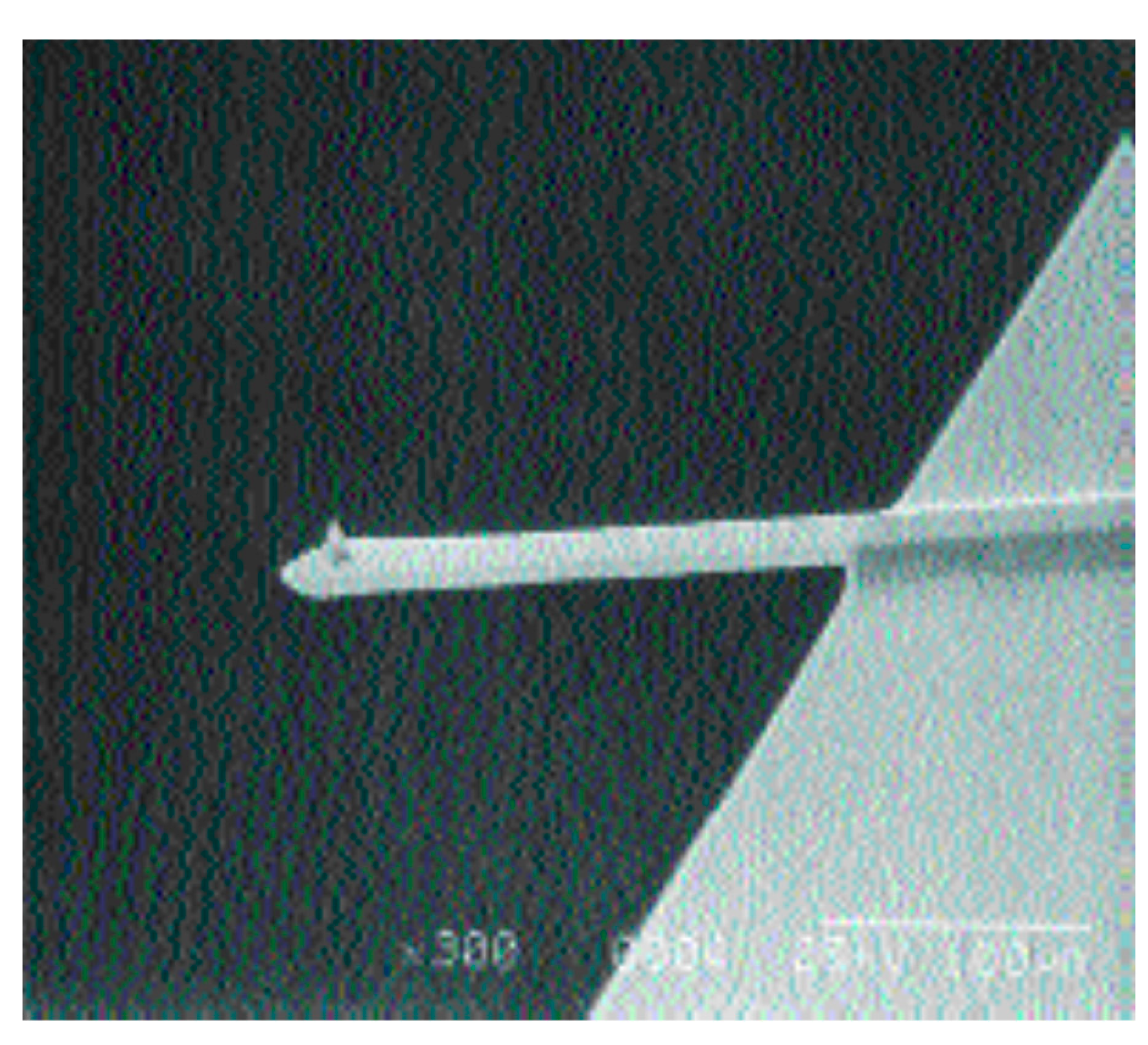

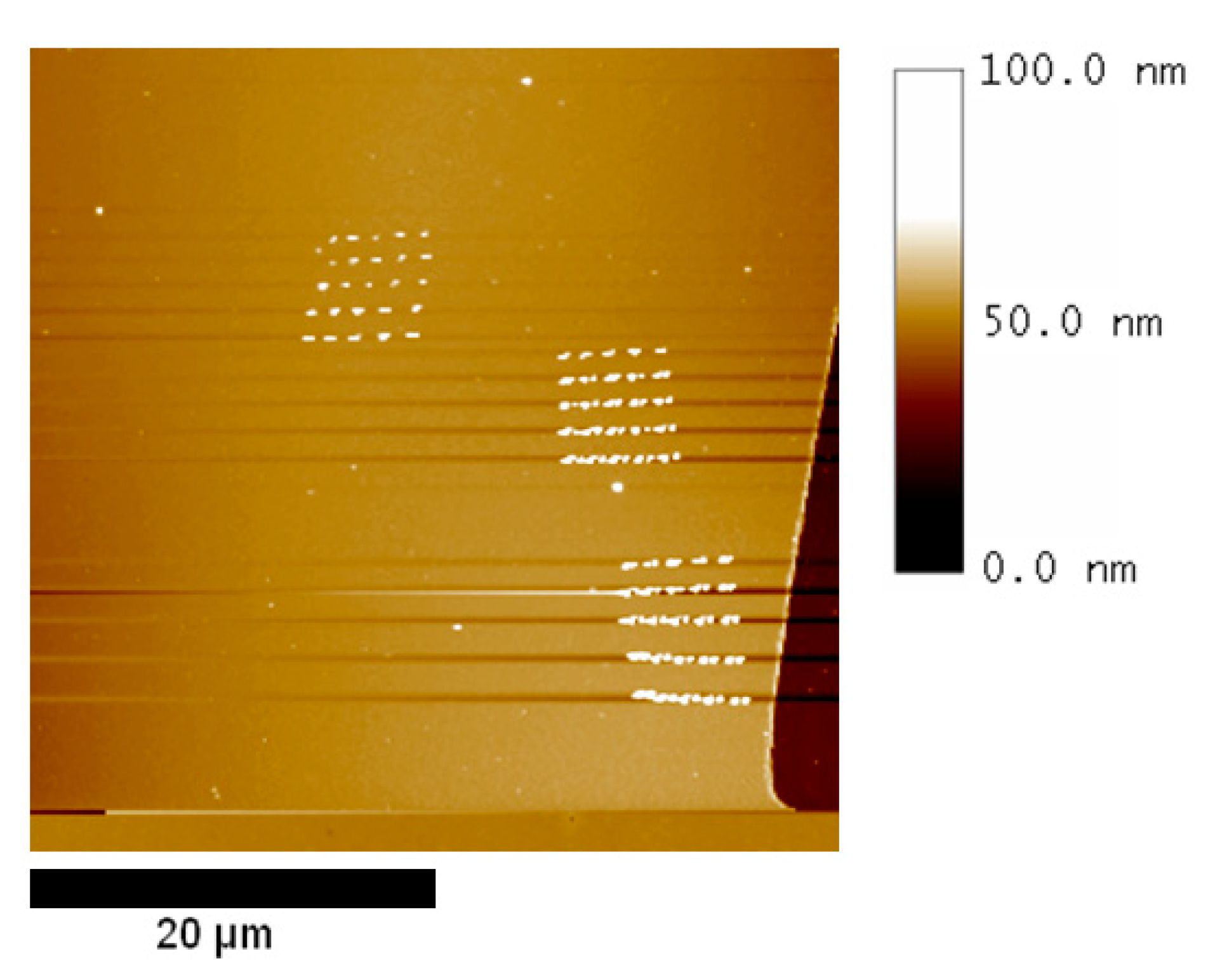

2.2. Nanoestructuring Processes and Image Acquisition

3. Results and Discussion

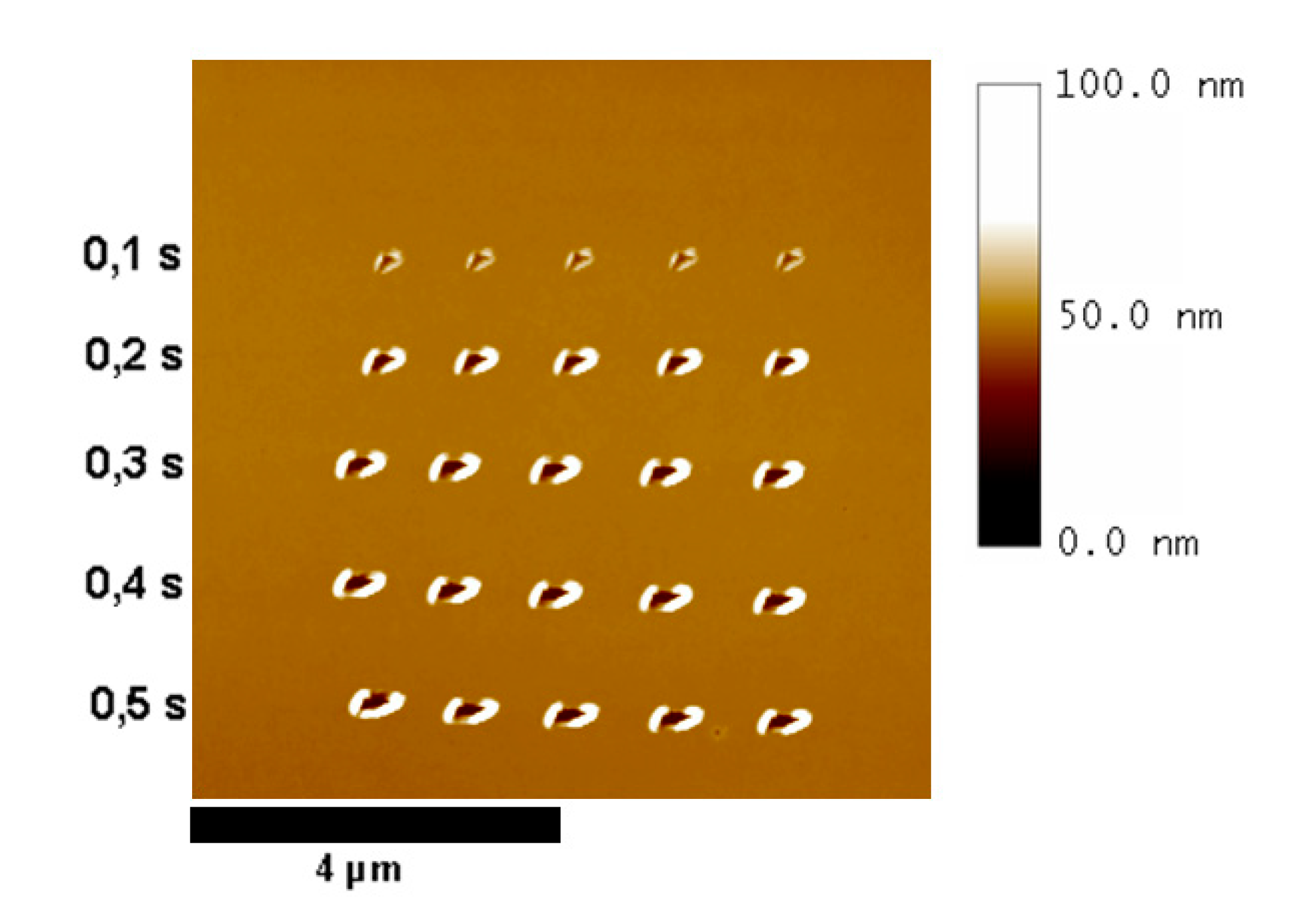

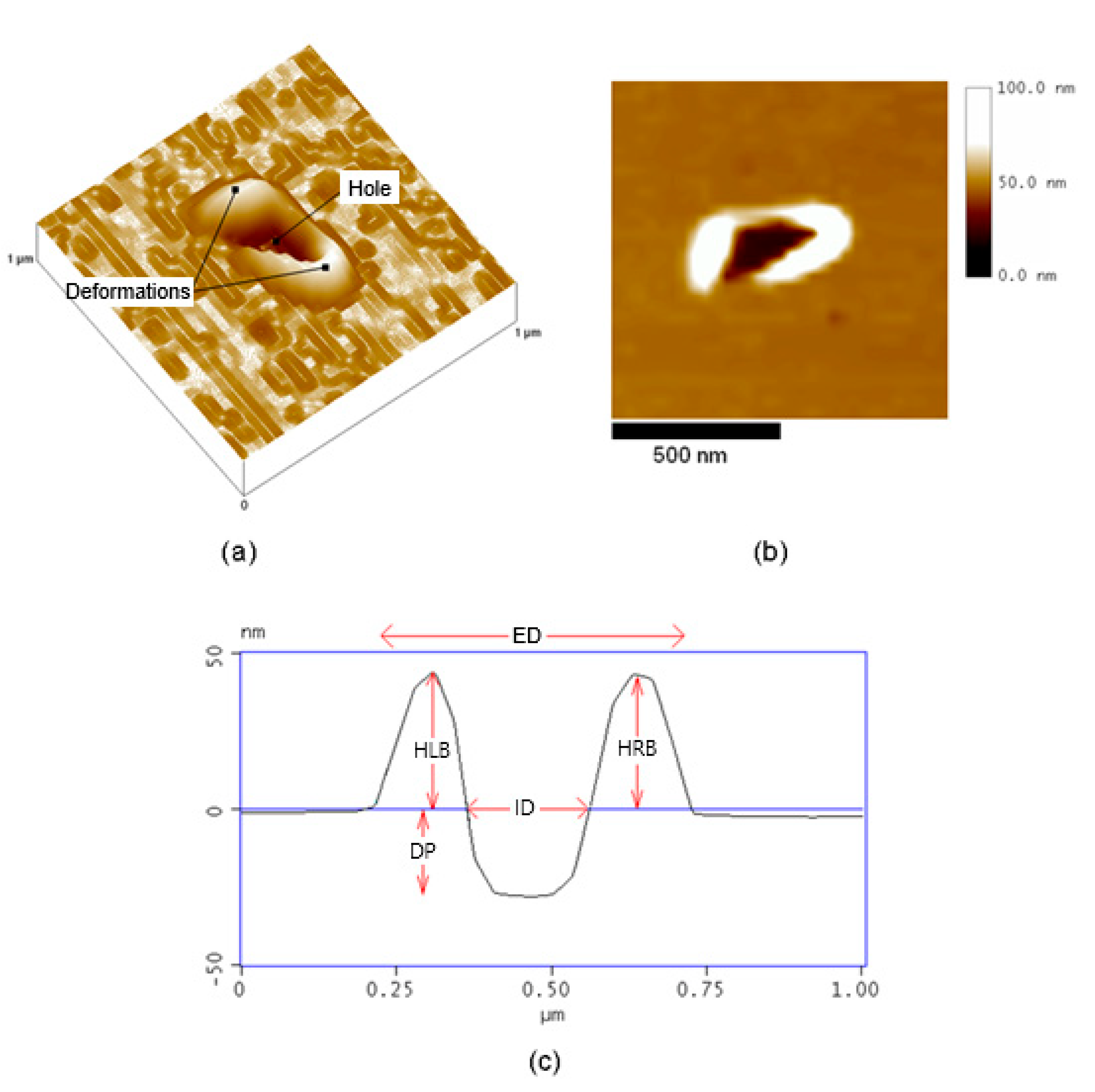

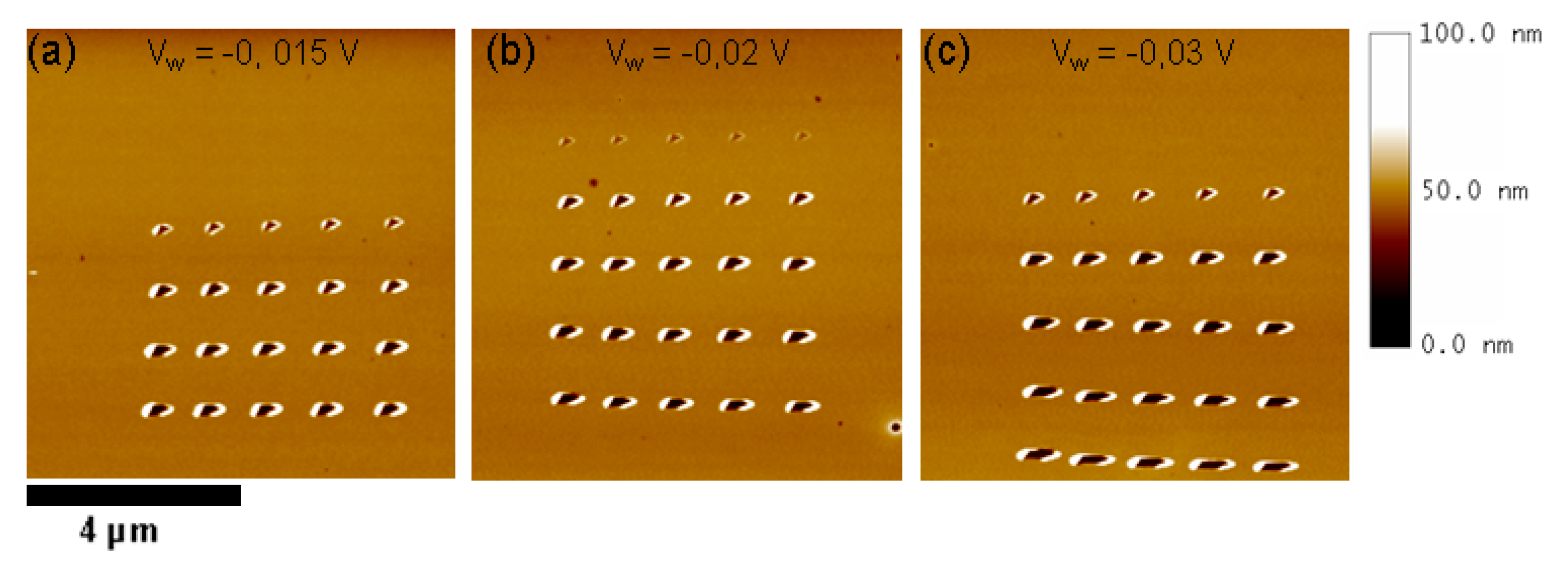

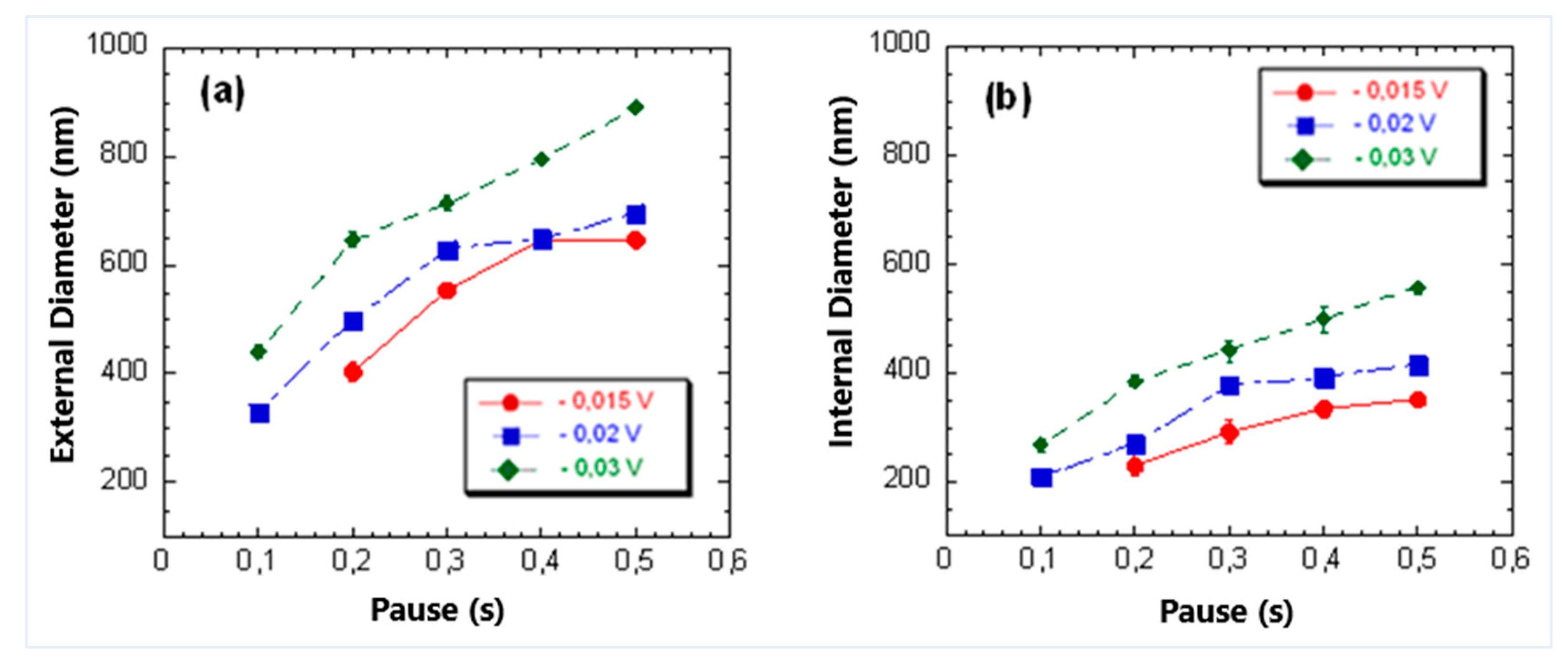

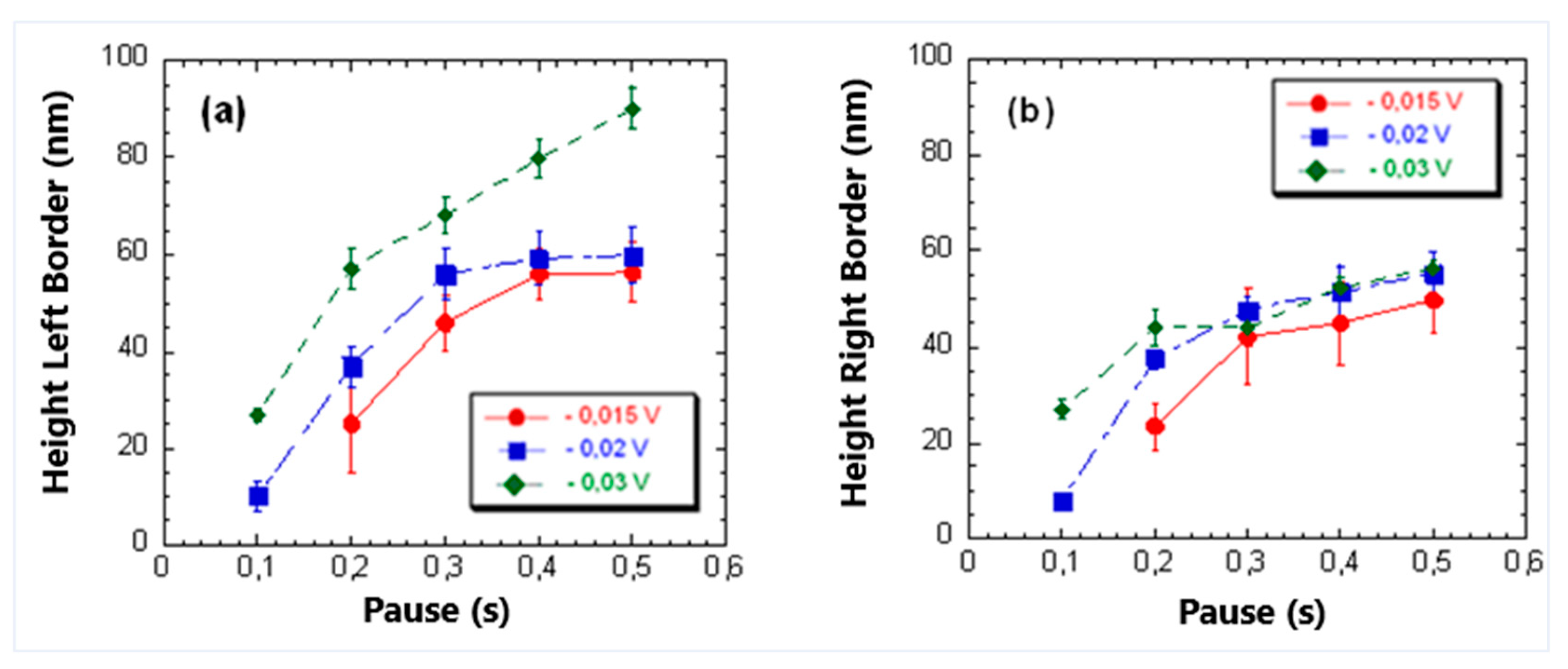

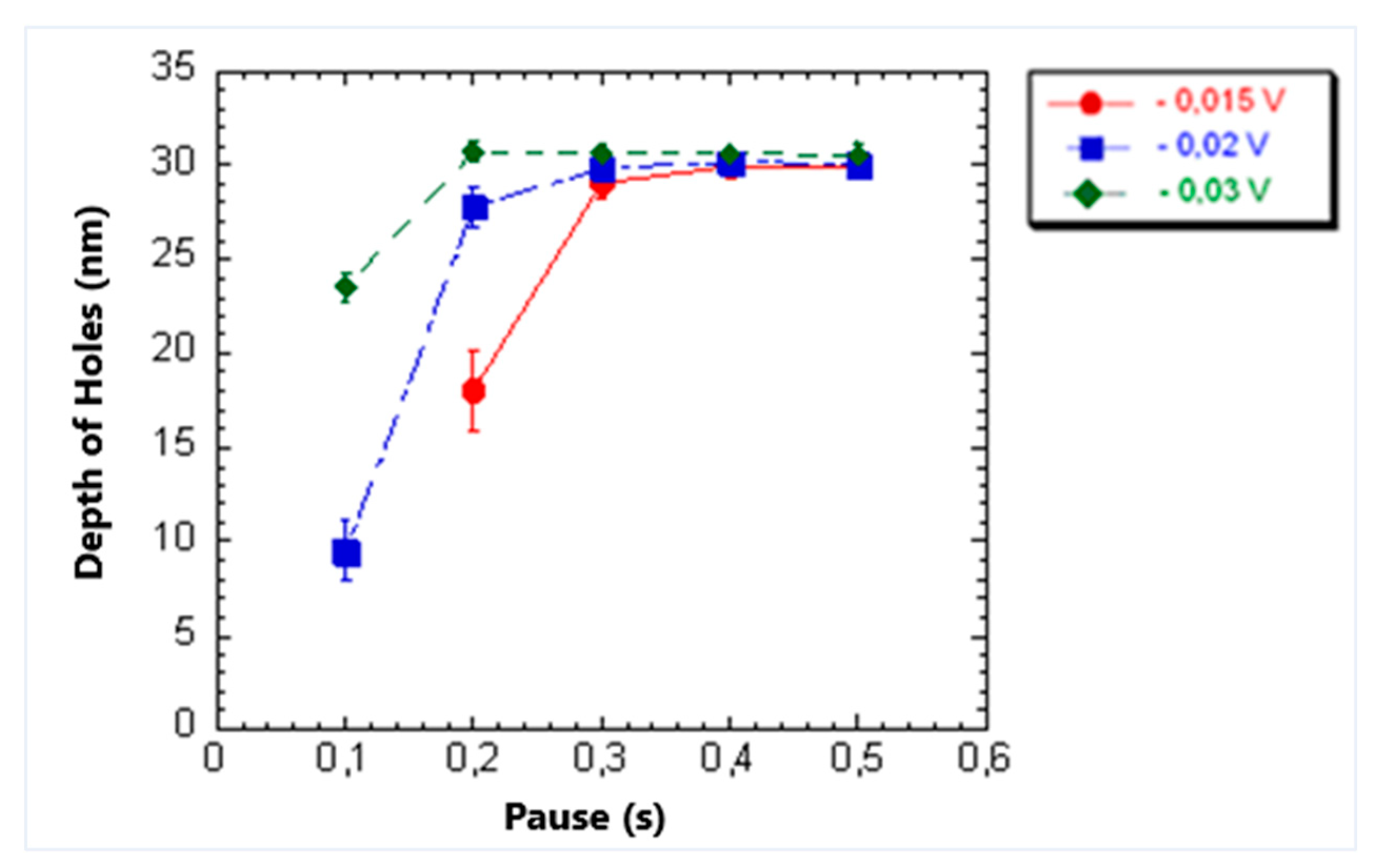

3.1. Influence of Pause and Writing Set Point on Dimensions of the Mechanically Induced Structures

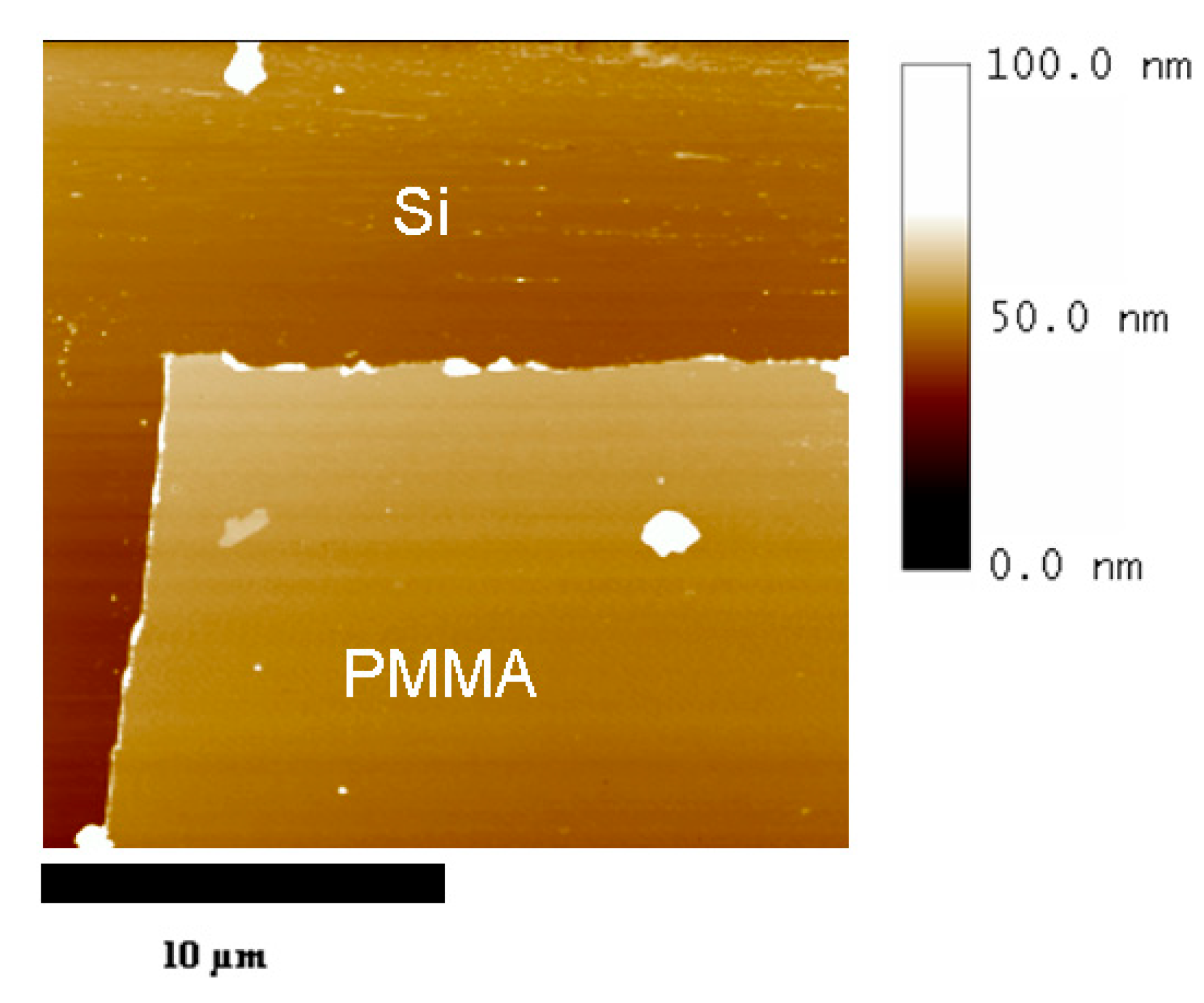

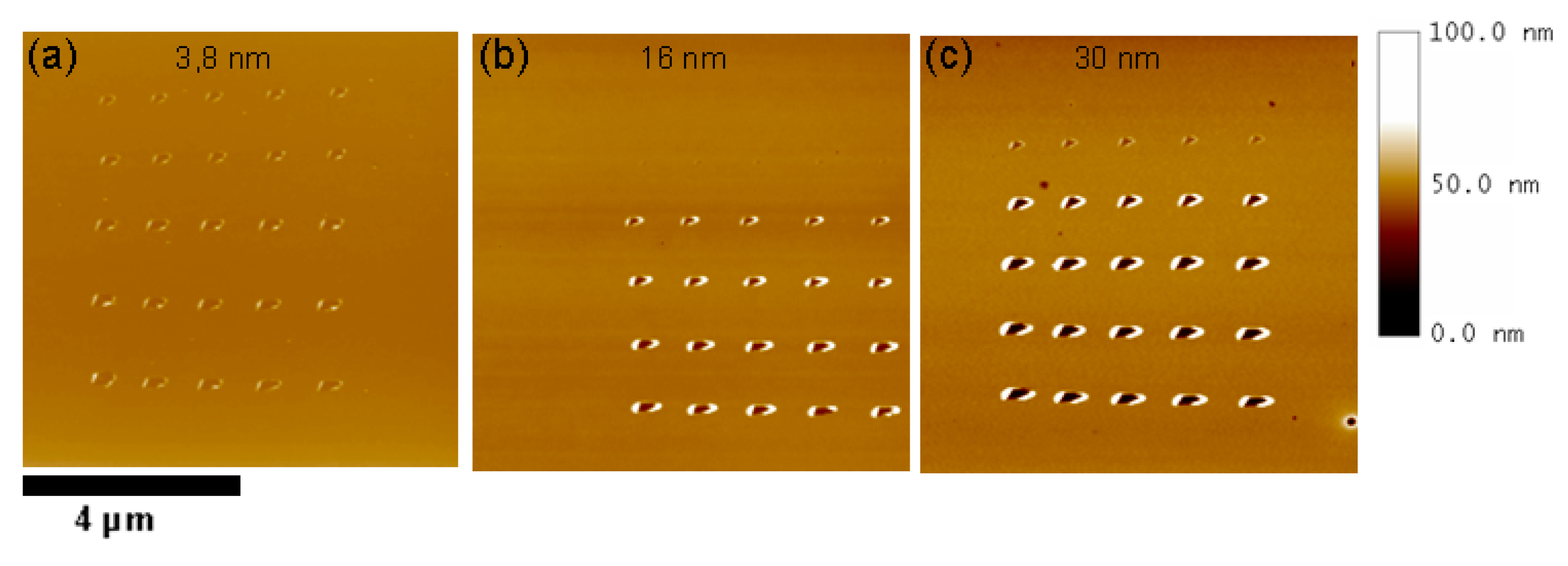

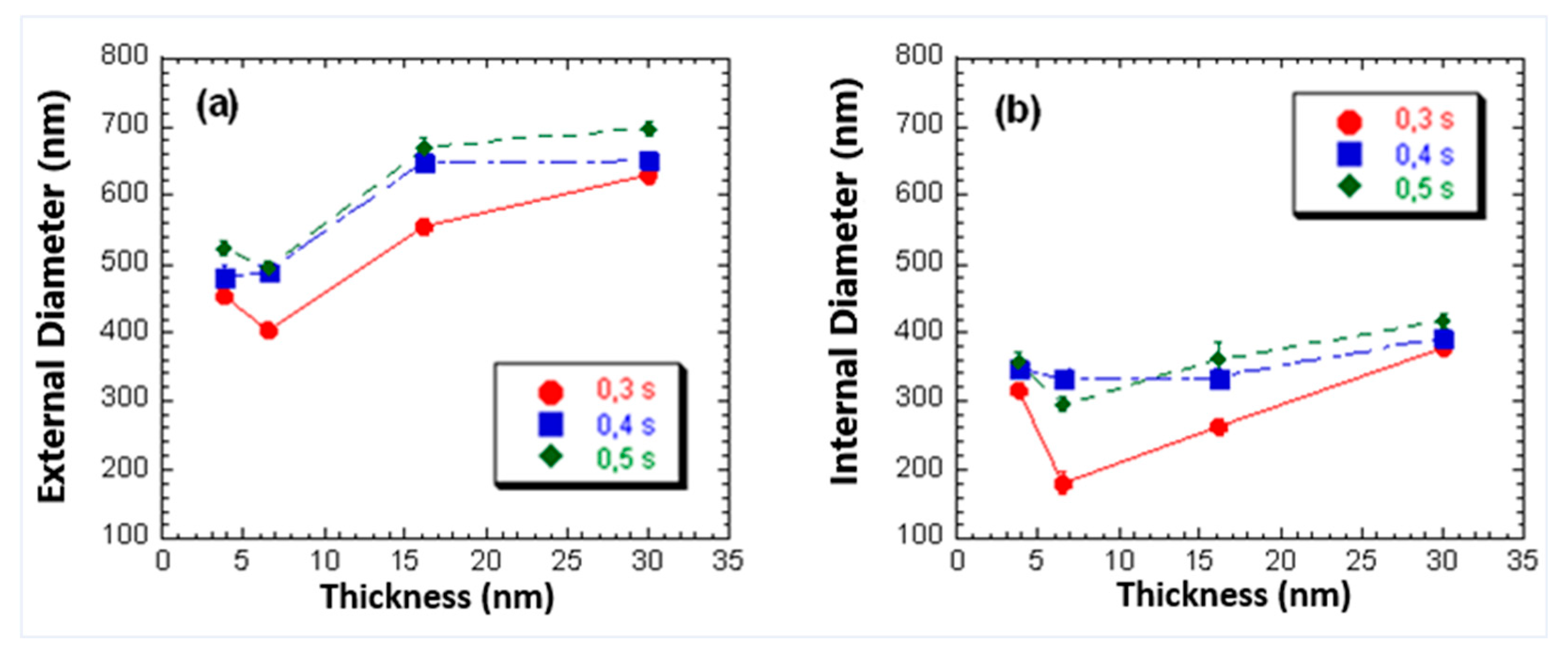

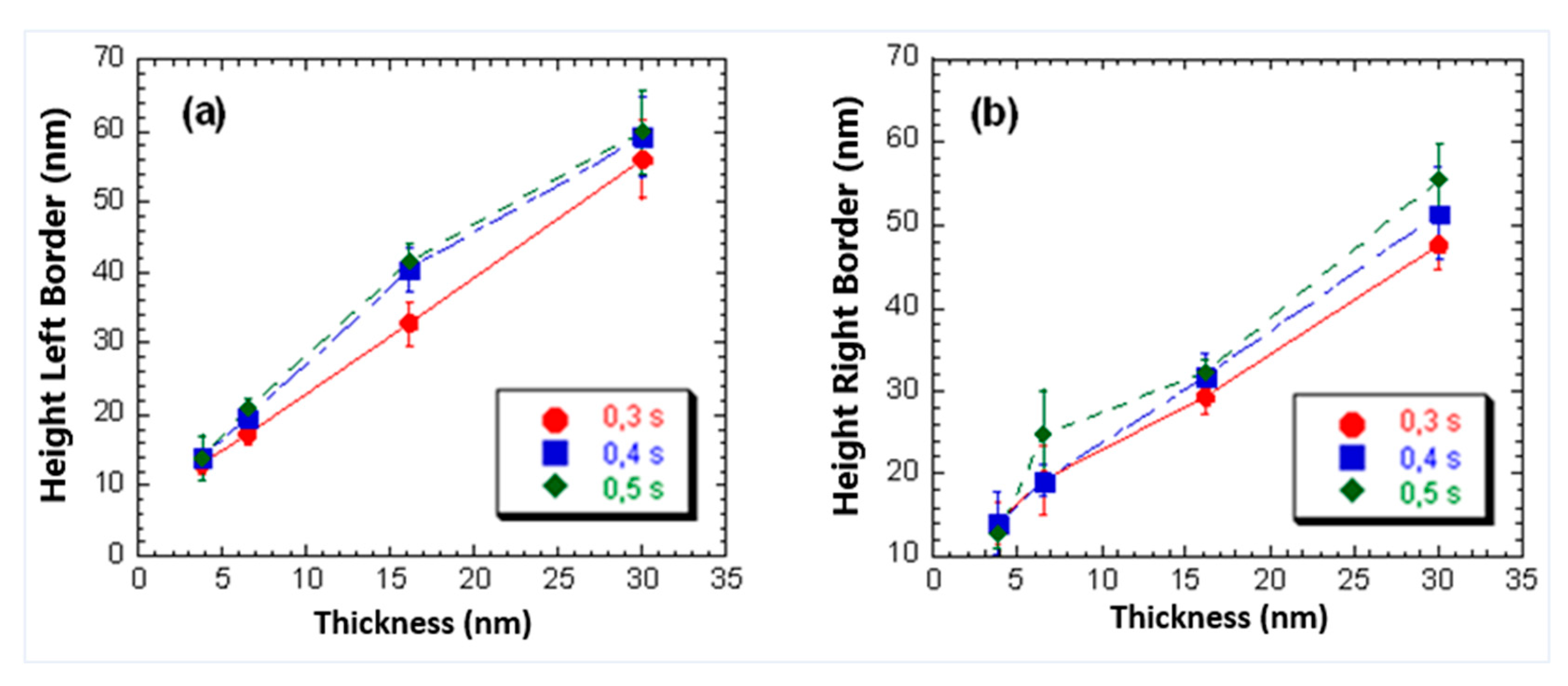

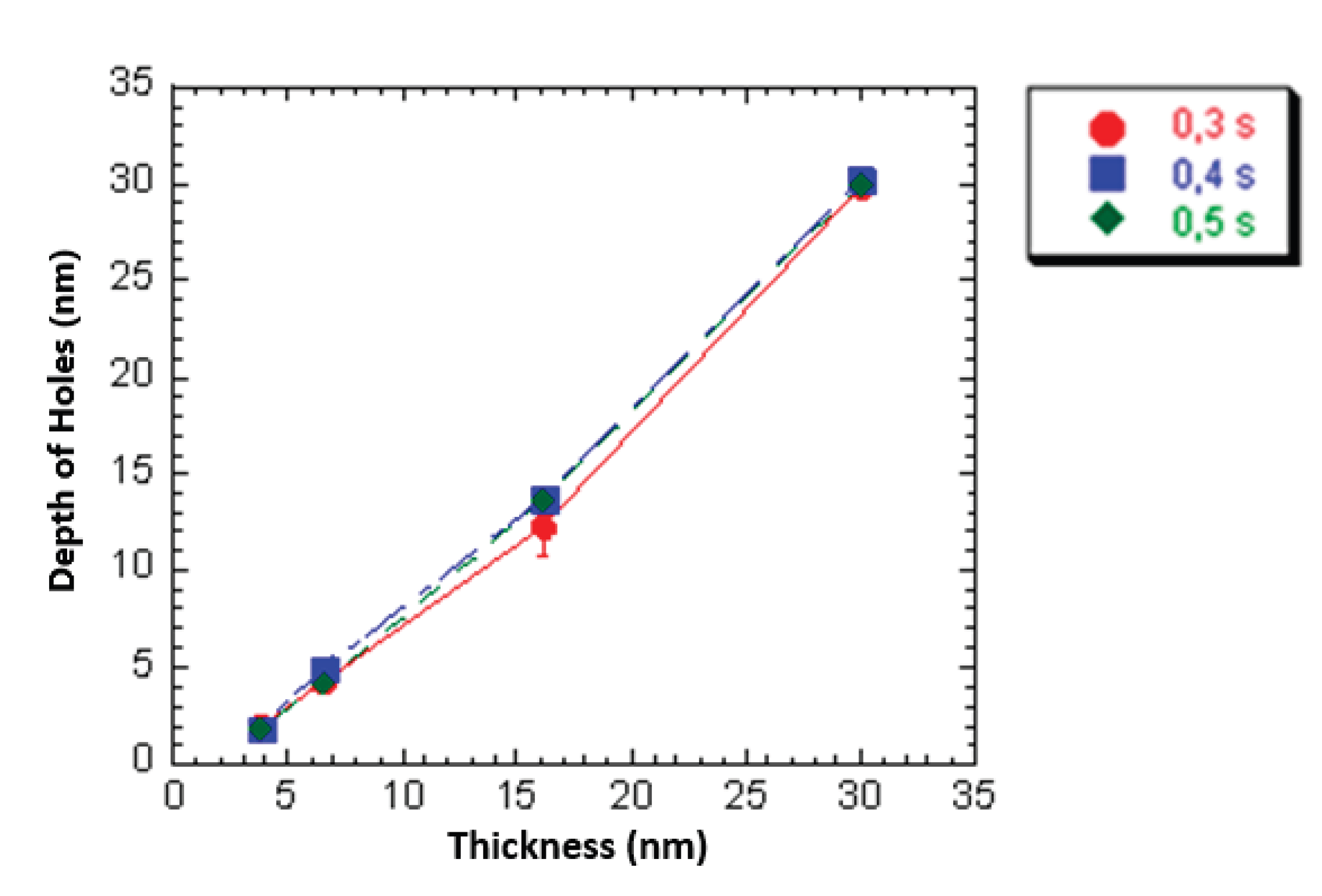

3.2. Influence of Film Thickness on Dimensions of the Mechanically Induced Structures

References

- BINNIG, G.; Rohrer, H.; Gerber, Ch.; Weibel, E. Surface studies by scanning tunneling microscopy, Physical Review Letters, v. 49, p. 57-61, 1982. [CrossRef]

- KRIVOSHAPKINA, Y.; Kaestner, M.; Rangelow, I. W. ; Tip-based nanolithography methods and materials, Frontiers of Nanoscience, v. 11, p. 497-542, 2016. [CrossRef]

- SNOW, E. S.; Campbell, P. M. Fabrication of Si nanostructures with an atomic force microscope, Applied Physics Letters, v. 64, n. 15, p. 1932-1934, 1994. [CrossRef]

- CAMPBELL, P. M.; Snow, E. S. Proximal probe-based fabrication of nanostructures, Semiconductor Science and Technology, v. 11, n. 11s, p. 1558-1562, 1996. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA360216.

- HIRONAKA, K.; Aoki, K.; Hori, H.; Yamada, S. Nano-Fabrication on GaAs Surface by Resist Process with Scanning Tunneling Microscope Lithography, Japanese Journal of Applied Physics, v. 36, n. 6B, p. 3839-3843, 1997. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1143/JJAP.36. 3839. [Google Scholar]

- MARRIAN, C. R. K.; Dobisz, E. A. Electron-beam lithography with scanning tunneling microscope, Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology B, v. 10, n. 6, p. 2877-2881, 1992. https://zenodo. 1236. [Google Scholar]

- KRAGLER, K.; Günther, E.; Leuschner, R.; Falk, G.; Seggern, H. Low-voltage electron-beam lithography with scanning tunneling microscopy in air: A new method for producing structures with high aspect ratios, Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology B, v. 14, n. 2, p. 1327-1330, 1996. [CrossRef]

- WENDEL, M.; Irmer, B.; Cortes, J.; Kaiser, R.; Lorenz, H.; Kotthaus, J. P.; Lorke, A. Nanolithography with an atomic force microscope, Superlattices and Microstructures, v. 20, n. 3, p. 349-356, 1996. https://www.nano.physik.uni-muenchen.de/nanophysics/_assets/pdf/1996/96-30_Wendel_SuperlMicrostr.

- AVRAMESCU, A.; Uesugi, K.; Suemune, I. Atomic Force Microscope Nanolithography on SiO2/Semiconductor Surfaces. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics, v. 36, n. 6B, p. 4057-4060, 1997. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1143/JJAP.36. 4057. [Google Scholar]

- KLEHN, B.; Kunze, U. Nanolithography with an atomic force microscope by means of vector-scan controlled dynamic plowing, Journal of Applied Physics, v. 85, n. 7, p. 3897-3903, 1999. [CrossRef]

- SNOW, E.S.; Campbell, P.M.; Perkins, F.K. Nanofabrication with proximal probes, Proceedings of the IEEE, v. 85, n. 4, p. 601-611, 1997. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp? 5737. [Google Scholar]

- XIE, X. N.; Chung, H. J.; Sow, C. H.; Wee, A. T. S. Nanoescale materials patterning and engineering by atomic force microscopy nanolithography, Materials Science and Engineering R, v. 54, p. 1-48, 2006. [CrossRef]

- GENG, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Yan, Y. ; Liu, Y; Fabrication of periodic nanostructures for SERS substrates using multi-tip probe-based nanomachining approach, Applied Surface Science, v. 576. Part b, 2022. [CrossRef]

- MCCORD, M. A.; Kern, D. P.; Chang, T. H. P. Direct deposition of 10-nm metallic features with scanning tunneling microscope, Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology B, v. 6, n. 6, p. 1877-1880, 1988. [CrossRef]

- EHRICHS, E. E.; Silver, R. M.; Lozanne, A. L. Direct writing with the scanning tunneling microscope, Journal of Vacuum Science and Technology A, v. 6, n. 2, p. 540-543, 1988. [CrossRef]

- EHRICHS, E. E.; Yoon, S.; Lozanne, A. L. Direct writing of 10 nm features with the scanning tunneling microscope, Applied Physics Letters, v. 53, n. 23, p. 2287-2289, 1988. [CrossRef]

- KANESHIRO, C.; Okumura, T. Nanofabrication on n-GaAs surface using a scanning tunnelling microscope in a Ni-salt solution, Thin Solid Films, v. 281-282, n. 1-2, p. 606-609, 1996. [CrossRef]

- CHEN, Y.; Hsu, J.; Lin, H. Fabrication of metal nanowires by atomic force microscopy nanoscratching and lift-off process, Nanotechnology, v. 16, p. 1112-115, 2005. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10. 1088. [Google Scholar]

- TSENG, A. A.; Notargiacomo, A.; Chen, T. P. Nanofabrication by scanning probe lithography: A review. B, 2005; 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WIESAUER, K.; Springholz, G. Fabrication of semiconductor nanostructures by nanoindentation of photoresist layers using atomic force microscopy. Journal of Applied Physics, v. 88, n. 12, p. 7289-7297, 2000. [CrossRef]

- WEISENHORN, A. L.; Mac Dougall, J. E.; Gould, S. A. C.; Cox, S. D.; Wise, W. S.; Massie, J.; Maivald, P.; Elings, V. B.; Stucky, G. D.; Hansma, P. K. Imaging and Manipulating Molecules on a Zeolite Surface with an Atomic Force Microscope, Science, v. 247, p. 1330-1333, 2009. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.247.4948. 1330. [Google Scholar]

- RUSSELL, P.; Batchelor, D.; Thornton, J. SEM and AFM: Complementary Techniques for High Resolution Surface Investigations, Veeco Metrology Group. https://www.researchgate. 2374. [Google Scholar]

- GENG, Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, J.; Fang, Z.; He, Y. Implementation of AFM tip-based nanostcratching process on single crystal copper: Study of material removal state, Applied Surface Science, v. 459, p. 723-731, 2018. [CrossRef]

| Concentratiom (g/L) | Thickness (nm) | Standard Deviation (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3,8 | 0,8 |

| 3 | 6,5 | 0,5 |

| 5 | 16 | 0,9 |

| 15 | 30 | 2,9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).