2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

The experimental site is a long-term stationary field experiment at the Experimental Station of Vytautas Magnus University Agriculture Academy. The station is located on the left bank of the Nemunas River, Ringaudai municipality, Kaunas district, south-western side of Kaunas city. The long-term field experiment is led by V. Bogužas. For more than 20 years, various experimental agronomic research has been carried out here under a uniform and well-established tillage system. The field soil of the experiment is a deeper gleyic saturated loamy soil according to the Lithuanian soil classification (LTDK–99) [

11,

12], and according to the international classification [

12] it is

Epieutric Endocal-caric Endogleyic Planosol (Endoclayic, Aric, Drainic, Humic, Episiltic).

Experimental variants:

1. Normal deep plowing at a depth of 23–25 cm (DP) (control—comparative variant);

2. Shallow plowing at a depth of 12–14 cm (SP);

3. Deep cultivation (with a cultivator with arrow-shaped cultivator points) at a depth of 23–25 cm (DC);

4. Shallow cultivation (with a disk cultivator) at a depth of 8–10 cm (SC);

5. No-tillage (NT).

Crop rotation in the experiment: 1) winter oilseed rape; 2) winter wheat; 3) beans; 4) spring barley.

The experiment is set up in four replicates. The initial size of the fields was 126 m2 (14 × 9 m) and the reference size was 70 m2 (10 × 7 m). The experimental fields are laid out in a randomized manner. The total number of fields in the experiment is 20. The buffer zone is 1 m wide per field and 9 m wide between replicates.

Table 1.

Agro-technical measures and timing for spring barley cultivation.

Table 1.

Agro-technical measures and timing for spring barley cultivation.

| Operation |

Year |

| 2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

| Cultivated 1st time |

04/13/2022 |

04/07/2023 |

04/07/2024 |

| Cultivated 2nd time |

04/18/2022 |

04/14/2023 |

04/10/2024 |

| Sprayed with “Glyphogan” 360 SL 3 l ha-1 5 var. (direct sowing) |

04/19/2022 |

04/11/2023 |

04/10/2024 |

| Sown spring barley ‘Crescendo’, seed rate 180 kg ha-1, sowing depth 3 cm |

04/21/2022 |

04/19/2023 |

04/11/2024 |

| Fertilized with N16P16K16 300 kg ha-1

|

04/21/2022 |

04/18/2023 |

04/11/2024 |

| Fertilized with N34.4 125 kg ha-1 ammonium nitrate |

05/15/2022 |

06/01/2023 |

05/03/2024 |

| Sprayed with “Elegant® 2FD” 0.4 l ha-1 |

05/10/2022 |

05/11/2023 |

05/17/2024 |

| Sprayed with “MCPA 750” 1.0 l ha-1 (in a collection with an undersown) |

05/10/2022 |

05/22/2023 |

05/17/2024 |

| Sprayed with “Mirador 250 SC” 0.8 l ha-1

|

- |

06/14/2023 |

05/29/2024 |

| Spring barley harvested |

08/04/2024 |

08/10/2024 |

08/10/2024 |

The experimental fields are arranged in a randomized way. There are 20 fields in total in the experiment.

2.2. Meteorological Conditions

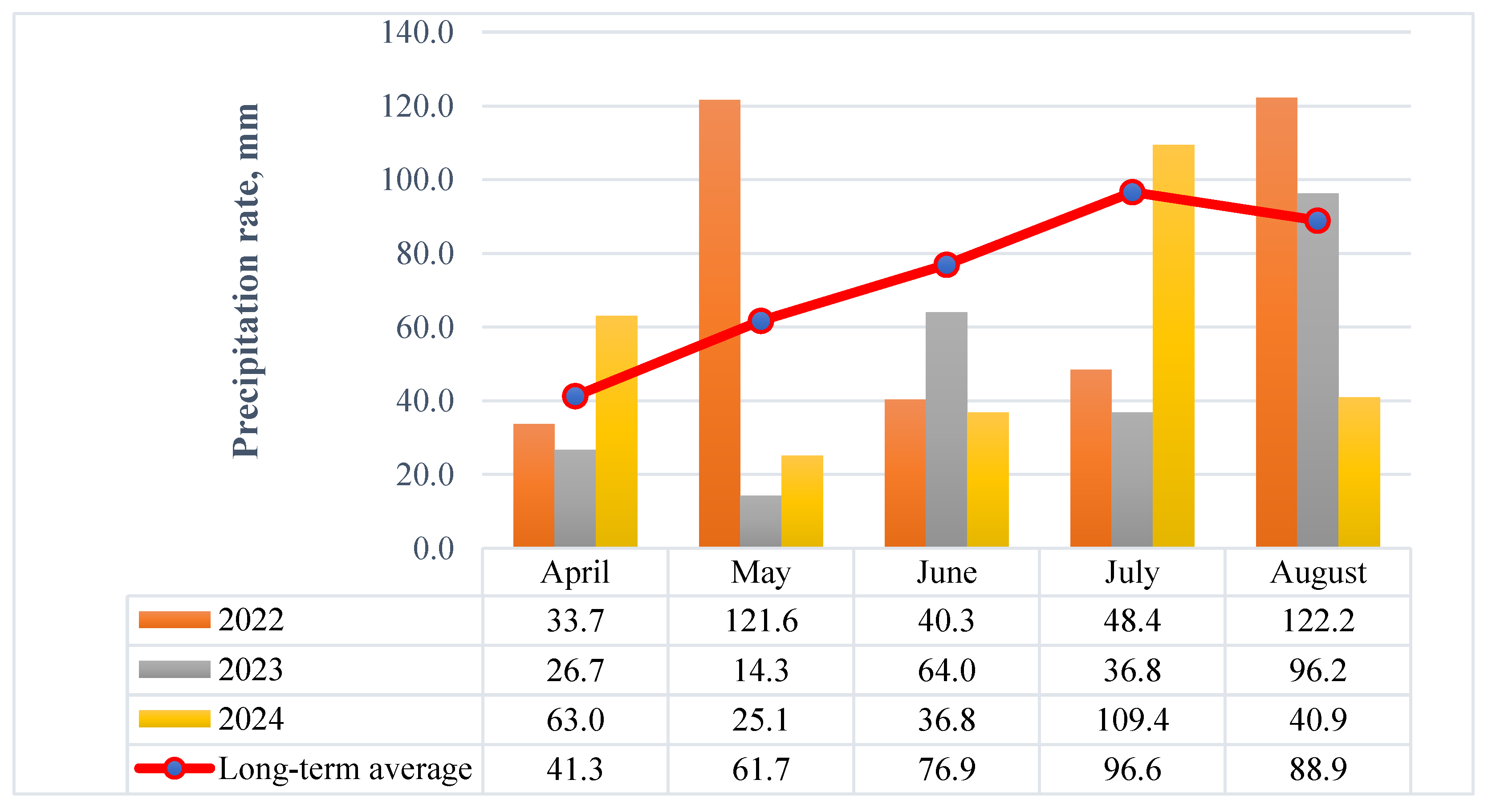

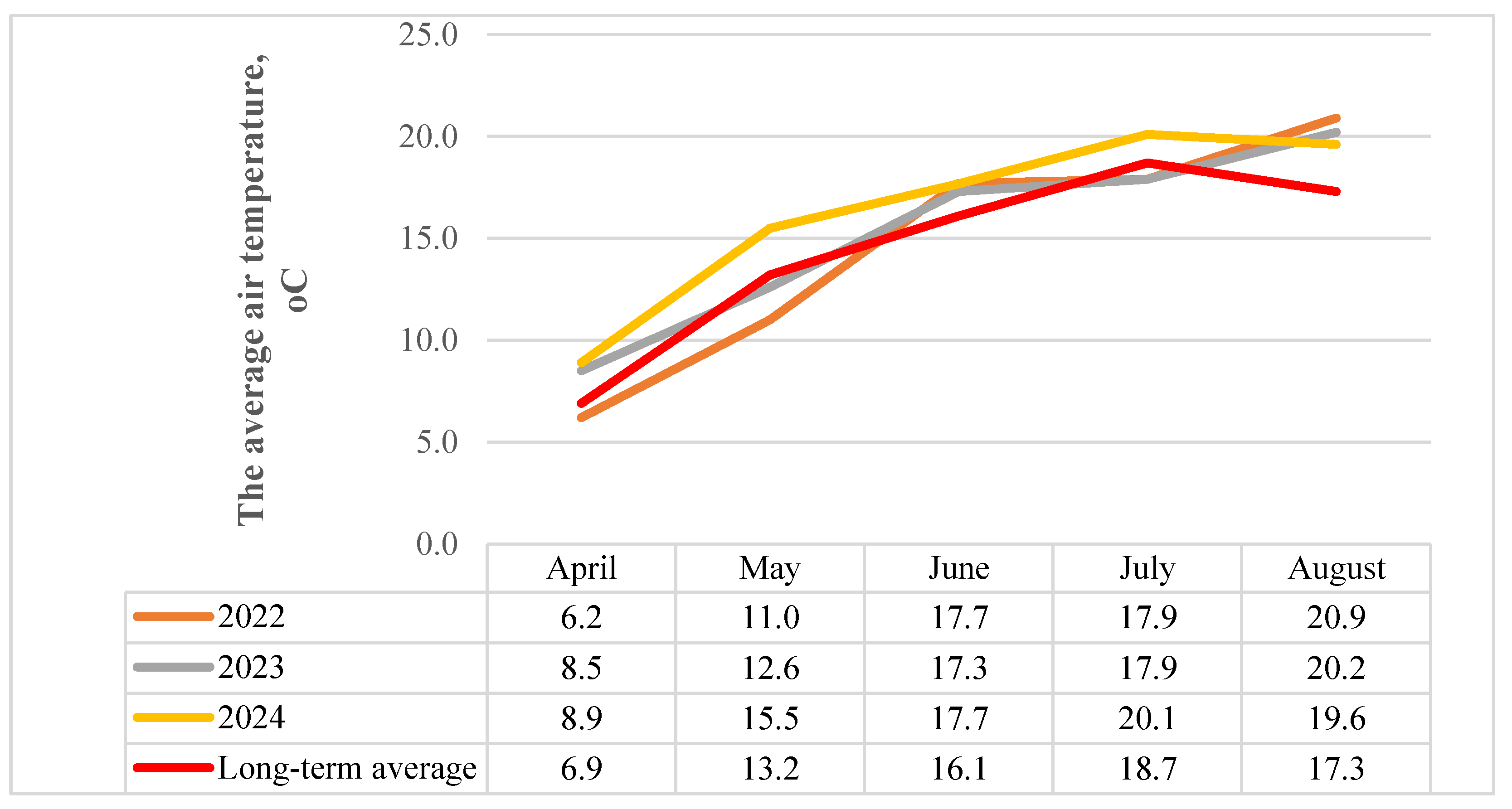

In 2022, the precipitation at the beginning (121.6 mm in May) and at the end (122.2 mm in August) of the crop vegetation period was higher (59.9 mm and 33.3 mm, respectively), and the temperature (11.0 °C in May) was lower than the long-term average (2.2 °C). The temperature in August (20.9 °C) was higher than the long-term average (3.6 °C) (

Figure 1;

Figure 2).

In 2023, precipitation at the beginning of the crop vegetation period in May was 14.3 mm lower and in August—96.2 mm higher than the long-term average (47.4 and 7.3 mm). Temperature (12.6 °C in May) was lower than the long-term average (0.6 °C), while at the end of the vegetation period in August, the temperature (20.2 °C) was higher than the long-term average (2.9 °C) (

Figure 1;

Figure 2).

In 2024, precipitation at the beginning (25.1 mm in May) and at the end (40.9 mm in August) of the crop vegetation period was lower (36.6 and 48.0 mm), and the temperature (15.5 °C in May to 20.1 °C in August) was higher than the long-term average (2.3 and 1.4).

Summarising the meteorological conditions for the study years, the 2022–2023 study years show higher precipitation in April and August and lower precipitation in May, June, and July compared to the long-term average. Over the whole study period, the most abundant precipitation was in May 2022, July 2024, and August 2022–2023 (

Figure 1;

Figure 2). In 2022–2024, temperatures were highest in June and August compared to the long-term average.

2.3. Crop Productivity and Quality Indicators

Crop germination. Germination is determined once: on the tenth day after the beginning of germination (BBCH 10). In each field, the density of seedlings was counted at ten randomly selected points in a 1-meter-long row. Seedling density was converted into pieces m-2.

Seedling density. For spring barley (number of productive stems) was determined at maturity, in 50 × 50 cm frames, at 4 locations in the field and expressed in pieces m-2.

Determination of grain yield, t ha-1. The grain yield of each field was calculated using a computerized weighing system on the combine harvester. Yields were converted at 14% moisture content into absolute clean weight of grain.

Determination of grain quality. Grain quality parameters were determined in the laboratory of the elevator in Radžiūnai, Alytus district. Methods for determining quality indicators:

Protein content: the method is given in standard LST 1593:2000. “Determination of protein content of whole barley by near-infrared spectroscopy”.

Gluten content: determined according to ISO 21415-1:2007. “Gluten content. Part 1. Determination of wet gluten by manual method”.

Sedimentation (mL)—Zeleny method (LST ISO 5529:2007) in absolute dry medium. The INFRATEC device was used to determine the sedimentation values.

Starch content (%) was determined by “INFRATEC” device;

Hectolitre mass (kg hl-1) was determined using a liter stigma device.

2.4. Comprehensive Evaluation

A comprehensive assessment of the impact of tillage technologies of varying intensities on the agroecosystem was conducted using the methodologies developed by G. Lohmann (1994) and K. U. Heyland (1998) [

13,

14]. The following studies and mathematical calculations were carried out: 1) to determine the values of different indicators; 2) to calculate the evaluation points (EP) of the different indicators expressed in different units of measurement to convert the values into a single scale. On this scale, a score of 1 represents the poorest (minimum) value, while a score of 9 reflects the best (optimum) value. Intermediate scores for each indicator were calculated using the following formula:

where Epi represents the evaluation point for a given indicator; Xi is the observed value of that indicator; Xmax and Xmin are the maximum and minimum values recorded for that indicator, respectively; 3) the converted indicator values are presented on radial grids, with the radius scaled from 1 to 9, reflecting the evaluation points; 4) the scale also shows the average value of the individual indicators—the score threshold, which is equal to 5 and distinguishes between the high and the low scores. The effectiveness of the measure will be indicated by the area bounded by the scores of all its indicators; 5) the complex evaluation index (CEI), which consists of the average of the evaluation points, the standard deviation of the evaluation points, and the standard deviation of the average of the points below the evaluation threshold, is calculated.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The research data were analyzed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) applying the F test via the SPSS Statistics I software package [

15]. The research data were processed by the method of analysis of variance using the computer program SYSTAT 12. Differences between the means of the treatment variants were evaluated using the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at confidence levels of 95.99% and 99.9% [

16]. Correlations between variables were assessed using correlation analysis, which involved calculating the correlation coefficient (r) and its statistical significance at 95% and 99% probability levels. Regression equations were also generated using the STAT program from the SELECTION software package [

16].

Standard errors of the means are represented by whiskers on the graphs. Statistically significant differences between a given treatment and the control are marked with confidence levels as follows:

* for p ≤ 0.050 > 0.010 (the differences are significant at the 95% confidence level);

** for p ≤ 0.010 > 0.001 (differences are significant at the 99% confidence level);

*** for p ≤ 0.001 (differences are significant at the 99.99% confidence level);

p > 0.050, no significant differences (differences significant at less than 95% confidence level).

3.1. Crop Productivity Indicators

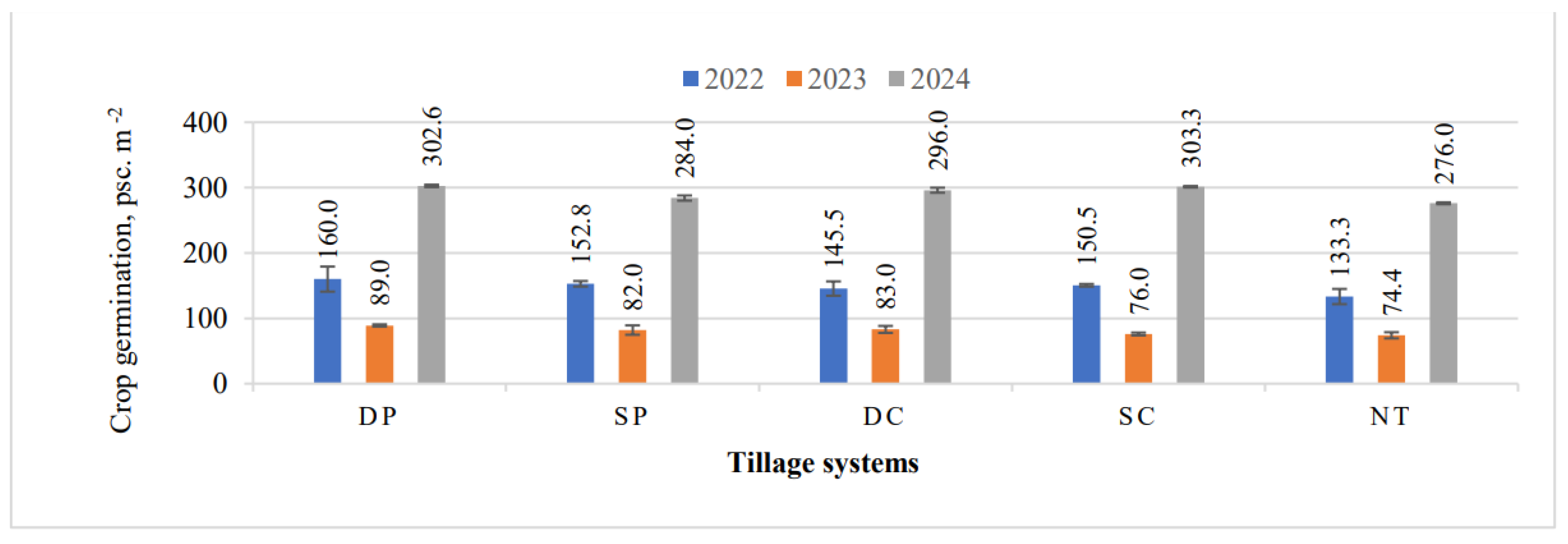

In 2022, when calculated after 10 days, the crop germination did not differ significantly between tillage systems. Reduced tillage systems (SP, DC, SC, NT) reduced crop emergence by a factor of 1.0 to 1.2 compared to deep plowing (DP) (

Figure 3).

In 2023, when calculated after ten days, reduced tillage (SP, DC, SC, NT) reduced crop emergence by a factor of 1.0 to 1.2. Conventional tillage (DP) increased crop germination.

In 2024, all reduced tillage practices (SP, DC, SC, NT) reduced spring barley crop germination by 0.44 to 8.81% compared to deep plowing (DP). The lowest spring barley germination was found in direct sowing into no-till fields (NT).

All of the reduced tillage systems reduced the germination of spring barley crops in the years 2022–2024.

In 2024, a linear average negative and statistically significant correlation was established between the germination of the spring barley crop (r = -0.543, y = 669.047 − 4.526x, P < 0.05) and the number of productive stems.

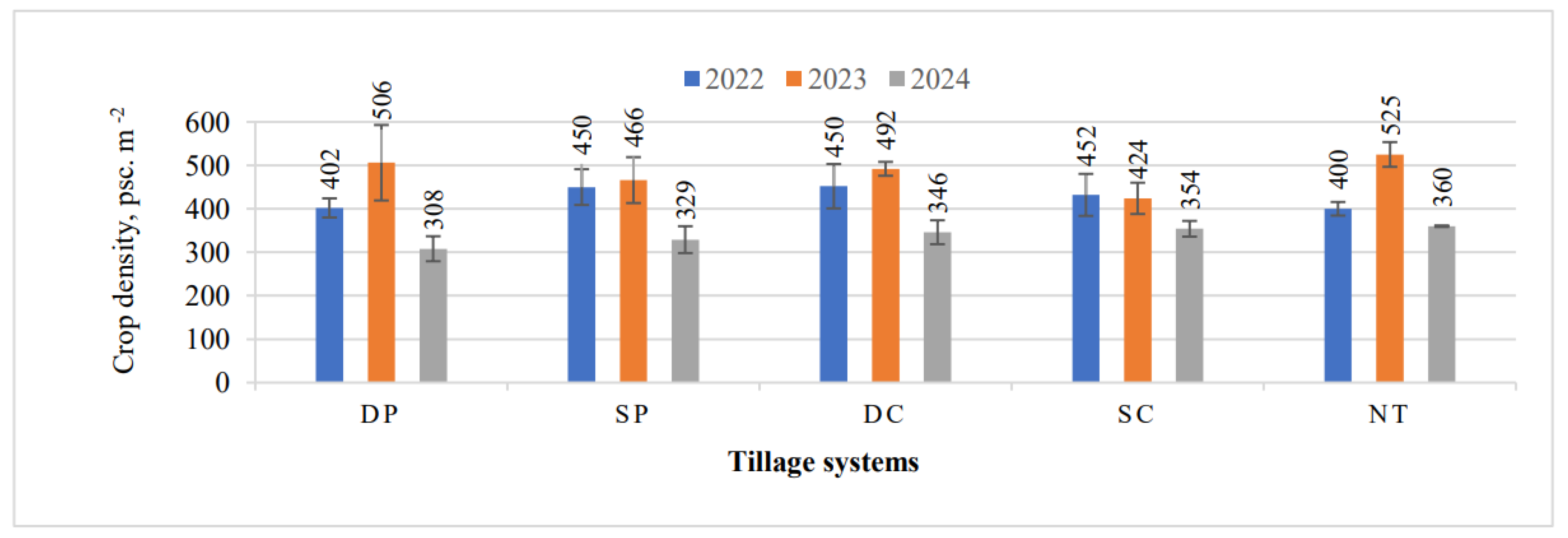

Calculations carried out in 2022 showed that there was no significant effect on crop density under the different tillage systems (

Figure 4). Reduced tillage increased crop density by up to 1.2 times compared to deep plowing. Shallow-plowed, chiseled, and disked fields showed a higher crop density of up to 1.0 times higher than in fields with conventional tillage. In the direct sowed fields (400 pieces m

-2), the crop density was very similar to that in the deep plowed fields (402 pieces m

-2).

The calculations carried out for 2023 showed that no significant effect on crop density was observed with the different tillage systems. The highest crop density was found in direct sowing fields with 525 pieces m

-2 and the lowest density was found in fields with shallow cultivation with 424 pieces m

-2. Different tillage treatments had different effects on crop density (

Figure 4).

The analysis of the number of productive stems of the spring barley crop showed that all the reduced tillage treatments increased the number of productive stems by between 6.92 and 16.88% compared to the control (DP). The highest number of productive stems of spring barley was found in the directly sown fields (NT).

In 2022 and 2024, the reduced tillage systems (SP, DC, SC) increased the density of the spring barley crop, while in 2023 it decreased it. The application of direct sowing (DS) decreased the spring barley density in 2022 and increased it in 2023–2024.

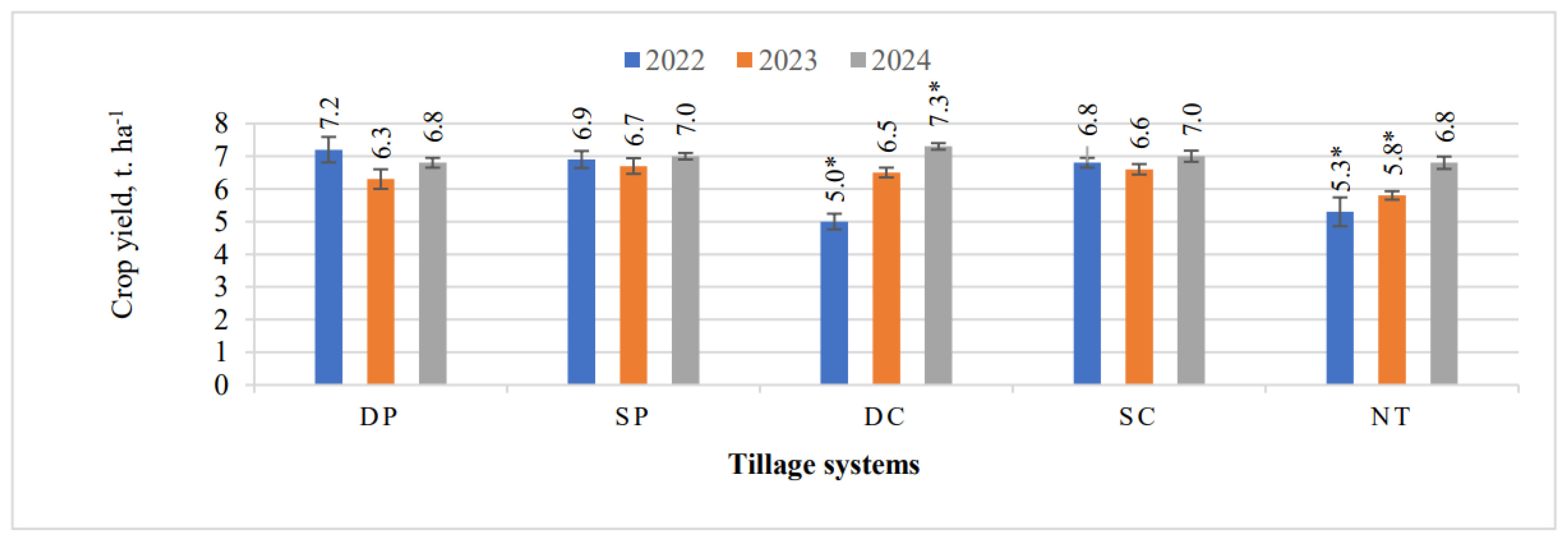

In 2022, the analysis showed that different tillage effects had a significant impact on spring barley yields (

Figure 5). Conventional tillage resulted in a maximum grain yield of 7.2 t ha

-1 for spring barley.

In all fields with reduced tillage systems, spring barley yields decreased by a factor of 1.0 to 1.4 compared to deep plowing fields. The lowest yield of 4.97 t ha-1 was found in the deep cultivation fields. Deep cultivation technology resulted in a 1.4-fold decrease in spring barley yield compared to the deep plowing technology. Direct sowing technology resulted in a yield reduction of spring barley of about 2 tons, or 1.4 times compared to deep plowing.

In 2023, the evaluation of the effect of different tillage technologies on spring barley yields shows that, in all fields, the use of reduced tillage technologies increased spring barley yields compared to deep plowing fields. Except for the direct sowing fields, where spring barley yields were significantly lower (by a factor of 1.1) compared to the deep plowing fields (

Figure 5). In 2023, the lowest spring barley grain yields were found in the deep plowing fields.

The calculation of spring barley yields for 2024 shows a trend toward higher yields with reduced tillage. However, there was a significant increase in yield of 7.69, in the deep cultivation (DC) fields compared to the control (DP). The lowest yields were found in fields where direct sowing (NT) was applied.

In 2023, a linear mediocre positive and statistically reliable correlation was established between spring barley grain yield (r = 0.507, y = 35.51+ 3.543x, P < 0.05) and hectoliter weight.

In 2024, a linear mediocre negative and statistically significant correlation was established between spring barley grain yield (r = -0.545, y = 19.29 − 1.027x, P < 0.05) and protein content.

In 2022, all the reduced tillage systems (SP, DC, SC, NT) decreased the yield of the spring barley crop. In the years 2023–2024, the tillage systems (SP, DC, SC) increased the yield of the spring barley crop. The application of direct sowing (NT) decreased the yield of spring barley in all the years studied.

3.2. Quality Indicators of Spring Barley

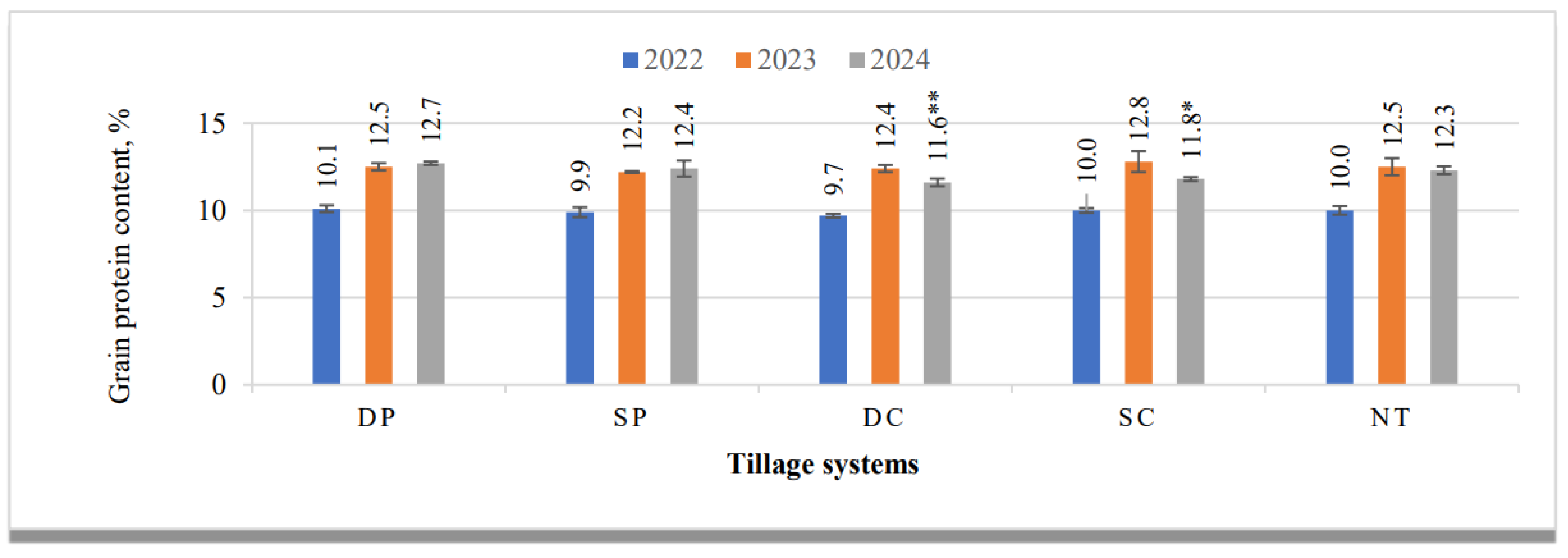

Based on the data from the 2022 survey, it can be concluded that the different tillage practices did not have a significant effect on the grain protein content. The results show that the fields with conventional tillage had the highest protein content compared to the reduced tillage systems (

Figure 6). Grain protein content in the years studied was low at 10.1%, equivalent to Grade 3 in terms of grain quality indicators.

In 2023, the study found that the grain protein content was 0.3% higher in fields with shallow cultivation compared to deep plowing (DP).

In 2024, the analysis of spring barley grain quality showed a significant decrease of 0.12 and 0.85% in protein content in the deep cultivation (DC) and shallow plowing (SP) fields compared to the deep plowing (DP) (

Figure 6).

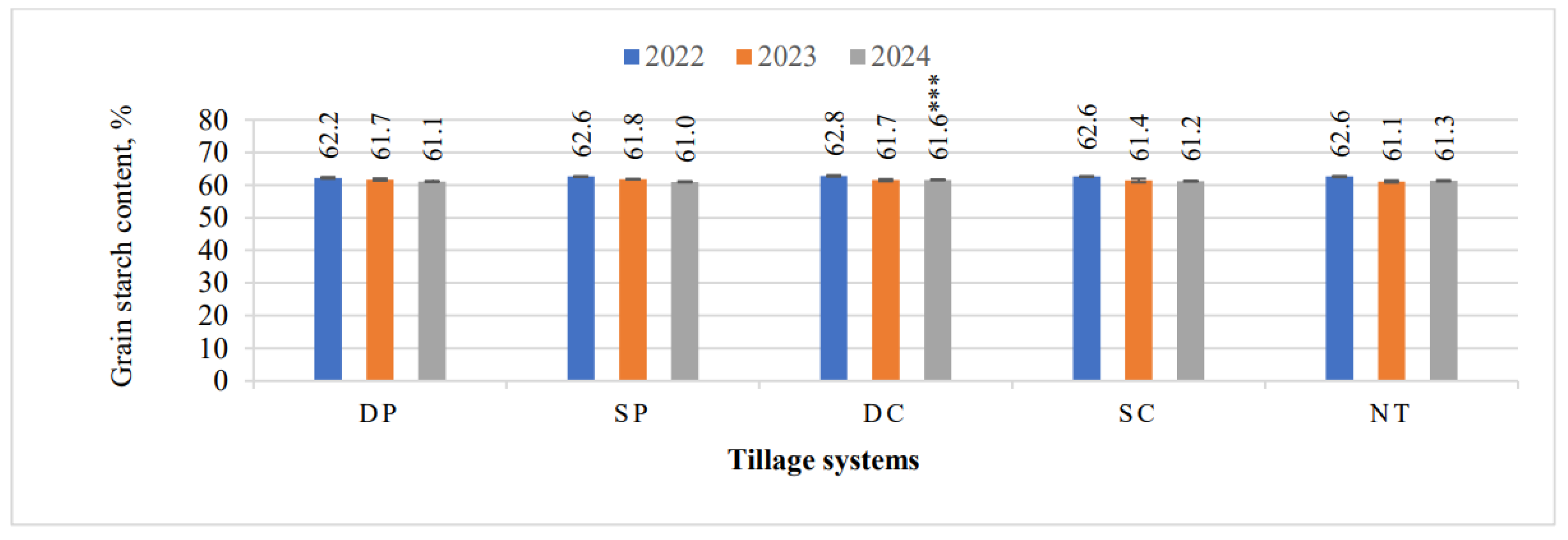

In 2022–2024, the reduced tillage systems (SP, DC, SC, NT) reduced the grain starch content of the spring barley crop, except for shallow cultivation (SC) in 2023. In 2023, when SC was applied, the starch content of the grain increased.

In 2022, a linear, mediocre negative and significant reliable correlation was established between the protein content of spring barley grains (r = -0.576, y = 67.995 − 0.549x, P < 0.01) and starch content.

In 2023, a linear, very strong negative and significant reliable correlation was established between the protein content of spring barley grains (r = -0.9, y = 72.453 − 0.876x, P < 0.01) and starch content.

In 2024, a linear strong negative and statistically reliable correlation was established between the protein content of spring barley grains (r = -0.733, y = 65.504 − 0.353x, P < 0.01) and starch content.

The starch analysis in 2022 showed that the starch content was 1.0 times higher in the fields with deep cultivation compared to the fields with conventional plowing (

Figure 7). Reduced tillage did not have a significant effect on the grain starch content.

The starch analysis in 2023 showed that the fields with shallow plowing had the highest starch content (61.8%). Other reduced tillage systems reduced the starch content by up to 1.0 times compared to conventional tillage. Summarizing the results of 2022 and 2023 it can be stated that shallow plowing (SP) increased the grain starch content.

In 2024, a significant increase of 0.55% in starch content was observed in the deep-cultivated (DC) fields compared to the control (DP) (

Figure 7).

In 2023, a linear, mediocre positive and significant reliable correlation was established between spring barley grain yield (r = 0.555, y = 55.39 + 0.957x, P < 0.05) and starch content.

In 2023, a linear, very strong positive and significant reliable correlation was established between the starch content of spring barley grains (r = 0.91, y = -192.382 + 4.082x, P < 0.01) and hectoliter weight.

In 2024, a linear mediocre positive and statistically significant correlation was established between the starch content of spring barley grains (r = 0.508, y = 58.012 + 0.461x, P < 0.05) and yield.

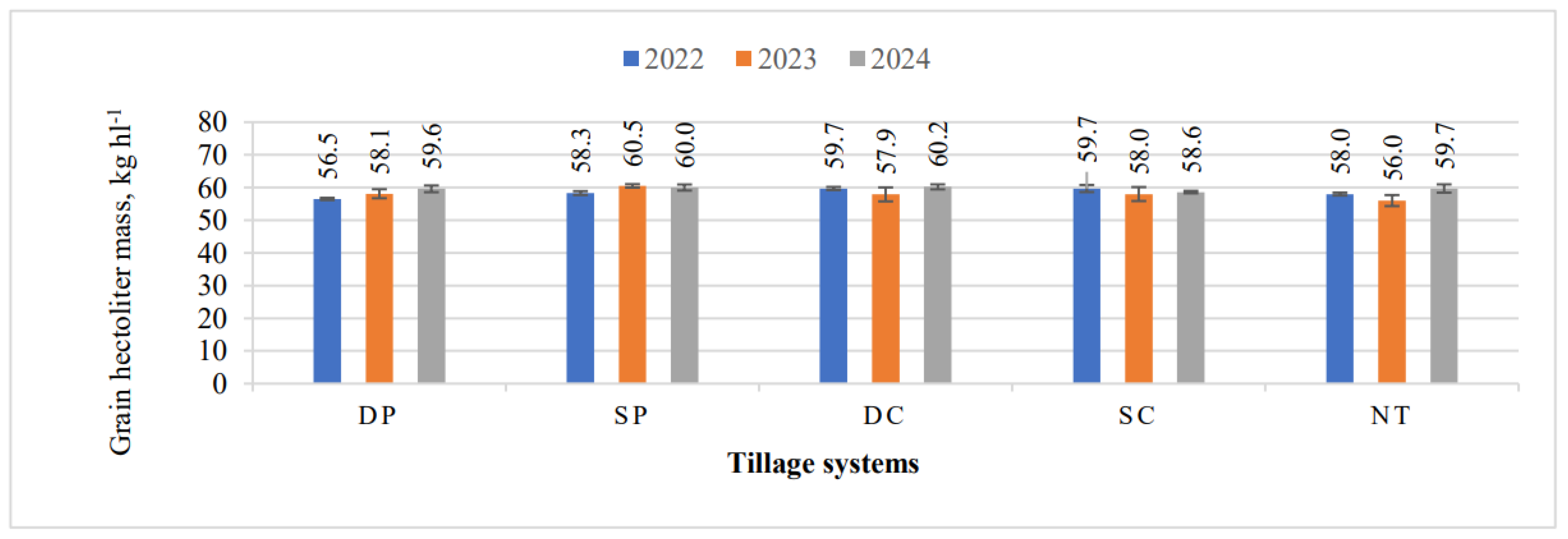

The analysis showed that no significant differences were found in 2022 in the fields with different tillage technologies. Reduced tillage increased the hectoliter mass of spring barley grain by 1.0% compared to fields with deep plowing (DP) (

Figure 8). The highest spring barley hectoliter mass was found in the deep-cultivated (DC) and shallow-cultivated (SC) fields at 59.7 kg hl

-1.

The data from 2023 showed that spring barley hectoliter mass was highest in the shallow plowed (SP) fields, with a result of up to 1.0 times higher compared to conventional plowing (DP). Barley is classified as high-quality when the hectoliter mass is 60.0 kg hl-1 and above, and poor-quality when it is lower. The hectoliter mass of spring barley grain is variable under different reduced tillage systems.

In 2024, shallow plowing (SP), deep cultivation (DC), and direct sowing (NT) resulted in a higher grain hectoliter mass of between 0.16 and 1.17% compared to deep plowed (DP) fields.

In 2022, a linear, mediocre positive and significant reliable correlation was established between spring barley grain yield (r = 0.618, y = 47.093 + 1.751x, P < 0.01) and hectoliter weight.

In 2023, a linear strong negative and significant reliable correlation was established between the protein content of spring barley grains (r = -0.794, y = 102.035 − 3.469x, P < 0.01) and hectoliter weight.

In all the years studied (2022–2024), shallow plowing showed an increase in spring barley grain hectoliter mass. All other reduced tillage systems used did not show clear trends.

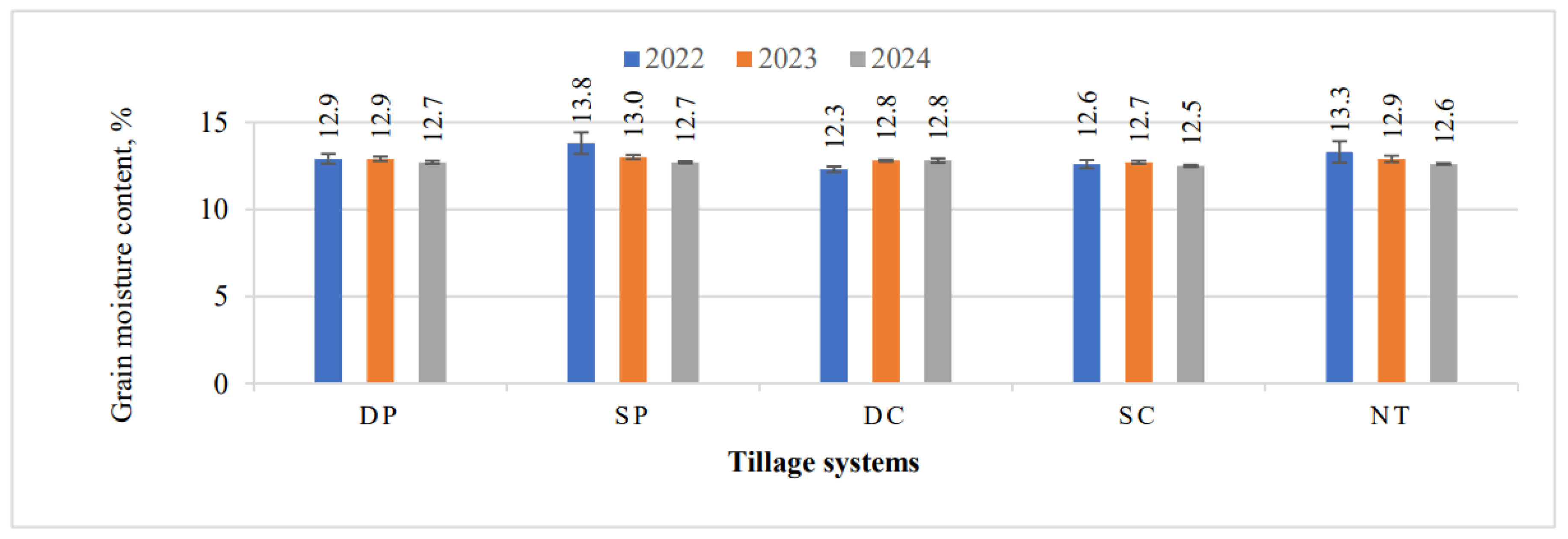

In 2022, no significant differences in spring barley grain moisture content were detected in the fields with different tillage systems (

Figure 9). Shallow plowing (SP) fields maintained the highest grain moisture content (13.8%). In all the fields studied, the grain moisture content in 2022 was good, the grain was storable and dry.

No significant differences in the moisture content of spring barley grain were found between the different tillage systems in the 2023–2024 period. In 2023, the wettest grain remained in the shallow plowed fields. In the fields, the grain moisture content did not exceed 13.0%, indicating that the production was suitable for storage, a trend that was also evident in 2024.

In the years 2022–2024, shallow plowing (SP) increased the yield of spring barley grain, while shallow cultivation (SC) decreased it. All other conservation tillage systems (DC, NT) did not show consistent trends.

In summary, in 2022, shallow plowing (SP), deep cultivation (DC) and shallow cultivation (SC) increased the starch content and the hectoliter mass of spring barley but decreased the germination and yield of the crop and the grain‘s protein content. In 2023, deep cultivation (DC) increased grain yield. In 2024, the analysis of spring barley crop germination showed that the fields under direct sowing (NT) had the lowest emergence compared to the fields under deep plowing (DP). However, in the direct sowing fields (NT), the number of productive stems was higher compared to the fields with conventional tillage (DP). In the fields with deep cultivation (DC), the highest yields were found but the protein content was lower compared to deep plowing (DP).

In 2022, a linear, mediocre negative and significant reliable correlation was established between spring barley grain moisture content (r = -0.611, y = 75.465 − 1.311x, P < 0.01) and hectoliter weight.

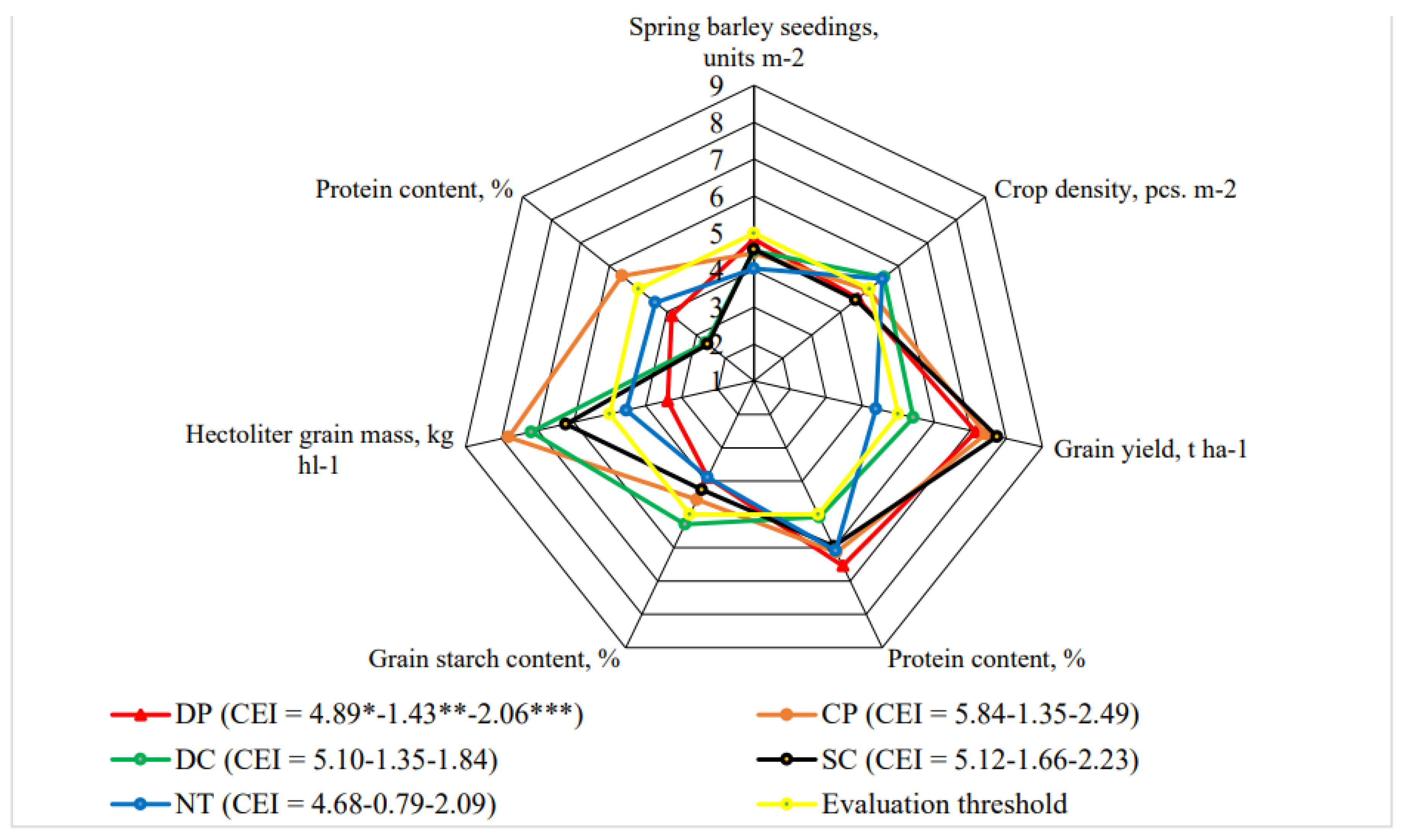

3.3. Comprehensive Evaluation of the Long-Term Effects of Tillage Technologies on the Agroecosystem

The most important objective of tillage is to minimize the intensive technological impact on the soil and crops and to create the right conditions for them to grow, to ensure a steady renewal of the soil‘s productivity, and to maintain cost-effective production. Continuous deep plowing adversely affects many soil properties and promotes compaction of the subsoil [

17]. Each tillage technology has its advantages and disadvantages. Deep plowing has a high probability of producing higher yields. However, due to the low productivity of tillage operations and the need for high-powered implements, these tillage technologies are the most expensive. In addition, deep plowing has negative impacts on the environment, soil, and biodiversity [

18]. It is very difficult to decide which indicator has a greater or lesser impact on the crop agroecosystem. An integrated assessment system would solve this problem.

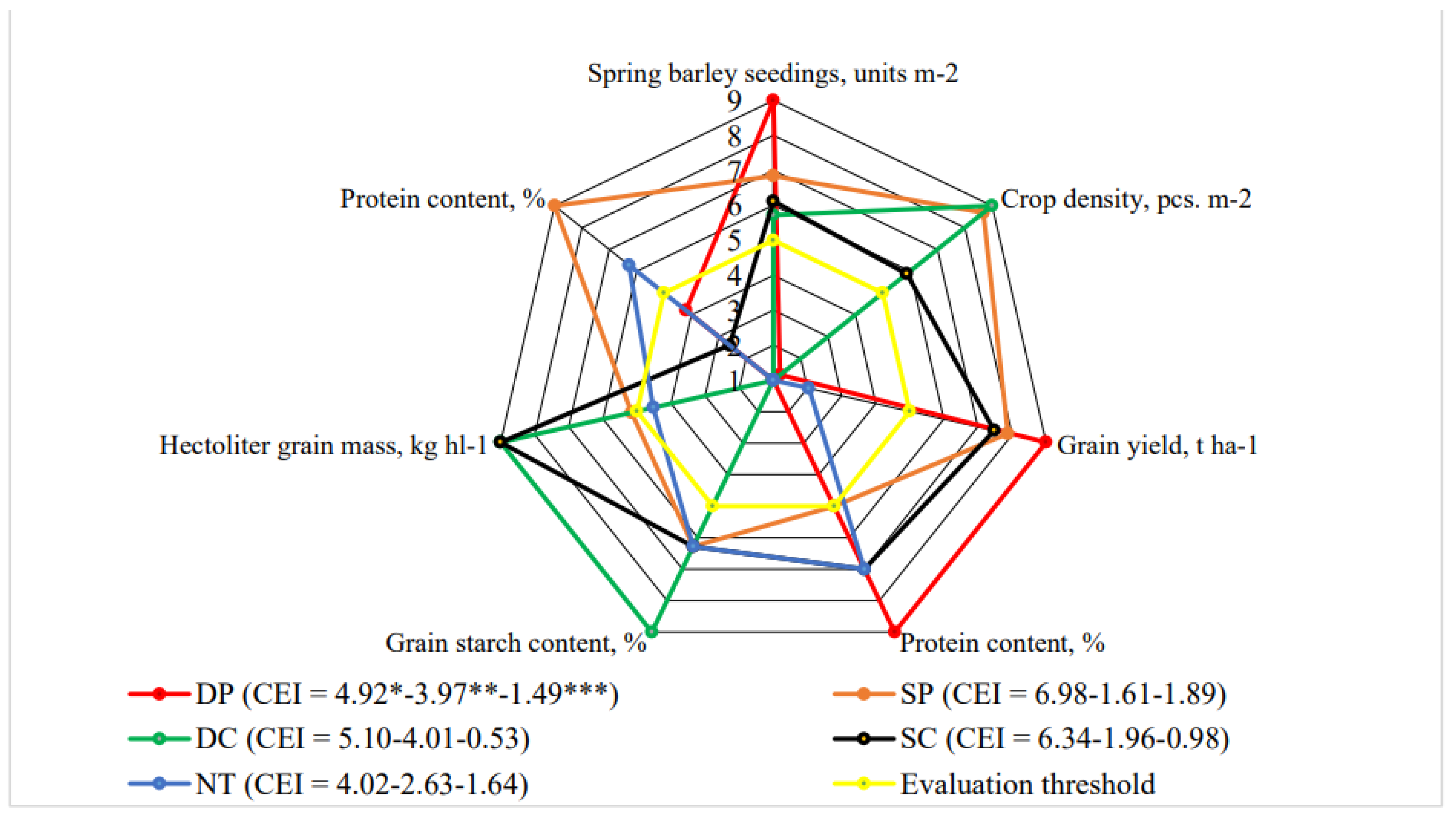

The results of the integrated assessment of the long-term impact of tillage technologies on the agroecosystem, taking into account 7 indicators, are presented in the figures below (

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and Figure 14).

In 2022, the evaluation of the indicators studied in the spring barley crop showed that the shallow plowing (SP) tillage technique was superior to the other techniques used, as all the indicators studied were above the assessment threshold (5 points) (

Figure 10). Deep cultivation (DC) and shallow cultivation (SC) technologies had a more positive impact on the hectoliter mass of spring barley grain, with the highest scores obtained (9 points).

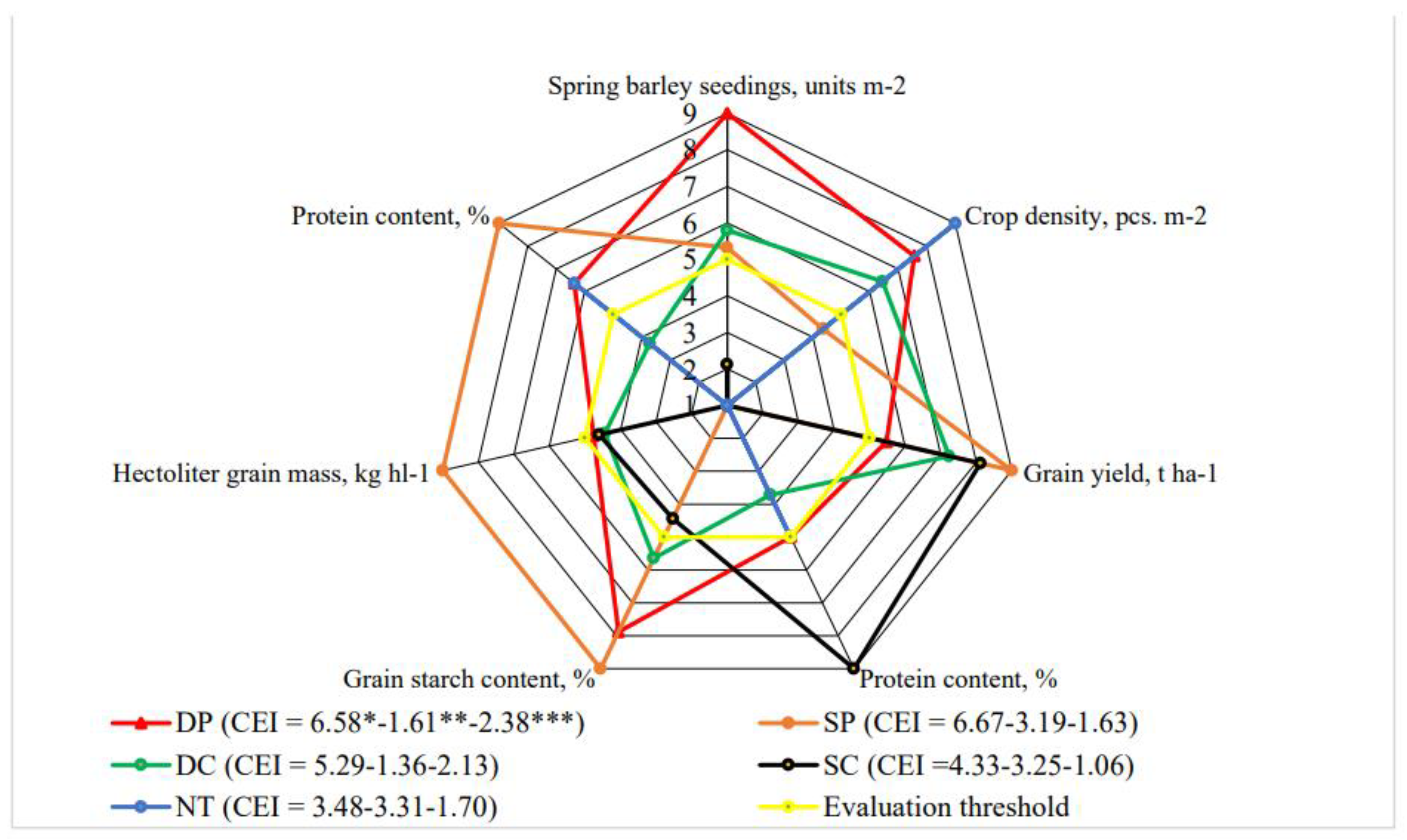

In 2023, the deep plowing (DP) technology scored higher or close to the assessment threshold (4.76) (

Figure 11). For spring barley, a hectoliter mass of grain below the assessment threshold of 4.76 points was found for deep plowing technology.

Shallow plowing (SP) technology increased spring barley grain yield, starch content, protein content, and hectoliter mass, with a score threshold of 9 points.

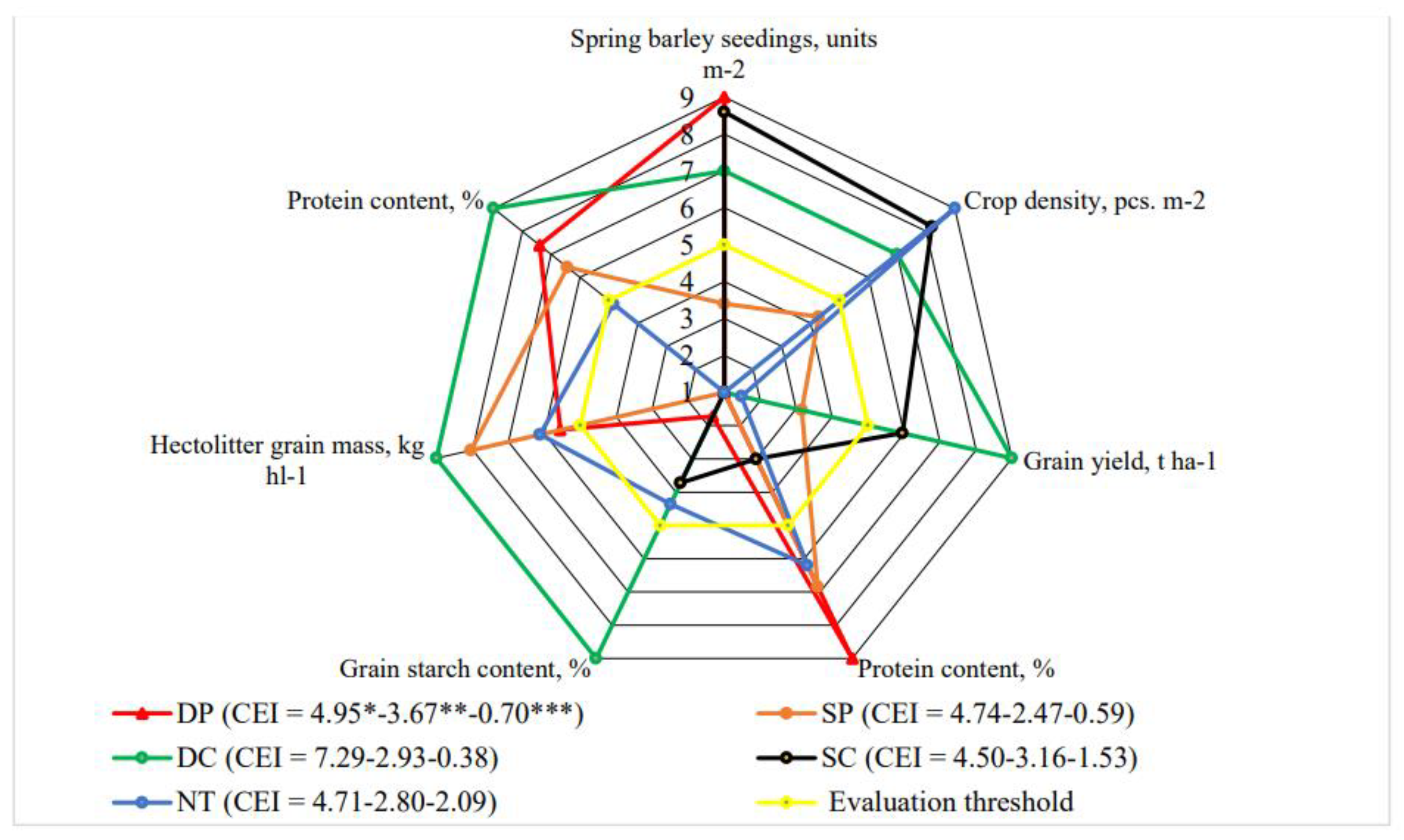

In 2024, different tillage technologies and the evaluation of the indicators under study resulted in different evaluation scores (

Figure 12).

When the impact of the technologies on the different indicators studied was assessed, no-tillage technology increased the scores to bring all the indicators studied above the assessment threshold. The deep cultivation (DC) technology increased spring barley grain yield, starch content, protein content, and hectoliter mass, the evaluation threshold increased to 9 points.

The calculated complex evaluation indices and areas limited by assessment scores for 2022–2024 showed that the impact of shallow cultivation (SC) technology on the agroecosystem was greater than that of other comparative technologies (

Figure 13).

Summary. The calculated complex evaluation indices (CEI), consisting of the average, standard deviation and CEI of all evaluation points (EP) not exceeding the evaluation threshold, standard deviation, and areas limited by EP, show that the positive impact of reduced tillage technologies on the agroecosystem is greater than that of deep plowing technologies.

Figure 1.

Average precipitation at Kaunas Meteorological Station in 2022–2024.

Figure 1.

Average precipitation at Kaunas Meteorological Station in 2022–2024.

Figure 2.

Average air temperature at Kaunas Meteorological Station in 2022–2024.

Figure 2.

Average air temperature at Kaunas Meteorological Station in 2022–2024.

Figure 3.

Spring barley crop germination after 10 days, under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. No significant differences at P > 0.05. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 3.

Spring barley crop germination after 10 days, under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. No significant differences at P > 0.05. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 4.

Spring barley crop density under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. No significant differences at P > 0.05. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 4.

Spring barley crop density under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. No significant differences at P > 0.05. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 5.

Spring barley crop yield under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. Differences significant at *—P ≤ 0.05 > 0.01. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 5.

Spring barley crop yield under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. Differences significant at *—P ≤ 0.05 > 0.01. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 6.

Protein content of spring barley grains under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. Differences significant at *—P ≤ 0.05 > 0.01, **—P ≤ 0.01 > 0.001. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 6.

Protein content of spring barley grains under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. Differences significant at *—P ≤ 0.05 > 0.01, **—P ≤ 0.01 > 0.001. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 7.

Starch content of spring barley grains under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. Differences significant at ***—P ≤ 0.001. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 7.

Starch content of spring barley grains under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. Differences significant at ***—P ≤ 0.001. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 8.

Hectoliter mass of spring barley grain under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. No significant differences at P > 0.05. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 8.

Hectoliter mass of spring barley grain under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. No significant differences at P > 0.05. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 9.

Spring barley grain moisture content under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP–Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. No significant differences at P > 0.05. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 9.

Spring barley grain moisture content under different tillage systems, 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP–Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. No significant differences at P > 0.05. Whiskers indicate standard errors of the means.

Figure 10.

Complex assessment of long-term effects of tillage technologies 2022. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. CEI—complex evaluation indices, *—an average of evaluation points (EP), **—standard deviation of EP, ***—standard deviation of the average of the evaluation points below the evaluation threshold.

Figure 10.

Complex assessment of long-term effects of tillage technologies 2022. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. CEI—complex evaluation indices, *—an average of evaluation points (EP), **—standard deviation of EP, ***—standard deviation of the average of the evaluation points below the evaluation threshold.

Figure 11.

Complex assessment of long-term effects of tillage technologies 2023. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. CEI—complex evaluation indices, *—an average of evaluation points (EP), **—standard deviation of EP, ***—standard deviation of the average of the evaluation points below the evaluation threshold.

Figure 11.

Complex assessment of long-term effects of tillage technologies 2023. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. CEI—complex evaluation indices, *—an average of evaluation points (EP), **—standard deviation of EP, ***—standard deviation of the average of the evaluation points below the evaluation threshold.

Figure 12.

Complex assessment of long-term effects of tillage technologies 2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. CEI—complex evaluation indices, *—an average of evaluation points (EP), **—standard deviation of EP, ***—standard deviation of the average of the evaluation points below the evaluation threshold.

Figure 12.

Complex assessment of long-term effects of tillage technologies 2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. CEI—complex evaluation indices, *—an average of evaluation points (EP), **—standard deviation of EP, ***—standard deviation of the average of the evaluation points below the evaluation threshold.

Figure 13.

Complex assessment of long-term effects of tillage technologies 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. CEI—complex evaluation indices, *—an average of evaluation points (EP), **—standard deviation of EP, ***—standard deviation of the average of the evaluation points below the evaluation threshold.

Figure 13.

Complex assessment of long-term effects of tillage technologies 2022–2024. Note: DP—Deep plowing, SP—Shallow plowing; DC—Deep cultivation, chiseling, SC—Shallow cultivation-disking, NT—No-tillage. CEI—complex evaluation indices, *—an average of evaluation points (EP), **—standard deviation of EP, ***—standard deviation of the average of the evaluation points below the evaluation threshold.