1. Introduction

Over the past five years, malaria cases have increased across the African continent, with an estimated 265 million cases reported in 2023 [

1]. Despite significant efforts to reduce and eliminate malaria, many countries continue to struggle with the burden of this disease [

2]. Current control strategies primarily rely on the use of insecticides to target the mosquito vector and antimalarial drugs to combat the parasite [

3,

4]. However, the effectiveness of these measures is compromised by the emergence and spread of insecticide and antimalarial drug resistance [

5,

6]. This growing resistance threatens to undermine decades of progress in malaria control and highlights the urgent need for innovative solutions. In response to this challenge, the World Health Organization (WHO) emphasized the importance of developing and deploying new tools and strategies to combat malaria, sustain progress, and ultimately achieve malaria elimination [

7].

Significant advances in biotechnology have opened new avenues for combating malaria, including genetic-based vector control methods such as genetically engineered mosquitoes (GEM) [

8]. These strategies are categorized into population suppression, which aims to reduce or eliminate vector populations, and population modification, which employs antiparasitic effector molecules to disrupt pathogen transmission [

9]. The University of California Malaria Initiative (UCMI) has developed a GEM utilizing a Cas9/gRNA-based gene-drive system which inserts two genes encoding antibodies that target the parasite, rendering the mosquito incapable of transmitting malaria [

9,

10]. Small cage trials and modelling show that the introduction of GEM could reduce malaria incidence by over 90% within three months, indicating that this technology shows promise for large scale field trials [

11].

Despite its promise, scaling this technology for real-world application requires extensive testing to evaluate potential ecological impacts and guide decision making [

12]. Direct and indirect interactions between GEM and non-target organisms are highly probable. Therefore, biodiversity and community structure in aquatic ecosystems where mosquito larvae develop should be assessed [

10,

13]. These evaluations are essential components of the environmental risk assessment (ERA) framework, ensuring GEM introduction aligns with ecological safety and sustainability while addressing potential impacts on sensitive environments [

10,

14,

15,

16].

The islands of São Tomé and Príncipe (STP) in the Gulf of Guinea have been identified as ideal candidates for the first deployment of a gene-drive GEM for malaria control [

17]. Features such as small size, reduced biological complexity, and the presence of a single malaria vector species,

Anopheles coluzzii, make the islands well-suited for this approach [

17]. Furthermore, genetic studies have confirmed that

An. coluzzii on STP are genetically isolated from mainland African populations, ensuring contained application of this technology and minimizing confounding factors such as mosquito migration [

17,

18,

19].

São Tomé and Príncipe have experienced rising malaria cases in recent years [

1]. The tropical rainforest climate, characterized by high humidity, warm temperatures, and year-round rainfall, supports abundant and diverse mosquito populations [

20]. Additionally, the islands’ biogeography and structure provide aquatic habitats suitable for mosquito breeding [

21,

22,

23]. STP is home to a rich endemic biodiversity, which is well-documented for mammals, birds and amphibians, but less so for arthropods and, particularly, aquatic macroinvertebrates [

24]. Aquatic biodiversity plays a vital role in ecosystem function, including nutrient cycling, food web stability, and biological control of pest and disease vector species [

25,

26]. The larval and pupal stages of

Anopheles mosquitoes share aquatic habitats and interact closely with other organisms in the ecosystem and serve as prey for a diverse variety of predators [

15].

The aim of this study was to assess the biological diversity of aquatic macroinvertebrates inhabiting breeding sites of An. coluzzii in São Tomé and Príncipe. The specific objectives were to: i) identify and quantify the aquatic biodiversity sharing larval habitats with An. coluzzii; ii) evaluate how aquatic macroinvertebrate biodiversity differs between temporary and permanent breeding sites, between wet and dry seasons, and between years, and iii) identify and quantify potential larval predators of An. coluzzii. The findings will provide valuable insights into the composition and dynamics of aquatic macroinvertebrate communities on the islands, contributing to our understanding of potential interactions with the main malaria vector An. coluzzii. This catalog of non-target organisms will serve as a standard against which post-GEM non-target surveys can be compared. Dramatic changes can be explored to determine if they may be driven by the presence of the GEM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study was performed on São Tomé and Príncipe islands, located in the Gulf of Guinea, approximately 250 km off the coast of Gabon, central Africa (

Figure 1a). With a total area of 857 km

2 and 139 km

2, respectively, the islands are marked by mountain ranges and steep slopes, with flatter areas in the north and northeast. Both islands have numerous coastal streams and mangroves [

20]. With an equatorial climate, the islands experience a short dry season (June to September) and an extended wet season (October to May).

A total of five localities were selected and sampled during the dry and wet seasons of 2022 to 2023. Four localities were on the main island, São Tomé, and one on the smaller island, Príncipe (

Figure 1). The selected localities are all urban with known

An. coluzzii breeding sites. A wide geographical spread of localities was included to capture spatial variation in aquatic community diversity. In São Tomé, collections were conducted in Santa Catarina (STC), Bobo Forro (BFO), Ribeira Afonso (RBA), and Vila Malanza (MAL). In Príncipe, collections were carried out in Lenta Pia (PIA) (

Figure 1;

Table S1).

2.2. Breeding Site Identification and Characterization

One permanent and one temporary breeding site was identified for each area by a local entomologist from the National Center of Endemic Diseases (CNE) (

Figure S1). All breeding sites were screened before initiating the study to confirm the presence of

An. coluzzii immature stages and only those sites positive for

An. coluzzii were selected. Permanent sites were defined as breeding sites where water remained continuously or for a minimum of 3 months after the end of the wet season, allowing mosquitoes to reproduce throughout the year. Temporary sites were defined as breeding sites where water remained for approximately 1 month after the wet season ended. All selected breeding sites were georeferenced using a Garmin GPSMAP

® 64SX GPS device (Garmin, Olathe, USA).

Each site was characterized as one of the following habitat types: stream, ditch, swamp, roadside puddle, small puddle, or artificial hole (used to store water during construction). Human-made breeding sites are classified according to their well-defined boundaries and usage reports in construction, while natural sites have irregular edges. Conditions such as water current, light intensity, turbidity, and the presence or absence of vegetation were visually estimated. The water current was visually characterized as slow, fluctuating, or still. Light intensity was visually categorized into light and shadow [

25,

26]. All visual classifications were performed by the same person (MJC) to maintain consistency.

2.3. Sampling Aquatic Biodiversity

Sampling was performed between March 2022 and June 2023. Collections were carried out twice in the dry season and twice in the wet season for a total of four sampling events per site over the course of the study. If the breeding site was found dry, only the status, dry, was recorded.

For each water body, three edges were demarcated with 1 m flagging tape indicating each sweep. With a 30 cm D-frame kick net, one sweep was performed below the surface along the 1 m length of each of the three edges. The sample collected was poured into a tray with clean tap water and all organisms were collected with a plastic pipette and forceps. Organisms were stored in 5 ml tubes filled with 80% ethanol and transferred to the UCMI Molecular Biology Laboratory at the University of São Tomé and Príncipe (USTP) to be identified to the lowest taxonomic level possible. The samples were then sent to the University of California, Davis, where identifications were confirmed. Morphological identification of macroinvertebrates was performed using taxonomic keys and scientific literature [

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The identification of potential larval predators was carried out based on scientific literature [

23,

33]. The samples were subsequentially curated following standard entomological procedures and deposited at the Bohart Museum of Entomology, University of California, Davis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses and plots drawn were performed using Rstudio software (R version 4.4.1) [

34] and Microsoft Excel. Data from both islands were combined due to differences in sample size (four localities on São Tomé Island and one locality on Príncipe Island). The following packages were used for the analysis:

vegan_2.6-8 [

35],

car_3.1-3 [

36], and

lmertest_3.1-3 [

37]. Shannon-Wiener (

H’), Simpson’s diversity (

D), and Pielou’s equitability diversity (

J′) indices were calculated using the following formulas [

38]:

Shannon-Wiener Index (

H’):

Simpson

’s Index of Diversity (

D):

Pielou’s Equitability Diversity

(J’):

Distribution of the data was assessed using Shapiro-Wilk test, Q-Q plots and Levene’s tests. When assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were violated, non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis rank sum tests were applied as an alternative. For each index, a Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) was used to determine how breeding site type (permanent or temporary), season (wet or dry) and year (2022 and 2023) affected diversity. Two GLMMs were used to assess the variation in richness (number of families) and abundance (number of individuals) between breeding site types, seasons and years. The data followed a Poisson distribution which was used as the distribution family in the model. For all models, site was included as a random effect to account for repeated measures due to resampling of the same sites. All analyses were performed with taxonomic standardization at the family level.

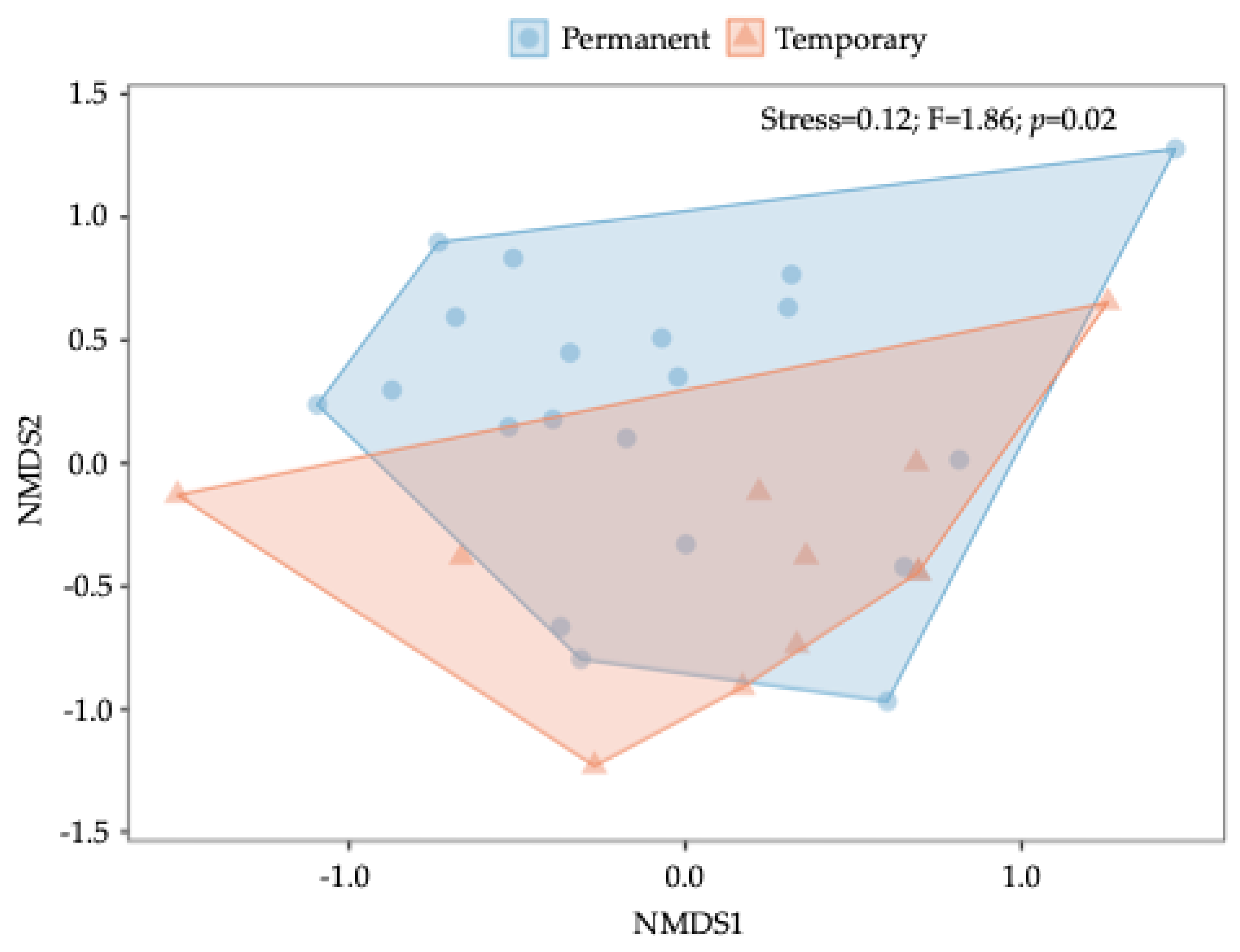

To explore temporal (wet or dry season) patterns and differences between temporary and permanent breeding sites and years in macroinvertebrate assemblages, a Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) analysis was performed. NMDS was used to visualize differences in community composition based on presence/absence data at family level, considering breeding site type, season and year as group variables, helping to identify patterns of similarity across variables. A PERMANOVA analysis was performed using the

adonis2 function from the

vegan package in R [

35] to test the null hypothesis of no difference in assemblage structure across breeding site types, season and years. Jaccard dissimilarity was used as the distance metric, with a maximum of 100 iterations to obtain the minimum stress value.

3. Results

3.1. Breeding Site Identification and Characterization

Ten breeding sites were identified and characterized, comprising one permanent and one temporary site in each of the five localities (

Table 1). Natural habitats predominated, with only one of the ten sites being manmade. Swamps were the most common habitat type. All breeding sites were exposed to direct sunlight, most featuring clear and still water. Natural vegetation was present in 70% of the sites.

3.2. Aquatic Macroinvertebrates Assemblages

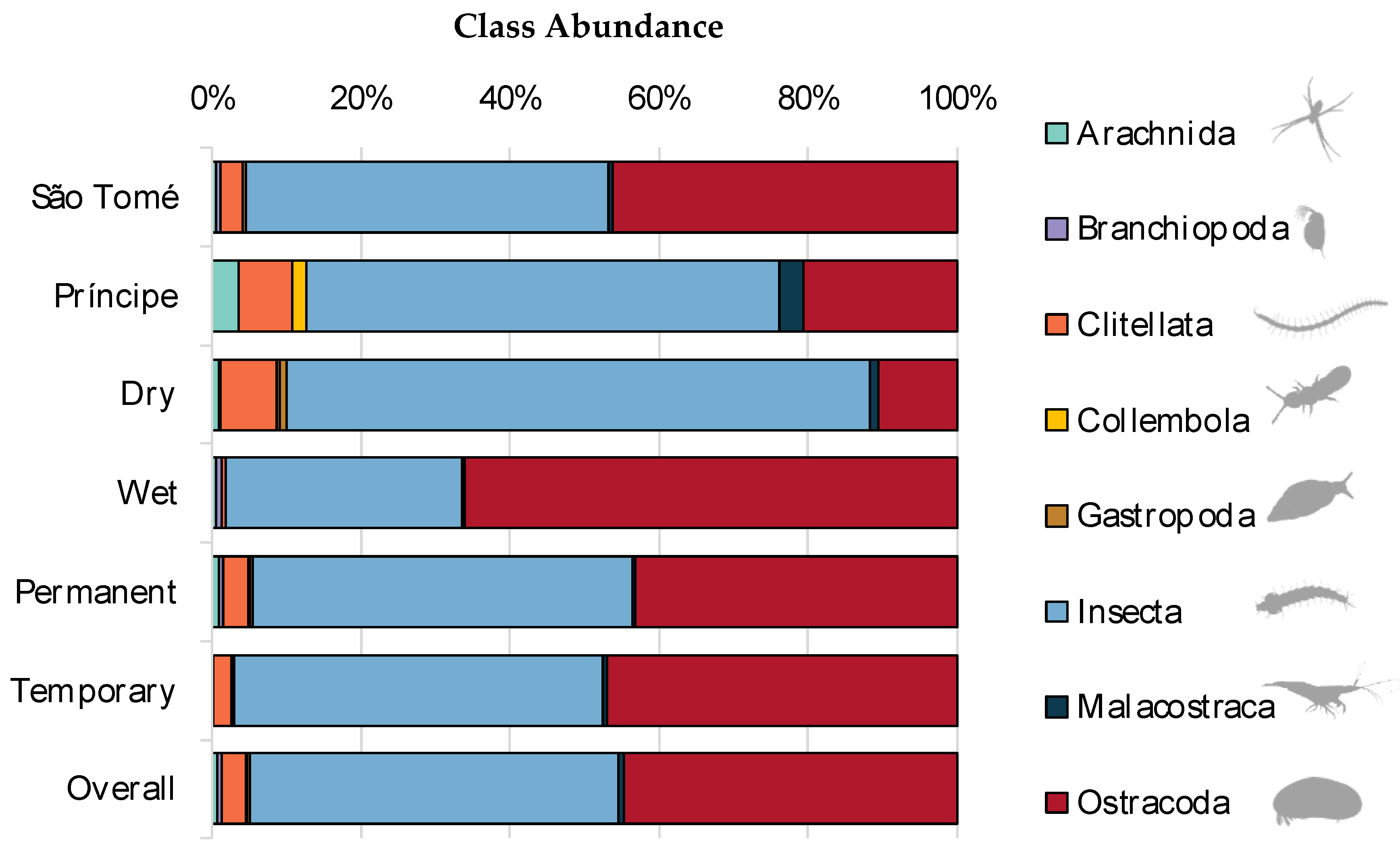

A total of 5,208 aquatic macroinvertebrates belonging to eight classes, 15 orders and 51 families were sampled across all localities in São Tomé and Príncipe. Insecta was the predominant class with the highest diversity (49.6% of individuals, consisting of 30 families), Ostracoda was the next most abundant class (44.7% of individuals, consisting of three families), followed by Clitellata (3.2% of individuals, consisting of one family) (

Figure 2).

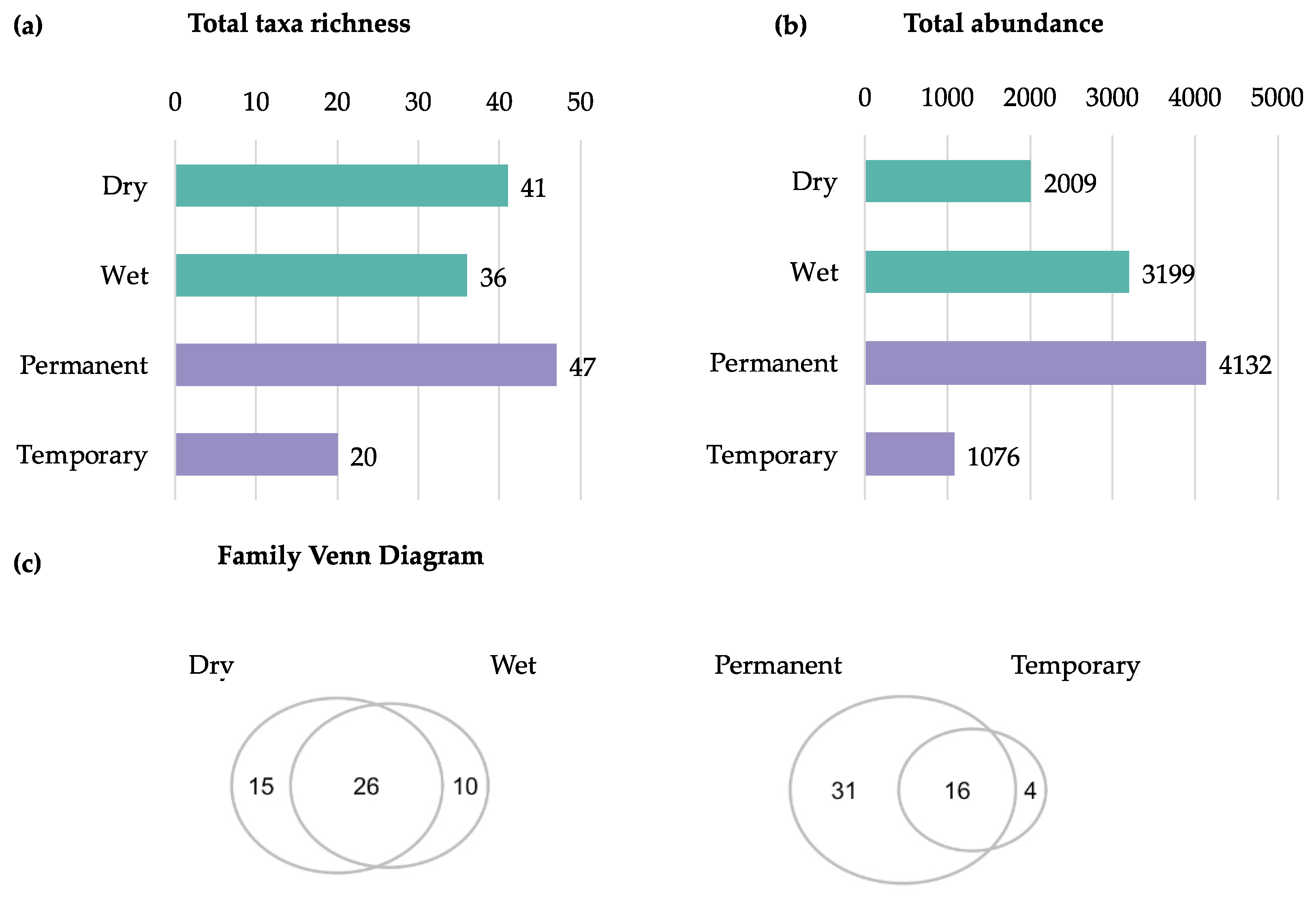

3.3. Assemblages According to Breeding Site Type and Season

Total abundance and family richness for breeding site type and season are given in

Figure 3. The family with the highest relative abundance in both permanent and temporary breeding sites was Cyprididae (Ostracoda: Podocopida) with respective percentages of 41.9% and 50.3%. This family was followed by Culicidae (Insecta: Diptera) in permanent breeding sites (33.1%), and Chironomidae (Insecta: Diptera) in temporary breeding sites (16.2%). In the wet season, the family Cyprididae (Ostracoda: Podocopida) had the highest relative abundance percentage of 66.0%, followed by Micronectidae (Insecta: Hemiptera) with 7.8%. The dry season results showed the families Culicidae (Insecta: Diptera) followed by Cyprididae (Ostracoda: Podocopida) with the respective percentages of 65.6% and 7.9%. Some families were exclusively found in only one breeding site type or season which we summarize in

Figure 3c (

Table S2).

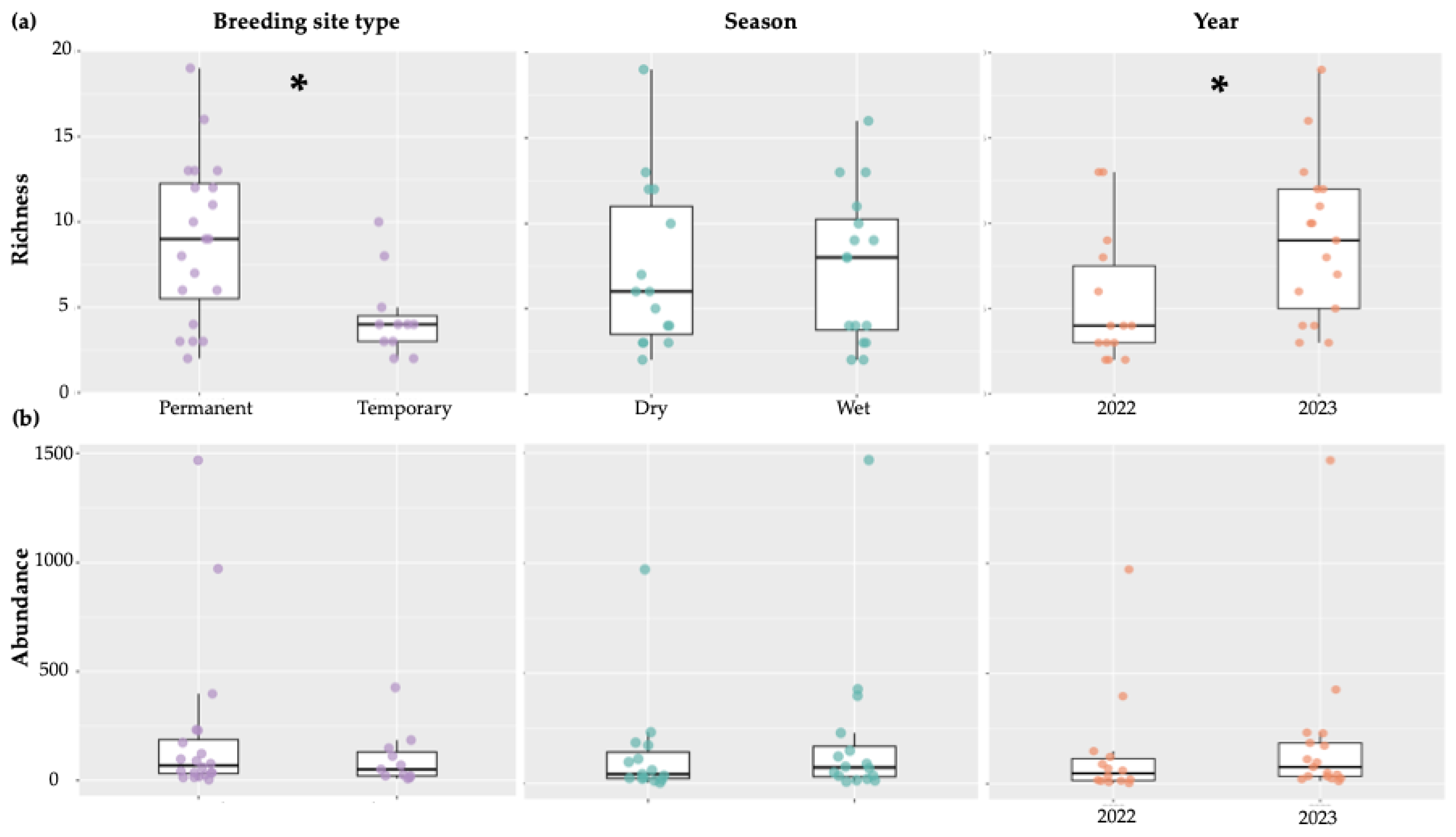

Not surprisingly, overall, family richness was significantly higher in permanent compared to temporary breeding sites (Estimate=-4.51, t=-2.89,

p=0.01), while no significant differences were detected between the dry and wet seasons (Estimate=0.36, t=0.24,

p=0.81) (

Figure 4a). Abundance did not significantly differ between permanent and temporary breeding sites (Estimate=-110.53, t=-1.02,

p=0.32) or seasons (Estimate=71.66, t=0.70,

p=0.49) (

Figure 4b). As there were more collections made on São Tomé (four localities) than Príncipe (one locality) we did not make statistical comparisons between the islands. To assess interannual variation showed significantly higher richness in 2023 than 2022 (

p=0.002). This was supported by a Kruskal–Wallis test (χ²=5.08, df=1,

p=0.024) (

Figure 4a). However, total abundance did not differ significantly between years (Kruskal–Wallis χ²=1.56, df=1,

p=0.21), indicating that increased richness was not accompanied by higher abundance (

Figure 4b).

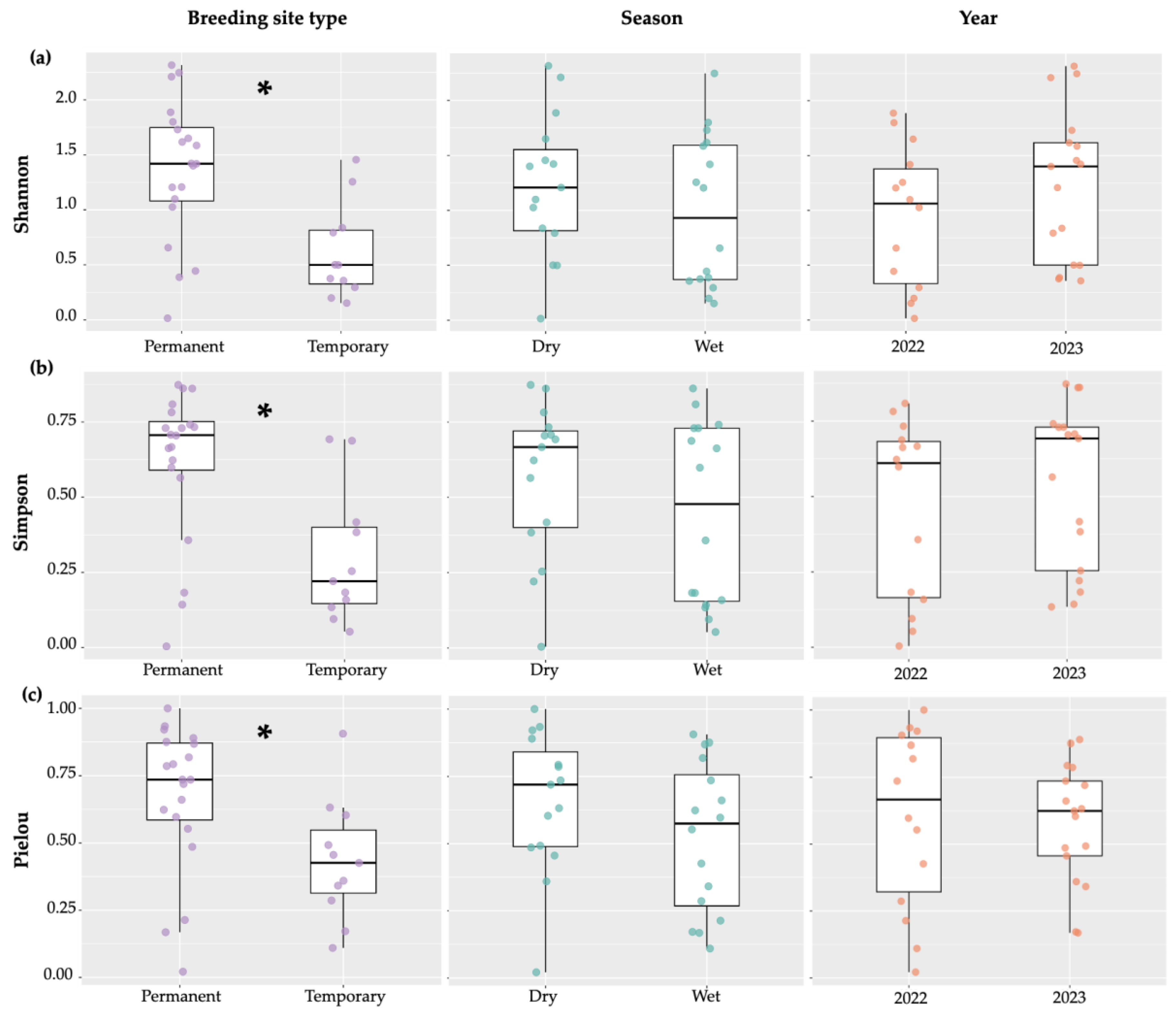

Shannon’s Index was significantly higher for permanent breeding sites indicating greater diversity (Estimate=-0.73, t=-3.66,

p=0.001), but no difference was found between seasons (Estimate=-0.20, t=-1.04,

p=0.31) or years (Estimate=0.36, t=1.87,

p=0.08) (

Figure 5a). The mean Shannon’s Index for family diversity in permanent breeding sites was

H′=1.36, indicating moderate diversity, whereas temporary breeding sites presented a mean of

H′=0.61, suggesting low diversity of aquatic macroinvertebrates.

Simpson’s diversity index, where zero represents uniformity and 1 represents complete diversity, was significantly higher in permanent breeding sites (

D=0.61) than temporary breeding sites (

D=0.29) (Estimate=-0.31, t=-3.99,

p=0.001). There was no significant difference between seasons (Estimate=-0.10, t=-1.41,

p=0.17) or years (Kruskal–Wallis χ²=1.33, df=1,

p=0.25) in Simpson’s diversity index (

Figure 5b).

Regarding evenness, Pielou’s index was significantly higher in permanent breeding sites (

J′=0.67) compared to temporary sites (

J′=0.43), with higher values indicating more balanced distributions of family abundance (

Figure 5c; Estimate=-0.23, t=-2.76,

p=0.01). There was no significant difference between seasons (Estimate=-0.12, t=-1.55,

p=0.13) or years (Estimate=-0.03, t=-0.38,

p=0.71) (

Figure 5c).

Overall, nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) did not show a significant effect of season (R²=0.05, F=1.55,

p=0.07) and year (R²=0.04, F=1.51,

p=0.07) on the aquatic macroinvertebrate composition (

Figure S2 and

Figure S3). However, the results indicated that breeding site type had a significant effect on composition (R²=0.06, F=1.86,

p=0.02). Permanent and temporary breeding site types were significantly different in terms of composition (based on Jaccard distance) (

Figure 6).

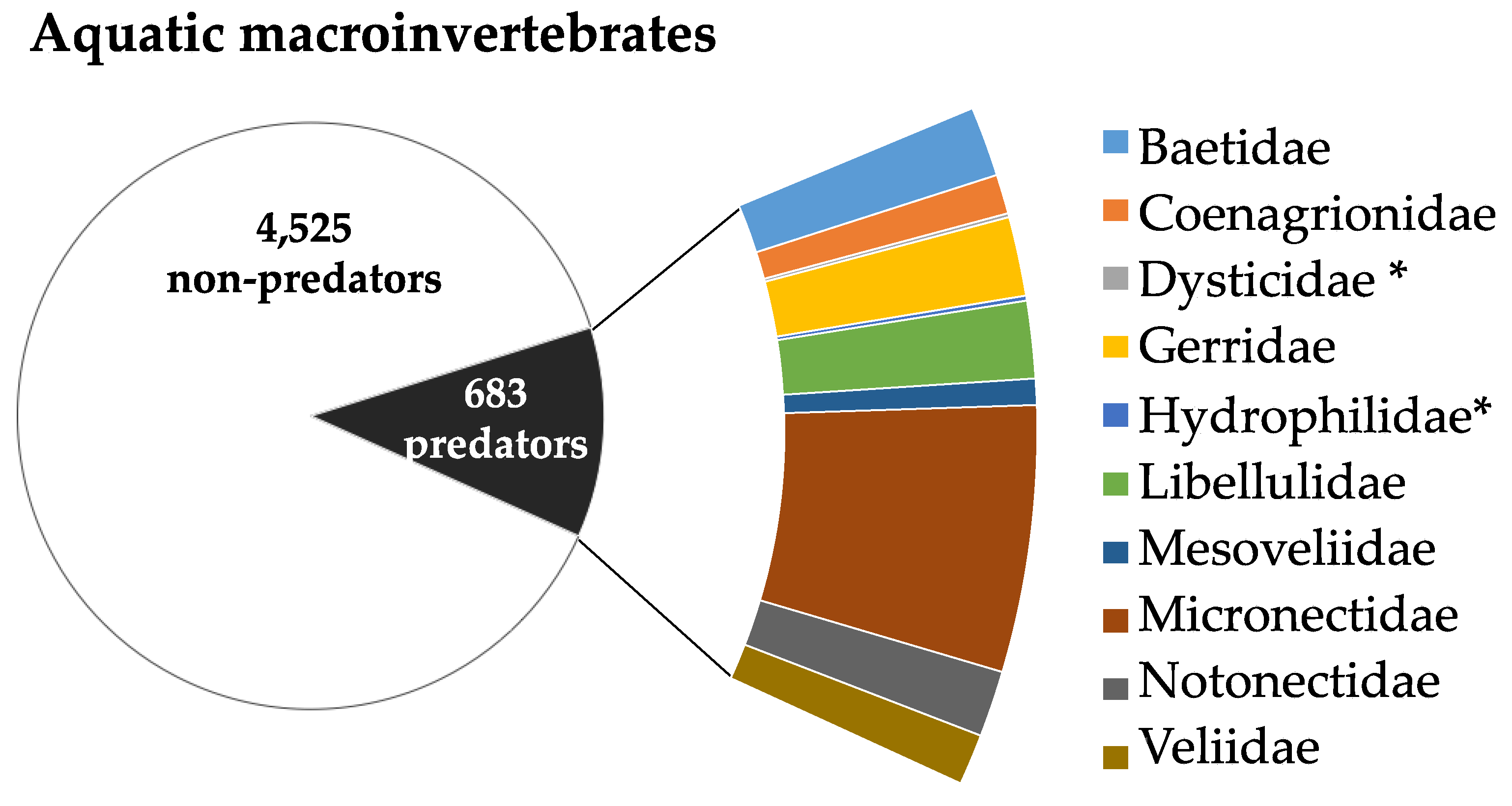

3.4. Predator Identification

Out of 5,208 macroinvertebrates sampled, 683 (13.1%) were identified as potential predators of

An. coluzzii, representing 10 families (

Figure 7), which all belonged to Class Insecta, were identified as potential predators of

An. coluzzii. The most abundant family was Micronectidae, with 266 individuals (38.9%), followed by Gerridae (79 individuals; 11.6%) and Libellulidae (77 individuals; 11.3%).

4. Discussion

Our study describes the aquatic macroinvertebrate community which shares the habitat of An. coluzzii, the malaria vector on the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe. Permanent and temporary breeding sites were sampled over dry and wet seasons for two consecutive years to determine variation in community composition. Breeding sites hosted important mosquito disease vectors (Anopheles, Culex and Aedes), as well as a diverse macroinvertebrate community encompassing eight classes, 15 orders and 51 families. Insects made up half of the sample and were the most diverse class (30 families), followed by Ostracoda with 45% abundance, comprising three families. The remaining samples included small numbers of other crustaceans, spiders, annelid worms, springtails, and mollusks. Ten of the 51 families sampled are potential predators of An. coluzzii, which made up approximately 13% abundance in the sample.

Members of the

Anopheles gambiae complex are known for their ability to colonize a variety of breeding sites [

26,

39]. Recent studies have shown successful development of

An. coluzzii, the focus of our study, in both temporary and permanent, and natural and human-made sites [

40,

41]. We sampled urban and coastal environments in STP where

An. coluzzii can develop. We found breeding sites were predominantly natural habitats, including swamps, streams, and puddles, with characteristics such as sunlight exposure, natural vegetation, and presence of debris, as described by similar studies conducted in mainland West Africa [

22,

39].

Our study revealed a diverse range of macroinvertebrates cohabitating aquatic breeding sites with the malaria vector

An. coluzzii in STP. The most abundant of the 51 families were Cyprididae (Podocopida), Culicidae (Diptera), Chironomidae (Diptera), Micronectidae (Hemiptera), Naididae (Tubificida), Gerridae (Hemiptera), Libellulidae (Odonata), Baetidae (Ephemeroptera), and Notonectidae (Hemiptera) (

Table S3). Previous studies have shown that members of the orders Diptera, Odonata, Ephemeroptera, Hemiptera and Coleoptera, which include our most abundant families sampled, are common groups that colonize

Anopheles larval habitats in mainland Africa [

23,

42,

43,

44].

We demonstrate increased macroinvertebrate diversity in permanent compared to temporary breeding sites across all three diversity indices measured. These results were supported by the NMDS analysis, which showed differences in the structure of the communities depending on water permanence. Our results highlight the role of stability in sustaining diverse communities. Permanent sites are likely to host a greater diversity of species due to greater time for colonization of the habitat [

45]; whereas frequent flooding and drying of temporary sites results in more extreme environmental conditions, which may allow fewer taxa to survive (e.g., [

46]). Other studies have found that temporary mosquito breeding sites tend to support lower macroinvertebrate densities [

23,

44,

47]. Consequently, temporary sites carry lower predation risk for mosquitoes, [

23,

48] but are less likely to support immature stages through to adulthood. Indeed, we found that Culicidae were more abundant in permanent sites (33% abundance in sample) than in temporary sites (10% abundance in sample).

It has been previously established that seasonality is an important factor shaping the structure of aquatic communities [

49,

50]. Li et al. [

50] found a higher number of taxa at breeding sites during the dry season when compared to the wet season. This phenomenon was attributed to the inability of certain species to withstand flooding, as well as to a greater variation in abiotic conditions. Similarly, the diversity indices in our study demonstrated higher diversity during the dry season, which may be indicative of increased stability in breeding sites due to reduced rainfall, leading to reduced washout of organisms and enhanced nutrient availability [

48,

51]. However, these differences were non-significant (except for Richness estimates). The absence of significant seasonal variations may be attributed to the weak seasonal variation observed in STP, where the rainy season persists for eight months and the dry season is short (four months). This equatorial climate is characterized by less marked seasonal transitions, resulting in relatively stable conditions throughout the year. This mitigates the impact of seasonal variations on aquatic biodiversity [

20].

Minor interannual variation was observed in aquatic macroinvertebrate communities, shown by Richness estimates only, indicating a stable community composition between 2022 and 2023. This temporal stability is critical for monitoring programs linked to the release of genetically engineered mosquitoes (GEM), as it provides a consistent baseline to detect post-release ecological impacts [

15,

16]. The persistence of similar taxonomic groups across years improves the ability to identify changes attributable to GEM interventions [

9,

15]. This stability can support the use of these aquatic habitats or potential aquatic predators for long-term ecological studies and risk assessments in vector control strategies involving GEM.

Potential aquatic predators of

An. coluzzii made up 13% of the sample. All predators identified were insects, with families Micronectidae (Hemiptera), Gerridae (Hemiptera) and Libellulidae (Odonata) being the most abundant. Other studies similarly identified Odonata and Hemiptera as important population regulators of mosquitoes [

52,

53,

54,

55]. Aquatic predators can play a fundamental role in the control of

Anopheles populations and have been suggested as a potential biocontrol solution [

56,

57]. The presence of predators in an aquatic habitat can also affect mosquito oviposition site choice and immature development rate [

58]. Mosquitoes are likely to be an important part of the food web, and, as such, an ecological assessment should be made of the impact of GEM predation on these predators.

5. Conclusions

Our study is the first to describe the aquatic macroinvertebrate diversity associated with An. coluzzii in STP, finding a variety of insects, crustaceans, spiders, annelid worms, springtails, and mollusks. Diversity was higher in permanent sites when compared to temporary sites, reinforcing the importance of stability for maintaining diverse communities. Anopheles coluzzii larvae are a likely prey for several aquatic macroinvertebrate taxa in STP so laboratory studies should be undertaken to assess the impact of GEM release on these taxa. This also emphasizes that a method which modifies the mosquito population, rather than suppressing it, is likely to have a lesser ecological impact on this diverse ecosystem.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Sampling sites selected in each locality on the study. A) STC permanent; B) STC temporary; C) BFO permanent; D) BFO temporary; E) RBA permanent; F) RBA temporary; G) MAL permanent; H) MAL temporary; I) PIA permanent; J) PIA temporary.; Figure S2. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot based on a Jaccard similarity matrix, showing aquatic macroinvertebrate composition during the wet and dry seasons. No significant differences were detected between seasons. 2D stress = 0.12.; Figure S3. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot based on a Jaccard similarity matrix, showing aquatic macroinvertebrate composition across sampling years. No significant differences were observed between years. 2D stress = 0.12.; Table S1: Geographic coordinates of breeding sites by locality on the Islands of São Tomé and Príncipe.; Table S2: Presence and absence of aquatic macroinvertebrates collected on different sampling seasons and breeding site types on the Islands of São Tomé and Príncipe.; Table S3: The abundance (a) and relative abundance (%RA) of macroinvertebrates in different sampling seasons and breeding site type on the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., A.J.C. and G.C.L.; methodology, J.P., M.J.C. and R.E.D.; formal analysis, M.J.C., M.C. and H.W.; investigation, M.J.C., R.E.D., J.V., M.D.C. and J.P.; data curation, M.J.C., C.M.E. and A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J.C., M.C. and H.W.; writing—review and editing, M.J.C., M.C., C.M.E., H.W., J.P. and G.C.L.; supervision, J.P.; project administration, G.C.L.; funding acquisition, G.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Open Philanthropy Project, grant number (A22-2768-001). This study was implemented in the framework of the University of California Malaria Initiative (http://stopmalaria.org).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the field entomology team from National Malaria Elimination Programme (PNEP) of São Tomé and Príncipe for helping our field work in São Tomé. We would like to thank the Bohart Museum at UCDavis for support on taxonomic identification.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GEM |

Genetically engineered mosquitoes |

| STP |

São Tomé and Príncipe |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| UCMI |

University of California Malaria Initiative |

| ERA |

Environmental risk assessment |

| STC |

Santa Catarina |

| BFO |

Bobo Forro |

| RBA |

Ribeira Afonso |

| MAL |

Vila Malanza |

| PIA |

Lenta Pia |

| CNE |

National Center of Endemic Diseases |

| USTP |

University of São Tomé and Príncipe |

| GLMM |

Generalized Linear Mixed Model |

| NMDS |

Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling |

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2023 (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Obeagu, E.I.; Obeagu, G.U. Emerging public health strategies in malaria control: innovations and implications. Ann. Med. Surg. 2024, 86, 6576–6584. [CrossRef]

- Rathmes, G.; Rumisha, S.F.; Lucas, T.C.D.; Twohig, K.A.; Python, A.; Nguyen, M.; Nandi, A.K.; Keddie, S.H.; Collins, E.L.; Rozier, J.A.; et al. Global estimation of anti-malarial drug effectiveness for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium falciparum malaria 1991–2019. Malar. J. 2020, 19, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.L.; Courtenay, O.; Kelly-Hope, L.A.; Scott, T.W.; Takken, W.; Torr, S.J.; Lindsay, S.W. The importance of vector control for the control and elimination of vector-borne diseases. PLOS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0007831. [CrossRef]

- Sanou, A.; Nelli, L.; Guelbéogo, W.M.; Cissé, F.; Tapsoba, M.; Ouédraogo, P.; Sagnon, N.; Ranson, H.; Matthiopoulos, J.; Ferguson, H.M. Insecticide resistance and behavioural adaptation as a response to long-lasting insecticidal net deployment in malaria vectors in the Cascades region of Burkina Faso. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Suh, P.F.; Elanga-Ndille, E.; Tchouakui, M.; Sandeu, M.M.; Tagne, D.; Wondji, C.; Ndo, C. Impact of insecticide resistance on malaria vector competence: a literature review. Malar. J. 2023, 22, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/guidelines-for-malaria (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Ditter, R.E.; Campos, M.; Crepeau, M.W.; Pinto, J.; Toilibou, A.; Amina, Y.; Tantely, L.M.; Girod, R.; Lee, Y.; Cornel, A.J.; et al. Anopheles gambiae on remote islands in the Indian Ocean: origins and prospects for malaria elimination by genetic modification of extant populations. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Carballar-Lejarazú, R. and James, A.A. Population modification of Anopheline species to control malaria transmission. Pathog Glob Health 2017, 111, 424–435.

- James, A.A. Gene drive systems in mosquitoes: rules of the road. Trends Parasitol. 2005, 21, 64–67. [CrossRef]

- Carballar-Lejarazú, R.; Ogaugwu, C.; Tushar, T.; Kelsey, A.; Pham, T.B.; Murphy, J.; Schmidt, H.; Lee, Y.; Lanzaro, G.C.; James, A.A. Next-generation gene drive for population modification of the malaria vector mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020, 117, 22805–22814. [CrossRef]

- Resnik, D.B. Field Trials of Genetically Modified Mosquitoes and Public Health Ethics. Am. J. Bioeth. 2017, 17, 24–26. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Scientific Opinion on the assessment of potential impacts of genetically modified plants on non-target organisms. EFSA Journal 2010, 8, 1877.

- Lenat, D.R.; Crawford, J.K. Effects of land use on water quality and aquatic biota of three North Carolina Piedmont streams. Hydrobiologia 1994, 294, 185–199. [CrossRef]

- Carstens, K.; Anderson, J.; Bachman, P.; De Schrijver, A.; Dively, G.; Federici, B.; Hamer, M.; Gielkens, M.; Jensen, P.; Lamp, W.; et al. Genetically modified crops and aquatic ecosystems: considerations for environmental risk assessment and non-target organism testing. Transgenic Res. 2011, 21, 813–842. [CrossRef]

- Kormos, A.; Dimopoulos, G.; Bier, E.; Lanzaro, G.C.; Marshall, J.M.; James, A.A. Conceptual risk assessment of mosquito population modification gene-drive systems to control malaria transmission: preliminary hazards list workshops. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1261123. [CrossRef]

- Lanzaro, G.C.; Campos, M.; Crepeau, M.; Cornel, A.; Estrada, A.; Gripkey, H.; Haddad, Z.; Kormos, A.; Palomares, S. Selection of sites for field trials of genetically engineered mosquitoes with gene drive. Evol. Appl. 2021, 14, 2147–2161. [CrossRef]

- Marshall, J.C.; Pinto, J.; Charlwood, D.J.; Gentile, G. Exploring the origin and degree of genetic isolation of anopheles gambiae from the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe, potential sites for testing transgenic-based vector control. Evol Appl 2008, 1, 631–644.

- Campos, M.; Hanemaaijer, M.; Gripkey, H.; Collier, T.C.; Lee, Y.; Cornel, A.J.; Pinto, J.; Ayala, D.; Rompão, H.; Lanzaro, G.C. The origin of island populations of the African malaria mosquito, Anopheles coluzzii. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Ceríaco, L.; De Lima, R.; Melo, M.; Bell, R. Biodiversity of the Gulf of Guinea Oceanic Islands. 1st ed.; Publisher: Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–694.

- de Souza, D.; Kelly-Hope, L.; Lawson, B.; Wilson, M.; Boakye, D.; Sinnis, P. Environmental Factors Associated with the Distribution of Anopheles gambiae s.s in Ghana; an Important Vector of Lymphatic Filariasis and Malaria. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e9927. [CrossRef]

- Hinne, I.A.; Attah, S.K.; Mensah, B.A.; Forson, A.O.; Afrane, Y.A. Larval habitat diversity and Anopheles mosquito species distribution in different ecological zones in Ghana. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Onen, H.; Odong, R.; Chemurot, M.; Tripet, F.; Kayondo, J.K. Predatory and competitive interaction in Anopheles gambiae sensu lato larval breeding habitats in selected villages of central Uganda. Parasites Vectors 2021, 14, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Loiseau, C.; Melo, M.; Lee, Y.; Pereira, H.; Hanemaaijer, M.J.; Lanzaro, G.C.; Cornel, A.J.; Didham, R.; Gilbert, F. High endemism of mosquitoes on São Tomé and Príncipe Islands: evaluating the general dynamic model in a worldwide island comparison. Insect Conserv. Divers. 2018, 12, 69–79. [CrossRef]

- Kenea, O.; Balkew, M.; Gebre-Michael, T. Environmental factors associated with larval habitats of anopheline mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) in irrigation and major drainage areas in the middle course of the Rift Valley, central Ethiopia. J Vector Borne Dis. 2011, 48, 85–92.

- A Sattler, M.; Mtasiwa, D.; Kiama, M.; Premji, Z.; Tanner, M.; Killeen, G.F.; Lengeler, C. Habitat characterization and spatial distribution of Anopheles sp. mosquito larvae in Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) during an extended dry period. Malar. J. 2005, 4, 4–4. [CrossRef]

- Dahms, H.-U.; Fornshell, J.A.; Fornshell, B.J. Key for the identification of crustacean nauplii. Org. Divers. Evol. 2006, 6, 47–56. [CrossRef]

- Martens, K.; Schön, I.; Meisch, C.; Horne, D.J. Global diversity of ostracods (Ostracoda, Crustacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 2007, 595, 185–193. [CrossRef]

- Novelo-Gutiérrez, R. and Sites, R. The Dragonfly Nymphs of Thailand (Odonata: Anisoptera). 1st ed; Publisher: Springer, Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1-491.

- Ubick, D.; Paquin, P.; Cushing, P.; Roth, V. Spiders of North America: An Identification Manual. 2nd ed.; Publisher: American Arachnological Society, 2017; pp. 1-431.

- Triplehorn, C.A.; Johnson, N.F. Borror and Delong´s Introduction to Study of Insects. 7th ed. Publisher: Cengage Learning, 2004; pp. 1-888.

- Merritt, R.W.; Cummins, K.W.; Berg, M.B. An Introduction to the Aquatic Insects of North America. 5th ed. Publisher: Kendall Hunt Publishing, 2019; pp. 1-1480.

- Onen, H.; Kaddumukasa, M.A.; Kayondo, J.K.; Akol, A.M.; Tripet, F. A review of applications and limitations of using aquatic macroinvertebrate predators for biocontrol of the African malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae sensu lato. Parasites Vectors 2024, 17, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Posit team (2025). RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R. Posit Software, PBC, Boston, MA. Available online: http://www.posit.co/. (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- Vegan: Community Ecology Package. J Stat Softw 2017. Available online: https://github.com/vegandevs/vegan (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Package ‘car’. J Stat Softw 2024. Available online: https://r-forge.r-project.org/projects/car/ (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Kuznetsova, A.; Brockhoff, P.B.; Christensen, R.H.B. lmerTest Package: Tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 2017, 82, 1–26. https://doi:10.18637/jss.v082.i13.

- Lubna; Rasheed, S.B.; Zaidi, F. Species diversity pattern of mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) breeding in different permanent, temporary and natural container habitats of Peshawar, KP Pakistan. Braz. J. Biol. 2024, 84, e271524. [CrossRef]

- Mattah, P.A.D.; Futagbi, G.; Amekudzi, L.K.; Mattah, M.M.; de Souza, D.K.; Kartey-Attipoe, W.D.; Bimi, L.; Wilson, M.D. Diversity in breeding sites and distribution of Anopheles mosquitoes in selected urban areas of southern Ghana. Parasites Vectors 2017, 10, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Longo-Pendy, N.M.; Tene-Fossog, B.; Tawedi, R.E.; Akone-Ella, O.; Toty, C.; Rahola, N.; Braun, J.-J.; Berthet, N.; Kengne, P.; Costantini, C.; et al. Ecological plasticity to ions concentration determines genetic response and dominance of Anopheles coluzzii larvae in urban coastal habitats of Central Africa. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Chamberland, L.; Campos, M.; Corrêa, M.; Pinto, J.; Cornel, A.J.; Viegas, J.; Lanzaro, G.C. Larval habitat suitability and landscape genetics of the mosquito Anopheles coluzzii on São Tomé and Príncipe islands. Landsc. Ecol. 2025, 40, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Gowelo, S.; Chirombo, J.; Koenraadt, C.J.; Mzilahowa, T.; Berg, H.v.D.; Takken, W.; McCann, R.S. Characterisation of anopheline larval habitats in southern Malawi. Acta Trop. 2020, 210, 105558–105558. [CrossRef]

- Onen, H.; Kaindoa, E.W.; Nkya, J.; Limwagu, A.; Kaddumukasa, M.A.; Okumu, F.O.; Kayondo, J.K.; Akol, A.M.; Tripet, F. Semi-field experiments reveal contrasted predation and movement patterns of aquatic macroinvertebrate predators of Anopheles gambiae larvae. Malar. J. 2025, 24, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Mahenge, H.H.; Muyaga, L.L.; Nkya, J.D.; Kifungo, K.S.; Kahamba, N.F.; Ngowo, H.S.; Kaindoa, E.W.; Masese, F.O. Common predators and factors influencing their abundance in Anopheles funestus aquatic habitats in rural south-eastern Tanzania. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0287655. [CrossRef]

- Mouquet, N.; Munguia, P.; Kneitel, J.M.; Miller, T.E. Community assembly time and the relationship between local and regional species richness. Oikos 2003, 103, 618–626. [CrossRef]

- Walls, S.C.; Barichivich, W.J.; Brown, M.E. Drought, Deluge and Declines: The Impact of Precipitation Extremes on Amphibians in a Changing Climate. Biology 2013, 2, 399–418. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Aditya, G.; Saha, N.; Saha, G.K. An assessment of macroinvertebrate assemblages in mosquito larval habitats—space and diversity relationship. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 168, 597–611. [CrossRef]

- Minakawa, N.; Githure, J.I.; Beier, J.C.; Yan, G. Anopheline mosquito survival strategies during the dry period in western Kenya.. J. Med Èntomol. 2001, 38, 388–392. [CrossRef]

- Couceiro, S.R.M.; Dias-Silva, K.; Hamada, N. Influence of climate seasonality on the effectiveness of the use of aquatic macroinvertebrates in urban impact evaluation in central Amazonia. Limnology 2021, 22, 237–244. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tonkin, J.D.; Meng, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Xie, Z.; Heino, J. Seasonal variation in the metacommunity structure of benthic macroinvertebrates in a large river-connected floodplain lake. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136. [CrossRef]

- Righi-Cavallaro, K.; Roche, K.F.; Froehlich, O.; Cavallaro, M.R. Structure of macroinvertebrate communities in riffles of a Neotropical karst stream in the wet and dry seasons. Acta Limnologica Brasiliensia 2010, 22, 306–316.

- Kweka, E.J.; Zhou, G.; Gilbreath, T.M.; Afrane, Y.; Nyindo, M.; Githeko, A.K.; Yan, G. Predation efficiency of Anopheles gambiae larvae by aquatic predators in western Kenya highlands. Parasites Vectors 2011, 4, 128–128. [CrossRef]

- Ohba, S.-Y.; Huynh, T.T.; Kawada, H.; Le, L.L.; Ngoc, H.T.; Le Hoang, S.; Higa, Y.; Takagi, M. Heteropteran insects as mosquito predators in water jars in southern Vietnam. J. Vector Ecol. 2011, 36, 170–174. [CrossRef]

- Brahma, S.; Aditya, G.; Sharma, D.; Saha, N.; Kundu, M.; Saha, G.K. Influence of density on intraguild predation of aquatic Hemiptera (Heteroptera): implications in biological control of mosquito. J. Èntomol. Acarol. Res. 2014, 46, 6–12. [CrossRef]

- Sapari, B.N.; Manan, T. S. B. and Yavari, S. Sustainable control of mosquito by larval predating Micronecta polhemus Niser for the prevention of mosquito breeding in water retaining structures. Int J Mosq Res 2019, 6, 31–37.

- Quiroz-Martinez, H. and Rodríguez-Castro, A. Aquatic insects as predators of mosquito larvae. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 2007, 23, 110–117.

- Saha, N.; Aditya, G.; Banerjee, S.; Saha, G.K. Predation potential of odonates on mosquito larvae: Implications for biological control. Biol. Control. 2012, 63, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Munga, S.; Minakawa, N.; Zhou, G.; Barrack, O.-O.J.; Githeko, A.K.; Yan, G. Effects of Larval Competitors and Predators on Oviposition Site Selection of Anopheles gambiae Sensu Stricto. J. Med Èntomol. 2006, 43, 221–224. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of the study localities (yellow circles) on the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe: (a) Location of São Tomé and Príncipe in relation to the African continent; (b) Study locality on Príncipe Island; (c) Study localities on São Tomé Island.

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of the study localities (yellow circles) on the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe: (a) Location of São Tomé and Príncipe in relation to the African continent; (b) Study locality on Príncipe Island; (c) Study localities on São Tomé Island.

Figure 2.

Class abundance of aquatic macroinvertebrates by island (São Tomé, Príncipe), season (dry, wet), breeding site type (permanent, temporary) and overall.

Figure 2.

Class abundance of aquatic macroinvertebrates by island (São Tomé, Príncipe), season (dry, wet), breeding site type (permanent, temporary) and overall.

Figure 3.

Family total taxa richness (a), and total abundance (b) of macroinvertebrates. Family-level Venn Diagram (c), showing the differences observed across the study’s sampling parameters, including seasons and breeding site types.

Figure 3.

Family total taxa richness (a), and total abundance (b) of macroinvertebrates. Family-level Venn Diagram (c), showing the differences observed across the study’s sampling parameters, including seasons and breeding site types.

Figure 4.

Richness (a) and Abundance (b) of aquatic macroinvertebrates across different breeding site types and seasons. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences (p<0.05) between groups. The points represent the individual values of each sample, showing the dispersion of the data.

Figure 4.

Richness (a) and Abundance (b) of aquatic macroinvertebrates across different breeding site types and seasons. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences (p<0.05) between groups. The points represent the individual values of each sample, showing the dispersion of the data.

Figure 5.

Biodiversity. Shannon’s index (a), Simpson’s index (b) and Pielou’s index (c) of aquatic macroinvertebrate biodiversity in between breeding site types, seasons and years in São Tomé and Príncipe. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences (p<0.05) between groups. The points represent the individual values of each sample, showing the dispersion of the data.

Figure 5.

Biodiversity. Shannon’s index (a), Simpson’s index (b) and Pielou’s index (c) of aquatic macroinvertebrate biodiversity in between breeding site types, seasons and years in São Tomé and Príncipe. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences (p<0.05) between groups. The points represent the individual values of each sample, showing the dispersion of the data.

Figure 6.

Aquatic macroinvertebrate composition. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot based on a Jaccard similarity matrix, showing differences in aquatic macroinvertebrate composition between permanent and temporary breeding sites. Each point represents a sample, with colors and shapes indicating the breeding site type (permanent or temporary). Polygons represent the convex hulls encompassing each group. 2D stress = 0.12.

Figure 6.

Aquatic macroinvertebrate composition. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot based on a Jaccard similarity matrix, showing differences in aquatic macroinvertebrate composition between permanent and temporary breeding sites. Each point represents a sample, with colors and shapes indicating the breeding site type (permanent or temporary). Polygons represent the convex hulls encompassing each group. 2D stress = 0.12.

Figure 7.

Proportion of An. coluzzii predators in São Tomé and Príncipe islands and the relative abundance of each identified predator family. Asterisks (*) indicate families with values below 1%.

Figure 7.

Proportion of An. coluzzii predators in São Tomé and Príncipe islands and the relative abundance of each identified predator family. Asterisks (*) indicate families with values below 1%.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Anopheles coluzzii larval habitats on the Islands of São Tomé and Príncipe, during 2022 – 2023. STC – Santa Catarina; BFO – Bobo Forro; RBA – Ribeira Afonso; MAL - Vila Malanza; PIA – Lenta Pia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Anopheles coluzzii larval habitats on the Islands of São Tomé and Príncipe, during 2022 – 2023. STC – Santa Catarina; BFO – Bobo Forro; RBA – Ribeira Afonso; MAL - Vila Malanza; PIA – Lenta Pia.

| Locality |

Breeding site type |

Nature of breeding site |

Habitat category |

Intensity of light |

Turbidity |

Vegetation |

Water current |

| STC |

permanent |

natural |

Swamp |

light |

clear |

present |

still |

| temporary |

natural |

Stream |

light |

clear |

absent |

still |

| BFO |

permanent |

natural |

small puddle |

light |

turbid |

present |

still |

| temporary |

natural |

roadside puddle |

light |

clear |

absent |

still |

| RBA |

permanent |

man-made |

artificial hole |

light |

clear |

present |

still |

| temporary |

natural |

small puddle |

light |

turbid |

present |

still |

| MAL |

permanent |

natural |

Stream |

light |

clear |

present |

slow |

| temporary |

natural |

Swamp |

light |

turbid |

present |

still |

| PIA |

permanent |

natural |

Swamp |

light |

clear |

present |

still |

| temporary |

natural |

roadside puddle |

light |

clear |

absent |

still |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).