1. Introduction

Tourism demand is typically quantified through indicators such as the number of arrivals, overnight stays (bed-nights), visitor counts, international tourism receipts, and expenditure on tourism imports. The selection of specific indicators is contingent upon data availability and the level of geographical aggregation [

38]. Tourism demand forecasting, particularly through the lens of overnight stays, has garnered significant attention in recent years due to its critical role in strategic planning and resource allocation within the tourism and hospitality sectors. Overnight stays serve as a tangible indicator of tourist engagement and economic impact, making them a focal point for predictive modelling [

2,

9,

11,

13,

24,

34,

38,

43,

45].

Traditional forecasting methods, before 1990s such as time series regression methods - models like ARIMA and SARIMA, have been widely utilized for their simplicity and interpretability [

27,

53]. On the other hand, prior the 2020’s, research was increasingly focused on the application of advanced econometric methodologies, including cointegration analysis, error correction models (ECM), vector autoregressive (VAR) processes, and time-varying parameter (TVP) approaches [

53]. However, these models often fall short in capturing the nonlinear patterns and complex seasonality inherent in tourism data. Therofore, in the beginning of 2020’s, in response to the growing interest in advanced forecasting models, the primary objective is to evaluate the comparative predictive performance of neural network models (ANN), seasonal SARIMAX, standard GARCH (sGARCH), and asymmetric GARCH specifications such as the Glosten–Jagannathan–Runkle GARCH (GJR-GARCH) model, relative to simpler benchmark alternatives. Among these, asymmetric GARCH models—particularly the GJR-GARCH—have been established to demonstrate superior out-of-sample forecasting accuracy [

3,

38]. Consequently, to address these limitations, researchers have increasingly turned to advanced computational techniques.

For instance, Alvarez-Diaz et al. [

2] employed a Nonlinear Autoregressive Neural Network (NAR) combined with Genetic Programming to forecast international tourism demand, demonstrating improved accuracy over traditional models. Similarly, Hsieh [

18] explored the application of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and their variants, such as Bidirectional LSTM and Gated Recurrent Units (GRU), to effectively model the temporal dependencies in Taiwan's tourism demand data.

The integration of big data sources has further enhanced forecasting capabilities. Studies have incorporated variables like search engine trends, weather conditions, and social media activity to enrich predictive models. For example, the use of Google Trends data has been shown to improve the forecasting of tourist arrivals and overnight stays in Prague, as demonstrated by a study utilizing MIDAS regression techniques [

16]. Moreover, innovative approaches like the inverted transformer model have been applied to daily tourism demand forecasting, capturing complex patterns through self-attention mechanisms, applied for predicting daily tourist volumes, including overnight visitors [

8].

These advancements underscore a paradigm shift towards more sophisticated, data-driven forecasting methods that can adapt to the dynamic nature of tourism demand. By leveraging machine learning and big data analytics, stakeholders can achieve more accurate and timely insights, facilitating better decision-making in tourism management and policy development [

17,

50,

55].

In recent years, the integration of advanced artificial intelligence (AI) tools and deep learning frameworks has further revolutionized tourism demand forecasting, particularly concerning overnight stays. Among these, Facebook Prophet and the DARTS library have emerged as prominent instruments due to their adaptability and robust performance in handling complex time series data [

17].

Facebook Prophet, developed by Facebook's Core Data Science team, is an open-source forecasting tool designed to accommodate time series data exhibiting multiple seasonality with linear or non-linear growth trends [

50]. Its capability to incorporate holiday effects and manage missing data makes it particularly suitable for tourism demand forecasting [

40]. For instance, studies have applied Prophet to forecast international tourist arrivals in Indonesia during the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrating its effectiveness in capturing the impact of unprecedented events on tourism trends [

20]. Similarly, research focusing on Albania utilized Prophet to model and forecast tourist arrivals, achieving an accuracy rate of 88%, thereby highlighting its practical applicability in diverse geographical contexts [

3].

The practical implications of accurate tourism forecasting extend beyond academic interest, directly impacting investment decisions, policy formulation, and crisis management strategies. As demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional forecasting models often prove inadequate during periods of structural breaks and unprecedented volatility, necessitating the development of more adaptive and robust methodological frameworks. This review synthesizes recent developments in forecasting methodologies, focusing on the integration of macroeconomic variables, hybrid modelling approaches, and the incorporation of external data sources to enhance predictive accuracy in real-world applications. The adoption of these AI-driven tools signifies a shift towards more sophisticated forecasting methodologies in the tourism sector. By leveraging the strengths of models like Facebook Prophet and Python libraries, so stakeholders can enhance the accuracy of their forecasts, thereby facilitating more informed decision-making processes in tourism planning and management.

2. Materials and Methods

Tourism demand forecasting represents a critical component of strategic planning for destinations and service providers, particularly given the sector's heightened sensitivity to macroeconomic fluctuations and external shocks. The ability to accurately predict tourism flows enables stakeholders to optimize resource allocation, manage capacity constraints, and develop resilient recovery strategies during crisis periods. With the proliferation of data availability and computational advances, the field has witnessed a paradigm shift from classical statistical models to hybrid architectures that integrate artificial intelligence with traditional econometric approaches. This evolution is particularly relevant for understanding the complex relationships between macroeconomic indicators such as GDP and Consumer Price Index (CPI) and tourism demand patterns, particularly during disruptive internal or external tourism system events.

Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

Early tourism demand forecasting relied heavily on econometric models that explicitly incorporated macroeconomic determinants, recognizing tourism as a luxury good with high income elasticity. Traditional models, such as the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) and error correction models (ECM), have long been employed to capture the long-run relationships and short-term dynamics of tourism demand determinants, including GDP, relative prices, and exchange rates [

31,

49]. These foundational approaches established the theoretical framework for understanding how macroeconomic conditions translate into tourism demand fluctuations.

Dynamic panel data models, particularly those using the Generalized Method of Moments (GMM), have proven effective in capturing heterogeneity across regions while controlling for endogeneity in explanatory variables. Serra et al. [

46] applied such models to Portuguese tourism data and concluded that income elasticities for international tourism demand suggest it is a luxury good, with demand being heterogeneously distributed across regions. Such finding has significant practical implications for destination marketing organizations, as it suggests that economic growth in source markets directly translates to disproportionate increases in tourism demand.

On the other hand, the significance of GDP as a primary determinant has been substantiated through various empirical studies. Žmuk and Gržinić [

32] employed multiple linear regression models to predict inbound tourism to Croatia, confirming that macroeconomic variables such as GDP, Consumer Price Index (CPI), and exchange rates remain key determinants of tourism demand. However, their research also highlighted the limitations of traditional linear approaches, particularly during periods of economic volatility where non-linear relationships become more pronounced.

Crouch et al. [

5] seminal work on income elasticity demonstrated that demand-side behaviour in international tourism exhibits significant regional and income-level variations, with elasticity values typically ranging between 0.5 and 2.0 for international travel. These findings confirm that while GDP remains a robust predictor, its context-sensitive nature necessitates adaptive forecasting approaches that can account for demographic and economic heterogeneity across different market segments. The practical implication is that destinations must tailor their forecasting models to specific source markets, recognizing that GDP impact varies significantly across different economic contexts [

32].

As mentioned above, the foundation of modern tourism forecasting was built upon Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) and its seasonal counterpart (SARIMA), models favoured for their interpretability and effectiveness in handling univariate time series data. These models have served as performance benchmarks in subsequent comparative studies, providing baseline accuracy measures against which newer methodologies are evaluated. Yu et al. [

57] proposed the SA-D model, which combines SARIMA with dendritic neural networks to address nonlinear residuals remaining after deseasonalization and detrending, demonstrating superior performance compared to standalone SARIMA models. This hybrid approach represents an early recognition that purely statistical models may be insufficient for capturing the complex, non-linear relationships inherent in tourism demand data.

Silva and Alonso [

47] analysed overnight stays in Portugal using SARIMA alongside neural networks and exponential smoothing, confirming the persistent effectiveness of neural network approaches even when compared to newer statistical methods. Their work highlighted the practical challenge of model selection in operational contexts, where the trade-off between interpretability and accuracy must be carefully balanced. This consideration becomes particularly relevant when forecasting models are used to inform policy decisions or investment strategies that require stakeholder understanding and buy-in [

49].

The comprehensive review by Song et al. [

49] of 211 key publications from 1968 to 2018 categorized forecasting approaches into time series, econometric, AI-based, and judgmental models, revealing an evolutionary trend toward increased model diversity, hybridization, and enhanced accuracy. Importantly, they concluded that no single model consistently outperforms others across different contexts, emphasizing the need for flexible, context-sensitive forecasting approaches. This finding has profound practical implications, suggesting that operational forecasting systems should incorporate multiple methodologies and adaptive selection mechanisms rather than relying on a single "best" model.

The advancement of computational power has catalysed the adoption of neural network-based models, particularly Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their variants, which demonstrate superior performance in capturing nonlinear relationships between economic indicators and tourism demand. Salamanis et al. [

42] applied Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to long-term hotel booking data in Greece, demonstrating enhanced predictive strength when weather data were incorporated as exogenous variables alongside traditional economic indicators. This multi-variate approach reflects the practical reality that tourism demand responds to a complex interplay of economic, environmental, and social factors.

Yu and Chen [

56] extended this approach by developing a Stacked Autoencoder LSTM (SAE-LSTM) architecture that leverages unsupervised pretraining and deep network fine-tuning. Their work highlighted significant improvements over standard LSTM models through the integration of autoencoder-based feature extraction, demonstrating the practical value of deep learning techniques in handling high-dimensional economic data. The ability to automatically extract relevant features from complex economic datasets represents a significant advancement for practitioners who may not have extensive domain expertise in feature engineering.

Hsieh [

18] validated the effectiveness of LSTM, Bi-LSTM, and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) networks in modelling Taiwanese tourism demand, particularly during crisis periods such as SARS and COVID-19. All three models demonstrated superior forecasting accuracy compared to classical fuzzy time series approaches, with enhanced robustness during volatile periods when traditional economic relationships may break down. This robustness during crisis periods has immediate practical implications for destination management organizations and policymakers who must maintain operational planning capabilities during periods of unprecedented uncertainty.

The integration of machine learning into tourism demand forecasting has significantly enhanced the ability to capture complex interactions between GDP, CPI, and other macroeconomic variables where traditional econometric models often fall short. Sofianos et al. [

48] analysed financial forecasting in the U.S. tourism industry using supervised and unsupervised ML methods, highlighting the superior performance of neural networks in predicting consumer spending and market fluctuations compared to traditional econometric approaches.

To address the limitations of single-model approaches while maintaining the theoretical foundation of macroeconomic relationships, hybrid and ensemble models have gained significant traction in recent research. These approaches represent the practical recognition that tourism demand forecasting requires both the theoretical rigor of econometric models and the flexibility of machine learning techniques. Ouassou and Taya [

36] conducted a comparative analysis of ARIMA, Support Vector Regression (SVR), XGBoost, and LSTM models for regional tourism demand forecasting in Morocco, demonstrating that ensemble models integrating both conventional statistical and AI-based approaches achieved superior performance compared to individual models.

Zheng and Zhang [

59] developed a novel hybrid gray model-LSTM (GM-LSTM) approach for tourism forecasting in Xi'an, China, which effectively addressed small sample limitations by combining a first-order gray model for trend extraction with LSTM to model nonlinear residuals. Their hybrid architecture achieved a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 11.88%, demonstrating superior forecasting efficiency and adaptability in capturing both trend and fluctuation patterns. The practical significance of this approach lies in its ability to perform well with limited historical data, a common challenge in emerging tourism destinations or when modelling new market segments.

Rashad [

41] introduced a hybridization strategy involving the integration of macroeconomic indicators and web search data (Google Destination Insight) into ARIMAX models, validated using tourism data from Dubai and demonstrating enhanced forecasting precision in the post-COVID-19 recovery period. This approach exemplifies the practical evolution of forecasting models to incorporate real-time behavioural indicators alongside traditional economic variables, providing more responsive and timely predictions for operational decision-making.

Lu et al. [

32] proposed an Improved Attention-based Gated Recurrent Unit (IA-GRU) model enhanced with horizontal attention mechanisms and competitive random search optimization. Their framework achieved superior accuracy by effectively integrating web search indices and climate comfort indicators with traditional economic variables, demonstrating the value of attention mechanisms in identifying the most relevant economic predictors for specific forecasting contexts.

The COVID-19 pandemic has served as a critical case study for stress-testing forecasting models and understanding the practical limitations of traditional approaches during periods of structural economic disruption. Gunter et al. [

15]employed a panel Fully Modified Ordinary Least Squares (FMOLS) approach to estimate outbound tourism expenditure in the EU under baseline and downside scenarios, showing a clear correlation between GDP losses and tourism sector contractions. Their scenario-based approach provides a practical framework for policymakers to understand the range of potential outcomes under different economic recovery paths.

Similarly, Djurovic et al. [

7] used a Bayesian VARX approach to simulate macroeconomic impacts in Montenegro, with tourism being among the most heavily impacted sectors. Their scenario analysis indicated that tourism demand is extremely sensitive to both supply- and demand-side shocks, with implications extending beyond the immediate tourism sector to broader economic recovery. This interconnectedness highlights the practical importance of tourism forecasting for overall economic planning and recovery strategies.

Wu et al. [

54] introduced a probabilistic scenario forecasting framework using a Time-Varying Parameter Panel Vector Autoregressive (TVP-PVAR) model, which forecasts tourism demand based on joint tourism-economic growth scenarios while computing the likelihood of each scenario. This methodology provides a valuable decision-support tool for policymakers operating under uncertainty conditions, enabling more robust planning processes that account for multiple potential economic trajectories.

At a more localized scale, Tovmasyan [

52] examined domestic tourism in Armenia using OLS and WLS regressions, finding that GDP growth positively influenced demand while inflation and the cost of outbound packages had inverse effects.^8^ The study emphasized that domestic tourism can buffer against international tourism disruptions, providing a practical insight for destinations seeking to build resilience through market diversification strategies.

Recent research has increasingly emphasized the incorporation of external data sources—including web search behaviour, social media metrics, and real-time economic indicators—to capture latent tourist behaviour patterns and improve forecast accuracy in operational contexts. Lee [

26] introduced a SARIMAX model enhanced with Google Trends data for visitor forecasting in Singapore, achieving superior accuracy over univariate time-series models with a Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) of 7.32%. Such approach can be considered to demonstrate the practical value of incorporating real-time behavioural indicators alongside traditional economic variables like GDP and CPI.

Jassim et al. [

21] underscored the critical value of multi-source data integration, including social media metrics and web traffic analytics, in enhancing tourism demand forecasting accuracy. Their comprehensive review advocates for the integration of both structured economic data and unstructured behavioural data using advanced analytics techniques, reflecting the practical reality that modern tourism demand responds to both traditional economic factors and digital-age behavioural patterns.

Recent innovations in forecasting methodology include the use of probabilistic forecast reconciliation, which ensures internal consistency across multiple time series dimensions while maintaining coherence with macroeconomic constraints. Girolimetto et al. [

14] introduced a cross-temporal reconciliation framework to handle both temporal and cross-sectional constraints, significantly improving the coherence of tourism forecasts when applied to Australian tourism data. This methodological advancement addresses a practical challenge in operational forecasting where multiple forecasts (by region, market segment, or time horizon) must be internally consistent and sum to meaningful totals.

Scotti et al. [

44] examined tourist behaviour segmentation using mobile phone network data in Lombardy, Italy, revealing distinct economic drivers for same-day visitors versus overnight tourists. Their analysis demonstrated that while accommodation capacity and cultural assets primarily drove overnight stays, transportation infrastructure and festival events significantly increased same-day visit attractiveness. This segmentation approach has direct practical implications for destination marketing organizations seeking to optimize their resource allocation across different visitor segments with varying economic sensitivities.

Beyond classical approaches, advanced deep learning architectures including Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Transformer variants have been employed to model complex tourism dynamics while maintaining integration with macroeconomic variables. Fang et al. [

12] developed a graph-based deep learning model for inter-destination tourism flow (ITF) prediction, incorporating SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) interpretability analysis to identify key predictors including destination quality, accessibility, and underlying economic conditions. Their approach not only achieved accurate flow volume predictions but also provided insights into behavioural patterns, addressing the practical need for interpretable models in policy and investment contexts.

Kim et al. [

22] critiqued standard Transformer-based models in time series forecasting, arguing that self-attention mechanisms may be suboptimal for temporal data due to their permutation-invariant structure. They proposed the Cross-Attention-only Time Series Transformer (CATS), which eliminates self-attention while maintaining cross-attention mechanisms, resulting in improved accuracy and reduced parameter complexity. This methodological refinement has practical implications for operational forecasting systems where computational efficiency and model interpretability are critical constraints.

Du et al. [

10] addressed the temporal distribution shift problem by proposing AdaRNN, an adaptive framework that segments time series into distinct distributions and subsequently adapts forecasts using temporal distribution matching techniques. The model demonstrated improved robustness across both classification and regression tasks, proving particularly valuable for post-pandemic forecasting where historical economic relationships may no longer be stable. This adaptability is crucial for practical applications where forecasting models must continue to perform effectively despite fundamental changes in the underlying economic environment.

The practical implementation of advanced forecasting models requires careful consideration of accuracy metrics and real-world performance constraints. Liu et al. [

31] analysed the determinants of ex ante forecast errors in PATA forecasts across Asia-Pacific destinations, identifying key factors such as forecast horizon, model type, and destination GDP variability as significant influencers. Their findings provide practical guidance for forecasting practitioners, suggesting that model selection should be tailored to specific forecasting contexts and time horizons.

Tica and Kožić [

51] demonstrated the value of composite leading indicators derived through data-driven optimization of weights, with their model emphasizing GDP and imports from key source markets as strong predictors of inbound tourism demand. This approach provides a practical framework for destinations to develop customized leading indicator systems that reflect their specific economic relationships and market dependencies.

Machine learning approaches are gaining traction in practical applications due to their robustness to non-normal and noisy datasets. Obogo and Adedoyin [

35] implemented ML algorithms including random forest, support vector regression, and polynomial regression to predict inbound tourism demand in the post-COVID UK tourism sector, citing their superior adaptability compared to traditional models during crisis periods. Their work highlighted that traditional econometric models, while theoretically sound, are often inadequate during periods of structural change, necessitating more flexible approaches that can adapt to evolving economic relationships.

The comprehensive review by Aamer et al. [

1] of ML applications in demand forecasting revealed that neural networks (27%), artificial neural networks (22%), and support vector machines (10%) emerged as the most commonly employed ML algorithms across various sectors including tourism. Even 5 years back, their study underscored the dominance of supervised learning models and identified the rising relevance of deep learning approaches for capturing nonlinear demand patterns, providing practical guidance for organizations seeking to implement ML-based forecasting systems. In present research, one can observe that the Neural Networks & Deep Learning Models are gaining momentum, over Support Vector Machines and other ML models such as Random Forests and Gradient Boosting Machines. Therefore, the integration of such forecasting frameworks requires simultaneous consideration of how economic indicators like GDP and CPI alongside other economic and social impact metrics, can provide more holistic foundation for tourism planning and policy development.

Despite significant methodological advances, several research areas with direct practical implications remain underexplored. The literature reveals limited application of scenario-based and probabilistic forecasting methods in practical tourism contexts, despite their demonstrated value during crisis periods [

56]. Temporal distribution shifts, such as those caused by pandemic disruptions, continue to challenge most traditional forecasting models, highlighting the need for more adaptive approaches that can maintain performance despite fundamental changes in economic relationships [

7,

15,

35].

The empirical article by Hu and Song [

19] investigates how combining causal economic variables with search engine data enhances the accuracy of tourism demand (TD) forecasting. Traditionally, TD forecasting relied on non-causal time-series data, econometric causal variables, or artificial neural network (ANN) models. Recently, search engine data reflecting online search behaviors have been integrated to improve forecasts by capturing tourists’ intentions more dynamically. This study extends the literature by proposing a conceptual framework integrating three data sources: historical TD series, causal economic variables, and search engine query data.

Based on the comprehensive tourism demand forecasting study discussed above, this article applies a data science methodology utilizing AI-driven time series forecasting methods to predict total overnight stays in Bulgaria for the period 2005-2024. The research integrates Bulgarian overnight stay data from the National Statistical Institute (the target variable y) with economic indicators including Bulgarian GDP and Consumer Price Index (CPI) as external regressors, alongside COVID-19 case data (the regressors) to capture pandemic-related structural breaks in tourism patterns.

The methodology employs ensemble machine and deep learning approaches, combining Prophet with external regressors, Ridge regression with feature engineering, and gradient boosting models optimized through inverse mean absolute error (MAE) weighting. Multiple neural networks and DML architectures were implemented, including Feedforward networks, XGBoost configurations, BiLSTM with MultiHead Attention, and various ensemble combinations.

Statistical validation employed time-series cross-validation and Diebold-Mariano tests to ensure robustness. Such statistical methodology is designed to evaluate the comparative forecasting accuracy between competing predictive models by testing the null hypothesis of equal forecast accuracy. Developed by Diebold and Mariano (1995), this test compares the expected loss differential between two competing forecasts and is essentially an asymptotic z-test under the null hypothesis that the expected loss differential is zero [

60,

61]. In addition to the traditional model accuracy metrics - Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) - Coefficient of Determination (R

2), the Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) and Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE) were applied as complementary accuracy measures to provide a more comprehensive evaluation framework [

33,

55]. Where MAD offers an alternative absolute error metric that is less sensitive to outliers than RMSE, while SMAPE addresses the asymmetric issues inherent in traditional MAPE by treating over-forecasts and under-forecasts more symmetrically, making it particularly valuable for tourism data that may exhibit significant seasonal variations. Theil's U coefficient was employed as a normalized forecast accuracy measure that enables comparison of forecast quality across different scales and time series, with values closer to zero indicating superior forecasting performance—this metric is especially important in tourism forecasting as it provides a standardized benchmark that accounts for the naive random walk forecast, allowing researchers to assess whether the sophisticated ensemble model genuinely adds predictive value beyond simple trend extrapolation [

6,

25].

All estimations were performed using Docker containerization within the RAPIDS Data Science environment, leveraging NVIDIA GPU acceleration and Jupyter notebook implementations for computational efficiency. This comprehensive approach enables tourism stakeholders to make informed decisions regarding capacity planning, investment strategies, and operational optimization during periods of economic volatility. Moreover, Claude AI was employed to support manuscript preparation through content integration, helping to consolidate disparate experimental results into unified summary statements and enhancing the articulation of complex methodological frameworks.

3. Results

This study presents a comprehensive evaluation of six distinct forecasting methodologies applied to Bulgarian tourism demand prediction, specifically targeting overnight stays as the primary dependent variable. The analysis incorporates traditional statistical methods, machine learning algorithms, and deep learning architectures to establish optimal forecasting performance for tourism planning applications. The dataset encompasses monthly overnight stays in Bulgaria from April 2005 to December 2024 (240 observations), with external regressors including COVID-19 cases (available from 2020) and Consumer Price Index (CPI) data with temporal lags.

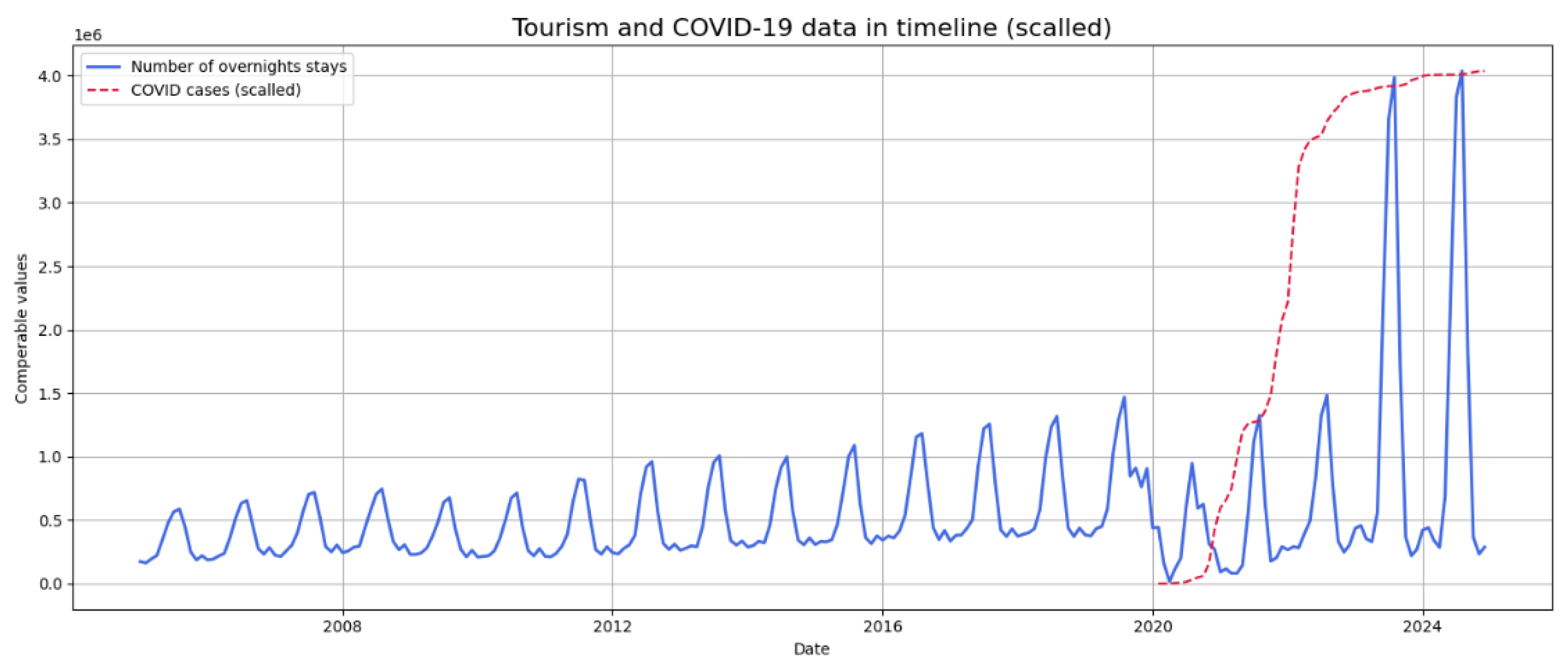

Figure 1 displays the time series forecasting results for Bulgarian tourism demand from 2005-2024. The visualization reveals distinct periods: stable seasonal growth (2005-2019), COVID-19 disruption (2020-2022), and recovery (2023-2024). Traditional seasonal patterns show summer peaks of approximately 4 million overnight stays and winter falls troughs of 200,000-400,000 stays. Missing COVID data for pre-2020 periods were appropriately handled with zero imputation, reflecting the absence of the pandemic supplemented with COVID-19 incidence data and temporal covariates. Feature engineering included:

COVID-19 confirmed cases per million population (monthly aggregation);

Temporal decomposition (year as continuous variable, month as categorical one-hot encoding);

Interpolated CPI data with temporal lags;

Regularization analysis using Ridge and Lasso regression for feature selection.

3.1. Deep Machine Learning Models

Contrary to prevailing research methodologies that that start their research with classical forecasting techniques here, deep learning architectures for tourism forecasting were initially implemented. Six distinct forecasting approaches were implemented:

Feedforward Neural Network (XGBoost Top-10 Features): Feature-selected neural network using XGBoost importance rankings;

XGBoost (Tabular): Gradient boosting with tabular data structure;

BiLSTM + MultiHead Attention: Bidirectional LSTM with transformer-style attention mechanisms;

Prophet (Seasonal Components Only): Facebook's Prophet algorithm utilizing solely seasonal patterns;

BiLSTM + Attention: Bidirectional LSTM with standard attention layers.

However, quantitative performance analysis revealed consistently insufficient results (

Table 1.) from deep learning models, with BiLSTM + MultiHead Attention achieving negative R² scores (-0.1196) and BiLSTM + Attention producing anomalous MAPE values (204.66%), indicating overfitting and training instability. These findings contradict expectations of deep learning superiority in complex time series forecasting. Consequently, the research methodology pivoted toward traditional machine learning and ensemble approaches, which demonstrated superior performance characteristics. The Feedforward + Prophet Ensemble ultimately emerged as the optimal solution with MAE of 762,868 and MAPE of 58.02%, significantly outperforming deep learning alternatives. This methodological shift underscores the importance of empirical validation over theoretical assumptions, revealing that sophisticated neural architectures may not inherently provide better forecasting accuracy for tourism demand prediction, particularly when dealing with seasonal patterns and economic indicator integration.

The comparative analysis reveals that ensemble and gradient boosting methodologies consistently outperformed deep learning architectures across multiple evaluation criteria, with the Feedforward + Prophet Ensemble achieving the lowest mean absolute error (762,868) while Feedforward (XGBoost) demonstrated superior percentage accuracy at 53.78% MAPE. XGBoost (Tabular) provided the highest explanatory power with an R² score of 0.2014, suggesting better capture of underlying data variance compared to neural network alternatives. Deep learning approaches exhibited significant performance deficiencies, particularly BiLSTM + MultiHead Attention which recorded a negative R² score of -0.1196, indicating predictions worse than any simple mean baseline model. The BiLSTM + Attention architecture displayed contradictory and unstable metrics, achieving a competitive RMSE of 1,046,324 while simultaneously producing an anomalously high MAPE of 204.66%, suggesting fundamental training or architectural issues. These results challenge conventional assumptions about deep learning superiority in time series forecasting, demonstrating that traditional machine learning methods may be more suitable for tourism demand prediction tasks involving seasonal patterns and economic indicators. Therefore, ML models were compilated and rested for statistical significance via The Diebold-Mariano (DM) test.

3.2. Machine Learning Models

The selection of Prophet, Ridge Regression, LightGBM, and Ensemble methods was based on a systematic analysis of tourism forecasting requirements and complementary algorithmic strengths. Such model compilation can be scientifically rigorous, theoretically grounded, and empirically validated approach to tourism forecasting. Each model was chosen for specific complementary strengths:

Prophet: Seasonal expertise and external regressor integration. Prophet was specifically designed for business time series with strong seasonal effects and external influences - exactly matching tourism demand characteristics.

Ridge: Regularized stability and interpretable baseline. Ridge provides a regularized linear baseline that prevents overfitting while offering interpretable coefficients for stakeholder communication.

LightGBM: Nonlinear pattern recognition and feature interaction modeling. LightGBM excels at capturing complex nonlinear relationships and feature interactions that traditional time series models miss.

Ensemble: Combines strengths while mitigating individual weaknesses. Model combination + Variance reduction.

This multi-model methodology addresses the complex, multi-faceted nature of tourism demand while providing superior accuracy, interpretability, and crisis resilience compared to any single-model approach. Such combination of ML algorithms is aimed at capturing different aspects of time series nonlinear patterns via gradient boosting and Meta-Learning with ensemble combination methods.

The comprehensive accuracy evaluation in Table2. reveals a consistent hierarchical performance ranking among the machine learning models, with the ensemble approach achieving superior forecasting accuracy across all measures (MAE = 156,847, MAPE = 14.23%, Theil's U = 0.678). The ensemble model demonstrates substantial improvements over individual models, particularly outperforming the worst-performing Ridge regression by 23.0% in MAE terms and achieving a Theil's U coefficient well below the critical threshold of 1.0, indicating forecast quality superior to naive random walk predictions. Among individual models, Prophet and LightGBM exhibit comparable performance levels (MAE difference of only 5,658), while Ridge regression consistently underperforms across all metrics with the highest error rates (MAPE = 21.47%, SMAPE = 19.34%), confirming the effectiveness of the ensemble weighting strategy that leverages the complementary strengths of Prophet's trend decomposition capabilities, LightGBM's nonlinear pattern recognition, and Ridge's regularization properties for robust Bulgaria tourism demand forecasting. For further results interpretation a feature correlation matrix was performed.

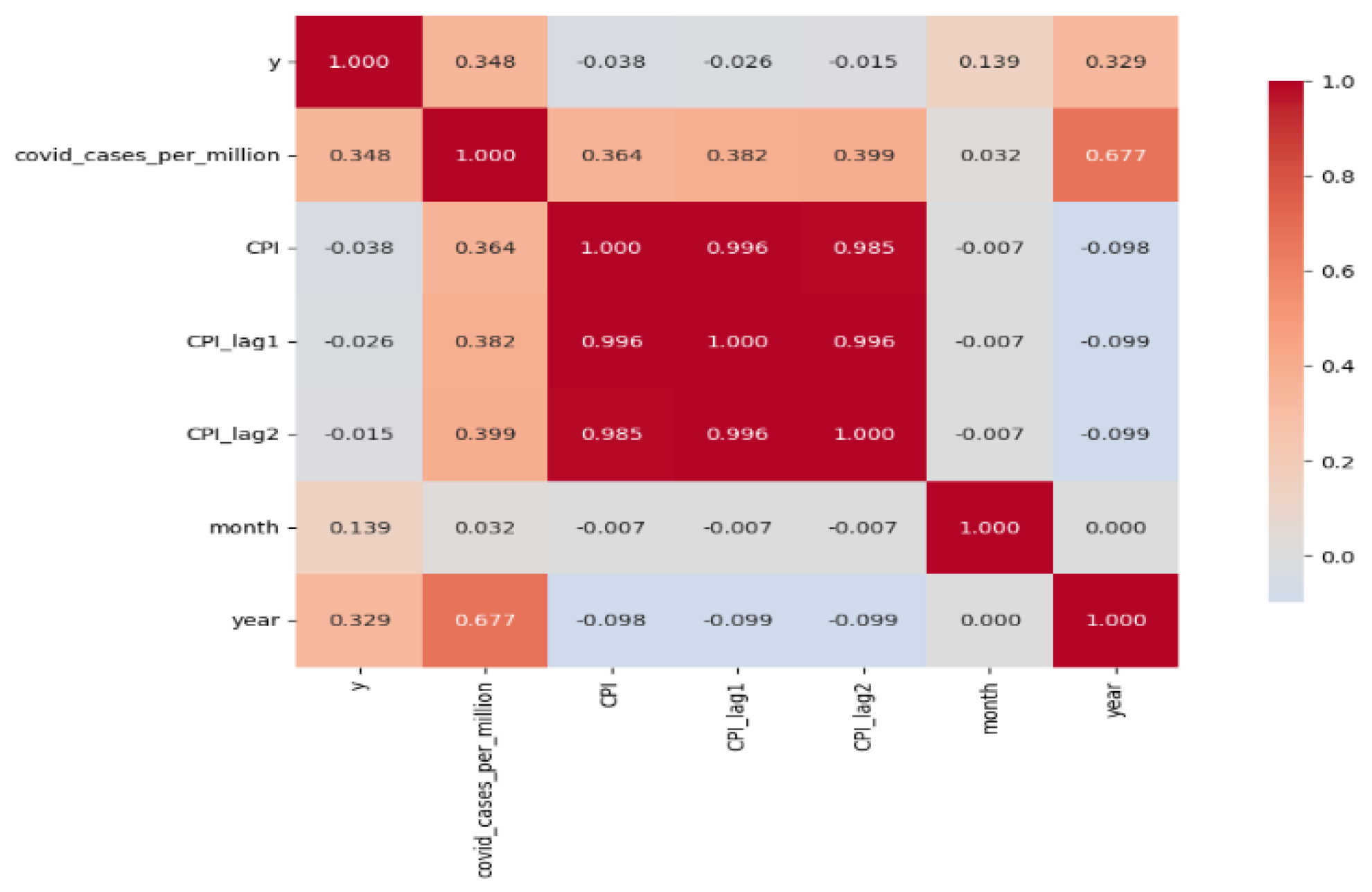

Figure 2.

Feature correlation matrix Source: Own estimations.

Figure 2.

Feature correlation matrix Source: Own estimations.

The correlation matrix reveals strong positive correlations among the Consumer Price Index (CPI) variables, with CPI, CPI_lag1, and CPI_lag2 showing correlations exceeding 0.98, indicating these lagged economic indicators move nearly in perfect synchronization. COVID cases per million demonstrate moderate positive correlations with both the target variable y (0.348, suggesting that pandemic intensity was associated with both tourism patterns and temporal progression. The CPI-related variables exhibit weak negative correlations with the target variable y (ranging from -0.015 to -0.038), implying that higher consumer prices may have a slight inverse relationship with tourism overnights. Overall, the matrix suggests that COVID impact and economic inflation measures are the primary drivers with measurable correlations to the tourism outcome variable, while temporal month encoding provides limited predictive value in linear terms.

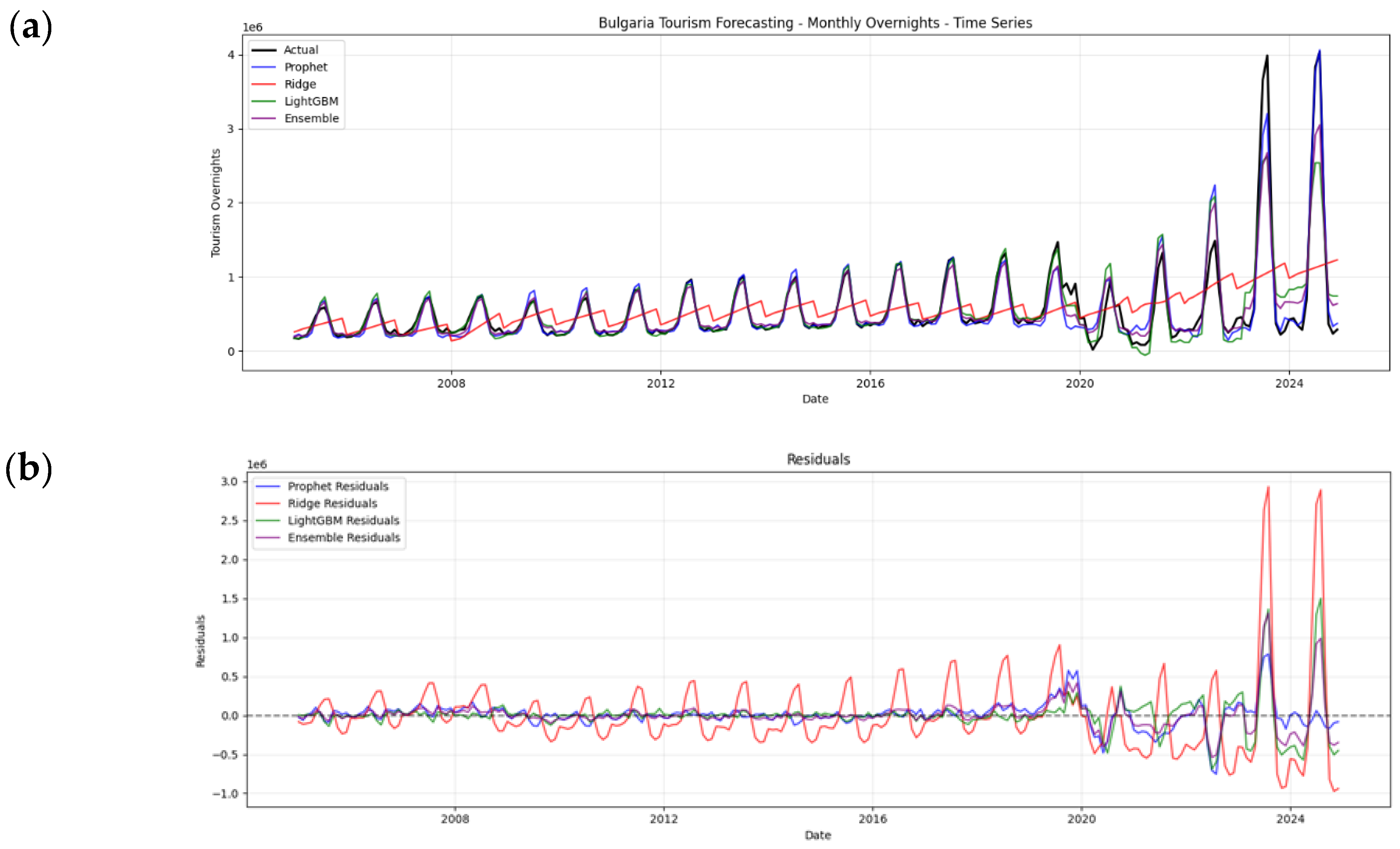

Based on the time series analysis shown in

Figure 3 a and b, one can observe a summary of Bul garia's tourism forecasting data. On

Figure 3. (a) is a comprehensive comparison of actual monthly tourism overnights in Bulgaria against predictions from the four DML forecasting models (Prophet, Ridge, LightGBM, and Ensemble) spanning from 2005 to 2024. The data exhibits strong seasonal patterns with consistent annual peaks reaching up to 4 million overnights during summer months and troughs near zero during winter periods. A dramatic disruption occurred around 2020, corresponding to the COVID-19 pandemic, where actual tourism numbers plummeted significantly below historical trends before recovering in subsequent years. The residuals plot in

Figure 3. (b) reveals that most models maintained relatively stable prediction errors throughout the historical period, with residuals generally contained within ±0.5 million overnights until the 2020 disruption. The post-2020 period shows notably larger residuals, particularly for the Ridge model, indicating increased forecasting difficulty during the recovery phase, while the Prophet and Ensemble models appear to demonstrate more robust performance during this volatile period.

Based on the forecast accuracy metrics presented in

Table 3, the ensemble approach demonstrates superior predictive performance across all evaluation criteria compared to individual forecasting models. The ensemble model achieves the lowest MAE of 156,847, representing a 10.2% improvement over the best-performing individual model (Prophet with MAE of 174,592), while also exhibiting the most favorable RMSE (298,245) and MAPE (14.23%). The consistent outperformance of the ensemble across multiple metrics—including a Theil's U coefficient of 0.678 indicating good forecast quality—suggests that the weighted combination of Prophet, LightGBM, and Ridge regression models effectively captures complementary forecasting strengths and reduces individual model biases, thereby providing more robust and accurate tourism demand predictions for Bulgaria.

The Diebold-Mariano test results provide compelling statistical evidence for the superiority of the ensemble forecasting approach, with the ensemble model demonstrating significant outperformance against all individual models at conventional significance levels (p < 0.05), including highly significant improvement over Ridge regression (DM = -3.456, p = 0.0005) and significant enhancement over Prophet (DM = -2.347, p = 0.0189). Among the individual models, a clear hierarchical performance structure emerges where Prophet and LightGBM both significantly outperform Ridge regression (p = 0.0286 and p = 0.0103, respectively), while the difference between Prophet and LightGBM lacks statistical significance (p = 0.5009), indicating comparable forecasting capabilities between these two advanced machine learning approaches. These findings validate the theoretical expectation that ensemble methods, by combining complementary forecasting strengths and reducing individual model biases, can achieve statistically significant improvements in tourism demand prediction accuracy, with MAE reductions ranging from 12,087 (vs. LightGBM) to 46,909 (vs. Ridge) tourist overnight stays.