1. Introduction

Podocalyxin (PODXL) is a transmembrane glycoprotein that belongs to the CD34 family [

1]. The core protein of PODXL has a molecular weight of approximately 53,000 and undergoes extensive post-translational modifications such as

N- and

O-linked glycosylation, resulting in a mature glycoprotein with an apparent molecular weight ranging from 150,000 to 200,000 [

2]. Under physiological conditions, PODXL is expressed in early hematopoietic progenitors [

3], kidney podocytes [

4], and vascular/lymphatic endothelial cells in adults [

5]. PODXL has been implicated in the maintenance of homeostasis, and PODXL-deficient mice exhibit embryonic lethality [

6]. Notably, aberrant overexpression of PODXL has been documented across a wide spectrum of human malignancies, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) [

7], renal cell carcinoma [

8], colorectal cancer [

9], breast cancer [

10], and oral squamous cell carcinoma [

11]. Elevated expression of PODXL is significantly correlated with poor disease-free survival, cancer-specific survival, and overall survival in colorectal cancer, PDAC, renal cell carcinoma, urothelial bladder cancer, and glioblastoma multiforme [

12].

PODXL expression is markedly upregulated during the process of epithelial–mesenchymal transition [

13]. PODXL plays a pivotal role in facilitating the extravasation of mesenchymal-type PDAC cells [

14]. Mechanistically, PODXL promotes the extravasation through direct interaction with ezrin, a cytoskeletal linker protein. The PODXL and ezrin interaction has been reported to stimulate intracellular signal transductions including mitogen-activated protein kinase, phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase, RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 pathways to promote motility [

15]. Morphologically, the interaction supports the transition of tumor cells from a non-polarized and rounded phenotype to an invasive, extravasation-competent state [

14]. These findings implicate PODXL as a key mediator of tumor cell extravasation during the metastatic cascade. However, the involvement of endothelial PODXL ligand, such as E-selectin [

16] in this process remains to be elucidated. Studies involving both gain- and loss-of-function approaches have demonstrated that PODXL plays a critical role in tumor progression by enhancing cellular migration, invasiveness, stem cell-like properties, and metastasis across diverse cancer types [

17]. Consequently, PODXL has emerged as a promising candidate for targeted tumor immunotherapy.

We previously generated an anti-PODXL monoclonal antibody (mAb), PcMab-47 (mouse IgG

1, κ), which has proven to be effective for applications, such as flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry [

18]. To enhance its effector functions, PcMab-47 was engineered into a mouse IgG

2a isotype, designated 47-mG

2a, thereby conferring antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity. Furthermore, to potentiate ADCC, a core fucose-deficient variant of 47-mG

2a, termed 47-mG

2a-f, was developed. Both 47-mG

2a and 47-mG

2a-f demonstrated significant antitumor activity in mouse xenograft models of oral squamous cell carcinomas [

19]. In addition, we constructed a mouse–human chimeric version of PcMab-47 (chPcMab-47), which exhibited therapeutic efficacy against colorectal adenocarcinoma xenografts [

20]. Other preclinical studies of anti-PODXL mAbs have also shown promising antitumor efficacy. A clone PODO83/PODOC, core protein-binding anti-PODXL mAb, suppressed breast cancer MDA-MB-231 xenograft growth and blocked the lung metastasis [

21].

Despite the therapeutic potential of anti-PODXL mAbs, their further development has been limited by concerns regarding potential on-target off-tumor toxicities, particularly to normal kidney podocytes [

4] as well as vascular and lymphatic endothelial cells. To minimize adverse effects on normal tissues, the development of cancer-specific mAbs (CasMabs) against PODXL is essential.

To address the challenge of tumor-specific targeting, we have developed CasMabs against various antigens to identify cancer-specific epitopes and elucidate their recognition mechanisms. In the case of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), over 300 anti-HER2 mAb clones were generated by immunizing mice with cancer cell-expressed HER2 and screened via flow cytometry for selective reactivity. Among them, H

2CasMab-2 (H

2Mab-250) selectively recognized HER2 on breast cancer cells but not on normal epithelial cells from mammary gland [

22]. Epitope mapping revealed that Trp614 in the extracellular domain 4 of HER2 is essential for its binding [

22]. A mouse IgG

2a or a humanized H

2CasMab-2 exhibited potent ADCC, complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and antitumor activity in breast cancer xenograft models [

23,

24,

25]. Additionally, a single-chain variable fragment derived from H

2CasMab-2 was applied to CAR-T cell therapy, demonstrating cancer-specific recognition and cytotoxicity [

26]. A phase I clinical trial targeting HER2-positive advanced solid tumors is currently ongoing in the United States (NCT06241456). These findings highlight the importance of CasMab selection and epitope specificity in the development of effective therapeutic antibodies and related immunotherapies.

Using same strategy, we established a cancer-specific anti-PODXL mAb, PcMab-60 (IgM, κ), through the screening of over one hundred hybridoma clones. In flow cytometry, PcMab-60 reacted with the PODXL-overexpressed LN229 and pancreatic cancer MIA PaCa-2. In contrast, PcMab-60 did not recognize normal endothelial cells [

27]. The epitope of PcMab-60 was demonstrated to be a peptide sequence in PODXL [

28].

In this study, we engineered PcMab-60 into a humanized IgG1-type mAb (humPcMab-60) and examined the antitumor activity against mouse xenograft models of PDAC and colorectal cancer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines

The human colorectal carcinoma cell line Caco-2 and the Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1 cell line were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). PDAC cell lines, PK-45H and MIA PaCa-2, were provided by the Cell Resource Center for Biomedical Research, Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Tohoku University (Miyagi, Japan). The human lymphatic endothelial cell line HDMVEC/TERT164-B was purchased from EVERCYTE (Vienna, Austria) and cultured using the Endopan MV kit (PAN Biotech, Bayern, Germany) supplemented with G418. MIA PaCa-2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). CHO-K1, CHO/PODXL [

18], and PK-45H cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). All culture media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO

2 and 95% air.

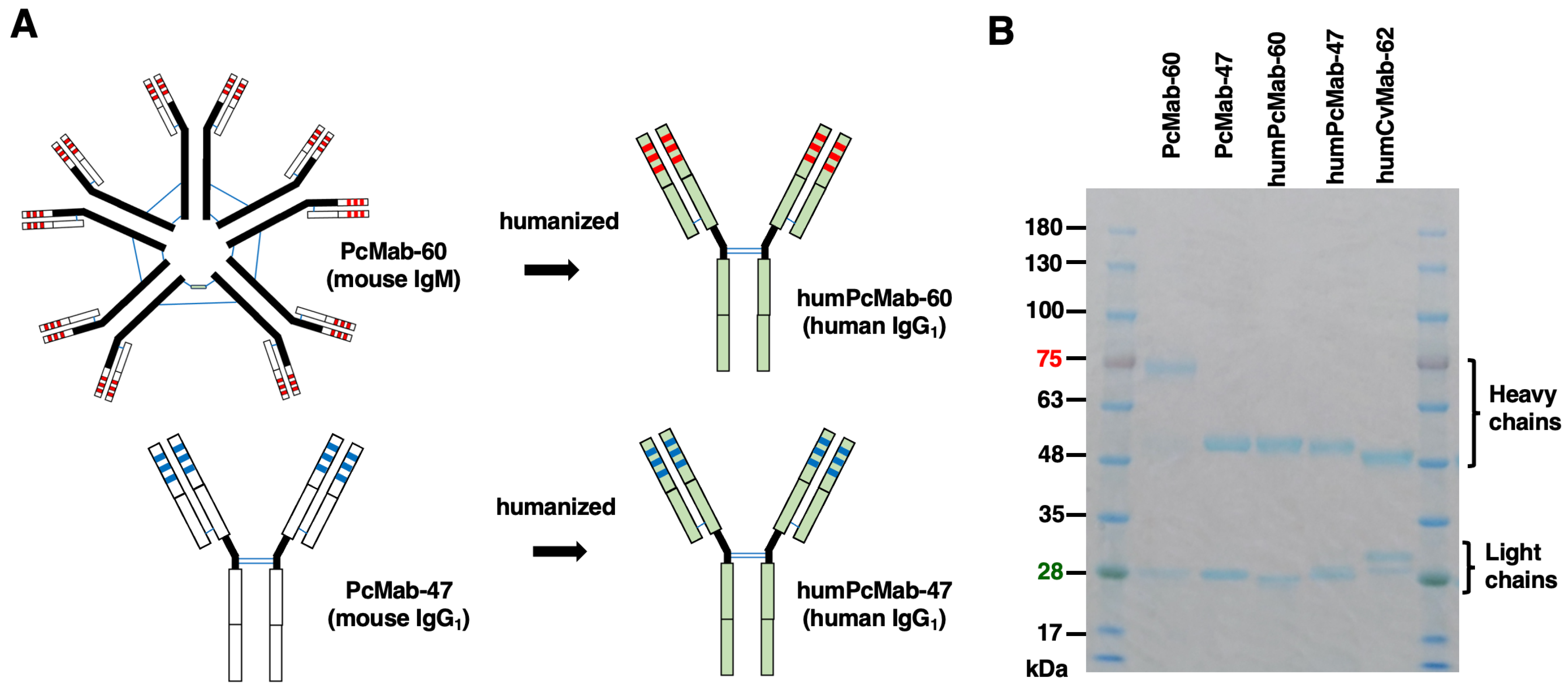

2.2. Recombinant Antibody Production

Mouse anti-PODXL mAbs, PcMab-47 (IgG

1, kappa) [

18] and PcMab-60 (IgM, kappa) [

28], were generated as previously described. To construct the humanized versions, humPcMab-47 and humPcMab-60, the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of the variable heavy (V

H) chains of PcMab-47 or PcMab-60 were grafted onto human IgG framework sequences and cloned into the pCAG-Neo expression vector along with the constant region (C

H) of human IgG

1. Similarly, the CDRs of the variable light (V

L) chains, the human IgG framework sequences of V

L, and the constant region of the human kappa light chain (C

L) were cloned into the pCAG-Ble vector. Antibody expression vectors were transfected into ExpiCHO-S cells using the ExpiCHO Expression System to produce humPcMab-47 and humPcMab-60. As a control human IgG

1 (hIgG

1) mAb, humCvMab-62 was generated from CvMab-62, an anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein S2 subunit mAb, using the same procedure. All antibodies were purified using Ab-Capcher (ProteNova Co., Ltd., Kagawa, Japan).

2.3. Flow Cytometry

Cell lines were harvested via brief exposure to 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Nacalai Tesque, Inc.)/0.25% trypsin. After washing with 0.1% BSA in PBS (blocking buffer), the cells were treated with primary mAbs for 30 min at 4 ◦C, followed by treatment with anti-human IgG conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (1:1000; Sigma-Aldrich Corp.). Fluorescence data were collected using an SA3800 Cell Analyzer (Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. ADCC

The ADCC activity of humPcMab-60 was assessed as follows. Calcein AM-labeled target cells (CHO/PODXL, MIA PaCa-2, PK-45H, and Caco-2) were co-incubated with human natural killer (NK) cells (Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan) at an effector-to-target (E:T) ratio of 50:1 in the presence of 100 μg/mL of either control hIgG1 or humPcMab-60. Following a 4.5-hour incubation, the release of Calcein into the supernatant was quantified using a microplate reader (Power Scan HT; BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Cytotoxicity was calculated as a percentage of lysis using the following formula: % lysis = (E − S)/(M − S) × 100, where E represents the fluorescence intensity from co-cultures of effector and target cells, S denotes the spontaneous fluorescence from target cells alone, and M corresponds to the maximum fluorescence obtained after complete lysis using a buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM EDTA, and 0.5% Triton X-100. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was evaluated using a two-tailed unpaired t-test.

2.5. CDC

The Calcein AM-labeled target cells (CHO/PODXL, MIA PaCa-2, PK-45H, and Caco-2) were plated and mixed with rabbit complement (final dilution 15%, Low-Tox-M Rabbit Complement; Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, ON, Canada) and 100 μg/mL of control hIgG1 or humPcMab-60. Following incubation for 4.5 h at 37 °C, the Calcein release into the medium was measured, as described above.

2.6. Antitumor Activity of humPcMab-60

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Committee for Animal Experiments of the Institute of Microbial Chemistry (Numazu, Japan; approval number: 2025-002). Humane endpoints for euthanasia were defined as a body weight loss exceeding 25% of the original weight and/or a maximum tumor volume greater than 3,000 mm3.

Female BALB/c nude mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory Japan, Inc. Tumor cells (0.3 mL of a 1.33 × 108 cells/mL suspension in DMEM) were mixed with 0.5 mL of BD Matrigel Matrix Growth Factor Reduced (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). A 100 μL aliquot of the mixture, containing 5 × 106 cells, was subcutaneously injected into the left flank of each mouse. To evaluate the antitumor activity of humPcMab-60, 100 μg of humPcMab-60 or control hIgG1 diluted in 100 μL of PBS was administered intraperitoneally to tumor-bearing mice on day 7 post-inoculation. A second dose was administered on day 14. In addition, human NK cells (5 × 105 cells) were injected peritumorally on both days 7 and 14. Mice were euthanized on day 21 following tumor cell implantation.

Tumor size was measured, and volume was calculated using the formula: volume = W2 × L / 2, where W represents the short diameter and L the long diameter. Data are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s post hoc test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

PODXL has been a candidate of therapeutic target and diagnostic biomarker in PDAC and colorectal cancers, since the high PODXL expression is a potential indicator of poor prognosis [

12,

15]. PODXL could be detected in peripheral blood and used as a non-invasive diagnostic biomarker for the detection of PDAC [

29]. In this study, we demonstrated that a humanized anti-PODXL CasMab, humPcMab-60 could be a promising mAb-based tumor therapy. The humPcMab-60 retains the cancer-specific reactivity (

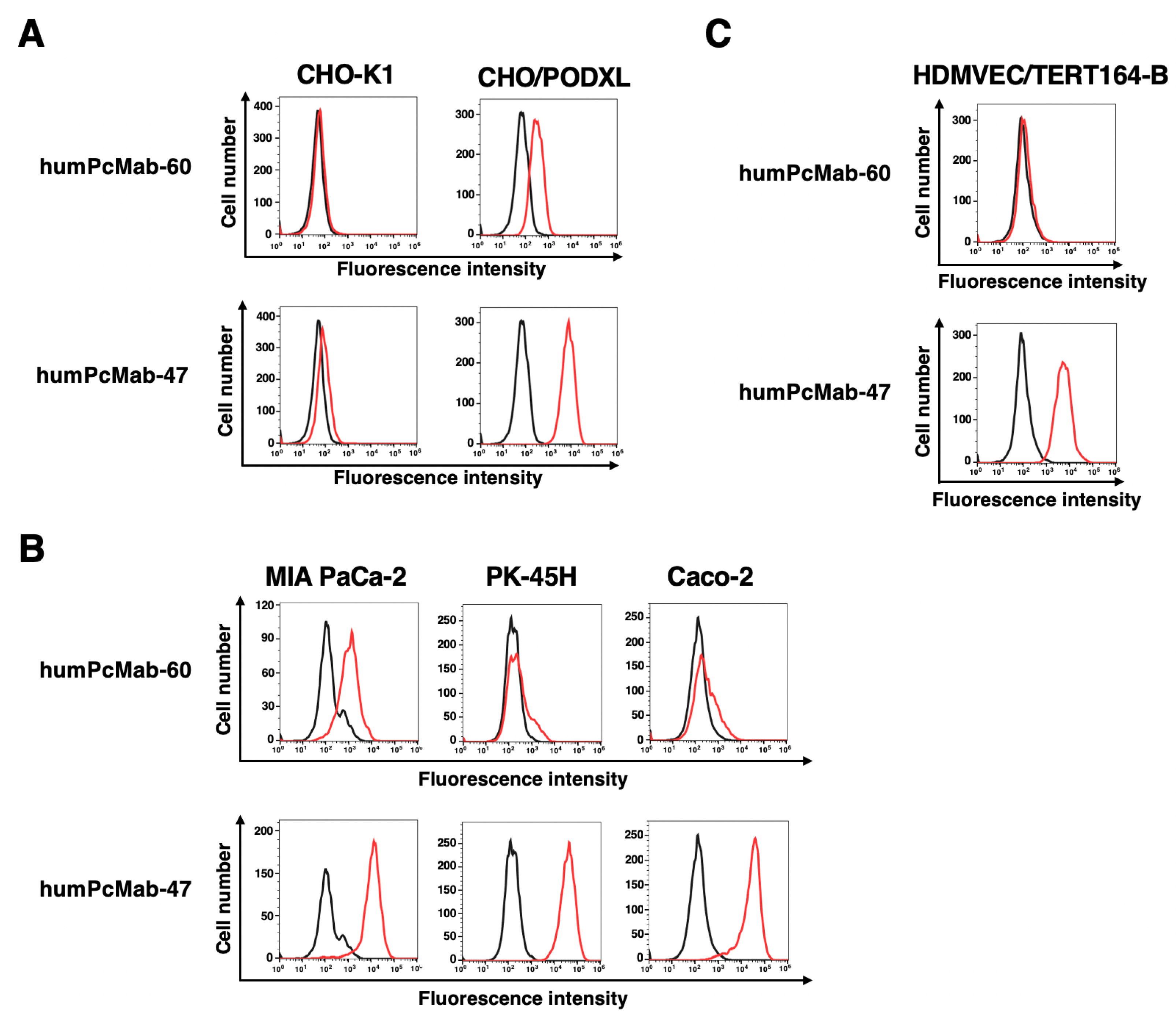

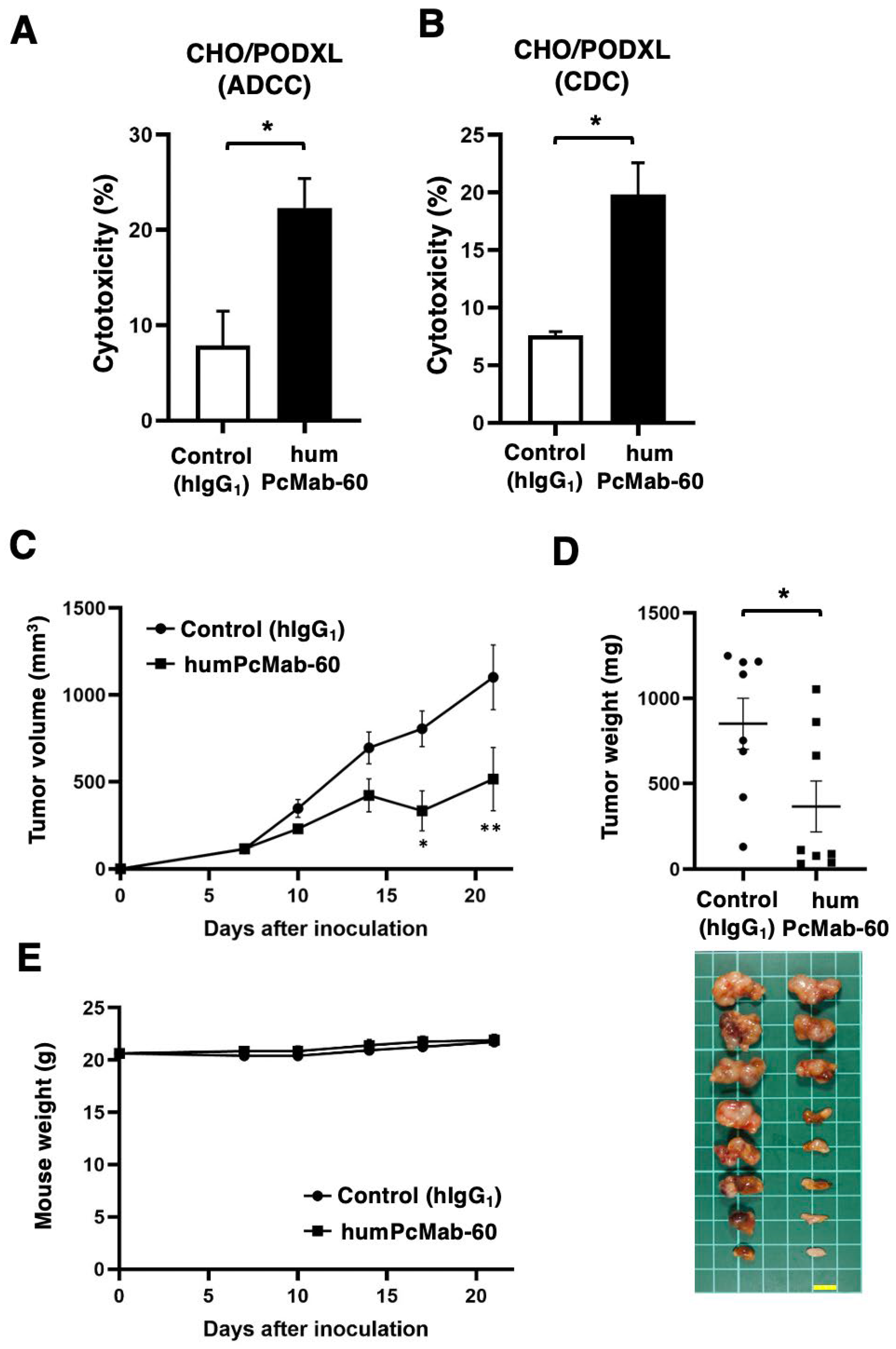

Figure 2), exerted ADCC and CDC (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4), and showed the antitumor effect against xenograft tumors of CHO/PODXL (

Figure 3), PDAC, and colorectal cancers (

Figure 5).

As of 2025, pancreatic cancer ranks as the fourth (for men) or third (for women) leading sites of estimated new cancer deaths in the United States [

30]. PDAC is the common type of pancreatic cancer and is associated with an exceptionally poor prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 10% [

31]. The most frequent oncogenic alterations—mutations in KRAS, CDKN2A, SMAD4, and TP53—are key drivers of PDAC pathogenesis [

32,

33]. Despite these common molecular events, PDAC represents a highly heterogeneous disease characterized by diverse histopathological features [

34], molecular profiles [

35], and clinical outcomes. Further investigation is required to determine the specific subtype(s) of pancreatic cancer in which PODXL is expressed.

Colorectal cancer ranks as the third (for men) or fourth (for women) leading sites of estimated new cancer deaths in the United States [

30]. PODXL was identified as a target gene of β-catenin, which is frequently activated in colorectal cancer [

36]. Furthermore, PODXL was upregulated by radiotherapy in both colorectal cancer tissues and cultured cells [

37]. The radiation-induced PODXL promoted the lamellipodia formation, migration, and invasiveness of colorectal cancer cells [

37]. Therefore, humPcMab-60 could be used in the combination therapy with radiotherapy.

Although humPcMab-60 exhibited the antitumor effects in vivo (

Figure 3 and

Figure 5), the reactivity of humPcMab-60 to CHO/PODXL, MIA PaCa-2, PK-45H, and Caco-2 was lower than that of a non-CasMab, humPcMab-47 (

Figure 2). Similar phenomenon was observed in H

2CasMab-2 (H

2Mab-250), a CasMab against HER2. We found that H

2CasMab-2 differentially recognizes locally misfolded HER2 expressed on tumor cells compared with trastuzumab. By disruption of HER2 protein folding by dithiothreitol, HER2 recognition by H

2CasMab-2 was significantly enhanced. In contrast, HER2 recognition by trastuzumab was significantly reduced [

26]. We also determined a structure of H

2CasMab-2 variable region complexed with an epitope peptide (amino acids 611–618) of HER2. In the native state, this region of HER2 adopts an extended conformation, forming part of a β sheet [

38,

39]. Instead, when bound by H

2CasMab-2, amino acids 611–618 undergo a bent conformation with little similarity to the native state [

26]. Therefore, further studies are required to investigate whether humPcMab-60 recognizes the misfolded structure of PODXL and clarify the structure of humPcMab-60-PODXL complex. We already determined the epitope of PcMab-60 as a peptide sequence (

109-RGGGSGNP

-116) in PODXL [

28].

Aberrant glycosylation is a hallmark of malignancies and contributes to the generation of tumor-specific glycosylated epitopes [

40]. PODXL-targeting mAbs that selectively recognize cancer-associated glycosylated epitopes, while sparing PODXL expressed on normal tissues, have been developed [

41]. Among these, PODO447 demonstrates remarkable specificity for a tumor-associated glycosylated epitope of PODXL and does not cross-react with normal adult human tissues. Epitope mapping using glycosylation-deficient cell lines identified the recognized epitope as an

O-linked core 1 glycan presented in the structural context of the PODXL polypeptide backbone [

41]. The PcMab-60 epitope (

109-RGGGSGNP

-116) can be modified by

N- and/or

O-glycosylation. PcMab-60 can recognize a non-glycosylated synthesized peptide in enzyme-linked immuno-sorbent assay and surface plasmon resonance analysis [

28]. In contrast, the epitope of PcMab-47 was determined to be

207-DHLM

-210 [

42]. Further analyses of glycosylation at these sites are needed. Moreover, the difference of glycosylation in between cancer and normal cells and/or between cultured cells and the xenograft should be investigated to clarify the mechanism of cancer-specific recognition by PcMab-60.

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs), recognized as initiators of metastasis, are present in the bloodstream either as individual cells or as multicellular clusters, the latter of which demonstrate significantly higher metastatic potential than single CTCs [

43]. PODXL is known to facilitate CTC cluster formation [

44]. PODXL expression was found to be elevated in CTC clusters compared to single CTCs isolated from blood samples of breast cancer patients [

45]. Furthermore, genetic silencing of PODXL or treatment with an anti-PODXL mAb markedly suppressed tumor cell clustering in vivo and effectively inhibited metastatic colonization following intravenous injection into mice [

44]. It is worthwhile to investigate whether humPcMab-60 can recognize PODXL on the CTC cluster and reduce the metastatic colonization in the mouse model.

Notably, loss of terminal sialylation in glycoproteins within CTC clusters contributes to cellular dormancy, facilitates resistance to chemotherapy, and enhances metastatic potential [

44]. PODXL knockdown reversed the tumor cell aggregation induced by the knockout of β-galactoside α2,6-sialyltransferase 1 (ST6GAL1) [

44], which catalyzes the addition α2,6-sialic acid onto terminal glycans on glycoproteins [

46]. These results suggest that PODXL is a potential target for counteracting the metastasis of quiescent tumor cells. We have developed more than one hundred anti-PODXL hybridoma clones (PcMabs) and a part of PcMabs has been updated at Antibody Bank (

http://www.med-tohoku-antibody.com/topics/001_paper_antibody_PDIS.htm). Our PcMabs, including PcMab-60, may contribute to the identification of quiescent PODXL-positive tumor cells and the development of therapeutic application to target those cells.

Figure 1.

Production of humPcMab-60. (A) Human IgG1 mAbs, humPcMab-60 and humPcMab-47, were generated from PcMab-60 (mouse IgM) and PcMab-47 (mouse IgG1), respectively. (B) PcMab-60, PcMab-47, humPcMab-60, humPcMab-47, and humCvMab-62 were treated with sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated on a polyacrylamide gel. The gel was stained with Bio-Safe CBB G-250 Stain.

Figure 1.

Production of humPcMab-60. (A) Human IgG1 mAbs, humPcMab-60 and humPcMab-47, were generated from PcMab-60 (mouse IgM) and PcMab-47 (mouse IgG1), respectively. (B) PcMab-60, PcMab-47, humPcMab-60, humPcMab-47, and humCvMab-62 were treated with sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated on a polyacrylamide gel. The gel was stained with Bio-Safe CBB G-250 Stain.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of humPcMab-60 and humPcMab-47 to tumor and normal cells. CHO-K1 and CHO/PODXL (A), PDAC cell lines (MIA PaCa-2 and PK-45H) and colorectal cancer cell line (Caco-2) (B), and a lymphatic endothelial cell line (HDMVEC/TERT164-B) (C) were treated with 10 µg/mL of humPcMab-60 or humPcMab-47. Then, the cells were treated with FITC-conjugated anti-human IgG. Fluorescence data were analyzed using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 2.

Flow cytometry analysis of humPcMab-60 and humPcMab-47 to tumor and normal cells. CHO-K1 and CHO/PODXL (A), PDAC cell lines (MIA PaCa-2 and PK-45H) and colorectal cancer cell line (Caco-2) (B), and a lymphatic endothelial cell line (HDMVEC/TERT164-B) (C) were treated with 10 µg/mL of humPcMab-60 or humPcMab-47. Then, the cells were treated with FITC-conjugated anti-human IgG. Fluorescence data were analyzed using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

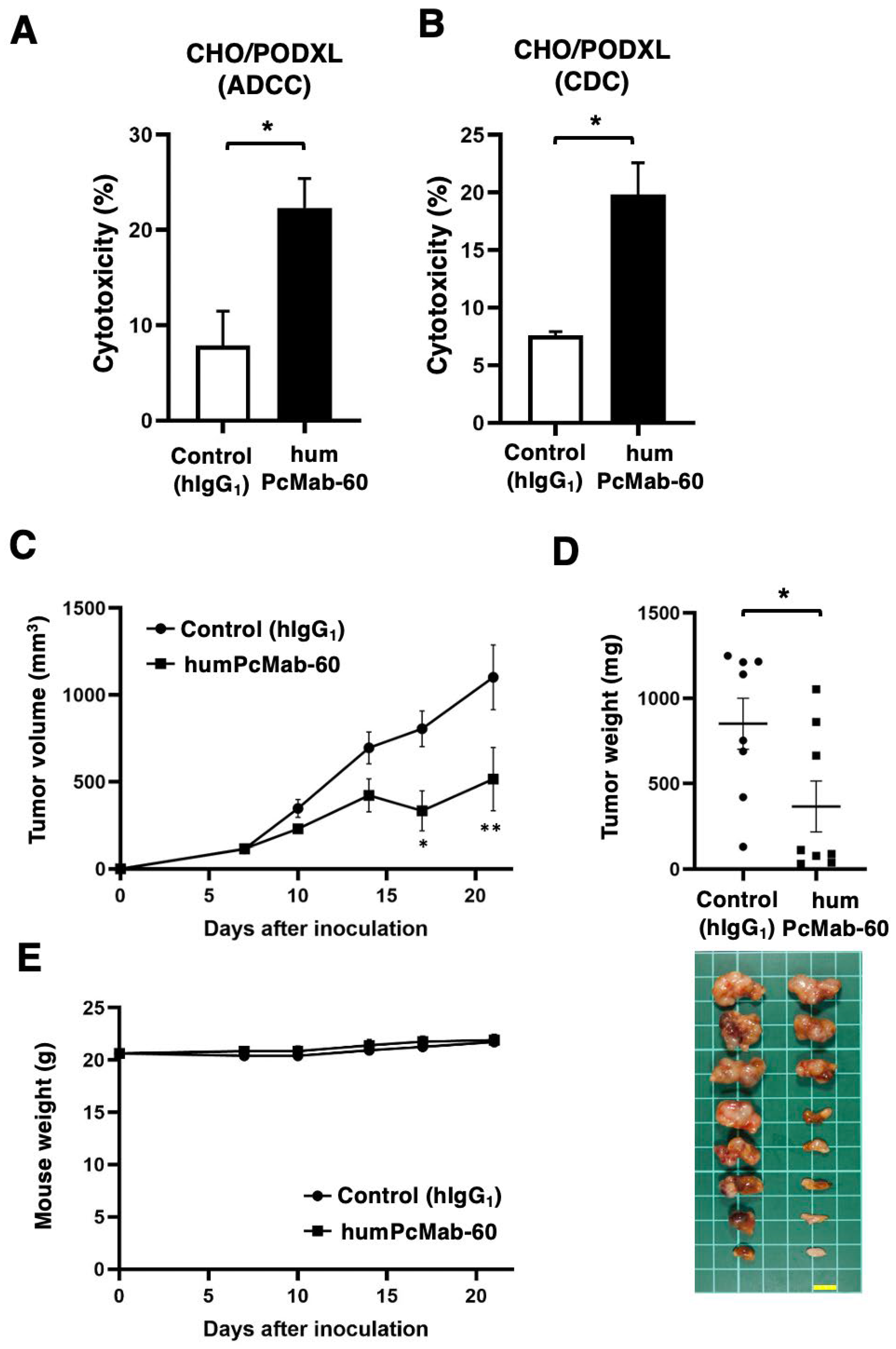

Figure 3.

ADCC, CDC, and an antitumor effect by humPcMab-60 against CHO/PODXL. (A) ADCC induced by humPcMab-60 or control human IgG1 (hIgG1) against CHO/PODXL. (B) CDC induced by humPcMab-60 or hIgG1 against CHO/PODXL. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05; Two-tailed unpaired t test). (C) An antitumor activity of humPcMab-60 against CHO/PODXL xenografts. CHO/PODXL was subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice (day 0). In total, 100 μg of humPcMab-60 or hIgG1 were intraperitoneally injected into each mouse on day 7. Additional antibodies were injected on days 14. The tumor volume is represented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 (ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (D) The mice were euthanized on day 21. The tumor weights were measured. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 (Two-tailed unpaired t test). (E) Body weights of the xenograft-bearing mice treated with humPcMab-60 or hIgG1. There is no statistical difference.

Figure 3.

ADCC, CDC, and an antitumor effect by humPcMab-60 against CHO/PODXL. (A) ADCC induced by humPcMab-60 or control human IgG1 (hIgG1) against CHO/PODXL. (B) CDC induced by humPcMab-60 or hIgG1 against CHO/PODXL. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05; Two-tailed unpaired t test). (C) An antitumor activity of humPcMab-60 against CHO/PODXL xenografts. CHO/PODXL was subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice (day 0). In total, 100 μg of humPcMab-60 or hIgG1 were intraperitoneally injected into each mouse on day 7. Additional antibodies were injected on days 14. The tumor volume is represented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 (ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (D) The mice were euthanized on day 21. The tumor weights were measured. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 (Two-tailed unpaired t test). (E) Body weights of the xenograft-bearing mice treated with humPcMab-60 or hIgG1. There is no statistical difference.

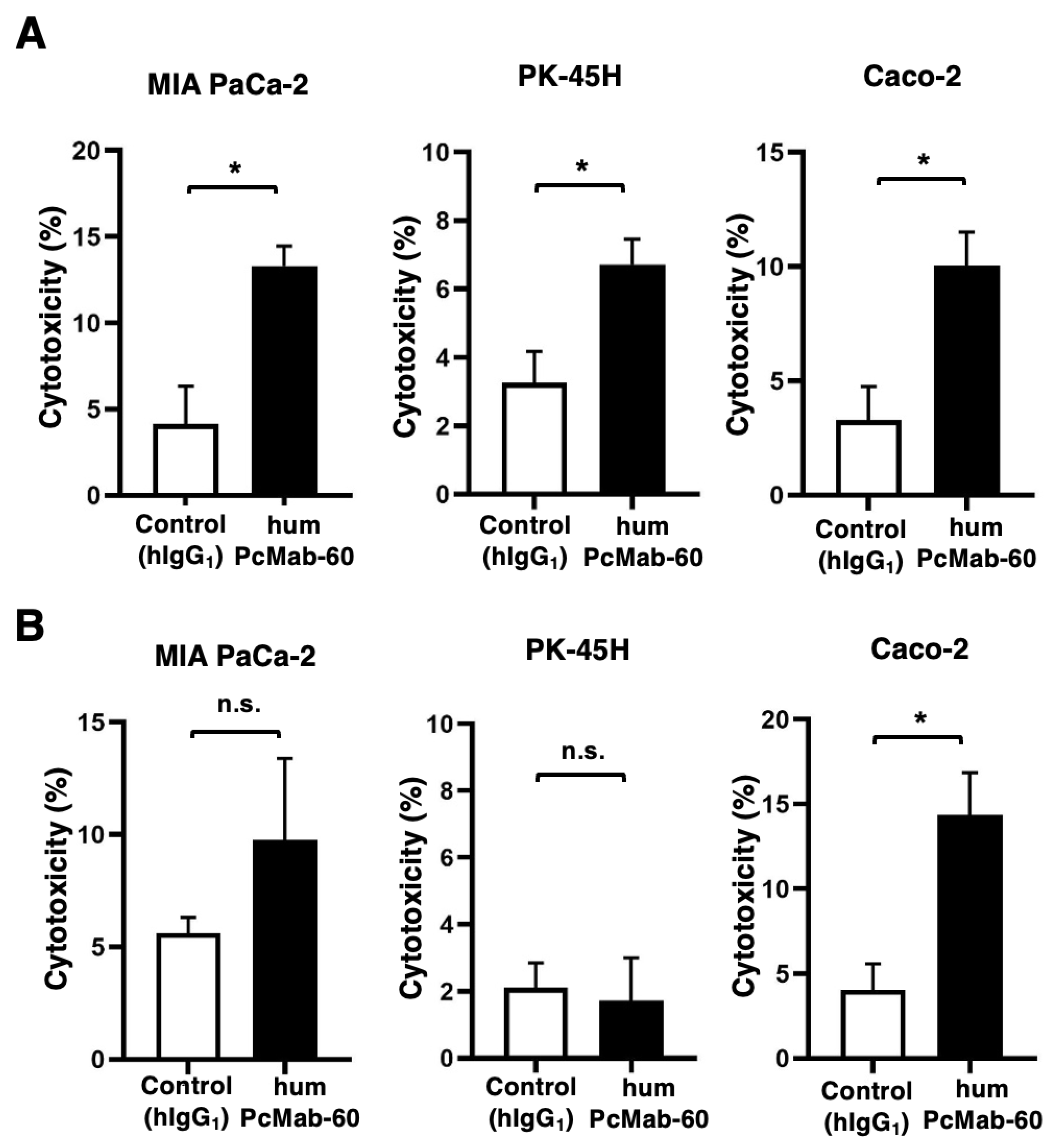

Figure 4.

ADCC and CDC by humPcMab-60 against human cancer cell lines. (A) ADCC induced by humPcMab-60 or control human IgG1 (hIgG1) against MIA PaCa-2, PK-45H, and Caco-2. (B) CDC induced by humPcMab-60 or hIgG1 against MIA PaCa-2, PK-45H, and Caco-2. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05; Two-tailed unpaired t test). n.s., not significant.

Figure 4.

ADCC and CDC by humPcMab-60 against human cancer cell lines. (A) ADCC induced by humPcMab-60 or control human IgG1 (hIgG1) against MIA PaCa-2, PK-45H, and Caco-2. (B) CDC induced by humPcMab-60 or hIgG1 against MIA PaCa-2, PK-45H, and Caco-2. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05; Two-tailed unpaired t test). n.s., not significant.

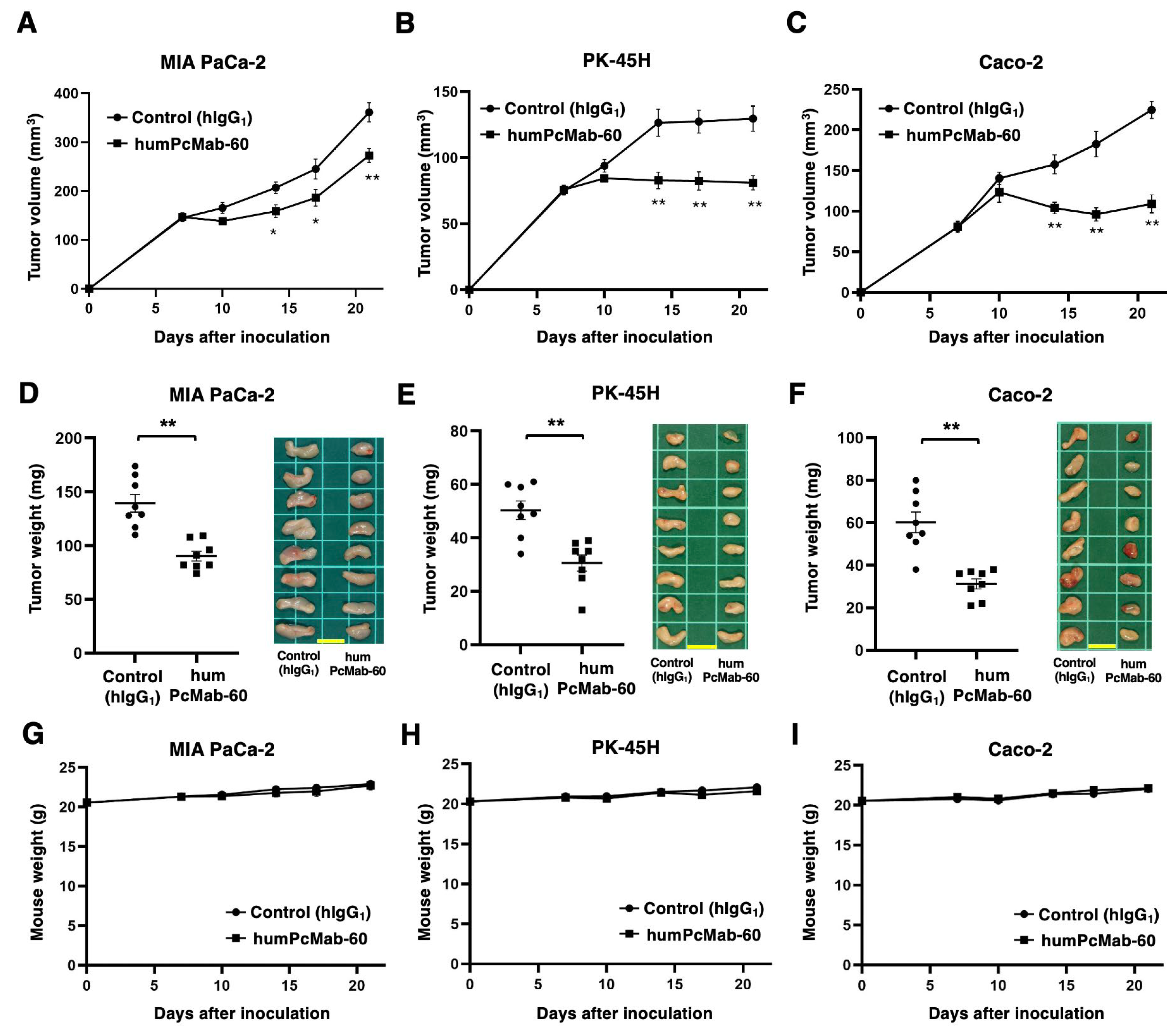

Figure 5.

Antitumor activity of humPcMab-60 against human cancer cell lines. (A–C) MIA PaCa-2 (A), PK-45H (B), and Caco-2 (C) were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice (day 0). In total, 100 μg of humPcMab-60 or control human IgG1 (hIgG1) were intraperitoneally injected into each mouse on day 7. Additional antibodies were injected on day14. The tumor volume is represented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 (ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (D–F) The mice were euthanized on day 21. The tumor weights of MIA PaCa-2 (D), PK-45H (E), and Caco-2 (F) xenografts were measured. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 (Two-tailed unpaired t test). The resected MIA PaCa-2, PK-45H, and Caco-2 xenograft tumors were shown (scale bar, 1 cm). (G–I) Body weights of MIA PaCa-2 (G), PK-45H (H), and Caco-2 (I) xenograft-bearing mice treated with humPcMab-60 or hIgG1. There is no statistical difference.

Figure 5.

Antitumor activity of humPcMab-60 against human cancer cell lines. (A–C) MIA PaCa-2 (A), PK-45H (B), and Caco-2 (C) were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice (day 0). In total, 100 μg of humPcMab-60 or control human IgG1 (hIgG1) were intraperitoneally injected into each mouse on day 7. Additional antibodies were injected on day14. The tumor volume is represented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 (ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test). (D–F) The mice were euthanized on day 21. The tumor weights of MIA PaCa-2 (D), PK-45H (E), and Caco-2 (F) xenografts were measured. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 (Two-tailed unpaired t test). The resected MIA PaCa-2, PK-45H, and Caco-2 xenograft tumors were shown (scale bar, 1 cm). (G–I) Body weights of MIA PaCa-2 (G), PK-45H (H), and Caco-2 (I) xenograft-bearing mice treated with humPcMab-60 or hIgG1. There is no statistical difference.