1. Introduction

The validation of adequate antigenic targets is essential for the development of monoclonal antibodies (mAb)-based tumor therapy[

1]. To achieve an acceptable therapeutic index with low on-target toxicity, targets highly expressed in tumors and little or no expression in normal tissues are considered ideal antigenic targets. However, the number of ideal antigenic targets is limited, which is a significant problem for developing therapeutic mAbs for tumors.

To solve the problem, we have developed cancer-specific mAbs (CasMabs) for various antigens and revealed the cancer-specific epitope and the recognition structure. In the anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) CasMab development, we established more than three hundred anti-HER2 mAb clones by immunization of mice with cancer cell-expressed HER2. These mAbs were screened by the reactivity to HER2-expressed tumor and normal cells by flow cytometry [

2]. Among them, H

2Mab-250/H

2CasMab-2 recognized HER2 in breast cancer cells but not in normal epithelial cells from the mammary gland, lung bronchus, colon, and kidney proximal tubule [

2]. Epitope analysis identified Trp614 in the extracellular domain 4 of HER2 as a critical residue for H

2Mab-250 recognition [

2].

Furthermore, mouse IgG

2a type or humanized H

2Mab-250 exhibited antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), and

in vivo antitumor efficacy against human breast cancer xenografts [

3,

4,

5]. A single chain variable fragment of H

2Mab-250 was further developed to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy and showed cancer-specific recognition and cytotoxicity [

6]. A phase I clinical trial is underway for patients with HER2-positive advanced solid tumors in the US (NCT06241456). Therefore, selecting CasMab and identifying the cancer-specific epitopes are essential strategies for developing therapeutic mAbs and modalities.

Podoplanin (PDPN) (also known as T1α, PA2.26 antigen, E11 antigen, and Aggrus) is a heavily glycosylated type I transmembrane protein, which has an N-terminal extracellular domain, a transmembrane domain, and a short intracellular domain [

7,

8]. The N-terminal extracellular domain possesses platelet aggregation-stimulating (PLAG) domains, which have a consensus repeat sequence of EDxxVTPG [

9]. The

O-glycosylation sites at Thr52 in PLAG3 or a PLAG-like domain (PLD, also named PLAG4) have been reported to be crucial for the interaction of PDPN to C-type lectin-like receptor 2 (CLEC-2), which is essential for platelet aggregation and hematogenous metastasis to lung [

10,

11].

PDPN is involved in the malignant progression of tumors by promoting invasiveness and metastasis. PDPN-expressing tumor cells show a diverse pattern of invasion [

12], including the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-like pattern in various tumors [

13,

14], collective invasion in squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) [

15], and ameboid invasion in melanoma [

16]. The intracellular domain of PDPN possesses basic residues as binding sites for ezrin, radixin, and moesin proteins [

17], which mediates Rho GTPase activity and regulate the diverse pattern of invasiveness [

18,

19]. Furthermore, PDPN binds to matrix metalloproteinases [

20] and a hyaluronan receptor CD44 [

21], which mediate the invadopodia formation and extracellular matrix degradation. In the clinic, high PDPN expression was associated with shortened overall survival in patients with gliomas, head and neck SCC, esophageal SCC, gastric adenocarcinomas, and mesotheliomas [

22,

23,

24,

25]. Therefore, PDPN has been considered a promising target of mAb-based therapy. However, PDPN also plays an essential role in normal cells, such as lung alveolar type I cells [

26] and kidney podocytes [

27,

28]. Therefore, cancer-specific reactivity is required to reduce adverse effects on normal cells.

We have developed CasMabs against PDPN by selecting the cancer-specific reactivity in flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. LpMab-2 [

29] and LpMab-23 [

30] were obtained by immunization of mice with PDPN-overexpressed glioblastoma LN229 (LN229/PDPN). LpMab-2 recognizes a glycopeptide structure (Thr55-Leu64) of PDPN [

29]. In contrast, LpMab-23 recognizes a naked peptide structure (Gly54–Leu64) of PDPN [

31]. M

ouse-human chimeric LpMab-2 and LpMab-23 (chLpMab-2 and chLpMab-23, respectively) exhibited the ADCC activity and antitumor effect in human tumor xenograft models [

31,

32]. Furthermore, we obtained another CasMab against PDPN (PMab-117) by immunization of LN229/PDPN with a rat. In flow cytometry, PMab-117 showed the reactivity to PDPN expressing tumor PC-10 and LN319. PMab-117 did not react with normal kidney podocytes and normal epithelial cells from the mammary gland, lung bronchus, and cornea. In contrast, NZ-1, one of the non-CasMabs against PDPN, exhibited high reactivity to both tumor and normal cells [

33]. PMab-117 recognizes the glycopeptide structure of PDPN (Ile78-Thr85) within PLD, including

O-glycosylated Thr85 [

7].

This study evaluates the effects of the humanized version of PMab-117 (humPMab-117) on the ADCC, CDC, and antitumor activity.

3. Discussion

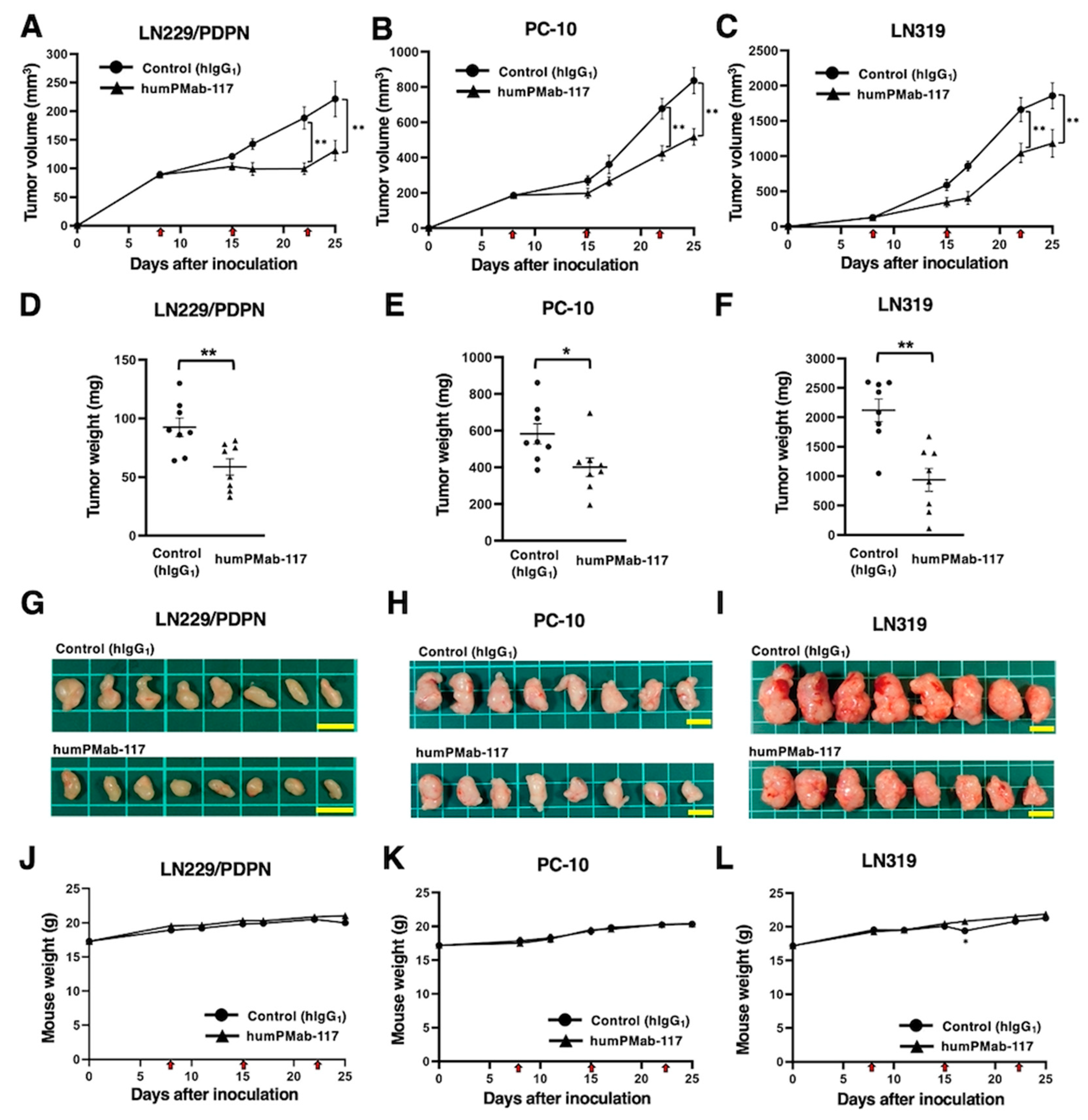

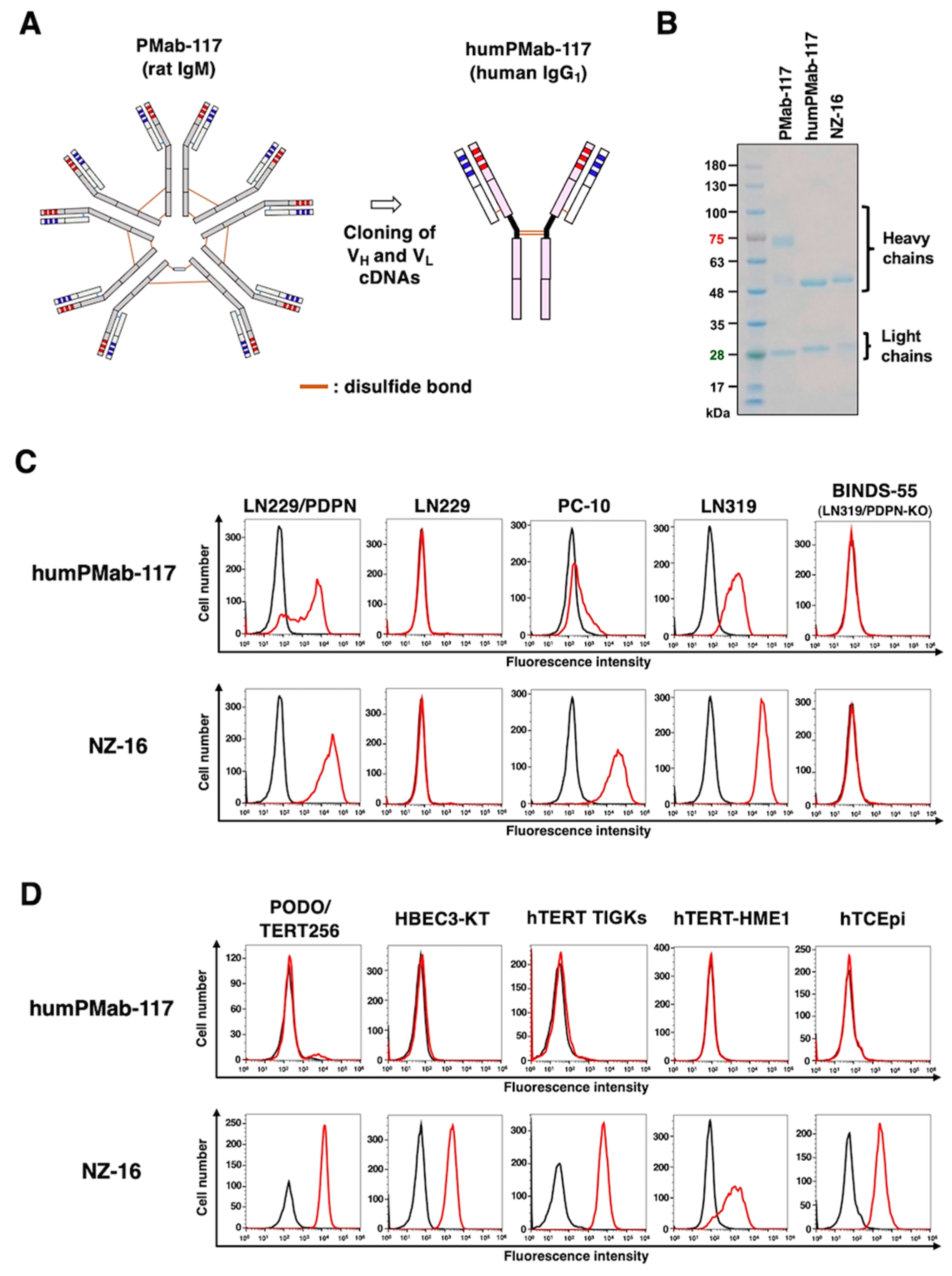

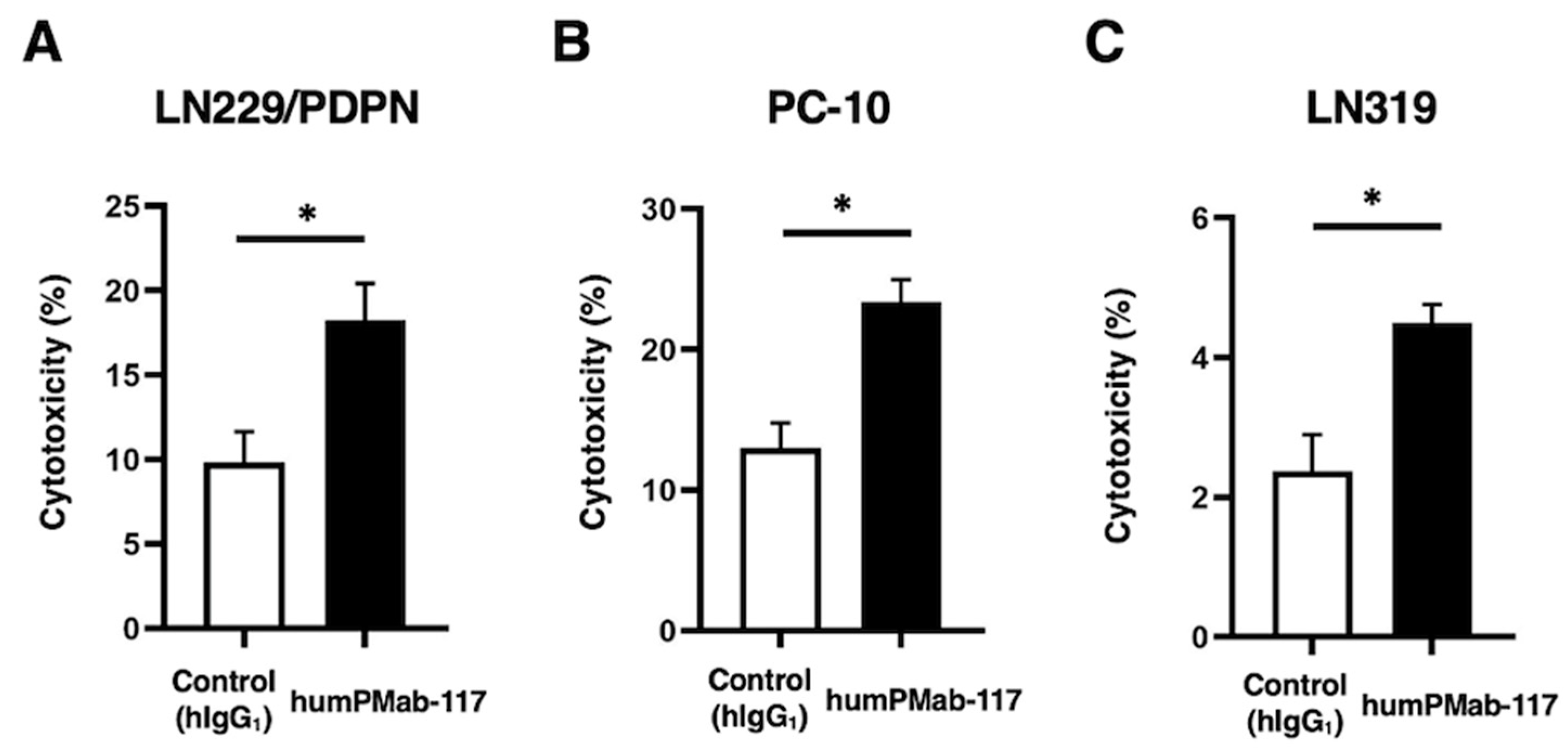

This study evaluated the

in vitro and

in vivo antitumor effects of a novel CasMab against PDPN. The human IgG

1 type PMab-117 (humPMab-117) retained the reactivity to the PDPN-expressing tumor cells but not to normal epithelial cells or kidney podocytes in flow cytometry (

Figure 1). Furthermore, humPMab-117 exerted ADCC (

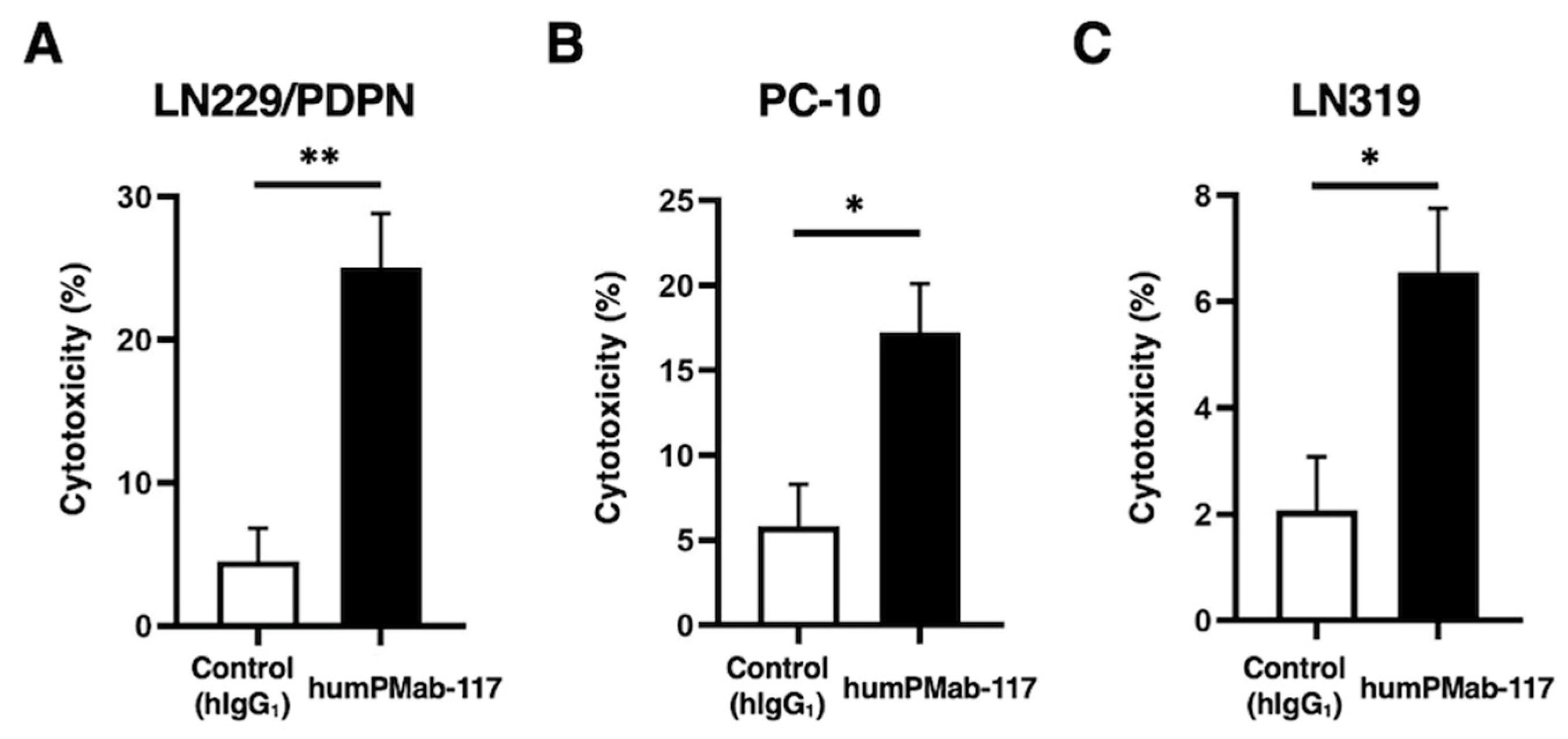

Figure 3), CDC (

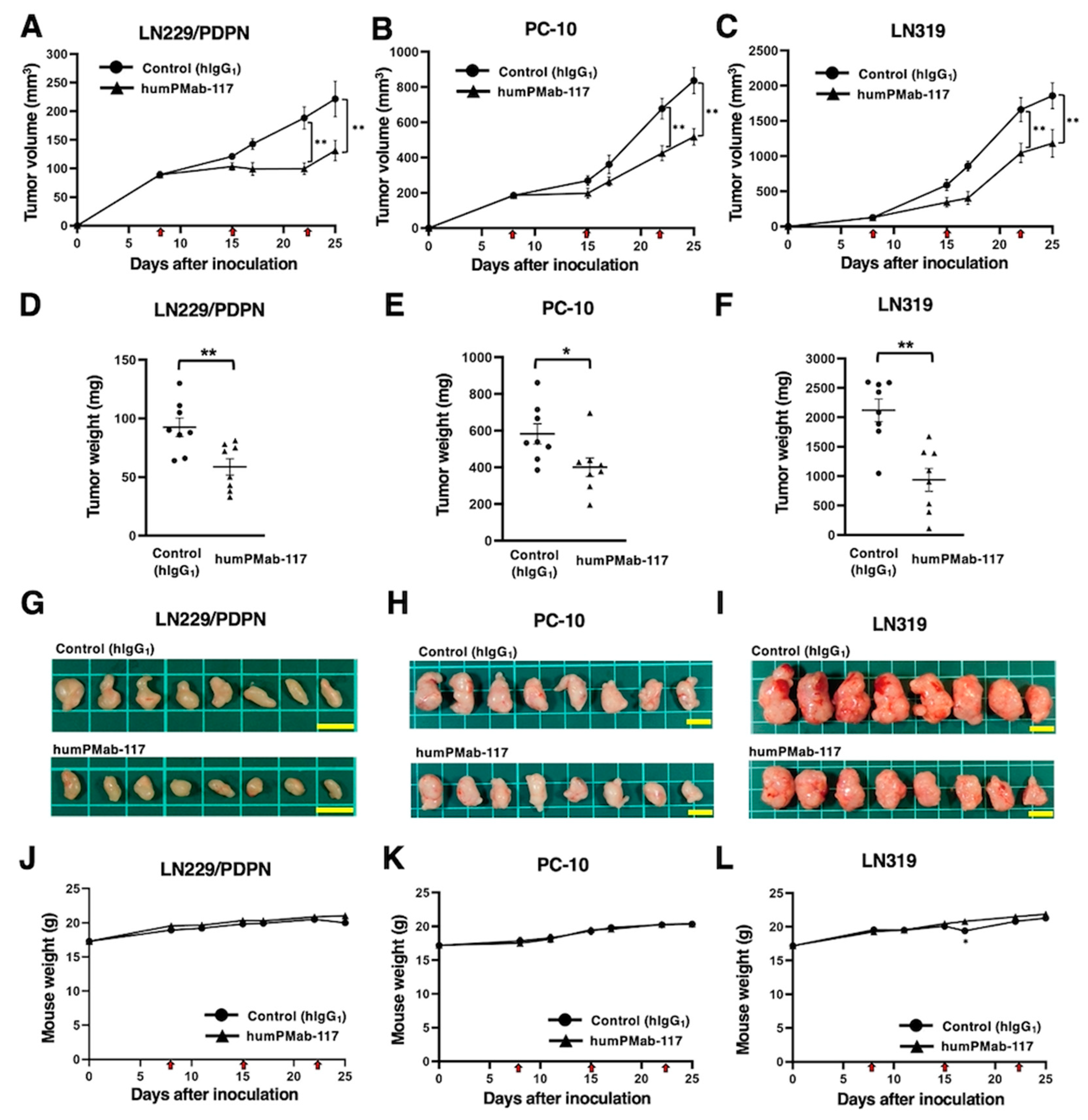

Figure 4), and antitumor effects in LN229/PDPN, PC-10, and LN319 xenografts (

Figure 5).

Several preclinical studies have evaluated the antitumor activities of humanized or chimeric anti-PDPN mAbs. The anti-PDPN mAb NZ-1 (a non-CasMab, rat IgG

2a), recognizes the PLAG2/3 domain, has a neutralizing activity to the PDPN–CLEC-2 interaction and inhibits PDPN-induced platelet aggregation and hematogenous lung metastasis [

35,

36]. NZ-16, a rat-human chimeric anti-PDPN mAb derived from NZ-1, was developed for

alpha-radioimmunotherapy. 225Ac-labeled NZ-16 showed antitumor efficacy against human malignant pleural mesothelioma

xenografts and prolonged survival without apparent adverse effect [

34]

.

Another non-CasMab, PG4D2, recognizes the PLD of PDPN and possesses neutralizing activity against the PDPN–CLEC-2 interaction and platelet aggregation [

11]. The humanized PG4D2 (AP201) is a human IgG

4 mAb, which does not have ADCC and CDC activity. Nevertheless, AP201 suppressed not only osteosarcoma hematogenous lung metastasis but also xenograft growth [

37]. The authors proposed the possibility that platelet-derived growth factors from activated platelet support the osteosarcoma proliferation, which AP201 inhibits. PMab-117 also recognizes the PLD of PDPN [

7] and humPMab-117 (human IgG

1) exerted ADCC and CDC activity against PDPN-expressing tumors (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Therefore, it is worthwhile to investigate the platelet aggregation-inhibitory effect of humPMab-117 to clarify its contribution to antitumor efficacy.

Although anti-PDPN CasMabs, LpMab-2 and LpMab-23, do not possess neutralizing activity to the PDPN–CLEC-2 interaction, human IgG

1 mAbs, including chLpMab-2, chLpMab-23, and a humanized LpMab-23 (humLpMab-23), exhibited the antitumor effect against human tumor xenograft through ADCC and CDC activity [

31,

32,

38]. These results suggest that neutralizing activity is not essential for antitumor efficacy. However, whether these mAbs affect the normal tissue

in vivo is a concern. We previously evaluated the toxicity of mouse-human chimeric LpMab-23 (20 mg/kg) against cynomolgus monkeys, and no toxicity was observed [

31]. A similar analysis is required to prove the safety of humPMab-117.

The diagnosis to determine the PDPN-positive tumor is also essential for the selection of the patients [

39]. LpMab-2, LpMab-23, and PMab-117 recognize different epitopes of PDPN [

7]. LpMab-2 and LpMab-23 retain the cancer-specific reactivity in immunohistochemistry [

29,

30]. In contrast, PMab-117 is not suitable for immunohistochemistry. Although the reactivity of humPMab-117 was much weaker than NZ-16 in flow cytometry (

Figure 1), humPMab-117 demonstrated significant antitumor activities (

Figure 5). It is possible that humPMab-117 may recognize a part of cancer-specific aberrant-structured PDPN. Further studies are required to clarify the mechanism of recognition by humPMab-117 and the distribution of PMab-117-positive tumors.

CAR-T cell therapy has achieved significant success in the treatment of hematopoietic malignancies [

40]. However, the strategy has not been fully translated to solid tumors [

41]. The most crucial problem of CAR-T cell therapy against solid tumors is a lack of tumor-specific antigens. Most therapeutic targets such as epidermal growth factor receptor [

42], HER2 [

43], and MUC1 [

44] are expressed on normal cells, which leads to on-target off-tumor toxicity due to the targeting of normal cells. Since the dosage of CAR-T cells is limited, the reactivity of CAR to normal cells should be minimized. In that sense, our CasMabs against PDPN are suitable for CAR selection. The humanized NZ-1 and LpMab-2-based CAR-T have been evaluated in preclinical models and showed the significant antitumor efficacy [

45,

46]. As shown in

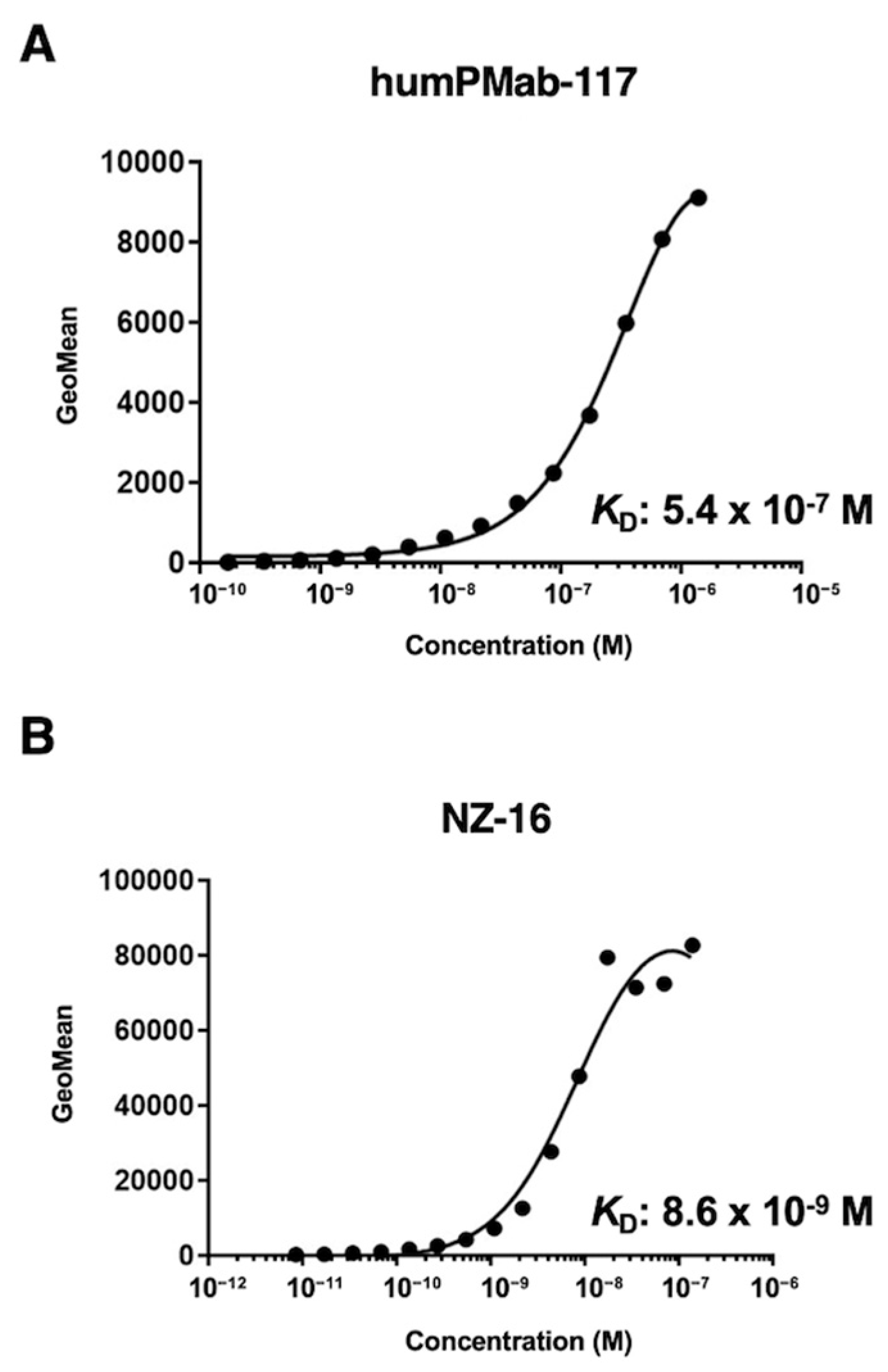

Figure 2, humPMab-117 has approximately 60-fold lower affinity (

KD: 5.4 × 10

−7 M) than NZ-16 (

KD: 8.6 × 10

−9 M). The

KD values of LpMab-2 and chLpMab-23 were previously determined as 5.7 × 10

−9 M and 1.2 × 10

−8 M, respectively [

29,

31]. These CasMabs have different binding affinities ranging from 10

−7 M to 10

−9 M. Recently, low affinity and avidity CAR-T cell therapy has exhibited enhanced cytotoxicity [

47,

48,

49], elevated expansion [

48,

50], better trafficking [

47], and increased selectivity [

49]. Furthermore, low affinity and avidity CAR-T cells have been shown to decrease exhaustion [

51] and mitigate trogocytosis [

50,

52]. It is necessary to explore the cancer-specific reactivity of PMab-117 single-chain Fv for CAR-T cell therapy. It is essential to compare the antitumor activity of three cancer-specific anti-PDPN CAR-T therapies in the future.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Lines

PODO/TERT256 and hTCEpi were purchased from EVERCYTE (Vienna, Austria). LN229, HBEC3-KT, hTERT-HME1, and hTERT TIGKs were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Human glioblastoma LN319 cells were purchased from Addexbio Technologies (San Diego, CA, USA). Human lung SCC PC-10 cells were purchased from Immuno-Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd. (Gunma, Japan).

LN229/PDPN cells were established as previously described [

29]. LN229, LN229/PDPN, and LN319 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) [Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Nacalai), Kyoto, Japan]. PC-10 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium (Nacalai). These media were supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum [FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. (Thermo), Waltham, MA, USA], 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 100 units/mL penicillin (Nacalai). ExpiCHO-S and Fut8-deficient ExpiCHO-S (BINDS-09) cells were cultured as described previously [

38].

Immortalized normal epithelial cell lines were maintained as follows: PODO/TERT256, MCDB131 (Pan Biotech, Bayern, Germany) supplemented with GlutaMAXTM-I (Thermo), Bovine Brain Extract (9.6 μg/mL, Lonza, Basel, Switzerland), EGF [8 ng/mL, Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (Sigma), St. Louis, MO, USA], Hydrocortisone (20 ng/mL, Sigma), 20% FBS (Sigma), and G418 (100 μg/mL, InvivoGen, San Diego, CA); HBEC3-KT, Airway Epithelial Cell Basal Medium and Bronchial Epithelial Cell Growth Kit (ATCC); hTERT TIGKs, Dermal Cell Basal Medium and Keratinocyte Growth Kit (ATCC); hTERT-HME1, Mammary Epithelial Cell Basal Medium BulletKitTM without GA-1000 (Lonza); hTCEpi, KGMTM-2 BulletKitTM (Lonza).

All cell lines were cultured at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and 95% air.

4.2. Animals

The Institutional Committee for Experiments of the Institute of Microbial Chemistry (Numazu, Japan) authorized animal studies for the antitumor efficacy of humPMab-117 (approval number: 2024-076). The animal studies followed the NIH (National Research Council) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Humane objectives for euthanasia were established as a loss of original body weight to a point >25% and/or a maximal tumor size >3,000 mm3.

4.3. Antibodies

To generate a humanized anti-human PDPN mAb (humPMab-117), the CDRs of PMab-117 V

H and V

L were cloned into human IgG

1 and human kappa chain expression vectors [

53], respectively. We transfected the antibody expression vectors of humPMab-117 into BINDS-09 (fucosyltransferase 8-knockout ExpiCHO-S) cells using the ExpiCHO-S Expression System (Thermo). As a control human IgG

1 mAb, humCvMab-62 was produced from CvMab-62 (an anti-SARS-CoV-2

spike protein S2 subunit mAb) using the abovementioned method. NZ-16, a rat-human chimeric anti-PDPN mAb, was previously described [

34]. humCvMab-62, humPMab-117, and NZ-16 were purified using Ab-Capcher (ProteNova Co., Ltd., Kagawa, Japan). To confirm the purity of mAbs, they were treated with sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol, separated on 5%–20% polyacrylamide gel (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan), and stained by Bio-Safe CBB G-250 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Berkeley, CA).

4.4. Flow Cytometry

Cells were harvested using 0.25% trypsin and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Nacalai). Subsequently, they were washed with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (Nacalai) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), followed by treatment with humPMab-117 or NZ-16 for 30 minutes at 4°C. Then, the cells were treated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-human IgG (1:2000; Sigma) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer (Sony Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed with FlowJo software (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

4.5. ADCC

Human NK cells were purchased from Takara Bio, Inc. (Shiga, Japan) and were used as effector cells immediately after thawing as follows. Target cells (LN229/PDPN, PC-10, and LN319) were labeled with 10 µg/mL of Calcein AM (Thermo). The target cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 10

3 cells/well and combined with effector cells (effector-to-target ratio, 50:1) and 100 μg/mL of either control human IgG

1 or humPMab-117. After incubating for 4.5 hours, the calcein released into the supernatant was measured as described previously [

4].

4.6. CDC

The target cells labeled with Calcein AM (LN229/PDPN, PC-10, and LN319) were seeded and combined with rabbit complement (final concentration 10%, Low-Tox-M Rabbit Complement; Cedarlane Laboratories, Hornby, ON, Canada) along with 100 μg/mL of either control human IgG

1 or humPMab-117. After a 4.5-hour incubation at 37°C, the amount of calcein released into the medium was measured as described previously [

4].

4.7. Antitumor Activities of humPMab-117 in Xenografts of Human Tumors

LN229/PDPN, PC-10, and LN319 were mixed with DMEM and Matrigel Matrix Growth Factor Reduced (BD Biosciences). Subcutaneous injections were then given to the left flanks of BALB/c nude mice. On the eighth post-inoculation day, 100 µg of control human IgG1 (n = 8) or humPMab-117 (n = 8) in 100 µL PBS were administered intraperitoneally. Additional antibody injections were given on days 15 and 22. The tumor diameter was assessed on days 8, 15, 17, 22, and 25 after the tumor cell implantation. Tumor volumes were calculated in the same manner as previously stated. The weight of the mice was also assessed on days 8, 11, 15, 17, 22, and 25 following breast tumor cell inoculation. When the observations were finished on day 25, the mice were sacrificed, and tumor weights were assessed following tumor excision.

4.8. Statistical Analyses

All data are represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). A two-tailed unpaired t-test was conducted to measure ADCC activity, CDC activity, and tumor weight. ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test was performed for tumor volume and mouse weight. GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used for all calculations. p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K.; methodology, T.O., M.K.; formal analysis, T.T.; investigation, H.S., T.O., and T.T.; data curation, H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.S.; writing—review and editing, Y.K.; project administration, Y.K.; funding acquisition, H.S., T.T., and Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Production of humPMab-117 and reactivity to cancer cells, normal kidney podocytes, and epithelial cells. (A) Human IgG1 mAb, humPMab-117, was generated from PMab-117 (rat IgM). (B) MAbs were treated with sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated on polyacrylamide gel. Bio-Safe CBB G-250 Stain stained the gel. (C) Flow cytometry using humPMab-117 (10 μg/mL; Red line), NZ-16 (10 μg/mL; Red line), or buffer control (Black line) against LN229, LN229/PDPN, PC-10, LN319, and PDPN-knockout LN319 (BINDS-55). (D) Flow cytometry using humPMab-117 (10 μg/mL; Red line), NZ-16 (10 μg/mL; Red line) or buffer control (Black line) against PODO/TERT256 (kidney podocyte), HBEC3-KT (lung bronchus epithelial cell), hTERT-TIGKs (gingiva), hTERT-HME1 (mammary gland epithelial cell), and hTCEpi (corneal epithelial cell). The cells were treated with FITC-conjugated anti-human IgG. Fluorescence data were analyzed using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 1.

Production of humPMab-117 and reactivity to cancer cells, normal kidney podocytes, and epithelial cells. (A) Human IgG1 mAb, humPMab-117, was generated from PMab-117 (rat IgM). (B) MAbs were treated with sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated on polyacrylamide gel. Bio-Safe CBB G-250 Stain stained the gel. (C) Flow cytometry using humPMab-117 (10 μg/mL; Red line), NZ-16 (10 μg/mL; Red line), or buffer control (Black line) against LN229, LN229/PDPN, PC-10, LN319, and PDPN-knockout LN319 (BINDS-55). (D) Flow cytometry using humPMab-117 (10 μg/mL; Red line), NZ-16 (10 μg/mL; Red line) or buffer control (Black line) against PODO/TERT256 (kidney podocyte), HBEC3-KT (lung bronchus epithelial cell), hTERT-TIGKs (gingiva), hTERT-HME1 (mammary gland epithelial cell), and hTCEpi (corneal epithelial cell). The cells were treated with FITC-conjugated anti-human IgG. Fluorescence data were analyzed using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 2.

Determination of the binding affinity of humPMab-117 and NZ-16 using flow cytometry. LN229/PDPN cells were suspended in humPMab-117 (A) or NZ-16 (B) at indicated concentrations, followed by treatment with FITC-conjugated anti-human IgG. The SA3800 Cell Analyzer was used to analyze fluorescence data. The dissociation constant (KD) values were determined using GraphPad Prism 6.

Figure 2.

Determination of the binding affinity of humPMab-117 and NZ-16 using flow cytometry. LN229/PDPN cells were suspended in humPMab-117 (A) or NZ-16 (B) at indicated concentrations, followed by treatment with FITC-conjugated anti-human IgG. The SA3800 Cell Analyzer was used to analyze fluorescence data. The dissociation constant (KD) values were determined using GraphPad Prism 6.

Figure 3.

ADCC activity by humPMab-117 against PDPN-positive cells. The target cells labeled with Calcein AM (LN229/PDPN, PC-10, and LN319) were incubated with human NK cells in the presence of humPMab-117 or control human IgG1 (hIgG1). The ADCC activities against LN229/PDPN (A), PC-10 (B), and LN319 (C) cells were determined by the calcein release. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05; two-tailed unpaired t-test).

Figure 3.

ADCC activity by humPMab-117 against PDPN-positive cells. The target cells labeled with Calcein AM (LN229/PDPN, PC-10, and LN319) were incubated with human NK cells in the presence of humPMab-117 or control human IgG1 (hIgG1). The ADCC activities against LN229/PDPN (A), PC-10 (B), and LN319 (C) cells were determined by the calcein release. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (* p < 0.05; two-tailed unpaired t-test).

Figure 4.

CDC activity by humPMab-117 against PDPN-positive cells. The target cells labeled with Calcein AM (LN229/PDPN, PC-10, and LN319) were incubated with rabbit complement in the presence of humPMab-117 or control human IgG1 (hIgG1). The CDC activities against LN229/PDPN (A), PC-10 (B), and LN319 (C) cells were determined by the calcein release. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (** p < 0.01 and * p < 0.05; two-tailed unpaired t-test).

Figure 4.

CDC activity by humPMab-117 against PDPN-positive cells. The target cells labeled with Calcein AM (LN229/PDPN, PC-10, and LN319) were incubated with rabbit complement in the presence of humPMab-117 or control human IgG1 (hIgG1). The CDC activities against LN229/PDPN (A), PC-10 (B), and LN319 (C) cells were determined by the calcein release. Values are shown as the mean ± SEM. Asterisks indicate statistical significance (** p < 0.01 and * p < 0.05; two-tailed unpaired t-test).

Figure 5.

Antitumor activity of humPMab-117 against human tumor xenografts. (A–C) LN229/PDPN (A), PC-10 (B), and LN319 (C) cells were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice (day 0). humPMab-117 (100 μg) or control human IgG1 (hIgG1, 100 μg) were intraperitoneally injected into each mouse on days 8, 15, and 22 (arrows). The tumor volume is represented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test). (D–F) After cell inoculation, the mice were euthanized on day 25. The tumor weights of LN229/PDPN (D), PC-10 (E), and LN319 (F) xenografts were measured. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 and * p < 0.05 (two-tailed unpaired t-test). (G–I) LN229/PDPN (G), PC-10 (H), and LN319 (I) xenograft tumors on day 25 (scale bar, 1 cm). (J–L) Body weights of LN229/PDPN (J), PC-10 (K), and LN319 (L) xenograft-bearing mice treated with control hIgG1 or humPMab-117. The body weight is represented as the mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test).

Figure 5.

Antitumor activity of humPMab-117 against human tumor xenografts. (A–C) LN229/PDPN (A), PC-10 (B), and LN319 (C) cells were subcutaneously injected into BALB/c nude mice (day 0). humPMab-117 (100 μg) or control human IgG1 (hIgG1, 100 μg) were intraperitoneally injected into each mouse on days 8, 15, and 22 (arrows). The tumor volume is represented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test). (D–F) After cell inoculation, the mice were euthanized on day 25. The tumor weights of LN229/PDPN (D), PC-10 (E), and LN319 (F) xenografts were measured. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01 and * p < 0.05 (two-tailed unpaired t-test). (G–I) LN229/PDPN (G), PC-10 (H), and LN319 (I) xenograft tumors on day 25 (scale bar, 1 cm). (J–L) Body weights of LN229/PDPN (J), PC-10 (K), and LN319 (L) xenograft-bearing mice treated with control hIgG1 or humPMab-117. The body weight is represented as the mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05 (two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s post hoc test).