1. Introduction

The Mississippi River system drains approximately 3,224,600 km

2, making it the largest drainage basin in the United States. One of its major distributaries, the Atchafalaya River, forms an extensive network of anastomosing channels, backwater swamps, freshwater marshes, and wetland forests. In Louisiana, the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River system is the major supplier for suspended and dissolved continental materials to the coastal ocean, approximately 66% ([

1]). The sedimentation rate is around 7-8 cm year

-1 in the Mississippi River mouth and is 2.2-5.6 cm year

-1 in the Atchafalaya River mouth ([

2]). On the Mississippi River’s path to coastal ocean, the river changed courses and formed abandoned delta lobes composed of sand and mud over thousands of years. Six larger deltaic lobes were formed by the Mississippi-Atchafalaya River system over the past 4600 years, including Salé-Cypremort, Cocodrie, Teche, St. Bernard, Lafourche, Plaquemine, and Balize.

Sands in the submarine shoals and paleo river channels of Mississippi-Atchafalaya River system have been widely used for beach and barrier island restoration projects in coastal Louisiana, but there is still limited knowledge on how dredged pits evolve and when they reach an equilibrium with ambient environment which is significant to ensuring long-term coastal restoration success, minimizing environmental impacts, and supporting sustainable sediment resource management. Past studies were mainly focused on sandy dredge pits ([

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]) or on the muddy dredge pits what are partially infilled by sediments ([

11,

12,

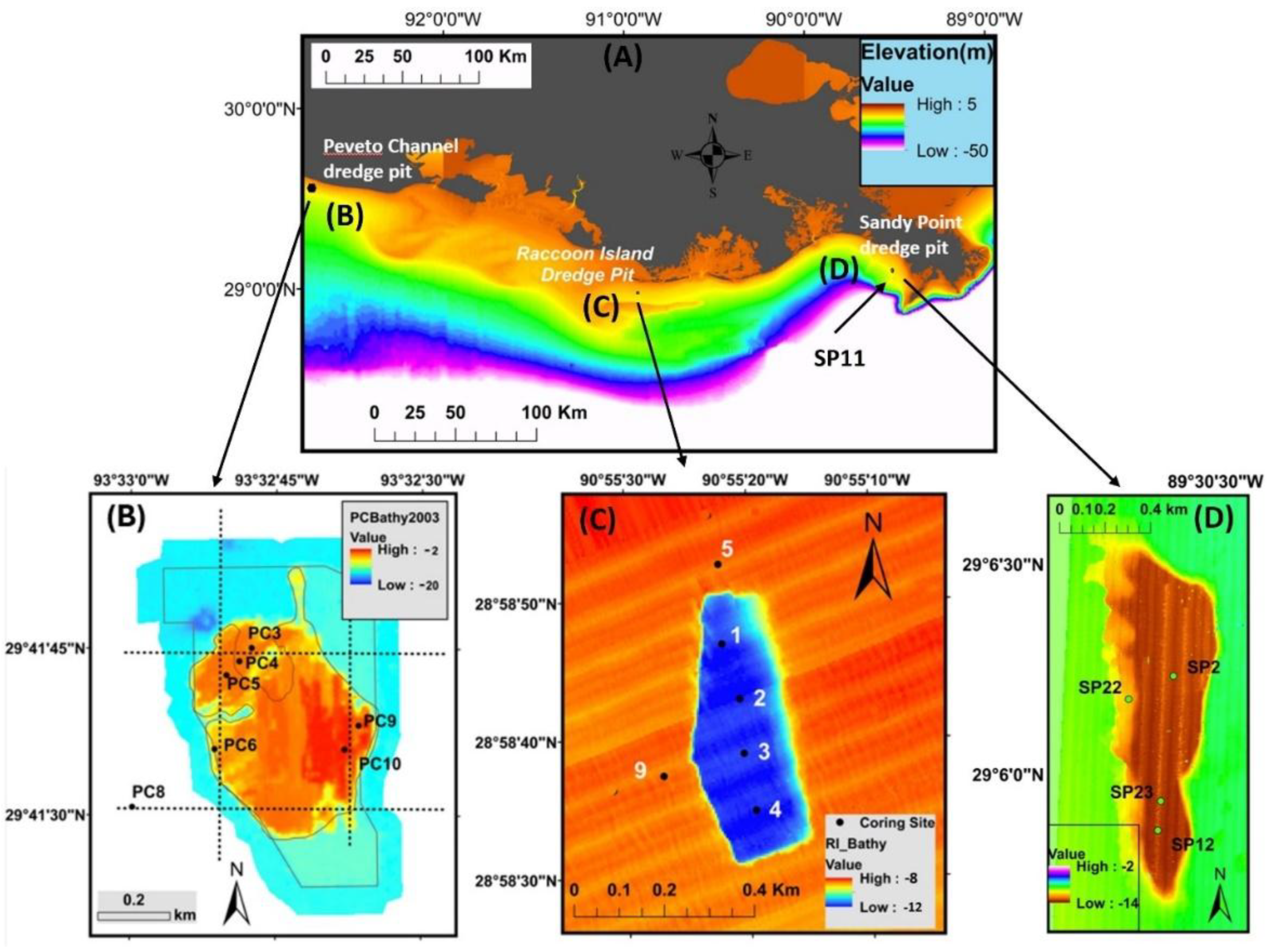

13]). Three large mud-capped dredge pits (MCDPs) in coastal Louisiana are Peveto Channel, Raccoon Island and Sandy Point (from west to east;

Figure 1). Peveto Channel dredge pit, which is offshore Holly Beach of Louisiana, was excavated in the year 2003. This pit has a dimension of 400 m (shore-parallel) by 600 m (shore-normal) and was about 8 m deep after dredging ([

14,

15]). Robichaux et al. [

16] conducted a geophysical study on this pit in 2016 and found that the pit was 100% filled up. They concluded the continuing dewatering and long consolidation processes at the pit site after a complete infilling. However, they didn’t collect sediment data to study the consolidation processes. Raccoon Island is the westernmost barrier island in the Isles Dernieres chain in central coastal Louisiana ([

17]). The dredge pit was excavated in 2013 offshore Raccoon Island (

Figure 1). The Raccoon Island pit experienced a fast-infilling rate of 50-100 cm/year in a few years after the dredging in 2013 and was 100% filled up in 2018. Three years later, however, this pit experienced a “new subsidence” of 0.5 m below ambient sea floor, possible due to additional fast degassing and consolidation in response to energetic events ([

18]). This is the first time that a filled-up dredge pit in Louisiana experiences a new subsidence/collapse, indicating that long-term degassing and continuing consolation should be considered in long term prediction. Sandy Point dredge pit was excavated in 2012 to provide sand sources for restoration of the Barataria Bay coastline ([

18]). This pit is located 20 km west of the Mississippi Delta in a water depth of 11 m and experienced a sediment infilling of about 54 cm/year [

19] (

Figure 1).

Compared with natural deposition rates of 1-8 cm year-1 at river mouths, the high sediment deposition rates of 54-100 cm year-1 in three pits provide a unique opportunity to study high temporal variations of materials deposited in three pits. Three mud-capped dredge pits on Louisiana shelf serve as ideal natural “laboratories” to study the transport and deposition of muds, sands, organic matter and carbonate on the Louisiana continental shelf. Our study aims to address the following three scientific questions that will improve our understanding of MCDPs evolution after dredging, especially after the filling-up: 1) to compare sediment grain size, organic matter and carbonate content of infilling sediments in three pits and investigate their correlations, 2) to infer their sources to better understand what physical processes control the infilling and resuspension, 3) to discuss the long-term evolution of pits after filling-up and when the infilled sediments will reach an equilibrium with ambient sea floor. Our results will help scientific community, sand resource managers and policy makers get a better understanding of the “complete” life cycle of a dredge pit and minimize the influences of the dredging activities on the ambient geological and biological environments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Data Acquisition

All the cores used in this study were collected using a 5-m-long aluminum core barrel on LSU Coastal Studies Institute’s

R/V Coastal Profiler. In Peveto Channel (here defined as PC) dredge pit (west), 7 vibracores were collected on July 28, 2021 (

Figure 1;

Table 1). In Raccoon Island (RI) dredge pit (middle), 6 vibracores were collected on August 19, 2020, with 4 and 2 vibracores inside and outside the pit, respectively (

Figure 1). In Sandy Point (SP) dredge pit (east), 5 vibracores were collected on September 12, 2022, with 4 and 1 vibracores inside and outside the pit, respectively. Vibracore methods have been successfully used in mud-capped dredge pits in the Louisiana shelf in the past ([

10,

11,

12,

21]). All the vibracores were capped and sealed with electrical tape in the field and shipped to a lab at LSU and stored in cold rooms. The cores were then extruded and split lengthwise every 20 cm. Top 1 cm of every 20 cm of sediment segment was then subsampled for grain size, loss-on-ignition (LOI) and carbonate analyses, as described below. All sediment samples were sealed in Whirl-Pak sampling bags for further analysis.

2.2. Grain Size, Organic Matter, and Carbonate

A Beckman-Coulter laser diffraction particle size analyzer with an Aqueous Liquid Module, having measurement values range from 0.02 to 2000 µm, was used to analyze multicore and vibracore samples. Sediment samples are prepared by mixing ~2 g of wet sample with 5~7 drops of 30% hydrogen peroxide in the test tubes. These tubes containing samples were put in water bath beakers at a temperature of 70 °C for 3-5 days. After organic matter was digested completely, testing tubes were placed in a centrifuge for 4 minutes at a speed of 4000 RPM. Each sample was then mixed and sonicated prior to measurement. Grain size distribution plots were then generated using MATLAB software. Then the fractions of sand (>63 µm; phi < 4), silt (4~63 µm; phi is 4~8) and clay (<4 µm; phi > 8) were determined. More details of the grain size method are in [

22].

Loss-on-ignition (LOI) analysis was performed on sediment samples to estimate both organic matter and carbonate contents ([

23]). Sediment samples of ~ 1.5 g were dried at 100 °C for 24 hours, ground to powder and weighed, then heated in a ceramic crucible using a muffle furnace for 3 h at 550 °C. Remaining samples were weighed, and organic matter (LOI

550°) was calculated using Equation (1) ([

22]).

where DW

100° and DW

550° are the samples’ dry weight at 100 °C and 550 °C, respectively (both in g).

The remaining sediment samples were combusted again in a ceramic crucible using a muffle furnace for 2 h at 950 °C. Remaining sediments were then weighed, and carbonate content (LOI

950°) was determined using Equation (2) below ([

23]).

where DW550° and DW950° indicate the samples’ dry weight at 550 °C and 950 °C, respectively (both in g). All LOI samples were tested twice and the LOI of each sediment sample was an average of two duplicates.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The lengths of vibracores collected in the field varied from site to site. The shortest core used in this study is 180 cm long. For easier comparison among all the cores in three pits (PC, RI and SP), only the top 180 cm of each vibracore was used to perform the following statistical analyses. A multiple linear regression model was implemented to predict grain size from depth, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, organic matter, carbonate and density for each pit. Moreover, standardized coefficients are computed and rounded with two decimals to achieve more accessible comparison among explanatory variables for each model. PROC REG procedure in SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 with Stepwise Selection option was utilized to generate the multiple linear regression model results.

Furthermore, the generalized linear model was implemented to compare the grain size difference between paired positions. The significant level has been chosen as 0.05. If the p value is less than 0.05, there will be sufficient evidence to conclude that the grain size difference between the paired positions is statistically significant. PROC REG procedure with CLASS and LSMEANS statements in SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 was utilized to generate the generalized linear model results.

Paired T-test on grain size data was performed to compare differences among Raccoon Island Inside and outside of pits, Peveto Channel Inside and outside of pits, and Sandy Point Inside and outside of pits vibracores. Correlation coefficients of the relationship between grain size carbonate content, and organic matter.

Centered log-ratio (clr) transformations were performed on the closed grain size distribution (GSD) prior to multivariate statistical analysis. The centered log-ratio transformation (clr) divides each compositional part by geometrically the mean of all parts. It is written as

clr(x)=(logxig(x)) i=1,...,Dwithg(x)=(∏i=1Dxi)1/D=exp(1D∑i=1Dlogxi),

More details about Centered log-ratio (clr) transformations are discussed in [

24].

PCA was conducted in 12 grain size classes that were present in the sediment samples. They are 12.02 φ~10.99 φ (A), 10.99 φ~9.99 φ(B), 9.99 φ~8.97 φ(C), 8.97 φ~8.00 φ(D), 8.00 φ~7.00 φ(E), 7.00 φ~6.00 φ(F), 6.00 φ~5.00 φ(G), 5.00 φ~4.76 φ(H), 4.76 φ~4.61φ(I), 4.61 φ~4.24 φ(J), 4.24 φ~4.00 φ(K), and 4.00 φ~ -1.00 φ(L), respectively. This data grouping method is referenced from [

25] and [

26].

All the figures generating, and statistical analysis were conducted on Python 3.11.

3. Results

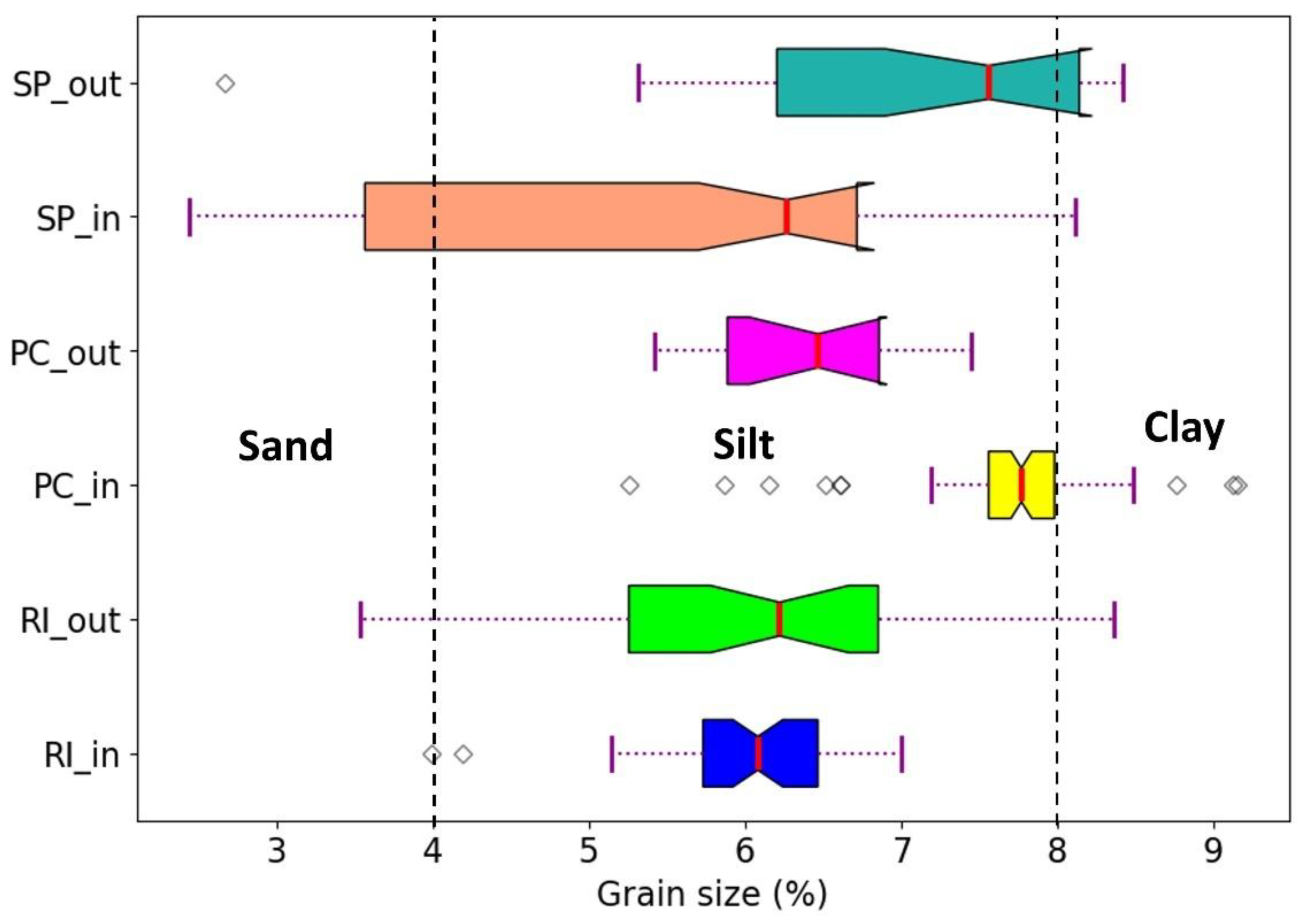

The interquartile range (IQR) for grain size at the Sandy Point dredge pit is 3.1 phi inside the pit and 1.9 phi outside, indicating a broader spread and greater variability within the pit. Both inside and outside the pit, the grain size data exhibit positive skewness. In contrast, the Peveto Channel dredge pit shows IQRs of 0.4 phi inside and 0.9 phi outside, while the Raccoon Island dredge pit has IQRs of 0.8 phi inside and 1.5 phi outside. Notably, the grain size data outside both the Raccoon Island and Peveto Channel pits are positively skewed, whereas inside these pits, the data are negatively skewed. Overall, the Sandy Point dredge pit displays the largest IQR, suggesting that its grain size distribution is more poorly sorted and highly variable. On

Figure 2, only the grain size data from Sandy Point dredge pit include sand and clay portion within IQR. Besides, Peveto Channel dredge pit grain size data have the smallest IOR spreading that shows the grain size data is the least dispersed. The median grain size values of these six data groups are inside the range of 6 phi to 8 phi, the category of fine silt. Specifically, the grain size inside the Raccoon Island dredge pit has the smallest median value while the grain size inside the Peveto Channel dredge pit has the biggest median value (

Figure 2). Grain size data inside the Peveto Channel dredge pit has the most potential outliers.

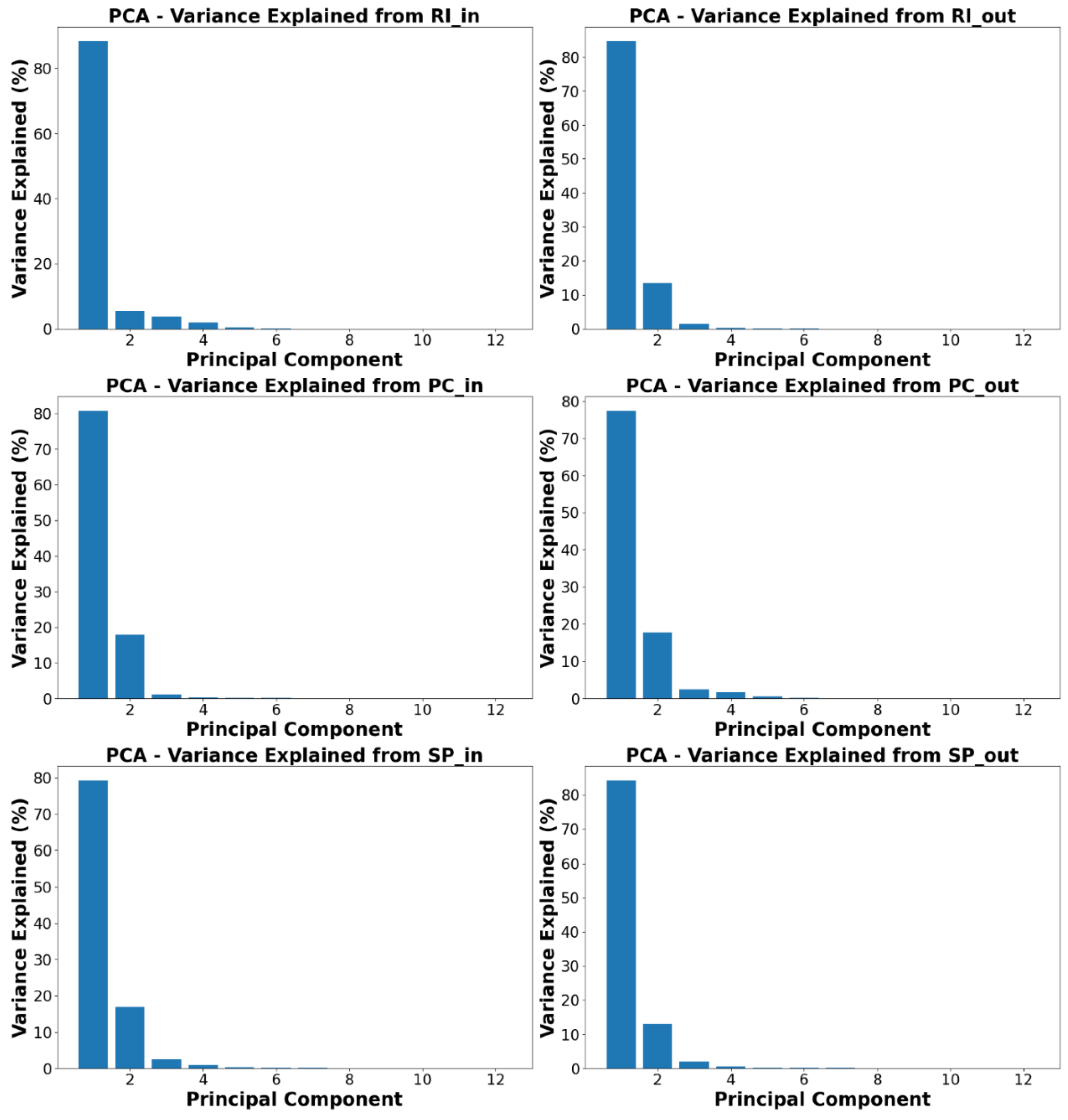

PCA was conducted in 12 grain size classes that were present in the sediment samples from six data sets, inside and RI_out, RI_in and PC_out, and PC_in and SP_in and SP_out. Across the six data groups, the first and second principal components (PCs) capture varying proportions of the total variance. For the Raccoon Island inside group (RI_in), they account for 89.04% and 6.11%, respectively. In the Raccoon Island outside group (RI_out), these components explain 83.76% and 14.55% of the variance. The Peveto Channel inside group (PC_in) shows 76.44% and 21.81%, while the outside group (PC_out) has 76.21% and 20.01%. For the Sandy Point inside group (SP_in), the PCs cover 78.24% and 18.44%, and for the outside group (SP_out), they account for 84.33% and 12.42% of the variance. (

Figure 3).

Three multiple linear regression models with standardized coefficients have been generated for three pits (PC, RI and SP). The formula for the multiple linear regression model is:

y = β0 + β1x1 + β2x2 + β3x3 + β4x4 + β5x5 + β6x6 + β7x7 + ε

In the established models, Y, X1, X2, X3, X4, X5, X6 and X7 stands for grain size, depth, sd, skew, kurt, organic matter, carbonate and density respectively. Moreover, since the coefficients have been standardized, the estimated intercepts are all zeros. The models are presented as below for each position:

PC: Y = 0X1 - 0.81X2 - 0.63X3 - 0.15X4 + 0X5 + 0X6 - 0.10X7 R2 = 0.9861

RI: Y = 0X1 - 0.33X2 - 0.60X3 - 0.53X4 + 0.18X5 + 0.10X6 + 0X7 R2 = 0.8706

SP: Y = 0X1 + 0.26X2 - 0.76X3 + 0X4 + 0X5 + 0X6 + 0X7 R2 = 0.7798

Table 2.

Standardized Coefficients for each multiple linear regression model.

Table 2.

Standardized Coefficients for each multiple linear regression model.

| Pit |

Grain Size |

Depth |

SD |

Skew |

Kurt |

Organic Matter |

Carbonate |

Density |

Intercept |

RMSE |

R-Square |

| PC |

|

|

-0.81 |

-0.63 |

-0.15 |

|

|

-0.10 |

|

0.0822 |

0.9861 |

| RI |

|

|

-0.33 |

-0.60 |

-0.53 |

0.18 |

0.10 |

|

|

0.3678 |

0.8706 |

| SP |

|

|

0.26 |

-0.76 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.9242 |

0.7798 |

From the results of multiple linear regression models, the grain size can be predicted from depth, SD, skewness, kurtosis, organic matter, carbonate and density for each pit. In the PC pit, SD, skewness, kurtosis, and density are negatively correlated to grain size. Meanwhile, the SD is the most influential explanatory variable based on the absolute value of the standardized coefficients. In the RI pit, SD, skewness and kurtosis are negatively correlated to grain size, while organic matter and carbonate are positively correlated to grain size. Meanwhile, skewness is the most influential explanatory variable based on the absolute value of the standardized coefficients. In the SP pit, Skew is negatively correlated to grain size, while SD is positively correlated to Grain Size. Meanwhile, the skewness is the most influential explanatory variable based on the absolute value of the standardized coefficients. From the results of generalized linear model, the grain size difference between paired positions can be qualitatively determined. PC_in position has significantly higher grain size than PC_out, RI_in, RI_out, SP_in and SP_out positions. PC_out position has significantly higher grain size than RI_out and SP_in positions. SP_in position has significantly lower grain size than SP_out position.

4. Discussion

4.1. Sediment Grain Size on Louisiana Continental Shelf

Peveto Channel, Raccoon Island, and Sandy Point dredge pits span the inner Louisiana continental shelf, from Holly Beach in the west to the Mississippi bird-foot delta in the east (

Figure 1). In addition to sediment transport on the Louisiana continental shelf serving as a primary control on regional sediment dynamics, factors such as surficial sand and mud distribution, proximity to river mouths, paleo-river channel presence, seafloor topography, and extreme weather events may also influence sedimentation patterns within the three dredged pits.

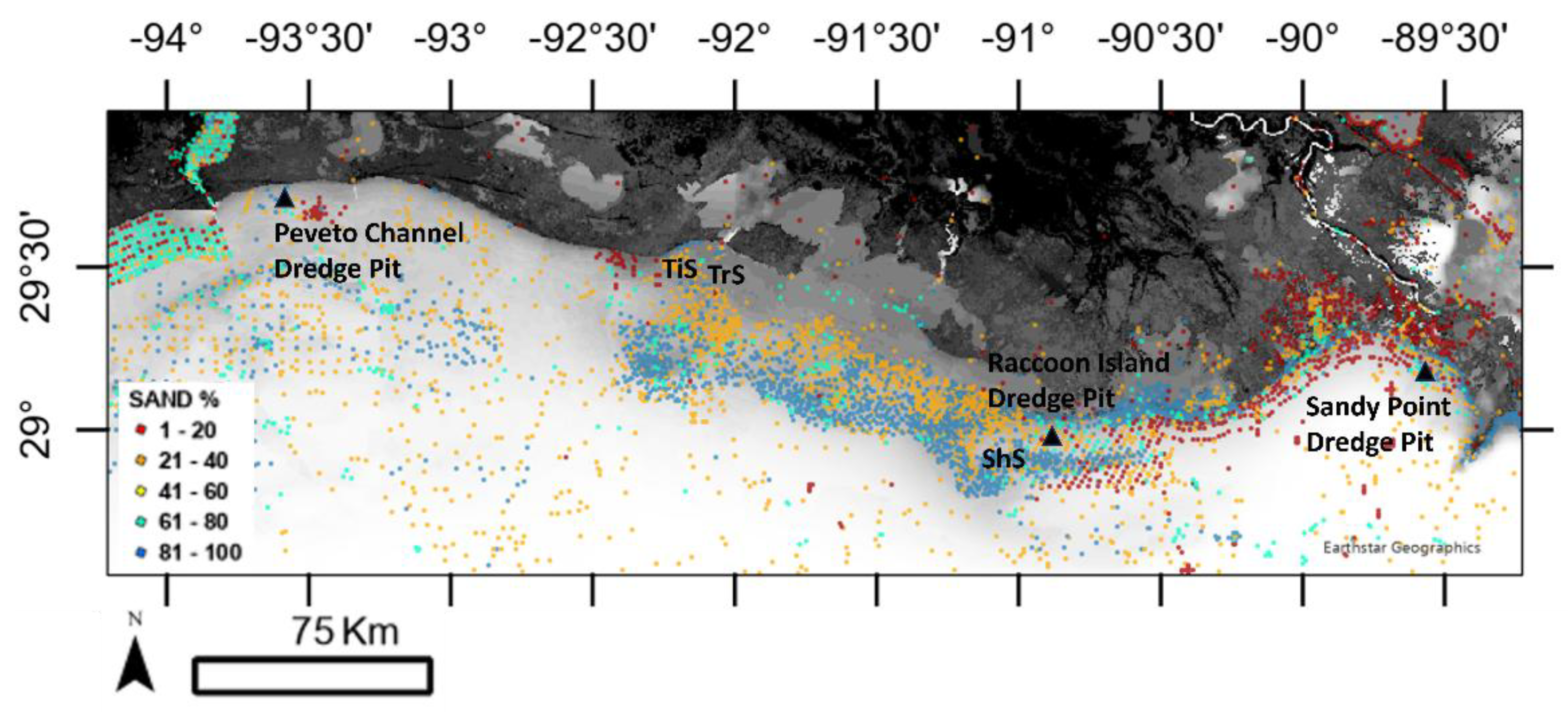

It is well known that there are both sand and muds on Louisiana continental shelf (

Figure 4). Muds are generally widely distributed in marshes, delta fronts and on the inner-middle shelf. Sands are mainly found near barrier islands, such as Isle Dernieres. Submarine shoals like Ship Shoal, Tiger Shoal and Trinity Shoal contain high quality sand which can be used for borrowing areas for coastal restoration projects. Both modeling and observational studies show that the overall sediment transport directions along inner to middle Louisianan shelf are westward ([

27] and [

28]).The area east (and thus upstream) of Peveto Channel pit is mainly the muddy inner shelf, without many nearby sandy sources. The area east of Raccoon Island pit is right in a muddy “trough” between Ship Shoal and Isle Dernieres, both of which are sandy (

Figure 4). The area east of Sandy Point pit is the Mississippi bird-foot delta which contains muddy marshes, river sand bars, sandy barrier islands and muddy delta front.

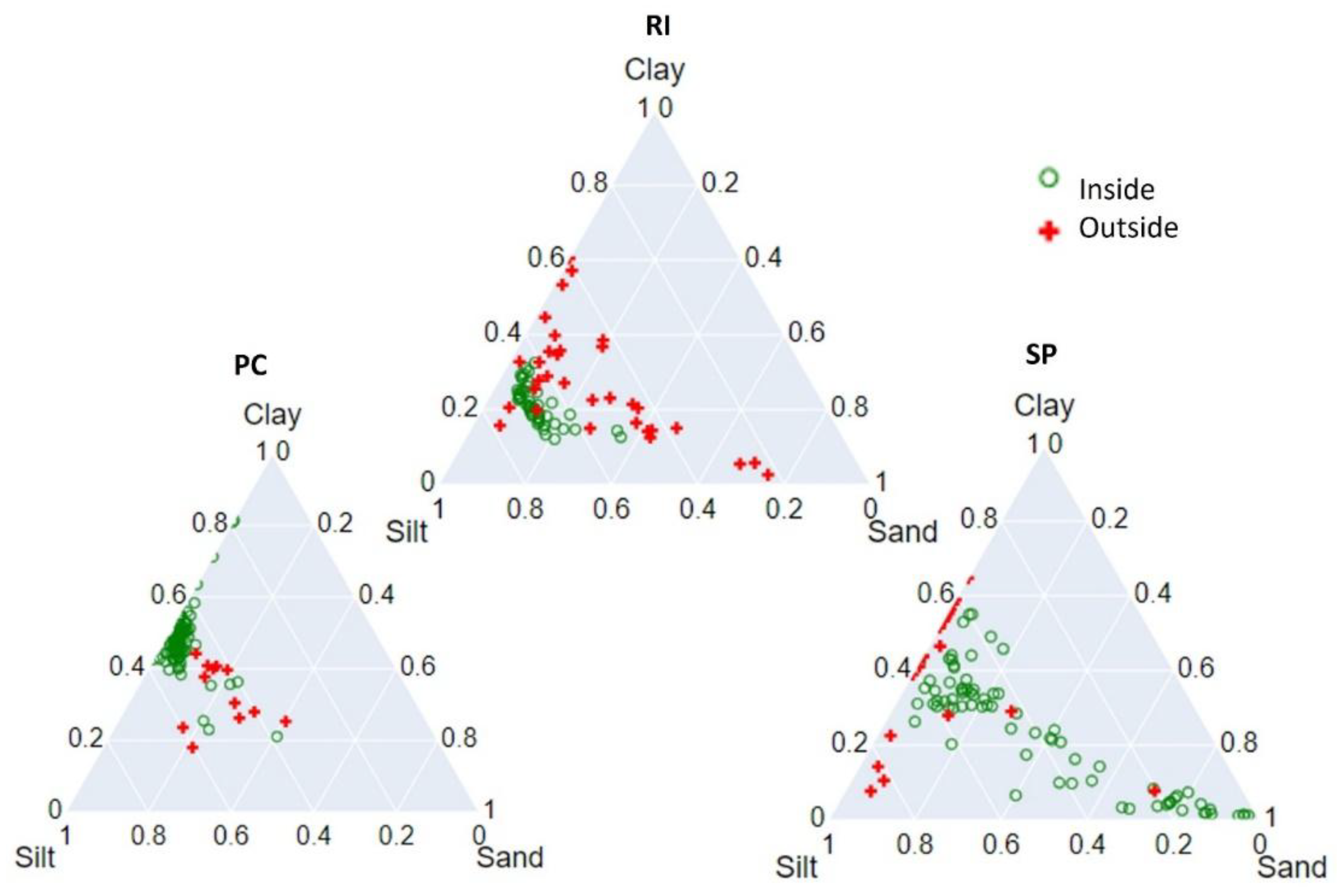

According to our grain size data (

Figure 4), the inner Louisiana continental shelf is generally silt-dominated, and its sand composition is mainly controlled by distance to sandy shoal and paleo river channels ([

23];

Figure 5), two known sand sources on the inner shelf. Thus, this reflects the spatial distribution surficial sands and muds on seafloor. In Peveto Channel dredge pit, the composition of sand, silt, and clay has the least variation than Sandy Point and Raccoon Island dredge pits (

Figure 5). Besides, its IQR in grain size is the smallest (

Figure 2). This demonstrates that the infilling sediment at Peveto Channel dredge pit is from a stable and well-sorted source, i.e., the westward mud stream downdrift of the Atchafalaya Bay, controlled by current-wave-enhanced sediment gravity flows [

29].

Peveto Channel dredge pit sediment vibracores were collected in July 2021 (

Table 1) and two major hurricanes, Delta (October 2020) and Laura (August 2020) passed through this area before the sediment sampling. However, we didn’t find much sandy portion variation. Therefore, it is likely that the extreme weather conditions, like hurricanes and cold fronts, didn’t play the major role in changing the grain size composition. However, the sand portion outside the Raccoon Island dredge pit ranges from 0% to 79% and the sand portion inside the Sandy Point dredge pit ranges from 5% to 97% (

Figure 5). In Raccoon Island pit, the high sandy portion was found from the sediment cores outside the dredge pit. One possible reason is that the sandy portion comes from the nearby sandy shoal. Another possible explanation is that the sandy portion comes from the submarine Ship Shoal. [

21] reported that multicores close to Ship Shoal have a higher sandy portion and vibracores have sandy layers which is possibly a result of hurricane induced sediment transport. Different from the Raccoon Island pit, the high sandy portion was found inside the Sandy Point pit. This is interesting because scientists used to believe finer sediment accumulated inside the pit since topographic low from dredging is an effective sediment trap [

30]. In Sandy Point pit, the sandy portion was found in SP22 and SP23 which are two vibracores collected from the collapsed pit wall (

Figure 1). These sand portions possibly come from the ambient paleo river channel collapse and the rest of the fine-grained sediment should come from the hydrodynamic activities.

In summary, the sandy portion variation from the Raccoon Island dredge pit is a combination of adjacent to the sandy shoal and hurricane induced transportation. However, the sandy portion variation from the Sandy Point dredge pit is a combination of dredging activities and hurricane induced transport. For the sediment around the Peveto Channel dredge pit, its sandy portion is relatively stable since it has no sandy shoal around and no collapsed sandy sediment from the paleo river channel (

Figure 5).

The mutually P-values are bigger than 0.05 for the grain size data from outside the Peveto Channel, Raccoon Island, and Sandy Point dredge pits (

Table 3). It indicates that the seafloor grain size from Holly Beach to the Mississippi River Delta are not statistically different. This result supports the conclusion that the inner Louisiana continental shelf is mainly silt dominated sediment. The P-values between grain size data inside the Raccoon Island dredge pit and Peveto Channel dredge pit are smaller than 0.05 which means the newly infilling sediments to these two dredge pits are statistically different (

Table 3). However, the P-values between grain size data inside Raccoon Island and Sandy Point dredge pits are bigger than 0.05 which means their difference is not statistically significant. The P-values between grain size data inside the Peveto Channel and Sandy Point dredge pits are greater than 0.05 too.

4.2. Variation of Organic Matter and Carbonate Content

Organic matter (OM) in coastal sediments varies significantly depending on proximity to terrestrial sources, hydrodynamic energy, and depositional environment. Terrestrial OM tends to dominate nearshore and marsh environments due to riverine input and wetland plant decay, often exceeding 50% in marsh sediments ([

31,

32,

33]). In contrast, sediments on the Louisiana continental shelf typically contain 1–5% OM due to offshore dilution, mineral input, and reduced OM preservation ([

21,

34,

35,

36]) The data from this study fall within or slightly above this shelf range but show significant spatial variability among dredge pits and between inside vs. outside pit locations (

Figure S1). For instance, median OM concentrations are highest in the Sandy Point and Peveto Channel dredge pits (~8%) and lower in Raccoon Island (~3–5%). Interestingly, the inside of the Raccoon Island pit shows slightly higher OM than the outside, possibly due to OM accumulation in a more quiescent setting. Conversely, Sandy Point shows higher OM outside the pit, which may result from sediment mixing and redistribution following dredging or storm events. Peveto Channel shows relatively uniform OM between inside and outside, consistent with its proximity to the mainland (~7 km from Holly Beach) and possible steady input of terrestrial OM. Besides, Sandy Point dredge pit is about 9.6 km away from the coastal land, and Raccoon Island dredge pit is about 10 km to the Isles Dernieres and about 18 km to the nearest coastal line (

Figure 1). Therefore, the proximity to the nearby land could be the reason for high organic matter content from Peveto Channel dredge pit. Although Sandy Point dredge pit has a similar relative distance to the coastal land nearby, it is the nearest distance to the Mississippi River Delta, about 30 km (

Figure 1). The river flow with high dissolved organic matter (DOM) and particulate organic matter (POM) from various sources such as decaying plant material, animal waste, and other organic debris, could be the reason for the high organic matter around the Sandy Point dredge pit.

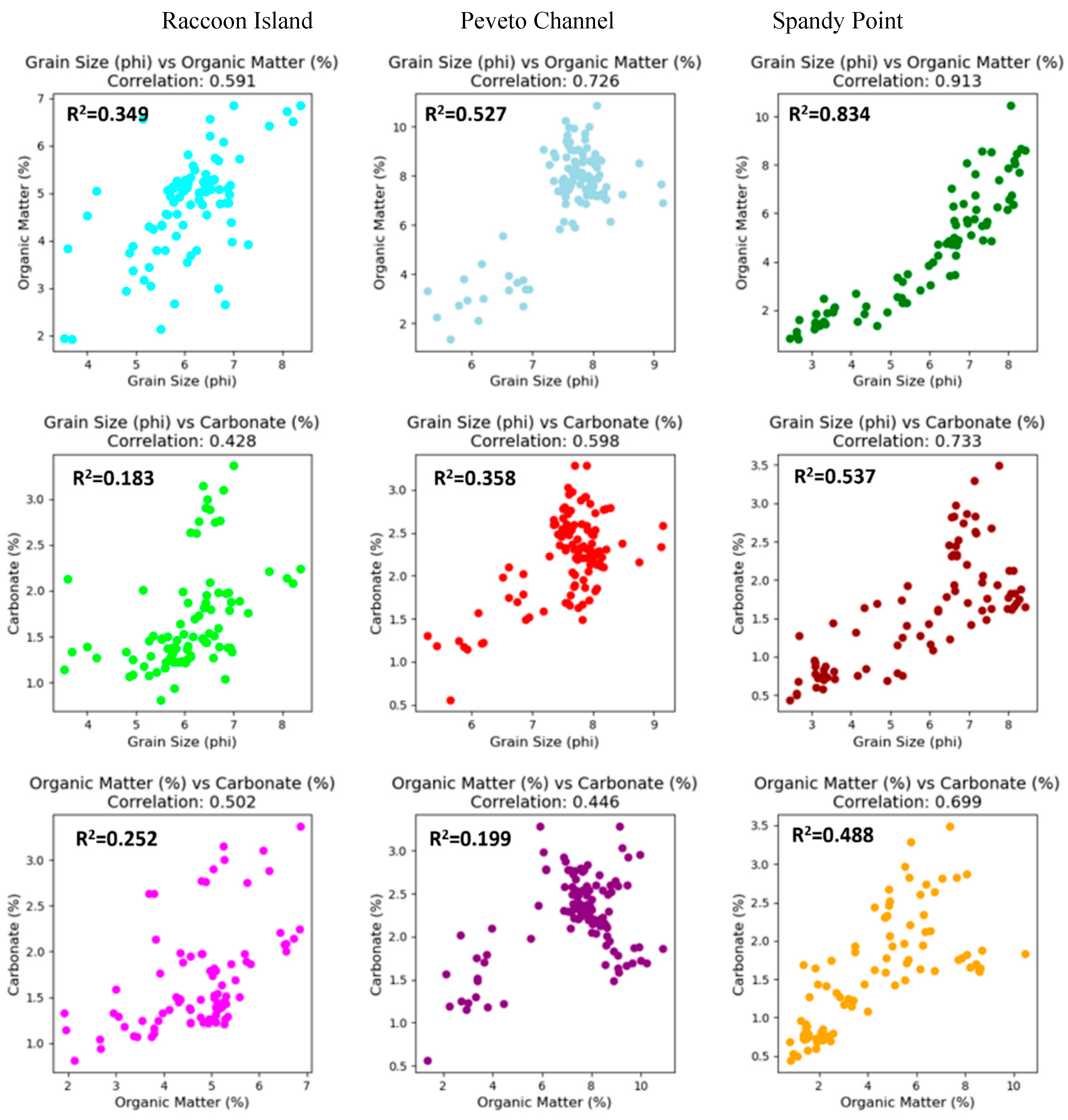

The organic matter from the Sandy Point dredge pit has the biggest IQR spreading compared to the sediment from Raccoon Island dredge pit and Peveto Channel dredge pit (

Figure S1). This is because the grain size and organic matter from the Sandy Point dredge pit has a high correlation relationship where R

2=0.834 (

Figure 6). As discussed before, the IQR of grain size from the Sandy Point dredge pit has the biggest spreading among other two dredge pits which is a result of dredging and hurricane induced landslides (

Figure 2). Besides, the organic matter from the Peveto Channel dredge pit has the smallest IQR variation. At the same time the grain size and organic matter from the peveto Channel dredge pit has a medium high correlation relationship, R

2=0.527 (

Figure 6). This could explain the smallest IQR spreading from the Peveto Channel dredge pit partially. Another possible reason is that the organic matter from the closest coastal land is the only source. Opposite to the sediment from the Sandy Point dredge pit, the correlation relationship between grain size, organic matter, and carbonate from Raccoon Island dredge pit have the smallest correlation relationship, specifically the carbonate content has the weakest correlation with grain size and organic matter (

Figure 6). This likely reflects variations in sediment sorting, resuspension, and post-depositional reworking among the sites.

Carbonate content across all pits is uniformly low (mostly 1–2%) and often approaches analytical detection limits, suggesting it plays a minimal role in sediment geochemistry. These low values are consistent with previous studies indicating that the Louisiana shelf is dominated by terrigenous input, with limited modern biogenic carbonate production ([

37]). Visual inspection of cores did not reveal significant shell material, suggesting that any carbonate present is likely in the form of fine shell hash or reworked particles rather than in-situ biological production. Variability in carbonate is highest at Sandy Point (especially inside the pit), which may be linked to broader grain size distribution caused by dredging and slope failure events (

Figure 2,

Figure S2). Meanwhile, carbonate shows weak correlation with both OM and grain size at Raccoon Island, further supporting its limited environmental relevance. Previous work in the region suggests carbonate saturation states are more strongly influenced by seasonal productivity and stratification than by sediment input ([

38]), which may explain some of the subtle variations observed here. Overall, carbonate appears to be a small component of these sediment systems.

5. Implementation and Limitation

A better understanding of the life cycle of mud capped dredge pit is significant to the post dredging sand and energy management and monitoring. Former dredge pit geomorphic evolution research using numeric model and observation methods can generally predict that a newly ‘born’ dredge pit will be filled up over time ([

11,

14,

16,

38]). In this research, we used geological data from three mud-capped dredge pits on the inner Louisiana continental shelf to study their life cycle. This dataset could be one of the biggest on the Louisiana shelf. First, Sandy Point dredge pit was excavated in 2012 and was confirmed to have a 5-meter depletion of sediment in 2022 (

Figure 1; Zhang et a., 2022, unpublished data). Therefore, Sandy Point is considered as a young post-dredging dredge pit. For this stage, it will receive sediment infilling since topographic low is generally a natural sediment trap. This stage ends when it is filled up the first time.

For Raccoon Island dredge pit, it was dredged in 2013 and filled up in 2018 ([

38]). Besides, massive degassing activities observed on the pit in 2018 and 2021 ([

38]; Zhang et al., 2021, unpublished data). Raccoon Island is then considered in the stage adult dredge pit. In this stage, the gases come from the decay of organic matter in the new sediment deposit. Our data show that the infilling sediment is still loose and is not stable. For example, a half meter pit subsidence was observed in the Raccoon Island dredge pit in 2021 (Zhang et al., 2024; to be submitted). It is highly possible that the extreme hydrodynamic conditions scour the upper most sediment in the filled-up dredge pit. In this stage, the new sediment deposit and sediment subsidence may occur mutually until the infilling sediment is consolidated. The extreme weather, like major hurricanes, could play a role in scouring the infilling sediment, different from the state one. Adult stage ends when the degassing activities stop. This leads to the ‘old dredge pit, stage three. The bubbling disappears in this stage. Sediment tends to be stable in this stage. Stage three ends when the dredged area becomes pit equilibrium which means the geological and geotechnical property of the infilling sediment in the dredge pit is like the ambient and undisturbed environment. However, mud volcanoes are a possible geological feature on the dredged area. For example, Peveto Channel dredge pit was dredged in 2003 and was confirmed filled up the first time in 2016 ([

16]). [

16] also observed multiple small mud volcanoes on the dredged area of Peveto Channel dredge pit. It is possible that the mud volcano eruption is a geomorphic feature when the dredged area on the way to pit equilibrium.

One limitation for this paper is the data bias. The dataset from the outside of the dredge pits is much smaller than the dataset inside each dredge pit. This may lead to the results from the outside dredge pit is not reliable as the results from inside the dredge pit. Density data is generated from gamma bulk density testing from vibracores. To incorporate the density variable to the multiple linear regression model, computations have been implemented on the original measured values. From S3, the density values <1.2 and >2.5 have been removed from the beginning. Secondly, if the chosen depth is missing in the density dataset, the density from the nearest depth has been filled to this depth. Thirdly, if the chosen depth and adjacent depths (within 1cm) exist, the average value of the three or two density values has been computed to represent the density for this depth. Since the density variable doesn’t match perfectly with other variables, further study may be needed to better understand the role of density in the current multiple linear regression models.

7. Conclusions

A total of eighteen vibracores from Raccoon Island dredge pit, Peveto Channel dredge pit, and Sandy Point dredge pit were used in this paper to study their grain size, density, organic matter, and carbonate content.

The conclusions are as follows:

1) The inner Louisiana continental shelf is silt dominated. Its sand composition is controlled by distance to sandy shoals and paleo river channels and the extreme weather conditions are the driving forces for sand portion transportation. Hurricanes transport the sandy sediment to its ambient muddy environment while the dredging activities create a trap for sediment infilling, like the sandy ship shoal and on the paleo river channel.

2) The organic matter and grain size has a strong correlation relationship in the sediment from Sandy Point dredge pit (R2=0.834). Density data from outside these three dredge pits are similar, however the density data inside the pits are different.

3) PCA results indicate that two principal components are confirmed and account for more than 95% of the total grain size variance. Overall, the regression analysis demonstrated that specific variables—namely, standard deviation and skewness—consistently played key roles in predicting grain size, with variations in their strength and direction across positions. The skewness emerged as a prominent factor in the RI and SP pits, while standard deviation was the most influential in the PC pit. Density was found to be particularly important in the PC pit, highlighting the varying influence of density on grain size in different environments. Moreover, organic matter and carbonate play a crucial role in increasing the grain size in RI pit, corresponding to the specific geological settings.

4) The whole life cycle of mud capped dredge pits is categorized into three stages: a) Stage one: it is a sediment infilling stage. Extreme weather could speed up the infilling stage. This stage ends when the dredge pit is filled up the first time. b) Stage two: it is a degassing stage. Sediment erosion or scouring and redeposition may happen multiple times. Stage ends when the degassing activities end. c) Stage three: it is a sediment consolidation stage. Mud volcanoes may occur. Stage three ends when the dredged area becomes pit equilibrium.

In conclusion, it seems that three mud-capped dredge pits on the inner Louisiana continental shelf are in different stages of life cycle. Sandy Point pit hasn’t been filled up yet, is still in an ‘early’ stage and still experiencing active pit wall collapses. Raccoon Island pit was filled up around 2018 (3 years after dredging) and in a ‘middle’ stage, but either sediment scouring or degassing/consolidation formed a new half meter depression. Peveto Channel was filled up in 2016 (13 years after dredging) and in a ‘late’ stage and developed mud volcanoes. Our data can be used to better predict the complete life cycle of three pits, but none of the pits reached an equilibrium with ambient geological environments yet.

8. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Box plot for organic matter data from Sandy Point dredge pit, Raccoon Island dredge pit, and Peveto Channel dredge pit. ‘Outside’ and ‘inside’ indicate the data come from inside or outside the pits. Figure S2. Box plot for carbonate content data from Sandy Point dredge pit, Raccoon Island dredge pit, and Peveto Channel dredge pit. ‘Outside’ and ‘inside’ indicate the data come from inside or outside the pits. Figure S3. Density data from inside and outside the Peveto Channel dredge pit, Raccoon Island dredge pit, and Sandy Point dredge pit. ‘Outside’ and ‘inside’ indicate the data come from inside or outside the pits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.Z. and K.X.; formal analysis, W.Z., C.J., and K.X.; funding acquisition, K.X.; methodology, W.Z.; software, W.Z. and C.J.; visualization, W.Z., A.G.; writing—original draft, W.Z.; writing—review and editing, K.X., C.J. A.G.,S.M.; Data acquisition, W.Z., K.X., A.G., O.M, N.J., C.H., M.L.

Funding

This study was funded by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Agreement Number M14AC00023 and multiple others, with Barton Rogers, Christopher DuFore, and Michael Miner serving as project officers of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. This study was also partly funded by the U.S. Coastal Research Program (W912HZ2020013) and the National Science Foundation RAPID program (2203111).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We will publish the data after acceptance. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest

References

- Presley, B. J., Trefry, J. H., & Shokes, R. F. (1980). Heavy metal inputs to Mississippi Delta sediments: a historical view. Water, Air, and Soil Pollution, 13, 481-494.

- Duxbury, J., Bentley, S. J., Xu, K., & Jafari, N. H. (2024). Temporal scales of mass wasting sedimentation across the Mississippi River Delta Front delineated by 210Pb/137Cs Geochronology. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering, 12(9), 1644. [CrossRef]

- Bokuniewicz, H. J., Cerrato, R., & Hirschberg, D. (1986). Studies in the Lower Bay of New York Harbor Associated with the Burial of Dredged Sediment in Subaqueous Borrow Pits. Marine Sciences Research Center, State University of New York.

- Cialone, M. A., & Stauble, D. K. (1998). Historical findings on ebb shoal mining. Journal of Coastal Research, 537-563.

- Van Dolah, R.F., B.J. Digre, P.T. Gayes, P. Donovan-Ealy, and M.W. Dowd. 1998. An evaluation of physical recovery rates in sand borrow sites used for beach nourishment projects in South Carolina. 77 pp.

- Byrnes, C. I., & Isidori, A. (2004). Nonlinear internal models for output regulation. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 49(12), 2244-2247. [CrossRef]

- Ribberink, J. S., Roos, P. C., & Hulscher, S. J. (2005). Morphodynamics of Trenches and Pits under the Influence of Currents and Waves—Simple Engineering Formulas. In Coastal Dynamics 2005: State of the Practice (pp. 1-13).

- Van Run, L. C., Soulsby, R. L., Hoekstra, P., & Davies, A. G. (2005). SANDPIT: Sand Transport and Morphology of Offshore Sand Mining Pits. Process knowledge and guidelines for coastal management. End document May 2005, EC Framework V Project No. EVK3-2001-00056, Aqua Publications The Netherlands.

- Kennedy, A. B., Slatton, K. C., Starek, M., Kampa, K., & Cho, H. C. (2010). Hurricane response of nearshore borrow pits from airborne bathymetric lidar. Journal of waterway, port, coastal, and ocean engineering, 136(1), 46-58. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Xu, K., Li, B., Han, Y., & Li, G. (2019). Sediment identification using machine learning classifiers in a mixed-texture dredge pit of Louisiana shelf for coastal restoration. Water, 11(6), 1257. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z., Wilson, C. A., Xu, K. H., Bentley, S. J., & Liu, H. (2022). Sandy Borrow Area Sedimentation—Characteristics and Processes Within South Pelto Dredge Pit on Ship Shoal, Louisiana Shelf, USA. Estuaries and Coasts, 1-19.

- Obelcz, J., Xu, K., Bentley, S. J., O’Connor, M., & Miner, M. D. (2018). Mud-capped dredge pits: An experiment of opportunity for characterizing cohesive sediment transport and slope stability in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 208, 161-169. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M. C. (2017). Mud-Capped Dredge Pit Evolution in Two Northern Gulf of Mexico Sites: What They Add to Our Understanding of Continental Shelf Sedimentation. [MS: Louisiana State University. In Master of Science Thesis. Louisiana State University Baton Rouge.

- Wang, J., Xu, K., Li, C., & Obelcz, J. B. (2018). Forces driving the morphological evolution of a mud-capped dredge pit, northern Gulf of Mexico. Water, 10(8), 1001. [CrossRef]

- Nairn, R.B., Langendyk, S.K., and Michel, J., (2004), “Preliminary Infrastructure Stability Study, Offshore Louisiana”: U.S. Department of Interior, Minerals Management Service, Gulf of Mexico Region, New Orleans, LA, OCS Study, MMS 2005-043, 179 p. with appendices.

- Nairn, R. B., Lu, Q., & Langendyk, S. K. (2005). A study to address the issue of seafloor stability and the Impact on Oil and Gas infrastructure in the Gulf of Mexico. US Dept. of the Interior, MMS, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, New Orleans, LA OCS Study MMS, 43, 179.

- Robichaux, P., Xu, K., Bentley, S. J., Miner, M. D., & Xue, Z. G. (2020). Morphological evolution of a mud-capped dredge pit on the Louisiana shelf: Nonlinear infilling and continuing consolidation. Geomorphology, 354, 107030. [CrossRef]

- Broussard, L., & Boustany, R. (2005). Restoration of a Louisiana barrier island: Raccoon Island case study. In Proceedings of the 14th Biennial Coastal Zone Conference, New Orleans, Louisiana, July (Vol. 17).

- Zhang, W., Xu, K., Alawneh, O., Jafari, N. (2024). Hurricane Induced Deposition and Erosion: A Case Study Near a Dredge Pit on Inner Louisiana Shelf, BOEM Sand Management Working Group Meeting, New Orleans, LA (poster presentation).

- Obelcz, J., Xu, K.H., Bentley, S.J., O’Connor, M., Miner, M., 2018. Mud-capped dredge pits: An experiment of opportunity for characterizing cohesive sediment transport and slope stability in the northern Gulf of Mexico, Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 208, 161-169. [CrossRef]

- Kindinger, J., Flocks, J., Kulp, M., Penland, S., Britsch, L. D., Brewer, G., ... & Ferina, N. (2001). Sand resources, regional geology, and coastal processes for the restoration of the Barataria barrier shoreline (No. 2001-384). US Geological Survey.

- Zhang, W., Xu, K., Herke, C., Alawneh, O., Jafari, N., Maiti, K., ... & Xue, Z. G. (2023). Spatial and temporal variations of seabed sediment characteristics in the inner Louisiana shelf. Marine Geology, 463, 107115. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G., Liu, J., Liu, S., Wang, Z., Hu, G., & Kong, X. (2016). Modern muddy deposit along the Zhejiang coast in the East China Sea: Response to large-scale human projects. Continental Shelf Research, 130, 68-78. [CrossRef]

- Heiri, O., Lotter, A. F., & Lemcke, G. (2001). Loss on ignition as a method for estimating organic and carbonate content in sediments: reproducibility and comparability of results. Journal of paleolimnology, 25, 101-110. [CrossRef]

- Gloor, G. B., Macklaim, J. M., Pawlowsky-Glahn, V., & Egozcue, J. J. (2017). Microbiome datasets are compositional: and this is not optional. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, 294209. [CrossRef]

- Flood, R. P., Orford, J. D., McKinley, J. M., & Roberson, S. (2015). Effective grain size distribution analysis for interpretation of tidal–deltaic facies: West Bengal Sundarbans. Sedimentary Geology, 318, 58-74. [CrossRef]

- Duquesne, A., & Carozza, J. M. (2023). Improving grain size analysis to characterize sedimentary processes in a low-energy river: A case study of the Charente River (Southwest France). Applied Sciences, 13(14), 8061. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.H., Harris, C.K., Hetland, R.D., Kaihatu, J. M., 2011. Dispersal of Mississippi and Atchafalaya Sediment on the Texas-Louisiana Shelf: Model Estimates for the Year 1993, Continental Shelf Research, 31, 1558-1575. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.H., Wang*, J., Li, C., Bentley, S., Miner, M., 2022. Geomorphic and Hydrodynamic Impacts on Sediment Transport on the Inner Louisiana Shelf. Geomorphology, 108022, . [CrossRef]

- Denommee, Kathryn C., Samuel J. Bentley, Dario Harazim, and James HS Macquaker. “Hydrodynamic controls on muddy sedimentary-fabric development on the Southwest Louisiana subaqueous delta.” Marine Geology 382 (2016): 162-175. [CrossRef]

- Obelcz, J., Xu, K., Bentley, S. J., Li, C., Miner, M. D., O’Connor, M. C., & Wang, J. (2016). Evolution of mud-capped dredge pits following excavation: sediment trapping and slope instability. NASA Astrophysics Data System.

- Bomer IV, E. J. (2019). Coupled Landscape and Channel Dynamics Across the Ganges-Brahmaputra Tidal-Fluvial Continuum, Southwest Bangladesh. Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College.

- Hedges, J. I., & Keil, R. G. (1995). Sedimentary organic matter preservation: an assessment and speculative synthesis. Marine chemistry, 49(2-3), 81-115. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Xu, K., Bentley, S. J., White, C., Zhang, X., & Liu, H. (2019). Degradation of the plaquemines sub-delta and relative sea-level in eastern Mississippi deltaic coast during late holocene. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 227, 106344. [CrossRef]

- Goñi, M. A., Ruttenberg, K. C., & Eglinton, T. I. (1998). A reassessment of the sources and importance of land-derived organic matter in surface sediments from the Gulf of Mexico. Marine Geology, 152(1–3), 105–121. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, M. C., Bentley, S. J., Xu, K., Obelcz, J., Li, C., & Miner, M. D. (2016, February). Sediment infilling of Louisiana con-tinental-shelf dredge pits: a record of sedimentary processes in the Northern Gulf of Mexico. In American Geophysical Union, Ocean Sciences Meeting (Vol. 2016, pp. EC34C-1206).

- Vincent, S., Wilson, C., Snedden, G. A., & Quirk, T. (2025). Time-Varying Rates of Organic and Inorganic Mass Accumulation in Southeast Louisiana Marshes: Relationships to Sea-Level Anomalies and Tropical Storms. Journal of Coastal Research. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, H. H., Sassen, R., & Aharon, P. (1987, April). Carbonates of the Louisiana continental slope. In Offshore Technology Conference (pp. OTC-5463). OTC.

- Liu, H., Xu, K., & Wilson, C. (2020). Sediment infilling and geomorphological change of a mud-capped Raccoon Island dredge pit near Ship Shoal of Louisiana shelf. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 245, 106979. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).