1. Introduction

The rising global population and continuously increasing energy demand result in the rapid depletion of fossil fuels. The over-consumption of fossil fuels adversely impacts the environment by the emission of greenhouse gases (GHG), specifically CO

2 [

1]. Alternatively, renewable energy sources like algal biofuels are more appealing due to their high capacity for carbon capture and storage [

2]. Algae are a group of unicellular and multicellular photosynthetic autotrophs living in aquatic environments [

3]. Algae are classified into two categories: microalgae and macroalgae based on their size and morphological characteristics. Based on visible pigments they are further classified into red, green, and brown algae, that can be easily grown in nutrient rich wastewater [

4]. Algae is a low-cost feedstock to produce biofuels and bio-based products. Algal biomasses are rich in lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins, making it suitable to produce biodiesel, bioethanol, hydrogen, and syngas. Among various species brown algae are exploited more to produce biofuels [

5]. Algal biofuel production is more economically reliable due to the low space requirement for their growth, and high capacity to reduce carbon dioxide. Cultivation of microalgae requires light, water, carbon dioxide, and nutrients for their growth. Algal biomasses can grow 20-20 times more efficiently than nutritional crops, and their lipid content is approximately 30 times more than the lignocellulosic feedstocks. The metabolic engineering techniques further enable algae to produce more lipids and carbohydrates in the biomass [

2].

To produce algal biofuels various catalytic steps are important in the biorefinery system. For example, the transesterification process is required to convert algal lipids (oils) into biodiesel by breaking ester bonds with catalysts such as sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or potassium hydroxide (KOH). Similarly, the hydrothermal liquefaction technique is used to produce valuable biocrude oil by processing algal biomass at high temperature [

6]

. Moreover, syngas obtained from algal biomass through the gasification can be further converted into liquid biofuels or valuable chemicals [

7]. The role of the catalyst is important during gasification process to facilitate the efficient conversion of algal biomass into biofuels for various applications, including transportation, industry, and power generation [

8,

9].

However, efficient and scalable technology enabling the conversion of algae into biofuels remains challenging due to high input energy cost and variability of lipid composition in biomass samples. Biofuels derived from algal biomass might be a viable solution for long-term climate change mitigation and energy sourcing [

10]1 Life cycle assessments and techno-economic analyses may further support the feasibility of an algal biorefinery system. Furthermore, interdisciplinary research collaboration, public-private partnerships, and supportive government policies are essential for unlocking the potential of algae-based biofuels [

11,

12]. Algal biorefinery integrated with wastewater bioremediation and a combined CO

2 sequestration approach offer more carbon credits to biofuels [

13]. Nevertheless, numerous obstacles need to be overcome for the large-scale production and commercialization of biofuels from algal biomass to fulfill the world’s energy needs. The focus of this review is to discuss algal cultivation, harvesting, and processing to produce biofuels using various catalytic strategies. Additionally, technological advancements in algal biofuel production, government policies, key regulatory issues, challenges, and future perspectives for sustainable biofuel production are reviewed.

2. Algal Biomass: Composition and Biofuel Potential

2.1. Types of Algae

Algae is a diverse group of photosynthetic organisms, representing a promising feedstock for biofuel production due to their rapid growth rates, minimal land use, and ability to thrive in various aquatic environments [

14]. Algae can be classified into two main categories based on size and cellular organization. Microalgae are microscopic, predominantly unicellular organisms, meanwhile macroalgae are multicellular organisms which are commonly known as seaweeds. Each category possesses distinct biological and chemical characteristics that influence their suitability and methods used for biofuel conversion. Understanding the inherent differences between microalgae and macroalgae is critical for optimizing algae-based biofuel processes and improving their economic viability. Microalgae are microscopic, unicellular or colonial organisms primarily found suspended in water. They are photosynthetic organisms that efficiently convert sunlight, CO

2, and nutrients into biomass. It includes green algae (Chlorophyceae), diatoms (Bacillariophyceae), blue-green algae (cyanobacteria), and other groups distinguished by pigment composition [

15]. In contrast, macroalgae are multicellular marine algae (seaweeds) such as brown algae (Phaeophyceae), red algae (Rhodophyceae), and green seaweeds (Chlorophyceae macroforms), which can often be seen with the naked eye [

15,

16]. Algal biomass is mainly composed of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates, but the proportion of these components varies between different algae taxa and growth conditions [

17,

18]. Microalgae are especially variable in composition as certain strains are protein-rich (up to 70% protein), whereas others can accumulate large quantities of lipids (7-65% of dry weight) [

19,

20]. For nitrogen starvation or other stresses can divert microalgal metabolism, resulting in lipid accumulation with reduced protein content [

21]. On the other hand, some microalgae store carbohydrates like starch or β-glucans where typical biochemical composition of algae species showed 10% lipids, 25% carbohydrates, and 40% proteins when cultivated under full medium as well as 1.7 to 24.2% β-glucans based on dry weight [

22]. In all cases, microalgae lack the hard lignocellulosic structures found in land plants with the cell wall made of polysaccharides and glycoproteins, which aids in downstream processing for fuels.

Macroalgae exhibits a different compositional profile. They are generally rich in carbohydrates (32-60% dry weight) and contain moderate protein levels (7-31% dry weight), but relatively low lipid content (2-13% dry weight) [

23]. The predominant carbohydrates differ by algal group as brown algae synthesize polysaccharides like alginate, laminarin and mannitol, red algae produce galactans such as agar and carrageenan, and green seaweeds contain ulvan and other glucans. These polysaccharides serve as energy reserves or structural components and are readily convertible to fermentable sugars. Notably, macroalgae are essentially free of lignin, a polymer that confers recalcitrance in terrestrial biomass [

24]. The minimal presence of lignin in macroalgae makes it easier to hydrolyze for biofuel production compared to woody or grass feedstocks. Meanwhile, the high potassium or other extractive content in macroalgae requires alternative refinery procedure than lignocellulosic biomass. Although macroalgae contain less lipids than microalgae, certain red and brown algae have beneficial long-chain fatty acids such as eicosapentaenoic (EPA), decosahexaenoic (DHA), and alpha-linolenic (ALA) in low proportions [

20]. In addition, the high carbohydrate content of macroalgae and lack of lignin make them attractive for bioconversion to biofuels via fermentation or anaerobic digestion.

2.2. Advantages over Other Biomass Sources

Algae-based feedstocks offer several distinct advantages over traditional terrestrial biomass for biofuel production. Especially microalgae can achieve remarkably high areal productivity compared to land plants, where microalgae cultivation required1.2×10

6 ha of pastureland to produce 41.5×10

9 Lyr

-1 of biofuels while terrestrial biomass required 14.0×10

6 ha [

25,

26]. Many microalgae can double their biomass in a matter of hours under optimal conditions, enabling multiple harvests in a single week. This superior productivity means that algae require much less cultivation area to produce the same amount of biofuel, making it attractive for scaling up bioenergy without straining land resources. Moreover, biomass production can be continuous and is not tied to seasonal harvest cycles, further enhancing annual yields. In addition, unlike first-generation biofuel feedstocks such as corn, sugarcane, and palm oil, algae do not compete directly with food crops for arable land or freshwater. Algae can be grown on non-arable land, including deserts, saltwater coastlines, or even in contained photobioreactors on marginal sites [

27]. This means biofuel algae cultivation avoids displacing food production or driving up food prices [

26]. In addition, many algae utilize waste resources, where growing in nutrient-rich wastewater or using CO

2 from industrial flue gases can further reduce competition with agricultural inputs [

27,

28]. By not requiring fertile soil or edible feedstocks, algal biofuels offer a path to sustainable energy that sidesteps dilemma between food and fuel that plagues crop-based biofuels.

Algae not only serves as biomass feedstock but also as a tool for carbon capture. Through photosynthesis, algae efficiently fix carbon dioxide into organic biomass. In fact, microalgae can fix CO

2 10-50 times faster than terrestrial plants on an area basis. Especially, microalgae showed superior sequestration ability where 1kg of dry microalgae can capture1.3-2.4 kg CO

2 [

29]. This high carbon sequestration efficiency means that large scale algal cultivation could be coupled with industrial CO

2 sources to biologically capture and recycle carbon [

30]. The captured CO

2 is converted into algal biomass, which can then be converted to biofuel, closing the loop in a carbon-neutral or even carbon-negative cycle [

31]. Implementing algae for biofuels therefore has the dual benefit of producing renewable energy while actively removing CO

2 from the atmosphere or industrial flue gas streams. This contrasts with terrestrial biomass which grows slower and often cannot be situated adjacent to point sources of CO

2. Algal systems can be collocated with factories to uptake CO

2 which contributes to greenhouse gas mitigation in addition to displacing fossil fuels. In summary, algal biomass offers superior productivity, sustainability, and integrative environmental benefits compared to conventional biomass sources. Algae can yield more fuel per area without impinging on food resources and help capture CO

2 from the atmosphere. These advantages underscore why algae are widely regarded as one of the most promising resources for next-generation biofuels and a cornerstone of future bioenergy strategies [

29,

31].

3. Cultivation and Harvesting of Algae

Table 1 summarizes the major cultivation approaches used to produce algal biomass. Cultivation and harvesting are critical steps in producing biofuels from algae. The cultivation stage determines the quantity and composition of biomass available while harvesting and dewatering techniques greatly influence downstream processing efficiency. This section reviews major cultivation approaches, including the key environmental and nutritional parameters for algal growth, and the strategies for harvesting and dewatering algal biomass [

32].

3.1. Cultivation Systems

3.1.1. Open Raceway Ponds

Open race way ponds are shallow, oval-shaped basins where algae are grown in water mixed by a paddlewheel [

32]. They are one of the most economical options for large-scale microalgae cultivation due to low construction and operating costs. Raceway ponds typically operate at a water depth of 0.35-0.80 m and rely on natural sunlight and ambient conditions [

32,

38]. The advantages include simple design, low energy input, and the capacity to culture large volumes of algae with minimal infrastructure. However, open ponds have notable limitations as light utilization is often inefficient in deeper layer, leading to lower biomass productivity than closed reactors [

34]. The typical volumetric productivities in raceway ponds are 0.01-0.12 gL

-1day

-1, which is lower than those achieved in optimized photobioreactors [

33]. In addition to the low productivity, the following challenge with open pond cultivation is the CO

2 outgassing due to change in pH of water [

39]. On the other hand, the studies report that significant nitrogen can be lost as ammonia in open ponds up to 73% of supplied N

2 due to stripping under high pH and temperature. Despite these issues, open raceway ponds remain widely used for microalgae, especially in warm climates because their low capital and maintenance costs enable economical biomass production at scale [

34,

40].

3.1.2. Closed Photobioreactors

Photobioreactors (PBRs) are enclosed with cultivation systems that provide a controlled environment for algal growth. PBR comes in various designs, including tabular reactors, flat-panel reactors, columns, and even novel geometries, intended to maximize light capture and growth surface area [

35]. In closed PBRs, parameters such as light, temperature, and gas exchange can be tightly regulated, enabling higher cell densities and productivities than open ponds. The flat-panel and tubular PBRs sustain volumetric biomass productivities of 1.5-1.6 gL

-1day

-1 under optimal conditions, which exceeds the typical open-pond yields [

33]. The controlled conditions also reduce contamination risk and allow cultivation of monocultures for extended durations [

34]. PBR systems have demonstrated superior photosynthetic efficiency and nutrient uptake rates, which is beneficial for applications like biofuel feedstock or wastewater remediation. However, these advantages come at significantly higher cost since close PBRs require cost for building infrastructures and higher energy inputs for pumping, mixing, and cooling, leading to high capital and operating expenditures [

36]. Fouling of reactor surfaces by biofilm buildup and oxygen accumulation are additional operational challenges that can reduce efficiency over time. In recent years, numerous advancements have been made to improve PBR performance and scalability. Innovative configurations include rotating or inclined PBRs for better light exposure, membrane-based PBRs that grow algae as biofilms, and internally illuminated or thin-layer BPR designs to overcome light limitation in dense cultures. For instance, researchers have developed PBRs with rotating membrane surfaces and spiral-flow or air-lift mechanisms to enhance mixing and CO

2 mass transfer, Hybrid systems have also been explored, combining closed and open cultivation stages. One study showed that coupling a closed PBR with as wastewater-fed open pond helped boosting overall biomass production as it recorded 46.3-74.3% improvement compared to open pond and 12.5% higher than PBRs. Such approaches seek to leverage the high productivity of PBRs with the low cost of open ponds [

41]. In summary, closed PBRs are well-suited for high-value products and sensitive strains, and continued design improvements are making them more feasible for large-scale biofuel application, but cost-effectiveness remains a key concern for commercial deployment.

3.1.3. Wastewater-Based Cultivation

An attractive strategy to reduce nutrient input costs is growing algae in nutrient-rich waste streams, such as municipal, agricultural, or industrial wastewater. Algal cultivation in wastewater is often performed in modified open pond systems, commonly high-rate algal pond (HRAP) designed for wastewater treatment. In these systems, microalgae typically grow in consortia with naturally occurring bacteria, simultaneously uptaking nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater while the bacteria help decompose organic pollutants. This symbiotic setup provides dual benefits where it bio-remediates wastewater and produces algal biomass that cultivation is cost-effective and sustainable because growth medium itself is a waste that would otherwise require treatment. The past decade has seen successful pilot and full-scale demonstrations of wastewater fed algal ponds achieving substantial nutrient removal with 62-65% removal of COD, and 25-49% of N and P [

34]. However, operating algae systems on wastewater also presents challenges. Environmental factors and fluctuations in wastewater composition causes variability in algal productivity. Contamination control is difficult open wastewater ponds, so typically robust strains like

Chlorella or

Scenedesmus dominate, and invasive species may appear if conditions shift. Biomass yields in wastewater systems are generally lower than in refined media since HRAP treating primary sewage might reach biomass productivities on the order of 0.03-0.05 gL

-1day

-1, which is modest compared to optimized PBR systems [

37]. Close PBRs can also be used for wastewater, offering better control and higher nutrient removal rates, but their expense often precludes use in routine water treatment. A compromise approach is to use wastewater after conventional primary treatment in a controlled PBR or to employ two stage system. An initial HRAP for bulk nutrient removal and algal growth that is followed by a smaller PBR polishing stage. Overall, wastewater-based cultivation has emerged as a globally relevant strategy to cut fertilizer costs and improve sustainability in algal biofuel production, especially when aligned with wastewater management goals [

42].

3.2. Growth Conditions and Nutrient Requirements

Algae have specific requirements for light, temperature, carbon dioxide, and nutrients to achieve optimal growth. Manipulating these growth conditions is essential to maximize biomass productivity for biofuel applications. As photosynthetic organisms, algae depend on sufficient light energy for growth. Light is often the limiting factor in dense cultures, and providing an optimal light intensity is crucial [

43]. For microalgae, typical optimal irradiance levels range from about 37.5 to 2500 µmol photons over m

2s, depending on the species and acclimation state [

44]. At low light, growth is light-limited, while excessive light can cause photoinhibition and cellular damage. Most microalgae have a photosynthetic saturation point beyond which additional light does not increase net growth. Many chlorophyte microalgae lie in the range of a few hundred µmol/m

2·s. Outdoor cultures receive fluctuating natural sunlight, therefore cells experience cycles of light and shade. This can be beneficial up to a point, as brief dark periods allow recovery from excess light [

43,

44].

Temperature and light also interact as higher temperatures can raise the light saturation threshold by increasing enzyme activity, up to the species’ limit [

45]. Most algal species used for biofuel are mesophilic, with optimal growth temperatures in the range of 20-25°C, whereas the growth rate tends to decrease after 25°C [

46,

47]. Temperature above the optimum lead to decreased growth due to enzyme denaturation and membrane damage, while temperatures significantly below optimum slow down enzymatic reactions and cell division rates. Diurnal and seasonal temperature fluctuations are important considerations, especially for outdoor cultivation. Open ponds experience daily temperature swings, thus high-density cultures can sometimes self-regulate to a degree, but extreme heat or cold will stress the algae. Closed PBRs can be equipped with temperature control to maintain near-optimal conditions, albeit at an energy cost [

47].

In addition to light intensity and temperature control, CO

2 and nutrients also affect algal growth. Inorganic carbon is the carbon source for photosynthetic algae, and its availability often limits growth, especially in dens cultures. Atmospheric CO

2 at approximately 0.04% saturation can support only modest algal growth. Therefore, sparging cultures with concentrated CO

2 is a common practice to enhance productivity. Typically, 20% CO

2 v/v aeration gas is used in cultivation to achieve high biomass yields, and this also serves to control pH as CO

2 dissolution counteracts the rise in pH from algal carbon uptake [

48]. Efficient CO

2 delivery systems including bubble diffusers and gas recycling loops have been developed to improve carbon fixation rates. Meanwhile, algae required macronutrients such as nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P), in substantial amounts for growth, as these elements are building blocks of proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids. Typically, nitrogen is supplied as nitrate (NO

3-) or ammonium (NH

4+) salts, and phosphorus is supplied as phosphates. Many cultivation protocols maintain an excessive N and P to ensure none comes limiting during the growth phase [

49]. If N or P is depleted, algae can experience nutrients stress. In nitrogen limitation, microalgae slow down the growth and diverts metabolism toward storage compounds like lipids or carbohydrates. Therefore, for maximal biomass production, nutrient sufficiency is maintained. Standard growth media such as BG-11 and Guillard’s f/2 medium provide a balanced supply of N, P, and trace nutrients. These defined media support high growth rates in laboratory culture [

50].

3.3. Harvesting and Dewatering Techniques

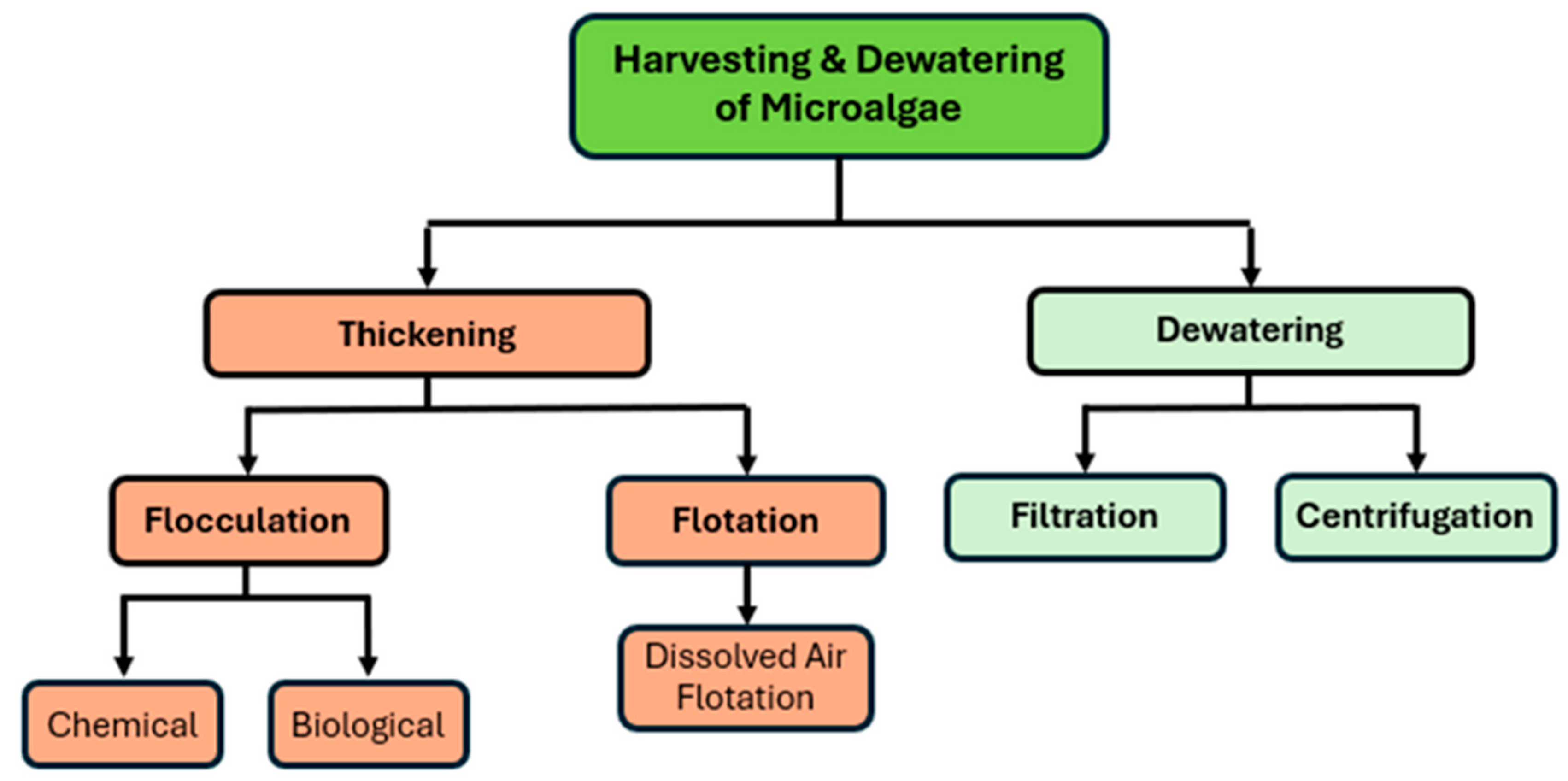

The overview of microalgae harvesting and dewatering techniques is shown in

Figure 1. After cultivation, algae must be harvested and dewatered to obtain a concentrated biomass suitable for biofuel conversion. This step can be technically challenging and energy-intensive, especially for microalgae, which are typically unicellular and suspended at low concentrations in the culture broth. Efficient harvesting is crucial as it accounts for a large fraction of the total production cost and energy input in algal biofuel production. Numerous harvesting and dewatering methods have been developed in the past decade, ranging from traditional processes such as centrifugation and filtration to novel techniques like electrochemical flocculation and magnetic separation. The choice of method depends on the type of algae, the desired dryness of the output, cost constraints, and scale of operation [

51].

3.3.1. Filtration

Filtration involves passing the algal suspension through porous membrane or filter medium to separate cells from water. It is a widely used method to concentrate microalgae, particularly effective for larger cells or for obtaining a clear filtrate. Traditional filters can perform bulk harvesting, but modern systems employ membrane filtration that uses microfiltration or ultrafiltration membranes with pore sizes small enough to retain algal cells [

52]. Membrane based harvesting has seen considerable research attention, focusing on mitigating membrane fouling which is a major hurdle. Strategies like using tangential filtration, vibrational membranes, or periodic back flushing have been developed to maintain flux and extend membrane life [

53]. Forward osmosis has also been investigated, where a draw solution pulls water out of the algal culture through a semi-permeable membrane, thus concentrating the algae without heavy pumping requirements [

54]. The advantage of filtration is that it can achieve a high concentration factor and even potentially recycle the purified water or media. Especially for commercial membranes such as polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), polyethersulfone (PES) have been used to harvest microalgae species

Aurantiochytrium with 97.3 to 99.9% harvesting efficiency in pilot tests. However, membrane costs and fouling remain concerns for very large-scale use. Recent advancements include developing antifouling coatings and employing dynamic membranes. Overall, filtration is often used in combination with other methods such as flocculation or centrifuge to balance efficiency and cost [

55].

3.3.2. Centrifuge

Centrifugal separation is a mechanical method that uses rotational force to accelerate the sedimentation of algal cells. It is a fast and effective technique to achieve high concentration factors. Disc-stack centrifuges and decanter centrifuges are commonly employed in algae harvesting [

56]. The main drawback is the high energy consumption and operational cost of continuous centrifugation. As centrifuges are often reserved for higher-value products or as a final polishing step after a bulk harvesting method has preconcentrated the biomass. Research in the past decade has aimed at increasing the throughput and energy efficiency of centrifuges and on harvesting aids that make cells easier to centrifuge. Despite the cost, centrifugation remains a reliable harvesting method, yielding recovery efficiencies above 90% under low flow rate. It is particularly useful for sensitive products where chemical additives cannot be used [

57].

3.3.3. Flocculation

Flocculation is the process of aggregating microalgal cells into larger clumps that can then be more easily removed by sedimentation, filtration, or flotation. By overcoming the cells’ natural tendency to stay suspended, flocculation facilitates bulk harvesting. Chemical flocculation involves adding coagulants or flocculants that neutralize charges or form bridging between cells. Common chemical flocculants include multivalent metal salts like aluminum sulfate or ferric chloride, and cationic polymers such as polyaluminum chloride or polyacrylamide. These substances have been shown to achieve high flocculation efficiencies with low dosages for many microalgae. For example, chitosan and cationic starch are popular green flocculants that can aggregate cells without heavy metals [

58,

59]. The downside of chemical flocculation is that the added chemicals may contaminate the biomass and may require removal or pH adjustment after use. An alternative is bioflocculation, where flocs form due to biological agents or conditions. Certain filamentous fungi or bacteria co-culture with microalgae and induce natural flocculation where the reported harvest efficiency using fungi-algae was near 90% [

60,

61].

3.3.4. Flotation

Flotation techniques harvest algae by introducing fine bubbles into the culture, which attach to algal cells and float them to the surface as foam or scum, which can then be skimmed off [

62]. The most common is Dissolved Air Flotation (DAF), which is used in water treatment, where water is supersaturated with air at high pressure and then released to atmospheric pressure in a tank, forming a cloud of microbubbles that lift suspended particles [

63]. In algal applications, DAF can achieve high separation efficiency near 87% which can further be improved when algae are first flocculated or conditioned with surfactants to promote bubble attachments. Flotation is attractive because it can process large volumes with relatively low energy compared to centrifugation. It works best at lower algal densities and for algae that readily adhere to bubbles. The past decade saw improvements in electro-flotation, an electrochemical method where bubbles of hydrogen and oxygen are generated in the culture by water electrolysis, carrying algae upward. Electroflotation units that are combined with electrocoagulation have been designed to harvest algae without chemical additives. Such methods show promises for low cost and continuous operation, thus the scale up and energy optimization are still being refined [

63,

64].

4. Conversion Pathways for Algal Biofuels

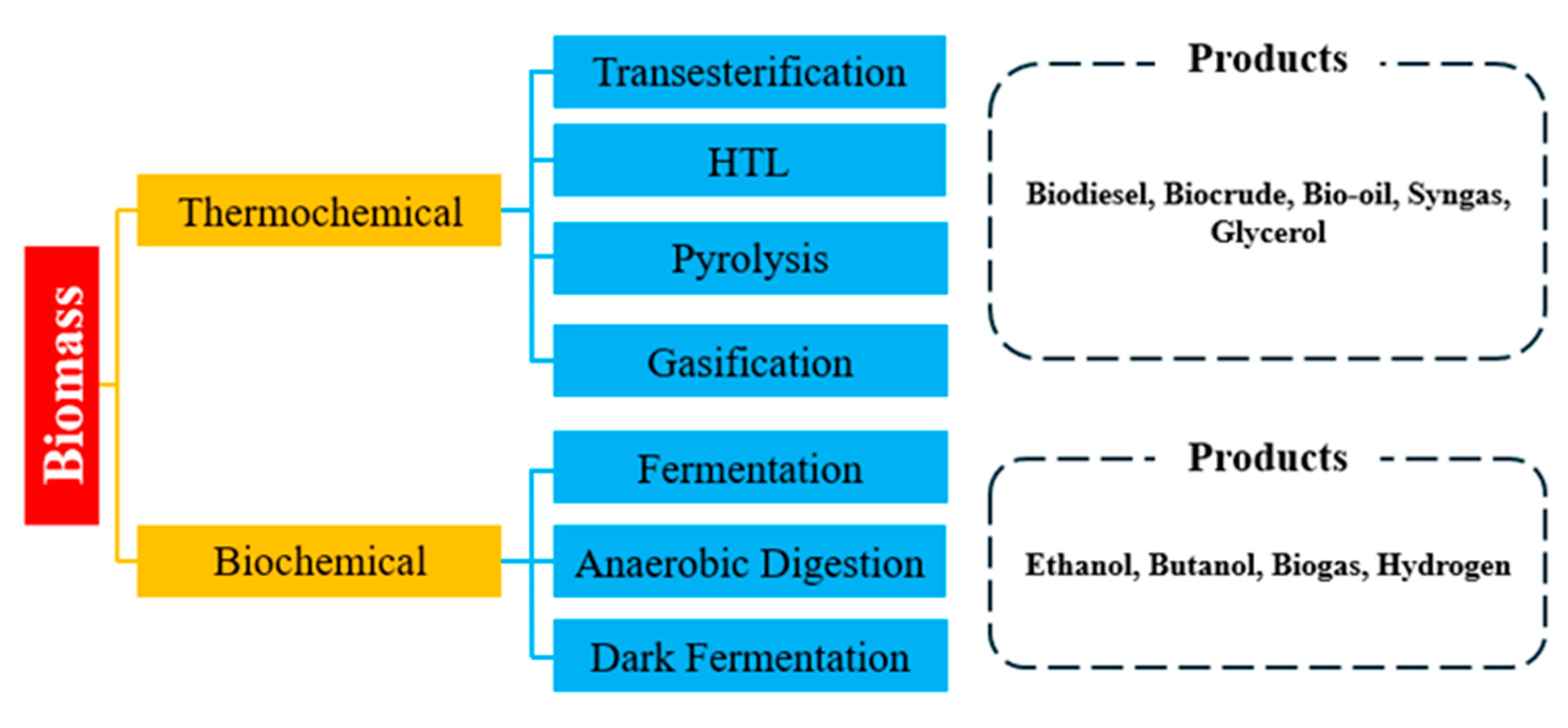

Algal biomass can be converted into various biofuels through multiple pathways which can be categorized into lipid-based chemical conversion, thermochemical processes, and biochemical processes as shown in

Figure 2. Each pathway targets different macromolecular fractions of algae and yields distinct fuel products. Microalgae are often rich in lipids and thus well-suited for biodiesel production via lipid extraction and transesterification. In contrast, macroalgae typically contain lower lipid content and higher carbohydrate fractions, making it more amenable to fermentation or direct thermochemical liquefaction rather than lipid extraction [

65].

4.1. Lipid Extraction and Transesterification

Microalgal biodiesel production traditionally involves extracting lipids from algal cells followed by transesterification into fatty acid alkyl esters. Efficient lipid extraction from microalgae is challenging due to robust cell walls and high-water content. Therefore, a variety of extraction methods have been developed, including mechanical cell disruption, solvent extraction, and supercritical fluid techniques. Physical methods including milling, and sonication are used to rupture algal cell walls and facilitate lipid release. These techniques can significantly improve solvent penetration and lipid yield by overcoming the rigid microalgal cell wall [

66]. Mechanical methods are relatively simple and scalable, but they often require high energy input and are typically combined with solvents to recover the released oils. Alternatively, solvent-based extraction is widely used which is using chemical solvents including methanol, chloroform, or NaCl to dissolve and extract lipids from dried algal biomass [

67]. Solvent extraction achieves high recovery yields but must contend with solvent recycling, flammability, and potential toxicity issues. Lastly, supercritical fluid extraction utilizes supercritical state CO

2 which is environmentally benign technique to extract lipids without organic solvents, using CO

2 at high pressure and temperature to solubilize non-polar lipids [

68]. Supercritical CO

2 yields high quality oils and avoids solvent residues. However, it may require co-solvents or cell disruption pretreatments to achieve high recovery from the wet algal past. Its scalability is proven in other industries, but the high-pressure equipment leads to greater capital cost. Liquefied dimethyl ether (DME) has emerged as an alternative subcritical solvent that can extract lipids from wet algae efficiently due to its low boiling point and ability to penetrate water-rich biomass [

69].

After extraction, the algal lipids are converted to biodiesel throughout transesterification. Non-catalytic transesterification requires short chain alcohol such as methanol or ethanol to convert microalgae into fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) [

70]. However, higher yield can be achieved when this reaction is catalyzed by acids, bases, or enzymes, which yields FAME or ethyl ester (FAEE) and glycerol as a co-product. Especially for base-catalyzed reaction, NaOH is commonly used for biodiesel due to their fast reaction kinetics [

71]. In fact, base catalyzed transesterification can be 4000 times faster than acid-catalyzed processes. However, base catalysts require feedstock oils with low free fatty acid (FFA) content [

70,

72]. If FFA is greater than 0.5% of oil weight, saponification will occur, which consumes catalyst and emulsifies the product which ultimately reduces biodiesel yield and complicating separation [

73]. Thus, for refined algal oils with low FFA, base catalysts achieve high conversion and are economically attractive. In contrast, acid catalysts such as H

2SO

4, and HCl can simultaneously catalyze transesterification of triglycerides and esterification of FFAs to biodiesel, making the process suitable for lower quality oils or wet algal biomass containing FFA [

74]. Homogeneous acid catalysis is tolerant of high FFA and moisture which is often employed in a two-step process for algal oils with significant FFA. However, acid catalysts are much slower and typically require higher temperatures at lower than 100°C and a large excess of methanol to drive the reaction. They also cause equipment corrosion and necessitate extensive product washing to remove the catalyst with waste production [

73,

74].

Lipase enzymes offer a biocatalytic route to produce biodiesel under mild conditions. Enzymatic transesterification operates at 30-60°C and pH range of 3.0-9.0 for recovery and reusability of the enzymes [

75,

76]. Enzymes work with wet biomass or directly on algal paste, and immobilized lipases can be reused for multiple batches. These advantages such as no strong chemicals, lower energy input, and easier glycerol recovery have driven research interest. However, the challenges remain as the high cost of enzyme catalysts, and inhibition of activity by alcohol or impurities [

77]. When enzymes are exposed to the media with high level of methanol concentration, the reaction times are longer, and incomplete conversions are common without process optimization [

78].

4.2. Thermochemical Conversion

Thermochemical pathways convert algal biomass into energy dense fuels via heat, pressure, and catalysts rather than targeting only extracted lipids. These processes handle wet or dry biomass and are generally faster than biochemical conversions. The main thermochemical routes for algal biofuels are pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL). In pyrolysis, dried algal biomass is rapidly heated to 300-600°C in the absence of oxygen which causes thermal decomposition of biopolymers into vapors, gases, and char [

79]. The condensable vapors are cooled to produce bio-oil while non-condensable gases such as CO, CO

2, H

2, and CH

4 and solid biochar are co-products. Fast pyrolysis maximizes bio-oil yield, which exceeds 28-65% of dry algal biomass depending on algal species under optimized conditions [

80]. Therefore, algae can yield bio-oil with energy content greater than 45 MJ/kg and is comparable to petroleum fuels. However, the bio-oils from algae are typically oxygen and nitrogen rich due to decomposition of carbohydrates and proteins that contain a complex mixture of hydrocarbons, phenolics, N-heterocyclic compounds, and other compounds [

79]. Especially algae derived bio-oil often contains significant fractions of pyrroles, indoles, and other nitrogenated compounds from protein that cause NO

x emissions if combusted directly [

81]. To improve the bio-oil quality, catalytic pyrolysis was implemented which utilize solid catalyst during pyrolysis to crack heavy molecules and promote deoxygenation and denitrogenation reactions. Catalysts increase the higher heating value of algal bio-oil, although catalytically upgraded bio-oil still has lower quality than refined fossil fuels and requires further hydrotreatment. The solid biochar from pyrolysis retains inorganic content and carbon which can be utilized as a fertilizer or soil amendment or as a solid fuel or catalyst support. Overall, pyrolysis offers rapid ways to convert algae into liquid fuel and widely used in co-pyrolysis of microalgae [

82].

In contrast, gasification involves partial oxidation of algal biomass at higher temperatures compared to pyrolysis to produce syngas which is a mixture of combustible gases mainly composed of H

2 and CO along with CO

2, CH

4 [

83]. In this process, a limited or no oxygen containing steam is introduced to react with the feedstock and convert nearly all the organic carbon into gas. Here, algae are gasified in the reactor with the high protein and ash content of algae influences the process [

84]. Syngas composition from algal gasification can be H

2 and CO rich where the reported dry syngas fractions were 52% H

2, 42% CO when gasifying

Chlorella vulgaris under optimized conditions with steam [

85]. The presence of steam tends to shift the product toward more H

2 at the expense of CO. In advance, the process involves supercritical water where the process operates beyond 374°C and 22.1MPa that corresponds to supercritical point of water. In this process, algal slurries in water are gasified without drying, resulting in high conversion of algae to H

2 and CH

4 rich gas with the advantage of capturing nutrients in the aqueous effluent, though it requires expensive high-pressure systems. Overall. Gasification is attractive for macroalgae and low-lipid algae as high carbohydrate content favors gas production [

86].

Lastly, HTL is a wet conversion process that directly converts high moisture algal biomass into a crude liquid oil under pressurized hot water conditions [

87]. Typically, a slurry of algal biomass is heated to 200-380°C at 5-28MPa in a reactor [

88]. In hydrothermal conditions, water acts as both a solvent and reactant which is depolymerizing biopolymers in algae into oils, producing the HTL biocrude. The primary product is a viscous biocrude oil that can further be upgraded to fuels along with a nutrient rich aqueous phase, gas, and solid residue. A major advantage of HTL is that is does not require drying of the feedstock which is beneficial on utilization of wet algae by reducing energy costs in drying procedure. HTL is suitable for both microalgae and macroalgae since all carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids are liquefied to some extent. Typically, biocrude yields range from 13wt.% up to 73wt.% of dry mass depending on the algae species, process, and conditions [

89]. Biocrude has an energy density around 30 MJ/kg and is generally more stable and lower in oxygen than bio-oils from fast pyrolysis as water at high pressure facilitates deoxygenation. However, algal HTL oil contains a significant fraction of nitrogen and some oxygen due to the algal composition. This means the HTL biocrude requires upgrading before it can be used as fuel [

90]. The most promising method is to use catalysts and co-solvents where alcohol such as methanol and ethanol or formic acid is added to HTL reactors to promote hydrolysis and decarboxylation which increases oil yields and reduce char formation. Additionally, heterogeneous catalysts such as zeolite can be introduced in the HTL step to initiate deoxygenation and denitrogenation where it significantly boosts biocrude yields. Thus, HTL has emerged as a promising pathway for an integrated algal biorefinery, especially for wet biomass. This combined approach can maximize liquid fuel yield from algae [

87].

4.3. Biochemical Conversion

Biochemical conversion pathways employ microbial processes to convert algal biomass into biofuels such as bioethanol, biobutanol, and biohydrogen. Compared to thermochemical routes, biochemical methods typically operate at lower temperatures and ambient pressures but often require more preprocessing and have slower reaction rates. For bioethanol fermentation process, algal carbohydrates are fermented by microbes to produce ethanol similar to conventional energy crops such as corn or sugarcane ethanol processes [

91]. Microalgae species can accumulate significant starch under nutrient deprivation, and this starch can be saccharified into glucose for fermentation [

92]. Macroalgae, particularly brown and green seaweeds, contain unique polysaccharides such as β-glucan, mannitol, ulvan, and alginate which have no lignin and can be more easily hydrolyzed than lignocellulosic biomass. However, engineered microbes are needed to ferment some of these sugars. A crucial step is pretreatment and hydrolysis where algae need to be pretreated with dilute acid or enzymes to break down lignin to further convert polysaccharides into fermentable monosaccharides [

93]. The optimization of pretreatment is essential to maximize sugar release while minimizing formation of inhibitors such as furfural and hydromethylfurfural (HMF) that could impair fermentation [

94,

95].

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is a biochemical process in which consortia of bacteria and archaea decompose organic matter in the absence of oxygen to produce biogas. AD can treat whole algal biomass or residual biomass and is considered a key step for integrating algal biofuel processes [

96]. Microalgae have been widely tested in anaerobic digesters where it can yield methane, but the yields are limited by algae’s cell wall recalcitrance [

97]. The high protein in many microalgae leads to ammonia release during AD, which at elevated concentrations can inhibit methanogenic archaea [

98]. Strategies such as pretreatment and co-digestion are employed to address these issues where co-digestion can improve stability, and methane yields by balancing the carbon/nitrogen ratio and diluting inhibitory compounds [

99]. For example, blending microalgae with wastewater sludge significantly increased gas yields and process stability as the algae supplies nitrogen and trace nutrients while the co-substrate supplies extra carbon [

98]( Typical methane yields from microalgae range from 24 to 800 mL per gram of volatile solids (VS), though yields on the higher end are achievable with pretreatment and appropriate loading rates. Macroalgae such as seaweed are easy to digest since macroalgae contains high carbohydrates and low lipid content which tends to produce similar yield of biogas with a range of 24 to 505 ml CH

4 per gram of VS [

96]. However, the presence of sulfate in marine algae can cause competition from sulfate reducing bacteria instead of methanogenesis [

100]. Importantly, AD is often integrated at the end of an algal biorefinery where after extracting lipids for biodiesel or fermenting sugars to ethanol, the leftover biomass can be anaerobically digested to capture remaining energy as biogas. This integrated approach not only improves total energy recovery but also produces a nutrient rich digestate that can be recycled as fertilizer for algae cultivation, closing the nutrient loop [

101].

Dark fermentation refers to the anaerobic conversion of organic substrates to biohydrogen by fermentative bacteria as opposed to photofermentation which requires light. Certain anaerobic bacteria such as species of clostridia and Enterobacter can degrade carbohydrates and produce hydrogen and CO

2 as part of their metabolism [

102]. Algal biomass, especially carbohydrate rich microalgae or macroalgal hydrolysates can be used as feedstock for hydrogen fermentation. The lack of lignin and hemicellulose in algae and the high carbohydrate content are advantageous which allows milder pretreatments and higher H

2 yields compared to conventional lignocellulosic biomass [

102,

103]. Nevertheless, effective pretreatment is still important to improve biodegradability where common methods such as dilute acid hydrolysis are implemented to break algal cells and release fermentable sugars. Dark fermentation of algae usually yields a mixture of H

2 and CO

2 in the gas and leaves a significant amount of energy in the form of residual organic acids or alcohols in the liquid effluent [

103]. Thus, an attractive configuration is a two-stage process where the first stage dark fermentation produces hydrogen, and the effluent is then fed to a methanogenic digester to produce methane from the remaining volatile acids. These coupled technologies can recover energy as H

2 and subsequently as CH

4, maximizing overall bioenergy extraction from algae [

102,

103].

5. Catalytic Strategies in Algal Biofuel Production

The various catalytic strategies and conversion pathways used to produce biofuels using algae is summarized in

Table 2.

5.1. Heterogeneous Catalysis

Heterogeneous catalysts have gained prominence in microalgal biofuel production due to their reusability, selectivity, and ease of separation from products [

111]. In transesterification of algal lipids to biodiesel, solid based catalysts such as calcium oxide (CaO), magnesium oxide (MgO), strontium oxide (SrO), supported alkali/alkaline earth metals, basic zeolites, and hydrotalcite clays have all been explored [

65]. These catalysts achieved high conversion of microalgal oils into fatty acid methyl esters while avoiding many drawbacks of homogenous bases. In the findings of 92.03 wt% biodiesel production yield was achieved using CaO catalyst under 70°C with agitation. Additionally, solid catalysts allow continuous processing such as fixed bed reactors and simply product separation [

106,

112]. Unlike liquid alkali, solid base catalysts do not cause soap formation with free fatty acids and can even be paired with solid acids to simultaneously esterify free acids, allowing high-FFA algal oils to be converted without pretreatment [

65]. Solid acid catalysts have also been used either alone or in dual catalyst systems to ensure both transesterification and esterification occur, which is especially beneficial for lower quality or high acidity algal feedstocks. Overall, heterogeneous transesterification offers superior catalyst recovery, lower energy and water usage, and the possibility of catalyst recycling, which is making the process more sustainable than traditional base-catalyzed methods [

65,

111].

Solid catalysts are equally important in thermochemical pathways such as pyrolysis, HTL, and biocrude upgrading. Catalytic pyrolysis of microalgae using acidic solids such as HZSM-5, zeolite, or modified alumina/titania has been shown to produce bio-oils with higher hydrocarbon and aromatic content and significantly lower oxygen content compared to non-catalytic pyrolysis [

113]. The catalyst promotes cracking of heavy biomolecules and deoxygenation reactions, thereby improving the fuel properties of the oil. Similarly, in hydrothermal liquefaction, addition of heterogeneous catalysts can increase biocrude yield and quality. For example, alumina, titania, or zeolite supports modified with transition metals have demonstrated over 86% biodiesel under supercritical condition of alcohol (2500 psi and 300-450°C) while allowing reuse of the catalyst for multiple cycles [

114]. After primary conversion, upgrading of algal biocrude to drop-in fuels usually employs solid hydrotreating catalysts to catalytically remove oxygen, nitrogen and sulfur heteroatoms via hydrogenation and deoxygenation (Santillan et al., 2019). In the findings of Bai et al. (2014), Ru/C+Raney nickel catalyst was highly active for denitrogenation/deoxygenation that successfully reduced 8.0 wt.% N and 2.1 wt.% O composition down to 2.0 wt.%. After the removal of oxygen and nitrogen content from biodiesel, the heating value reached 45 MJ/kg. In summary, heterogenous catalysis spans multiple processes in algal biofuel production from solid base catalysts in biodiesel synthesis to acid/cracking catalysts in pyrolysis and metal catalysts in hydrotreating that offers advantages of selectivity and recyclability [

115].

5.2. Homogeneous Catalysis

Homogeneous catalysts have historically been used in lipid to biodiesel conversion, but they come with significant limitation, especially for algal feedstocks. Common base catalysts like sodium or potassium hydroxide offer fast reaction kinetics and are effective with refined oils and are still employed in some industrial biodiesel processes [

116]. However, if microalgal oils contain more than a few percent free fatty acids or any moisture, alkaline catalysts induce saponification side reactions where fatty acids react to form soaps which hinder the separation and purification of biodiesel [

117]. Soap formation not only consumes catalysts and reduces biodiesel yield, but it produces emulsions that complicate product recovery. Strong acid catalysts such as H

2SO

4 or HCl do not form soaps and can esterify FFA to biodiesel, making them more tolerant of low-grade oils. Additionally, Chamola et al. (2019) demonstrated that acid transesterification using H

2SO

4 can achieve maximum biodiesel yield in relatively shorter reaction time compared to NaOH catalyst [

118]. Sulfuric acid transesterification took 60.443 min to achieve the maximum biodiesel yield while 73.637 min was consumed with NaOH. However, acids are highly corrosive to reactors and pipelines, raising material compatibility issues [

117]. In general, all homogeneous catalysts are single use after reaction, the catalyst ends up in the glycerol-rich phase or spent washing water and cannot be economically recovered [

111]. Additional neutralization and wastewater treatment are needed to remove these catalysts which are adding cost and environmental burden. For instance, alkaline transesterification of microalgal oil with NaOH might achieve high initial conversion, but if the algae oil has greater than 0.5% FFA or any water, the process demands feed pretreatment and generates substantial soap and waste salt. These drawbacks make homogeneous catalysis less attractive for algal biodiesel refining. Consequently, there is a shift toward solid acid/base catalysts or enzymatic catalysts in research, aiming to eliminate the costly separation steps while still obtaining high methyl ester yields [

117].

5.3. Emerging Trends

5.3.1. Photocatalysis

Photo catalytic strategies are being explored to leverage solar energy for algal biofuel conversion. In biodiesel production, semiconductor photocatalysts such as TiO

2 or ZnO based materials can be activated by UV or visible light to drive transesterification, which potentially reduces the external heat or energy required for the reaction [

119]. This solar-driven catalysis is an eco-friendly concept in which sunlight facilitates the conversion of algal lipids to fatty acid esters. Another promising avenue is photocatalytic reforming of algae derived intermediates into hydrogen or other fuels. For example, glycerol, which is the main co-product of transesterification, can be photoreformed in water under solar irradiation to produce H

2, using catalysts like doped TiO

2 as a photoactive surface [

120]. Recent studies demonstrate that titanium oxide nanotube photocatalysts under UV light can oxidize glycerol, yielding hydrogen gas as a renewable fuel. Such photocatalytic reforming not only generates clean hydrogen gas but also valorizes glycerol into a useful fuel [

121]. Overall, photocatalysis introduces renewable energy into the conversion process, offering a route to solar-driven algal biorefineries that produce both liquid and gaseous biofuels.

5.3.2. Electrocatalysis

Electrocatalytic processes use electrical energy to drive chemical conversions of algal biomass fraction with help of specialized electrodes and catalysts. A key emerging application is the electrochemical upgrading of bio-oils into higher quality fuels. In conventional upgrading like hydrodeoxygenation (HDO), high pressure hydrogen and temperatures of 300 to 400°C are required to remove oxygenates. By contrast, electrochemical hydrogenation (ECH) can be performed at mild conditions with lower than 80°C with ambient pressure by supplying electrons to reduce bio-oil oxygenates into hydrocarbons [

122]. This means acids, aldehydes, and other polar compounds in algal bio-oil can be electrochemically reduced to more stable alcohols or alkanes, thereby reducing the bio-oil’s acidity while increasing its stability and energy content [

123]. Crucially, ECH does not require external H

2 gas and can run on renewable electricity since hydrogen is generated in situ from water electrolysis [

122]. Preliminary assessments indicate that integrating electrocatalytic upgrading could cut greenhouse emissions by up to three times compared to standard thermal upgrading with fossil hydrogen. Beyond bio-oil refining, electrocatalysis is being tested for reforming biomass derived streams. For instance, electrolysis cells that oxidize glycerol or organic acids at the anode while producing hydrogen at the cathode [

124]. Such systems not only treat byproducts but also co-generate fuel. Although electrocatalytic approaches are mostly at the lab scale, they hold promises for cleaner and electricity-driven conversion of algal feedstocks into fuels and chemicals.

6. Integrated Algal Biorefineries

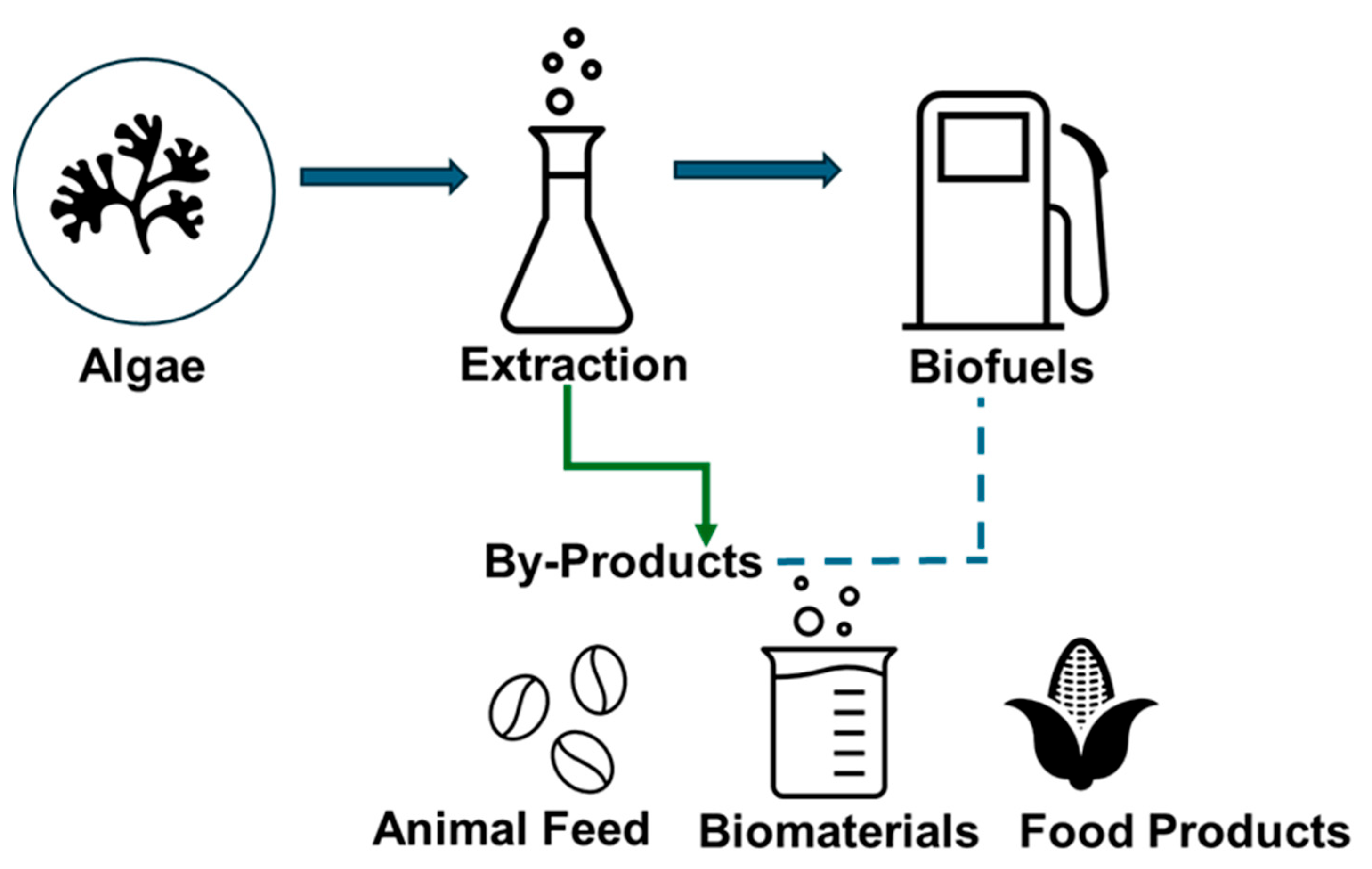

As shown in figure 3, integrated algal biorefineries (IABR) are primarily designed for the maximum utilization of micro- and macroalgae biomass to produce biofuels, valuable biproducts and bioenergy. IABR model is designed to exploit the algal biomass and convert it into valuable compounds like lipids, carbohydrates, proteins, and pigments. This technology favors the principles of net-zero waste production and strong economic benefits for the society [

125].

6.1. Concept and Design of Algal Biorefineries

Algal biorefineries are comprised of multiple unit operations such as cultivation, pretreatment, and conversion process. These processes are modular, scalable, and tailored for a particular algal species, environment, and economic perspective [

126]. In a typical upstream biorefinery, algae are cultivated in large photobioreactors under optimized conditions of nutrients, light, carbon dioxide, pH, and temperature. Afterwards, pretreatment stage consists of harvesting of algal biomass, dewatering, drying, hydrolysis, and extraction processes to obtain lipids and carbohydrates [

127]. Thereafter, conversion step involves pyrolysis, hydrothermal liquefaction, transesterification, fermentation, and anaerobic digestion to produce biofuels, biodiesel, bioalcohols and biogas [

128,

129]. In addition to this, carbon capture and wastewater treatment facilities integrated with the algal biorefinery favours the environment sustainability and reduced input cost. Thus, the output efficiency of IABs can be enhanced by process integration and maximum resource utilization [

130].

6.2. Valorization of Co-Products (Proteins, Pigments, Fertilizers)

Algal biomass is the main source of proteins, carbohydrates, and pigments that can be transformed into valuable co-products. Algal proteins are popular as nutraceuticals, aquaculture, and animal feed products due to their essential amino acid profile [

131]. Pigments derived from algae such as chlorophyll, phycobiliproteins, and carotenoids have major applications in food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals industries. The leftover residue of algal biorefinery can be useful as biofertilizers for the soil enrichment with macronutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Thus, the biproducts of algal biorefineries are essential for the techno-economic balancing and perfectly aligned with the circular bioeconomy model like lignocellulosic system [

132,

133].

6.3. Energy and Economic Optimization

The sustainability of algal biorefinery depends on the energy efficiency. The algal biomass contains high amount of water which consume energy in dewatering and drying process [

134]. Therefore, energy efficient harvesting technique such as electrocoagulation, flocculation, and membrane filtration were employed for these applications [

135]. Integrated approach in biorefinery like coupling lipid extraction with anaerobic digestion can reduce the energy input and enhance the net energy returns in overall process [

136]. Today, algal biorefinery and wastewater treatment plant are complemented to each other and capable to reduce the overall capital expenditure and can generate more revenue form the greater economic perspective. Techno-economic analysis evaluates the economic viability of these integrated workflow system and optimize the process for further scale-up [

137].

6.4. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Sustainability Metrics

Life cycle assessment (LCA) is a comprehensive approach and used to evaluate the environmental impact of algal biorefineries throughout its entire life cycle. Algae-based biofuel production has a significantly contribution towards carbon neutrality [

138]. The LCA model suggested that actual environment sustainability outcomes are based on the factors like cultivation, energy source, and geographical location [

139]. The LCA studies underlined important benefits such as reduced global warming potential and enhanced resource efficiency, whereas also found challenges like feedstock optimisation, technological integration, and economic feasibility. The GREET

® (Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions and Energy Use in Transportation) model was used to study the energy consumption, GHG emissions, and water requirements in production of renewable biodiesel from algae and palm oil feedstock [

140]. Additionally, sustainability of algal biorefineries were determined using metrics such as global warming potential (GWP), eutrophication potential, and energy return on investment (EROI) in various study design [

141].

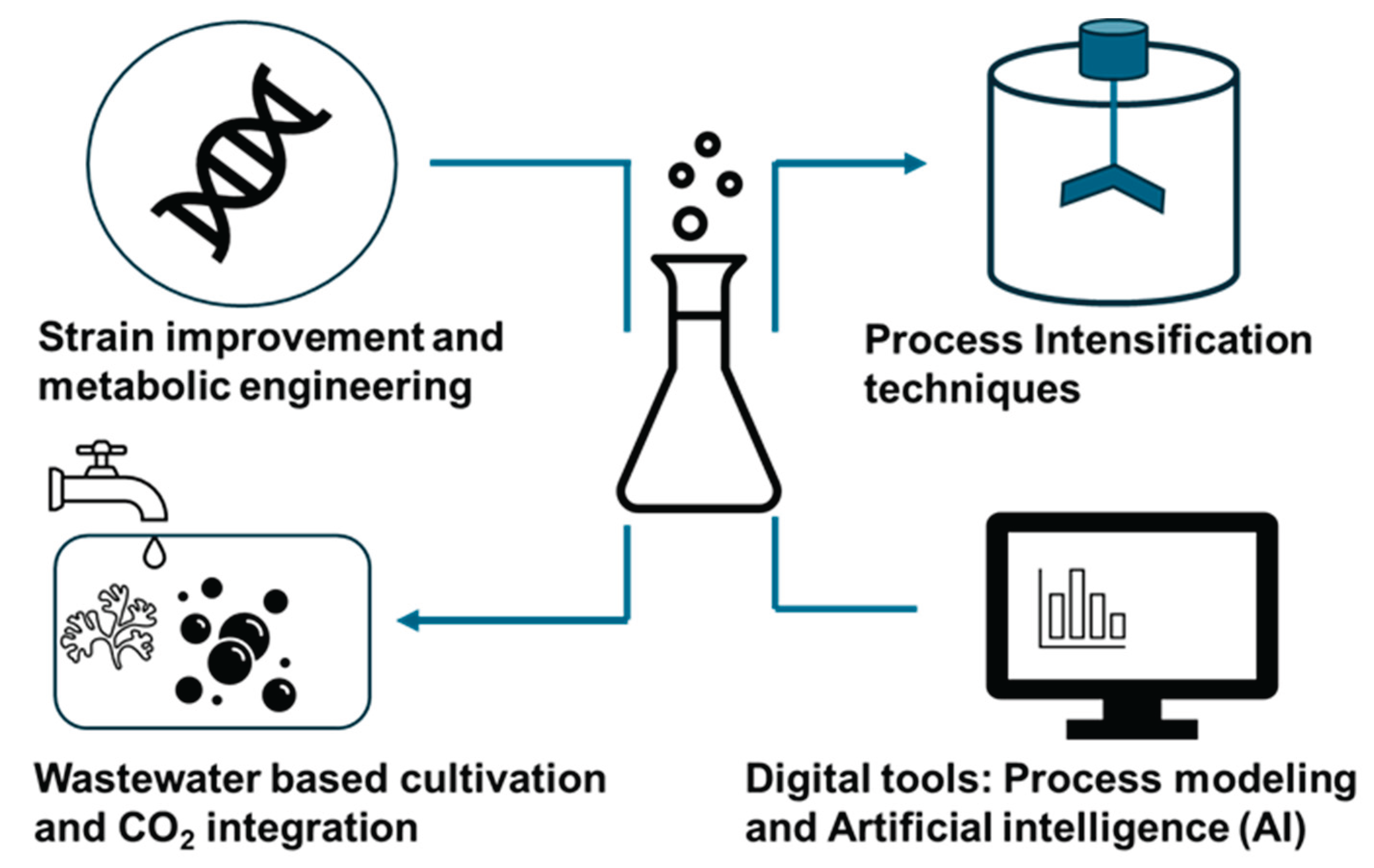

7. Recent Advances in Sustainable Technologies

Certainly, sustainability in an algal biorefinery system can be achieved by implementing improved catalytic processes, intensifying operations, and digital innovations (

Figure 4). A circular bioeconomy model should be implemented in algal biorefineries to enhance the production of biofuels and other valuable compounds. The current advancements in algal biorefineries can overcome the problems of low productivity, high input cost, and poor economic performance by implementing conceptual designs in industrially viable settings [

142].

7.1. Strain Improvement and Metabolic Engineering

In a biorefinery system, microbial productivity is an important factor that affect the production of biofuels from algal biomass. Mutagenesis, adaptive laboratory evolution, and metabolic engineering techniques were used to increase the lipid concentration, carbon fixation rates, and tolerance to stress conditions of algal species [

143]. Recently developed CRISPR/Cas9 and various other genome editing techniques have been used to enhance lipid biosynthesis, and pigment production in algal species such as

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Nannochloropsis sp., and

Phaeodactylum tricornutum [

144]. Synthetic biology approaches further enable the rational designing of algal strains to produce biofuels and valuable co-products [

145,

146].

7.2. Process Intensification Techniques

To enhance biofuel production, process intensification is necessary for upgrading algal biochemical process by integrating unit operations and reducing energy cost, material input, and carbon footprint [

147]. For example, photobioreactor, and hydrodynamic cavitation is a process intensification in algal biorefinery [

148,

149]. Similarly, coupling algal cultivation with lipid extraction and simultaneous hydrothermal treatment and gas upgrading techniques shorten the process chain and increase the output efficiency of a biorefinery system [

150]. Supercritical CO

2 and ionic liquids further enhance the process of lipid extraction from algae biomass with minimal environmental impact [

151,

152]6

7.3. Wastewater-Based Cultivation and CO₂ Integration

Coupling algal cultivation with wastewater and flue gas reduces overall operational costs and potentially offers benefits like waste remediation and CO

2 sequestration. Wastewater cultivation systems can provide rich nutrients (N, P, and trace elements) and promote the growth of microalgae with high lipid production. Similarly, flue gases were used as an inexpensive carbon source [

153]. For example, consortia of

Chlorella and

Scenedesmus cultivated on textile wastewater, significantly remove nitrogen (70%) and phosphorus (95%). These types of coupling eventually provide huge benefits for algal growth and lower the environmental impact [

154].

7.4. Digital Tools: Process Modeling and Artificial Intelligence

Digital tools such as mechanistic modeling, machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI) are transforming design, operation, and scale-up of algal biorefineries. Thus, accurate forecast of algal growth, optimal harvest times, nutrient changes, and bioreactor performance are possible at various environmental conditions [

155]. For example, artificial neural network (ANN) combined with genetic algorithm (GA) tools were used to optimize

Scenedesmus sp. culture production in a photobioreactor using domestic wastewater as a medium and flue gas as a carbon source [

156].

8. Policy, Regulation, and Market Outlook

Indeed, the production of algal biofuel and other byproducts is dependent on current technological advancements, the circular bioeconomy approach, and the use of genetically modified algae. A flexible policy framework, regulations, and a favorable open market is also necessary to support the biorefinery's current operations and future sustainability [

157,

158].

8.1. Global Policies Supporting Algal Biofuel Development

To promote algal biofuel R&D, several nations and reginal territories are building strong policies. For example, department of energy (DOE) of United States is promoting Bioenergy Technologies Office (BETO) and the Algae Program, their goal is to reduce the cost of biofuel production (e.g.,

$3/gallon by 2030) and establishing new pilot projects. In California, Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) and Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) further support algal biofuels by giving them Renewable Identification Numbers (RINs) and carbon intensity (CI) scores, respectively [

159,

160]. Similarly, European Union is building strong policy frameworks like Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) with a Mandat of increasing the share of advanced algal biofuel in transportation energy. The Horizon Europe has funded many projects related to algal biorefineries under the Bio-Based Industries Joint Undertaking (BBI JU) program [

161]. In India, the National Bio-Energy Mission and SATAT (Sustainable Alternative Towards Affordable Transportation) programs offers huge incentives for algal biofuel projects, and institutions like DBT-ICGEB has algal research centre. However, specific policies for the algal based biofuel production are still underdeveloped [

162,

163].

8.2. Subsidies, Incentives, and Carbon Credits

In USA, financial incentives were provided as tax exemption of 4 cent per gallon ethanol blended gasoline under Energy Tax Act (1978). The American Jobs Creation Act (2004), Energy Policy Act 2005 and 2010 have been introduced to provide tax benefits as Ethanol Excise Tax Credit (VEETC). Similarly, Farm bill (2007) offers tax incentives of 51–45 cents/gallon for the first-generation ethanol and 1.01

$/gallon tax incentives for lignocellulosic ethanol [

164]. Similar, Advanced Research Projects Agency–Energy (ARPA-E) program of Department of Energy (DOE) has invested more than

$1.5 billion and supported more that 500 projects related to boost the energy sector [

165]. Moreover, carbon pricing and trading mechanisms offers benefits for algal biorefineries to monetize their CO

2 uptake. Algal biorefineries are capable to sequester 1.8-2.2 kg of CO₂ per kg of biomass which adds carbon credit in voluntary and compliance markets [

166]. Algal cultivation has immense potential of carbon capture and utilization. Nevertheless, a transparent carbon accounting and MRV (Measurement, Reporting, Verification) system is required to achieve the carbon mitigation [

167].

8.3. Market Trends and Commercialization Prospects

The US government’s department of Energy’s Bioenergy Technologies Office (BETO) aims to produce 5 billion gallons of algal biofuel by 2030 [

168]. Despite growing R&D, commercial market of algal biofuels is limited. In the beginning, algal biofuel was produced by companies such as Sapphire Energy, Solazyme (now TerraVia), Algenol, and Heliae. However, these companies faced various challenges to produce algal biofuel within the economical scale. Recently, the direction of biorefineries shifted towards producing valuable by-products (e.g., omega-3 fatty acids, astaxanthin, biofertilizers) alongside biofuels to gain more returns on their investments [

169]. The bioplastics and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) markets are also gaining popularity with algal biorefineries. Algal-derived SAF has been used in airlines (Turkish Airlines) because of its low carbon emission. Thus, global market is shifting towards algal based solutions to reduce the carbon emissions and implementation of circular bioeconomy model [

170].

9. Challenges and Future Perspectives

The commercialization of algal biofuels and co-products are limited due to some technological, economic and infrastructure related challenges. However, synthetic biology and integrated algal biorefineries offers substantial economic benefits by overcoming these roadblocks.

9.1. Major Bottlenecks: Cost, Energy Input, and Scalability

The commercialization of algal biofuel is restricted by its high production cost due to energy intensive nature of cultivation, harvesting, and downstream processing. Algal research estimated that harvesting and dewatering activities consume 30% of the energy input due to low biomass productivity of algal culture [

136]. Inadequate supply of nutrients, nitrogen, phosphorus, and carbon dioxide further limit the cultivation of algae. The environmental stress conditions like pH, temperature, and light affect the performance of sensitive strain of algae. Furthermore, scalability of algal-based technology face challenges due to the requirement of adequate land, water and infrastructure development [

171,

172].

9.2. Future R&D Directions: Synthetic Biology and Hybrid Technologies

To overcome the major challenges, next-generation R&D strategies are now focusing on synthetic biology, metabolic engineering and genome editing techniques like CRISPR/Cas9 to enhance the algal growth, productivity and stress tolerance capability [

173]. Also, the engineered microalgae are capable to produce value-added products like astaxanthin, phycocyanin alongside fuels to support the economic foundation of a biorefinery [

174]. Similarly, integrated photobioreactors (PBRs) and open ponds can significantly reduce the cost and help in contamination check. Coupling algal system with municipal wastewater or industrial effluents offer bio-nutrients to promote bioremediation and ultimately reduces the carbon footprints. Moreover, algal cultivation attached with biofilm reactor system reduces the harvesting and water consumption cost [

175,

176]. Advanced computing technologies like Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are being employed to optimize the critical parameters such as nutrient supply, light intensity, and harvesting time to enhance the biomass productivity and lower the expenditure [

177].

9.3. Roadmap for Commercialization

The commercialization success of algal biofuels needs a critical roadmap that follow advanced technologies, supportive policies and investment by the stakeholders. For example, focusing on valorization of co-products alongside biofuels can reduce the production cost. Development of engineered strains with high productivity and promotion of pilot-scale operations that integrates CO₂ capture and wastewater treatment would benefit the environment [

178]. To create awareness about the circular bioeconomy, algal bioeconomy hubs need to be established in the rural areas. Algal biorefineries should be integrated with national energy and climate goals to obtain more benefits from carbon credit schemes and green infrastructure investments. At the end, academia-industry partnership, international research collaboration, and long-term government support will be very important to convert the research idea into commercially viable settings [

179,

180].

10. Concluding Remark

Algal biofuel stands as the next generation of renewable energy, offering a sustainable solution to the decarbonization of transportation and chemical sectors. Advanced catalytic strategies such as thermochemical and biochemical methods are vital to improve the proficiency and viability of algal biomass conversion. Moreover, sustainable algal cultivation combined with process intensification and an integrated biorefinery model, further strengthens the economic and environmental aspects. Despite significant progress, up-scale production and commercialization are still limited due to competitiveness and navigating regulatory frameworks. Life cycle assessments and techno-economic analyses further guide the technical feasibility, environment and social responsibilities. Interdisciplinary collaborations, public-private partnerships, and supportive government policies are essential to promote algal biofuel as a valuable source of energy. Finally, innovations and strategic investment in algal biorefinery follow the resilient and circular bioeconomy model that offers the dual advantages of energy production and environmental protection.

Author Contributions

SKR: conceptualization, writing original draft, GK: conceptualization, writing original draft, HS: conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, project administration, review and editing.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Kara Technologies Inc., Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) through the Alliance Grant program (ALLRP/560812-2020 and ALLRP/565222-2021) and Discovery Grant (RGPIN/05322-2019), and Alberta Innovates (G2020000355).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yoro, K. O.; Daramola, M. O. CO2 Emission Sources, Greenhouse Gases, and the Global Warming Effect. In Advances in Carbon Capture; Elsevier, 2020; pp 3–28. [CrossRef]

- Sharmila, V. G.; Rajesh Banu, J.; Dinesh Kumar, M.; Adish Kumar, S.; Kumar, G. Algal Biorefinery towards Decarbonization: Economic and Environmental Consideration. Bioresource Technology 2022, 364, 128103. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Hussain, N.; Shahbaz, A.; Mulla, S. I.; Iqbal, H. M. N.; Bilal, M. Sustainable Production of Biofuels from the Algae-Derived Biomass. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2023, 46 (8), 1077–1097. [CrossRef]

- Jabłońska-Trypuć, A.; Wołejko, E.; Ernazarovna, M. D.; Głowacka, A.; Sokołowska, G.; Wydro, U. Using Algae for Biofuel Production: A Review. Energies 2023, 16 (4), 1758. [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Kang, K.; Salaudeen, S.; Ahmadi, A.; He, Q. S.; Hu, Y. Recent Advances in Algae-Derived Biofuels and Bioactive Compounds. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61 (3), 1232–1249. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; Vinu, R. Reaction Engineering and Kinetics of Algae Conversion to Biofuels and Chemicals via Pyrolysis and Hydrothermal Liquefaction. React. Chem. Eng. 2020, 5 (8), 1320–1373. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Wajahat Ul Hasnain, S.; Salam Farooqi, A.; Singh, O.; Hidayah Ayuni, N.; Victor Ayodele, B.; Abdullah, B. Response Surface Optimization of Hydrogen-Rich Syngas Production by the Catalytic Valorization of Greenhouse Gases (CH4 and CO2) over Sr-Promoted Ni/SBA-15 Catalyst. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2023, 20, 100451. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, R. Y.; Manikandan, S.; Subbaiya, R.; Kim, W.; Karmegam, N.; Govarthanan, M. Advanced Thermochemical Conversion of Algal Biomass to Liquid and Gaseous Biofuels: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Advances. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2022, 52, 102211. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.; Kunj, P.; Kaur, A.; Khatri, M.; Singh, G.; Arya, S. K. Catalytic Strategies for Algal-Based Carbon Capture and Renewable Energy: A Review on a Sustainable Approach. Energy Conversion and Management 2024, 310, 118467. [CrossRef]

- Malode, S. J.; Prabhu, K. K.; Mascarenhas, R. J.; Shetti, N. P.; Aminabhavi, T. M. Recent Advances and Viability in Biofuel Production. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2021, 10, 100070. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P. H.; Quinn, J. C. Microalgae to Biofuels through Hydrothermal Liquefaction: Open-Source Techno-Economic Analysis and Life Cycle Assessment. Applied Energy 2021, 289, 116613. [CrossRef]

- Do Canto Salles, B.; De Souza, D. Interdisciplinary Approach to Microalgae Production in Partnerships Around the World. In Partnerships for the Goals; Leal Filho, W., Marisa Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp 610–623. [CrossRef]

- Passos, F.; Hernández-Mariné, M.; García, J.; Ferrer, I. Long-Term Anaerobic Digestion of Microalgae Grown in HRAP for Wastewater Treatment. Effect of Microwave Pretreatment. Water Res 2014, 49, 351–359. [CrossRef]

- Amalapridman, V.; Ofori, P. A.; Abbey, Lord. Valorization of Algal Biomass to Biofuel: A Review. Biomass 2025, 5 (2), 26. [CrossRef]

- Baweja, P.; Sahoo, D. Classification of Algae. In The Algae World; Sahoo, D., Seckbach, J., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2015; Vol. 26, pp 31–55. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L. Macroalgae. Encyclopedia 2021, 1 (1), 177–188. [CrossRef]

- Van Wychen, S.; Rowland, S. M.; Lesco, K. C.; Shanta, P. V.; Dong, T.; Laurens, L. M. L. Advanced Mass Balance Characterization and Fractionation of Algal Biomass Composition. J Appl Phycol 2021, 33 (5), 2695–2708. [CrossRef]

- Laurens, L. M. L.; Van Wychen, S.; McAllister, J. P.; Arrowsmith, S.; Dempster, T. A.; McGowen, J.; Pienkos, P. T. Strain, Biochemistry, and Cultivation-Dependent Measurement Variability of Algal Biomass Composition. Analytical Biochemistry 2014, 452, 86–95. [CrossRef]

- Siddiki, Sk. Y. A.; Mofijur, M.; Kumar, P. S.; Ahmed, S. F.; Inayat, A.; Kusumo, F.; Badruddin, I. A.; Khan, T. M. Y.; Nghiem, L. D.; Ong, H. C.; Mahlia, T. M. I. Microalgae Biomass as a Sustainable Source for Biofuel, Biochemical and Biobased Value-Added Products: An Integrated Biorefinery Concept. Fuel 2022, 307, 121782. [CrossRef]

- Da Rosa, M. D. H.; Alves, C. J.; Dos Santos, F. N.; De Souza, A. O.; Zavareze, E. D. R.; Pinto, E.; Noseda, M. D.; Ramos, D.; De Pereira, C. M. P. Macroalgae and Microalgae Biomass as Feedstock for Products Applied to Bioenergy and Food Industry: A Brief Review. Energies 2023, 16 (4), 1820. [CrossRef]

- Pancha, I.; Chokshi, K.; George, B.; Ghosh, T.; Paliwal, C.; Maurya, R.; Mishra, S. Nitrogen Stress Triggered Biochemical and Morphological Changes in the Microalgae Scenedesmus Sp. CCNM 1077. Bioresource Technology 2014, 156, 146–154. [CrossRef]

- Schulze, C.; Wetzel, M.; Reinhardt, J.; Schmidt, M.; Felten, L.; Mundt, S. Screening of Microalgae for Primary Metabolites Including β-Glucans and the Influence of Nitrate Starvation and Irradiance on β-Glucan Production. J Appl Phycol 2016, 28 (5), 2719–2725. [CrossRef]

- Biris-Dorhoi, E.-S.; Michiu, D.; Pop, C. R.; Rotar, A. M.; Tofana, M.; Pop, O. L.; Socaci, S. A.; Farcas, A. C. Macroalgae—A Sustainable Source of Chemical Compounds with Biological Activities. Nutrients 2020, 12 (10), 3085. [CrossRef]

- Trinh, T. N.; Jensen, P. A.; Dam-Johansen, K.; Knudsen, N. O.; Sørensen, H. R.; Hvilsted, S. Comparison of Lignin, Macroalgae, Wood, and Straw Fast Pyrolysis. Energy Fuels 2013, 27 (3), 1399–1409. [CrossRef]

- Langholtz, M. H.; Coleman, A. M.; Eaton, L. M.; Wigmosta, M. S.; Hellwinckel, C. M.; Brandt, C. C. Potential Land Competition between Open-Pond Microalgae Production and Terrestrial Dedicated Feedstock Supply Systems in the U.S. Renewable Energy 2016, 93, 201–214. [CrossRef]

- Babu, S. S.; Gondi, R.; Vincent, G. S.; JohnSamuel, G. C.; Jeyakumar, R. B. Microalgae Biomass and Lipids as Feedstock for Biofuels: Sustainable Biotechnology Strategies. Sustainability 2022, 14 (22), 15070. [CrossRef]

- Posadas, E.; Alcántara, C.; García-Encina, P. A.; Gouveia, L.; Guieysse, B.; Norvill, Z.; Acién, F. G.; Markou, G.; Congestri, R.; Koreiviene, J.; Muñoz, R. Microalgae Cultivation in Wastewater. In Microalgae-Based Biofuels and Bioproducts; Elsevier, 2017; pp 67–91. [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.; Ho, S.; Chen, C.; Chang, J. CO2 , NOx and SOx Removal from Flue Gas via Microalgae Cultivation: A Critical Review. Biotechnology Journal 2015, 10 (6), 829–839. [CrossRef]

- Lage, S.; Gojkovic, Z.; Funk, C.; Gentili, F. Algal Biomass from Wastewater and Flue Gases as a Source of Bioenergy. Energies 2018, 11 (3), 664. [CrossRef]

- Anand, A.; Tripathi, K.; Kumar, A.; Gupta, S.; Raghuvanshi, S.; Verma, S. K. Bio-Mitigation of Carbon Dioxide Using Desmodesmus Sp. in the Custom-Designed Pilot-Scale Loop Photobioreactor. Sustainability 2021, 13 (17), 9882. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L. N.; Vu, M. T.; Vu, H. P.; Johir, Md. A. H.; Labeeuw, L.; Ralph, P. J.; Mahlia, T. M. I.; Pandey, A.; Sirohi, R.; Nghiem, L. D. Microalgae-Based Carbon Capture and Utilization: A Critical Review on Current System Developments and Biomass Utilization. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2023, 53 (2), 216–238. [CrossRef]

- Borowitzka, M. A.; Moheimani, N. R. Open Pond Culture Systems. In Algae for Biofuels and Energy; Borowitzka, M. A., Moheimani, N. R., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013; pp 133–152. [CrossRef]

- Novoveská, L.; Nielsen, S. L.; Eroldoğan, O. T.; Haznedaroglu, B. Z.; Rinkevich, B.; Fazi, S.; Robbens, J.; Vasquez, M.; Einarsson, H. Overview and Challenges of Large-Scale Cultivation of Photosynthetic Microalgae and Cyanobacteria. Marine Drugs 2023, 21 (8), 445. [CrossRef]

- Geremia, E.; Ripa, M.; Catone, C. M.; Ulgiati, S. A Review about Microalgae Wastewater Treatment for Bioremediation and Biomass Production—A New Challenge for Europe. Environments 2021, 8 (12), 136. [CrossRef]

- Penloglou, G.; Pavlou, A.; Kiparissides, C. Recent Advancements in Photo-Bioreactors for Microalgae Cultivation: A Brief Overview. Processes 2024, 12 (6), 1104. [CrossRef]

- González-Camejo, J.; Viruela, A.; Ruano, M. V.; Barat, R.; Seco, A.; Ferrer, J. Effect of Light Intensity, Light Duration and Photoperiods in the Performance of an Outdoor Photobioreactor for Urban Wastewater Treatment. Algal Research 2019, 40, 101511. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, D. L.; Park, J.; Ralph, P. J.; Craggs, R. J. Improved Microalgal Productivity and Nutrient Removal through Operating Wastewater High Rate Algal Ponds in Series. Algal Research 2020, 47, 101850. [CrossRef]