Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

3. Materials and Methods

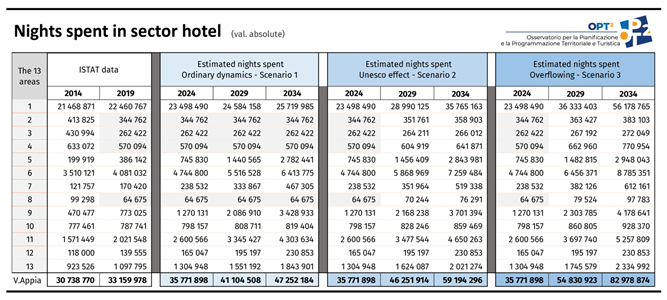

3.1. Area of Study and Territory Calibration

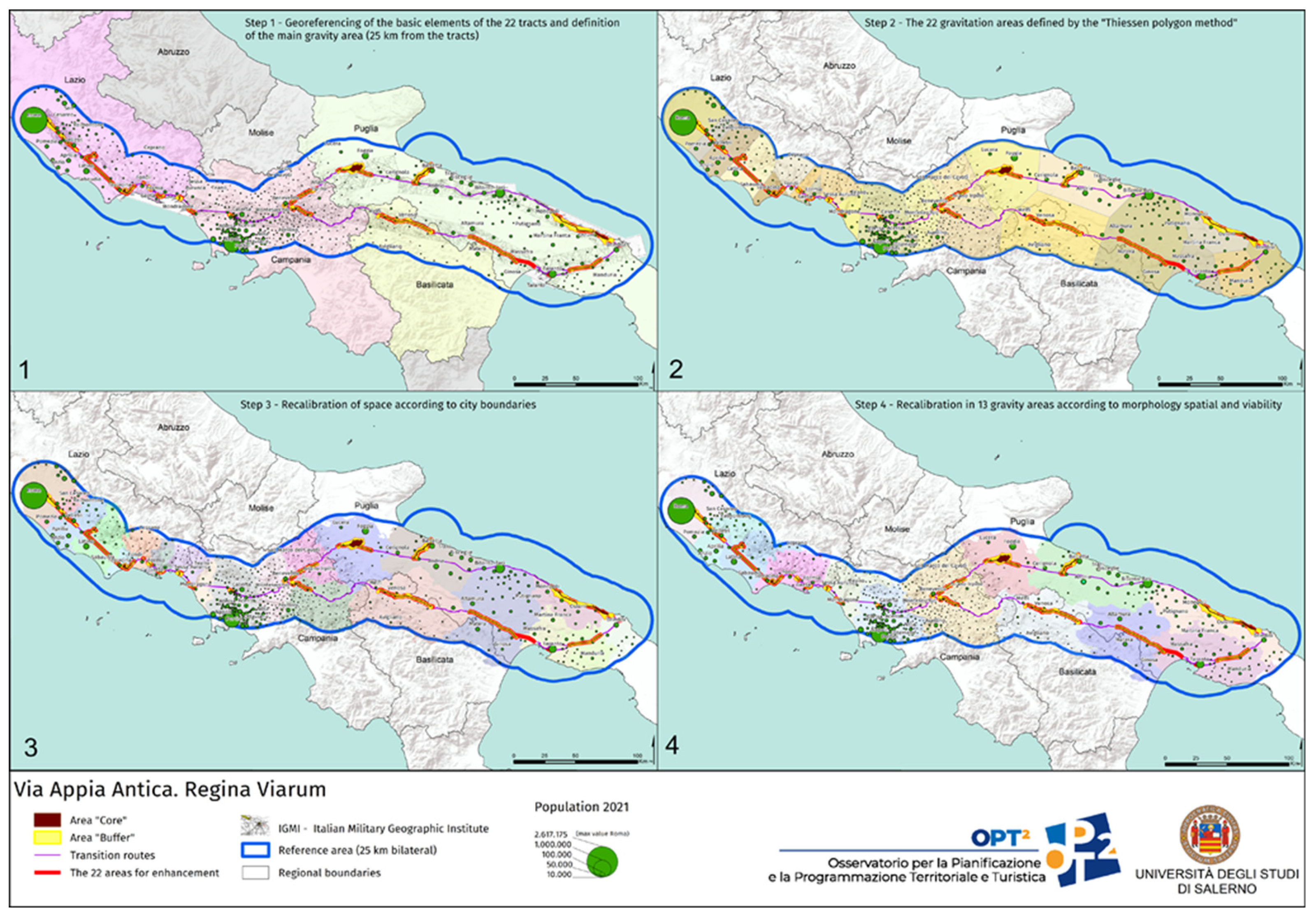

3.2. TCC Estimation Model

3.2.1. Physical Carrying Capacity (PCC)

- PCC <20% Very low impact;

- 21% ≤ PCC <40% Low impact;

- 41% ≤ PCC <60% Moderate impact;

- 61% ≤ PCC <80% High impact;

- 81%≤ PCC<100 Very high impact;

- PCC ≥100 Congestion and overuse.

3.2.2. Real Carrying Capacity (RCC)

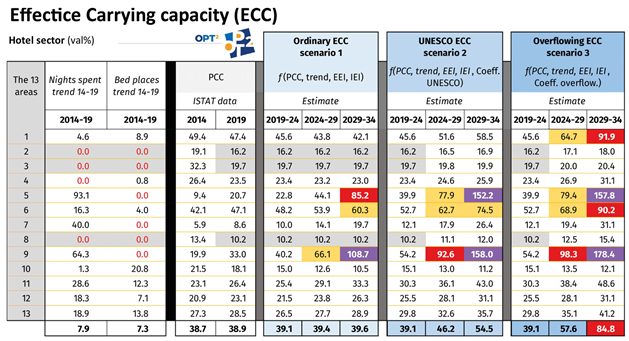

3.2.3. Effective Carrying Capacity (ECC)

3.2.4. The Correction System Based on EEI and IEI: Indicators, Weighting, and Spatial Representation

3.3. Dynamic Estimation of Tourism Carrying Capacity

- ECC <20% Very low impact;

- 21% ≤ ECC <40% Low impact;

- 41% ≤ ECC <60% Moderate impact;

- 61% ≤ ECC <80% High impact;

- 81%≤ ECC<100 Very high impact;

- ECC ≥100 Congestion and overuse

3.3.1. Scenario 1 - Ordinary Dynamics

3.3.2. Scenario 2 - UNESCO Effect

3.3.3. Scenario 3 - Overflowing/Stress Test

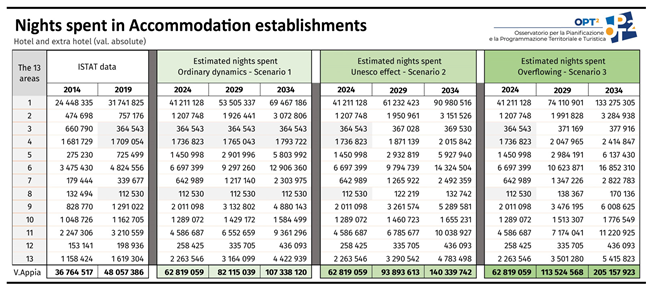

4. Results

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BP | Bed Places |

| Cf | Correction factors (generic, including Ecf and Icf) |

| Coverflowing | Overflowing Coefficient |

| CUNESCO | UNESCO Coefficient |

| DPa | Bed places Available |

| ECC | Effective (o Admissible) Carrying Capacity (synonymous of TCC) |

| Ecf | Ecological correction factors |

| EEI | Ecological Endowment composite index |

| eNS | Estimated Nights Spent |

| EUAP2010 | Elenco Ufficiale delle Aree Protette |

| GOr | Gross Occupancy rate |

| Icf | Infrastructure correction factors |

| IEI | Infrastructure Endowment composite index |

| ISPRA | Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale |

| ISTAT | Istituto Nazionale di Statistica |

| LPT | Local Public Transport |

| MiC | Ministero della Cultura |

| MSW | Municipal Solid Waste |

| NS | Nights Spent |

| PCC | Physical Carrying Capacity |

| RCC | Real Carrying Capacity |

| RFI | Rete Ferroviaria Italiana |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome COronaVirus 2 |

| TCC | Tourism Carrying Capacity |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

Appendix B

References

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Cheer, J.M. Overtourism and Tourismphobia: A Journey Through Four Decades of Tourism Development, Planning and Local Concerns. Tourism Planning & Development 2019, 16, 353–357. [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. From Carrying Capacity to Overtourism: A Perspective Article. Tourism Review 2020, 75, 212–215.

- Rogerson, C.M.; Baum, T. COVID-19 and African Tourism Research Agendas. Development Southern Africa 2020, 37, 727–741. [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W.; Dodds, R. Overcoming Overtourism: A Review of Failure. Tourism Review 2022, 77, 35–53.

- Page, S.J.; Duignan, M. Progress in Tourism Management: Is Urban Tourism a Paradoxical Research Domain? Progress since 2011 and Prospects for the Future. Tourism Management 2023, 98, 104737.

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Russo, A.P. Anti-Tourism Activism and the Inconvenient Truths about Mass Tourism, Touristification and Overtourism. Tourism Geographies 2024, 26, 1313–1337. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Page, S.J. The Geography of Tourism and Recreation: Environment, Place and Space; Fourth edition.; Routledge: New York, 2014; ISBN 978-0-415-83398-1.

- Saarinen, J.; Rogerson, C.M.; Hall, C.M. Geographies of Tourism Development and Planning. Tourism Geographies 2017, 19, 307–317.

- Shoval, N. Urban Planning and Tourism in European Cities. Tourism Geographies 2018, 20, 371–376. [CrossRef]

- Costa, C. Tourism Planning: A Perspective Paper. Tourism review 2020, 75, 198–202.

- Bramwell, B.; Lane, B. Critical Research on the Governance of Tourism and Sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2011, 19, 411–421. [CrossRef]

- Dredge, D.; Jamal, T. Progress in Tourism Planning and Policy: A Post-Structural Perspective on Knowledge Production. Tourism Management 2015, 51, 285–297.

- Blázquez-Salom, M.; Blanco-Romero, A.; Vera-Rebollo, F.; Ivars-Baidal, J. Territorial Tourism Planning in Spain: From Boosterism to Tourism Degrowth? In Tourism and Degrowth; Routledge, 2020; pp. 20–41.

- Bencardino, M.; Esposito, V. Il Turismo Costiero e Marittimo Meridionale: Una Analisi Di Base per Le Nuove Politiche Turistiche. Annali del turismo 2023, 93–108.

- Klepej, D.; Marot, N. Considering Urban Tourism in Strategic Spatial Planning. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2024, 5, 100136. [CrossRef]

- Coccossis, H.; Mexa, A. Tourism Carrying Capacity: Methodological Considerations. In The Challenge of Tourism Carrying Capacity Assessment; Routledge, 2017; pp. 71–106.

- Li, J.; Weng, G.; Pan, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, N. A Scientometric Review of Tourism Carrying Capacity Research: Cooperation, Hotspots, and Prospect. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 325, 129278.

- Ajuhari, Z.; Aziz, A.; Yaakob, S.S.N.; Abu Bakar, S.; Mariapan, M. Systematic Literature Review on Methods of Assessing Carrying Capacity in Recreation and Tourism Destinations. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3474.

- Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Gong, Z.; Cao, K. Dynamic Assessment of Tourism Carrying Capacity and Its Impacts on Tourism Economic Growth in Urban Tourism Destinations in China. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2020, 15, 100383.

- Navarro Jurado, E.; Tejada Tejada, M.; Almeida García, F.; Cabello González, J.; Cortés Macías, R.; Delgado Peña, J.; Fernández Gutiérrez, F.; Gutiérrez Fernández, G.; Luque Gallego, M.; Málvarez García, G. Carrying Capacity Assessment for Tourist Destinations. Methodology for the Creation of Synthetic Indicators Applied in a Coastal Area. 2012.

- Lima, A.; Nunes, J.C.; Brilha, J. Monitoring of the Visitors Impact at “Ponta Da Ferraria e Pico Das Camarinhas” Geosite (São Miguel Island, Azores UNESCO Global Geopark, Portugal). Geoheritage 2017, 9, 495–503. [CrossRef]

- Salerno, F.; Viviano, G.; Manfredi, E.C.; Caroli, P.; Thakuri, S.; Tartari, G. Multiple Carrying Capacities from a Management-Oriented Perspective to Operationalize Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas. Journal of environmental management 2013, 128, 116–125.

- Putri, I.A.S.L.P.; Ansari, F. Managing Nature-Based Tourism in Protected Karst Area Based on Tourism Carrying Capacity Analysis. Journal of Landscape Ecology 2021, 14, 46–64. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Villarán, A.; Espinosa, N.; Abad, M.; Goytia, A. Model for Measuring Carrying Capacity in Inhabited Tourism Destinations. Port Econ J 2020, 19, 213–241. [CrossRef]

- Zekan, B.; Weismayer, C.; Gunter, U.; Schuh, B.; Sedlacek, S. Regional Sustainability and Tourism Carrying Capacities. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 339, 130624.

- ESPON, E. Carrying Capacity Methodology for Tourism. Final Report, ESPON 2020, 66.

- Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations A Guidebook (English Version); World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), Ed.; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), 2004; ISBN 978-92-844-0726-2.

- Kristjánsdóttir, K.R.; Ólafsdóttir, R.; Ragnarsdóttir, K.V. Reviewing Integrated Sustainability Indicators for Tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2018, 26, 583–599. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Torres-Delgado, A. Measuring Sustainable Tourism: A State of the Art Review of Sustainable Tourism Indicators. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2023, 31, 1483–1496. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, V.; Maselli, G.; Nesticò, A.; Bencardino, M. Spatial Analysis of Tourism Pressure on Coastal and Marine Ecosystem Services. In Proceedings of the Networks, Markets & People; Calabrò, F., Madureira, L., Morabito, F.C., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; pp. 512–522.

- Mandić, A.; Marković Vukadin, I. Managing Overtourism in Nature-Based Destinations. In Mediterranean Protected Areas in the Era of Overtourism; Mandić, A., Petrić, L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 45–70 ISBN 978-3-030-69192-9.

- Peihong, W.; Kai, W.; Kerun, L.; Shufang, F. An Evaluation Model for the Recreational Carrying Capacity of Urban Aerial Trails. Tourism Management Perspectives 2023, 48, 101152. [CrossRef]

- UNESCO The Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- UNWTO Saturation of Tourist Destinations: Report of the Secretary General 1981.

- Mexa, A.; Coccossis, H. Tourism Carrying Capacity: A Theoretical Overview. The challenge of tourism carrying capacity assessment 2017, 53–70.

- Zacarias, D.A.; Williams, A.T.; Newton, A. Recreation Carrying Capacity Estimations to Support Beach Management at Praia de Faro, Portugal. Applied Geography 2011, 31, 1075–1081.

- Swarbrooke, J. Sustainable Tourism Management. CABI. The Three Dimensions of Sustainable Tourism 1999, 47–69.

- Costa, P.; Van Der Borg, J. Un Modello Lineare per La Programmazione Del Turismo. COSES informazioni 1988, 32, 21–26.

- Mathieson, A.; Wall, G. Tourism, Economic, Physical and Social Impacts.; 1982;

- Saveriades, A. Establishing the Social Tourism Carrying Capacity for the Tourist Resorts of the East Coast of the Republic of Cyprus. Tourism management 2000, 21, 147–156.

- Chen, C.-L.; Teng, N. Management Priorities and Carrying Capacity at a High-Use Beach from Tourists’ Perspectives: A Way towards Sustainable Beach Tourism. Marine Policy 2016, 74, 213–219.

- Brown, K.; Turner, R.K.; Hameed, H.; Bateman, I.A.N. Environmental Carrying Capacity and Tourism Development in the Maldives and Nepal. Environmental Conservation 1997, 24, 316–325.

- Wagar, J.A. The Carrying Capacity of Wild Lands for Recreation. Forest Science 1964, 10, a0001-24.

- Lime, D.W. Research for Determining Use Capacities of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. Naturalist 1970, 21, 9–13.

- Getz, D. Capacity to Absorb Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 1983, 10, 239–263. [CrossRef]

- Interministerial Council for Tourism. (2017). Dossier de Presse – Interministerial Council for Tourism. Matignon Press Office.

- O’Reilly, A.M. Tourism Carrying Capacity: Concept and Issues. Tourism management 1986, 7, 254–258.

- Cifuentes, M. Determinación de Capacidad de Carga Turística Enáreas Protegidas; Bib. Orton IICA/CATIE, 1992;

- Morales, M.E.; Aguilar, N.; Cancino, D.; Ramirez, C.; Ribeiro, N.; Sandoval, E.; Turcios, M. Capacidad de Carga Turistica de Las Areas de Uso Publico Del Monumento Nacional de Guayabo, Costa Rica. 1999.

- Amador, E.; Cayot, L.; Cifuentes, M.; Cruz, E.; Cruz, F.; Ayora, P. Determinación de La Capacidad de Carga Turística En Los Sitios de Visita Del Parque Nacional Galápagos. Servicio Parque Nacional Galápagos, Ecuador. 42p 1996.

- Maldonado, E.; Montagnini, F. Determinación de La Capacidad de Carga Turística Del Parque Nacional La Tigra Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Revista Forestal Centroamericana Volumen 10, número 34 (abril-junio 2001), páginas 47-51 2001.

- ORTIZ, C.D.R.C.; MORA, Z.J. Guía Metodológica Para El Monitoreo Impactos Del Ecoturismo y Determinar Capacidad de Carga Aceptable En La Unidad de Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia.

- Rocha, C.H.B.; Fontoura, L.M.; Vale, W.B.D.; Castro, L.F.D.P.; Da Silva, A.L.F.; Prado, T.D.O.; Da Silveira, F.J. Carrying Capacity and Impact Indicators: Analysis and Suggestions for Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas – Brazil. World Leisure Journal 2021, 63, 73–97. [CrossRef]

- Erdoğan, A. Revisiting Cifuentes’s Model for Cultural Heritage Tourism in the Era of Pandemics: The Site of Mardin Cultural Landscape Area. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism 2025, 26, 80–110. [CrossRef]

- Vanhove, N. Mass Tourism: Benefits and Costs. Tourism, development and growth: The challenge of sustainability 1997, 50–77.

- Tosun, C.; Jenkins, C.L. The Evolution of Tourism Planning in Third-World Countries: A Critique. Progr. Tourism Hospit. Res. 1998, 4, 101–114. [CrossRef]

- Arnegger, J.; Woltering, M.; Job, H. Toward a Product-Based Typology for Nature-Based Tourism: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2010, 18, 915–928. [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, Tourism and Global Change: A Rapid Assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2021, 29, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, D.G. Tourist Development; Longman Scientific & Technical, 1989; ISBN 978-0-582-01435-0.

- Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. L., Randers, J., & Behrens, W. W. (2018). The Limits to Growth. In Green Planet Blues (Pp. 25-29). Routledge.

- Doxey, G.V. A Causation Theory of Visitor-Resident Irritants: Methodology and Research Inferences. In Proceedings of the Travel and tourism research associations sixth annual conference proceedings; San Diego, 1975; Vol. 3, pp. 195–198.

- Boissevain, J. Tourism and Development in Malta. Development and Change 1977, 8, 523–538. [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.A. Impact of Domestic Tourism on Host Population: The Evolution of a Model. Tourism Recreation Research 1979, 4, 15–21. [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. 1. The Concept of a Tourist Area Cycle of Evolution: Implications for Management of Resources. In The Tourism Area Life Cycle, Vol. 1; Butler, R., Ed.; Multilingual Matters, 2006; pp. 3–12 ISBN 978-1-84541-027-8.

- Stamatiou, K. Bridging the Gap between Tourism Development and Urban Planning: Evidence from Greece. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6359.

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism: A Community Approach 1985.

- Getz, D. Tourism Planning and Research: Traditions, Models and Futures. In Proceedings of the Australian Travel Research Workshop, Bunbury, Western Australia; 1987; Vol. 5.

- Gunn, C.A. Tourism Planning.; 1988;

- Inskeep, E. Tourism Planning: An Integrated and Sustainable Development Approach; John Wiley & Sons, 1991;

- Saarinen, J. Traditions of Sustainability in Tourism Studies. Annals of tourism research 2006, 33, 1121–1140.

- Sumner, E.L. Special Report on a Wildlife Study of the High Sierra in Sequoia and Yosemite National Parks and Adjacent Territory; US Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1936;

- Manning, R.E. How Much Is Too Much? Carrying Capacity of National Parks and Protected Areas. In Proceedings of the Monitoring and management of visitor flows in recreational and protected areas. Proceedings of the Conference held at Bodenkultur University Vienna, Austria; 2002; pp. 306–313.

- Lucas, R.C. The Recreational Capacity of the Quetico-Superior Area; Lake States Forest Experiment Station, Forest Service, US Department of …, 1964; Vol. 15;.

- Lucas, R.C. Wilderness Perception and Use: The Example of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. Natural Resources Journal 1964, 3, 394–411.

- McMurry, K.C. THE USE OF LAND FOR RECREATION. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 1930, 20, 7–20. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R.I. WASAGA BEACH: THE DIVORCE FROM THE GEOGRAPHIC ENVIRONMENT. Canadian Geographies / Géographies canadiennes 1952, 1, 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is Overtourism Overused? Understanding the Impact of Tourism in a City Context. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4384.

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. The Phenomena of Overtourism: A Review. International Journal of Tourism Cities 2019, 5, 519–528.

- Chen, L.I.; Sheng-kui, C.; Yuan-sheng, C. A Review of the Study of China’s Tourism Carrying Capacity in the Past Two Decades. Geographical Research 2009, 28, 235–245.

- Stankey, G.H.; Cole, D.N.; Lucas, R.C.; Petersen, M.E.; Frissell, S.S. The Limits of Acceptable Change (LAC) System for Wilderness Planning. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-GTR-176. Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 37 p. 1985, 176.

- Graefe, A.; Kuss, F.R.; Vaske, J.J. Visitor Impact Management: The Planning Framework. (No Title) 1990.

- Manning, R.E.; Lime, D.W.; Hof, M.; Freimund, W.A. The Visitor Experience and Resource Protection (VERP) Process: The Application of Carrying Capacity to Arches National Park. In Proceedings of the The George Wright Forum; JSTOR, 1995; Vol. 12, pp. 41–55.

- McCool, S.F.; Lime, D.W. Tourism Carrying Capacity: Tempting Fantasy or Useful Reality? Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2001, 9, 372–388. [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. (1987). Our Common Future. Oxford University Press.

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable Tourism: A State-of-the-art Review. Tourism Geographies 1999, 1, 7–25. [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S. New Performance Indicators for Water Management in Tourism. Tourism Management 2015, 46, 233–244.

- Richards, G. Cultural Tourism: A Review of Recent Research and Trends. Journal of hospitality and tourism management 2018, 36, 12–21.

- Streimikiene, D.; Svagzdiene, B.; Jasinskas, E.; Simanavicius, A. Sustainable Tourism Development and Competitiveness: The Systematic Literature Review. Sustainable Development 2021, 29, 259–271. [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, J. Tourism for Change: Change Management towards Sustainable Tourism Development. In Tourism, change and the Global South; Routledge, 2021; pp. 15–32.

- Hall, C.M. Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships; Themes in tourism; 2. ed.; Prentice Hall: Harlow Munich, 2008; ISBN 978-0-13-204652-7.

- Inskeep, E. Tourism Planning: An Emerging Specialization. J. of the Am. Planning Association 1988, 54, 360–372. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships; Pearson education, 2008;

- Coccossis, H. Sustainable Development and Tourism: Opportunities and Threats to Cultural Heritage from Tourism. In Cultural tourism and sustainable local development; Routledge, 2016; pp. 65–74.

- Baud-Bovy, M. New Concepts in Planning for Tourism and Recreation. Tourism Management 1982, 3, 308–313.

- Costa, C. An Emerging Tourism Planning Paradigm? A Comparative Analysis between Town and Tourism Planning. Journal of Tourism Research 2001, 3, 425–441. [CrossRef]

- Williams, P.W.; Gill, A. Tourism Carrying Capacity Management Issues. In Global tourism; Routledge, 2013; pp. 246–261.

- Butler, R.W. Tourism Carrying Capacity Research: A Perspective Article. Tourism Review 2020, 75, 207–211.

- Ruhanen *, L. Strategic Planning for Local Tourism Destinations: An Analysis of Tourism Plans. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development 2004, 1, 239–253. [CrossRef]

- Soteriou, E.C.; Coccossis, H. Integrating Sustainability into the Strategic Planning of National Tourism Organizations. Journal of Travel Research 2010, 49, 191–205. [CrossRef]

- Ladeiras, A.; Mota, A.; Costa, J. Strategic Tourism Planning in Practice: The Case of the Open Academy of Tourism. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes 2010, 2, 357–363. [CrossRef]

- Butler, R. Modelling Tourism Development: Evolution, Growth and Decline. Tourism development and growth. The challenge of sustainability 1997, 109–125.

- Simpson, K. Strategic Planning and Community Involvement as Contributors to Sustainable Tourism Development. Current Issues in Tourism 2001, 4, 3–41. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M. Changing Paradigms and Global Change: From Sustainable to Steady-State Tourism. Tourism Recreation Research 2010, 35, 131–143. [CrossRef]

- Alberti, M.P.P. Le Località Periferiche Del Turismo Secondo La" Teoria Delle Regioni Periferiche" Del Christaller. Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana 1973, 381–384.

- Christaller, W. Die Zentralen Orte in Suddeutschland, Jena. Central Places in Southern Germany 1933.

- ISTAT―Istituto Nazionale Di Statistica. Available Online: Https://Esploradati.Istat.It/Databrowser/#/En (Accessed on 22 September 2022) Available online: https://esploradati.istat.it/databrowser/#/en (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- ISTAT―Istituto nazionale di statistica. Available online: https://www.istat.it/classificazione/principali-statistiche-geografiche-sui-comuni/ (accessed on 22 October 2022).

- ISPRA―Istituto Superiore per La Protezione e La Ricerca Ambientale. Available Online: Https://Www.Catasto-Rifiuti.Isprambiente.It/Index.Php?Pg= (Accessed on 22 September 2022) Available online: https://www.catasto-rifiuti.isprambiente.it/index.php?pg=&width=1920&height=1080 (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- ISTAT―Istituto nazionale di statistica. Available online: https://www.istat.it/statistiche-per-temi/focus/informazioni-territoriali-e-cartografiche/rappresentazioni-cartografiche-interattive/mappa-dei-rischi-dei-comuni-italiani/indicatori/ (accessed 22 September 2022).

- MiC―Ministero Della Cultura . Available Online: Http://Www.Sistan.Beniculturali.It/Servizi_aggiuntivi.Htm (Accessed on 23 September 2022). Available online: http://www.sistan.beniculturali.it/Servizi_aggiuntivi.htm (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- ISTAT―Istituto nazionale di statistica. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/sistema-informativo-6/banca-dati-territoriale (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- RFI― Rete Ferroviaria Italiana SpA. Available online: https://www.rfi.it/it/stazioni.html (accessed on 22 October 2022) Available online: https://www.rfi.it/content/rfi/it/stazioni.html (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- McElroy, J.L.; De Albuquerque, K. Tourism Penetration Index in Small Caribbean Islands. Annals of tourism research 1998, 25, 145–168.

- Coccossis, H.; Mexa, A.; Collovini, A.; Parpairis, A.; Konstandoglou, M. Defining, Measuring and Evaluating Carrying Capacity in European Tourism Destinations. Environmental Planning Laboratory, Athens 2001.

- The European Tourism Indicator System: ETIS Toolkit for Sustainable Destination Management; European Commission, Ed.; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2016; ISBN 978-92-79-55249-6.

- Leka, A.; Lagarias, A.; Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A. Development of a Tourism Carrying Capacity Index (TCCI) for Sustainable Management of Coastal Areas in Mediterranean Islands–Case Study Naxos, Greece. Ocean & coastal management 2022, 216, 105978.

- Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations A Guidebook (English Version); World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), Ed.; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), 2004; ISBN 978-92-844-0726-2.

- Castellani, V.; Sala, S.; Pitea, D. A New Method for Tourism Carrying Capacity Assessment. WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment 2007, 106, 365–374.

- Bencardino, M.; Esposito, V. Evaluation of Tourist Intensity in the South Italy and Empirical Evidence. In Networks, Markets & People; Calabrò, F., Madureira, L., Morabito, F.C., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2024; Vol. 1184, pp. 319–330 ISBN 978-3-031-74607-9.

| Correction Factors | Indicators | Description | Variables | Reference | Source | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological Endowment Composite Index (EEI) | ||||||

| Ecf1 | Population density | Ratio of administrative municipality's land area to resident population [number of inhabitants per sq. km] | Resident | [106] | ISTAT | 2021 |

| Land area (sq. km.) | [106] | ISTAT | 2021 | |||

| Ecf2 | Ecological efficiency | Sorted municipal waste fraction detected in the administrative municipality [%] | Separate waste [t] | [106] | ISPRA | 2020 |

| Ecf3 | Ecological pressure | Municipal Waste generated by municipal inhabitants [kg] | Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) [t] | [108] | ISPRA | 2020 |

| Ecf4 | Environmental endowment | Presence of Protected Areas (EUAP2010) [%] | Protected Areas (EUAP2010) [h] | [109] | ISTAT | 2010 |

| Ecf5 | Unconsumed land | Share of unsealed land [%] | Unconsumed land [h] | [108] | ISPRA | 2019 |

| Infrastructure Endowment Composite Index (IEI) | ||||||

| Icf1 | Prevailing tourism supply | Relationship between hotel receptivity with non-hotel receptivity | Bed-places in hotel and non-hotel accommodations | [106] | ISTAT | 2019 |

| Icf2 | Tourism accommodation offer intensity | Ratio of total beds in accommodations to municipal population | Bed-places in hotel and non-hotel accommodations | [106] | ISTAT | 2019 |

| Icf3 | Material cultural heritage endowment | Number of archaeological assets and number of architectural assets | Number of subway stations | [110] | MIC | 2017 |

| Icf4 | Station intensity for passenger transport | Ratio of the number of railway stations and metro stations to the territorial area of the administrative municipality [per 100 sq. km] | Number of stations belonging to the categories: Platinum; Gold; Silver and Bronze | [111] | ISTAT | 2015 |

| [112] | RFI | 2022 | ||||

| Icf5 | Local public transport offer | Ratio of the number of vehicles for local public transport (LPT) to residents | Number of bus and trolleybus cars intended for passenger transport | [111] | ISTAT | 2015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).