Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

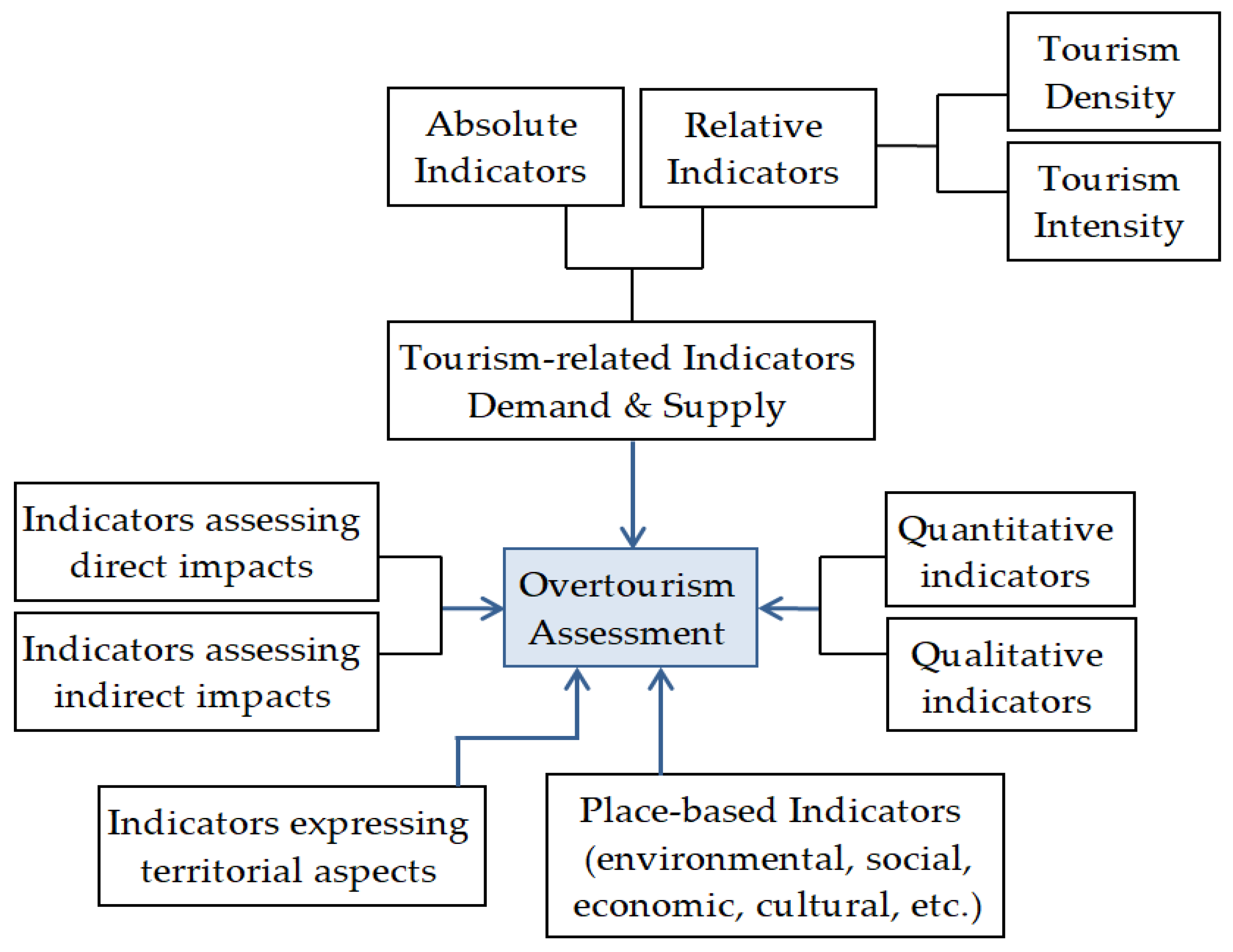

2. Literature Review on Indicators for Assessing Overtourism

3. Methodology & Data

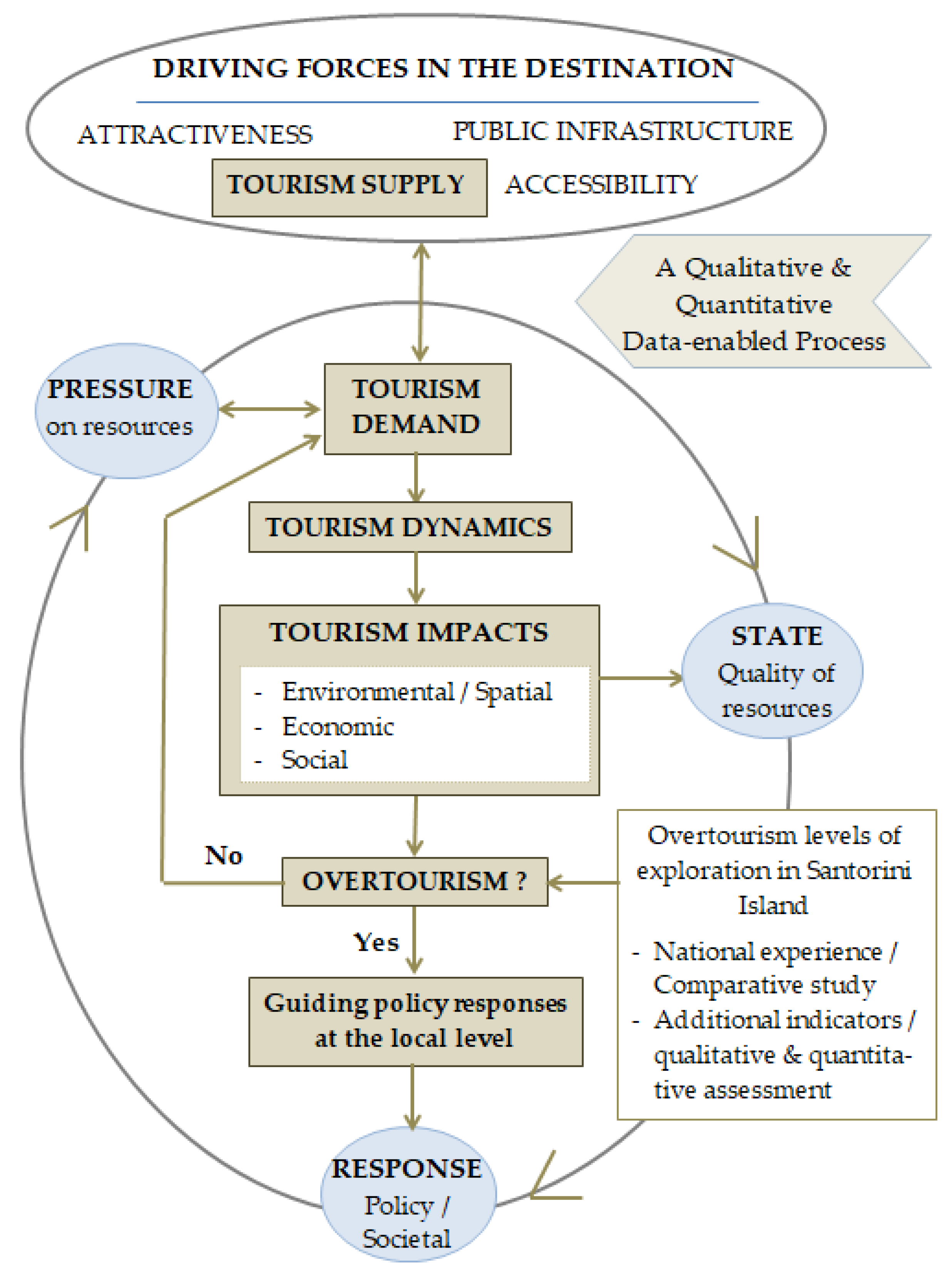

3.1. Methodology

- The very essence of the tourism phenomenon and its main constituents, i.e. supply, demand, and destination’s tourism and other infrastructure as well as their impacts on the particular natural, cultural and human context of each single destination.

- The PSR – Pressure/State/Response model as a structured, well-proven and robust framework [47] for better understanding actions and activities that are affecting the state of a system; and are feeding appropriate policy response for addressing them. This builds upon a range of properly selected indicators and can orient evidence- and place-based policy reaction of, among others, the overtourism phenomenon.

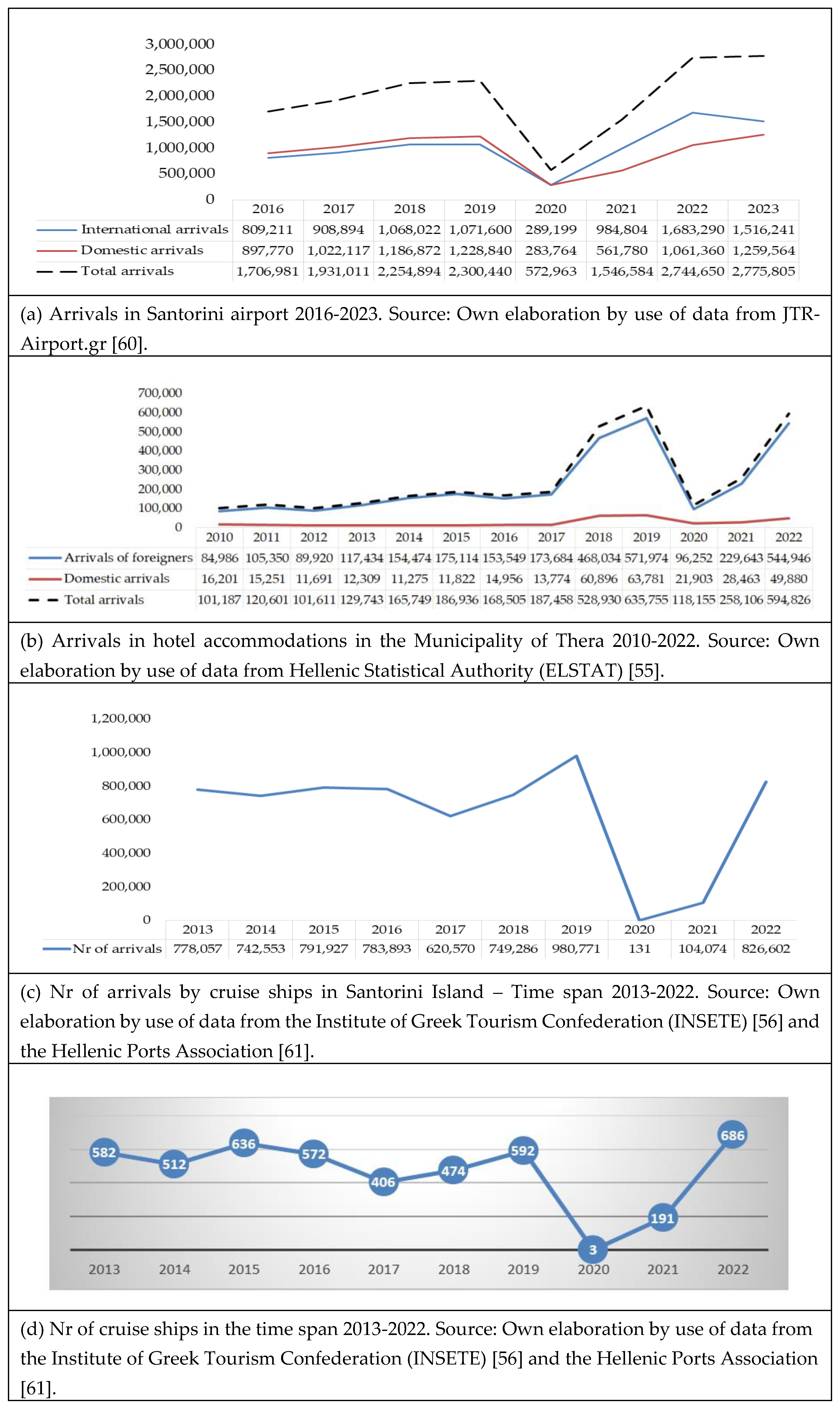

3.2. Data and Indicators

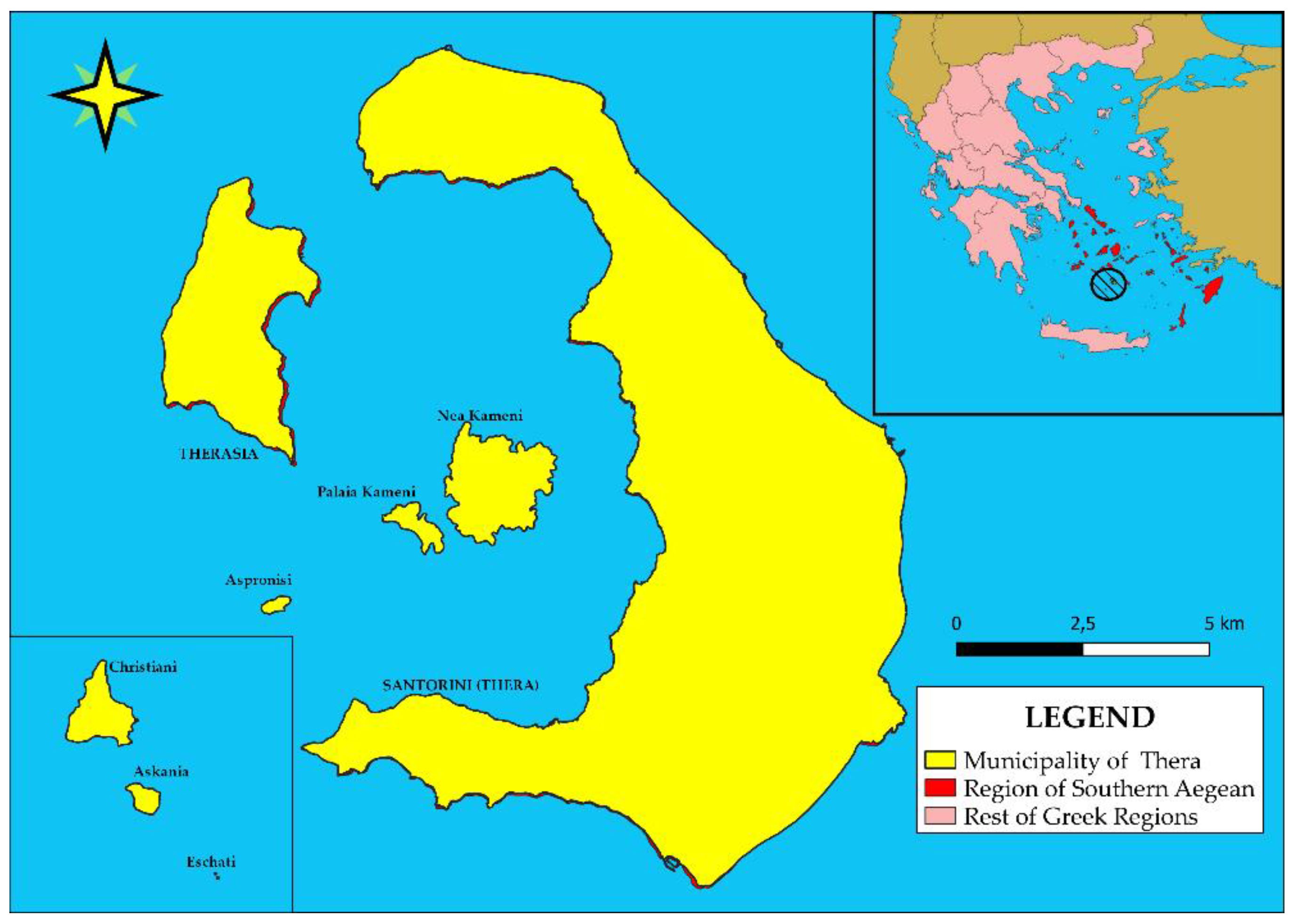

4. Featuring the Evolving Tourism Dynamics in Santorini Island

5. Assessing Overtourism Signs in Santorini Island – Empirical Results

- firstly, a comparative assessment is carried out, based on indicators’ calculation – tourist supply TSi and demand TDi indicators – for all islands of the Cyclades complex in order for positioning Santorini Island in the immediate insular context, namely the Cyclades Regional Entity (part of the Southern Aegean Region), being a highly touristic insular entity of the Greek territory (Table 6 and Table 7);

- secondly, an integrated assessment of the state of Santorini Island is conducted, taking into account the values of indicators associated with the tourism supply and demand; sustainability indicators (environmental, economic and social); and the spatial pattern of tourism development and related implications (Table 8 and Table 9).

- The central and southern part of the island (Zones 3 and 4) are the most heavily impacted by construction, followed by the northern part (Zone 2 mainly, and next Zone 1).

- All zones, apart from Zone 6, are characterized by significant environmental vulnerability (maximized in Zone 5 that includes the archaeological zone of Akrotiri), while building within protected areas can reach up to 12.7% of land (Zone 4).

- Vegetation health and coverage (as captured by NDVI) is rapidly decreasing in the past years, with these attributes displaying a more rapid pace in Zones 3, 4, and 5.

- Agricultural land (as depicted by Corine Land Cover) is rapidly shrinking over the past three decades, rising to a 25% per cent on the island level and above 40% in the northern part of Santorini as well as the Therasia land. A significant percentage of remaining wider agricultural zones is now left uncultivated, especially in the central-southern part (Zones 3, 4 and 5).

- Large scale tourism infrastructure that includes 4* and 5* hotels of significant bed capacity, pools and other auxiliary spaces covering large plots, is estimated to a significant 12-18% coverage of total artificial land, located in the northern and central part; while such infrastructure dominates (35%) in the Akrotiri territory (Zone 5), where no significant local settlement is established.

- Santorini at an overall level presents significant loss of housing affordability as the mean rental price is 56% higher than the average for Cyclades and Attika Region; while mean price for sale is 100% higher. This is clearly manifested in the extreme difficulties reported especially for deputy school teachers to find a residence when they arrive to the island, but certainly it also affects various groups of local population.

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Misrahi T. What will travel look like in 2030? World Economic Forum, (2016), Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/09/what-will-travel-look-like-in-2030/ (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Zolfani, S.H.; Sedaghat, M.; Maknoon, R.; Zavadskas, E.K. Sustainable tourism: a comprehensive literature review on frameworks and applications. Econ. Res. 2015, 28(1), 1–30. [CrossRef]

- UNWTO (n.d.). Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development (accessed on 16 October 2024).

- OECD. Rethinking tourism success for sustainable growth. In Tourism Trends and Policies 2020; OECD, Ed.; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; ISSN: 20767773 (online), Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/6b47b985-en.pdf?expires=1731843712&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=9306352C569EF690D59EECBEC18DA594 (accessed on 16 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Koutsi, D.; Lagarias, A.; Stratigea, A. Evidence-based exploration as the ground for heritage-led pathways in insular territories: Case study Greek Islands. Heritage 2022, 5(3), 2746–2772. [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tourism Geographies 1999, 1(1), 7–25. [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, S.S.; Mijts, E.; Van Rompaey, A. Are there limits to growth of tourism on the Caribbean islands? Case-study Aruba. Front. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 3, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Leka, A.; Lagarias, A.; Panagiotopoulou, M.; Stratigea, A. Development of a Tourism Carrying Capacity Index (TCCI) for sustainable management of coastal areas in Mediterranean Islands – Case Study Naxos, Greece. Ocean & Coastal Management 2022, 216, 105978. [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.; Dodds, R. Island tourism: Vulnerable or resistant to overtourism? Highlights of Sustainability 2022, 1(2), 54–64. [CrossRef]

- UN Tourism (n.d.) Tourism in Small Island Developing States (SIDS). Available online: https://www.unwto.org/sustainable-development/small-islands-developing-states (accessed on 9 November 2024).

- Graci, S.; Dodds, R. Sustainable Tourism in Island Destinations. Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2010; ISBN 9781844077809.

- Coppin, F.; Guichard, V. Tourism as a tool for social and territorial cohesion - Exploring the innovative solutions developed by INCULTUM pilots. In Innovative Cultural Tourism in European Peripheries; K. J. Borowiecki, A. Fresa and J. M. Martín Civantos, Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 7–27; ISBN 9781032728995.

- Koens, K.; Postma, A.; Papp, B. Is overtourism overused? Understanding the impact of tourism in a city context. Sustainability 2018, 10(12), 4384. [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Stettler, J.; Crameri, U.; Eggli, F. Measuring overtourism. Indicators for overtourism: Challenges and opportunities. Lucerne University of Applied Sciences and Arts, Hochschule Luzern, Institut für Tourismus Wirtschaft, ISBN: 978-3-033-07773-7, 2020, Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344282239_Measuring_Overtourism_Indicators_for_overtourism_Challenges_and_opportunities (accessed on 12 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wall, G. From carrying capacity to overtourism: A perspective article. Tourism Review 2020, 75(1), 212–215. [CrossRef]

- Zemla, M. Overtourism and local political debate: is the over-touristification of cities being observed through a broken lens? Entrepreneurship – Education 2024, 20(1), 215–225. [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.; Gössling, S.; Klijs, J.; Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Dijkmans, C.; Eijgelaar, E.; Hartman, S.; Heslinga, J.; Isaac, R.; Mitas, O.; Moretti, S.; Nawijn, J.; Papp, B.; Postma, A. Research for TRAN Committee -Overtourism: impact and possible policy responses, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels, 2018.

- Capocchi, A.; Vallone, C.; Amaduzzi, A.; Pierotti, M. Is ‘overtourism’ a new issue in tourism development or just a new term for an already known phenomenon? Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23(18), 2235–2239. [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Koo C. The use of social media in travel information search. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32(2), 215–229. [CrossRef]

- Huertas, A. How live videos and stories in social media influence tourist opinions and behaviour. Inf. Technol. Tour. 2018, 19, 1–28. [CrossRef]

- UNWTO. “Overtourism”? Understanding and managing urban tourism growth beyond perceptions. United Nations World Tourism Organization: Madrid, Spain; 2018.

- Dredge, D. “Overtourism” - Old wine in new bottles? 2017, Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/overtourism-old-wine-new-bottles-dianne-dredge/ (accessed on 14 November 2024).

- Mihalic, T. Conceptualizing overtourism: A sustainability approach. Annals of Tourism Research 2020, 84, 103025. [CrossRef]

- Gowreesunkar, V. G.; Thanh, T. V. Between overtourism and under- tourism: Impacts, implications, and probable solutions. In Overtourism: Causes, Implications and Solutions; H. Séraphin, Gladkikh, T., Vo Thanh, T., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 45–68. [CrossRef]

- Mihalic, T.; Kuščer, K. Can overtourism be managed? Destination management factors affecting residents’ irritation and quality of life. Tourism Review 2021, 77(1), 16–34. [CrossRef]

- Adie, B. A.; Falk, M. Residents’ perception of cultural heritage in terms of job creation and overtourism in Europe. Tourism Economics 2021, 27(6), 1185–1201. [CrossRef]

- Goessling, S.; McCabe, S.; Chen, N. A socio-psychological conceptualisation of overtourism. Annals of Tourism Research 2020, 84, 102976. [CrossRef]

- Vourdoubas, J. Evaluation of overtourism in the island of Crete, Greece. European Journal of Applied Science, Engineering and Technology 2024, 2(6), 21–32. [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Cheer, J. M.; Novelli, M. Overtourism: an evolving phenomenon. In Overtourism: Excesses, discontents and measures in travel and tourism; C. Milano, J. M. Cheer, M. Novelli, Eds.; CAB International: Oxfordshire, UK, 2019; pp. 1–17.

- García-Buades M. E.; García-Sastre, M. A.; Alemany-Hormaeche, M. Effects of overtourism, local government, and tourist behavior on residents’ perceptions in Alcúdia (Majorca, Spain). Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism 2022, 39, 100499. [CrossRef]

- Saveriades, A. Establishing the social tourism carrying capacity for the tourist resorts of the east coast of the Republic of Cyprus. Tourism Management 2000, 21(2), 147–156. [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Russo, A.P. Anti-tourism activism and the inconvenient truths about mass tourism, touristification and overtourism. Tourism Geographies 2024, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Buitrago, E.M.; Yñiguez, R. Measuring overtourism: A necessary tool for landscape planning. Land 2021, 10(9), 889. [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. W. Introduction. In Overtourism: Issues, Realities and Solutions; R. Dodds, R. W. Butler, Eds.; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin/Boston, 2019; pp. 1–21.

- Gretzel, U. The role of social media in creating and addressing overtourism. In Overtourism: Issues, realities and solutions; R. Dodds, R. W. Butler, Eds.; Walter de Gruyter GmbH: Berlin/Boston, 2019; pp. 263–276.

- Lagarias, A.; Stratigea, A.; Theodora, Y. Overtourism as an emerging threat for sustainable island communities – Exploring indicative examples from the South Aegean Region, Greece. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2023 Workshops. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; O. Gervasi, B. Murgante, A. M. A. C. Rocha. Ch. Garau, F. Scorza, Y. Karaca, C. M. Torre, Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Part VII, Vol. 14110, pp. 404–421. [CrossRef]

- Constantoglou, M.; Klothaki, T. How much tourism is too much? Stakeholder’s perceptions on overtourism, sustainable destination management during the pandemic of COVID 19 era in Santorini Island Greece. Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management 2021, 9(5), 288–313. [CrossRef]

- Stanchev, R. The most affected European destinations by over-tourism. Universitat de les Illes Balears, Facultat de Turisme, Grau de Turisme, Any acadèmic 2017-18, Available online: https://dspace.uib.es/xmlui/bitstream/handle/11201/148140/Stanchev_Rostislav148140.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Wilson, N. 30 destinations cracking down on overtourism, from Venice to Bhutan. Independent, 2024, Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/sustainable-travel/destinations-cracking-down-overtourism-venice-b2587510.html (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Bateman, J. Santorini under Pressure: The Threat of Overtourism, 2019, Available online: https://www.greece-is.com/santorini-pressure-threat-overtourism/ (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- O'Toole, L. Beautiful European Island under pressure where even tourists complain about the tourists, Daily Express, 2024, Available online: https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/1910789/santorini-greece-overtourism-tourists-news (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Simancas Cruz, M.; Pilar Peñarrubia Zaragoza, M. Analysis of the accommodation density in coastal tourism areas of insular destinations from the perspective of overtourism. Sustainability 2019, 11(11), 3031. [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, M.; Moraes, M.; Breda, Z.; Guizi, A.; Costa, C. Overtourism and tourismphobia. Tourism: An International Interdisciplinary Journal 2020, 68(2), 156–169. [CrossRef]

- Bambrick, H. Resource extractivism, health and climate change in small islands. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management 2017, 10(2), 272–288. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.N.; Pigozzi, B.W.; Sambrook, R.A.: Tourist carrying capacity measures: Crowding syndrome in the Caribbean. The Professional Geographer 2005, 57(1), 13–20. [CrossRef]

- Panousi, S.; Petrakos, G.: Overtourism and tourism carrying capacity - A regional perspective for Greece. In Culture and Tourism in a Smart, Globalized, and Sustainable World; V. Katsoni, C. Ciná van Zyl, Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 215–229. [CrossRef]

- OECD Environment at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Official administrative boundaries. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/digital-cartographical-data (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Imperviousness Classified Change Layer. [CrossRef]

- Archaeological zones. Available online: https://www.arxaiologikoktimatologio.gov.gr/en.

- Natura 2000 areas and Wildlife Repositories of Greece. Available online: https://geodata.gr/en/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Agricultural land change. (vector 2018). [CrossRef]

- Agricultural land change. (vector 1990). [CrossRef]

- Coastal Zones Land Cover / Land Use 2018 (vector), Europe, 6-yearly, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT). Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/home/ (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Institute of the Association of Greek Tourism Enterprises (INSETE). Available online: https://insete.gr/districts/?lang=en (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Airbnb accommodation. Available online: https://bfortune.opendatasoft.com/explore/dataset/Airbnb-listings/export/?disjunctive.neighbourhood&disjunctive.column_10&disjunctive.city&q=santorini (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Hellenic Chamber of Hotels. Available online: https://www.grhotels.gr/en/tourist-guide/search-hotels-and-camping/ (accessed on 8 October 2024).

- Spiti24. Available online: https://www.spiti24.gr/ (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- JTR-Airport (Santorini Airport). Available online: https://www.jtr-airport.gr/en (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- Hellenic Ports Association. Available online: https://www.aivp.org/en/aivp/our-members/directory/hellenic-ports-association/ (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Institute of the Association of Greek Tourism Enterprises (INSETE). The contribution of tourism in the Greek economy in 2023, 2024. Available online: https://insete.gr/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/23_04_Tourism_and_Greek_Economy_2019-2023.pdf.

- Donaire, A.J.; Galí, N.; Coromina, L. Evaluating tourism scenarios within the limit of acceptable change framework in Barcelona. Annals of Tourism Research Empirical Insights 2024, 5(2), 100145. [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2018, 9, 374-376. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Prayag, G.; Safonov, A.; Coles, T.; Gössling, S.; Naderi Koupaei, S. Airbnb and the sharing economy. Current Issues in Tourism 2022, 25(19), 3057-3067. [CrossRef]

- Butler, R.W. Sustainable Tourism in Sensitive Environments: A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing? Sustainability 2018, 10(6), 1789. [CrossRef]

- Bastakis, C.; Buhalis, D.; Butler, R. The perception of small and medium sized tourism accommodation providers on the impacts of tour operators’ power in Eastern Mediterranean. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25(2), 151–170. [CrossRef]

| a/a | Indicator | Description of Indicator (Calculations in Year 2023) |

| 1 | TS1 - Tourism Intensity Index | [Total Tourism Accomodation (hotel and Airbnb Beds) / Permanent Population (Residents)] TS1 features the pressure on population that is due to tourism accommodation infrastructure. |

| 2 | TS2 – Airbnb Intensity Index | [Total Airbnb beds / Permanent Population (Residents)] TS2 highlights the pressure on population due to the Airbnb tourism supply. |

| 3 | TS3 – Tourism Infrastructure Indensity Index | ]Nr of hotels and Airbnb accommodation / Permanent Population (Residents)] TS3 assesses the pressure on population that is due to tourism infrastructure deployment. |

| 4 | TS4 – Tourism Index | [Total Tourist Accomodation (hotel & Airbnb Beds) * 100] / [Permanent population (Residents) * Total Area in km2] TS4 sketches the tourism saturation level. |

| 5 | TS5 – Tourism Infrastructure Index | [(Nr of hotels and Airbnb) * 100] / [Permanent Population (Residents) * Total Area in km2] TS5 demonstrates the pressure of tourism inrastructure on the destination (local population and area). |

| 6 | TS6 – Tourism Infrastructure Density Index | [Nr of hotels and Airbnb / Total Area in km2] TS6 reflects the spatial pressure on the destination that is due to the deployment of accommodation infrastructure. |

| a/a | Indicator | Description of Indicator (Calculations in Year 2022) |

| 1 | TD1 - Tourism Intensity Index | [Total Hotel Arrivals *100 / Permanent Population] TD1 features the pressure of tourist flows on the population. |

| 2 | TD2 - Attracti- veness Index | [Foreign Arrivals (hotels) / Domestic Arrivals (hotels)] TD2 expresses the attractiveness of a destination to foreigners compared to domestic tourist flows. |

| 3 | TD3 - Tourism Penetration Index | [Overnights of Foreigners (hotels) * 100] / [Permanent population * 360] TD3 determines the penetration of foreign visitors in a place in relation to the local resident population. |

| 4 | TD4 - Tourism Concentration Index (density) | [Total Overnight Stays (Hotels) / Total Area in km2] TD4 demonstrates visitors’ willingness to stay in a specific destination and thus pressure exerted on its local resources. |

| 5 | TD5 - Tourism Overnight Stays Index (intensity) | [Total Overnight Stays (Hotels) / [Permanent Population] TD5 demonstrates the potential pressure on the local population. |

| Indicator | Description of Indicator | |

|---|---|---|

| a/a | Environmental/ Spatial | |

| 1 | EN1 - Environmental Vulnerability | [% area falling into the NATURA 2000 network] EΝ1 displays areas with high natural value, manifesting vulnerability/risk of environmental degradation due to tourism activities. |

| 2 | EN2 - Share of Built-up Space |

[% built-up space in 2018] EΝ2 demonstrates the environmental pressure due to urban sprawl, i.e. the evolving built-up areas pattern due to mainly tourism accommodation deployment. |

| 3 | EN3 - Change of Built-up Space |

[Mean annual rate of built-up area change (2006-2018) multiplied by 1000] EΝ3 displays the evolving land use change patterns that are mainly due to developments in the tourism sector. |

| 4 | EN4 - Vegetation Change Index |

[% change (2017-2024)] EΝ4 features the loss of green space with repercussions in the microclimate and degradation of the landscape. |

| 5 | EN5 - Built-up Areas within Protected Zones (Natura 2000, archaeological zones etc.) | [% of built-up areas within protected zones in 2018] EΝ5 highlights the penetrating nature of built-up areas due to mainly tourism demand, expanding into protected zones. |

| 6 | EN6 - Built-up Areas within Protected Zones (Natura 2000, archaeological zones etc.) | [Mean annual rate of built-up areas within protected zones in 2006-2018 multiplied by 1000] EΝ6 displays the mean annual rate of the aforementioned expansion. |

| a/a | Economic | |

| 1 | EC1 – Available Agricultural Land | [% of agricultural zones (2019)] |

| 2 | EC2 – Agricultural cultivation | % of (wider) agricultural zones still cultivated |

| 3 | EC3 - Loss of Agricultural Land | [% agricultural land change (1990-2018)] EC3 features the pressure of mainly tourism on the agricultural sector, placing at stake traditional production patterns, especially in insular destinations. |

| 4 | EC4 – Employ- ment Pattern | [Share of employment % (primary, secondary and tertiary sector, rate of change 2001-2011, 2011-2021)] EC4 features the impacts of tourism on the employment pattern of a destination. |

| a/a | Social | |

| 1 | S1 - Large-scale Tourism Infrastructure | [% built-up space in 2018 that is attributed to large-scale tourism infrastructure] S1 features the social / psychological pressure due to large-scale tourism development and relevant land-take. |

| 2 | S2a - Loss of Housing Affordability | [Ratio1: Ratio between land rent for housing in the destination and mean value at the territorial level] S2a features the pressure on permanent residents not being able to find affordable housing due to tourism pressure on land values. |

| 3 | S2b - Loss of Housing Affordability | [Ratio2: Ratio between land sale value in the destination and mean value at the territorial level] S2b features the pressure on permanent residents not being able to buy houses due to tourism pressure on land values. |

| Type / Source of Data |

|---|

| Imperviousness Classified Change Layer (raster 20 m) covering the period 2006-2018, 3-yearly: provides, at pan-European level, the degree of imperviousness change in the categories of sealing change (unchanged no sealing, new cover, loss of cover, unchanged sealed, increased sealing, decreased sealing) between each two Imperviousness Density status layers [49]. |

| Archaeological zones: obtained from the geospatial platform of the Archaeological Cadastre of Greece, recording and documenting Greece's immovable monuments, archaeological sites, historical sites, and their protection zones [50]. |

| Natura 2000 areas and Wildlife Repositories of Greece: obtained from the Geodata portal of Greece [51]. The “Kaldera” volcanic zone of Santorini Island is simultaneously part of both networks, and is also recently at the exploration stage as a candidate to the UNESCO World Geological Sites. |

| Agricultural land change: obtained for a large time span, based on Corine Land Cover database availability, DOI (vector 2018): [52], and DOI (vector 1990): [53]. Codes 221, 242, and 243 are applicable in Santorini and the changes are identified by comparing all relevant classes. To more accurately estimate the remaining agricultural zones in 2019, a fine resolution global dataset is used, namely COPERNICUS / Landcover / 100m / Proba-V-C3 / Global / 2019) (km). To identify agricultural land still cultivated (vineyards and arable land) and their relationship to artificial areas, the Coastal Zones Land use / Landcover database [54] and part of the European Union’s Copernicus Land Monitoring Service are used. |

| NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index): obtained by both Landsat 8 satellite images, at 30m resolution and Harmonized Sentinel-2 MSI, MultiSpectral images, at 10m resolution. Data are processed through Google Earth Engine, and the difference of NDVI between 2016-2024 (Landsat 8) and 2017-2024 is obtained at the pixel level. NDVI values are obtained at each case as the maximum pixel value during the summer period of each reference year. |

| Population: Data on permanent population is derived from the 2021 National Census of the Hellenic Statistical Authority [55]. |

| Tourism arrivals: derived from the annual report of the Institute of the Association of Greek Tourism Enterprises (INSETE) [56]. The Annual Report of each Region/District includes: Demographic data, Macroeconomic data, Tourism infrastructure, Arrivals-Night stays and Revenues, key indicators (Average Per Capita Expenditure, Expenditure per Night and Average Length of Stay), Employment etc. It should be noted here the lack of data on Airbnb arrivals. |

| Airbnb accommodation: gathered through the open data source platform [57]. |

| Hotel accommodation: emanates from the Hellenic Chamber of Hotels [58]. |

| Land values: estimated through the commercial real estate platform Spiti24 [59], by defining a specific zone and obtaining mean values for rental and sale. |

| Tourism Supply | Tourism Demand |

|---|---|

| Nr of hotels 2012-2023 | Arrivals by air 2010-2022 |

| Nr of hotel rooms 2012-2023 | Arrivals in hotels 2010-2022 |

| Nr of hotel beds 2012-2023 | Arrivals by cruise ships 2013-2022 |

| Nr of Airbnb beds 2023 | Nr of cruise ships 2013-2022 |

| Indicator | TS1 | TS2 | TS3 | TS4 | TS5 | TS6 | |

| Island | |||||||

| Santorini/Thera | 1.83 | 0.69 | 0.33 | 2.00 | 0.36 | 56.40 | |

| Mykonos | 2.70 | 1.16 | 0.34 | 2.57 | 0.32 | 34.63 | |

| Folegandros | 1.82 | 0.43 | 0.22 | 5.68 | 0.69 | 4.97 | |

| Ios | 1.45 | 0.47 | 0.18 | 1.33 | 0.17 | 3.88 | |

| Paros | 1.20 | 0.70 | 0.23 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 16.68 | |

| Naxos | 0.76 | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 6.51 | |

| Amorgos | 0.67 | 0.38 | 0.17 | 0.53 | 0.13 | 2.57 | |

| Sifnos | 1.07 | 0.68 | 0.24 | 1.44 | 0.32 | 8.86 | |

| Antiparos | 1.01 | 0.68 | 0.19 | 2.24 | 0.43 | 5.38 | |

| Milos | 0.74 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.46 | 0.12 | 6.60 | |

| Sikinos | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.12 | 1.14 | 0.28 | 0.71 | |

| Serifos | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.31 | 1.25 | 0.41 | 5.04 | |

| Anafi | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 1.12 | 0.40 | 1.16 | |

| Kea | 1.14 | 0.89 | 0.22 | 0.76 | 0.15 | 3.47 | |

| Andros | 0.47 | 0.32 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 2.54 | |

| Syros | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.05 | 10.23 | |

| Indicator | TD1 | TD2 | TD3 | TD4 | TD5 | |

| Island | ||||||

| Santorini/Thera | 3837.16 | 10.93 | 28.50 | 19137.23 | 112.03 | |

| Mykonos | 5501.23 | 11.22 | 49.01 | 19369.64 | 190.34 | |

| Folegandros | 3102.19 | 7.65 | 22.63 | 2114.82 | 94.76 | |

| Ios | 2372.99 | 3.86 | 17.04 | 1669.13 | 79.15 | |

| Paros | 976.69 | 3.08 | 8.17 | 2835.09 | 38.33 | |

| Naxos | 616.25 | 2.87 | 5.37 | 1026.74 | 24.74 | |

| Amorgos | 571.85 | 2.64 | 5.12 | 375.60 | 24.20 | |

| Sifnos | 703.10 | 2.76 | 4.13 | 755.06 | 20.10 | |

| Antiparos | 503.64 | 1.61 | 3.73 | 571.44 | 20.41 | |

| Milos | 524.52 | 1.98 | 2.86 | 492.45 | 14.87 | |

| Sikinos | 326.20 | 7.68 | 2.38 | 59.30 | 9.96 | |

| Serifos | 485.01 | 1.42 | 2.24 | 219.01 | 13.27 | |

| Anafi | 275.18 | 10.91 | 2.11 | 60.32 | 8.31 | |

| Kea | 342.01 | 0.48 | 1.10 | 153.55 | 9.79 | |

| Andros | 300.95 | 0.52 | 1.08 | 227.17 | 9.78 | |

| Syros | 275.18 | 0.57 | 1.04 | 1819.11 | 8.78 | |

| Share (Rate of Change | Share % in 2001 | Share % in 2011 (% change 2001-2011) |

Share % in 2021 (% change 2011-2021) |

|

| Sector | ||||

| Primary | 5.52 | 4.18 (-1.34) | 3.67 (-0.51) | |

| Secondary | 25.72 | 17.63 (-8.09) | 5.60 (-12.03) | |

| Tertiary | 68.77 | 78.18 (+9,41) | 90.66 (+12.48) | |

| a/a | Santorini Island | Total Area | Zone 1 |

Zone 2 |

Zone 3 |

Zone 4 |

Zone 5 |

Zone 6 |

|

| Indicator | |||||||||

| EN1 | Environmental vulnerability | 23.0 | 19.8 | 29.1 | 21.4 | 33.5 | 66.8 | - | |

| EN2 | Share of built-up space | 36.6 | 19.8 | 29.1 | 34.0 | 56.2 | 17.8 | - | |

| EN3 | Change of built-up space | 3.1 | 2.9 | 7.2 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

| EN4 | Vegetation change index | -20.7 | -15.3 | -18.4 | -28.1 | -25.6 | -23.6 | -14.6 | |

| EN5 | Built-up within protected zones | 6.4 | 8.5 | 3.7 | 12.7 | 6.3 | 4.0 | - | |

| EN6 | Built-up within protected zones | 0.4 | 0.2 | 4.4 | 0.0 | -0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| EC1 | Available agricultural land | 53.1 | 57.3 | 47.0 | 55.4 | 57.7 | 60.8 | 40.1 | |

| EC2 | Agricultural cultivation | 56.4 | 23.8 | 46.7 | 62.5 | 76.4 | 69.7 | 38.5 | |

| EC3 | Loss of agricultural land | 24.3 | 40.7 | 15.0 | 20.4 | 15.0 | 23.8 | 62.0 | |

| S1 | Large-scale tourism infrastructure | 11.9 | 13.5 | 17.3 | 7.8 | 6.5 | 34.5 | 0.0 | |

| S2a | Loss of housing - Afford.1 | 1.56* | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| S2b | Loss of housing - Afford.2 | 2.00* | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).