1. Introduction

With the rapid development of intelligent unmanned systems, high-precision positioning technology for unmanned clusters has become a significant challenge in its application. In dynamic scenarios, single sensors like Global Positioning System(GPS) often suffer from signal blockage and multipath effects, leading to degraded accuracy [

1,

2], while Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) accumulates errors over time and cannot support long-term localization independently [

3]. Therefore, Kalman Filter (KF) [

4]-based multi-sensor fusion has become a mainstream solution, offering optimal estimation through a state-space model and theoretically enabling error minimization and calibration. However, traditional Kalman Filter relies on fixed parameters [

5], leading to model mismatch in scenarios with motion state transitions (e.g., sudden acceleration, complex terrains) or time-varying sensor noise, which degrades localization accuracy—particularly in multi-trajectory cooperative scenarios.

Existing methods suffer from insufficient robustness in filter parameters and inefficient multi-source fusion. For example, process noise parameters in KF are typically empirically set and cannot dynamically adapt to environmental changes, causing the KF gain matrix to degrade in high-dynamic scenarios and resulting in drift. Traditional trajectory fusion also fails to fully exploit inter-trajectory correlations, such as varying covariance structures among nodes in a sensor network, making static weighting suboptimal. Reinforcement Learning, as a machine learning paradigm that optimizes decision-making through environment interaction [

6], offers a new path forward. Its trial-and-error adaptation breaks the static limitations of traditional methods.

Therefore, this study proposes a Kalman Filter localization calibration method based on reinforcement learning optimization and information matrix fusion. An Actor-Critic network architecture [

7] is constructed, where a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) [

8] captures temporal dependencies of sensor data, and an attention mechanism [

9] focuses on key state features to adaptively generate KF parameter adjustment factors. These factors dynamically regulate the state covariance matrix. Additionally, we introduce a multi-trajectory information matrix fusion algorithm that aggregates inverse covariance matrices to form a layered uncertainty calibration mechanism.

This paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews existing calibration methods;

Section 3 details the algorithm, including the network architecture, dynamic adjustment mechanism for state covariance, and the derivation of the fusion algorithm based on information matrix inversion.

Section 4 presents experimental design and results.

Section 5 concludes the study and discusses future work and applications.

2. Related Work

At present, multi-sensor fusion has become the mainstream approach for localization calibration in UAV swarms. Among them, GPS/IMU integrated navigation systems are widely used due to their complementary advantages [

10,

11]. The KF, as a classical algorithm, performs optimal recursive estimation for linear systems. To address the significant errors introduced when using KF in nonlinear scenarios [

12], several nonlinear filtering variants have been developed, including the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) [

13], Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) [

14], and Particle Filter (PF) [

15]. Moreover, to improve filter stability in high-dynamic environments, adaptive variants such as the Adaptive Kalman Filter (AKF) [

16] and Federated Kalman Filter (FKF) [

17] have been proposed. These evolutionary filtering methods provide theoretical support for achieving high-precision localization in UAV swarms operating under complex environments, aggressive maneuvers, and sensor failures.

In the development of integrated navigation technologies, machine learning-based adaptive calibration methods have gradually emerged in recent years with the advancement of deep learning and reinforcement learning [

18,

19]. These methods leverage historical data to learn complex error patterns and achieve high-precision calibration. For example, Wei et al. [

20] proposed a navigation method that integrates random forest regression with adaptive Kalman filtering to improve accuracy under limited data availability. Liu et al. [

21] proposed an integrated navigation filtering algorithm assisted by Radial Basis Function(RBF) neural network, aiming to improve the navigation accuracy of the system in the case of GPS signal loss. Other studies [

22] have combined deep learning with extended state Kalman filtering (ES-EKF), using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) [

23] networks to capture temporal dependencies in sensor data and Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) [

24] to extract spatial features. Furthermore, a reinforcement learning-based adaptive Kalman filtering algorithm (RL-AKF) [

25] has been proposed, which adaptively estimates the process noise covariance using reinforcement learning techniques. In the Kalman filter framework, the state covariance matrix plays a central role in quantifying uncertainty and directly affects the computation of the Kalman gain. However, current methods still largely rely on traditional techniques for its adaptive adjustment. Therefore, this paper proposes a reinforcement learning-based approach using an Actor-Critic architecture to dynamically adjust the state covariance matrix.

Meanwhile, in the area of multi-trajectory cooperative calibration, inter-platform information exchange is a critical component for achieving high-precision collaboration. Existing mainstream methods focus on fusion strategies for heterogeneous multi-source data. For example, in cooperative localization of UAV swarms, platforms can share position and inertial data; Ultra-Wideband (UWB) ranging technology is used to acquire relative distance constraints [

26]; Angle-of-Arrival (AOA) methods employ antenna arrays to determine signal directions [

27], forming joint constraints in distance and angle; and vision sensors can be used to capture environmental features or visual markers of other UAVs, with visual SLAM algorithms employed to extract feature correspondences and construct relative pose estimates [

28]. However, most existing approaches lack effective mechanisms for quantifying and fusing trajectory uncertainties, particularly in dynamically aggregating the covariance matrices of individual platform trajectories. Therefore, this study proposes a cooperative calibration algorithm based on multi-trajectory information matrix fusion. This approach enables a more precise characterization of uncertainty distribution across trajectories in dynamic environments and provides a novel solution for high-precision cooperative localization of UAV swarms in complex scenarios.

3. Methods

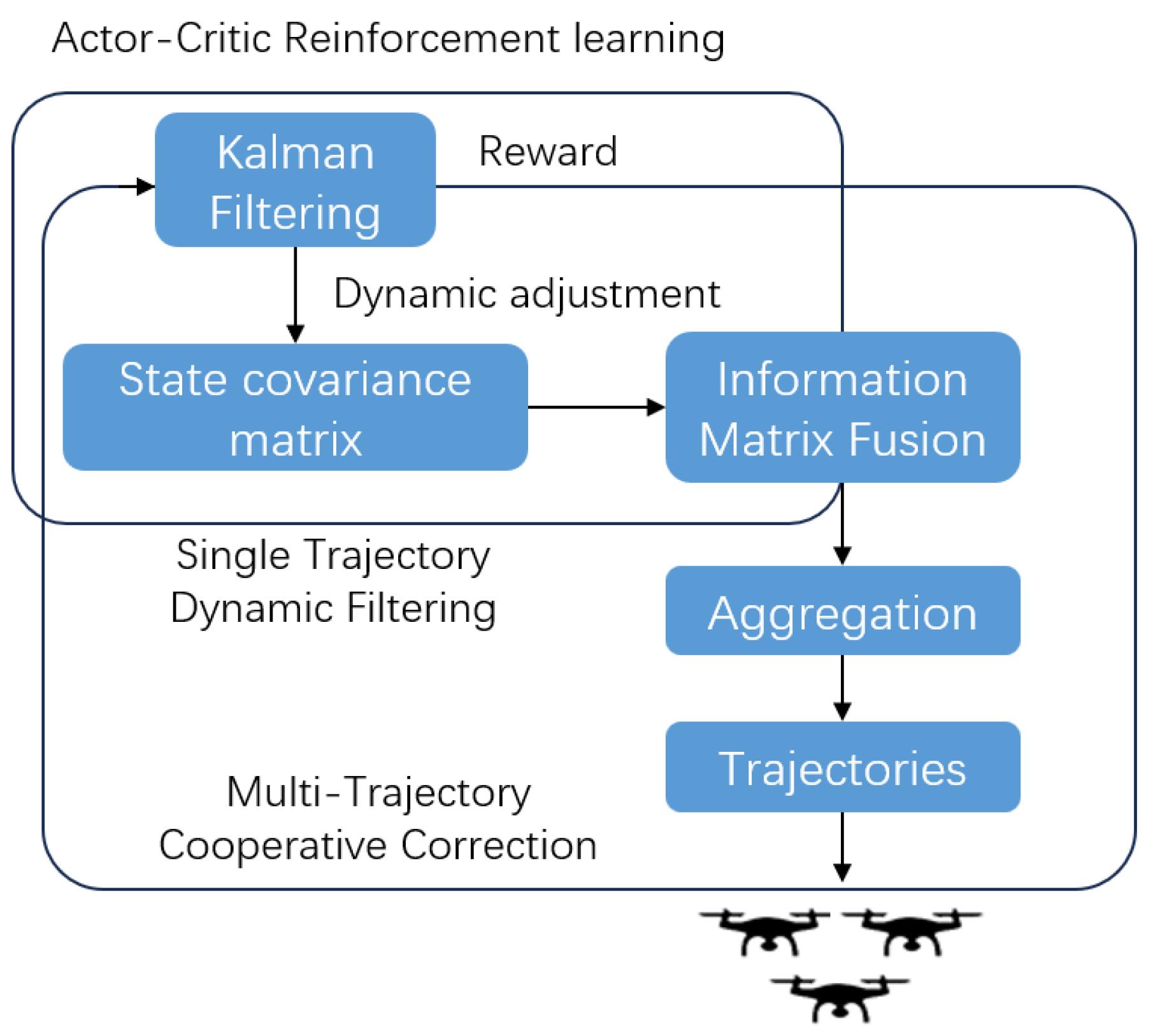

To address the challenges of trajectory parameter uncertainty quantification and dynamic calibration in cooperative localization of UAV swarms, this study proposes a collaborative localization framework that integrates reinforcement learning with information matrix fusion. A dual closed-loop architecture—“single-trajectory dynamic filtering and multi-trajectory cooperative correction”—is adopted (as shown in

Figure 1). First, an Actor-Critic reinforcement learning network is used to adaptively optimize the state covariance matrix in the Kalman filter for each individual trajectory. Then, an information matrix fusion strategy is applied, in which each trajectory’s covariance matrix is transformed into its corresponding information matrix. By aggregating these matrices, the framework fuses the credibility of multi-source trajectory estimates and suppresses error propagation from individual platforms. The overall algorithm consists of two key components: reinforcement learning-driven filter parameter optimization and multi-trajectory information matrix fusion.

3.1. Reinforcement Learning-Driven Filter Parameter Optimization

In the state update process of the Kalman filter, this study employs a reinforcement learning mechanism to dynamically adjust the state covariance matrix.

We first define the system state vector

, including the platform’s position

, velocity

, quaternion

, and acceleration

. The state update follows:

where

and

are the predicted state vector and covariance matrix at time step k+1,

is the process noise with covariance

, and F is the Jacobian of the state transition function

. The Jacobian matrix F of the state transition function

includes the dynamic coupling terms among position, velocity, and acceleration, as well as quaternion updates, where

is an antisymmetric matrix constructed from angular velocity:

The observation model is given by:

where

is the actual measurement and

is the observation matrix.

Then calculate the Kalman gain

, which represents the degree of influence of the observed values on the state update:

Finally, update the state vector based on innovation

and Kalman gain:

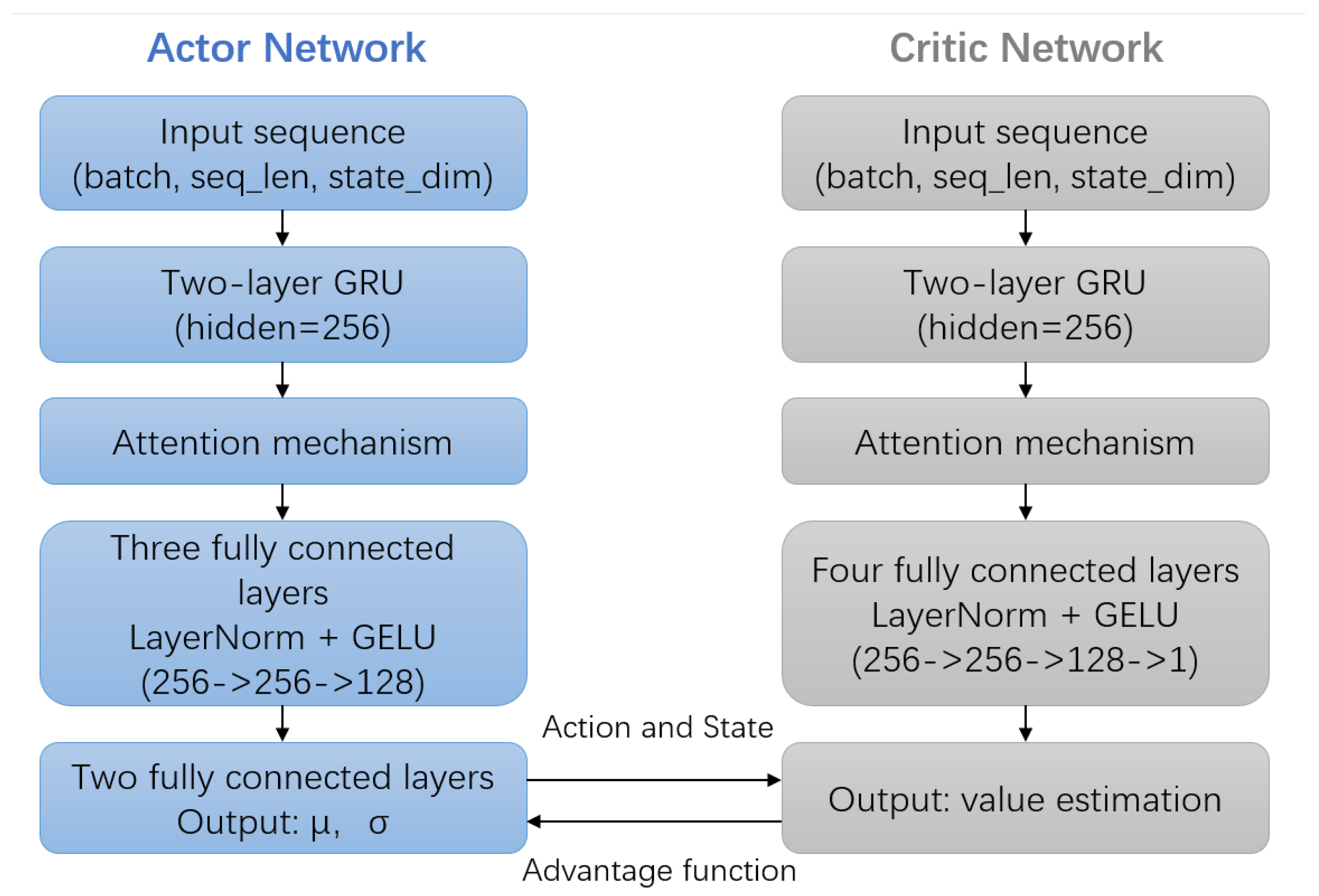

For reinforcement learning modeling, the Actor network employs a two-layer GRU to extract historical state sequences within a sliding window . An attention mechanism is applied to assign weights to key frame features: , . The policy network generates covariance adjustment parameters based on the contextual feature . It outputs the mean and standard deviation through fully connected layers to define a Gaussian distribution , from which an action is sampled. This action is then used to update the state covariance matrix: . The Critic also employs a GRU combined with an attention mechanism to extract temporal features, evaluate the state value V(s), and uses the position error as the reward.

The policy update process optimizes the network parameters using the advantage function, where

is the discount factor:

The parameters of the Actor net are updated using the following gradient:

The parameters of the Critic net are updated by minimizing the mean squared error (MSE):

The overall network architecture is illustrated in

Figure 2 below.

3.2. Multi-Trajectory Information Fusion

At the multi-platform level, to achieve cooperative correction of trajectory information among platforms, this paper proposes a fusion strategy based on the information matrix.

First, for trajectory i, its state covariance matrix is

and the corresponding information matrix is defined as

(in practice, a pseudo-inverse is used to replace the inverse for singular matrices). For the entire UAV swarm, the fused information matrix and state estimate are given by:

Considering the differences in covariance among trajectories, the following method is used to compute the mean in order to avoid distortion:

Using the norm

as a reference threshold, an asymmetric correction mechanism is adopted. For each trajectory i, if its covariance norm

, the trajectory is considered to have high uncertainty. In this case, the fused result is fed back to the original trajectory and updated by weighted averaging:

This enables trajectory estimates with high uncertainty to have their covariance compressed using the fused result, thereby improving overall estimation consistency and system robustness while avoiding the degradation of high-quality estimates.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Setup

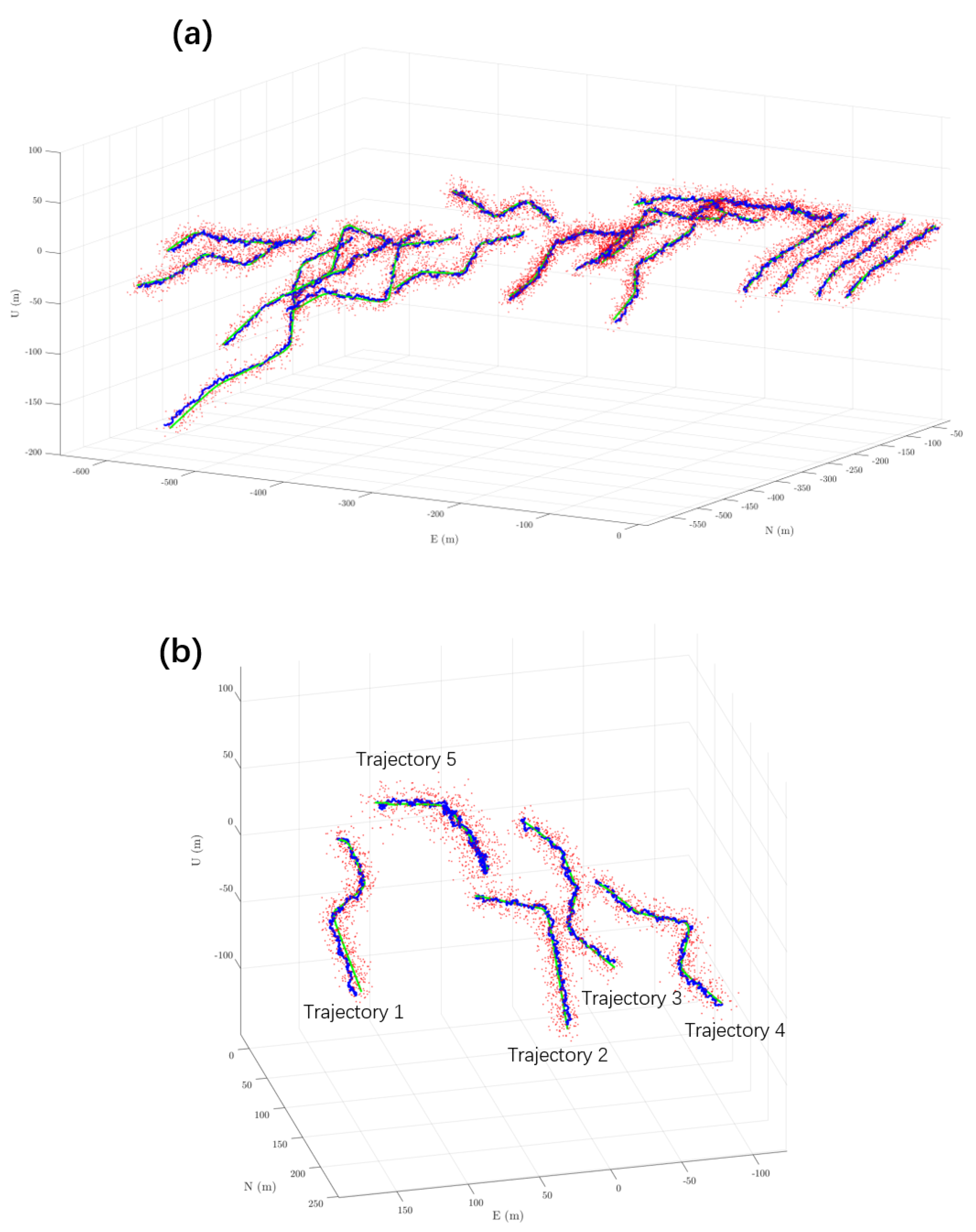

The experiments use the IMU data and GNSS signals generated by the simulation software GNSS-INS-SIM (Version 2.1), which produces IMU data and GPS signals. The dataset is divided into training and testing sets. This software can simulate various motion scenarios including static, uniform motion, and accelerated turns. The training dataset contains 20 trajectories covering multiple dynamic motion patterns; the testing dataset contains 5 independent trajectories not included in training, used to evaluate the algorithm’s generalization capability. Additionally, a set of real data collected by the WTGAHRS3-232 (sourced from WitMotion Shenzhen Co, Ltd, Shenzhen, China.) inertial measurement module is introduced for validation. During algorithm training, the Actor-Critic network uses a batch size of 20, learning rates of 1e-5 for the Actor and 1e-4 for the Critic, and a temporal window length sequence-length=10. The Adam optimizer is used for 20 training epochs. The evaluation metric is the three-dimensional root mean square error (RMSE) of position. The effectiveness of the proposed algorithm is validated by comparing its results with those of the EKF and other methods. The

Figure 3 below shows the 20 training trajectories and 5 testing trajectories. Trajectories 1–4 are simulated data, while trajectory 5 is real data. Red scatter points represent GPS observations, the green curve denotes error-free ground truth, and the blue curve indicates the estimated trajectory.

4.2. Experimental Methods

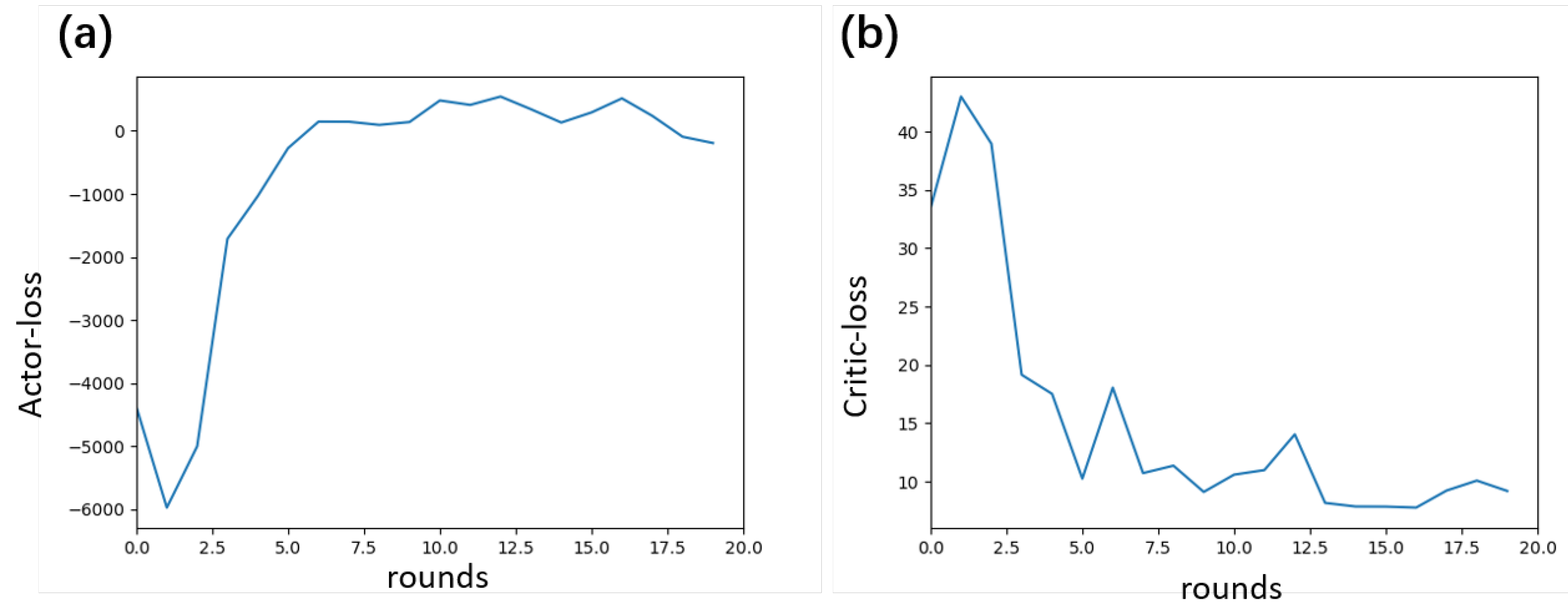

The experiment was conducted through the following steps for model training and testing analysis. During the training phase, simulated data was used to construct state sequences (13 dimensions including position, velocity, quaternion, and acceleration). The Actor-Critic network optimized the dynamic adjustment parameters of the Kalman filter covariance matrix, using the negative position error as the reward function. Training proceeded iteratively until the loss function converged. During testing, the trained model was applied to both simulated and real data to calculate the error between the filtered trajectory positions and the ground truth, and to compare the performance of the proposed method against other filtering methods. The

Figure 4 (a) below shows the actor loss trend during training, which exhibits three distinct stages: initially, due to random parameters and exploratory strategies, the loss fluctuated sharply; subsequently, as the network learned effective strategies, the loss rapidly increased above zero and the parameter adjustment direction became clearer; finally, the loss stabilized around zero with minor fluctuations, indicating ongoing fine-tuning. The

Figure 4(b) critic loss decreased rapidly at first due to large value estimation errors, then fluctuated under data and scenario disturbances, and eventually converged to a low level with small oscillations, reflecting progressively accurate value fitting.

4.3. Experimental Results Evaluation

To evaluate the performance of different filtering methods, this experiment compared the standard EKF, Adaptive Noise-adjusted Kalman Filter (ANKF) [

29], Bidirectional Extended Kalman Filter (BEKF) [

30], and the proposed RL-IMKF, where the number of trajectories M=5 was used for information matrix fusion. The primary comparison metric was the average position error across each trajectory.

Table 1 lists the average position errors for the different filtering methods. The RL-IMKF method demonstrated the lowest error, achieving a 17.4% reduction compared to EKF. This validates that RL-IMKF improves system stability by dynamically generating covariance scaling factors through the Actor-Critic network.

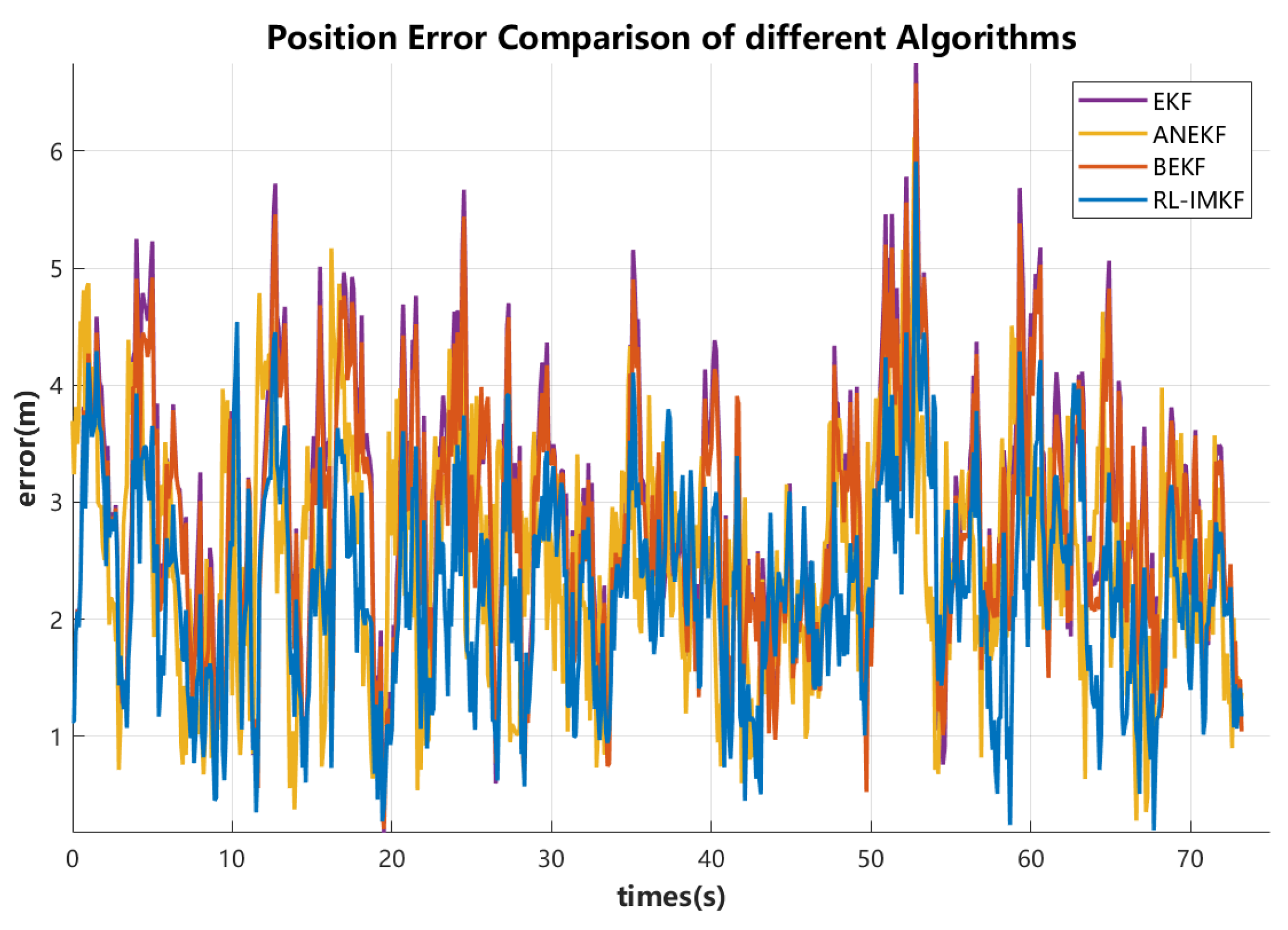

Figure 5 illustrates the positional error trends for the same trajectory under different algorithms. The RL-IMKF shows a smoother overall error curve, with both peak values and fluctuation amplitudes smaller than those of EKF, ANKF, and BEKF, demonstrating a clear advantage in stability.

The experimental results indicate that the standard EKF, due to its use of fixed filtering parameters, is prone to model mismatch in dynamic motion scenarios, resulting in the largest errors. Although ANKF introduces an adaptive noise adjustment mechanism, it relies on predefined noise variation models, limiting its adaptability to complex motion patterns. BEKF improves trajectory smoothness through bidirectional filtering but does not consider the credibility differences among multiple trajectories. In contrast, RL-IMKF dynamically optimizes the state covariance matrix of the Kalman filter through reinforcement learning and combines information matrix fusion to leverage multi-trajectory redundancy. This approach not only enables real-time filter parameter optimization but also suppresses error propagation from abnormal trajectories via the cumulative information matrix mechanism, demonstrating superior performance in both training data fitting and test data generalization.

Additionally, to investigate the impact of the number of trajectories on positioning accuracy in multi-trajectory fusion, this experiment selecting trajectory 1 compared the single-trajectory position errors of IMKF with trajectory counts M ranging from 1 to 5. The results are shown in

Table 2.

It can be seen that when only a small number of trajectories are fused, the improvement in positioning accuracy is not significant, and error fluctuations may occur due to information redundancy; however, as the number of trajectories increases, the complementary information among multiple trajectories gradually dominates, resulting in a significant decrease in positioning error with the increase in the number of trajectories.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes a Kalman filter localization calibration method based on RL-IMKF, effectively addressing the robustness issue of filter model parameters in dynamic positioning of unmanned clusters. The constructed Actor-Critic network captures temporal features using GRU and attention mechanisms to dynamically generate covariance adjustment factors. Simultaneously, a multi-trajectory information matrix fusion algorithm is designed to aggregate the inverse of trajectory covariance matrices, quantify uncertainty, suppress error propagation, and improve the utilization of multi-source data. Experimental results demonstrate that RL-IMKF achieves the lowest average position error on both training and testing datasets, significantly reducing errors by 17.4% compared to traditional methods such as EKF. Regarding error variation trends, the RL-IMKF error curve is smoother, with peak values and fluctuation amplitudes noticeably smaller than those of other comparative algorithms. Furthermore, a dedicated experiment on the impact of the number of fused trajectories on positioning accuracy shows that reasonably increasing the number of fused trajectories leverages complementary information to reduce errors, providing valuable insights for practical engineering applications.

In practical applications, the RL-IMKF method demonstrates significant potential for adaptation to diverse scenarios. Whether deployed in intelligent unmanned system clusters with stringent environmental perception requirements or in complex environments affected by signal interference and data noise, this method achieves high-precision localization calibration through dynamic optimization of filter parameters and fusion of multi-source trajectory information. From transportation and logistics to monitoring and reconnaissance, RL-IMKF can enhance the reliability and cooperation of unmanned device positioning, facilitating broader and more effective deployment of unmanned systems across multiple fields.

In summary, the RL-IMKF method offers a new approach for high-precision positioning of unmanned clusters. Its strong performance in both theoretical validation and experimental testing provides technical support for the widespread application of intelligent unmanned systems in military, civilian, and other fields. Although this study has achieved significant progress, there remains room for optimization and further development. Future work could explore integrating multi-source heterogeneous sensor data such as UWB, vision, and LiDAR into the algorithm framework, and improve the design of the reinforcement learning state space and information matrix fusion strategies to enable multimodal data collaboration in more complex environments. Additionally, considering the dynamic changes in communication topology during unmanned cluster movement, researching algorithms based on graph neural networks for trajectory association and dynamic fusion will also be a crucial direction to enhance algorithm adaptability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Zijia Huang and Qiushi Xu; Methodology, Qiushi Xu and Menghao Sun; Software, Qiushi Xu and Menghao Sun; Validation, Zijia Huang and Xuzhen Zhu; Formal analysis, Zijia Huang; Investigation, Menghao Sun and Xuzhen Zhu; Resources, Xuzhen Zhu; Data curation, Xuzhen Zhu; Writing—original draft preparation, Zijia Huang and Qiushi Xu; Writing—review and editing, Xuzhen Zhu; Visualization, Menghao Sun; Supervision, Xuzhen Zhu; Project administration, Xuzhen Zhu; Funding acquisition, Zijia Huang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Laboratory of Multi-domain Data Collaborative Processing and Control under the Open Fund project MDPC20240103.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the National Key Laboratory of Multi-domain Data Collaborative Processing and Control for its support and funding. This support has been instrumental in facilitating this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- P. M. C. Pereira, H. D. M. da Silva, and C. M. G. S. Lima, “Advancements in multipath mitigation for gnss receivers: Review of channel estimation techniques,” Space: Science & Technology, vol. 5, p. 0278, 2025. https://spj.science.org/doi/abs/10.34133/space.0278.

- W. Chen, C. Zhang, Y. Peng, Y. Yao, M. Cai, and D. Dong, “Enhancing gnss positioning in urban canyon areas via a modified design matrix approach,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 10 252–10 265, 2024. [CrossRef]

- K. R. Pai and N. Marakala, “A review on inertial navigational systems,” in 2016 International Conference on Electrical, Electronics, and Optimization Techniques (ICEEOT), 2016, pp. 1682–1686. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Kalman, “A new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems,” Transactions of the ASME–Journal of Basic Engineering, vol. 82, no. Series D, pp. 35–45, 1960.

- A. U. Alsaggaf, M. Saberi, T. Berry, and D. Ebeigbe, “Nonlinear kalman filtering in the absence of direct functional relationships between measurement and state,” IEEE Control Systems Letters, vol. 8, pp. 2865–2870, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. P. Lillicrap, J. J. Hunt, A. Pritzel, N. Heess, T. Erez, Y. Tassa, D. Silver, and D. Wierstra, “Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning,” 2019. https://arxiv.org/abs/1509.02971.

- R. S. Sutton, D. McAllester, S. Singh, and Y. Mansour, “Policy gradient methods for reinforcement learning with function approximation,” in Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, ser. NIPS’99. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 1999, p. 1057–1063.

- J. Chung, C. Gulcehre, K. Cho, and Y. Bengio, “Empirical evaluation of gated recurrent neural networks on sequence modeling,” 2014. [Online]. https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.3555.

- Z. Niu, G. Zhong, and H. Yu, “A review on the attention mechanism of deep learning,” Neurocomputing, vol. 452, pp. 48–62, 2021. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- M. A. K. Jaradat and M. F. Abdel-Hafez, “Enhanced, delay dependent, intelligent fusion for ins/gps navigation system,” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 1545–1554, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. X. D. D. Shaojie NI, Shiyang LI, “Overview of gnss/ins ultra-tight integrated navigation,” Journal of National University of Defense Technology, vol. 45, no. 5, pp. 48–59, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao and Z. Wang, “Motion measurement using inertial sensors, ultrasonic sensors, and magnetometers with extended kalman filter for data fusion,” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 943–953, 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. Kou and A. Haggenmiller, “Extended kalman filter state estimation for autonomous competition robots,” Journal of Student Research, vol. 12, no. 1, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Wan and R. Van Der Merwe, “The unscented kalman filter for nonlinear estimation,” in Proceedings of the IEEE 2000 Adaptive Systems for Signal Processing, Communications, and Control Symposium (Cat. No.00EX373), 2000, pp. 153–158. [CrossRef]

- J. Luo, Z. Wang, Y. Chen, M. Wu, and Y. Yang, “An improved unscented particle filter approach for multi-sensor fusion target tracking,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 23, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, Y. Zhang, B. Xu, Z. Wu, and J. A. Chambers, “A new adaptive extended kalman filter for cooperative localization,” IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, vol. 54, no. 1, pp. 353–368, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, X. Zhou, C. Wang, W. Zhao, G. Wu, T. Jiang, and M. Wang, “Adaptive robust federal kalman filter for multisensor fusion positioning systems of intelligent vehicles,” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 24, no. 10, pp. 17 269–17 281, 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Cohen and I. Klein, “Inertial navigation meets deep learning: A survey of current trends and future directions,” Results in Engineering, vol. 24, p. 103565, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D.-J. Jwo, A. Biswal, and I. A. Mir, “Artificial neural networks for navigation systems: A review of recent research,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 7, 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Wei, J. Li, K. Feng, D. Zhang, P. Li, L. Zhao, and Y. Jiao, “A mixed optimization method based on adaptive kalman filter and wavelet neural network for ins/gps during gps outages,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 47 875–47 886, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, K. Li, Q. Fu, and L. Yuan, “Research on integrated navigation algorithm based on radial basis function neural network,” Journal of Physics: Conference Series, vol. 1961, p. 012031, 07 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, M. Mikhaylov, N. Mikhaylov, and T. Pany, “Deep learning based kalman filter for gnss/ins integration: Neural network architecture and feature selection,” in 2023 International Conference on Localization and GNSS (ICL-GNSS), 2023, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- S. Hochreiter and J. Schmidhuber, “Long short-term memory,” Neural Computation, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1735–1780, 1997. [CrossRef]

- K. O’Shea and R. Nash, “An introduction to convolutional neural networks,” 2015. https://arxiv.org/abs/1511.08458.

- X. Gao, H. Luo, B. Ning, F. Zhao, L. Bao, Y. Gong, Y. Xiao, and J. Jiang, “Rl-akf: An adaptive kalman filter navigation algorithm based on reinforcement learning for ground vehicles,” Remote Sensing, vol. 12, no. 11, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Han, C. Wei, R. Li, J. Wang, and H. Yu, “A novel cooperative localization method based on imu and uwb,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 2, 2020. [CrossRef]

- X. Kang, D. Wang, Y. Shao, M. Ma, and T. Zhang, “An efficient hybrid multi-station tdoa and single-station aoa localization method,” Trans. Wireless. Comm., vol. 22, no. 8, p. 5657–5670, Aug. 2023. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- T. Qin, P. Li, and S. Shen, “Vins-mono: A robust and versatile monocular visual-inertial state estimator,” IEEE Transactions on Robotics, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 1004–1020, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Vettori, E. Di Lorenzo, B. Peeters, M. Luczak, and E. Chatzi, “An adaptive-noise augmented kalman filter approach for input-state estimation in structural dynamics,” Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, vol. 184, p. 109654, 2023. [Online]. [CrossRef]

- Y. Dong, K. Kwan, and T. Arslan, “Enhanced pedestrian trajectory reconstruction using bidirectional extended kalman filter and automatic refinement,” in 2024 14th International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN), 2024, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).