1. Introduction

Uranium dioxide (UO

2) is widely used as a nuclear fuel in reactors due to its high melting point (~2800 °C), excellent chemical stability, superior radiation resistance, and good compatibility with coolants[

1]. However, UO

2 suffers from low thermal conductivity, as a ceramic fuel, around 8~10 W/(mK) at room temperature[

2]. During reactor operation, neutron irradiation induces point defects (e.g., vacancy-interstitial pairs), which sink into dislocation loops and stacking faults. Concurrently, the fission of

235U generates solid fission products (e.g., Mo, Ru, Ba) that precipitate as metals or metal oxides, as well as gaseous fission products (e.g., Xe, Kr) dispersed within the UO

2 matrix[

3,

4]. These irradiation-induced defects and fission products cause lattice distortion and stress concentration, disrupting translational symmetry and periodicity of lattice, thereby acting as scattering centers for phonon-mediated heat transport. Since UO

2 is a Mott insulator[

5], heat conducts primarily through phonons, and radiation defects as well as solid/gaseous fission products scatter phonons, reducing the phonon mean free path (MFP). The scattering intensity is proportional to the fourth power of the phonon frequency. Furthermore, as burnup increases, the accumulation of fission products leads to the formation of a "high burnup structure" (HBS), which enhances phonon scattering and introduces thermal resistance phases (e.g., bubbles), which significantly degrade thermal conductivity of UO

2[

6]. This results high temperature gradients within the fuel, causing the risks of pellets melting, fission gas release, and fuel swelling. Therefore, accurately predicting the thermal conductivity of irradiated UO

2 is crucial for reactor safety design and fuel performance optimization.

Thermal transport in nuclear fuels has been extensively investigated through experiments and theoretical calculations. Martin et al. [

7] measured the thermal diffusivity

, heat capacity (

), and density

of UO

2 with non-stoichemistric ratio and porosities. They fitted the empirical thermal conductivity formula with measured data using a first-order phonon scattering model

, correlating parameters A, B and T with phonon-defect, phonon-phonon scattering, and temperature respectively, laying the foundation for further experimental research. Minato et al.[

8] employed the laser flash method to measure the thermal conductivity of disk-shaped UO

2 and (U,Gd)O

2 samples, demonstrating that irradiation-induced point defects significantly reduce the thermal conductivity of UO

2. Philipponneau et al.[

9] experimentally measured the thermal conductivity of (U,Pu)O

2-x mixed oxide (MOX) fuels with non-stoichiometry and porosity and established a new empirical formula. Ronchi et al.[

10] extended Martins model by incorporating irradiation effects, developing a unified empirical formula that describes both pristine and irradiated UO

2 thermal conductivity. Their model provides precise expressions for parameter A (as a function of irradiation temperature) and parameter B (as a function of burnup), enabling accurate predictions the thermal conductivity of UO

2.

Despite these advances, experimental measurements of irradiated UO

2 thermal conductivity remain challenging, particularly at high temperatures, due to complex procedures and safety risks[

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Theoretically, first-principles calculations combined with Slack theory[

15], Callaway model[

16,

17], or the phonon Boltzmann transport equation(BTE) can predict thermal conductivity, while molecular dynamics(MD)[

18,

19,

20] simulations—though limited by potential accuracy—offer complementary insights. Currently, irradiated UO

2 thermal conductivity is primarily determined experimentally, with empirical models used to establish quantitative relationships with defect concentrations. However, the mechanisms by which point defects, fission products, dislocations, and grain boundaries affect thermal conductivity are not yet fully addressed. Although significant efforts have been made in multiscale modeling and experimental characterization, challenges persist in developing predictive models and advanced experimental tools.

In this work, we employ first-principles calculations combined with the phonon BTE to investigate the thermal conductivity of UO2 contained fission products and irradiation defects. This paper is organized as follows: 1) Introduce the thermal conductivity theory and the methods used to calculation; 2) Calculate and analysis of the electronic structure and phonon spectrum of UO2; 3) Calculate thermal conductivity of UO2 and discuss of the effects of fission products and irradiation defects; 4) Summary and conclusions.

2. Theory and Methods

2.1. Theory of thermal conductivity

In isolator the thermal transport crystalline materials is primarily governed by quantized lattice vibrations known as phonons[

21]. The thermal contribution of a phonon with frequency

is determined by three fundamental parameters[

22]: (1) the phonon heat capacity

, (2) the group velocity

, and (3) the phonon lifetime

. The accurate determination of lattice thermal conductivity requires solving the phonon Boltzmann Transport Equation under non-equilibrium conditions. According to lattice dynamics calculations, we can calculate the phonon mode frequencies

, which phonon population follows Bose-Einstein statistics under equilibriation:

, where

represents the Boltzmann constant. When the lattice is subjected to a temperature gradient

, the phonon distribution deviates from equilibrium (

), establishing a phonon flux from higher to lower temperature regions. The steady-state distribution is described by the BTE[

23]:

where the left term corresponds to the drift component induced by

, and the right term accounts for various scattering processes. Here,

denotes the group velocity component along direction

. Within the relaxation time approximation(RTA), the lattice thermal conductivity tensor is expressed as:

The total relaxation time

total combines all scattering mechanisms through Matthiessen’s rule:

Cumulative thermal conductivity

and thermal conductivity

with respect to frequency are defined by

The three-phonon scattering rate is calculated using Fermi’s golden rule[

24]:

where

represents the third-order anharmonic coupling matrix elements. For defect scattering, we employ the generalized Tamura model[

25]:

where

is the unit cell volume,

is the average group velocity, and

is the scattering strength parameter[

14,

26,

27]:

Here,

denotes the concentration of defect type

i,

and

represent the mass difference and average mass,

and

represent the force constants difference and average force constants, while

and

correspond to the radius difference and average radius, the Grüneisen parameter

characterizes the volume dependence of phonon frequencies,respectively. The parameter Q, which is 4.2 for vacancies and 3.2 for substitutional defects in fluorite structures[

28], accounts for nearest-neighbor bond distortion. The force constant variation is typically proportional to volume, merging the combination of force-constant and radius-variation terms, as follow Equation

9.

The dimensionless parameter

(typically ranging 0-500) is determined through empirical fitting. We consider three distinct defect scattering regimes[

29]: a)Mass-only defects (e.g., isotopic impurities): Only the mass variance term in Equation

8 contributes significantly; b)Substitutional impurities (e.g., Mo in UO

2): Both mass and volume terms are relevant, with possible bond modification; c)Vacancies/interstitials: All terms contribute substantially, including significant force constant modifications. For noble gas atoms (Xe, Kr) that do not form chemical bonds with the matrix, the scattering is dominated by mass and volume effects without substantial force constant contributions. This comprehensive treatment enables accurate modeling of phonon scattering by various defect types in nuclear fuel materials.

2.2. Methods

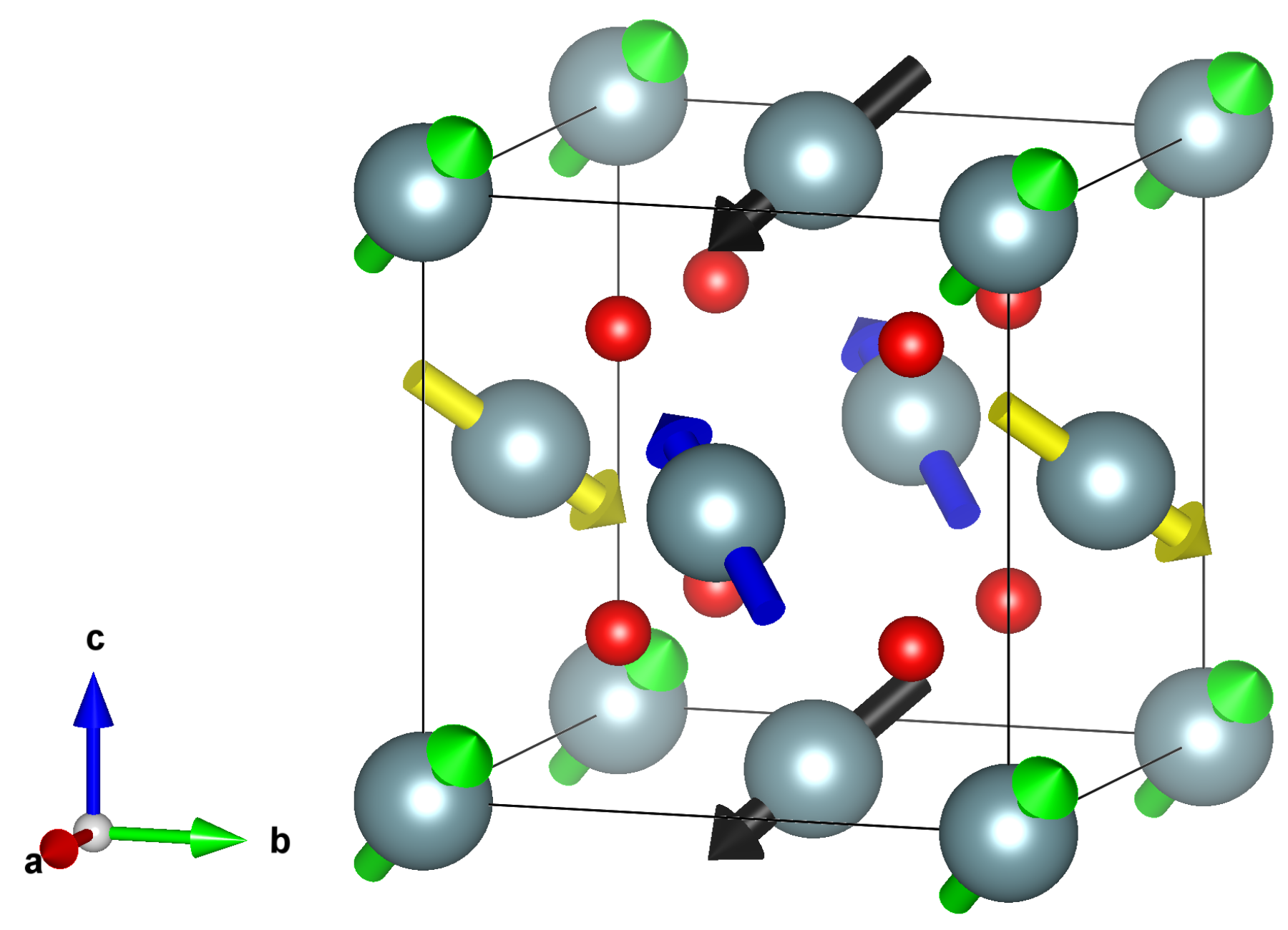

First-principles calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) within the framework of density functional theory(DFT)[

30]. The projector augmented wave (PAW) method[

31] was employed to describe the electron-ion interactions, and the exchange-correlation functional was treated with the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof(PBE) formulation[

32]. To properly account for the strong electron correlations in UO

2, the Hubbard U correction(DFT+U)[

33] was applied, including spin-orbit coupling(SOC) to improve the accuracy of the electronic structure. The initial structure of UO

2 was modeled using a conventional unit cell (containing 4 U and 8 O atoms), as shown in

Figure 1, and a 2×2×2 supercell (96 atoms) was constructed with the 3k antiferromagnetic (AFM) ordering[

34] along the a, b, and c axes. The plane-wave cutoff energy was set to 450 eV, and a 3×3×3 Monkhorst-Pack k-point mesh was used for Brillouin zone sampling and the total energy convergence criterion was set to 10

-6 eV. Structural optimization was performed under zero external pressure to obtain the equilibrium lattice parameters. The f-orbital occupation matrix control(OMC) method[

35] was adopted, to avoid metastable states and accelerate iterative convergence.

Subsequently, the Born effective charges and dielectric constant tensor of UO

2 were calculated by density functional perturbation theory(DFPT)[

36]. To accurately describe the lattice dynamics, second- and third-order interatomic force constants (IFCs) were calculated using the finite displacement method as implemented in the Phonopy[

37] and Phono3py[

38] codes with atomic displacements of 0.03 Å in supercell, and the long-range Coulomb interactions in ionic crystal of UO

2 (U

4+ and O

2-) were corrected by introducing non-analytical term corrections(NAC)[

39]. Finally, the lattice thermal conductivity (

) of UO

2 was computed by solving the Boltzmann transport equation within the relaxation time approximation. A 19×19×19 q-point mesh was used for Brillouin zone integration, and the tetrahedron method was applied to improve numerical accuracy. Symmetry operations were utilized to reduce computational costs while maintaining high precision.

3. Results and Discussions

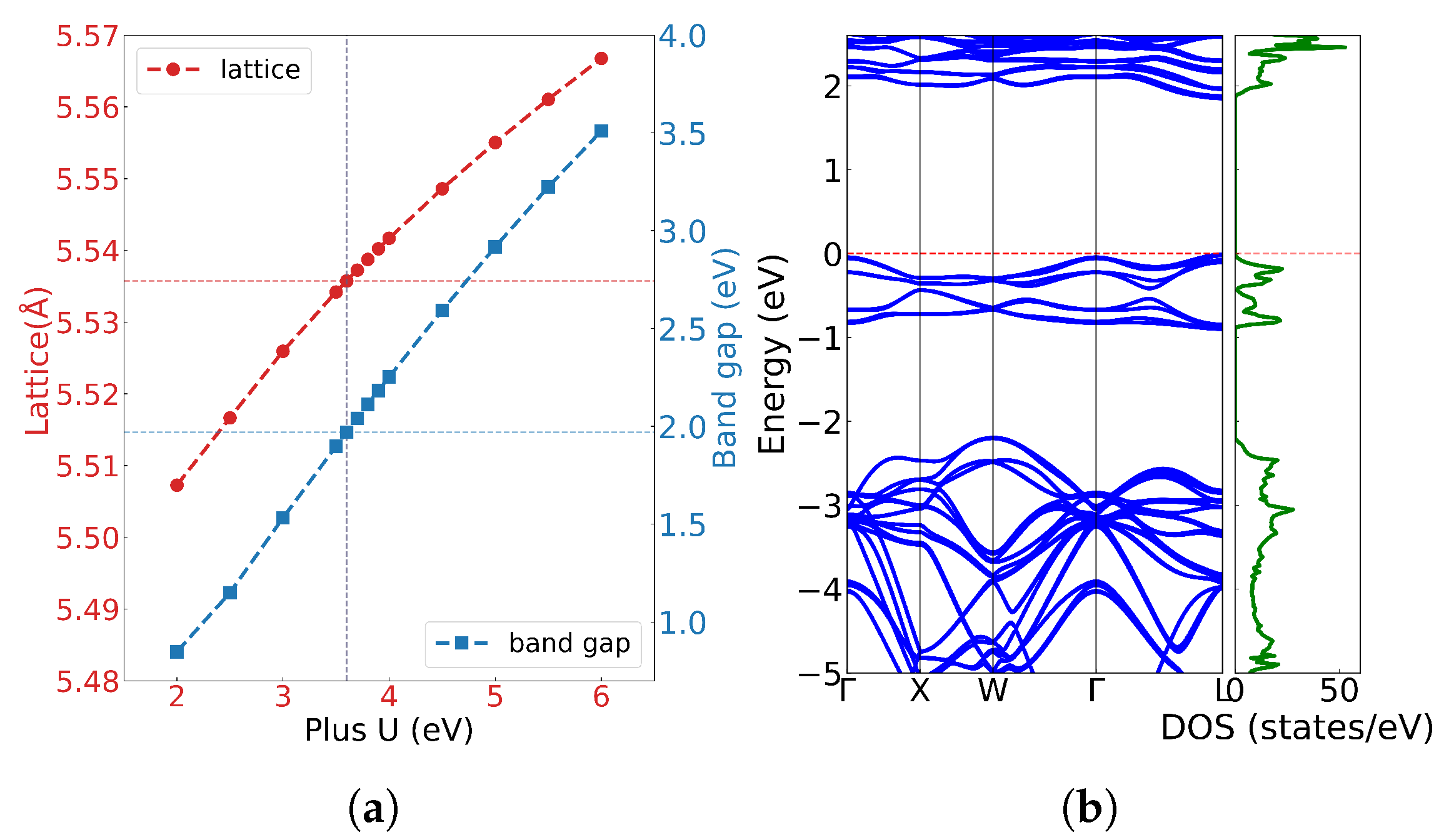

3.1. Electronic Structure

First-principles calculations provide fundamental insights into the electronic structure of uranium dioxide with Hubbard U correction solve the strong localization problem of 5f electrons in UO

2.

Figure 2(a) illustrates the lattice constants and bandgap (

) as functions of the Hubbard U under spin-orbit coupling. Both the lattice constant and bandgap increase nearly linearly with U values, consistent with previous calculations by Dorado et al. Experimentally, UO

2 exhibits a lattice constant of a= c = 5.47 Å, and the bandgap is approximately 2.0 eV. By comparing our results with experimental bandgap, we selected U = 3.6 eV and J = 0.0 eV, yielding a bandgap of 1.990 eV, in excellent agreement with the experimental value of 2.0 eV, accurately reproduce the electronic structure of UO

2. As shown in

Figure 2(b), the calculated band structure and density of state reveals that the valence band maximum and conduction band minimum primarily derived from U 5f and O 2p orbitals.

For U = 3.6 eV and J = 0.0 eV, the calculated lattice constant a = 5.536 Å, comparaing previous studies shows consistency, Dorado et al.[

35] employed U = 4.50 eV and J = 0.51 eV based on experimental elastic constants, obtaining a = 5.56 Å and c = 5.50 Å, noting the symmetry breaking(

) of UO

2. A similar c axis contraction was observed by Iwasawa et al.[

40], attributed to spin alignment in the antiferromagnetic (AFM) state, where U atoms with opposite magnetic moments move closer along the Oz axis. Pegg et al.[

41] used the PBE functional with U = 3.35 eV and J = 0.0 eV, finding that the magnetic moment was insensitive to U or J, while the lattice constant (a = 5.474 Å) remained slightly overestimated. These results confirm that the PBE functional with Hubbard U correction provides an accurate electronic structure but tends to overestimate lattice parameters. These computational results conclusively demonstrate that UO

2 exhibits Mott insulating behavior, with valence electrons strongly localized around lattice atoms. This electronic configuration leads to negligible contributions from electronic thermal conductivity (

), making lattice vibrations (phonons) the dominant heat carriers in UO

2.

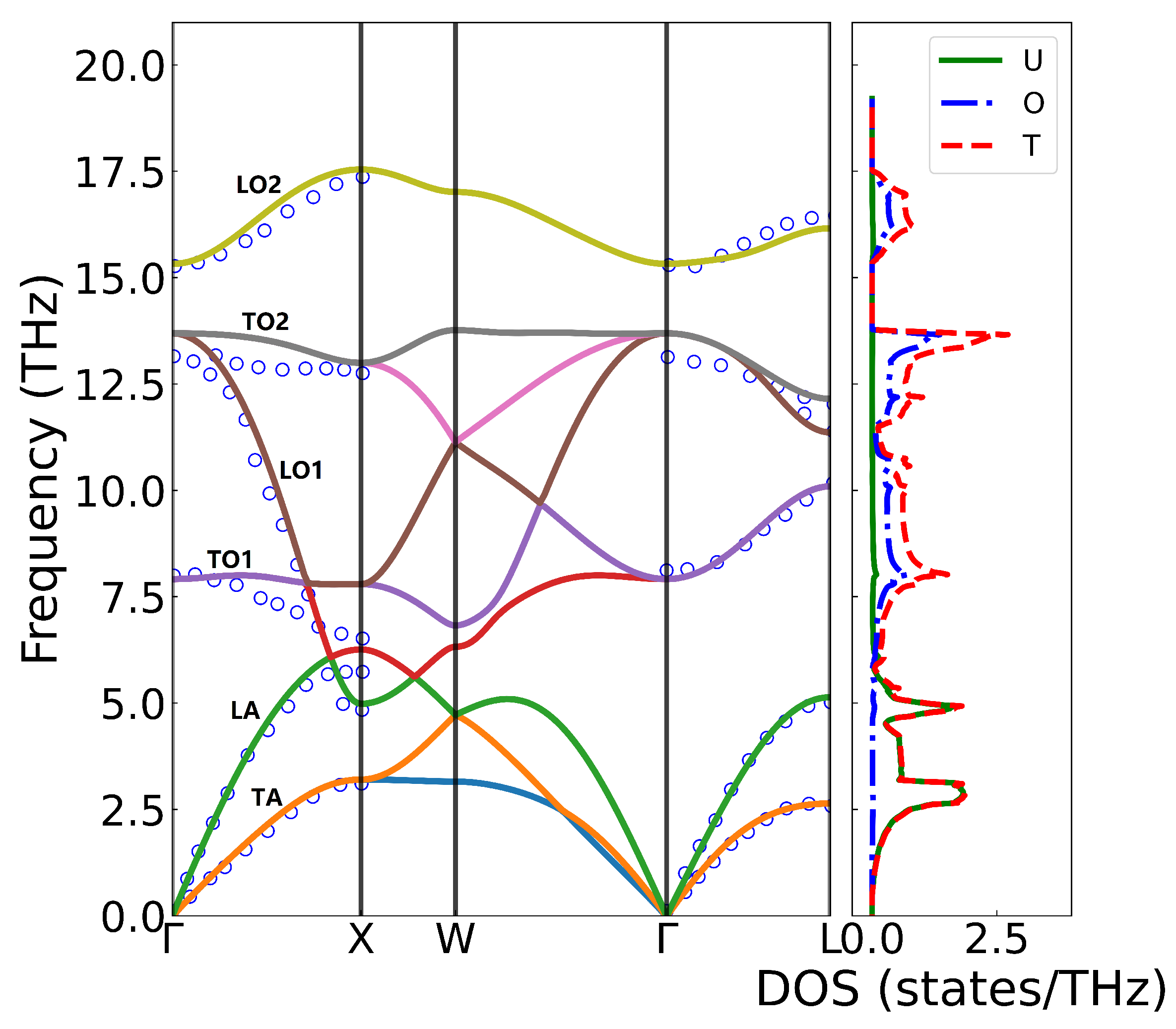

3.2. Phonon Spectrum

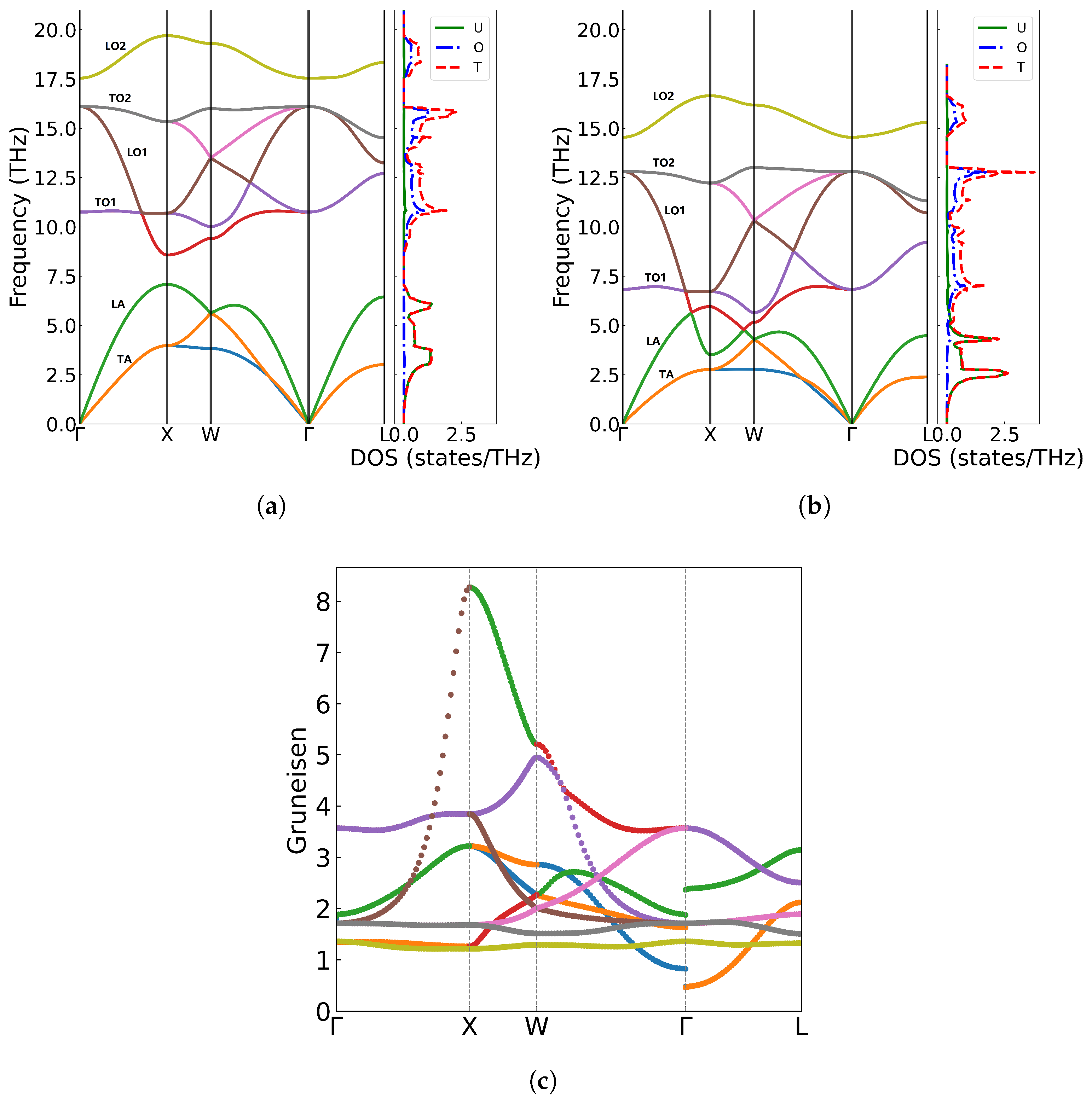

The phonon spectrum and density of states of UO

2 were investigated using first-principles calculations and compared with experimental data from inelastic neutron scattering measurements at 296K[

42,

43], as shown in

Figure 3. UO

2 crystallizes in the fluorite structure (Fm3-m), with a primitive cell containing one uranium atom and two inequivalent oxygen atoms, giving rise to nine phonon branches—three acoustic (TA/LA) and six optical (TO/LO). The calculated phonon dispersion along the high-symmetry

-X-W-

-L path agrees well with experimental results, except for the TO2 branch near the

point, where the computed frequencies are slightly higher, likely due to the absence of temperature effects in the 0 K simulations. The acoustic modes, dominated by uranium vibrations, appear at low frequencies, while the optical branches, primarily associated with oxygen motion, exhibit higher frequencies. Notably, longitudinal optical (LO2) and transverse optical (TO2) phonon branches split at the

point due to the long-range Coulomb interaction, which was accounted for by incorporating non-analytical term corrections in the dynamical matrix. The static dielectric tensor yielded a diagonal element of 5.4512, and the Born effective charges were calculated as

and

, indicating significant charge transfer and partial covalent character.

The maximum phonon frequency in the figure occurs at the X-point with a value of 17.54 THz. Near the -point, with the exception of the TO2 branch, the calculated phonon frequencies show excellent agreement with experimental measurements. Along the -X high-symmetry path, slight discrepancies exist between calculated and experimentally measured phonon frequencies, where the calculated values are higher than experimental data. This difference may arise because the experimental measurements were performed at 296 K while calculations correspond to 0 K conditions, as temperature increase typically leads to phonon frequency softening. For the LA and TA branches, the calculated values match well with experimental measurements, though minor differences appear at the boundary X-point. No direct comparison was made for frequencies between the X and W points due to differing paths taken in experimental measurements versus calculations. Along the -L path, the calculations and experimental results show good agreement. However, a relatively larger deviation is observed for the highest-frequency optical branch (TO2), which may be attributed to greater experimental uncertainties in measuring high-frequency optical modes.

The phonon frequencies exhibit a strong dependence on lattice parameter variations, as shown in

Figure 4(a)(b). Using the equilibrium lattice constant a = 5.536 Å as reference, Under compression (a = 5.50 Å), phonon hardening occurs, with the maximum frequency increasing to 19.698 THz at the X point, accompanied by a widening gap between the LA and TO1 branches[

44,

45,

46]. Conversely, lattice expansion (a = 5.540 Å) leads to phonon softening, reducing the highest frequency to 16.648 THz and causing the LA and TO1 branchs to overlap. The phonon frequency shifts caused by volume variations in UO

2 originate from the anharmonic nature of interatomic potentials. Our calculations reveal distinct phonon hardening under compression (a = 5.50 Å) and softening under expansion (a = 5.540 Å), demonstrating the significant role of lattice anharmonicity in governing vibrational properties. To quantitatively characterize these effects, we computed the Grüneisen parameters (

) along high-symmetry directions with the formula

. The resulting Grüneisen parameters shown in

Figure 4(c) exhibit notable branch dependence, with an average value of 1.86 that shows consistency with both theoretical[

47] (1.88 from PBE+U calculations) and experimental (1.6-2.2) vaules.

3.3. Thermal Conducitivity

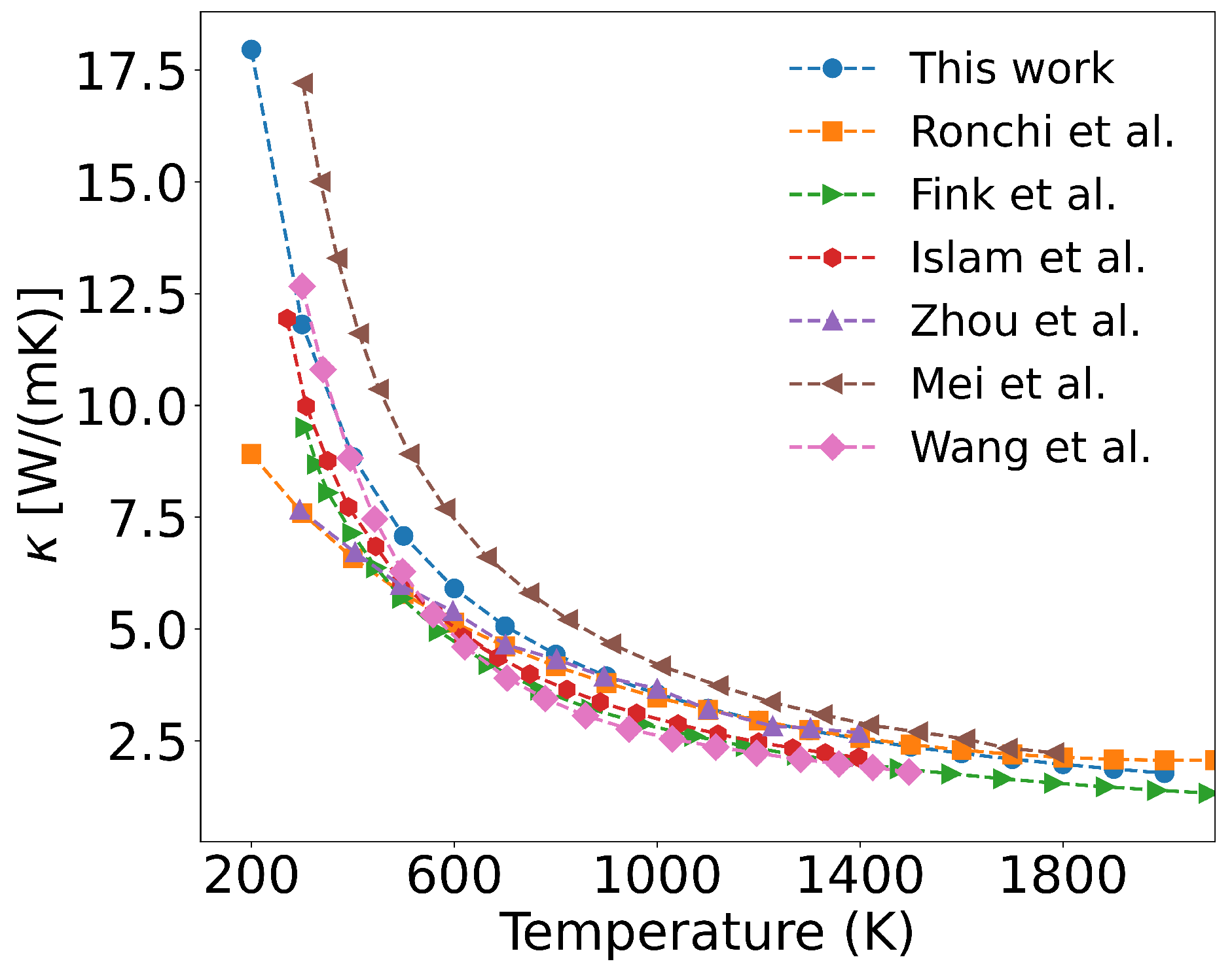

3.3.1. Pristine UO2

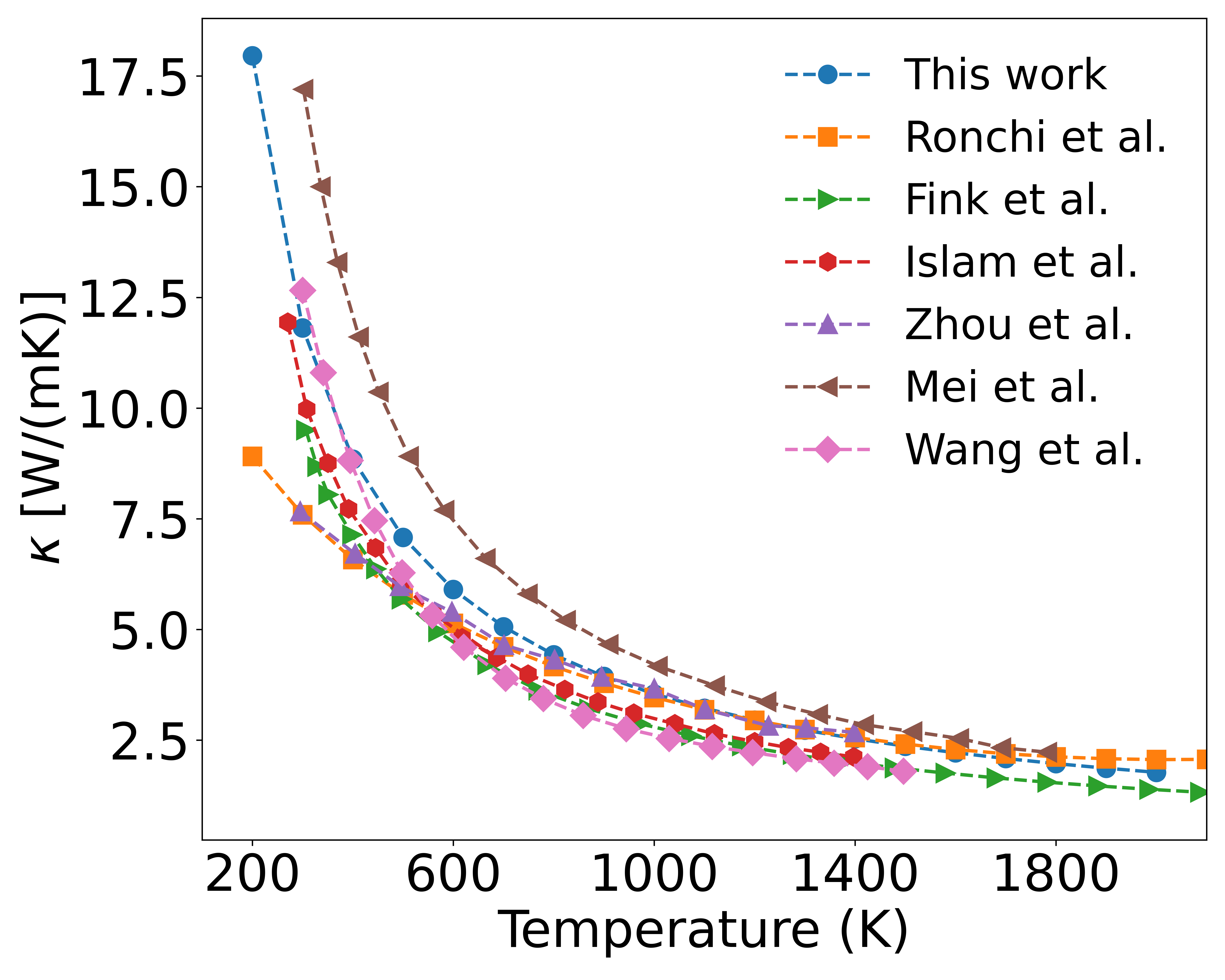

The thermal conductivity of unirradiated UO

2 single crystals, calculated using first-principles atomic simulations combined with the Boltzmann transport equation for phonon distribution functions, is shown in

Figure 5. Since the UO

2 single crystal contains no defects, its thermal conductivity is primarily governed by three-phonon scattering. As observed in the figure, the thermal conductivity gradually decreases with increasing temperature. At low temperatures (e.g., 300 K), lattice vibrations remain close to equilibrium positions, satisfying the harmonic approximation well. Under these conditions, different phonon modes are nearly independent, and phonon-phonon scattering is weak, resulting in high thermal conductivity (11.813 W/(m·K) at 300 K). As temperature rises, atomic vibrations deviate further from equilibrium, and the interatomic potential becomes asymmetric, breaking the independence of phonon modes. This leads to enhanced phonon scattering, such as the merging of two phonons into one or the decay of one phonon into two. Three-phonon scattering includes Normal (N) processes and Umklapp (U) processes. While N processes only redistribute phonon momentum without affecting thermal conductivity, U processes cause significant momentum reversal, increasing phonon scattering and reducing the mean free path. Consequently, thermal conductivity drops sharply at high temperatures (e.g., 1.970 W/(m·K) at 1800 K).

Figure 5 shows the calculated thermal conductivity of a perfect UO

2 crystal considering only three-phonon scattering. The results exhibit a consistent overall trend with reported computational and experimental values. However, the experimentally measured thermal conductivity of UO

2 at the same temperatures is lower than our calculated values. Ronchi[

48], Fink[

49], and others experimentally determined the thermal diffusivity, heat capacity, and density of UO

2, from which they derived empirical formulas for thermal conductivity. As shown in

Figure 5, the experimental values are significantly higher than our calculations in the 200–600 K range. This discrepancy arises because the real UO

2 samples used in experiments contain impurities and defects (e.g., vacancies, grain boundaries, and surfaces). At lower temperatures, these defects scatter phonons, leading to a reduced thermal conductivity in real UO

2 samples compared to that of a perfect single crystal. A detailed analysis of this effect will be presented later.

Regarding computational studies of UO

2 thermal conductivity, Islam[

50] and Wang[

15] employed Slack empirical model, calculating the Debye temperature and Grüneisen parameter to estimate thermal conductivity. Their results, as shown in the

Figure 5, agree well with our calculations. However, this model cannot account for the thermal conductivity of defective UO

2. Zhou[

51] used first-principles calculations combined with the Wigner transport equation and experimental measurements of phonon linewidths, incorporating thermal expansion effects. Their computed thermal conductivity was lower and closer to experimental values. In contrast, Mei[

52] applied the Callaway model with relaxation time approximation and added a phonon momentum conservation term, resulting in a thermal conductivity overestimation compared to experiments, as illustrated in

Figure 5.

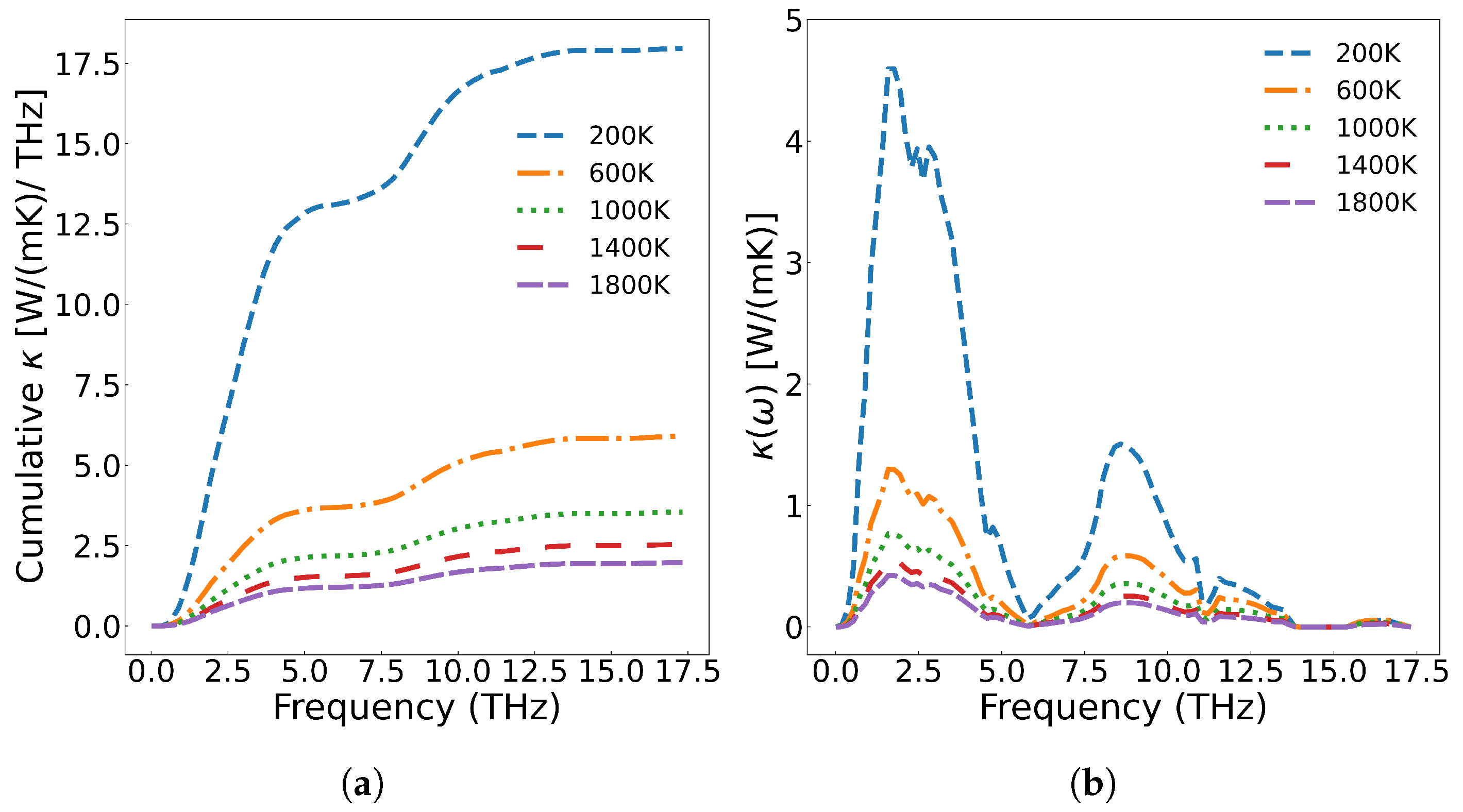

The frequency-dependent contributions to thermal conductivity are analyzed in

Figure 6(a), which shows the cumulative thermal conductivity as a function of phonon frequency. When the phonon frequency is below 5 THz, the cumulative thermal conductivity increases most rapidly. The increase becomes slower in the 5-14 THz range, and for frequencies above 14 THz, the thermal conductivity shows no further increase with frequency. Notably, higher temperatures result in greater cumulative thermal conductivity values.

Figure 6(b) presents the thermal conductivity change with respect to frequency. Acoustic phonons exhibit a significantly higher thermal conductivity change compared to optical phonons. According to Equation

7, this rate of change is multiplied by the phonon density of states. The analysis reveals that low-frequency acoustic phonons contribute most substantially to thermal conductivity, followed by mid-frequency optical phonons, while the high-frequency LO2’ optical branch makes negligible contribution. Additionally, the thermal conductivity decreases with increasing temperature across all frequency ranges.

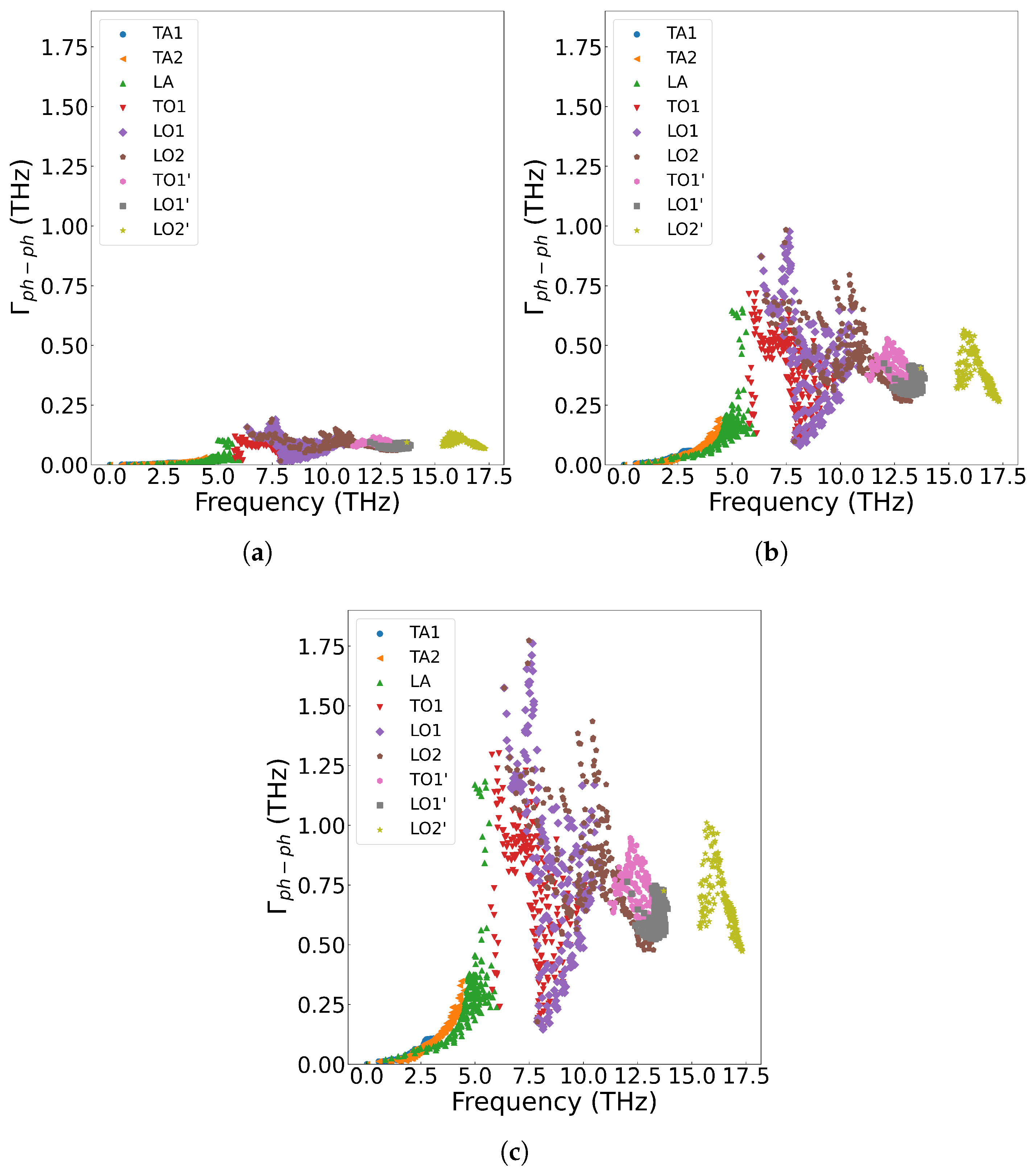

Figure 7 displays the three-phonon scattering intensities for different phonon frequency branches at various temperatures. The results demonstrate that as temperature increases, the phonon scattering intensity strengthens across all frequency branches, leading to reduced mean free paths and shorter phonon lifetimes.

3.3.2. Solid Fission Products

The metallic elements produced during nuclear fission predominantly exist as cationic species[

4,

53]. These metallic atoms incorporate substitutionally into the UO

2 lattice, replacing uranium atoms and acting as scattering centers for phonon transport. The phonon scattering intensity induced by these defects can be quantified using Equation

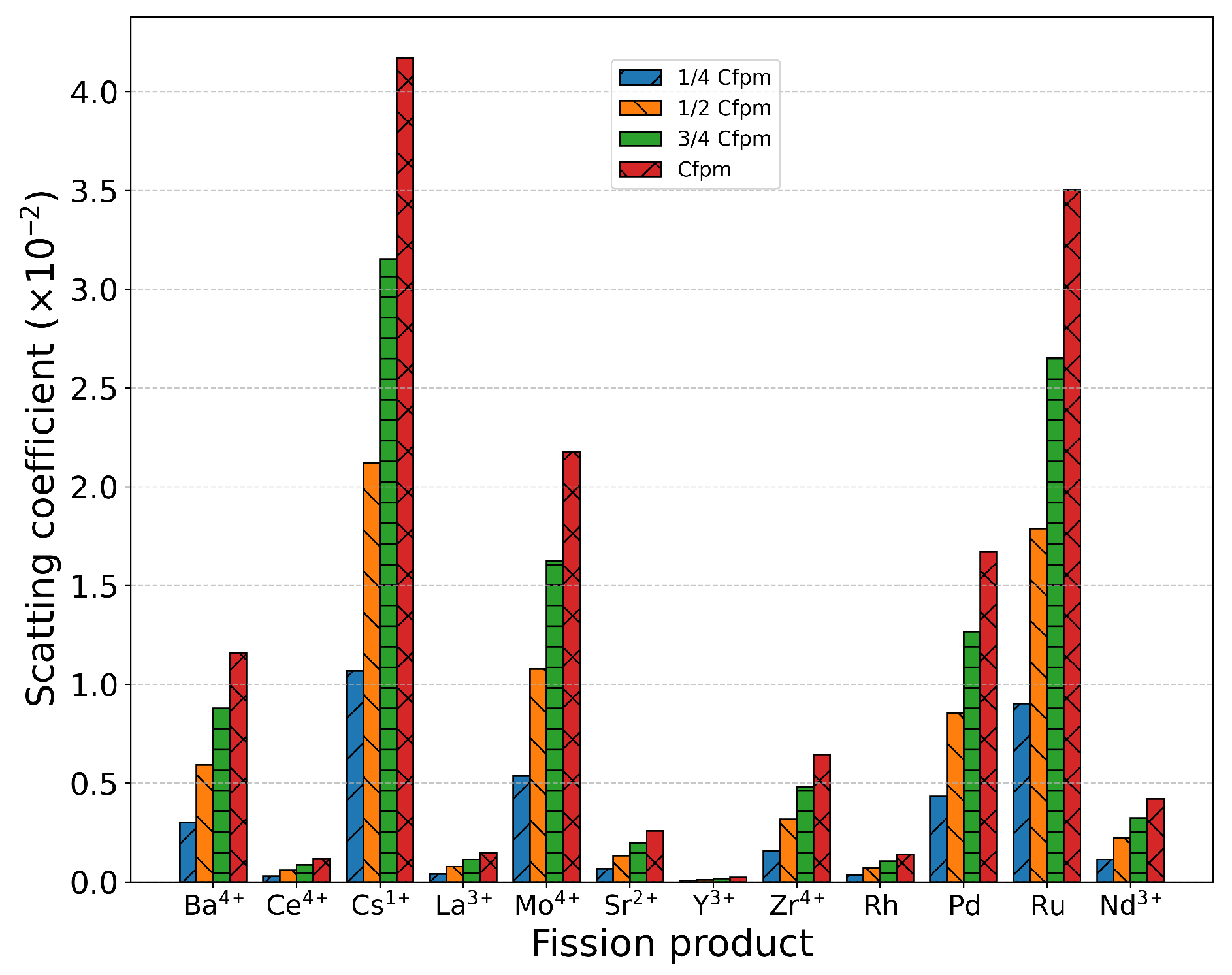

7. Since the concentration of metal ions remains constant with temperature variation, their scattering strength depends exclusively on their concentration and intrinsic properties rather than thermal conditions.

Table 1[

54] presents the concentrations of various metallic fission products measured in SIMFUEL samples (76 GWd/t burnup) from Chalk River Laboratories, Canada. The scattering intensity of each metallic ion was calculated based on its valence state and ionic radius within the UO

2 matrix [47], with

and

reference radii of 1.001 Å and 1.368 Å respectively, as shown in

Table 1. The calculated scattering intensities of fission product elements are presented in

Figure 8, revealing the following descending order of scattering strength:

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

. Analysis of these point defects in

Table 1 demonstrates that the scattering intensity is governed by two key parameters as shown in

Figure 8: 1) The mass difference between impurity and host atoms (

); 2) The ionic radius mismatch (

). Notably, the radius difference

dominates the scattering behavior, as it simultaneously accounts for: 1) Modifications in local force constants between the dopant and surrounding matrix atoms; 2) Lattice strain induced by volumetric changes at defect sites.

In Equation

7, the constant

is typically determined through experimental measurements. Masayuki et al.[

55] investigated the thermal conductivity of ceramic solid solutions in ThO

2-UO

2 fuel systems. By fitting thermal conductivity data across different temperatures and uranium solid solubility levels, they determined

= 100 for the ThO

2 system, which was subsequently used to accurately predict the thermal conductivity of ThO

2-CeO

2 at various temperatures. Duriez et al.[

27] adopted a linear regression approach in their study of thermal conductivity in non-stoichiometric (U,Pu)O

2-x mixed oxide fuels with low plutonium content, obtaining

= 25.85 for UO

2. However, there remains no consensus on the optimal value of

, and this study adopts

= 25.85.

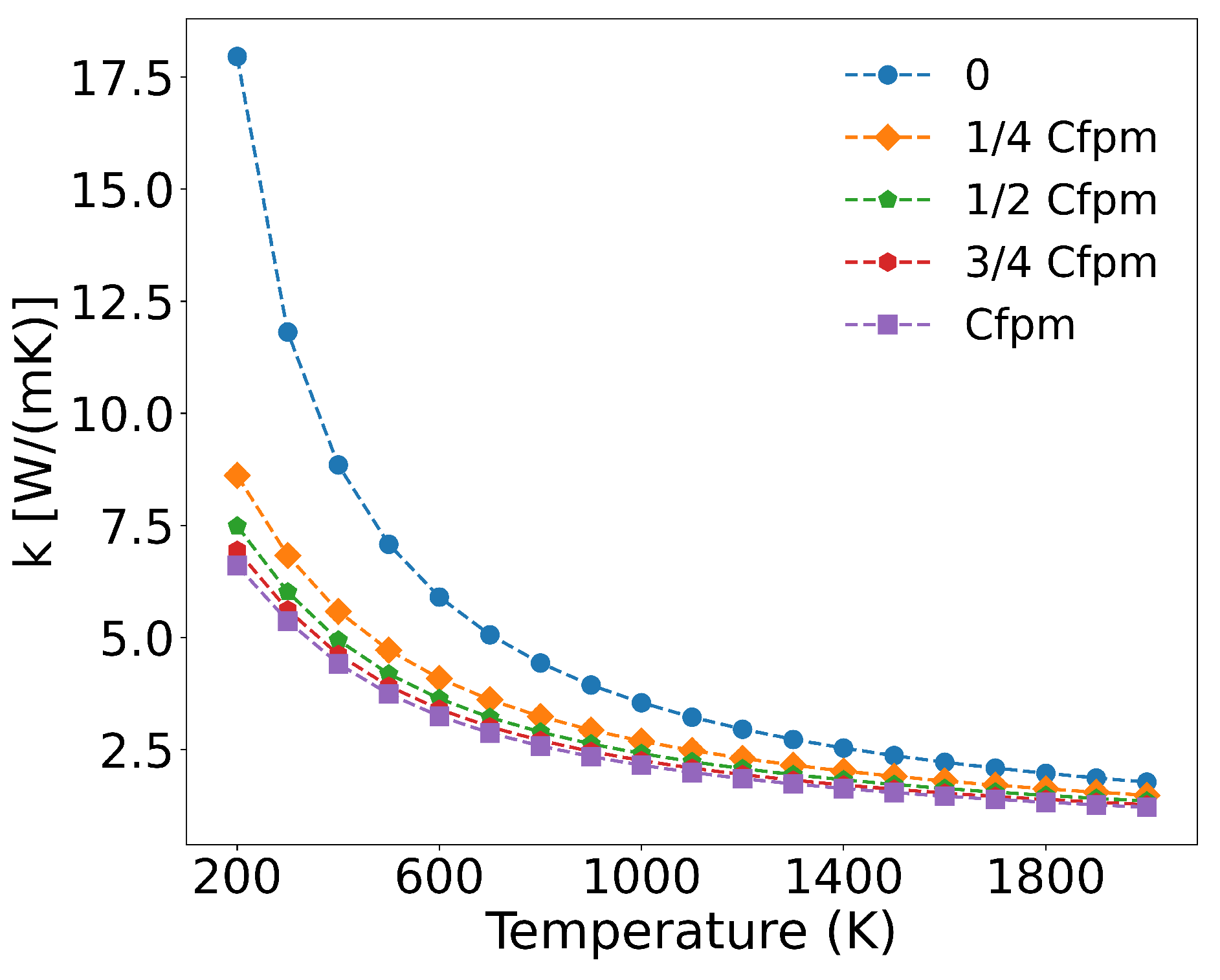

Based on measured concentrations of metallic fission products (denoted as Cfpm) in UO

2 fuel at 76 GWd/t burnup, and assuming a linear relationship between metal atom concentration and burnup, we established four concentration levels: 1/4Cfpm, 1/2Cfpm, 3/4Cfpm, and Cfpm, corresponding to burnups of 19 GWd/t, 38 GWd/t, 57 GWd/t, and 76 GWd/t, respectively. The temperature-dependent thermal conductivity of UO

2 was then calculated for these varying metal ion concentrations. As shown in

Figure 9, the thermal conductivity progressively decreases with increasing metal ion concentration, and the calculated values align well with experimental data[

56]. The incorporation of metallic defects reduces the thermal conductivity of UO

2, particularly in the 200-1000K range where reductions exceed 50%. However, the incremental effect diminishes at higher concentrations (1/4Cfpm to Cfpm), suggesting that the impact of fission product metal ions on thermal conductivity saturates beyond a threshold concentration.

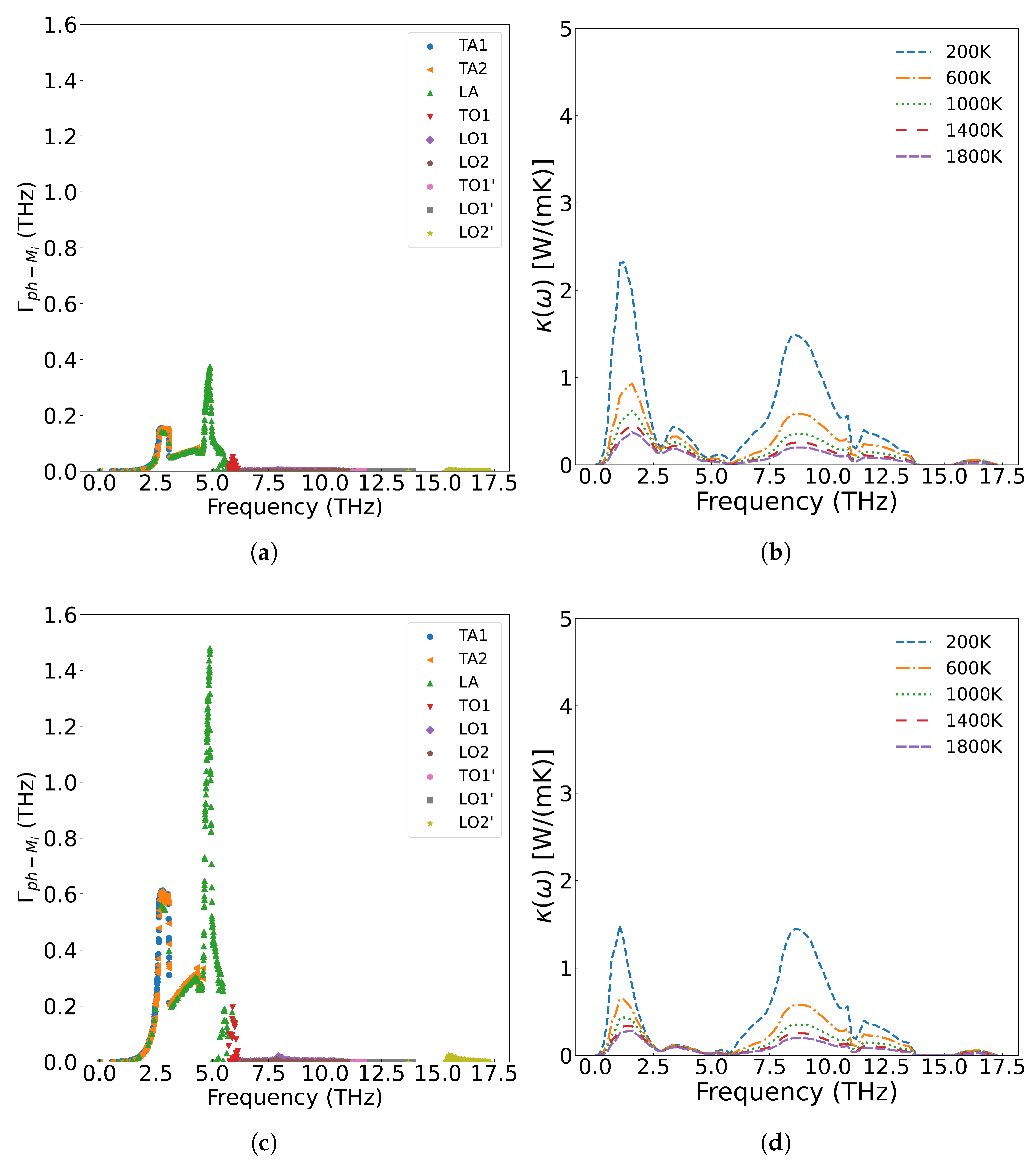

Figure 10 presents the frequency-dependent phonon scattering intensities. Lower defect concentrations yield weaker scattering, with metallic fission products primarily scattering the low-frequency acoustic branches generated by uranium atom vibrations. The scattering intensity increases with concentration, while optical branches originating from oxygen atom vibrations remain virtually unaffected. Consequently, the reduction in thermal conductivity predominantly stems from scattering of low-frequency phonons.

3.3.3. Fission Gas Xe

The fission gas atom Xe differs from solid fission metal atoms in that, as an inert gas atom, it scarcely forms chemical bonds with the UO

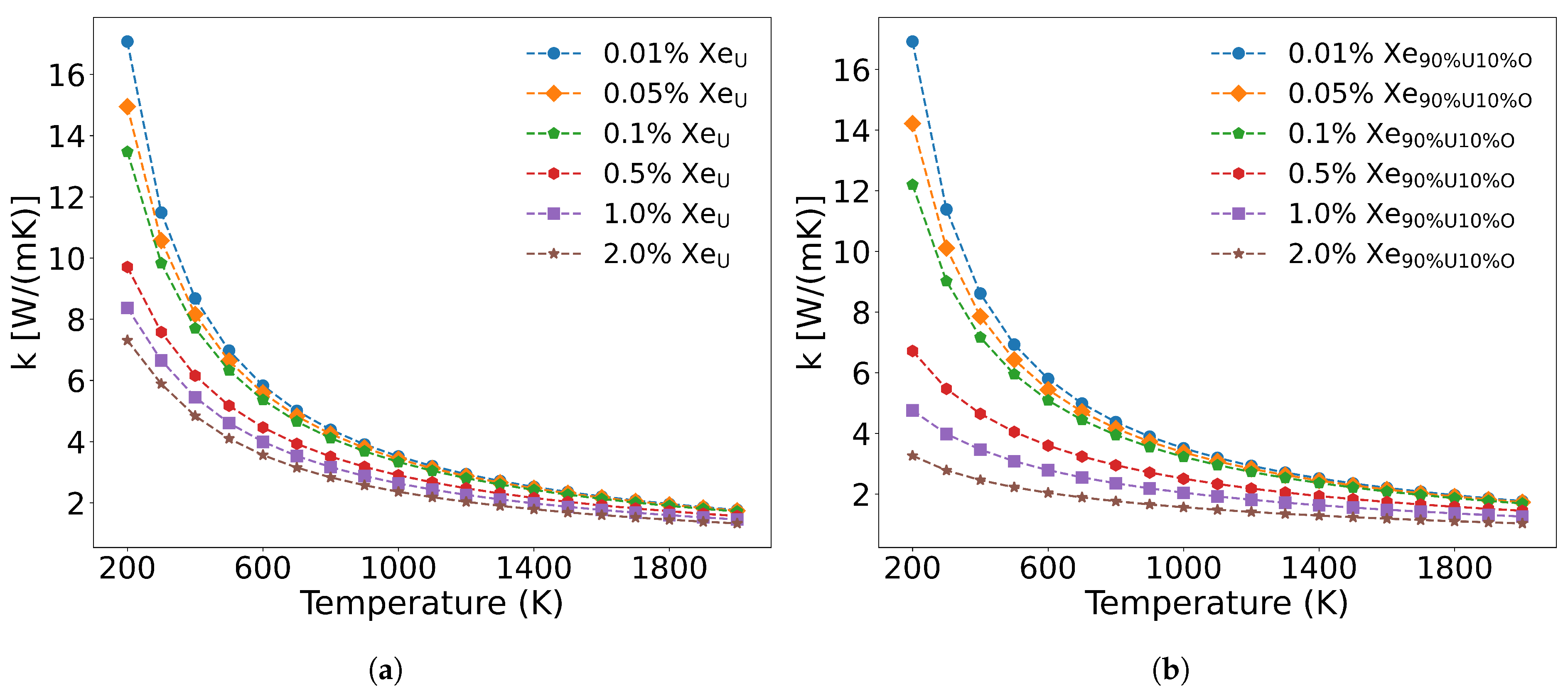

2 matrix. Its primary phonon scattering mechanisms arise from mass contrast, atomic size mismatch, and modifications to interatomic force constants near Xe defects. Xe atoms predominantly occupy irradiation-induced U and O vacancies, forming substitutional defects that are dispersed throughout the lattice.

Figure 11 illustrates the influence of varying Xe concentrations on thermal conductivity when substituting for U sites alone versus simultaneous substitution at both U and O sites. As shown in

Figure 11(a), when Xe occupies only U vacancies, low concentrations (<0.1 at%) exhibit minimal impact on thermal conductivity, whereas higher concentrations (>0.5 at%) induce significant degradation between 200–1000 K. This effect diminishes at elevated temperatures (>1000 K), where three-phonon scattering becomes dominant. Below 1000 K, Xe exerts strong phonon scattering that weakens progressively with increasing temperature. These results agree with molecular dynamics simulations by CHEN et al.[

57], though potentials by Basak and Busker overestimate thermal conductivity (16.10 and 18.99 W/(m·K) at 300 K compared to our calculated value of 11.813 W/(m·K). By systematically evaluating thermal conductivity at 0.33%, 0.67%, 1.0%, and 2.0% Xe concentrations, we established a predictive model for high-burnup UO

2 fuel performance.

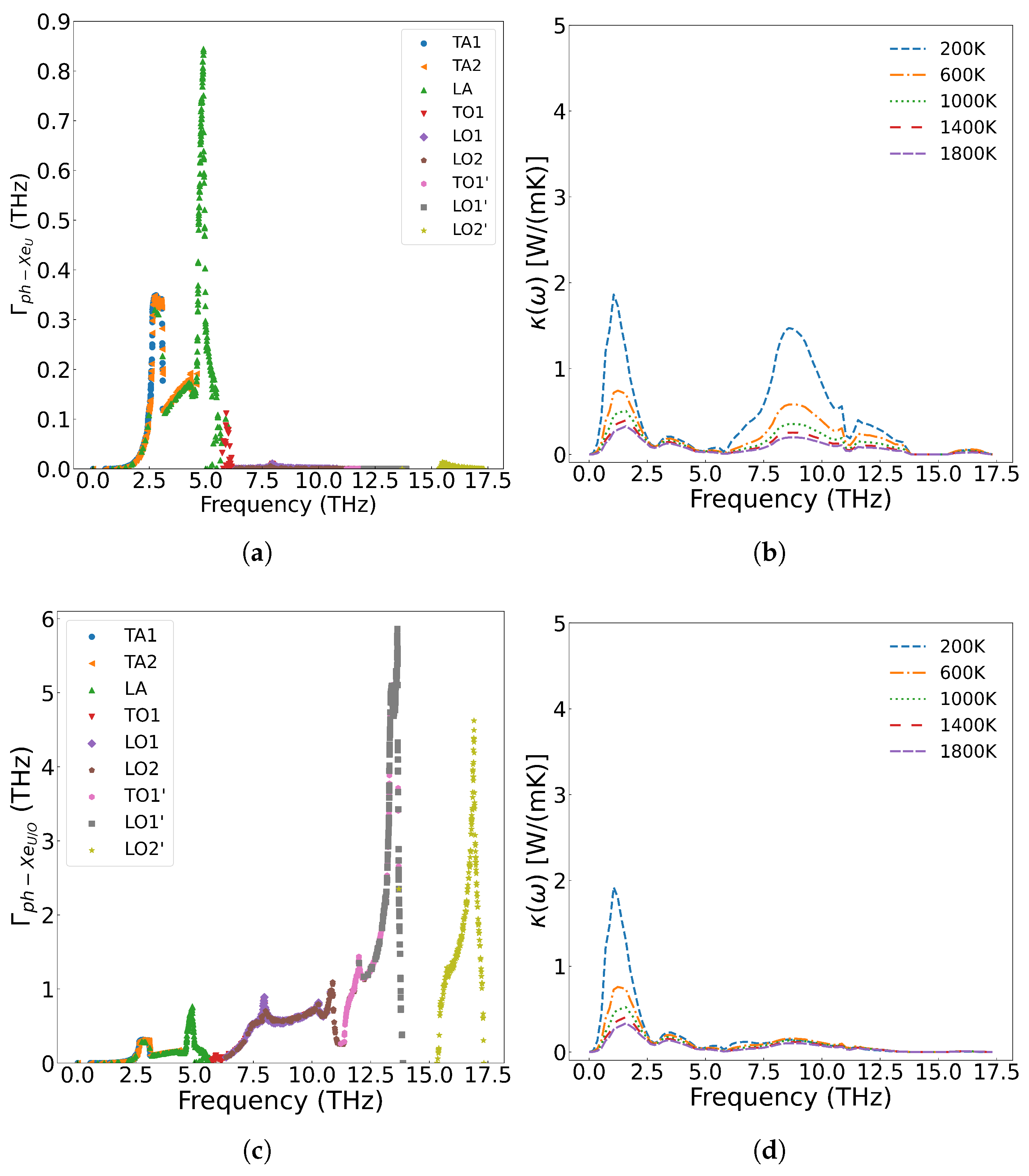

As shown in

Figure 11(a), when Xe atoms occupy only U vacancies, they primarily scatter the low-frequency acoustic phonon modes generated by U atom vibrations. However, when Xe atoms simultaneously occupy both U and O vacancies at the same concentration, their impact on thermal conductivity becomes more pronounced than when occupying U vacancies alone. This is demonstrated in

Figure 11(b), where a distribution of 90 at% Xe in U vacancies and 10 at% Xe in O vacancies results in greater thermal conductivity reduction at identical temperatures compared to the case where Xe occupies only U sites. The underlying mechanism, illustrated in

Figure 12, reveals that Xe atoms occupying O vacancies exhibit stronger scattering of high-frequency phonons (generated by O atom vibrations) than the scattering of low-frequency phonons (generated by U atom vibrations). Fission gas Xe atoms significantly degrade the thermal conductivity of UO

2, demonstrating strong scattering effects on both low- and high-frequency phonons, with the specific influence depending on their occupation sites.

3.3.4. Irradiated Point Defects

Unlike fission products, the concentration and distribution of irradiation-induced defects are strongly influenced by neutron energy spectra and irradiation temperature. The calculated formation energies of point defects in UO

2[

58,

59], revealing that while the formation energy of oxygen interstitials is negative, all other types of point defects exhibit positive and relatively high formation energies. According to Equation

7, since uranium interstitials and oxygen interstitials induce identical mass and radius differences (with the same proportionality constants being used), their scattering intensities are equivalent to those of vacancies. To analyze the effect of irradiation defects on UO

2 thermal conductivity,

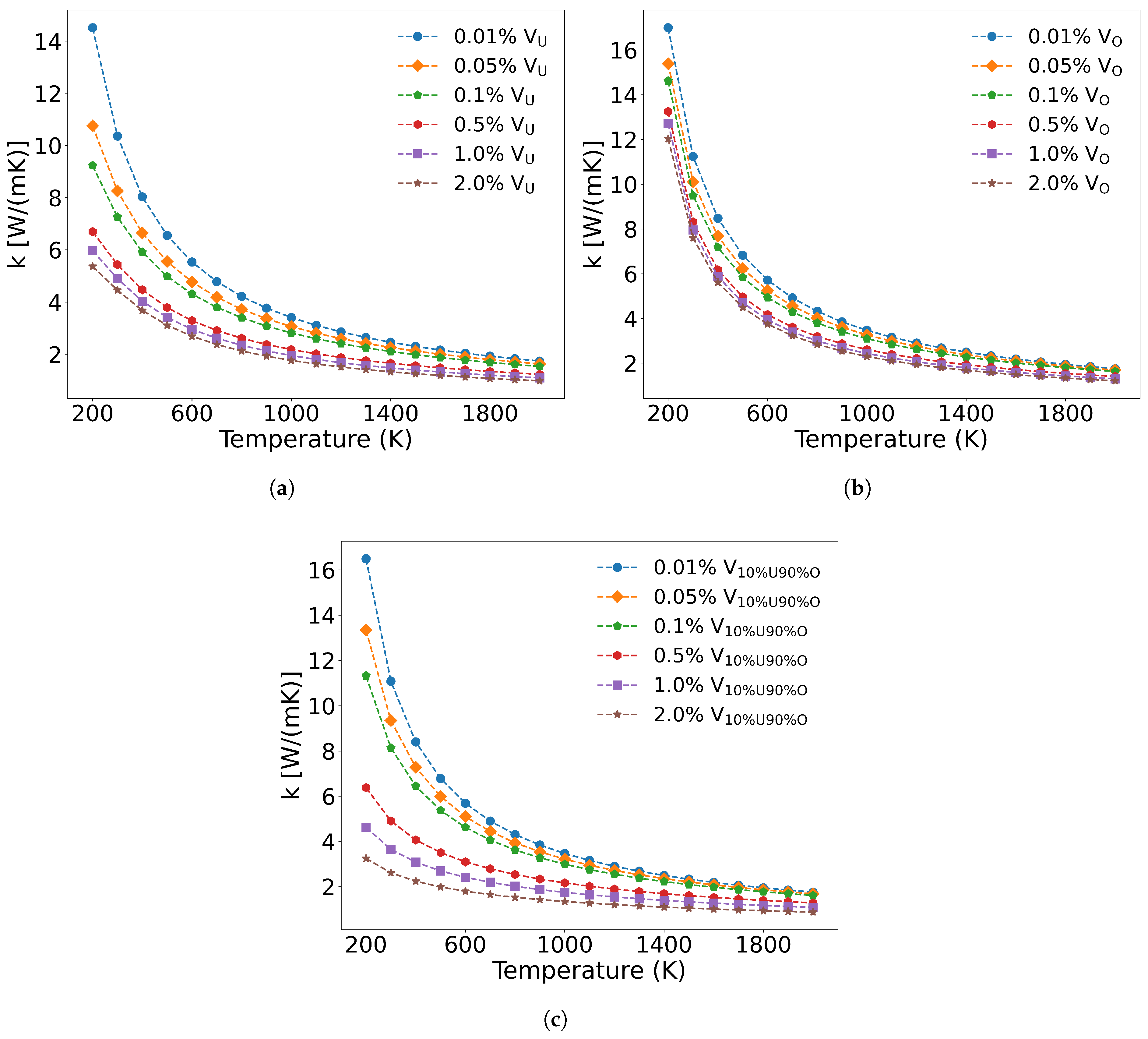

Figure 13(a) and

Figure 13(b) present the temperature-dependent thermal conductivity changes caused by irradiation-generated U and O vacancies. At equal concentrations, U vacancies demonstrate a greater impact on thermal conductivity reduction compared to O vacancies. However, in actual irradiated UO

2, defects simultaneously contain both U and O vacancies. In this case, as shown in

Figure 13(c), both acoustic and optical phonon branches are scattered by vacancies, leading to more significant thermal conductivity degradation than when either U or O vacancies exist alone.

Kaloni et al.[

60] employed the DFT+U method to investigate the electronic and phonon thermal conductivity of non-stoichiometric UO

x (x = 1.75-2.0, corresponding to oxygen vacancy concentrations of 0-12.5%). For x < 1.87 (oxygen vacancy concentration <6.5%), the phonon thermal conductivity decreases with increasing oxygen vacancy concentration, consistent with our computational results. While the electronic thermal conductivity in this regime exceeds that of stoichiometric UO

2, the increase remains marginal. However, when the oxygen vacancy concentration exceeds 6.5%, the thermal conductivity of UOx unexpectedly increases. This phenomenon arises from the insulator-to-metal transition in highly oxygen-deficient UOx, where enhanced electronic thermal conductivity dominates the overall heat transport.

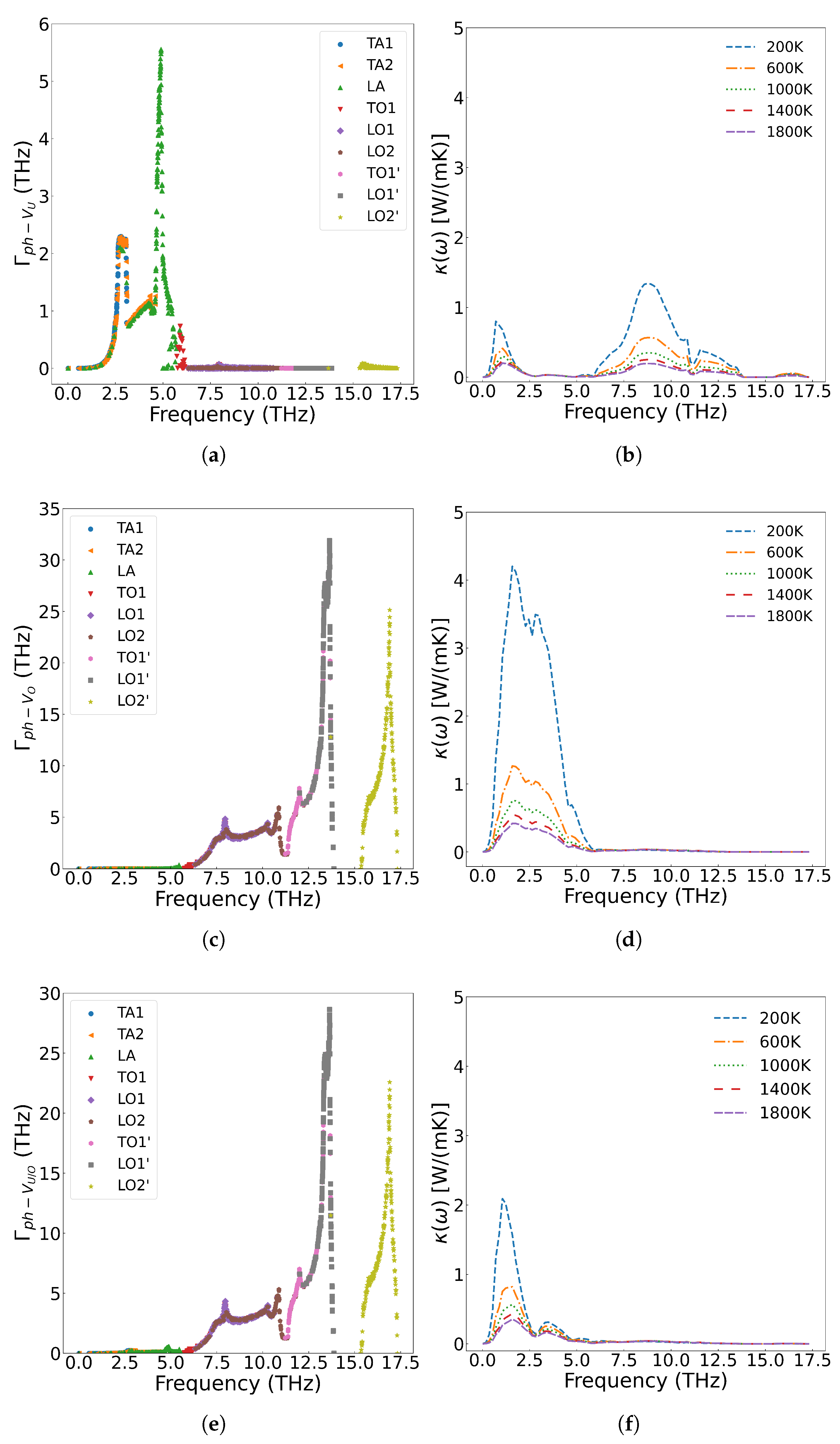

Figure 14 presents the scattering strength of 2.0% U and O vacancies on phonons and their temperature-dependent effects on thermal conductivity across different phonon frequencies. The results demonstrate that both U and O vacancies reduce thermal conductivity of UO

2, but through distinct mechanisms: U vacancies primarily scatter low-frequency acoustic phonons, while O vacancies preferentially scatter high-frequency optical phonons. Notably, the combined presence of both vacancy types leads to broadband phonon scattering across all frequencies, resulting in more significant thermal conductivity reduction than either defect alone.

4. Conclusions

The present study elucidates the electronic, vibrational, and thermal transport properties of UO2, bridging first-principles calculations with experimental observations to provide a comprehensive understanding of its behavior under nuclear reactor conditions. Our findings not only validate and extend prior theoretical and experimental work but also raise new questions regarding defect-phonon interactions and thermal conductivity degradation mechanisms in irradiated nuclear fuels. Our DFT+U calculations (U = 3.6 eV) confirm UO2 is Mott insulating nature, consistent with spectroscopic measurements showing a 2.0 eV bandgap. While earlier LDA/GGA studies erroneously predicted metallic behavior, our approach aligns with advanced DFT+U and hybrid functional treatments (Dorado et al.; Pegg et al., 2016), reinforcing the necessity of electron correlation corrections for 5f systems. The slight overestimation of the lattice constant ( 1.2%) is a known limitation of the PBE functional, as noted in prior works (Yun et al., 2018), but does not compromise the electronic or phonon descriptions. The phonon dispersion and Grüneisen parameter ( = 1.86) agree well with inelastic neutron scattering data (Dolling et al., 1965) and earlier DFT+U studies (Njifon et al., 2019). However, the deviation in high-frequency TO2 modes suggests that explicit anharmonic corrections—beyond the quasiharmonic approximation—may be necessary to fully capture finite-temperature effects. This aligns with recent molecular dynamics (MD) studies (Geng et al., 2021) showing significant phonon softening at reactor-relevant temperatures (>1000 K).

Our calculated thermal conductivity () for pristine UO2 follows the classic 1/T dependence expected for phonon-dominated insulators, matching Slack-model predictions (Islam et al., 2018) but exceeding experimental values (Fink et al., 1981). This discrepancy arises because real fuels contain intrinsic defects (e.g., oxygen vacancies, dislocations) even in "unirradiated" samples, as observed in SIMFUEL studies (Lucuta et al., 1996). The stronger reduction in defective UO2 underscores the importance of defect engineering in fuel design. Notably, the saturation of suppression at high fission metal concentrations ( 76 GWd/t) suggests a transition from point-defect scattering to percolation-like phonon blocking, a phenomenon also observed in ThO2-UO2 solid solutions (Masayuki et al., 2020). For Xe, the dual role of U- and O-site occupation in scattering both acoustic and optical phonons resolves a long-standing debate—MD simulations (Chen et al., 2020) previously attributed degradation solely to strain fields, but our work shows chemical bonding disruption (e.g., weakened U-O forces near Xe) is equally critical. However, our defect models assume isolated point defects in irradiated fuels, complex defect clusters (e.g., Xe bubbles, metal precipitates) and extended defects (dislocations, grain boundaries) likely introduce additional phonon scattering mechanisms not accounted for here. Future work should integrate ab initio phonon calculations with multiscale modeling approaches (e.g., phase-field, kinetic Monte Carlo) to simulate defect evolution under irradiation and its impact on thermal transport. This study not only provides a fundamental framework for UO2 thermal transport but also establishes design principles for developing more efficient nuclear fuels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jiantao Qin, Lu Wu and Aitao tang; methodology, Min Zhao and Rongjian pan; software, Jiantao Qin; validation, Min Zhao, Jiantao Qin and Rongjian pan; formal analysis, Jiantao Qin; investigation,Jiantao Qin and Min Zhao; resources, Lu Wu; data curation, Jiantao Qin; writing—original draft preparation, Jiantao Qin; writing—review and editing, Jiantao Qin; visualization, Rongjian pan; supervision, Aitao tang; project administration, Lu Wu; funding acquisition, Lu Wu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2022YFB1902401) and Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (grant number 2024NSFSC0190).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from The National Natural Science Foundation of China and Sichuan Provincial Department of Science and Technology for this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Simnad, M.T., Nuclear Reactor Materials and Fuels. In Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology; Elsevier, 2003; pp. 775–815. [CrossRef]

-

Thermal Conductivity of Uranium Dioxide; Number 59 in Technical Reports Series, INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY: Vienna, 1966.

- Olander, D. Point-defects in irradiated UO2. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2010, 399, 236–239. [CrossRef]

- Glodeanu, F. PROCESSES of UO2 fuel cycle. Unpublished 2020, pp. 1–108. [CrossRef]

- Sheykhi, S.; Payami, M. Electronic structure properties of UO2 as a Mott insulator. Physica C: Superconductivity and its Applications 2018, 549, 93–94. [CrossRef]

- Rondinella, V.V.; Wiss, T. The high burn-up structure in nuclear fuel. Materials Today 2010, 13, 24–32. [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. A re-appraisal of the thermal conductivity of UO2 and mixed (U,Pu) oxide fuels. Journal of Nuclear Materials 1982, 110, 73–94. [CrossRef]

- Minato, K.; Shiratori, T.; Serizawa, H.; Hayashi, K.; Une, K.; Nogita, K.; Hirai, M.; Amaya, M. Thermal conductivities of irradiated UO2 and (U,Gd)O2. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2001, 288, 57–65. [CrossRef]

- Philipponneau, Y. Thermal conductivity of (U,Pu)O2-x mixed oxide fuel. Journal of Nuclear Materials 1992, 188, 194–197. [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, C.; Sheindlin, M.; Staicu, D.; Kinoshita, M. Effect of burn-up on the thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide up to 100.000 MWdt-1. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2004, 327, 58–76. [CrossRef]

- Gibby, R. The effect of plutonium content on the thermal conductivity of (U,Pu)O2 solid solutions. Journal of Nuclear Materials 1971, 38, 163–177. [CrossRef]

- Amaya, M.; Hirai, M. Recovery behavior of thermal conductivity in irradiated UO2 pellets. Journal of Nuclear Materials 1997, 247, 76–81. [CrossRef]

- Carbajo, J.J.; Yoder, G.L.; Popov, S.G.; Ivanov, V.K. A review of the thermophysical properties of MOX and UO2 fuels. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2001, 299, 181–198. [CrossRef]

- Cozzo, C.; Staicu, D.; Somers, J.; Fernandez, A.; Konings, R.J.M. Thermal diffusivity and conductivity of thorium-plutonium mixed oxides. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2011, 416, 135–141. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.T.; Zheng, J.J.; Qu, X.; Li, W.D.; Zhang, P. Thermal conductivity of UO2 and PuO2 from first-principles. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2015, 628, 267–271. [CrossRef]

- Callaway, J. Model for Lattice Thermal Conductivity at Low Temperatures. Physical Review 1959, 113, 1046–1051. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. First-principles Debye-Callaway approach to lattice thermal conductivity. Journal of Materiomics 2016, 2, 237–247. [CrossRef]

- Higuchi, S.i. A Molecular Dynamics Study of Thermal Conductivity of UO2 with Impurities. Journal of Nuclear Science and Technology 2012, 35, 833–835. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, M.H.; Kaviany, M. Lattice thermal conductivity of UO2 using ab-initio and classical molecular dynamics. Journal of Applied Physics 2014, 115. [CrossRef]

- Nichenko, S.; Staicu, D. Thermal conductivity of porous UO2: Molecular Dynamics study. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2014, 454, 315–322. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, G.P. The Physics of Phonons; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hurley, D.H.; El-Azab, A.; Bryan, M.S.; Cooper, M.W.D.; Dennett, C.A.; Gofryk, K.; He, L.; Khafizov, M.; Lander, G.H.; Manley, M.E.; et al. Thermal Energy Transport in Oxide Nuclear Fuel. Chem Rev 2022, 122, 3711–3762. [CrossRef]

- Fugallo, G.; Lazzeri, M.; Paulatto, L.; Mauri, F. Ab initiovariational approach for evaluating lattice thermal conductivity. Physical Review B 2013, 88. [CrossRef]

- Maradudin, A.A.; Fein, A.E. Scattering of Neutrons by an Anharmonic Crystal. Physical Review 1962, 128, 2589–2608. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, S.i. Isotope scattering of dispersive phonons in Ge. Physical Review B 1983, 27, 858–866. [CrossRef]

- Abeles, B. Lattice Thermal Conductivity of Disordered Semiconductor Alloys at High Temperatures. Physical Review 1963, 131, 1906–1911. [CrossRef]

- Duriez, C.; Alessandri, J.P.; Gervais, T.; Philipponneau, Y. Thermal conductivity of hypostoichiometric low Pu content (U,Pu)O2-x mixed oxide. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2000, 277, 143–158. [CrossRef]

- Klemens, P.G. The Scattering of Low-Frequency Lattice Waves by Static Imperfections. Proceedings of the Physical Society. Section A 1955, 68, 1113–1128. [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, R.; Hanus, R.; Dylla, M.; Katre, A.; Snyder, G.J. Analytical Models of Phonon-Point-Defect Scattering. Physical Review Applied 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects. Physical Review 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Physical Review B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Ruzsinszky, A.; Csonka, G.I.; Vydrov, O.A.; Scuseria, G.E.; Constantin, L.A.; Zhou, X.; Burke, K. Restoring the Density-Gradient Expansion for Exchange in Solids and Surfaces. Physical Review Letters 2008, 100. [CrossRef]

- Dudarev, S.L.; Botton, G.A.; Savrasov, S.Y.; Humphreys, C.J.; Sutton, A.P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Physical Review B 1998, 57, 1505–1509. [CrossRef]

- Dudarev, S.L.; Liu, P.; Andersson, D.A.; Stanek, C.R.; Ozaki, T.; Franchini, C. Parametrization of LSDA+U for noncollinear magnetic configurations: Multipolar magnetism in UO2. Physical Review Materials 2019, 3. [CrossRef]

- Dorado, B.; Amadon, B.; Freyss, M.; Bertolus, M. DFT+U calculations of the ground state and metastable states of uranium dioxide. Physical Review B 2009, 79. [CrossRef]

- Gonze, X. Perturbation expansion of variational principles at arbitrary order. Physical Review A 1995, 52, 1086–1095. [CrossRef]

- Togo, A.; Tanaka, I. First principles phonon calculations in materials science. Scripta Materialia 2015, 108, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Togo, A.; Chaput, L.; Tanaka, I. Distributions of phonon lifetimes in Brillouin zones. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 094306. [CrossRef]

- Gonze, X.; Lee, C. Dynamical matrices, Born effective charges, dielectric permittivity tensors, and interatomic force constants from density-functional perturbation theory. Physical Review B 1997, 55, 10355–10368. [CrossRef]

- Iwasawa, M.; Chen, Y.; Kaneta, Y.; Ohnuma, T.; Geng, H.Y.; Kinoshita, M. First-Principles Calculation of Point Defects in Uranium Dioxide. MATERIALS TRANSACTIONS 2006, 47, 2651–2657. [CrossRef]

- Pegg, J.T.; Aparicio-Anglès, X.; Storr, M.; de Leeuw, N.H. DFT+U study of the structures and properties of the actinide dioxides. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2017, 492, 269–278. [CrossRef]

- Dolling, G.; Cowley, R.A.; Woods, A.D.B. THE CRYSTAL DYNAMICS OF URANIUM DIOXIDE. Canadian Journal of Physics 1965, 43, 1397–1413. [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.W.; Buyers, W.J.; Chernatynskiy, A.; Lumsden, M.D.; Larson, B.C.; Phillpot, S.R. Phonon lifetime investigation of anharmonicity and thermal conductivity of UO2 by neutron scattering and theory. Phys Rev Lett 2013, 110, 157401. [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.; Legut, D.; Oppeneer, P.M. Phonon spectrum, thermal expansion and heat capacity of UO2 from first-principles. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2012, 426, 109–114. [CrossRef]

- Sanati, M.; Albers, R.C.; Lookman, T.; Saxena, A. Elastic constants, phonon density of states, and thermal properties of UO2. Physical Review B 2011, 84. [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.; CheikNjifon, I.; Kaloni, T.P.; Pencer, J. A comparative analysis of the phonon properties in UO2 using the Boltzmann transport equation coupled with DFT+U and empirical potentials. Computational Materials Science 2020, 177. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.T.; Zhang, P.; Lizárraga, R.; Di Marco, I.; Eriksson, O. Phonon spectrum, thermodynamic properties, and pressure-temperature phase diagram of uranium dioxide. Physical Review B 2013, 88. [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, C.; Sheindlin, M.; Musella, M.; Hyland, G.J. Thermal conductivity of uranium dioxide up to 2900 K from simultaneous measurement of the heat capacity and thermal diffusivity. Journal of Applied Physics 1999, 85, 776–789. [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.; Chasanov, M.; Leibowitz, L. Thermophysical properties of uranium dioxide. Journal of Nuclear Materials 1981, 102, 17–25. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M. DFT and DFT+U Insights into the Physical Properties of UO2. Journal of Scientific Research 2023, 15, 739–757. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Xiao, E.; Ma, H.; Gofryk, K.; Jiang, C.; Manley, M.E.; Hurley, D.H.; Marianetti, C.A. Phonon Thermal Transport in UO2 via Self-Consistent Perturbation Theory. Physical Review Letters 2024, 132. [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.G.; Stan, M.; Yang, J. First-principles study of thermophysical properties of uranium dioxide. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2014, 603, 282–286. [CrossRef]

- Perriot, R.; Liu, X.Y.; Stanek, C.R.; Andersson, D.A. Diffusion of Zr, Ru, Ce, Y, La, Sr and Ba fission products in UO2. Journal of Nuclear Materials 2015, 459, 90–96. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, E.; Bès, R.; Martin, P.; Pontillon, Y.; Solari, P.L.; Salome, M. Fission products behaviour in UO2 submitted to nuclear severe accident conditions. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2016, 712, 012098. [CrossRef]

- Murabayashi, M. Thermal Conductivity of Ceramic Solid Solutions. Journal of Nuclear Science and Technology 1970, 7, 559–563. [CrossRef]

- ISHIMOTO, S.; HIRAI, M.; ITO, K.; KOREI, Y. Effects of Soluble Fission Products on Thermal Conductivities of Nuclear Fuel Pellets. Journal of Nuclear Science and Technology 1994, 31, 796–802. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Bai, X.M. Unified Effect of Dispersed Xe on the Thermal Conductivity of UO2 Predicted by Three Interatomic Potentials. Jom 2020, 72, 1710–1718. [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.; Oppeneer, P.M. First-principles design of next-generation nuclear fuels. MRS Bulletin 2011, 36, 178–184. [CrossRef]

- Dorado, B.; Freyss, M.; Amadon, B.; Bertolus, M.; Jomard, G.; Garcia, P. Advances in first-principles modelling of point defects in UO2: f electron correlations and the issue of local energy minima. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 2013, 25. [CrossRef]

- Kaloni, T.P.; Onder, N.; Pencer, J.; Torres, E. DFT+U approach on the electronic and thermal properties of hypostoichiometric UO2. Annals of Nuclear Energy 2020, 144. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

The 3k antiferromagnetic (AFM) ordering in conventional unit cell of UO2.

Figure 1.

The 3k antiferromagnetic (AFM) ordering in conventional unit cell of UO2.

Figure 2.

(a) The lattice constant of UO2 with the U parameter, (b) The band structure and electronic density of states of UO2 at U = 3.35 eV and J = 0.0 eV.

Figure 2.

(a) The lattice constant of UO2 with the U parameter, (b) The band structure and electronic density of states of UO2 at U = 3.35 eV and J = 0.0 eV.

Figure 3.

The phonon spectrum and density of states of UO2. The hollow circles represent the measured values from inelastic neutron scattering, and the solid lines represent the simulated DFT+U calculation results. The fractional coordinates of the high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone are (0 0 0), X (0.5 0 0.5), W (0.5 0.25 0.75), and L (0.5 0.5 0.5).

Figure 3.

The phonon spectrum and density of states of UO2. The hollow circles represent the measured values from inelastic neutron scattering, and the solid lines represent the simulated DFT+U calculation results. The fractional coordinates of the high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone are (0 0 0), X (0.5 0 0.5), W (0.5 0.25 0.75), and L (0.5 0.5 0.5).

Figure 4.

Phonon spectra, density of states, and Grüneisen parameters of UO2 at different volumes: (a) a = 5.33 Å, (b) a = 5.406 Å, (c) Grüneisen parameters along high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone.

Figure 4.

Phonon spectra, density of states, and Grüneisen parameters of UO2 at different volumes: (a) a = 5.33 Å, (b) a = 5.406 Å, (c) Grüneisen parameters along high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone.

Figure 5.

Figure 4 Calculated phonon thermal conductivity of UO2 crystal with DTF+U+SOC and comparison with values reported in the literature.

Figure 5.

Figure 4 Calculated phonon thermal conductivity of UO2 crystal with DTF+U+SOC and comparison with values reported in the literature.

Figure 6.

(a) Cumulative thermal conductivity of UO2 at different temperatures, (b) The thermal conductivity of UO2 with respect to phonon frequency.

Figure 6.

(a) Cumulative thermal conductivity of UO2 at different temperatures, (b) The thermal conductivity of UO2 with respect to phonon frequency.

Figure 7.

Three-phonon scattering intensity in single-crystal UO2 at different temperatures: (a) 200 K (b) 1000 K, (c) 1800 K.

Figure 7.

Three-phonon scattering intensity in single-crystal UO2 at different temperatures: (a) 200 K (b) 1000 K, (c) 1800 K.

Figure 8.

Scattering coefficients of metal ions/atoms with different mass and radii under each concentration.

Figure 8.

Scattering coefficients of metal ions/atoms with different mass and radii under each concentration.

Figure 9.

Concentration-dependent thermal conductivity of UO2 with fission product metal ions.

Figure 9.

Concentration-dependent thermal conductivity of UO2 with fission product metal ions.

Figure 10.

The scattering intensity of metal ions on phonons at different concentrations: (a) 1/4 Cfpm, (c) Cfpm; The effect of scattering on thermal conductivity at different concentrations:(b) 1/4 Cfpm, (d) Cfpm.

Figure 10.

The scattering intensity of metal ions on phonons at different concentrations: (a) 1/4 Cfpm, (c) Cfpm; The effect of scattering on thermal conductivity at different concentrations:(b) 1/4 Cfpm, (d) Cfpm.

Figure 11.

The effect of Xe concentration on thermal conductivity: (a) Xe substitutes only U, and (b) Xe simultaneously substitutes 90% U and 10% O.

Figure 11.

The effect of Xe concentration on thermal conductivity: (a) Xe substitutes only U, and (b) Xe simultaneously substitutes 90% U and 10% O.

Figure 12.

2.0 at% Xe in UO2: (a) Frequency-dependent phonon scattering intensity when Xe substitutes U sites only; (b) Effect on thermal conductivity from U-site substitution; (c) Scattering intensity when Xe substitutes both U and O sites; (d) Effect on thermal conductivity from U+O site substitution.

Figure 12.

2.0 at% Xe in UO2: (a) Frequency-dependent phonon scattering intensity when Xe substitutes U sites only; (b) Effect on thermal conductivity from U-site substitution; (c) Scattering intensity when Xe substitutes both U and O sites; (d) Effect on thermal conductivity from U+O site substitution.

Figure 13.

Thermal conductivity decrease in UO2 with different vacancy concentrations: (a) Only uranium vacancies, (b) Only oxygen vacancies, (c) Simultaneously containing uranium and oxygen vacancies.

Figure 13.

Thermal conductivity decrease in UO2 with different vacancy concentrations: (a) Only uranium vacancies, (b) Only oxygen vacancies, (c) Simultaneously containing uranium and oxygen vacancies.

Figure 14.

Frequency-dependent phonon scattering intensity of 2.0 at% vacancies in UO2: (a) U vacancies only, (c) O vacancies only, (e) U and O vacancies; Effect on thermal conductivity from 2.0 at% vacancies in UO2: (b) U vacancies only, (d) O vacancies only, (f) U and O vacancies.

Figure 14.

Frequency-dependent phonon scattering intensity of 2.0 at% vacancies in UO2: (a) U vacancies only, (c) O vacancies only, (e) U and O vacancies; Effect on thermal conductivity from 2.0 at% vacancies in UO2: (b) U vacancies only, (d) O vacancies only, (f) U and O vacancies.

Table 1.

Content, oxidation states and ionic radii of fission elements in SIMFUEL samples of 76 GWd/t burnup.

Table 1.

Content, oxidation states and ionic radii of fission elements in SIMFUEL samples of 76 GWd/t burnup.

| Fission Element |

Ba |

Ce |

Cs |

La |

Mo |

Sr |

Y |

Zr |

Rh |

Pd |

Ru |

Nd |

| Content (at%) |

0.26 |

0.61 |

0.35 |

0.20 |

0.61 |

0.13 |

0.06 |

0.60 |

0.03 |

0.42 |

0.64 |

0.91 |

| Oxidation State |

2+ |

4+ |

1+ |

3+ |

4+ |

2+ |

3+ |

4+ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3+ |

| Ionic Radius (Å) |

1.42 |

0.97 |

1.69 |

1.16 |

0.65 |

1.26 |

1.02 |

0.84 |

1.42 |

1.39 |

1.46 |

1.12 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).