Submitted:

13 April 2025

Posted:

14 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC:

1. Introduction

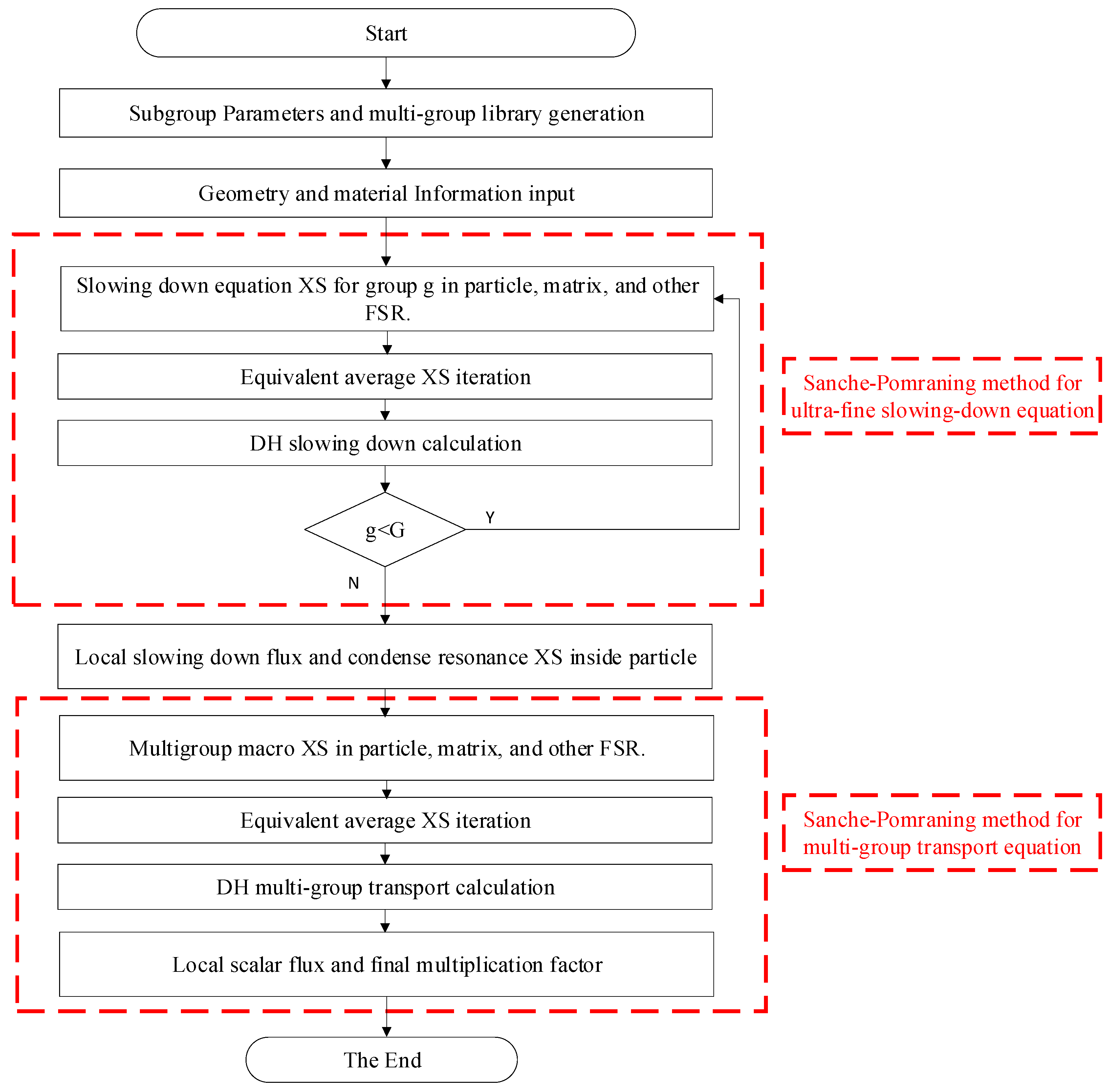

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ultra-fine group slowing-down equation

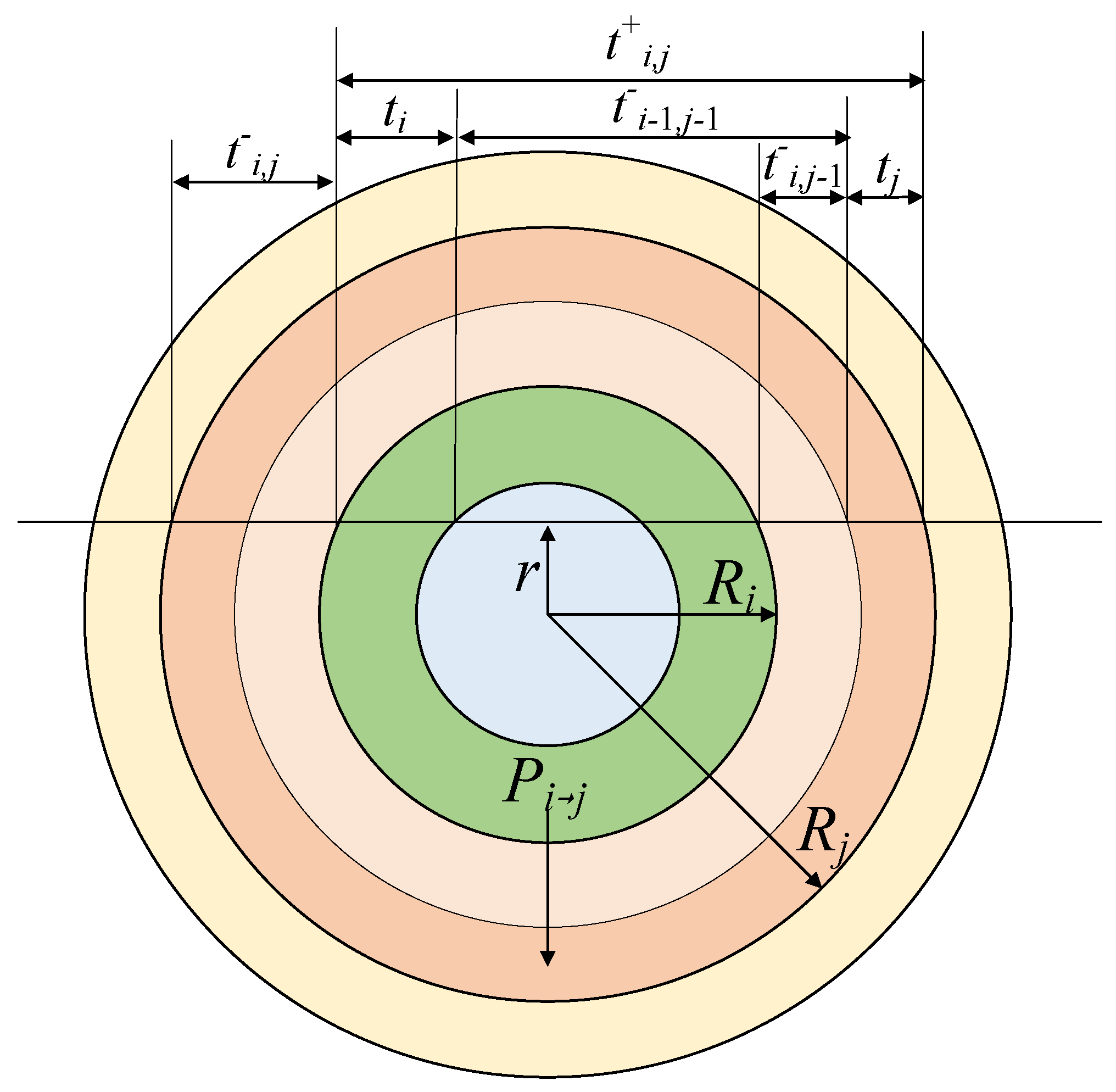

2.2. Stochastic Medium Ultra-fine Group Equations Based on the Sanchez-Pomraning Method

3. Results

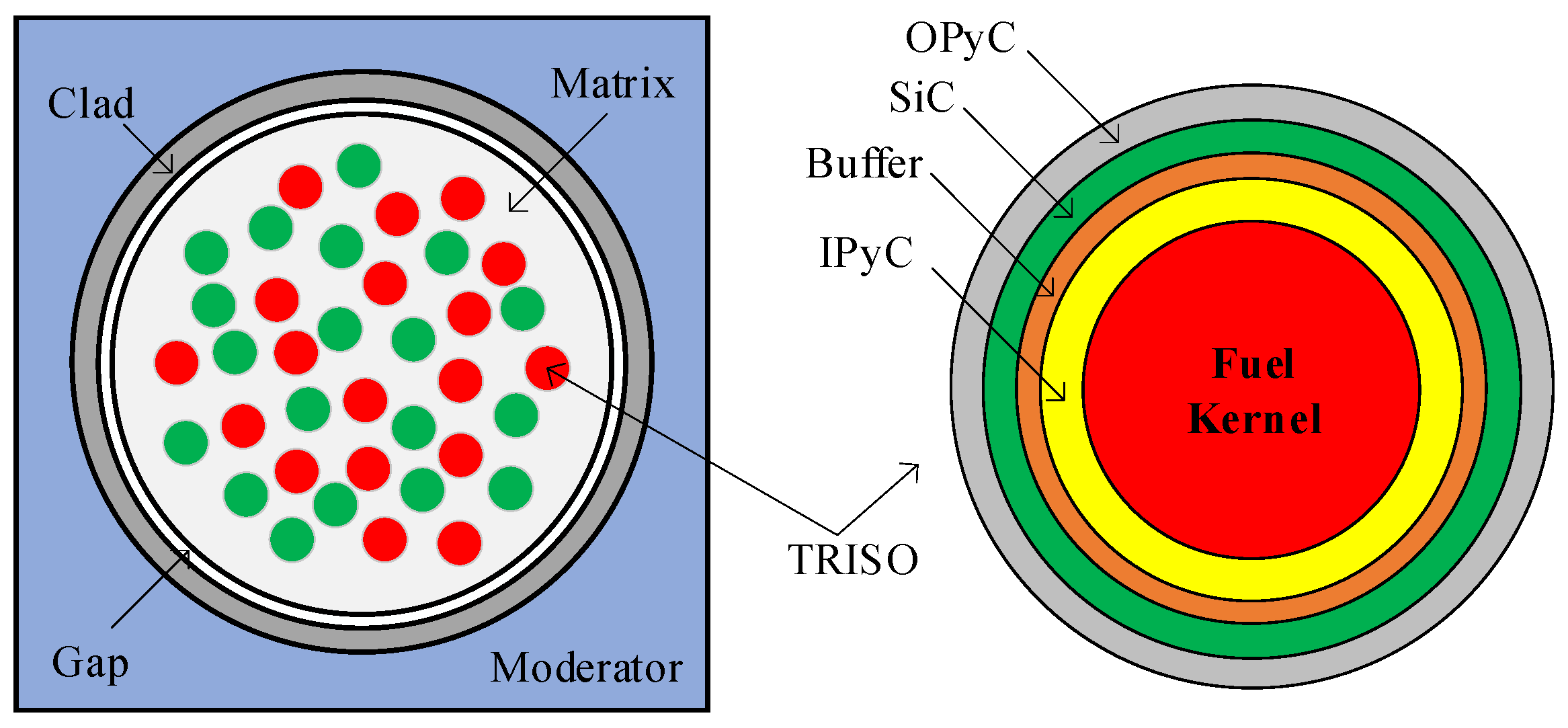

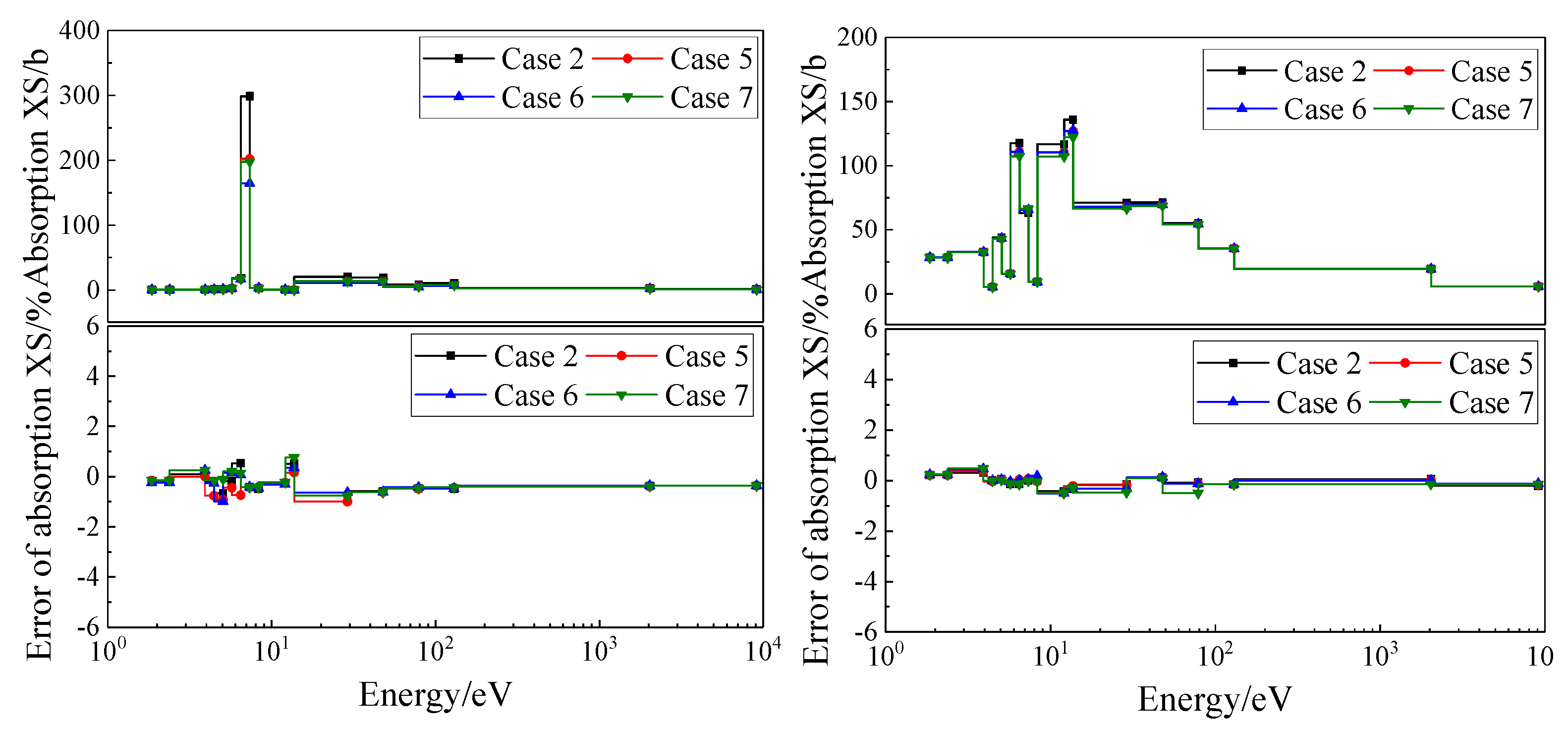

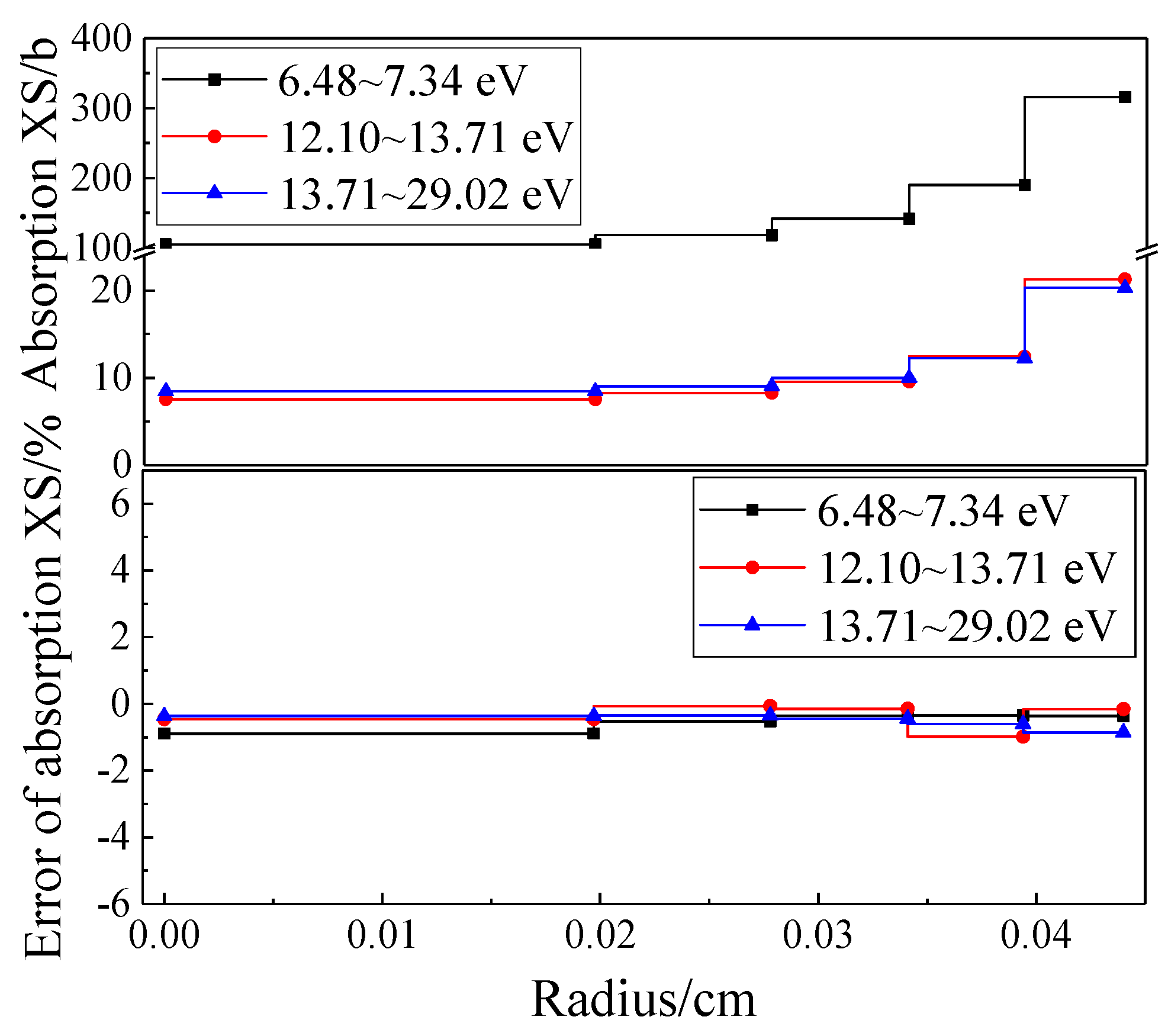

3.1. Typical FCM fuel problem

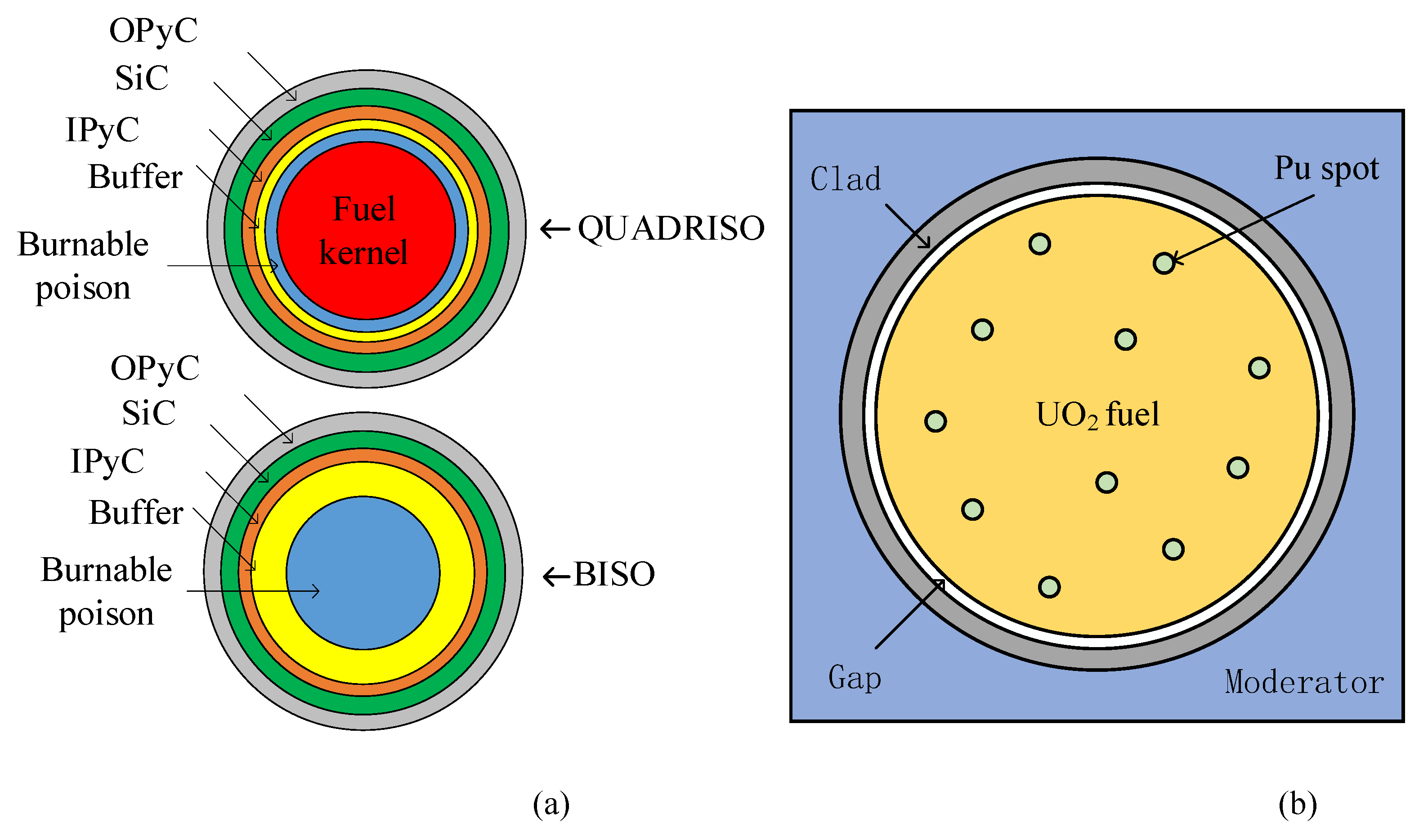

3.2. Burable poison and Pu spot problem

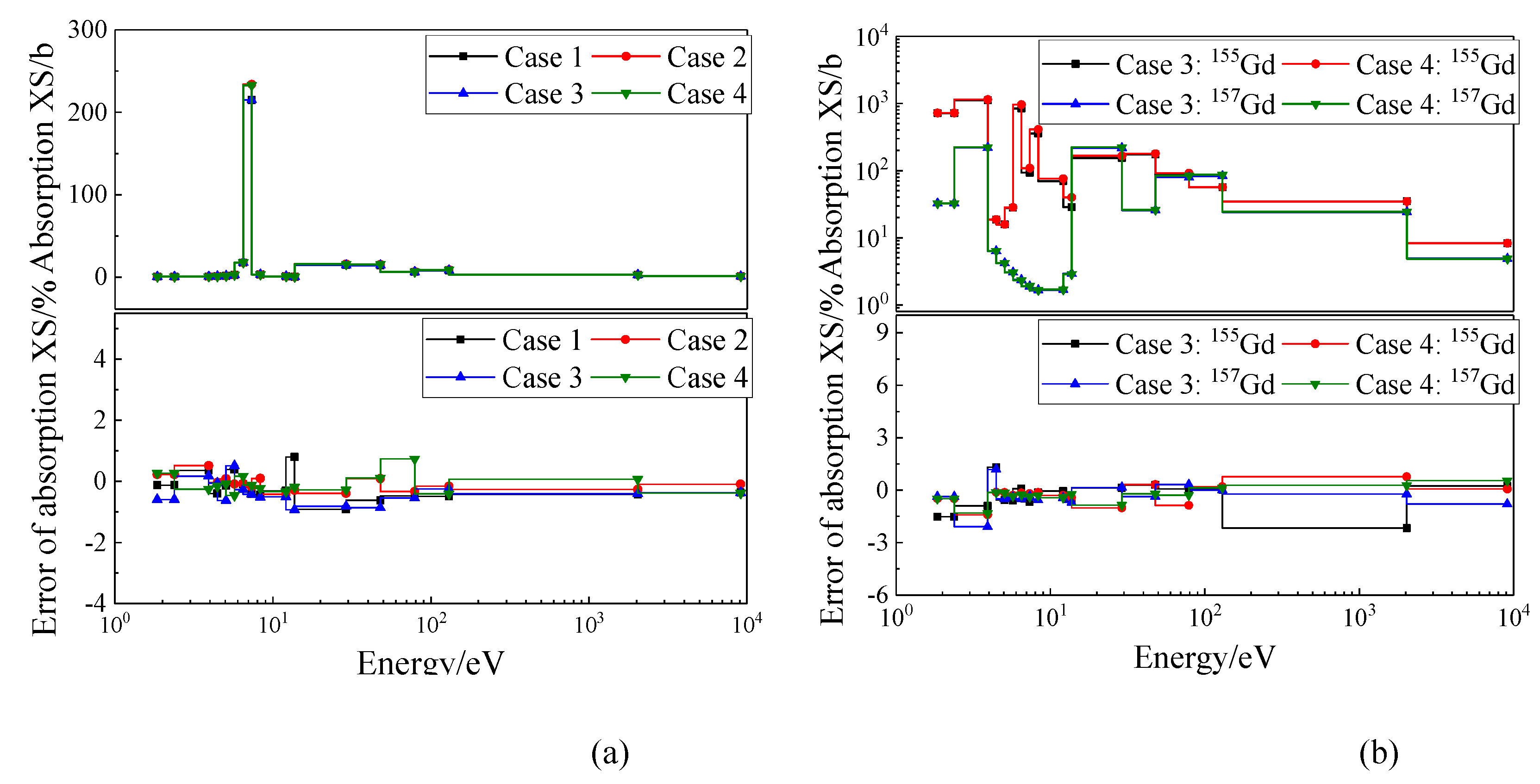

3.2.1. Poison problems

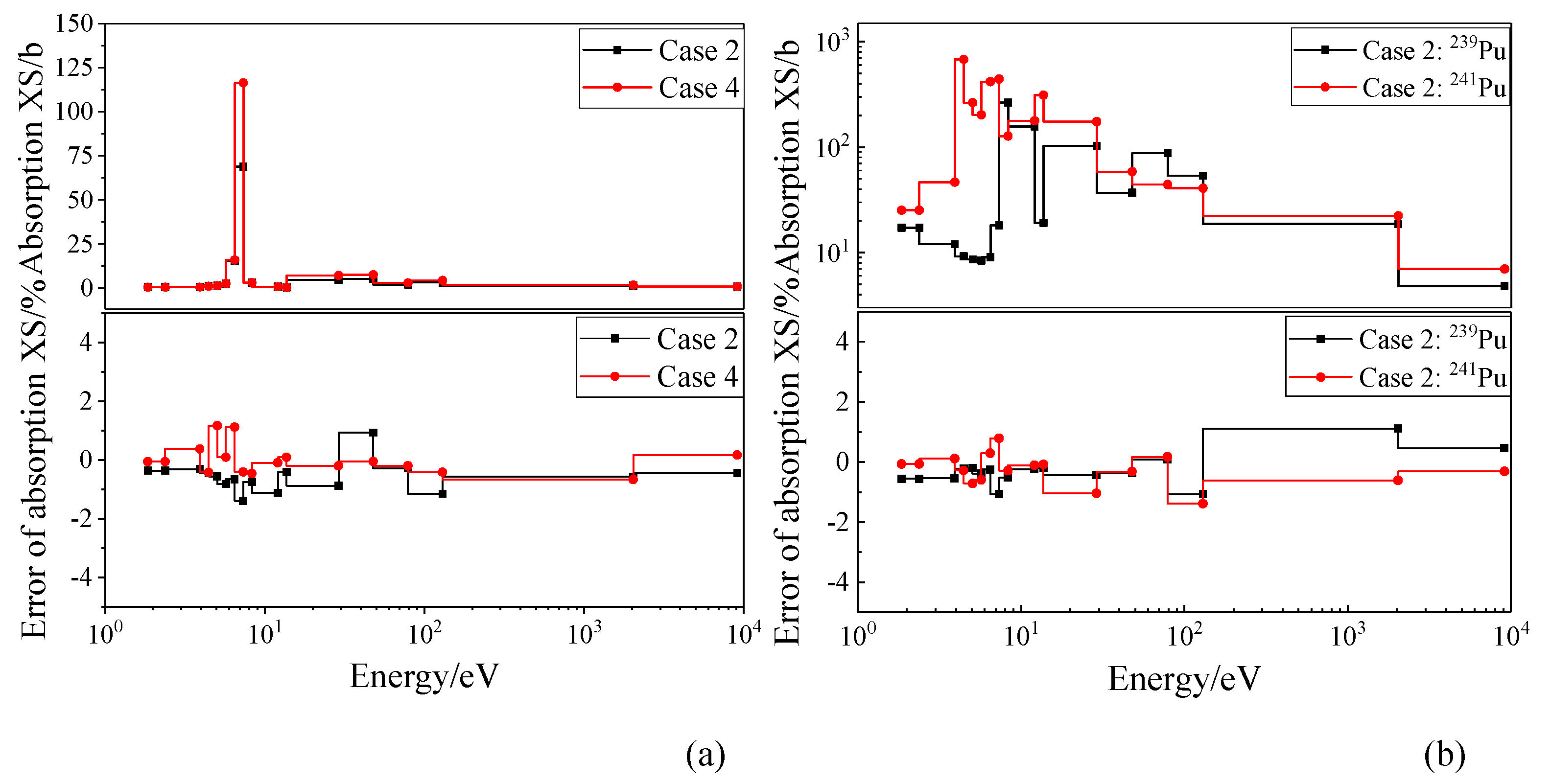

3.2.2. Pu spots problem

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2024; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pioro, I. Handbook of Generation-IV Nuclear Reactors. J. Nucl. Eng. Radiat. Sci. 2017, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Endo, T. Application of Neutron Current Method for Dancoff Factor Estimation of Fuel Particles in Double-Heterogeneous Fuel. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, L.; Chai, X.; Yao, D.; et al. Hybrid Reactivity-Equivalent Physical Transformation Method on Double-Heterogeneous System Containing Dispersed Fuel Particles and Burnable Poison Particles. J. Nucl. Eng. Radiat. Sci. 2022, 8, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, J.N.; Gupta, J.; Shaikh, I.H. TRISO Fuel Volume Fraction and Homogeneity: A Nondestructive Characterization. Nucl. Sci. Tech. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ankrum, A.R.; Bohlander, K.L.; Gilbert, E.R.; et al. Comparisons of ANSI Standards Cited in the NRC Standard Review Plan, NUREG-0800 and Related Documents. Off. Sci. Tech. Inf. Tech. Rep. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Ding, M. Study of the Neutronic and Thermal Coupling Effect on VHTR Fuel Pebble Using OpenMC and OpenFOAM. Ann. Nucl. Energy, 2023, 183, 109643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, S.; Park, M.; et al. Extension of Double Heterogeneity Treatment Method for Coated TRISO Fuel Particles. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2017, 99, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coissieux, T.; Politello, J.; Vaglio-Gaudard, C.; et al. Development of a 3D APOLLO3 Neutron Deterministic Calculation Scheme for the CABRI Experimental Reactor. Nuclear Science and Engineering 2023, 197, 1717–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Jeon, B.K.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Verification and Validation Tests of Gamma Library of MC2-3 for Coupled Neutron and Gamma Heating Calculation. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2020, 146, 107609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bende, E.E.; Hogenbirk, A.H.; Kloosterman, J.L.; et al. Analytical Calculation of the Average Dancoff Factor for a Fuel Kernel in a Pebble Bed High-Temperature Reactor. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 1999, 133, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Liang, C.; Pusateri, E.N. Analytical Dancoff Factor Evaluations for Reactor Designs Loaded with TRISO Particle Fuel. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2014, 63, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Choi, S.; Park, M.; et al. Extension of Double Heterogeneity Treatment Method for Coated TRISO Fuel Particles. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2017, 99, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Choi, S.; Lee, D. A New Equivalence Theory Method for Treating Doubly Heterogeneous Fuel-I: Theory. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 2015, 180, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kong, C.; Lee, D.; et al. A New Equivalence Theory Method for Treating Doubly Heterogeneous Fuel-II: Verifications. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 2015, 180, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- She, D.; Liu, Z.; Shi, L. An Equivalent Homogenization Method for Treating the Stochastic Media. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 2017, 185, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Yin, W.; Liu, Z.; et al. Extension of the Subgroup Method for Self-Shielding Calculation of Fully Ceramic Micro-Encapsulated Fuel. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2020, 140, 107136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Zu, T.; He, Q.; et al. Multigroup Effective Cross Section Calculation Method for Fully Ceramic Micro-Encapsulated Fuel. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2019, 125, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R.; Pomraning, G.C. A Statistical Analysis of the Double Heterogeneity Problem. Ann. Nucl. Energy 1991, 18, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, R. Renormalized Treatment of the Double Heterogeneity with the Method of Characteristics. In PHYSOR 2004: International Conference on the Physics of Reactors; Chicago, IL, USA, 2004.

- Pogosbekyan, L.; Kim, G.Y.; Kim, K.S.; et al. Resolution of Double Heterogeneity in Direct Transport Calculation Employing Subgroup Method and Method of Characteristics. In: PHYSOR 2008: International Conference on the Physics of Reactors; Interlaken, Switzerland, 2008.

- Kondo, R.; Endo, T.; Yamamoto, A.; et al. A Resonance Calculation Method Using Energy Expansion Based on a Reduced Order Model: Use of Ultra-Fine Group Spectrum Calculation and Application to Heterogeneous Geometry. In: PHYSOR 2020: International Conference on the Physics of Reactors; Cambridge, United Kingdom, March 29-April 2, 2020.

- Sugimura, N.; Yamamoto, A. Resonance Treatment Based on Ultra-fine-group Spectrum Calculation in the AEGIS Code. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2007, 44, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiguro, Y.; Takano, H. PEACO: A Code for Calculation of Group Constant of Resonance Energy Region in Heterogeneous Systems; JAERI Report; Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute: Japan, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Askew, J.; Fayers, F.; Kemshell, P. General Description of The Lattice Code WIMS. J. Br. Nucl. Energy Soc. 1966, 5, 564–585. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. A Full Core Resonance Self-Shielding Method Accounting for Temperature-Dependent Fuel Subregions and Resonance Interference. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, R.; Endo, T.; Yamamoto, A.; et al. A New Resonance Calculation Method Using Energy Expansion Based on a Reduced Order Model. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 2021, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Peng, X.; Yu, Y.; et al. A New Pin-Resolved Ultra-Fine-Group Method Based on Global-Local Resonance Treatment Framework. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2022, 170, 108954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Hong, S.G. The Method of Characteristics Applied to Solving Slowing Down Equation to Estimate the Self-Shielded Resonance Cross Sections with an Explicit Geometrical Effect. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 2011, 38, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Qin, S.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Improvements on the Method of Ultra-Fine-Group Slowing-Down Solution Coupled with Method of Characteristics on Irregular Geometries. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 2020, 136, 107017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; et al. Evaluation of Burnup Calculation for Double-Heterogeneity System Based on Sanchez-MOC Framework in LWR. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 2020, 147, 107668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liang, L.; et al. Evaluation of the MOC Based on the Sanchez-Pomraning Method for Double Heterogeneity System. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 2020, 151, 107922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Zhang, Q.; Feng, X.; et al. Feasibility Analysis of the Sanchez-Pomraning Method to Treat the Particle Size Distribution in Particle-Dispersed Fuel. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 428, 113537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Evaluation of Improved Subgroup Resonance Treatment Based on Sanchez-Pomraning Method for Double Heterogeneity in PWR. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 2020, 143, 107491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, K.; et al. Research on Application of Heterogeneous Resonance Integral for Double Heterogeneous System. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2025, 212, 111051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.; et al. Investigation of the Chord Length Markovian Probability Distribution for Self-Shielding Treatment on Double Heterogeneity Problem. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 2020, 146, 107658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, M.Q.; Cao, L.; Wu, H. Neutronic Design and Evaluation of a PWR Fuel Assembly with Accident Tolerant-Fully Ceramic Micro-Encapsulated (AT-FCM) Fuel. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2017, 319, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, P.K.; Forget, B. The OpenMC Monte Carlo Particle Transport Code. Ann. Nucl. Energy. 2013, 51, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Hu, J.; Gentry, C.A. Embedded Self-Shielding Method Applied to Doubly Heterogeneous Fully Ceramic Micro-Encapsulated Fuels. In: PHYSOR 2016: International Conference on the Physics of Reactors; Sun Valley, ID, USA, May 1-5, 2016.

- Yamamoto, T.; Sakai, T.; Iwahashi, D. Effect of Pu-Rich Agglomerates in MOX Fuel on Reactivity Analysis of Light Water Reactor MOX Core Physics Experiments. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, A.; Ikehara, T.; Ito, T.; et al. Benchmark Problem Suite for Reactor Physics Study of LWR Next Generation Fuels. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2002, 39, 900–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cell information | TRISO particle information | ||||||

| Region | Material | Radius or half length/cm | Region | Material | Radius A /cm |

Radius B /cm |

Raidus C /cm |

| Matrix | SiC | \ | Fuel kernel | UC | 0.0250 | 0.0440 | 0.0824 |

| Fuel pin | FCM | 0.6252 | Buffer | 12C | 0.0340 | 0.0598 | 0.1120 |

| Gap | 4He | 0.6337 | IPyC | 12C | 0.0380 | 0.0668 | 0.1255 |

| Clad | SS304 | 0.6907 | SiC | SiC | 0.0415 | 0.0730 | 0.1368 |

| Moderator | Water | 0.8250 | OPyC | 12C | 0.0455 | 0.0800 | 0.1500 |

| Case | Packing fraction | Radius type | keff | Calculating error /pcm | ||

| Reference | UFGSP | |||||

| 1 | 1% | Type A | 0.26361 | 0.26425 | 64 | |

| 2 | 10% | Radius A | 1.18118 | 1.18059 | -59 | |

| 3 | 20% | Radius A | 1.44669 | 1.44689 | 20 | |

| 4 | 30% | Radius A | 1.55356 | 1.55385 | 29 | |

| 5 | 40% | Radius A | 1.60640 | 1.60654 | 14 | |

| 6 | 30% | Radius B | 1.54837 | 1.54789 | -48 | |

| 7 | 30% | Radius C | 1.54061 | 1.54049 | -12 | |

| XS type | Parameter | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 |

| 238U ab | MAX | -0.82% | 1.49% | 1.13% | 0.69% | 1.05% | 1.54% | -1.04% |

| AVG | 0.68% | 0.01% | 0.28% | 0.50% | 0.12% | 0.84% | 0.78% | |

| RMS | 0.35% | 0.25% | 0.61% | 0.16% | 0.17% | 0.37% | 0.25% | |

| 235U ab | MAX | 1.98% | 0.96% | 1.55% | 1.96% | 0.77% | 1.21% | 0.39% |

| AVG | 0.67% | 0.02% | 0.16% | 0.58% | 0.65% | 0.97% | 0.71% | |

| RMS | 0.29% | 0.35% | 0.68% | 0.45% | 0.36% | 0.71% | 1.08% | |

| 235U nf | MAX | 0.52% | 1.05% | 1.14% | 1.36% | 0.97% | 1.63% | 1.41% |

| AVG | 0.62% | 0.81% | 0.10% | 0.53% | 0.62% | 0.85% | 0.40% | |

| RMS | 0.22% | 0.36% | 0.64% | 0.42% | 0.60% | 0.41% | 0.37% |

| QUADRISO | BISO | |||||

| Region | Material | Radius of half length/cm | Region | Material | Radius/cm | |

| Fuel kernel | UC | 0.0242 | Burnable poison | B4C/Gd2O3 | 0.0090 | |

| Burnable poison | B4C/Gd2O3 | 0.0250 | ||||

| Buffer | 12C | 0.0340 | Buffer | 12C | 0.0340 | |

| IPyC | 12C | 0.0380 | IPyC | 12C | 0.0380 | |

| SiC | SiC | 0.0415 | SiC | SiC | 0.0415 | |

| OPyC | 12C | 0.0455 | OPyC | 12C | 0.0455 | |

| Poison type | Absorption XS | B4C problems | Gd2O3 problems | ||||

| 238U | 235U | 238U | 235U | 155Gd | 157Gd | ||

| QUADRISO | MAX | -1.40% | 1.91% | 1.81% | 1.60% | 1.13% | 1.88% |

| AVG | -0.09% | 0.40% | 0.43% | -0.85% | 0.50% | -0.40% | |

| RMS | 0.52% | 0.62% | 0.24% | 0.64% | 0.52% | 0.56% | |

| BISO | MAX | 1.37% | 1.55% | -1.12% | 1.34% | -0.96% | 2.09% |

| AVG | 0.45% | -0.28% | -0.06% | 0.49% | 0.38% | 0.34% | |

| RMS | 0.65% | 0.61% | 0.94% | 0.71% | 0.56% | 0.48% | |

| Case | Poison type | Poison particle type | keff | Calculating error /pcm | ||

| Reference | UFGSP | |||||

| 1 | B4C | QUADRISO | 0.66515 | 0.66610 | 95 | |

| 2 | B4C | BISO | 1.37274 | 1.37258 | -16 | |

| 3 | Gd2O3 | QUADRISO | 0.25674 | 0.25812 | 138 | |

| 4 | Gd2O3 | BISO | 1.20785 | 1.20812 | 27 | |

| Pu problems | Absorption XS | UO2 matrix | Pu spot | ||||

| 238U | 235U | 239Pu | 240Pu | 241Pu | 242Pu | ||

| Case 2 | MAX | -2.18% | 1.17% | -1.24% | 2.00% | -1.42% | -1.49% |

| AVG | -0.64% | 0.07% | -0.35% | -0.19% | -0.27% | -0.30% | |

| RMS | 0.91% | 0.68% | 0.58% | 0.77% | 0.59% | 0.73% | |

| Case 4 | MAX | -2.40% | 1.18% | -1.25% | 2.27% | -1.84% | -1.47% |

| AVG | -0.69% | 0.05% | -0.38% | -0.14% | -0.33% | -0.19% | |

| RMS | 0.99% | 0.69% | 0.57% | 0.89% | 0.67% | 0.93% | |

| Case | Pu spot packing fraction | keff | Calculating error/pcm | |

| Reference | UFGSP | |||

| 1 | 0.5% | 0.96051 | 0.95994 | -57 |

| 2 | 1.0% | 1.15557 | 1.15504 | -53 |

| 3 | 1.5% | 1.24676 | 1.24668 | -8 |

| 4 | 2.0% | 1.29703 | 1.29742 | 39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).