Submitted:

30 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. G-Subdiffusion Equation

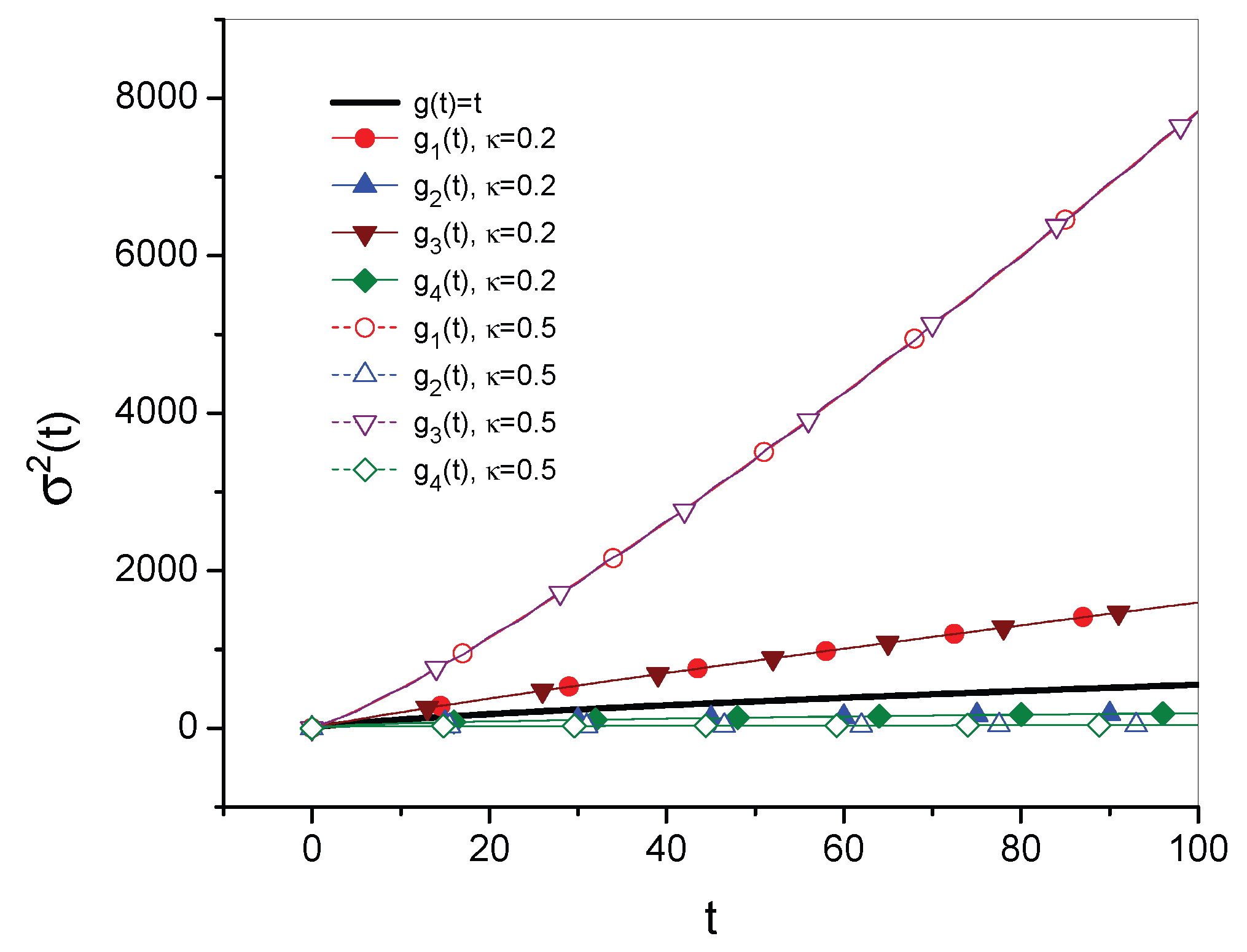

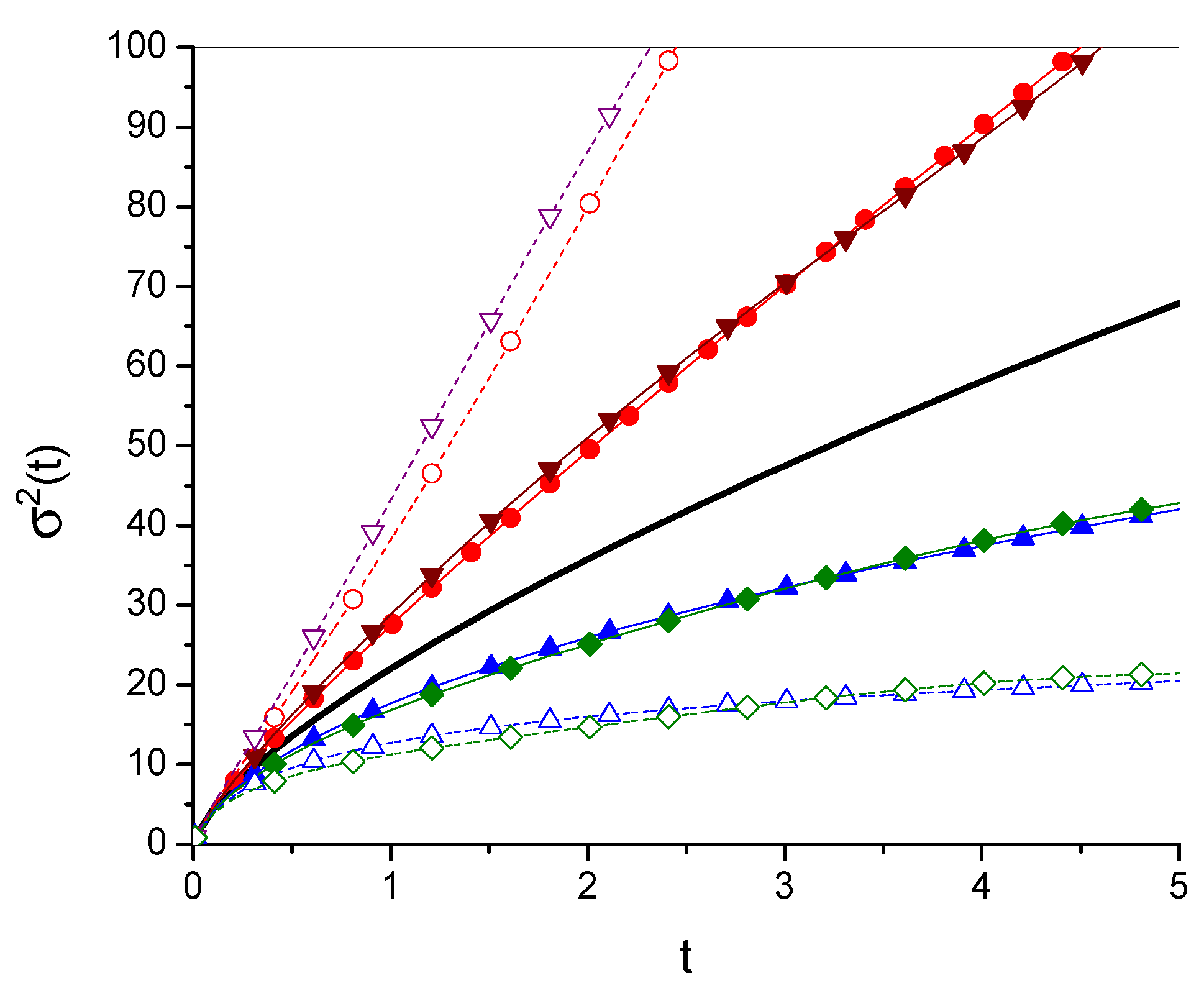

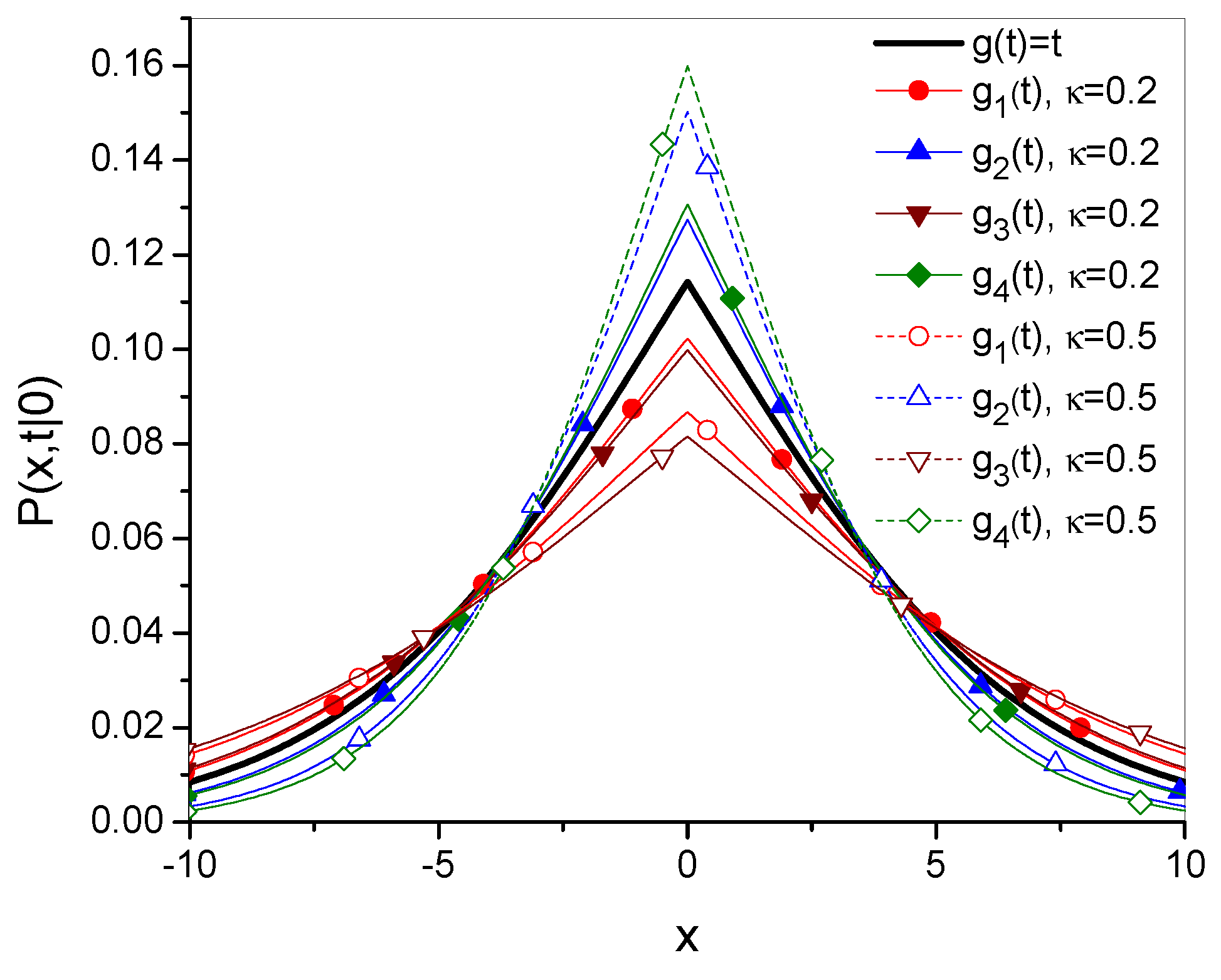

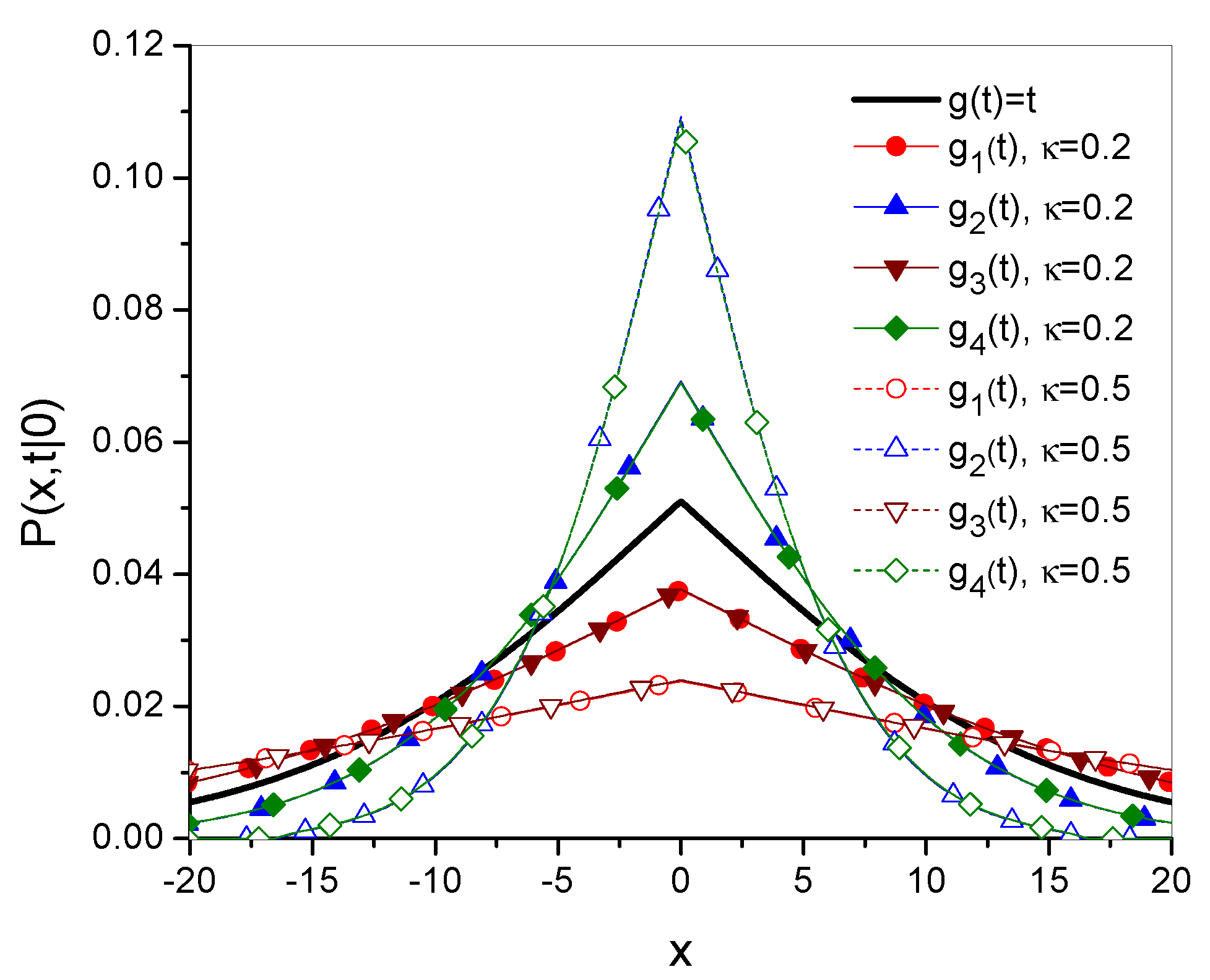

3. Time Evolution of as a Function Defining the Diffusion Process

- Forwe have

- Whenwe get

- Whenthere is

- Forwe get

4. Final Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montroll, E.W.; Weiss, G.H. Random walks on lattices II. J. Math. Phys. 1965, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, R.; Klafter, J. The random walk’s guide to anomalous diffusion: a fractional dynamics approach. Phys. Rep. 2000, 339, 1–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compte, A. Stochastic foundations of fractional dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 1996, 53, 4191–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klafter, J.; Sokolov, I.M. First step in random walks. From tools to applications. Oxford UP, New York, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Barkai, E.; Metzler, R.; Klafter, J. From continuous time random walks to the fractional Fokker-Planck equation. Phys. Rev. E 2000, 61, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchaud, J.P.; Georgies, A. Anomalous diffusion in disordered media: statistical mechanisms, models and physical applications. Phys. Rep. 1990, 195, 127–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, R.; Klafter, J. The restaurant at the end of the random walk: recent developments in the description of anomalous transport by fractional dynamics. J. Phys. A 2004, 37, R161–R208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztołowicz, T.; Dworecki, K.; Mrówczyński, S. How to measure subdiffusion parameters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 170602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztołowicz, T.; Metzler, R. Diffusion of antibiotics through a biofilm in the presence of diffusion and absorption barriers. Phys. Rev. E bf 2020, 102, 032408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztołowicz, T.; Metzler, R.; Wa̧sik, S.; Arabski, M. Modelling experimentally measured of ciprofloxacin antibiotic diffusion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formed in artificial sputum medium. PLoS One 2020, 15(12), e0243003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redner, S. Superdiffusive transport due to random velocity fields. Physica D: Nonlin. Phenom. 1989, 38, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumofen, G.; Klafter, J.; Blumen, A. Enhanced diffusion in random velocity fields. Phys. Rev. A 1990, 42, 4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchaud,J. P.; Georges, A.; Koplik, J.; Provata, A.; Redner, S. Superdiffusion in random velocity fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1990, 64, 2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compte, A.; Cáceres, M. O. Fractional dynamics in random velocity fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 81, 3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieterich, P.; Klages, R.; Preuss, R.; Schwab, A. Anomalous dynamics of cell migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverey, J. F.; Jeon, J. H.; Bao, H.; Leippe, M.; Metzler, R.; Selhuber–Unkel, C. Superdiffusion dominates intracellular particle motion in the supercrowded cytoplasm of pathogenic Acanthamoeba castellanii. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager, M.; Weissing, F. J.; Herman, P. M. J.; Nolet, B. A.; van de Koppel, J. Lévy walks evolve through interaction between movement and environmental complexity. Science 2011, 332, 1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztołowicz, T. Subdiffusion equation with fractional Caputo time derivative with respect to another function in modeling transition from ordinary subdiffusion to superdiffusion. Phys. Rev. E 2023, 107, 064103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztołowicz, T. Subdiffusion Equation with Fractional Caputo Time Derivative with Respect to Another Function in Modeling Superdiffusion. Entropy 2025, 27, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorbist, B.; Soonsin, V.; Luo, B.P.; Krieger, U.K.; Marcolli, C.; Peter, T.; Koop, T. Ultra-slow water diffusion in aqueous sucrose glasses. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 3514. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, H. Empirical observations of ultraslow diffusion driven by the fractional dynamics in languages, Phys. Rev. E 2018, 98, 012308. [Google Scholar]

- Chechkin, A.V.; Klafter, J.; Sokolov, I.M. Fractional Fokker-Planck equation for ultraslow kinetics. Europhys. Lett. 2003, 63, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chechkin, A.V.; Kantz, H.; Metzler, R. Ageing effects in ultraslow continuous time random walks. Eur. Phys. J. B 2017, 90, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, S.I.; Kantz, H. Continuous-time random walk with a superheavy-tailed distribution of waiting times. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 83, 041132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denisov, S.I.; Yuste, S.B.; Bystrik, Yu.S.; Kantz, H.; Lindenberg, K. Asymptotic solutions of decoupled continuous-time random walks with superheavy-tailed waiting time and heavy-tailed jump length distributions. Phys. Rev. E 2011, 84, 061143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztołowicz, T. Subdiffusive random walk in a membrane system. J. Stat. Mech. P 2015, 10021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, L.P.; Lomholt, M.A.; Lizana, L.; Fogelmark, K.; Metzler, R.; Abjörnsson, T. Severe slowing-down and universality of the dynamics in disordered interacting many-body systems: ageing and ultraslow diffusion. New J. Phys. 2014, 16, 113050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodrova, A.S.; Chechkin, A.V.; Cherstvy, A.G. and Metzler, R. Ultraslow scaled Brownian motion. New J. Phys. 2015, 17, 063038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. L.; Libchaber, A. Particle diffusion in a quasi-two-dimensional bacterial bath. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, A.; Konya, A.; Wang, F.; Selinger, J. V.; Sun, K.; Wei, Q. H. Brownian motion of boomerang colloidal particles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 111, 160603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A.; Granek, R.; Elbaum, M. Enhanced diffusion in active intracellular transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 85, 011916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J. H.; Tejedor, V.; Burov, S.; Barkai, E.; Selhuber-Unkel, C.; Berg-Sørensen, K.; Oddershede, L.; Metzler, R. In vivo anomalous diffusion and Weak ergodicity breaking of lipid granules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 048103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miño, G.; Mallouk, T. E.; Darnige, T.; Hoyos, M.; Dauchet, J.; Dunstan, J.; Soto, R.; Wang, Y.; Rousselet, A.; Clement, E. Enhanced diffusion due to active swimmers at a solid surface. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 106, 048102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bechinger, C.; Di Leonardo, R.; Löwen, H.; Reichhard, C.; Volpe, G.; Volpe, G. Active particles in complex and crowded environments. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 045006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Yang, Q.; Wang, X.; Peng, X.; Qin, F. Review of Prediction Models for Chloride Ion Concentration in Concrete Structures. Buildings 2025, 15, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luping, T; Nilsson, L. O. Chloride diffusivity in high strength concrete at different ages. Nord. Concr. Res. 1992, 11, 162–171. [Google Scholar]

- Lomholt, M. A.; Lizana, L.; Metzler, R.; Ambjornsson, T. Microscopic origin of the logarithmic time evolution of aging processes in complex systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013, 110, 208301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherstvy, A. G.; Safdari, H.; Metzler, R. Anomalous diffusion, nonergodicity, and ageing for exponentially and logarithmically time-dependent diffusivity: striking differences for massive versus massless particles. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 195401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, D. S.; Fieremans, E.; Jespersen, S. N.; Kiselev, V. G. Quantifying brain microstructure with diffusion MRI: theory and parameter estimation NMR. Biomed, 3998; 32. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H-H. ; Papaioannou, A.; Kim, S-L.; Novikov D. S.; Fieremans, E. Probing axonal swelling with time dependent diffusion MRI Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 354.

- Anderson, G.G.; O’Toole, G.A. Bacterial Biofilms. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology 2008, 322, p–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, T.F.C.; O’Toole, G.A. Mechanisms of biofilm resistance to antimicrobial agents. Trends Microbiol. 2001, 9, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J. D. Time-Dependent Fractional Diffusion and Friction Functions for Anomalous Diffusion. Front. Phys. 5671; :61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. G.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y. Variable-order fractional differential operators in anomalous diffusion modeling. Physica A 2009, 388, 4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. G.; Chen, W.; Sheng, H.; Chen, Y. On mean square displacement behaviors of anomalous diffusions with variable and random orders. Phys. Lett. A 2010, 374, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. G.; Chen, W.; Li, C.; Chen, Y. Finite difference schemes for variable-order time fractional diffusion equation. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos 2012, 22, 1250085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. A variable-order time-fractional derivative model for chloride ions sub-diffusion in concrete structure. Fract. Calc. Appl. Analys. 2013, 16, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H. G.; Chang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W. A review on variable-order fractional differential equations: Mathematical foundations, physical models, and its applications. Frac. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2019, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Wang, H. A variably distributed-order time-fractional diffusion equation: Analysis and approximation. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Engrg. 2020, 367, 113118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Zhou, Z.; Magin, R. L. A survey of models of ultraslow diffusion in heterogeneous materials. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2019, 71, 040802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, P.; Sokolov, I. M. Inhomogeneous parametric scaling and variable-order fractional diffusion equations. Phys Rev. E 2020, 102, 012133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, E.; Sandev, T.; Metzler, R.; Chechkin, A. Closed-form multi-dimensional solutions and asymptotic behaviors for subdiffusive processes with crossovers: I. Retarding case. Chaos Solit. Fract. 2021, 152, 111357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, E.; Metzler, R. Crossover dynamics from superdiffusion to subdiffusion: Models and solutions. Frac. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2020, 23, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S.; Hollkamp, S.; Semperlotti, J. P. Applications of variable-order fractional operators: a review. Proc. R. Soc. A 2020, 476, 20190498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedotov, S.; Han, D. Asymptotic behavior of the solution of the space dependent variable order fractional diffusion equation: ultraslow anomalous aggregation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 123, 050602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazhlekova, E. Completely monotone multinomial Mittag–Leffler type functions and diffusion equations with multiple time-derivative. Frac. Calc. Appl. Analys. 2021, 24, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztołowicz, T.; Dutkiewicz, A. Subdiffusion equation with Caputo fractional derivative with respect to another function. Phys. Rev. E 2021, 104, 014118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztołowicz, T.; Dutkiewicz, A. Stochastic interpretation of g-subdiffusion process. Phys. Rev. E 2021, 104, L042101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R. A Caputo fractional derivative of a function with respect to another function. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simulat. 2017, 44, 460–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarad, F.; Abdeljawad, T. Generalized fractional derivatives and Laplace transform. Discrete And Continuous Dynamical Systems Series S 2020, 13, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarad, F.; Abdeljawad, T.; Rashid, S.; Hammouch, Z. More properties of the proportional fractional integrals and derivatives of a function with respect to another function. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2020, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztołowicz, T. From the solutions of diffusion equation to the solutions of subdiffusive one. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 2004, 37, 10779–10789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahad, H.M.; Rehman, M.; Fernandez, A. On Laplace transforms with respect to functions and their applications to fractional differential equations. Math Meth. Appl Sci. 2021, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M. Resampling single-particle tracking data eliminates localization errors and reveals proper diffusion anomalies. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 100, 042125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalet, X.; Berglund A., J. Optimal diffusion coefficient estimation in single-particle tracking. Phys. Rev. E 2012, 85, 061916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kepten, E.; Bronshtein, I.; Garini, Y. Improved estimation of anomalous diffusion exponents in single-particle tracking experiments. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 87, 052713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, M. L. P.; Yan, H.; Surovtsev, I.; Williams J., F.; King M., C.; Mochrie S. G., J. Covariance distributions in single particle tracking. Phys. Rev. E 2021, 103, 032405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosztołowicz, T.; Dutkiewicz, A.; Lewandowska, K. D.; Wa̧sik, S.; Arabski, M. Subdiffusion equation with Caputo fractional derivative with respect to another function in modelling diffusion in a complex system consisting of matrix and channels. Phys. Rev. E 2022, 106, 044138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybiec, B.; Gudowska–Nowak, E. Discriminating between normal and anomalous random walks. Phys. Rev. E 2009, 80, 061122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).