1. Introduction

In Nigeria, sandcrete blocks are the predominant walling material but remain largely unaffordable for many. Their inconsistent quality and substandard performance across manufacturers have raised concerns, as commercial blocks frequently fall below regulatory benchmarks. As highlighted by Ubi et al. [

1], even the most lenient cement mix ratios are often disregarded in practice. In contrast, burnt bricks typically exceed strength requirements and offer a cheaper alternative, positioning them as a potentially more sustainable solution for affordable housing.

The Otukpo Burnt Brick Factory, once a symbol of industrial promise, has remained dormant since the 1990s despite repeated revival efforts [

2,

3].

Figure 1 depicts what is left of it. In response to this context, the present exploratory study seeks more sustainable and culturally resonant alternatives, specifically, the utilization of local soil to produce minimally processed, uncalcined mud bricks (unfired bricks), and to assess its potential as a natural pozzolan for the development of supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). The overarching aim is to reduce reliance on conventional cement in construction, lower environmental impact, cut production costs, and promote Indigenous building traditions.

The growing demand for sustainable building materials has prompted a re-evaluation of legacy soil samples, particularly those historically used for burnt brick production. In Nigeria’s Benue Valley, traditional brickmaking has long relied on locally sourced clayey soils and rudimentary firing methods. While economically viable, these practices raise environmental concerns and yield inconsistent product quality, similar to issues observed with sandcrete blocks.

Burnt bricks, valued for durability and thermal insulation [

4], require high-temperature firing, often using firewood—raising sustainability concerns. Alternatives that minimize energy use and leverage pozzolanic reactions offer a low-carbon path forward [

5]. Pozzolans, though not cementitious on its own, react with calcium hydroxide in the presence of water to form cementitious compounds such as calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) and calcium aluminate hydrate (C–A–H) [

6]. Materials like fly ash, calcined clays, and volcanic ash are common, but recent studies show that natural soils rich in SiO

2, Al

2O

3, and Fe

2O

3 can serve as supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) [

7]. Nigerian clays often contain kaolinite and goethite, suggesting pozzolanic potential [

8], though activation - mechanical, thermal, or chemical - is typically required [

9]. Even uncalcined kaolinitic clays, when finely ground, show reactivity in cement systems [

10].

Sandcrete blocks often fail to meet Nigerian Industrial Standard - NIS 87:2007 [

31], which require a minimum UCS of 2.5 N/mm

2 for non-load-bearing blocks [

11]. Stabilization using minimal cement or alkali activators has shown promise. Locally produced burnt bricks in Makurdi, Benue State, exhibited strengths of 3.46 and 11.75 N/mm

2, water absorption of 8.58% and 16.49%, and abrasion resistance of 9.32 and 33.67, respectively [

12]. These bricks were significantly more cost-efficient than sandcrete blocks, which typically range from 0.5 to 1 N/mm

2 [

11,

12]. Despite these advantages, further research is needed to improve firing methods and reduce environmental degradation.

Legacy soils from Otukpo and Makurdi often possess mineralogical profiles conducive to pozzolanic reactivity [

12] yet remain under-assessed for SCM applications. Re-evaluating these soils supports both local traditions and global sustainability goals. The prolonged dormancy of the Otukpo Burnt Brick Factory—inactive for over three decades—underscores the need for community-driven alternatives [

13]. Reviving brick production through low-energy methods like uncalcined bricks or SCMs could stimulate employment and meet rising construction demands.

Traditional earthen materials vary widely in composition and require tailored characterization for mainstream use [

14]. Their compressive strength ranges from 0.49 to 4.90 N/mm

2, often below code requirements. Moisture ingress and rainfall pose additional challenges, necessitating stabilization. Mechanical, thermal, and chemical activation methods have been explored [

9], with chemical activation shown to enhance pozzolanic reactivity. Reactivity is influenced by mineralogy and specific surface area (SSA), where higher SSA can improve strength [

15]. Uncalcined clays offer sustainable potential but may absorb water excessively, affecting long-term performance [

15].

SCMs are increasingly used to reduce cement’s environmental footprint [

16]. These include natural pozzolans and industrial by-products like fly ash, silica fume, metakaolin, and GGBFS [

7]. In tropical regions, clay-derived SCMs are especially relevant. Their filler effect accelerates hydration and improves durability. In Chile, most of the cement production uses Portland-pozzolan cement with natural pozzolans that are readily available [

5]. Research shows that calcining kaolinite at 700 °C for 1 hour yields high-quality SCMs, though energy-intensive. Following ASTM C618-12 [

6], Class N natural pozzolans must meet key criteria including SiO

2 + Al

2O

3 + Fe

2O

3 ≥ 70%, SO

3 ≤ 4%, and a Strength Activity Index (SAI) ≥ 75% at 28 days, among other chemical and physical requirements [

6,

7].

SCM reactivity depends on composition, fineness, glass content, pH, and hydration kinetics [

15,

17]. In soil stabilization, strength development is driven by cement hydration (C

2S, C

3S) and pozzolanic reactions involving Ca(OH)

2 [

18,

19].

2. Materials and Methods

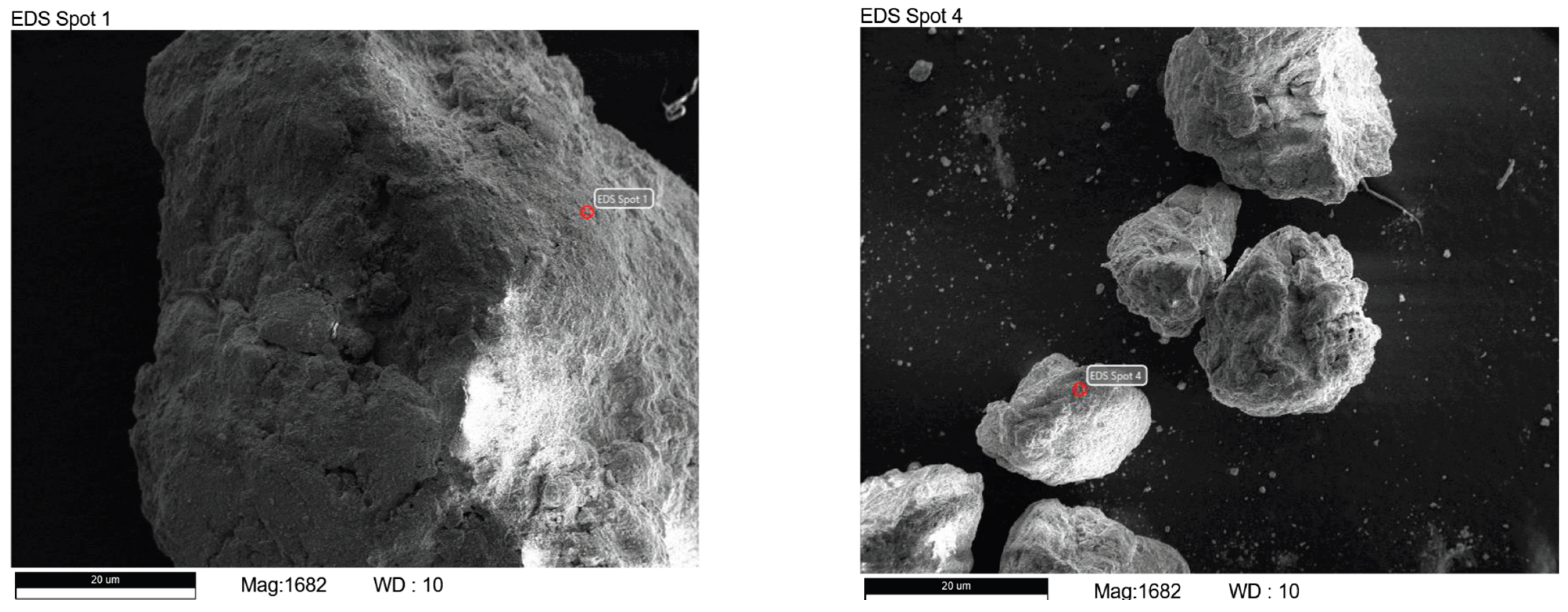

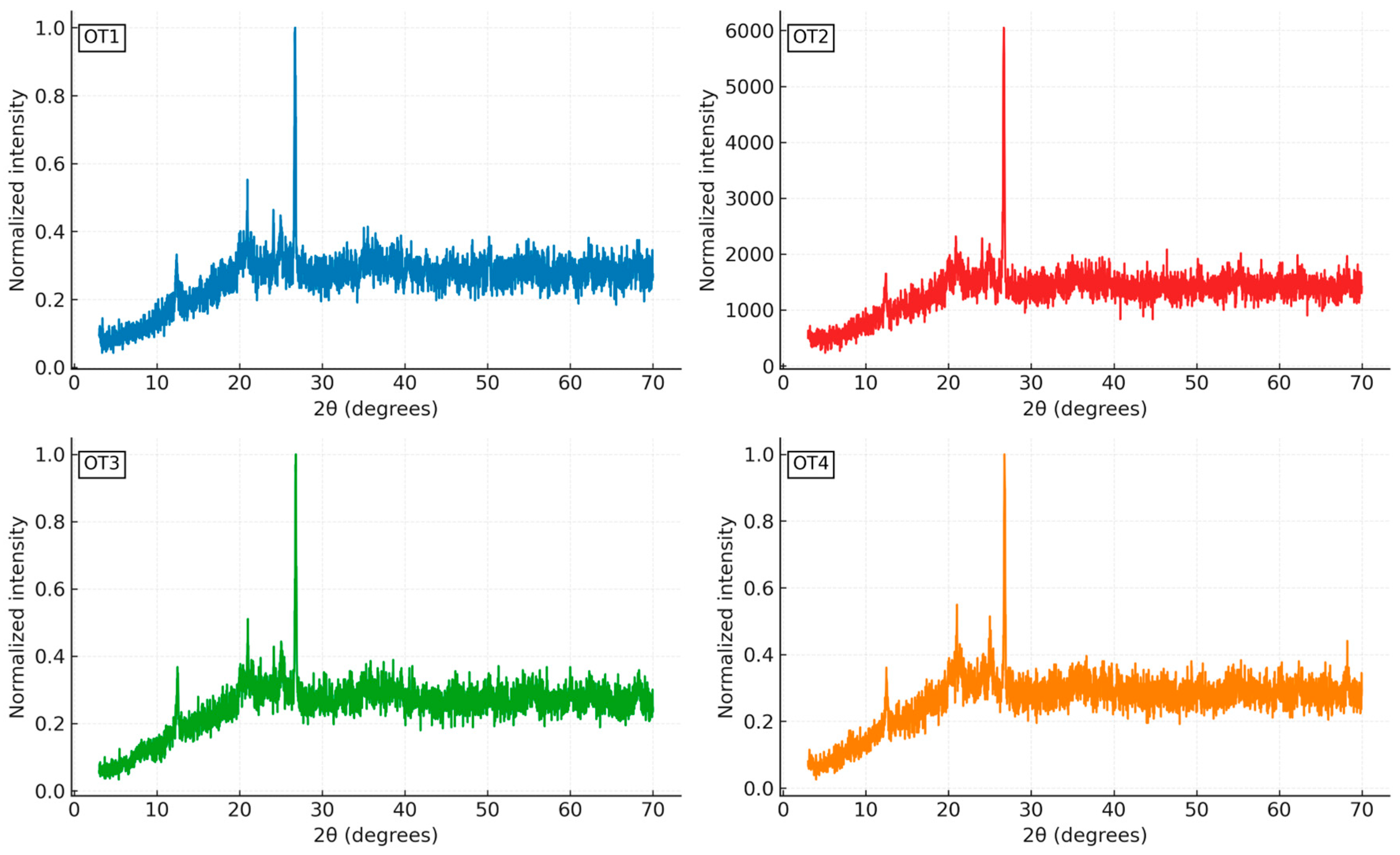

To characterize Otukpo soils, this study applied techniques such as X-ray fluorescence (XRF) for elemental and oxide composition, X-ray diffraction (XRD) for mineral phase identification [

20], scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for microstructural analysis [

21], thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) for thermal behavior, and particle size distribution (PSD) for granulometry [

22]. Unconfined compressive strength (UCS) and cube compressive strength tests were conducted to evaluate stabilization performance and early-age mechanical behavior. Additional pozzolanicity indicators such as strength activity index (SAI), differential thermogravimetry (DTG), fixed lime strength activity test (FAST), Frattini test, and the rapid, relevant, and reliable (R3) reactivity test may also be used [

23,

24]. However, because this exploratory study is self-funded, the number and extent of the tests conducted were constrained by available funds. Furthermore, the sequence of tests was conducted so as so check conformance to ASTM C618 [

6] as well as the requirements for brick in NIS 87: 2007 [

31] and Nigerian Building Code – NBC [

34].

2.1. Lab Strategy

Chemical, thermal, physical, and mechanical tests were conducted across multiple laboratories at Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria. Specifically, XRD, XRF, and SEM analyses and TGA were performed at the university’s diffractometry laboratory [

25,

26], while all other tests were conducted at the Geotechnical Engineering and Concrete Laboratories of the Civil Engineering Department. Due to scheduling constraints and for cross-verification purposes, OT2 samples were tested at Goe-Works and Engineering Services Limited, a private laboratory based in Abuja. The Scanning Electron Microscopic (SEM) test was conducted at the Nigeria Bridge, Roads and Research Institute (NBRRI), Abuja as they were the only one with a functioning equipment at the time.

2.2. Sample Collection and Preparation

4 sets of representative soil samples were collected from the borrow pits of the defunct Benue Burnt Bricks Factory in Otukpo, and labelled OT1 to OT4 as shown on

Table 1. They were collected below the topsoil horizon at a depth of ~ 2ft to eliminate organic materials. Cement used for this study were Portland limestone cement with product designation SOKCEM II-42.5N for normal or general-purpose use, manufactured by BUA Cement at their Plant in Sokoto State, Nigeria, manufactured in accordance with NIS 444 [

31].

The soil samples were initially air-dried and ground to reduce size, then oven-dried at 105 ± 5 °C for 24 hours to eliminate residual moisture. The dried clods were gently pulverized using a wooden mallet and sieved to pass through a 2 mm mesh for geotechnical testing and a 75 µm mesh for chemical and mineralogical analyses.

2.3. XRD, XRF, SEM, and TGA Tests

XRD analysis was conducted using a Rigaku MiniFlex benchtop system to identify the mineral phases the soil samples. Prior to analysis, samples were oven-dried at 100 °C for 24 hours to eliminate moisture, ground to a particle size of less than 75 µm for consistency, sieved for uniformity, centrifuged to isolate the clay fraction, and oriented mounts were prepared for clay-specific evaluation. These procedures followed ASTM E691 - Standard Practice for Conducting an Interlaboratory Study to Determine the Precision of a Test Method [

6], along with related sample handling protocols, using approximately 1.5 grams of material per test. The diffraction analysis employed Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.54056 Å), and scans were performed over a 2θ range of 3.00° to 70.00° at 0.02° intervals, enabling high-resolution peak detection as described by Moussa et al. [

26]. Resulting spectra were matched against the International Centre for Diffraction Data – Powder Diffraction File (ICDD PDF-2) database, and semi-quantitative phase estimation was performed using peak area normalization.

The chemical composition of the untreated soil samples was determined using the Xenemetrix Genius IF (Secondary Targets) Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence (EDXRF) spectrometer. Sample preparations were similar to XRD. Prior to analysis, the powders were pressed into 40 mm diameter pellets using an inert binder at a 5:1 ratio; approximately 5 g of sieved powder was compacted with a hydraulic press and placed into the spectrometer chamber for elemental and oxide analysis via X-ray excitation. The pozzolanicity index was assessed in accordance with ASTM C618, and each analysis was performed in duplicate for quality assurance.

SEM was conducted using the Oxford PhenomProX system, which provided a high-resolution imaging to examine soil microstructure, particle morphology, and mineral bonding, particularly in samples with distinct mineralogical features. TGA was performed using the PerkinElmer MES-TGA TGA4000 system (Netherlands), which measures thermal decomposition and weight loss under controlled heating to identify moisture content, organic matter, mineral stability, and loss on ignition (LOI). As different materials decompose at characteristic temperatures, TGA provides insight into compositional changes and thermal behavior.

2.3. Geotechnical and Mechanical Tests

For the particle size distribution, both dry and sedimentation analysis were done to adequately capture the full range of particle sizes per the requirements of ASTM D 6913 - Standard Test Method for Particle Size Distribution (Gradation) of Soils using Sieve Analysis [

6]. For the Atterberg limits and related tests, ASTM D 4318 - Standard Test Method for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils in conjunction with ASTM D 698 - Standard Test Method for Laboratory Compaction Characteristics of Soil [

6].

Figure 2 is depictive of hydrolysis, stabilizer mixing operation, and compaction.

Stabilized formulations were prepared by dry mixing the processed soil with 5 wt.% cement or 5 wt.% sodium hydroxide (NaOH) as shown in

Figure 2, followed by the addition of water corresponding to the optimum moisture content (OMC) as determined from Proctor compaction tests. For the strength tests, to ensure repeatability and statistical reliability, three replicate specimens (n = 3) were produced for each test condition for UCS and cube strength evaluations. The UCS tests were conducted using a Load Frame machine in accordance with BS 1377-7:1990 – Methods of Test for Soils for Civil Engineering Purposes, Part 7: Shear Strength Tests (Total Stress Condition) [

33] and ASTM D2166/D2166M-13 – Standard Test Method for Unconfined Compressive Strength of Cohesive Soil [

6]. Cube specimens measuring 70.6 mm were used, based on the available moulds. These conform to IS 4031-6:1988 – Methods of Physical Tests for Hydraulic Cement, Part 6: Determination of Compressive Strength and IS 10080:1982 – Specification for Vibration Machine for Cement Mortar Cubes [

32], which provide standardized procedures for compressive strength testing of cementitious materials. The setup also aligns with BS 1881-116:1983 – Testing Concrete, Method for Determination of Compressive Strength of Concrete Cubes [

33], which specifies a minimum cube dimension of 70.7 mm and is considered acceptable for stabilized soil evaluation. Additionally, ASTM C109/C109M-21 – Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Hydraulic Cement Mortars (Using 2-in. or 50 mm Cube Specimens) was adapted to accommodate the larger 70.6 mm specimens, with consistent loading rates and curing protocols applied.

Figure 3 shows the cube strength tests being executed [

6].

The pH of the soil samples presented in

Table 1 was determined by dissolving 2 g of each sample in distilled water, followed by thorough mixing. The suspension was left to stand undisturbed for approximately 30 minutes, then stirred again to ensure homogeneity. The mixture was subsequently filtered through standard filter paper, and the pH of the filtrate was measured using a calibrated pH meter. The resulting values, expressed in standard pH units (±0.1), reflect the acidity or alkalinity of the soil samples under laboratory conditions.

2.4. Water Absorption Test

The water absorption test was conducted to evaluate the susceptibility of unsaturated lateritic soil to moisture ingress, a key factor in assessing durability under environmental exposure. Specimens were cured in open air for 28 days, following the benchmark outlined in BS 1881-122:1983 – Testing Concrete, Method for Determination of Water Absorption [

33], and adopted by Nigerian Industrial Standards (NIS 586:2007 [

31]) and the NBC [

34]. After curing, each cube was oven-dried at 105 °C to constant mass, cooled, and weighed to obtain the dry mass (Md). Each sample was then submerged in clean water for 24 hours to reach a saturated surface-dry (SSD) condition. After gently blotting off surface moisture, the SSD mass was recorded. Water absorption was calculated using: Water Absorption (%) = (SSD mass − Dry mass)/Dry mass × 100.

Although no dedicated standards exist for lateritic soils, this procedure was adapted from ASTM C127 – Standard Test Method for Relative Density and Absorption of Coarse Aggregate, ASTM C128 – Standard Test Method for Relative Density and Absorption of Fine Aggregate, and ASTM C1585 – Standard Test Method for Measurement of Rate of Absorption of Water by Hydraulic-Cement Concretes [

6], as well as BS EN 1097-6:2013 – Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates, Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption [

33]. These standards ensure methodological consistency while accommodating the unique characteristics of tropical soils.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Otukpo soils, particularly areas where OT3 and OT4 were collected, which was within the vicinity of the defunct Benue Burnt Bricks, possess favorable pozzolanic and mechanical characteristics suitable for use in low-energy (unfired) brick production and as supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) (given their relatively high kaolinite content). Their high reactive oxide contents, moderate loss-on-ignition values, and strong response to cement and alkaline activation confirm their suitability for sustainable construction applications within the Benue region and similar lateritic environments.

Although water absorption and shrinkage data suggest improved dimensional stability, especially in cement-stabilized samples, they do not fully capture the swelling behavior of clay-rich soils. Future research should address this behavior and examine how activation strategies affect long-term volumetric stability. These studies should also assess durability under varied environmental and loading conditions, including the potential benefits of mechanochemical activation. A combined approach involving mineralogical, chemical, and microstructural analyses (before and after treatment), specific surface area measurements, and standardized strength tests over extended curing is recommended. In parallel, regional quality frameworks and the incorporation of Agro-waste ashes like rice husk ash could further enhance strength and durability.

Emerging alternatives like Limestone Calcined Clay Cement (LC3), which utilize abundant clay minerals and require lower calcination temperatures, offer promising low-carbon pathways for binder optimization. Establishing such evidence-based standards will reinforce confidence in earthen construction, promote adoption by government and private-sector stakeholders, and advance decentralized, community-driven production models across the Benue Valley and similar regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.; methodology, J.A.; validation, S.O., O.O.; formal analysis, J.A.; investigation, J.A.; resources, J.A.; data curation, J.A.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.; writing—review and editing, S.O.; visualization, J.A.; supervision, S.O., O.O.; project administration, J.A.; funding acquisition, J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.