1. Introduction

Bronchial asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways involving various cells and cellular components, with its global prevalence continuing to rise, posing a significant public health challenge [

1,

2]. Clinically, asthma is characterized by recurrent episodes of wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and coughing, resulting from reversible airflow limitation, which severely impacts patients' quality of life and can be life-threatening during severe acute exacerbations [

3]. The pathophysiological core of asthma lies in an abnormal immune response within the airways, leading to a state of persistent inflammation. This inflammation not only induces bronchospasm, causing airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), but also drives pathological airway remodeling with disease progression, including epithelial injury, mucus gland hyperplasia, and excessive extracellular matrix deposition, which can ultimately lead to permanent lung function impairment [

4,

5].

Allergic asthma, the most common asthma phenotype, is closely associated with a type II immune response in its pathogenesis [

6]. Upon exposure to allergens (such as dust mites, pollen, animal dander, or the experimentally used ovalbumin, OVA) in genetically predisposed individuals, antigen-presenting cells present allergen information to naive T cells, inducing their differentiation into Th2-type helper T cells. Activated Th2 cells act as the "commanders" driving allergic inflammation, orchestrating downstream immune responses through the secretion of a series of hallmark cytokines [

7]. Among these, interleukin-4 (IL-4) is critical for initiating and maintaining the Th2 response, inducing B-lymphocyte class switching to produce large amounts of allergen-specific IgE antibodies. These IgE antibodies bind to high-affinity receptors (FcεRI) on the surface of mast cells and basophils, sensitizing the host [

8]. Upon re-exposure to the same allergen, IgE cross-linking rapidly triggers degranulation of these effector cells, releasing early-phase mediators like histamine and leukotrienes, which cause bronchoconstriction. Concurrently, interleukin-5 (IL-5), secreted by Th2 cells, is the core cytokine responsible for the generation, mobilization, recruitment to the airways, and prolonged survival of eosinophils [

9]. The infiltration and activation of a large number of eosinophils in the airways, which release cationic proteins and peroxidases from their granules, directly damage the airway epithelium and are the main cause of the late-phase inflammation and AHR in asthma. Furthermore, interleukin-13 (IL-13) has functions that partially overlap with IL-4 but plays a more direct and significant role in inducing AHR, promoting goblet cell metaplasia and mucus hypersecretion, and driving airway fibrosis and remodeling [

10]. Therefore, IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 collectively form the "cytokine triad" that drives the pathological process of allergic asthma, and effectively inhibiting this inflammatory axis is a central goal of current asthma therapies.

At the molecular signal transduction level, the initiation and maintenance of the inflammatory response are governed by a network of precisely regulated signaling pathways. Among them, the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway is considered the "central hub" of inflammatory responses [

11]. In a resting state, the NF-κB dimer (typically p65/p50) is bound to the inhibitory protein IκBα and anchored in the cytoplasm. Various pro-inflammatory stimuli, including pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), and upstream inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α), can activate the IκB kinase (IKK) complex. Activated IKK phosphorylates IκBα, leading to its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This frees NF-κB to rapidly translocate into the nucleus, bind to κB sites in the promoters of target genes, and initiate the transcription of over 500 downstream genes [

12]. These target genes encode a vast array of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, acute-phase proteins, and immune receptors, thereby forming a powerful positive feedback loop that drives and sustains the inflammatory state. In the pathology of asthma, various stimuli, including allergen exposure, viral infections, or environmental pollutants, often converge on the aberrant activation of the NF-κB pathway. Numerous studies have detected persistent NF-κB activation in the bronchial epithelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and infiltrated immune cells of asthma patients [

13,

14], making it a highly attractive therapeutic target for anti-asthma treatment.

However, the body also possesses potent endogenous anti-inflammatory mechanisms to prevent excessive and uncontrolled inflammatory responses. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) is one such key negative regulatory molecule [

15]. SIRT1 is an NAD+-dependent class III histone/non-histone deacetylase that plays a central regulatory role in multiple processes, including energy metabolism, cellular stress, aging, and longevity [

16]. In the field of inflammation regulation, SIRT1 is regarded as an "inflammatory brake." Its most classic anti-inflammatory mechanism is the direct inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. Studies have confirmed that SIRT1 can interact with the p65 subunit of NF-κB in the nucleus and catalyze the deacetylation of its lysine 310 residue [

17]. Acetylation of p65 is necessary for its full transcriptional activity, and deacetylation significantly reduces its DNA-binding ability and promotes its nuclear export, thereby effectively "switching off" the pro-inflammatory function of NF-κB [

18]. In addition to NF-κB, SIRT1 can also inhibit inflammation by deacetylating other transcription factors such as AP-1 and STAT3. In various acute and chronic inflammatory disease models, including arthritis, atherosclerosis, neuroinflammation, and inflammatory bowel disease, upregulating SIRT1 activity through pharmacological activators (like resveratrol) or genetic means has demonstrated significant therapeutic effects [

19]. Notably, previous studies have reported that both the expression level and enzymatic activity of SIRT1 are significantly reduced in the lung tissues of asthma patients and animal models [

20], suggesting that impaired SIRT1 function may be a critical intrinsic factor for the persistence of asthma inflammation. Therefore, exploring new methods to safely and effectively restore or enhance endogenous SIRT1 function is of great theoretical and practical significance for developing new therapeutic strategies for asthma.

In recent years, with the deepening of interdisciplinary research in neuroscience and immunology, the concept of the "neuro-immune axis" has provided a new dimension for understanding and intervening in chronic inflammatory diseases [

21]. The lung, as an organ in direct contact with the external environment, is precisely regulated by a complex autonomic nervous system (ANS), including sympathetic, parasympathetic, and non-adrenergic, non-cholinergic (NANC) nerves. Among these, the sympathetic nervous system plays a dual role in stress responses and immune regulation. The stellate ganglion, the largest and most critical ganglion in the cervical sympathetic chain, gives rise to postganglionic fibers that extensively innervate the heart, lungs, upper limbs, and blood vessels and glands of the head and face [

22]. Clinically, stellate ganglion block (SGB) via chemical agents or radiofrequency has been widely used to treat complex regional pain syndrome, arrhythmias, and certain vascular diseases [

23]. An increasing body of basic research indicates that modulating stellate ganglion function can profoundly affect the inflammatory state of distant organs. For instance, the "cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway" through vagus nerve stimulation is well-known [

24], and modulating the sympathetic nervous system has also shown potent anti-inflammatory potential. SGB has been proven to improve survival rates and alleviate acute lung injury in endotoxemic rats [

25].

Infrared polarized light (IPL) irradiation, a form of photobiomodulation therapy, is a non-invasive physical therapy that uses low-energy photons of specific wavelengths to regulate cellular function [

26]. By being absorbed by photoreceptors in cellular mitochondria (such as cytochrome c oxidase), it can optimize cellular energy metabolism, regulate oxidative stress levels, and activate various signaling pathways, thereby exerting biological effects such as anti-inflammation, analgesia, and promotion of tissue repair [

27]. Applying IPL technology to the surface projection areas of superficial ganglia like the stellate ganglion offers a highly attractive new approach for non-invasive, repeatable, and precise neuromodulation.

Despite the great potential of neuromodulation in the anti-inflammatory field, systematic research on treating asthma by intervening in the stellate ganglion region with IPL has been lacking. Can this intervention effectively inhibit the core pathology of asthma—Th2-type inflammation? What is the breadth and depth of its effects? What is the underlying molecular regulatory network? These are key scientific questions that urgently need to be answered.

To this end, this study established a classic OVA-induced murine model of allergic asthma to systematically address the following questions: (1) To evaluate whether IPL intervention in the stellate ganglion region can effectively ameliorate airway inflammation and pulmonary histopathological features in asthmatic mice, assessed at both phenotypic and molecular levels; (2) To use unbiased, high-throughput transcriptomic technology to comprehensively map the changes in the lung tissue gene expression profile following IPL intervention and to deeply mine its potential signaling pathways and molecular regulatory networks. This study aims to provide solid experimental evidence for neuromodulation-based asthma treatment strategies and to offer new clues for understanding its complex molecular mechanisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals

Specific-pathogen-free (SPF) female BALB/c mice, 6-8 weeks old, weighing 18-22g, were purchased from Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). All mice were housed in a barrier environment facility with ad libitum access to food and water, maintained on a 12h/12h light/dark cycle at a room temperature of 22±2°C and humidity of 50±10%. All animal experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Plastic Surgery Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Approval No: 202403114) and were conducted in strict accordance with the guidelines for the welfare and use of laboratory animals.

2.2. Major Reagents and Instruments

Ovalbumin (OVA, Grade V), aluminum hydroxide, and methacholine (MCh) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Mouse IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 ELISA kits were obtained from Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuhan, China). Trizol reagent was purchased from Invitrogen (USA). Reverse transcription kits and SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix were from Takara (Japan). Rabbit primary antibodies against SIRT1, NF-κB p65, p-NF-κB p65 (Ser536), IκBα, p-IκBα (Ser32), and GAPDH, as well as HRP-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody, were all from Cell Signaling Technology (USA). The infrared polarized light therapy device (wavelength 980nm) was purchased from Zhuangzhi Co. (Beijing, China). The small animal lung function system (FlexiVent) was from SCIREQ (Canada).

2.3. Asthma Model Establishment and Grouping

After a one-week acclimatization period, 45 mice were randomly divided into 3 groups of 15 each: a healthy control group (Control), an OVA model group (OVA), and an SG-IPL treatment group (OVA+SG-IPL).

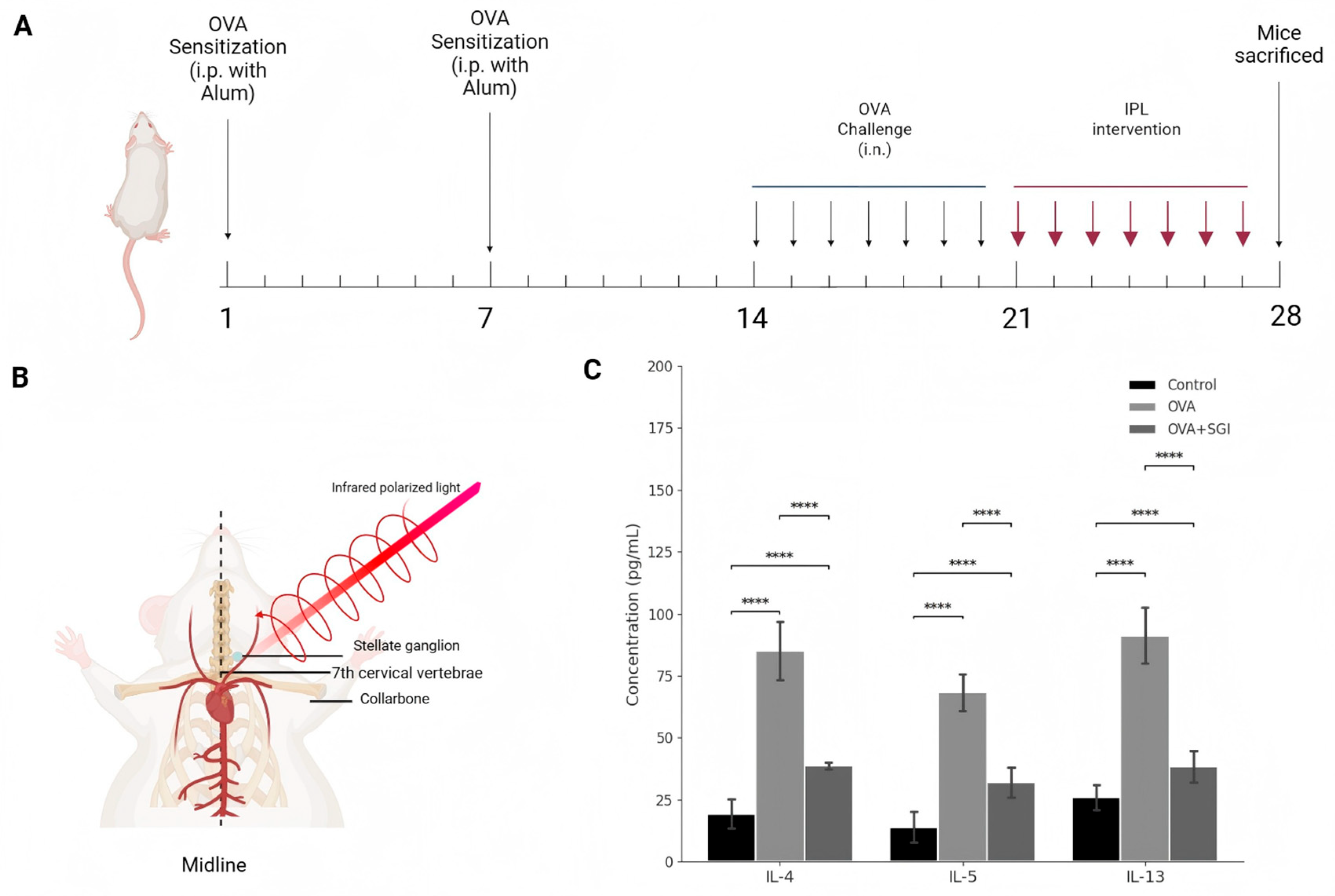

The asthma model was established following a classic method [

23]: On days 0 and 7, mice in the OVA and OVA+SG-IPL groups were sensitized by intraperitoneal injection of 200μL of saline containing 100μg OVA and 2mg aluminum hydroxide. Control group mice received an injection of an equal volume of saline at the same time points. Starting from day 14, for 7 consecutive days, mice in the OVA and OVA+SG-IPL groups were challenged with nebulized 1% OVA in saline solution for 30 minutes each time. Control group mice were nebulized with an equal volume of saline.

2.4. SG-IPL Intervention

Starting from day 14, one hour before the nebulization challenge, mice in the OVA+SG-IPL group received intervention once daily for 7 consecutive days. The mice were first lightly anesthetized with isoflurane and fixed in a supine position. The neck area was exposed and depilated. The junction of the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the superior border of the clavicle, the surface projection area of the stellate ganglion, was located. The probe of the infrared polarized light therapy device was used for irradiation perpendicular to the skin surface. The parameters were set as follows: wavelength 980nm, power 1000mW, pulse frequency 0.5Hz, duty cycle 50%, with 15 minutes of irradiation on each side. Mice in the Control and OVA groups underwent the same anesthesia and fixation procedures at the same time, but with the therapy device turned off (sham irradiation), to control for the effects of handling stress.

2.5. Airway Hyperresponsiveness (AHR) Measurement

AHR was measured 24 hours after the final challenge using the FlexiVent small animal lung function system. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital and fixed in a supine position on a platform. A midline incision was made in the neck to expose the trachea. A small incision was made between the tracheal rings, and a tracheal cannula was inserted and securely ligated. The cannula was connected to a ventilator for mechanical ventilation (frequency 150 breaths/min, tidal volume 10mL/kg). After the mice's breathing stabilized, baseline airway resistance (Rrs) and compliance (Crs) were recorded. Subsequently, saline and increasing concentrations of methacholine (MCh) (3.125, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 mg/mL) were sequentially nebulized for 3 minutes each, and the peak values of Rrs and Crs at each concentration were recorded.

2.6. Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid (BALF) Collection and Analysis

Immediately after AHR measurement, mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. The trachea was exposed, and pre-chilled PBS (0.8mL) was slowly instilled into the lungs. The chest was gently massaged, and the fluid was then slowly withdrawn. This process was repeated 3 times, with a recovery rate of >85%. The collected BALF was centrifuged at 1500rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was collected and stored at -80°C for ELISA. The cell pellet was resuspended in a small amount of PBS, and total cell counts were performed using a hemocytometer. A portion of the cell suspension was used to prepare smears, which were stained with Wright-Giemsa. Two hundred white blood cells were differentially counted under oil immersion to calculate the percentage and absolute numbers of eosinophils, neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages.

2.7. ELISA Assay

The concentrations of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in the BALF supernatant were measured using a double-antibody sandwich ELISA method according to the kit manufacturer's instructions.

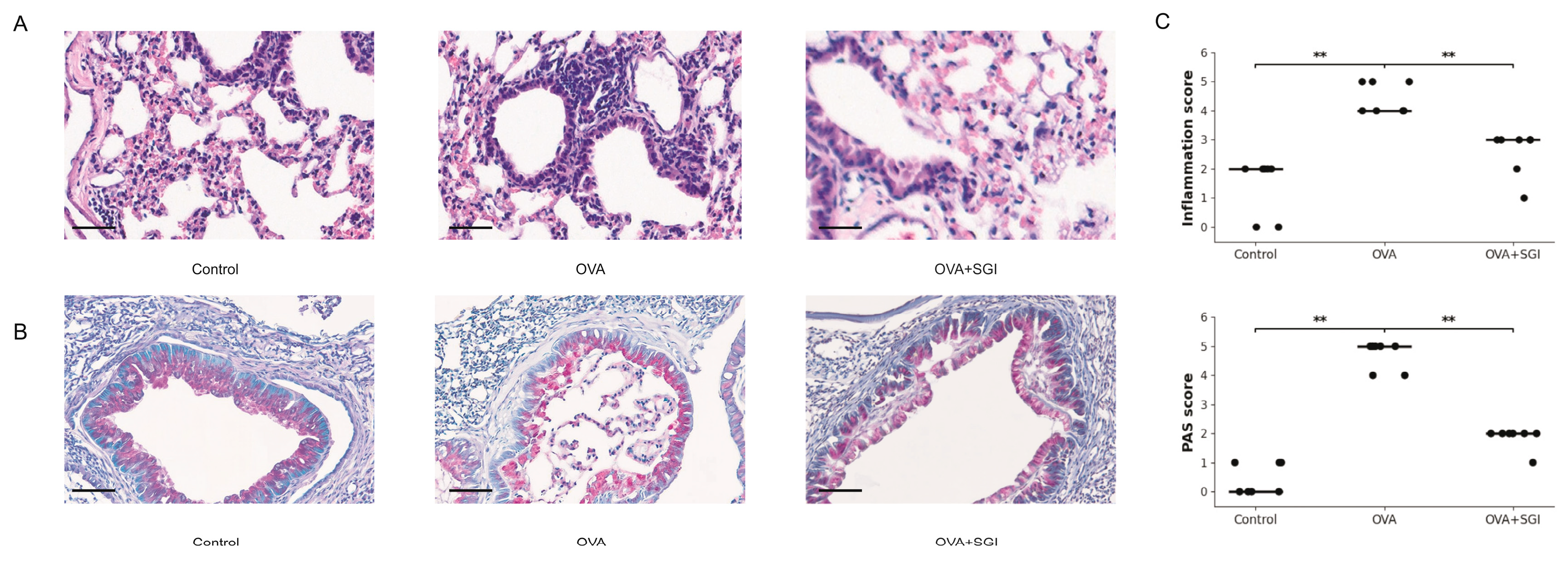

2.8. Lung Histopathological Examination

The upper lobe of the left lung was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 48 hours. After dehydration, clearing, paraffin infiltration, and embedding, 5μm-thick paraffin sections were prepared. Some sections were stained with H&E to observe inflammatory cell infiltration and overall structural changes in the lung tissue. Other sections were stained with PAS to observe goblet cell metaplasia and mucus secretion in the airway epithelium. Images were captured under a light microscope.

2.9. RNA Sequencing and Bioinformatic Analysis

The middle lobe of the right lung was used to extract total RNA using the Trizol method. RNA purity and integrity were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer and an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer. Qualified RNA samples were sent to OE Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for library construction and sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq platform. Raw data were subjected to quality control and filtering, then aligned to the mouse reference genome (GRCm38). Read counts for each gene were calculated using HTSeq software. Differentially expressed gene (DEG) analysis was performed using the DESeq2 package with the criteria of |log2(FoldChange)| > 1 and p-value < 0.05. Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were performed on the DEGs.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. Measurement data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (Mean ± SD). Comparisons between multiple groups were performed using one-way analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA), and pairwise comparisons were made using Tukey's post hoc test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (Note: This is a general description; non-parametric tests were used for the scoring data in

Figure 2C, as indicated in the figure legend.).

4. Discussion

The pathophysiology of bronchial asthma is centered on a self-sustaining cycle of chronic airway inflammation driven by a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental triggers [

1,

2,

22]. Although existing biologics targeting the type II immune response have made significant progress, a considerable number of patients, particularly those with severe asthma, respond poorly to current therapies or have contraindications, highlighting the urgent need for developing novel therapeutic strategies with new mechanisms of action [

21,

23]. This study, grounded in the cutting-edge field of neuro-immune regulation, is the first to systematically evaluate the therapeutic potential of a non-invasive physical intervention—modulating the stellate ganglion (SG) surface region with infrared polarized light (IPL)—in an ovalbumin (OVA)-induced murine model of allergic asthma. Our findings, which integrate histopathology, quantitative analysis of key inflammatory mediators, and unbiased whole-transcriptome analysis, not only provide solid phenotypic evidence for the efficacy of SG-IPL intervention but, more importantly, through deep bioinformatic mining, reveal a potential molecular regulatory framework centered on SIRT1 as an upstream hub for the systemic suppression of downstream inflammatory signaling networks.

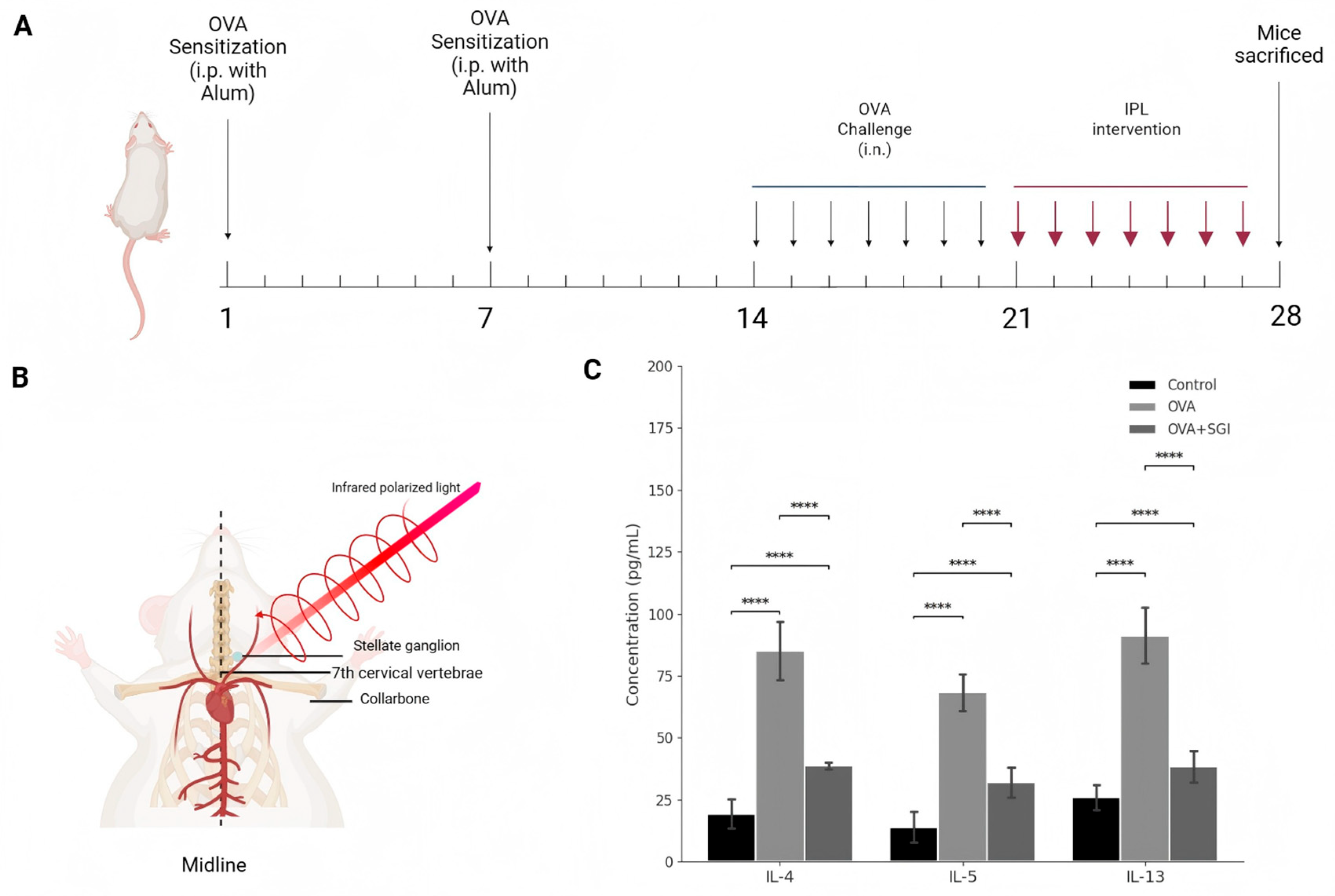

4.1. SG-IPL Intervention Effectively Suppresses Core Pathological Features of Allergic Airway Inflammation

The OVA-induced allergic asthma model successfully established in this study accurately recapitulated the key pathophysiological features of human allergic asthma. As expected, mice in the OVA group exhibited typical overactivation of the type II immune response, with their bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) showing a sharp and statistically highly significant increase in the protein levels of IL-4, a key factor driving Th2 cell differentiation and IgE class switching; IL-5, the core cytokine for eosinophil recruitment and activation; and IL-13, the dominant molecule mediating airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) and mucus secretion (

Figure 1C). This molecular alteration directly led to severe pathological damage at the tissue level. H&E staining clearly showed dense inflammatory cell infiltration around the airways, forming typical "inflammatory cuffs," while PAS staining confirmed significant goblet cell metaplasia and mucus hypersecretion in the airway epithelium (

Figure 2A, 2B).

Against this backdrop, the 7-day SG-IPL intervention demonstrated outstanding therapeutic efficacy. This intervention significantly reversed all the aforementioned pathological indicators. At the molecular level, the concentrations of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in the BALF of the SG-IPL treated mice were robustly suppressed, showing a statistically significant precipitous drop compared to the OVA group (

Figure 1C). This simultaneous suppression of the Th2 "cytokine triad" [

3,

4,

5] suggests that the SG-IPL intervention may not act at the end of the inflammatory cascade but could influence a common upstream regulatory node. This molecular-level improvement translated perfectly into histopathological repair. Semi-quantitative scoring of pathological sections confirmed that SG-IPL intervention significantly reduced the severity of inflammatory infiltration and mucus secretion (

Figure 2C). These phenotypic data collectively form a complete chain of evidence, confirming that SG-IPL, as a non-invasive neuromodulatory tool, can effectively target and inhibit the core pathological processes of allergic asthma. It is noteworthy that while traditional views sometimes suggest that sympathetic activation might exacerbate asthma through β2-adrenergic receptor-mediated promotion of Th2 differentiation [

29], our results show the opposite therapeutic effect. This suggests that the action of IPL on the stellate ganglion is not a simple global "excitation" or "inhibition" but rather a more nuanced "functional reprogramming" or "homeostatic recalibration." Photobiomodulation itself has been shown to exert potent anti-inflammatory and tissue-repair effects by modulating mitochondrial electron transport chain function (e.g., cytochrome c oxidase), optimizing cellular energy metabolism (ATP production), and regulating the intracellular redox state [

15,

26,

28]. Therefore, a plausible hypothesis is that IPL, by acting on the neurons of the stellate ganglion, may alter their metabolic activity and electrophysiological properties through these mechanisms, thereby adjusting the pattern and type of neurotransmitters (such as norepinephrine, neuropeptide Y) released to their pulmonary innervation zones. This, in turn, could disrupt the pre-existing "pro-inflammatory" neural signals and establish a new "anti-inflammatory" neuro-immune microenvironment.

4.2. Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Global Remodeling of the Lung Tissue Gene Expression Profile by SG-IPL

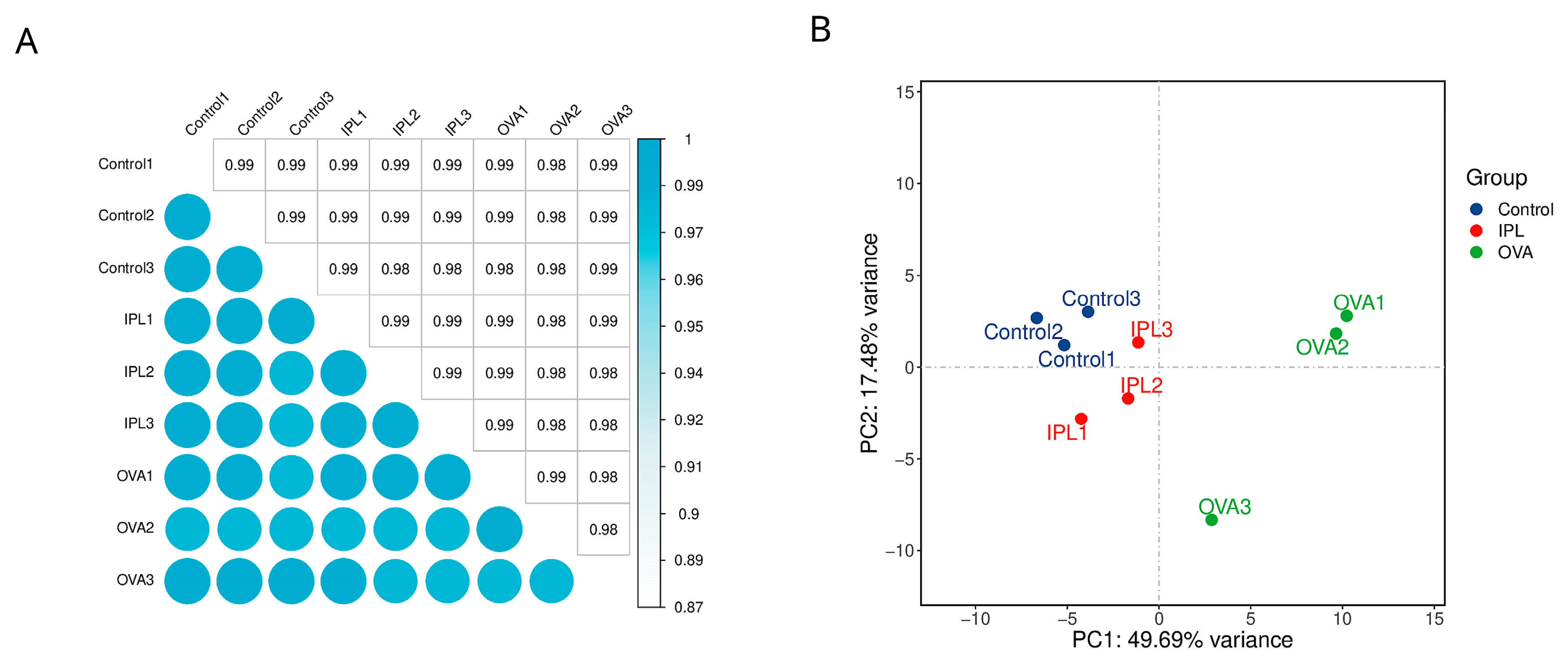

To move beyond observations of a few candidate molecules and to understand the molecular basis of SG-IPL intervention from an unbiased, systemic perspective, we employed high-throughput RNA sequencing. The results from data quality control and global analysis provided a macroscopic and highly persuasive view of the therapeutic effect of SG-IPL. Both inter-sample correlation analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) demonstrated excellent intra-group reproducibility and clear inter-group separation (

Figure 3A, 3B). In the PCA plot, the three experimental groups formed three distinct and well-defined clusters in the transcriptomic space defined by PC1 (explaining 49.69% of the variance) and PC2 (explaining 17.48% of the variance). Critically, the sample points representing the treated SG-IPL group (red) were precisely positioned on the primary component PC1 axis between the healthy control group (blue) and the disease model group (green). This pattern strongly implies that the SG-IPL intervention induced a significant, global "reversion" or "normalization" of the overall gene expression profile from a disease state back towards a healthy state.

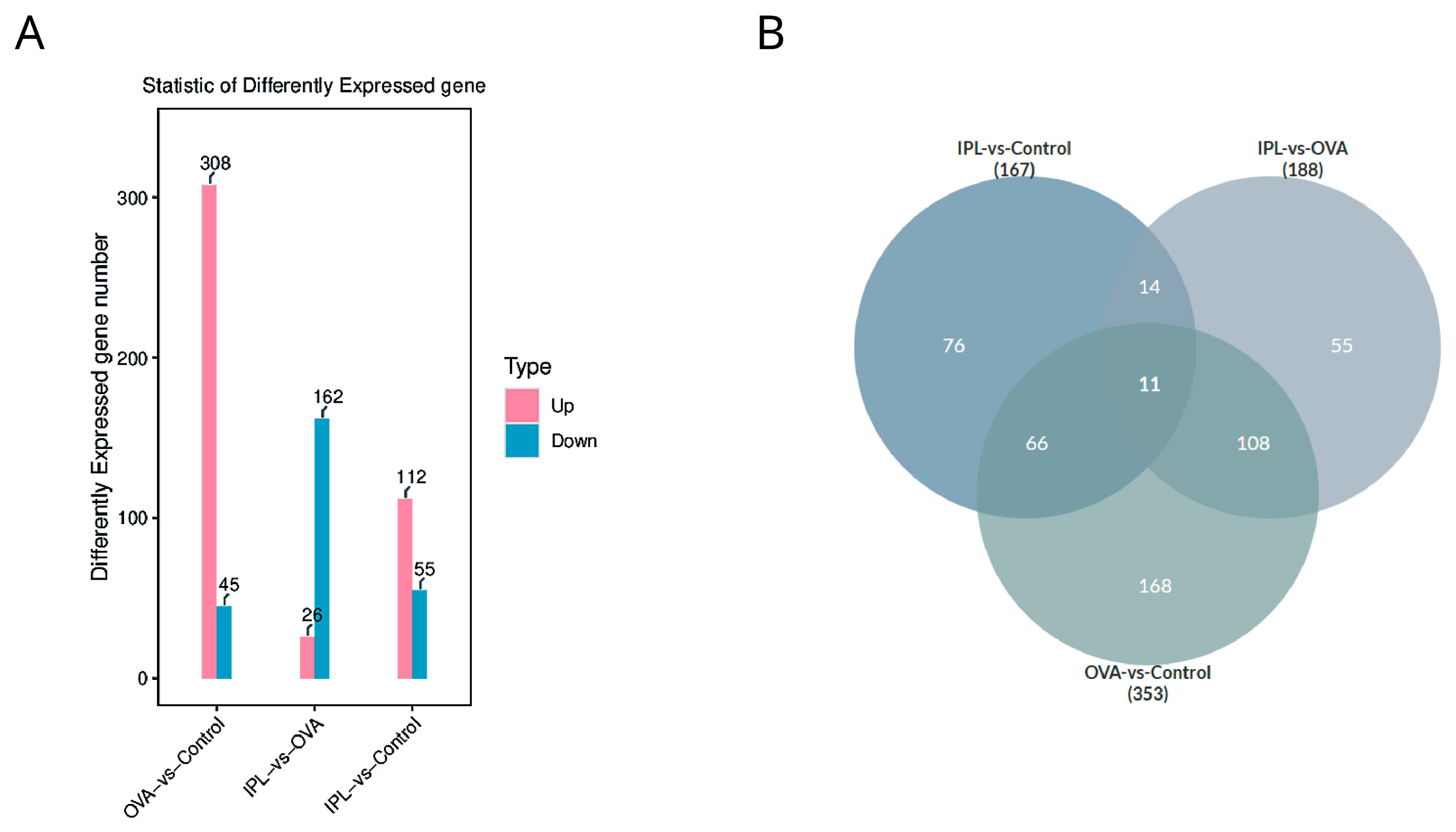

Statistics of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) further quantified the intrinsic pattern of this "reversion." Compared to the Control group, the OVA model induced the significant differential expression of 353 genes, with 308 genes upregulated and only 45 downregulated (

Figure 4A), clearly depicting a strong, "pro-inflammatory" transcriptional pattern dominated by gene activation. However, after SG-IPL treatment (in the IPL-vs-OVA comparison), we identified 188 DEGs, with a fundamental reversal in the expression pattern: the number of significantly downregulated genes (162) overwhelmingly outnumbered the upregulated genes (26). The intersection analysis from the Venn diagram (

Figure 4B) reveals the core of this reversal: the gene programs activated in the OVA model are the primary targets of suppression by the SG-IPL intervention. For example, a substantial portion (11+108=119) of the genes significantly upregulated in the "OVA-vs-Control" comparison were significantly downregulated in the "IPL-vs-OVA" comparison. This indicates that the therapeutic strategy of SG-IPL is not primarily to activate new "protective" pathways but rather to more efficiently and systemically "switch off" and "inhibit" the pathological gene programs that are aberrantly activated in the disease state. This global transcriptional reprogramming provides a solid molecular foundation for the multi-dimensional improvements we observed at the phenotypic level.

4.3. Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Precisely Locating the Inflammatory Network Systemically Suppressed by SG-IPL

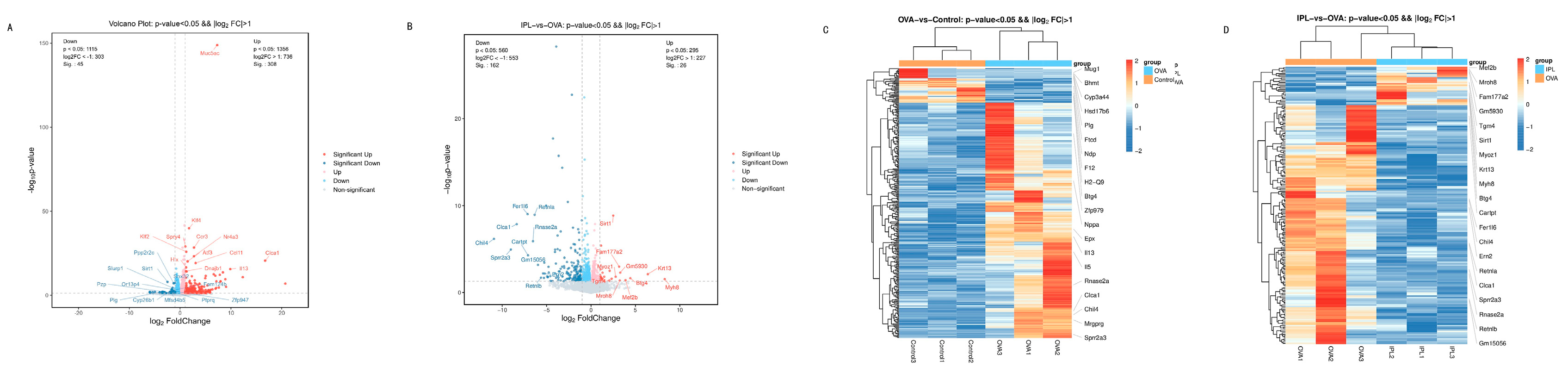

To further investigate the specific functional roles of the gene programs broadly regulated by SG-IPL, we performed KEGG pathway and GO functional enrichment analyses on the sets of differentially expressed genes. The volcano plot (

Figure 5A) visually demonstrated the dramatic upregulation of inflammatory genes in the OVA model, such as Th2 cytokines (Il5, Il13), eosinophil chemokines (Ccl11, Ccl24), and genes related to airway remodeling and mucus secretion (Chil4, Clca1). The activation of these genes is highly consistent with the classic pathological mechanisms of asthma [

6,

18,

25].

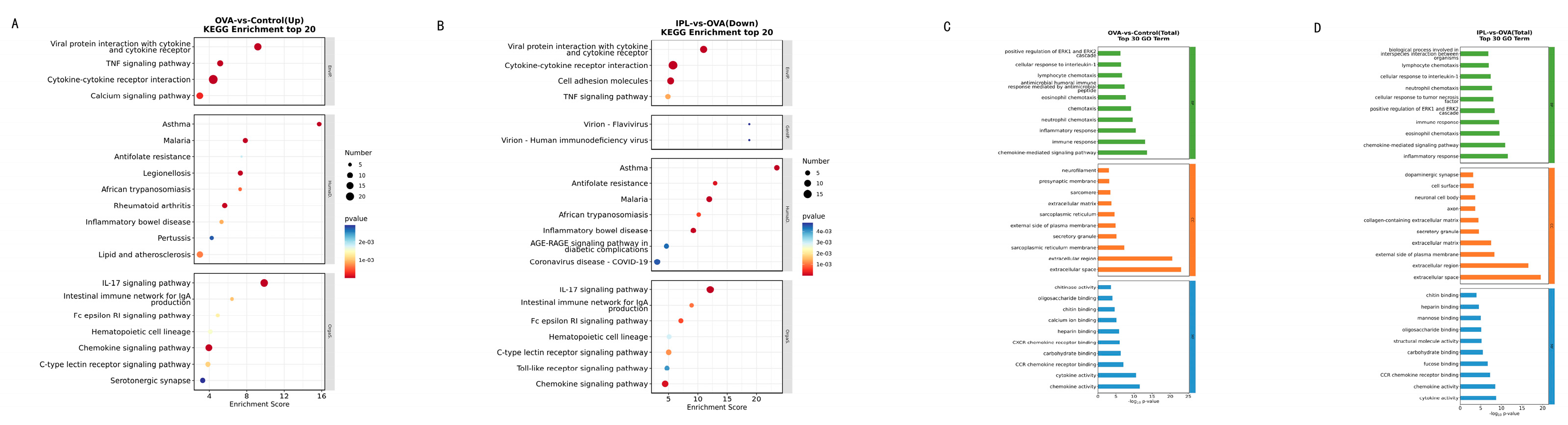

The results of the KEGG pathway enrichment analysis provided a blueprint for precisely identifying the biological pathway networks "extinguished" by SG-IPL. In the OVA model, the upregulated genes were highly enriched in a series of textbook inflammatory and immune-related pathways, including "Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction," "TNF signaling pathway," "IL-17 signaling pathway," and the directly related "Asthma" pathway (

Figure 6A). This confirms the validity of our model and outlines the core molecular network of the disease state. Subsequently, conducting the same analysis on the 162 genes significantly downregulated after SG-IPL treatment, we obtained a near-perfect mirror image (

Figure 6B). The pathways suppressed by SG-IPL treatment were precisely the core inflammatory pathways activated in the OVA model, such as "Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction," "TNF signaling pathway," "Toll-like receptor signaling pathway," and "Chemokine signaling pathway." The clustering heatmaps (

Figure 5C, 5D) visually confirmed this pattern: the gene clusters highly expressed in the OVA group were systemically restored to low expression levels approaching those of the Control group in the IPL group. GO enrichment analysis yielded highly consistent conclusions (

Figure 6C, 6D), showing that biological processes related to "immune response," "inflammatory response," and "chemotaxis" were significantly suppressed after SG-IPL intervention. These analytical results collectively reveal that SG-IPL effectively alleviates airway inflammation because it performs a systemic, synergistic "functional dismantlement" of the entire inflammatory network at the transcriptional level. This network-level regulation may explain why a single physical intervention can simultaneously improve multiple cytokine levels and complex histopathological features, an advantage that may be difficult to achieve with traditional single-target drugs.

4.4. Exploration of Upstream Regulatory Mechanisms: The SIRT1/NF-κB Axis as a Potential Core Hub

The most critical mechanistic finding of this study, derived from unbiased transcriptomic analysis and subsequent network biology mining, links the anti-inflammatory effects of SG-IPL to a key upstream regulatory molecule: Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1). In our volcano plot analysis (

Figure 5B), Sirt1 was one of the few genes whose expression was significantly upregulated after IPL treatment. Although its fold-change was not extreme, its "maverick" upregulation against a background of general gene suppression made it a highly promising candidate regulator. SIRT1 is an NAD+-dependent class III histone/non-histone deacetylase, widely recognized as a core sensor of cellular energy metabolism and stress responses [

16]. In the context of inflammation regulation, SIRT1 is known as a "master brake on inflammation," with its most classic anti-inflammatory mechanism being the inhibition of Nuclear Factor-κB (NF-κB) transcriptional activity by directly interacting with the p65 subunit and catalyzing the deacetylation of its key lysine residue (Lys310), thereby shutting down its vast downstream network of pro-inflammatory genes [

10,

17,

24]. Critically, previous studies have reported that both the expression and enzymatic activity of SIRT1 are significantly decreased in the lung tissues of asthma patients and animal models [

11,

20], suggesting that impaired SIRT1 function is an important intrinsic factor for the persistence of asthma inflammation.

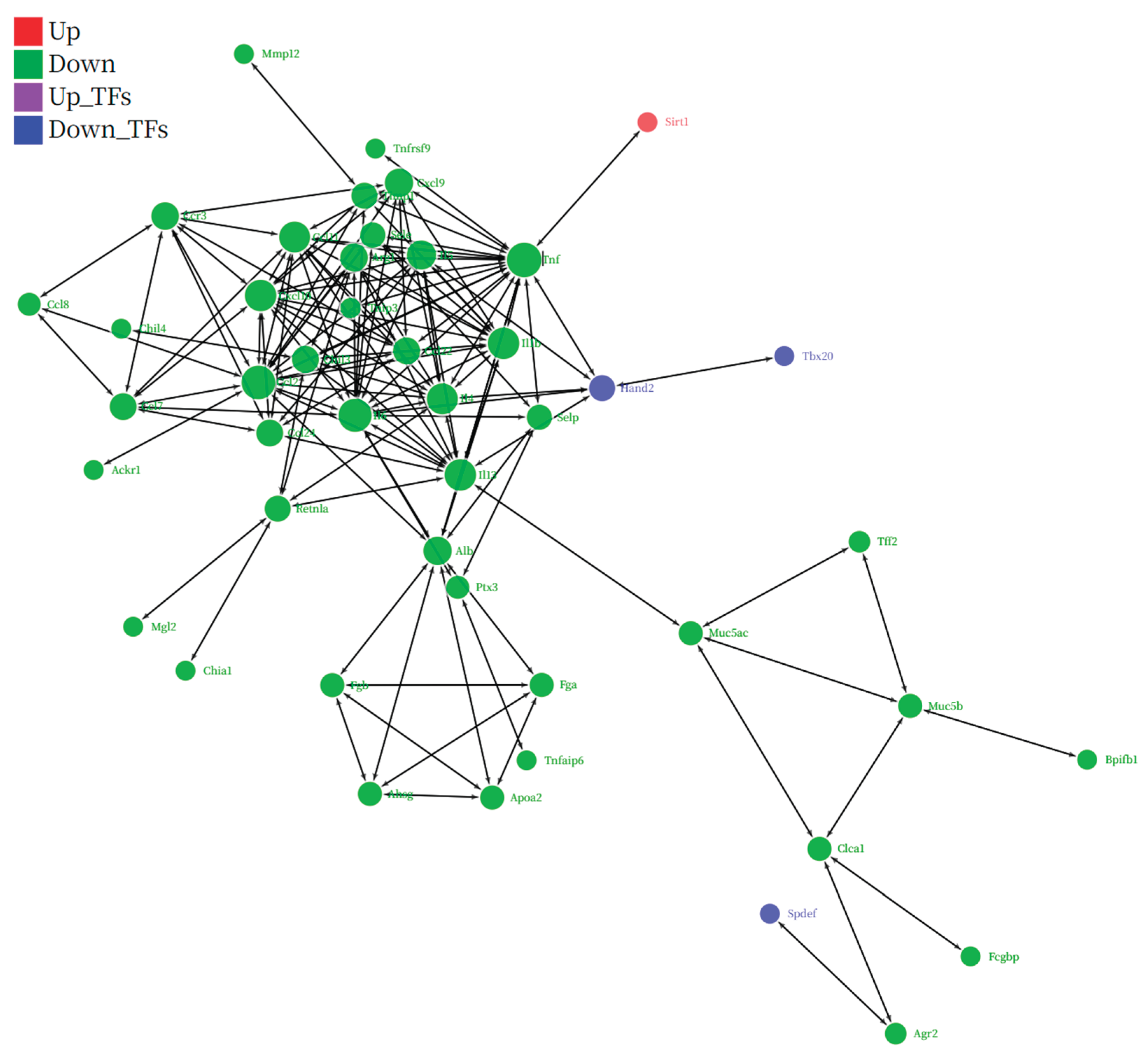

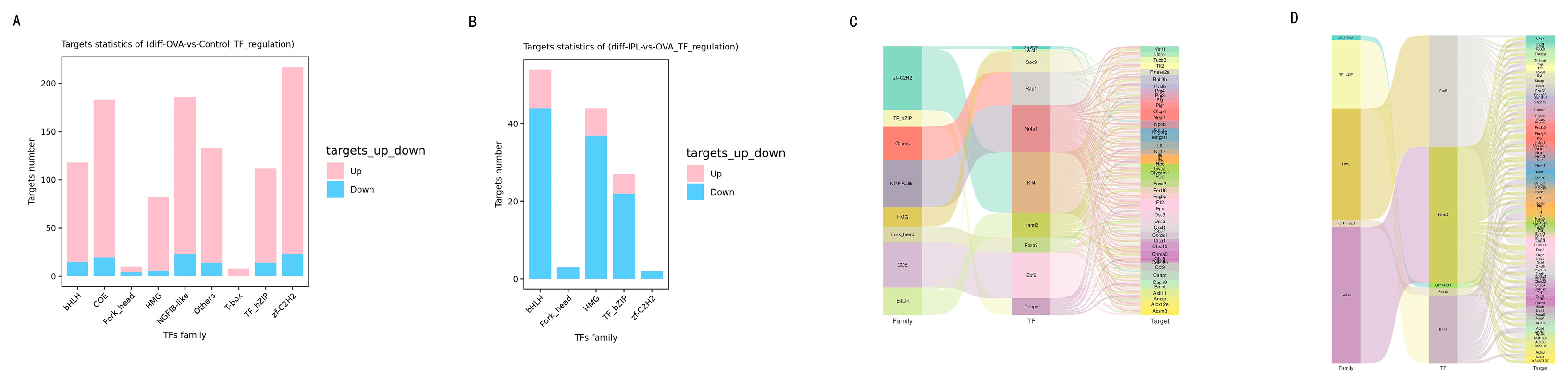

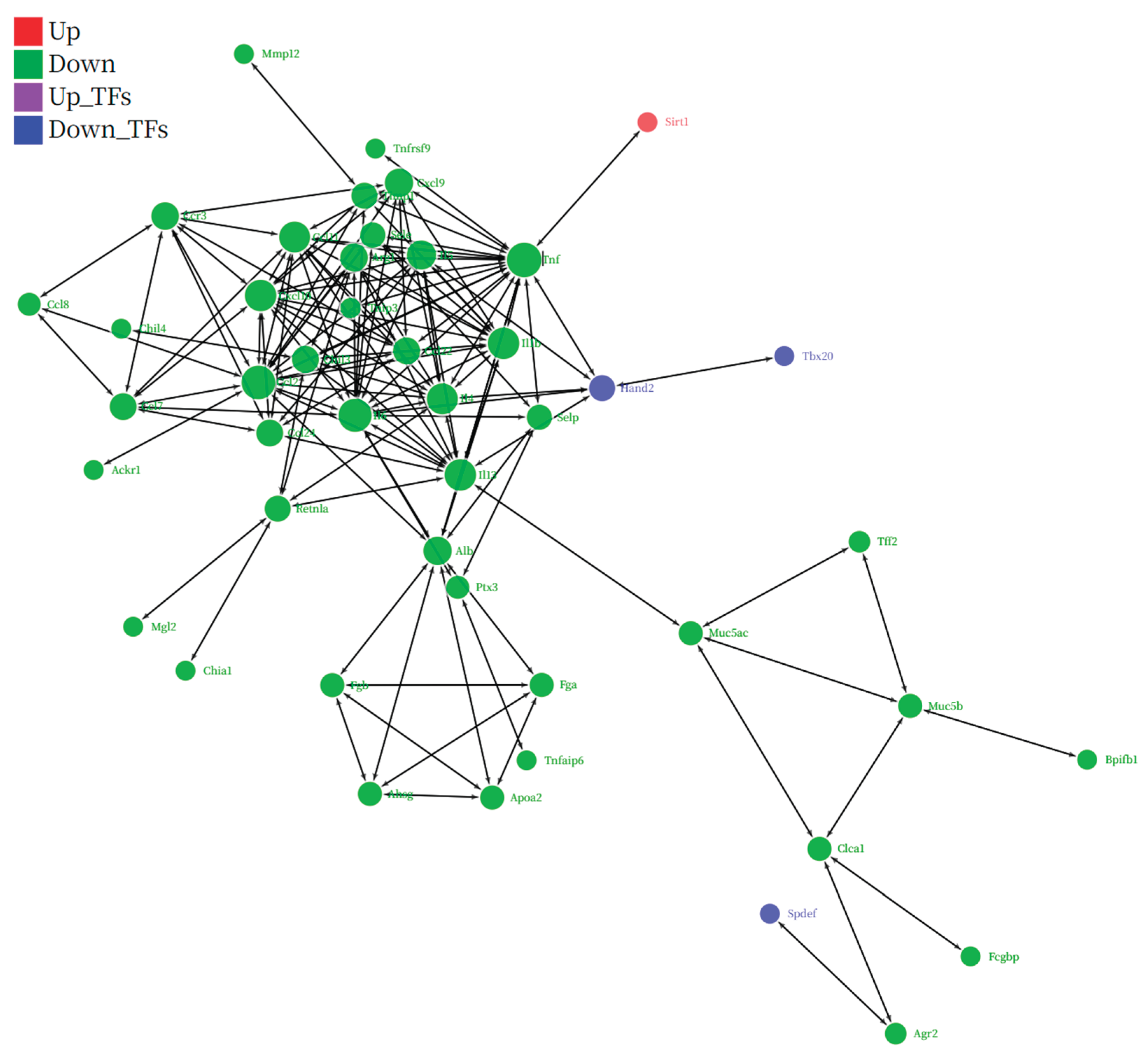

Our transcriptomic data perfectly align with this theory and allow us to construct a logically rigorous hypothetical model. First, transcription factor (TF) regulatory network analysis (

Figure 7) showed that in the OVA model, the target genes of several pro-inflammatory TF families (such as bHLH, HMG) exhibited a predominantly upregulated activation pattern (

Figure 7A, 7C), whereas after SG-IPL treatment, the target genes of these TF families shifted to an overwhelmingly downregulated state (

Figure 7B, 7D). This indicates that the SG-IPL intervention profoundly affects the upstream "transcriptional command system." Second, and most critically, our integrated network of protein-protein interactions (PPI) and TF-target gene regulation (

Figure 8) visually illustrates this regulatory hierarchy. In this network, we observed a clear negative regulatory relationship between the upregulated SIRT1 (red node) and the systemically downregulated, highly interconnected "inflammatory storm module" (green nodes), which is composed of TNF, IL-1β, IL-4/5/13, and various chemokines. In particular, the direct interaction between SIRT1 and the master inflammatory mediator TNF provides a key link for this hypothesis. Therefore, a self-consistent cascade of events, from "SG-IPL → unknown neuro-humoral signal → upregulation of SIRT1 expression in lung tissue → inhibition of key TFs like NF-κB → systemic shutdown of the downstream inflammatory gene network → amelioration of the airway inflammation phenotype," can be constructed. This hypothetical model not only perfectly explains all our observed data but also provides a clear, profound, and internally consistent framework for understanding the deep anti-inflammatory mechanism of SG-IPL.

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Perspectives

As a pioneering exploratory study, this work opens new directions for the field but also has certain limitations, which in turn point the way for future research. First, our inference of the SIRT1/NF-κB axis as a core mechanism is currently based mainly on transcriptomic and bioinformatic analyses. Although the logical chain is complete and strongly supported by the data, it still lacks direct validation at the protein and functional levels. Future work should include Western Blot analysis of SIRT1 protein expression and the phosphorylation and acetylation levels of NF-κB p65, as well as direct validation of SIRT1's causal role in mediating the efficacy of SG-IPL using pharmacological activators (e.g., resveratrol) or inhibitors, or even conditional SIRT1 knockout mouse models. Second, the observation period of this study was 7 days, primarily assessing the interventional effect of SG-IPL on the acute inflammatory phase. Its long-term effects on chronic pathological changes such as airway remodeling (e.g., smooth muscle hyperplasia, basement membrane thickening) and the durability of its effects remain unknown and require longer-term animal experiments to address. Third, the details of the signal transmission pathway from the cervical stellate ganglion to the intrathoracic lung tissue remain a "black box." Whether this signal is transmitted via direct nerve projections or mediated by circulating neurotransmitters/hormones (such as catecholamines or neuropeptide Y) is a highly attractive topic for further investigation using neurotracing techniques, pharmacological blockers, or selective denervation models.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study have significant theoretical importance and potential clinical value. It provides solid experimental data for neuro-immune regulation-based asthma treatment strategies and suggests the enormous potential of non-invasive physical therapies in regulating complex chronic inflammatory diseases. Future research can proceed along the lines of the hypothesis we have proposed: first, by deeply validating and expanding the mechanism, clarifying the more detailed molecular events upstream and downstream of SIRT1. Second, by finely mapping the immunological landscape, using techniques like single-cell sequencing to explore the differential regulatory effects of SG-IPL on various immune cell subpopulations (such as Th1/Th2/Th17 cells, regulatory T cells, alveolar macrophages, etc.). Finally, and most importantly, is to actively promote the clinical translation of this non-invasive, high-safety physical therapy by designing rigorous preclinical studies and ultimately human clinical trials to evaluate its efficacy, safety, and optimal treatment parameters in asthma patients with different phenotypes and severity levels.

Figure 1.

SG-IPL intervention ameliorates Th2-type inflammation in OVA-induced asthmatic mice. (A) Schematic diagram of the experimental protocol. BALB/c mice were sensitized with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of ovalbumin (OVA) and alum on days 1 and 7. Mice were subsequently challenged with intranasal (i.n.) OVA from day 14 to day 21. Infrared polarized light (IPL) intervention was administered daily from day 21 to day 28. All mice were sacrificed on day 28 for sample collection. (B) Anatomical illustration of the SG-IPL intervention. The probe delivered infrared polarized light to the surface projection area of the stellate ganglion, located near the 7th cervical vertebrae and superior to the collarbone. (C) Protein levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from Control, OVA, and OVA+SG-IPL groups, quantified by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=5 per group). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 1.

SG-IPL intervention ameliorates Th2-type inflammation in OVA-induced asthmatic mice. (A) Schematic diagram of the experimental protocol. BALB/c mice were sensitized with intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of ovalbumin (OVA) and alum on days 1 and 7. Mice were subsequently challenged with intranasal (i.n.) OVA from day 14 to day 21. Infrared polarized light (IPL) intervention was administered daily from day 21 to day 28. All mice were sacrificed on day 28 for sample collection. (B) Anatomical illustration of the SG-IPL intervention. The probe delivered infrared polarized light to the surface projection area of the stellate ganglion, located near the 7th cervical vertebrae and superior to the collarbone. (C) Protein levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) from Control, OVA, and OVA+SG-IPL groups, quantified by ELISA. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n=5 per group). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test. ****P < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Global transcriptomic profiling reveals distinct clustering and a therapeutic shift induced by SG-IPL. (A) Heatmap of the Pearson correlation matrix for all RNA-sequencing samples (n=3 per group). The color scale indicates the correlation coefficient, with darker shades of cyan representing higher correlation. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) plot of the RNA-seq data. Samples from the Control (blue), OVA (green), and IPL (red) groups are projected onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). The percentage of variance explained by each principal component is indicated on the axes.

Figure 3.

Global transcriptomic profiling reveals distinct clustering and a therapeutic shift induced by SG-IPL. (A) Heatmap of the Pearson correlation matrix for all RNA-sequencing samples (n=3 per group). The color scale indicates the correlation coefficient, with darker shades of cyan representing higher correlation. (B) Principal component analysis (PCA) plot of the RNA-seq data. Samples from the Control (blue), OVA (green), and IPL (red) groups are projected onto the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2). The percentage of variance explained by each principal component is indicated on the axes.

Figure 4.

Differential gene expression analysis highlights a systemic suppressive pattern following SG-IPL treatment. (A) Bar chart showing the number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for the comparisons of OVA-vs-Control and IPL-vs-OVA. Pink bars represent upregulated genes, and blue bars represent downregulated genes. The exact number of genes is indicated above each bar. DEG criteria: |log2(FoldChange)| > 1 and p-value < 0.05. (B) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of DEG sets among the three comparisons: IPL-vs-Control, IPL-vs-OVA, and OVA-vs-Control. The number in each section represents the count of genes unique to that section or intersection.

Figure 4.

Differential gene expression analysis highlights a systemic suppressive pattern following SG-IPL treatment. (A) Bar chart showing the number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for the comparisons of OVA-vs-Control and IPL-vs-OVA. Pink bars represent upregulated genes, and blue bars represent downregulated genes. The exact number of genes is indicated above each bar. DEG criteria: |log2(FoldChange)| > 1 and p-value < 0.05. (B) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap of DEG sets among the three comparisons: IPL-vs-Control, IPL-vs-OVA, and OVA-vs-Control. The number in each section represents the count of genes unique to that section or intersection.

Figure 5.

Volcano plots and clustering heatmaps visualize the transcriptional landscape of asthma and SG-IPL intervention. (A, B) Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for the OVA-vs-Control comparison (A) and the IPL-vs-OVA comparison (B). The x-axis represents the log2(Fold Change), and the y-axis represents the -log10(p-value). Red dots indicate significantly upregulated genes, blue dots indicate significantly downregulated genes, and grey dots indicate non-significant genes. Dashed lines indicate the thresholds for statistical significance. Key genes are labeled. (C, D) Hierarchical clustering heatmaps of DEGs for OVA-vs-Control (C) and IPL-vs-OVA (D). Each row represents a gene, and each column represents a sample. The color scale represents the z-score normalized expression values, with red indicating high expression and blue indicating low expression.

Figure 5.

Volcano plots and clustering heatmaps visualize the transcriptional landscape of asthma and SG-IPL intervention. (A, B) Volcano plots of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for the OVA-vs-Control comparison (A) and the IPL-vs-OVA comparison (B). The x-axis represents the log2(Fold Change), and the y-axis represents the -log10(p-value). Red dots indicate significantly upregulated genes, blue dots indicate significantly downregulated genes, and grey dots indicate non-significant genes. Dashed lines indicate the thresholds for statistical significance. Key genes are labeled. (C, D) Hierarchical clustering heatmaps of DEGs for OVA-vs-Control (C) and IPL-vs-OVA (D). Each row represents a gene, and each column represents a sample. The color scale represents the z-score normalized expression values, with red indicating high expression and blue indicating low expression.

Figure 6.

Functional enrichment analysis identifies suppression of core inflammatory pathways by SG-IPL. (A, B) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis shown as bubble plots for upregulated genes in the OVA-vs-Control comparison (A) and downregulated genes in the IPL-vs-OVA comparison (B). The x-axis represents the enrichment score. The size of the bubble corresponds to the number of genes enriched in the pathway, and the color corresponds to the p-value. (C, D) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis for DEGs in the OVA-vs-Control (C) and IPL-vs-OVA (D) comparisons. Bar charts show the top enriched terms in the categories of Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF). The x-axis indicates the number of enriched genes.

Figure 6.

Functional enrichment analysis identifies suppression of core inflammatory pathways by SG-IPL. (A, B) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis shown as bubble plots for upregulated genes in the OVA-vs-Control comparison (A) and downregulated genes in the IPL-vs-OVA comparison (B). The x-axis represents the enrichment score. The size of the bubble corresponds to the number of genes enriched in the pathway, and the color corresponds to the p-value. (C, D) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis for DEGs in the OVA-vs-Control (C) and IPL-vs-OVA (D) comparisons. Bar charts show the top enriched terms in the categories of Biological Process (BP), Cellular Component (CC), and Molecular Function (MF). The x-axis indicates the number of enriched genes.

Figure 7.

Transcription factor analysis reveals reprogramming of regulatory networks by SG-IPL. (A, B) Bar charts showing the number of up- (pink) and downregulated (blue) target genes for differentially regulated transcription factor (TF) families in the OVA-vs-Control (A) and IPL-vs-OVA (B) comparisons. (C, D) Sankey diagrams illustrating the regulatory relationships between differentially expressed TFs (left nodes) and their target DEGs (right nodes) for the OVA-vs-Control (C) and IPL-vs-OVA (D) comparisons. The width of the flow is proportional to the strength of the regulatory evidence.

Figure 7.

Transcription factor analysis reveals reprogramming of regulatory networks by SG-IPL. (A, B) Bar charts showing the number of up- (pink) and downregulated (blue) target genes for differentially regulated transcription factor (TF) families in the OVA-vs-Control (A) and IPL-vs-OVA (B) comparisons. (C, D) Sankey diagrams illustrating the regulatory relationships between differentially expressed TFs (left nodes) and their target DEGs (right nodes) for the OVA-vs-Control (C) and IPL-vs-OVA (D) comparisons. The width of the flow is proportional to the strength of the regulatory evidence.

Figure 8.

Integrated regulatory network analysis pinpoints SIRT1 as a key upstream regulator of the suppressed inflammatory module. A comprehensive regulatory network constructed from differentially expressed genes in the IPL-vs-OVA comparison, integrating protein-protein interactions (PPI) and transcription factor (TF)-target gene relationships. Nodes represent genes/proteins, and edges represent interactions or regulatory links. Node colors indicate regulatory status: red for upregulated genes (e.g., Sirt1), green for downregulated genes forming the core inflammatory module (e.g., Tnf, Il1b, Il4, Il5, Il13), and blue for downregulated TFs (e.g., Spdef, Tbx20). The network highlights the potential upstream regulatory role of the upregulated SIRT1 on the systemically downregulated inflammatory gene network.Topological analysis of the network revealed that genes significantly downregulated after SG-IPL intervention (green nodes) formed a highly interconnected functional module. Functional annotation of the nodes within this module showed that its members were highly enriched in pro-inflammatory molecules closely related to asthma pathology. Specifically, this module included core pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (Tnf) and interleukin-1β (Il1b); key effector molecules of the type II immune response, such as interleukin-4 (Il4), interleukin-5 (Il5), and interleukin-13 (Il13); and the chemokine and receptor axis that dominates eosinophil recruitment, such as Ccl24 and Ccr3. The systemic downregulation of this "inflammatory module" provides network-level evidence for the broad suppression of airway inflammation by SG-IPL at the molecular level.

Figure 8.

Integrated regulatory network analysis pinpoints SIRT1 as a key upstream regulator of the suppressed inflammatory module. A comprehensive regulatory network constructed from differentially expressed genes in the IPL-vs-OVA comparison, integrating protein-protein interactions (PPI) and transcription factor (TF)-target gene relationships. Nodes represent genes/proteins, and edges represent interactions or regulatory links. Node colors indicate regulatory status: red for upregulated genes (e.g., Sirt1), green for downregulated genes forming the core inflammatory module (e.g., Tnf, Il1b, Il4, Il5, Il13), and blue for downregulated TFs (e.g., Spdef, Tbx20). The network highlights the potential upstream regulatory role of the upregulated SIRT1 on the systemically downregulated inflammatory gene network.Topological analysis of the network revealed that genes significantly downregulated after SG-IPL intervention (green nodes) formed a highly interconnected functional module. Functional annotation of the nodes within this module showed that its members were highly enriched in pro-inflammatory molecules closely related to asthma pathology. Specifically, this module included core pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (Tnf) and interleukin-1β (Il1b); key effector molecules of the type II immune response, such as interleukin-4 (Il4), interleukin-5 (Il5), and interleukin-13 (Il13); and the chemokine and receptor axis that dominates eosinophil recruitment, such as Ccl24 and Ccr3. The systemic downregulation of this "inflammatory module" provides network-level evidence for the broad suppression of airway inflammation by SG-IPL at the molecular level.