Submitted:

28 June 2025

Posted:

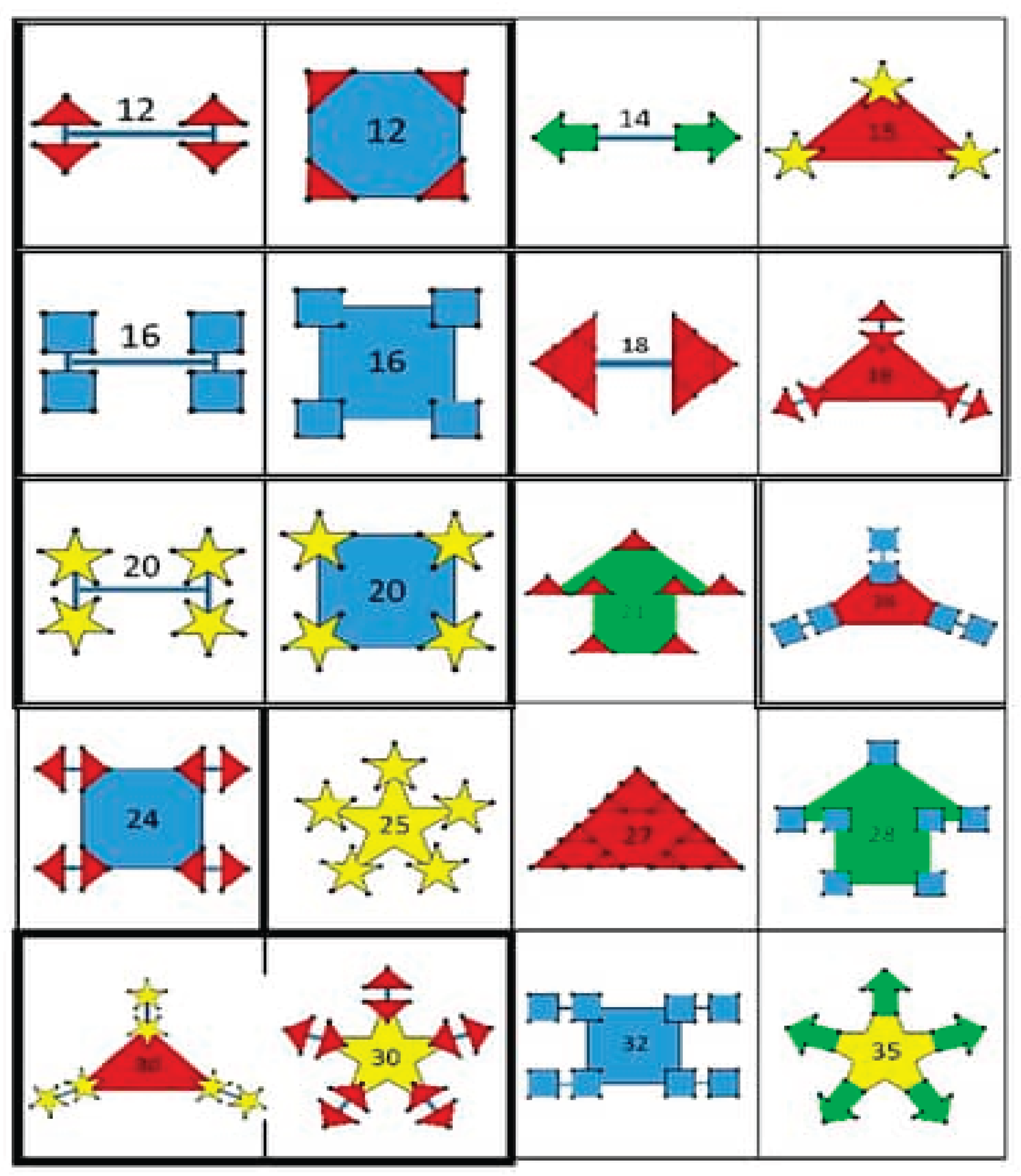

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Enduring Challenge of the Multiplication Table

2. Theoretical Framework: Constructivism, Embodied Cognition, and the Beauty of Fractals

3. The Fractal Geometric Technique Explained

4. Pedagogical Implications for Next-Generation Teaching

- From Memorization to Conceptualization: The major advantage is the change from rote remembering to a profound, visual comprehension of the mechanics of multiplication. Students grasp the patterns' recurrence, so developing number sense rather than only fact retrieval (Gray and Tall, 1994). By turning a high-stakes memory exercise into a low-stakes creative one, the approach can greatly alleviate anxiety (Boaler, 2019). Rather than on speed and accuracy, the focus is on exploration and beauty, hence creating a more welcoming and inclusive learning environment (Dweck, 2006).

- Encouragement of Creativity and Curiosity: Connecting mathematics organically with art encourages students to question what if? queries. Using a 12-point circle (base12), the 13s table yields what pattern? This encourages questioning and positions mathematics as a creative rather than simply a procedural discipline (Sawyer and Henriksen, 2024).

- More sophisticated students can be tasked to predict patterns, describe the symmetries, or even utilize simple coding tools (e.g. Scratch) to generate the shapes digitally, therefore integrating computational thinking (Papert, 2020; Wing, 2006); younger children can concentrate on building the forms for easier tables. Mirroring the multidisciplinary nature of modern problem solving (Rogers et al., 2007), this method flawlessly integrates arithmetic, visual arts, and technology.

5. Conclusion: Towards a New Mathematical Pedagogy

References

- Boaler, J. (2019). Limitless mind: Learn, lead, and live without barriers. San Francisco.

- Bruner, J. S. (1961). The act of discovery. Harvard Educational Review, 31(1), 21–32.

- Clements, M. A. Kaur, B., Lowrie, T., Mesa, V., & Prytz, J. (Eds.). (2024). Fourth international handbook of mathematics education. Springer.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. Csikzentmihaly, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience (Vol. 1990, p. 1). New York: Harper & Row.

- Dehaene, S. (2011). The number sense: How the mind creates mathematics (Rev. ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Devlin, K. j. (2000). The math gene: How mathematical thinking evolved and why numbers are like gossip. New York: Basic Books.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Gray, E. M. Tall, D. O. (1994). Duality, ambiguity, and flexibility: A "proceptual" view of simple arithmetic. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 25(2), 116–140.

- Lau, N. T. , Ansari, D., & Sokolowski, H. M. (2024). Unraveling the interplay between math anxiety and math achievement. Trends in Cognitive Sciences.

- Lockhart, P. (2009). A mathematician's lament: How school cheats us out of our most fascinating and imaginative art form. Bellevue Literary Press.

- Mageed, I. A. (2023a, November). Fractal Dimension (Df) of Ismail’s Fourth Entropy (with Fractal Applications to Algorithms, Haptics, and Transportation. In 2023 international conference on computer and applications (ICCA) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024a). The Fractal Dimension Theory of Ismail's Third Entropy with Fractal Applications to CubeSat Technologies and Education. Complexity Analysis and Applications, 1(1), 66-78.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024b). Fractal Dimension of the Generalized Z-Entropy of The Rényian Formalism of Stable Queue with Some Potential Applications of Fractal Dimension to Big Data Analytics.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024c). Fractal Dimension (Df) Theory of Ismail’s Entropy (IE) with Potential Df Applications to Structural Engineering. Journal of Intelligent Communication, 3(2), 111-123.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024d). A Theory of Everything: When Information Geometry Meets the Generalized Brownian Motion and the Einsteinian Relativity. J Sen Net Data Comm, 4(2), 01-22.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024e). The Generalized Z-Entropy’s Fractal Dimension within the Context of the Rényian Formalism Applied to a Stable M/G/1 Queue and the Fractal Dimension’s Significance to Revolutionize Big Data Analytics. J Sen Net Data Comm, 4(2), 01-11.

- Mageed, I. A. (2024j). Do You Speak The Mighty Triad?(Poetry, Mathematics and Music) Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. MDPI preprints.

- Mageed, I. A. (2025c). Fractals Across the Cosmos: From Microscopic Life to Galactic Structures.

- Mageed, I. A. (2025a). The Hidden Poetry & Music of Mathematics for Teaching Professionals: Inspiring Students through the Art of Mathematics: A Guide for Educators. Eliva Press. Available online: https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-1450104825.

- Mageed, I. A. Bhat, A. H. (2022). Generalized Z-Entropy (Gze) and fractal dimensions. Appl. math, 16(5), 829-834.

- Mageed, I. A. , & Mohamed, M.(2023). Chromatin can speak Fractals: A review.

- Mageed, I.A. (2024f). Do You Speak The Mighty Triad?(Poetry, Mathematics and Music) Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. MDPI Preprints.

- Mageed, I.A. (2024g). The Mathematization of Puzzles or Puzzling Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024h). Let’s All Dance and Play Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024i). AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity Through Ismail A Mageed's Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024k). The Mathematization of Puzzles or Puzzling Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024l). Let’s All Dance and Play Mathematics Innovative Teaching of Mathematics. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2024m). AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity Through Ismail A Mageed's Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Mageed, I.A. (2025b). The Hidden Dancing & Physical Education of Mathematics for Teaching Professionals. Eliva Press. Available online: https://www.elivabooks.com/en/book/book-7724827898.

- Mageed, I.A. and Nazir, A.R. (2024). AI-Generated Abstract Expressionism Inspiring Creativity through Ismail A Mageed's Internal Monologues in Poetic Form. Annals of Process Engineering and Management, 1(1), pp.33-85.

- Matthews, C. D. M. (2025). Middle School Mathematics Teachers’ Use of Diverse Mathematics Educational Technology Tools: IXL, i-Ready, and/or MATHia (Doctoral dissertation, Walden University).

- Medina, J. (2011). Brain rules: 12 principles for surviving and thriving at work, home, and school. ReadHowYouWant. com.

- Papert, S. A. (2020). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. Basic books.

- Pellizzoni, S. Cargnelutti, E., Cuder, A., & Passolunghi, M. C. (2022). The interplay between math anxiety and working memory on math performance: A longitudinal study. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1510(1), 132-144.

- Piaget, J. (1970). Science of education and the psychology of the child. Trans. D. Coltman.

- Rittle-Johnson, B. Siegler, R. S. (2022). The relation between conceptual and procedural knowledge in learning mathematics: A review. The development of mathematical skills, 75-110.

- Rogers, M. Volkmann, M. J., & Abell, S. K. (2007). Science and mathematics: A natural connection. Science and Children, 45(2), 60-61.

- Sawyer, R. K. Henriksen, D. (2024). Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation. Oxford university press.

- TPT. (2025). IXL LEARNING. Fractal Multiplication table. Online available at. Available online: https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Fractal-Multiplication-table-2397128.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (Vol. 86). Harvard university press.

- Wilson, M. (2002). Six views of embodied cognition. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 9(4), 625–636.

- Wing, J. M. (2006). Computational thinking. Communications of the ACM, 49(3), 33–35.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).