1. Introduction

Since the concept of unethical pro-organizational behavior (UPB) was introduced by Umphress et al. (2010), scholars have extensively explored this phenomenon from diverse theoretical perspectives over the past decade (Mishra et al., 2022; Mo et al., 2022; Steele et al., 2023). As defined by Umphress et al. (2010), UPB refers to employees’ actions that violate core societal values, ethical norms, laws, or legitimate behavioral standards, intended to benefit their organization or its members (Umphress et al., 2010; Umphress & Bingham, 2011). While UPB may appear advantageous to organizations in the short term, empirical evidence demonstrates that its long-term practice not only jeopardizes organizational reputation and public trust (Kelebek & Alniacik, 2022; Xu et al., 2024) but also elicits negative emotional and behavioral consequences for the actors (Hu et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2022; Zhang & Du, 2023).

Numerous studies have examined the antecedents of unethical pro-organizational behavior, such as organizational identification and positive social exchange (Chen et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019), yet researches exploring its consequences remains limited (Yang et al., 2022; Zhao & Qu, 2022). Some scholars have investigated employees’ emotional and behavioral responses following UPB engagement. Empirical evidence indicates that UPB performers may experience complex emotional reactions, including pride, shame, and guilt (Tang et al., 2020; Xu et al., 2024), where pride stems from benefitting organizations while shame and guilt arises from deceiving customers or stakeholders. Liu et al. (2021) further demonstrated that these conflicting emotional states (guilt & pride) would induce state anxiety and intensify employees’ work-to-life conflict.

Additionally, researches have investigated UPB’s linkages with emotional exhaustion (EE) and psychological entitlement (PE) (Jiang et al., 2023; Liao et al., 2023; Yao et al., 2022). Although EE and PE more often appear as antecedents of UPB in research, these complex affective states not only affect the occurrence of UPB but also influence the subsequent behaviors of UPB. For instance, employees with heightened PE not only tend to engage in UPB but may also exhibit increased counterproductive behaviors (Naseer et al., 2020), suggesting that such psychological states persist throughout the UPB process—both preceding and following the act.

Although existing researches have established linkages between UPB and emotional responses, several critical gaps remain in the current literature. First, empirical findings exhibit inconsistencies across studies. For instance, Chen et al. (2023) reported significant positive correlations between UPB and guilt, whereas Wang et al. (2018) found a negative association between employees’ UPB and anticipated guilt. Second, most studies rely on cross-sectional surveys or short-term retrospective designs, employing different measurement tools without rigorous or consistent control conditions (Chen et al., 2023; Liao et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2020). This has resulted in divergent estimates of the effect sizes linking UPB to emotional outcomes. Finally, a significant disconnect persists in the literature between studies examining the emotional consequences of UPB and those investigating its behavioral outcomes. While emotions like guilt and pride are theorized as key mechanisms driving subsequent behaviors (e.g., moral cleansing vs. moral licensing) (Liao et al., 2023), empirical tests of this integrated emotion-behavior sequence remain scarce and fragmented.

Thus, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of the relationship between UPB and these emotional states. Additionally, the behavioral consequences that may be brought about by the emotions triggered by UPB also need to be explored. To address these issues, we employ meta-analysis to estimate the direction and overall effect magnitude of the relationships between UPB, emotional reactions, and subsequent behaviors, thereby providing theoretical and empirical support for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. UPB and Its Emotional Responses

2.1.1. UPB and the Positive Emotional Responses

Recent scholars have increasingly examined the affective states triggered by UPB. Given UPB’s paradoxical duality—combining benevolent pro-organizational motivation with unethical behavioral attributes, this co-occurring incongruence may elicit complex emotional experiences in actors. Initially, perceiving the pro-organizational nature of UPB could generate positive affective states among employees. As pride constitutes a positive self-conscious emotion, which typically associated with individual achievement and organizational contributions (Tracy & Robins, 2007). Liu et al. (2021) empirically demonstrated that when employees perceived UPB as conducive to organizational interests (e.g., enhancing team performance), they experienced pride because they believed they had “helped the organization”. This finding aligns with Tang et al.’s (2020) observation that employees report pride when UPB facilitates organizational goal attainment, given such behaviors are construed as organizational contributions. Despite these findings, the connection between the two is not always stable, some research results indicate that there is no significant correlation between UPB and pride (Liao et al., 2023).

The reason why employees feel proud of UPB may derive from two mechanisms. Firstly, a high degree of organizational identification can reduce the moral sensitivity of employees and blur their perception of the immorality of UPB (Tang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2018). When employees have a high degree of organizational identification, they may consider their UPB as reflecting organizational loyalty and responsibility, thereby generating a sense of pride such as “I have contributed to the organization” or even “I have sacrificed my personal morality for the organization” (Liao et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2021). Furthermore, the ethical climate within organization can also influences employees’ affective responses to UPB. Affective appraisal theory points out that individual’s cognitive appraisals of events or behaviors can affect their emotional reactions (Lazarus, 1991). While the ethical climate in organization can guide employees’ moral cognitive appraisals of ethical conduct (Mayer et al., 2010; Victor & Cullen, 1988), thereby influencing their emotional responses. Based on this theoretical foundation, Xu and colleagues (2024) found in their research that ethical climate moderates post-UPB affective responses, under low ethical climate conditions, UPB elicits stronger pride; whereas under high ethical climate conditions, UPB evokes heightened shame.

Beyond the singular positive emotion of pride, the pro-organizational attribute of UPB can trigger a particular positive belief, psychological entitlement. Psychological entitlement refers to an individual’s stable and pervasive subjective belief or perception that they deserve preferential treatment and exemption from social responsibilities (Campbell et al., 2004). Shin et al. (2024) found a significant positive correlation between psychological entitlement and unethical pro-organizational behavior, particularly when employees’ personal goals align with organizational objectives, making them more willing to engage in unethical conduct for organizational benefit. This phenomenon occurs because employees with heightened psychological entitlement typically believe they deserve special treatment within the organization. Such beliefs motivate them to achieve organizational goals rapidly through UPB, thereby demonstrating personal worth or gaining personal benefits. For instance, highly entitled employees may consider lying for organizational interests as acceptable, as this contribution would position them as organizational heroes (Lee et al., 2019). Furthermore, employees with high entitlement might even commit UPB to retaliate against aggressive customers (Steele et al., 2023). Collectively, psychological entitlement weakens employees’ internal moral constraints. Those with heightened entitlement tend to rationalize UPB, which alleviates guilt while simultaneously strengthening their willingness to engage in such conduct (Jiang et al., 2023; Zhang & Du, 2022).

2.1.2. UPB and the Negative Emotional Responses

Negative affective responses to UPB are mostly triggered by its unethical behavioral nature. Wang et al. (2022) found in their study that individuals reported feeling more guilt after conducting UPB. Similarly, multiple studies also found significant positive correlations between UPB and guilt (Khawaja et al., 2023; Liao et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2020). This association likely occurs because UPB inherently involves deceptive practices (e.g., dishonesty and concealment). Such behaviors violate individual’ internalized moral standards while simultaneously harming stakeholders’ interests. Therefore, employees will have a strong sense of guilt due to moral pressure (Chen et al., 2023; Zhao & Qu, 2022).

Beyond guilt, employees may also experience shame when engaging in unethical pro-organizational behavior (Chen & Zhang, 2024; Khawaja et al., 2023; Xu et al., 2024). Notably, although guilt and shame share conceptual similarities, guilt is more directed at the specific behavior, meaning that an individual feels guilty for immoral actions that have harmed others. While shame is more directed at the individual themselves, meaning that an individual negates their self-worth due to unethical actions (Tangney et al., 2007). Xu et al. (2024) pointed out that the implementation of unethical pro-organizational behavior can undermine an individual’s moral self-identity, thereby inducing negative self-evaluations of both conduct and self-image, thus eliciting shame.

Furthermore, anxiety is also closely related to unethical pro-organizational behavior (Li et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2021; Xu & Wang, 2020). There are multiple mechanisms for the connection between the two. On the one hand, UPB simultaneously violates moral standards (eliciting guilt), while benefiting organizational interests (generating pride). These contradictory emotions form a strong psychological conflict in the minds of employees, which leads them to repeatedly think about the consequences of their actions and have continuous concerns about the potential risks of implementing UPB (such as being punished or exposed), thereby resulting in anxiety (Liu et al., 2021). On the other hand, high work stress and performance demands can also cause employees to fall into a state of high anxiety (Gao et al., 2023). Within such anxious states, employees will have a strong sense of job insecurity, and then regard UPB as a coping strategy, increasing the possibility of UPB in employees (Li et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022).

When the cumulative negative emotions resulting from UPB reach a critical level, employees are prone to developing a composite negative affective state known as emotional exhaustion (Zhao & Qu, 2022). According to conservation of resources (COR) theory, individuals will strive to acquire, protect, and maintain their resources (e.g., emotional, cognitive, and temporal resources). However, when these resources are persistently depleted without adequate replenishment, individuals may experience stress and psychological threat (Hobfoll, 1989; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Emotional exhaustion represents the cumulative depletion of an individual’s emotional resources. Given the contradictory nature between behavioral intentions and unethical properties in UPB, employees must expend substantial emotional resources to engage in moral rationalization or regulate cognitive dissonance arising from UPB. This regulatory process may lead to excessive consumption of emotional resources, ultimately precipitating emotional exhaustion (Yang & Lin, 2024). Lawrence and Kacmar (2017) also identified a significant positive correlation between unethical pro-organizational behavior and emotional exhaustion. Moreover, when there is a lack of support and care within organization, employees are unable to effectively replenish their depleted psychological resources, leading to the persistent exacerbation of emotional exhaustion (Lawrence & Kacmar, 2017; Yao et al., 2022). Hu et al. (2021) further demonstrated that leaders’ UPB similarly triggers emotional exhaustion among employees. Liu (2024) extended this research by revealing that employees facing high-intensity time pressure and task demands are more prone to emotional exhaustion, which subsequently increases their likelihood of engaging in UPB. However, other studies have identified a significant negative correlation between emotional exhaustion and UPB in contexts involving unethical leadership and workplace bullying (Nosrati et al., 2023; Yao et al., 2022). Given these mixed findings, a comprehensive meta-analytic evaluation of the relationship between UPB and emotional exhaustion is warranted.

2.2. Emotional Responses of UPB and Subsequent Behaviors

2.2.1. Moral Cleansing Effect

Unethical pro-organizational behavior elicits divergent emotional responses in employees, with distinct affective states subsequently influencing their post-UPB conduct. Empirical evidence demonstrates that guilt following UPB implementation increases employees’ likelihood of offering constructive suggestions to compensate for ethical transgressions (Wang et al., 2022). Similarly, Zhang and Du (2023) established that post-UPB guilt reinforces organizational citizenship behaviors while diminishing self-interested unethical conduct. Chen et al. (2023) further identified guilt as a mediating mechanism between UPB and moral behaviors, on the one hand, guilt enhances employees’ customer service behavior; on the other hand, it inhibits their self-serving cheating. Overall, previous studies consistently demonstrate that after engaging in UPB, employees’ guilt fosters their prosocial behavioral tendencies (Liao et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2020).

The increased engagement in prosocial behaviors by employees, following guilt triggered by UPB, may be attributed to a moral cleansing effect. The moral cleansing effect refers to the psychological mechanism through which individuals alleviate guilt and restore their moral self-image by engaging in compensatory moral actions after committing unethical acts (Wang et al., 2022; Zhang & Du, 2023). This phenomenon essentially constitutes a manifestation of moral self-regulation, wherein the unethical nature of UPB threatens individuals’ moral self-concept. The resulting guilt from such unethical conduct subsequently motivates compensatory moral behaviors (Tracy & Robins, 2004; Zhao & Qu, 2022). For instance, an employee who concealed product defects from customers might proactively voice suggestions for product improvement to the company. This behavioral adjustment serves to alleviate guilt triggered by the initial unethical act and restore moral equilibrium. Scholars first identified this moral compensation phenomenon decades ago. Zhong et al. (2010) experimentally demonstrated that, participants primed to imagine making unethical decisions subsequently exhibited heightened moral behavior in follow-up tasks. Although moral cleansing and moral compensation share conceptual overlap (both involving increased ethical behavioral tendencies following unethical acts), moral cleansing specifically emphasizes the motivational role of negative moral emotions such as guilt. In contrast, moral compensation encompasses a broader range of behaviors aimed at restoring moral psychological equilibrium (Zhang & Du, 2023; Zhong et al., 2010). Consequently, the present study defines moral cleansing as post-UPB involving either enhanced moral conduct or reduced unethical behavior, provided that these behavioral changes are mediated by negative moral emotions (guilt and shame).

2.2.2. Moral Self-Regulation Effect

In addition to restoring moral equilibrium through increased ethical conduct, individuals engage in moral self-regulation via moral disengagement. Moral disengagement refers to the psychological process whereby individuals rationalize unethical behaviors through a set of cognitive mechanisms and strategies (Bandura, 1999). Li et al. (2018) demonstrated in their study that high performance pressure not only induces workplace anxiety and unethical pro-organizational behaviors among employees, but also elevates moral disengagement levels. Liao et al. (2023) further found that post-UPB pride, guilt, and psychological entitlement all exhibited significant positive correlations with moral disengagement.

Other studies have generally reported a significant positive relationship between psychological entitlement and moral disengagement (Lee et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2024). However, conflicting evidences from Jiang et al. (2023) and Wang et al. (2018) indicated negative correlations between guilt, psychological entitlement and moral disengagement.

Unlike moral compensation and moral cleansing effects, moral disengagement emphasizes cognitive mechanisms through which employees resolve moral self-regulatory dissonance by reconstructing cognitive appraisals. Specifically, employees may employ strategies such as moral justification, displacement of responsibility, and dehumanization to rationalize unethical behaviors (Bandura, 1999). For instance, employees might justify deceiving customers as necessary for organizational survival, attribute responsibility for UPB to supervisors by claiming coercion, or even devalue victims by perceiving clients as unsympathetic or deserving of deception (Lian et al., 2020; Wen et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2024). Consequently, this study conceptualizes the relationship between various emotions and moral disengagement as moral self-regulatory effect. Given the inconsistencies in previous research findings, it’s necessary to conduct a comprehensive evaluation of this effect.

2.2.3. Moral Slippery Slope Effect

However, the negative emotions elicited by UPB are not always effectively regulated. When self-regulation is insufficient, these negative emotions may further lead to subsequent unethical behaviors or diminish moral conduct. Liao et al. (2023) demonstrated that UPB triggers employees’ guilt, which exhibits a significant positive correlation with workplace deviance—the stronger the guilt experienced, the greater the subsequent deviant behavior. Similarly, Zhang et al. (2023) found that UPB exacerbates employees’ self-control depletion, which in turn promotes counterproductive work behaviors. Anxiety and emotional exhaustion associated with UPB also show significant positive correlations with other unethical behaviors (Nosrati et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2022). Beyond reinforcing unethical conduct, negative emotions weaken moral behaviors. Jiang et al. (2023) noted a significant negative correlation between guilt and organizational citizenship behavior, the stronger the guilt felt by employees after engaging in UPB, the weaker their propensity toward organizational citizenship behavior.

This phenomenon, where the negative emotions triggered by UPB elicit more unethical conduct or weakening ethical behaviors, can be conceptually framed as a moral slippery slope effect. The moral slippery slope effect refers to the gradual relaxation of moral standards among individuals or groups, leading to progressively increased unethical behavior (Zhao et al., 2024). It is worth noting that, although the moral slippery slope effect typically emphasizes the linkage between initial unethical acts and subsequent unethical behaviors (Welsh et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2024), this study also categorized the connection between the emotions triggered by UPB and subsequent unethical behavior as moral slippery slope effect. This is because Tangney et al. (2006) emphasized that moral behavior elicits corresponding moral emotions, which in turn influence an individual’s subsequent moral performance. As to UPB, the unethical nature of UPB obscures individuals’ perception of moral boundaries, when employees perform UPB under the pretext of benefiting the organization, their moral standards gradually erode (Zhang et al., 2023), making them more likely to exhibit self-serving unethical behaviors in the workplace. Consequently, this study attributes the relationship between UPB-induced negative emotions and unethical behavior to the moral slippery slope effect and conducts a comprehensive evaluation of its effect size.

2.2.4. Moral Licensing Effect

The positive affective states elicited by UPB (e.g., pride and psychological entitlement) may impair job performance or trigger subsequent unethical behaviors. Jiang et al. (2023) demonstrated that psychological entitlement arising from UPB significantly diminished employees’ work effort and organizational citizenship behaviors. Empirical evidences further indicate that such psychological entitlement reinforces self-interested unethical behaviors and counterproductive work behaviors (Naseer et al., 2020; Zhang & Du, 2023; Zhang et al., 2020). Researchers also found that pride positively predicts workplace deviance (Liao et al., 2023), while psychological entitlement shows significant positive correlations with prosocial rule-breaking, unethical behavior, and workplace deception (Irshad & Bashir, 2020; Liu et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2024).

This phenomenon of experiencing positive affective states after engaging in UPB, which subsequently reinforces unethical conduct or diminishes moral behaviors, can be conceptualized as the moral licensing effect. The moral licensing effect refers to the tendency for individuals to perceive themselves as having accumulated moral capital after performing moral or prosocial actions, thereby relaxing their ethical standards for subsequent behaviors and even permitting themselves to engage in unethical conduct (Dadaboyev et al., 2022; Zhang & Du, 2023). When employees commit UPB, the pro-organizational nature of such behavior leads them to perceive themselves as having contributed to the organization, thereby obtaining psychological moral licensing. This psychological license makes employees feel entitled to future unethical actions, as they believe their “moral account” has maintained sufficient moral credit due to prior pro-organizational conduct (Kong et al., 2022; Liao et al., 2023).

The core distinction between moral licensing and moral slippery slope is that, the licensing effect emphasizes the moral superiority attributed to UPB’s pro-organizational characteristics, thereby exempting individuals from subsequent misconduct, with employees experiencing positive emotional states in the process. In contrast, the moral slippery slope effect focuses on employees’ adaptational desensitization to unethical behaviors, gradually lowering sensitivity through repeated exposure and ultimately escalating unethical conduct, with employees mainly experiencing negative emotional states in the process. Therefore, this study classifies the association between positive affective states following UPB and unethical behavioral tendencies as a manifestation of the moral licensing effect, and proposes to conduct comprehensive effect analyses accordingly.

2.2.5. Conscientiousness Effect

Finally, some empirical evidences also suggest that positive emotions following UPB (such as pride and psychological entitlement) may trigger more moral behaviors or enhance work engagement. Xu et al. (2024) demonstrated that post-UPB pride positively predicts employees’ work engagement while negatively predicting job burnout. Researchers also identified significant positive correlations between psychological entitlement and positive workplace behaviors, including job performance, organizational citizenship behavior, and helping behavior (Lee et al., 2019; Shin et al., 2024; Zhang & Du, 2023).

The study conceptualizes this phenomenon as the conscientiousness effect, that is individuals who commit UPB may subsequently develop heightened organizational responsibility and willingness to contribute, driven by the positive affect arising from UPB. This likely occurs because UPB-induced positive affect leads individuals to overestimate the moral value of their actions while underestimating their detrimental consequences. Such moral purification bias may foster strong moral identification with the behavior, consequently promoting further positive workplace conduct. The fundamental distinction between the conscientiousness effect and the moral compensation effect lies in their respective motivational mechanisms. In the moral compensation effect, employees engage in ethical behaviors to restore their moral self-image, constituting an “atonement” for prior unethical conduct. Conversely, in the conscientiousness effect, employees exhibit more positive behaviors because the sense of privilege makes them believe that they have a responsibility to do more, rather than out of guilt or compensation. Accordingly, this study categorizes the relationship between positive emotional states following UPB and subsequent positive behaviors as the conscientiousness effect, and proposes to estimate the overall effect size of this relationship.

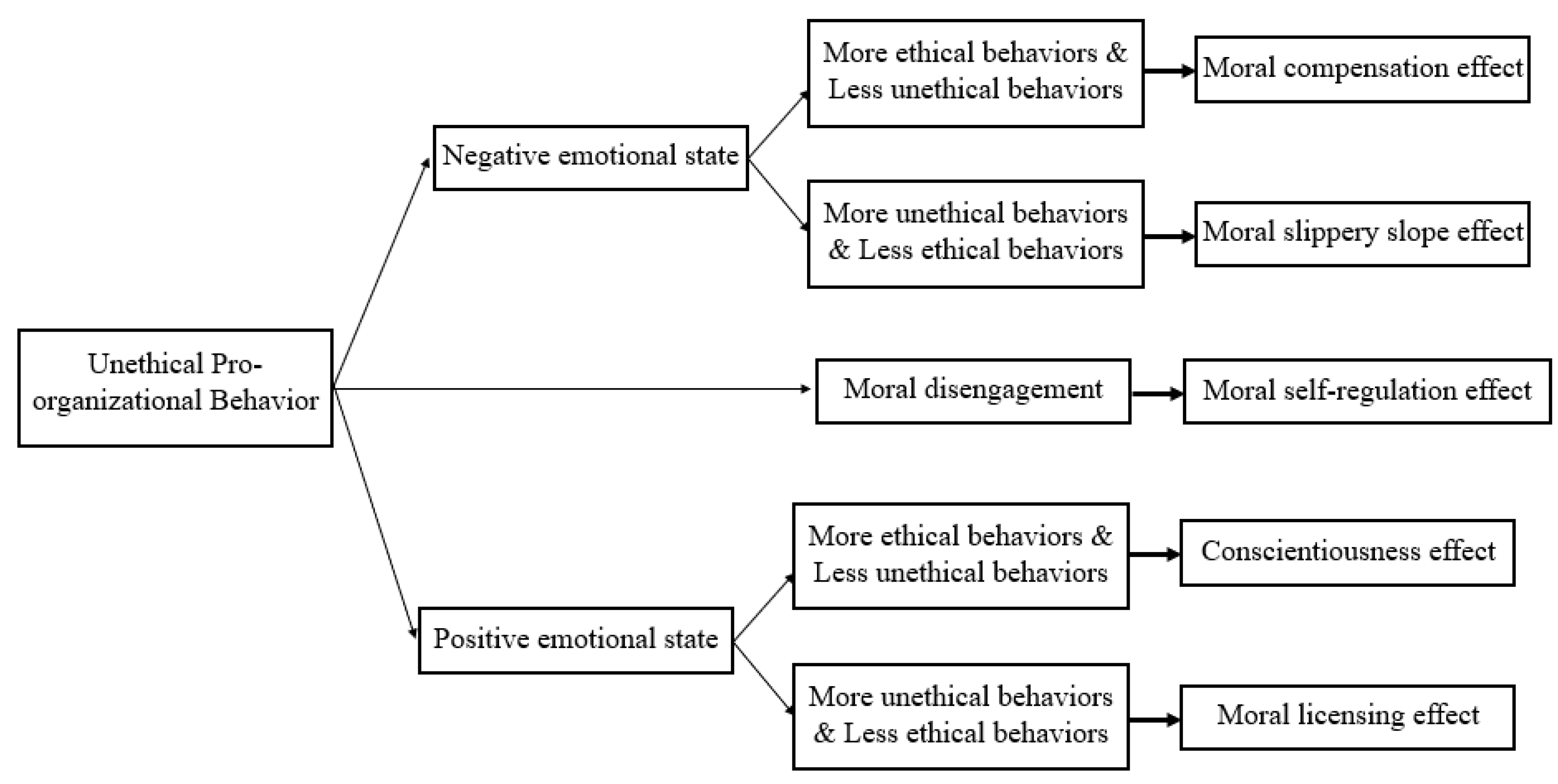

In summary, the emotional-behavioral mechanism of unethical pro-organizational behavior can be schematically represented in

Figure 1.

3. Methods

3.1. Literature Search

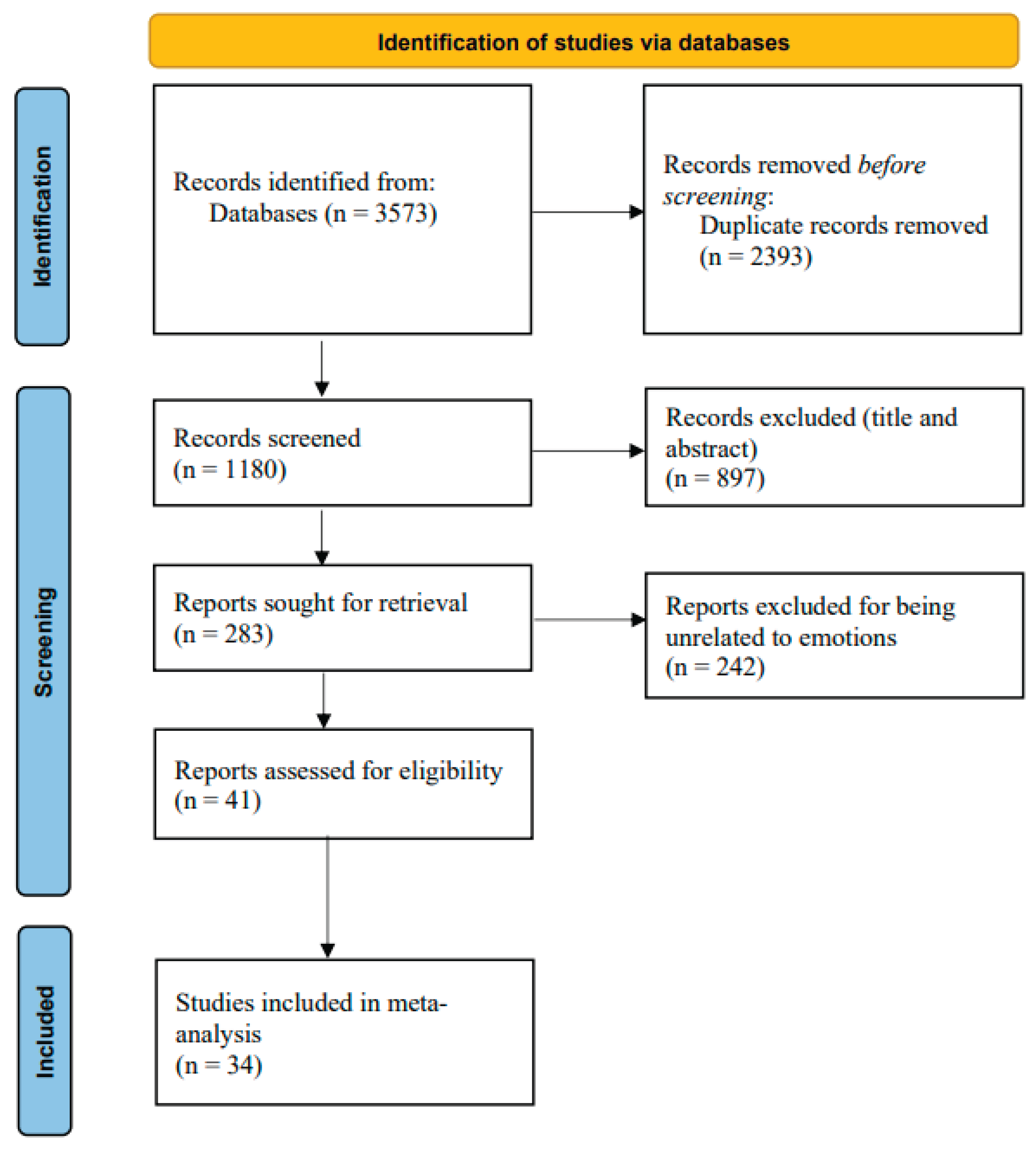

This study followed the PRISMA protocol for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (Page et al., 2021). A systematic literature search was conducted on 30 July 2024 across multiple databases, including Web of Science, EBSCO, ScienceDirect, Google Scholar, Scopus, CNKI, VIP and Wanfang Data. The study searched articles published in the aforementioned databases from 2010 onwards, using the keywords “unethical pro-organizational behavior” and “pro-organizational unethical behavior” for the English databases, using the keywords “亲组织不道德行为” and “亲组织非伦理行为” for the Chinese databases (Umphress et al., 2010, first introduced the concept of UPB in 2010). The initial search yielded 3,573 results, which were reduced to 1,180 articles after removing duplicates. Based on the following criteria: 1) publication in SSCI or CSSCI journals; 2) quantitative research design; 3) inclusion of UPB as a core variable, we identified 283 relevant studies through screening titles and abstracts. Further full-text review resulted in the selection of 41 articles that focused on UPB and emotions as core variables. However, a few studies on emotions and UPB were excluded, mainly due to insufficient independent sample sets. For instance, Hao et al. (2023) explored the relationship between depression and UPB, but the research on their relationship only had this one independent sample set, making it impossible to conduct a comprehensive effect estimation, and thus was excluded. Ultimately, 34 eligible studies were included in the meta-analysis. Details of this process follow the PRISMA protocol as outlined in

Figure 2.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Only studies that met the following criteria were selected for inclusion:

Inclusion criteria: 1) the publication language was English or Chinese; 2) the article was published in SSCI or CSSCI journals; 3) the article was quantitative research design; 4) the variables contain measures of UPB and feelings, such as guilt, pride and shame; 5) effect size were reported, or enough data were available to calculate them.

Exclusion criteria: 1) for studies of the same feelings, there are less than three independent datasets; 2) the article was published before 2010; 3) qualitative studies, literature reviews and meta-analyses were excluded.

After reading the full text, 34 articles that met the standards were finally adopted. Each article contains 1 to 4 independent studies, and ultimately 49 independent datasets related to UPB and emotions were included in the meta-analysis (as shown in the

supplementary materials).

3.3. Data Extraction and Coding

In the inclusion articles of UPB and emotional responses, the author extracted the following information: 1) NO., 2) author and publication year; 3) study No. ; 4) emotional responses; 5) sample; 6) type of the original effect size; 7) the original effect size value; 8) convert into the effect size value of Fisher’s Zr; 9) standard error. The data were shown in the

supplementary materials Table S1.

In the inclusion articles of emotional responses and behaviors, the author extracted the following information: 1) NO. ; 2) author and publication year; 3) study No. ; 4) emotional responses; 5) behaviors; 6) type of the behavior; 7) sample; 8) type of the original effect size; 9) the original effect size value; 10) convert into the effect size value of Fisher’s Zr; 11) standard error.

3.4. Quality Assessment

Given that most of the studies included in the meta-analysis were cross-sectional studies, the methodological quality of the included studies was evaluated using an 11 - item checklist endorsed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, Rostom et al., 2004). For each item, a score of “0” was assigned for responses of “NO” or “UNCLEAR”, while a score of “1” was given for “YES” responses. The quality of the articles was determined as follows: low quality = 0-3; moderate quality = 4-7; high quality = 8-11(Hu et al., 2015).

3.5. Statistical Analysis Procedure

This research categorized the included studies into two primary sets. The first set examines the relationship between unethical pro-organizational behavior and emotional responses, while the second set investigates subsequent individual behaviors following UPB and these emotional reactions. Within the first set, researchers primarily examined the magnitude of relationships between UPB and pride, guilt, shame, anxiety, emotional exhaustion, and psychological entitlement, respectively. For the second set, researchers classified subsequent behaviors into five distinct patterns: moral licensing, moral slippery slope, moral cleansing, conscientiousness effect and moral self-regulation (for behavioral classification criteria, refer to the preceding section), and separately analyzed the strength of associations between affective states and these behavioral outcomes.

The effect size statistic used in this meta-analysis is the correlation coefficient (r). Researchers extracted the correlation coefficient r from reported statistical results in original studies. If the original study didn’t not report the r value, then converted the reported effect size indices to r based on available information. However, since variance affects the pooled estimates of the effect size r, all correlation coefficients were transformed into Fisher’s Zr values prior to meta-analysis to stabilize variances (Borenstein et al., 2009), with results subsequently converted back to r for interpretation. All data were analyzed using JASP V 0.19.3.0 to merge effect sizes.

4. Results

4.1. Description of Studies

The meta-analysis included 34 studies with 112 effect sizes (48 for emotional responses and 64 for behaviors). The sample size of the research ranged from 62 to 674, and the participants were mainly employed employees. The quality of the included studies was assessed through AHRQ. The results showed that 4 studies were of low quality, 27 studies were of moderate quality, and 3 studies were of high quality.

4.2. Heterogeneity Test

The heterogeneity tests were conducted to assess the variability in study outcomes. In this research, the Q value and the I2 statistic are used to assess heterogeneity. The Q value assesses the presence of heterogeneity, while the I2 quantifies the proportion of total variance in the effect size attributable to between-study heterogeneity. For I2, Higgins et al. (2003) suggested that, values approximating 25%, 50%, and 75% may be indicative of low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. The results of the heterogeneity test are presented in

Table 1. It indicates that the Q value for 6 emotional responses and 5 behavioral effects were statistically significant, suggesting a substantial heterogeneity across the studies. The Q statistic reached a significant level (p < .001), and the I2 value exceeded 75%, which indicates strong heterogeneity among the studies. Given the high level of heterogeneity across studies and the relatively limited number of studies and sample sizes, the study employed the Paule-Mandel method to estimate the composite effect size (Bakbergenuly et al., 2019, 2020).

4.3. Publication Bias Analysis

Publication bias refers to the phenomenon of effect size deviation due to the higher likelihood of studies with statistically significant results being published (Rothstein et al., 2005). The study used the fail-safe N to test the impact of possible publication bias on the relationships between variables. The results are shown in

Table 2. Except for the emotional exhaustion, the fail-safe N of the other groups of relationships far exceeded the critical value (5K+10, K represents the number of independent samples), proving that there was no serious publication bias problem in this study.

4.4. Overall Effect Size Estimation

The study employed the Paule-Mandel method to estimate the composite effect sizes across groups, with detailed results presented in

Table 3. According to Cohen’s criteria (1988), values below 0.19 indicate a very weak correlation; 0.20 to 0.39, a weak correlation; 0.40 to 0.59, a moderate correlation; and above 0.60, a strong correlation.

The meta-analytic results revealed that in the composite effect estimation from unethical pro-organizational behavior to affective responses, all measured emotional states except emotional exhaustion demonstrated weak correlations with UPB (r = 0.261–0.339), with 95% confidence intervals excluding zero. This suggests statistically significant yet weak associations between UPB and these affective responses. Emotional exhaustion showed no significant correlation with UPB (z = -0.451, p=0.652).

Regarding the composite effect estimation from affective responses to subsequent UPB behaviors, all group effect sizes fell within the 0.233–0.328 range, 95% CIs excluding zero, indicating consistent albeit weak manifestations of moral licensing, moral compensation, moral decoupling, moral self-regulation, and conscientiousness effects following UPB enactment.

5. Discussion

5.1. Positive Emotions Elicited by UPB and Subsequent Behavioral Mechanisms

Overall, this study identified stable positive correlations between unethical pro-organizational behavior and pride, guilt, shame, anxiety, and psychological entitlement. Regarding positive affect, UPB may elicit both pride and psychological entitlement in employees. This phenomenon likely occurs because employees perceive heightened pro-organizational intentionality in UPB, attributing resultant organizational benefits to personal accomplishment while framing their unethical conduct as sacrificial acts for organizational benefits (Liu et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2020). Under the inspiration of these positive emotions, employees will have a sense of pride and privilege, that is, since they have already made so many contributions to the organization, they are more entitled to be exempted when they engage in unethical behavior (Zhang & Du, 2023). This psychological cascade, where UPB-induced pride generates perceived justification for future misconduct, constitutes the moral licensing effect.

In addition to triggering moral licensing effect, positive emotions may also engender conscientiousness effects. Specifically, employees experience positive emotions (pride and psychological entitlement) following UPB, which subsequently reinforces their organizational identification and engagement. This might because not only employees recognizing their contributions to the organization at elevated levels, but also developing a strong perception of being indispensable organizational members. Such positive affective states motivate them to make further organizational contributions (e.g., exhibiting increased innovative behaviors and organizational citizenship behaviors) (Irshad & Bashir, 2020; Shin et al., 2024).

5.2. Negative Emotions Elicited by UPB and Subsequent Behavioral Mechanisms

Unethical pro-organizational behavior elicits various negative affect states in actors, including guilt, shame, anxiety, and emotional exhaustion. This occurs because UPB’s unethical nature violates fundamental moral standards and behavioral norms (Umphress et al., 2010; Umphress & Bingham, 2011). When UPB causes harm to others, employees will then experience a sense of guilt; and when UPB damages the moral self-image of the employees, shame will arise (Wang et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2024). Anxiety and emotional exhaustion are more complex negative emotions. When UPB elicits both pride and guilt in employees, the conflicting feelings consequently induce anxiety, which makes employees worry about the consequences of UPB (Liu et al., 2021). In addition, unique work environments can also influence employees’ anxiety. For instance, high time pressure and job demands are likely to trigger anxiety, and in such cases, employees are more prone to engage in UPB to cope with the stress (Gao et al., 2023; Li et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2022).

However, the relationship between emotional exhaustion and UPB is relatively weak, as the combined effect estimation indicates no significant correlation between the two. On the one hand, this may be because the connection between emotional exhaustion and UPB is primarily mediated through indirect pathways. For instance, when job insecurity serves as an antecedent variable, emotional exhaustion significantly mediates its relationship with UPB, yet the direct association between job insecurity and UPB is insignificant (Lawrence & Kacmar, 2017). On the other hand, given that emotional exhaustion is a complex emotional state, its relationship with UPB is notably influenced by situational factors. Liu (2024) discovered that job complexity moderates the relationship between emotional exhaustion and UPB, when job complexity is high, the relationship between UPB and emotional exhaustion is not significant; in contrast, when job complexity is low, emotional exhaustion can positively predict employees’ UPB.

There are two primary behavioral mechanisms through which the aforementioned negative emotions influence subsequent UPB: the moral slippery slope and the moral cleansing effect. The moral slippery slope occurs as employees gradually relax their ethical standards while engaging in UPB. As they become accustomed to unethical behavior patterns, they are more likely to participate in immoral actions subsequently (Yang et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2024). It is important to note, however, that the occurrence of the moral slippery slope is also influenced by the organizational environment. If leaders condone employees’ involvement in UPB, employees will perceive unethical behavior as acceptable within the organization and are more likely to engage in other unethical actions (Dennerlein & Kirkman, 2022; Xu et al., 2024).

The moral cleansing effect refers to the process in which employees, driven by guilt after engaging in UPB, attempt to repair their moral self-image through ethical behaviors. The essence of this effect is that employees will engage in more altruistic behaviors following UPB to compensate for the harm caused by UPB and thereby restore moral balance (Wang et al., 2022; Zhang & Du, 2023). The moral cleansing effect actually shares common ground with the moral licensing effect. The moral credential model emphasizes that individuals will establish and maintain their moral self-image through past moral behaviors (Monin & Miller, 2001). Past good deeds are like accumulating moral credits for oneself. Due to the accumulation of moral credit, individuals grant themselves psychological permission to engage in unethical behaviors (Shi, 2011). The moral cleansing effect can also be explained by the moral credential model as follows, since UPB behavior undermines the individual’s moral credits, employees need to engage in more moral behaviors to accumulate moral credit and maintain their moral self-image.

Finally, there is a stable relationship between the moral emotions generated by UPB and moral disengagement. Regardless of whether individuals experience positive or negative emotions after engaging in UPB, they may resort to moral disengagement to excuse their unethical behavior. Zhang et al. (2023) noted that employees may rationalize UPB through moral disengagement by engaging in cognitive restructuring to release moral self-restraint. The unique nature of UPB enables employees to trigger the mechanism of moral disengagement. Although UPB may harm others, its pro-organizational motivation provides employees with a good moral excuse. This allows employees to reduce self-reproach and instead regard unethical behavior as an acceptable sacrifice (Graham et al., 2020; Lian et al., 2020).

5.3. Theoretical and Practical Implications

On a theoretical level, the present study delved into the emotional response pathways elicited by UPB. It not only disentangled the differential impacts of positive and negative emotions triggered by UPB, but also further unveiled the potential behavioral mechanisms that may ensue after UPB and the associated emotions, such as the moral cleansing and moral licensing effects. The paradoxical nature of UPB, as reflected in the conflicting positive and negative emotions and their divergent influences on subsequent behaviors, provides an integrative framework for explaining the contradictory aspects of UPB.

In terms of practical significance, the moral slippery slope and moral licensing effects triggered by UPB suggest that people should be vigilant about the moral risks associated with UPB. On the one hand, organizations should place emphasis on the development of an ethical climate, incorporating ethical norms into daily management to enhance employees’ ethical awareness (Xu et al., 2024). On the other hand, given that leaders’ UPB can elicit imitation from organizational members, it is also necessary to strictly monitor and manage unethical behaviors among the management to prevent the transmission of a self-interested ethical climate (Azhar et al., 2024; Lian et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2018). Although the moral cleansing and conscientiousness effects may lead employees to engage in more positive behaviors, the fact remains that employees have still participated in UPB. Tolerance of UPB essentially depletes the organization’s moral capital. Therefore, organizations can provide ethical training and moral decision-making simulations to train employees to identify potential ethical risks in conflicts of interest and to cultivate a positive organizational identification among employees.

5.4. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

Despite the comprehensive effect analysis of emotions and behavioral mechanisms following UPB have be conducted in this study, several limitations remain. First, this meta-analysis did not include all studies on UPB and emotions. For example, Hao et al. (2023) found in their research that depression caused by UPB can reduce employee job performance. However, this was not analyzed in the present study. This is because there is only one study on the relationship between UPB and depression, which is insufficient for a comprehensive effect estimation. Nevertheless, we cannot deny the association between UPB and depression as well as other emotions such as anger (Hao et al., 2023; Xu & Wang, 2020).

However, Tangney et al. (2007) indicated that in addition to emotions such as shame, guilt, and pride, embarrassment, anger, gratitude, and admiration are also common moral emotions, and these moral emotions can influence individuals’ subsequent moral behavior. For example, admiration and gratitude can motivate people to engage in moral actions, while anger and contempt may lead to aggressive behaviors. In research on the relationship between UPB and emotions, scholars have found that hindrance stressors had a positive effect on UPB through the mediation of anxiety and anger (Xu & Wang, 2020). However, whether UPB itself can elicit anger remains unknown. Tang et al. (2021) discovered that employees who observed others engaging in UPB might experience two types of emotional reactions: admiration and disgust. When individuals admired the UPB actor, they were more likely to offer help to the actor. In contrast, when individuals felt disgusted by the UPB actor, they might report the behavior or avoid interacting with the actor. This suggests that in addition to the emotional-behavioral mechanisms discussed in this paper, UPB may also trigger other emotional-behavioral mechanisms, such as the disgust-avoidance mechanism or the admiration-imitation mechanism. Future research can further explore the associations between UPB and other emotions, as well as the underlying emotional-behavioral mechanisms.

Secondly, in terms of emotion measurement, most studies have relied on scales to assess employees’ emotional responses. This retrospective self-report method is prone to biases in memory, Robins et al. (2007) indicated that self-reported emotion scales have difficulty differentiating between transient emotional fluctuations and stable emotional dispositions. Moreover, given that UPB is a behavior that violates general social moral norms, it is more “appropriate” to exhibit guilt in response to such behavior. Therefore, in experimental and survey contexts, participants are easily influenced by social desirability (Persson et al., 2025), leading to performative emotions. To reduce bias, future researchers may consider employing multi - time - point measurements or combining physiological indicators (such as heart rate and skin conductance response) to assist in verifying participants’ emotional changes. Alternatively, Gabriel et al. (2019) recommended using the Experience Sampling Method (ESM) to capture emotional changes in real-time, rather than relying solely on retrospective self-reports.

Finally, during the process of literature search and coding, the researchers found that the majority of studies on UPB and emotional reactions came from China, with a significant lack of researches and samples from other countries. Moreover, the expression of moral emotions varies across different cultures. Some scholars have pointed out that Eastern cultures place a greater emphasis on a culture of shame, in which people experience more shame and embarrassment due to unethical behavior; while Western cultures emphasize a culture of guilt, in which people feel a sense of guilt when engaging in unethical actions (Ren & Gao, 2011). Therefore, it can be inferred that the strength of the relationship between UPB and guilt and shame may differ between Eastern and Western cultures. Therefore, the cross-cultural applicability of the meta-analysis results is open to question. Future research may attempt to replicate the aforementioned emotional and behavioral mechanisms in different cultural contexts.

6. Conclusions

The present study systematically elucidated the mechanisms through which unethical pro-organizational behavior influences the actor’s emotions and subsequent behaviors. First, UPB can elicit feelings of pride and psychological entitlement in individuals, and trigger the moral licensing effect (rationalizing subsequent unethical behavior) and the conscientiousness effect (enhancing organizational identification and promoting positive behaviors). Second, the negative emotions such as guilt, shame, and anxiety caused by UPB can drive the moral slippery slope effect (lowering moral standards and engaging in more unethical behaviors) and the moral cleansing effect (repairing self-image through moral behaviors). Finally, as a self-regulatory mechanism, moral disengagement permeates the entire process of UPB, with employees resorting to moral disengagement to resolve the moral conflicts elicited by UPB.

Author Contributions

Zou. L.M. and Wang. Y.X.; literature research, Zou. L.M., Wang. Y.X. and Liu. C.J.; data coding, Zou. L.M.; data analysis, Zou. L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Zou. L.M. and Liu. C.J.; writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grand number 72101171.

Data Availability Statement

The data detail is available at:

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UPB |

Unethical pro-organizational behavior |

| EE |

Emotional exhaustion |

| PE |

Psychological entitlement |

| COR |

Conservation of resources |

References

- Azhar, S.; Zhang, Z.; Simha, A. Leader unethical pro-organizational behavior: an implicit encouragement of unethical behavior and development of team unethical climate. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 23597–23610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakbergenuly, I.; Hoaglin, D.C.; Kulinskaya, E. Estimation in meta-analyses of mean difference and standardized mean difference. Stat. Med. 2019, 39, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakbergenuly, I.; Hoaglin, D.C.; Kulinskaya, E. Estimation in meta-analyses of response ratios. BMC Med Res. Methodol. 2020, 20, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Moral Disengagement in the Perpetration of Inhumanities. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 3, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Effect Sizes Based on Correlations. In Introduction to Meta-Analysis (pp. 41-43). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, W.K.; Bonacci, A.M.; Shelton, J.; Exline, J.J.; Bushman, B.J. Psychological Entitlement: Interpersonal Consequences and Validation of a Self-Report Measure. J. Pers. Assess. 2004, 83, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, S. Employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior and subsequent internal whistle-blowing. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2024, 19, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, C.C.; Schminke, M. Feeling Guilty and Entitled: Paradoxical Consequences of Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior. J. Bus. Ethic- 2022, 183, 865–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Chen, C.C.; Sheldon, O.J. Relaxing moral reasoning to win: How organizational identification relates to unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadaboyev, S.M.U.; Choi, S.; Paek, S. Why do good soldiers in good organizations behave wrongly? The vicarious licensing effect of perceived corporate social responsibility. Balt. J. Manag. 2022, 17, 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennerlein, T.; Kirkman, B.L. The hidden dark side of empowering leadership: The moderating role of hindrance stressors in explaining when empowering employees can promote moral disengagement and unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2022, 107, 2220–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.S.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Beal, D.J.; Scott, B.A.; Sonnentag, S.; Trougakos, J.P.; Butts, M.M. Experience Sampling Methods: A Discussion of Critical Trends and Considerations for Scholarly Advancement. Organ. Res. Methods 2018, 22, 969–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z. H., Zhang, H., Xu, Y., & Chen, J. Y. (2023). Perceived Leader Dependence and Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior—A Moderated Chain Mediation Model. Research on Economics and Management, 44(4), 131-144. [CrossRef]

- A Graham, K.; Resick, C.J.; A Margolis, J.; Shao, P.; Hargis, M.B.; Kiker, J.D. Egoistic norms, organizational identification, and the perceived ethicality of unethical pro-organizational behavior: A moral maturation perspective. Hum. Relations 2019, 73, 1249–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Sui, Y.; Yan, Q. Unethical pro-organizational behavior and task performance: a moderated mediation model of depression and self-reflection. Ethic- Behav. 2023, 34, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E.; Halbesleben, J.; Neveu, J.-P.; Westman, M. Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2018, 5, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D. M., He, L. F., & Chen, M. (2021). Leader’s Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior and Employee’s Emotional Exhaustion: A Cognitive Appraisal of Emotions Perspective. Human Resources Development of China, 38(10), 64-77. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Dong, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Ma, D.; Liu, X.; Zheng, R.; Mao, X.; Chen, T.; He, W. Prevalence of suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Compr. Psychiatry 2015, 61, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, M.; Bashir, S. The Dark Side of Organizational Identification: A Multi-Study Investigation of Negative Outcomes. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 572478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Liang, B.; Wang, L. The Double-Edged Sword Effect of Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior: The Relationship Between Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Work Effort. J. Bus. Ethic- 2022, 183, 1159–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelebek, E.E.; Alniacik, E. Effects of Leader-Member Exchange, Organizational Identification and Leadership Communication on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: A Study on Bank Employees in Turkey. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khawaja, K.F.; Sarfraz, M.; Khalil, M. Doing good for organization but feeling bad: when and how narcissistic employees get prone to shame and guilt. Futur. Bus. J. 2023, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, M.; Xin, J.; Xu, W.; Li, H.; Xu, D. The moral licensing effect between work effort and unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating influence of Confucian value. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2020, 39, 515–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.R.; Kacmar, K.M. Exploring the Impact of Job Insecurity on Employees’ Unethical Behavior. Bus. Ethic- Q. 2016, 27, 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.S. Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. Am. Psychol. 1991, 46, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Schwarz, G.; Newman, A.; Legood, A. Investigating When and Why Psychological Entitlement Predicts Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior. J. Bus. Ethic- 2017, 154, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. C., Wang, Z., Zhu, Z. B., & Zhan, X. J. (2018). Performance Pressure and Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: Based on Cognitive Appraisal Theory of Emotion. Chinese Journal of Management, 15(3), 358-365. [CrossRef]

- Lian, H.; Huai, M.; Farh, J.-L.; Huang, J.-C.; Lee, C.; Chao, M.M. Leader Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior and Employee Unethical Conduct: Social Learning of Moral Disengagement as a Behavioral Principle. J. Manag. 2020, 48, 350–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Yam, K.C.; Lee, H.W.; Johnson, R.E.; Tang, P.M. Cleansing or Licensing? Corporate Social Responsibility Reconciles the Competing Effects of Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior on Moral Self-Regulation. J. Manag. 2023, 50, 1643–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. How does temporal leadership affect unethical pro-organizational behavior? The roles of emotional exhaustion and job complexity. Kybernetes 2024, ahead-of-p. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, F. Moral decline in the workplace: unethical pro-organizational behavior, psychological entitlement, and leader gratitude expression. Ethic- Behav. 2021, 32, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.L.; Lu, J.G.; Zhang, H.; Cai, Y. Helping the organization but hurting yourself: How employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior predicts work-to-life conflict. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2021, 167, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, D.M.; Kuenzi, M.; Greenbaum, R.L. Examining the Link Between Ethical Leadership and Employee Misconduct: The Mediating Role of Ethical Climate. J. Bus. Ethic- 2010, 95, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Ghosh, K.; Sharma, D. Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior: A Systematic Review and Future Research Agenda. J. Bus. Ethic- 2021, 179, 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.; Lupoli, M.J.; Newman, A.; Umphress, E.E. Good intentions, bad behavior: A review and synthesis of the literature on unethical prosocial behavior (UPB) at work. J. Organ. Behav. 2022, 44, 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, B.; Miller, D.T. Moral credentials and the expression of prejudice. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, S.; Bouckenooghe, D.; Syed, F.; Khan, A.K.; Qazi, S. The malevolent side of organizational identification: unraveling the impact of psychological entitlement and manipulative personality on unethical work behaviors. J. Bus. Psychol. 2019, 35, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosrati, S.; Talebzadeh, N.; Ozturen, A.; Altinay, L. Investigating a sequential mediation effect between unethical leadership and unethical pro-family behavior: testing moral awareness as a moderator. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2023, 33, 308–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement : an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persson, H.; Björklund, F.; Bäckström, M. How Social Desirability Influences the Relationship between Measures of Personality and Key Constructs in Positive Psychology. J. Happiness Stud. 2025, 26, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J. & Gao, X. X. (2011). Moral Emotions: The Moral Behavior’s Intermediary Mediation. Advances in Psychological Science, 19(8), 1224-1232. [CrossRef]

- Robins, R. W., Noftle, E. E., & Tracy, J. L. (2007). Assessing self conscious emotions: A review of self-report and nonverbal measures. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.). The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 443–467). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Rothstein, H. R., Sutton, A. J., & Borenstein, M. (2005). Publication bias in meta-analysis. In H. R., Rothstei, A. J., Sutton, & M. Borenstein (Eds.), Publication bias in meta-analysis: Prevention, assessment & adjustments (pp. 1-7). Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. J: Chichester, England.

- Rostom, A., Dubé, C., Cranney, A., Saloojee, N., Sy, R., Garritty, C., et al. Celiac Disease. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2004 Sep. (Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 104.) Appendix D. Quality Assessment Forms. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK35156/.

- Shi, W. (2011). A Review of the Research on Moral Psychological Licensing. Advances in Psychological Science, 19(8), 1233-1241. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hur, W.-M.; Kang, D.Y.; Shin, G. Why pro-organizational unethical behavior contributes to helping and innovative behaviors: the mediating roles of psychological entitlement and perceived insider status. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 25135–25152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, L.M.; Rees, R.; Berry, C.M. The role of self-interest in unethical pro-organizational behavior: A nomological network meta-analysis. J. Appl. Psychol. 2024, 109, 362–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, P.M.; Yam, K.C.; Koopman, J. Feeling proud but guilty? Unpacking the paradoxical nature of unethical pro-organizational behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2020, 160, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Mashek, D.; Stuewig, J. Working at the Social–Clinical–Community–Criminology Interface: The George Mason University Inmate Study. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2007, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangney, J.P.; Stuewig, J.; Mashek, D.J. Moral Emotions and Moral Behavior. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 345–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. TARGET ARTICLE: "Putting the Self Into Self-Conscious Emotions: A Theoretical Model". Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.L.; Robins, R.W. The psychological structure of pride: A tale of two facets. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 506–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B. When Employees Do Bad Things for Good Reasons: Examining Unethical Pro-Organizational Behaviors. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B.; Mitchell, M.S. Unethical behavior in the name of the company: The moderating effect of organizational identification and positive reciprocity beliefs on unethical pro-organizational behavior. J. Appl. Psychol. 2010, 95, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, B.; Cullen, J.B. The Organizational Bases of Ethical Work Climates. Adm. Sci. Q. 1988, 33, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. M., Zhang, M. S., Zhao, S. M., & Li, L. (2020). Idiosyncratic deals and core employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior: Social cognitive theory perspective. Journal of Industrial Engineering, 34(4), 44-51. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Y., Tian, H., & Xing, H. W. (2018). Research on Internal Auditors’ Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior: From the Perspective of Dual Identification. Journal of Management Science, 31(4), 30-44. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Liu, G.; Zhou, Q. Compulsory unethical pro-organisational behaviour and employees’ in-role performance: a moderated mediation analysis. J. Psychol. Afr. 2022, 32, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Long, L.; Zhang, Y.; He, W. A Social Exchange Perspective of Employee–Organization Relationships and Employee Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior: The Moderating Role of Individual Moral Identity. J. Bus. Ethic- 2018, 159, 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Ren, R. A Moral Cleansing Process: How and When Does Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior Increase Prohibitive and Promotive Voice. J. Bus. Ethic- 2021, 176, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, D.T.; Ordóñez, L.D.; Snyder, D.G.; Christian, M.S. The slippery slope: How small ethical transgressions pave the way for larger future transgressions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, P.; Chen, C.; Chen, S.; Cao, Y. The Two-Sided Effect of Leader Unethical Pro-organizational Behaviors on Subordinates’ Behaviors: A Mediated Moderation Model. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 572455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, J. Influence of Challenge–Hindrance Stressors on Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior: Mediating Role of Emotions. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wen, T.; Wang, J. How does job insecurity cause unethical pro-organizational behavior? The mediating role of impression management motivation and the moderating role of organizational identification. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 941650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Yaacob, Z.; Cao, D. Casting light on the dark side: unveiling the dual-edged effect of unethical pro-organizational behavior in ethical climate. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 43, 14448–14469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.-H.; Lin, Y.-J. Job demands and employees’ unethical pro-organizational behaviors: Emotional exhaustion as a mediator. Soc. Behav. Pers. Int. J. 2024, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Lin, C.; Liao, Z.; Xue, M. When Moral Tension Begets Cognitive Dissonance: An Investigation of Responses to Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior and the Contingent Effect of Construal Level. J. Bus. Ethic- 2021, 180, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Luo, J.; Fu, N.; Zhang, X.; Wan, Q. Rational Counterattack: The Impact of Workplace Bullying on Unethical Pro-organizational and Pro-family Behaviors. J. Bus. Ethic- 2021, 181, 661–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, X.L.; Cai, Y.; Sun, X. Paved with Good Intentions: Self-regulation Breakdown After Altruistic Ethical Transgression. J. Bus. Ethic- 2022, 186, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Du, S. Moral cleansing or moral licensing? A study of unethical pro-organizational behavior’s differentiating Effects. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2022, 40, 1075–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; He, B.; Sun, X. The Contagion of Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior: From Leaders to Followers. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y. J., Sun, Y. D., & Li, Y. X. (2022). Demand Paying Back or Seek Paying Forward: The Influence of Job Insecurity on Unethical Behavior. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 30(4), 837-841. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. J. , Zhao, J., & Liu, Z. Q. (2020). Research on the Self-Interested Risk of Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior and Its Mechanisms. Chinese Journal of Management, 17(11), 1642-1650. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Qu, S. Research on the consequences of employees’ unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating role of moral identity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1068606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Qu, S.; Tian, G.; Mi, Y.; Yan, R. Research on the moral slippery slope risk of unethical pro-organizational behavior and its mechanism: a moderated mediation model. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 17131–17145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. W., Yang, G. K., Xiao, J. C., & Liu, X. M. (2024). Mechanisms of Star Employees’ Unethical Pro-organizational Behavior from the Perspective of Cognitive Appraisal Theory of Emotion. Soft Science, 38(3), 123-128. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.-B.; Ku, G.; Lount, R.B.; Murnighan, J.K. Compensatory Ethics. J. Bus. Ethic- 2009, 92, 323–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).