1. Introduction

The growth in energy demand, coupled with concerns about sustainability, has significantly boosted the integration of renewable sources into the electricity system. Among the most promising solutions are hybrid systems made up of solar photovoltaic generation, wind power, and battery storage [

1,

2]. These configurations, known as distributed generation systems, can operate autonomously or be connected to the main electricity grid, promoting greater efficiency and resilience in the supply of electricity. In order for these systems to be technically viable and economically attractive, they must be optimally sized. This means minimizing investment and operating costs, as well as greenhouse gas emissions (such as CO

2) while ensuring high levels of operational reliability. In addition, regulatory policies and charging mechanisms linked to interaction with the electricity grid, such as charging for exported energy, have become integrated components in the energy planning of hybrid systems. This reinforces the importance of broader, integrated, and multi-objective optimization approaches.

Various optimization methods have been used in the literature to achieve this balance, including heuristic algorithms such as PSO (Particle Swarm Optimization), GA (Genetic Algorithms), and MILP (Mixed Integer Linear Programming), as well as specialized computational tools such as HOMER and GAMS. A notable example is the study by Ismail et al. [

3], which proposes an optimization model based on genetic algorithms for designing hybrid systems composed of photovoltaic (PV) panels, microturbines (or diesel generators), and battery banks. The study’s aim is to minimize the cost of energy generated (COE), reduce polluting emissions, and ensure a continuous supply to small rural communities located in Palestine. In a similar vein, Yang et al. [

4] developed a GA-based optimization model for solar-wind-battery systems, using the annualized cost of the system (ACS) as the economic metric and the loss of load probability (LPSP) as the technical criterion. The actual application of the model to a telecommunications station demonstrated consistent performance throughout the year, with an LPSP of less than 2%, reinforcing the potential of this approach for remote areas. Complementing this panorama, Dufo-López and Bernal-Agustín [

5] proposed a multi-objective optimization framework for complex hybrid systems (PV, wind, diesel, hydrogen, and batteries), using the SPEA algorithm to simultaneously minimize total system cost (NPC),

emissions, and unserved load (UL). The model generates a set of Pareto solutions, offering the designer flexibility to choose between multiple technically feasible and environmentally sustainable alternatives.

Recently, Paulitschke et al. [

6] proposed an optimization model that simultaneously integrates component sizing and energy management control parameters in PV-battery-hydrogen hybrid systems. The study introduces an enhanced particle swarm algorithm (EPSO), capable of dealing with the complexity and non-linearity of the problem, including invalid regions in the search space. Another approach that has been gaining prominence in recent years is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) for dimensioning in hybrid systems. For example, in [

7], a new framework for optimal sizing of autonomous hybrid energy systems (photovoltaic, wind, and hydrogen) was proposed. This approach incorporates weather forecasts and a hybrid heuristic algorithm based on chaotic search, harmony search, and simulated annealing, aided by artificial neural networks for predicting solar radiation, ambient temperature, and wind speed. The study shows that combining weather forecasts via an artificial neural network (ANN) with a hybrid search algorithm significantly improves the sizing of hybrid off-grid systems. Along the same lines, Zhang et al. [

8] developed an optimization approach based on hybrid simulated annealing (HCHSA), combining harmonic and chaotic search techniques, for the optimal sizing of PV/wind hybrid systems with battery and hydrogen storage. The model considers four decision variables, areas of solar collectors and wind rotors, number of batteries and hydrogen tanks, with the aim of minimizing the life cycle cost (LCC) of the system. Applied to a remote region in Iran, the study evaluated six different hybrid system configurations. The results indicated that the solar/wind combination with batteries offers the best technical-economic performance, even outperforming systems with hydrogen storage.

In remote locations such as Sabah, Malaysia, electrification still depends mostly on isolated diesel generators, which are associated with high fuel costs and significant environmental impacts. The adoption of hybrid systems with photovoltaic panels and batteries has emerged as a promising alternative to increase supply reliability, reduce emissions, and lower the levelized cost of energy (LCOE). In [

9]’s study, specialized HOMER software was used to model and compare different generation scenarios, including pure diesel arrangements, PV/diesel/battery hybrid systems (in current and optimized configurations), and a 100% PV/battery-based system, with a focus on evaluating technical, economic and environmental performance. The optimized PV/diesel/battery hybrid system presents the best compromise between reliability, cost, and environmental impact. The 100% PV/battery scenario, although emission-free, is still economically unviable due to the high investment costs in PV and batteries. In addition, Sen and Bhattacharyya [

10] propose a comprehensive approach for sizing and evaluating hybrid off-grid systems in remote villages. Also using the HOMER software, the authors modeled different combinations of micro-hydropower, solar panels, wind turbines, and biodiesel generators, seeking to identify the most technically reliable and economically viable solution.

Complementing this perspective, Gu et al. [

11] propose a techno-economic evaluation model for PV/T solar concentrators applied to the building sector in Sweden, using Monte Carlo simulation techniques to incorporate uncertainties associated with technical and financial variables. The study analyzes the combined impacts of 11 critical parameters, such as solar radiation, interest and inflation rates, collector efficiency, and cost of capital, on metrics such as levelized cost of energy (LCOE), net present value (NPV), and payback. The reference configuration analyzed achieves an average LCOE of 1.27 SEK/kWh, a positive NPV of approximately 1,880 euros, and an estimated payback period of 10 years.

Based on the literature reviewed, there is a consolidated trend towards the use of genetic algorithms as an effective optimization method for sizing the components of hybrid systems, especially when it comes to selecting the most efficient configurations between components such as photovoltaic panels, wind turbines, storage systems, and auxiliary generators. Works such as those by Ismail et al. [

3], Yang et al. [

4] and Dufo-López and Bernal-Agustion [

5] demonstrate that the GA is capable of exploring complex and non-linear solution spaces, allowing optimal arrangements to be found that minimize indicators such as the levelized cost of energy (LCOE),

emissions and the probability of load shedding (LPSP). In addition, many of these studies consider the use of diesel generators as an integral part of hybrid solutions, not only because of their reliability but also to guarantee load service in critical scenarios, especially in isolated regions. However, arrangements that combine renewable sources with well-designed storage tend to significantly reduce the time of use and costs associated with fossil generators [

9,

10]. Another recurring aspect is the emphasis on maximizing net present value (NPV) as the main metric of economic attractiveness. Studies such as those by Gu et al. [

11] and Zhang et al. [

8] reinforce that considering discounted cash flows over the useful life of the system allows for a more realistic assessment of the viability of the project, especially when variables such as inflation, interest rates, operating costs, and climatic uncertainties are incorporated.

On the other hand, conventional wind systems connected to the grid, such as turbines with synchronous generators or double-fed generators controlled by converters, still present challenges such as high maintenance costs, degradation of power quality due to harmonics, and the complexity of power converters [

1,

12,

13]. In this scenario, the electromagnetic frequency regulator (EFR) has emerged as an innovative alternative, with the potential to mitigate harmonics and facilitate direct hybridization with auxiliary sources via the DC bus of your inverter [

1,

14,

15,

16]. The ERF’s architecture, based on an induction machine with a rotating armature, makes it possible to convert variable wind speeds into frequencies compatible with the electricity grid, promoting greater electromechanical robustness and integration with hybrid systems.

This paper proposes the sizing and technical-economic analysis of a hybrid renewable energy system (HRES) made up of photovoltaic panels, wind turbines, a diesel generator, and a battery bank (BB), to be applied to UFRN’s Macau Campus and connected to the electricity grid. Inspired by the approach of Delson et al. [

17], three improvements are made to the computational model: (i) adjustment of the temperature coefficients of the PV modules and incorporation of shading and degradation losses; (ii) parameterization of the turbine power curve considering aerodynamic corrections; and (iii) hourly simulation integrated with the evolution of the state of charge (SoC) of the batteries. A genetic algorithm is then used to simultaneously optimize the installed capacity of each component in order to maximize the net present value (NPV) over 20 years. Finally, we carry out a comparative study of the results obtained with the proposed method and with the sizing originally presented by Delson et al. [

17], highlighting gains in cash flow accuracy and economic viability.

This article is organized as follows:

Section 1 presents the introduction, including motivation, objectives, and a brief literature review;

Section 2 describes in detail the grid-connected hybrid system, its components (PV, wind turbine, EFR, and battery bank).

Section 3 establishes the mathematical model of the hybrid renewable energy system (HRES), detailing the generation equations and storage dynamics.

Section 4 presents the genetic algorithm for optimal sizing of HRES.

Section 5 defines the objective function based on net present value (NPV), with the formulation of cash flows and constraints.

Section 6 presents the simulation.

Section 7 presents the results obtained, economic indicators, and sensitivity analysis.

Section 8 compares the previous reference project under a consistent NPV calculation methodology.

Section 9 discusses the findings, limitations, and implications for implementation; and

Section 10 concludes with conclusions and recommendations for future work.

2. Description of the Grid-Connected Hybrid Energy System

This article proposes a hybrid renewable energy generation system with the aim of providing clean and continuous electricity to the Macau City Campus while reducing dependence on fossil sources.

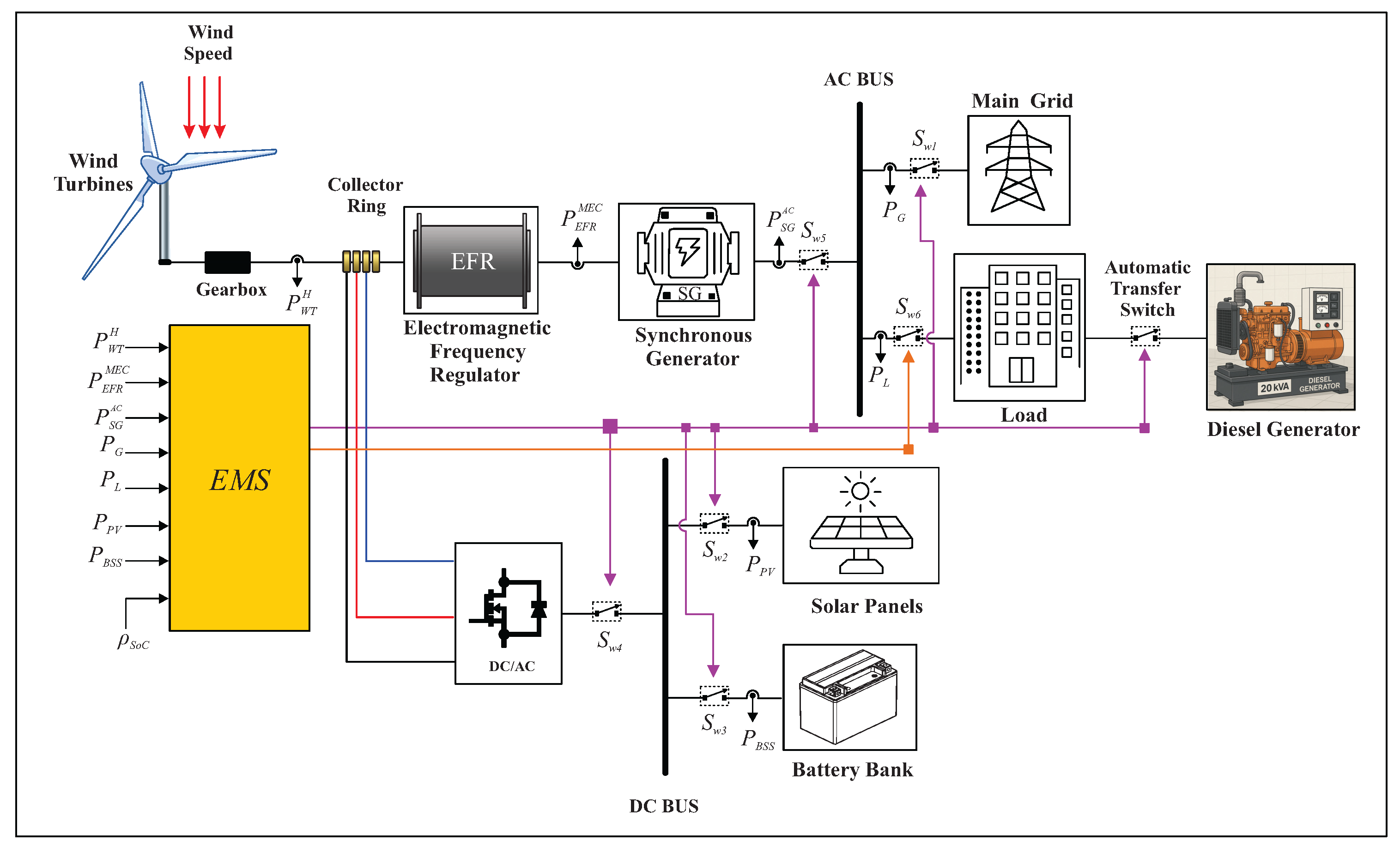

Figure 1 shows the topology of the proposed configuration, which integrates wind turbines (WT), photovoltaic panels (PV), an energy storage system (ESS), a diesel generator (DG), an electromagnetic frequency regulator (EFR), a synchronous generator (SG), the campus load and the connection point to the electricity grid. The system’s operation is coordinated by a centralized energy management system (EMS), which is responsible for real-time control of energy flows.

The wind turbine converts the wind’s kinetic energy into mechanical power (), which is transferred via a set of gears to the EFR. This electromagnetic device creates a rotating magnetic field that mechanically drives the SG, allowing the generation of alternating current () compatible with the AC bus. The energy produced can be directed to meet the campus load () or exported to the electricity grid ().

The direct current sources, consisting of the photovoltaic modules and the battery bank, are connected to the system via a DC/AC inverter. This inverter is also responsible for regulating the rotation speed of the EFR rotor, keeping it constant to ensure the stability of the generated frequency. The EMS monitors and controls critical operating variables in real-time, such as the power supplied by each source (, , ), the exchange with the grid () and the ESS state of charge (). Based on the instantaneous operating conditions, the EMS controls the switches ( to and the automatic transfer switch (ATS) in order to prioritize the use of renewable sources, store surplus energy or activate auxiliary sources, depending on demand.

In addition, the system incorporates an emergency diesel generator, used exclusively in extreme conditions. This resource is activated, for example, during simultaneous failures of wind and solar generation at night, when the battery bank does not have enough energy to keep the DC bus voltage within operating limits. Therefore, the proposed system stands out for its operational flexibility, robustness in the face of adverse scenarios, and ability to efficiently integrate multiple renewable and conventional energy sources.

3. Mathematical Model of the Hybrid Renewable Energy System (HRES)

This section presents the sizing of the components of the grid-connected HRES. The actual meteorological data, such as wind speed and solar radiation, were obtained from the NASA database. Based on this information, mathematical models were developed for the main components of the system: the campus electrical loads, the photovoltaic (PV) system, the wind turbine, the EFR, and the energy storage system (ESS). These models considered input variables including climate data (wind speed and solar radiation), the energy consumption profile of the academic unit, and equipment specifications such as nominal power, efficiency, and useful life.

3.1. Load Model

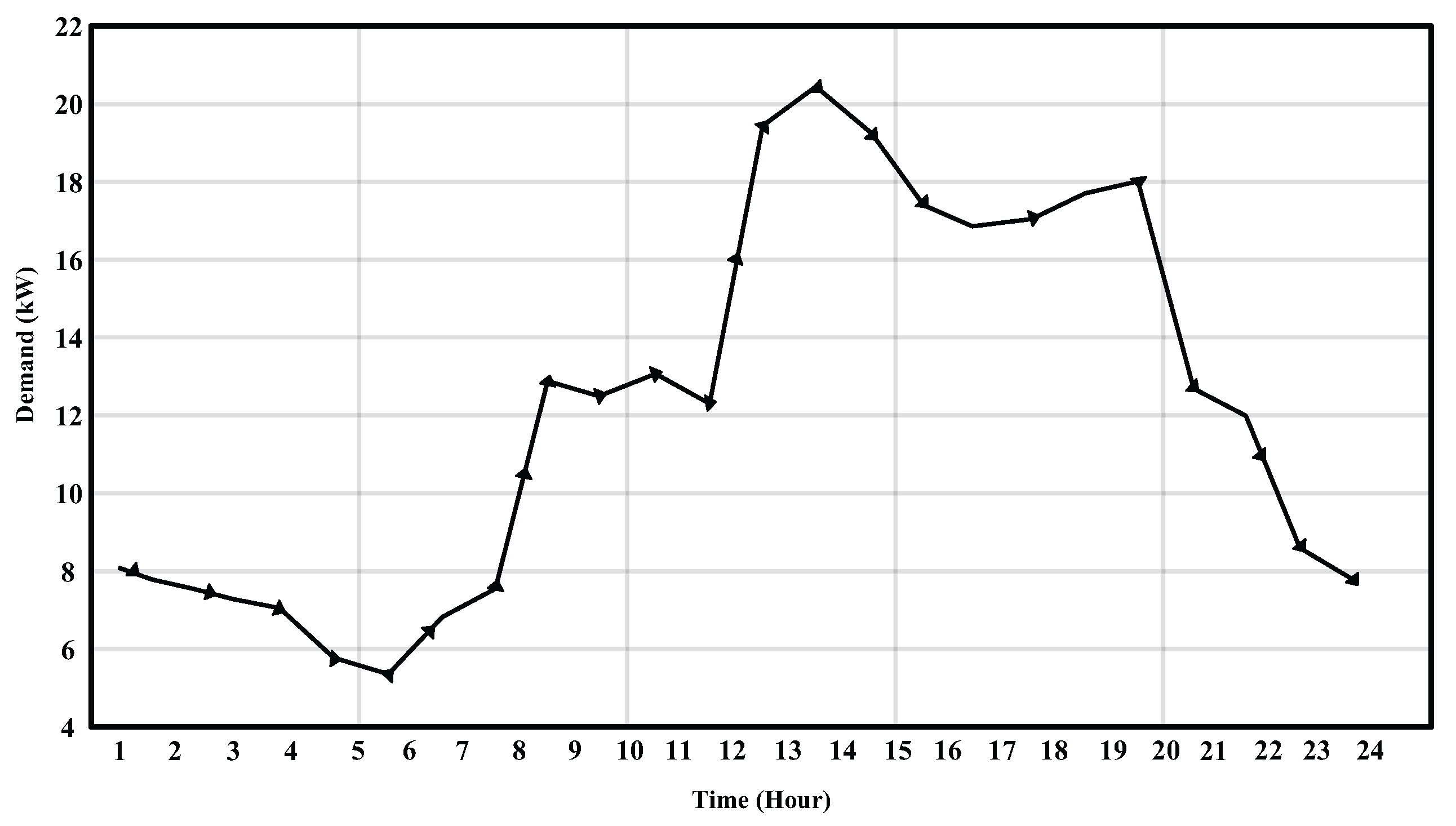

The load profile, which represents the variation in energy demand over the course of a typical day, was based on data provided by [

17] and is illustrated in

Figure 2. This figure shows the average hourly energy demand over a 24-hour period. The daily energy consumption (

) is calculated by adding up the power consumed in each time interval and multiplying by the duration of that interval (

) [

18]:

In this equation (

1),

represents constant energy consumption (e.g. lighting or fixed equipment), while

corresponds to the power consumed by the i-th controllable load (e.g. appliances that can be switched on or off). The parameter

indicates the total number of controllable loads.

3.2. Photovoltaic Model

The photovoltaic system model estimates the power generated by the solar panels, denoted as

, based on factors such as solar irradiance, ambient temperature, cell temperature, and equipment efficiency. The output power is given by the following equation [

19]:

where

is the solar irradiance at the optimum tilt angle,

is the total area of the solar panels, and

is the temperature coefficient, typically 0.5%/°C, indicating the reduction in power due to the increase in temperature [

20].

is the efficiency of the DC/DC converter that regulates the output. The module temperature

is calculated based on the ambient temperature

and the solar irradiance using Equation (

3)

here

is the ambient temperature at time

t, NOTC is the Nominal Operating Temperature of cell (supplied by the manufacturer under conditions of 800 W/m² and 20°C), and

is the reference temperature, typically 20°C.

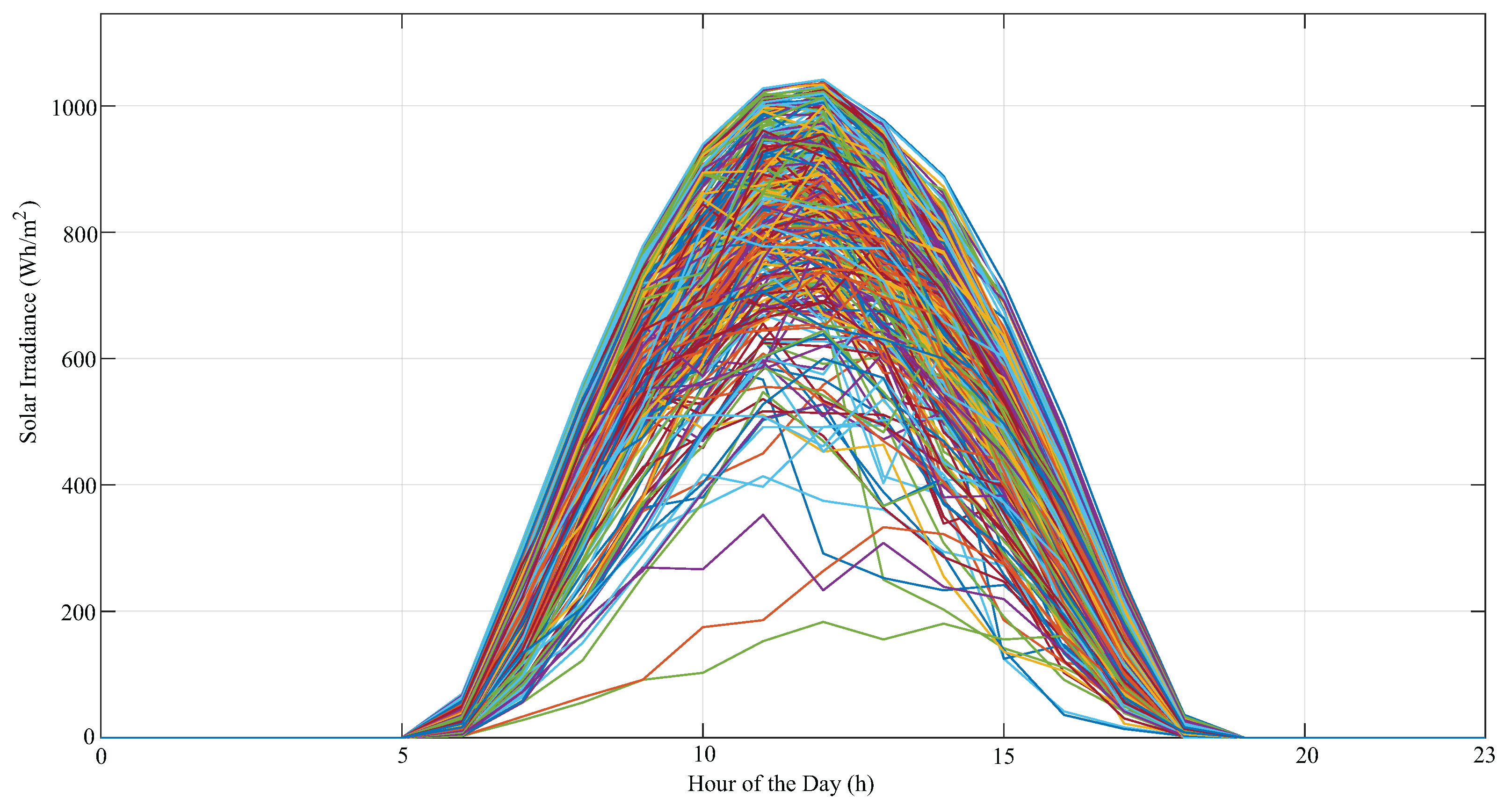

Figure 3 shows the solar radiation data in the region of Macau, RN, collected by NASA between January 1 and December 31, 2015, at latitude 05º15’ South and longitude 36º57’ West. This data illustrates the daily variation of sunlight throughout the year.

3.3. Wind Turbine Model

To calculate the power generated by the wind turbine, it is necessary to adjust the measured wind speed to the turbine’s hub height, as the measuring equipment (anemometers) are typically located at different heights. The relationship between wind speed at hub height

and anemometer height

is given by:

in this equation (

4),

is the wind speed (in meters per second) at the height of the cube

, and

is the height of the anemometer. The exponent

depends on the terrain, time, and season, but is typically around

, as proposed by Johnson (1985) [

21].

The output power of the wind turbine

depends on the wind speed

and is modeled as follows [

22]:

where

is the turbine’s nominal power,

is the instantaneous wind speed,

is the minimum speed for power generation,

is the nominal speed, and

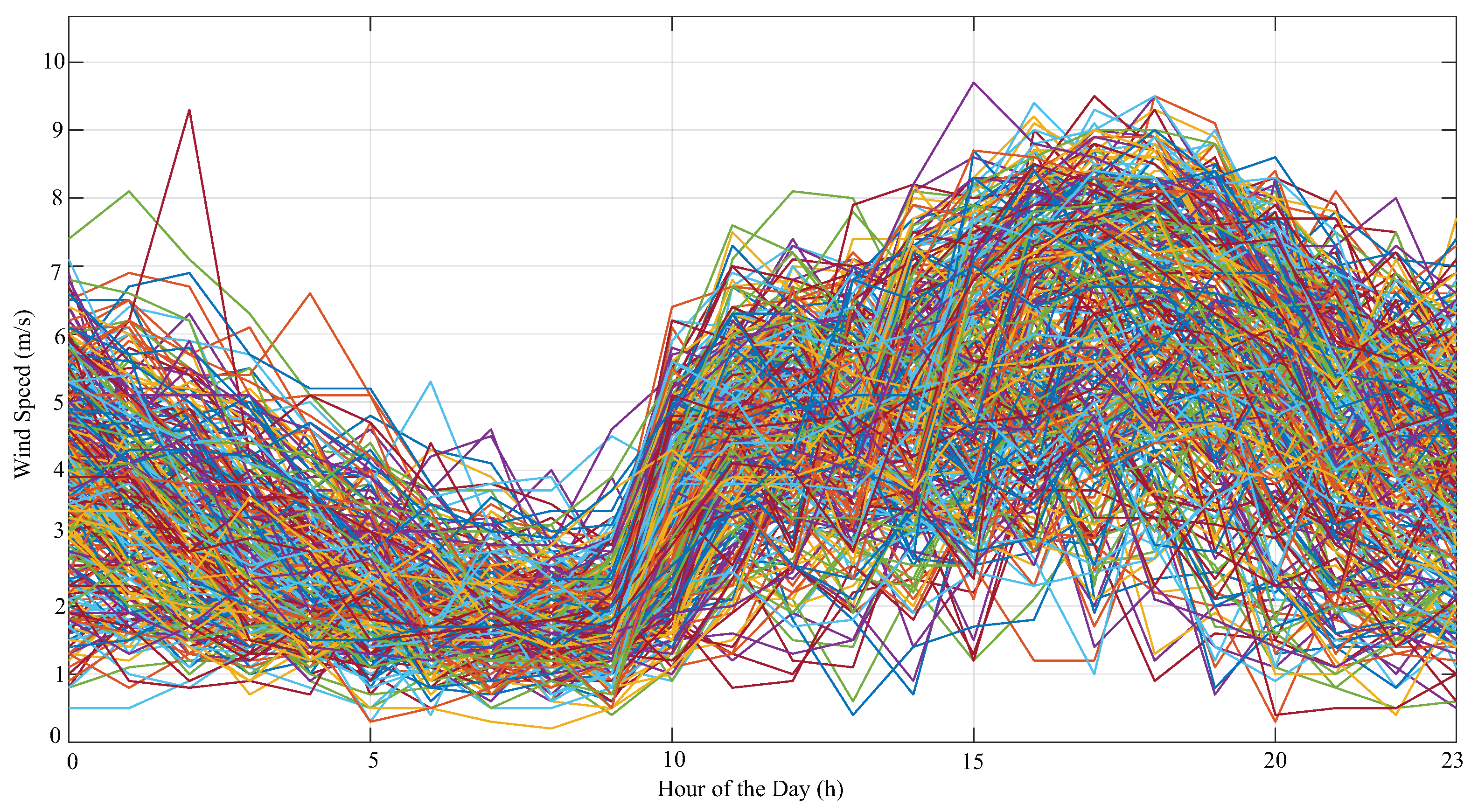

is the maximum speed, above which the turbine is shut down for protection. Here, the wind speed data was obtained from the INMET database, for the same period as the solar data, measured at a height of 17.37 meters, at hourly intervals, totaling 8760 data points.

Figure 4 shows the daily wind speed patterns in the region over the period analyzed.

3.4. Modeling of Electromagnetic Frequency Regulator (EFR)

For design purposes, the nominal power of the EFR (

) is set to be equal to the nominal power of the wind turbine, since both operate at the same angular velocity [

14]. This ensures that the EFR can handle wind speed variations while maintaining a constant output velocity.

This relationship ensures that the EFR operates at the same angular speed as the turbine, maximizing energy conversion efficiency. This technology offers several advantages compared to conventional wind systems, including (i) reduced maintenance costs, by eliminating the need for complex power converters, the REF reduces maintenance costs and increases reliability; (ii) improved power quality, by mitigating harmonics and voltage fluctuations, ensuring compliance with grid quality standards; and (iii) hybrid integration, facilitating direct hybridization with other energy sources (such as PV and ESS) through the EFR armature slip rings. Thus, the EFR works in conjunction with the wind turbine and the synchronous generator to provide AC power that can be used directly by the campus or exported to the COSERN grid in the state of Rio Grande do Norte/Brazil.

3.5. Modeling of Battery Energy Storage System

In hybrid renewable energy systems, the energy storage system (ESS) plays a critical role in mitigating the variability inherent in renewable sources, such as solar PV. Accurate modeling of the ESS is essential to ensure system reliability, meet load demand, and optimize economic costs. In this study, the ESS model is based on the daily energy balance between generation and demand, adopting the methodology proposed by Lai and McCulloch (2017) [

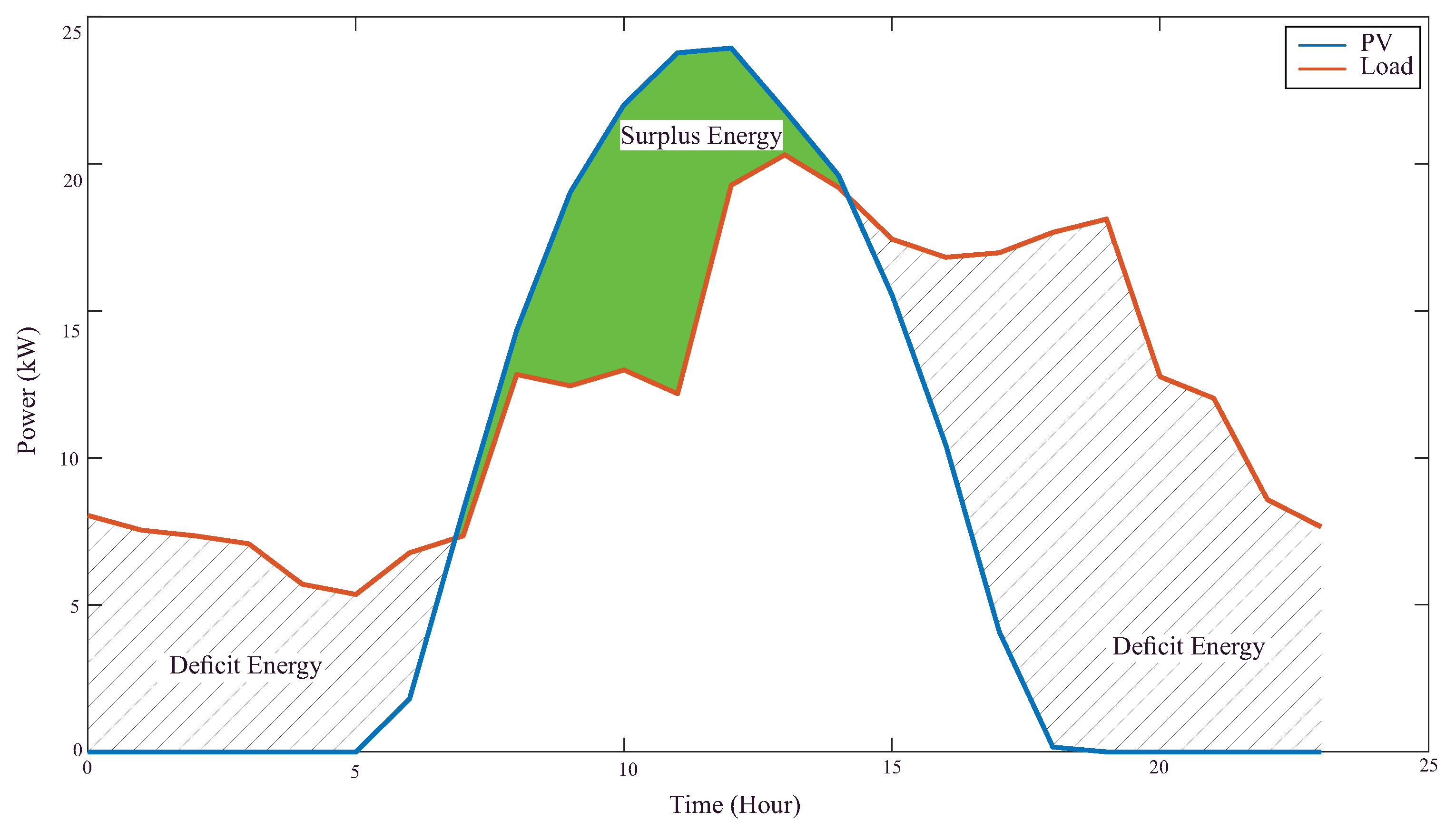

23] for hybrid systems with high solar energy utilization. Thus, the ESS sizing is based on the difference between PV generation and load demand over a 24-hour period. For the UFRN campus in Macau/RN, the daily energy surplus was estimated at 120 kWh, as illustrated in

Figure 5. This surplus ensures that the ESS can store energy during periods of high solar generation and supply it during periods of low generation or high demand, such as at night or on cloudy days.

The charge of state (SoC) of the battery at any time (

t) is modeled by the equation:

where:

: State of charge at time (t),

: Energy generated by the PV system at time (t) (kWh),

: Energy demanded by the load at time (t) (kWh),

: Inverter efficiency (typically 0.95),

and : Inverter and battery efficiencies, respectively.

This equation reflects the hourly dynamics of the SoC, considering the energy generated by the PV system that is directed to the battery, the output to meet demand (adjusted by the inverter efficiency), and the losses associated with the battery efficiency. ESS sizing is adjusted to operate within the safe depth of discharge (DoD) limits, in this case between 20% and 80% for lithium-ion batteries, in order to maximize service life.

4. Genetic Algorithm for Optimal Sizing of HRES

Genetic algorithms (GAs) are a class of stochastic optimization methods inspired by the principles of natural evolution, as originally formulated by John H. Holland (1975) [

24] and later popularized by Goldberg (1989) [

25]. Such algorithms are widely used to solve complex optimization problems, characterized by multidimensional, nonlinear, and often multimodal search spaces [

26].

One of the most common representations in GAs is binary, where each individual is encoded as a sequence of bits (0 and 1). However, alternative representations, such as real values or permutations, are also frequently used depending on the problem [

27].

The main genetic operators are:

Selection: individuals with higher fitness, determined by an objective function, have a higher probability of being selected for reproduction. Common techniques include roulette and binary tournament [

28].

Crossover: combines characteristics of two individuals (parents) to generate offspring. A classic example is the one-point crossover, in which segments of the parents are recombined [

26].

Mutation: small random perturbations are introduced into chromosomes (genes), preserving genetic diversity and preventing premature convergence [

27].

The iterative process of a GA can be summarized in the following steps [

26]:

Initialization: Random generation of an initial population.

Evaluation: Calculation of the fitness of each individual based on the objective function.

Selection: Selection of the fittest individuals for reproduction.

Application of Operators: Crossover and mutation to create a new generation.

Stopping Criterion: Verification of convergence or maximum number of generations.

GAs have been widely applied in the optimization of renewable energy systems, such as hybrid microgrids. In this context, the objective is to minimize investment and operating costs while meeting energy demand. Variables such as the number of photovoltaic panels, wind turbines, battery banks, and inverters are optimized to ensure efficiency and cost-effectiveness [

29]. The objective function usually incorporates acquisition, maintenance, and operation costs, in addition to technical constraints.

In this work, a genetic algorithm is adopted as a metaheuristic technique for the optimal dimensioning of the main components of a hybrid power generation system (HPGS), including photovoltaic (PV) modules, wind turbine (WT), battery bank (BB), and electromagnetic frequency regulator (EFR). The objective of the optimization process is to maximize the net present value (NPV), as defined in

Section 5. Metaheuristics are well-suited for scaling HRES due to their ability to navigate vast and complex search spaces without getting stuck in local optima. Among these, genetic algorithms (GAs) are the most prevalent.

Each individual (chromosome) of the AG is represented by a real vector

x of four decision variables:

where

(kWp) is the installed capacity of photovoltaic panels;

(kW) is the nominal power of the wind turbine;

(kWh) is the capacity of the battery bank;

(kW) is the nominal power of the EFR.

The initial population of size N is randomly generated within predefined lower and upper bounds for each decision variable, ensuring a broad exploration of the search space from the beginning. Thus, pairs of parents are chosen by performing binary tournaments, in which two random individuals are compared and the one with the highest fitness is selected as the parent.

For each pair of parents

,

, a descendant

y is generated. Real uniform crossover is used, where for each gene

i:

for each gene, with probability

, an adaptive Gaussian perturbation is applied:

where

decays exponentially with generation

g.

In addition, the top 5% of individuals are copied directly to the next generation, ensuring that high-performing solutions are not lost. The GA procedure follows the pseudocode in

Table 1.

5. Objective Function

The economic feasibility analysis of energy projects is commonly performed using consolidated financial indicators, such as net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), benefit-cost ratio (B/C), and payback period. In this study, NPV was adopted as the main decision criterion, due to its wide acceptance in the literature, robust methodological basis, and ease of interpretation [

30]. In addition, it was established as the objective function to be maximized, determining the ideal system configuration.

NPV represents the difference between the present value of future net revenues and the initial cost of the project, considering a discount rate

, which reflects the opportunity cost of capital or the minimum attractive rate of return (MARR). A positive NPV indicates that the project tends to generate benefits greater than costs over time, and is therefore economically viable. A negative NPV suggests financial unfeasibility, given that costs would exceed expected benefits [

31].

The calculation of NPV involves three fundamental steps: (i) projection of annual cash flows (

); (ii) definition of the minimum attractiveness rate of return

, usually between 7% and 15%, according to the investment risk and the macroeconomic scenario [

32]; and (iii) discounting the flows to the present value, subtracting the initial investment

. The general equation is expressed by:

where:

: initial cost of the project, including acquisition (

) and installation (

) [

33];

: cash flow in year t;

: minimum attractiveness tax;

n: analysis horizon, defined by the useful life of the equipment.

The optimization process developed in this study aims to maximize the NPV from the optimal selection of power generation components. Thus, the objective function of the optimization problem can be defined as:

The function

includes all annual revenues and expenses of the system, as follows:

where:

: revenue from energy generation in year t;

: cost of acquiring equipment;

: annual cost with increase in contracted demand;

: operational cost (e.g.: installation labor);

: maintenance cost.

The revenue

is obtained according to the equation:

where:

: average annual energy generated during peak hours;

: average annual energy generated outside peak hours;

, : energy rates during peak and off-peak hours in year t.

Both costs and rates are updated annually, considering inflation and variations in electricity prices.

The annual maintenance costs (

) and installation costs are calculated using Equations (

15) and (

16), respectively. The annual maintenance cost (

) is incurred regularly throughout the project’s useful life. It is composed of a fixed annual portion and a variable portion, proportional to the amount of energy generated during the period. The installation cost is estimated as 15% of the total acquisition value of the equipment [

34].

where

represents the annual fixed maintenance cost,

is the electrical energy generated annually by the system,

K is the maintenance cost coefficient per unit of energy (kWh), and

corresponds to the installation labor cost.

6. Simulation

The main parameters that define the behavior of the GA are presented below, including population configuration, genetic operator rates, and search limits. These values were selected based on consolidated references in the literature and calibrated for the HRES sizing problem. For quick reference,

Table 2 summarizes the values adopted.

The results obtained after running the GA indicate the optimal HRES configuration as: , , and . Next, the economic and operational impact of this configuration is examined through a long-term simulation.

To evaluate the technical and economic performance of the proposed hybrid system, a simulation was carried out considering a period of 20 years.

Table 3 presents the main data adopted.

The system was designed to generate an average of approximately 218 MWh per year, totaling approximately 4.36 GWh at the end of the period evaluated. This value is much higher than the load consumption, which totals just over 2.1 GWh in 20 years. The estimated annual revenue is based on a tariff of R$ 0.34 per kWh, according to the values practiced in 2015. To bring the results to more current values, an accumulated monetary correction of 67.8% was considered until 2025, following the inflation projection published in the Central Bank of Brazil’s Focus bulletin on April28, 2025.

Table 4 shows the costs of the equipment used in the simulation, as well as the estimated useful life of each component. This data is essential for calculating the necessary investments, future replacements, and maintenance of the system.

The values include all the main elements of the system, such as turbines, solar panels, batteries, inverters, and auxiliary generators, as well as materials and installation costs. Durability was taken into account to estimate future replacements. For example, the battery bank has a useful life of 5 years, requiring replacements throughout the analysis period, while the solar panels last 25 years and do not require replacement during the horizon considered.

From de optimal sizing and the information present, this serves as basis for calculating the net present value (NPV) and for comparing it with other configurations of similar systems previously studied. The analysis allows verifying the financial viability of the proposal, considering the total costs and the economic benefits generated over time.

In addition to the main technical and economic data of the hybrid system, other parameters were considered in the simulation with the aim of making the analysis more realistic and in line with the practical implementation conditions. These data are presented in

Table 5.

The dollar exchange rate considered refers to the year 2015 and was used to convert the purchase price of an industrial induction motor to the equivalent in Brazilian reais (BRL). This value served as a basis for EFR estimating cost, which is derived from an induction motor with structural modifications. An increase of 20% over the original value of the motor was adopted to represent the additional adaptation costs required to transform the conventional motor into an EFR. This modification involves, for example, allowing the stator to rotate, which requires specific mechanical changes to the housing and the assembly system.

On the other hand, the proposal to use the EFR also results in savings in other components of the system. In the case of the wind turbine, a 20% discount on the total cost was considered in relation to a conventional turbine [

17]. This is justified by the elimination of equipment such as transformers, speed multipliers, and electronic converters, which become unnecessary due to the characteristics of the EFR for small systems.

Other relevant parameters include the number of photovoltaic modules (180 units), the presence of only one wind turbine and one inverter, and an estimated maintenance cost of R$ 0.05 per kWh generated. In addition, a 15% rate on the acquisition cost of all equipment, cables, and accessories was considered for estimating labor costs for installing the system. Finally, the electricity tariff adopted for revenue calculations corresponds to the value of R$ 0.3425 per kWh, practiced in 2015, which is compatible with the historical data of the local distributor. These additional parameters were essential to improve the financial feasibility calculations and to ensure greater accuracy in obtaining the net present value (NPV) of the proposed system.

7. Results

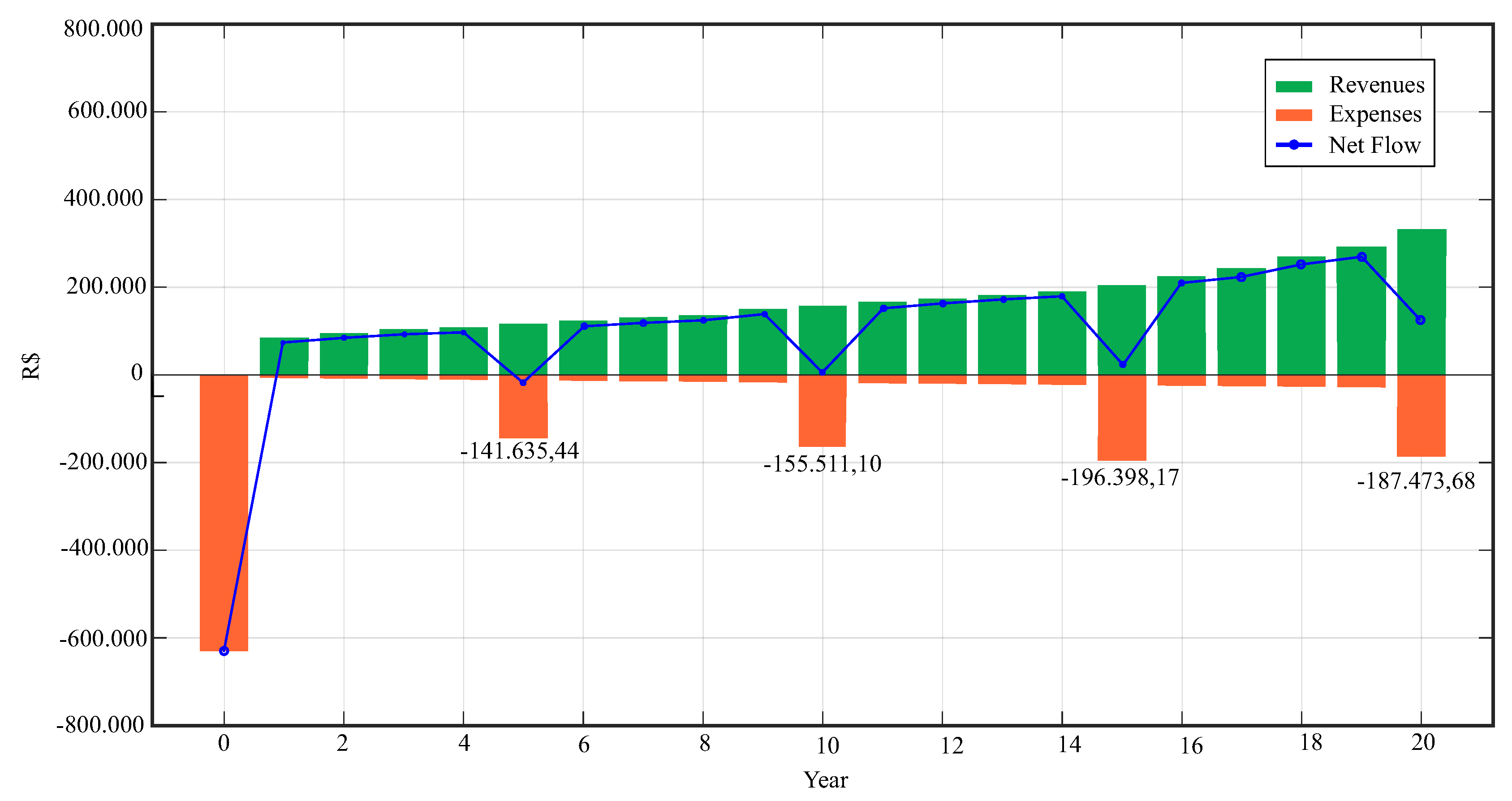

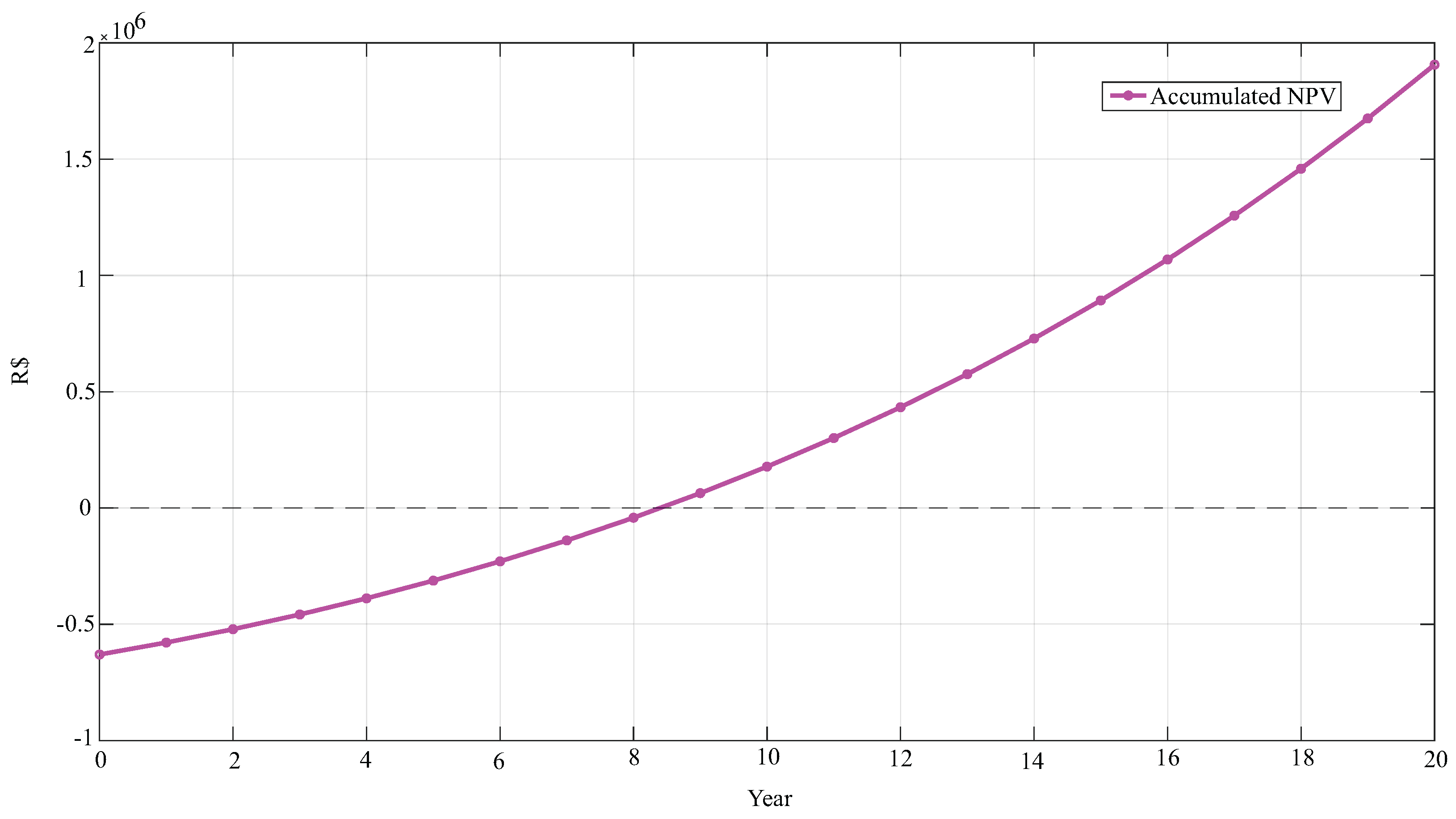

The analysis of the simulated data allowed the assessment of the economic and financial viability of the proposed hybrid system, with emphasis on the NPV calculation, which reached R

$ 1855971.99 in 2015 values, indicating a significant financial return over the 20 years of operation. The results are detailed in

Table 6, which presents, year by year, the annual maintenance costs, the energy tariff value , the updated (discounted) expenses and revenues, the annual cash flow (Total Desc.), and the accumulated cash flow (Payback).

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 complement this analysis, illustrating, respectively, the cash flow evolution and the accumulated trajectory of NPV.

The initial investment required to implement the system was R$ 631255.80, reflecting installation and infrastructure costs. From the first year onwards, revenues from energy generation showed continuous growth, reaching R$ 972125.08 in year 20, driven by the appreciation of the energy tariff. At the same time, maintenance expenses increased over time, starting at R$ 18250.86 in year 1 and reaching R$ 85066.45 in year 20, incorporating inflation adjustments and projected operating costs. Discounted Exp. and Discounted Rev.., adjusted by a minimum attractiveness rate, reveal that the annual discounted cash flow (Net Discounted Value) becomes positive from the sixth year onwards, indicating that, at this point, revenues exceed adjusted operating expenses. However, the full return on the initial investment, as indicated by the Payback indicator, only occurs in the ninth year, when the accumulated cash flow becomes positive, totaling R$ 117268.50.

Figure 6 highlights the dynamics between revenues (green), expenses (orange), and net flow (blue) over 20 years. It can be observed that expenses presented notable peaks, such as in year 0 (-R

$ 631255.80), year 5 (-R

$ 141635.44), year 10 (-R

$ 155511.10), year 15 (-R

$ 196398.17) and year 20 (-R

$ 187473.68), reflecting initial investments and high operating costs at specific moments. Revenues, in turn, grew consistently, reaching around R

$ 304000 in year 20, while net flow fluctuated but showed a recovery trend from the tenth year onwards, suggesting financial stabilization.

Figure 7 complements this analysis by illustrating the accumulated NPV, which starts negative, crosses the break-even point around the eighth year, and reaches R

$ 1855971.99 in year 20, demonstrating exponential growth and the economic viability of the project in the long term.

These findings corroborate the attractiveness of the proposed hybrid system. Despite the high initial costs and growing operating expenses, the balance between income and expenses, combined with the significant cumulative return, shows that the project achieves financial sustainability from the ninth year onwards, with a robust performance at the end of the analyzed horizon.

In

Figure 7, there is an exponential growth in accumulated NPV from year 0, where it starts out negative, crossing the zero line around year 8 and reaching around 2 million in year 20. This indicates that the investment becomes profitable in the long term, with a significant return after the break-even point.

8. Comparison with Previous Project

To put the results in context, a comparison was made with a previous project, carried out in 2015 under the same conditions. The comparative data is summarized in

Table 7 and

Table 8, allowing a detailed analysis of the economic and technical performance of the proposed hybrid system of the reference project.

Table 7 shows the NPV values for both projects, in 2015 values and updated to 2025. The current project achieved an NPV of R

$ 1855971.99 in 2015, which, adjusted for inflation, is equivalent to R

$ 3114320.99 in 2025. In contrast, the Delson et al. [

17] project recorded an NPV of R

$ 1685529.00 in 2015, corresponding to R

$ 2828317.66 in 2025. These results indicate that the proposed sizing technique has a superior economic performance, both in nominal terms and adjusted for inflation, showing significant improvements in the technical, operational, and financial parameters adopted in the current project.

Table 8 details the main technical and financial parameters of the two projects, allowing for a more in-depth analysis of the differences between them. The proposed system generated 2006460.54 kWh of wind energy over 20 years, slightly more than the project in Delson et al. [

17], which produced 1922800 kWh. On the other hand, photovoltaic (PV) energy generation in the current project was 2353115.41 kWh, significantly lower than the 5122453 kWh of the 2015 project, which reflects a lower dependence on photovoltaic modules in the proposed hybrid system. This is corroborated by the number of PV modules used: 143 (245 Wp) in the current project, compared to 504 (245 Wp) in the project of Delson et al. Similarly, the battery bank in the proposed system consists of 91 units (12 V, 220 Ah), a reduction from the 150 units in the previous project, indicating optimization in the sizing of energy storage.

Despite the lower photovoltaic generation, the load demand met remained identical in both projects, totaling 2105590.68 kWh over 20 years, which suggests that the proposed system achieved greater efficiency in integrating wind and photovoltaic sources to meet the same energy needs. In addition, the higher NPV of the current project (R$ 1855971.99 in 2015 and R$ 3114320.99 in 2025) compared to the Delson Project (R$ 1685529.00 in 2015 and R$ 2828317.66 in 2025) reflects better economic performance.

In summary, the comparative analysis shows that the proposed hybrid system has economic and technical advantages over the Delson Project, with greater efficiency in energy generation and storage, as well as a more significant financial return. These results reinforce the strategies adopted, consolidating the viability of the current project in the context of hybrid energy generation systems.

9. Discussions

The results obtained indicate that the adoption of HRES at UFRN/Macau/RN/Brazil is technically feasible and economically attractive. The optimal sizing maximizing of the NPV enables the identification of the optimum configuration, promoting a balance between initial investment, operating costs, and economic benefits throughout the project’s life cycle. The use of the approach, commbined with the integration of the EFR proved particularly beneficial as it allowed dynamic control of the wind turbine rotor speed, improving the system’s response to variations in load and wind resources.

The proposal proved to be robust in the face of uncertain scenarios, such as tariff variations and component degradation. The analysis showed that the combined use of solar panels and wind turbines, complemented by battery storage and, in the extreme case the use of diesel generators, guarantees energy reliability even during periods of low renewable generation.

Comparatively, the system developed outperforms traditional microgeneration approaches based solely on photovoltaic panels, as it has greater autonomy, lower risk of power failure (lower LPSP), and more attractive financial returns. The proposed methodology can be applied in other public administration units, promoting budget savings and environmental sustainability.

10. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the application of a Genetic Algorithm, reinforced by elitism and adaptive Gaussian mutation, associated with detailed modeling of each component of the hybrid system, results in significant technical and economic gains. The practical implementation at the UFRN/Macau/RN/Brazil campus indicated an optimal configuration that generates significant energy surpluses, reaching an NPV of R$ 1.86 M (2015) and, discounted payback in approximately 9 years. The ERF incorporation proved to be particularly advantageous, as it (i) increases wind conversion efficiency, mitigating harmonics and voltage fluctuations; (ii) reduces maintenance costs, by dispensing with complex frequency converters; and (iii) improves PV–WT–ESS synergy, optimizes power flow management and extends battery life. The sensitivity analysis demonstrated the robustness of the method against variations in tariffs, inflation, and climate scenarios, reinforcing its applicability in similar contexts. The comparison with the 2015 project showed an increase of 10–17% in NPV, attesting to the advantage of integrated modeling and customized GA. The proposed approach constitutes a high-impact tool for planning hybrid systems in remote or grid-connected areas, contributing to the sustainable energy transition. Future work should explore multi-objective extensions, for example, minimizing CO2 emissions simultaneously with NPV, and incorporating machine learning-based climate forecasts to further improve the robustness of the solutions.

Author Contributions

A. O. B. and A.O.S. conceived and designed the study; A. O. B., J. d. C. P. and R. F. P. contributed to data curation, investigation, and methodology; E.R.L.V., E. P. d. R. and A.O.S. reviewed the manuscript and provided valuable suggestions; A. O.B., J. d. C. P., E. P. d. R., R. F. P. and E.R.L.V. wrote the paper; and A.O.S. supervised. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001 and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq).

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) and CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa) for the financial support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HRES |

Hybrid Renewable Energy Generation System |

| WT |

wind turbine |

| BB |

battery bank |

| ANN |

artificial neural network |

| ATS |

automatic transfer switch |

| AI |

artificial intelligence |

| COE |

cost of energy generated |

| SoC |

charge of state |

| DoD |

depth of discharge |

| UL |

unserved load |

| INMET |

Instituto Nacional de Metereologia |

| NOTC |

Nominal Operating Temperature of cell |

| EPSO |

enhanced particle swarm algorithm |

| LCC |

life cycle cost |

| LCOE |

levelized cost of energy |

| LPSP |

probability of load shedding |

| EFR |

Electromagnetic Frequency Regulator |

| NPV |

Net Present Value |

| GA |

Genetic Algorithm |

| PSO |

Particle Swarm Optimization |

| PV |

photovoltaic panels |

| EMS |

Energy Management System |

| HPGS |

hybrid power generation system |

| COSERN |

Companhia Energética do Rio Grande do Norte |

| MAT |

minimum attractiveness tax |

| IRR |

Internal Rate of Return |

| MARR |

minimum attractive rate return |

| ESS |

energy storage system |

| MILP |

Mixed Integer Linear Programming |

References

- do Nascimento, T. F., Nunes, E. A. D. F., Villarreal, E. R. L., Pinheiro, R. F., & Salazar, A. O. Performance Analysis of an Electromagnetic Frequency Regulator under Parametric Variations for Wind System Applications. Energies 2022, 15(8), 2873. [CrossRef]

- Agha Kassab, F., Rodriguez, R., Celik, B., Locment, F., & Sechilariu, M. A Comprehensive Review of Sizing and Energy Management Strategies for Optimal Planning of Microgrids with PV and Other Renewable Integration. Applied Sciences 2024, 14(22), 10479. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M. S., Moghavvemi, M., & Mahlia, T. M. I. Genetic algorithm based optimization on modeling and design of hybrid renewable energy systems. Energy Conversion and Management 2014, 85, 120-130. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Wei, Z., & Chengzhi, L. Optimal design and techno-economic analysis of a hybrid solar-wind power generation system. Applied energy 2009, 86(2), 163-169. [CrossRef]

- Dufo-Lopez, R., & Bernal-Agustín, J. L. Multi-objective design of PV-wind-diesel-hydrogen-battery systems. Renewable energy 2008, 33(12), 2559-2572. [CrossRef]

- Paulitschke, M., Bocklisch, T., & Böttiger, M. Comparison of particle swarm and genetic algorithm based design algorithms for PV-hybrid systems with battery and hydrogen storage path. Energy Procedia 2017, 135, 452-463. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Maleki, A., Rosen, M. A., & Liu, J. Sizing a stand-alone solar-wind-hydrogen energy system using weather forecasting and a hybrid search optimization algorithm. Energy conversion and management 2019, 180, 609-621. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Maleki, A., Rosen, M. A., & Liu, J. Optimization with a simulated annealing algorithm of a hybrid system for renewable energy including battery and hydrogen storage. Energy 2018, 163, 191-207. [CrossRef]

- Halabi, L. M., Mekhilef, S., Olatomiwa, L., & Hazelton, J. Performance analysis of hybrid PV/diesel/battery system using HOMER: A case study Sabah, Malaysia. Energy conversion and management 2017, 144, 322-339. [CrossRef]

- Sen, R., & Bhattacharyya, S. C. Off-grid electricity generation with renewable energy technologies in India: An application of HOMER. Renewable energy 2014, 62, 388-398. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y., Zhang, X., Myhren, J. A., Han, M., Chen, X., & Yuan, Y. Techno-economic analysis of a solar photovoltaic/thermal (PV/T) concentrator for building application in Sweden using Monte Carlo method. Energy Conversion and Management 2018, 165, 8-24. Chen, M.; Zhou, D.; Wu, C.; Blaabjerg, F. Characteristics of Parallel Inverters Applying Virtual Synchronous Generator Control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 4690–4701. [CrossRef]

- Bissiriou, A. O.; Ribeiro, R. D. A.; de Rocha O. A. T. Contributions to energy management of single-phase AC microgrids used in isolated communities. 27th International Conference on Electricity Distribution (CIRED 2023) Vol. 2023, 14(22), 3811–3815. [CrossRef]

- Crisóstomo, D. C. ; do Nascimento, T. F. ; Nunes, E. A. F. , Villarreal, E. R. L., Pinheiro, R. F. ; Salazar, A. O. Fuzzy control strategy applied to an electromagnetic frequency regulator in wind generation systems. Energies, 2022, 15(19), 7011. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A. E. S.; Bissiriou, A. O.; de Oliveira, G. P.; Silva, J. V. S.; Pinheiro, R. F.; Salazar, A. O. Analysis of the Behavior of the Electromagnetic Frequency Regulator (EFR) Used in Hybrid Wind-Solar Photovoltaic Generation Systems. RE&PQJ 2024, 2(2), 21–26. [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.; Affonso, L.; Paiva A.; Raffin, F. ; Ferreira, P. Paula (Orgs.). Inovação e Negócios em Energias Renováveis. Natal, RN: PAX/RN 2021, 1–45.

- Silva, P. V.; Pinheiro, R. F.; Salazar, A. O.; do Santos Junior, L. P.; de Azevedo, C. C. A proposal for a new wind turbine topology using an electromagnetic frequency regulator. IEEE Latin America Transactions 2015, 13(4), 989–997. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, D. A.; Pinheiro, R. F.; de Medeiros Júnior, M. F. Sistema Híbrido de Geração de Energia Elétrica Conectado à Rede, incluindo o Regulador Eletromagnético de Frequência–REF. In Anais Congresso Brasileiro De Energia Solar - CBENS, , Brazil, 2016, pp.1–8.

- Dufo-López, R.; Cristóbal-Monreal, I.R.; Yusta, J.M. Optimisation of PV-wind-diesel-battery stand-alone systems to minimise cost and maximise human development index and job creation. Renewable Energy 2016, 94, 280–293. [CrossRef]

- Atia, R.; Yamada, N. Sizing and analysis of renewable energy and battery systems in residential microgrids. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2016, 7(3), 1204–1213. [CrossRef]

- Eltamaly, A. M. ; Alotaibi, M. A. Novel Fuzzy-Swarm Optimization for Sizing of Hybrid Energy Systems Applying Smart Grid Concepts. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 93629–93650. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.L. Wind energy systems. Prentice Hall, USA, 1985.

- ÇetınbaŞ, B. I.; Tamyürek, B.; Dermitas, M. The Hybrid Harris Hawks Optimizer-Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm: A New Hybrid Algorithm for Sizing Optimization and Design of Microgrids. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 19254–19283.

- Lai, C. S. ; McCulloch, M. D. Sizing of Stand-Alone Solar PV and Storage System With Anaerobic Digestion Biogas Power Plants. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2017, 64(3), 2112–2121. [CrossRef]

- Hayes-Roth, F. Review of Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems by John H. Holland. the U. Of Michigan Press, 1975. Acm Sigart Bulletin, N. 53, 15–15, 1975.

- Goldberg, D. E. Genetic Algorithm in Search, Optimization and Machine Learning. Addison, Wesley Publishing Company Reading MA 1989 1(98), 1–9.

- Eiben, A. E.; Smith, J. E. Introduction to evolutionary computing, Springer, 2015.

- Whitley, D.; Sutton, A. M. Genetic algorithms—A survey of models and methods. Handbook of natural computing, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 637–671, 2012.

- Mitchell, M. An introduction to genetic algorithms, MIT press, 1998.

- Memon, S. A.; Patel, R. N. An overview of optimization techniques used for sizing of hybrid renewable energy systems. Renewable Energy Focus 2021, 39, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Arshad, A. Net present value is better than internal rate of return. Interdisciplinary journal of contemporary research in business 2012, 4(8), 211–219.

- Kumar, B. V. ; Farhan, M. A. Optimal simultaneous allocation of electric vehicle charging stations and capacitors in radial distribution network considering reliability. Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy 2024, 12(5), 1584–1595.

- Padmini, V.; Omran, S.; Chatterjee, K. ; Khaparde, S. A. Cost benefit analysis of smart grid: A case study from India. 2017 North American Power Symposium (NAPS), Morgantown, WV, USA 2017, 1–6,.

- Maleki, A.; Ameri, M. ; Keynia, F. Scrutiny of multifarious particle swarm optimization for finding the optimal size of a PV/wind/battery hybrid system. Renewable Energy 2015, 80,552–563. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J. D. C. Computer program for dimensioning electrical energy generation systems from biogas, with application in the Baldo/CAERN treatment plant. MPEE - Mestrado Profissional em Energia Elétrica UFRN 2018, 1, 1–107. (In portuguese).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).