1. Introduction

Extensive posterior tooth restorations have always been a challenge for dentists. The decision of which type of restoration will be used is often a matter of experience, clinical judgement and skills, knowing that the preparation of a partial restoration is more technically demanding compared to a full coverage restoration. Partial coverage restorations (onlays, overlays, vonlays) are more conservative restorations compared to crowns. They do not rely on retention form, but completely on adhesion. Therefore, they offer the advantage of hard dental tissues preservation. Continuous improvements in dental materials over the past years along with increased esthetic patients demands, have led to the use of esthetic materials for the restoration of the posterior teeth, mainly composite resins and ceramics.

Composite resins have been used in dentistry for over 50 years. Their use for extensive indirect restorations has been proposed to overcome problems arising from the direct technique, such as polymerization shrinkage stress and difficulty in achieving proper contact points and occlusal anatomy [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Nowadays, monolithic composite resin blocks are also used for the fabrication of indirect restorations using CAD/CAM technology, owing to several advantages, including stable quality of the materials, lower costs, and time-saving factors [

5]. Moreover, the evolution of manufacturing techniques increased both mechanical and optical properties of ceramic materials, resulting in their extensive use for posterior partial coverage restorations [

6]. Glass ceramic materials have been successfully used for indirect posterior restorations for many years. Nowadays, lithium disilicate is probably the most used ceramic for posterior partial coverage restorations.

Several studies have evaluated the longevity of indirect posterior partial coverage restorations, fabricated from either ceramic or composite materials.

The longevity of indirect composite restorations was assessed in a prospective clinical study [

7], and the success rate of indirect composite restorations was approximately 90% after ten years of observation, while in another, single-arm prospective clinical study [

8] the success rate was 87.5% after three years of observation. In a retrospective clinical study [

9], the restoration-related survival rate was 91.1%, whilst the patient-related survival rate was 90 % after five years of evaluation. In another retrospective clinical study [

10], evaluating the long-term clinical survival and performance of direct and indirect resin composite restorations replacing cusps in vital upper premolars, survival rates were 63.6% for direct restorations and 54.5% for indirect restorations, after a mean follow-up time for evaluated restorations of 18.4 years for the direct technique and of 17.7 years for the indirect technique. Also, in a long-term retrospective study [

11] of indirect composite posterior restorations placed on molars and premolars, the survival rates were 81% at 10 years and 57% (44% - 75%) after 20 years of observation. According to available literature for indirect composite restorations, more frequent complications include secondary caries, fracture of the restorations (chipping or total debonding) and the presence of post-operative sensitivity, while in many cases deterioration of marginal integrity and marginal discoloration is observed.

Several clinical studies confirm also the successful use of ceramics as dental restorative materials. In a prospective clinical evaluation [

12], the success rate was 98.6% after five years of observation, while in another prospective clinical study [

13] the survival rate of IPS Empress ceramic inlays and onlays was 86% after four years of observation. Furthermore, in a 15-year prospective clinical trial [

14] aiming to investigate the long-term durability of extensive dentin–enamel-bonded posterior ceramic coverages, the survival rate was 75,9%. In a four-year retrospective clinical study [

15], evaluating IPS Empress restorations placed in molars and premolars, the success rate was 92.7%. Also, in another retrospective study [

16], the survival rate of restorations at the restoration level was 92.3% after 10 years and 83.8% after 14 years, while the survival rate of restorations at the patient level was 77.4% after 10 years and 65.4% after 14 years. Moreover, in a retrospective clinical study of IPS e.max Press and IPS e.max CAD restorations [

17], the survival rate was 96.3% after 2 years and 91.5% after 4 years of observation. Lastly, in a retrospective clinical study [

18] evaluating the long-term performance of ceramic in/onlays versus cast gold partial crowns, the success rates were 92.1% for ceramic restorations and 84.2% for gold restorations after a mean service time of 14.5 years. For ceramic restorations, more frequent complications include ceramic and tooth fractures, secondary caries, endodontic complications, increased surface roughness, loss of proximal contact point and deterioration of color match, marginal adaptation and marginal discoloration.

Even though the aforementioned studies evaluate both materials separately, literature also investigates the comparison between composite and ceramic partial coverage posterior restorations.

In a short-term (2 years) randomized controlled clinical trial with a split-mouth design [

19], comparing lithium disilicate and hybrid resin nano-ceramic CAD/CAM onlay restorations, the survival rate was 90% for both materials after a 2-year clinical follow- up. In a prospective clinical study [

20] evaluating lithium disilicate and composite resin partial indirect restorations with deep margin elevation, an overall survival rate of 95.9% was observed after 10 years, without any significant difference between composites and ceramics. Complications included secondary caries, pulpal necrosis, severe periodontal breakdown and fracture. Older restorations had more margin discoloration, secondary caries, more fractures of the indirect restoration and fracture of the tooth itself. Indirect composite restorations showed more degradation compared to ceramic restorations with more fractures of the restoration, more fractures of the teeth and more wear of the indirect restorations. More wear of the antagonist was observed when they were opposed to ceramic restorations compared to indirect composite restorations. In a retrospective study [

21] assessing the longevity of lithium disilicate ceramic vs. laboratory-processed resin-based composite inlays/onlays/overlays, the survival of ceramic and composite restorations was 96.8% and 84.9%, respectively after a mean observation period of 7.8 ± 3.3 years. Survival was above 98% for both restorations in the first 6 years, however, it dropped to 60% for composite by the end of the 15th year. Meanwhile the probability of survival remained high (> 95%) in the long term for lithium disilicate restorations. The reasons for failure for both materials included secondary carries, restoration fracture, and endodontic complications. In addition, lithium disilicate restorations also failed due to tooth fracture, while composite restorations failed due to marginal gap formation and loss of retention. Among the evaluated risk factors, material of restoration, oral hygiene, and bruxism showed a significant impact on the evaluated criteria.

One of the first systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the topic [

22], concluded that there is very limited evidence that ceramics perform better than composite material for inlays in the short term (3 years).

In another systematic review and meta-analysis [

23], the survival rate of the total pooled sample including feldspathic porcelain and glass-ceramics for the 5-y follow-up was 95% and 91% for the 10-y follow-up. For feldspathic porcelain, the survival rates were 92% for 5-y follow-up and 91% for 10-y follow-up. For glass-ceramics, the survival rates were 96% for 5-y follow-up and 93% for 10-y clinical follow-up. A meta-analysis of composite resin was not possible because no studies of overlays, onlays, and inlays from this material were included during the data collection phase. Fractures were the most common kind of failure.

Finally, in another systematic review and meta-analysis [

24], medium-quality data indicate that lithium disilicate and indirect composite materials demonstrate comparable survival rates in short-term follow-up. Moreover, on short- to medium-term follow-up, neither leucite restorations nor indirect composite restorations demonstrated significant superiority, while statistical analysis of the survival of lithium disilicate versus leucite restorations was not feasible.

Existing literature demonstrates that despite several clinical trials investigating the longevity of ceramic and composite resin onlays, the topic requires further investigation. Therefore, the purpose of this clinical study is to examine and compare the survival of indirect onlays/overlays made of lithium disilicate and composite resin, and to investigate the type of failures that may occur. The first null-hypothesis is that there is no difference in long-term survival of ceramic and resin composite indirect restorations. The second null- hypothesis is that the examined risk factors (material, restoration type, tooth, endodontic treatment, smoking) do not affect the survival of indirect restorations.

2. Materials and Methods

This retrospective non-interventional clinical study was carried out according to research guidelines involving human subjects, at the postgraduate clinic of the Department of Restorative Dentistry (Dental School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens). The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Dental School of National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NO 629/23.02.2024).

2.1. Patients’ selection

One hundred eighty-five indirect partial coverage posterior restorations were placed in seventy-six adult patients at the Postgraduate Clinic of the Department of Restorative Dentistry (Dental School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens). All restorations had been delivered by postgraduate students of the Restorative Dentistry program, supervised by a faculty member. Each patient had at least one onlay or overlay fabricated from either composite resin or lithium disilicate. The evaluated restorations were placed between January of 2014 and December of 2020, ensuring a minimum of 4 and a maximum of 10 years observation period.

All patients were contacted by telephone and were invited for a follow-up examination. Follow-up appointments were scheduled from January to June 2024. Before starting the clinical evaluation, patients gave their written informed consent to participate in the study. Moreover, prior to the evaluation appointment, data of the restored teeth were collected. The information collected includes the selected restorative material, the application, or not of immediate dentin sealing, the type of adhesive and cement used, and the date of delivery of the restorations.

Exclusion criteria for participation in the study are listed below:

For the evaluation of the restorations, a mirror and a new sharp metal explorer were used. X-rays were not included in the applied methodology, except in cases where there were ethical issues (evaluation of clinically diagnosed caries lesions that require intervention).

2.2. Evaluation of restorations

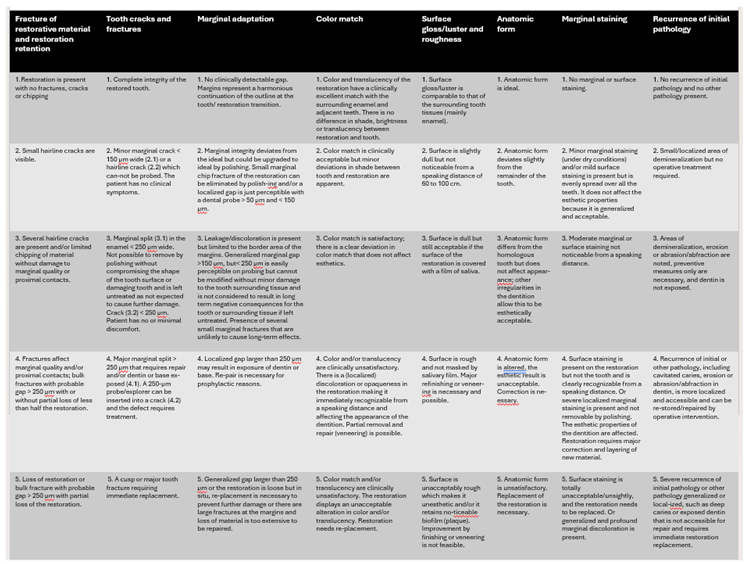

Assessment of the restorations was performed by two examiners following FDI World Dental Federation Clinical Criteria [

25] for the Evaluation of Direct and Indirect Restorations were initially trained for agreement on the criteria used, with an agreement level higher than 90%. In case of disagreement during data collection, it was resolved by consensus. The selected criteria for evaluation were color match, surface gloss/luster and roughness, anatomic form, fracture of restorative material and restoration retention, tooth cracks and fractures, marginal adaptation, marginal staining, and recurrence of initial pathology. The overall rating for a particular restoration is determined after completion of the assessments of the final scores for each of the selected clinical criteria described. Each criterion was graded by each examiner on a 1-5 scale. Failures were considered whenever a restoration receives a score of 4 or 5 at the following criteria: fracture of restorative material and restoration retention, tooth cracks and fractures, and recurrence of initial pathology. Selected criteria are further explained in

Table 1.

Recorded tooth-related risk factors included tooth type (premoral vs moral) and vitality (vital vs. endodontically treated teeth), while examined restoration-related factors were material of restoration (ceramic vs composite), extension of restoration (inlay vs. onlay/overlay), and age of filling (4-10 years). Patient-related risk factor included smoking.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The Kaplan- Meier methodology was used to calculate the success rate for each material used for indirect restorations in relation to observation time. Also, Kaplan- Meier algorithm was used to calculate the survival probabilities for each two types of restoration (onlays- overlays), molars and premolars, vital and endodontically treated teeth and smokers and non-smokers. Cox regression analysis was used to examine the possible linkage of the indirect partial restorations with restoration material, restoration type, presence of previous endodontic treatment and smoking. Statistical analyses were performed with statistical software program STATA (Version 12.1; Texas, USA).

3. Results

A total of 112 indirect partial coverage restorations placed in 51 patients were evaluated. This accounts for a patients response rate of 67.1%. Observation time ranged from 31 months to 132 months (mean observation time was 69 months). Details on the type of indirect restoration, the tooth, the material, the pulp vitality as well as the smoking habits of the patients are presented in

Table 2. The descriptive statistics illustrating the distribution of the evaluated criteria for the restorations included are listed in

Table 3. Failure was considered whenever a restoration received a score of 4 or 5 at the following criteria: fracture of restorative material and restoration retention, tooth cracks and fractures, and recurrence of initial pathology. A total of 33 restorations were considered as failures. Details on the failed restorations are presented in

Table 4.

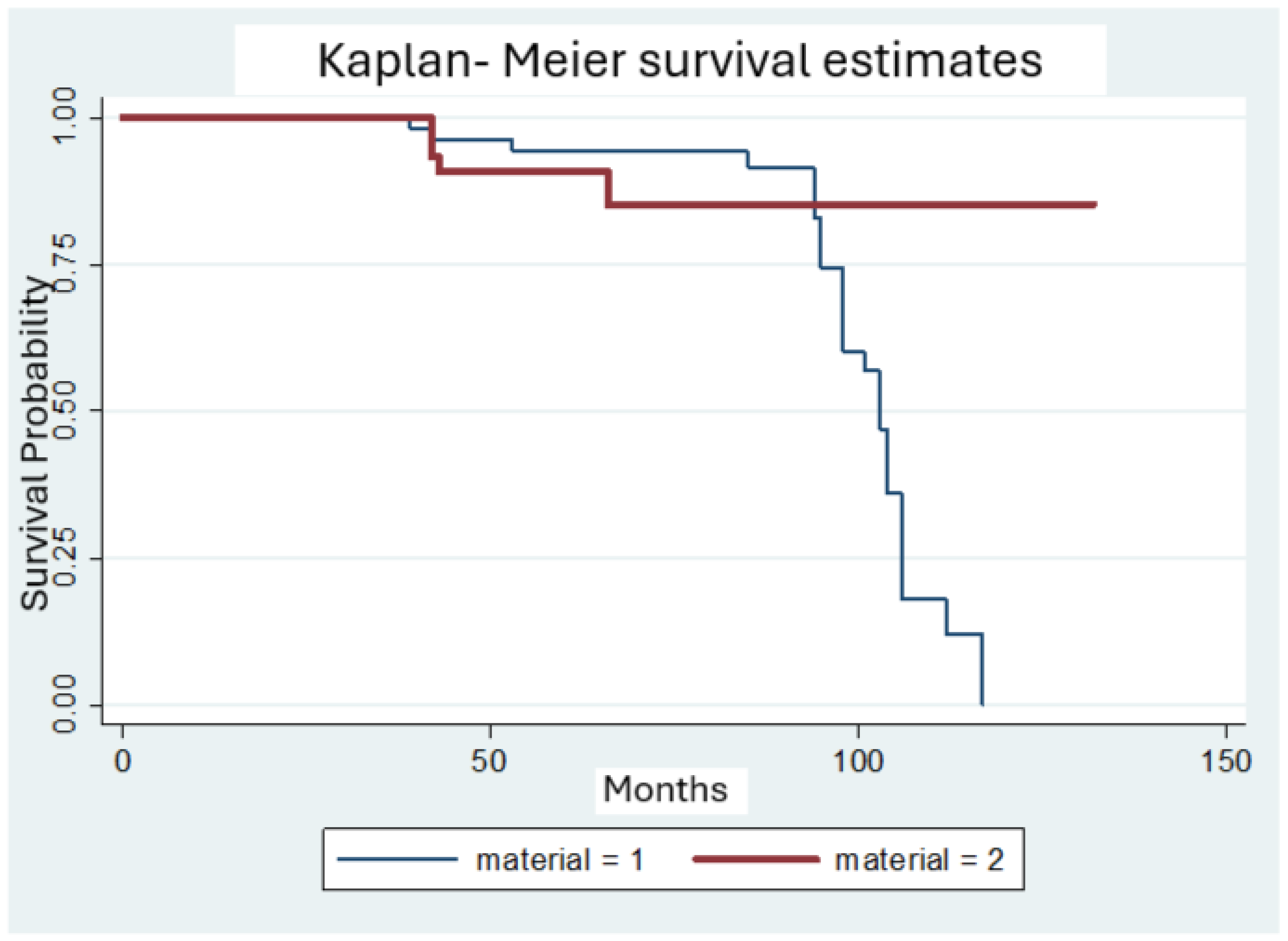

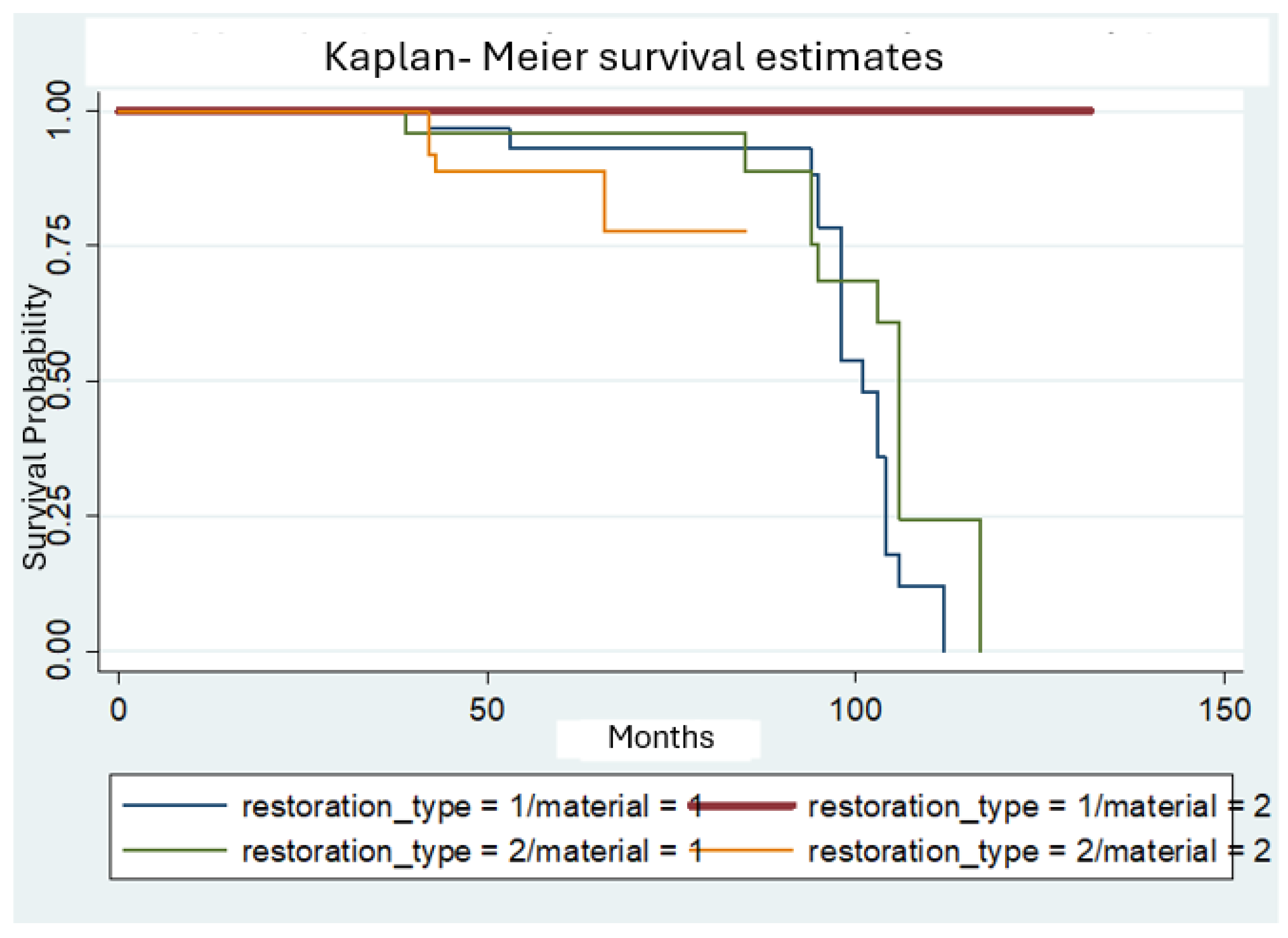

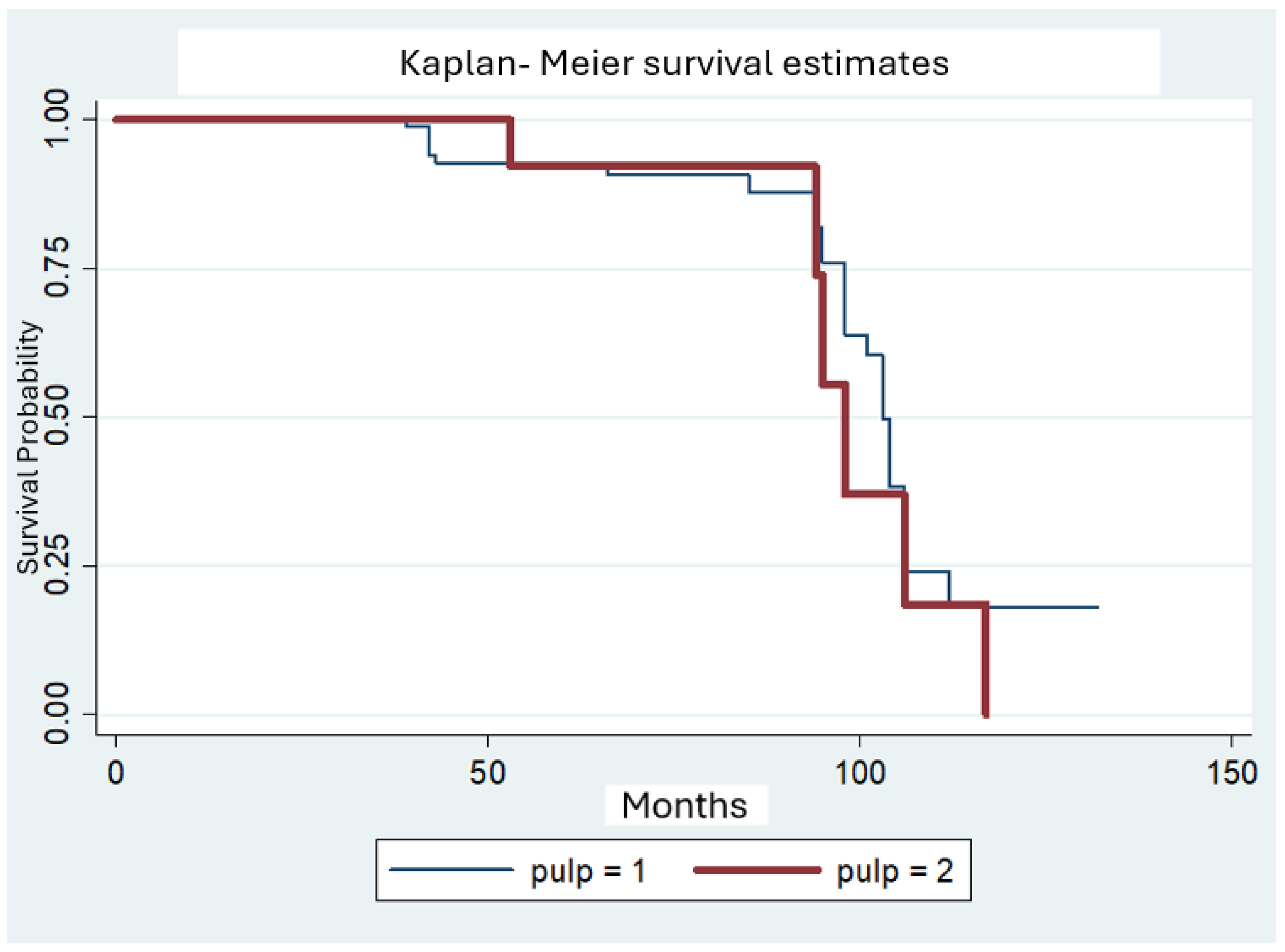

The Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to calculate the survival probabilities for each of the two materials used for the fabrication of the indirect partial coverage restorations (Fig. 1). For composite restorations, the estimated survival rate was 94.2% after 5 years but dropped to 74.3% at 95 months (7.9 years) and continued dropping to less than 60% after 98 months. On the contrary, for ceramic restorations the estimated survival rate was 90.9% after 5 years, dropped to 85.2% after 5.5 years and remained at 85.2% for the rest of the observation period. When both the restoration type and the restoration material variables were examined, statistically significant differences were observed between ceramic and composite onlays, with the ceramic onlays performing better than composite onlays for the observation period. (Fig. 2). Consequently, ceramic partial coverage restorations tend to show more favorable clinical behavior compared to composites in the long term.

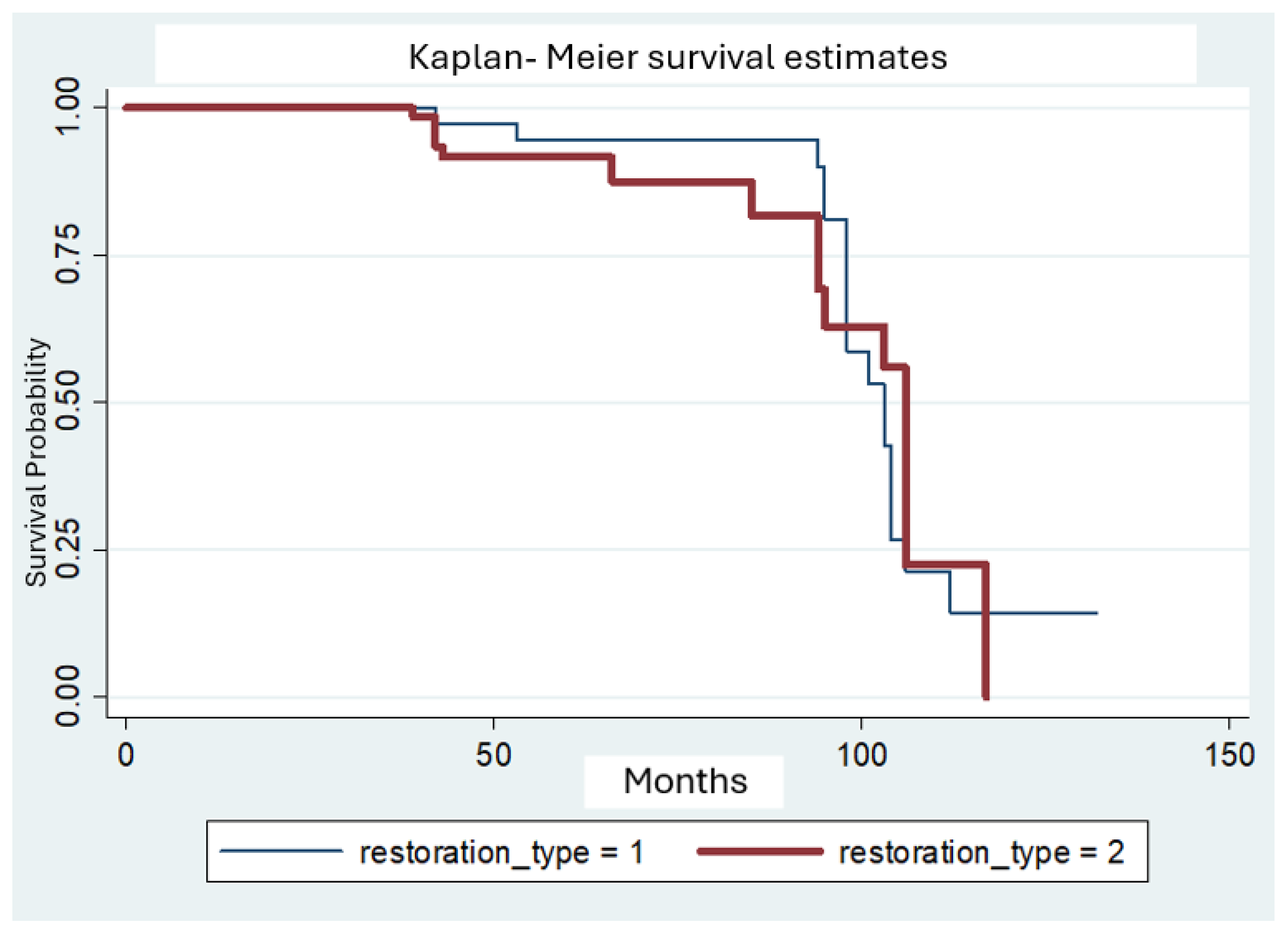

The Kaplan-Meier methodology was also used to calculate the survival probabilities for each of the two types of restorations (onlays vs overlays) (Fig. 3). For onlays, the estimated survival rate was 94.6% after 5 years but dropped to 58.5% after 8 years and reached less than 50% after 102 months. For overlays, the estimated survival rate was 91.6% after 5 years, dropping to less than 60% after 102 months.

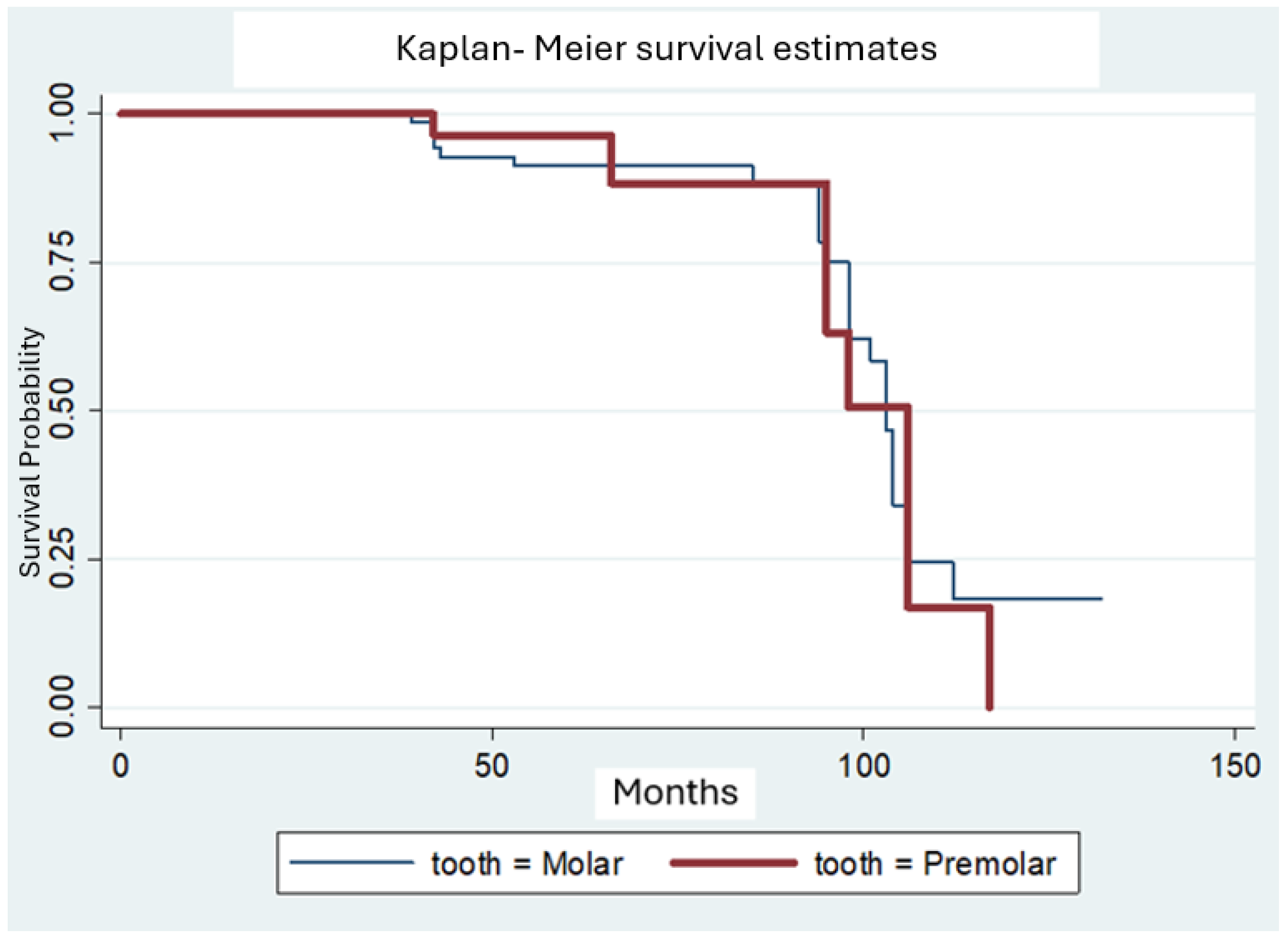

Moreover, the Kaplan-Meier methodology was used to calculate the survival probabilities for molars and premolars separately (Fig. 4). For molars, the estimated survival rate was 91.2% after 5 years, dropped to less than 70% after 8 years and declined further to less than 50% after 102 months. For premolars, the estimated survival rate was less than 90% after 5 years, dropped to less than 60% after 8 years and declined further to less than 50% after 106 months.

Finally, the survival probabilities for vital and endodontically treated teeth were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier methodology (Fig. 5). For vital teeth, the estimated survival rate was 92.8% after 5 years, dropped to 88% after 7 years and declined further at less than 50% after 102 months. For endodontically treated teeth, the estimated survival rate was 92.3% after 5 years and dropped to 55% after almost 8 years (95 months).

Cox regression analysis failed to show linkage of the survival of the indirect partial restorations with any of the following covariates: restoration material (composite/ceramic), tooth type (molar/premolar), restoration type (onlay/overlay), presence of previous endodontic treatment, as presented in

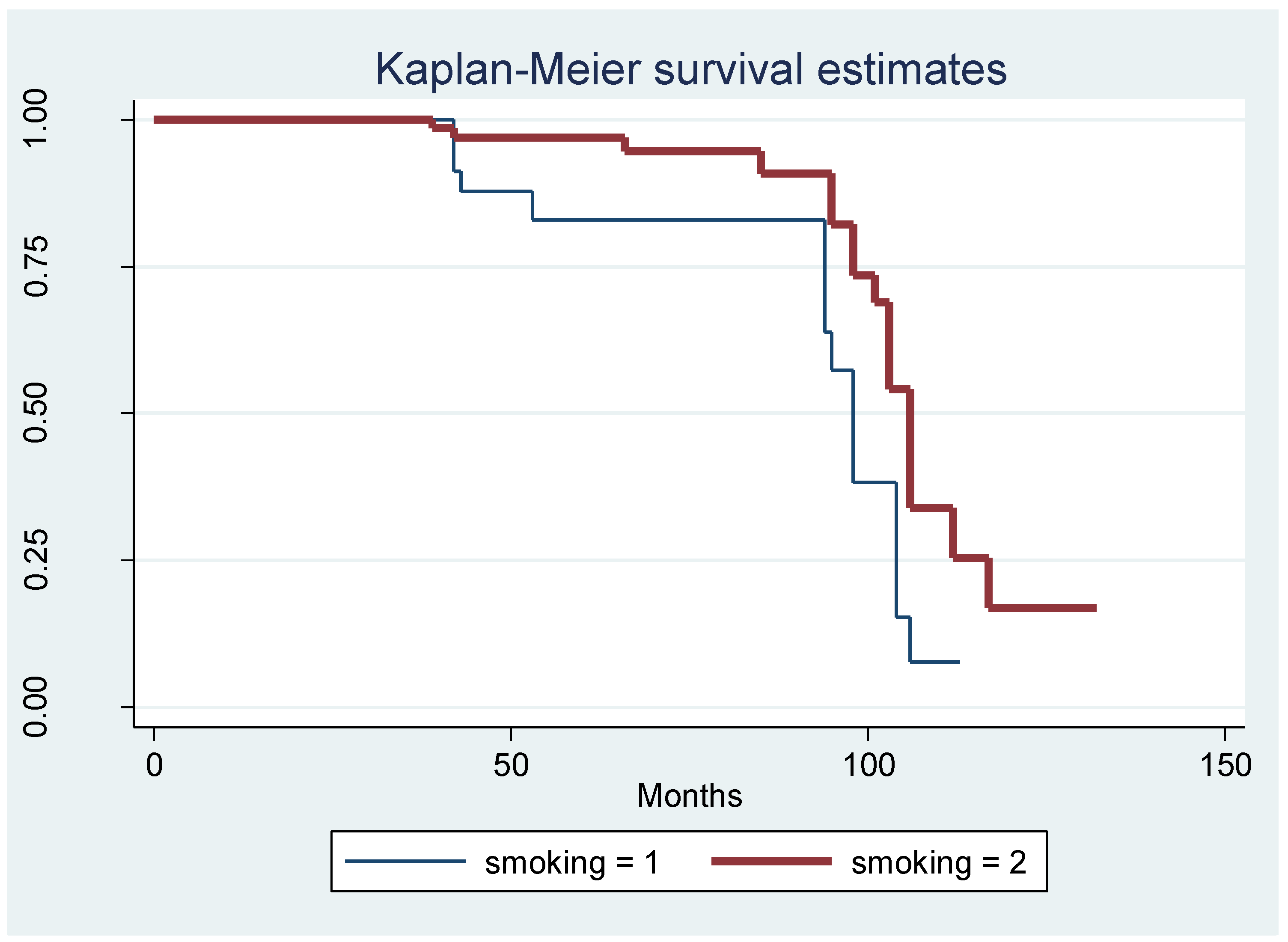

Table 5. On the other hand, Cox regression analysis revealed a statistically significant difference for smoking (p<0.05) (Fig. 5). It should be noted that even though ceramic partial coverage restorations show more favorable clinical behavior compared to composites in the long term, no statistically significant difference was observed. This can be attributed to the relatively low number of failures of ceramic restorations compared to the composite ones. Perhaps with a higher number of failures, significance could be detected.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to the fabrication material (1=composite, 2=ceramic).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to the fabrication material (1=composite, 2=ceramic).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to the restoration type and the restoration material (1= onlay, 2= overlay, 1=composite, 2= ceramic).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to the restoration type and the restoration material (1= onlay, 2= overlay, 1=composite, 2= ceramic).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to the restoration type (1=onlay, 2=overlay).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to the restoration type (1=onlay, 2=overlay).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to the tooth type (1=molar, 2=premolar).

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to the tooth type (1=molar, 2=premolar).

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to the presence of endodontic treatment (1=vital pulp, 2=endodontic treatment).

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to the presence of endodontic treatment (1=vital pulp, 2=endodontic treatment).

Figure 6.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to smoking (1=smoking, 2=no smoking).

Figure 6.

Kaplan-Meier survival rates for indirect partial coverage restorations according to smoking (1=smoking, 2=no smoking).

4. Discussion

In this retrospective clinical study, the clinical behavior of ceramic and composite indirect restorations for an extended observation period was evaluated. The study’s results indicate that ceramic indirect restorations survival exhibited no statistical differences compared to resin composite indirect restorations. Therefore, the first null-hypothesis that there is no difference in long-term survival of ceramic and resin composite indirect restorations was accepted. Evaluating the possible risk factors, smoking had a statistically significant impact on the survival of indirect partial restorations. Thus, the second null- hypothesis was partially rejected.

In the present study, indirect composite restorations reached a survival rate of 94.2% after 5 years, dropping to 74.3% after 7.9 years and less than 60% after 8.17 years. The main reasons for failure were material fracture and caries. Few studies have retrospectively assessed indirect composite cusp-covering restorations and their findings are in agreement with the present study. A retrospective study [

9] found a survival rate for indirect composite resins of 91.1% after 5 years. Secondary caries was the most common reason for failure observed on the interproximal side of the restorations. In another retrospective study) [

11], indirect composite restorations had a survival rate of 81% after 10 years and restoration fracture was the main reason for failure.

In the present study, for ceramic indirect restorations, survival rate reached 90.9% after 5 years, 85.2% after 5.5 years and for the rest of observation period. Ceramic fracture was the only type of failure observed. The results of the present study are generally in agreement with the findings from the literature. In a 4-year retrospective study [

15], survival rate of ceramic onlays placed on molars and premolars was 92.7%, with material fracture being the main reason for failure. In a long-term retrospective study [

16], the estimated Kaplan-Meier survival rate of the restorations at the restoration level was 92.3% after 10 years and 83.8% after 14 years. Ceramic fractures and chipping were the most frequent complications. Another retrospective study assessing the long-term performance of ceramic indirect restorations [

18], concluded that ceramic indirect restorations reached a survival rate of 91.8% after 23.5 years. Finally, in retrospective clinical study [

17], ceramic indirect restorations had a survival rate of 96,3% after 2 years, 91,5% after 4 years and then dropped to 67,4% after 6 years.

Even though a lot of clinical trials evaluate the survival of ceramic and composite indirect restorations separately [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], clinical outcomes from a long-term comparison between both materials are still lacking. Similar to the results of the present study, other clinical studies [

19,

20,

21] found no significant differences between survival rates for both materials. Nevertheless, in the present study the estimated survival rate for composite restorations dropped to 74.3% at almost 8 years and continued dropping to less than 60% after 98 months, while the estimated survival rate for ceramics dropped to 85.2% after 5.5 years and remained stable for the rest of the observation period. Therefore, ceramic partial coverage restorations tend to show more favorable clinical behavior compared to composites in the long term. Moreover, when Kaplan-Meier survival rates were calculated for both material and type of restoration, a statistically significant difference between ceramic onlays and composite onlays was revealed, with ceramic onlays performing better during the observation period. This finding agrees with a previous retrospective study [

21], where the AFR of LiSi and resin composite indirect partial restorations were 0.2% and 1% respectively. and strengthens the conviction that ceramic indirect restorations tend to have a better clinical behavion than composites in the long-term. In that study [

21], the survival probability was above 98% for both restorations in the first 6 years and dropped to 60% for composite by the end of the 15th year. Meanwhile, similar to the results of the present study, the probability of survival remained high (> 95%) in the long term for lithium disilicate restorations. These findings are also in agreement with a systematic review and meta-analysis [

23], which demonstrated a higher probability of failure for indirect composites compared to ceramic materials. It must be noted, however, that in that study a meta-analysis of composite resin was not possible because no studies of overlays, onlays, and inlays from this material were included during the data collection phase. In another systematic review and meta-analysis, lithium disilicate and indirect composite materials demonstrate comparable survival rates in short-term follow-up, while on short- to medium-term follow-up, neither leucite restorations nor indirect composite restorations demonstrated significant superiority [

24]. In the present study, results might have been different if there was a higher number of restorations.

Cox regression analysis failed to show linkage of the survival of indirect restorations with tooth type (molar/premolar). This finding is in agreement with other studies [

12,

13,

14,

16,

17,

18,

23]. However, Ravasini et al (2018) [

11] found that the risk of failure in premolars was significantly lower compared to molars, probably because of higher occlusal loads in molar region, making them more prone to fracture. Especially, Murgueitio et al (2012) [

27] found that second molars were five times more susceptible to failure than first molars while there were no failures at premolars. Also, Naeselius et al (2008) [

15] indicated that after 4 years of observation of ceramic onlays, all recorded failures were at molars, although without statistical significance.

In addition, in the present study, Cox regression analysis showed that restoration type (onlay/overlay) did not affect the survival of restorations. This outcome agrees with other studies [

9,

11]. Also, many studies [

7,

13,

16] have drawn the same conclusion for onlays and inlays. In a prospective clinical trial [

8], the risk for failure appeared approximately 8 times higher for overlays than onlays, reaching a statistically significant difference. These failures, mostly fractures, usually occur after a short period of time, probably due to mechanical properties of composite materials, making them usually unable to withstand occlusal forces in full cuspal coverage restorations, especially in cavities without immediate dentin sealing.

Tooth vitality did not significantly affect survival rates in this clinical study. This finding is in accordance with other clinical studies [

8,

12,

20]. It should be noted, however, that the number of endodontically treated teeth included in the study was rather low (16 out of 112). On the other hand, in a 15-year retrospective study [

14], the failure frequency in vital teeth was 20.9%, while in non-vital teeth 39.0%. These differences were significantly different both for failure frequency and for years of survival due to reduced available retention area compared to vital teeth. The difference was attributed to the differences in substrate to which the hydrophilic primers were applied, hydrophilic dentin in vital teeth vs. more sclerotic less-water containing dentin tissue in endodontically treated teeth. In addition, in another study [

27] it was found that non vital teeth had significantly higher possibility of failure than vital teeth, possibly because of higher cuspal deflexion and reduced stiffness of the non vital teeth due to endodontic access and restorative procedures. According to a systematic review and metanalyses [

26] indirect partial restorations on endodontically treated teeth showed acceptable clinical performance for a medium follow-up period of 2 to 4 years. Failures increased considerably after 7 years and up to 12-30 years. However, most failures were restorable, preventing tooth loss. Furthermore, in another systematic review and metanalysis [

23], the chance of failure was 80% less in vital teeth compared to endodontically treated teeth, making tooth vitality a significant factor for the survival of indirect restorations.

In this study, Cox regression analysis revealed a statistically significant influence of smoking on the restorations’ survival (p <0.05). This is a finding that cannot be easily explained clinically or biologically. While smoking is known to affect periodontal health status and implants survival, its direct effect on indirect posterior restorations is less clear, which makes this a novel and potentially interesting finding. Despite the lack of documentation on the topic, there could be some indirect mechanisms affecting the results. One possible mechanism for this finding could be attributed to an increased risk of caries in smokers. In a systematic review, tobacco smoking was found to be associated with an increased risk of dental caries. However, the overall poor quality of studies produced no validation for such an association [

28]. Moreover, behavioral factors in smokers could also affect restorations survival, for example smokers are less likely to seek regular dental care or maintain proper oral hygiene. Further, more extensive research on this topic and prospective studies are needed. The findings of the present study agree with a study where smoking, as a reason for indirect composites’ restorations failure, was close to significance and smokers had a risk of failure almost twice as high as non-smokers. On the other hand, in another study [

16] no statistical difference was found between smokers and non-smokers for the survival of indirect ceramic restorations. Differences in the results of the latter two studies can be attributed to differences in the materials. In general, dental restorations can be compromised by smoking. Dental ceramic and composite resin restorations were compared in an in vitro study [

29] revealing that composite resins were more susceptible to the effects of conventional and electronic cigarettes, suggesting that ceramic restorations might offer better color stability when patients are smokers. Nevertheless, in the present study, no restoration failed due to discoloration. Therefore, more clinical studies are needed for the evaluation of smoking as a risk factor for indirect restorations’ long-term survival.

Analysing the current data some limitations must be considered. Most importantly the data are based on a retrospective study. The clinical quality of the restorations as found up to 11 years can, thus, not be compared with the baseline situation allowing conclusions on changes during the observation period. Another limitation of the present study is the participants recall rate (67.1%). This is a weakness inherent with all clinical studies. Moreover, it can be a possible source of bias because those participants who responded to the study recruitment might be the ones that were generally more motivated to take care of their oral health. Furthermore, all patients were not treated with the same restorative materials, bonding protocols or resin cements. It is not possible therefore to make comparisons and draw conclusions on the effect of the materials used. On the other hand, the current study also shows several benefits. All restorations were examined by two independent and calibrated dentists. Therefore, a strong bias in the evaluation of the study restorations can be excluded. Moreover, the patient sample is more representative than a chosen subgroup of the population because no exclusion criteria were applied to the recruited participants. Another advantage is that the restorations have been placed by post-graduate students with various levels of experience. The current research demonstrates that partial coverage indirect restorations placed during a post-graduate clinical training program have good clinical performance and lifespan, comparable with the findings of research conducted by experienced operators.