Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Construction of Phylogenetic Trees

2.2. Identification of Conserved Signature Indels (CSIs)

2.4. Determination of Protein Structures Using AlphaFold Model Generation to Map the Locations of CSIs

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenomic Tree for the Lactobacillaceae Species

3.2. Conserved Signature Indels Specific for Different Lactobacillaceae Genera

3.3. Molecular Markers Specific for the Genera Lactobacillus, Lacticaseibacillus Lactiplantibacillus and Apilactobacillus

3.4. Predictive Ability of the CSIs and Their Application in Predicting the Taxonomic Affiliations of other Lactobacillus spp./Isolates

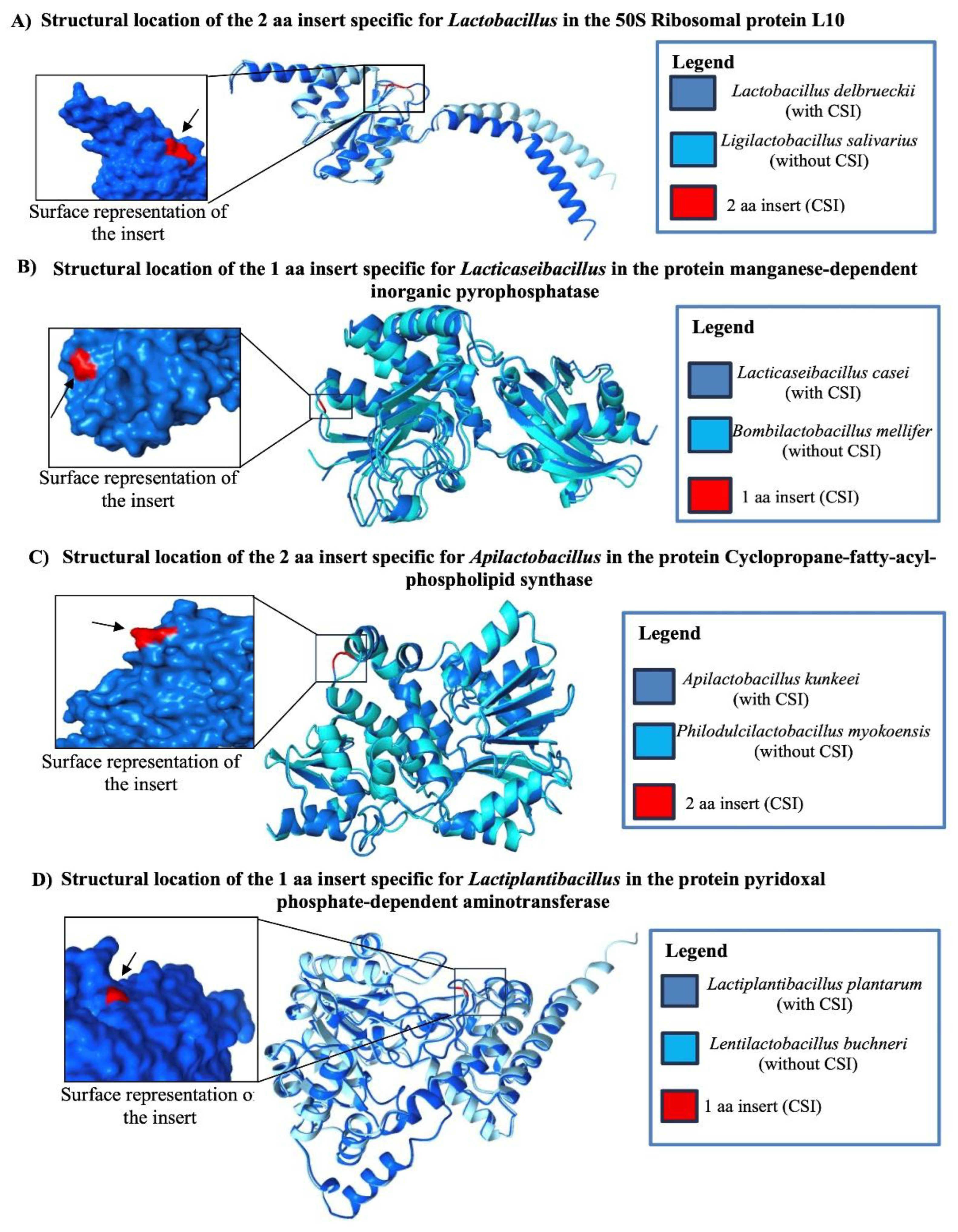

3.5. Taxon-specific CSIs are Localized in Surface Exposed Loops of Proteins

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skerman, V.B.D.; McGowan, V.; Sneath, P.H.A. Approved lists of bacterial names. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1980, 30, 225–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winslow, C.; Broadhurst, J.B., RE.; Krumwiede, C.R. , LA, Smith GH. The Families and Genera of the Bacteria: Preliminary Report of the Committee of the Society of American Bacteriologists on Characterization and Classification of Bacterial Types. J. Bacteriol. Res. 1917, 2, 505–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wittouck, S.; Salvetti, E.; Franz, C.M.A.P.; Harris, H.M.B.; Mattarelli, P.; O’Toole, P.W.; Pot, B.; Vandamme, P.; Walter, J.; et al. A taxonomic note on the genus Lactobacillus: Description of 23 novel genera, emended description of the genus Lactobacillus Beijerinck 1901, and union of Lactobacillaceae and Leuconostocaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2020, 70, 2782–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.G. Lactic metabolism revisited: metabolism of lactic acid bacteria in food fermentations and food spoilage. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 2, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvetti, E.; Harris, H.M.B.; Felis, G.E.; O’Toole, P.W. Comparative Genomics of the Genus Lactobacillus Reveals Robust Phylogroups That Provide the Basis for Reclassification. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00993–00918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleifer, K.H. Family V. Leuconostocaceae fam. nov. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (The Firmicutes), 2nd edn, 2009, 3, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, T.T.S., E; Endo, A.; Johansson, P. ,; Bjorkroth,J. The family Leuconostocaceae In The Prokaryotes: Firmicutes and Tenericutes:; Springer-Verlag: 2014; pp. 215-240.

- Danza, A.; Lucera, A.; Lavermicocca, P.; Lonigro, S.L.; Bavaro, A.R.; Mentana, A.; Centonze, D.; Conte, A.; Del Nobile, M.A. Tuna Burgers Preserved by the Selected Lactobacillus paracasei IMPC 4.1 Strain. Food Bioproc Tech 2018, 11, 1651–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Qiao, N.; Xiao, Y.; Tian, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W.; Zhai, Q. Latilactobacillus curvatus: A Candidate Probiotic with Excellent Fermentation Properties and Health Benefits. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.R.; Deng, H.; Hu, C.Y.; Zhao, P.T.; Meng, Y.H. Vitality, fermentation, aroma profile, and digestive tolerance of the newly selected Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Lacticaseibacillus paracasei in fermented apple juice. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.; Endo, A. The Family Lactobacillaceae: Genera Other than Lactobacillus. In The Prokaryotes: Firmicutes and Tenericutes, Rosenberg, E., DeLong, E.F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E., Thompson, F., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; pp. 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, V.; Chieffi, D.; Fanelli, F.; Montemurro, M.; Rizzello, C.G.; Franz, C.M. The Weissella and Periweissella genera: Up-to-date taxonomy, ecology, safety, biotechnological, and probiotic potential. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1289937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, N.; Wittouck, S.; Mattarelli, P.; Zheng, J.; Lebeer, S.; Felis, G.E.; Gänzle, M.G. After the storm-Perspectives on the taxonomy of Lactobacillaceae. JDS Commun 2022, 3, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittouck, S.; Wuyts, S.; Meehan, C.J.; Noort, V.v.; Lebeer, S. A Genome-Based Species Taxonomy of the Lactobacillus Genus Complex. mSystems 2019, 4, e00264–00219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duar, R.M.; Lin, X.B.; Zheng, J.; Martino, M.E.; Grenier, T.; Pérez-Muñoz, M.E.; Leulier, F.; Gänzle, M.; Walter, J. Lifestyles in transition: evolution and natural history of the genus Lactobacillus. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2017, 41, S27–s48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, S.; Rudra, B.; Gupta, R.S. Phylogenomic and comparative genomic analyses of Leuconostocaceae species: identification of molecular signatures specific for the genera Leuconostoc, Fructobacillus and Oenococcus and proposal for a novel genus Periweissella gen. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2022, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S. Protein phylogenies and signature sequences: A reappraisal of evolutionary relationships among archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 1998, 62, 1435–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S. Impact of genomics on the understanding of microbial evolution and classification: the importance of Darwin’s views on classification. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2016, 40, 520–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokas, A.; Holland, P.W.H. Rare genomic changes as a tool for phylogenetics. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2000, 15, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, V.; Naushad, H.S.; Gupta, R.S. Protein based molecular markers provide reliable means to understand prokaryotic phylogeny and support Darwinian mode of evolution. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2012, 2, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naushad, H.S.; Lee, B.; Gupta, R.S. Conserved signature indels and signature proteins as novel tools for understanding microbial phylogeny and systematics: identification of molecular signatures that are specific for the phytopathogenic genera Dickeya, Pectobacterium and Brenneria. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2014, 64, 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Patel, S.; Saini, N.; Chen, S. Robust demarcation of 17 distinct Bacillus species clades, proposed as novel Bacillaceae genera, by phylogenomics and comparative genomic analyses: description of Robertmurraya kyonggiensis sp. nov. and proposal for an emended genus Bacillus limiting it only to the members of the Subtilis and Cereus clades of species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2020, 70, 5753–5798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Harris, H.M.; McCann, A.; Guo, C.; Argimón, S.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Jeffery, I.B.; Cooney, J.C.; Kagawa, T.F.; et al. Expanding the biotechnology potential of lactobacilli through comparative genomics of 213 strains and associated genera. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 8322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraffa, G.; Chanishvili, N.; Widyastuti, Y. Importance of lactobacilli in food and feed biotechnology. Research in Microbiology 2010, 161, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lv, J.; Pan, L.; Zhang, Y. Roles and applications of probiotic Lactobacillus strains. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2018, 102, 8135–8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Maeno, S.; Tanizawa, Y.; Kneifel, W.; Arita, M.; Dicks, L.; Salminen, S. Fructophilic Lactic Acid Bacteria, a Unique Group of Fructose-Fermenting Microbes. Appl Environ Microbiol 2018, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parte, A.C.; Sarda Carbasse, J.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Reimer, L.C.; Goker, M. List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN) moves to the DSMZ. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2020, 70, 5607–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E.W.; Agarwala, R.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Canese, K.; Clark, K.; Connor, R.; Fiorini, N.; Funk, K.; Hefferon, T. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res 2019, 47, D23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parte, A.C. LPSN–List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (bacterio. net), 20 years on. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2018, 68, 1825–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; McCluskey, K.; Desmeth, P.; Liu, S.; Hideaki, S.; Yin, Y.; Moriya, O.; Itoh, T.; Kim, C.Y.; Lee, J.S.; et al. The global catalogue of microorganisms 10K type strain sequencing project: closing the genomic gaps for the validly published prokaryotic and fungi species. Gigascience 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Seshadri, R.; Varghese, N.J.; Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A.; Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M.; Coates, R.C.; Hadjithomas, M.; Pavlopoulos, G.A.; Paez-Espino, D.; et al. 1,003 reference genomes of bacterial and archaeal isolates expand coverage of the tree of life. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, W.B. Genome sequences as the type material for taxonomic descriptions of prokaryotes 1. Syst Appl Microbiol 2015, 38, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S. Identification of Conserved Indels that are Useful for Classification and Evolutionary Studies. In Bacterial Taxonomy, Methods in microbiology, Goodfellow, M., Sutcliffe, I., Chun, J., Eds.; Elsevier: 2014; Volume 41, pp. 153-182.

- Gupta, R.S.; Kanter-Eivin, D. AppIndels.com Server: A Web Based Tool for the Identification of Known Taxon-Specific Conserved Signature Indels in Genome Sequences: Validation of Its Usefulness by Predicting the Taxonomic Affiliation of >700 Unclassified strains of Bacillus Species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2023, 73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, M. A phylum-level bacterial phylogenetic marker database. Mol Biol Evol 2013, 30, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeolu, M.; Alnajar, S.; Naushad, S.; R, S.G. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: proposal for Enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. nov., Morganellaceae fam. nov., and Budviciaceae fam. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2016, 66, 5575–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S.R. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 1998, 14, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, F.; Wilm, A.; Dineen, D.; Gibson, T.J.; Karplus, K.; Li, W.; Lopez, R.; McWilliam, H.; Remmert, M.; Söding, J.; et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011, 7, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, S.; Goldman, N. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Mol Biol Evol 2001, 18, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanmougin, F.; Thompson, J.D.; Gouy, M.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. Multiple sequence alignment with Clustal X. Trends Biochem Sci 1998, 23, 403–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8. (No Title) 2015.

- Mariani, V.; Biasini, M.; Barbato, A.; Schwede, T. lDDT: a local superposition-free score for comparing protein structures and models using distance difference tests. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 2722–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Skolnick, J. Scoring function for automated assessment of protein structure template quality. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Bioinf. 2004, 57, 702–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.B.; Perminov, A.; Bekele, S.; Kedziora, G.; Farajollahi, S.; Varaljay, V.; Hinkle, K.; Molinero, V.; Meister, K.; Hung, C.; et al. AlphaFold2 models indicate that protein sequence determines both structure and dynamics. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 10696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobritsa, A.P.; Linardopoulou, E.V.; Samadpour, M. Transfer of 13 species of the genus Burkholderia to the genus Caballeronia and reclassification of Burkholderia jirisanensis as Paraburkholderia jirisanensis comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2017, 67, 3846–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecillo, J.A.V.; Bae, H. Reclassification of Brevibacterium frigoritolerans as Peribacillus frigoritolerans comb. nov. based on phylogenomics and multiple molecular synapomorphies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2022, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, D.; Kim, J.-S.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, J. Reclassification of genus Izhakiella into the family Erwiniaceae based on phylogenetic and genomic analyses. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2021, 70, 3541–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Ruan, L.; Sun, M.; Gänzle, M. A Genomic View of Lactobacilli and Pediococci Demonstrates that Phylogeny Matches Ecology and Physiology. Appl Environ Microbiol 2015, 81, 7233–7243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M.D.; Rodrigues, U.; Ash, C.; Aguirre, M.; Farrow, J.A.E.; Martinez-Murcia, A.; Phillips, B.A.; Williams, A.M.; Wallbanks, S. Phylogenetic analysis of the genus Lactobacillus and related lactic acid bacteria as determined by reverse transcriptase sequencing of 16S rRNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1991, 77, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvetti, E.; Torriani, S.; Felis, G.E. The Genus Lactobacillus: A Taxonomic Update. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins 2012, 4, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.B.; Baiseitova, A.; Zahoor, M.; Ahmad, I.; Ikram, M.; Bakhsh, A.; Shah, M.A.; Ali, I.; Idress, M.; Ullah, R.; et al. Probiotic significance of Lactobacillus strains: a comprehensive review on health impacts, research gaps, and future prospects. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2431643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Guchte, M.; Penaud, S.; Grimaldi, C.; Barbe, V.; Bryson, K.; Nicolas, P.; Robert, C.; Oztas, S.; Mangenot, S.; Couloux, A.; et al. The complete genome sequence of Lactobacillus bulgaricus reveals extensive and ongoing reductive evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006, 103, 9274–9279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, T.; Hu, H.; Tian, J.; He, B.; Tai, J.; He, Y. Influence of Different Ratios of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus on Fermentation Characteristics of Yogurt. Molecules 2023, 28, 2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconu, M.; Kothe, U.; Schlünzen, F.; Fischer, N.; Harms, J.M.; Tonevitsky, A.G.; Stark, H.; Rodnina, M.V.; Wahl, M.C. Structural basis for the function of the ribosomal L7/12 stalk in factor binding and GTPase activation. Cell 2005, 121, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.-K.; Lu, Y.-C.; Hsieh, C.-R.; Wei, C.-K.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Chang, F.-R.; Chan, Y. Developing Lactic Acid Bacteria as an Oral Healthy Food. Life 2021, 11, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groote, M.A.; Frank, D.N.; Dowell, E.; Glode, M.P.; Pace, N.R. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG bacteremia associated with probiotic use in a child with short gut syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2005, 24, 278–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeno, S.; Nishimura, H.; Tanizawa, Y.; Dicks, L.; Arita, M.; Endo, A. Unique niche-specific adaptation of fructophilic lactic acid bacteria and proposal of three Apilactobacillus species as novel members of the group. BMC Microbiology 2021, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, E.L.; Wax, N.; Bueren, E.K.; Walke, J.B.; Fell, R.; Belden, L.K.; Haak, D.C. Comparative genomics of Lactobacillaceae from the gut of honey bees, Apis mellifera, from the Eastern United States. G3 (Bethesda) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidanza, M.; Panigrahi, P.; Kollmann, T.R. Lactiplantibacillus plantarum-Nomad and Ideal Probiotic. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 712236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Tian, Z.; Si, Y.; Chen, H.; Gan, J. The Mechanisms of the Potential Probiotic Lactiplantibacillus plantarum against Cardiovascular Disease and the Recent Developments in its Fermented Foods. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, A.G.; Adeolu, M.; Gupta, R.S. Division of the genus Borrelia into two genera (corresponding to Lyme disease and relapsing fever groups) reflects their genetic and phenotypic distinctiveness and will lead to a better understanding of these two groups of microbes (Margos et al. (2016) There is inadequate evidence to support the division of the genus Borrelia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1099/ijsem.0.001717). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2017, 67, 2058-2067.

- Rudra, B.; Gupta, R.S. Molecular Markers Specific for the Pseudomonadaceae Genera Provide Novel and Reliable Means for the Identification of Other Pseudomonas strains/spp. Related to These Genera. Genes 2025, 16, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, M.; Bello, S.; Gupta, R.S. Phylogenomic and molecular markers based studies on clarifying the evolutionary relationships among Peptoniphilus species. Identification of several Genus-Level clades of Peptoniphilus species and transfer of some Peptoniphilus species to the genus Aedoeadaptatus. Syst Appl Microbiol 2024, 47, 126499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Okada, S. Reclassification of the genus Leuconostoc and proposals of Fructobacillus fructosus gen. nov., comb. nov., Fructobacillus durionis comb. nov., Fructobacillus ficulneus comb. nov. and Fructobacillus pseudoficulneus comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2008, 58, 2195–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Tanizawa, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Maeno, S.; Kumar, H.; Shiwa, Y.; Okada, S.; Yoshikawa, H.; Dicks, L.; Nakagawa, J.; Arita, M. Comparative genomics of Fructobacillus spp. and Leuconostoc spp. reveals niche-specific evolution of Fructobacillus spp. BMC Genomics, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiva, E.; Itzhaki, Z.; Margalit, H. Built-in loops allow versatility in domain-domain interactions: lessons from self-interacting domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008, 105, 13292–13297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormozdiari, F.; Salari, R.; Hsing, M.; Schönhuth, A.; Chan, S.K.; Sahinalp, S.C.; Cherkasov, A. The effect of insertions and deletions on wirings in protein-protein interaction networks: a large-scale study. J Comput Biol 2009, 16, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, B.; Persaud, D.; Gupta, R.S. Novel Sequence Feature of SecA Translocase Protein Unique to the Thermophilic Bacteria: Bioinformatics Analyses to Investigate Their Potential Roles. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miton, C.M.; Tokuriki, N. Insertions and Deletions (Indels): A Missing Piece of the Protein Engineering Jigsaw. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S.; Nanda, A.; Khadka, B. Novel molecular, structural and evolutionary characteristics of the phosphoketolases from Bifidobacteria and Coriobacteriales. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0172176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geszvain, K.; Gruber, T.M.; Mooney, R.A.; Gross, C.A.; Landick, R. A hydrophobic patch on the flap-tip helix of E.coli RNA polymerase mediates sigma(70) region 4 function. J Mol Biol 2004, 343, 569–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadka, B.; Gupta, R.S. Identification of a conserved 8 aa insert in the PIP5K protein in the Saccharomycetaceae family of fungi and the molecular dynamics simulations and structural analysis to investigate its potential functional role. Proteins 2017, 85, 1454–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Panchenko, A.R. Mechanisms of protein oligomerization, the critical role of insertions and deletions in maintaining different oligomeric states. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 20352–20357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.S. Distinction between Borrelia and Borreliella is more robustly supported by molecular and phenotypic characteristics than all other neighbouring prokaryotic genera: Response to Margos’ et al. “The genus Borrelia reloaded” (PLoS ONE 13(12): e0208432). PLoS One 2019, 14, e0221397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudill, M.T.; Brayton, K.A. The Use and Limitations of the 16S rRNA Sequence for Species Classification of Anaplasma Samples. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, J.M.; Abbott, S.L. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing for Bacterial Identification in the Diagnostic Laboratory: Pluses, Perils, and Pitfalls. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2007, 45, 2761–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.; Gupta, R.S. A phylogenomic and comparative genomic framework for resolving the polyphyly of the genus Bacillus: Proposal for six new genera of Bacillus species, Peribacillus gen. nov., Cytobacillus gen. nov., Mesobacillus gen. nov., Neobacillus gen. nov., Metabacillus gen. nov. and Alkalihalobacillus gen. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2020, 70, 406–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawana, A.; Adeolu, M.; Gupta, R.S. Molecular signatures and phylogenomic analysis of the genus Burkholderia: proposal for division of this genus into the emended genus Burkholderia containing pathogenic organisms and a new genus Paraburkholderia gen. nov. harboring environmental species. Front Genet 2014, 5, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobritsa, A.P.; Samadpour, M. Reclassification of Burkholderia insecticola as Caballeronia insecticola comb. nov. and reliability of conserved signature indels as molecular synapomorphies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2019, 69, 2057–2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, B.; Gupta, R.S. Phylogenomic and comparative genomic analyses of species of the family Pseudomonadaceae: Proposals for the genera Halopseudomonas gen. nov. and Atopomonas gen. nov., merger of the genus Oblitimonas with the genus Thiopseudomonas, and transfer of some misclassified species of the genus Pseudomonas into other genera. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 2021, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, B.; Gupta, R.S. Phylogenomics studies and molecular markers reliably demarcate genus Pseudomonas sensu stricto and twelve other Pseudomonadaceae species clades representing novel and emended genera. Front Microbiol 2024, 14, 1273665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmod, N.Z.; Gupta, R.S.; Shah, H.N. Identification of a Bacillus anthracis specific indel in the yeaC gene and development of a rapid pyrosequencing assay for distinguishing B. anthracis from the B. cereus group. J Microbiol Methods 2011, 87, 278–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.Y.; Paschos, A.; Gupta, R.S.; Schellhorn, H.E. Insertion/deletion-based approach for the detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in freshwater environments. Environ Sci Technol 2014, 48, 11462–11470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Gupta, R.S. Conserved indels in protein sequences that are characteristic of the phylum Actinobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 2005, 55, 2401–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, E.; Petrich, A.; Gupta, R.S. Conserved Indels in Essential Proteins that are Distinctive Characteristics of Chlamydiales and Provide Novel Means for Their Identification. Microbiology 2005, 151, 2647–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Gupta, R.S. Conserved inserts in the Hsp60 (GroEL) and Hsp70 (DnaK) proteins are essential for cellular growth. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2009, 281, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J.H.; Irvine, R.F. Evolutionarily conserved structural changes in phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase (PI5P4K) isoforms are responsible for differences in enzyme activity and localization. Biochem J 2013, 454, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznedelov, K.; Minakhin, L.; Niedziela-Majka, A.; Dove, S.L.; Rogulja, D.; Nickels, B.E.; Hochschild, A.; Heyduk, T.; Severinov, K. A role for interaction of the RNA polymerase flap domain with the sigma subunit in promoter recognition. Science 2002, 295, 855–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandan, D.; Lopez, M.; Ban, F.; Huang, M.; Li, Y.; Reiner, N.E.; Cherkasov, A. Indel-based targeting of essential proteins in human pathogens that have close host orthologue(s): discovery of selective inhibitors for Leishmania donovani elongation factor-1alpha. Proteins 2007, 67, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.Y.; Cronan, J.E., Jr. Membrane cyclopropane fatty acid content is a major factor in acid resistance of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 1999, 33, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, B.; Guo, Q.; Wang, H.; Hang, X.; Zeng, L.; Jia, J.; Bi, H. The Cyclopropane Fatty Acid Synthase Mediates Antibiotic Resistance and Gastric Colonization of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol 2019, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, S.; Lee, K.H.; Yoo, J.; Yun, J.; Kang, H.B.; Kim, J.E.; Oh, M.H.; Ham, J.S. Whole genome sequencing of Lacticaseibacillus casei KACC92338 strain with strong antioxidant activity, reveals genes and gene clusters of probiotic and antimicrobial potential. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1458221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergalito, F.; Testa, B.; Cozzolino, A.; Letizia, F.; Succi, M.; Lombardi, S.J.; Tremonte, P.; Pannella, G.; Di Marco, R.; Sorrentino, E.; et al. Potential Application of Apilactobacillus kunkeei for Human Use: Evaluation of Probiotic and Functional Properties. Foods 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percudani, R.; Peracchi, A. A genomic overview of pyridoxal-phosphate-dependent enzymes. EMBO Rep 2003, 4, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B.J.B.; Holzapfel, W.H.N.; Hammes, W.P.; Vogel, R.F. The Genera of Lactic Acid Bacteria, 1 ed.; Wood, B.J.B., Ed.; Springer US: 1995; Volume 2, p. 398.

| Protein Name | Accession No. | Indel Size | Indel Position | Figure No. | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50S ribosomal protein L10 | WP_046332409 | 2 aa Ins | 57-112 |

Figure 2 Figure S2 |

Lactobacillus |

| excinuclease ABC subunit UvrC | WP_003619779 | 5-6 aa Ins | 480-531 | Figure S3 | |

| Anaerobic ribonucleoside-triphosphate reductase§ | WP_011161356 | 2 aa Ins | 517-562 | Figure S4 | |

| DNA-binding protein WhiA | WP_004893933 | 1 aa Ins | 140-194 | Figure S5 | |

| Translation initiation factor IF-2 | WP_011544002 | 3 aa Ins | 285-336 | Figure S6 | |

| 50S ribosomal protein L4 | WP_046332456 | 2 aa Del | 120-280 | Figure S7 | |

| TIGR01457 family HAD-type hydrolase | WP_046331702 | 1 aa Ins | 98-130 | Figure S8 | |

| C69 family dipeptidase *§ | WP_003647856 | 1 aa Del | 345-389 | Figure S9 | |

| YfbR-like 5’-deoxynucleotidase§ | WP_057718391 | 1 aa Ins | 23-79 | Figure S10 | |

| class I SAM-dependent methyltransferase | WP_003619061 | 1 aa Del | 269-326 | Figure S11 | |

| Phosphate acyltransferase PlsX§ | WP_011162257 | 1 aa Del | 176-227 | Figure S12 | |

| DNA helicase PcrA* § | WP_011162397 | 2 aa Ins | 248-301 | Figure S13 | |

| NADP-dependent phosphogluconate dehydrogenase *§ | WP_011162624 | 1 aa Del | 5-57 | Figure S14 | |

| calcium-translocating P-type ATPase§ | WP_044025971 | 1 aa Del | 814-864 | Figure S15 | |

| ATP-binding protein* § | WP_046332316 | 1 aa Ins | 347-399 | Figure S16 | |

| 16S rRNA (cytosine(1402)-N(4))-methyltransferase RsmH* § | WP_044496740 | 1 aa Ins | 76-113 | Figure S17 | |

| manganese-dependent inorganic pyrophosphatase* | WP_003579130 | 1 aa Ins | 9-59 |

Figure 3 Figure S18 |

Lacticaseibacillus |

| hemolysin family protein | WP_138426554 | 1 aa Ins | 345-382 | Figure S19 | |

| 1-acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase | WP_049169464 | 1 aa Del | 142-191 | Figure S20 | |

| DUF1002 domain-containing protein*§ | WP_049172803 | 1 aa Del | 85-129 | Figure S21 | |

| DeoR/GlpR family DNA-binding transcription regulator* | WP_191995078 | 1 aa Del | 85-128 | Figure S22 | |

| DNA polymerase IV | WP_138131441 | 1 aa Del | 110-155 | Figure S23 | |

| DNA polymerase IV* | WP_138131441 | 1 aa Del | 227-263 | Figure S24 | |

| YfcE family phosphodiesterase* | WP_129319710 | 1 aa Del | 1-36 | Figure S25 | |

| methionine adenosyltransferase | WP_138426285 | 1 aa Del | 58-102 | Figure S26 | |

| cyclopropane-fatty-acyl-phospholipid synthase family protein | WP_138741898 | 2 aa Ins | 315-362 |

Figure 4(B) Figure S27 |

Apilactobacillus |

| DEAD/DEAH box helicase | WP_053791914 | 1 aa Ins | 168-209 | Figure S28 | |

| Phosphate acetyltransferase* | WP_053791569 | 1 aa Del | 200-239 | Figure S29 | |

| glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase | WP_053796109 | 1 aa Ins | 12-48 | Figure S30 | |

| pyridoxal phosphate-dependent aminotransferase | WP_208215537 | 1 aa Ins | 30-65 |

Figure 4(D) Figure S31 |

Lactiplantibacillus |

| ABC transporter ATPase § | KLD61660 | 1 aa Del | 44-98 | Figure S32 | |

| acetyl-CoA carboxylase § | KLD60369 | 1 aa Ins | 32-83 | Figure S33 | |

| 50S ribosomal protein L15§ | WP_021337917 | 1 aa Del | 83-126 | Figure S34 | |

| C69 family dipeptidase | WP_134144186 | 2 aa Del | 289-325 | Figure S35 | |

| GRP family sugar transporter § | WP_222843328 | 1 aa Del | 83-128 | Figure S36 | |

| glycoside hydrolase family 13 protein* | WP_064619115 | 1 aa Del | 377-430 | Figure S37 | |

| undecaprenyl-phosphate alpha-N-acetylglucosaminyl 1-phosphate transferase § | OAX76783 | 1 aa Del | 158-208 | Figure S38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).