1. Introduction

Diabetes is defined as a complex chronic disease that occurs when the pancreas does not produce insulin (type 1 diabetes or T1D) or when the body is unable to use it effectively (type 2 diabetes or T2D), leading to a rise in blood glucose known as hyperglycemia [

1]. The prevalence and incidence of diabetes has become one of the main health problems worldwide [

2]. In 2014, a worldwide percentage of 8.5% of adults suffering from diabetes was reported, with T2D being the most prevalent form, covering 95% of the reported cases. In 2021 there were reported over 537 million cases of adults living with diabetes with the expectation to rise the number of cases to 643 million by 2020 and 783 million by 2045 [

1,

3,

4]. Currently, there are many options of treatment for T2D once diagnosed, with glycemic control being the main objective to achieve [

5]. Preferred therapies for the treatment of T2D include the use of antidiabetic drugs, lifestyle changes, and regular physical activity [

6]. Metformin is the initial and preferred antidiabetic drug for the treatment of T2D, due to its ability to lower glucose levels in tissues where there is resistance, weight control and a low risk of hypoglycemia. However, in a long term, the use of this drug can produce gastrointestinal intolerance (20-30%), and in some cases serious side effects such as lactic acidosis (5%), which prevents its use [

6,

7,

8,

9].

The development of nanotechnology has provided a great perspective to improve the treatment and diagnosis of diseases. Due to its increased surface area, the resulting nanomaterials have unique physical and chemical properties. The nanodrug delivery system is one of the applications of nanotechnology in the pharmaceutical area and has proved to delay the release of the drug, improving its solubility and availability, and thus, reducing its side effects [

10,

11]. Polymers have demonstrated to be very useful nanocarriers. They can be natural (albumin, gelatin, alginate, collagen, chitosan, and cyclodextrin) or synthetic (PLGA, polyethylene, PEG, polyanhydrides, and poly-I-lysine). Nanocarriers based on this type of polymers can deliver different types of compounds, which adhere to the polymer surface or are distributed in the polymer matrix [

10,

12].

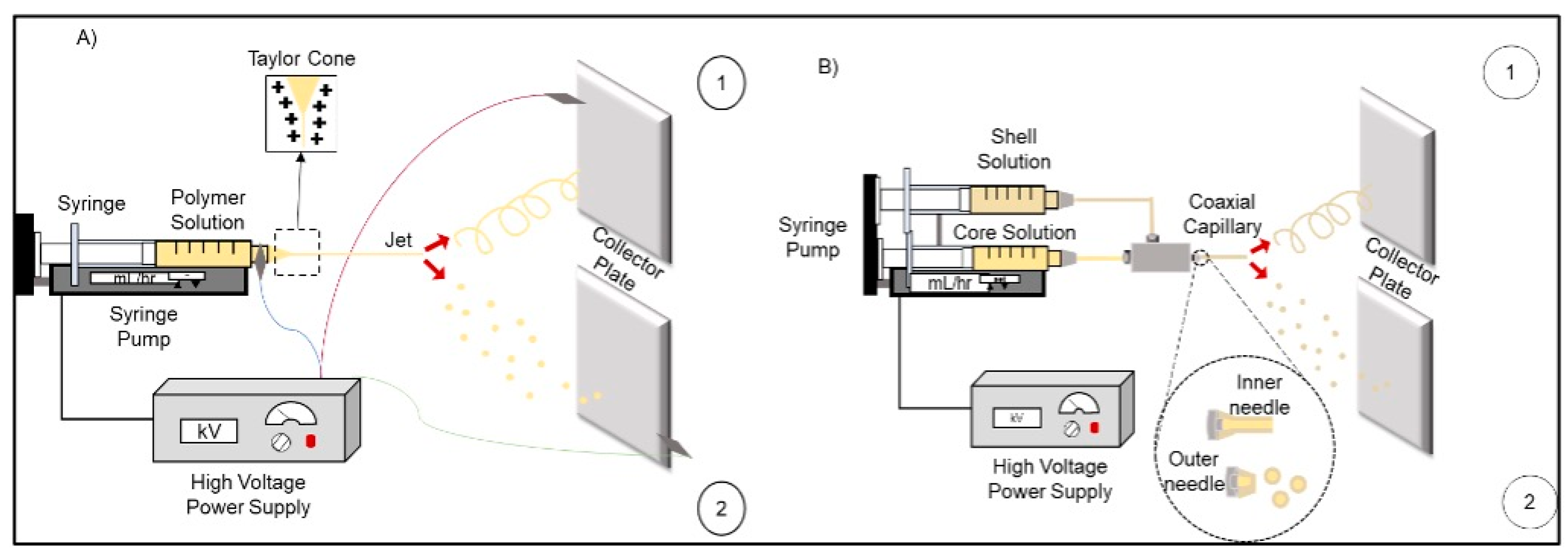

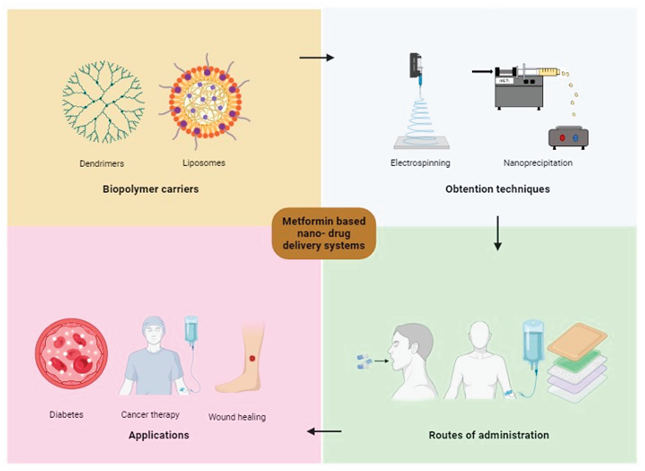

Various techniques have been studied to obtain this type of nanostructures; electrospinning/electrospraying is one of them. It is a technique that uses electrical energy to obtain products in the form of nanoscale materials [

13]. The control of the materials produced by this technique can be obtained through several parameters, among them are viscosity, surface tension, applied voltage, distance from the needle to the collector, fluid flow rate, humidity, and temperature [

14]. On the other hand, there is coaxial electrospinning/electrospraying, which is a technique that allows the manufacture of nanomaterials with a core-shell system. Compared to the conventional technique, one of the advantages of the coaxial system is that the nanomaterials are obtained using two separate solutions. This minimizes the contact between the organic solvents in which the polymer dissolves and the biological molecules encapsulated [

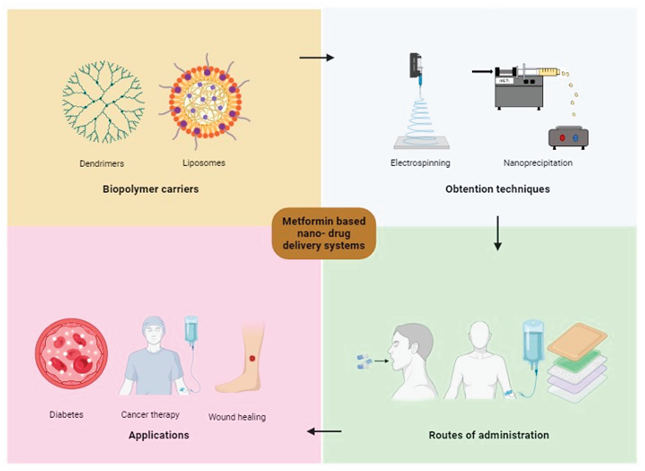

15]. Therefore, the application of nanotechnology in the release of drugs such as metformin is necessary, and in this way, manage to modulate its administration through a polymeric coating that provides a sustained and controlled release to reduce the adverse effects caused due to prolonged use. The primary objective of this review is to summarize and analyze the current advantages, and disadvantages of using nanotechnology to develop a metformin delivery system, highlighting the design, biopolymer carriers, obtention techniques and potential applications.

2. Methods

Comprehensive research of literature was conducted in several databases including PubMed, Science Direct, Scopus, Google Scholar to approach studies published between 2010 to 2024. We utilized a combination of keywords to address more specific and relevant studies. The terms included “metformin delivery system”, “biopolymer nanocarriers”, “electrospinning”, “polymeric nanoparticles” and “diabetes”, including their synonyms and its abbreviations. Additionally, we reviewed the current guidelines for diabetes, issued by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and World Health Organization (WHO), to include relevant evidence-based clinical suggestions.

3. Diabetes-Overview

3.1. Origin

Diabetes is a disease that takes place in ancient times through Egyptian man scripts dating back to 1500 BC. Also, around this time, Indian physicians developed what they could describe as the first clinical test for DM. They observed that the urine of people suffering from this disease attracted ants and flies, which is why they called the condition "madhumeha" (honey urine). Other aspects that can be observed is that people suffered from extreme thirst and bad breath (probably due to ketoacidosis). However, it was the Greek physician Aretaeus who set the term

Diabetes Mellitus, where diabetes denotes "go through" and mellitus is a Latin word that refers to "honey" or "sweetness" [

16]. Diabetes is a chronic disease that occurs when the pancreas does not produce enough insulin or when the body does not use the insulin it produces effectively, reducing the individual's ability to regulate the level of glucose in the bloodstream, resulting in hyperglycemia [

1].

3.2. Types of Diabetes

Diabetes is commonly a term used to address a group of diseases that cause prolonged hyperglycemia. However, the difference in the mechanism for developing the different types of diabetes is the basis for their classification [

6].

3.2.1.T1D

Also defined as autoimmune diabetes, it occurs due to pancreatic β-cell destruction leading to absolute insulin deficiency. About 5 to 10% of people who have diabetes, have this type [

17,

18,

19].

3.2.2. T2D

In this type, there is a progressive loss in pancreatic β-cell secretion, in which insulin resistance often coexists [

17,

18,

19].

3.2.3. Gestational Diabetes

It is a condition that occurs in women without a previous diagnosis of diabetes who have abnormal blood glucose levels in the second or third trimester of pregnancy. This is because in pregnancy, there is hyperplasia of pancreatic β-cells owing to stimulation of lactogen and prolactin, resulting in higher insulin levels [

19,

20].

3.3. Treatments

When starting treatment for any of the types of diabetes, several aspects must be considered:

- a)

Initially, control the metabolic alteration that occurs, which will allow the control of hyperglycemia

- b)

Maintain the nutritional status of the individual

- c)

Achieve good mental and physical health

- d)

Educate about the disease

3.3.1. T1D Treatment

For people with type 1 diabetes, it is mostly recommended to use regimens that simulate the physiology of insulin as much as possible, in any presentation [

21].

Insulin and Insulin Analogs

As a starting point for the treatment of T1D, endogenous insulin substitution with constant monitoring of capillary glucose and the carbohydrate count in the person's diet is implemented. As a complementary treatment to this, the placement of insulin injections or continuous infusion of cutaneous insulin is usually indicated [

21]. There are different types of insulin (prandial and basal) and forms of administration (pen, syringe, pump). Basal insulins include long- or intermediate-acting insulin analogs, and prandial insulins include rapid- or short-acting insulin analogs [

22,

23].

3.3.2. T2D Treatment

For T2D, the initial treatment is monotherapy, regularly with biguanide-type drugs. Biguanides reduce glucose production in the liver by decreasing gluconeogenesis and stimulating glycolysis and increase insulin signaling by increasing insulin receptor activity. Metformin is the drug of first choice for treatment. If monotherapy does not work, combination therapy is recommended, usually with sulfonylurea-type drugs and in some cases, insulin [

23,

24,

25].

3.3.3. Gestational Diabetes Treatment

Currently, the treatment for gestational diabetes is to eat a healthy diet and exercise as tolerated. The objective of this treatment is mainly focused on maintaining glucose levels and optimal maternal weight. If necessary, insulin is the preferred medication to treat the hyperglycemia in this type of diabetes [

23,

26].

3.4. Metformin

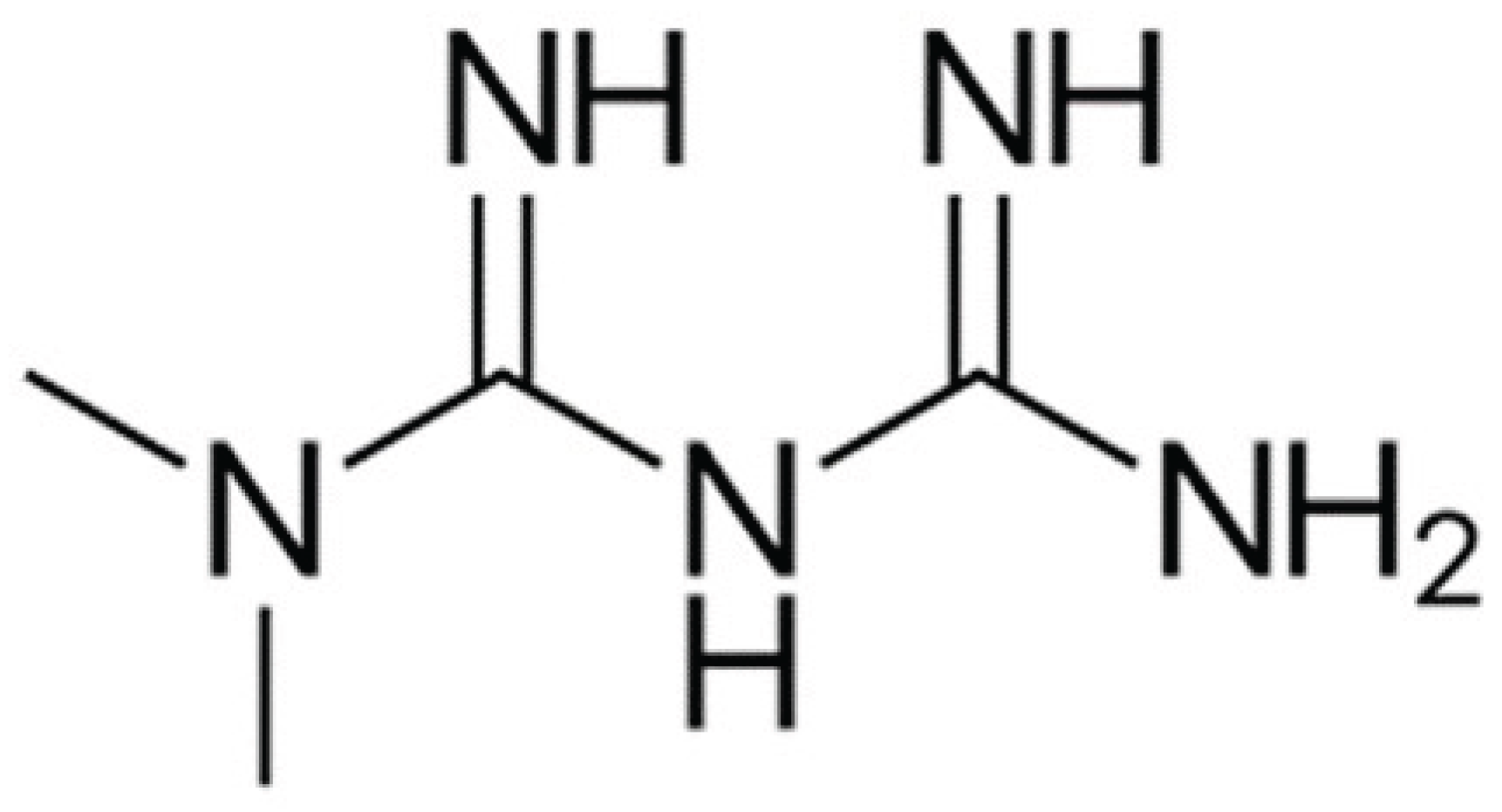

Metformin (

Figure 1) originates from a plant known as Galega officinalis; at the end of the 19th century, it was determined that this plant was rich in guanidine, which was shown to have a hypoglycemic effect and low toxicity [

27,

28]. Chemically, it identified as 1,1-dimethylbiguanide, has a molecular formula of C4H11N5 and a molecular weight of 129.16 g/mol. In regards to the solubility, it has been found to be 425.56 mg/mL (pH 4.6) and 348.27 mg/mL (pH 6.8) [

29]. Moreover, it has an oral bioavailability of 50-60% and, after intestinal absorption, enters the portal vein and accumulates in the liver.30 The recommended daily dose is 1-2 g/day, leading to plasma concentrations of 10-40 µM.31 It has been shown to be a safe and highly cost-effective drug that, unlike other antidiabetics, has no hypoglycemic side effects and has a favorable effect on body weight [

32]. According to several authors, of all antidiabetic drugs, metformin is the first-line treatment for T2D [

33].

Side Effects

The most common side effects of metformin are nausea, diarrhea, and abdominal discomfort (20-30% of people) [

34]. For this reason, it is recommended that it must be taken with a meal and the dose be adjusted gradually. Until now, the reason that causes the intolerance has not been explained exactly; however, some possible mechanisms that could be related are high concentrations of metformin in the gastrointestinal tract, increased serotonin in gastrointestinal cells, or the effect of metformin on intestinal flora, which can lead to unwanted infections [

35,

36].

Another effect, but less common (3 to 10 per 100,000 people), is lactic acidosis, which, according to this mechanism, metformin can increase plasma lactate levels by inhibiting its disposal [

37]. Although, it was originally thought that people with kidney disease could not take metformin due to the risk of causing this side effect [

35].

Likewise, the use of metformin may increase the risk of vitamin B12 deficiency (5.8-33%). Its mechanism is not yet clear, but it is believed that metformin interferes with calcium metabolism in the small intestine, which is essential in the uptake of the complex intrinsic factor - vitamin B12 by the receptor of the ileal cell. Consequently, delivery of vitamin B12 to the ileal cell is impaired, which could lead to vitamin B12 malabsorption [

23,

38].

4. Nanotechnology for Drug Delivery System

4.1. Advantages and Disadvantages

Currently, one of the challenges of most drug delivery systems is low bioavailability, stability, solubility, absorption, sustained delivery, therapeutic efficiency, and the presence of side effects [

39,

40]. Nanotechnology has been widely used in the application of nanostructures in various fields of science, precisely in drug delivery systems [

41]. These types of techniques have had an impact on the pharmaceutical industry by generating nanoparticles for a drug delivery system, because they can minimize drug degradation and loss, prevent side effects, and increase bioavailability and concentration at the required sites [

40,

42,

43,

44].

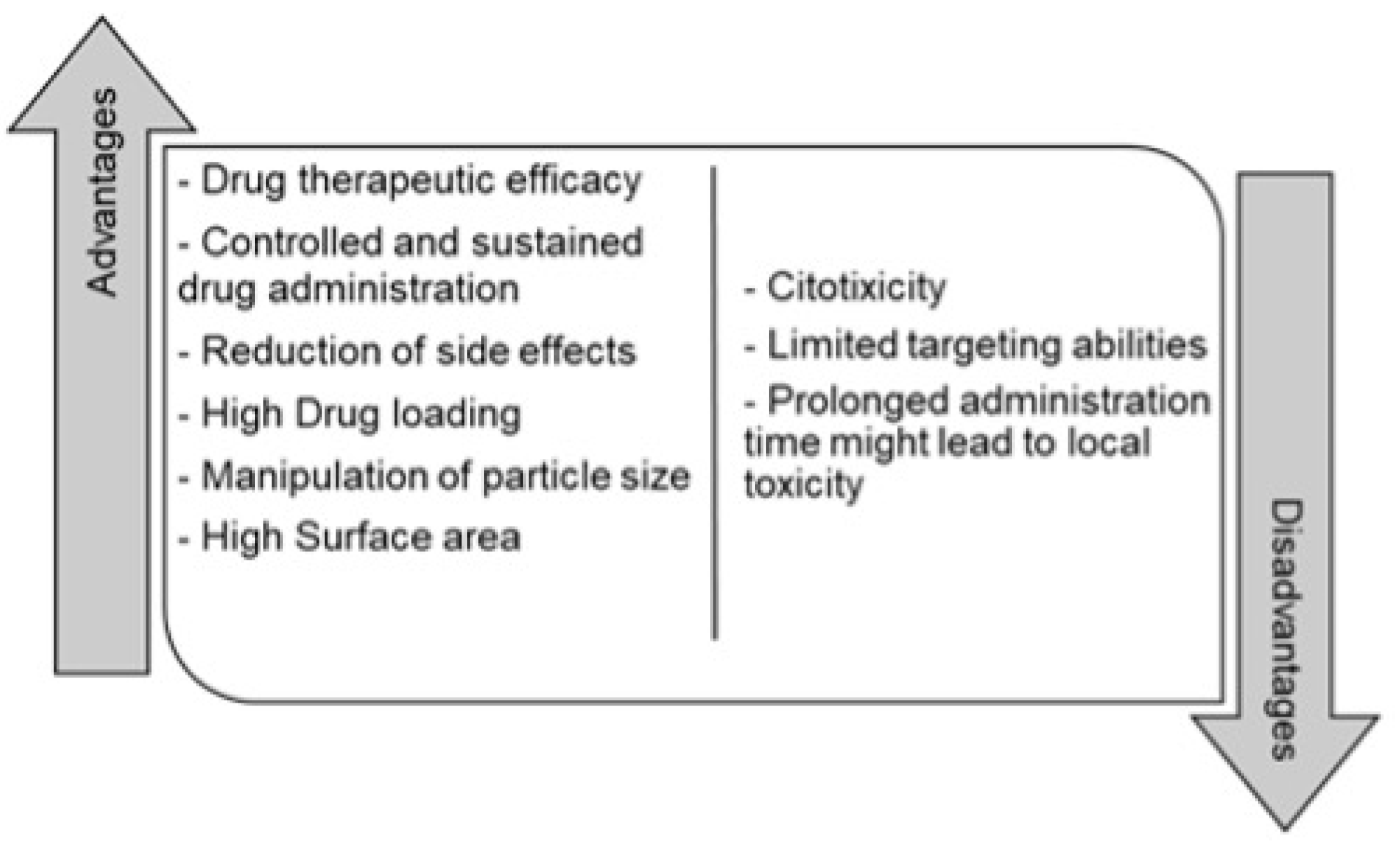

It might seem that nanoparticles could not have toxic effects. Nevertheless, having a large surface area of these particles can cause further chemical reaction resulting in the production of reactive oxygen species. These species are mechanisms of nanoparticle toxicity that can cause oxidative stress, inflammation, damage to proteins, cells, membranes and DNA, limited biocompatibility, and short action time [

40,

41,

46]. Some of the advantages and disadvantages are summarized in

Figure 2 [

11,

47].

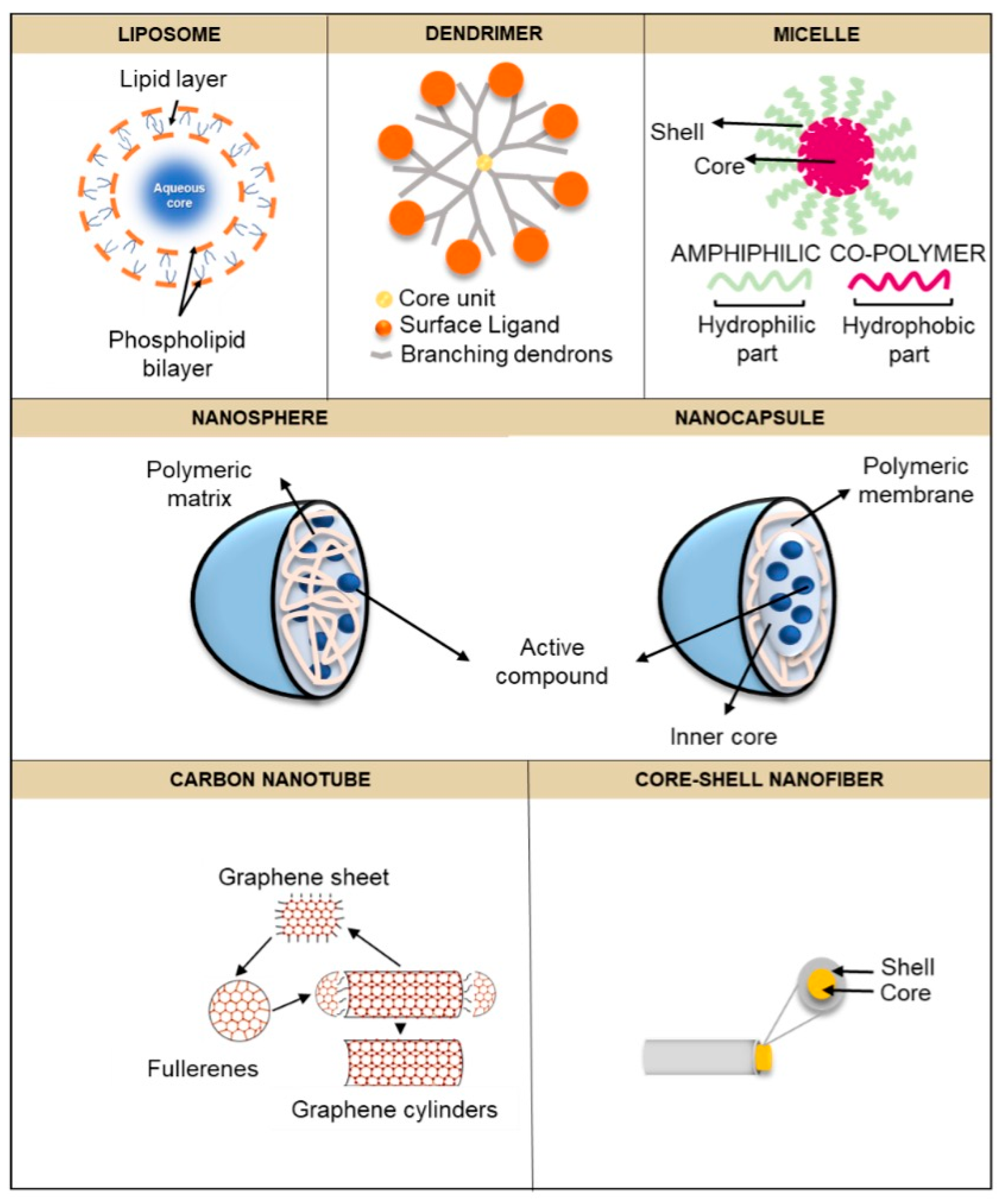

4.2. Nanostructures

In recent decades, various drug delivery systems have been developed and some are still under development. Polymeric nanoparticles, nanofibers, liposomes, micelles, dendrimers, and nanotubes are some of the materials recognized as drug delivery systems [

42,

48,

49]. In this section, some of the most widely used nanostructures in drug delivery are described in detail (

Figure 3).

4.2.1. Liposomes

Liposomes were among the first compounds investigated as drug carriers. These are spheres composed of a watery interior and a lipid double layer. Hydrophilic molecules can be incorporated into its structure; however, it is possible to encapsulate hydrophobic drugs within the phospholipid bilayer. In this way, liposomes can protect the drug, in addition to being useful for prolonging the release of active compounds that are poorly soluble in water [

4,

50]. These drugs can be loaded by passive or active techniques, such as sonication, micro-emulsification, membrane extrusion, etc [

51,

52].

4.2.2. Polymeric Nanoparticles

Polymers are molecules whose properties are ideal for applications in the pharmaceutical industry [

53]. Due to their nature, they are materials that offer the opportunity to modify and control the stability of a particle [

54,

55]. Polymeric nanoparticles are those particles whose size ranges from 1 to 1000 nm in length, and their shape is normally spherical [

53,

56,

57]. Depending on their structure, polymeric nanoparticles can be classified into two types: nanocapsules and nanospheres [

58].

Polymeric Nanocapsules

Polymeric nanocapsules are concave particles that have a core, either liquid or solid, which is surrounded by a polymeric membrane that allows it to be a suitable encapsulator for different compounds [

59,

60]. In the pharmaceutical industry, polymeric nanocapsules play an important role in drug delivery due to their core-shell structure. The polymeric membrane of which it is made gives it an advantage in the release of drugs by improving their stability, encapsulation, release, and distribution. On the other hand, the versatility of the core of being contained in different forms gives it the ability to encapsulate different types of drugs [

56,

60].

Polymeric Nanospheres

Polymeric nanospheres can be defined as matrix-type solid colloidal particles that, unlike polymeric nanocapsules, the active agent can be found either dissolved, trapped, encapsulated, or adsorbed in the polymeric matrix that constitutes the particle [

61].

4.2.3. Polymeric Micelles

Micelles are particles formed from lipids and certain amphiphilic molecules such as polymers [

62]. Polymeric micelles are characterized for having a spherical shape, a core-shell structure, and a diameter ranging from 10 to 100 nm [

62,

63,

64]. Its structure consists of self-assembled copolymers formed in a liquid medium, whose core (hydrophobic part) is surrounded by a crown composed of hydrophilic molecules, which bind to the aqueous medium and gives rise to its classic spherical structure.65-66 The advantage of this type of nanostructure in drug release is the ability of the core to solubilize drugs that are poorly soluble in water, while the crown provides a location for those compounds that are hydrophilic [

66,

67].

4.2.4. Nanofibers

Nanofibers refer to those fibers whose diameter ranges from 100 to 1000 nm.68 They have various characteristics such as a large surface area, flexibility, and tensile strength; same properties that have allowed the application of nanofibers in different areas (drug delivery, biosensor, wound dressing) [

69]. Its structure is based on the composition of an internal fiber called the core, which, in turn, is surrounded by an external layer known as the shell [

70].

4.2.5. Carbon Nanotubes

Carbon nanotubes are hollow and ordered carbon graphite nanostructures, whose properties allow them to be exposed to adsorb with a wide variety of therapeutic materials such as bioactive proteins, peptides and drugs owed to their high surface area, high electrical conductivity and remarkable tensile strength, thermal conductivity, and the ability to be chemically modified [

71]. The diameter of the nanotubes ranges from 1-100 nm and they are typically capped with half a fullerene molecule at the ends [

72].

4.2.6. Dendrimers

Dendrimers are composed of three regions: core, layers of branched repeat units emerging from the core, and a surface. Owing to their composition of repeating branched units, dendrimers could provide a large surface area and thus, drugs can be added to dendrimers by encapsulation. Hydrophobic drugs can be encapsulated in the hydrophobic core, and hydrophilic drugs can be attached to dendrimer surfaces via covalent or electrostatic interaction [

73].

5. Biopolymer Carriers for Metformin Release System

Currently, in the pharmaceutical industry, interest has arisen in improving drug delivery systems so that they offer more versatile therapeutic options for the treatment of diseases, including metformin [

74]. One of the improvements that has generated interest within the industry is the use of molecules or polymers, in order to generate a nanocoating for the particles or drugs and in this way, these resist the passage through the gastrointestinal tract and their release is even more prolonged [

75]. Polymers are considered ideal materials for drug encapsulation as they are biodegradable and biocompatible, which are properties that allow the drug to withstand changes in pH, temperature, surface modification and conjugation [

76]. The main polymers that have been used for the encapsulation of metformin are summarized in

Table 1.

5.1. Protein - Based Nanocarriers

In recent years, proteins have been widely used as a material for obtaining nanostructures, especially in pharmaceuticals [

77]. Due to their well-defined primary structure, water solubility, biodegradability, low toxicity, and bioavailability, they facilitate drug incorporation significantly. In addition, many of them are recognized as safe (GRAS) and have a pharmaceutical excipient. Specifically, plant-based proteins offer a “green” label as obtained from renewable resources [

78]. Animal-derived proteins such as keratin, collagen, gelatin, elastin, serum albumin, have been widely used in various pharmaceutical applications with controlled release behavior, degradation and mucoadhesive in nature. Likewise, proteins of plant origin such as zein, soy and gliadin, have been shown to be a good vehicle for drug administration as they have a good interaction with the biological environment, absorption, and retention [

79]. There are different protein-based delivery systems that vary in shape and size, such as microspheres, nanoparticles, hydrogels, films and minirods; structures whose obtaining is through simple low-cost processes [

78].

5.1.1. Gelatin

Gelatin is a natural polymer soluble in water whose production is given by the hydrolysis of collagen in alkaline or acid media or by thermal or enzymatic degradation of collagen. Its size varies from 20 to 220 kDa and its solubility in water is above 35 to 40°C. Commercially, there are two types of gelatins (A and B) based on the method of collagen hydrolysis. Type A (cationic) gelatin is derived from the partial acid hydrolysis of pig skin collagen, while type B (anionic) gelatin is obtained from the hydrolysis of bovine collagen. Gelatin is composed of hydrophobic, cationic, and anionic groups, and a three-helix structure with glycine, proline, and alanine sequences; which allow the high stability of gelatin [

77]. As a biomaterial, it has been widely applied in drug delivery as it possesses various properties such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, and non-toxicity [

80].

In 2019, Shehata and colleagues formulated metformin nanoparticles composed of gelatin/sodium alginate by electrospray technique. Moreover, the material obtained was evaluated physic-chemically and the antidiabetic effect was estimated by means of in vivo tests. The results showed that the electrosprayed nanoparticles were spherical with minimal folding, indicating that the viscosities corresponding to the gelatin and sodium alginate solutions were the optimal ones for spray drying and, therefore, inhibit folding or wrinkling of the surface. The entrapment efficiency of metformin nanoparticles was greater than 90% in all formulations. Regarding the in vitro release of the prepared metformin nanoparticles, they showed a drug release of 50% after 6 hours and 84% after 24 hours, and a significant reduction in blood glucose levels at 6, 8, 12 and 24 hours. This is due to the mechanical stability of the gelatin/sodium alginate nanoparticles, which controlled the release of the drug for longer periods in wide pH ranges (1.2 to 8) which encompass the conditions of the gastrointestinal tract [

81]. Another study made in 2020 by Cam and colleagues developed a drug-eluting diabetic wound healing dressing. Metformin-loaded bacterial gelatin/cellulose nanofibers were obtained from the electrospinning method. The results reported nanofibers with a smooth surface and without crystals of metformin present on the surface. The estimated encapsulation efficiency for the gelatin/bacterial cellulose/metformin nanofibers was approximately 80%. Concerning the in vitro release of metformin, it followed an almost linear profile and a sustained release, reaching a maximum peak on day 15 with 0.0197 mg. On the other hand, in vivo tests were carried out for 14 days to assess diabetic wound healing; and, it was shown to have significantly accelerated healing, the effect of which began from day 3 to day 14 [

82].

5.1.2. Bovine Serum Albumin

Bovine serum albumin (BSA), also called plasma carrier protein, is a protein found in milk whey and is made up of 583 amino acid residues with a molecular mass of approximately 66.5 kDa [

78,

83]. It is widely used in the pharmaceutical industry due to its high affinity, which is suitable for both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs. Additionally, its use reduces the toxicity of the drug and increases its efficacy [

84].

In 2020, Lu and colleagues prepared metformin-loaded bovine serum albumin (BSA) nanoparticles by the nanoprecipitation method to improve dissolution; Moreover, the therapeutic efficacy of the material obtained was tested using an insulin-resistant liver cancer cell line. The reported results were spherical, non-porous metformin-loaded BSA nanoparticles with an approximate particle size of 200 nm. Furthermore, in a 48-hour study, the charged nanoparticles were shown to have greater anticancer activity in vitro than pure metformin in insulin-resistant liver cancer cell lines [

83].

5.1.3. Casein

Casein is the main protein in milk. It is a conglomerate of four proteins (α-casein, β-casein, and K-casein), whose molecular weights are approximately 24 kDa; however, they differ in their amino acid content and interactions with hydrophobic and hydrophilic substances [

85]. It is a protein widely used in drug administration due to its structural and physicochemical properties such as emulsifying, ion binding, stabilizing, self-assembling, gelling and water retention [

86]. In addition, it is a cost-effective, bioavailable, non-toxic, and biodegradable material, which makes it a promising protein in the encapsulation of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic drugs for sustained and controlled drug release [

87].

Raj and collaborators evaluated the phenomenon of entrapment of metformin in casein micelles in 2015, as well as the sustained release of the drug. As a result, fine, stable metformin-loaded casein micelles with a particle size of 963.4 nm were obtained. The encapsulation efficiency of metformin in casein micelles was 87.42%. According to the vitro release test, an initial rapid release was observed due to the desorption and diffusion of metformin from the surface of the micelles, which is optimal to reach a threshold dose that induces an adequate therapeutic action. Following the initial rapid release, the casein-metformin micelles exhibited sustained and slow release; which, remained constant after 15 hours where the maximum release of the drug was obtained [

87].

5.2. Polysaccharide - Based Nanocarriers

Polysaccharides are macromolecules that are made up of several monosaccharide units. They are cheap, abundant, and renewable materials, which have been used in various fields due to their biological and chemical properties such as biocompatibility, polyfunctionality, biodegradability, hydrophilicity, and non-toxicity. Hence, its use can be helpful for the encapsulation, immobilization and controlled and sustained release of different active compounds, which are used in the pharmaceutical, food, biomedical and chemical industries [

88]. Therefore, they are considered as ideal materials for the transport of drugs, since they have been shown to increase their solubility and permeability. Some of the most used polysaccharides for drug encapsulation are pectin, hyaluronic acid, chitosan, dextran, alginate, starch, among others [

89].

5.2.1. Chitosan

Chitosan is a cationic polysaccharide and one of the biopolymers with the highest biological activity and is obtained from chitin, which is found in exoskeletons of arthropods and in the cell walls of fungi [

87,

90]. Its chemical structure is based on a chain of glucosamine and N-acetyl-glucosamine with β-(1-4) linkages. Among its main properties, its biocompatibility, biodegradability, gelation, high solubility at low pH and non-toxicity stands out; which makes it an optimal candidate for pharmaceutical applications. In addition, it is a polysaccharide with mucoadhesive properties, which allow them to electrostatically interact with mucous membranes or negatively charged mucosal surfaces and thus generate systems for oral administration [

89,

91]. Due to its ability to form ionic crosslinks, it allows it to release the drug in a prolonged manner, thus giving it a controlled release of it [

92].

In 2021, Wang and colleagues synthesized metformin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles by the ionic gelation method to evaluate the effect of these as an oral delivery platform for polycystic kidney disease. They also evaluated the effect of these nanoparticles in relation to their particle size, loading efficiency and degradation at different pH present in the gastrointestinal tract. The authors reported chitosan nanoparticles with a mean diameter of 150 nm, which showed greater mucoadhesive efficiency. The loading efficiency of metformin in the chitosan nanoparticles was 32.2%; the authors explain that this is due to electrostatic interactions of metformin with the crosslinker during nanoparticle synthesis. Likewise, in the evaluation of the degradation at different pH, the chitosan nanoparticles proved to have a certain stabilizing and protective effect at low pH and release the drug when reaching neutral pH, like those of the small intestine [

93].

A previous study designed a metformin drug delivery system in which chitosan was modified with phthalic anhydride followed by 4-cyano, 4-[(phenylcarbothioyl)sulfanyl] pentanoic acid to generate a macro-RAFT agent. This was followed by copolymerization with AAm and then AA monomers via RAFT polymerization to produce CS-g-(PAAM-b-PAA) terpolymer. Subsequently, it was loaded with metformin and its release was evaluated. The results showed metformin-loaded CS-g-(PAAM-b-PAA) nanoparticles with a mean diameter of 80 nm. Regarding drug release, the nanoparticles obtained exhibited a sustained release pattern after 5 hours; that is, due to the strong interactions generated between the functional groups of metformin and the terpolymer [

94].

5.2.2. Pectin

Pectin is a linear heteropolysaccharide mostly found in the cell wall of plants. It is made up of D-galacturonic acid units linked by α-(1-4) glycosidic bonds and its molecular weight varies between 50 to 150 kDa. It is a polysaccharide that contains hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, esterified residues with methyl ether distributed in its linear chain and some sugars present in its side chain. In the presence of their ionized carboxyl groups, these interact with their positively charged anions forming hydrogels; same reason why it is an anionic, biocompatible, biodegradable polysaccharide with mucoadhesive properties in drug administration [

89,

95]. Additionally, pectin is known to be non-toxic and undigested in the upper gastrointestinal tract by gastric enzymes [

96].

In a study conducted by Chinnaiyain and collaborators in 2018, the combined effect of pectin and metformin in nanoformulations with possible therapeutic effects in diabetes was determined. Metformin-loaded pectin nanoparticles were obtained from the ionic gelation method using tripolyphosphate as crosslinker, with a spherical shape and a mean diameter of 482.7 nm. The nanoparticles showed a significant encapsulation efficiency of 86.74%, which could be related to the electrophilicity of the tripolyphosphate cations that induce a faster electrostatic interaction than the biopolymer carboxylates, thus generating a thicker layer and avoiding the immediate release of drugs and, in addition, the diameter of the nanoparticles provided a greater entrapment of metformin. Regarding the in vitro release of metformin, the results showed a slow release with a total release after 12 hours in a range of 74.37 to 98.5%. It was noted that, by increasing the concentration of pectin, the release was diminished; the authors justify this phenomenon by the increase in viscosity, which produces a greater ionic interaction and greater retention of the drug and, therefore, less diffusion of it through the matrix [

95].

5.2.3. Cellulose

Cellulose is a linear homopolymer that is composed of repeating units of D-glucoses β-(1-4). It is a polysaccharide that originates mainly from the cell walls of plants [

87]. It is a highly documented biopolymer for being biodegradable, bioavailable, biocompatible, non-toxic, and generally recognized as safe (GRAS) by the FDA. Its excellent chemical, physical and mechanical properties in the pharmaceutical industry, makes it an appropriate material to encapsulate and transport drugs [

96]. However, there are certain disadvantages such as poor wrinkle resistance, undesirable solubility in common organic solvents, and poor thermoplasticity; therefore, various chemical or physical modifications have been made to cellulose to improve its properties [

97]. Cellulose acetate (CA) and carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) are cellulose derivatives widely used for the incorporation of particles in order to obtain materials with improved physicochemical and biological properties [

98].

In a study done by Cam and collaborators [

82] they obtained bacterial cellulose nanofibers loaded with metformin and were cross-linked with glutaraldehyde vapor using the portable electrospinning technique, with application in diabetic wounds. The obtained nanofibers were characterized and the results showed fibers with smooth surfaces without metformin crystals present in the surface with an average diameter of 0.22 µm. Likewise, the metformin encapsulation efficiency was calculated, which was approximately 80% and its release followed a linear pattern, demonstrating a sustained release.

In a previous study, cellulose acetate was used as a matrix to obtain coaxial nanofibers loaded with metformin for sustained release, using the triaxial electrospinning method. The manufactured coaxial nanofibers were characterized and according to the results obtained, nanofibers with a mean diameter of 570 nm with a smooth morphology without defects were obtained. Regarding the drug encapsulation efficiency, values of 98.41% were obtained with almost no drug loss during the electrospinning process. In vitro release of the nanofibers demonstrated zero order release with 95% release of metformin; the authors attribute this to the nanostructure of the material obtained and the heterogeneous distribution of metformin in the core and shell sections [

99].

5.3. Lipid - Based Nanocarriers

Liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles and nanoemulsifiers are some of the terms used to refer to lipid-based drug delivery systems, with sizes ranging from 100 to 500 nm [

100]. Lipids offer a variety of physicochemical properties such as biocompatibility, low susceptibility to erosion and slow water absorption, which is why they are ideal candidates to be a nanocarrier system for drugs by improving their solubility and bioavailability [

101]. Most of the fats and oils used for the development of these nanostructures are derived from the diet, thus facilitating oral permeability and biodegradability. In addition, they are systems that can be designed to specifically interact with cells of the gastrointestinal tract, which effectively increases drug delivery [

102,

103].

5.3.1. Lecithin

Lecithin can refer to various phospholipids, glycolipids, and triglycerides. Specifically, it is pure phosphatidylcholine which is a phospholipid that comes from the phosphate extracted from vegetables such as rapeseed, rice, or soybeans. Speaking of liposomal matrices, lecithin that comes from sources such as soy has certain disadvantages. This is due to the content of fatty acids in its structure; however, the lipids derived from bovines have little stability due to their high content of polyunsaturated fatty acids, unlike the lipids in soybeans, which contain less of this type of fatty acids. Nevertheless, lecithin extracted from soybeans is used mostly in industries such as pharmaceuticals, in addition to the fact that its production is cheaper, safer, and more stable [

104].

Abd-Rabou [

105] and colleagues studied the effect of lecithin and chitosan on metformin encapsulation and its potential application in the inhibition of colorectal cancer proliferation. The results showed the obtaining of lecithin and chitosan nanoparticles loaded with metformin with an average particle size of 31.5 nm and an encapsulation efficiency of 95.2%. Regarding the in vitro release study, about 24.3% of the encapsulated metformin was released at 2 hours and its total release (100%) was reached at 24 hours. Likewise, it was shown that when adding the two polymers (lecithin and chitosan), the release was slower, possibly due to metformin remained saturated and wrapped in the polymer chains and thus, the formation of the nanoparticle.

5.3.2. Glycerol Monostearate (GMS)

Glyceryl monostearate (GMS) is an amphiphilic monostearyl ester composed of a single glycerol chain, a long alkyl chain, and two oxygens. It has emulsifying and emollient properties, it is easy to digest and non-toxic, which makes it of great importance in applications in industries such as food, cosmetics, and pharmaceuticals [

106].

Ngwuluka and collaborators [

107] designed and characterized metformin-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles using glyceryl monostearate and lecithin by the double emulsification method. The results demonstrated lipid nanoparticles with an average size of 195 nm and an encapsulation efficiency of 29.30%. Although, metformin is a highly soluble drug and its permeability is a factor that limits its absorption; that is why the development of lipid nanoparticles was suggested, which improved its absorption. However, its solubility affected its encapsulation efficiency. The in vitro release studies showed that, even though an encapsulation of 29.30% of metformin was obtained, its release remained controlled; in such a way that at 30 min, 48% of the drug was released and after 8 hours, almost 100% had been released.

5.4. Nanocomposites - Based Nanocarriers

Composites are a combination of two different materials or phases, one called reinforcement (fiber, sheet, or particle), which is assembled in another phase called matrix (metal, ceramic or polymer). Consequently, nanocomposites are structures in which at least one of the phases that composes it, is found on a nanometric scale [

108]. Among the various types of nanocomposites, biopolymeric nanocomposites have been of great interest in drug administration since the reduction of nanoparticles to the polymeric matrix decreases drug release, improves its stability, and achieves controlled and sustained drug release; this will depend on the properties of the nanocomposites, such as their concentration, size, shape, and the interaction between the nanomaterials and the polymeric matrix [

109,

110].

In 2017 Shariatinia & Zahraee developed films based on chitosan nanocomposites with poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(propylene glycol) blocks, which contained mesoporous nanoparticles of MCM-41 and metformin, and glycerin was added as a plasticizer to a control in the release of metformin. Morphologically, the authors reported that, by including the drug, films with a very rough surface with a particle size of approximately 50 nm were acquired. According to the in vitro study carried out by the authors, it was shown that the release of metformin had a considerable increase within the first 24 hours showing a burst release and then, gradually and in a sustained manner, a release of 45% was obtained after 15 days [

111].

5.5. Synthetic Polymers – Based Nanocarriers

The use of synthetic polymers as drug nanocarriers has been highlighted, specifically for the possibility of developing drug delivery systems with sustained and controlled release. In addition, they offer unique properties such as biocompatibility, biodegradability, low toxicity, stability in blood flow, and protection against early drug degradation before reaching the target tissue, which, unlike natural polymers, have higher purity and reproducibility [

112,

113]. Among the synthetic polymers most widely used in pharmaceuticals are poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA), poly(lactide) (PLA), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and polyethylene glycol (PEG).

5.5.1. Poly(lactide) (PLA)

Polylactic acid (PLA) is a thermoplastic derived from natural sources such as starch and can be synthesized from lactic acid by polycondensation or polymerization. It is widely used in drug delivery systems due to its properties such as its natural origin, its biocompatibility, biodegradability, among others [

114,

115].

Sena et al [

116] developed nanofibers with a core-shell system using PLA as the shell and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) together with fish sarcoplasmic protein (FSP) and metformin as the core, using the coaxial electrospinning technique. This, to evaluate the influence of FSP on the morphology and examine the release properties of metformin through a coaxial nanofiber system. Morphologically, nanofibers with a smooth surface without drug residues and mean diameters of approximately 650 nm to 681 nm were obtained. Regarding the release of metformin, the nanofibers showed an initial release of metformin of approximately 59% in the first 24 hours. Following this, the release was slow and sustained, and after 21 days about 96% of metformin was released from the nanofibers.

5.5.2. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic Acid) (PLGA)

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) is a natural copolymer comprising two different blocks, PLA and poly(glycolic acid) (PGA), which give it special properties such as adjustable crystallinity, hydrophilic/hydrophobic balance, biodegradability and approved safety by the FDA. PGA is highly crystalline and hydrophilic, and PLA hydrophobic [

115,

117]. Its biodegradability is given by the number of glycolide units present in its structure and, in this sense, it is possible to design drug release systems in a controlled and programmed manner [

118].

In a previous study PLGA nanoparticles with PEG were obtained for the co-release of metformin and silibinin to evaluate their antitumor effect. The obtained nanoparticles showed a spherical morphology with a uniform distribution, a particle size of approximately 246 nm and an encapsulation efficiency of 75.15% for metformin. For the co-release of metformin and silibinin, both drugs had an initial burst release in the first 8 hours and then a sustained release for 7 days, with about 87% being released after 3 days [

119].

6. Techniques

6.1. Electrospraying

Electrospray, also known as electrohydrodynamic atomization (EHDA), is a technique used to produce particles with submicron sizes [

124]. Like electrospinning, electrospray consists of a high-voltage source, a plastic syringe with a metal needle, an injection pump, and a collector plate (

Figure 4A2). Electrospray is based on the applying of an electric field to the metal capillary, a charged jet will break into droplets that form particles. This is when the electrostatic force of the drop overcomes its cohesive force, the surface tension is broken, thus obtaining the formation of particles [

130,

131,

132,

133].

6.1.1. Coaxial Electrospraying

Coaxial electrospray is one of the many configurations of conventional electrospray and is mainly used to obtain core-shell systems [

134].

Figure 4B2 shows the basic configuration of the electrospray process in which a coaxial capillary is used to separate the two polymeric solutions and thus be sprayed at the same time until they solidify by evaporation of the solvent and obtain particles with a stable core-shell system [

135,

136]. Encapsulation in this system can be achieved in two ways: On the one hand, the first solution contains the polymer, while the second contains the component to be encapsulated. On the other hand, a solution can be obtained with a mixture of the polymer and the component to be encapsulated, and in the second solution only the polymer [

132].

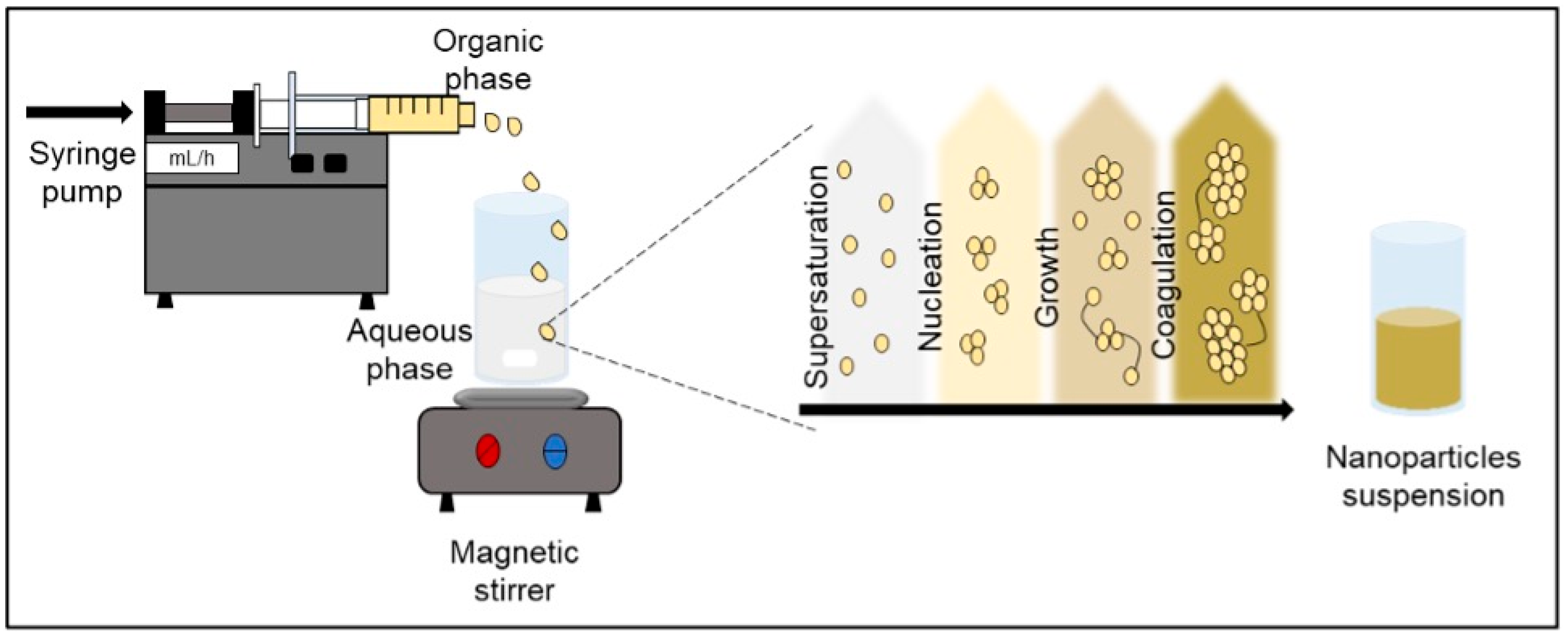

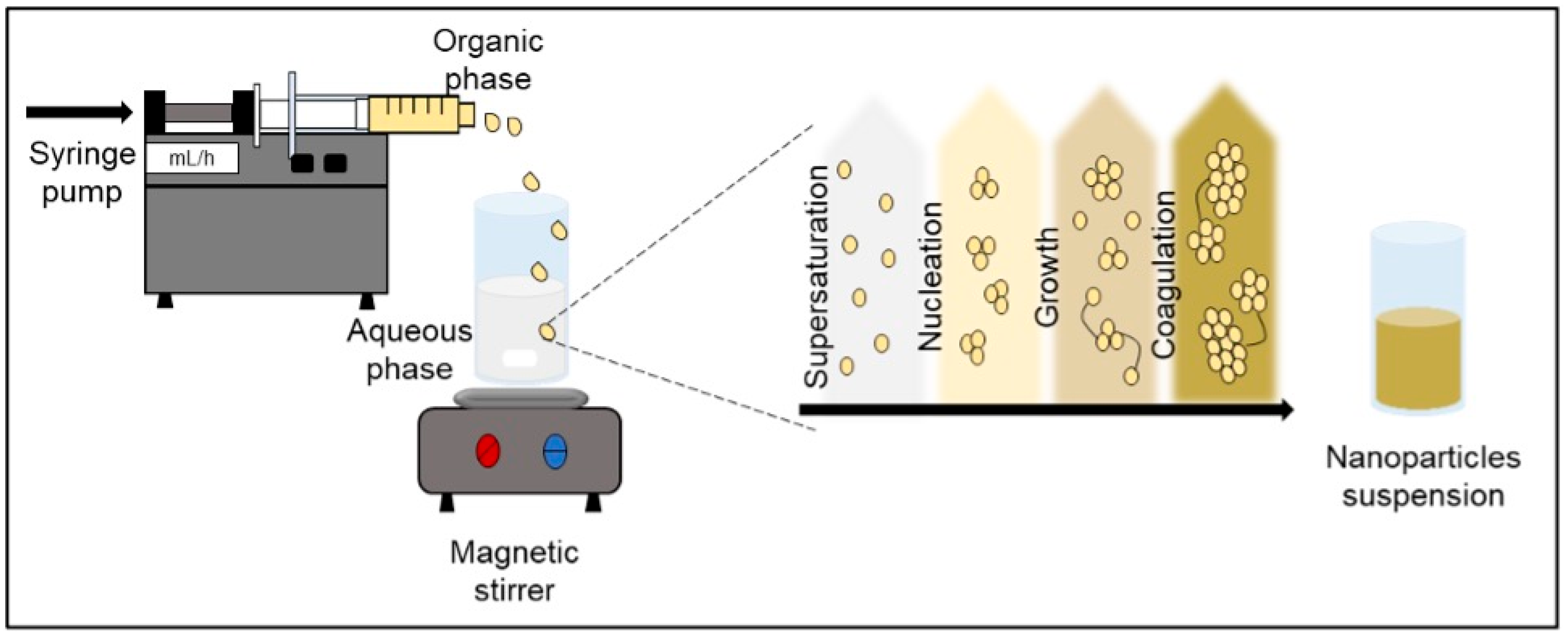

6.1.2. Antisolvent-Precipitation

Also known as nanoprecipitation or solvent displacement, it was initially developed by Fessi in 1989. It is a technique used for the encapsulation of molecules in different types of structures (nanospheres or nanocapsules) and is considered one of the simplest methods for the preparation of polymeric nanoparticles ranging from 50 to 300 nm in size [

137,

138]. As shown in

Figure 5, this method requires the preparation of two phases: organic phase (solvent) and aqueous phase (non-solvent); the solvent phase is made up of the active compound, the polymer, and the solvent, in which they dissolve. On the other hand, the non-solvent phase is made up of one or more hydrophilic biopolymers (usually water), thus forming a solute/solvent/water ternary system [

139,

140]. The nanoprecipitation process is carried out when a solute (polymer) dissolves in a solvent (ethanol, acetone) which, when mixed with water, turns the medium into a non-solvent for the solute; this supersaturation leads to the precipitation of the polymer. Besides, in the search for stability, the polymer particles associate and form nucleation, which increase in size due to the association of solute molecules and this leads to the formation of nanoparticles in a rapid, controllable, and reproducible manner (coagulation) [

141,

142,

143]. In some cases, the use of surfactants is necessary for the formation of nanoparticles; however, under certain conditions, nanoparticles are formed without the need for a surfactant due to the rapid displace mechanism of the solvent by water, better known as the "ouzo effect" [

137,

140,

144,

145].

6.1.3. Flash Nanoprecipitation

Fast nanoprecipitation is a method used to create high supersaturation conditions that lead to the precipitation and encapsulation of hydrophobic agents [

140]. The technique basically consists of a hydrophobic molecule and an amphiphilic block copolymer being dissolved in an organic solvent that is miscible with water and thus creating a high supersaturation. Such supersaturation promotes the coprecipitation of the hydrophobic molecule and the hydrophobic block copolymer to form nanoparticles [

146,

147]. The fast nanoprecipitation design is based on the use of a syringe pump which drives two liquid streams in opposite directions and at high speed, until they meet in the mixing chamber or better known as a confined impact jet mixer (CIJ) (

Figure 6A) [

140,

146].

6.1.4. Two–Step Nanoprecipitation

In nanoprecipitation, it is normally difficult to find a suitable solvent capable of dissolving both the active compound (hydrophobic) and the protein (hydrophilic), and that does not cause a loss in its function and structure [

137,

148]. Morales-Cruz and colleagues [

149] introduced two-step nanoprecipitation in 2012 and describes it as an alternative technique to the conventional method, which was used with the objective of facilitating the selection of a common solvent for the active compound and the polymer without causing any change in the polymer. As illustrated in

Figure 6B, the first step in this novel method initially consists of organic solvent-induced nanoprecipitation of the active compound, generating a suspension. Following this, the organic solvent is used to dissolve the polymer and thus add it to the suspension with constant stirring until a second nanoprecipitation is obtained and finally, the encapsulation of the active compound [

148].

7. Methods of Administration of Metformin Delivery Systems

7.1. Oral Administration

The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is the best-known way to administer drugs, since it has the advantage of offering a large area for systemic absorption. The challenge in the administration of drugs (especially orally) is to achieve stability when passing through the stomach, the intestinal lumen, the intestinal epithelial mucosa, and the epithelium itself [

119]. Metformin is a hydrophilic molecule with high solubility (50mg/mL) and poor oral absorption due to its limited saturated and poor intestinal absorption; That is why recent studies have designed various metformin delivery systems to obtain better oral absorption and a more controlled release of the drug [74-150].

A previous study developed nanoparticles from chitosan with the aim of improving the oral bioavailability of metformin and, in turn, the capacity for mucoadhesion and permeation through an in vitro intestinal barrier model. Metformin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles demonstrated higher mucoadhesion efficiency at a particle size <200 nm, with a stable morphology and drug protection capacity under acidic pH conditions found in the stomach; but upon reaching a neutral pH such as that of the small intestine and systemic circulation, they swell and release the drug [

93]. Another similar study carried out by Bhujbal & Dash150, in which hyaluronic acid nanoparticles loaded with metformin were synthesized by the nanoprecipitation method, in order to evaluate the mucoadhesive capacity of the polymer. Physically stable nanoparticles with a particle size of approximately 114 nm, release of metformin >50% in 1 hour and low permeability through the intestinal membrane were obtained, thus maintaining a sustained release of metformin.

[

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140,

141,

142,

143,

144,

145,

146,

147,

148,

149,

150]

7.2. Cutaneous Administration

The skin is the largest organ in our body, covering an area of 1.8-2.0 m

2. It is composed of 3 layers: epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis. The stratum corneum is the outermost layer of the epidermis and is mainly composed of keratonocytes, which provide it with the barrier property of the skin [

151]. Cutaneous administration of drugs has been proposed as an alternative to common routes such as oral and parenteral, because the skin is considered an accessible organ and does not cause pain. The main objective of this administration route is to overcome the stratum corneum barrier. The benefits that this route offers are a longer duration and a constant rhythm in its administration, it can be interrupted simply by removing the device and gastrointestinal incompatibility can be avoided. There are several uses for the administration of dermal drugs, among them are the treatment of burns, ulcers, wounds, inflammations, or skin diseases that require a specific drug and is released by percutaneous penetration. However, there are two routes for drug administration: dermal and transdermal administration. In the first, the drug crosses the outer layer of the skin and the second requires the drug to be transported to the dermis of the skin through transepidermal (inter and intracellular) transappendicular (transfollicular and transudoripar) routes [

152].

Recent research such as that of Migdadi and collaborators [

153] they studied the potential of a patch of hydrogel-forming microneedles for the administration of metformin transdermally and sustained, in order to minimize gastrointestinal side effects and variations present at the time of absorption in the small intestine associated with oral administration.

Regarding the mechanism of action of hydrogels, when they are inserted into the skin, they are in contact with the interstitial fluid. Hydrogels swell and create porous, aqueous channels through which the drug diffuses and reaches the dermal circulation. Moreover, the aqueous network formed by hydrogels has been reported as a suitable mechanism for the transdermal administration of drugs, with a high degree of solubility in water, such as metformin. For the purposes of the study, the permeation of metformin through porcine skin through hydrogel-forming microneedle patches was evaluated. According to the results, a transdermal bioavailability of metformin of 0.3 was obtained, that is, 30% of the drug load was released in 24 hours after its application. Furthermore, in a study made by Rostamkalaei [

154], solid lipid nanoparticles containing metformin were obtained using the ultrasonication method; this, with the aim of formulating a topical gel as a dermal delivery system to be applied to the skin to improve the administration of metformin. In vitro percutaneous absorption tests were carried out considering the ability of the nanoparticles to penetrate the different layers of the skin; the solid lipid nanoparticle gel with metformin and the gel with metformin alone were compared. The results obtained were nanoparticles with a size of approximately 203 nm with a metformin encapsulation efficiency of 32.9%; In addition, a greater penetration of the gel with the nanoparticles was shown through the different layers of the skin, which is promising in the local administration of metformin and other hydrophilic drugs.

8. Discussion and Future Perspectives

The application of nanotechnology in drug delivery systems represent a significant advance of metformin therapy for T2D treatment. Although its clinical application is frequently limited by gastrointestinal side effects, low bioavailability and a limited absorption rage in the gastrointestinal tract. These challenges have encouraged the development of delivery strategies to enhance metformin’s performance. The literature reviewed in this article highlights the diversity of biopolymers applied as carriers (proteins, synthetic polymers, lipids, polysaccharides) and the versatility of the obtention techniques such as electrospinning, electrospraying, and nanoprecipitation. These approaches allow the adaption of physicochemical properties of metformin formulations to reach specific therapeutic requirements on T2D treatment.

Protein-based nanocarriers (gelatin, albumin, casein) exhibit a wide range of properties for drug delivery and tissue engineering such as biocompatibility, biodegradability and binding capacity. Proteins are biomolecules present in all forms of life, which contributes to their low toxicity (compared to synthetic polymers). They are capable of absorbing water and induce steric repulsion to enhance physical stability of nanocarriers and reduce recognition by the immune system. Usually, proteins are found broadly in nature and are renewable sources by plants, animals and humans, which make them easy to obtain at low costs. On the other hand, the structure, sequence of proteins and various functional groups allow the binding of the drug to a specific site in the protein and binding and the conjugation of targeting ligands to the nanoparticle, allowing selective delivery to target tissues or cells [

172]. Drug delivery systems based on polysaccharides are effective in increasing bioavailability of encapsulated molecules (proteins, peptides, and other therapeutic agents) by promoting transport through the intestinal lymphatic system and enhancing tissue permeability. In addition, such systems allow for lower therapeutic doses, reduce systemic drug distribution, and diminish renal and hepatic clearance, leading to an improved therapeutic attachment and reduced side effects [

173].

The integration of nanotechnology in metformin delivery systems holds an important promise for enhancing its therapeutic efficacy and overcome the limitation of the conventional oral administration. These nanoformulations varies from polymeric nanoparticles to liposomes and micelles, with significant properties to enhance the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the drug and the therapeutic effects. Metformin its known for its lack on oral bioavailability (~60%) due to the hydrophilic nature and restricted absorption in the intestine. Diverse studies have shown that nanoformulations can increase intestinal uptake and prolong gastrointestinal drug residence and delivery time. Polymer-based nanoformulations such as the metformin chitosan mucosal nanoparticles developed by Lu and collaborators [

174], to enhance the bioavailability and prolong the hypoglycemic effect of conventional metformin administration. In the intestinal adhesion study, the reaction rate of the mucosal nanoparticles was 67.27%, compared to online 10.52% for free metformin, suggesting strong adhesion to the intestinal mucosa.

In vitro release studies demonstrated that these nanoparticles provide sustained drug release for over 12 hours in comparison to the commercial formulation with an almost entirely release in 1 hour in an intestinal environment. On the other hand, Jain [

175] obtained a jackfruit seed starch based gastroenterentive nanoparticle, as it represents a biodegradable and biocompatible excipient. In addition to obtaining optimized physicochemical properties, the

in vivo hypoglycemic effect of this nanoformulation was studied on murine model and the results demonstrated the potential clinical benefit of this delivery system. Comparing to free metformin, the nanoparticle formulation maintained a significant reduction in blood glucose levels over 24 hours (50% reduction from 4-8 h; p < 0.01). Beyond the potential therapeutic benefits on T2D treatment, metformin nanoformulations are also drawing significant attention due to the drug’s pleiotropic effects, such as antitumor and neuroprotective properties. One of the mechanisms of metformin is the growth inhibitory effect on cancer cells. Various cell culture models have been employed to associate metformin with antiproliferative effects. In a study involving male and female mice with spinal cord injuries, treatment with metformin in a dosage of 200 mg/kg administered for 14 days led to an increased oligodendrocyte formation in both sexes. This effect was attributed to metformin’s modulation of the atypical protein kinase C (aPKC)-mediated phosphorylation of the CREB-binding protein (CBP) [

176]. In addition to their glucose-lowering and antiproliferative effect, metformin nanoparticle has shown vascular protection. In a recent study by Mohamed et al. [

177], they evaluated the use of metformin nanoMIL-89 based nanoparticles, which exhibited a controlled release of metformin over a 96 hour period, led to a decrease in reactive oxygen species levels in vascular endothelial cells under hyperglycemic conditions, and increase in the phosphorylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, which is critical for maintaining vascular health.

Nevertheless, despite the numerous preclinical evidence reported in literature, there are certain limitations and challenges of these nanocarriers that need to be addressed in order to be successfully implemented. Fortunately, the field on nanomedicine is constantly innovating and evolving and, the research of the nanotechnology in diabetes treatment holds promise for the development of strategies that guarantee effectiveness, safety and more personalized treatment strategies.

9. Conclusions

In recent years, the use of biopolymers as drug delivery systems has been increasing, since they have certain properties that give them the ability to interact with drugs, providing them stability. Therefore, various factors have been varied to control the release of drugs such as polymer concentrations, the technique for obtaining them, crosslinking, among others. In this review we discussed the different methods for obtaining polymer-based nanocarriers for metformin using methods such as electrospinning, electrospraying, and nanoprecipitation. From these techniques, it has been possible to obtain metformin encapsulants with a micro to nanoscale size, accompanied by a high surface-volume ratio, ease of operation and cost effectiveness. In addition, the use of biopolymers offers favorable properties such as biodegradability, biocompatibility, non-toxicity, hydrophilic and immunogenic properties; These properties often lead to improved drug solubility, reduced dose, protection against various environments, and prolonged release. Recent investigations based on the use of biopolymers in the administration of metformin as antidiabetic treatments, chemotherapeutics, tissue regeneration, etc. were also discussed. However, their applications are limited to in vitro studies or mouse models, and therefore further clinical data would be needed to assess the benefits or risks of using polymer-based nanomaterials in drug delivery.

Limitations

this review is primarily based on studies involving in vitro experiments and murine models, which limits the applicability of the findings to human clinical matters. Moreover, the diversity in the polymers utilized for nanoparticle fabrication and characterization methods which present challenges for comparison between studies.

Supplementary Materials

Not applicable

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.A.M.G., F.R.F. and J.A.T.H.; validation, F.R.F., J.R.N.M. and C.LD.T.S.; formal analysis, E.A.M.G. and E.C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.A.M.G; writing—review and editing, J.A.T.H., E.M.R., C.L.D.T.S., D.E.R.F., C.G.B.U. and C.E.F.E.; visualization, F.R.F., E.C.M., I.Y.L.P., C.E.F.E and C.G.B.U.; supervision, F.R.F. and J.A.T.H.; project administration, E.A.M.G., F.R.F. and E.M.R.; funding acquisition, F.R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to privacy/ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the University of Sonora for their support. Eneida Azaret Montaño-Grijalva would like to acknowledge SECIHTI (Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación) for the financial support provided for her graduate studies during this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| T1D |

Type 1 Diabetes |

| T2D |

Type 2 Diabetes |

| GRAS |

Generally Recognized As Safe |

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Diabetes. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on day month year).

- Rocha, S.; Lucas, M.; Ribeiro, D.; Corvo, M. L.; Fernandes, E.; Freitas, M. Nano-based drug delivery systems used as vehicles to enhance polyphenols therapeutic effect for diabetes mellitus treatment. Pharmacological Research 2021, 169, 105604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M. J. Type 2 diabetes. The lancet 2017, 389, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, X.; Chen, Z.; Pang, L.; Wang, L.; Jiang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J. Oral Nano drug delivery systems for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: An available administration strategy for antidiabetic phytocompounds. International journal of nanomedicine 2020, 10215–10240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morantes-Caballero, J.; Londoño-Zapata, G.; Rubio-Rivera, M.; Pinilla-Roa, A. Metformina: más allá del control glucémico. Revista de los Estudiantes de Medicina de la universidad industrial de Santander 2017, 30, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Prevention or Delay of Diabetes and Associated Comorbidities: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care, 2024, vol. 47, no Supplement_1, p. S43-S51. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Xu, X.; Du, M.; Zhao, T.; Wang, J. A preclinical overview of metformin for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Biomedicine; Pharmacotherapy 2018, 106, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rena, G.; Hardie, D.G.; Pearson, E. R. The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia 2017, 60, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, J.; Lipska, K. Metformin in 2019. Jama 2019, 321, 1926–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M. X.; Hua, S.; Shang, Q. Y. Application of nanotechnology in drug delivery systems for respiratory diseases. Molecular Medicine Reports 2019, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, B.; Santi, M. Characterization and Functionalization Approaches for the Study of Polymeric Nanoparticles: The State of the Art in Italian Research. In Micro 2022, 3, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasini, N.; Haque, S.; Kaminskas, L. M. Polymer-drug conjugates as inhalable drug delivery systems: A review. Current Opinion in Colloid; Interface Science 2017, 31, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; Yu, D. G.; Zhu, M. J.; Zhao, M.; Williams, G. R. Tunable zero-order drug delivery systems created by modified triaxial electrospinning. Chemical Engineering Journal 2019, 356, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, S. C.; Estevinho, B. N.; Rocha, F. Encapsulation in food industry with emerging electrohydrodynamic techniques: Electrospinning and electrospraying–A review. Food Chemistry 2021, 339, p. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadian, F.; Eatemadi, A. Drug loading and delivery using nanofibers scaffolds. Artificial cells, nanomedicine, and biotechnology 2017, 45, 881–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhtakia, R. The history of diabetes mellitus. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal 2013, 13, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersmann, A.; Müller-Wieland, D.; Müller, U. A.; Landgraf, R.; Nauck, M.; Freckmann, G.; Schleicher, E. Definition, classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology. Diabetes 2019, 127, S1–S7. [Google Scholar]

- Eizirik, D. L.; Pasquali, L.; Cnop, M. Pancreatic β-cells in type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus: different pathways to failure. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2020, 16, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes: standards of care in diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care, 2025, vol. 48, no Supplement_1, S27-S49.

- Plows, J. F.; Stanley, J. L.; Baker, P. N.; Reynolds, C. M.; Vickers, M. H. The pathophysiology of gestational diabetes mellitus. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, A.; Gudbjörnsdottir, S.; Rawshani, A.; Dabelea, D.; Bonifacio, E.; Anderson, B.J.; Lernmark, Å. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nature reviews Disease primers 2017, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, R. I.; DeVries, J. H.; Hess-Fischl, A.; Hirsch, I. B.; Kirkman, M. S.; Klupa, T.; Peters, A. L. The management of type 1 diabetes in adults. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2021, 44, 2589–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayed, N. A.; Aleppo, G.; Aroda, V. R.; Bannuru, R. R.; Brown, F. M.; Bruemmer, D.; Gabbay, R. A. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of Care in diabetes—202. Diabetes Care 2023, 46, S140–S157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhi, S.; Nayak, A.K.; Behera, A. Type II diabetes mellitus: A review on recent drug-based therapeutics. Biomedicine; Pharmacotherapy 2020, 131, 110708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Top, W. M.; Kooy, A.; Stehouwer, C. D. Metformin: a narrative review of its potential benefits for cardiovascular disease, cancer and dementia. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Duarte, S.; Carvajal, L.; Garchitorena, M. J.; Subiabre, M.; Fuenzalida, B.; Cantin, C.; Leiva, A. Gestational diabetes mellitus treatment schemes modify maternal plasma cholesterol levels dependent to women s weight: Possible impact on feto-placental vascular function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Jokerst, J. V. Structured micro/nano materials synthesized via electrospray: a review. Biomaterials Science 2020, 8, 5555–5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, X.; Ye, X.; Ares, I.; Lopez-Torres, B.; Martínez, M.; Martínez, M. A. Mitochondria as an important target of metformin: The mechanism of action, toxic and side effects, and new therapeutic applications. Pharmacological research 2022, 106114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvijić, S.; Parojčić, J.; Langguth, P. Viscosity-mediated negative food effect on oral absorption of poorly-permeable drugs with an absorption window in the proximal intestine: In vitro experimental simulation and computational verification. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2014, 61, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.S.; Jusko, W. J. Meta-assessment of metformin absorption and disposition pharmacokinetics in nine species. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMoia, T.E.; Shulman, G. I. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin action. Endocrine Reviews 2021, 42, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Massey, S.; Story, D.; Li, L. Metformin: an old drug with new applications. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, 2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasurya, V.; Anjum, H.; Surani, S. Metformin use and metformin-associated lactic acidosis in intensive care unit patients with diabetes. Cureus 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. W.; He, S. J.; Feng, X.; Cheng, J.; Luo, Y. T.; Tian, L.; Huang, Q. Metformin: a review of its potential indications. Drug design, development and therapy 2017, 2421–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, C.; Retzik-Stahr, C.; Singh, V.; Plomondon, R.; Anderson, V.; Rasouli, N. Should metformin remain the first-line therapy for treatment of type 2 diabetes? Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism 2021, 12, 2042018820980225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbere, I.; Kalnina, I.; Silamikelis, I.; Konrade, I.; Zaharenko, L.; Sekace, K.; Klovins, J. Association of metformin administration with gut microbiome dysbiosis in healthy volunteers. PloS one 2018, 13, e0204317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatore, T.; Pafundi, P. C.; Marfella, R.; Sardu, C.; Rinaldi, L.; Monaco, L.; Sasso, F. C Metformin lactic acidosis: Should we still be afraid? . Diabetes research and clinical practice 2019, 157, 107879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabi, D. F.; Qasim, A. H.; Kareem Mohammed, S. A.; Omran Al-Saadawi, A. I. Association of Metformin Use with Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Iraqi Patients with Type II Diabetes Mellitus. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine; Toxicology 2021, 15, 4729. [Google Scholar]

- Bahman, F.; Greish, K.; Taurin, S. Nanotechnology in insulin delivery for management of diabetes. Pharmaceutical nanotechnology 2019, 7, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhakar, P. ; Banerjee, M Nanotechnology in drug delivery system: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research 2020, 12, 492–498. [Google Scholar]

- Patra, J. K.; Das, G.; Fraceto, L. F.; Campos, E. V. R.; del Pilar Rodriguez-Torres, M.; Acosta-Torres, L. S.; Shin, H. S. Nano based drug delivery systems: recent developments and future prospects. Journal of nanobiotechnology 2018, 16, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, T.; Ratre, Y. K.; Chauhan, S.; Bhaskar, L. V. K. S.; Nair, M. P.; Verma, H. K. Nanotechnology based drug delivery system: Current strategies and emerging therapeutic potential for medical science. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2021, 63, 102487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Khan, M. A.; Haider, N.; Ahmad, M. Z.; Ahmad, J. Recent advances in theranostic applications of nanomaterials in cancer. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2022, 28, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zhou, X.; Chen, G.; Su, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, P.; Min, Y. Advances of functional nanomaterials for magnetic resonance imaging and biomedical engineering applications. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2022, 14, e1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, L.; Fan, Y.; Feng, Q.; Cui, F. Z. Biocompatibility and toxicity of nanoparticles and nanotubes. Journal of Nanomaterials 2012, 6–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reise, M.; Kranz, S.; Guellmar, A.; Wyrwa, R.; Rosenbaum, T.; Weisser, J.; Sigusch, B. W. Coaxial electrospun nanofibers as drug delivery system for local treatment of periodontitis. Dental Materials. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonazzi, A.; Cid, A. G.; Villegas, M.; Romero, A. I.; Palma, S. D.; Bermúdez, J. M. Nanotechnology applications in drug-controlled release. In Drug targeting and stimuli sensitive drug delivery systems 2018, 81–116. [Google Scholar]

- Perumal, S. Polymer Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 5449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.S.; Wadher, S. J. Potential Nanomaterials for the Treatment and Management of Diabetes Mellitus. In Nanomaterials for Sustainable Development: Opportunities and Future Perspectives 2023, 297-312.

- Li, M.; Du, C.; Guo, N.; Teng, Y.; Meng, X.; Sun, H.; Li, S.; Yu, P.; Galons, H. Composition design and medical application of liposomes. European journal of medicinal chemistry 2019, 164, 640–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikezić, A.V.V.; Bondžić, A. M.; Vasić, V. M. Drug delivery systems based on nanoparticles and related nanostructures. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 151, 105412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, V.; Maske, P.; Khan, A.; Ghosh, A.; Keshari, R.; Bhatt, M.; Srivastava, R. Responsive Nanostructure for Targeted Drug Delivery. Journal of Nanotheranostics 2023, 4, 55–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begines, B.; Ortiz, T.; Pérez-Aranda, M.; Martínez, G.; Merinero, M.; Argüelles-Arias, F.; Alcudia, A. Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery: Recent developments and future prospects. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souto, E. B.; Souto, S. B.; Campos, J. R.; Severino, P.; Pashirova, T. N.; Zakharova, L. Y.; Santini, A. Nanoparticle delivery systems in the treatment of diabetes complications. Molecules 2019, 24, 4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wechsler, M. E.; Vela Ramirez, J. E.; Peppas, N. A. 110th anniversary: nanoparticle mediated drug delivery for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease: crossing the blood–brain barrier. Industrial; engineering chemistry research, 58, 15079–15087.

- Khalid, M.; El-Sawy, H. S. Polymeric nanoparticles: Promising platform for drug delivery. International journal of pharmaceutics 2017, 528(, 675–691. [Google Scholar]

- Zielińska, A.; Carreiró, F.; Oliveira, A. M.; Neves, A.; Pires, B.; Venkatesh, D. N.; Souto, E. B. Polymeric nanoparticles: production, characterization, toxicology and ecotoxicology. Molecules 2020, 25, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, K.C. D.; Costa, J. M.; Campos, M. G. N. Drug-loaded polymeric nanoparticles: a review. International Journal of Polymeric Materials and Polymeric Biomaterials 2022, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyisan, B.; Landfester, K. Modular approach for the design of smart polymeric nanocapsules. Macromolecular rapid communications 2019, 40, 1800577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Gigliobianco, M. R.; Censi, R.; Di Martino, P. Polymeric nanocapsules as nanotechnological alternative for drug delivery system: current status, challenges and opportunities. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrejola, M. C.; Soto, L. V.; Zumarán, C. C.; Peñaloza, J. P.; Álvarez, B.; Fuentevilla, I.; Haidar, Z. S. Sistemas de nanopartículas poliméricas II: estructura, métodos de elaboración, características, propiedades, biofuncionalización y tecnologías de auto-ensamblaje capa por capa (layer-by-layer self-assembly). International Journal of Morphology 2018, 36, 1463–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matoba, T.; Koga, J. I.; Nakano, K.; Egashira, K.; Tsutsui, H. Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery system for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Journal of cardiology 2017, 70, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, E.; Yang, J.; Cao, Z. Strategies to improve micelle stability for drug delivery. Nano research 2018, 11, 4985–4998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardaxi, A.; Kafetzi, M.; Pispas, S. Polymeric nanostructures containing proteins and peptides for pharmaceutical applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, S.M.; Figueiras, A.R.; Veiga, F.; Concheiro, A.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C. Polymeric micelles for oral drug administration enabling locoregional and systemic treatments. Expert opinion on drug delivery 2015, 12, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhmalzade, B.S.; Chavoshy, F. Polymeric micelles as cutaneous drug delivery system in normal skin and dermatological disorders. Journal of advanced pharmaceutical technology; research 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pham, D. T.; Chokamonsirikun, A.; Phattaravorakarn, V.; Tiyaboonchai, W. Polymeric micelles for pulmonary drug delivery: a comprehensive review. Journal of Materials Science 2021, 56, 2016–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, P.; Sadarani, B.; Majumdar, A.; Bhullar, S. Nanofiber based drug delivery systems for skin: A promising therapeutic approach. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2017, 41, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, B.; Park, M.; Park, S. J. Drug delivery applications of core-sheath nanofibers prepared by coaxial electrospinning: a review. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahalingam, S.; Huo, S.; Homer-Vanniasinkam, S.; Edirisinghe, M. Generation of core–sheath polymer nanofibers by pressurised gyration. Polymers 2020, 12, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, G.; Tahmasebi, S.; Mohajer, F.; Badiei, A. The role of carbon nanotubes in antibiotics drug delivery. Frontiers Drug Chemestry Clinicl Res 2021, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Gill, G.S.; Jeet, K. Applications of Carbon Nanotubes in Drug Delivery. Characterization and Biology of Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery 2019, 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. U.; Khan, M.; Cho, M. H.; Khan, M. M. Selected nanotechnologies and nanostructures for drug delivery, nanomedicine and cure. Bioprocess and biosystems engineering 2020, 43, 1339–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shan, X.; Luo, C.; He, Z. Emerging nanoparticulate drug delivery systems of metformin. Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation 2020, 50, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño-Herrera, R.; Louvier-Hernández, J. F.; Escamilla-Silva, E. M.; Chaumel, J.; Escobedo, A. G. P.; Pérez, E. Prolonged release of metformin by SiO2 nanoparticles pellets for type II diabetes control. European journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2019, 131, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bhanjana, G.; Verma, R. K.; Dhingra, D.; Dilbaghi, N.; Kim, K. H. Metformin-loaded alginate nanoparticles as an effective antidiabetic agent for controlled drug release. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2017, 69, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Choi, D. W.; Kim, H. N.; Park, C. G.; Lee, W.; Park, H. H. Protein-based nanoparticles as drug delivery systems. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-López, A. L.; Pangua, C.; Reboredo, C.; Campión, R.; Morales-Gracia, J.; Irache, J. M. Protein-based nanoparticles for drug delivery purposes. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2020, 581, 119289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]