1. Introduction

Peter Medawar once defined pregnancy as an “immunological paradox” that requires vigilant immunomodulation to allow successful gestation and parturition. This paradox is rooted in the ability of the semi-allogenic foetus to survive within its mother whilst constitutively expressing paternal alloantigens. It is established that the presence of the immune system enables gestation to take place; however, disturbances in this finely tuned system can arise as a crucial protagonist in many disorders that occur during pregnancy, one being Chronic Histiocytic Intervillositis (CHI).

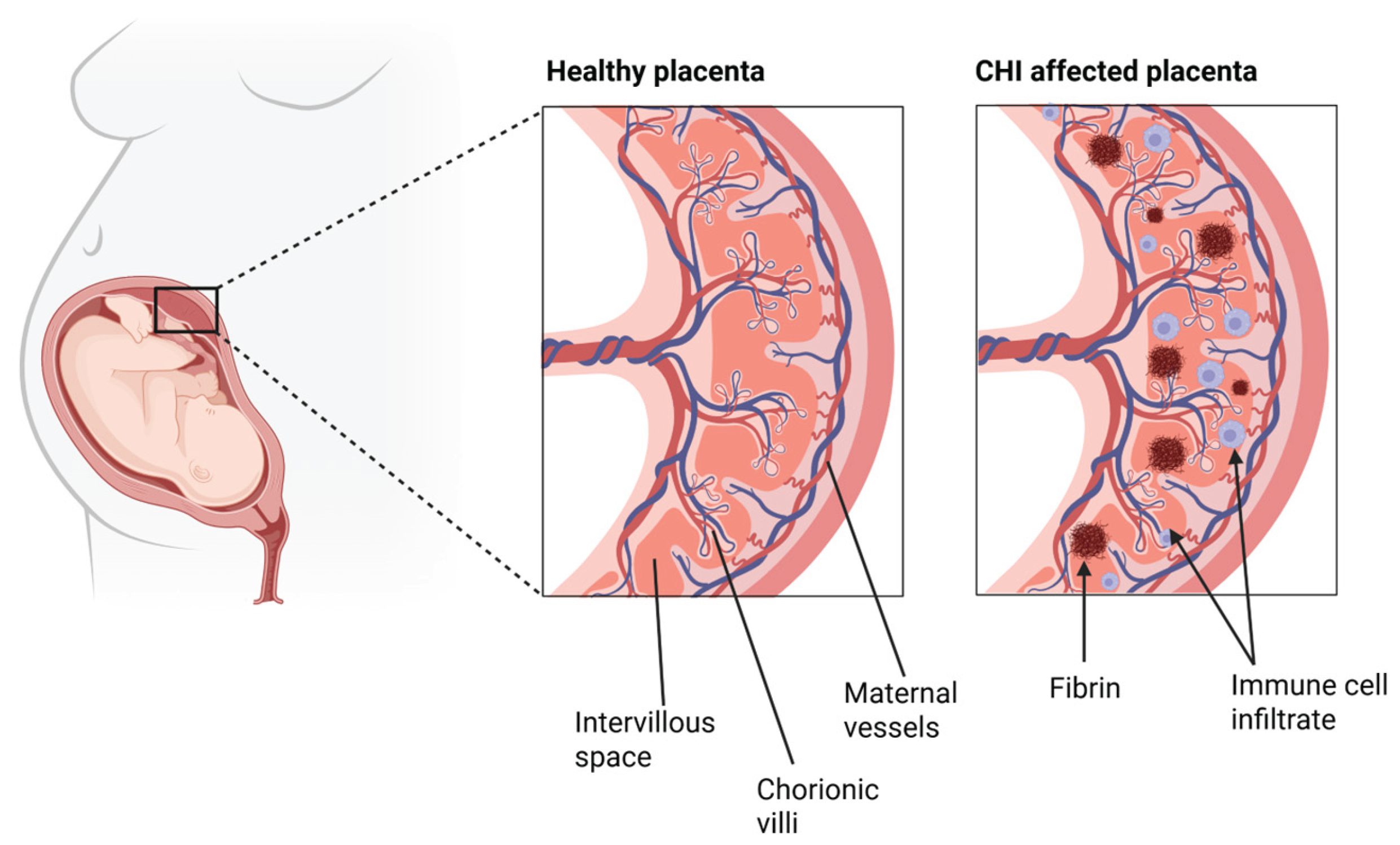

CHI is a rare placental inflammatory disorder that can occur at any stage of pregnancy, first described by Labarrere and Mullen in 1987. It is characterised by the infiltration of maternal histiocytes, a form of tissue-resident macrophages and the presence of fibrin deposition in the placental intervillous space [1]. The aetiology of CHI remains unknown, further fueling its inconspicuous and enigmatic nature, but the presence of these maternal immune cell infiltrates suggests an immunological origin. CHI is estimated to affect 6 in every 10,000 pregnancies beyond 12 weeks gestation [2] (WG) and is associated with pregnancy adverse outcomes such as fetal growth restriction (FGR), miscarriage and stillbirth [3,4,5]. Although a relatively rare disease, it has a high recurrence rate of 70% to 100% in subsequent pregnancies and a 77% perinatal mortality rate overall [6]. These pertinent statistics highlight the significant clinical relevance of CHIs.

CHI may not exhibit overt symptoms during pregnancy, so diagnosis can only be made postpartum. Histopathological examination of the placenta is used to identify histiocytic infiltrates in the intervillous space [8]. For a positive diagnosis, approximately 80% of the mononuclear cells present should be CD68+, and the infiltrate should occupy 5% or more of the total space [8]. Yet, there are currently no standardised diagnostic criteria, and a lack of prenatal biomarkers makes CHI’s diagnosis challenging. Therefore, clinical intervention is only possible in future pregnancies for women who have had a previously affected pregnancy. Common treatments for pregnancies affected by CHI include low molecular weight heparin as well as Aspirin and Prednisolone, in combination therapy or alone [9,10]. Current evidence suggests that these treatments don’t have a significant effect on the perinatal outcome [5,9,10], demonstrating a need for the development of novel, effective therapies for CHI

This combination of poor pregnancy outcomes and high recurrence rates emphasises the need for a nuanced comprehension of the mechanisms underlying CHI. The proposed hypothesis in the current literature suggests an alloimmune mechanism, where an abnormal maternal immune response to the paternally inherited fetal antigens is present [11]. Determining evidence of an antibody response in CHI could significantly enhance diagnostic accuracy and allow for more targeted and effective therapies. This review aims to explore unexplained CHI with a focus on the alloimmune mechanisms present. In particular, the review will emphasise the role of antibodies, specifically those targeting mismatched human leukocyte antigen (HLA) alleles, in the pathogenesis of CHI and how this shapes future treatments.

2. Normal Placental Function

The placenta is a vital organ emerging during pregnancy that forms the interface between the foetus and mother. For pregnancies to be successful, correct angiogenesis must take place during implantation and placental formation to allow for sufficient oxygenated blood and nutrients to reach the foetus. In just the second week of gestation, the initiation of the maternal fetal circulation begins. This is carried out through the formation of chorionic villi, which are formed from the fetal-derived syncytiotrophoblast growing into the cytotrophoblast, thereby creating the trophoblast. These trophoblast cells cover the chorionic villi that invade the uterine wall, establishing primary chorionic villi. As gestation progresses, the increasingly invasive properties of the chorionic villi enable them to be submersed in maternal blood within the intervillous space. Maternal blood can then be supplied from spiral arteries, where it brings both adequate oxygen and nutrients to the foetus via the umbilical vein [12].

In CHI, it is believed that this careful development and maintenance of the maternal-fetal circulation is disrupted through various structural and immunological mechanisms, as depicted in

Figure 1. Since CHI pathogenesis and aetiology are still relatively unclear, this will be further explored through discussion of the individual roles of key factors in the immune system.

3. Monocytic Histiocytes

It remains unclear as to whether the presence of monocytic histiocytes in the intervillous space, specifically those that are CD68 positive [13,14], play a pathogenetic role in CHI despite their use as a diagnostic marker.

Using immunohistochemistry, Hussein et al. characterised intervillous histiocytes in placentas from 14 women with Chronic intervillositis of unknown aetiology (CIUE), 8 with villitis of unknown aetiology and 19 without lymphohistiocytic infiltration. The phenotype of the infiltrating histiocytes was similar to M2-like non-inflammatory macrophages, highlighted by the expression of CD163 [15,16]. This polarisation towards the M2 phenotype is in accordance with other studies [17] that identify a large discrepancy between pro-inflammatory cytokine upregulation and histiocytic accumulation in the intervillous space in CHI, suggesting these monocytes are non-destructive and resting. This was identified by Freitag et al., [17] who found a striking lack of inflammatory-associated genes through RNA extraction and transcript expression assays of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded placental samples. 5 placentas with CHI vs 7 normal placentas vs 4 with villitis of unknown aetiology (VUE) were analysed. Both CCL2, a potent monocyte attracter and activator and IL-8, also a monocyte attracter, were found not to be increased in CHI. These findings suggest that histiocytic accumulation in CHI may not be a pathological driver of the disease.

Additionally, Hofbaeur cells, a type of fetal macrophage located in the villous stroma and decidual histiocytes, maintained CD206 and CD209 expression in patients with CHI [15]. These findings illustrate that the inflammatory M1 phenotype was not induced in these cells, whilst they displayed no aberrant marker expression profile, again indicating the potential non-infiltrating and non-destructive nature of these histiocytes in CHI. These cells also under-expressed CD11c/CD18, both of which form the complement factor receptor CR4. This lack of expression may also indicate that these monocytes are actively attempting to reduce complement activation in CHI, thereby leading to a reduction in inflammation.

However, a recent study contradicts these findings. Multiplex immunofluorescence of placental CHI samples compared to controls by Albersammer et al. [18] identified predominantly an M1-like macrophage population in the intervillous space and increased expression of IL-18BP, which can inhibit the switch of M1 macrophages to the M2 phenotype. Conversely, they found abundant Hofbauer cells and increased IL-1 RN gene expression that codes for an IL-1 receptor antagonist, which is a signature M2 cytokine. These findings prompt the hypothesis that the phenotypes of M1 and M2 macrophages may not be as distinct as they demonstrate in vivo. M1 and M2 macrophages have been shown to exhibit significant plasticity, depending on their environment. Krop et el [13] demonstrated this with macrophages coexpressing both M1 and M2 markers, suggesting there may be a more fluid population of macrophages in CHI than we once thought. This is seen in cancer where M2 macrophages can be both anti-tumour and tumour promoting [19].

Additionally, M2 macrophages, when complexed with IgG and toll-like receptors (TLR) ligands, mimicking the disease process in Rheumatoid Arthritis, released pro-inflammatory cytokines: IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α [20]. Therefore, identification of an M2 macrophage in CHI may not be indicative of a non-inflammatory histiocyte as the paradigm of the monocyte’s properties and capabilities in vitro is ever-changing. Moreover, Hussein et al. found in the same characterisation that the histiocytes expressing CD163 also over-expressed CD11c/CD18. Additionally, it must be noted that it is also believed that the large accumulation of these monocytic histocytes into the intervillous space, regardless of their phenotype, disrupts the diffusing distance of oxygen between the fetal chorionic villi and maternal erythrocytes [21]. These findings indicate that the monocytic histiocytes could play a destructive role of CHI by interacting with the complement system, allowing their vast accumulation, leading to placental insufficiency and fetal growth restriction.

4. Perivillous Fibrin Deposition

It is well known that CHI presents with perivillous fibrin deposition, [2,5,22,23] which involves the formation of fibrinoid material in the intervillious space during gestation, resulting in chronic placental insufficiency [24]. This is due to obstructions in maternal blood flow to the fetal vascular spaces [25], by the occlusion of the chorionic villi therefore, reducing the exchange and perfusion of necessary nutrients and oxygen for fetal growth. This destructive nature of fibrinogen deposits has been exhibited by Marchaudon et al. that demonstrated an association of early abortion and intrauterine growth restriction in women with greater fibrin deposits diagnosed with Chronic histiocytic intervillositis of unknown etiology (CIUE) [4]. Labarrere et al. also identified a significant failure for the transformation of spiral arteries and the presence of atherosclerotic like lesions on the placentas of those with CHI and Chronic villitis of unknown etiology (CVUE) compared to controls [26]. These findings further validate the occlusive nature of the placental lesions in CHI and the extremely early effects CHI can have on gestational developments, due to a lack of spiral artery formation. Not only does perivillous fibrin deposition play a role in the pathogenesis of CHI but its presence is a signature for the involvement of immunological fetal rejection in CHI. This has been demonstrated by Romero et al. who identified increased plasma cell deciduitis, maternal anti-HLA class I, C4d deposition and maternal antibodies against fetal HLA class I and II antigens in those with massive perivillous fibrin deposition vs those with uncomplicated pregnancies [24]. Perivillous fibrin deposition may also provide a basis for innate immune system activation in CHI, leading to additional inflammatory cellular recruitment. Villous ischemia and infarction to fetal and chorionic tissues, caused by chronic fibrin deposition in CHI may act as a damage associated molecular patterns (DAMP) for key innate sensors as explained below.

5. Inflammasomes

An emerging study has identified the potential contribution of an ancient component of the innate immune system in CHI; the inflammasome [27]. Activated by a repertoire of stimuli, including host derived signals (ion influx, reactive oxygen species, hypoxia, debris from cellular death and mitochondrial dysfunction) [28,29], mobilisation of the inflammasome results in the release of IL-1β and IL-18 [28], endowing to heightened inflammation in the form of pryoptosis and apoptosis [28]. Through transcriptomic analysis of 18 CHI placental samples vs 6 controls, Mattuizzi et al. [27] identified the presence of dysregulated inflammasome pathways in those with CHI. Inflammasome related gene expression, (NLP3, PYCARD, CASPASE and MEFV) was identified to be significantly greater in all those with CHI along with genes encoding pro inflammatory cytokines produced by the inflammasome and their transcriptional signatures such as, IL-1β and IL-18. Additionally, administration of inflammasome blockade treatment given to 3 patients with a history of recurrent CHI resulted in 3 healthy term pregnancies at 37 WG. Immunohistochemistry of the placental tissues from patients 1 and 2 also identified the presence of widespread staining for NLRP3 and PYCARD, along with a down regulation in their expression following treatment with the inflammasome blockage drugs. These findings indicate a potential upregulation of innate pathways such as the NLRP3 inflammasome in CHI along with a likely treatment strategy.

It can be hypothesised that this inflammasome activation is as a result of debris from necrotic trophoblastic tissue acting as DAMP, inducing inflammasome activation, leading to heightened inflammation and placental insufficiency. However, this poses inflammasome activation to be a secondary pathway in the pathogenesis of CHI which causes increased inflammation and cellular recruitment following histiocytic invasion and fibrin deposition, contributing to necrotic tissue formation. Therefore, although inflammasome activation may play a role in the pathogenesis of CHI in some pregnant women, its activation alone is not a sole immunological driver of the CHI and therefore, targeting it therapeutically may not offer a curative solution on a large-scale basis.

6. Complement and Histopathological Similarities to ABMR

The state of maternal immunological tolerance to a semi-allogenic foetus during pregnancy has often been compared to donor organ transplantation [30]. Allograft rejection can occur when donor specific antibodies (DSAs) are formed against antigens, mainly HLA, on the allograft vasculature. This is classified as antibody-mediated rejection (ABMR). Since allograft rejection is a better understood process with clearer diagnostic criteria, modelling CHI against ABMR has provided a more detailed insight into the alloimmune mechanisms present. CHI’s immunological comparisons to ABMR have also revealed evidence for the role of the complement system in its pathogenesis. Split into 3 pathways; classical, lectin and alternative it strives to opsonise pathogens, recruit phagocytic cells and ultimately cause cell death. Following a series of catalytic events, the complement cascade concludes by generating a pore on the surface of the cell’s membrane using the membrane attack complex (MAC) eventually leading to cellular lysis and destruction [31]. Evidence of the complement system being activated in CHI and similarities to histopathological evidence in ABMR provides further confirmation of pathological immunological involvement.

A study by Benachi et al. conducted research on two patients who experienced healthy primary pregnancies followed by fetal loss in subsequent pregnancies associated with CHI [22]. Examination of the placentas through light microscopy and immunostaining found intervillous infiltration of CD68+ histiocytes and fibrinoid deposits, consistent with CHI. CD68+ histiocytes are also found accumulated in the dilated peritubular capillaries of patients with ABMR in kidney allografts. The presence of CD68+ histiocytes in both instances, accompanied by fibrinoid material in the CHI placentas, provides evidence of acute tissue injury. This meets a diagnostic criterion of ABMR, and the shared histological features indicate a common immune-driven pathogenesis, supporting the hypothesis of an antibody-mediated response in CHI.

C4d immunostaining findings in the investigation by Benachi et al. revealed ongoing or recent antibody interactions in CHI, another criteria for ABMR diagnosis [22]. C4d, a product of C4 is used as evidence in ABMR of complement activation in response to antibodies binding allogenic HLAs. This also leads to ABMR in allograft recipients that produce DSAs. Linear C4d staining was observed along the placental interface, particularly on the microvillous surface of the syncytiotrophoblasts, resembling patterns observed in the microvascular beds of kidney allografts during ABMR [22,32]. This was also demonstrated by Bendon et al. along with greater deposition of C4d being identified in the placentas of those with intervillositis versus villitis [23]. Furthermore, positive C4d staining identified by Benachi et al. was seen on the trophoblastic side of the chorionic plate, which is in direct contact with the maternal blood in the intervillous space but was absent on the amniotic side. These observations indicate complement activation, caused by the binding of maternal alloantibodies to paternal antigens on the syncytiotrophoblasts in CHI.

Abundant C4d deposits were also seen in venous vessels of the chorionic plate [22]. This same staining was not observed in arterial vessels, suggesting foetus-specific antibodies likely cross the placental barrier as well as bind to the trophoblastic villi. This would trigger complement activation in the endothelial lining of the veins, leading to C4d deposition and formation of C5b-9 which was also found on the surface of the villi. The accumulation of C5b-9 indicates local complement activation and formation of the MAC. Complement deposition along with fibrin formation through the recruitment of macrophages, monocytes and NK cells, endothelial cell damage and disruption of vascular function causes graft loss in ABMR [2]. Therefore, it is proposed that complement fixation along the microvillous boarder of the syncytiotrophoblast along with cytokine induced monocyte adhesion damages the critical absorptive surface of the syncytiotrophoblasts and the intervillous space. This, therefore, results in the destruction of necessary fetal and maternal exchanges vital for growth and survival of the foetus consequently resulting in poor obstetric outcomes such as those associated with CHI [33]. Therefore, the common histopathological features of CHI with allograft rejection indicate a shared alloantibody-mediated mechanism leading to the placenta’s inability to facilitate fetal growth and survival in CHI.

7. Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes and Viral Infection

Several studies suggest that CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes have a role in the immunological fetal rejection that occurs during CHI. Following activation, their functional abilities include production of cytolytic perforin, granzymes and proinflammatory cytokines which cause cytotoxic effects.

Reus et al. [11], identified significantly greater levels of partner directed cytotoxic T-lymphocyte precursor frequencies (CTLpf) in women with CHI vs non complicated pregnancies. Identification of CTLpf was determined from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), followed by measuring the fluorescence released from Europium labelled target cells. This has also been detected by Molenaar et al. [34] when analysing PBMCs from those suffering with CHI. Higher proportions of CD8+ lymphocytes in the intervillous space from those with CHI have also been identified by Albersammer et al. [18,35], Similar results have also been found in other detrimental gestational outcomes associated with CHI such as increased CD8+ T cell infiltration in the placental villious tissue in fetal growth restriction and miscarriage [36,37]. In the same study [36] Lager et al. identified the presence of CD8+ T cell hotspots in pregnancies classified to be small for gestational age. Additionally, CD8+ T cells are in abundance and heavily implicated during allograft rejection [38,39]. These findings indicate the abnormal presence of CD8+ T cells in the decidua and placental villous tissue of those with CHI.

Whilst investigations have not yet been conducted into the functionality and expression of co stimulatory and inhibitory molecules of CD8+ T cells in CHI, studies demonstrate the importance of the regulation of these proteins during pregnancy. CD8+ T cells express high levels of inhibitory receptors during gestation such as PD-1 and these are thought to be used to inhibit their own activation, therefore regulating inflammation. Diminished PD1+ CD8+ effector memory cells have been identified in pre eclampsia [40,41] and CD8+ T cells expressing inhibitory receptors are reduced in women with recurrent miscarriage [37,42]. Therefore, investigations into CD8+ T cells in the decidua of those with CHI may shed light on their role in CHI pathogenesis.

8. Anti-HLA Antibodies

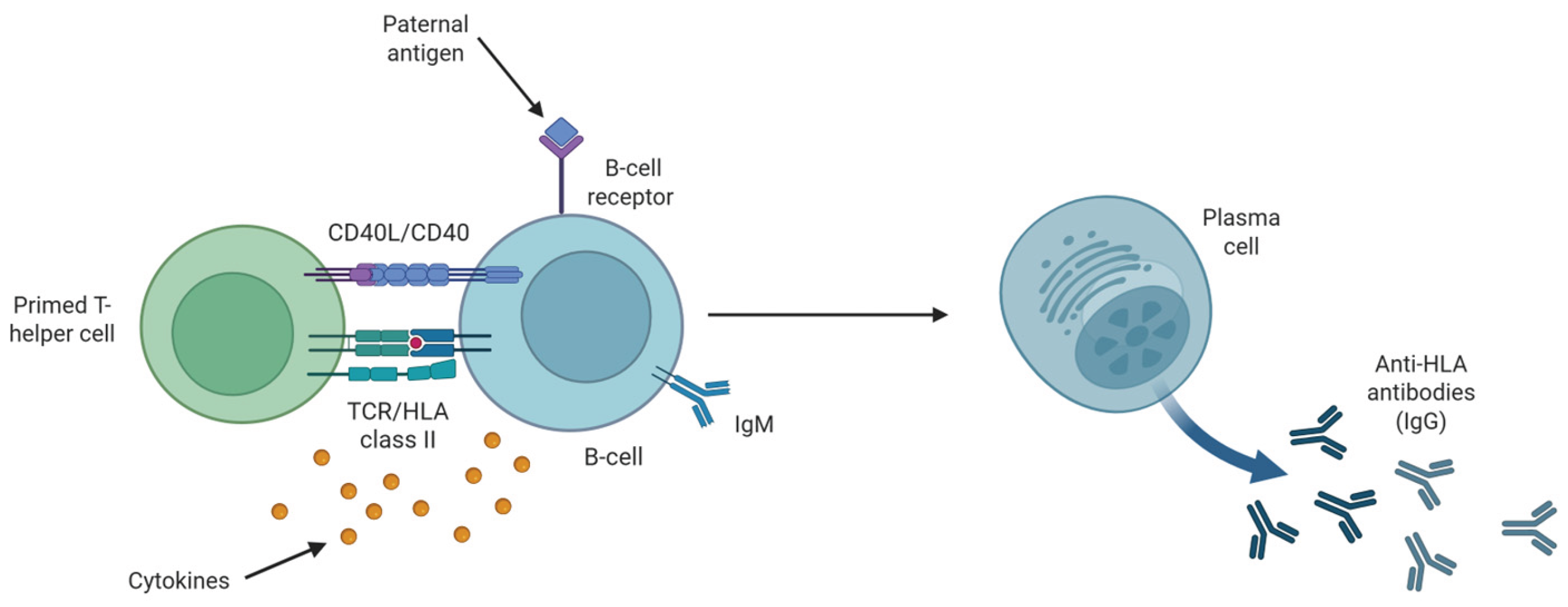

Multiple studies have shown that anti-HLA antibodies form during pregnancy. This occurs via interaction between activated B-cells, through antigenic uptake of inherited paternal HLA antigens by the B-cell receptor, and primed T-helper cells [43]

(Figure 2). Co-stimulation by T-helper cells via CD40-CD40L interaction and cytokine secretions drive proliferation and differentiation of naïve B-cells to plasma cells, inducing isotype switching from IgM to IgG [43]

(Figure 2). Reportedly, these anti-HLA antibodies are present in 30% of successful pregnancies without adverse effects [23,44].

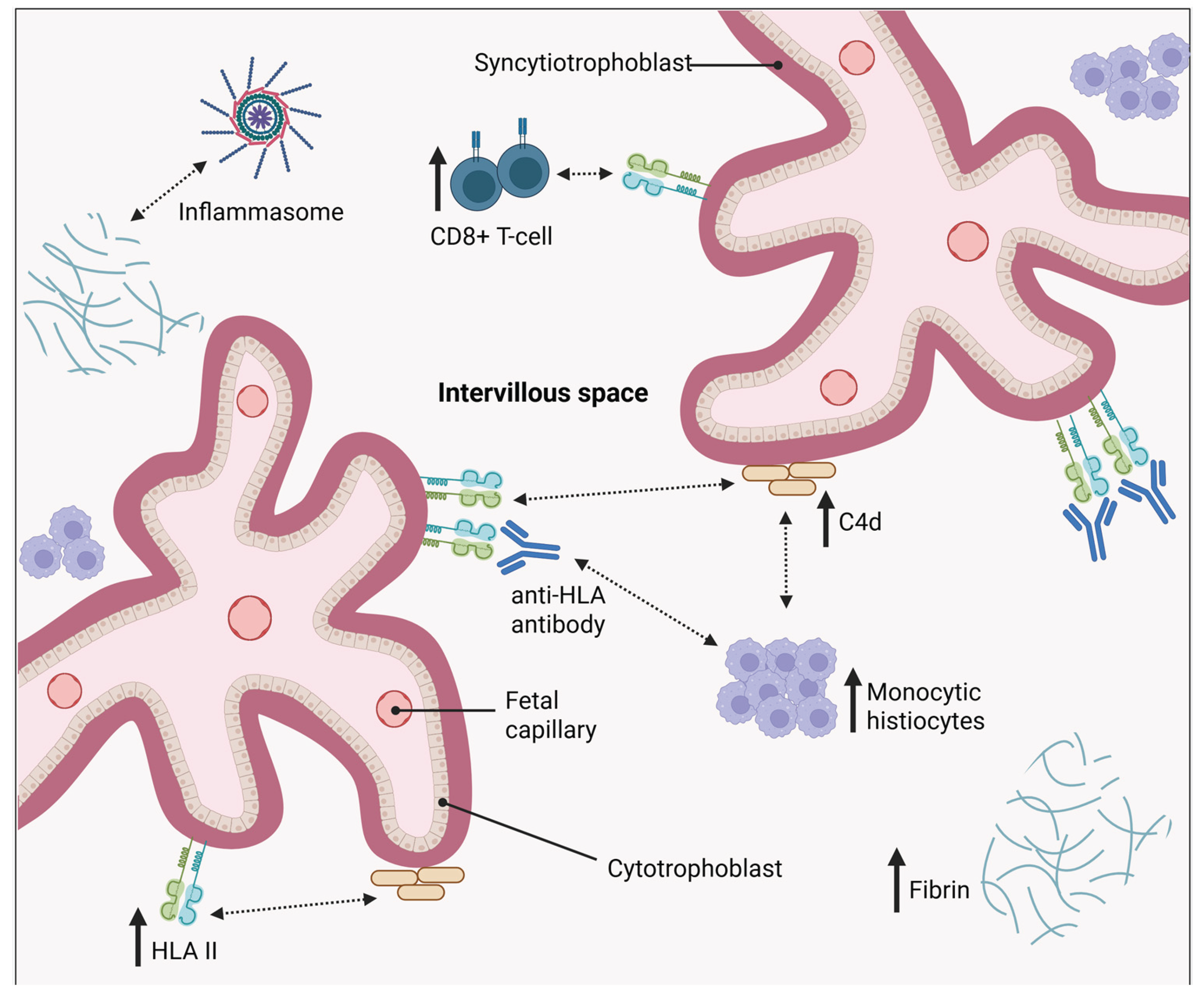

Despite their presence in healthy pregnancy, there is increasing evidence of an antibody-mediated component in CHI pathogenesis. Capable of binding to the HLA antigens expressed on the trophoblasts, these antibodies trigger the complement cascade resulting in cytokine upregulation, monocyte infiltration and effector cell recruitment such as NK cells, which could be the cause of placental inflammation in CHI [2,23,45]. Several factors contribute to the hypothesis of an antibody response in CHI. Firstly, increased levels of these antibodies against paternally derived fetal HLA have been identified in women with CHI [11,22]. High humoral (B-cell) responses, and also T cell responses, have also been reported against the partner specific antigens in CHI [11], further supporting the theory of excessive maternal inflammation. Moreover, increased CD79α+ B cells in the villous tissue of women experiencing small fetal gestational age and growth restriction [36] as well as a higher frequency of anti-HLA antibodies being identified in women with recurrent miscarriages, and its association with a reduced chance of live birth has been found46, [47]. This is comparable to CHI which is associated with several negative fetal outcomes including miscarriage.

Although there is evidence supporting this theory, there are conflicting findings in the literature that challenge understanding of these anti-HLA antibodies role in CHI pathogenesis. A case-control study by Brady et al. found 47.1% of healthy control pregnancies tested positive for anti HLA antibodies in comparison to 35.7% of participants with a history of CHI [48]. As well as finding no significant difference between the proportion of participants testing positive for anti-HLA antibodies, no significant difference in the level of sensitisation was found either. Overall, the results of this study show that whilst individual case reports point to elevated maternal anti-HLA antibodies involvement in the pathogenesis of CHI, this has not yet been replicated in larger scale studies with more rigorous design. Furthermore, evidence of the antibodies’ ability to bind the maternal-fetal interface of the placenta in CHI, as well as the effect of this on placental function, is still lacking in current literature. Since low levels of anti-HLA antibodies can occur as a normal physiological response during healthy pregnancies following paternal antigen exposure, it is critical that more robust evidence of an antibody-mediated mechanism in CHI is identified to confirm their clinical relevance.

9. Abnormal HLA Expression

Whilst it’s clear that an antibody response is relevant to the pathogenesis of CHI, current understanding is limited by differing reports on anti-HLA antibody levels in CHI [10,22,48] and a lack of evidence of antibody binding to the maternal-fetal interface. However, recent investigations of HLA expression could explain the development of antibodies against paternally derived antigens in CHI [48].

Modification of placental HLA molecule expression is a protective mechanism involved in human pregnancy that prevents immunological recognition and rejection of the foetus. HLA-I has exclusively six loci split into classical and non-classical molecules with varying expressions across cells [49]. Crucially, HLA-G, a non-classical HLA-I, is specifically and abundantly expressed in the extra villous trophoblasts (EVT) [50]. This exclusive expression allows a suitable immunoregulatory environment to be maintained throughout pregnancy, promoting maternal immune tolerance in the developing semi-allogenic foetus. Furthermore, through binding immune cells, HLA-G expression also promotes spiral artery remodelling and fetal growth [51]. Contrastingly, there is a total lack of HLA-II expression in placental tissues, which is generally expressed constitutively on antigen-presenting cells [52]. This means the EVT cannot act as an antigen-presenting cell, preventing maternal T-cell alloreactivity against the paternally derived HLA antigens [53]. Altogether, this unique expression of HLA in the placenta is integral for fetal survival.

As previously discussed, an investigation by Brady et al., found no significant increase in anti-HLA antibodies in CHI [48]. However, an upregulation of HLA-II on the syncytiotrophoblast was observed in CHI placentas compared to healthy controls [48]. Albersammer et al. [18], also identified increased expression of CIITA a MHC class II transactivator and three HLA II genes in placental samples with CHI. Since HLA-II is crucial in activating maternal T helper cells, this abnormal HLA-II expression could initiate paternal antigen-specific T cell recognition and activation. In turn, resulting in B-cell activation and ultimately the production of anti-HLA antibodies, which have been identified in several CHI studies [11,22]. This finding could also provide an insight into why anti-HLA antibodies can be found in both women with CHI and as a normal response during healthy pregnancies. It is possible that anti-HLA antibodies have more relevance in CHI pathogenesis, if HLA-II is upregulated, in comparison to healthy pregnancies where restriction of HLA expression is under tight control.

A positive relationship was observed between the HLA-II expression in placentas with CHI and the extent of C4d deposition and maternal CD68+ macrophage infiltration [48]. Increased HLA-II could promote complement activation causing endothelial cell damage, disruption of fetal vascular function and placental inflammation through the recruitment of other inflammatory cells, as previously discussed

(Figure 3). Ultimately this could result in fetal demise and the adverse outcomes associated with CHI. Further investigation is required to determine if these CHI-associated, inflammatory features such as C4d deposition are localised to areas in the trophoblast where HLA-II is upregulated. This would provide crucial evidence of antibody binding.

10. Other Immunological Factors

As well as antibodies against HLA and inappropriate HLA-II expression there are several other immunological factors that could play a role in CHI pathology that have not yet been discussed in this review. Human platelet antigens (HPA) are alloantigens expressed on the platelet membrane, and maternal alloimunisation against paternally derived HPA can result in fetal and neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia (FNAIT). FNAIT is characterised by the destruction of fetal platelets when these maternal anti-platelet antibodies cross the placental barrier. In particular, the majority of FNAIT cases have been caused by antibodies against HPA-1a [54] and previous studies have found an association between chronic placental inflammation and FNAIT [55]. Crucially, a study by Nedberg et al. demonstrated a significant association between anti-HPA-1a antibodies and CHI [56]. This involved a systematic, histopathological examination of placentas from both HPA-1a immunised and nonimmunised HPA-1a negative women. The results showed 40.7% of the placentas from HPA-1a alloimmunised mothers displayed low grade CHI, in contrast to the control group which showed no instances of CHI [56]. These findings further support the hypothesis that an alloimmune response and specifically antibodies play a role in CHI pathophysiology.

Antiphospholipid antibodies are autoantibodies which target phospholipid-binding proteins and cause antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). They are associated with recurrent miscarriage, stillbirth and FGR, clinical presentations that overlap with the outcomes in a CHI pregnancy57, [58]. A range of placental lesions have been previously reported in aPL-positive women, however it’s still currently unclear which are common. One systematic review compared placentas from aPL-positive women with control women to better understand the associated features and lesions [57]. The results found villitis is not associated with placenta of aPL positive women, however, there has been insufficient evidence for association with intervillositis. Various characteristics were displayed commonly in aPL-positive women including C4d deposition and placental infarction. Furthermore, it’s thought that aPL associated obstetric morbidity is due to trophoblast dysfunction, excessive inflammation or thrombosis in the intervillous space [57]. One study by Stone et al. found increased macrophage infiltration in APS, a key characteristic of CHI [59]. Although the current evidence is limited, aPLs could contribute to placental dysfunction in CHI pregnancies by initiating thrombosis and inflammatory mechanisms in the intervillous space. Overall, although the specific mechanisms are still unknown, these findings further support the hypothesis that an alloimmune response plays a role in CHI pathophysiology.

11. Treatments

Current literature has shown there is a lack of sufficient treatments and standardised guidelines for CHI [10,60] exemplifying the severe drug drought that is present for women experiencing pregnancy related conditions. This may be explained by the rarity of CHI and considering it can only be diagnosed postpartum, there has been a lack of controlled clinical trials. Furthermore, ethical issues surrounding the use of women with previous pregnancy complications in placebo-controlled trials have also made it difficult to explore potential interventions. So far, no single treatment has shown clear effective benefits in treatment of CHI and studies have been limited in sample size and varying treatment regimens.

Existing therapeutic interventions include Aspirin, Prednisone, Prednisolone, low molecular weight Heparin (LMWH), Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and Adalimumab (

Table 1). These are used as standalone treatments or as combination therapy. This diversity in treatment emphasises the absence of a universally accepted protocol when it comes to treating CHI.

There is limited evidence supporting the use of current CHI treatments (

Table 1). A systematic review by Moar et al. highlighted this when exploring the results of treatment use on perinatal outcomes such as live birth, miscarriage and FGR outcomes [10]. Analysis of 38 pregnancies demonstrated that CHI-targeted treatment does not result in a significant increase in live birth rates. Additionally, the systemic review by Simula et al. also identified corresponding results [61]. Their findings identified no significant improvement in the live birth rate of those with pregnancies diagnosed with CHI who were treated with Acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), ASA + LMWH and ASA + LMWH + HCQ. These results were consistent with previous findings which also reported that interventions are unable to improve pregnancy outcomes or prevent recurrence [10,60]. A study by Contro et al. even suggested that current drug interventions may have a detrimental effect on perinatal outcome [60,62].

The evidence supporting the use of Adalimumab is limited to a very small number of case reports [63] by clinicians, again highlighting the disparity in CHI prevalence and treatment option awareness within the medical community. Mekinian et al. [63] reported a woman with CHI having experienced 12 early recurrent miscarriages being treated with Aspirin, Prednisone and Adalimumab 2 months before conception and up to 9 weeks gestation. She successfully delivered at 38 weeks gestation with no complications. This was also seen in another woman in the same case report. Though these findings are from a very small cohort they offer an insight into a potential avenue for CHI treatment as TNF-α agonists may prevent perivillous fibrin deposition [64], allowing the maintenance of nutrient and oxygen delivery to the foetus, preventing fetal demise [65]. As previously stated, treatment for CHI may be more successful if recognition and awareness of CHI was increased allowing success stories such as these to have a greater impact, resulting in the furthered use of potentially successful drugs such as Adalimumab.

12. Novel Therapies and Future Directions

As indicated, current treatments for CHI are inconsistent in their effectiveness and do not offer a curative solution to this enigmatic condition. Therefore, novel, effective therapies are necessary to treat CHI and prevent recurrence. Critically, the focus should be shifted onto preventing primary occurrence of CHI, as treating recurrence does not offer an alleviation to the fetal demise that occurs.

As previously discussed, CHI shares several histopathological similarities to allograft rejection. There is currently an ongoing trial aiming to repurpose Tacrolimus, a kidney anti-transplant rejection therapy, to treat women with recurrent placental inflammatory disorders, including CHI. The study aims to identify biomarkers and maternal antibodies that are associated with the conditions and capable of causing placental damage as well as whether Tacrolimus can limit the proposed destructive immune response in those affected [66]. Whilst previous research has found a weak strength of evidence for the use of Tacrolimus for CHI [10], exploring whether this drug can suppress the aggressive immune response in CHI could help improve the understanding and treatment of this condition. Moreover, the identification of biomarkers exclusively expressed in those at risk of developing CHI may provide an avenue for novel screening and treatment programmes, allowing prophylactic treatment.

With evidence for antibodies in CHI and their potential pathogenic nature, future diagnostic treatments should be aimed towards prenatal antibody testing in those that have been previously affected by CHI. The identification of the antibody anti-HPA-1a by Nederg et al. [56] paves the way and shapes these treatment decisions in CHI. However, although prenatal antibody screening would hopefully prevent the recurrence of CHI it would not allow an avenue for the impediment of its primary occurrence. Parental HLA screening could emerge as a potential future strategy for managing CHI. For instance, it has been identified that HLA-C and HLA-*07 mismatches are significantly increased in couples that have experienced recurrent miscarriages (3 or more) compared to controls [67], which is a prevalent outcome of CHI. This demonstrates a potential need for standardised HLA screening, as it could provide a valuable insight to the likelihood of HLA mismatches during pregnancy thereby driving primary CHI events.

Intravenous immunoglobulins are also implicated in the treatment of CHI with two case reports identifying their potential therapeutic use. Abisror et al. treated 4 patients who had at least four pregnancy losses with confirmed CHI for a minimum of one of the pregnancies [68]. Usual etiological screening following pregnancy loss was conducted on factors such as paternal karyotype, thrombophilia screening (anti phospholipid antibodies), blood glucose and auto immune test (antinuclear, anti-dsDNA, antiex-tractable nuclear antigen). Additionally, in 3 out of the 4 patients anti paternal HLA antibodies were present. Patients were either treated with intravenous immunoglobulins from the start of β Human chorionic gonadotropin (βHCG) positivity or from 20 weeks gestation. 3 out of the 4 pregnancies had live births at 36 and 39 weeks gestation, with one experiencing pregnancy lost at 15 weeks. Although small, this study has large implications for the treatment of CHI, specifically for cases that are Steroid and Hydroxychloroquine refractive. The presence of anti-paternal HLA antibodies in these participants and the following remediation of subsequent CHI pregnancies when using intravenous immunoglobulins provide further evidence for a pathogenic role of antibodies in CHI. Abdulghani et al. also identified similar results on a single patient case report with recurrent miscarriage and CHI confirmation. Intravenous immunoglobulin, Heparin and Aspirin treatment for her two subsequent pregnancies resulted in term pregnancies and normal placentas [69].

It must also be noted that although CHI is more readily diagnosed in the third trimester the immunological inflammation discussed is most prevalent in the first trimester. This is because the outcomes of CHI are encompassed by the Great Obstetric syndromes: fetal growth restriction, stillbirth and preterm labour. These are all as a result of a disruption to early processes in the first trimester [70] due to inadequate trophoblast invasion and spiral artery remodelling, therefore, affecting fetal blood supply, leading to a reduction in surface area for nutrient exchange resulting in growth reduction and potentially still birth [71,72]. Therefore, treatment options need to be designated to the pre conception and early gestational phases where these key angiogenic processes take place.

13. Ethics

CHI occurs across the globe with current evidence showing there is no significant association with a particular ethnic group [73]. Despite this, the majority of CHI cases are studied in white participants. Studies with adequate representation of diverse ethnic groups are necessary to reduce healthcare disparities. Without this, women with CHI from an underrepresented background may face worse pregnancy outcomes. The lack of diversity in research could also be impacted by the lack of awareness of CHI.

Given the rarity of this disorder, CHI remains widely unknown and under-reported [7]. Its incidence is reportedly highest in the first trimester at 4.4 to 9.6 in 1000 miscarriages, but only 0.6 in 1000 cases are diagnosed in the second and third trimester [4,5,6]. The lack of awareness around this disorder contributes to its underdiagnosis and poor understanding of CHI pathology, which subsequently impacts treatment and management of patients with CHI pregnancies. Currently, obstetricians do not routinely investigate after a single miscarriage, rather after two or more cases, guidelines which could be contributing to the underdiagnosis of CHI. It’s been suggested that patients with specific risk factors should be considered for histopathological examination of the placenta to improve diagnosis [7]. This includes factors such as previous CHI on histopathology, recurrent pregnancy losses, previous poor obstetric outcomes and a history of autoimmune conditions and hypertension [7]. It’s crucial that awareness of this disorder is increased in order to improve diagnosis and pregnancy outcomes in women from all ethnic backgrounds.

14. Limitations

A complete understanding of the mechanisms underpinning CHI remains unknown. Given the rarity of this disease, the various studies explored in this review are significantly limited by the small sample sizes of affected women available. The reports of anti-HLA antibodies presence in CHI-affected pregnancies vary within the existing literature, which limits understanding of their role in this disease. Despite there being individual case reports of elevated maternal anti-HLA antibodies [11,22], other studies have found levels to be comparable to healthy controls [16]. Additionally, since the presence of low levels of anti-HLA antibodies is a normal physiological response that can occur during pregnancy, it is difficult to confirm its clinical relevance. Since diagnosis is made retrospectively, research analysing plasma to identify maternal antibodies is limited to subsequent pregnancies. At this point many women have already received immunosuppressive treatment and so it’s possible that any anti-HLA antibodies which were present previously have been reduced as a result of medication. Additionally, due to the ethical issues associated with including women with a history of multiple poor obstetric outcomes in randomised placebo-controlled interventions, it would be difficult to explore antibody levels in an unmedicated context. In order to improve understanding, management and treatment of this disease, there must be multicentre collaboration to increase the sample size of affected women in these research studies.

15. Discussion

CHI is a devastating condition that is lacking sufficient research and representation in the medical community. The current view is that it is driven by an abnormal maternal immunological process targeted at the foetus, comparable to that of an allograft rejection.

Although the exact immunological trigger is still unknown the presence of the diagnostic features; maternal histiocytes and perivillous fibrin deposition in the intervillous space provides the basis for a pathological mechanism that involves the impairment of nutrient perfusion and oxygen delivery to the foetus. This is thought to coincide with the recruitment and activation of additional immune mediators, such as CD8+ T cells and the newly identified up regulation of the inflammasome pathway. Undoubtedly, these cellular influxes in the intervillous space exacerbate inflammation, furthering fetal demise. However, it can be hypothesised that the processes discussed may only each play small individual roles in CHI pathogenesis, contributing to a greater picture of inflammation that is driven by an unidentified larger scale immune process, such as the presence of anti-HLA antibodies.

New literature consistently indicates that this process of maternal inflammation may be driven by and perhaps initiated by paternal antigens present during pregnancy. It appears clear that anti-HLA antibodies are relevant in the disease pathogenesis, perhaps more so in the context of upregulated HLA-II in CHI affected pregnancies. It’s possible this abnormal HLA-II expression initiates paternal antigen-specific T cell activation, promotes inflammatory features such as C4d deposition causing endothelial cell damage and placental inflammation ultimately resulting in the adverse pregnancy outcomes associated with CHI.

Whilst the current literature provides some insight into the pathogenesis of CHI, there is a need for further evidence confirming the specific role and mechanisms anti-HLA antibodies have within the disorder. Critically, evidence of antibody binding at the maternal-fetal interface is still lacking, and therefore, the direct role anti-HLA antibodies play in CHI pathogenesis remains unclear. Future research should focus on establishing this, which would in turn shape curative and, crucially, preventative treatments for CHI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MBR, IPW, K.B, MTMM and PS; methodology, MBR, IPW & K.B; formal analysis, MBR, IPW & K.B investigation, MBR, IPW & K.B; data curation, MBR, IPW & K.B; writing original draft preparation, MBR, IPW & K.B; writing—review and editing, MTMM, GL, KHN, and PS; visualization, MBR, IPW; supervision, MTMM and PS; funding acquisition, KHN; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Fetal Medicine Foundation, Charity Number: 1037116 The APC was funded by grant of The Fetal Medicine Foundation, Charity Number: 1037116.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Acknowledgments

not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABMR |

Antibody-Mediated Rejection |

| aPL |

Antiphospholipid Antibodies |

| APS |

Antiphospholipid Syndrome |

| ASA |

Acetylsalicylic Acid |

| βHCG |

Beta-Human Chorionic Gonadotropin |

| CD |

Cluster of Differentiation |

| CHI |

Chronic Histiocytic Intervillositis |

| CIUE |

Chronic Intervillositis of Unknown Etiology |

| CTLpf |

Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Precursor Frequency |

| DAMP |

Damage-Associated Molecular Pattern |

| DSA |

Donor-Specific Antibody |

| EVT |

Extravillous Trophoblast |

| FGR |

Fetal Growth Restriction |

| FNAIT |

Fetal and Neonatal Alloimmune Thrombocytopenia |

| HCQ |

Hydroxychloroquine |

| HLA |

Human Leukocyte Antigen |

| HPA |

Human Platelet Antigen |

| IgG |

Immunoglobulin G |

| IgM |

Immunoglobulin M |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| IVIg |

Intravenous Immunoglobulin |

| LMWH |

Low Molecular Weight Heparin |

| MAC |

Membrane Attack Complex |

| MHC |

Major Histocompatibility Complex |

| NK |

Natural Killer (cells) |

| PBMC |

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| PD-1 |

Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| TCR |

T Cell Receptor |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| VUE |

Villitis of Unknown Etiology |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).