Submitted:

29 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

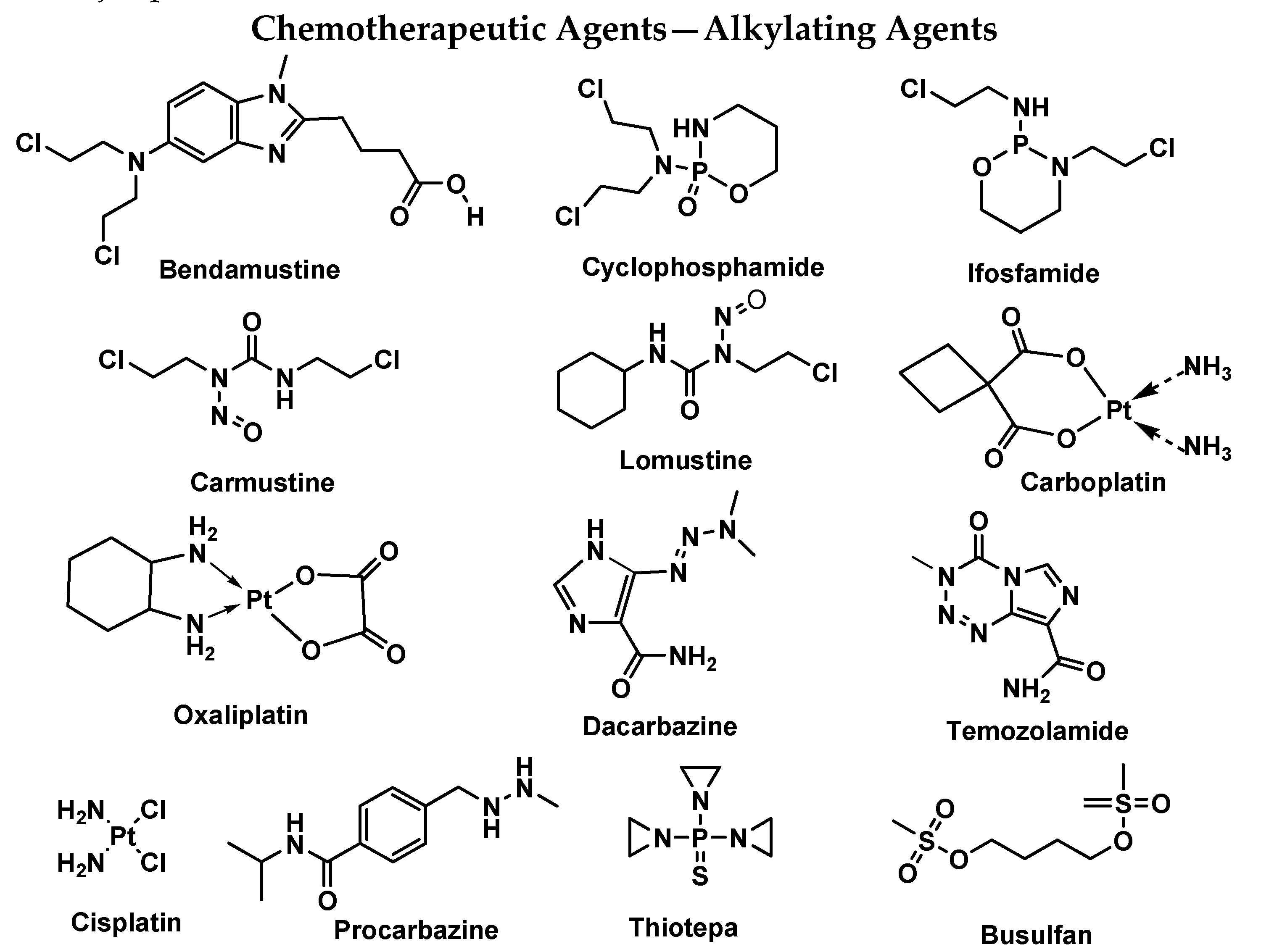

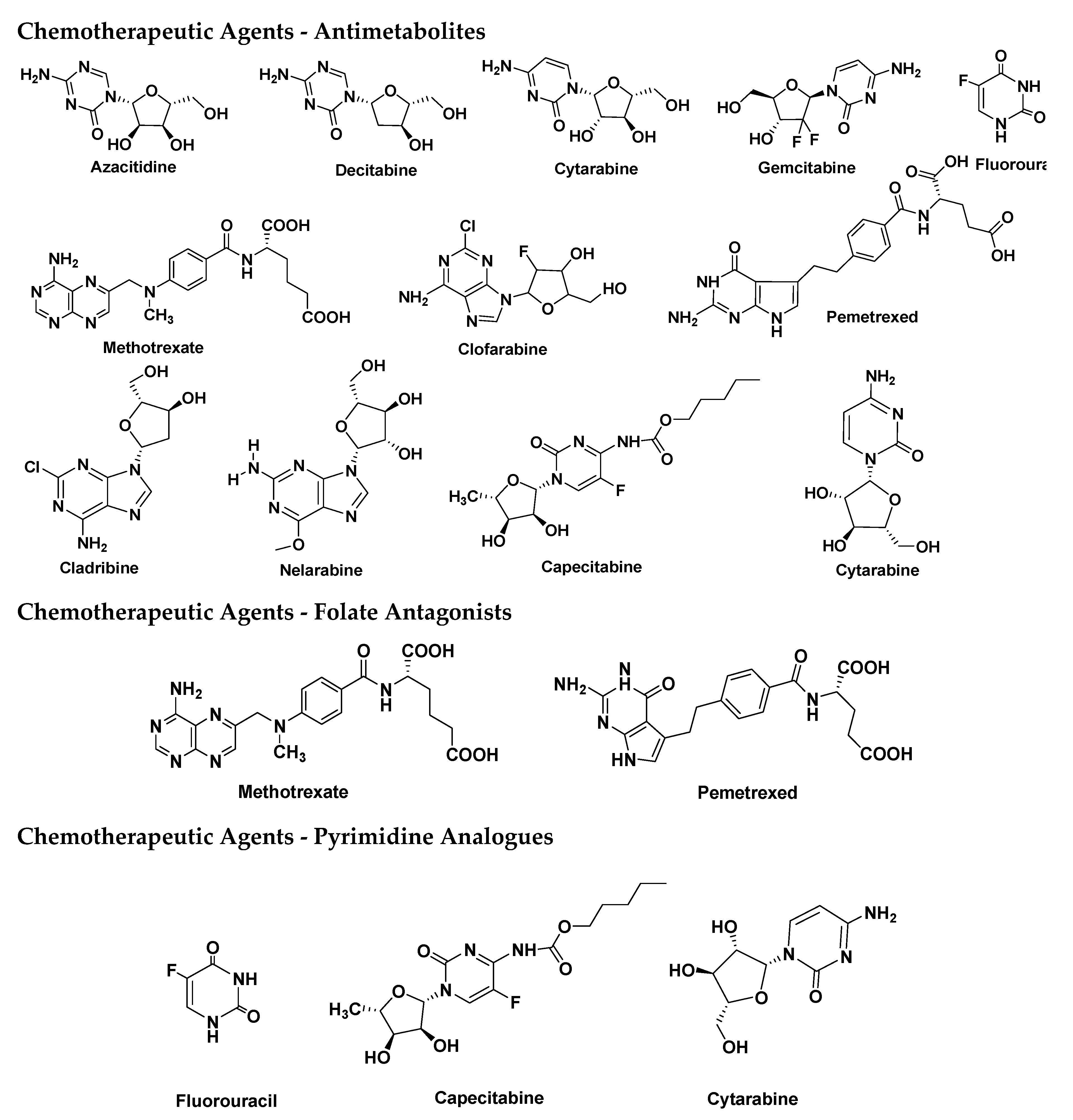

2. Overview of Traditional Cancer Treatments

Exploring Conventional Cancer Therapies: Mechanisms and Limitations

| Radiation Type | Mechanism of Action | Examples | Indications | Toxicities | Year | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT) | Uses high-energy X-rays or protons to damage DNA and kill cancer cells | 3D Conformal Radiation Therapy (3D-CRT), Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT), Proton Beam Therapy | Breast, lung, prostate, brain, head and neck cancers | Skin irritation, Fatigue, Nausea, Fibrosis, Secondary malignancies | 20th century – Present | [19] |

| Brachytherapy | Internal radiation therapy where a radioactive source is placed near the tumor | Low-dose rate (LDR), High-dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy | Prostate, cervical, breast, and endometrial cancers | Localized swelling, Tissue necrosis, Urinary dysfunction | 20th century – Present | [20] |

| Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) | Delivers high doses of radiation with pinpoint accuracy, sparing normal tissues | CyberKnife, Gamma Knife, LINAC-based SBRT | Brain, lung, liver, and spine cancers | Fatigue, Local tissue damage, Radiation necrosis | 21st century | [21] |

Unravelling the Mechanisms of Traditional Cancer Treatments.

3. Targeted Therapy

Biological Markers in Targeted Cancer Therapy Across Various Cancer Types

- a)

- Immunotherapy

Types of Immunotherapy in Cancer Treatment

- Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy

- b.

- Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)

ADCs in Clinical Development and Approved ADC Drugs

Evolution of Immunotherapy: Milestones in Cancer Treatment

3. Combining Immunotherapy with Traditional Treatments

- i.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICBs)

- ii.

- Integrating Immunotherapy with Traditional Cancer Treatments

- iii.

- Cancers Treated with Combined Therapies

Challenges in Combining Immunotherapy and Traditional Treatments

- Key Clinical Trials in Combined Cancer Therapy

Comparing Combined vs. Traditional Cancer Treatments

Future Cancer Treatments: Lessons from Clinical Trials

The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)

EORTC’s Contributions to Cancer Research and Treatment

2. Future Directions and Research

Emerging Trends in Cancer Treatment Integration

Integration of Immunotherapy and Traditional Treatments for Cancer

Resistance and Its Challenging

The Challenges and Complexities of Determining Optimal Dosing, Timing, and Sequencing

Adjusting mRNA Medicine Dosage Pharmacokinetics

What Strategies Can Future Research Employ to Address Existing Challenges

Potential Impact of This Combined Approach on Cancer Survival Rates

3. Discussion

4. Limitations

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Material

Acknowledgements

Competing Interests

List of Abbreviations Section

References

- Ferlay, J. , Soerjomataram, I., Dikshit, R., Eser, S., Mathers, C., Rebelo, M.,... & Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vogelstein, B. , & Kinzler, K.W. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nature Medicine 2004, 10, 789–799. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society. (2022). What causes cancer? Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-causes.html.

- Hanahan, D. , & Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Siegel, R. L. , Miller, K. D., & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, L. A. , Bray, F. , Siegel, R. L., Ferlay, J., Lortet-Tieulent, J., & Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 2015, 65, 87–108. [Google Scholar]

- Longley, D. B. , & Johnston, P. G. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance. The Journal of Pathology 2005, 205, 275–292. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, C. J. , & Dinan, T.G. Tumor heterogeneity—A ‘contemporary concept’ founded on historical insights and predictions. Cancer Research 2011, 71, 5373–5377. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Institute. (2022). Types of cancer treatment. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types.

- Pardoll, D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Cancer 2012, 12, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardis, E.R. Next-generation DNA sequencing methods. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 2008, 9, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, F. R. , & Varella-Garcia, M.Bunn Jr PA, Di Maria MV, Veve R, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor in non-small-cell lung carcinomas: correlation between gene copy number and protein expression and impact on prognosis. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2009, 27, 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. (2022). ClinicalTrials.gov. Retrieved from https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

- Lungu, C. , Trifanescu, O. R., Petre, I., Bogdan, M. A., & Alexa-Stratulat, T. Exploring Conventional Cancer Therapies: An In-Depth Look at Traditional Treatment Approaches. Journal of Interdisciplinary Medicine 2019, 4, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Chen, X., Tian, B., Liu, J., Yang, L., Zeng, L., & Chen, T. Development and evaluation of a paclitaxel-loaded recombinant polypeptide nanoparticle for the treatment of breast cancer. Biomaterials Science 2013, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Chabner, B. A. , & Roberts Jr, T.G. Chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2005, 5, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Longley, D. B. , Harkin, D. P., & Johnston, P. G. 5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nature Reviews Cancer 2003, 3, 330–338. [Google Scholar]

- Dumontet, C. , & Jordan, M.A. Microtubule-binding agents: a dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2010, 9, 790–803. [Google Scholar]

- Gewirtz, D.A. A critical evaluation of the mechanisms of action proposed for the antitumor effects of the anthracycline antibiotics adriamycin and daunorubicin. Biochemical Pharmacology 1999, 57, 727–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, G. J. , & Van Groeningen, C.J. Thymidylate synthase: a target for combination therapy and determinant of chemotherapeutic response in colorectal cancer. Oncology 2000, 58 (Suppl. 1), 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bentzen, S. M. , & Trotti III, A. Evaluation of early and late toxicities in chemoradiation trials. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2007, 25, 4096–4103. [Google Scholar]

- Saha, A. , Acharya, S., & Chakraborty, J. Pharmacokinetics of Bendamustine Hydrochloride in Human Plasma. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 2011, 10, 497–501. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J. E. , Hole, P. S., & Marley, S. B. Transcriptional Regulation of Myeloid Enhancer Factor-2 is Involved in Myeloid Gene Expression in Ba/F3 Cells. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 2009, 108, 647–656. [Google Scholar]

- Skowronek, J. Radiation Therapy in Breast Cancer: A Traditional or Individual Treatment Method? A Review. Clinical Oncology 2017, 2, 1257. [Google Scholar]

- Abbas, S. M. , & Rehman, A. Overview of breast cancer treatment modalities. Saudi Medical Journal 2018, 39, 511–519. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya, J. J. , Timmerman, J. M., & Law, S. (2020). Immunotherapy. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- American Cancer Society. (n.d.). How Targeted Therapies Are Used to Treat Cancer. Retrieved March 16, 2024, from https://www.cancer.org.

- National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). Targeted Therapy for Cancer. Retrieved March 16, 2024, from https://www.cancer.gov.

- American Cancer Society. (n.d.). Targeted Therapy. Retrieved March 16, 2024, from https://www.cancer.org.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information. (n.d.). Targeted cancer therapies. Retrieved March 16, 2024, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9842142/.

- Min, HY., Lee, HY. Molecular targeted therapy for anticancer treatment. Exp Mol Med 54, 1670–1694 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, Batur P, Lin K, Kansagara DL; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians; Commission on Health of the Public and Science of the American Academy of Family Physicians; Cooney TG, Forciea MA, Crandall CJ, Fitterman N, Hicks LA, Horwitch C, Maroto M, McLean RM, Mustafa RA, Tufte J, Vijan S, Williams JW Jr. Nonpharmacologic and Pharmacologic Management of Acute Pain From Non-Low Back, Musculoskeletal Injuries in Adults: A Clinical Guideline From the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020, 173, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayers EW, Barrett T, Benson DA, Bolton E, Bryant SH, Canese K, Chetvernin V, Church DM, Dicuccio M, Federhen S, Feolo M, Fingerman IM, Geer LY, Helmberg W, Kapustin Y, Krasnov S, Landsman D, Lipman DJ, Lu Z, Madden TL, Madej T, Maglott DR, Marchler-Bauer A, Miller V, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Ostell J, Panchenko A, Phan L, Pruitt KD, Schuler GD, Sequeira E, Sherry ST, Shumway M, Sirotkin K, Slotta D, Souvorov A, Starchenko G, Tatusova TA, Wagner L, Wang Y, Wilbur WJ, Yaschenko E, Ye J. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, D13–25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Han, J. Y. , & Lee, S.H. EGFR Mutation and Resistance Mechanisms in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2022, 17, 192–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gajewski F Thomas(2012) Cancer immunotherapy, 2012 vol 6 Issue 2 PP 242-250.

- Oliveira, G. , Wu, C.J. Dynamics and specificities of T cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer, 2023; 23, 295–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birrer, M. J. , Konstantinopoulos, P. A., Matulonis, U. A., and Horowitz, N. S. Exploring the Role of Farletuzumab in Second-line Therapy of Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer: Subgroup Analyses of the Phase III Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, OVA-301 Study. Oncologist 2019, 24, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S. , Bhattacharya, A., Doughty, B., Lipton, S. A., and Ratan, R.R. Overcoming Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T Cell Therapy Challenges in Glioblastoma (GBM). Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 211. [Google Scholar]

- Staudacher HM, Lomer MCE, Farquharson FM, Louis P, Fava F, Franciosi E, Scholz M, Tuohy KM, Lindsay JO, Irving PM, Whelan K. A Diet Low in FODMAPs Reduces Symptoms in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome and A Probiotic Restores Bifidobacterium Species: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2017, 153, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y. , Ho, M. Antibody–Drug Conjugates for Cancer Therapy: Successes and Challenges. Bio Drugs 2022, 36, 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson, S. , Yu, J., Lenarduzzi, M., and Joseph, J. Translational Immunotherapy in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 3363. [Google Scholar]

- Feola S, Russo S, Ylösmäki E, Cerullo V. Oncolytic ImmunoViroTherapy: A long history of crosstalk between viruses and immune system for cancer treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2022, 236, 108103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldman, A.D. , Fritz, J.M. & Lenardo, M.J. A guide to cancer immunotherapy: from T cell basic science to clinical practice. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Wagstaff J, Schadendorf D, Ferrucci PF, Smylie M, Dummer R, Hill A, Hogg D, Haanen J, Carlino MS, Bechter O, Maio M, Marquez-Rodas I, Guidoboni M, McArthur G, Lebbé C, Ascierto PA, Long GV, Cebon J, Sosman J, Postow MA, Callahan MK, Walker D, Rollin L, Bhore R, Hodi FS, Larkin J. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 1: 5;377(14), 1345; . Epub 2017 Sep 11. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2018 Nov 29;379(22):2185. PMCID: PMC5706778. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, Esteban E, Felip E, De Angelis F, Domine M, Clingan P, Hochmair MJ, Powell SF, Cheng SY, Bischoff HG, Peled N, Grossi F, Jennens RR, Reck M, Hui R, Garon EB, Boyer M, Rubio-Viqueira B, Novello S, Kurata T, Gray JE, Vida J, Wei Z, Yang J, Raftopoulos H, Pietanza MC, Garassino MC; KEYNOTE-189 Investigators. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 31;378(22):2078-2092. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Formenti SC, Rudqvist NP, Golden E, Cooper B, Wennerberg E, Lhuillier C, Vanpouille-Box C, Friedman K, Ferrari de Andrade L, Wucherpfennig KW, Heguy A, Imai N, Gnjatic S, Emerson RO, Zhou XK, Zhang T, Chachoua A, Demaria S. Radiotherapy induces responses of lung cancer to CTLA-4 blockade. Nat Med. 2018 Dec;24(12):1845-1851. . Epub 2018 Nov 5. PMCID: PMC6286242. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbari, C. , Fontanesi, S., & Masiello, D. Immunotherapy and Its Potential Role in the Chemotherapy/Radiotherapy Combination Approach in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. A Review. Cancers 2020, 12, 1187. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, V. , Nogueras-Gonzalez, G., and Jain, A. Impact of Next-generation Sequencing on the Management of Prostate Cancer. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2021, 39, 440–451. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, P. A. , Hodi, F. S., and Buchbinder, E.I. Inhibition of Immune Checkpoints and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor as Combination Therapy for Metastatic Melanoma: An Overview of the Ongoing Clinical Experience. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2017, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney, K. M. , Atkins, M. B., and Tykodi, S.S. Rationale for Combining Therapies in Melanoma with Special Emphasis on Nivolumab and Ipilimumab. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2015, 13(5S), 512–520. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. H. , Lin, F., Lu, J., Wang, Y. L., Xu, R. H., and Wei, Y. Sequential Therapies for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: A Review Focused on Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Role of Biomarkers. Journal of Kidney Cancer and VHL 2018, 5, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V. , Rees, J., and Brookes, P. Oncology-Pharmaceutical Value in Cancer Care: Perspectives from the Indian Cancer Patient Ecosystem. Future Oncology 2018, 14, 3257–3270. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-rustum, N. R. , and Sonoda, Y. Current Management Strategies for Ovarian Cancer. Drugs 2013, 73, 855–862. [Google Scholar]

- Devita, V. T. , and Chu, E. A History of Cancer Chemotherapy. Cancer Research 2008, 68, 8643–8653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabner, B. A. , and Roberts, T.G. Timeline: Chemotherapy and the War on Cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2005, 5, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalaney, W. T. , and Wiederhold, J.P. Advances in External Beam Radiation Therapy for Prostate Cancer. Oncology 2005, 3, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar]

- Baskar, R. , Lee, K. A., Yeo, R., and Yeoh, K.W. Cancer and Radiation Therapy: Current Advances and Future Directions. International Journal of Medical Sciences 2012, 9, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, V. C. The 38th David A. Karnofsky Lecture: The Paradoxical Actions of Estrogen in Breast Cancer – Survival or Death? Journal of Clinical Oncology 2003, 20, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, M.J. Predictive Markers in Breast and Other Cancers: A Review. Clinical Chemistry 2005, 5, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P. , and Allison, J. P. The Future of Immune Checkpoint Therapy. Science 2015, 348, 56–61. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. , and Mcllman, D. R. CTLA-4 Blockade in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2017, 8, a009522. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, G. , and Milstein, C. Continuous Cultures of Fused Cells Secreting Antibody of Predefined Specificity. Nature 1975, 256, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, JM. Antibodies to watch in 2016. MAbs. 2016;8(2):197-204. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lambert JM, Chari RV. Ado-trastuzumab Emtansine (T-DM1): an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) for HER2-positive breast cancer. J Med Chem.014 Aug 28;57(16):6949-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari S, Raj S, Babu MA, Bhatti GK, Bhatti JS. Antibody-drug conjugates in cancer therapy: innovations, challenges, and future directions. Arch Pharm Res. 2024 Jan;47(1):40-65. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumura Y, Maeda H. A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res. 1986 Dec;46(12 Pt 1):6387-92. [PubMed]

- Wilhelm C, Harrison OJ, Schmitt V, Pelletier M, Spencer SP, Urban JF Jr, Ploch M, Ramalingam TR, Siegel RM, Belkaid Y. Critical role of fatty acid metabolism in ILC2-mediated barrier protection during malnutrition and helminth infection. J Exp Med. 1: 25;213(8), 1409. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mercieca-bebber, R. , Palmer, M. J., Brundage, M., Calvert, M., Stockler, M. R., King, M. T., & Group, E. T. Design, implementation, and reporting strategies to reduce the instance and impact of missing patient-reported outcome (PRO) data: A systematic review. Trials 2018, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- George DJ, Lee CH, Heng D. New approaches to first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 1: 11;13, 1758. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gatta, G. , Capocaccia, R., Coleman, M. P., Ries, L. A. G., Berrino, F., Pastore, G., & Sant, M. Toward a comparison of survival in American and European cancer patients. Cancer 2011, 83, 1632–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Willemze, R. , Suciu, S., Meloni, G., Labar, B., Marie-therese, R., Solbu, G.,... Pier Luigi, Z. High-Dose Cytarabine with or without Continuous-Infusion Daunorubicin in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 376, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- De-Pauw, B. E. , Boeckh, M., Brindle, R., Fields, B., Winston, D. J., Vercellotti, G. M., & Rubin, R. Consensus Guidelines for the Use of Antimicrobial Agents in Neutropenic Patients with Cancer. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2008, 34, 730–751. [Google Scholar]

- Forde, C. S. , & Breakey, V. S. Single dose versus two dose pneumococcal vaccination in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2023, 35, 1069–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Gillian, C. , Coats, T. J., & Gurney, S. ‘‘Going home’: Health professionals’ perspectives on early discharge following mild traumatic brain injury in adults: A qualitative study. Emergency Medicine Journal 2020, 22, 376–383. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Segura, A. , Nehme, J., & Demaria, M. Hallmarks of Cellular Senescence. Trends in Cell Biology 2020, 28, 436–453. [Google Scholar]

- Kandi, V. , Demirjian, A., & Reppucci, F. Diagnostic testing of respiratory viruses in bronchoalveolar lavage specimens from immunocompromised patients: An audit of 10 years of activity in a teaching hospital. European Journal of Microbiology and Immunology 2023, 13, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Eman, S. , Hatem, H., & Mohamed, S. Efficacy and safety of long-acting beta-agonists (LABA/LAMA) versus inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) maintenance therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. European Respiratory Journal 2024, 17, 294–301. [Google Scholar]

- House, R. J., & Podsakoff, P. M. (1994). Leadership effectiveness: Past perspectives and future directions for research. In J. Greenberg (Ed.), Organizational behavior: The state of the science (pp. 45–82). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Venkatesh, V. “Where to go from Here? Thoughts on Future Directions for Research on Venkatesh, V.Individual-level Technology Adoption with a focus on Decision Making,” Decision Sciences (37:4), 2006, 497-518.

- EDWARDS, P.J. and BOWEN, P.A. (1998), “Risk and risk management in construction: a review and future directions for research”, Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, Vol. 5 No. 4, pp. 339–349. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. , & Chen, L. Cutting Edge: Nanomaterials and Nanosystems for Cancer Immunotherapy. Advanced Functional Materials 2018, 28, 1801850. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri, D. , Mitra, S., & Goswami, S. Immunotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Current Breast Cancer Reports 2023, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chehelgerdi, M. , & Chehelgerdi, N. Diagnostic performance of [18F]FDG PET/CT for the detection of bone marrow involvement in pediatric and adult lymphomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2023, 50, 481–491. [Google Scholar]

- Debela DT, Muzazu SG, Heraro KD, Ndalama MT, Mesele BW, Haile DC, Kitui SK, Manyazewal T. New approaches and procedures for cancer treatment: Current perspectives. SAGE Open Med. 2021 Aug 12;9:20503121211034366. 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vasileiou, M.; Papageorgiou, S.; Nguyen, N.P. Current Advancements and Future Perspectives of Immunotherapy in Breast Cancer Treatment. Immuno 2023, 3, 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qizhi Fan1†Yiyan Wang1†Jun Cheng1Boyu Pan2Xiaofang Zang1*Renfeng Liu1*Youwen Deng Front. Immunol., 02 April 2024 Sec. Cancer Immunity and Immunotherapy, Volume 15 - 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. , Liu, Q., & Yang, J. Modified mRNA-LNP vaccines: advances and challenges in cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Liu B, Zhang Z. Accelerating the understanding of cancer biology through the lens of genomics. Cell. 2023 Apr 13;186(8):1755-1771. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ari Rosenberg, Aditya Juloori, Nishant Agrawal, John Cursio, Michael J. Jelinek, Nicole Cipriani, MarkW. Lingen, Rachelle Wolk, Jeffrey Chin, Melody Jones, Daniel Ginat, Olga Pasternak-Wise, Zhen Gooi, Elizabeth A. Blair, Alexander T. Pearson, Daniel J. Haraf, and Everett E. Vokes, Neoadjuvant nivolumab, paclitaxel, and carboplatin followed by response-stratified chemoradiation in locoregionally advanced HPV negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC): The DEPEND trial.. JCO 41, 6007-6007(2023). [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, A. , Al-Jasmi, F., & Kumar, R. Combining molecularly targeted therapeutics with immune checkpoint inhibitors: emerging strategies in cancer therapy. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, R. J. , & Gross, C. Hypoxia: An Observer of the Radiation Resistance the HIF-1 Hypothesis. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics 2004, 58, 862–873. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin, J. L. , & Bierman, A. Future Directions in Elder Mistreatment Research. JAMA Internal Medicine 2013, 173, 276–277. [Google Scholar]

- Cilesiz, S. Understanding Teacher Candidates’ Motivation to Learn in Online Learning Environments: The Role of Personal Goals and Self-Efficacy. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education 2011, 19, 6–22. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S. , & Ekar, N. Assessment of Anti-Diabetic Activity of Anti-Diabetic Activity of Asphodelus tenuifolius Rhizomes in Diabetic Rats. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 1994, 56, 65–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P. , Hu-Lieskovan, S., Wargo, J.A., Ribas, A. Primary, Adaptive, and Acquired Resistance to Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell 2017, 168, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L. , Chan, T.A., Kroemer, G., Wolchok, J.D., Lopez-Soto, A. The hallmarks of successful anticancer immunotherapy. Science Translational Medicine 2018, 10, eaat7807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.S. , Mellman, I. Elements of cancer immunity and the cancer-immune set point. Nature 2017, 541, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postow, M.A. , Sidlow, R., Hellmann, M.D. Immune-Related Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 378, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. , Zhou, S., Yang, F., Qi, X., Wang, X., Guan, X. Treatment-Related Adverse Events of PD-1 and PD-L1 Inhibitors in Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncology 2021, 7, 96–104. [Google Scholar]

- Tolcher, A.W. Combining molecularly targeted agents and immunotherapy: Where are we now and where are we going? American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book 2020, 40, 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Hare, J.I. , Lammers, T., Ashford, M.B., Puri, S., Storm, G., Barry, S.T. Challenges and strategies in anti-cancer nanomedicine development: An industry perspective. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2017, 108, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccardi F, Dal Bo M, Macor P, Toffoli G. A comprehensive overview on antibody-drug conjugates: from the conceptualization to cancer therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2023 Sep 18;14:1274088. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| ADC | Target | Indication(s) | Initial Approval Year | Marketed Company |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemtuzumab ozogamicin | CD33 | AML | 2000 | Pfizer |

| Brentuximab vedotin | CD30 | Hodgkin lymphoma, ALCL | 2011 | Seagen |

| Inotuzumab ozogamicin | CD22 | B-ALL | 2017 | Pfizer |

| Motetumomab pasudotox | CD22 | Hairy cell leukemia | 2018 | AstraZeneca |

| Polatuzumab vedotin | CD79b | DLBCL | 2019 | Roche |

| Treatment Method | Discovery | Changes Over Time | Unfilled Gaps | Major Side Effects | Mechanisms of Resistance | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery | Ancient times | Technological advancements, minimally invasive procedures | Inability to remove metastasized cancer cells | Pain, infection, bleeding | Metastasis, incomplete resection, tumor heterogeneity | [51,52] |

| Chemotherapy | 1940s | Development of targeted therapies, combination regimens | Resistance to drugs, toxicity to healthy cells | Myelosuppression, nausea, hair loss | Drug efflux pumps, altered drug targets, DNA repair mechanisms | [54,55] |

| Radiation Therapy | Late 19th century | Improved precision, use of different radiation modalities | Radiation resistance, damage to surrounding tissues | Fatigue, skin changes, radiation dermatitis | DNA repair mechanisms, hypoxia, repopulation of tumor cells | [56,57] |

| Hormone Therapy | Late 19th century | Introduction of newer hormone receptor-targeted agents | Development of hormone-resistant tumors | Hot flashes, osteoporosis, fatigue | Alterations in hormone receptors, downstream signaling pathways | [58,59] |

| Immunotherapy | Late 19th century | Emergence of immune checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T therapy | Limited efficacy in certain cancer types, autoimmune reactions | Immune-related adverse events | Immune evasion, tumor microenvironment modulation | [60,61] |

| Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) | 1970s | Development of humanized and fully human mAbs | Limited penetration into solid tumors, immune-related adverse events | Infusion reactions, cytokine release syndrome | Down regulation of target antigen, immune escape mechanisms | [62] |

| Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) | 1980s | Refinement of linker and payload technologies | Heterogeneous expression of target antigen, payload resistance | Cytopenias, infusion reactions, cardiotoxicity | Antigen loss, internalization of ADCs, drug efflux mechanisms [65] | [63,64] |

| Precision Drug Systems (PDS) | 2000s | Advancements in nanotechnology, targeted drug delivery | Limited delivery to tumor sites, off-target effects | Infusion reactions, organ toxicities | Clearance by reticuloendothelial system, poor tumor penetration | [65,66,67] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).