Introduction

Copper-induced cell death, also known as “cuproptosis,” is increasingly recognized as a significant process in the pathogenesis and progression of various diseases and pathological conditions, such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, and heart failure [

1,

2]. The mechanism of cuproptosis involves the disruption of copper homeostasis, leading to the accumulation of copper ions within cells, which can bind to mitochondrial proteins and cause proteotoxic stress-mediated cell death [

3,

4]. In ischemic conditions, such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, copper ions can exacerbate tissue damage by increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inducing inflammation [

5]. The findings on cuproptosis provide new insights into the understanding of systemic diseases and injuries, as well as potential therapeutic strategies for targeted treatments of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Parkinson’s disease [

3,

6]. An increasing number of studies have revealed the involvement of cuproptosis in ischemic stroke [

7,

8,

9].

Edaravone (EDA) is a free radical scavenger with neuroprotective and antioxidant properties, used to delay the progression of neurological disorders such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and cerebral ischemia [

10,

11]. The mechanism of EDA involves scavenging reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are implicated in various ischemic diseases [

12]. EDA is thought to mediate therapeutic effects via its antioxidant properties, inhibiting lipid peroxidation, suppressing endothelial cell damage induced by lipid peroxides, and scavenging free radicals, which may lead to neuroprotective effects [

13,

14]. Besides, the EDA is also under investigation for disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease, neuropathic pain, and ischemia-induced nerve injury [

15,

16]. In current study, we investigated the effects of EDA on ischemic stroke and explored whether cuproptosis is involved in this process. We observed that EDA treatment alleviated the neuron damage in vitro and in vivo, simultaneously repressed the cuproptosis via regulating the NF-κΒ signaling.

Materials and Methods

Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion (MCAO) Model

C57BL/6 mice, weighing approximately 20 grams, were procured from the Vital River Laboratory in Beijing, China, and housed in a standard environmental setting. Mice were randomized to sham and model group. Then, 4% isoflurane was utilized to induce anesthesia in rats with ischemic stroke (IS), and anesthesia was sustained with 1.5% isoflurane. A 0.36 mm silicon-coated monofilament suture (Catalog No. 2636A4, Beijing Cinontech Co. Ltd., China) was inserted through the internal carotid artery to occlude the left middle cerebral artery. Rats in the sham group underwent a similar surgical procedure without the arterial obstruction. After a 2-hour period of ischemia, the suture was removed to allow for reperfusion. The treatment was initiated 6 hours following the reperfusion period. Specifically, Edaravone (2 mg) and elesclomol (Ele, 2 mg) were delivered intracerebroventricularly at a volume of 5 µl, administered at a rate of 1 µl per minute. The entire experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of XuZhou Central Hospital, ensuring ethical standards and procedures were followed throughout the study.

Neurological Function Assessment

The Modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS) test was conducted to assess neurological deficits in subjects 14 days following surgical procedures. Animals underwent a training period for these tests for three days prior to the ischemia and reperfusion event. Data collection commenced the day after the training session. Subsequently, on the following day, the mice were subjected to the ischemia and reperfusion procedure.

2,3,5-Triphenyl Tetrazolium Chloride (TTC)

The TCC staining method was employed to assess the infarct size in MCAO model at day 14 post-surgery. The brain tissue was sectioned into 2-mm-thick slices starting from the frontal pole. Following overnight fixation in 4% paraformaldehyde, the sections were incubated with a 2% TTC solution (Sigma, USA) at 37 °C in a dark environment for 10 minutes. The resulting unstained, pale regions in the sections indicate the areas of cerebral infarction. The images were then photographed.

Neuron Culture

The neuron PC12 cell line was brought from Procell (Wuhan, China), cultured in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM) that added with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Thermo, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma, USA). The cells were maintained in an incubator set at 37°C with an atmosphere of 5% CO2. EDA and Ele were administrated at 5 µM and 10 µM, respectively. After incubation for 24 h, cells were collected for following experiments.

Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation (OGD) Model

PC12 cells were induced by an OGD-R model to mimic the ischemia condition in vitro.

In short, neurons were placed in serum-free and glucose-deprived culture medium, placed in an anaerobic chamber that filled with 95% nitrogen and 5% CO2 for 6 hours. After that, cells were incubated in the complete culture medium in a normal 37°C incubator.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (Beyotime, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After indicated treatment, cells were reacted with CCK-8 reagent, and the optical density (OD) was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader (TECAN, China).

Western Blot

Brain tissue and PC12 cells were processed by homogenization and centrifugation using RIPA buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma, USA). The resulting supernatants were collected for subsequent Western blot analysis. Protein concentrations were determined, and equal amounts of protein were loaded onto an SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane and blocked in skim milk for 2 h. The membrane was labeled with primary antibodies specific for FDX1, DLST, DLAT, lipid-DLAT, lipid-DLST, p65, p-p65, p-IκBα and β-actin overnight at 4°C. After that, the blots were washed and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (ab6721, Abcam). The detection of protein bands was achieved using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system. The signal strength of the bands was quantified using ImageJ software.

Detection of Cuprotosis

The levels of cuprotosis biomarker Cu, α-KG, and PA were measured using commercial kit. The concentrations of copper (Cu), pyruvic acid (PA), and α-ketoglutarate (α-KG) were determined using respective commercial assay kits. The copper levels were assessed with the Cu detection kit (Elabscience, China). The PA levels were measured using the CheKine PA detection kit (Abbkine, China). Meanwhile, the α-KG levels were analyzed with the Alpha Ketoglutarate (α-KG) Assay Kit (Abcam, USA). All assays were performed in accordance with the manufacturers’ recommended protocols.

Statistics

Data in present study were analyzed using the SPSS software (version 20.0) and GraphPad Prism 7.0 software. For comparison, two-sided Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

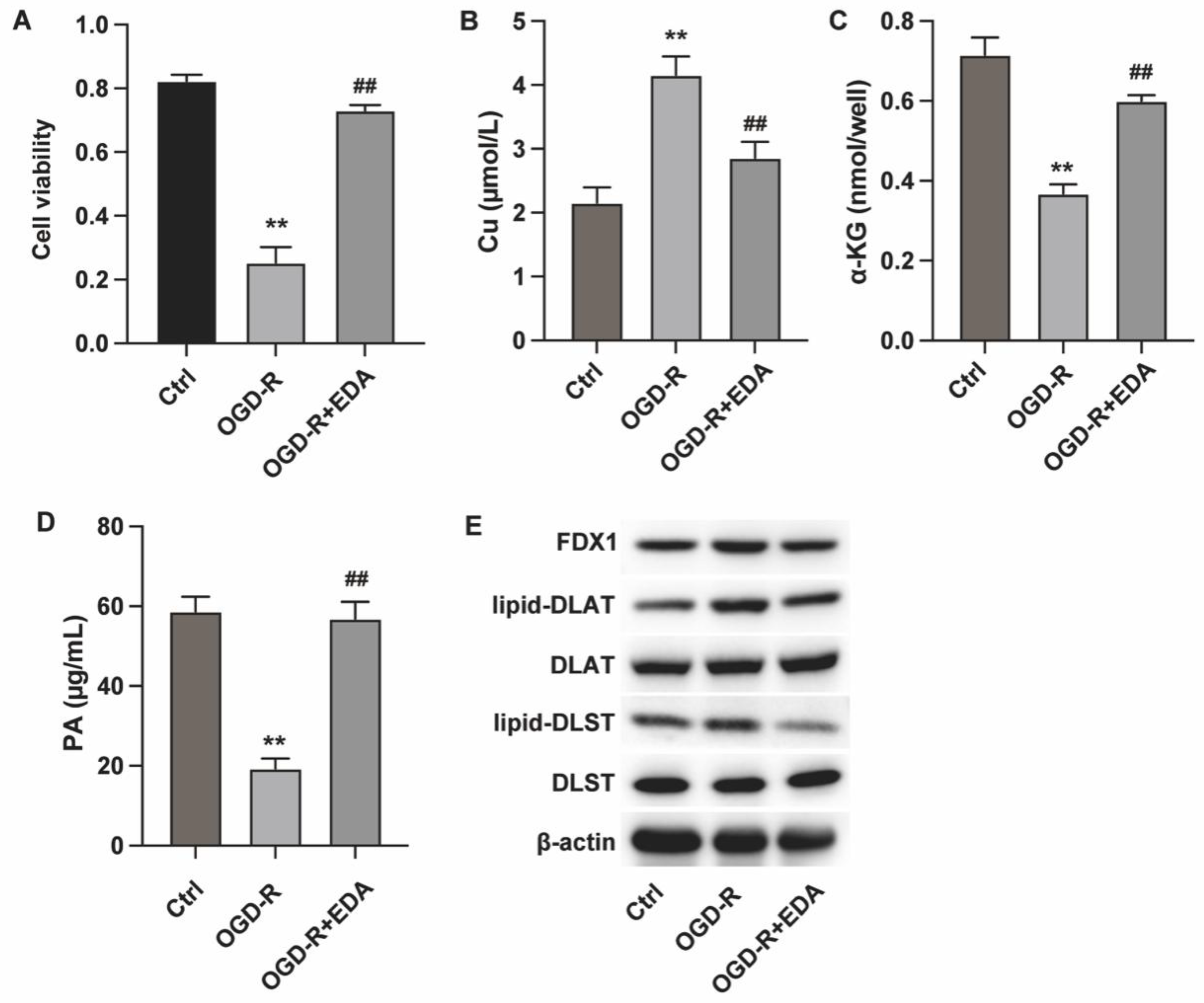

Edaravone Alleviates Cuprotosis of Ischemic Neurons

We first analyzed the in vitro effects of Edaravone (EDA) on neuron cuprotosis in an in vitro OGD-R model. The results from CCK-8 assay indicated that EDA treatment could recover neuron viability (

Figure 1A). Analysis on cuprotosis biomarkers showed that OGD-R induced Cu (II) accumulation (

Figure 1B) and reduced α-KG and PA levels (

Figure 1C and D), which were reversed by EDA treatment. Moreover, EDA treatment downregulated the expression of FDX1 and the lipoylation of DLST and DLAT (

Figure 1D), confirming the alleviated cuprotosis by EDA.

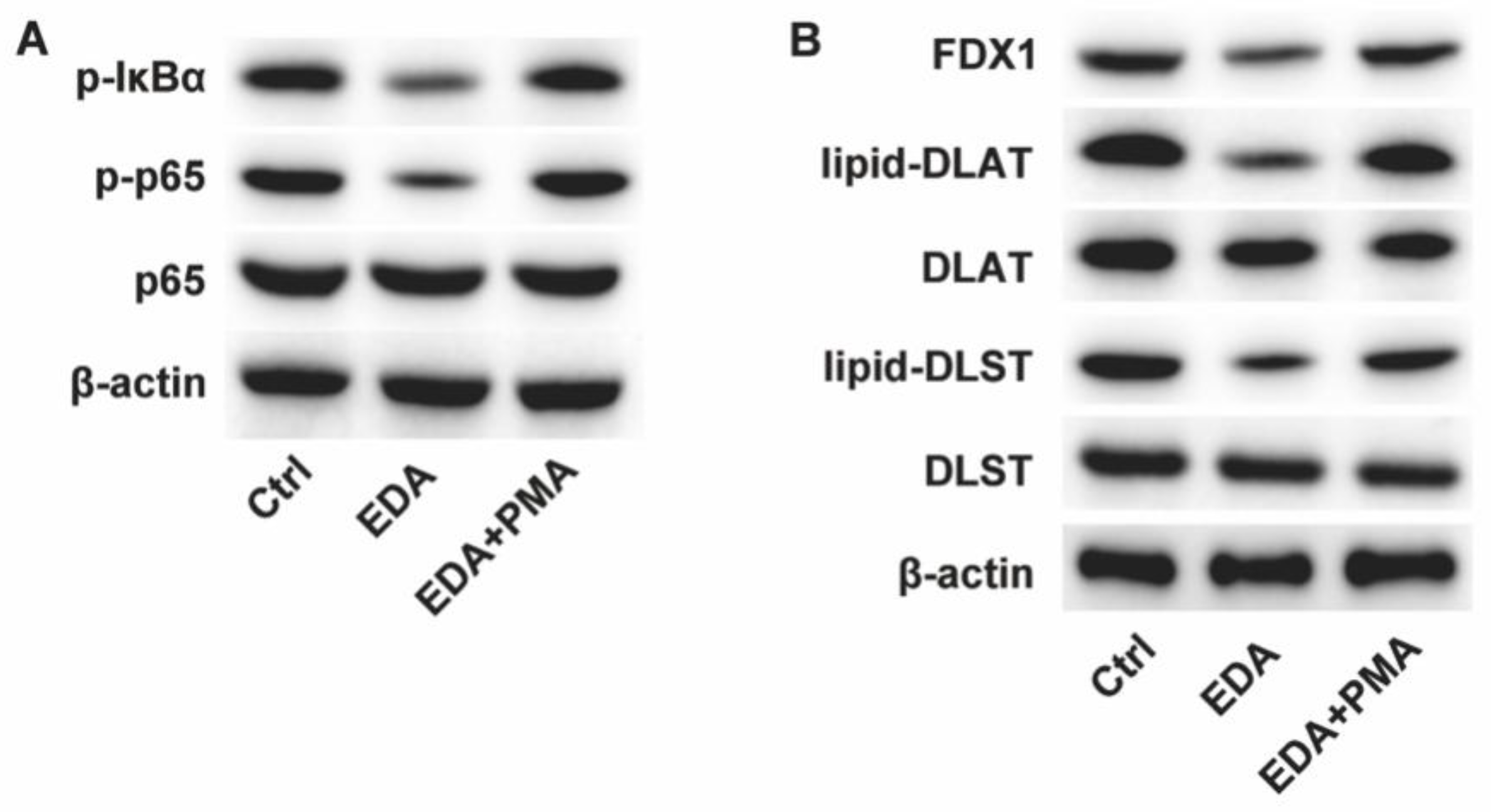

Edaravone Regulates the NF-κB Signaling in Neurons

Next, we found that EDA treatment suppressed the phosphorylation of IκBα and p65, whereas the administration with NF-κB activator PMA could abolish this effect (

Figure 2A). Besides, PMA also reversed the expression of FDX1 and lipoylation of DLST and DLAT that suppressed by EDA (

Figure 2B).

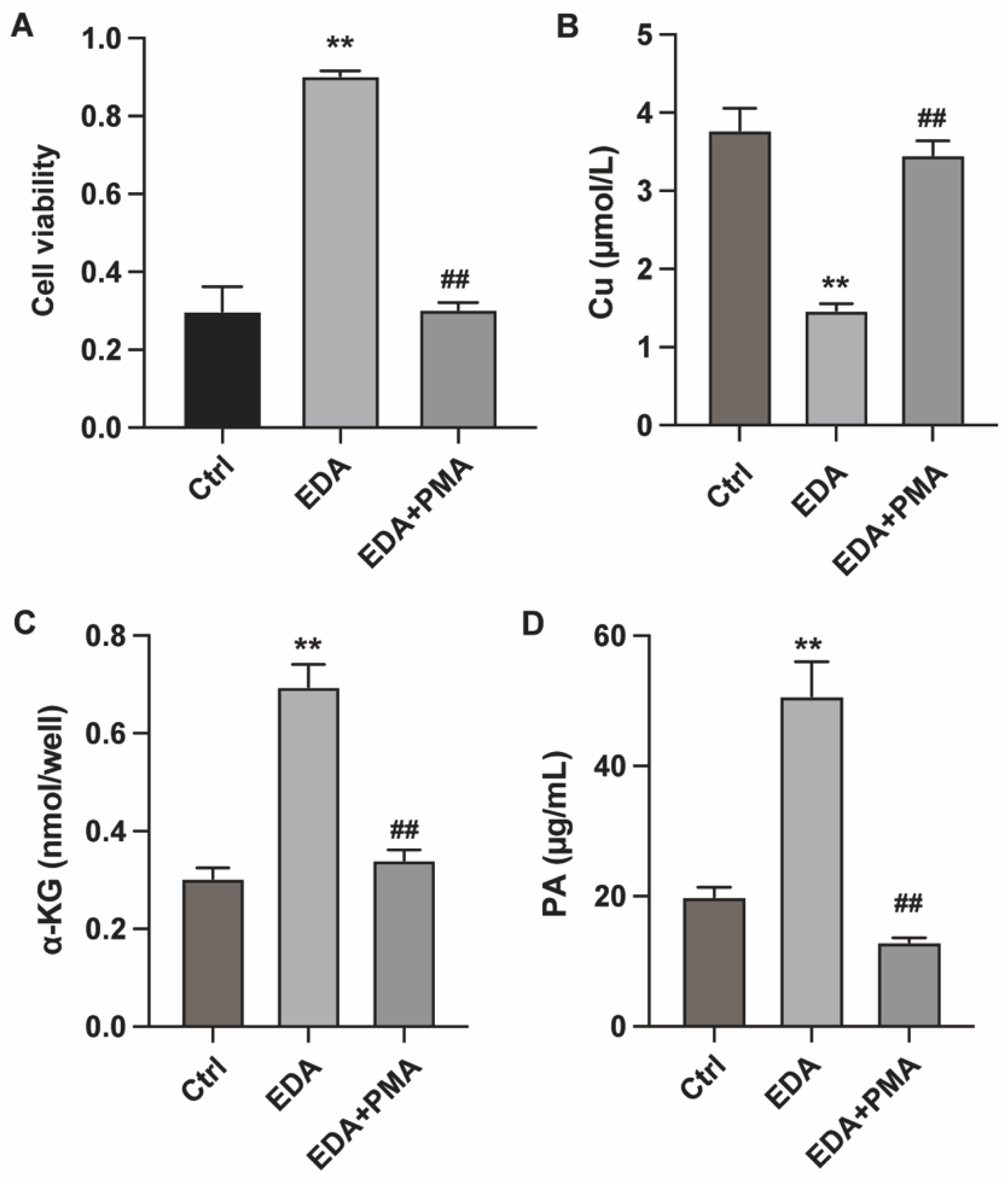

Edaravone Modulates Neuron Cuprotosis via Targeting NF-κB

Activation of NF-κB abolished the pro-survival effect of EDA in the OGD-R model (

Figure 3A). Moreover, PMA treatment elevated the Cu (II) accumulation and reduced α-KG and PA levels, indicating that NF-κB activation abolished the anti-cuprotosis effect of EDA (

Figure 3B-D).

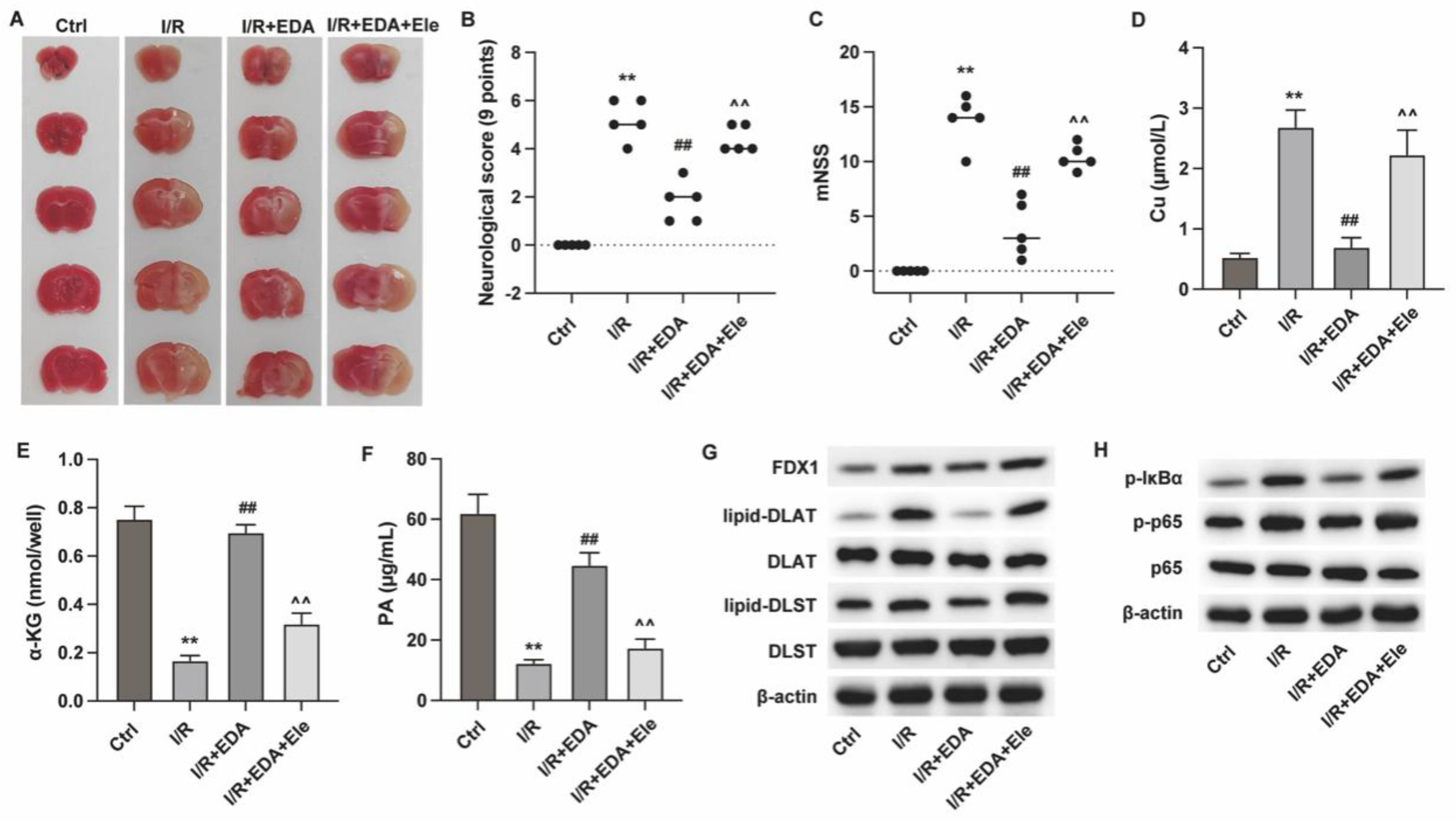

Edaravone Improves Ischemic Stroke via Alleviating Cuprotosis

Subsequently, we investigated the in vivo effects of EDA using mouse I/R model. As shown in

Figure 4A, the results from TTC staining demonstrated that EDA reduced the infarct size of I/R mouse hearts (

Figure 4A), suppressed the neurological score (

Figure 4B) and mNSS score (

Figure 4C), whereas treatment with the cuprotosis inducer elesclomol (Ele) suppressed these effects. The detection of cuprotosis biomarkers showed that EDA treatment suppressed cuprotosis in brain tissues of I/R mouse (

Figure 4D-F) and downregulated the FDX1, lipid-DLST and lipid-DLAT (

Figure 4G), whereas Ele treatment reversed the effects. Similar with the in vitro effects, EDA suppressed the activation of NF-κB, which was reversed by Ele treatment (

Figure 4H).

Discussion

Cerebral ischemia can lead to the death of brain cells and can result from various conditions such as stroke, particularly ischemic stroke, which accounts for about 80% of all strokes [

17]. The affected brain region and the severity of the ischemia determine the clinical manifestations, which may include sudden weakness, confusion, difficulty speaking, and loss of vision or sensation, severely impair the life quality and health of patients[

18,

19]. Treatment strategies include thrombolysis, antiplatelet therapy, and supportive care to manage the underlying cause and prevent further injury [

20,

21]. However, further mechanistic studies are needed to investigate the detailed regulatory mechanisms and are imperative for improving the clinical outcome of ischemic stroke.

EDA is a widely used cerebral protection reagent. Preclinical studies suggest that intravenous administration of EDA after ischemia-reperfusion in rats can prevent the progression of cerebral edema and cerebral infarction, relieve the accompanying neurological symptoms, and inhibit delayed neuronal death [

22]. However, the long-term effects of EDA on death or disability still require confirmation in larger-scale clinical trials. Consistent with the previous reports, our findings demonstrated that EDA treatment alleviated the brain damage and neuron death both in vitro and in vivo. Besides, we confirmed that EDA treatment relieved the accumulation of Cu in brain tissues and suppressed cuproptosis, as manifested by the altered expression of FDX1 and lipoylation of DLST and DLAT.

The EDA’s mechanism of action involves its potent free radical scavenging activity, which can penetrate the blood-brain barrier and protect neurons, glia, and vascular cells against oxidative stress [

23]. EDA has also been shown to modulate the expression of Nrf2 and its downstream antioxidant enzymes, suggesting its role in the antioxidant defense system against oxidative stress-induced neuronal damage [

14]. Our study revealed that EDA repressed the cuprotosis of injured neurons via regulating the NF-κB signaling pathway. NF-κB is the critical factor regulating the inflammatory response and participates in the development of ischemic stroke via induing neuroinflammation [

24]. And targeting NF-κB is a promising strategy for ischemic stroke treatment [

25,

26]. Previous studies have reported that EDA could target the NF-κB signaling to ameliorate cognitive impairment in bilateral carotid artery stenosis model [

27] and alleviated cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury [

28]. However, further study is necessary to identify the specific molecular mechanisms and critical factor that participate in the connection between NF-κB and cuprotosis in ischemic stroke.

Conclusion

EDA treatment alleviated the ischemia-induced cuproptosis of neurons and cerebral damage via targeting the NF-κB signaling pathway. Our findings explored a novel molecular mechanism correlated with ischemic stroke and presented a promising target and therapeutic strategy for stroke.

Funding

This study was supported by Xuzhou Science and Technology Bureau Key R&D Program (KC21234) and Xuzhou Municipal Health Commission (XWRCSL20220149).

References

- Huang, X. A Concise Review on Oxidative Stress-Mediated Ferroptosis and Cuproptosis in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Copper Induces Cognitive Impairment in Mice via Modulation of Cuproptosis and CREB Signaling. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Copper homeostasis and cuproptosis in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, J.; et al. Cuproptosis: mechanisms and links with cancers. Mol Cancer 2023, 22, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; et al. Copper homeostasis and copper-induced cell death in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and therapeutic strategies. Cell Death Dis 2023, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, X.X.; et al. Copper Metabolism and Cuproptosis: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Perspectives in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr Med Sci 2024, 44, 28–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of cuproptosis-related genes in immune infiltration in ischemic stroke. Front Neurol 2022, 13, 1077178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinshi, L.; et al. Cuproptosis-related genes are involved in immunodeficiency following ischemic stroke. Arch Med Sci 2024, 20, 321–325. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, L.; et al. Cuproptosis in stroke: focusing on pathogenesis and treatment. Front Mol Neurosci 2024, 17, 1349123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spasić, S.; et al. Edaravone May Prevent Ferroptosis in ALS. Curr Drug Targets 2020, 21, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, R.; et al. Edaravone ameliorates depressive and anxiety-like behaviors via Sirt1/Nrf2/HO-1/Gpx4 pathway. J Neuroinflammation 2022, 19, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, M.K. Riluzole and edaravone: A tale of two amyotrophic lateral sclerosis drugs. Med Res Rev 2019, 39, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; et al. Edaravone Dexborneol Versus Edaravone Alone for the Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Phase III, Randomized, Double-Blind, Comparative Trial. Stroke 2021, 52, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; et al. Edaravone dexborneol protects cerebral ischemia reperfusion injury through activating Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway in mice. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2022, 36, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, S.S.; et al. Edaravone alleviates Alzheimer’s disease-type pathologies and cognitive deficits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 5225–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Y.F.; et al. Edaravone, a free radical scavenger, is effective on neuropathic pain in rats. Brain Res 2009, 1248, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feske, S.K. Ischemic Stroke. Am J Med 2021, 134, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, K. What Is Acute Ischemic Stroke? Jama 2022, 327, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Candelario-Jalil, E. Emerging neuroprotective strategies for the treatment of ischemic stroke: An overview of clinical and preclinical studies. Exp Neurol 2021, 335, 113518. [Google Scholar]

- Herpich, F.; Rincon, F. Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke. Crit Care Med 2020, 48, 1654–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marto, J.P.; et al. Drugs Associated With Ischemic Stroke: A Review for Clinicians. Stroke 2021, 52, e646–e659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; et al. Edaravone for Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clinical Therapeutics 2022, 44, e29–e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, S.J.; Kim, K. Effects of the Edaravone, a Drug Approved for the Treatment of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, on Mitochondrial Function and Neuroprotection. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; et al. Icariside II preconditioning evokes robust neuroprotection against ischaemic stroke, by targeting Nrf2 and the OXPHOS/NF-κB/ferroptosis pathway. Br J Pharmacol 2023, 180, 308–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; et al. mtDNA-STING Axis Mediates Microglial Polarization via IRF3/NF-κB Signaling After Ischemic Stroke. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 860977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xian, M.; et al. Aloe-emodin prevents nerve injury and neuroinflammation caused by ischemic stroke via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and NF-κB pathway. Food Funct 2021, 12, 8056–8067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; et al. Edaravone dexborneol ameliorates cognitive impairment by regulating the NF-κB pathway through AHR and promoting microglial polarization towards the M2 phenotype in mice with bilateral carotid artery stenosis (BCAS). Eur J Pharmacol 2023, 957, 176036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; et al. Edaravone dexborneol alleviates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury through NF-κB/NLRP3 signal pathway. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2024, 307, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).