Introduction

Definition of Traumatic Brain Injury

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke defines traumatic brain injury (TBI) as a brain injury that is caused by outside force, such as a bump, blow, or jolt to the head or body [

1]. Broadly, TBIs can be defined as penetrating, in which an object pierces the skull and enters the brain tissue, or non-penetrating, in which an external force is strong enough to move the brain within the skull. Further, TBI-related injury can be focal or diffuse, and can include anything from mild concussions to more severe hematomas, contusions, skull fractures, or diffuse axonal injury (DAI) [

1]. TBIs can additionally be classified as mild or moderate to severe, depending on a number of factors. Clinically, a mild TBI, or concussion, involves loss of consciousness lasting <30 minutes, any alteration of consciousness, or post-traumatic amnesia lasting <24 hours. A Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13 to 15 is also frequently used in a trauma setting, such as the ICU. In contrast, a moderate to severe TBI requires loss of consciousness lasting ≥ 30 minutes, post-traumatic amnesia lasting ≥24 hours, or GCS as low as 3 [

2]. Severity of TBI can also be assessed by the presence of focal neurological signs and neuroimaging with CT or MRI [

2].

Assessment of TBI

Glasgow Coma Scale

The GCS is widely used in acute care and intensive care settings to objectively assess the level of consciousness in trauma patients. It evaluates three domains: eye-opening (scores 1–4), verbal response (scores 1–5), and motor response (scores 1–6), resulting in a total score ranging from 3 to 15 [

3]. Since its introduction by Teasdale and Jennett in 1974, the GCS has become a standard measure of head injury severity. While its validity is generally supported by correlations with clinical and functional outcomes, reliability can vary based on assessor training and consistency. Among the components, motor response tends to have the highest interobserver reliability. Limitations include confounding factors such as pre-existing neurological deficits, speech or hearing impairments, sedation, and intubation, which can restrict accurate assessment, highlighting the importance of early GCS evaluation [

4].

Abbreviated Injury Scale and Injury Severity Score

The Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), developed in 1971 by the American Medical Association’s Committee on Medical Aspects of Automotive Injury, is an anatomical scoring system that rates injury severity in six body regions (head/neck, face, thorax, abdomen, extremities, external) on a scale from 1 (minor) to 6 (maximal/fatal) using clinical and imaging findings [

5]. Mild TBI corresponds to AIS scores of 1-2, moderate TBI to 3-5, and fatal injuries to 6. Savitsky et al. (2015) identified an AIS score of ≥5 as an optimal threshold for severe TBI [

6]. The Injury Severity Score (ISS), developed in 1974, is a widely used composite score derived from AIS ratings by summing the squares of the three highest AIS scores from different body regions [

7,

8]. An ISS >15 is commonly used to define major trauma, though cutoffs may vary slightly depending on AIS versions [

8].

Impact of TBI

Demographics

Falls are the leading cause of TBI, especially among adults aged 65 and older, who are at the highest risk for hospitalization and death due to TBI. Other common causes include blunt trauma, vehicle accidents, assaults, and explosions. Males are more frequently hospitalized and have a threefold higher mortality risk compared to females [

1]. A 2019 global study reported an 8.4% increase in age-standardized TBI prevalence and a 3.6% increase in incidence between 1990 and 2016, trends attributed to population growth, aging, and increased motor vehicle use [

9]. Emergency departments in the U.S. handle over 25 million injury-related visits annually, including suspected TBIs [

10]. In 2019, approximately 223,135 TBI-related hospitalizations and 64,362 TBI-related deaths were reported, with adults aged 75+ accounting for nearly one-third of both hospitalizations and deaths [

10].

Cost of TBI in the United States

Miller et al. (2021) estimated the annual incremental healthcare costs of nonfatal TBI in the U.S. at

$40.6 billion in 2016, based on insurance claims data [

11]. Although moderate to severe TBIs are more costly per individual, low-severity TBIs contribute to a higher total economic burden due to their greater frequency. The CDC estimates the lifetime economic cost of TBI in 2010 at

$76.5 billion. These costs extend beyond acute care, as many patients experience chronic symptoms necessitating ongoing treatment [

10].

Factors Affecting Outcomes Following TBI

Moderate to severe TBI often results in lasting impairments affecting cognition, sensory processing, motor skills, mood, and behavior [

12]. Five years post-injury, 57% of survivors remain moderately to severely disabled; 50% have at least one hospital readmission; 33% require assistance with daily activities; and 12% reside in nursing homes or institutions [

12]. Longitudinal studies show variable recovery trajectories. Corrigan and Hammond (2013) found an increasingline in global outcome categories over 15 years post-injury [

13]. Forslund et al. (2019) observed that younger age, male sex, white-collar employment, and lower injury severity were associated with better global functioning over 10 years [

14]. While gender effects on long-term outcomes are heterogeneous, recent analyses suggest females with moderate to severe TBI have higher in-hospital mortality, though no consistent sex differences are seen in long-term functional outcomes

[16,17]. Disability, mental health, and quality of life outcomes are variably influenced by sex, age, and injury severity, complicating assessment of gender effects [

16]. Domensino et al. (2024) reported that 3.2 years post-TBI, cognitive impairment, fatigue, and functional restrictions affect the majority of patients admitted to the ICU [

15]. Humphries et al. (2022) identified low GCS, comorbidities, depression, and male sex as risk factors for poor outcome one year after mild TBI [

18].

Mechanism and Type of Injury

Mechanism of injury also impacts outcomes. In pediatric patients, abusive head trauma is linked to more severe injury and poorer prognosis than accidental injury [

19]. In adults, age, GCS, and injury severity are stronger predictors of outcome than injury type [

20,

21]. Polytrauma further predicts worse discharge outcomes [

21]. Overall, GCS, AIS, and ISS remain key prognostic indicators across populations [

14,

19].

Alcohol Use and TBI

Chronic alcohol use before TBI is associated with poorer cognitive and neuropsychological recovery [

22,

23]. Roy et al. (2022) found that patients with alcohol use disorder had lower performance in language, memory, and executive functions following mild to moderate TBI [

22]. Unsworth and Mathias (2016) meta-analysis reported poorer neuroimaging outcomes in TBI patients with a history of substance abuse but only moderate deficits in cognition [

23]. In contrast, the impact of acute alcohol intoxication at injury time on outcomes is less clear. Mathias and Osborn (2016) found no consistent differences in long-term outcomes related to blood alcohol levels on admission [

24]. Roy et al. (2022) similarly reported no acute cognitive recovery difference by blood alcohol level [

22]. More recently,g et al. (2023) observed that pre-injury alcohol intake was associated with lower in-hospital mortality and better functional recovery in TBI patients, with higher alcohol concentrations correlating with lower mortality [

25].

Disposition Following TBI

Disposition after severe TBI strongly correlates with clinical outcomes. Discharge home is generally linked to better functional recovery and lower mortality, while discharge to long-term care is associated with older age, greater injury severity, and comorbidity burden [

26,

27,

28]. Social determinants also influence disposition: white, non-Hispanic patients and those with insurance are more likely to be discharged to rehabilitation facilities [

27,

28,

29]. Stanley et al. (2022) reported that hospital characteristics and regional practices affect disposition patterns, with larger hospitals and groups of neurosurgeons favoring skilled nursing discharges, and geographic variation influencing rates of home versus rehabilitation discharge [

30]. This study aims to further correlate clinical outcomes with discharge dispositions in patients with severe TBI.

Methods

We performed a single-center, retrospective review at Elmhurst Hospital, a Level 1 trauma center in Queens, New York City. The study included all patients who presented with severe TBI, defined as an AIS score of 3 or greater, betweenuary 1, 2020, andember 31, 2023. Patients were excluded if they had non-severe or minor injuries, an AIS score less than 3, or died or were discharged within 24 hours of admission.

Patient data were obtained from the National Trauma Registry of the American College of Surgeons (NTRACS) database at our institution. Patients were identified based on injury type (blunt vs. penetrating) and AIS score. After data review, a final cohort of 824 patients was included. Data extracted and organized in Excel encompassed demographics (gender, ethnicity, race), injury severity (GCS, AIS, ISS), injury type, mortality, disposition (e.g., home, rehabilitation, skilled nursing facility), length of stay (ED, hospital, ICU), ventilator days, and blood alcohol levels on admission.

We conducted two levels of analysis:

Analysis 1: Associations between categorical variables (e.g., ethnicity, gender, injury type) and patient disposition were assessed using contingency tables and statistical tests, including Chi-Square, Fisher’s Exact, and Monte Carlo simulations. Monte Carlo simulations, with 10,000 iterations per test, provided robust p-value estimates, especially for categories with small sample sizes or missing data.

Analysis 2: Relationships between patient disposition and continuous clinical variables were evaluated using parametric (ANOVA) and non-parametric tests (Kruskal-Wallis, Wilcoxon, Van der Waerden, Savage, Kolmogorov-Smirnov, and Cramer-von Mises) to ensure validity across different data distributions.

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the 824 patients included in the analysis. The cohort was predominantly male (n = 617), non-Hispanic (n = 408), identified as “Other” race (n = 468), and sustained blunt injuries (n = 806). Abbreviations: AMA = Discharged Against Medical Advice; SAR = Subacute Rehabilitation; SNF = Skilled Nursing Facility.

Results

The study cohort included 824 patients, of whom 617 (74.9%) were male. Missing data ranged from approximately 24% to 27%, varying by variable. The majority of patients were discharged home (52.8%), followed by death (12.4%), discharge to home with services or subacute rehabilitation (SAR) (5.6%), and TBI rehabilitation (5.2%) (

Table 1).

Analysis 1 revealed statistically significant associations between patient disposition and gender (

Table 2; Chi-Square = 24.50, p = 0.0174, Monte Carlo Estimate for Exact Test, p = 0.0235) as well as disposition and injury type (

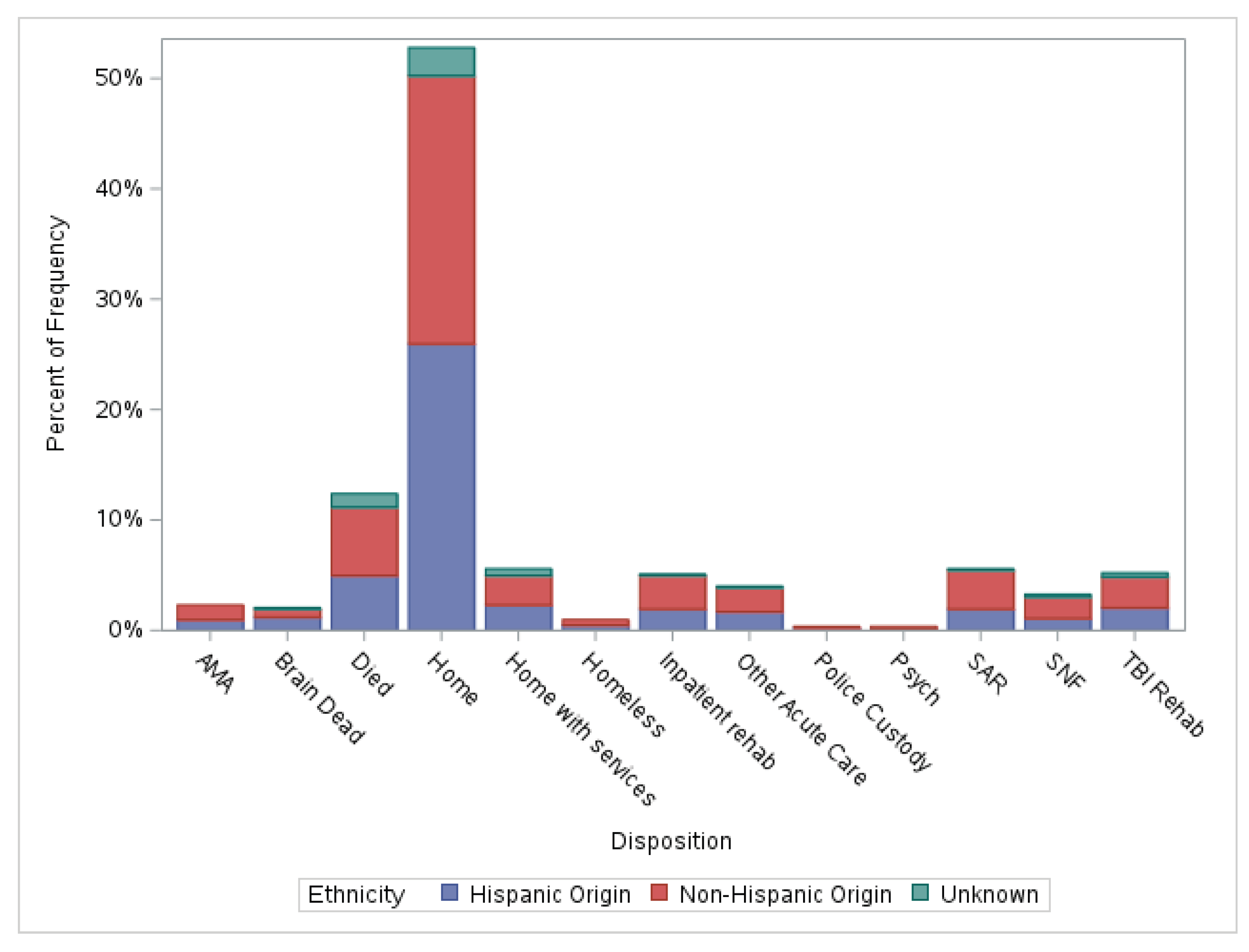

Table 3; Chi-Square = 24.29, p = 0.0186, Monte Carlo Estimate for Exact Test, p = 0.0304). However, no significant association was observed between disposition and ethnicity (

Figure 1).

Table 2: This table presents the number and percentage of patients by disposition, stratified by gender (male vs. female). The majority of the cohort were male (74.9%). In both genders, the most common disposition was discharge home (52.8%). Abbreviations: AMA = Discharged Against Medical Advice; SAR = Subacute Rehabilitation; SNF = Skilled Nursing Facility.

Table 3: This table presents the number and percentage of patients by disposition, stratified by injury type (blunt vs. penetrating). The majority of patients (97.8%) sustained blunt trauma. Overall, most patients were discharged home (52.8%), followed by death (12.4%). Among patients with blunt injuries, 52.1% were discharged home. For the smaller cohort with penetrating injuries (0.73%), an equal proportion were either discharged home or died. Abbreviations: AMA = Discharged Against Medical Advice; SAR = Subacute Rehabilitation; SNF = Skilled Nursing Facility.

Figure 1: Stacked bar graph illustrating the distribution of patient dispositions across ethnic groups in the sample. Ethnicity categories are represented by color: blue for Hispanic origin, red for non-Hispanic origin, and green for unknown. In all ethnic groups, the majority of patients were discharged home, followed by death. Abbreviations: AMA = Discharged Against Medical Advice; SAR = Subacute Rehabilitation; SNF = Skilled Nursing Facility.

In analysis 2, disposition was significantly associated with all clinical variables (

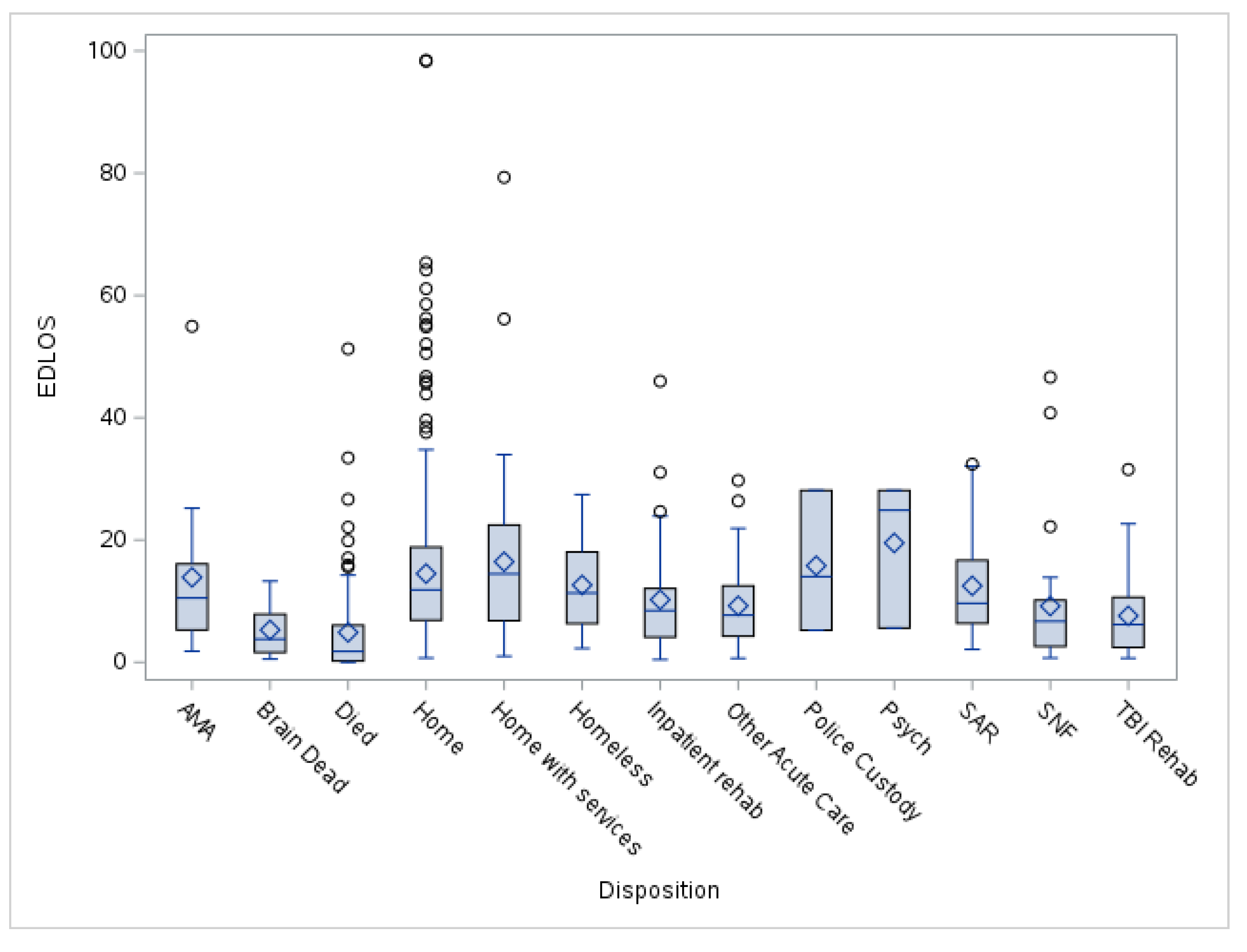

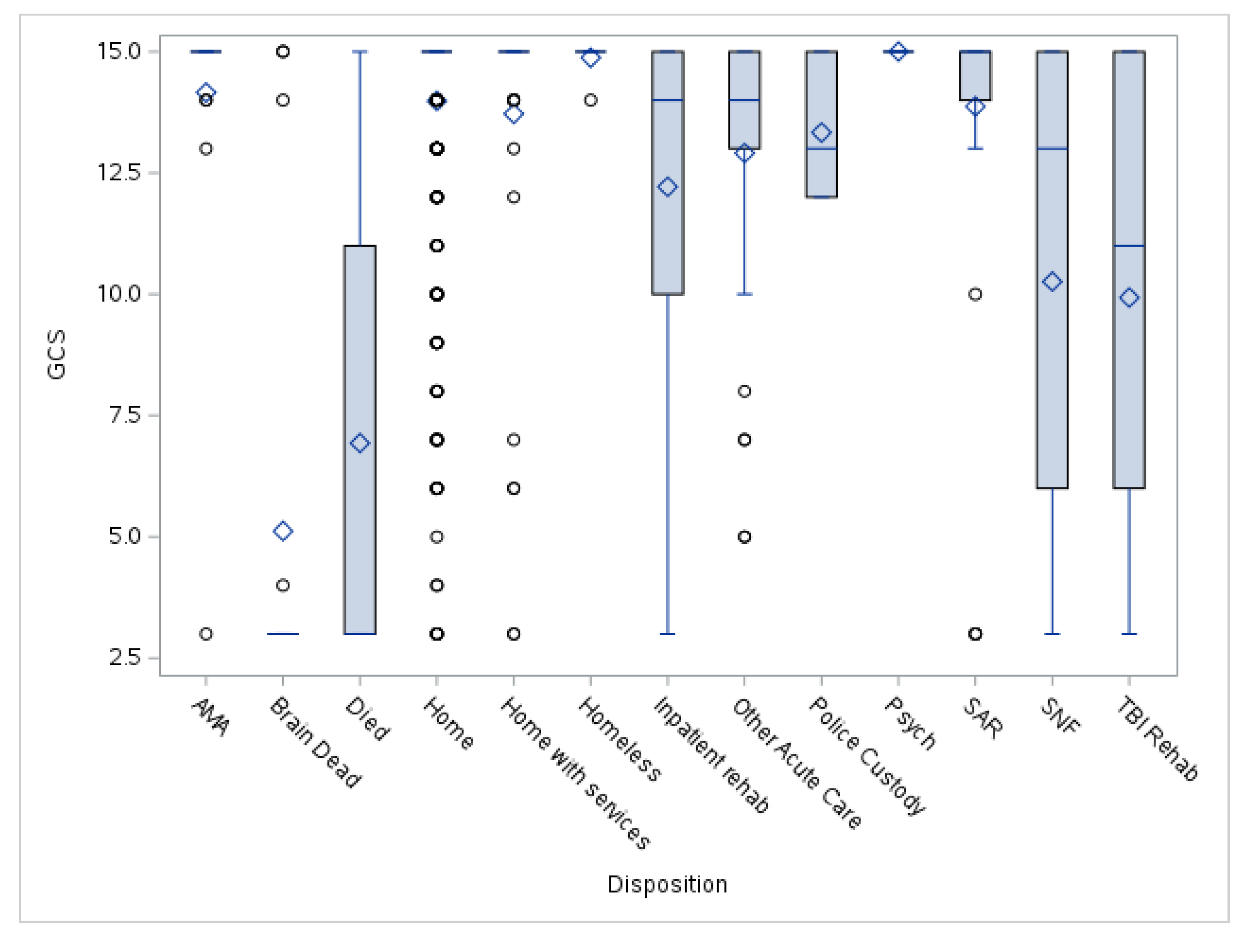

Table 4). However, mean values of key clinical variables varied widely by disposition group. For example, patients discharged to SNF or TBI Rehab had much longer hospital and ICU stays than those discharged home, while patients who died or were brain dead had higher ISS and AIS scores and lower GCS scores.

Table 5 illustrates the significant parametric (ANOVA) and non-parametric (Kruskal-Wallis) results for disposition compared to length of stay data, with p-values <0.0001 for each.

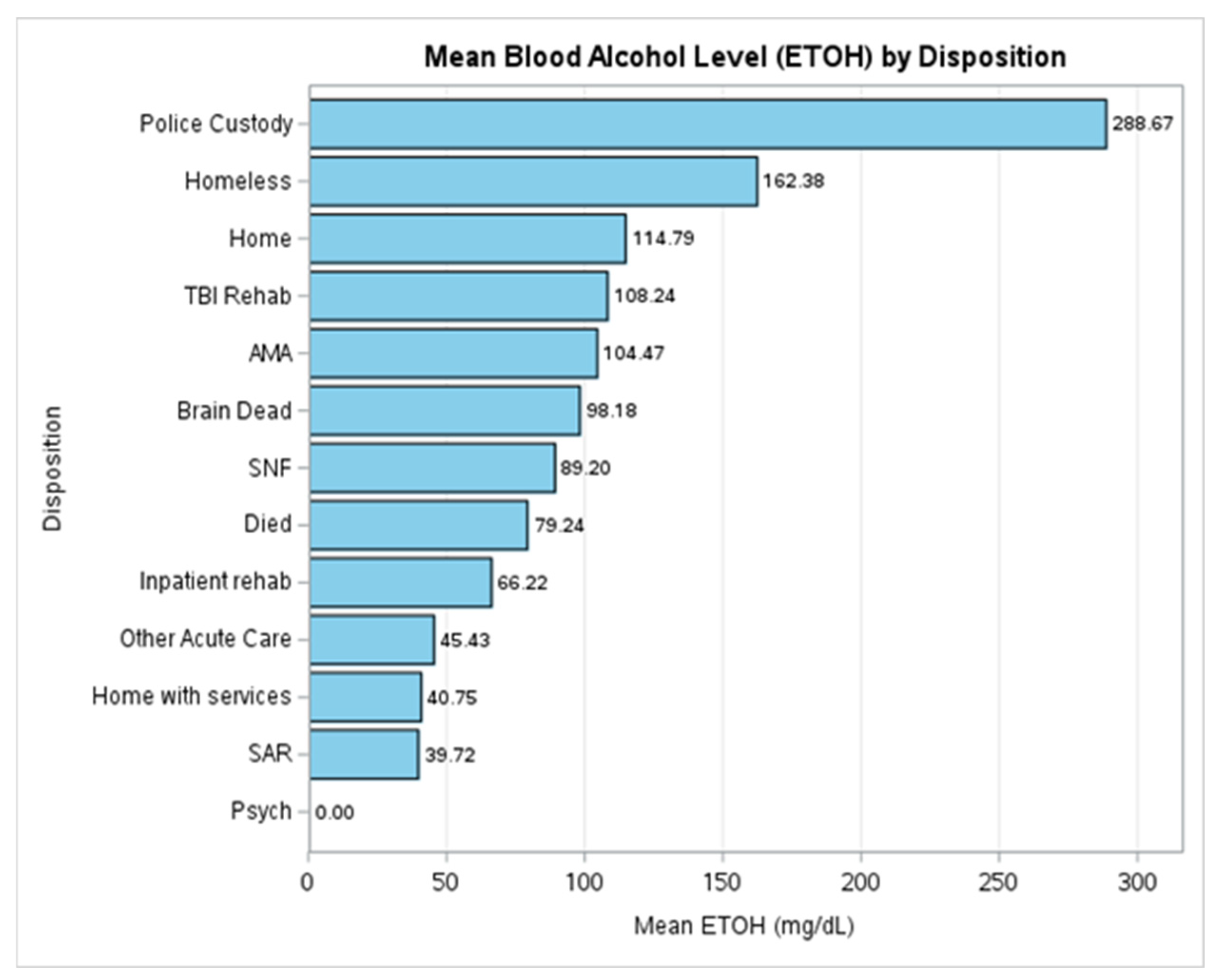

Table 4: This table presents the total number of patients within each disposition category, alongside mean values for key clinical variables stratified by disposition. Longer hospital length of stay (HLOS) and intensive care unit length of stay (ICULOS) were associated with discharge to skilled nursing facilities (SNF), followed by traumatic brain injury (TBI) rehabilitation. The extended duration of mechanical ventilation correlated most strongly with discharge to SNF and brain death. Lower Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores and higher Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) and Injury Severity Score (ISS) values were linked to death or brain death. Elevated mean blood alcohol levels were associated with disposition to police custody, followed by homelessness. Prolonged emergency department length of stay (EDLOS) was predominantly associated with psychiatric admissions and police custody. Abbreviations: EDLOS = Emergency Department Length of Stay; HLOS = Hospital Length of Stay; ICULOS = Intensive Care Unit Length of Stay; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale; ISS = Injury Severity Score; AIS = Abbreviated Injury Scale; ETOH = Blood ethanol level on admission; AMA = Discharged Against Medical Advice; SAR = Subacute Rehabilitation; SNF = Skilled Nursing Facility. All lengths of stay and ventilation duration are reported in days; ETOH is reported in mg/dL.

Figure 2: This boxplot depicts the distribution of average Emergency Department Length of Stay (EDLOS) in days across different disposition categories. Longer EDLOS was notably associated with admission to psychiatric facilities or police custody. Abbreviations: EDLOS = Emergency Department Length of Stay; AMA = Discharged Against Medical Advice; SAR = Subacute Rehabilitation; SNF = Skilled Nursing Facility.

Table 5: This table presents the results of parametric (ANOVA) and non-parametric (F test/Chi-Square) analyses comparing key clinical variables across disposition groups. All variables demonstrated statistically significant differences with p-values < 0.001. Abbreviations: EDLOS = Emergency Department Length of Stay; HLOS = Hospital Length of Stay; ICULOS = Intensive Care Unit Length of Stay; GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale; ISS = Injury Severity Score; AIS = Abbreviated Injury Scale; ETOH = Blood ethanol level on admission; DF = Degrees of Freedom.

Alcohol levels (EtOH) also showed a significant association with disposition (ANOVA F = 3.08, p = 0.0003). Mean Alcohol level in mg/dL by disposition can be seen in

Figure 4.

Figure 4: This bar graph depicts the mean blood alcohol levels (ETOH), measured in mg/dL, stratified by patient disposition categories.

Discussion

Disposition has been extensively studied regarding TBI outcomes, with factors such as injury severity, mechanism of injury, age, and alcohol use playing critical roles in determining clinical outcomes [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. In our cohort, the most common disposition was discharge home, consistent with existing literature [

28,

29,

30]. We also observed a significant association between gender and disposition. Excluding patients who died, most female patients were discharged home, followed by discharge to subacute rehabilitation (SAR), and then home with services. In contrast, most male patients were discharged home, followed by TBI rehabilitation, and then inpatient rehabilitation or home with services in equal proportion. The relationship between gender and disposition post-TBI is complex and appears to interact with factors such as age, injury type and severity, alcohol use, and hospital characteristics.

Ingram et al. (2022) examined sex differences in trauma care efficiency and their association with discharge disposition using data from the 2013–2016 American College of Surgeons Trauma Quality Improvement Project (TQIP) database [

31]. They reported that female patients experienced significantly longer emergency department (ED) length of stay (LOS), delays in femur or pelvic fracture repairs, and were more likely to be discharged to long-term care facilities than home after adjusting for age, injury severity score (ISS), injury type, and mechanism [

31]. Similarly, in our analysis, although both males and females were most frequently discharged home, a significantly higher proportion of males (41%) were discharged home compared to females (12%), suggesting that female patients may be more likely to be discharged to long-term care facilities.

Teterina et al. (2023) investigated the impact of gender and sex on outcomes following severe TBI in a large cohort of Ontario residents [

32]. They found that sex significantly influenced early mortality, while gender had a stronger effect on discharge disposition, with individuals expressing more “woman-like” characteristics having lower odds of discharge to rehabilitation versus home [

32]. The observed differences in disposition may reflect social factors, including women’s traditional caregiving roles, reduced in-home support, or family preferences favoring institutional care for female patients [

16,

31,

32]. Additionally, female injury severity may be underestimated, leading to under-triage and less aggressive acute care, which could influence disposition away from home [

31]. Such sex-based differences have been reported across a range of acute and chronic conditions, including general trauma and hypoxic-ischemic brain injury [

31,

33].

Length of stay in the hospital, ED, and intensive care unit (ICU) were all significantly associated with disposition in our study. Consistent with prior research, longer hospital LOS is strongly linked to discharge to skilled nursing facilities, long-term care, or inpatient rehabilitation, whereas shorter LOS correlates with discharge home; these relationships persist after controlling for age, injury severity, comorbidities, injury mechanism, and hospital factors [

27,

28]. Taylor et al. (2025) defined prolonged LOS as greater than two standard deviations above the mean (24 days) following TBI and found that such patients were more likely to be discharged to inpatient facilities or to die, and less likely to be discharged home. These patients also presented with lower Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores on arrival, longer ICU stays, higher ISS, and increased ventilator days [

34]. Our findings align with these observations: longer hospital and ICU LOS were associated with discharge to inpatient facilities such as SNF or TBI rehabilitation, while extended ED LOS correlated with discharge to psychiatric care, home with services, or police custody.

Yue et al. (2024) identified Medicaid insurance as an independent predictor of prolonged hospital LOS (>47 days) across TBI severity strata [

35]. The effect size of Medicaid on prolonged LOS increased with injury severity, and paradoxically, patients with more severe injuries who would benefit from post-acute care faced greater risks of delayed discharge [

35]. Although we did not analyze insurance status in our cohort, its potential modifying effect on disposition warrants further investigation.

Consistent with existing literature, longer ICU LOS was associated with reduced likelihood of discharge home and increased likelihood of discharge to skilled nursing facilities, long-term care, or rehabilitation [

27,

28,

29,

36,

37]. Beijer et al. (2023) reported that female patients with severe TBI admitted to level 1 trauma centers in the Netherlands had lower ICU admission rates and shorter ICU LOS, with female sex associated with areased likelihood of ICU stays exceeding seven days [

38].

While increased ED LOS is generally associated withreased likelihood of discharge home and increased likelihood of discharge to long-term care [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], our study’s findings differed somewhat. The longest average ED LOSs were observed among patients discharged to psychiatric care or police custody, likely reflecting a high prevalence of undomiciled patients and elevated blood alcohol levels at admission. Elevated alcohol levels were most strongly associated with discharge to police custody, followed by homelessness, and then home. Prior studies similarly report that higher blood alcohol levels at presentation correlate withreased likelihood of discharge home. These patients tend to be younger, male, and present with lower GCS and higher ISS, increasing their likelihood of institutional care at discharge [

29,

39]. Blood alcohol level is generally aker for more severe injury and higher probability of discharge to long-term care, with these associations modulated by demographic and clinical factors [

25,

39,

40].

Patients who required prolonged mechanical ventilation and survived without brain death were more likely to be discharged to SNF, followed by TBI rehabilitation and inpatient rehabilitation. This aligns with existing data demonstrating that prolonged ventilation is aker of increased injury severity and clinical complexity, reducing the likelihood of functional independence at discharge. Prolonged mechanical ventilation is also associated with extended ICU and total hospital LOS in severe TBI patients [

41,

42], making it a robust indirect predictor of disposition.

Finally, the type of injury was significantly associated with disposition. Approximately 98% of patients sustained blunt injuries, with the majority discharged home, followed by death, SAR, and home with services equally. Among the 18 patients with penetrating injuries, nearly all were discharged home or died (six each), although the small sample limits definitive conclusions. While blunt trauma predominates as a cause of civilian TBI [

43], current evidence does not support injury type as an independent predictor of disposition or outcomes.

Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this study is the comprehensive analysis of a large, diverse patient cohort with severe TBI, allowing examination of multiple factors—including injury severity, gender, length of stay across different hospital settings, and blood alcohol levels—and their associations with discharge disposition. Additionally, the integration of detailed clinical variables alongside disposition outcomes provides valuable insights consistent with, and complementary to, existing literature. The use of robust statistical methods, including Monte Carlo simulations and multiple parametric and non-parametric tests, strengthened the validity of our findings, particularly in the context of categorical variables with low expected frequencies.

However, the study has several limitations. The retrospective design limits causal inference and is subject to potential biases inherent in registry and medical record data. Insurance status, an important factor influencing disposition, was not evaluated and may have confounded observed associations. The small sample size of penetrating injury cases restricts meaningful comparisons with blunt injury. Furthermore, social determinants such as caregiver availability, socioeconomic status, and pre-existing comorbidities—factors known to affect discharge disposition—were not fully captured in the dataset. Additionally, potential variability in hospital discharge practices and resource availability at a single center may limit the generalizability of our results to other settings.

Future prospective multicenter studies incorporating insurance data, detailed social factors, and broader clinical variables would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex interplay of factors influencing disposition outcomes following severe TBI. This would also help clarify the nuanced role of gender and other demographic factors observed in this study.

Conclusion

Our analysis corroborates existing literature demonstrating that discharge disposition following severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) is multifactorial, predominantly influenced by injury severity, patient age, demographic characteristics, injury mechanism, alcohol use, and hospital-related factors. Notably, we did not observe statistically significant differences in disposition based on ethnicity, though this may reflect limitations in sample size or demographic composition. Additionally, the role of insurance status was not assessed in this study, despite evidence from prior research suggesting that insured, white, and non-Hispanic patients are more frequently discharged to long-term rehabilitation facilities rather than home. Incorporating insurance and socioeconomic factors in future investigations could enhance understanding of disposition determinants.

While injury severity indices such as Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS), and Injury Severity Score (ISS), as well as hospital length of stay (LOS), remain robust independent predictors of post-TBI disposition, other factors—particularly sex—demonstrate more complex interactions. These variables are influenced by a combination of clinical and social factors, including age, pre-existing comorbidities, and support systems, which collectively affect outcomes and discharge planning. Our findings emphasize the importance of considering multiple patient and clinical characteristics when predicting discharge disposition.

Furthermore, this study highlights significant associations between disposition and length of stay in the emergency department (ED), hospital, and intensive care unit (ICU), duration of mechanical ventilation, and mean blood alcohol concentration at admission. These findings align with prior evidence linking prolonged hospitalization and higher injury acuity to increased likelihood of discharge to institutional care settings. Nonetheless, the intricate interplay between these factors and patient demographics such as age, insurance status, and comorbid conditions warrants further elucidation.

In conclusion, our results reinforce the complex, multifactorial nature of disposition outcomes after severe TBI. Future research should prioritize comprehensive, prospective studies that include socioeconomic and psychosocial determinants, enabling the development of predictive models with greater accuracy and clinical utility. Such efforts may ultimately inform individualized discharge planning and optimize resource allocation for this vulnerable population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization—B.S.; Resources- C.G., N.P., J.D., and G.A.; Methodology- B.S., Formal analysis- B.S. and T.P., Investigation- B.S., J.M., and N.D.B., writing—original draft preparation—B.S. and S.D.M.; writing—review and editing—B.S., J.W., K.T., S.B., S.P., M.H., and Z.S., supervision—B.S.; project administration—B.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There is no grant support or financial relationship for this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective study was approved by the IRB at Elmhurst Facility on 5 July 2024, with IRB number 24-12-092-05G.

Informed Consent Statement

Retrospective analysis was performed on anonymized data, and informed consent was not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data was requested from the Elmhurst Trauma registry and extracted using electronic medical records after receiving approval from the Institutional Review Board at our facility (Elmhurst Hospital Center).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no competing interests tolare.

References

-

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) (2024). National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

- Carlson, K.; Kehle, S.; Meis, L.; et al. The Assessment and Treatment of Individuals with a History of Traumatic Brain Injury and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Evidence [Internet]. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2009. [Table], Comparison of Mild TBI with Moderate and Severe TBI* Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK49142/table/introduction.

- Jain, S.; Iverson, L.M. Glasgow Coma Scale. [Updated 2023 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. 5132. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, G.; Maas, A.; Lecky, F.; Manley, G.; Stocchetti, N.; Murray, G. The Glasgow Coma Scale at 40 years: standing the test of time. Lancet Neurol. 2014, 13, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civil, I.D.; Schwab, C.W. The Abbreviated Injury Scale, 1985 revision: a condensed chart for clinical use. J Trauma. 1988, 28, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savitsky, B.; Givon, A.; Rozenfeld, M.; Radomislensky, I.; Peleg, K. Traumatic brain injury: It is all about definition. Brain Inj. 2016, 30, 1194–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.P.; O’Neill, B.; Haddon WJr Long, W.B. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974, 14, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, C.S.; Gabbe, B.J.; Cameron, P.A. Defining major trauma using the 2008 Abbreviated Injury Scale. Injury. 2016, 47, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2016 Traumatic Brain Injury and Spinal Cord Injury Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, e7. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Subcommittee (Writing Committee) on Mild Traumatic Brain, I. n.j.u.r.y.; Valente JH, Anderson JD, Paolo WF, Sarmiento K, Tomaszewski CA, Haukoos JS, Diercks, D.B.; Members of the American College of Emergency Physicians Clinical Policies Committee (Oversight, C.o.m.m.i.t.t.e.e.).; Diercks DB, Anderson JD, Byyny R, Carpenter CR, Friedman B, Gemme SR, Gerardo CJ, Godwin SA, Hahn SA, Hatten BW, Haukoos JS, Kaji A, Kwok H, Lo BM, Mace SE, Moran M, Promes SB, Shah KH, Shih RD, Silvers SM, Slivinski A, Smith MD, Thiessen MEW, Tomaszewski CA, Trent S, Valente JH, Wall SP, Westafer LM, Yu Y, Cantrill SV, Finnell JT, Schulz T, Vandertulip, K. Clinical Policy: Critical Issues in the Management of Adult Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department With Mild Traumatic Brain Injury: Approved by ACEP Board of Directors,ruary 1, 2023 Clinical Policy Endorsed by the Emergency Nurses Association (April 5, 2023). Ann Emerg Med. 2023, 81, e63–e105. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Miller, G.F.; DePadilla, L.; Xu, L. Costs of Nonfatal Traumatic Brain Injury in the United States, 2016. Med Care. 2021 ;59, 451-455. 1 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Traumatic Brain Injury and Concussion | About Potential Effects of a Moderate or Severe TBI (2024). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Corrigan, J.D.; Hammond, F.M. Traumatic brain injury is a chronic health condition. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013, 94, 1199–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forslund, M.V.; Perrin, P.B.; Røe, C.; Sigurdardottir, S.; Hellstrøm, T.; Berntsen, S.A.; Lu, J.; Arango-Lasprilla, J.C.; Andelic, N. Global Outcome Trajectories up to 10 Years After Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Neurol. 2019 14;10:219. [PubMed]

- Domensino, A.F.; Tas, J.; Donners, B.; Kooyman, J.; van der Horst, I.C.C.; Haeren, R.; Ariës, M.J.H.; van Heugten, C. Long-Term Follow-Up of Critically Ill Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury: From Intensive Care Parameters to Patient and Caregiver-Reported Outcome. J Neurotrauma. 2024, 41, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollayeva, T.; Mollayeva, S.; Pacheco, N.; Colantonio, A. Systematic Review of Sex and Gender Effects in Traumatic Brain Injury: Equity in Clinical and Functional Outcomes. Front Neurol. 2021 10;12:678971. [PubMed]

- Breeding, T.; tinez, B.; Katz, J.; Nasef, H.; Santos, R.G.; Zito, T.; Elkbuli, A. The Association Between Gender and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Surg Res. 2024, 295, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphries, T.J.; Sinha, S.; Dawson, J.; Lecky, F.; Singh, R. “Can differences in hospitalised mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) outcomes at 12 months be predicted? ”. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2022, 164, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, L.; Nuno, M.; Gurkoff, G.G.; Nosova, K.; Zwienenberg, M. Moderate and severe TBI in children and adolescents: The effects of age, sex, and injury severity on patient outcome 6 months after injury. Front Neurol. 2022, 13, 741717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Utsumi, S.; Ohki, S.; Shime, N. Epidemiology of moderate traumatic brain injury and factors associated with poor neurological outcome. J Neurosurg. 2024, 141, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanitanon, A.; Lyons, V.H.; Lele, A.V.; Krishnamoorthy, V.; Chaikittisilpa, N.; Chandee, T.; Vavilala, M.S. Clinical Epidemiology of Adults With Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury. Crit Care Med. 2018, 46, 781–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Roy, S.J.; Livernoche Leduc, C.; Paradis, V.; Cataford, G.; Potvin, M.J. The negative influence of chronic alcohol abuse on acute cognitive recovery after a traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2022, 36, 1340–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unsworth, D.J.; Mathias, J.L. Traumatic brain injury and alcohol/substance abuse: A Bayesian meta-analysis comparing the outcomes of people with and without a history of abuse. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2017, 39, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathias, J.L.; Osborn, A.J. Impact of day-of-injury alcohol consumption on outcomes after traumatic brain injury: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2018, 28, 997–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, E.; Ro, Y.S.; Jeong, J.; Ryu, H.H.; Shin, S.D. Alcohol intake before injury and functional and survival outcomes after traumatic brain injury: Pan-Asian trauma outcomes study (PATOS). Medicine (Baltimore). 2023 25;102, e34560. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, R.; Walder, B.; Delhumeau, C.; Müri, R.M. Predictors of inpatient (neuro)rehabilitation after acute care of severe traumatic brain injury: An epidemiological study. Brain Inj. 2016, 30, 1186–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuthbert, J.P.; Corrigan, J.D.; Harrison-Felix, C.; Coronado, V.; Dijkers, M.P.; Heinemann, A.W.; Whiteneck, G.G. Factors that predict acute hospitalization discharge disposition for adults with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011 May;92, 721-730.e3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarshenas, S.; Colantonio, A.; Alavinia, S.M.; Jaglal, S.; Tam, L.; Cullen, N. Predictors of Discharge Destination From Acute Care in Patients With Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2019/Feb;34, 52-64. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Gormley, M.; Donaldson, A.; Agyemang, A.; Karmarkar, A.; Seel, R.T. Identifying factors associated with acute hospital discharge dispositions in patients with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2022 23;36, 383-392. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, S.P.; Truong, E.I.; DeMario, B.S.; Ladhani, H.A.; Tseng, E.S.; Ho, V.P.; Kelly, M.L. Variations in Discharge Destination Following Severe Traumatic Brain Injury across the United States. J Surg Res. 2022, 271:98-105. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, M.E.; Nagalla, M.; Shan, Y.; et al. Sex-Based Disparities in Timeliness of Trauma Care and Discharge Disposition. JAMA Surg. 2022, 157, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teterina, A.; Zulbayar, S.; Mollayeva, T.; Chan, V.; Colantonio, A.; Escobar, M. Gender versus sex in predicting outcomes of traumatic brain injury: a cohort study utilizing large administrative databases. Sci Rep. 2023 27;13, 18453. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacob, B.; Chan, V.; Stock, D.; Colantonio, A.; Cullen, N. Determinants of Discharge Disposition From Acute Care for Survivors of Hypoxic-Ischemic Brain Injury: Results From a Large Population-Based Cohort Data Set. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021, 102, 1514–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.V.; Loo, G.T.; Richardson, L.D.; Legome, E. Patient Factors Associated With Prolonged Length of Stay After Traumatic Brain Injury. Cureus. 2024 ;16, e59989. 9 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.K.; Ramesh, R.; Krishnan, N.; Chyall, L.; Halabi, C.; Huang, M.C.; Manley, G.T.; Tarapore, P.E.; DiGiorgio, A.M. Medicaid Insurance is a Predictor of Prolonged Hospital Length of Stay After Traumatic Brain Injury: A Stratified National Trauma Data Bank Cohort Analysis of 552,949 Patients. Neurosurgery. 2024 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, N.A.; Mengistu, J.; Pillai, M.; Anand, G.; Sindelar, B.D. Outcomes following surgical intervention for acute hemorrhage in severe traumatic brain injury: a review of the National Trauma Data Bank. J Neurosurg. 2023 Jul 28;140, 552-559. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.K.; Krishnan, N.; Chyall, L.; Vega, P.; Hamidi, S.; Etemad, L.L.; Tracey, J.X.; Tarapore, P.E.; Huang, M.C.; Manley, G.T.; DiGiorgio, A.M. Socioeconomic and clinical factors associated with prolonged hospital length of stay after traumatic brain injury. Injury. 2023, 54, 110815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beijer, E.; van Wonderen, S.F.; Zuidema, W.P.; Visser, M.C.; Edwards, M.J.R.; Verhofstad, M.H.J.; Tromp, T.N.; van den Brom, C.E.; van Lieshout, E.M.M.; Bloemers, F.W.; Geeraedts, L.M.G. Jr. Sex Differences in Outcome of Trauma Patients Presented with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Multicenter Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2023 1;12, 6892. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowacki, J.C.; Jones, E.; Armento, I.; Hunter, K.; Slotman, J.; Goldenberg-Sandau, A. Don’t blame it on the alcohol! Alcohol and Trauma Outcomes: A 10-Year Retrospective Single-Center Study. Am J Surg. 2025 ;248:116444. 23 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riuttanen, A.; Jäntti, S.J.; Mattila, V.M. Alcohol use in severely injured trauma patients. Sci Rep. 2020 21;10, 17891. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villemure-Poliquin, N.; Costerousse, O.; Lessard Bonaventure, P.; Audet, N.; Lauzier, F.; Moore, L.; Zarychanski, R.; Turgeon, A.F. Tracheostomy versus prolonged intubation in moderate to severe traumatic brain injury: a multicentre retrospective cohort study. Can J Anaesth. 2023, 70, 1516–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumar, R.G.; Kesinger, M.R.; Juengst, S.B.; Brooks, M.M.; Fabio, A.; Dams-O’Connor, K.; Pugh, M.J.; Sperry, J.L.; Wagner, A.K. Effects of hospital-acquired pneumonia on long-term recovery and hospital resource utilization following moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2020, 88, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Santiago, L.A.; Oh, B.C.; Dash, P.K.; Holcomb, J.B.; Wade, C.E. A clinical comparison of penetrating and blunt traumatic brain injuries. Brain Inj. 2012, 26, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).