Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Additional Comments to the Choice of the Target Composition

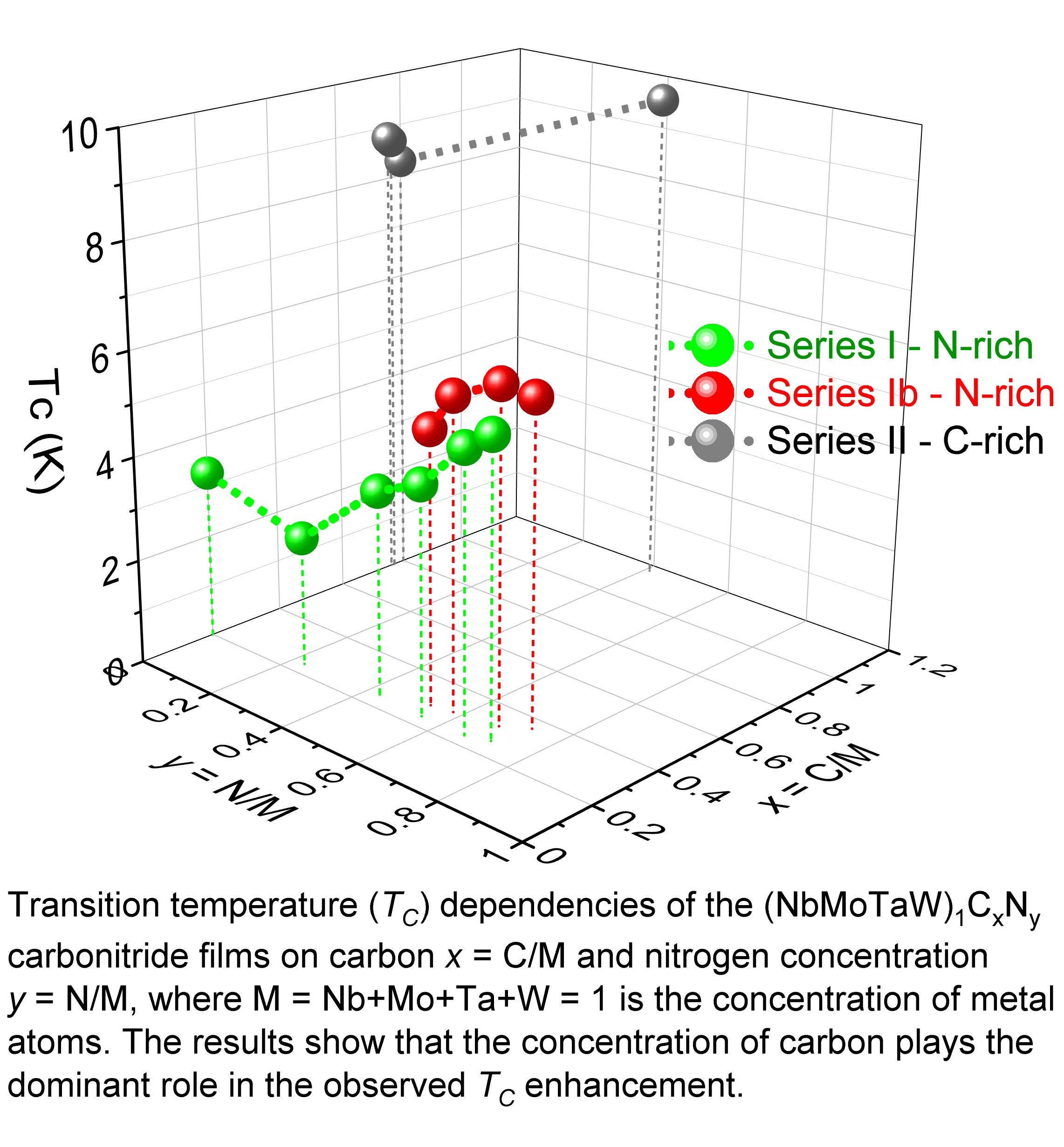

4. Results and Discussion

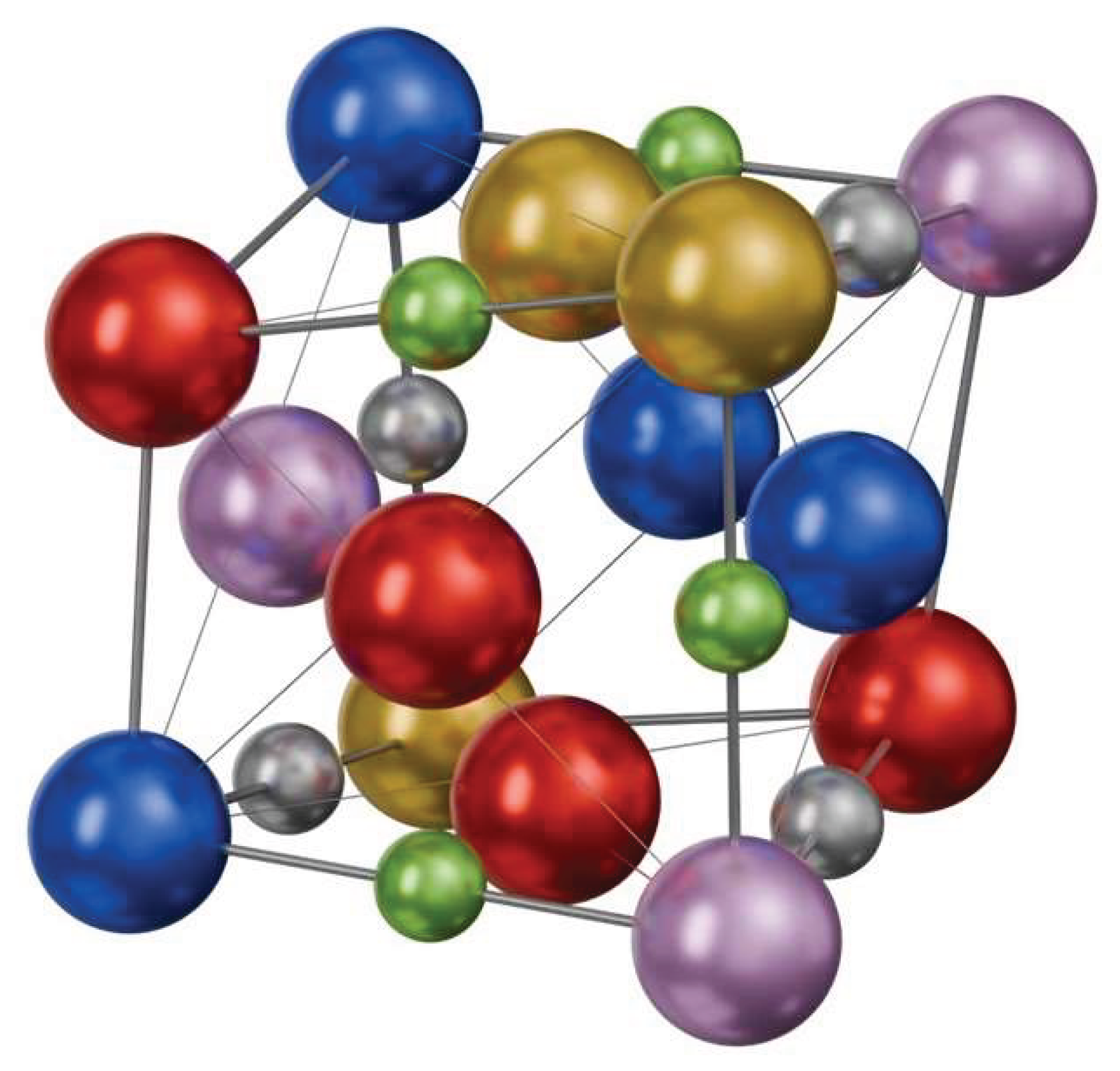

4.1. Composition and Structure

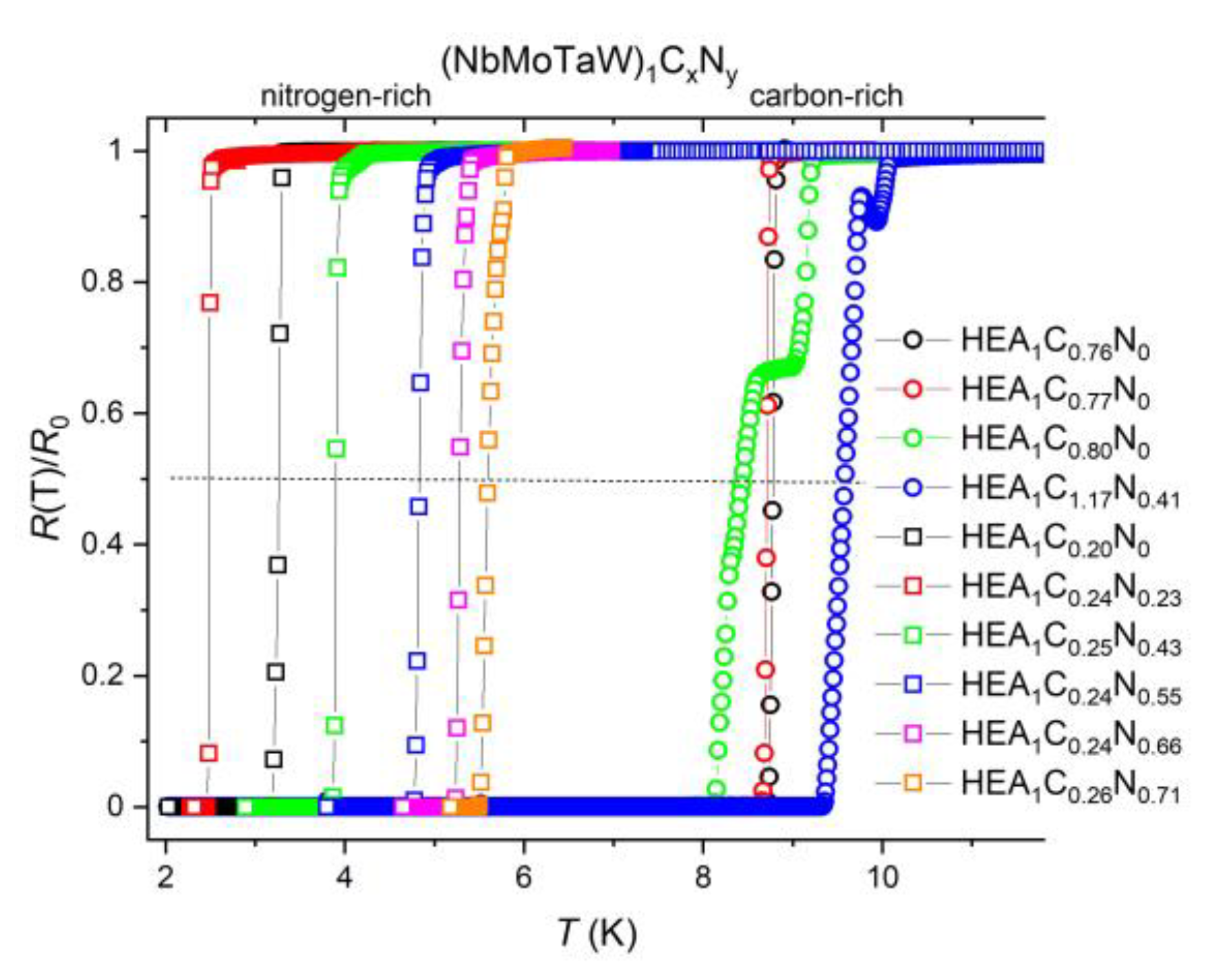

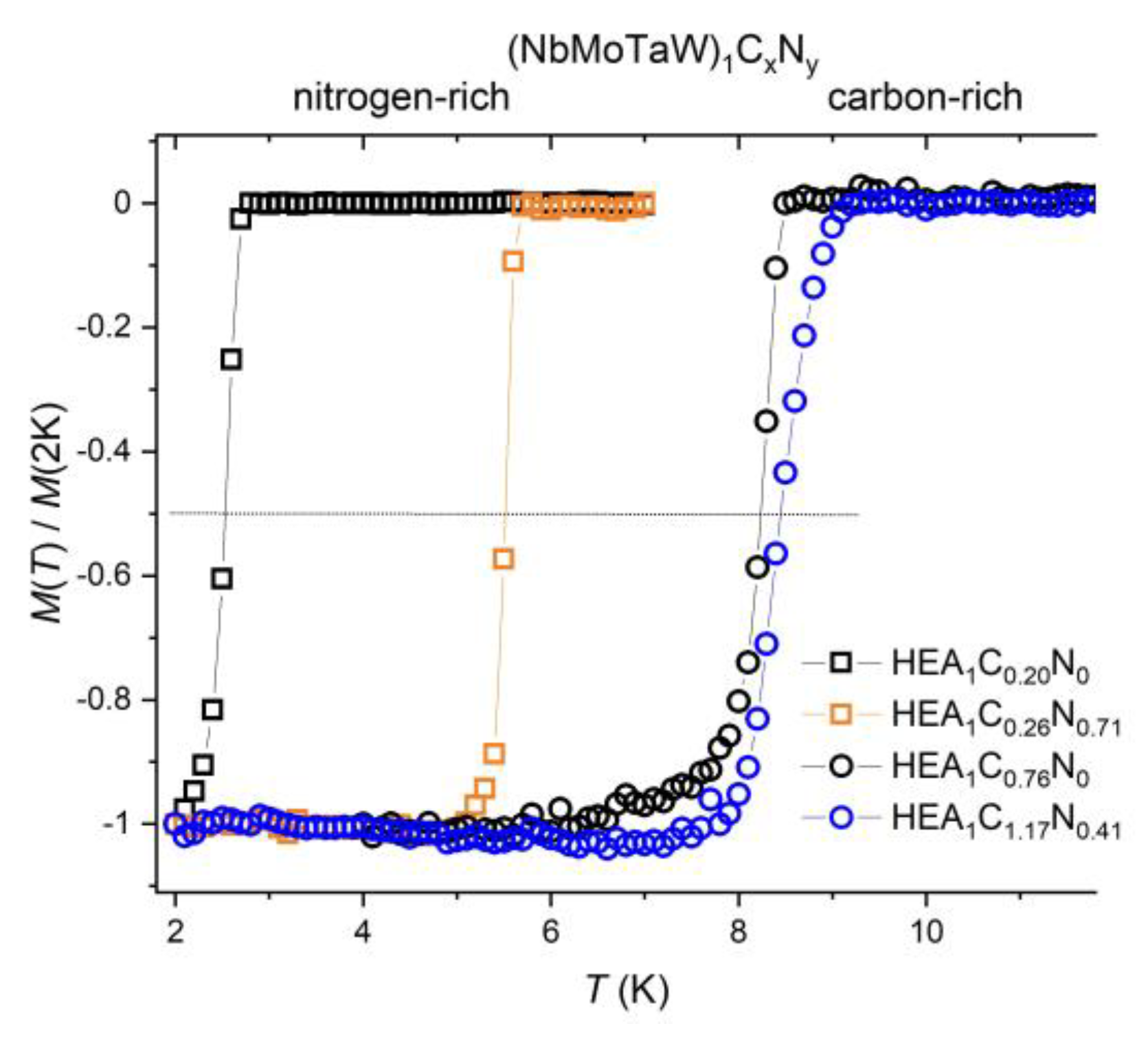

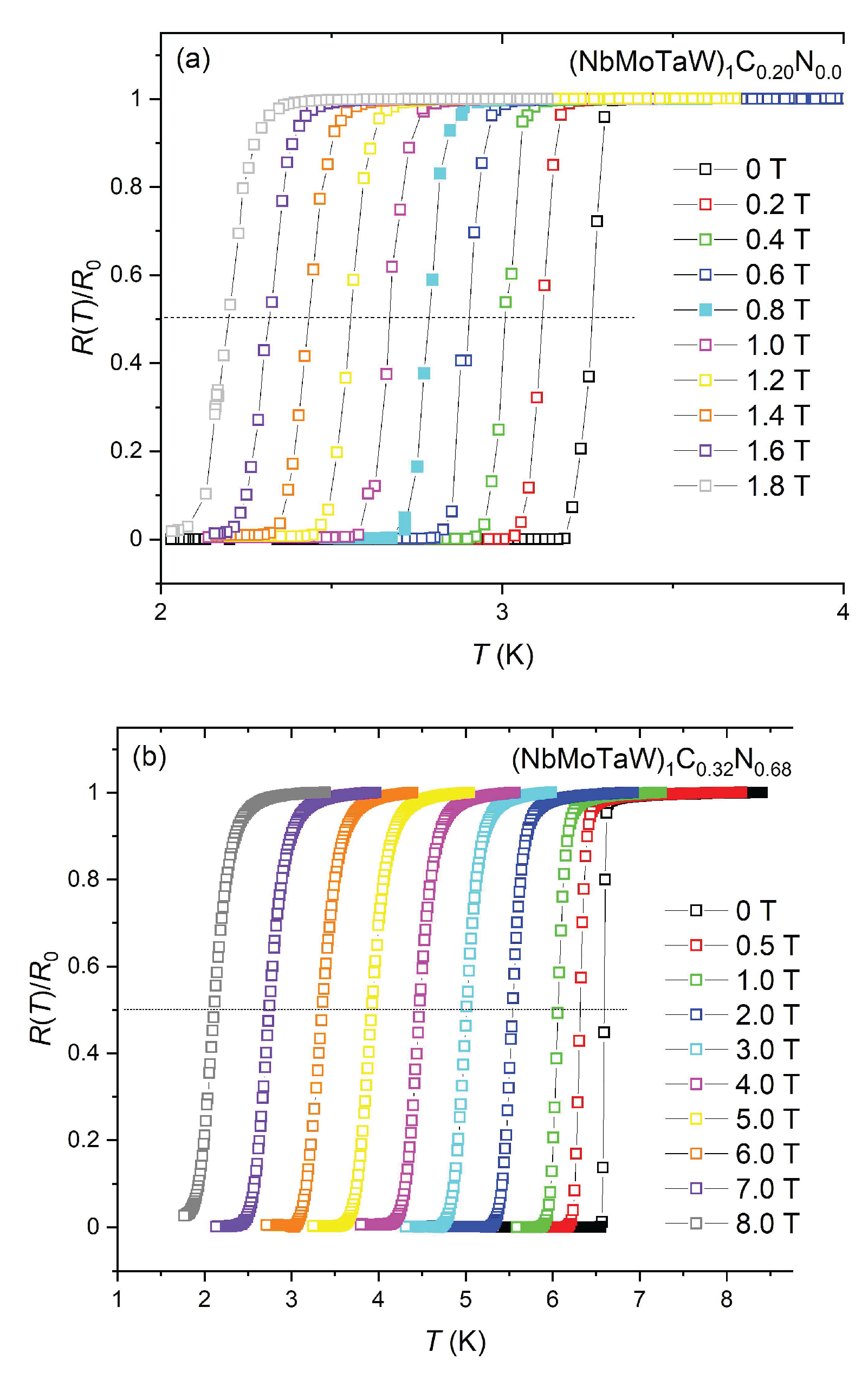

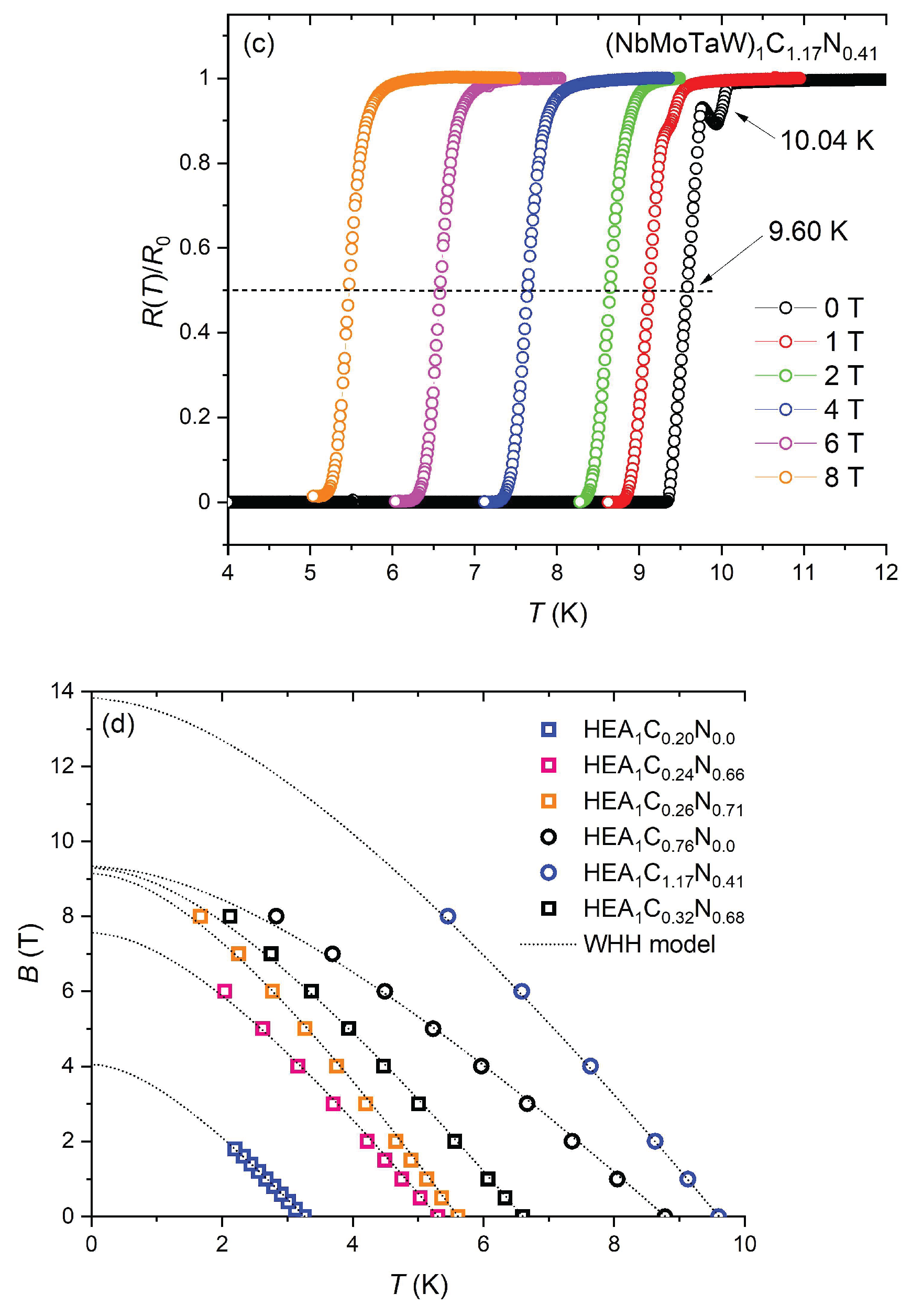

4.2. Resistance and Magnetization Results

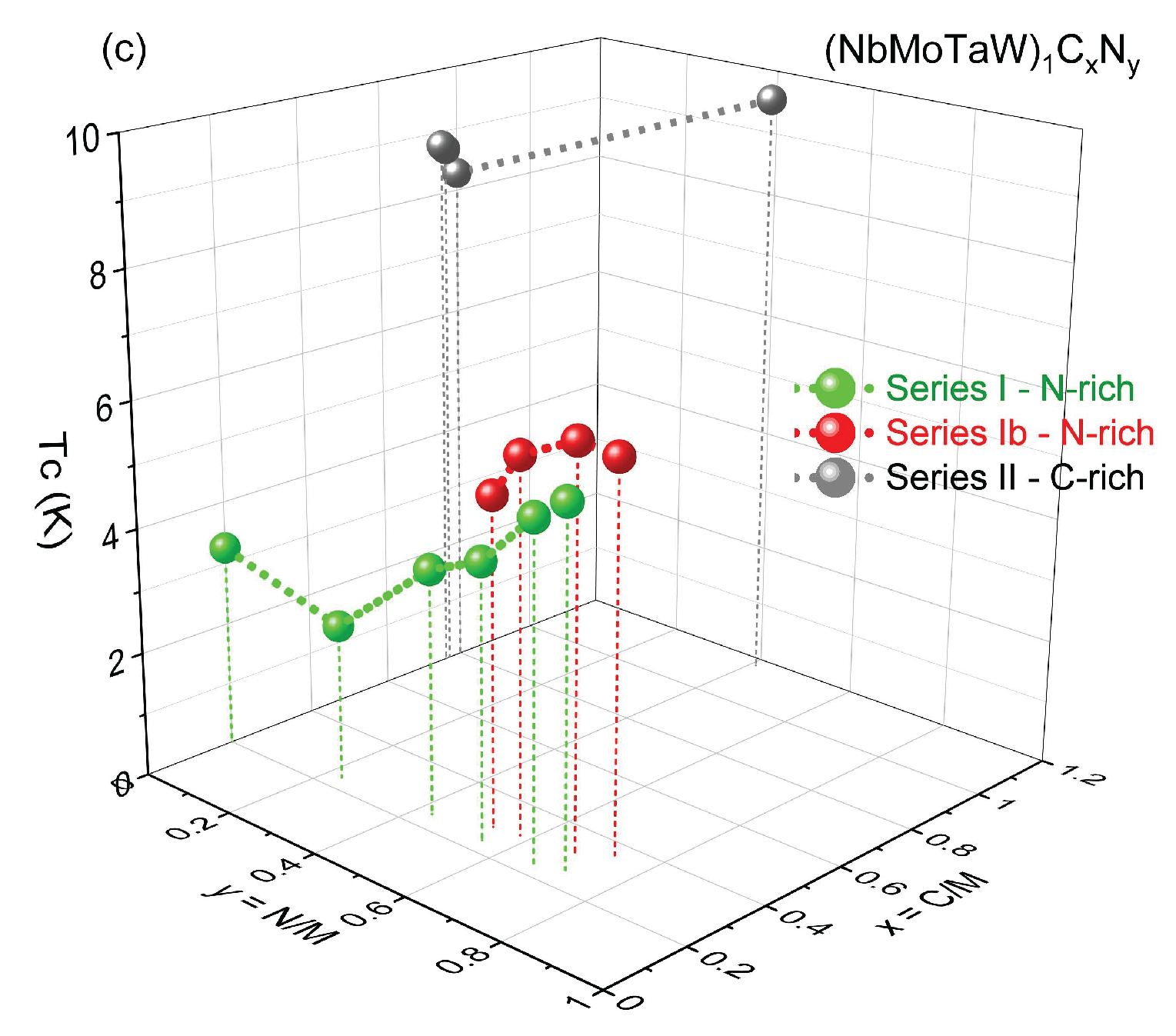

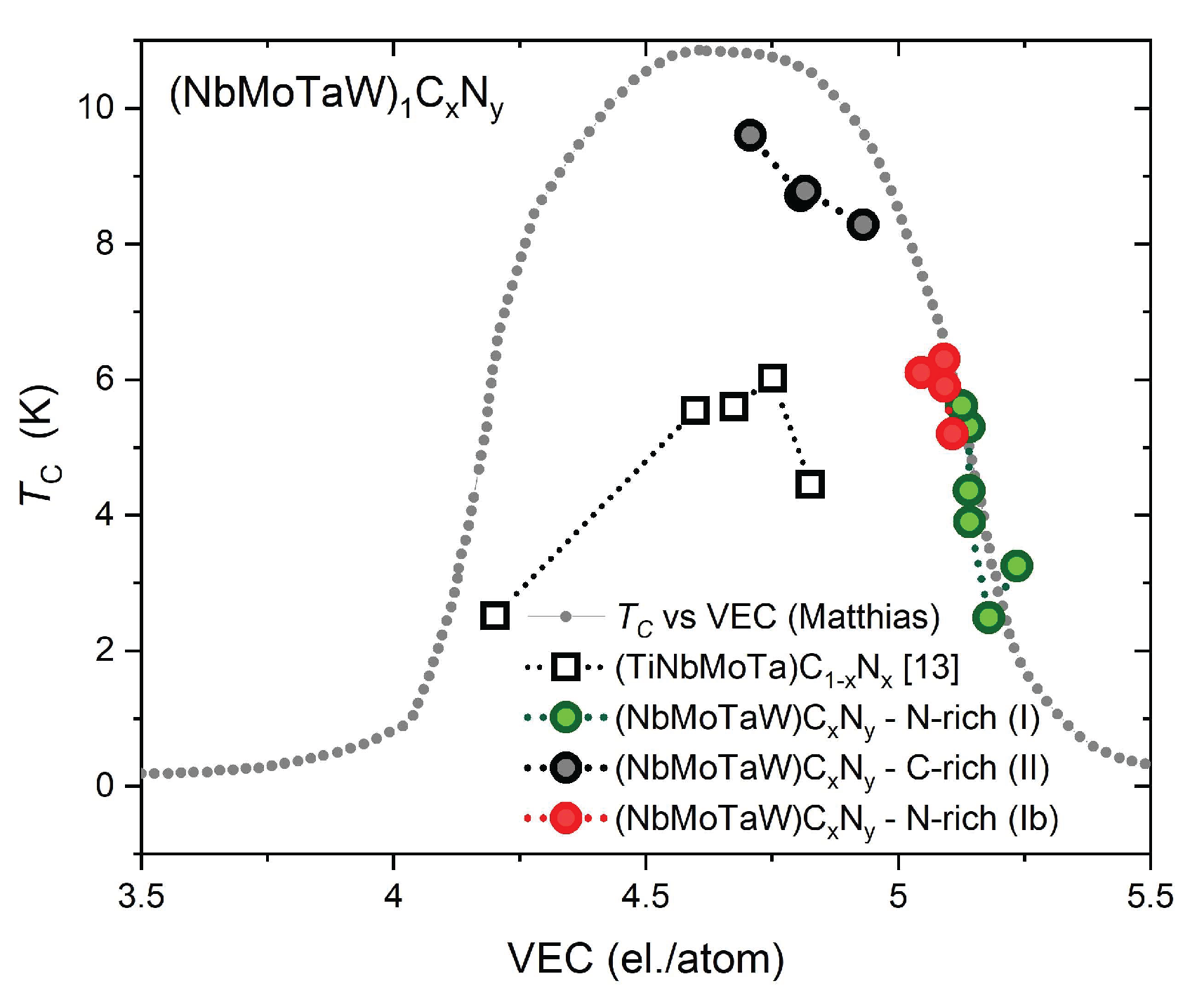

4.3. TC vs VEC - Transition Temperature Dependence on the Valence Electron Count

4.4. Upper Critical Magnetic Field Bc2

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Meissner, W.; Franz, H. Messungen mit Hilfe von flüssigem Helium IX. Supraleitfähigkeit von Carbiden and Nitriden. Z. Physik 1930, 65, 30–in German. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias, B.T.; Hulm, J.K. A search for new superconducting compounds. Phys. Rev. 1952, 87, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, L.E.; Wang, C.P.; Yen, G.M. Superconducting critical temperatures of non-stoichiometric transition metal carbides and nitrides. Acta Metall. 1966, 14, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willens, R.H.; Buehler, E.; Matthias, B.T. Superconductivity of the Transition-Metal Carbides. Phys. Rev. 1967, 159, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Jin, Q.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, K.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Guo, E-J.; Cheng, Z.G. Tuning superconductivity in vanadium nitride films by adjusting strain. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 224516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Shahbaz, M.; Rehman, H.; Khan, N. Superconductivity in transition metal carbides, TaC and HfC: A density functional theory study with local, semilocal, and nonlocal exchange-correlation functionals. Mater. Today Comm. 2024, 39, 108546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdastyh, M.V.; Postolova, S.V.; Proslier, T.; Ustavshikov, S.S.; Antonov, A.V.; Vinokur, V.M.; Mironov, A.Y. Superconducting phase transitions in disordered NbTiN films. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Ma, K.; Ruan, B.; Wang, N.; Hou, J.; Shan, P.; Yang, P.; Sun, J.; Chen, G.; Ren, Z.; von Rohr, F.O.; Wang, B.; Cheng, J. Nonmonotonic superconducting transition temperature and large bulk modulus in the alloy superconductor Nb4Rh2C1-δ. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 110, 214520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roedhammer, P.; Gmelin, E.; Weber, W.; Remeika, J.P. Observation of phonon anomalies in NbCxN1-x alloys. Phys. Rev. B 1977, 15, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkham, M. The BCS theory, In Introduction to superconductivity, 2nd ed.; Dover Publ., Mineola, New York, USA, 2004; Chapter 3, p. 43, ISBN-13: 978-0-486-43503-9, ISBN-10: 0-486-43503-2.

- Akrami, S.; Edalati, P.; Fuji, M.; Edalati, K. High-entropy ceramics: Review of principles, production and applications. Mater. Sci. & Engineer. R 2021, 146, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Wang, Z.; Song, J.; Lin, G.; Guo, R.; Luo, S-C.; Guo, S.; Li, K.; Yu, P.; Zhang, C.; Guo, W-M.; Ma, J.; Hou, Y.; Luo, H. Discovery of the High-Entropy Carbide Ceramic Topological Superconductor Candidate (Ti0.2Zr0.2Nb0.2Hf0.2Ta0.2)C. Adv. Funct. Mater 2023, 33, 2301929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Hu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Boswell, M.; Xie, W.; Li, K.; Li, L.; Yu, P.; Zhang, C.; Guo, W-M.; Yao, D-X.; Luo, H. Superconductivity and non-trivial band topology in high-entropy carbonitride (Ti0.2Nb0.2Ta0.2Mo0.2W0.2)C1-xNx. The Innov. Mater 2023, 1, 100042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pristáš, G.; Gruber, G.C.; Orendáč, M.; Bačkai, J.; Kačcmarčík, J.; Košuth, F.; Gabáni, S.; Szabó, P.; Mitterer, C.; Flachbart, K. Multiple transition temperature enhancement in superconducting TiNbMoTaW high entropy alloy films through tailored N incorporation. Acta Mater. 2024, 262, 119428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senkov, O.N.; Wilks, G.B.; Miracle, D.B.; Chuang, C.P.; Liaw, P.K. Refractory high entropy alloys. Intermetallics 2010, 18, 1758–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Li, Y.; Qi, Y.; Wang, B. Review on Preparation Technology and Properties of Refractory High Entropy Alloys. Materials 2022, 15, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, J.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Huo, D.; Liu, C. A review of high-entropy ceramics preparation methods, properties in different application fields and their regulation methods. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 1083–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Cava, R.J. High-entropy alloy superconductors: status, opportunities, and challenges. Phys. Rev. Mat. 2019, 3, 090301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idczak, R.; Nowak, W.; Rusin, B.; Topolnicki, R.; Ossowski, T.; Babij, M.; Pikul, A. Enhanced Superconducting Critical Parameters in a New High-Entropy Alloy Nb0.34Ti0.33Zr0.14Ta0.11Hf0.08. Materials 2023, 16, 5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, J.; Hamamoto, S.; Ishizu, N. Cutting Edge of High-Entropy Alloy Superconductors from the Perspective of Materials Research. Metals 2020, 10, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Li, L.; Li, K.; Chen, R.; Luo, H. Recent advances in high-entropy superconductors. NPG Asia Materials 2024, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukunami, Y.; Yamashita, A.; Goto, Y.; Mizuguchi, Y. Synthesis of RE123 high-Tc superconductors with a high-entropy-alloy-type RE site. Physica C: Supercond. 2020, 572, 1353623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbane, F.M.; Habig, P.S. Superconducting transition temperatures of reactively sputtered films of tantalum nitride and tungsten nitride. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. 1975, 12, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, J. Strong Electron–Phonon Coupling in 3D WN and Coexistence of Intrinsic Superconductivity and Topological Nodal Line in Its 2D Limit, Phys. Stat. Solidi RRL 2022, 16, 2100477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofaj, F.; Hviščová, P.; Pristáš, G.; Dobrovodský, J.; Albov, D.; Lisnichuk, M.; Gabáni, S.; Flachbart, K. The effects of carbon and nitrogen incorporation on the structure, mechanical properties and superconducting transition temperature of (NbMoTaW)100-z(CN)z coatings. Thin Sol. Films 2025, 823, 140704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrovodský, J.; Vaňa, D.; Beňo, M.; Lofaj, F.; Riedlmajer, R. Ion Beam Analysis including ToF-ERDA of complex composition layers, J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2712, e012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, U.; Lewin, E. Carbon-containing multi-component thin films. Thin Sol. Films 2019, 688, 137411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, E. Multi-component and high-entropy nitride coatings - A promising field in need of a novel approach. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 127, 160901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häglund, J.; Fernández Guillermet, A.; Grimvall, G.; Körling, M. Theory of bonding in transition-metal carbides and nitrides. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 11685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, X.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, R.; He, D.; Qin, J.; Zhu, J.; Han, J.; Wang, L.; Mao, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y. Synthesis, Crystal structure, and elastic properties of novel tungsten nitrides. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Hu, Q.; Ng, C.; Liu, C.T. More than entropy in high-entropy alloys: Forming solid solutions or amorphous phase. Intermetallics 2013, 41, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kube, S.A.; Sohn, S.; Uhl, D.; Datye, A.; Mehta, A.; Schroers, J. Phase selection motifs in High Entropy Alloys revealed through combinatorial methods: Large atomic size difference favors BCC over FCC. Acta Mater. 2019, 166, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Mater. 2017, 122, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Marel, D. Thoughts about boosting superconductivity. Physica C: Supercond 2025, 632, 1354688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, T.R.; Belitz, D. Suppression of superconductivity by disorder. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 68, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, A.P.; Haselwimmer, R.K.W.; Tyler, A.W.; Lonzarich, G.G.; Mori, Y.; Nishizaki, S.; Maeno, Y. Extremely Strong Dependence of Superconductivity on Disorder in Sr2RuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobota, P.; Topolnicki, R.; Ossowski, T.; Pikula, T.; Pikul, A.; Idczak, R. Superconductivity in the high-entropy alloy (NbTa)0.67(MoHfW)0.33. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 106, 184512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutowska, S.; Kawala, A.; Wiendlocha, B. Superconductivity near the Mott-Ioffe-Regel limit in the high-entropy alloy superconductor (ScZrNb)1−x(RhPd)x with a CsCl-type lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 064507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthias, B.T. Empirical relation between superconductivity and the number of valence electrons per atom. Phys. Rev. 1955, 97, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, T.; Shi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Wei, Z.; Qin, M.; Yuan, J.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhu, B.; Huang, R.; Jiang, K.; Zhou, W.; Wang, N.; Hu, J.; Li, Y.; Jin, K.; Zhao, Z. Emergence of superconducting dome in ZrNx films via variation of nitrogen concentration. Sci. Bull. 2023, 68, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werthamer, N.R.; Helfand, E.; Hohenberg, P.C. Temperature and Purity Dependence of the Superconducting Critical Field, Hc2. III. Electron Spin and Spin-Orbit Effects. Phys. Rev 1966, 147, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.-Y.; Gornicka, K.; Lefevre, R.; Yang, Y.; Rønnow, H.M.; Jeschke, H.O.; Klimczuk, T.; von Rohr, F.O. Superconductivity with High Upper Critical Field in the Cubic Centrosymmetric η-Carbide Nb4Rh2C1-δ. ACS Mater. Au 2021, 1, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Womack, F.N.; Young, D.P.; Browne, D.A.; Catelani, G.; Jiang, J.; Meletis, E.I.; Adams, P.W. Extreme high-field superconductivity in thin Re films. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 024504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clogston, A.M. Upper limit for the critical field in hard superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1962, 9, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, T.; McNiff Jr., E.; Foner, S.; Beasley, M. Pauli paramagnetic limiting, and material parameters of Nb3Sn and V3Si. Phys. Rev. B 1979, 19, 4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| sample composition (sample label in [25]), measurements |

crystal structure |

R300/R0 (RRR) |

TC [K] |

Bc2(0) [T] |

VEC el./at. |

| Series I | |||||

| (Nb0.23Mo0.24Ta0.26W0.27)1.0C0.20N0.0 ( 4ME-C(0)-0N-a ), R(T), M(T) |

bcc | 1.004 | 3.25 | 4.05 | 5.235 |

| (Nb0.24Mo0.25Ta0.25W0.26)1.0C0.24N0.23 ( 4ME-C(0)-1N ), R(T) |

bcc with fcc |

0.989 | 2.49 | 2.70 | 5.180 |

| (Nb0.24Mo0.25Ta0.25W0.26)1.0C0.25N0.43 ( 4ME-C(0)-2N ), R(T) |

fcc | 0.975 | 3.90 | 3.94 | 5.141 |

| (Nb0.24Mo0.26Ta0.25W0.25)1.0C0.24N0.55 ( 4ME-C(0)-3N ), R(T) |

fcc | 0.940 | 4.83 | 6.55 | 5.140 |

| (Nb0.24Mo0.26Ta0.24W0.26)1.0C0.24N0.66 ( 4ME-C(0)-4N ), R(T) |

fcc | 0.905 | 5.30 | 7.57 | 5.140 |

| (Nb0.24Mo0.26Ta0.24W0.26)1.0C0.26N0.71 ( 4ME-C(0)-5N ), R(T), M(T) |

fcc | 0.847 | 5.61 | 9.16 | 5.126 |

| Series Ib | |||||

| (Nb0.20Mo0.29Ta0.25W0.26)1C0.29N0.53 ( new, with N-flow 3N ), M(T) |

fcc | n.d. | 5.2 | n.d. | 5.108 |

| (Nb0.20Mo0.29Ta0.25W0.26)1C0.30N0.58 ( new, with N-flow 4N ), M(T) |

fcc | n.d. | 5.9 | n.d. | 5.092 |

| (Nb0.20Mo0.29Ta0.25W0.26)1C0.32N0.68 ( new, with N-flow 5N ), M(T), R(T) |

fcc | 0.832 | 6.3 | 9.30 | 5.091 |

| (Nb0.22Mo0.28Ta0.24W0.26)1C0.36N0.73 ( new, with N-flow 7N ), M(T) |

fcc with hcp | n.d. | - | - | 5.046 |

| Series II | |||||

| (Nb0.31Mo0.18Ta0.25W0.26)1.0C0.76N0.0 ( 4ME-C(500)-0N-a ), R(T), M(T) |

fcc | 1.001 | 8.78 | 9.34 | 4.816 |

| (Nb0.31Mo0.18Ta0.25W0.26)1.0C0.77N0.0 ( 4ME-C(600)-0N-b ), R(T) |

fcc | 0.939 | 8.71 | 8.70 | 4.807 |

| (Nb0.35Mo0.17Ta0.23W0.25)1.0C0.80N0.0 ( 4ME-C(700)-0N-c ), R(T) |

fcc | 0.989 | 8.28 (~9.2) | n.d. | 4.931 |

| (Nb0.32Mo0.18Ta0.24W0.26)1.0C1.17N0.41 ( 4ME-C(600)-2N ), R(T), M(T) |

fcc | 0.939 | 9.60 (~10.1) |

13.83 | 4.707 |

| (Nb0.32Mo0.19Ta0.24W0.25)1.0C1.18N1.13 ( 4ME-C(600)-5N ), R(T) |

fcc with C-clusters |

0.599 | - | - | 4.771 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).