1. Introduction

Wetlands are defined as valuable ecosystems comprising various types of water bodies, such as marshes, peatlands, swamps, lakes, etc. [

1]. These ecosystems are of paramount importance to the planet, playing a pivotal role in maintaining ecological functions [

2]. However, there has been a decline and deterioration of wetlands due to various factors, including changes in land use, pollution from agriculture and industry, overgrazing, droughts, urbanization processes, groundwater overexploitation, and the proliferation of invasive species [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The degradation of wetlands exerts a detrimental influence on biodiversity, local climate, ecological security, and human health [

4,

5], thus necessitating the restoration of degraded wetlands. In this sense, many governments have increased their interest in addressing this problem, especially in developing countries where wetlands are deteriorating rapidly [

6,

7].

In some countries, such as many in Latin America, Asia and Africa, the adverse environmental impacts of wetland degradation are compounded by the associated decline in public health [

7,

8,

9]. The consequences of this phenomenon are manifold, impacting human health in direct relation to its impact on food, water and climate security [

5]. Furthermore, the spread of water-borne diseases and vulnerability to natural disasters are also exacerbated [

10].

To meet the challenge of environmental degradation and the effects on public health, various conservation and management measures have been implemented based on optimizing resource consumption and management, sustainable development, the application of green technologies and public participation in progressive achievements [

11,

12,

13,

14].

Despite the growing interest in the promotion of management measures to reduce the degradation of wetlands and to address their effects on public health, only a few studies have carried out an economic valuation for implementing these measures in wetlands [

15,

16,

17]. Whilst economic valuations have been executed through the implementation of stated preference methodologies, including contingent valuation [

18], to ascertain the economic value of implementing management and conservation measures in protected natural areas [

19], restoration of rivers [

20], high-value agricultural ecosystems [

21], or certain wetlands [

15,

16,

17], there is a paucity of such studies concerning the economic valuation of sustainable management of wetlands in some areas, such as most of the Latino American countries [

17], and the direct effect of wetland degradation on public health, with none study in Central and South America [

18]. The development of action planning that integrates and promotes environmental conservation and health damage prevention strategies requires an understanding of the economic value and factors that may influence the demand for wetland management measures. It is imperative to comprehend the social perception of wetland mismanagement and the influence of socioeconomic factors on this behavior, as well as the temporal variation in social perception.

The objective of this work is to determine the economic value of wetland degradation in order to achieve sustainable wetland management in Mexico, one of the countries in the world where the role of lakes is of crucial importance in environmental and water resources management [

22]. Furthermore, this work seeks to analyze the socioeconomic and temporal factors that influence the demand for improved management. For the purposes of this work, Cuitzeo lake in Mexico has been selected as a case study. This lake is an emblematic wetland that is undergoing a process of ecological deterioration in both water quantity and quality. This has had a direct negative effect on the health of the population living around the wetland.

We examine the extent to how can determine the economic value for wetland degradation to answer the following research questions: (1) Is there a willingness to accept financial compensation for the public health problems resulting from the environmental deterioration of the lake? (2) Is there a willingness to pay for management measures to improve the environmental conditions of the lake? (3) What factors influence the willingness to accept and the willingness to pay?

The utilisation of the contingent valuation method represents a substantial contribution to the extant literature by offering insight into the prevailing economic value for sustainable wetland management. Therefore, this work seeks to generate scientific knowledge through three key contributions: (I) Test the economic value of the population health of inhabitants living near the wetland, (II) Test the economic value of management measures that promote sustainable development in the wetland area, and (III) Test the factors influencing the behavior of individuals towards the economic valuation of the lake.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background on Economic Value of Wetlands

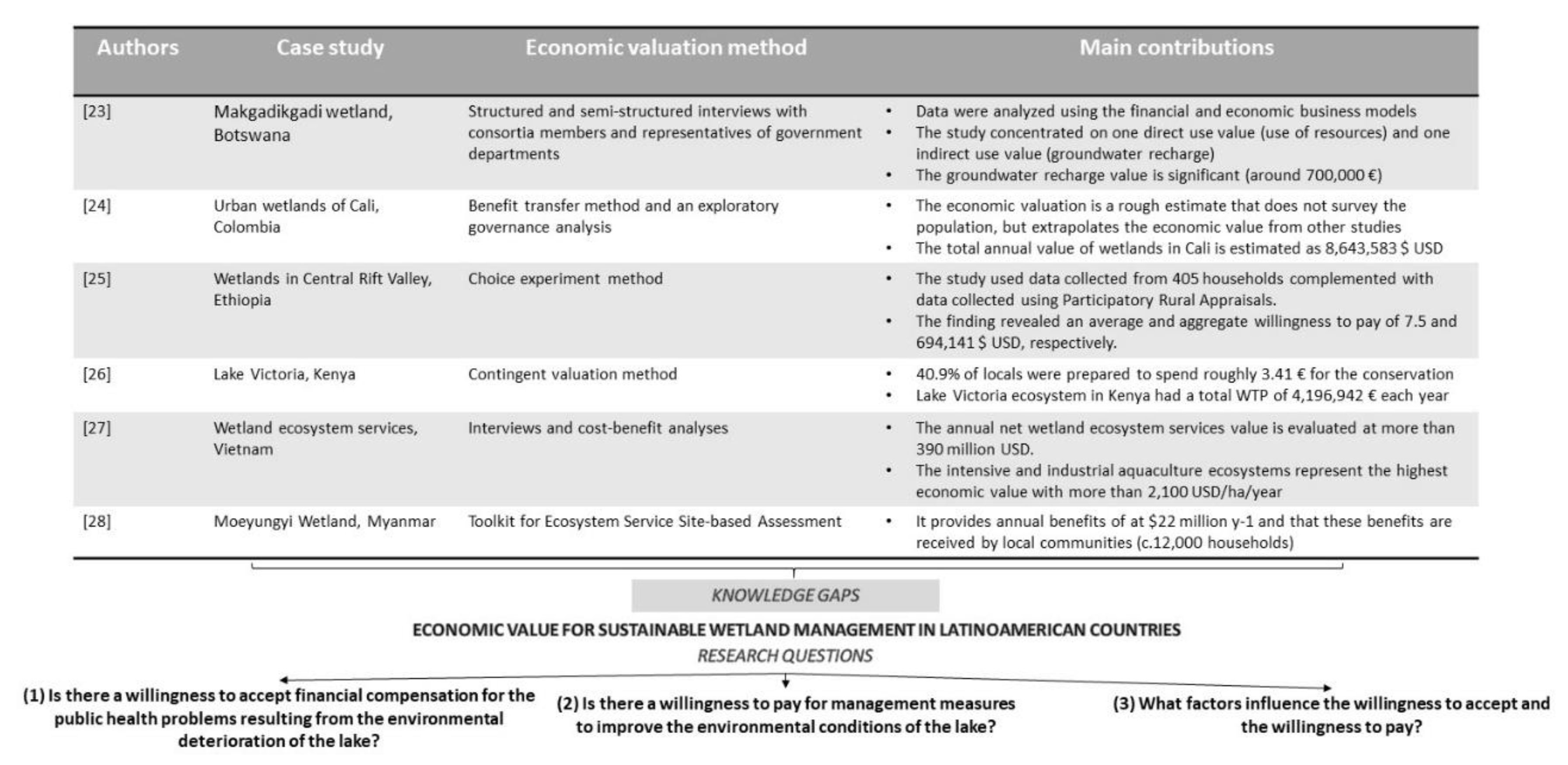

Despite the existence of studies that have conducted economic valuations in wetlands, these are predominantly focused on European and North American countries, thus exhibiting a dearth of research in Latin American countries, with only one study (see

Figure 1). By way of summary,

Figure 1 presents case studies that demonstrate analogous characteristics to those observed in Latin American countries regarding social and economic indicators, with a particular focus on Africa and Asia.

2.2. Case Study

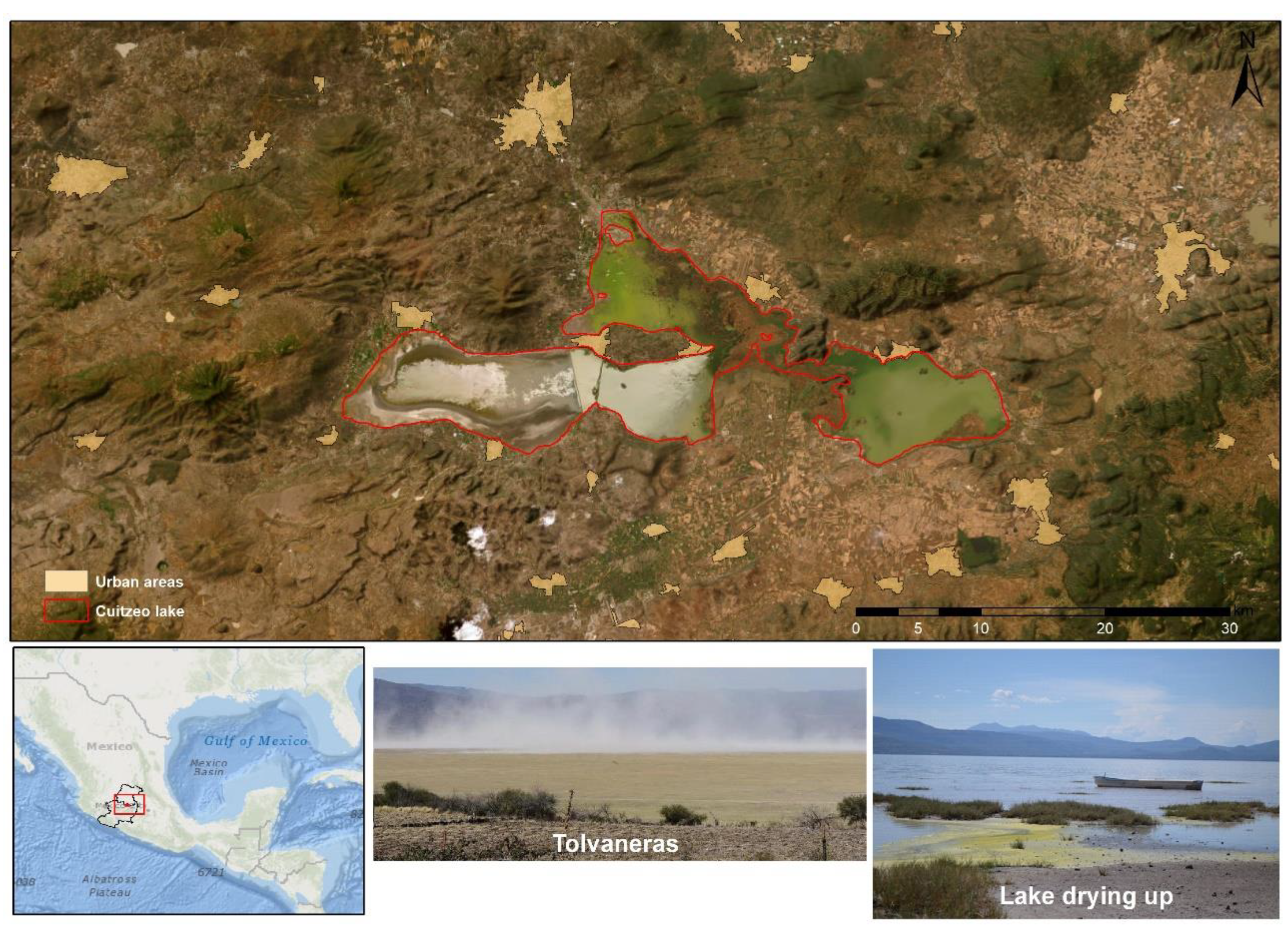

The Cuitzeo lake (

Figure 2), situated in the northern region of the Mexican state of Michoacán, has been selected as a case study for analysis. This wetland is indicative of a process of ecological deterioration, which is evident in the drying up of the western part of the ecosystem. Environmental deterioration is principally attributed to socioeconomic activities in the surrounding area; the intense urbanization process, associated with population growth, which exacerbates the problems of water availability and quality in the lake; wastewater discharges from urban areas; groundwater exploitation to meet demand for agricultural and urban uses; and deforestation [

28].

Given the topographical characteristics of the lake, which is characterized by its shallowness and an average depth of 30 cm, it undergoes a process of low water during the initial months of the year (average monthly precipitation of 5.7 mm until the end of March). This process is accompanied by high evaporation, which leads to the accumulation of water pollutants in the lake sediments and their subsequent integration into the dry soil. The prevailing winds and their rapid movement are conducive to the formation of “tolvaneras” or “dust storms” which are characterized as swirls of dust or sand [

29]. These phenomena have been observed to envelop the populations residing along the western periphery of Cuitzeo lake, exerting a deleterious effect on public health. Their frequency has increased over time, while in the period 2010-2020 a duration of 4 months was recorded, currently these phenomena exceed 6 months in duration [

30]. Consequently, dust storms have a detrimental effect on the riparian areas west of Cuitzeo lake, where there has been a recent increase in respiratory, gastrointestinal and dermatological diseases [

28,

29].

In relation to dust storms, in the last decade there have been 97,026 cases of acute respiratory infections and 11,288 cases with intestinal infections [

31]. Thus, the different socioeconomic activities of the population around the lake have caused not only an environmental problem but also a public health problem for the nearest populations. The record of infections associated with the ecological deterioration of Cuitzeo lake provides elements to justify the existence of a public health problem in the study area and which currently has not been consistently addressed due to the lack of knowledge regarding the economic value it represents for the population.

2.3. Methods

The contingent valuation method [

18,

19,

20] was the primary methodology employed in this work. This is a stated preference approach, whereby respondents are directly asked to express their willingness to accept (WTA) by assuming changes in well-being generated by the loss of a benefit or their willingness to pay (WTP) for the improvement of goods/services. Thus, the monetary value of an environmental asset can be determined by creating a hypothetical market and estimating the Total Economic Value. The Total Economic Value includes both use and non-use values, and consequently, the public health costs resulting from the degradation of a wetland, or the benefits derived from the implementation of management measures.

When performing the univariate analyses of the WTA and WTP, the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test was used to test for significant differences between two samples taken at two different time periods.

Furthermore, multivariate analyses were conducted, with the development of models with

logit and

tobit specifications to identify the factors that determine the WTA and WTP of the population [

22].

2.4. Data Collection

The primary data was collected via a structured questionnaire comprising twenty-five questions, which were divided into three sections.

The first section focused on issues related to the context and the existing problem at the Cuitzeo lake.

The second section focused on the economic valuation of the wetland. For this purpose, two different types of questions were asked.

On the one hand, the WTA was asked for compensation for the damage caused by the degradation of the lake on the public health of the population near the wetland. The payment vehicle selected in the pilot survey is a voucher for medical or pharmaceutical expenses in exchange for damage caused by the environmental deterioration of the lake. The binary question of the WTA was formulated as follows: Would you be willing to accept monthly financial compensation in the form of a medical or pharmaceutical voucher in exchange for the damage caused by the environmental deterioration of the lake due to the “tolvaneras”? In the case of an affirmative answer the respondents had to state the minimum amount of money they would be willing to receive for their household (WTAT). For this purpose, four starting points of 500/1,000/1,500/2,000$ MXN/household/month were proposed (100 $ MXN = 4.66 € on January 30, 2025), asking respondents for their minimum WTA considering these references payment. Whether the answer was yes or no, respondents were asked to indicate the minimum amount they would be willing to accept damage caused by wetland degradation by using an open-ended question. In the case of refusing compensation in the WTA binary question, the motivations expressed by respondents were identified, categorizing them into protests and non-protests.

On the other hand, the respondents were asked to show their WTP for management measures that would promote lake remediation and the reduction of dust storms. The binary WTP question was formulated as follows: To carry out management measures to improve the environmental conditions of the lake, would you be willing to make a payment through the monthly water bill? In the case of an affirmative answer the respondents had to state the maximum amount of money they would be willing to pay for their household (WTPT). For this purpose, a specific amount of money of 100 $ MXN/household/month was proposed, asking respondents for their maximum WTP considering this reference payment. Respondents were also asked to rate on a Likert scale from 1 to 5 a number of management measures, which respondents would be willing to pay for. In the case of refusing the payment in the WTP binary question, the motivations expressed by respondents were identified. In the case of WTP=0 in the WTPB question, the motivations expressed by the individuals were identified, categorizing them into protests and non-protests.

The third section included information based on the socio-economic characteristics and environmental behavior of the respondents, which was measured by ecological commitment indices with Likert scales 1-5 [

32].

From a pilot survey of 30 respondents in October 2017, the final survey was conducted between February-April 2018. The 846 households around Cuitzeo lake were considered for the WTA question and the 13,542 households across the region for the WTP question. Thus, a sample of 272 respondents was obtained, which for a 95% confidence level for a dichotomous variable, resulted in a sampling error of 5.9 % for intermediate proportions and 3.6 % for extreme proportions. In addition, we wanted to check if there was a variation in the economic valuation over the last few years, given that Cuitzeo lake has not experienced any improvement in its environmental status, so a second survey was carried out in March 2025 to test the temporal variation of the economic value by surveying 35 respondents. This resulted in a full pooled sample of 306 respondents. To demonstrate significant differences in the samples, a binary time variable (Year 2025 = 1) was created to capture the period effect in the univariate and multivariate analyses of WTA and WTP. The monetary variables of the WTA and WTP, as well as the household and personal incomes of the respondents were updated at constant prices of 2025 for appropriate comparison.

2.5. Sample Description

The descriptive data collected from the survey has enabled the composition of a profile of the average respondent to be determined. A Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test was performed for all respondent descriptive and socioeconomic variables and showed that there were no significant differences between the 2018 and 2025 respondents.

It has been found that the average respondent is a man (78 % of cases) aged 50, hasn’t received a university education (completed or in progress) and is employed in 94% of cases. The most prevalent household size is four, with an average monthly family income of 2,948

$ MXN (see Appendix Table A1). It has been established that the characteristics of the surveys are largely consistent with the census values for the target population [

33].

More than 90% of respondents are concerned that the wetland will disappear in the future and become a source of infection for the population. Respondents also rated on a scale of 1-5 which actors should solve the environmental deterioration of the lake and address the “tolvaneras”, expressing a desire for collaboration between the federal government (4.95 out of 5), state government (4.82), municipal government (4.69), private companies (4.71), NGOs (4.83) and citizens (4.94). The respondents also indicated a high affective ecological commitment (4.89 out of 5), a medium verbal commitment of willingness to act (3.89), and a low real commitment (1.34) (see

Table A1).

3. Results

3.1. Willingness to Accept Analysis

For the willingness to accept (WTA) analysis, both samples from 2018 and 2025 were considered, and a Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test was performed to verify the existence of significant differences in the total WTA values. As there were no significant differences observed during this period, all respondents who participated in the hypothetical market were jointly considered in the analysis (see

Table 1).

From the WTA question, 89.54 % of the sample (274 respondents) showed their willingness to receive financial compensation (WTA > 500/1,000/1,500/2,000 $MXN/household/month), while the remaining 10.46 % (32 respondents) were not willing to accept. Furthermore, respondents who declined to accept remuneration for the damage caused to the lake were invited to provide justification for their decision, being able to point out more than one reason. Practically all of them (31 respondents) stated that the reason for their non-participation was their belief that the measure was ineffective in addressing the underlying issue. More than half (18 respondents) cited the perceived inadequacy of the payment method as a reason for non-participation, and one third (10 respondents) cited a lack of credibility. These final two responses were categorized as protest zeros. This finding suggests that 22 of the 32 respondents with a null WTA corresponded to protesting zeros, with the remaining 10 being real zeros. The hypothetical market is comprised of respondents with WTA>0 and real zeros and is therefore composed of 284 households.

The mean WTA is 887

$MXN/household/month, with a maximum of 2,500

$MXN/household/month and a minimum of 0

$MXN/household/month (corresponding to real zeros) (

Table 1).

From the mean individual WTA, it is possible to estimate the aggregate total WTA for the population living near Cuitzeo lake (846 households), which would be the total economic value, a proxy of the social benefit derived from the public health problems caused by the degradation of the lake. This gives a total economic value of 750,081 $MXN/household/month (around 9,000,966 $MXN/year).

After demonstrating that there are no significant differences in WTA values for two different samples over time, multivariate analyses were performed for binary and total WTA considering pooled samples.

The factors explaining the WTA voucher for medical or pharmaceutical expenses in exchange for the damage caused by lake degradation, identified by multivariate analysis, were measured using variables grouped into socioeconomic characteristics and environmental commitment index (

Table A1). The interactions of these variables were also included as possible explanatory factors.

The factors to explain willingness or not to accept, so called binary WTA (WTAB), were identified with a

logit model (

Table 2), where WTAB takes a value of 1 if the respondent's response is positive (89.54 %) and 0 null (10.46 %). The

logit model presents a good fit (96.5 % of Correct Classification - CPC) and show no collinearity problems (VIF < 10).

Two significant variables were found in the

logit model (

Table 2). Given their marginal effects, the probability of WTA voucher increases by 0.1% when the respondent is one year older. In addition, if the respondent is a woman reduces the probability of WTA by 4.3 %.

As for the total willingness to accept (WTAT), modeling was performed with

tobit estimation censored at 0 (

Table 3).

The explanatory variables to the amount of the medical voucher were different from those of the previously estimated logit model. Starting from a value of almost 2,000 $MXN/household/month, the fact of being active workers or considering the importance to private companies in solving the problem of Cuitzeo lake reduces this compensation. Thus, given the marginal effects evaluated for the sample means, being an active worker reduces WTA by 790 $MXN/household/month, while giving one more unit of importance to private companies reduces WTA by 68 $MXN/household/month.

Finally, it should be noted that in both models (logit and tobit) the time variable Year 2025 did not appear significant, corroborating the univariate analyses of the WTA, which show that there are no significant differences between the samples of both years.

3.2. Willingness to Pay Analysis

For the willingness to pay (WTP) analysis, respondents were first presented with eight measures that could be implemented to solve the problem of Cuitzeo lake, previously selected in the pilot questionnaire. Respondents assessed from 1 to 5 the level of urgency for the implementation of management measures, which has an outstanding global average (4.76 out of 5).

Table 4.

Assessment of the level of urgency to implement management measures (1-5).

Table 4.

Assessment of the level of urgency to implement management measures (1-5).

| Management measures |

Value |

Rank |

| Expand the infrastructure of wastewater treatment plants |

4.86 |

4 |

| Create intermunicipal sanitary landfills |

4.42 |

7 |

| Composting of urban and rural wastes |

4.61 |

6 |

| Reforesting in key areas of the lake basin |

4.91 |

2 |

| Planting vegetation in key areas of the lake shore |

4.94 |

1 |

| Implement efficient and/or alternative water harvesting systems |

4.87 |

3 |

| Decrease the use of agrochemicals in the basin |

4.73 |

5 |

| Mean value |

4.76 |

|

By relative importance, respondents considered urgently the planting of vegetation in key areas of the lake shore (4.94) and reforestation in strategic areas of the watershed (4.91), followed by the implementation of efficient water catchment systems (4.87) and the expansion of wastewater treatment plant infrastructure (4.86).

Once respondents assessed the level of urgency of the management measures, they were asked about WTP for their implementation. The payment vehicle, selected in the pilot survey, was a surcharge on their household water bill. As in the WTA analysis, a comparison was made between the two samples, demonstrating through the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test that there are also no significant differences between 2018 and 2025, so the pooled sample was considered.

Half of the full sample (155 respondents) showed their willingness to pay for the implementation of management measures while the remaining 49.35 % (151 respondents) were not willing to pay. Furthermore, respondents who refused to pay were invited to provide justification for their decision. In the survey, 80.13 % of respondents who did not show a WTP stated that the reason was that “My income level would not allow me to contribute” and 78.15% stated that the government is responsible for providing funds to improve the lake. This last response was categorized as protest zeros. This finding suggests that 118 of the 151 respondents with a null WTP corresponded to protesting zeros, with the remaining 33 being real zeros. The hypothetical market is comprised of respondents with WTP>0 and real zeros and is therefore composed of 188 households.

The mean of the amount of WTP is 51.33

$MXN/household/month, with a maximum of 500

$MXN/household/month and a minimum of 0

$MXN/household/month (corresponding to real zeros) (

Table 5).

From the mean individual WTP, it is possible to estimate the aggregate total WTP for the region of the Cuitzeo lake (13,542 households), which would be the total economic value, a proxy of the social benefit derived from the implementation of management measures to solve the degradation of the lake. This gives a total economic value of 695,111 $MXN/household/month (around 8,341,330 $MXN/year).

As in the WTA analysis, a multivariate analysis of WTP was performed considering socioeconomic and environmental commitment variables (

Table A1), as well as the interaction between these variables.

Willingness to pay binary (WTPB) factors were identified with a

logit model (

Table 6), where WTPB takes a value of 1 if the respondent's response is WTP for the implementation of management measures (50.65 %) and 0 if it is a WTP=0 (49.35 %). The

logit model presents a good fit (87.8 % of Correct Classification - CPC) and show no collinearity problems (VIF < 10).

Three significant variables were found in the

logit model (

Table 6). Given their marginal effects, the probability of WTP for the implementation of management measures in the Cuitzeo lake increases by 72.1 % when the respondent is an active worker. Furthermore, each additional point of the verbal ecological index increases the probability of payment by 9.3%, which rises to 12.4% for each point of concern that respondents have towards the lake issue.

To model the amount of the willingness to pay (WTPT) a

tobit estimation censored at 0 was carried out (

Table 7).

Five explanatory variables are significant in this model. It is observed that being a woman reduces the amount of payment for management measures, while having a university education, being an active worker, having a higher family income and a higher affective commitment index increase the willingness to pay. Thus, given the marginal effects evaluated for the sample means, being a woman reduces WTPT by 18 $MXN/household/month, while the amount of payment increases by 158 $MXN/household/month if the respondent has university studies, by 79 $MXN/household/month if the respondent is an active worker, 5 $MXN/household/month for every 1,000 $MXN of family income, and by 37 $MXN/household/month for each additional affective ecological commitment index point. It should also be noted that the time variable (Year 2025) was not significant in either of the two estimations, demonstrating, as in the WTA analysis, the absence of significant differences between samples.

4. Discussion

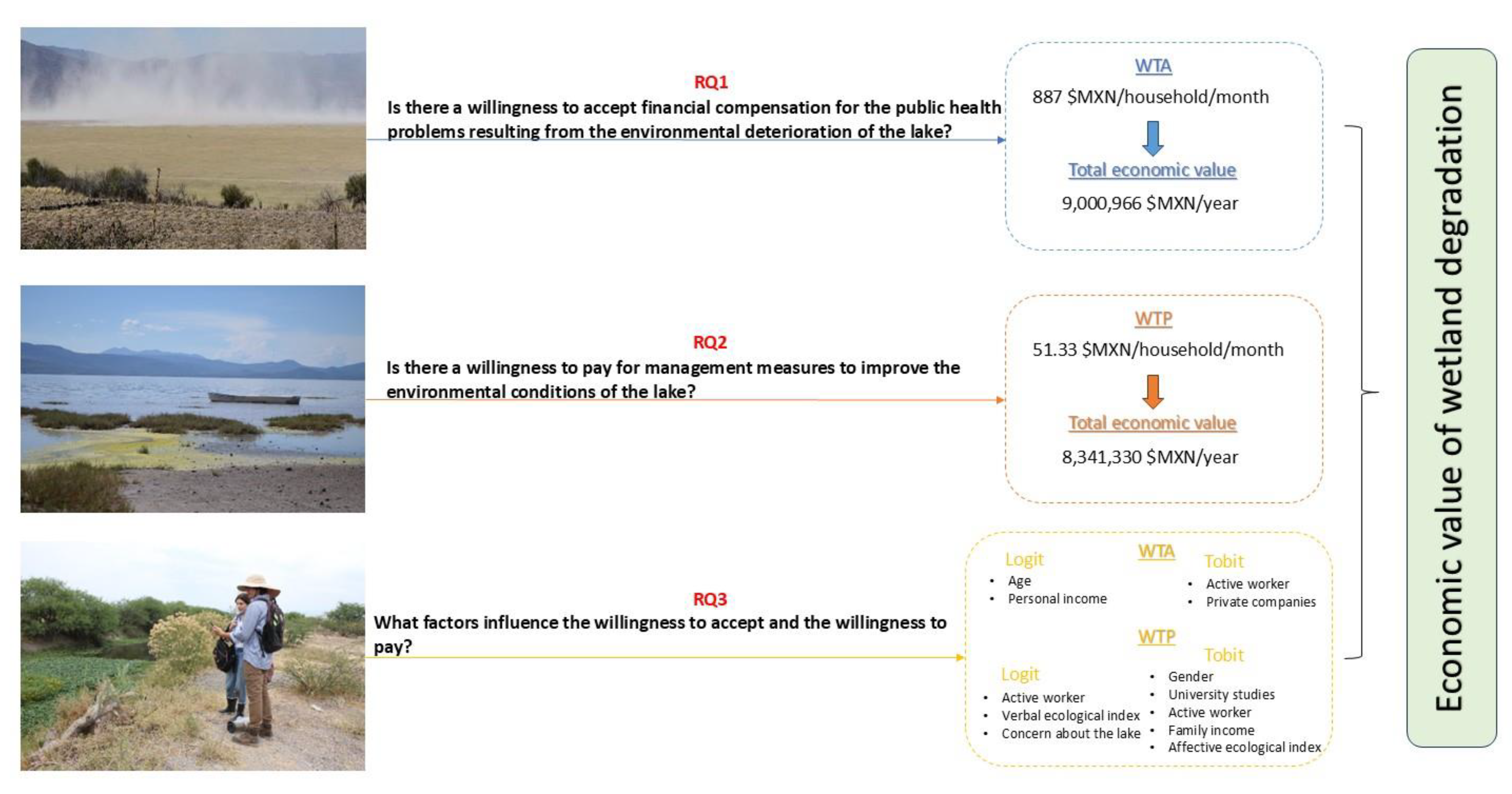

This work addresses the economic valuation of wetland degradation in Mexico, a country where little has been studied on the subject despite the importance of its lakes. To address the paucity of relevant studies in the existing literature, the case study of Cuitzeo lake was selected, given its status as one of the lakes exhibiting significant ecological degradation, with a consequential impact on the public health of the surrounding population. The application of a contingent valuation survey has enabled the successful resolution of the three research questions that had been formulated (

Figure 3):

(1) Is there a willingness to accept financial compensation for the public health problems resulting from the environmental deterioration of the lake?

The finding that approximately 90% of the surveyed population is willing to accept economic compensation, with an average WTA of 887 $MXN/household/month, serves to confirm the existing public health problem surrounding the populations of Cuitzeo lake. The health value of the “tolvanera” process is thus obtained (around 9 million $MXN), a figure unknown until now because the market fails in the face of this type of externalities.

This shows for the first time in the literature the economic cost of the direct negative effects of wetland degradation on human health in a Latin American country. These results are consistent with those observed in other wetlands across Europe [

34,

35] and Asia [

36,

37], where rising health expenditures underscore the necessity for implementing measures to foster sustainable development.

It is imperative that a public policy is formulated to allocate vouchers for medical expenses, encompassing the amount of the WTA, with the objective of reducing defensive health costs. The responsibility for overseeing this process should be entrusted to the policy makers of the region, with the aim of enhancing the well-being of the inhabitants of the lake area.

(2) Is there a willingness to pay for management measures to improve the environmental conditions of the lake?

This work showed the existence of a social demand for improving the environmental conditions of Cuitzeo lake where approximately 50% of the sample, with an average WTP of 51 $MXN/household/month, were willing to finance the implementation of a series of management measures.

The total economic value obtained from the WTP, which amounted to 8.3 million

$MXN/year, could be used to calculate the budget that would have to be spent annually for the implementation of the management measures assessed by the respondents. The high social valuation assigned to all management measures proposed to be implemented in the area suggests a relatively equal distribution of the budget among all measures, with a higher budget allocation towards reforestation and planting of riparian vegetation in key areas of the wetland. These economic values can be compared with those obtained in wetlands in Spain [

15], the United States [

38], Bangladesh [

39], and China [

40] where there is a clear social preference for measures to promote wetland support services such as revegetation of wetland environments.

The values obtained in this work should be used by policy makers as an indicator of the well-being that would be generated by the implementation of management measures in Cuitzeo lake. It could be suggested that tax collection through a fee on the water bill as a basis for the amount of the WTP incentivizes the implementation of actions to improve the conditions of the lake. Furthermore, as reflected in the survey, beyond the collection of taxes from the population, there must be greater involvement from the state, federal and municipal administrations. It is incumbent upon these policy makers to promote public investment in innovation and nature-based solutions [

41], with a view to supporting the most sustainable sectors and the most environmentally vulnerable regions. Furthermore, there is a necessity to concentrate on the identification of novel models of agricultural production that exhibit reduced water consumption and erosive capacity [

42]. This should be accompanied by a diminution in the exploitation of aquifers, the planning of urban development outside of flood plains, and the respect of the biodiversity associated with the wetland.

(3) What factors influence the willingness to accept and the willingness to pay?

The findings of the multivariate analyses demonstrated, firstly, that there was no significant influence between the two samples employed in this work, as the time variable used was not significant. Secondly, they demonstrated that it was the socio-economic and environmental perception characteristics that determined WTA and WTP. In this sense, significant evidence was found that older people, those who are economically inactive and have a lower personal income, are those who show a higher WTA. Conversely, being a man, an active worker, having a university education and a higher ecological commitment (affective and verbal) show a higher WTP. These results are consistent with those reported in the extant literature on the economic valuation of environmental assets [

15,

19,

20,

21] based on the influence of these socio-economic and environmental factors in the valuation exercise.

Thus, it is imperative that the knowledge produced is disseminated through appropriate channels, such as forums and workshops. These initiatives are instrumental in promoting awareness and education in environmental terms. By doing so, the population of the area can be encouraged to align their daily actions with the principles of environmental sustainability. Furthermore, it is essential to cultivate behaviors that are conducive to enhancing the condition of the lake. In this manner, the efficient allocation of monetary resources for environmental improvements is imperative, a matter of even greater urgency in the present context of global change, which casts doubt on the spatio-temporal availability of water resources.

The economic valuation method employed in this work provides a foundation for determining the allocation of economic resources in the pursuit of public policies aimed at addressing the environmental challenges posed by Cuitzeo lake. Consequently, valuation methods should be utilized in conjunction with the results obtained, employing cost-benefit analyses to assess the socio-economic profitability of implementing environmental restoration initiatives. This would enable the authorities responsible for overseeing public health, environmental issues in water bodies, and the wider environment to guide the analysis for decision-making.

5. Conclusions

The present work has demonstrated the economic value associated with the degradation of a wetland in Mexico, using Cuitzeo lake in the state of Michoacan as a representative case study. A significant proportion of the population is willing to accept economic compensation for damage to public health, and they are also willing to pay for the implementation of management measures to improve the environmental status of the wetland. The findings of this work have practical implications that may be of use to governmental institutions charged with the management of the water resources of Cuitzeo lake, given the direct impact of wetland degradation on public health and on the socio-economic and environmental development of the area. It can thus be concluded that the transition towards sustainable wetland management requires the involvement of public participatory processes, including surveys such as those carried out in this work, to support and encourage the implementation of regional policies with the aim of reducing the negative effects on the well-being of the population. Consequently, economic valuation analyses constitute a pivotal component in the formulation of public policies.

The implications of this work extend beyond those typically addressed in economic valuation studies, emphasizing not only the economic value associated with environmental enhancement of the wetland, but also that derived from the damage caused to public health. In summary, the general public has a vested interest in finding a solution to this problem, which provides the foundation for the development of more socially acceptable and efficient policies in countries that have received little study, such as those in Latin America.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, RTR, JAAG, ACT, CFOP and JMMP; methodology, RTR and JMMP; software, RTR, JAAG and JMMP; validation, RTR, JAAG, ACT, CFOP and JMMP; formal analysis, RTR, JAAG, ACT, CFOP and JMMP; investigation, RTR, JAAG, CFOP and JMMP; resources, RTR, JAAG, CFOP and JMMP; data curation, RTR and JAAG; writing—original draft preparation, RTR and JAAG; writing—review and editing, RTR, JAAG and JMMP; visualization, RTR, JAAG, ACT, CFOP and JMMP; supervision, CFOP and JMMP.; project administration, RTR.; funding acquisition, RTR, CFOP and JMMP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding through a doctoral scholarship by the National Council of Humanities, Science, Technology and Innovation (CONAHCYT), now known as the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology and Innovation (SECIHTI) of the Government of Mexico.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the interviewees from the municipalities of Cuitzeo (Jeruco and Miguel Silva) and Huandacareo (Capacho), Michoacan. Without their valuable contributions this work would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest”.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Contingent valuation sample description (n = 306)

Table A1.

Contingent valuation sample description (n = 306)

| Description |

Mean |

SD |

Min |

Max |

| Household size (people) |

4.01 |

1.62 |

1 |

13 |

| Age (years) |

50.13 |

12.70 |

27 |

85 |

| Family income ($MXN/household/month) |

2,948 |

2,278 |

1,000 |

25,000 |

| Personal income ($MXN /person/month) |

2,366 |

2,302 |

1,000 |

25,000 |

| Active worker (% yes) |

93.79 |

|

|

|

| University studies (%) |

6.21 |

|

|

|

| Gender (% women) |

21.57 |

|

|

|

| Concern about the lake (1-5) |

3.94 |

0.32 |

3 |

5 |

| Federal government (1-5) |

4.95 |

0.24 |

3 |

5 |

| State government (1-5) |

4.82 |

0.40 |

3 |

5 |

| Municipal government (1-5) |

4.69 |

0.61 |

3 |

5 |

| Private companies (1-5) |

4.71 |

0.62 |

2 |

5 |

| NGOs (1-5) |

4.83 |

0.44 |

3 |

5 |

| Citizens (1-5) |

4.94 |

0.27 |

3 |

5 |

| Affective ecological index (1-5) |

4.89 |

0.27 |

3.5 |

5 |

| Verbal ecological index (1-5) |

3.89 |

0.78 |

1 |

5 |

| Real ecological index (1-5) |

1.34 |

0.67 |

1 |

5 |

References

- Kundu, S.; Kundu, B.; Rana, N. K.; Mahato, S. Wetland degradation and its impacts on livelihoods and sustainable development goals: An overview. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2024, 48, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Cui, B.; Cao, H.; Li, A.; Zhang, B. Wetland degradation and ecological restoration. The Scientific World Journal 2013, 523632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, S.; Su, F. Coastal wetland degradation and ecosystem service value change in the Yellow River Delta, China. Global Ecology and Conservation 2023, 44, e02501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballut-Dajud, G. A.; Sandoval Herazo, L. C.; Fernández-Lambert, G.; Marín-Muñiz, J. L.; López Méndez, M. C.; Betanzo-Torres, E. A. Factors affecting wetland loss: A review. Land 2022, 11(3), 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, P. E. R.; Connelly, R. Wetlands and human health: an overview. Wetlands ecology and management 2012, 20, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltby, E. The wetlands paradigm shift in response to changing societal priorities: A reflective review. Land 2022, 11(9), 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, K.; Zabbey, N. Contaminated land and wetland remediation in Nigeria: opportunities for sustainable livelihood creation. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 639, 1560–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebresllassie, H.; Gashaw, T.; Mehari, A. Wetland degradation in Ethiopia: causes, consequences and remedies. Journal of environment and earth science 2014, 4(11), 40–48. [Google Scholar]

- Adhya, T.; Banerjee, S. Impact of wetland development and degradation on the livelihoods of wetland-dependent communities: a case study from the lower gangetic floodplains. Wetlands 2022, 42(7), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A. P.; Jupiter, S. Natural disasters, health and wetlands: a Pacific small island developing state perspective. Wetlands and human health 2015, 169–191. [Google Scholar]

- García-Herrero, L.; Lavrnić, S.; Guerrieri, V.; Toscano, A.; Milani, M.; Cirelli, G. L.; Vittuari, M. Cost-benefit of green infrastructures for water management: A sustainability assessment of full-scale constructed wetlands in Northern and Southern Italy. Ecological Engineering 2022, 185, 106797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Hou, Y.; Xue, Y. Water resources carrying capacity of wetlands in Beijing: Analysis of policy optimization for urban wetland water resources management. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 161, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N. K.; Gourevitch, J. D.; Wemple, B. C.; Watson, K. B.; Rizzo, D. M.; Polasky, S.; Ricketts, T. H. Optimizing wetland restoration to improve water quality at a regional scale. Environmental Research Letters 2019, 14(6), 064006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musasa, T.; Muringaniza, K. C.; Manyati, M. The role of stakeholder participation in wetland conservation in urban areas: A case of Monavale Vlei, Harare. Scientific African 2023, 19, e01574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perni, Á.; Martínez-Paz, J. M. Measuring conflicts in the management of anthropized ecosystems: Evidence from a choice experiment in a human-created Mediterranean wetland. Journal of Environmental Management 2017, 203, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marre, J. B.; Thebaud, O.; Pascoe, S.; Jennings, S.; Boncoeur, J.; Coglan, L. Is economic valuation of ecosystem services useful to decision-makers? Lessons learned from Australian coastal and marine management. Journal of Environmental Management 2016, 178, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.; Fraser, G.; Snowball, J. Economic evaluation of wetland restoration: a systematic review of the literature. Restoration Ecology 2018, 26(6), 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaladejo-García, J. A.; Alcon, F.; Martínez-Carrasco, F.; Martínez-Paz, J. M. Understanding socio-spatial perceptions and Badlands ecosystem services valuation. Is there any welfare in soil erosion? Land Use Policy 2023, 128, 106607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaladejo-García, J. A.; Zabala, J. Á.; Navarro, N.; Alcon, F.; Martínez-Paz, J. M. Preferencias sociales y valoración económica en la gestión sostenible de espacios naturales protegidos: el río Segura y su entorno en Cieza (Región de Murcia). Cuadernos Geográficos 2021, 60, 212–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Paz, J. M.; Albaladejo-García, J. A.; Barreiro-Hurle, J.; Pleite, F. M. C.; Perni, Á. Spatial effects in the socioeconomic valuation of peri-urban ecosystems restoration. Land Use Policy 2021, 105, 105426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaladejo-García, J. A.; Martínez-Paz, J. M. Substitution effects and spatial factors in the social demand for landscape aesthetics in agroecosystems. Landscape and Urban Planning 2025, 257, 105322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer, J. & Escobar, E. Limnological regionalization of Mexico. Lakes & Reservoirs: Research & Management 1996, 2: 55-69.

- Setlhogile, T.; Arntzen, J.; Mabiza, C.; Mano, R. Economic valuation of selected direct and indirect use values of the Makgadikgadi wetland system, Botswana. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 2011, 36(14-15), 1071-1077.

- Díaz-Pinzón, L.; Sierra, L.; Trillas, F. The Economic value of wetlands in urban areas: the benefits in a developing country. Sustainability 2022, 14(14), 8302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechasa, F.; Senbeta, F.; Guta, D. D. Economic value of wetlands services in the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia. Environmental Economics and Policy Studies 2021, 23(1), 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamboleo, M.; Adem, A. Estimating willingness to pay for the conservation of wetland ecosystems, Lake Victoria as a case study. Knowledge & Management of Aquatic Ecosystems 2022, (423), 2.

- Dang, K. B.; Phan, T. T. H.; Nguyen, T. T.; Pham, T. P. N.; Nguyen, M. H.; Dang, V. B.; ... & Ngo, V. L. Economic valuation of wetland ecosystem services in northeastern part of Vietnam. Knowledge & Management of Aquatic Ecosystems 2022, (423), 12.

- Regalado, R. T.; Paniagua, C. F. O. Percepción social de medidas de gestión sostenible en el lago de Cuitzeo, México. Papeles de Geografía 2024, (70), 106-122.

- Regalado, R. T.; Paniagua, C. F. O. Preferencias socioeconómicas por costos ambientales en la Región Oeste del Lago de Cuitzeo, Michoacán, México. Campos Neutrais-Revista Latino-Americana de Relações Internacionais 2019, 1(2), 8-25.

- Chacón, A.; Rosas, C.; Trueba, R. ; Sauno. F. y Jacobo, A. (2022). Lake Cuitzeo, Michoacan, Mexico. Effects of environmental deteroration. In 18th World Lake Conference/ Muñoz, S. (Academic Editor). Guanajuato: Universidad de Guanajuato; Mexico City.

- Secretaria de Salud de Michoacán (2025). Jurisdicción Sanitaria N°1 Morelia. Carpeta Básica. Coordinación y evaluación y Estadística. Available in: https://salud.michoacan.gob.

- Zabala, J. A.; Albaladejo-García, J. A.; Navarro, N.; Martínez-Paz, J. M.; Alcon, F. Integration of preference heterogeneity into sustainable nature conservation: From practice to policy. Journal for Nature Conservation 2022, 65, 126095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (2020). Censo de Población y Vivienda. Available in: https://inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/.

- Busse, M.; Heitepriem, N.; Siebert, R. The acceptability of land pools for the sustainable revalorisation of wetland meadows in the Spreewald Region, Germany. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzén, F.; Dinnétz, P.; Hammer, M. Factors affecting farmers' willingness to participate in eutrophication mitigation—A case study of preferences for wetland creation in Sweden. Ecological Economics 2016, 130, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Khachatryan, H.; Zhu, H. Poyang lake wetlands restoration in China: An analysis of farmers’ perceptions and willingness to participate. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 284, 125001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Kong, F. The analysis of farmers’ willingness to accept and its influencing factors for ecological compensation of Poyang Lake wetland. Procedia Engineering 2017, 174, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, W. A.; Murray, B. C.; Kramer, R. A.; Faulkner, S. P. Valuing ecosystem services from wetlands restoration in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. Ecological Economics 2010, 69(5), 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohel, M. S. I.; Islam, H. N.; Ullah, M. A.; Newaz, K. M. N.; Khan, M. F. A.; Sarker, G. C.; Bhuiyan, M. S. R. Ecological and economic significance of swamp vegetation nursery for successful reforestation program: an insight from Bangladesh. Geology, Ecology, and Landscapes, 2024; 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, Y.; Peng, S.; Liu, G.; Ducharne, A.; Ciais, P.; Prigent, C. . & Tang, X. Trade-off between tree planting and wetland conservation in China. Nature communications 2022, 13(1), 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, C. S.; Kašanin-Grubin, M.; Solomun, M. K.; Sushkova, S.; Minkina, T.; Zhao, W.; Kalantari, Z. Wetlands as nature-based solutions for water management in different environments. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 2023, 33, 100476. [Google Scholar]

- Albaladejo-García, J. A.; Martínez-García, V.; Martínez-Paz, J. M.; Alcon, F. Gaining insight into best management practices for climate change impact abatement on agroecosystem services and disservices. Journal of Environmental Management 2025, 384, 125629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).