Submitted:

27 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background of the Study

3. Methodology

Study Design and Setting

Study Population and Sample Size

Sampling Procedure

- Stratification: All 28 UPHCs were included to ensure representativeness of the city’s geographic zones.

- Allocation: The 210 participants were proportionately allocated to each UPHC based on the number of antenatal registrations in the preceding month.

- Participant Selection: From each UPHC, pregnant women were selected randomly from the ANC register using a simple random sampling method (lottery method or random number table), until the assigned number of participants for that center was reached.

- ➢

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Pregnant women of any gestational age

- Registered for ANC at one of the 28 UPHCs

- Resident of Meerut City for ≥ 6 months

- Provided written informed consent

- Known chronic diseases unrelated to anemia (e.g., renal failure, malignancy)

- Blood transfusion within the last month

- Inability to participate due to severe illness or communication barriers

Data Collection

- Demographic details: age, marital status, parity, education, occupation, religion.

- Socioeconomic status: family income, housing conditions, and asset ownership.

- Obstetric history: gestational age, previous pregnancies, birth intervals, miscarriage history.

- Nutritional habits: daily meal patterns, food group intake, iron-rich food consumption, and supplement usage.

- Health services utilization: number of antenatal visits, iron-folic acid tablet distribution and consumption.

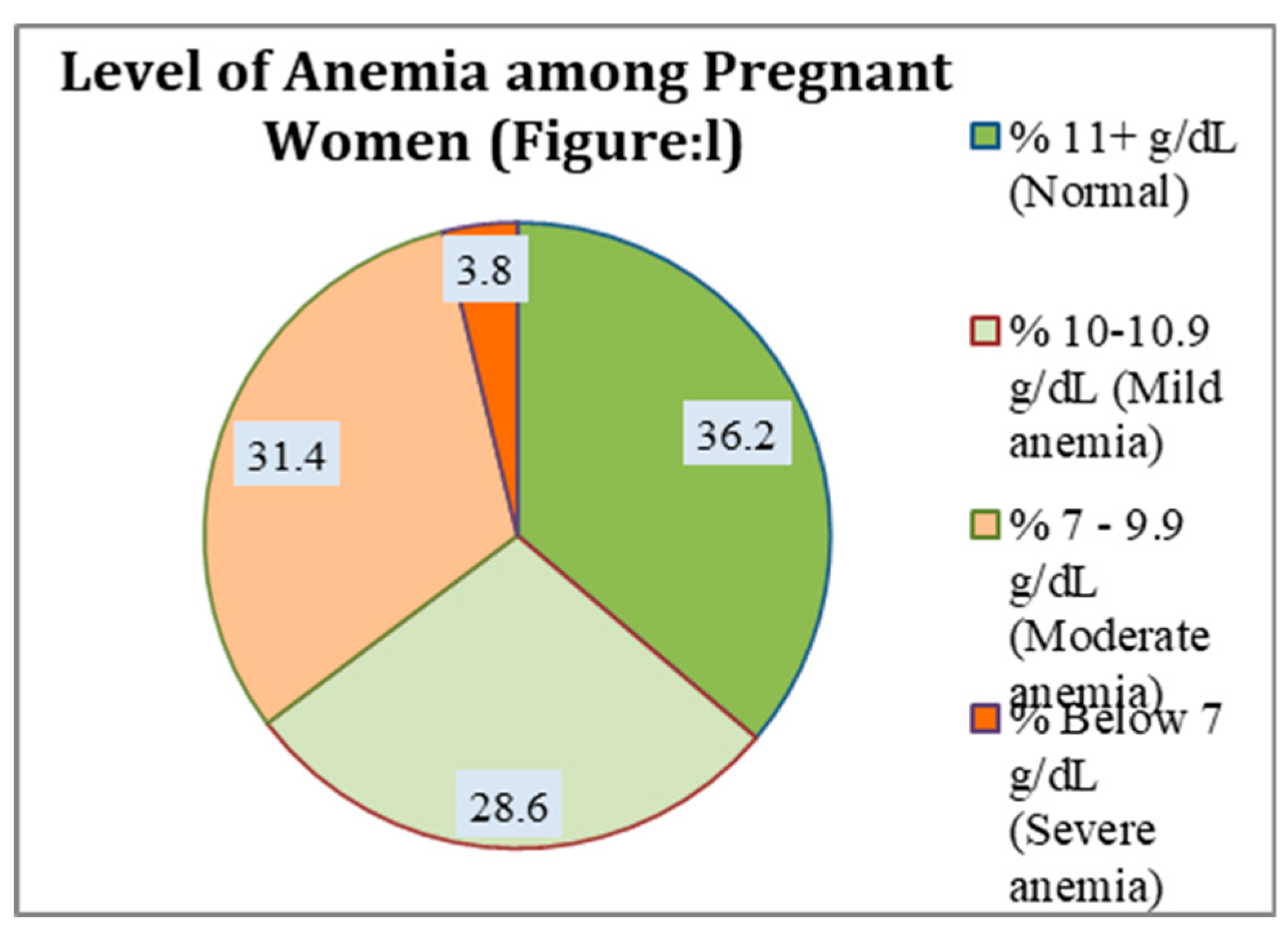

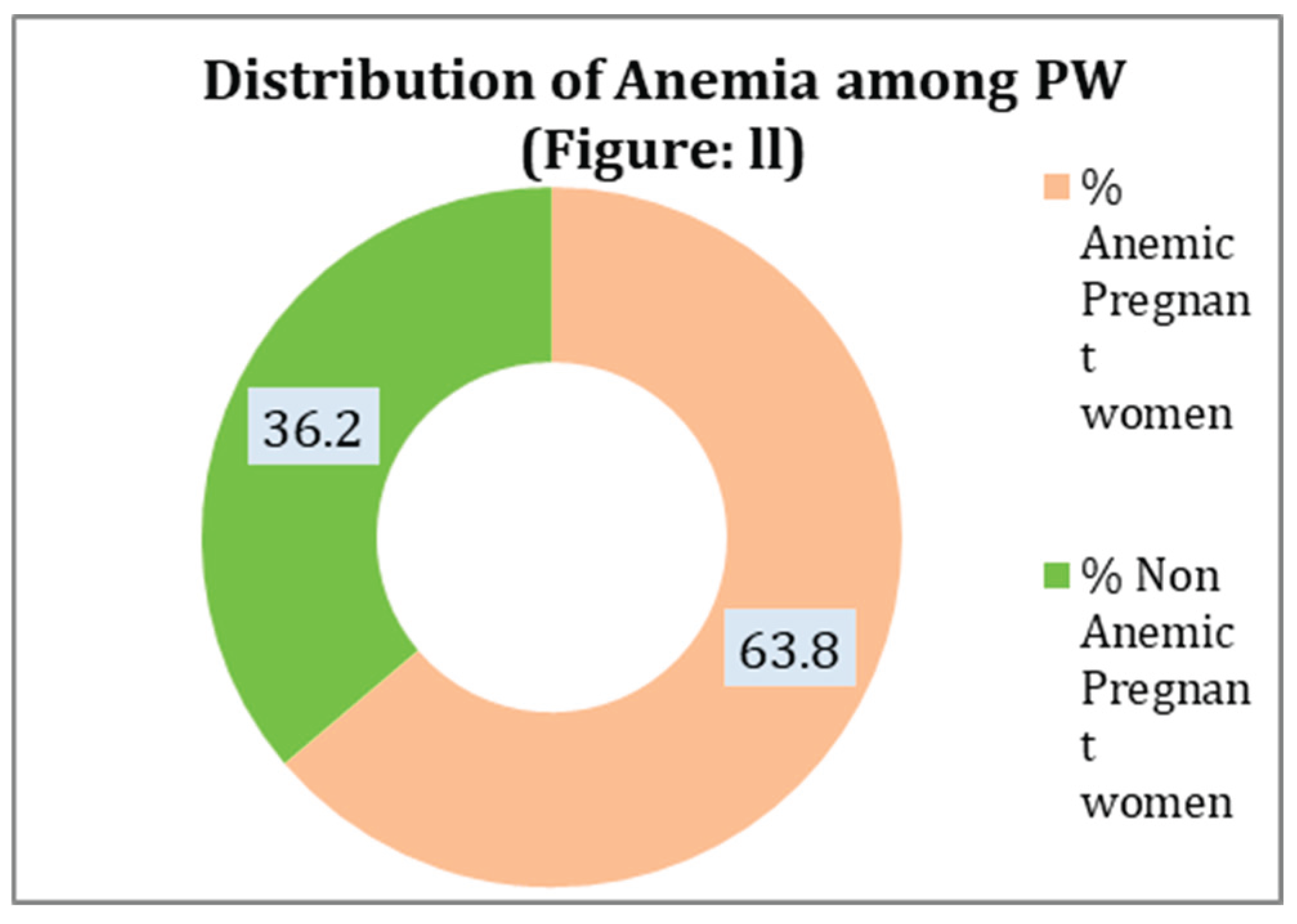

- Hemoglobin values were extracted from each woman’s ANC record, reflecting in routine visits register hemoglobin meter testing recently conducted at the UPHC. Anemia was classified as per WHO criteria:

- Mild: 10.0–10.9 g/dL

- Moderate: 7.0–9.9 g/dL

- Severe: < 7.0 g/dL

Ethical Considerations

Statistical Analysis

- Descriptive statistics: Means (± SD) for continuous variables; frequencies (%) for categorical variables.

- Bivariate analysis: Chi-square tests assessed associations between anemia status and categorical factors (socioeconomic and dietary variables).

- Multivariable logistic regression: Variables significant at p < 0.10 in bivariate analysis were entered into the model to identify independent predictors of anemia, adjusting for age, parity, and gestational age. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.Statistical significance: Set at p < 0.05 for all tests.

4. Results

| The socio-demographic characteristics of expectant mothers (n = 210) | |||

| Variables | Anemic PW - 134 ( %) | Non Anemic PW - 76 (%) | Total - 210(%) |

| Women's age group who are pregnant | |||

| ≤ 20 | 9 (6.7) | 3 (3.9) | 12 (5.7) |

| Age 21-25 | 46 (34.3) | 31 (40.8) | 77 (36.7) |

| Age 26 -30 | 56 (41.8) | 33 (43.4) | 89 (42.4) |

| Age 31 -35 | 19 (14.2) | 7 (9.2) | 26 (12.4) |

| Age >35 | 4 (3.0) | 2 (2.6) | 6 (2.9) |

| Monthly household income | |||

| Low | 84 (62.7) | 10 (13.2) | 94 (44.8) |

| Medium | 39 (29.1) | 38 (50.0) | 77 (36.7) |

| High | 11 (8.2) | 28 (36.8) | 39 (18.6) |

| Pregnant women's educational attainment | |||

| No formal Education | 23 (17.2) | 7 (9.2) | 30 (14.3) |

| Primary & Middle (1-8) | 67 (50.0) | 28 (36.8) | 95 (45.2) |

| Secondary & Higher Secondary (9-12) | 37 (27.6) | 26 (34.2) | 63 (30.0) |

| UG & PG | 7 (5.2) | 15 (19.7) | 22 (10.5) |

| Religion of Pregnant women | |||

| Hindu & Other | 68 (50.7) | 45 (59.2) | 113 (53.8) |

| Muslim | 66 (49.3) | 31 (40.8) | 97 (46.2) |

| Category of Religion | |||

| General | 60 (44.8) | 33 (43.4) | 93 (44.3) |

| OBC | 53 (39.6) | 34 (44.7) | 87 (41.4) |

| SC | 21 (15.7) | 9 (11.8) | 30 (14.3) |

| Basic Amenities Are Available (Electricity, clean drinking water, sanitary amenities, television, air conditioning, laptop or computer, and automobile transportation) | |||

| Low | 40 (29.9) | 19 (25.0) | 59 (28.1) |

| Medium | 76 (56.7) | 20 (26.3) | 96 (45.7) |

| Normal | 18 (13.4) | 37 (48.7) | 55 (26.2) |

| Entertainment Activities (Watch TV, Go to the Movies, and Read the News) | |||

| Low | 73 (54.5) | 11 (14.5) | 84 (40.0) |

| Moderate | 34 (25.4) | 21 (27.6) | 55 (26.2) |

| High | 27 (20.1) | 44 (57.9) | 71 (33.8) |

| Size of the family | |||

| 3-5 | 16 (11.9) | 17 (22.4) | 33 (15.7) |

| More than 5 | 118 (88.1) | 59 (77.6) | 177 (84.3) |

| Obstetrics features of ANC participants at UPHC Meerut City town, March–June 2025 (N=210) | |||

| Variables | Anemic PW - 134 ( %) | Non Anemic PW - 76 (%) | Total - 210(%) |

| Gestational Age of Pregnant women | |||

| First Trimester | 3 (2.2) | 5 (6.6) | 8 (3.8) |

| Second trimester (13-26 weeks) | 36 (26.9) | 33 (43.4) | 69 (32.9) |

| Third trimester (27+ weeks) | 95 (70.9) | 38 (50.0) | 133 (63.3) |

| For this pregnancy, begin your first ANC visit | |||

| Before 12 weeks | 5 (3.7) | 7 (9.2) | 12 (5.7) |

| 12–20 weeks | 129 (96.3) | 68 (89.5) | 197 (93.8) |

| 21–28 weeks | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.5) |

| Women in Pregnancy Gravida | |||

| 1 | 25 (18.7) | 19 (25.0) | 44 (21.0) |

| 2 | 54 (40.3) | 34 (44.7) | 88 (41.9) |

| 3 | 42 (31.3) | 16 (21.1) | 58 (27.6) |

| 4 | 13 (9.7) | 7 (9.2) | 20 (9.5) |

| The parity of pregnant women | |||

| 0 | 45 (33.6) | 27 (35.5) | 72 (34.3) |

| 1 | 53 (39.6) | 33 (43.4) | 86 (41.0) |

| 2 | 27 (20.1) | 12 (15.8) | 39 (18.6) |

| 3 | 9 (6.7) | 4 (5.3) | 13 (6.2) |

| Birth Gap from the previous to the present | |||

| Primigravida | 31 (23.1) | 27 (35.5) | 58 (27.6) |

| <2 | 72 (53.7) | 28 (36.8) | 100 (47.6) |

| >2 | 31 (23.1) | 21 (27.6) | 52 (24.8) |

| Live Children in the Present | |||

| 0 | 30 (22.4) | 28 (36.8) | 58 (27.6) |

| 1 | 60 (44.8) | 30 (39.5) | 90 (42.9) |

| 2 | 37 (27.6) | 15 (19.7) | 52 (24.8) |

| 3 | 7 (5.2) | 3 (3.9) | 10 (4.8) |

| Dietary Habit ,Anemia and its awareness | |||

| Variables | Anemic PW - 134 ( %) | Non Anemic PW - 76 (%) | Total - 210(%) |

| Daily diet include :- Fruits, Vegetables, Dairy products, Protein (meat, fish, eggs),Junk Food (Noodles, bread, pasta) | |||

| Low | 87 (64.9) | 10 (13.2) | 97 (46.2) |

| Medium | 41 (30.6) | 37 (48.7) | 78 (37.1) |

| Normal | 6 (4.5) | 29 (38.2) | 35 (16.7) |

| Do you face financial constraints in purchasing nutritious food? | |||

| Yes | 104 (77.6) | 43 (56.6) | 147 (70.0) |

| No | 30 (22.4) | 33 (43.4) | 63 (30.0) |

| Consume foods high in iron, such as meat, beans, and green leafy vegetables | |||

| Daily | 5 (3.7) | 9 (11.8) | 14 (6.7) |

| 2-3 times/week | 9 (6.7) | 12 (15.8) | 21 (10.0) |

| Rarely | 120 (89.6) | 55 (72.4) | 175 (83.3) |

| Do you know how important it is to eat a balanced diet when pregnant? | |||

| Yes | 116 (86.6) | 69 (90.8) | 185 (88.1) |

| No | 18 (13.4) | 7 (9.2) | 25 (11.9) |

| How is your Iron/FA intake? | |||

| Daily | 36 (26.9) | 19 (25.0) | 55 (26.2) |

| Once in a week | 16 (11.9) | 13 (17.1) | 29 (13.8) |

| Sometime | 82 (61.2) | 44 (57.9) | 126 (60.0) |

| Do you follow a special diet during pregnancy | |||

| Yes | 19 (14.2) | 60 (78.9) | 79 (37.6) |

| No | 115 (85.8) | 16 (21.1) | 131 (62.4) |

| Knowledge of Anemia and Its Sources | |||

| High | 29 (21.6) | 35 (46.1) | 64 (30.5) |

| Moderate | 58 (43.3) | 18 (23.7) | 76 (36.2) |

| Low | 47 (35.1) | 23 (30.3) | 70 (33.3) |

| Factors associated with Prevalence of Anemia among pregnant women | |||||

| Variables | Anemic PW - 134 (%) | Non Anemic PW - 76 (%) | Total - 210(%) | Chi Square P-Value | Logistic Regression p-value |

| Household monthly Income | |||||

| Low | 84 (62.7) | 10 (13.2) | 94 (44.8) | 0.000* | 0.003** |

| Medium | 39 (29.1) | 38 (50.0) | 77 (36.7) | ||

| High | 11 (8.2) | 28 (36.8) | 39 (18.6) | ||

| Daily diet include :- Fruits, Vegetables, Dairy products, Protein (meat, fish, eggs),Junk Food (Noodles, bread, pasta) | |||||

| Low | 87 (64.9) | 10 (13.2) | 97 (46.2) | 0.000* | <0.001** |

| Medium | 41 (30.6) | 37 (48.7) | 78 (37.1) | ||

| Normal | 6 (4.5) | 29 (38.2) | 35 (16.7) | ||

| Knowledge of Anemia and Its Sources | |||||

| High | 29 (21.6) | 35 (46.1) | 64 (30.5) | 0.000* | 0.187*** |

| Moderate | 58 (43.3) | 18 (23.7) | 76 (36.2) | ||

| Low | 47 (35.1) | 23 (30.3) | 70 (33.3) | ||

| Pregnant women's educational attainment | |||||

| No formal Education | 23 (17.2) | 7 (9.2) | 30 (14.3) | 0.002* | 0.116*** |

| Primary & Middle (1-8) | 67 (50.0) | 28 (36.8) | 95 (45.2) | ||

| Secondary & Higher Secondary (9-12) | 37 (27.6) | 26 (34.2) | 63 (30.0) | ||

| UG & PG | 7 (5.2) | 15 (19.7) | 22 (10.5) | ||

- ➢

- Interpretation of Key Findings:

Summary and Conclusion

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

Conflict of interest

Source of funding

Data availability statement

Transparency statement

References

- Abriha, A., Yesuf, M.E. & Wassie, M.M. Prevalence and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women of Mekelle town: a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes 7, 888 (2014).

- Tibambuya BA, Ganle JK, Ibrahim M. Anaemia at antenatal care initiation and associated factors among pregnant women in West Gonja District, Ghana: a cross-sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2019 Aug 27;33:325. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Anlaakuu P, Anto F. Anaemia in pregnancy and associated factors: a cross sectional study of antenatal attendants at the Sunyani Municipal Hospital, Ghana. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Aug 11;10(1):402.

- Adjei-Gyamfi S, Asirifi A, Peprah W, Abbey DA, Hamenoo KW, Zakaria MS, Mohammed O, Aryee PA. Anaemia at 36 weeks of pregnancy: Prevalence and determinants among antenatal women attending peri-urban facilities in a developing country, Ghana. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2024 Sep 5;4(9):e0003631. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumari S, Garg N, Kumar A, Guru PKI, Ansari S, Anwar S, Singh KP, Kumari P, Mishra PK, Gupta BK, Nehar S, Sharma AK, Raziuddin M, Sohail M. Maternal and severe anaemia in delivering women is associated with risk of preterm and low birth weight: A cross sectional study from Jharkhand, India. One Health. 2019 Aug 19;8:100098. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baig-Ansari N, Badruddin SH, Karmaliani R, Harris H, Jehan I, Pasha O, Moss N, McClure EM, Goldenberg RL. Anemia prevalence and risk factors in pregnant women in an urban area of Pakistan. Food Nutr Bull. 2008 Jun;29(2):132-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sappani M, Mani T, Asirvatham ES, Joy M, Babu M, Jeyaseelan L. Trends in prevalence and determinants of severe and moderate anaemia among women of reproductive age during the last 15 years in India. PLoS One. 2023 Jun 1;18(6):e0286464. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perumal V. Reproductive risk factors assessment for anaemia among pregnant women in India using a multinomial logistic regression model. Trop Med Int Health. 2014 Jul;19(7):841-51. Epub 2014 Apr 7. 2014. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirore LL, Mulugeta A, Belachew AB, Gebrehaweria M, Sahilemichael A, Erkalo D, Atsbha R. Factors associated with anaemia among women of reproductive age in Ethiopia: Multilevel ordinal logistic regression analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2021 Jan;17(1):e13063. Epub 2020 Aug 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ara G, Hassan R, Haque MA, Boitchi AB, Ali SD, Kabir KS, Mahmud RI, Islam KA, Rahman H, Islam Z. Anaemia among adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women in the southern rural region of Bangladesh: Prevalence and risk factors. PLoS One. 2024 Jul 10;19(7):e0306183. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grover K, Kumar T, Doda A, Bhutani R, Yadav S, Kaushal P, Kapoor R, Sharma S. Prevalence of anaemia and its association with dietary habits among pregnant women in the urban area of Haryana. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020 Feb 28;9(2):783-787. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diamond-Smith NG, Gupta M, Kaur M, Kumar R. Determinants of Persistent Anemia in Poor, Urban Pregnant Women of Chandigarh City, North India: A Mixed Method Approach. Food Nutr Bull. 2016 Jun;37(2):132-43. Epub 2016 Mar 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mithra P, Unnikrishnan B, Rekha T, Nithin K, Mohan K, Kulkarni V, Kulkarni V, Agarwal D. Compliance with iron-folic acid (IFA) therapy among pregnant women in an urban area of south India. Afr Health Sci. 2013 Dec;13(4):880-5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perumal V. Reproductive risk factors assessment for anaemia among pregnant women in India using a multinomial logistic regression model. Trop Med Int Health. 2014 Jul;19(7):841-51. Epub 2014 Apr 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapil U, Pathak P, Tandon M, Singh C, Pradhan R, Dwivedi SN. Micronutrient deficiency disorders amongst pregnant women in three urban slum communities of Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 1999 Oct;36(10):983-9. [PubMed]

- Pathak P, Tandon M, Kapil U, Singh C. Prevalence of iron deficiency anemia amongst pregnant women in urban slum communities of Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 1999 Mar;36(3):322-3. [PubMed]

- Chotnopparatpattara P, Limpongsanurak S, Charnngam P. The prevalence and risk factors of anemia in pregnant women. J Med Assoc Thai. 2003 Nov;86(11):1001-7. [PubMed]

- Alper BS, Kimber R, Reddy AK. Using ferritin levels to determine iron-deficiency anemia in pregnancy. J Fam Pract. 2000 Sep;49(9):829-32. [PubMed]

- 19. Gayathri S, Manikandanesan S, Venkatachalam J, Gokul S, Yashodha A, Premarajan KC. Coverage of and compliance to iron supplementation under the National Iron Plus Initiative among reproductive age-group women in urban Puducherry - a cross-sectional study. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2019 Apr 11;33(2). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel TM, Thomas T, Finkelstein J, Bosch R, Rajendran R, Virtanen SM, Srinivasan K, Kurpad AV, Duggan C. Correlates of anaemia in pregnant urban South Indian women: a possible role of dietary intake of nutrients that inhibit iron absorption. Public Health Nutr. 2013 Feb;16(2):316-24. Epub 2012 May 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vindhya J, Nath A, Murthy GVS, Metgud C, Sheeba B, Shubhashree V, Srinivas P. Prevalence and risk factors of anemia among pregnant women attending a public-sector hospital in Bangalore, South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019 Jan;8(1):37-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pathak P, Tandon M, Kapil U, Singh C. Prevalence of iron deficiency anemia amongst pregnant women in urban slum communities of Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 1999 Mar;36(3):322-3. [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti S, George N, Majumder M, Raykar N, Scott S. Identifying sociodemographic, programmatic and dietary drivers of anaemia reduction in pregnant Indian women over 10 years. Public Health Nutr. 2018 Sep;21(13):2424-2433. Epub 2018 Apr 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kaur M, Chauhan A, Manzar MD, Rajput MM. Maternal Anaemia and Neonatal Outcome: A Prospective Study on Urban Pregnant Women. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015 Dec;9(12):QC04-8. Epub 2015 Dec 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thasneem NB, Kaimal RS, Thengu Murichathil AH. Study of sociodemographic factors and perceptions of women in the reproductive age group with anaemia - A hospital-based cross-sectional study in South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2025 Apr;14(4):1338-1345. Epub 2025 Apr 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perumal V. Reproductive risk factors assessment for anaemia among pregnant women in India using a multinomial logistic regression model. Trop Med Int Health. 2014 Jul;19(7):841-51. Epub 2014 Apr 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosal J, Bal M, Ranjit M, Das A, Behera MR, Satpathy SK, Dutta A, Pati S. To what extent classic socio-economic determinants explain trends of anaemia in tribal and non-tribal women of reproductive age in India? Findings from four National Family Heath Surveys (1998-2021). BMC Public Health. 2023 May 11;23(1):856. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dutta PK, Urmil AC, Gund SS, Dutta M. Utilisation of health services by "high risk" pregnant women in a semi urban community of Pune -- an analytical study. Indian J Matern Child Health. 1990 Jan-Mar;1(1):15-9. [PubMed]

- Thasneem NB, Kaimal RS, Thengu Murichathil AH. Study of sociodemographic factors and perceptions of women in the reproductive age group with anaemia - A hospital-based cross-sectional study in South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2025 Apr;14(4):1338-1345. Epub 2025 Apr 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Larson LM, Thomas T, Kurpad AV, Martorell R, Hoddinott J, Adebiyi VO, Swaminathan S, Neufeld LM. Predictors of anaemia in mothers and children in Uttar Pradesh, India. Public Health Nutr. 2024 Jan 8;27(1):e30. 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Dwarkanath P, Vasudevan A, Thomas T, Anand SS, Desai D, Gupta M, Menezes G, Kurpad AV, Srinivasan K. Socio-economic, environmental and nutritional characteristics of urban and rural South Indian women in early pregnancy: findings from the South Asian Birth Cohort (START). Public Health Nutr. 2018 Jun;21(8):1554-1564. Epub 2018 Feb 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Perumal V. Reproductive risk factors assessment for anaemia among pregnant women in India using a multinomial logistic regression model. Trop Med Int Health. 2014 Jul;19(7):841-51. Epub 2014 Apr 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdallah F, John SE, Hancy A, Paulo HA, Sanga A, Noor R, Lankoande F, Chimanya K, Masumo RM, Leyna GH. Prevalence and factors associated with anaemia among pregnant women attending reproductive and child health clinics in Mbeya region, Tanzania. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022 Oct 5;2(10):e0000280. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Derso T, Abera Z, Tariku A. Magnitude and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women in Dera District: a cross-sectional study in northwest Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2017 Aug 1;10(1):359. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aziz Ali S, Abbasi Z, Feroz A, Hambidge KM, Krebs NF, Westcott JE, Saleem S. Factors associated with anemia among women of the reproductive age group in Thatta district: study protocol. Reprod Health. 2019 Mar 18;16(1):34. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mankelkl G, Kinfe B. Sociodemographic factors associated with anemia among reproductive age women in Mali; evidenced by Mali malaria indicator survey 2021: spatial and multilevel mixed effect model analysis. BMC Womens Health. 2023 May 27;23(1):291. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kare AP, Gujo AB. Anemia among Pregnant Women Attending Ante Natal Care Clinic in Adare General Hospital, Southern Ethiopia: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Health Serv Insights. 2021 Jul 29;14:11786329211036303. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ouzennou N, Amor H, Baali A. Socio-economic, cultural and demographic profile of a group of Moroccan anaemic pregnant women. Afr Health Sci. 2019 Sep;19(3):2654-2659. 2019. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lebso M, Anato A, Loha E. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in Southern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2017 Dec 11;12(12):e0188783. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gedefaw L, Ayele A, Asres Y, Mossie A. Anemia and Associated Factors Among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care Clinic in Wolayita Sodo Town, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2015 Apr;25(2):155-62. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Abriha A, Yesuf ME, Wassie MM. Prevalence and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women of Mekelle town: a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes. 2014 Dec 9;7:888. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ouzennou N, Tikert K, Belkedim G, Jarhmouti FE, Baali A. Prévalence et déterminants sociaux de l'anémie chez les femmes enceintes dans la Province d'Essaouira, Maroc [Prevalence and social determinants of anemia in pregnant women in Essaouira Province, Morocco]. Sante Publique. 2018 September-October;30(5):737-745. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam A, Khaled H, Alrefaey AK, Basil A, Ibrahim S, Elsayed MS, Khattab M, Nabil N, Abdalwanees E, Halim HWA. Anemia in pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence, determinants, and health impacts in Egypt. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2025 Jan 14;25(1):29. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eweis M, Farid EZ, El-Malky N, Abdel-Rasheed M, Salem S, Shawky S. Prevalence and determinants of anemia during the third trimester of pregnancy. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2021 Aug;44:194-199. Epub 2021 Jul 2. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Workicho A, Belachew T, Ghosh S, Kershaw M, Lachat C, Kolsteren P. Burden and determinants of undernutrition among young pregnant women in Ethiopia. Matern Child Nutr. 2019 Jul;15(3):e12751. Epub 2018 Dec 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Diddana TZ. Factors associated with dietary practice and nutritional status of pregnant women in Dessie town, northeastern Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019 Dec 23;19(1):517. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gebremichael MA, Belachew Lema T. Dietary Diversity, Nutritional Status, and Associated Factors Among Pregnant Women in Their First Trimester of Pregnancy in Ambo District, Western Ethiopia. Nutr Metab Insights. 2023 Aug 22;16:11786388231190515. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Muze M, Yesse M, Kedir S, Mustefa A. Prevalence and associated factors of undernutrition among pregnant women visiting ANC clinics in Silte zone, Southern Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Nov 19;20(1):707. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahmed A, Mohammed A, Ateye MD, Abdusamed S. Prevalence of undernutrition and associated factors among adolescent pregnant women in Dolo-Ado town, Somali region, Ethiopia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2025 Jan 31;25(1):105. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vindhya J, Nath A, Murthy GVS, Metgud C, Sheeba B, Shubhashree V, Srinivas P. Prevalence and risk factors of anemia among pregnant women attending a public-sector hospital in Bangalore, South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019 Jan;8(1):37-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nair MS, Raphael L, Chandran P. Prevalence of anaemia and associated factors among antenatal women in rural Kozhikode, Kerala. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022 May;11(5):1851-1857. Epub 2022 May 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bharati P, Som S, Chakrabarty S, Bharati S, Pal M. Prevalence of anemia and its determinants among nonpregnant and pregnant women in India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2008;20(4):347-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin Y, Talegawkar SA, Sedlander E, DiPietro L, Parida M, Ganjoo R, Aluc A, Rimal R. Dietary Diversity and Its Associations with Anemia among Women of Reproductive Age in Rural Odisha, India. Ecol Food Nutr. 2022 May-Jun;61(3):304-318. Epub 2021 Oct 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak P, Kapil U, Kapoor SK, Saxena R, Kumar A, Gupta N, Dwivedi SN, Singh R, Singh P. Prevalence of multiple micronutrient deficiencies amongst pregnant women in a rural area of Haryana. Indian J Pediatr. 2004 Nov;71(11):1007-14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnath A, Debbarma A, Debbarma SK, Bhattacharjya H. Proportion of anaemia and factors associated with it among the attendees of the antenatal clinic in a teaching institute of northeast India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021 Jan;10(1):283-288. Epub 2021 Jan 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghosh P, Dasgupta A, Paul B, Roy S, Biswas A, Yadav A. A cross-sectional study on prevalence and determinants of anemia among women of reproductive age in a rural community of West Bengal. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020 Nov 30;9(11):5547-5553. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bobdey S, Sinha S. Prevalence of anemia among women: A pilot study. Med J Armed Forces India. 2012 Oct;68(4):407-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.04.019. Epub 2012 Aug 22. Epub 2012 Aug 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mehrotra M, Yadav S, Deshpande A, Mehrotra H. A study of the prevalence of anemia and associated sociodemographic factors in pregnant women in Port Blair, Andaman and Nicobar Islands. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018 Nov-Dec;7(6):1288-1293. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pradhan S, Karna T, Singha D, Bhatta P, Rath K, Behera A. Prevalence and risk factor of anemia among pregnant women admitted in antenatal ward in PBMH Bhubaneswar, Odisha. J Family Med Prim Care. 2023 Nov;12(11):2875-2879. Epub 2023 Nov 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Samuel TM, Thomas T, Finkelstein J, Bosch R, Rajendran R, Virtanen SM, Srinivasan K, Kurpad AV, Duggan C. Correlates of anaemia in pregnant urban South Indian women: a possible role of dietary intake of nutrients that inhibit iron absorption. Public Health Nutr. 2013 Feb;16(2):316-24. Epub 2012 May 11. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sharma N, Kishore J, Gupta M, Singla H, Dayma R, Sharma JB. The Minimum Dietary Diversity for Women (MDD-W) Score: Its Association With the Prevalence and Severity of Anemia in Pregnancy. Cureus. 2024 Aug 5;16(8):e66248. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lukose A, Ramthal A, Thomas T, Bosch R, Kurpad AV, Duggan C, Srinivasan K. Nutritional factors associated with antenatal depressive symptoms in the early stage of pregnancy among urban South Indian women. Matern Child Health J. 2014 Jan;18(1):161-170. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalaivani K. Prevalence & consequences of anaemia in pregnancy. Indian J Med Res. 2009 Nov;130(5):627-33. [PubMed]

- Thasneem NB, Kaimal RS, Thengu Murichathil AH. Study of sociodemographic factors and perceptions of women in the reproductive age group with anaemia - A hospital-based cross-sectional study in South India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2025 Apr;14(4):1338-1345. Epub 2025 Apr 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).