1. Introduction

Anemia was common in low- and middle-income countries [

1,

2]. The World Health Organization defines anemia as a decrease in the proportion of red blood cells, a reduction in the concentration of hemoglobin levels, or an inadequate oxygen-carrying capacity to meet the physiological requirements [

3]. Anemia had different precipitating factors, and the most common cause of anemia in the general population was iron deficiency. Women were constantly a high-risk group for anemia in global [

1,

4,

5]. An estimate by the World Health Organization (WHO) that around to over half a billion women or 29.9% of reproductive women aged 15-49 years were suffering from anemia in 2019 and most of them suffer due to iron deficiency [

6]. The problem of anemia in women was also quite severe in China [

2]. Pre- and postpartum women are both at particularly high risk for iron deficiency anemia due to the increased nutritional demands of the mother, the fetus and the infant during this period. The health of mothers during pregnancy and lactation was directly related to the health of their offsprings. Anemia had a negative impact on women of reproductive age as well as on child health, which, in turn, lead to an increase in morbidity and maternal mortality, and also impeded social-economic development [

5,

7,

8]. Currently, multiple studies [

9,

10,

11,

12] focus on anemia in pregnant women which was resulted from the high incidence of anemia among pregnant women and its direct impacts on the growth and development of the fetus or infant, such low birth weight and so on.

However, there was little attention paid to anemia and its precise intervention in women within two years postpartum. In fact, the problem of anemia among postpartum women remains severe [

13]. It is directly related to postpartum recovery and can also affect the growth and development of infants by influencing the nutritional status of breast milk. An India study [

14] found that 47.3% of women within 6 weeks postpartum suffering from anemia. Therefore, more attention should be paid to postpartum women and their children at higher risk for anemia, to achieve early detection and early diagnosis and early treatment. Hence, the purpose of this study was to determine the high-risk groups of iron deficiency anemia in postpartum women and their offspring, meanwhile exploring biomarkers for early warning anemia in mothers during pregnancy and lactation, thus helping identify infants at high risk for anemia, ultimately, providing the basis for formulating the relevant intervention policy of iron deficiency anemia for postpartum women and their offspring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was based on data obtained from the China National Nutrition and Health Survey 2016–2017 (CHNNS2016-2017). Our study chose women within 2 years postpartum and their offspring from ten investigation sites in Zhejiang Province, to form a representative provincial sample of Zhejiang Province to assess the nutritional status of postpartum women. In Zhejiang Province, the field investigation, physical examination and blood specimen collection were conducted between September 2016 and November 2017. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (protocol code 201614 and approval date 3 June 2016). All women and children provided written informed consent after the research protocols were carefully explained to them.

2.2. Sampling Method and Study Population

This survey constitutes a part of the Chinese National Nutrition and Health Survey [

15]. The China National Nutrition and Health Survey conducted during 2016-mingx2017 was a cross-sectional study designed with the aim of investigating the health and nutritional status of children, adolescents, and women within two years postpartum. A multi-stage stratified cluster sampling method was adopted for participant selection. In Zhejiang Province, there were ten study sites that represented both urban and rural areas across the province. Subsequently, two townships or subdistricts were randomly selected from each study site. From the chosen townships or subdistricts, two villages or communities were randomly sampled. Finally, postpartum women within two years and their children under two years old, who resided in the selected villages or communities, were included and interviewed. At each survey site, at least 100 women and their corresponding children were interviewed. For this study, the inclusion criteria for the women and children were as follows: (1) agreed to participate in the study; (2) within 2 years after delivery (women) and their children less than 2 years old (children). The exclusion criteria were: (1) genetic metabolic disorders; (2) chronic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases; (3) mental illnesses.

2.3. Data Collection

General information questionnaires were used to collect data regarding women's age, nationality, educational level, occupation, parity, postpartum hemorrhage, the time when menstruation resumed, breastfeeding status, prenatal anemia, daily consumption of red meat and animal viscera, as well as iron supplementation during pregnancy and at present. Information about children's age, their daily intake of red meat and animal viscera, and iron supplementation was also collected through these questionnaires. Physical examinations were carried out by trained health workers from the local community health center. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (in kilograms) by the square of height (in meters), and then the subjects were categorized into three groups[

16] (lean: <18.5; normal: 18.5–23.9; overweight/obesity: ≥24 kg/m2).

2.4. Hemoglobin Determination

Whole blood hemoglobin concentration was measured using Hemocue hemoglobin meter on the spot. 10 microliters of blood were collected from women's fingertip and placed in the hemoglobin meter within 40 seconds. A quality control solution needs to be tested once whenever the machine was restarted or 20 to 30 samples was tested.

2.5. Blood Sample Collection and Measurement

Six milliliters of fasting venous blood were drawn. Serum ferritin, transferrin receptor levels were measured by a fully automated analyzer based upon electrochemiluminescence and immunoturbidimetric assay method. Serum B12 and folate levels were measured by a fully automated analyzer based upon the chemiluminescence immunometric assay method. Vitamin A levels were measured by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) method.

2.6. Definition of ANEMIA

According to WHO standards[

17], infants within one month with Hb < 145g/L, infants aged 1 to 6 months with Hb < 90g/L, children aged 6 months to <5 years with Hb < 110 g/L, children aged 5 to 11 years with Hb < 115 g/L, children aged 12 to 13 years and non-pregnant females over 14 years old with Hb < 120 g/L, were all defined as anemia. Anemia in adults was classified as Hb <80 g/L, Hb 80–100 g/L, and Hb 110–120 g/L as severe, moderate, and mild.

2.7. Statistical Analyses

Mean and standard deviations (mean±SD) were used to described continuous normal variables, and median and quartile (median (quartile)) were used for variables with skewed distribution. Frequency and percentage (%) were reported for the categorical variables. Continuous and categorical variables were compared using Student’s t-test and the chi-square test, respectively. A multiple logistic model was used to detect the association between postpartum time, BMI, iron supplement intake during pregnancy, red meat intake, serum vitamin A level, serum ferritin level, serum transferrin receptor level, anemia during pregnancy and incidence of anemia at present, respectively. These two models were also performed to investigate the relationship between influence factors in mothers and incidence of anemia in offsprings. Additionally, the figures were plotted based on Restricted Cubic Spline (RCS) Model. All statistical analyses were performed by using the program SAS version 9.1. p less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Basic Information

A total of 977 women within 2 years postpartum were enrolled in the current study. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in

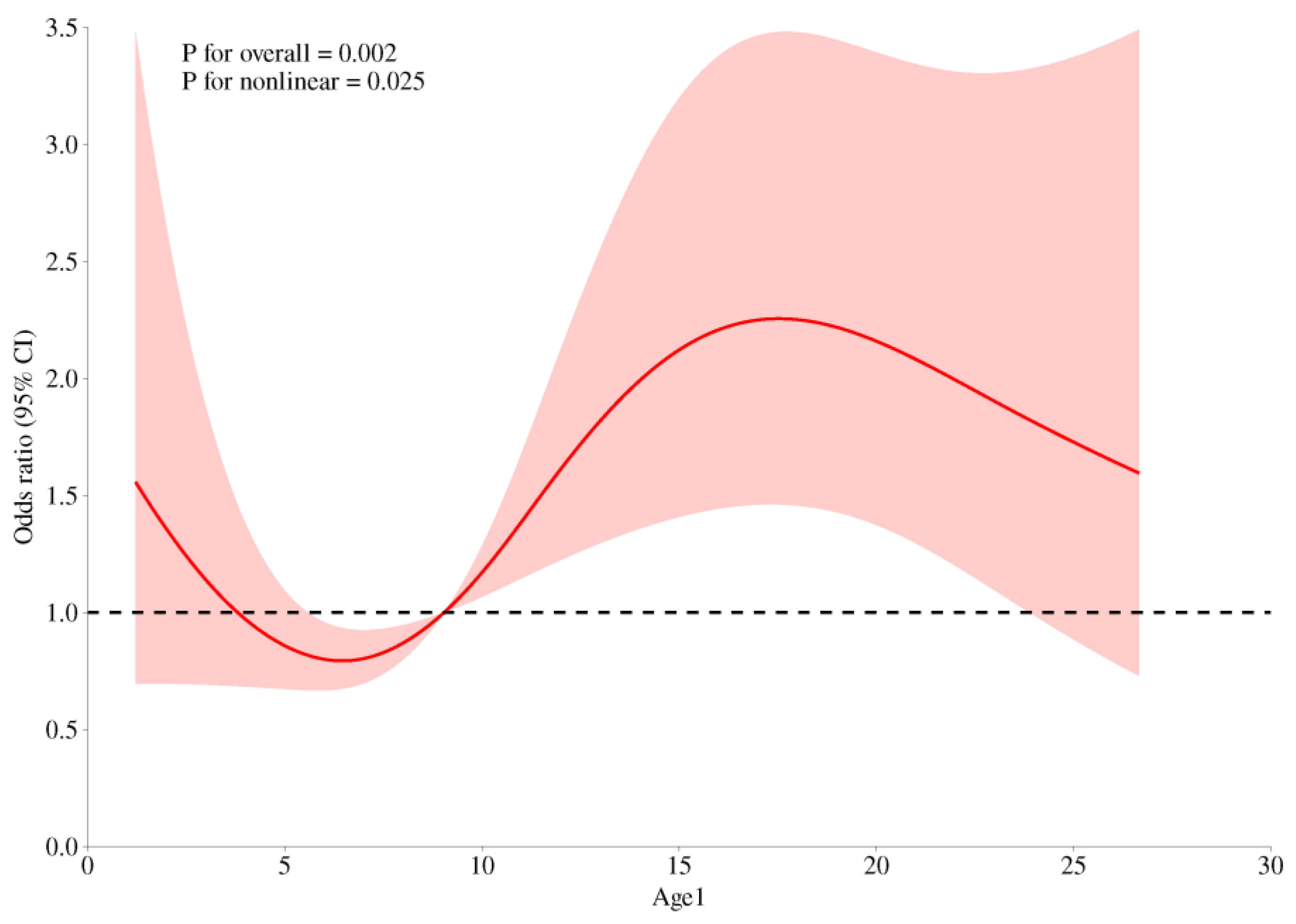

Table 1. Overall, the prevalence of anemia of 977 postpartum women was 14.74%. The risk of anemia in postpartum women increased significantly after 9 months postpartum (see

Figure 1).

3.2. Status and Determinants of Iron Deficiency Anemia and Iron Reserve in Postpartum Women

As is shown in

Table 2, longer postpartum time (p=0.012), overweight or obese(p=0.013), no iron supplement intake during pregnancy(p=0.008), less red meat intake(p=0.014), lower serum vitamin A(p=0.009), inadequate serum ferritin(p<0.0001), excessive serum transferrin receptor(p<0.0001) and anemia during pregnancy(p<0.0001) were associated with increased risk of anemia in postpartum women. Multivariate analysis of statistically significant factors (postpartum time, BMI, iron supplement intake during pregnancy, red meat intake, serum vitamin A level, serum ferritin level, serum transferrin receptor level and anemia during pregnancy) in univariate analysis showed that postpartum time, iron supplement intake during pregnancy, red meat intake, serum ferritin level, serum transferrin receptor level and anemia during pregnancy were associated with anemia in postpartum women (P < 0.05) in

Table 3. The risk of anemia in postpartum women was higher with longer postpartum time (OR=1.717, 95% CI=1.112~2.650). Iron supplement intake during pregnancy (OR=0.549, 95% CI=0.350~0.860) and ≥50g/d red meat intake (OR=0.549, 95% CI=0.350~0.860) were protective factors for anemia. Inadequate serum ferritin (OR=11.931, 95% CI=4.846~29.379), excessive serum transferrin receptor (OR=1.817, 95% CI=1.050~3.145) and anemia during pregnancy were risk factors for anemia.

3.3. The Influence on Offspring Anemia

Analysis of possible influencing factors of anemia in 968 infants aged 0-2 years was performed and showed in

Table 4. age of infant (p<0.001), whether the mother intake iron supplement during pregnancy (p=0.006), whether breastfeeding (p=0.043) and whether the mother had anemia during pregnancy (p=0.021) were associated with increased risk of anemia in infant. Multivariate analysis of above statistically significant factors, in

Table 5, showed that the risk of anemia in infants will increase significantly after 6 months of age. Additionally, maternal anemia during pregnancy, especially moderate to severe anemia, was a risk factor for anemia in offspring. On the contrary, maternal intake of iron nutritional supplements during pregnancy was a protective factor for anemia in offspring. An interesting thing was found that breastfeeding may be an important risk factor for anemia in offspring.

4. Discussion

The problem of anemia during pregnancy had received widespread attention [

9,

12,

20]. However, the nutritional status and postpartum recovery of postpartum women were equally important, meanwhile related to the health of their offspring. To date, few studies focused on anemia in postpartum women and its influence on offsprings, moreover, the evidence derived from previous studies might be rather outdated, and consequently, which called for an update [

21,

22,

23]. This study investigated the status and determinants of anemia in postpartum women, and its influence on the offspring. A total of 977 women within 2 years postpartum and 968 their offsprings were enrolled in the current study. The basic information indicated that the included survey subjects were evenly distributed in age ranging from 20 to 40 years old, and the postpartum age was evenly distributed between 1 month and 24 months. The nationality of subjects was predominantly Han. The region distribution, education level, and occupation were also evenly distributed. All above suggested that the survey subjects possess good representativeness. The results above showed that intaking iron supplements during pregnancy, sufficient intake of red meat, and normal serum ferritin and transferrin receptor levels were protective factors for anemia in postpartum women. Anemia during pregnancy and postpartum age > 7 months were risk factors for postpartum anemia. Mother intaking iron supplements during pregnancy was protective factors for anemia in offsprings. Mother anemia during pregnancy, age > 6 months, and breastfeeding were risk factors for offsprings. This result was generally consistent with the research evidence [

13,

14,

24] on the influencing factors of anemia in postpartum women available so far.

In the analysis of risk factors for anemia in postpartum women, by referring to existing domestic and foreign research evidences [

21,

22,

25,

26,

27], factors such as region, age, BMI, intake of iron nutritional supplements during pregnancy and postpartum and anemia during pregnancy and so on, were included. As results showed, intaking iron supplements during pregnancy, sufficient intake of red meat, and normal serum ferritin and transferrin receptor levels were protective factors for anemia in postpartum women. Anemia during pregnancy was a major risk factor for postpartum anemia. As the RCS model showed, the risk of anemia in postpartum women increased significantly after 9 months postpartum, which might be caused by the resumption of menstruation after childbirth. At the same time, it was worth noting that the risk of anemia of postpartum women significantly increased after seven months postpartum, which might be closely related to the restoration of postpartum menstruation. The incidence of anemia in postpartum women with a BMI less than 18.5 was significantly higher than that of others, indicating that being thin remained a major risk factor for anemia. However, some results were not quite consistent with the previous research evidence. There was no significant difference in the incidence of anemia among postpartum women in terms of urban-rural distribution, which may be due to the generally improved economic level. After the poverty alleviation campaign, anemia caused by malnutrition has been significantly improved, which had also been verified by similar studies [

28]. There was no statistical significance in the correlation between serum vitamin A level, serum vitamin B12 level, serum folic acid level and anemia in postpartum women, suggesting that main types of anemia were iron deficiency anemia, and the incidence rate vitamin B12-deficiency anemia and folate-deficiency anemia were relatively low [

29]. The number of postpartum women intaking iron supplements or suffering postpartum hemorrhage was very small, which may be the reason why there was no statistical difference in the intake of iron supplements or postpartum hemorrhage in the results. In conclusion, this study found that taking iron supplements during pregnancy and appropriate intake of red meat may effectively prevent the anemia. Additionally, postpartum women who diagnosed anemia during pregnancy or postpartum age more than nine months may be high-risk groups, and special attention should be paid to the occurrence of anemia. Combined with the evidence from previous studies [

30], serum ferritin and transferrin receptor, which reflect iron reserve, can provide early warning of the occurrence of anemia.

In the analysis of the influencing factors of anemia on offspring, by referring to existing research evidences [

31], factors such as region, age, parity of mother, whether breastfeeding, iron nutritional supplements intake of infants and their mothers during pregnancy, intake of red meat and animal viscera, maternal anemia now or during pregnancy, serum ferritin level and serum transferrin receptor level of mother were included. It was found that the risk of infant anemia significantly increased after six months after birth, which may be related to that iron reserves at birth were only sufficient to cover the iron demands for growth during the first 4-6 months of life [

32]. Through an analysis of how the influencing factors of mothers during the postpartum stage and pregnancy affect the anemia of their offspring, we discovered that the former exerts a more significant role. This might be attributed to the fact that the accretion of iron in the fetus mainly takes place during the third trimester of pregnancy [

31]. The results showed that intake of iron supplement during pregnancy and diagnosed anemia during pregnancy had a more significant impact on the risk of anemia in offspring, which suggests that more attention should paid to the iron nutritional status and anemia prevention of pregnant women during the fetal period. An Ethiopian study [

33] showed that government had already attached great importance to iron supplementation for pregnant women and was committed to improving adherence to iron supplementation. Additionally, an interesting finding was that breastfeeding actually increased the risk of anemia in offspring. Human milk is the ideal food for infants because of its unique nutritional characteristics, but iron in it decreased progressively from day 1 to 14 weeks and at 6 months in both nonanemic and anemic mothers, and breastmilk iron and lactoferrin concentration had no relationship with the mother’s Hb and iron status [

34]. Therefore, it reminded us to pay attention to the intake of iron supplements for breastfed infants.

There were several strengths in our study. Firstly, this study evaluated the status of anemia both in women during pregnancy and postpartum within 2 years and in their offsprings, while other studies have only focused on the anemia in pregnant or lactating women or children. Meanwhile, the influences of maternal factors during pregnancy and postpartum on anemia in offspring were compared simultaneously in this study. Secondly, the present study showed that iron supplement during pregnancy are important factors for prevention of anemia in postpartum women and their offsprings. Thirdly, postpartum 9 months and 6 months after birth may be high-risk time points for the occurrence of anemia in postpartum women and infants. Lastly, it was found that breastfeeding might be a risk factor for infant anemia, which suggested that attention should be paid to the early iron supplement for breastfed infants. However, this study has the following limitations, and caution should be exercised in interpreting and extrapolating the results. Firstly, a cross-sectional design was adopted in this study. Consequently, this design can only suggest the possible influencing factors for maternal anemia and cannot clarify the causal relationships. Secondly, the information such as diagnosis of Anemia during pregnancy, nutrient supplement and dietary data were self-reported and might have been influenced by recall bias. Thirdly, the anemia status of pregnant women may vary at different periods and under different interventions. Since this study only selected single sample, it cannot objectively present the dynamic change process. Future studies can collect the results of multiple blood samples as well as information on interventions. Finally, the overall anemia rate of the patients included in the study was relatively low, and the sample size was limited, resulting in relatively wide confidence intervals. Therefore, it is still necessary to conduct larger-scale studies in the future.

5. Conclusions

To summarize, anemia during the postpartum period is an important public health issue, and the rise in hemoglobin after delivery was not adequate in our study population. The status of anemia in postpartum women was severe and worthy of attention, meanwhile, its impact on the anemia of their offspring also alerted us. Anemia during the pregnancy, postpartum age > 7 months, insufficient intake of red meat no iron supplementation during the postpartum period and abnormal serum ferritin and transferrin receptor levels were identified as significant risk factors associated with anemia in postpartum women. Maternal anemia during pregnancy, no iron supplementation during pregnancy, the maternal postpartum period age > 6 months, and breastfeeding were risk factors for offsprings. Ensuring an adequate intake of red meat and regular intaking of iron supplements during pregnancy, actively preventing or treating anemia during pregnancy, and simultaneously paying attention to biomarkers (such as ferritin and transferrin receptor) that indicate iron reserves can effectively reduce the risk of anemia in postpartum. The risk of anemia may increase after seven months postpartum. For offsprings, the fetal period has a greater impact on the risk of infant anemia compared to the postnatal infant period. Meanwhile, attention should be paid to the iron supplementation of infants aged over six months or those who are breastfed, so as to prevent or treat anemia in a timely manner.

Author Contributions

Lichun Huang and Ronghua Zhang conceptualized and designed the study; Yan Zou, Danting Su and Dong Zhao performed the experiments; Mengjie, Dan Han and Peiwei Xu analyzed the data; Mengjie He wrote the paper; and Ronghua Zhang and Peiwei Xu were responsible for the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was complete with the financial support of Nutrition and Health Monitoring Project for Chinese Children and Adolescents Aged 0 - 17 and Lactating Mothers..

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (protocol code 201614 and approval date 3 June 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical concerns in this survey.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants who took part in this study, especially nutrition monitoring surveyors from local CDCs in 10 regions. In addition, sincere gratitude was given to Dr. Wang Le from Zhejiang Cancer Hospital for his support in the suggestion on statistical methods of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sharif, N.; Das, B.; Alam, A. Prevalence of anemia among reproductive women in different social group in India: Cross-sectional study using nationally representative data. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0281015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LNL NY, Y.; WW, Z.Z.; HQH QH, H. , et al. Prevalence and trends of anemia among pregnant women in eight provinces of China from 2016 to 2020. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine 2023, 57, 736–740. [Google Scholar]

- Organization, W.H. Hemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anemia and assessment of severity[S]. Geneva: Switzerland: 2011.

- Elmugabil, A.; Adam, I. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors for Anemia in Pregnant Women in White Nile State, Sudan: A Cross-Sectional Study. SAGE Open Nursing 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, N.; Ye, E.; Ba, Y., et al. The global burden of maternal disorders attributable to iron deficiency related sub-disorders in 204 countries and territories: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. Global Anemia estimates 2021 edition[S]. Geneva, Switzerland 2020: 2021.

- Sunguya, B.F.; Ge, Y.; Mlunde, L. , et al. High burden of anemia among pregnant women in Tanzania: a call to address its determinants. Nutrition Journal 2021, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Sun, M.; Wu, T. , et al. The association between maternal anemia and neonatal anemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2024, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasaribu, R.D.; Aritonang, E.; Sudaryati, E. , et al. Anemia in Pregnancy: Study Phenomenology. Portuguese Journal of Public Health 2024, 42, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LLL LT, T.; ASA SA, A.; HH, T.T., et al. Determinants of severity levels of anemia among pregnant women in Sub-Saharan Africa: multilevel analysis.. Frontiers in global women's health. Frontiers in global women's health. 2024; 1367426.

- S S U U, H H S S, A A Y Y, et al. Anemia among pregnant women in Cambodia: A descriptive analysis of temporal and geospatial trends and logistic regression-based examination of factors associated with anemia in pregnant women.. PloS one. 2023, e0274925.

- FF, G.G.; GG, S.S.; AAA AT, T. Persistence of a high prevalence of anemia in rural areas among pregnant women in Burkina Faso. A cross-sectional study.. Journal of public health in Africa. 2023, 2734.

- Zhao, A.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W. , et al. Postpartum anemia is a neglected public health issue in China: a cross-sectional study. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2019, 28, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rakesh, P.; Gopichandran, V.; Jamkhandi, D. , et al. Determinants of postpartum anemia among women from a rural population in southern India. International journal of women's health 2014, 6, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Liu, A.; Yao, Y., et al. nutrient supplement use among the chinese population: a cross-sectional study of the 2010-2012 china nutrition and health surveillance. 2019.

- Chen, C. Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Overweight and Obesity in Chinese Adults [M]. 3. Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House 2006.

- Organisation, W.H. Haemoglobin Concentrations for the Diagnosis of Anaemia and Assessment of Severity. Vitamin and Nutritional Information System[S]. Geneva: 2011.

- Babaei, M.; Shafiei, S.; Bijani, A. , et al. Ability of serum ferritin to diagnose iron deficiency anemia in an elderly cohort. Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia 2017, 39, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mei, Z.; Pfeiffer, C.M.; Looker, A.C. , et al. Serum soluble transferrin receptor concentrations in US preschool children and non-pregnant women of childbearing age from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2010. Clinica Chimica Acta 2012, 413, 1479–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NN, M.M. Prepartum anaemia: prevention and treatment. . Annals of hematology. 2008, 949–959. [Google Scholar]

- Milman, N. Postpartum anemia I: definition, prevalence, causes, and consequences. Annals of Hematology 2011, 90, s00277–s011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abneh, A.A.; Kassie, T.D.; Gelaw, S.S. The magnitude and associated factors of immediate postpartum anemia among women who gave birth in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis 2023. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2024, 24(1). [CrossRef]

- Milman, N. Postpartum anemia II: prevention and treatment. Annals of Hematology 2012, 91, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butwick, A.J.; McDonnell, N. Antepartum and postpartum anemia: a narrative review. International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia 2021, 47, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinmei, Z. Effect of nutritional supplements during pregnancy on occurrence of anemia in pregnant women. Clinical Research and Practice 2023, 8, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E E Y Y, A A Y Y, M M M M, et al. Relationship between patient ethnicity and prevalence of anemia during pregnancy and the puerperium period and compliance with healthcare recommendations - implications for targeted health policy.. Israel journal of health policy research. 2020, 71.

- Eshete, N.A.; Mittiku, Y.M.; Mekonnen, A.G. , et al. Immediate postpartum anemia and associated factors at shewarobit health facilities, Amhara, Ethiopia, 2022: a cross sectional study. BMC Women's Health 2024, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y. Comparison and analysis on health status of pregnant women and food habits of postpartum women between urban and rural areas of Shandong Province.[D]. Qingdao University, 2011.

- Metz, J. A High Prevalence of Biochemical Evidence of Vitamin B12 or Folate Deficiency does not Translate into a Comparable Prevalence of Anemia. Food and nutrition bulletin 2008, 29, S74–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirosawa, T.; Hayashi, A.; Harada, Y. , et al. The Clinical and Biological Manifestations in Women with Iron Deficiency Without Anemia Compared to Iron Deficiency Anemia in a General Internal Medicine Setting: A Retrospective Cohort Study. International journal of general medicine 2022, 15, 6765–6773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirata, M.; Kusakawa, I.; Ohde, S. , et al. Risk factors of infant anemia in the perinatal period. Pediatrics International 2017, 59, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UMU MS, S.; MAM AS, S. Developmental changes in red blood cell counts and indices of infants after exclusion of iron deficiency by laboratory criteria and continuous iron supplementation.. The Journal of pediatrics., 1978, 412-416.

- Delie A M, Gezie L D, Gebeyehu A A, et al. Trend of adherence to iron supplementation during pregnancy among Ethiopian women based on Ethiopian demographic and health surveys: A Multivariable decomposition analysis. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022,. [CrossRef]

- Shashiraj MF, O.S. ORIGINAL ARTICLE Mother ‘s iron status, breastmilk iron and lactoferrin – are they related. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2006, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).