Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

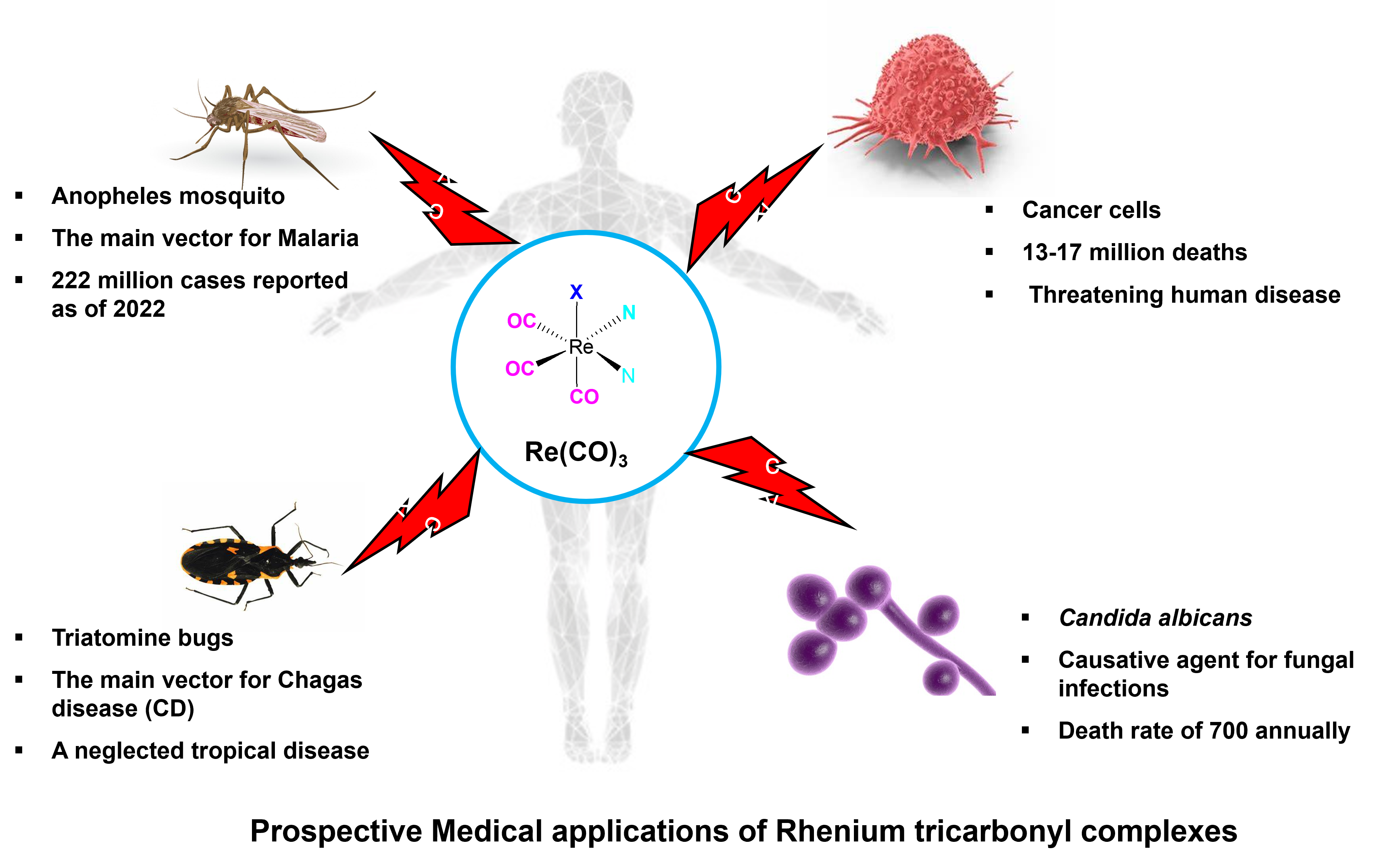

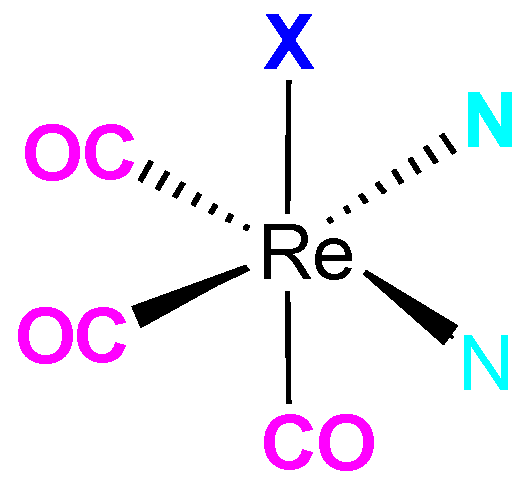

1. Introduction

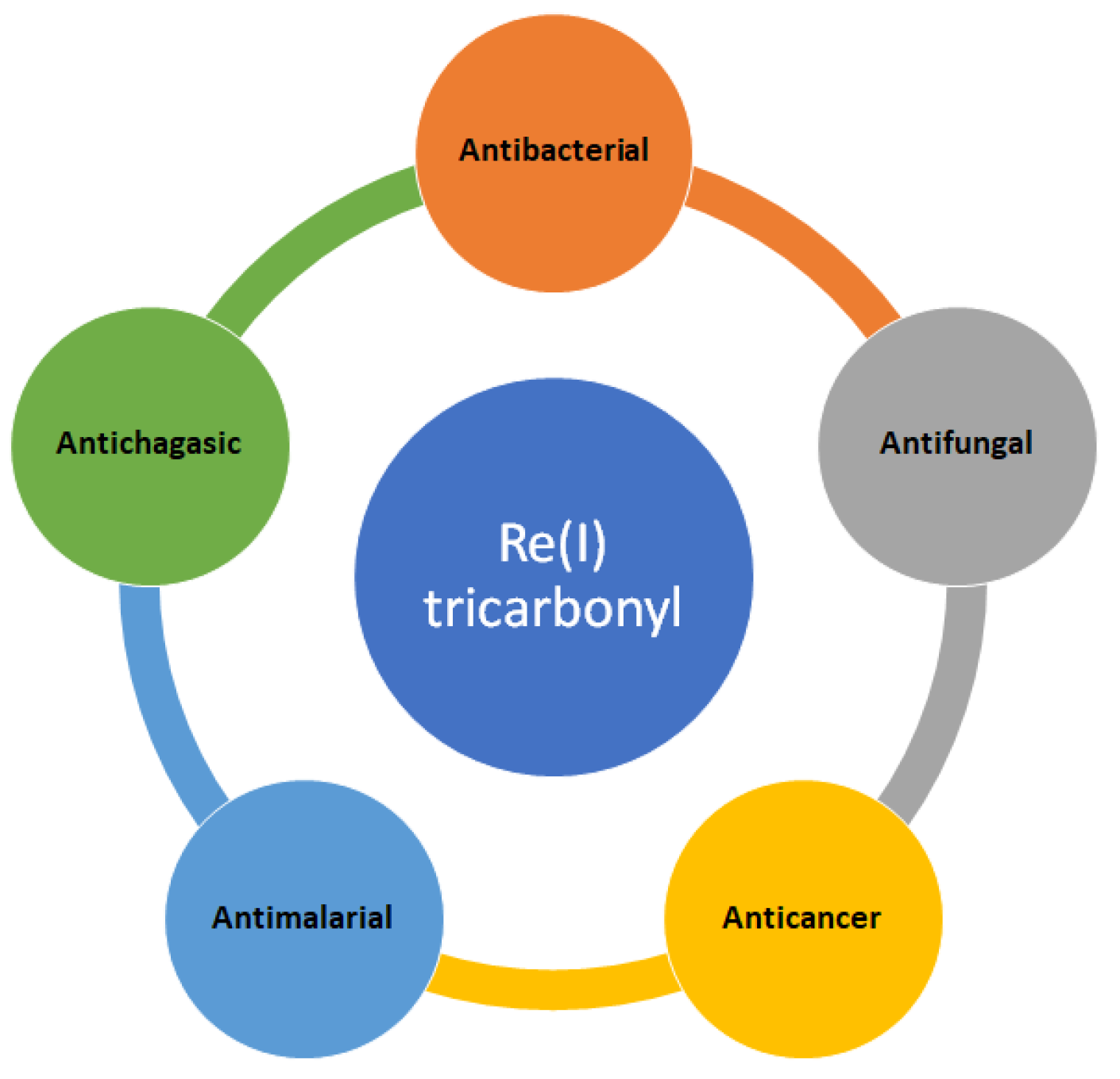

2. Medical Applications of Re(I)Tricarbonyl Complexes

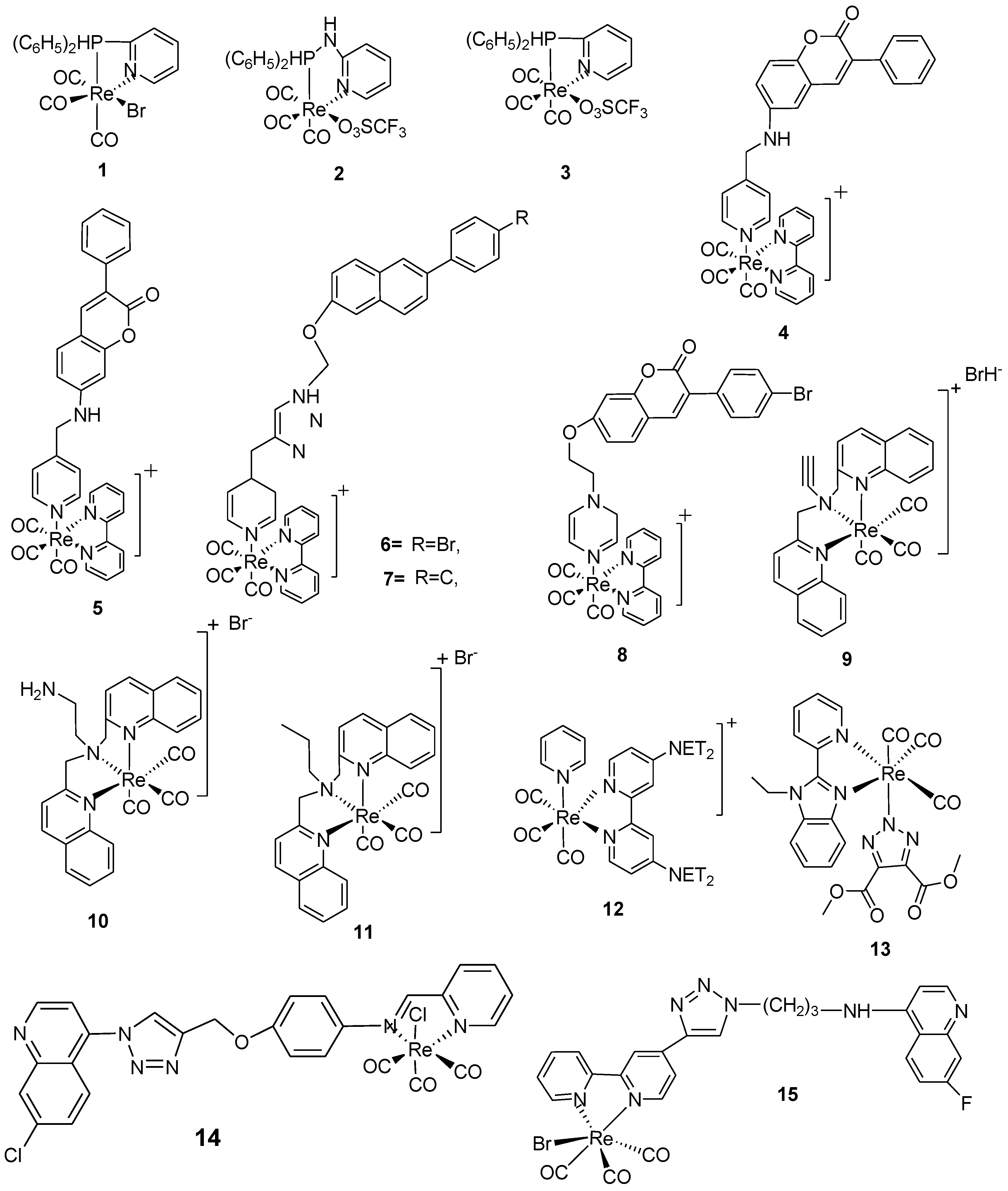

2.1. Antibacterial Applications

2.3. Antimalarial Activities

| Complexes | IC50 value (µM) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum | L1 | References | |

| 14 | 4.61 | - | [32,33] |

| 15 | 0.356 | 0.611 | [32,33] |

| 16 | 0.441 | 1.80 | [32,33] |

| CDP | 0.014 | 0.247 | [32,33] |

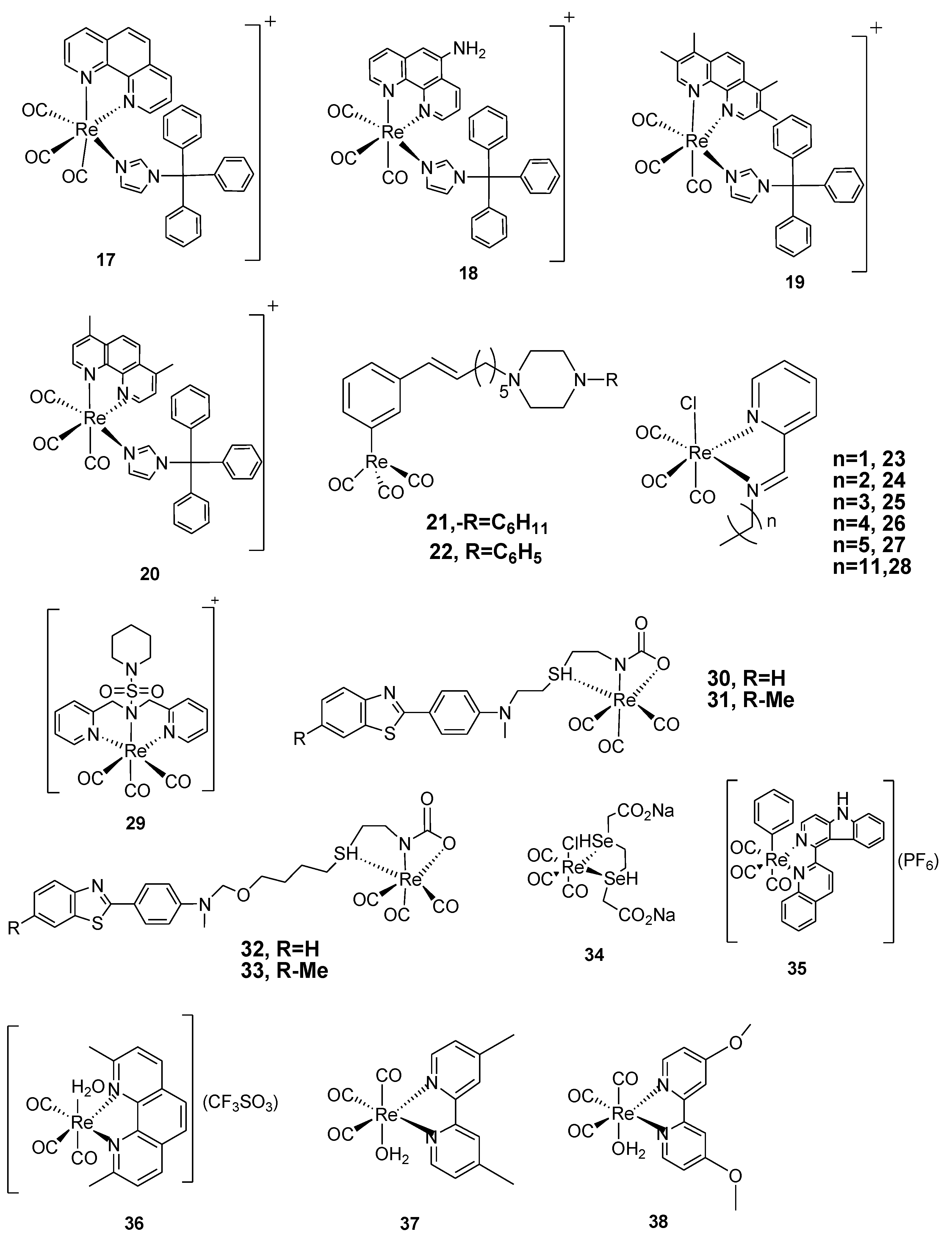

2.4. Antichagasic Activities

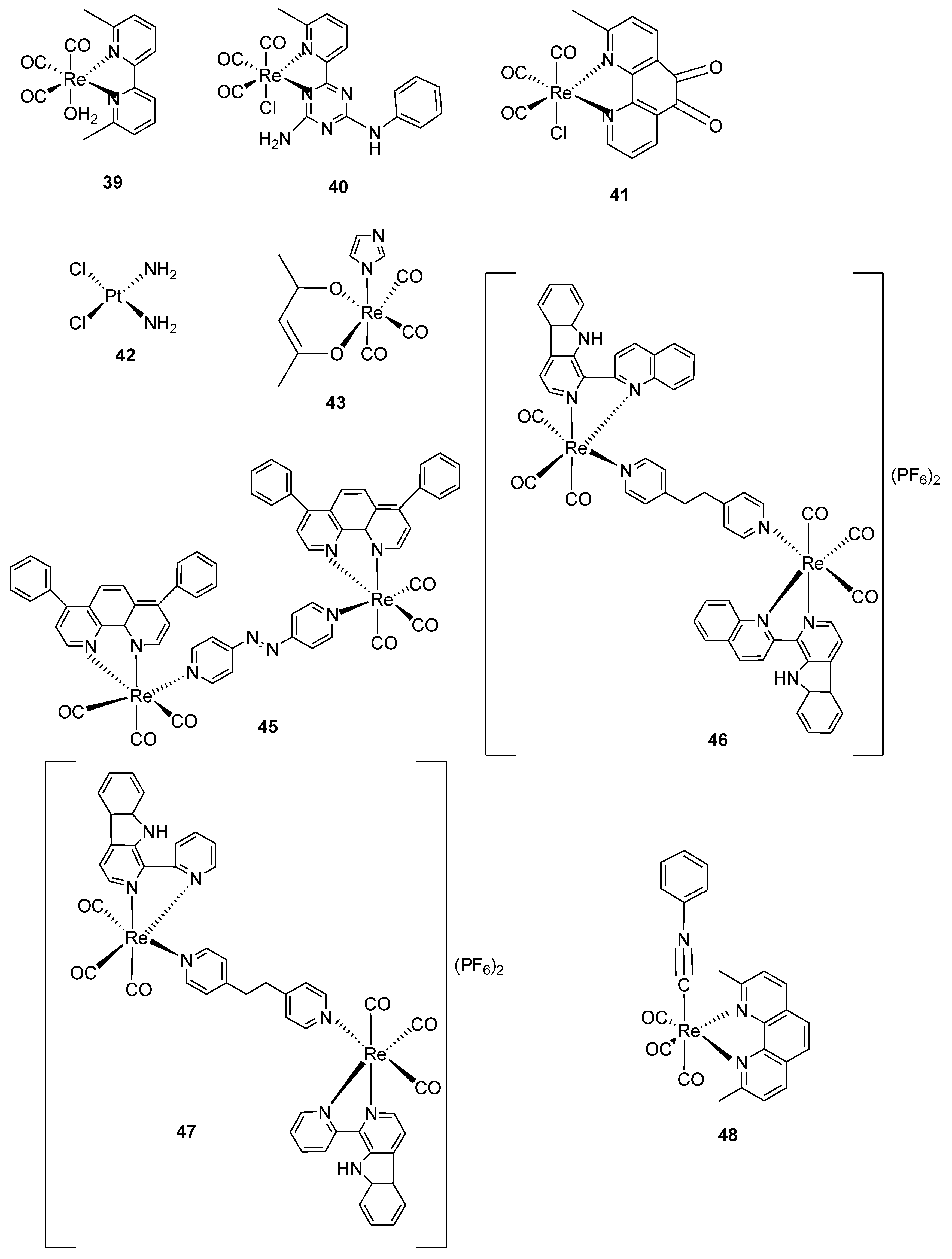

2.5. Anticancer Activities

| Cell line | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KB-3-1 | – | – | 0.92±0.2 | – | [66] | |||||

| KBCP20 | – | – | 1.6±0.4 | – | [66] | |||||

| A2780 | – | – | 2.2±0.2 | 3.5 ±2.8 | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | – | – | 0.23 ± 0.07 | [66] |

| A2780 CP70 | – | – | 3.0±0.7 | – | – | – | – | [66] | ||

| A549 | 133.2±4.3 | 2.2±0.2 | 6.7±4.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | [66] |

| AF49 CisR | – | 2.1±0.1 | 5.4±1.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | [66] |

| H460 | – | – | 4.5±0.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | [66] |

| H460 CisR | – | – | 5.3±2.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| MRC-5 | – | – | 4.1±0.9 | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| HeLa | 126.4±2.8 | 1.8±0.2 | 1.2±0.2 | – | – | – | – | – | 6.6 ± 0.7 | [66,67] |

| MCF-7 | 51.4±3.0 | 2.2±0.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [66,67] |

| T98G | – | – | – | – | >50 | [66,67] | ||||

| PC3 | 59.4±3.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | >50 | 2.19 ± 0.11 | [66,67] |

| HepG2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10.5 ± 0.5 | [66,67] |

| LO2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [66,67] |

| HLF | – | 12.7±0.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [66,67] |

| MDA-MB-231 | 48.5±2.8 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | [66,67] |

| PT-45 | – | – | – | >250 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | [66,67] | ||||

| HT-29 | 47.5 ±0.9 | – | – | – | – | – | >250 | 32.6 ± 0.7 | [66,67] |

3. Rhenium Labelling

3.1. Antifungal Activities

4. Conclusion

| Cell line | Description |

| HeLa | Cervical cancer cell |

| A2780 | Human ovary epithelial cell, ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma |

| HT-29 | Human colon epithelial cell, adenocarcinoma. |

| PT-45 | Human pancreas epithelial cell, adenocarcinoma. |

| T98G | Human brain fibroblast, glioblastoma. |

| PC3 | Human prostate epithelial cell, adenocarcinoma |

| HepG2 | Human liver epithelial cell, hepatocellular carcinoma. |

| KB-3-1 | Cervix carcinoma (a subclone of HELA) |

| KBCP20 | Breast cancer carcinoma |

| A2780CP70 | Ovarian endometroid adenocarcinoma |

| A549 | Lung carcinoma epithelial cells |

| H460 | Type II pulmonary epithelium carcinoma |

| H460CisR | Lewis lung carcinoma |

| MRC-5 | Fetal lung fibroblast cell carcinoma |

| MCF-7 | Breast cancer |

| LO2 | Human fetal hepatocyte cell line |

| HLF | Liver carcinoma cell lines |

| MDA-MB-231 | Epithelial, human breast cancer cell line |

Author Contributions

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fokunang, E.T.; Fokunang, C.N. Overview of the Advancement in the Drug Discovery and Contribution in the Drug Development Process. Journal of Advances in Medical and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2022, 24, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, N.A.; Muñoz, A.L.; Losada-Barragán, M.; Torres, O.; Rodríguez, A.K.; Rangel, H.; et al. Minireview: Epidemiological impact of arboviral diseases in Latin American countries, arbovirus-vector interactions and control strategies. Pathogens and Disease. 2021, 79, ftab043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Zhao, T.; Kang, D.; Zhang, J.; Song, Y.; Namasivayam, V.; et al. Overview of recent strategic advances in medicinal chemistry. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2019, 62, 9375–9414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organization, W.H. Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report: 2021. 2021.

- Shaw, J.A. World Disease BIO242.

- Morrison, L.; Zembower, T.R. Antimicrobial resistance. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics. 2020, 30, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkharashi, N.; Aljohani, S.; Layqah, L.; Masuadi, E.; Baharoon, W.; Al-Jahdali, H.; et al. Candida bloodstream infection: changing pattern of occurrence and antifungal susceptibility over 10 years in a tertiary care Saudi hospital. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santolaya, M.E.; Thompson, L.; Benadof, D.; Tapia, C.; Legarraga, P.; Cortés, C.; et al. A prospective, multi-center study of Candida bloodstream infections in Chile. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0212924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroe, A.; Williams, N.A.; Ogoma, S.; Karema, C.; Okumu, F. Reflections on the 2021 World Malaria Report and the future of malaria control. BioMed Central; 2022.

- Alkadir, S.; Gelana, T.; Gebresilassie, A. A five year trend analysis of malaria prevalence in Guba district, Benishangul-Gumuz regional state, western Ethiopia: a retrospective study. Tropical Diseases, Travel Medicine and Vaccines. 2020, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.J. Anti-malarial drug effects on parasite dynamics in vivax malaria. Malaria Journal. 2021, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariuki, C.K. Deciphering the structure and function of select membrane associated proteins in haemo-protozoan parasites. 2022.

- Medina, L.J.; Chassaing, E.; Ballering, G.; Gonzalez, N.; Marqué, L.; Liehl, P.; et al. Prediction of parasitological cure in children infected with Trypanosoma cruzi using a novel multiplex serological approach: an observational, retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2021, 21, 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, L.E.; Marcus, R.; Novick, G.; Sosa-Estani, S.; Ralston, K.; Zaidel, E.J.; et al. WHF IASC Roadmap on Chagas Disease. Global heart. 2020, 15, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidani, K.C.F.; Andrade, F.A.; Bavia, L.; Damasceno, F.S.; Beltrame, M.H.; Messias-Reason, I.J.; et al. Chagas disease: from discovery to a worldwide health problem. Frontiers in public health. 2019, 7, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, O.M.; Viale, G.; Stein, S.; Trippa, L.; Yardley, D.A.; Mayer, I.A.; et al. Impact of HER2 heterogeneity on treatment response of early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer: phase II neoadjuvant clinical trial of T-DM1 combined with pertuzumab. Cancer discovery. 2021, 11, 2474–2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, D.; Abreu, C.M.; Lima, A.C.; Neves, N.N.; Reis, R.L.; Kundu, S.C. Precision biomaterials in cancer theranostics and modelling. Biomaterials. 2022, 280, 121299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari, S.; Soni, B.W.; Bahl, A.; Ghoshal, S. Radiotherapy-induced oral morbidities in head and neck cancer patients. Special Care in Dentistry. 2020, 40, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhatshwa, M.; Moremi, J.M.; Makgopa, K.; Manicum, A.-L.E. Nanoparticles functionalised with Re (I) tricarbonyl complexes for cancer theranostics. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021, 22, 6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaquinto, A.N.; Sung, H.; Miller, K.D.; Kramer, J.L.; Newman, L.A.; Minihan, A.; et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2022. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2022, 72, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kateb, B.; Chiu, K.; Black, K.L.; Yamamoto, V.; Khalsa, B.; Ljubimova, J.Y.; et al. Nanoplatforms for constructing new approaches to cancer treatment, imaging, and drug delivery: what should be the policy? Neuroimage. 2011, 54, S106–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, Q.; Wang, A.; Zaremba, O.; Shi, Y.; Scheeren, H.W.; Metselaar, J.M.; et al. Metallodrugs in cancer nanomedicine. Chemical Society Reviews. 2022, 51, 2544–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.C.-C.; Leung, K.-K.; Lo, K.K.-W. Recent development of luminescent rhenium (I) tricarbonyl polypyridine complexes as cellular imaging reagents, anticancer drugs, and antibacterial agents. Dalton Transactions. 2017, 46, 16357–16380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranasinghe, K.; Handunnetti, S.; Perera, I.C.; Perera, T. Synthesis and characterization of novel rhenium (I) complexes towards potential biological imaging applications. Chemistry Central Journal. 2016, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, A.; Antipán, J.; Fernández, M.; Prado, G.; Sandoval-Altamirano, C.; Günther, G.; et al. Photochemistry of P, N-bidentate rhenium (i) tricarbonyl complexes: Reactive species generation and potential application for antibacterial photodynamic therapy. RSC advances. 2021, 11, 31959–31966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikotun, A.A.; Owoseni, A.A.; Egharevba, G.O. Synthesis, physicochemical and antimicrobial properties of rhenium (I) tricarbonyl complexes of isatin Schiff bases. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2021, 20, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, D.; Dhayalan, V.; Chatterjee, R.; Khatravath, M.; Dandela, R. Recent advances in the synthesis of coumarin and its derivatives by using aryl propiolates. ChemistrySelect. 2022, 7, e202104299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulgencio, S.; Scaccaglia, M.; Frei, A. Exploration of Rhenium Bisquinoline Tricarbonyl Complexes for their Antibacterial Properties. ChemBioChem. 2024, 25, e202400435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, F.; Demirci, G.; Plackic, N.; Tran, B.; Crochet, A.; Cortat, Y.; et al. Rhenium tricarbonyl complexes of thiazolohydrazinylidene-chroman-2, 4-diones derivatives: antibacterial activity and in vivo efficacy. 2024.

- Patil, H.V.; Mohite, S.T.; Patil, V.C. Multidrug Resistant Acinetobacter in Patient with Ventilator Associated Pneumonia. Journal of Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences University. 2019, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sovari, S.N.; Radakovic, N.; Roch, P.; Crochet, A.; Pavic, A.; Zobi, F. Combatting AMR: A molecular approach to the discovery of potent and non-toxic rhenium complexes active against C. albicans-MRSA co-infection. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2021, 226:113858.

- Sovari, S.N.; Golding, T.M.; Mbaba, M.; Mohunlal, R.; Egan, T.J.; Smith, G.S.; et al. Rhenium (I) derivatives of aminoquinoline and imidazolopiperidine-based ligands: synthesis, in vitro and in silico biological evaluation against Plasmodium falciparum. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2022, 234, 111905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishmail, F.-Z. Antimalarial Evaluation of Quinoline-triazoleMn (I) and Re (I) PhotoCORMs: Faculty of Science; 2019.

- Soba, M.; Scalese, G.; Casuriaga, F.; Pérez, N.; Veiga, N.; Echeverría, G.A.; et al. Multifunctional organometallic compounds for the treatment of Chagas disease: Re (i) tricarbonyl compounds with two different bioactive ligands. Dalton Transactions. 2023, 52, 1623–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soba, M.; Scalese, G.; Pérez-Díaz, L.; Gambino, D.; Machado, I. Application of microwave plasma atomic emission spectrometry in bioanalytical chemistry of bioactive rhenium compounds. Talanta. 2022, 244, 123413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.C.; Libardi, S.H.; Borges, J.C.; Oliveira, R.J.; Gotzmann, C.; Blacque, O.; et al. Rhenium (I) and technetium (I) complexes with megazol derivatives: towards the development of a theranostic platform for Chagas disease. Dalton Transactions. 2024, 53, 19153–19165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Vaibhavi, N.; Kar, B.; Das, U.; Paira, P. Target-specific mononuclear and binuclear rhenium (i) tricarbonyl complexes as upcoming anticancer drugs. RSC advances. 2022, 12, 20264–20295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddhardha, B.; Parasuraman, P. Theranostics application of nanomedicine in cancer detection and treatment. Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery and Therapy: Elsevier; 2019. p. 59-89.

- Alshehri, S.; Imam, S.S.; Rizwanullah, M.; Akhter, S.; Mahdi, W.; Kazi, M.; et al. Progress of cancer nanotechnology as diagnostics, therapeutics, and theranostics nanomedicine: preclinical promise and translational challenges. Pharmaceutics. 2020, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liew, H.S.; Mai, C.W.; Zulkefeli, M.; Madheswaran, T.; Kiew, L.V.; Delsuc, N.; et al. Recent Emergence of Rhenium(I) Tricarbonyl Complexes as Photosensitisers for Cancer Therapy. Molecules. 2020, 25, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhatshwa, M.; Moremi, J.M.; Makgopa, K.; Manicum, A.E. Nanoparticles Functionalised with Re(I) Tricarbonyl Complexes for Cancer Theranostics. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.A. ; NV; Kar, B. ; Das, U.; Paira, P. Target-specific mononuclear and binuclear rhenium(i) tricarbonyl complexes as upcoming anticancer drugs. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 20264–20295. [Google Scholar]

- Sovari, S.N.; Vojnovic, S.; Bogojevic, S.S.; Crochet, A.; Pavic, A.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; et al. Design, synthesis and in vivo evaluation of 3-arylcoumarin derivatives of rhenium(I) tricarbonyl complexes as potent antibacterial agents against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Eur J Med Chem. 2020, 205, 112533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lavor, T.S.; Teixeira, M.H.S.; de Matos, P.A.; Lino, R.C.; Silva, C.M.F.; do Carmo, M.E.G.; etal., *!!! REPLACE !!!*. The impact of biomolecule interactions on the cytotoxic effects of rhenium (I) tricarbonyl complexes. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2024, 257, 112600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtemenko, N.; Galiana-Rosello, C.; Gil-Martínez, A.; Blasco, S.; Gonzalez-García, J.; Velichko, H.; et al. Two rhenium compounds with benzimidazole ligands: synthesis and DNA interactions. RSC advances. 2024, 14, 19787–19793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moherane, L.; Alexander, O.T.; Schutte-Smith, M.; Kroon, R.E.; Mokolokolo, P.P.; Biswas, S.; et al. Polypyridyl coordinated rhenium (I) tricarbonyl complexes as model devices for cancer diagnosis and treatment. Polyhedron. 2022, 228:116178.

- Schindler, K.; Horner, J.; Demirci, G.; Cortat, Y.; Crochet, A.; Mamula Steiner, O.; et al. In vitro biological activity of α-diimine rhenium dicarbonyl complexes and their reactivity with different functional groups. Inorganics. 2023, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovari, S.N.; Kolly, I.; Schindler, K.; Djuric, A.; Srdic-Rajic, T.; Crochet, A.; et al. Synthesis, characterization, and in vivo evaluation of the anticancer activity of a series of 5-and 6-(halomethyl)-2, 2′-bipyridine rhenium tricarbonyl complexes. Dalton Transactions. 2023, 52, 6934–6944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlou, M.L.; Malan, F.P.; Nkadimeng, S.; McGaw, L.; Tembu, V.J.; Manicum, A.-L.E. Exploring the in vitro anticancer activities of Re (I) picolinic acid and its fluorinated complex derivatives on lung cancer cells: a structural study. JBIC Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry. 2023, 28, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleynhans, J.; Duatti, A.; Bolzati, C. Fundamentals of Rhenium-188 Radiopharmaceutical Chemistry. Molecules. 2023, 28, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briggs, J.P. The zebrafish: a new model organism for integrative physiology. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2002, 282, R3–R9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frei, A.; Van Niekerk, A.; Joseph, C.M.; Kavanagh, A.; Dinh, H.; Swarts, A.J.; et al. The antimicrobial properties of Pd (II)-and Ru (II)-pyta complexes. 2023.

- Frei, A.; Amado, M.; Cooper, M.A.; Blaskovich, M.A. Light-Activated Rhenium Complexes with Dual Mode of Action against Bacteria. Chemistry–A European Journal. 2020, 26, 2852–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abubakar, T.A.; Eke, U.B.; Sylvestre, D.K. (Eds.) Isoniazid stabilized tungsten tricarbonyl complex: A new CO-releasing molecule with antibacterial activity. Science Forum (Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences); 2020: Faculty of Science, Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Bauchi.

- Betts, J.W.; Roth, P.; Pattrick, C.A.; Southam, H.M.; La Ragione, R.M.; Poole, R.K.; et al. Antibacterial activity of Mn (i) and Re (i) tricarbonyl complexes conjugated to a bile acid carrier molecule. Metallomics. 2020, 12, 1563–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enslin, L.E.; Purkait, K.; Pozza, M.D.; Saubamea, B.; Mesdom, P.; Visser, H.G.; et al. Rhenium (I) Tricarbonyl Complexes of 1, 10-Phenanthroline Derivatives with Unexpectedly High Cytotoxicity. Inorganic Chemistry. 2023, 62, 12237–12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrokhotova, Y.E.; Kazantseva, V.D.; Ozolinya, L.A. Bacterial vaginosis: modern aspects of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. VF Snegirev Archives of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2023, 10, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roemer, T.; Krysan, D.J. Antifungal drug development: challenges, unmet clinical needs, and new approaches. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2014, 4, a019703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.M. Tricarbonyl triazolato Re (i) compounds of pyridylbenzimidazole ligands: spectroscopic and antimicrobial activity evaluation. RSC advances. 2021, 11, 22715–22722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNICEFFD Public health round-up. Bull World Health Organ. 2023, 101, 301–302. [CrossRef]

- Sulleiro, E.; Muñoz-Calderon, A.; Schijman, A.G. Role of nucleic acid amplification assays in monitoring treatment response in chagas disease: Usefulness in clinical trials. Acta tropica. 2019, 199, 105120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Silva, J.; Menezes, D.S.; Fernandes, J.M.P.; Almeida, M.C.; Vasco-dos-Santos, D.R.; Saraiva, R.M.; et al. The repositioned drugs disulfiram/diethyldithiocarbamate combined to benznidazole: Searching for Chagas disease selective therapy, preventing toxicity and drug resistance. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2022, 12, 926699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, B.L.; Marker, S.C.; Lambert, V.J.; Woods, J.J.; MacMillan, S.N.; Wilson, J.J. Synthesis, characterization, and biological properties of rhenium (I) tricarbonyl complexes bearing nitrogen-donor ligands. Journal of Organometallic Chemistry. 2020, 907, 121064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uppal, B.S.; Booth, R.K.; Ali, N.; Lockwood, C.; Rice, C.R.; Elliott, P.I. Synthesis and characterisation of luminescent rhenium tricarbonyl complexes with axially coordinated 1, 2, 3-triazole ligands. Dalton Transactions. 2011, 40, 7610–7616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, D. Facial Rhenium Tricarbonyl Complexes with Modified DII Ligands. 2019.

- Capper, M.S.; Packman, H.; Rehkämper, M. Rhenium-based complexes and in vivo testing: A brief history. Chembiochem. 2020, 21, 2111–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manicum, A.-L.E.; Louis, H.; Mathias, G.E.; Agwamba, E.C.; Malan, F.P.; Unimuke, T.O.; et al. Single crystal investigation, spectroscopic, DFT studies, and in-silico molecular docking of the anticancer activities of acetylacetone coordinated Re (I) tricarbonyl complexes. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2023, 546, 121335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkankit, C.C.; King, A.P.; Knopf, K.M.; Southard, T.L.; Wilson, J.J. In vivo anticancer activity of a rhenium (I) tricarbonyl complex. ACS Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2019, 10, 822–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-X.; Liang, J.-H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.-H.; Wan, Q.; Tan, C.-P.; et al. Mitochondria-accumulating rhenium (I) tricarbonyl complexes induce cell death via irreversible oxidative stress and glutathione metabolism disturbance. ACS applied materials & interfaces. 2019, 11, 13123–13133. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Z.-Y.; Cai, D.-H.; He, L. Dinuclear phosphorescent rhenium (I) complexes as potential anticancer and photodynamic therapy agents. Dalton Transactions. 2020, 49, 11583–11590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlou, M.L.; Louis, H.; Charlie, D.E.; Agwamba, E.C.; Amodu, I.O.; Tembu, V.J.; et al. Anticancer Activities of Re (I) Tricarbonyl and Its Imidazole-Based Ligands: Insight from a Theoretical Approach. ACS omega. 2023, 8, 10242–10252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadachova, E.; Bouzahzah, B.; Zuckier, L.; Pestell, R. Rhenium-188 as an alternative to Iodine-131 for treatment of breast tumors expressing the sodium/iodide symporter (NIS). Nuclear medicine and biology. 2002, 29, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadachova, E.; Nguyen, A.; Lin, E.Y.; Gnatovskiy, L.; Lu, P.; Pollard, J.W. Treatment with rhenium-188-perrhenate and iodine-131 of NIS-expressing mammary cancer in a mouse model remarkably inhibited tumor growth. Nuclear medicine and biology. 2005, 32, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kothari, K.; Bapat, K.; Korde, A.; Sarma, H.; Suresh, R.; Padma, S.; et al. Radiochemical and biological studies of 188Re-labeled monoclonal antibody CAMA3C8 specific for breast cancer. Ind J Nuc Med. 2004, 19, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlfrom, M.; Kotzerke, J.; Kamenz, J.; Eble, M.; Hess, B.; Wöhrle, J.; et al. Endovascular irradiation with the liquid β-emitter Rhenium-188 to reduce restenosis after experimental wall injury. Cardiovascular research. 2001, 49, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-W.; Hong, M.-K.; Moon, D.H.; Oh, S.J.; Lee, C.W.; Kim, J.-J.; et al. Treatment of diffuse in-stent restenosis with rotational atherectomy followed by radiation therapy with a rhenium-188–mercaptoacetyltriglycine-filled balloon. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001, 38, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, B.-T.; Hsieh, J.-F.; Tsai, S.-C.; Lin, W.-Y.; Huang, H.-T.; Ting, G.; et al. Rhenium-188-Labeled DTPA: a new radiopharmaceutical for intravascular radiation therapy. Nuclear medicine and biology. 1999, 26, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höher, M.; Wöhrle, J.; Wohlfrom, M.; Kamenz, J.; Nusser, T.; Grebe, O.C.; et al. Intracoronary ß-Irradiation With a Rhenium-188–Filled Balloon Catheter. 2003.

- De Decker, M.; Bacher, K.; Thierens, H.; Slegers, G.; Dierckx, R.A.; De Vos, F. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of direct rhenium-188-labeled anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab for radioimmunotherapy of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nuclear medicine and biology. 2008, 35, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.A.; Hermann, S.; Dietrich, C.F.; Hoelzer, D.; Martin, H. Transplantation-related toxicity and acute intestinal graft-versus-host disease after conditioning regimens intensified with Rhenium 188–labeled anti-CD66 monoclonal antibodies. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2002, 99, 2270–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenecke, C.; Hofmann, M.; Bolte, O.; Gielow, P.; Dammann, E.; Stadler, M.; et al. Radioimmunotherapy with [188 Re]-labelled anti-CD66 antibody in the conditioning for allogeneic stem cell transplantation for high-risk acute myeloid leukemia. International journal of hematology. 2008, 87, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunjes, D. 188 Re-labeled anti-CD66 monoclonal antibody in stem cell transplantation for patients with high-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2002, 43, 2125–2131. [Google Scholar]

- Ringhoffer, M.; Blumstein, N.; Neumaier, B.; Glatting, G.; von Harsdorf, S.; Buchmann, I.; et al. 188Re or 90Y-labelled anti-CD66 antibody as part of a dose-reduced conditioning regimen for patients with acute leukaemia or myelodysplastic syndrome over the age of 55: results of a phase I–II study. British journal of haematology. 2005, 130, 604–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tian, M.; Li, S.; Liu, J.; Tanada, S.; Endo, K. Rhenium-188-HEDP therapy for the palliation of pain due to osseous metastases in lung cancer patients. Cancer Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2003, 18, 719–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Complexes | Bacterial strains (MIC µgmL-1 ) |

Outcomes | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | E. coli | |||

| 1 | 50 | 300 | The complex showed a candidate compound for the formulation of antibiotics | [25] |

| 2 | >300 | >300 | Low activity was noticed against the selected pathogens | [25] |

| 3 | 50 | 50 | Palpable antibacterial activity against selected test organisms was noticed. A clear indication that the complexes can be used in the formulation of antibiotics | [25] |

| Complexes | MIC values (mM) | Outcomes | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | E. faecium | E. coli | |||

| 4 | 0.8 | 3.1 | Potent activities against both S. aureus and E. faecium were reported with the lowest millimolar concentration of 0.8 mM. A significant anti-bacterial activity against S. aureus is noticed, with a corresponding MIC value of 0.8 mM, which is statistically comparable with the known antibiotics, linezolid and vancomycin. | [26,27] | |

| 5 | 0.8 | 3.1 | The complex had activities nearly the same as complex 4; this could be due to their structural similarities, with only variation on the side chain lactone ring. Its activities were also comparable to those of the positive control, having promising antibacterial applications. | [27] | |

| 6 | 0.8 | 3.1 | A probable antibacterial agent with promising activities both in vitro and in vivo | [27] | |

| 7 | 0.8 | 3.1 | The introduction of more electron donors, namely, Oxygen and nitrogen, to the complex helps to arrest and inhibit microbial colonies within the system. This complex has several active sites and hence reduces multidrug resistance |

[27] | |

| 8 | 0.8 | 6.1 | It is reported that this complex exhibited activities that aren’t different from the positive control; consequently, in vivo tests also affirm this in zebrafish tests. | [6,8] | |

| 9 | 0.002 | - | 0.023 | The complex showed activity twice as compared as the positive control. It also had no variation in its activities when MRSA and colistin-resistant E. coli strains were used. The toxicological reports affirm that the complex is safe and shows no hemolysis even up to a concentration of 300 µM, hence it can be used as a prospective antibiotic |

[25,26,27] |

| 10 | 0.01 | - | >64 | The reduced form of complex 9 showed a reduction in activity; it exhibited very low activity against the Gram-negative E. coli but showed better activity against the Gram-positive bacterium strain S. aureus. | [25,26,27] |

| 11 | 0.002 | - | >64 | The hydrogenated form of complex 10, a derivative of bis-quinoline, showed a noticeable activity against S. aureus at micromolar concentrations; however, poor activity was reported against the gram-negative bacterium strain of E. coli | [25,26,27,52] |

| Linezolid | 0.7 | - | - | [25,26,27,53,54] | |

| Vancomycin | 0.7 | - | - | [25,26,27,53,54] | |

| Polymyxin | 0.0005 | - | 0.0002 | - | [25,26,27,53,54] |

| Complexes | MIC (mg/ml) | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. lbicans | C. glabrata | C. krusei | C. parapsilosis | C. neoformans | ||

| 4 | 22.50 | 22.50 | 11.20 | 22.50 | - | [7,27,30] |

| 5 | 11.20 | 22.50 | 4.50 | 11.20 | - | [7,27,30] |

| 6 | 13.50 | 13.50 | 13.50 | <7.00 | - | [7,27,30] |

| 7 | 12.90 | 12.90 | 12.90 | 12.90 | - | [7,27,30] |

| 8 | 4.90 | 4.90 | 4.90 | 4.90 | - | [7,27,30] |

| 12 | 0.00062 | - | - | - | - | [7,27,30] |

| 13 | 0.032 | - | - | - | 0.032 | [26,59] |

| Complex | Antichagasic activities IC50 T. cruzi epimastigotes ± SD (μM) |

Selectivity index epimastigotes |

References |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 9.42 ± 1.53 | 0.34 | [34,35,36] |

| 17 | 8.43± 2.20 | 1.5 | [34,35,36] |

| 18 | 3.48 ± 0.98 | 0.89 | [34,35,36] |

| 19 | 8.48 ± 1.46 | 1.6 | [34,35,36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).