Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Agronomic Strategies

2.1. Canopy Management

2.1.1. Defoliation and Trimming

2.1.2. Shoot Topping

2.1.3. Winter Pruning

2.2. Pre-Harvest Irrigation

2.3. Managing Harvest Date

2.4. Other Techniques

2.4.1. Shading Nets

2.4.2. Anti-Transpirant Products

2.4.3. Application of Growth Regulators

| Strategy | Techniques (grape cv/wine) | Alcohol reduction (v/v) |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| defoliation | post veraison leaf removal (Sangiovese) | 0.6% | [57] |

| apical defoliation (Shiraz) | 0.2-0.7% | [65] | |

| pre-flowering defoliation (Trnjak) | 0.2% | [75] | |

| pruning | pruning severity modulation (Malbec) | 0.7% | [127] |

| shoot trimming (Grenache, Tempranillo) | 2% | [128] | |

| harvest date management | unripe grapes - cluster thinning (Grenache) | 3% | [106] |

| unripe grapes (Pinot and Tannat) | 0.5-3% | [102] | |

| shade | overhead shade (Shiraz) | 1% | [111] |

| anti-transpirant agent | pinolene application (Falanghina) | 0.9-1.6% | [115] |

| pinolene application (Sangiovese) | 1.0% | [117] | |

| pinolene application (Sauvignon) | 1.0% | [120] | |

| enzyme addition | GOX1 (Muscat-Ottonel) | 1.05% | [129] |

| GOX (Riesling) | 4.3% | [130] | |

| GOX preparation from A oryzae (Pinotage) | 0.7% | [131] | |

| encapsulated GOX-CAT (Verdejo) | 2.0% | [132] | |

| GOX-CAT (Verdejo) | 2-3% | [133] | |

| must dilution | late harvest (Shiraz) | 0.5-2.0% | [134] |

| three stages harvesting (Shiraz) | 1.6-2.1% | [135] | |

| filtration and membrane processing | must NF (Verdejo and Tinta de Toro) | 2-3% | [136] |

| must NF (Verdejo and Garnacha) | 1-2% | [137] | |

| must RO (Tinta Roriz, Syrah, Alicante Bouschet) | 1.5-10% | [138] |

3. Pre-Fermentative Strategies

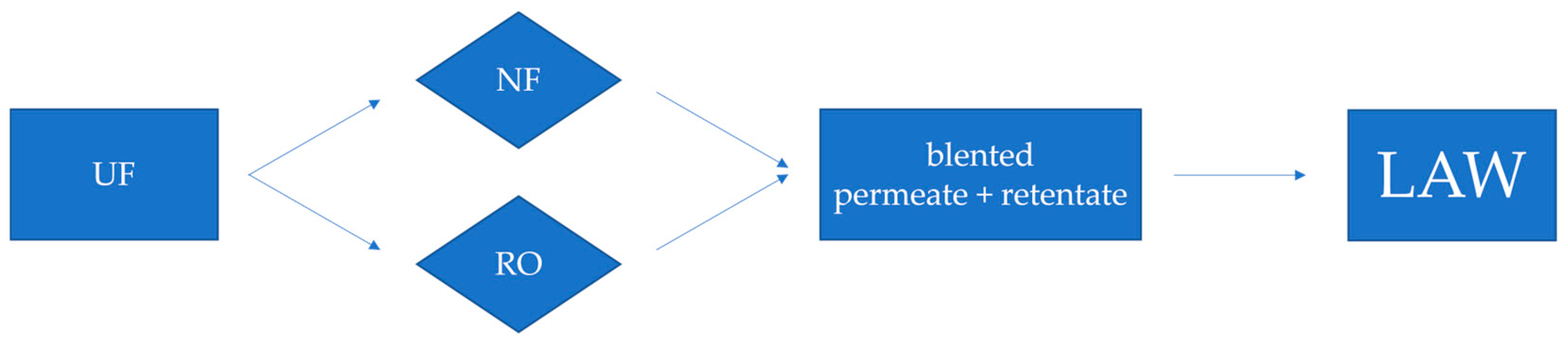

3.1. Filtration of Grape Must

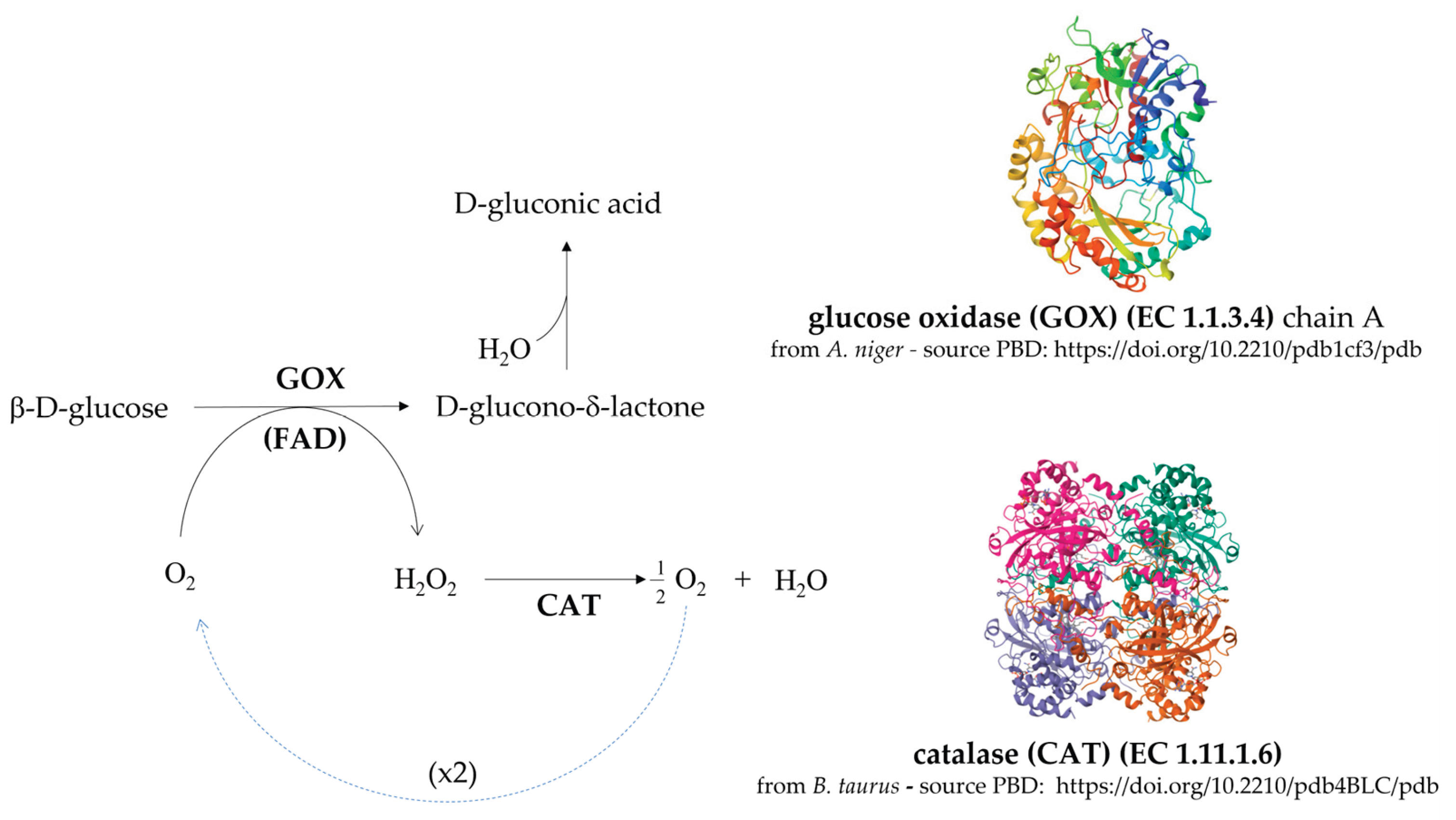

3.2. Addition of Enzymes

3.3. Grape Must Dilution

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fact.MR. https://www.factmr.com/report/4532/non-alcoholic-wine-market.

- IWSR. https://www.theiwsr.com/insight/the-innovations-shaping-future-low-alcohol-growth (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- IWSR. https://www.theiwsr.com/insight/key-statistics-the-no-alcohol-and-low-alcohol-market (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Núñez-Caraballo, A.; García-García, J.D.; Ilyina, A.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C.; Michelena-Álvarez, L.G.; Rodríguez-Cutiño, G.; Martínez-Hernández, J.L.; Aguilar, C.N. Alcoholic Beverages: Current Situation and Generalities of Anthropological Interest. In Processing and Sustainability of Beverages; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 37–72. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240072152 (accessed on 28 March 2025).

- Succi, M.; Coppola, F.; Testa, B.; Pellegrini, M.; Iorizzo, M. Alcohol or No Alcohol in Wine: Half a Century of Debate. Foods 2025, 14, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caluzzi, G.; MacLean, S.; Livingston, M.; Pennay, A. “No One Associates Alcohol with Being in Good Health”: Health and Wellbeing as Imperatives to Manage Alcohol Use for Young People. Sociol Health Illn 2021, 43, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filter, M.; Pentz, C.D. Dealcoholised Wine: Exploring the Purchasing Considerations of South African Generation Y Consumers. British Food Journal 2023, 125, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geffroy, O.; Podworny, M.; Brian, L.; Gosset, M.; Peter, M.; Cheriet, F. In a Fully Dealcoholised Chardonnay Wine, Sugar Is a Key Driver of Liking for Young Consumers. OENO One 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey, R.; Loose, S. State of the International Wine Markets in 2022: New Market Trends for Wines Require New Strategies. Wine Economics and Policy 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C.L.; Dolan, R.; Corsi, A.M.; Goodman, S.; Pearson, W. Exploring the Barriers and Triggers towards the Adoption of Low- and No-Alcohol (NOLO) Wines. Food Qual Prefer 2023, 110, 104932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, I.; Deroover, K.; Kavanagh, M.; Beckett, E.; Akanbi, T.; Pirinen, M.; Bucher, T. Australian Consumer Perception of Non-Alcoholic Beer, White Wine, Red Wine, and Spirits. Int J Gastron Food Sci 2024, 35, 100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucher, T.; Frey, E.; Wilczynska, M.; Deroover, K.; Dohle, S. Consumer Perception and Behaviour Related to Low-Alcohol Wine: Do People Overcompensate? Public Health Nutr 2020, 23, 1939–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHA63.13. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/wha63-13-global-strategy-to-reduce-the-harmful-use-of-alcohol.

- FDA. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/cpg-sec-510400-dealcoholized-wine-and-malt-beverages-labeling.

- Food Standards Australia New Zealand. https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/food-standards-code.

- Wine Australia. https://www.wineaustralia.com/getmedia/9303c879-1b6f-4649-b51d-3deb5e632286/low-alcohol-wine-guide-v2.pdf.

- EUR-Lex. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2013/1308/oj/eng.

- EUR-Lex IT. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/it/all/?uri=celex:32021r2117.

- OIV. https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1911/oiv-eco-432-2012-it.pdf.

- OIV. https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1912/oiv-eco-433-2012-it.pdf.

- OIV. https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/4927/oiv-eco-523-2016-en.pdf.

- OIV. https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1490/oiv-oeno-394a-2012-it.pdf.

- Ma, T.-Z.; Eudes Sam, F.; Zhang, B. Low-Alcohol and Nonalcoholic Wines: Production Methods, Compositional Changes, and Aroma Improvement. In Recent Advances in Grapes and Wine Production - New Perspectives for Quality Improvement; IntechOpen, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Testa, B.; Coppola, F.; Succi, M.; Iorizzo, M. Biotechnological Strategies for Ethanol Reduction in Wine. Fermentation 2025, 11, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, S.M.; Inês, A.; Vilela, A. Bio-Dealcoholization of Wines: Can Yeast Make Lighter Wines? Fermentation 2024, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.; Ricci, A.; Parpinello, G.P.; Versari, A. Dealcoholized Wine: A Scoping Review of Volatile and Non-Volatile Profiles, Consumer Perception, and Health Benefits. Food Bioproc Tech 2024, 17, 3525–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, F.E.; Ma, T.-Z.; Salifu, R.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.-M.; Zhang, B.; Han, S.-Y. Techniques for Dealcoholization of Wines: Their Impact on Wine Phenolic Composition, Volatile Composition, and Sensory Characteristics. Foods 2021, 10, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, L.; Russo, P.; Albanese, D.; Di Matteo, M. Production of Low-Alcohol Beverages: Current Status and Perspectives. In Food Processing for Increased Quality and Consumption; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 347–382. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Delrot, S.; Liang, Z. From Acidity to Sweetness: A Comprehensive Review of Carbon Accumulation in Grape Berries. Molecular Horticulture 2024, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drappier, J.; Thibon, C.; Rabot, A.; Geny-Denis, L. Relationship between Wine Composition and Temperature: Impact on Bordeaux Wine Typicity in the Context of Global Warming—Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerbi, V.; De Paolis, C. The Effects of Climate Change on Wine Composition and Winemaking Processes. Italian Journal of Food Science 2025, 37, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allamy, L.; Van Leeuwen, C.; Pons, A. Impact of Harvest Date on Aroma Compound Composition of Merlot and Cabernet-Sauvignon Must and Wine in a Context of Climate Change: A Focus on Cooked Fruit Molecular Markers. OENO One 2023, 57, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña-Rey, A.; González-Fernández, E.; Fernández-González, M.; Lorenzo, M.N.; Rodríguez-Rajo, F.J. Climate Change Impacts Assessment on Wine-Growing Bioclimatic Transition Areas. Agriculture 2020, 10, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienth, M.; Vigneron, N.; Darriet, P.; Sweetman, C.; Burbidge, C.; Bonghi, C.; Walker, R.P.; Famiani, F.; Castellarin, S.D. Grape Berry Secondary Metabolites and Their Modulation by Abiotic Factors in a Climate Change Scenario–A Review. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouxinol, M.I.; Martins, M.R.; Barroso, J.M.; Rato, A.E. Wine Grapes Ripening: A Review on Climate Effect and Analytical Approach to Increase Wine Quality. Applied Biosciences 2023, 2, 347–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubaro, F.; Pizzuto, R.; Raimo, G.; Paventi, G. A Novel Fluorimetric Method to Evaluate Red Wine Antioxidant Activity. Periodica Polytechnica Chemical Engineering 2019, 63, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, C.; Sgubin, G.; Bois, B.; Ollat, N.; Swingedouw, D.; Zito, S.; Gambetta, G.A. Climate Change Impacts and Adaptations of Wine Production. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2024, 5, 258–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogiers, S.Y.; Greer, D.H.; Liu, Y.; Baby, T.; Xiao, Z. Impact of Climate Change on Grape Berry Ripening: An Assessment of Adaptation Strategies for the Australian Vineyard. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Escobar, R.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E. Wine Polyphenol Content and Its Influence on Wine Quality and Properties: A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Zheng, W.; Martínez de Toda, F. Current Viticultural Techniques to Mitigate the Effects of Global Warming on Grape and Wine Quality: A Comprehensive Review. Food Research International 2021, 139, 109946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Gamboa, G.; Zheng, W.; Martínez de Toda, F. Strategies in Vineyard Establishment to Face Global Warming in Viticulture: A Mini Review. J Sci Food Agric 2021, 101, 1261–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirás-Avalos, J.M.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Grape Composition under Abiotic Constrains: Water Stress and Salinity. Front Plant Sci 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeide, J.; Frioni, T.; Ma, Z.; Stoll, M.; Poni, S.; Sabbatini, P. Early Leaf Removal as a Strategy to Improve Ripening and Lower Cluster Rot in Cool Climate (Vitis Vinifera L.) Pinot Grigio. Am J Enol Vitic 2020, 71, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, B.; Anli, E. Different Techniques for Reducing Alcohol Levels in Wine: A Review. BIO Web Conf 2014, 3, 02012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, E.; Salvi, L.; Paoli, F.; Fucile, M.; Mattii, G.B. Effects of Defoliation at Fruit Set on Vine Physiology and Berry Composition in Cabernet Sauvignon Grapevines. Plants 2021, 10, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, C.; Zenoni, S.; Fasoli, M.; Pezzotti, M.; Tornielli, G.B.; Filippetti, I. Selective Defoliation Affects Plant Growth, Fruit Transcriptional Ripening Program and Flavonoid Metabolism in Grapevine. BMC Plant Biol 2013, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Gatti, M.; Bernizzoni, F.; Civardi, S.; Bobeica, N.; Magnanini, E.; Palliotti, A. Late Leaf Removal Aimed at Delaying Ripening in Cv. Sangiovese: Physiological Assessment and Vine Performance. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2013, n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Gatti, M. Affecting Yield Components and Grape Composition through Manipulations of the Source-Sink Balance. Acta Hortic 2017, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessarin, P.; Ricci, A.; Baraldi, G.; Lombini, A.; Parpinello, G.P.; Rombolà, A.D. Beneficial Effects of Bunch-Zone Late Defoliations and Shoot Positioning on Berry Composition and Colour Components of Wines Undergoing Aging in an Organically-Managed and Rainfed Sangiovese Vineyard. OENO One 2022, 56, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, M.; Scheidweiler, M.; Blank, M.; Schultz, H.R. Possibilities to Reduce the Velocity of Berry Maturation through Various Leaf Area to Fruit Ratio Modifications in Vitis Vinifera L; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer, W.M.; Dokoozlian, N.K. Leaf Area/Crop Weight Ratios of Grapevines: Influence on Fruit Composition and Wine Quality. Am J Enol Vitic 2005, 56, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirković, D.; Matijašević, S.; Ćirković, B.; Laketić, D.; Jovanović, Z.; Kostić, B.; Bešlić, Z.; Sredojević, M.; Tešić, Ž.; Banjanac, T.; et al. Influence of Different Defoliation Timings on Quality and Phenolic Composition of the Wines Produced from the Serbian Autochthonous Variety Prokupac (Vitis Vinifera L.). Horticulturae 2022, 8, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Zurbano, P.; Santesteban, L.G.; Villa-Llop, A.; Loidi, M.; Peñalosa, C.; Musquiz, S.; Torres, N. Timing of Defoliation Affects Anthocyanin and Sugar Decoupling in Grenache Variety Growing in Warm Seasons. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2024, 125, 105729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioni, T.; Zhuang, S.; Palliotti, A.; Sivilotti, P.; Falchi, R.; Sabbatini, P. Leaf Removal and Cluster Thinning Efficiencies Are Highly Modulated by Environmental Conditions in Cool Climate Viticulture. Am J Enol Vitic 2017, 68, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanišević, D.; Kalajdžić, M.; Drenjančević, M.; Puškaš, V.; Korać, N. The Impact of Cluster Thinning and Leaf Removal Timing on the Grape Quality and Concentration of Monomeric Anthocyanins in Cabernet-Sauvignon and Probus (Vitis Vinifera L.) Wines. OENO One 2020, 54, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliotti, A.; Panara, F.; Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Sabbatini, P.; Howell, G.S.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S. Influence of Mechanical Postveraison Leaf Removal Apical to the Cluster Zone on Delay of Fruit Ripening in Sangiovese (Vitis Vinifera L.) Grapevines. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2013, n/a–n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A.; De Gianni, A.; Previtali, M.A.; Del Nobile, M.A.; Novello, V.; de Palma, L. Effects of Defoliation on Quality Attributes of Nero Di Troia (Vitis Vinifera L.) Grape and Wine. Food Research International 2015, 75, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćirković, D.; Matijašević, S.; Deletić, N.; Ćirković, B.; Gašić, U.; Sredojević, M.; Jovanović, Z.; Djurić, V.; Tešić, Ž. The Effect of Early and Late Defoliation on Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Prokupac Variety Grape Berries (Vitis Vinifera L.). Agronomy 2019, 9, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.; Jarvis, P.; Creasy, G.L.; Trought, M.C.T. Influence of Defoliation on Overwintering Carbohydrate Reserves, Return Bloom, and Yield of Mature Chardonnay Grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic 2005, 56, 386–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zufferey, V.; Murisier, F.; Vivin, P.; Belcher, S.; Lorenzini, F.; Spring, J.L.; Viret, O. Carbohydrate Reserves in Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L. ’Chasselas’): The Influence of the Leaf to Fruit Ratio; 2012; Vol. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Stoll, M.; Bischoff-Schaefer, M.; Lafontaine, M.; Tittmann, S.; Henschke, J. Impact of Various Leaf Area Modifications on Berry Maturation in Vitis Vinifera L. “Riesling.”. Acta Hortic 2013, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez de Toda, F.; Balda, P. Delaying Berry Ripening through Manipulating Leaf Area to Fruit Ratio. Vitis 2013, 52, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, M.K.; Creasy, G.L.; Hofmann, R.W.; Parker, A.K. Asynchronous Accumulation of Sugar and Phenolics in Grapevines Following Post-Veraison Leaf Removal. OENO One 2025, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, X.; Needs, S.; Liu, D.; Fuentes, S.; Howell, K. The Influence of Apical and Basal Defoliation on the Canopy Structure and Biochemical Composition of Vitis Vinifera Cv. Shiraz Grapes and Wine. Front Chem 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, A.K.; Hofmann, R.W.; van Leeuwen, C.; McLachlan, A.R.G.; Trought, M.C.T. Manipulating the Leaf Area to Fruit Mass Ratio Alters the Synchrony of Total Soluble Solids Accumulation and Titratable Acidity of Grape Berries. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2015, 21, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujundžić, T.; Rastija, V.; Šubarić, D.; Jukić, V.; Schwander, F.; Drenjančević, M. Effects of Defoliation Treatments of Babica Grape Variety(Vitis Vinifera L.) on Volatile Compounds Content in Wine. Molecules 2022, 27, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, D.; Vilanova, M.; Gamero, E.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Talaverano, M.I.; Uriarte, D.; Valdés, M.E. Effects of Preflowering Leaf Removal on Phenolic Composition of Tempranillo in the Semiarid Terroir of Western Spain. Am J Enol Vitic 2015, 66, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osrečak, M.; Karoglan, M.; Kozina, B.; Preiner, D. Influence of Leaf Removal and Reflective Mulch on Phenolic Composition of White Wines. OENO One 2015, 49, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Casalini, L.; Bernizzoni, F.; Civardi, S.; Intrieri, C. Effects of Early Defoliation on Shoot Photosynthesis, Yield Components, and Grape Composition. Am J Enol Vitic 2006, 57, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdenal, T.; ZUFFEREY, V.; Dienes-Nagy, A.; Gindro, K.; Belcher, S.; Lorenzini, F.; Rösti, J.; Koestel, C.; Spring, J.-L.; Viret, O. Pre-Flowering Defoliation Affects Berry Structure and Enhances Wine Sensory Parameters. OENO One 2017, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilanova, M.; Diago, M.P.; Genisheva, Z.; Oliveira, J.M.; Tardaguila, J. Early Leaf Removal Impact on Volatile Composition of Tempranillo Wines. J Sci Food Agric 2012, 92, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanari, V.; Lattanzi, T.; Borghesi, L.; Silvestroni, O.; Palliotti, A. Post-Veraison Mechanical Leaf Removal Delays Berry Ripening on “Sangiovese” and “Montepulciano” Grapevines. Acta Hortic 2013, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesa, I.; Caccavello, G.; Basile, B.; Merli, M.C.; Poni, S.; Chirivella, C.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Delaying Berry Ripening of Bobal and Tempranillo Grapevines by Late Leaf Removal in a Semi-Arid and Temperate-Warm Climate under Different Water Regimes. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2019, 25, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucalo, A.; Budić-Leto, I.; Lukšić, K.; Maletić, E.; Zdunić, G. Early Defoliation Techniques Enhance Yield Components, Grape and Wine Composition of Cv. Trnjak (Vitis Vinifera L.) in Dalmatian Hinterland Wine Region. Plants 2021, 10, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessarin, P.; Parpinello, G.P.; Rombolà, A.D. Physiological and Enological Implications of Postveraison Trimming in an Organically-Managed Sangiovese Vineyard. Am J Enol Vitic 2018, 69, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Sacks, G.L.; Lerch, S.D.; Vanden Heuvel, J.E. Impact of Shoot and Cluster Thinning on Yield, Fruit Composition, and Wine Quality of Corot Noir. Am J Enol Vitic 2012, 63, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poni, S.; Zamboni, M.; Vercesi, A.; Garavani, A.; Gatti, M. Effects of Early Shoot Trimming of Varying Severity on Single High-Wire Trellised Pinot Noir Grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic 2014, 65, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippetti, I.; Movahed, N.; Allegro, G.; Valentini, G.; Pastore, C.; Colucci, E.; Intrieri, C. Effect of Post-Veraison Source Limitation on the Accumulation of Sugar, Anthocyanins and Seed Tannins in V Itis Vinifera Cv. Sangiovese Berries. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2015, 21, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentini, G.; Allegro, G.; Pastore, C.; Colucci, E.; Filippetti, I. Post-veraison Trimming Slow down Sugar Accumulation without Modifying Phenolic Ripening in Sangiovese Vines. J Sci Food Agric 2019, 99, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toda, F.M.; Sancha, J.C.; Zheng, W.; Balda, P. Leaf Area Reduction by Trimming, a Growing Technique to Restore the Anthocyanins: Sugars Ratio Decoupled by the Warming Climate; 2014; Vol. 53. [Google Scholar]

- Santesteban, L.G.; Miranda, C.; Urrestarazu, J.; Loidi, M.; Royo, J.B. Severe Trimming and Enhanced Competition of Laterals as a Tool to Delay Ripening in Tempranillo Vineyards under Semiarid Conditions. OENO One 2017, 51, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubola, M.; Persic, M.; Rossi, S.; Bestulić, E.; Zdunić, G.; Plavša, T.; Radeka, S. Severe Shoot Trimming and Crop Size as Tools to Modulate Cv. Merlot Berry Composition. Plants 2022, 11, 3571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.-C.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, C.-F.; Chen, W.; Li, S.-D.; He, F.; Duan, C.-Q.; Wang, J. Manipulating the Severe Shoot Topping Delays the Harvest Date and Modifies the Flavor Composition of Cabernet Sauvignon Wines in a Semi-Arid Climate. Food Chem 2023, 405, 135008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.-C.; Tian, M.-B.; Shi, N.; Han, X.; Li, H.-Q.; Cheng, C.-F.; Chen, W.; Li, S.-D.; He, F.; Duan, C.-Q.; et al. Severe Shoot Topping Slows down Berry Sugar Accumulation Rate, Alters the Vine Growth and Photosynthetic Capacity, and Influences the Flavoromics of Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes in a Semi-Arid Region. European Journal of Agronomy 2023, 145, 126775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Martínez-Lüscher, J.; Porte, E.; Yu, R.; Kaan Kurtural, S. Impacts of Leaf Removal and Shoot Thinning on Cumulative Daily Light Intensity and Thermal Time and Their Cascading Effects of Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Berry and Wine Chemistry in Warm Climates. Food Chem 2021, 343, 128447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioni, T.; Tombesi, S.; Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Bellincontro, A.; Sabbatini, P.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S.; Palliotti, A. Postbudburst Spur Pruning Reduces Yield and Delays Fruit Sugar Accumulation in Sangiovese in Central Italy. Am J Enol Vitic 2016, 67, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moreno, A.; Sanz, F.; Yeves, A.; Gil-Muñoz, R.; Martínez, V.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Buesa, I. Forcing Bud Growth by Double-Pruning as a Technique to Improve Grape Composition of Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Tempranillo in a Semi-Arid Mediterranean Climate. Sci Hortic 2019, 256, 108614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balint, G.; Reynolds, A.G. Effect of Different Irrigation Strategies on Vine Physiology, Yield, Grape Composition and Sensory Profiles of Vitis vinifera L. Cabernet-Sauvignon in a Cool Climate Area. OENO One 2014, 48, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirás-Avalos, J.; Araujo, E. Optimization of Vineyard Water Management: Challenges, Strategies, and Perspectives. Water 2021, 13, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliotti, A.; Tombesi, S.; Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S. Changes in Vineyard Establishment and Canopy Management Urged by Earlier Climate-Related Grape Ripening: A Review. Sci Hortic 2014, 178, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, M.A.; Villanueva, M.J.; Lissarrague, J.R. Effect of Irrigation on Changes in Berry Composition of Tempranillo During Maturation. Sugars, Organic Acids, and Mineral Elements. Am J Enol Vitic 1999, 50, 418–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intrigliolo, D.S.; Castel, J.R. Effects of Irrigation on the Performance of Grapevine Cv. Tempranillo in Requena, Spain. Am J Enol Vitic 2008, 59, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizama, V.; Pérez-Álvarez, E.P.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Chirivella, C.; Álvarez, I.; García-Esparza, M.J. Effects of the Irrigation Regimes on Grapevine Cv. Bobal in a Mediterranean Climate: II. Wine, Skins, Seeds, and Grape Aromatic Composition. Agric Water Manag 2021, 256, 107078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, R.; Blackman, J.W.; Antalick, G.; Torley, P.J.; Rogiers, S.Y.; Schmidtke, L.M. Volatile and Sensory Profiling of Shiraz Wine in Response to Alcohol Management: Comparison of Harvest Timing versus Technological Approaches. Food Research International 2018, 109, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Moreno, A.; Martínez-Pérez, P.; Bautista-Ortín, A.B.; Gómez-Plaza, E. Use of Unripe Grape Wine as a Tool for Reducing Alcohol Content and Improving the Quality and Oenological Characteristics of Red Wines. OENO One 2023, 57, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Destrac-Irvine, A.; Gowdy, M.; Farris, L.; Pieri, P.; Marolleau, L.; Gambetta, G.A. An Operational Model for Capturing Grape Ripening Dynamics to Support Harvest Decisions. OENO One 2023, 57, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wu, J.; Meng, J.; Shi, P.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, X. Harvesting at the Right Time: Maturity and Its Effects on the Aromatic Characteristics of Cabernet Sauvignon Wine. Molecules 2019, 24, 2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovo, B.; Nadai, C.; Vendramini, C.; Fernandes Lemos Junior, W.J.; Carlot, M.; Skelin, A.; Giacomini, A.; Corich, V. Aptitude of Saccharomyces Yeasts to Ferment Unripe Grapes Harvested during Cluster Thinning for Reducing Alcohol Content of Wine. Int J Food Microbiol 2016, 236, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindon, K.; Varela, C.; Kennedy, J.; Holt, H.; Herderich, M. Relationships between Harvest Time and Wine Composition in Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Cabernet Sauvignon 1. Grape and Wine Chemistry. Food Chem 2013, 138, 1696–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindon, K.; Holt, H.; Williamson, P.O.; Varela, C.; Herderich, M.; Francis, I.L. Relationships between Harvest Time and Wine Composition in Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Cabernet Sauvignon 2. Wine Sensory Properties and Consumer Preference. Food Chem 2014, 154, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccardo, D.; Favre, G.; Pascual, O.; Canals, J.M.; Zamora, F.; González-Neves, G. Influence of the Use of Unripe Grapes to Reduce Ethanol Content and PH on the Color, Polyphenol and Polysaccharide Composition of Conventional and Hot Macerated Pinot Noir and Tannat Wines. European Food Research and Technology 2019, 245, 1321–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelezki, O.J.; Smith, P.A.; Hranilovic, A.; Bindon, K.A.; Jeffery, D.W. Comparison of Consecutive Harvests versus Blending Treatments to Produce Lower Alcohol Wines from Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes: Impact on Polysaccharide and Tannin Content and Composition. Food Chem 2018, 244, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelezki, O.J.; Antalick, G.; Šuklje, K.; Jeffery, D.W. Pre-Fermentation Approaches to Producing Lower Alcohol Wines from Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz: Implications for Wine Quality Based on Chemical and Sensory Analysis. Food Chem 2020, 309, 125698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teslić, N.; Patrignani, F.; Ghidotti, M.; Parpinello, G.P.; Ricci, A.; Tofalo, R.; Lanciotti, R.; Versari, A. Utilization of ‘Early Green Harvest’ and Non-Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Yeasts as a Combined Approach to Face Climate Change in Winemaking. European Food Research and Technology 2018, 244, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontoudakis, N.; Esteruelas, M.; Fort, F.; Canals, J.M.; Zamora, F. Use of Unripe Grapes Harvested during Cluster Thinning as a Method for Reducing Alcohol Content and PH of Wine. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2011, 17, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanzone, M.; Sari, S.E.; Mestre, M.V.; Catania, A.A.; Catelén, M.J.; Jofré, V.P.; González-Miret, M.L.; Combina, M.; Vazquez, F.; Maturano, Y.P. Combination of Pre-Fermentative and Fermentative Strategies to Produce Malbec Wines of Lower Alcohol and PH, with High Chemical and Sensory Quality. OENO One 2020, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelezki, O.J.; Šuklje, K.; Boss, P.K.; Jeffery, D.W. Comparison of Consecutive Harvests versus Blending Treatments to Produce Lower Alcohol Wines from Cabernet Sauvignon Grapes: Impact on Wine Volatile Composition and Sensory Properties. Food Chem 2018, 259, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallotti, L.; Silvestroni, O.; Dottori, E.; Lattanzi, T.; Lanari, V. Effects of Shading Nets as a Form of Adaptation to Climate Change on Grapes Production: A Review. OENO One 2023, 57, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjitha, K.; Shivashankar, S.; Prakash, G.S.; Sampathkumar, P.; Roy, T.K.; Suresh, E.R. Effect of Vineyard Shading on the Composition, Sensory Quality and Volatile Flavours of Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Pinot Noir Wines from Mild Tropics. Journal of Applied Horticulture 2015, 17, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravia, L.; Collins, C.; Petrie, P.R.; Tyerman, S.D. Application of Shade Treatments during Shiraz Berry Ripening to Reduce the Impact of High Temperature. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2016, 22, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau, S.M.; Baumes, R.L.; Razungles, A.J. Effects of Vine or Bunch Shading on the Glycosylated Flavor Precursors in Grapes of Vitis Vinifera L. Cv. Syrah. J Agric Food Chem 2000, 48, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagay, V.; Reynolds, A.G.; Fisher, K.H. The Influence of Bird Netting on Yield and Fruit, Juice, and Wine Composition of Vitis Vinifera L. OENO One 2013, 47, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, F.K.; Sabir, A.; Unal, S. Maintaining the Grape Quality on Organically Grown Vines (Vitis Vinifera L.) at Vineyard Condition under Temperate Climate of Konya Province. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2021, 63, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillante, L.; Belfiore, N.; Gaiotti, F.; Lovat, L.; Sansone, L.; Poni, S.; Tomasi, D. Comparing Kaolin and Pinolene to Improve Sustainable Grapevine Production during Drought. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0156631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Vaio, C.; Villano, C.; Lisanti, M.T.; Marallo, N.; Cirillo, A.; Di Lorenzo, R.; Pisciotta, A. Application of Anti-Transpirant to Control Sugar Accumulation in Grape Berries and Alcohol Degree in Wines Obtained from Thinned and Unthinned Vines of Cv. Falanghina (Vitis Vinifera L.). Agronomy 2020, 10, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliotti, A.; Panara, F.; Famiani, F.; Sabbatini, P.; Howell, G.S.; Silvestroni, O.; Poni, S. Postveraison Application of Antitranspirant Di-1-p-Menthene to Control Sugar Accumulation in Sangiovese Grapevines. Am J Enol Vitic 2013, 64, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.; Galbignani, M.; Garavani, A.; Bernizzoni, F.; Tombesi, S.; Palliotti, A.; Poni, S. Manipulation of Ripening via Antitranspirants in Cv. Barbera (Vitis Vinifera L.). Aust J Grape Wine Res 2016, 22, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreotti, C.; Benyahia, F.; Petrillo, M.; Lucchetta, V.; Volta, B.; Cameron, K.; Targetti, G.; Tagliavini, M.; Zanotelli, D. Comparing Defoliation and Canopy Sprays to Delay Ripening of Sauvignon Blanc Grapes. Sci Hortic 2024, 326, 112736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucchetta, V.; Volta, B.; Tononi, M.; Zanotelli, D.; Andreotti, C. Effects of Pre-Harvest Techniques in the Control of Berry Ripening in Grapevine Cv. Sauvignon Blanc. BIO Web Conf 2019, 13, 04016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yao, H.; Chen, K.; Ju, Y.; Min, Z.; Sun, X.; Cheng, Z.; Liao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Fang, Y. Effect of Foliar Application of Fulvic Acid Antitranspirant on Sugar Accumulation, Phenolic Profiles and Aroma Qualities of Cabernet Sauvignon and Riesling Grapes and Wines. Food Chem 2021, 351, 129308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanthakumar, S.; Manju, V.; Kumar, V.A. Influence of Plant Growth Regulators to Improve the Colour and Sugar Content of Grapes (Vitis Vinifera L.). Cv. Red Globe. International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 2021, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottcher, C.; Harvey, K.; Forde, C.G.; Boss, P.K.; Davies, C. Auxin Treatment of Pre-Veraison Grape (Vitis Vinifera L.) Berries Both Delays Ripening and Increases the Synchronicity of Sugar Accumulation. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2011, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böttcher, C.; Johnson, T.E.; Burbidge, C.A.; Nicholson, E.L.; Boss, P.K.; Maffei, S.M.; Bastian, S.E.P.; Davies, C. Use of Auxin to Delay Ripening: Sensory and Biochemical Evaluation of Cabernet Sauvignon and Shiraz. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2022, 28, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Santo, S.; Tucker, M.R.; Tan, H.-T.; Burbidge, C.A.; Fasoli, M.; Böttcher, C.; Boss, P.K.; Pezzotti, M.; Davies, C. Auxin Treatment of Grapevine (Vitis Vinifera L.) Berries Delays Ripening Onset by Inhibiting Cell Expansion. Plant Mol Biol 2020, 103, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouthu, S.; Deluc, L.G. Timing of Ripening Initiation in Grape Berries and Its Relationship to Seed Content and Pericarp Auxin Levels. BMC Plant Biol 2015, 15, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, C.V.; Ahumada, G.E.; Fontana, A.R.; Segura, D.; Belmonte, M.J.; Giordano, C.V. Impact of Pruning Severity on the Performance of Malbec Single-High-Wire Vineyards in a Hot and Arid Region. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2025, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez de Toda, F.M.; Sancha, J.C.; Balda, P. Reducing the Sugar and PH of the Grape (Vitis Vinifera L. Cvs. ‘Grenache’ and ‘Tempranillo’) Through a Single Shoot Trimming. South African Journal of Enology and Viticulture 2016, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filimon, V.R.; Filimon, R.M.; Pașa, R.; Nechita, A.; Damian, D. Enzymatic Reduction of Glucose from Grape Must Using Glucose Oxidase as a Strategy for the Production of Low-Alcohol Wine. Acta Hortic 2025, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G.J.; Heatherbell, D.A.; Barnes, M.F. The Production of Reduced-Alcohol Wine Using Glucose Oxidase Treated Juice. Part I. Composition. Am J Enol Vitic 1999, 50, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biyela, B.N.E.; du Toit, W.J.; Divol, B.; Malherbe, D.F.; van Rensburg, P. The Production of Reduced-Alcohol Wines Using Gluzyme Mono® 10.000 BG-Treated Grape Juice. South African Journal of Enology & Viticulture 2016, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del-Bosque, D.; Vila-Crespo, J.; Ruipérez, V.; Fernández-Fernández, E.; Rodríguez-Nogales, J.M. Entrapment of Glucose Oxidase and Catalase in Silica–Calcium–Alginate Hydrogel Reduces the Release of Gluconic Acid in Must. Gels 2023, 9, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangas, R.; González, M.R.; Martín, P.; Rodríguez-Nogales, J.M. Impact of Glucose Oxidase Treatment in High Sugar and PH Musts on Volatile Composition of White Wines. LWT 2023, 184, 114975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelezki, O.J.; Deloire, A.; Jeffery, D.W. Substitution or Dilution? Assessing Pre-Fermentative Water Implementation to Produce Lower Alcohol Shiraz Wines. Molecules 2020, 25, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, B.; Petrie, P.R.; Smith, P.A.; Bindon, K.A. Comparison of Water Addition and Early-harvest Strategies to Decrease Alcohol Concentration in Vitis Vinifera Cv. Shiraz Wine: Impact on Wine Phenolics, Tannin Composition and Colour Properties. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2020, 26, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, N.; Perez-Magariño, S.; Ortega-Heras, M.; González-Huerta, C.; Mihnea, M.; González-Sanjosé, M.L.; Palacio, L.; Prádanos, P.; Hernández, A. Sugar Reduction in White and Red Musts with Nanofiltration Membranes. Desalination Water Treat 2011, 27, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, C.M.; Fernández-Fernández, E.; Palacio, L.; Hernández, A.; Prádanos, P. Alcohol Reduction in Red and White Wines by Nanofiltration of Musts before Fermentation. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2015, 96, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, H.; de Pinho, M.N.; Guiomar, A.; Geraldes, V. Membrane Processing of Grape Must for Control of the Alcohol Content in Fermented Beverages. Journal of Membrane Science and Research 2017, 3, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pati, S.; La Notte, D.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Cicco, G.; Esti, M. Reverse Osmosis and Nanofiltration Membranes for the Improvement of Must Quality. European Food Research and Technology 2014, 239, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versari, A.; Ferrarini, R.; Parpinello, G.P.; Galassi, S. Concentration of Grape Must by Nanofiltration Membranes. Food and Bioproducts Processing 2003, 81, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, N.; Perez-Magariño, S.; Ortega-Heras, M.; González-Huerta, C.; Mihnea, M.; González-Sanjosé, M.L.; Palacio, L.; Prádanos, P.; Hernández, A. Sugar Reduction in Musts with Nanofiltration Membranes to Obtain Low Alcohol-Content Wines. Sep Purif Technol 2010, 76, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C.; Dry, P.R.; Kutyna, D.R.; Francis, I.L.; Henschke, P.A.; Curtin, C.D.; Chambers, P.J. Strategies for Reducing Alcohol Concentration in Wine. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2015, 21, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihnea, M.; González-SanJosé, M.L.; Ortega-Heras, M.; Pérez-Magariño, S.; García-Martin, N.; Palacio, L.; Prádanos, P.; Hernández, A. Impact of Must Sugar Reduction by Membrane Applications on Volatile Composition of Verdejo Wines. J Agric Food Chem 2012, 60, 7050–7063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, C.; Palacio, L.; Carmona, F.J.; Hernández, A.; Prádanos, P. Influence of Low and High Molecular Weight Compounds on the Permeate Flux Decline in Nanofiltration of Red Grape Must. Desalination 2013, 315, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Török, D.F. Review: Polyphenols and Sensory Traits in Reverse Osmosis NoLo Wines. Journal of Knowledge Learning and Science Technology 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, M.; Christmann, M. Alcohol Reduction by Physical Methods. In Advances in Grape and Wine Biotechnology; IntechOpen, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Röcker, J.; Schmitt, M.; Pasch, L.; Ebert, K.; Grossmann, M. The Use of Glucose Oxidase and Catalase for the Enzymatic Reduction of the Potential Ethanol Content in Wine. Food Chem 2016, 210, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, P.; Espinoza, K.; Ramirez, C.; Franco, W.; Urtubia, A. Technical Feasibility of Glucose Oxidase as a Prefermentation Treatment for Lowering the Alcoholic Degree of Red Wine. Am J Enol Vitic 2017, 68, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatami, S.H.; Vakili, O.; Ahmadi, N.; Soltani Fard, E.; Mousavi, P.; Khalvati, B.; Maleksabet, A.; Savardashtaki, A.; Taheri-Anganeh, M.; Movahedpour, A. Glucose Oxidase: Applications, Sources, and Recombinant Production. Biotechnol Appl Biochem 2022, 69, 939–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G.J.; Heatherbell, D.A.; Barnes, M.F. Optimising Glucose Conversion in the Production of Reduced Alcohol Wine Using Glucose Oxidase. Food Research International 1998, 31, 685–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G.J.; Heatherbell, D.A.; Barnes, M.F. The Production of Reduced-Alcohol Wine Using Glucose Oxidase-Treated Juice. Part III. Sensory. Am J Enol Vitic 1999, 50, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CFR 24.246. https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/27/24.246 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- OIV. https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/4310/f-coei-1-prenzy.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Ramos-Ruiz, R.; Poirot, E.; Flores-Mosquera, M. GABA, a Non-Protein Amino Acid Ubiquitous in Food Matrices. Cogent Food Agric 2018, 4, 1–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botezatu, A.; Essary, A.; Bajec, M. Glucose Oxidase in Conjunction with Catalase—An Effective System of Wine PH Management in Red Wine. Am J Enol Vitic 2023, 74, 0740004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolle, L.; Englezos, V.; Torchio, F.; Cravero, F.; Río Segade, S.; Rantsiou, K.; Giacosa, S.; Gambuti, A.; Gerbi, V.; Cocolin, L. Alcohol Reduction in Red Wines by Technological and Microbiological Approaches: A Comparative Study. Aust J Grape Wine Res 2018, 24, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIV. https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1438/oiv-oeno-439-2012-en.pdf.

- OIV. https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1502/oiv-oeno-450b-2012-it.pdf.

- EUR-Lex. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2013/1308/oj/eng.

- CFR 24.176. https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/27/24.176.

- FSANZ. https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/sites/default/files/food-standards-code/applications/documents/a1119%20addition%20of%20water%20to%20wine%20appr.pdf.

- Gardner, J.M.; Walker, M.E.; Boss, P.K.; Jiranek, V. The Effect of Grape Juice Dilution on Oenological Fermentation 2020.

- Xynas, B.; Barnes, C.; Howell, K. Amending High Sugar in V. Vinifera Cv. Shiraz Wine Must by Pre-Fermentation Water Treatments Results in Subtle Sensory Differences for Naïve Wine Consumers. OENO One 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).