Submitted:

20 June 2025

Posted:

27 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Development of Residual Stress Within Cast Irons

1.3. Hole-Drilling Measurement

2. Material and Methods

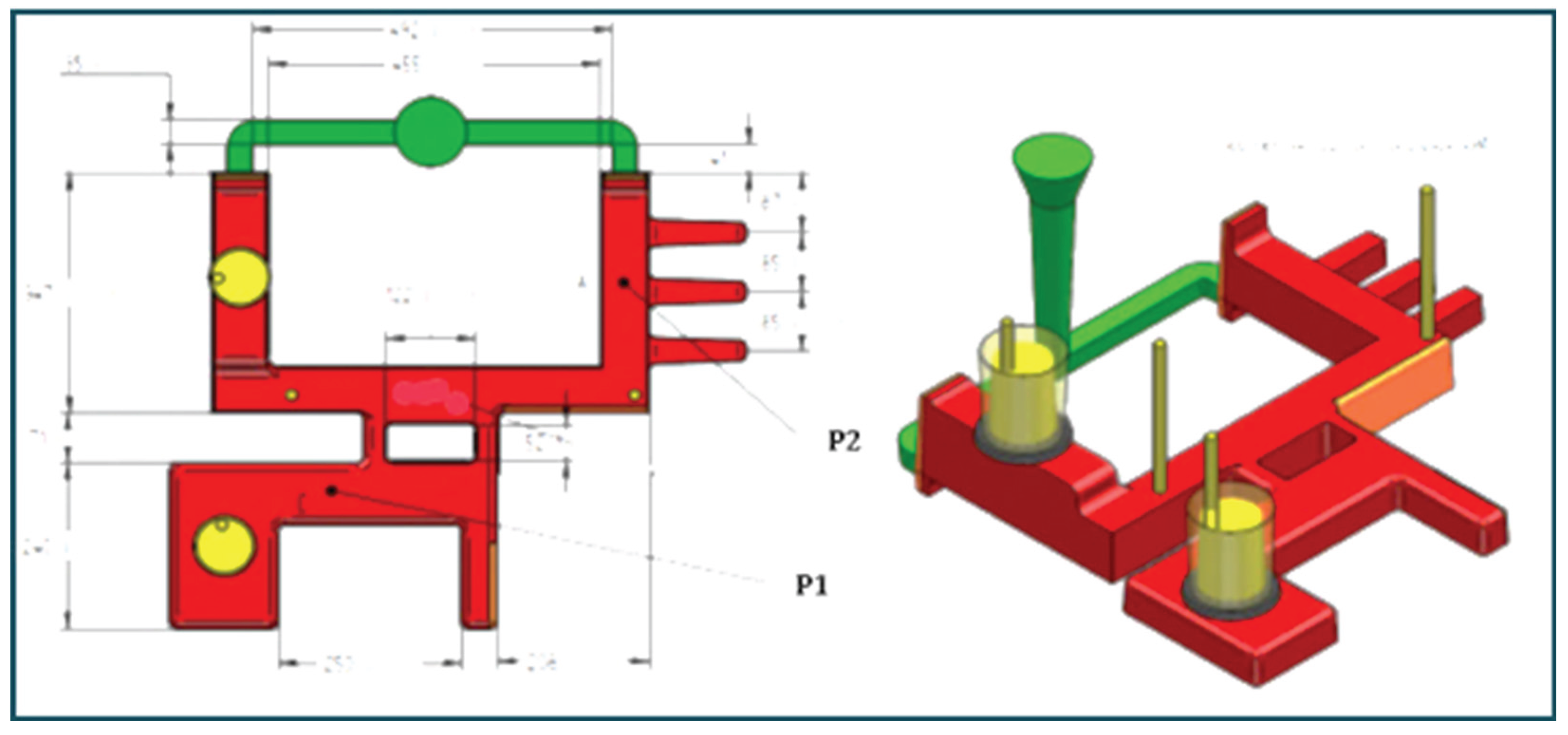

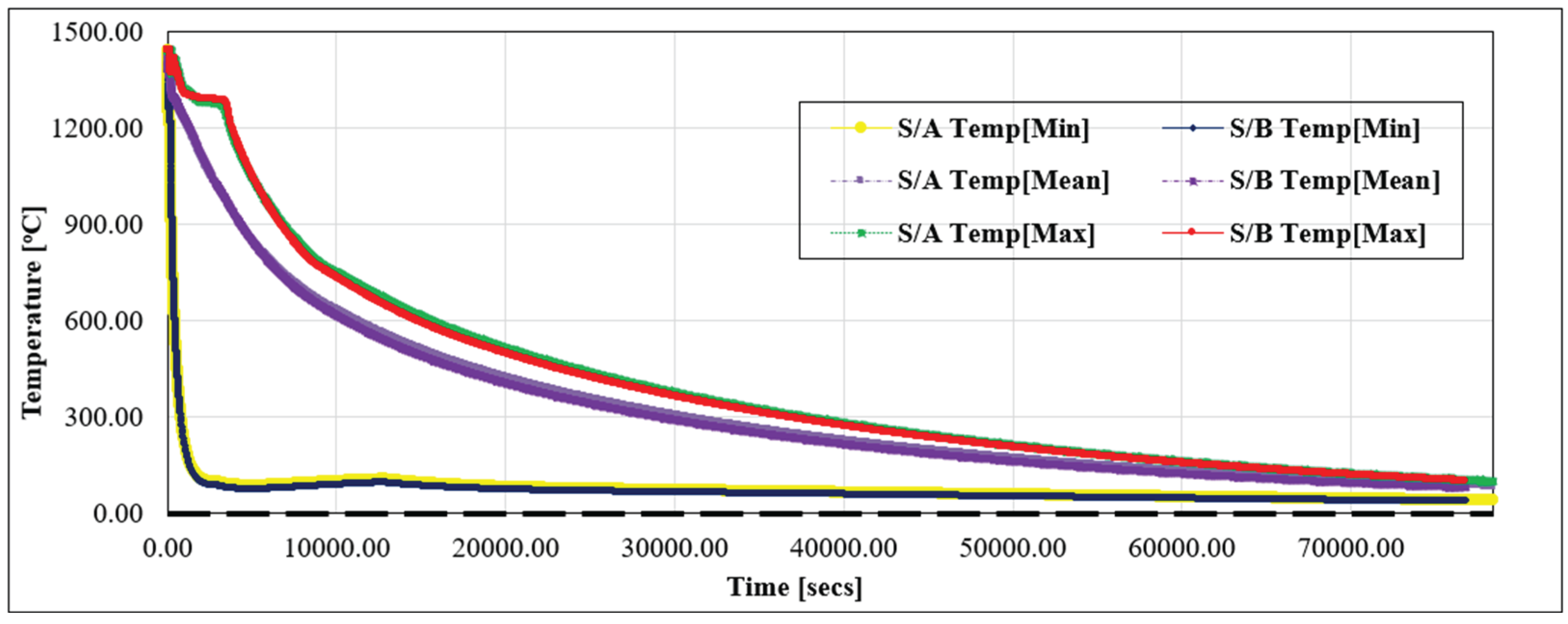

2.1. Melting and Casting Processes

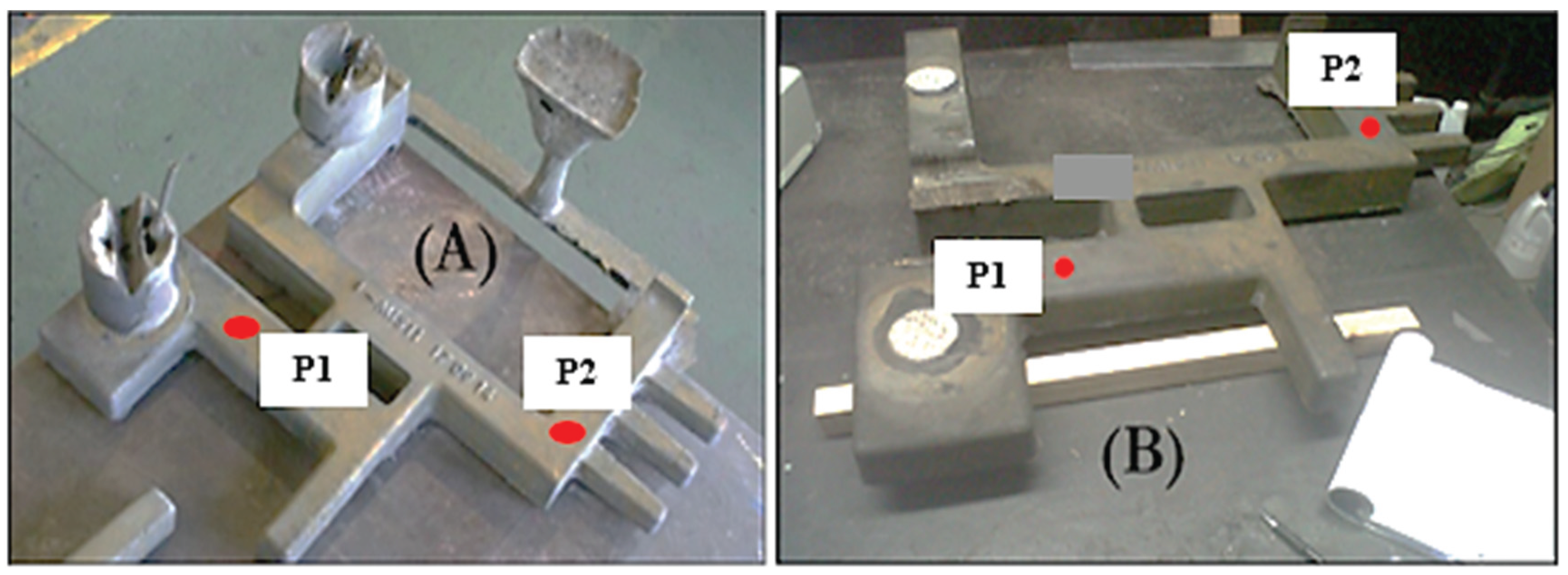

2.2. Experiential Procedures

2.2.1. Chemical Evaluation

2.2.2. Microstructural Evaluation

2.2.3. Hardness Evaluation

2.2.4. Residual Stress Measurements Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Analysis

3.2. Microstructural Analysis

3.3. Hardness Analysis

3.4. Residual Stress Analysis

3.4.1. Sample-A (S/A Alloy)

3.4.1.1. Residual Stresses at P1 Under GCW and NCW Conditions in S/A

3.4.1.2. Residual Stresses at P2 Under GCW and NCW Conditions in S/A

3.4.1.3. Residual Stresses Under GCW Conditions at P1 and P2 in S/A

3.4.1.4. Residual Stresses Under NCW Conditions at P1 and P2 in S/A

3.4.2. Sample-B (S/B Alloy)

3.4.2.1. Residual Stresses at P1 Under GCW and NCW Conditions in S/B

3.4.2.2. Residual Stresses at P2 Under GCW and NCW Conditions in S/B

3.4.2.3. Residual Stresses Under GCW Conditions at P1 and P2 in S/B

3.4.2.4. Residual Stresses Under NCW Conditions at P1 and P2 in S/B

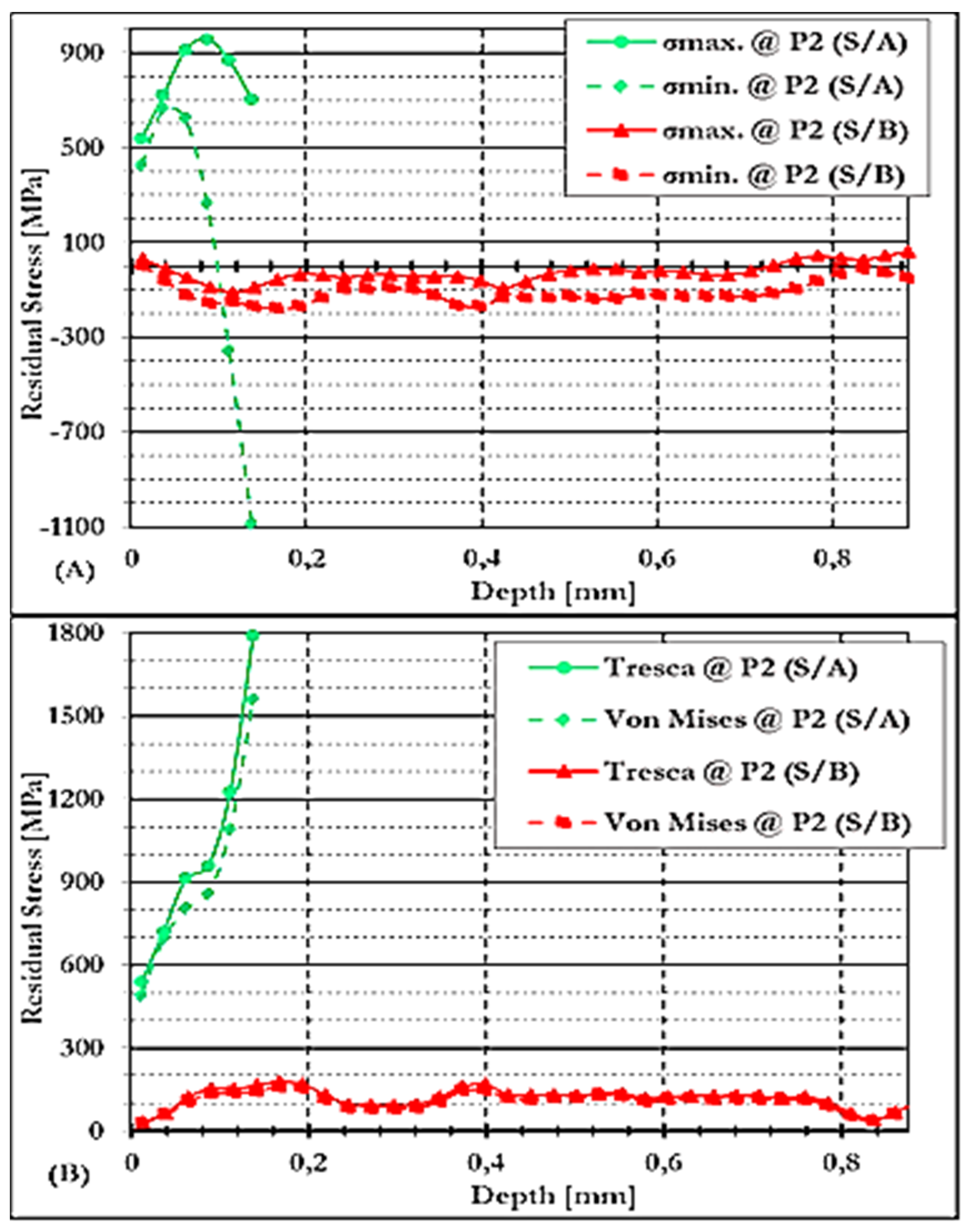

3.4.3. Residual Stresses on S/A and S/B

3.4.3.1. Residual Stresses at P1 of GCW Conditions on S/A and S/B

3.4.3.2. Residual Stresses at P1 of NCW Conditions on S/A and S/B

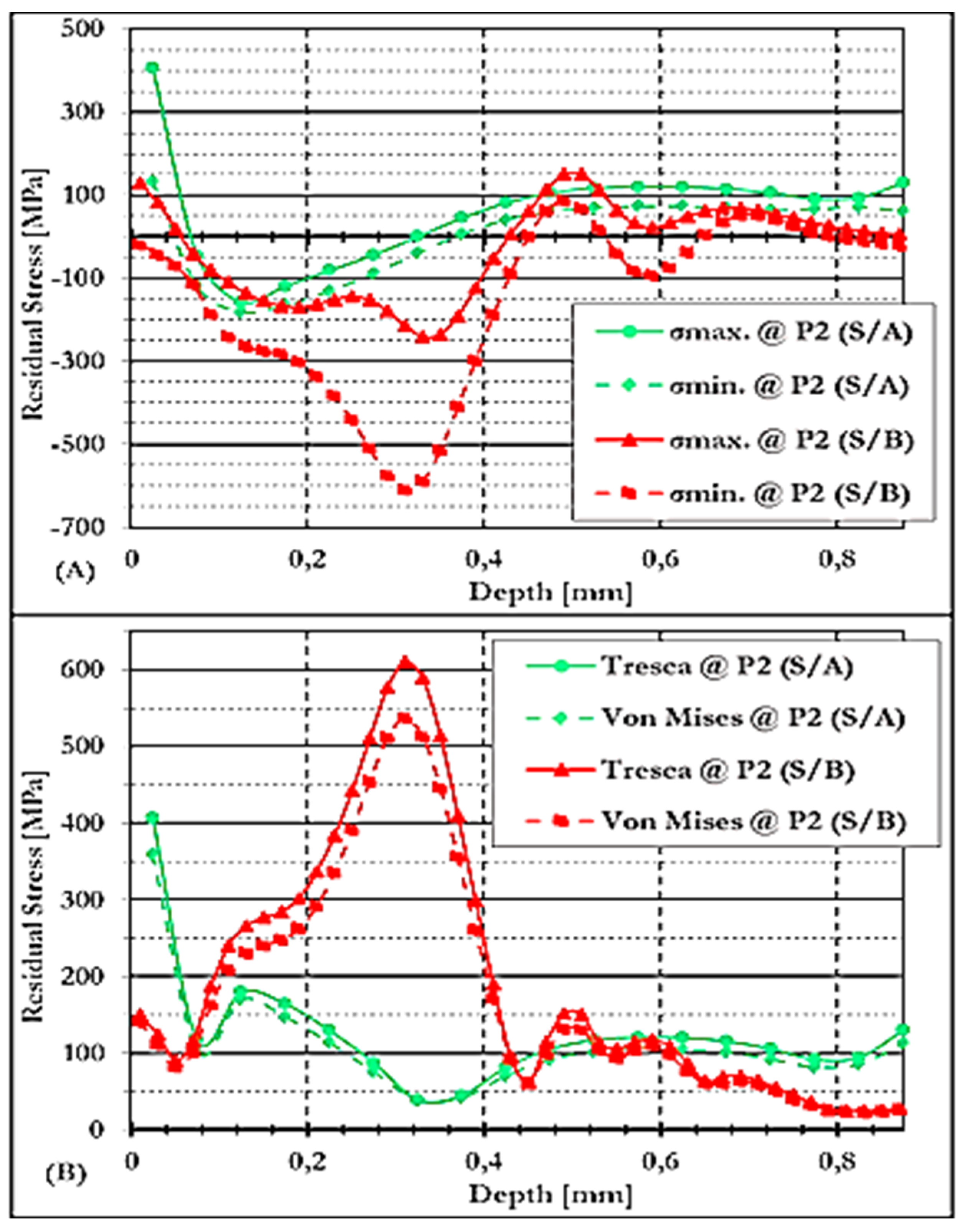

3.4.3.3. Residual Stresses at P2 of GCW Conditions on S/A and S/B

3.4.3.4. Residual Stresses at P2 of NCW Conditions on S/A and S/B

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Higher casting shakeout temperatures encourage optimum hardness values.

- (2)

- Non-uniform RS distribution is normally detected.

- (3)

- Thinner casting section thickness led to minimum magnitudes of RSs as compared to thicker section thickness, which introduced optimum RS magnitudes.

- (4)

- Separating and/or removing junk material from NCW led to a modification of RS state.

- (5)

- RSs within NCW are forever in the opposite direction of the GCW RS distribution.

- (6)

- Castings shakeout at elevated temperatures led to advanced tensile RSs.

- (7)

- Shakeout at elevated temperatures led to steady compressive RSs on NCW.

5. Future Work

Acknowledgments

References

- Oh, J.-S., Song, Y.-G., Choi, B.-G., Bhamornsut, C., Nakkuntod, R., Jo, C.-Y. & Lee, J.-H., 2021. Effect of Dendrite Fraction on the M23C6 Precipitation Behavior and the Mechanical Properties of High Cr White Irons. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), Metals, 11(10), 3 October, 11(1576), p. 19. [CrossRef]

- Fashu, S. & Trabadelo, V., 2023. Development and Performance of High Chromium White Cast Irons (HCWCIs) for Wear-Corrosive Environments: A Critical Review. Metals, 13(1831), pp. 1 - 26. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Shimizu, k., Yaer, X., Kusumoto K. & Efremenko, V. G., 2017. Erosive Wear Performance of Heat Treated Multi-Component Cast Iron Containing Cr, V, Mn and Ni Eroded by Alumina Spheres at Elevated Temperatures. Wear, 390, pp. 1 - 20. [CrossRef]

- Pasini, W. M., Polkowski, W., Dudziak, T., dos Santos, C. A., & de Barcellos, V. K., 2025. Microstructure Formation and Dry Reciprocating Sliding Wear Response of High-Entropy Hypereutectic White Cast Irons. Metals, 15(4), pp. 1 - 10. [CrossRef]

- Islak, S., Ozorak, C., Kir, D., Kucuk, O., Akkas, M. & Sezgin, C. T., 2015. The Effect of Different Carbon Content on the Microstructural Characterization of High Chromium White Cast Irons. Karabuk, Turkey, s.n., p. 4.

- Li, H., Zhuang, M., Li, C., Wu, S. & Rong, S., 2018. Effect of Carbon Element Change on Microstructure and Properties of Fe-Cr-C Surfacing Alloy. Earth and Environmental Science, 186, p. 6.

- Tian, Y., Ju, J., Fu, H., Shengqiang M. S., Lin, J. & Lei, Y., 2019. Effect of Chromium Content on Microstructure, Hardness, and Wear Resistance of As-Cast Fe-Cr-B Alloy. Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance, 28, p. 11.

- Ngqase, M. Nheta, W., Madzivhandila, T., Phasha, M. & Pan, X., 2024. Exploring Residual Stress Analysis in the Machining of Hypoeutectic High Chromium White Cast Iron Alloys Through the Hole-Drilling Method. Engineering Research Express, 6(045414), pp. 1 - 19.

- Mabeba, A. D., 2021. Development of High Vanadium Grinding Media Materials for the Comminution of Gold Ore, Thesis, Pretoria, Republic of South Africa: University of Pretoria.

- Moema, J. S., 2018. The Role of Retained Austenite on the Performance of High Chromium White Cast Iron and Carbidic Austempered Nodular Iron for Grinding Ball Applications, Thesis, Pretoria, Republic of South Africa: University of Pretoria.

- Ngoc, Q. H. T., Diem, N. T. V., Hoang, V. N., Hong, H. N., Thu, H. L. & Duong, N. N., 2022. Effect of Residual Stress Distribution on the Formation, Growth and Coalescence of Voids of 27Cr White Cast Iron Under Impact. Materials Transactions, 63(2), pp. 170 - 175. [CrossRef]

- Motsumi, V. M., 2021. Investigation of the Micro- and Macroscopic Wear Properties of Cemented Tungsten Carbide for the Wear Lining Material Selection of Chutes, Thesis, Johanneburg: s.n.

- Ngqase, M. & Pan, X., 2019. Microstructural Investigation on Heat Treatment of Hypoeutectic High. s.l., Journal of Physics, IOP Publishing, p. 12.

- Tupaj, M., Orłowicz, A. W., Trytek, A., Mróz, M., Wnuk, G. & Dolata, A. J., 2020. The Effect of Cooling Conditions on Martensite Transformation Temperature and hardness of 15%Cr Chromium Cast Irons. Materials, 13(2760), p. 13. [CrossRef]

- Ngqase, M., 2018. Validation of Physical Properties of HCWCI Alloys Towards Comprehensive Process Simulation Capabilities, Doorfontein, Johannesburg, South Africa: Thesis, University of Johannesburg.

- González, J., Peral, L. B., Zafra, A. & Fernández-Pariente, I., 2019. Influence of Shot Peening Treatment in Erosion Wear Behavior of High Chromium White Cast Iron. Metals, 9(933), pp. 1 - 12. [CrossRef]

- Xia, T., Cui, P., Song, T., Liu, X., Liu, Y., & Zhu, J., 2025. An Investigation of Heat Treatment Residual Stress of Type I, II, III for 8Cr4Mo4V Steel Bearing Ring Using FEA-CPFEM-GPA Method. Metals, 15(548), pp. 1 - 20. [CrossRef]

- Baghani, A., Davami, P., Varahram, N. & Shabani, M. O., 2014. Investigation on the Effect of Mold Constraints and Cooling Rate on Residual Stress During the Sand-Casting Process of 1086 Steel by Employing a Thermomechanical Model. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions B, 45, p. 13. [CrossRef]

- Elmquist, L., Brehmer, A., Schmidt, P. & Israelsson, B., 2018. Residual Stresses in Cast Iron Components – Simulated Results Verified by Experimental Measurements. Material Science Forum, 925, pp. 326 - 333. [CrossRef]

- Chaudry, U. M., Tekumalla, S., Gupta, M., Jun, T. -S. & Hamad, K., 2022. Designing Highly Ductile Magnesium Alloys: Current Status and Future Challenges. Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences, 47(2), pp. 194 - 281.

- Egan, P. F., 2023. Design for Additive Manufacturing: Recent Innovations and Future Directions. Design, 7(83), p. 32. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Sun, J., Peng, W., Yue, C., & Zhang, 2025. Coupled Analytical Model for Temperature-Phase Transition and Residual Stress in Hot-Rolled Coil Cooling Process. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 242(126864), pp. 1 - 27. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, E., Samuel, A. M., Songmene, V. & Samuel, F. H., 2023. A Review on the Analysis of Thermal and Thermodynamic Aspects of Grain Refinement of Aluminum-Silicon-Based Alloys. Materials, 16(5639), p. 29. [CrossRef]

- Nemyrovskyi, Y., Shepelenko, I. & Storchak, M., 2023. Plasticity Resource of Cast Iron at Deforming Broaching. Metals, 13(551), p. 19. [CrossRef]

- Gong, L., Fu, H. & Zhi, X., 2023. Corrosion Wear of Hypereutectic High Chromium Cast Iron: A Review. Metals, 13(308), p. 21. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, R. A., 2017. A Study of Residual Stresses in Low Alloy Steel Theta Ring Casting, Sheffield, South Yorkshire, England: ProQuest.

- Yang, Y., 2020. Development of a Method to Measure Residual Stresses in Cast Components with Complex Geometries, Stockholm, Sweden: KTH.

- Torres, I. N., Gilles, G., Tchuindjang, J. T., Lecomte-Beckers, J., Sinnaeve, M. & Habraken, A. M., 2014. Study of Residual Stresses in Bimetallic Work Rolls. Advanced Materials Research,996, pp. 580 - 585. [CrossRef]

- Alipooramirabad, H., Kianfar, S., Paradowska, A. & Ghomashchi, R., 2024. Residual Stress Measurement in Engine Block - An Overview. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 131, pp. 1 - 27.

- Tabatabaeian, A., Ghasem, H. R., Shokrieh, M. M., Marzbanrad, B., Baraheni, M. & Fotouhi, M., 2022. Residual Stress in Engineering Materials: A Review. Advanced Engineering Materials, 24(2100786), p. 28. [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, W., Lazoglu, I. & Liang, S. Y., 2022. Prediction and Control of Residual Stress-Based Distortions in the Machining of Aerospace Parts: A Review. Journal of Manufacturing Processes, 76, pp. 106 - 122. [CrossRef]

- Qutaba, S., Asmelash, M., Saptaji, K. & Azhari, A., 2022. A Review on Peening Processes and its Effect on Surfaces. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 120, pp. 4233 - 4270.

- Franceschi, A., Stahl, J., Kock, C., Selbmann, R., Ortmann-Ishkina, S., Jobst, A., Merklein, M., Kuhfuß, B., Bergmann, M., Behrens, B. -A., Volk, W. & Groche, P., 2021. Strategies for Residual Stress Adjustment in Bulk Metal Forming. Archive of Applied Mechanics, 91, pp. 3557 - 3577.

- Hayama, M., Kikuchi, S., Tsukahara, M. & Misaka, Y., 2024. Estimation of Residual Stress Relaxation in Low Alloy Steel with Different Hardness during Fatigue by in Situ X-Ray Measurement. International Journal of Fatigue, 178, pp. 1 - 11. [CrossRef]

- Bastola, N., Jahan, M. P., Rangasamy, N. & Rakurty, C. S., 2023. A Review of the Residual Stress Generation in Metal Additive Manufacturing: Analysis of Cause, Measurement, Effects, and Prevention. Micromachines, 14(7), 1480, pp. 1 - 30. [CrossRef]

- Ammar, M. M. A. & Shirinzadeh, B., 2022. Evaluation of Robotic Fiber Placement Effect on Process-Induced Residual Stresses Using Incremental Hole-Drilling Method. Polymer Composites, 43, pp. 4417 - 4436. [CrossRef]

- Yesudhas, S., Levitas, V. I., Lin, F., Pandey, K. K., & Smith, J. S., 2024. Unusual Plastic Strain-Induced Phase Transformation Phenomena in Silicon. Nature Communications, 15(7054), p. 13. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S. S., Samuel, A. M. & Samuel, F. H., 2018. Development of Residual Stresses in Al–Si Engine Blocks Subjected to Different Metallurgical Parameters. International Journal of Metal Casting, p. 13. [CrossRef]

- Nenchev, B., 2020. Modeling and Analysis of Solidification Shrinkage and Defect Prediction in Metals, Leicester, England: s.n.

- Soar, P., Kao, A., Djambazov, G., Shevchenko, N., Eckert, S. & Pericleous, K., 2020. The Integration of Structural Mechanics into Microstructure Solidification Modelling. Materials Science and Engineering, 861, p. 9.

- Wang, G.-H. & Li, Y.-X., 2020. Thermal conductivity of cast iron - A Review. Special Review, 17(2), pp. 85 - 95. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q., Zhao, P., Li, J., Wu, H., & Peng, J., 2025. Unveiling Temperature Distribution and Residual Stress Evolution of Additively Manufactured Ti6Al4V Alloy: A Thermomechanical Finite Element Simulation. Metals, 15(83), pp. 1 - 18. [CrossRef]

- Malik, I., Sani, A. A. & Medi, A., 2020. Study on using Casting Simulation Software for Design and Analysis of Riser Shapes in a Solidifying Casting Component. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1500, pp. 1 - 7.

- Pant, G., Reddy, M. S. S., Praveen, Parashar, A. K., Kareem, S. A. & Nijhawan, G., 2023. Advanced Casting Techniques for Complex-Shaped Components: Design, Simulation and Process Control. ICMPC, 430, pp. 1 - 10.

- Donghong, W., Yu, J., Yang, C., Hao, X., Zhang, L. & Peng, Y., 2022. Dimensional Control of Ring-to-Ring Casting with a Data-Driven Approach During Investment Casting. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 119, pp. 691 - 704. [CrossRef]

- Prikhod’ko, O. G., Deev, V. B., Prusov, E. S. & Kutsenko, A. I., 2020. Influence of Thermophysical Characteristics of Alloy and Mold Material on Casting Solidification Rate. Steel in Translation, 50(5), pp. 296 - 302. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Kang, J., Shangguan, H., Deng, C., Hu, Y., Yi, J. & Mao, W., 2022. Chimney Structure of Hollow Sand Mold for Casting Solidification. Metals, 12(415), p. 17. [CrossRef]

- Gurusamy, P., Bhattacharjee, B., Dutta, H. & Bhowmik, A., 2024. Study of Microstructural, Machining and Tribological Behaviour of AA-6061/SiC MMC Fabricated Through the Squeeze Casting Method and Optimized the Machining Parameters by Using Standard Deviation-PROMETHEE Technique. Silicon, 16, pp. 675 - 686.

- Zhiguo, Z., Chengkai, Y., Peng, Z. & Wei, L., 2014. Microstructure and Wear Resistance of High Chromium Cast Iron Containing Niobium. Reaserch & Development, May, 11(3), pp. 179 - 184.

- Lundberg, M. & Elmquist, L., 2018. Hole Drilling Residual Stress Evaluations in Cast Iron. Jönköping, Sweden, ECRS-10, pp. 89 - 94.

- Venu, B. & Ramachandra, R., 2017. Simulation of Residual Stresses in Castings. International Journal of Scientific Research in Science and Technology, 3(8), pp. 875 - 890.

- Demirer, E., Pourasiabi, H. & Gates, J. D., 2022. Effects of Particle Impingement and Coarse Particle Abrasion on Wear Performance of White Cast Irons in Sliding Bed Applications. Society of Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers, 65(4), pp. 1 - 16. [CrossRef]

- Duflou, J. R., Wegener, K., Tekkaya, A. E., Hauschild, M., Bleicher, F., Yan, J. & Hendrickx, B., 2024. Efficiently Preserving Material Resources in Manufacturing: Industrial Symbiosis Revisited. CIRP Annals- Manufacturing Technology,73, pp. 695 - 721. [CrossRef]

- Alsaihati, A. & Elkatatny, S., 2023. A New Method for Drill Cuttings Size Estimation Based on Machine Learning Technique. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, 28, pp. 16739 - 16751. [CrossRef]

- Sivan, S. S. S., Mrinal, B. D. J., Natarajan, S. & Chauhan, N., 2018. Analysis of Residual Stresses, Thermal Stresses, Cutting Forces and other Output Responses of Face Milling Operations on ZE41 Magnesium Alloy. International Journal of Modern Manufacturing Technologies, X(1), pp. 92 - 100.

- Schröder, J., Evans, A., Mishurova, T., Ulbricht, A., Sprengel, M., Serrano-Munoz, I., Fritsch, T., Kromm, A., Kannengießer, T. & Bruno, G., 2021. Diffraction-Based Residual Stress Characterization in Laser Additive Manufacturing of Metals. Metals, 11(1830), p. 34. [CrossRef]

- Scafidi, M., Valentini, E., & Zuccarello, B. (2011). Error and Uncertainty Analysis of the Residual Stresses Computed by Using the Hole Drilling Method. Strain - An International Journal for Experimental Mechanics, 47, 301 - 312. [CrossRef]

- Oettel, R., 2000. The Determination of Uncertainties in Residual Stress Measurement (Using the Hole Drilling Technique). Standards Measurement & Testing Project, Dresden, Germany. [CrossRef]

- Richter, R., & Muller, T. (2017). Measurement of Residual Stresses - Determination of Measurement Uncertainty of the Hole-Drilling Method used in Aluminium Alloys. Exp Tech, 41, 79 – 85.

- Olson, M. D., DeWald, A. T., & Hill, M. R. (2021). Precision of Hole-Drilling Residual Stress Depth Profile Measurements and an Updated Uncertainty Estimator. Experimental Mechanics, 61, 549 – 564. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., 1996. Handbook of Measurement of Residual Stresses.

- ASTM, E., 2013. 837-13a Standard Test Method for Determining Residual Stresses by the Hole-Drilling Strain-Gage Method. ASTM International, West Conshohocken.

- Gore B. and Nobre J.P., 2017. Effects of numerical methods on residual stress evaluation by the incremental hole-drilling technique using the integral method, Materials Research Proceedings, 2, pp. 587–592.

- Nobre, J.P., Guimaraes, R., Batista, A.C., Marques, M.J., Coelho, Nau, A., Scholtes, B., 2014. Evaluation of residual stresses induced by ultra-high-speed drilling in aluminium alloys, Materials Science Forum, 768-769, 128-135. [CrossRef]

- Flaman, M.T., 1982. Investigation of Ultra-High-Speed Drilling for Residual Stress Measurements by the Centre Hole Method, Experimental Mechanics, 22(1), pp. 26 - 30.

- Li, J., Xu, Y., Wang, H., Liu, Y., & Xu, Y., 2025. A Novel Model for Transformation-Induced Plasticity and Its Performance in Predicting Residual Stress in Quenched AISI 4140 Steel Cylinders. Metals, 15(450), pp. 1 - 19. [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, S. & Behrooz, A., 2022. A Review in Machining-Induced Residual Stress. 12(1), pp. 64 - 68.

- Guo, J., Fu, H., Pan, B. & Kang, R., 2021. Recent Progress of Residual Stress Measurement Methods: A Review. Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, 34(2), pp. 54 - 78. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S. M.; Wu, C. Y.; Chuang, T. L.; Wang, K. K.; Ma, N. Y., 2015. The Microstructure and Residual Stress Analysis of Gray Casting by Ultrasonic Technique. Taipei, Taiwan, s.n., pp. 1 - 5.

- Mehr, F. F., Cockcroft, S. & Maijer, D., 2020. A Fully-Coupled Thermal-Stress Model to Predict the Behavior of the Casting-Chill Interface in an Engine Block Sand Casting Process. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer, 152, pp. 1 - 15. [CrossRef]

- Andriollo, T., Hellström, K., Sonne, M. R., Thorborg, J., Tiedje, N. & Hattel, J., 2018. Uncovering the Local Inelastic Interactions during Manufacture of Ductile Cast Iron: How the Substructure of the Graphite Particles can Induce Residual Stress Concentrations in the Matrix. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 111, pp. 333 - 357. [CrossRef]

- Smit, T. C., Nobre, J. P., Reid, R. G., Wu, T., Niendorf, T., Marais, D. & Venter, A. M., 2022. Assessment and Validation of Incremental Hole-Drilling Calculation Methods for Residual Stress Determination in Fiber-Metal Laminates. Advances in Residual Stress Technology, 62, pp. 1289 - 1304. [CrossRef]

- Barile, C., Casavola, C., Pappalettera, G. & Pappalettere, C., 2014. Remarks on Residual Stress Measurement by Hole-Drilling and Electronic Speckle Pattern Interferometry. The Scientific World Journal, 2014, pp. 1 - 7. [CrossRef]

- Ngqase, M. & Pan, X., 2020. An Overview on Types of White Cast Irons and High Chromium White Cast Irons. International Conference on Multifunctional Materials (ICMM-2019) - Journal of Physics: Conference Series, p. 13.

- Ngqase, M. & Pan, X., 2020. XRD Investigation on Heat Treatment of High Chrome White Cast Irons. s.l., Journal of Physics, IO Pushiling, p. 11.

- Seidu, S. O., Oloruntoba, D. T. & Otunniyi, I. O., 2014. Effect of Shakeout Time on Microstructure and Hardness Properties of Grey Cast Iron. Journal of Minerals and Materials Characterization and Engineering, 2, pp. 346 - 350. [CrossRef]

- Borle, S. D., 2014. Microstructural Characterisation of Chromium Carbide Overlays and a Study of Alternative Welding Processes for Industrial Wear Applications, Phd Thesis, Admonton, Alberta: Spring.

- Zhang, Y. B., Andriollo, T., Fæster, S., Liu, W., Hattel, J. & Barabash, R. I., 2016. Three-Dimensional Local Residual Stress and Orientation Gradients Near Graphite Nodules in Ductile Cast Iron. Acta Materialia, 121, pp. 173 - 180. [CrossRef]

- Milenin, A., Kustra, P., Kuziak, R. & Pietrzyk, M., 2014. Model of Residual Stresses in Hot-Rolled Sheets with Taking into Account Relaxation Process and Phase Transformation. Procedia Engineering, 81, pp. 108 - 113. [CrossRef]

- Song, J., Huang, Y., Gan, W. & Hort, N., 2014. Residual Stresses of the As-Cast Mg-xCa Alloys with Hot Sprues by Neutron Diffraction. Advanced Materials Research, 996, pp. 592 - 597. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Zheng, R., Liu, X., Li, M., & Chen, D., 2025. Effect of Heat Treatment on Microstructure and Residual Stress of a Nickel-Cobalt-Based Superalloy Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Metals, 15(405), pp. 1 - 22. [CrossRef]

- Keste, A. A., Gawande, H. S. & Sarkar, C., 2016. Design Optimization of Precision Casting for Residual Stress Reduction. Journal of Computational Design and Engineering, 3, pp. 140 - 150. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q., Zeng, Y., Li, J., Wang, Y., Tang, G. & Wang, Y., 2024. Effect of Carbides on Thermos-Plastic and Crack Initiation and Expansion of High-Carbon Chromium-Bearing Steel Castings. Metals, 14(335), pp. 1 - 19. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Liu, J., Wu, H., Miao, K., Wu, H., & Li, R., 2024. Review Article: Research Progress of Residual Stress Measurement Methods. Heliyon,, 10(e28348), pp. 1 - 25.

- Sroka, J., 2021. Residual Stresses in lLarge Sizes Forgings, Sheffield, England: s.n.

- Lundberg, M., 2018. Residual Stresses, Fatigue and Deformation in Cast Iron, s.l.: LiU-Tryck.

- Zha, S., Zhang, H., Yang, J., Zhang, Z., Qi, X., & Zu, Q., 2025. Fatigue Threshold and Microstructure Characteristic of TC4 Titanium Alloy Processed by Laser Shock. Metals, 15(453), pp. 1 - 14. [CrossRef]

- Yelamasetti, B., Sushma, S. P., Mohammed, Z., Altammar, H., Khan, M. F., & Moinuddin, S. Q., 2025. Synergistic Effects of Thermal Cycles and Residual Stress on Microstructural Evolution and Mechanical Properties in Monel 400 and AISI 316L Weld Joints. Metals, 15(469), pp. 1 - 20. [CrossRef]

| Casting Parameters | Casting Identity Number (CId) | |

|---|---|---|

| S/A | S/B | |

| Melting Temperature (TM) in oC | 1480.00 | 1480.00 |

| Casting Temperature (TC) in oC | 1384.00 | 1390.00 |

| Casting Shakeout Temperature (CST) in oC | 60.00 | 180.00 |

| Knockout Period (CKP) in minutes (mins) | 1645.00 | 1295.00 |

| Pouring Time (PT) in seconds (secs) | 22.00 | 23.00 |

| Gross Casting Weight in Kilograms (kg) | 114.28 | 113.48 |

| Net Casting Weight in Kilograms (kg) | 90.16 | 88.25 |

| Element | Composition (wt. %) | Casting Identity Number (CId) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| S/A | S/B | ||

| C | 2.0 – 3.3 | 2.50 | 2.70 |

| Si | ≤ 1.50 | 0.60 | 0.73 |

| Mn | ≤ 2.00 | 0.66 | 0.66 |

| S | ≤ 0.100 | 0.054 | 0.075 |

| P | ≤ 0.060 | 0.026 | 0.070 |

| Cr | 23.0 – 30.0 | 24.09 | 25.65 |

| Mo | ≤ 3.00 | 0.19 | 0.17 |

| Ni | ≤ 2.50 | 0.36 | 0.44 |

| Cu | ≤ 1.20 | 0.20 | 0.12 |

| Fe | bal. | 71.00 | 69.00 |

| CVF (%) | 28.87 | 32.19 | |

| Cr/C Ratio | 9.6 | 9.50 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).