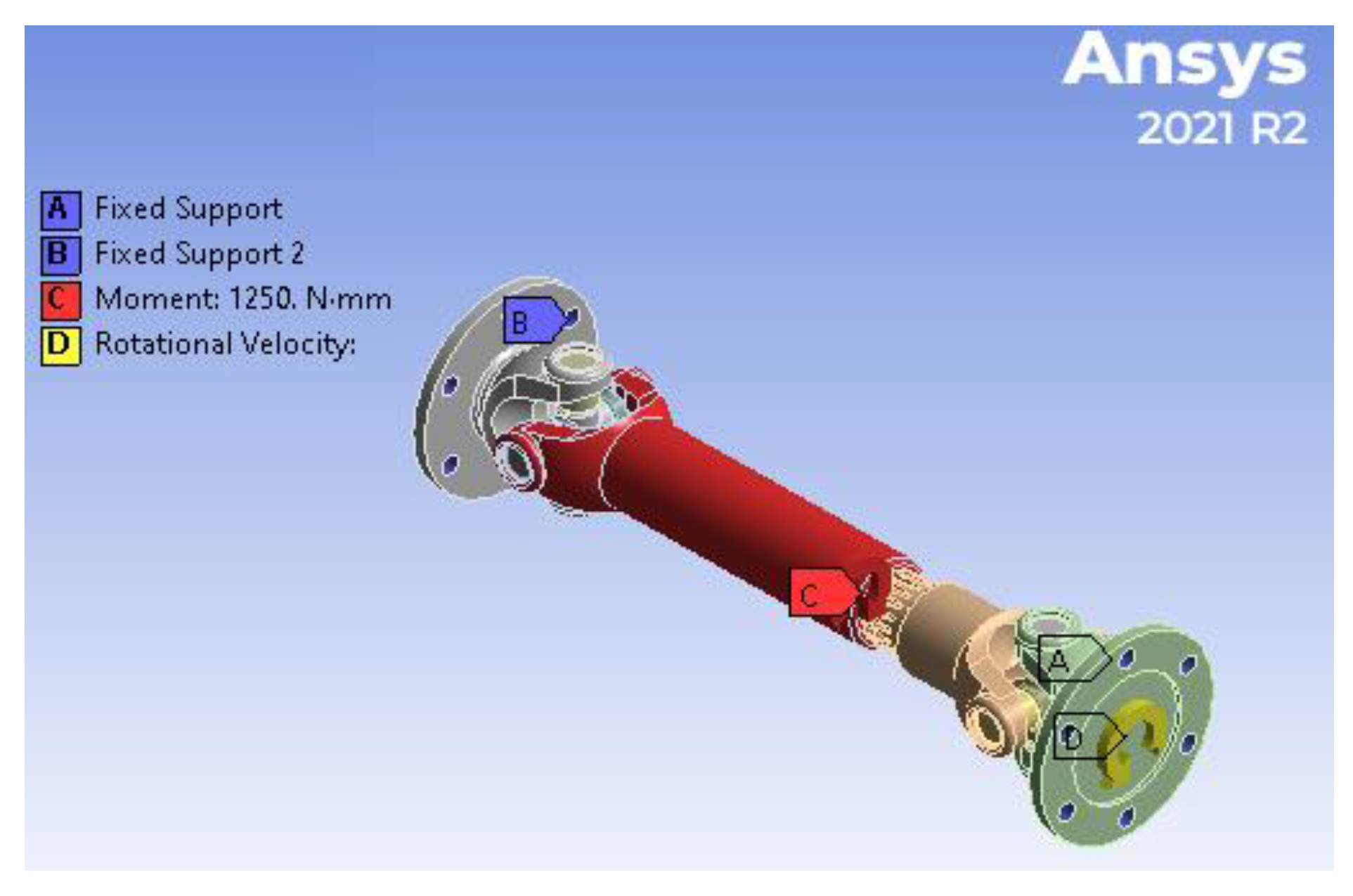

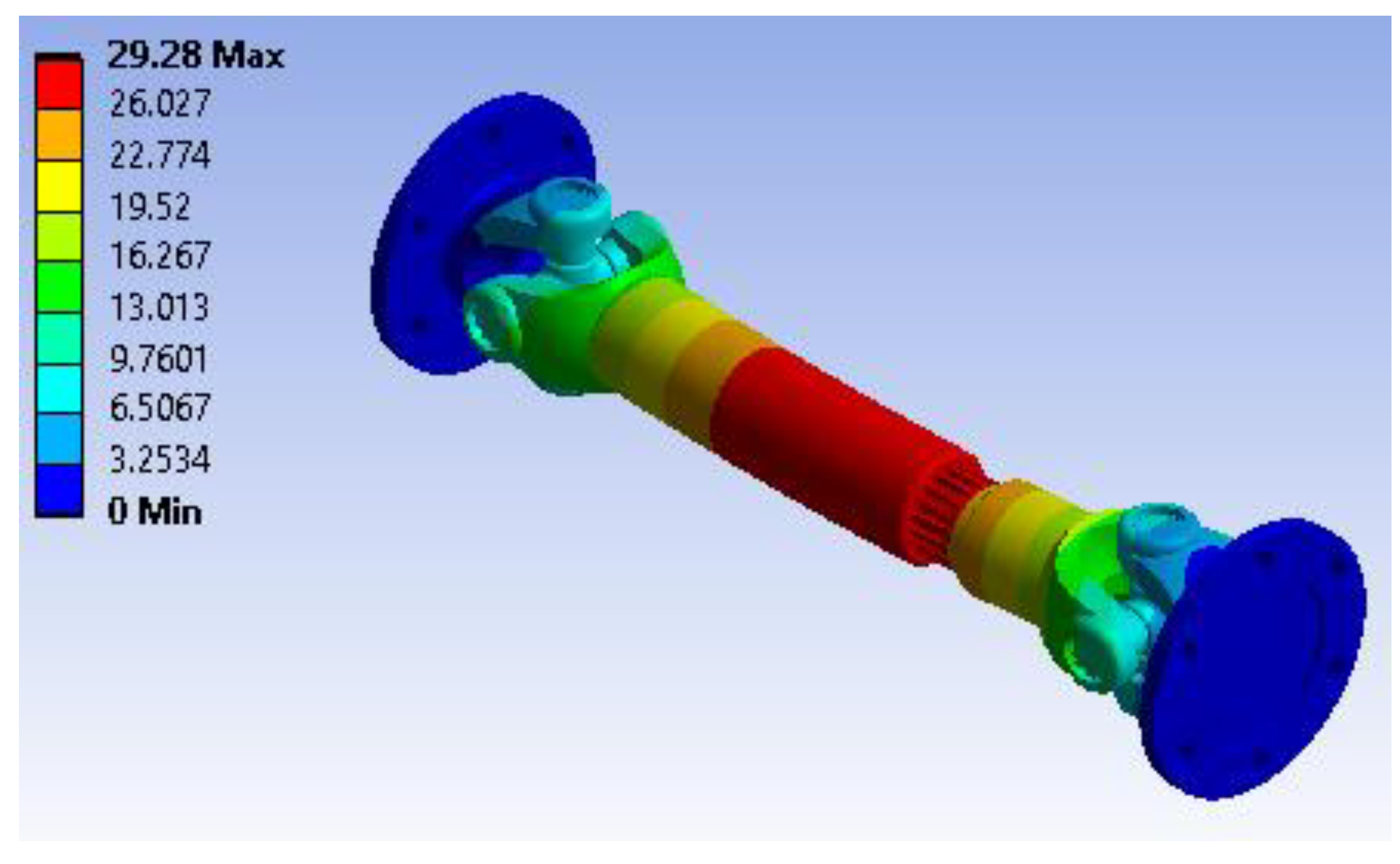

3.1. Structural analysis

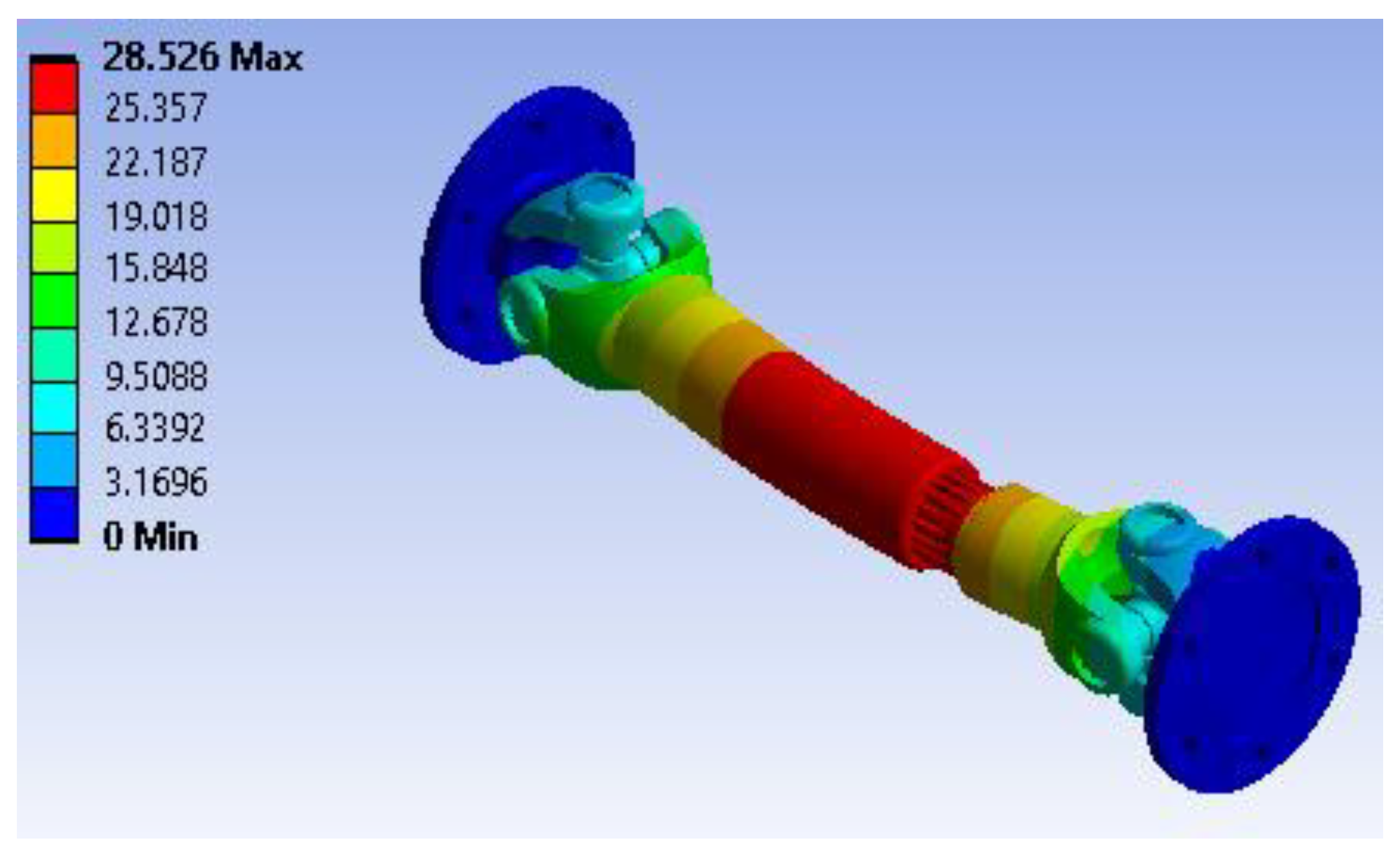

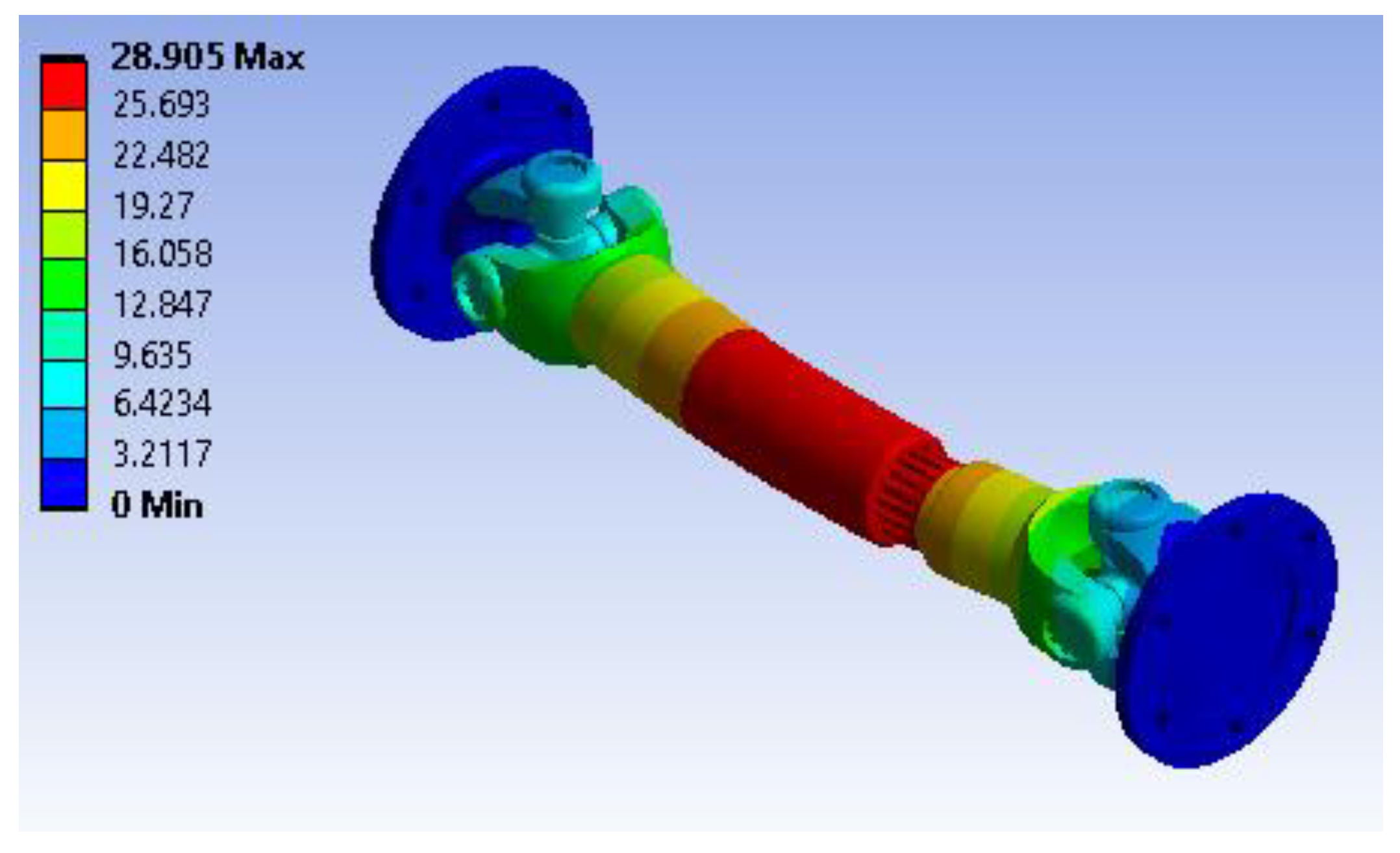

As a result of analyses, the obtained steel, which is listed in table 3, is used as conventional two-piece cardan shaft material [

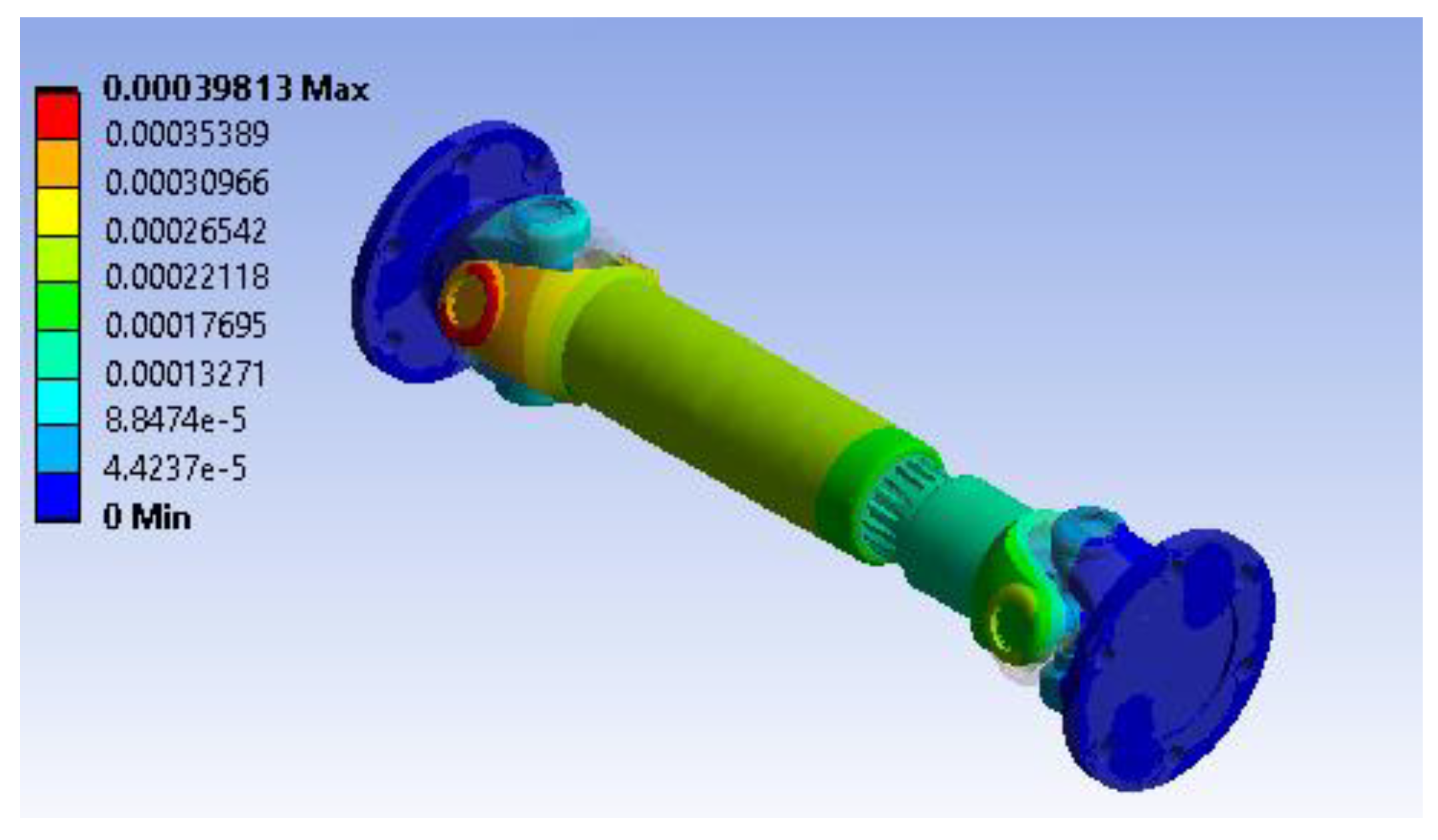

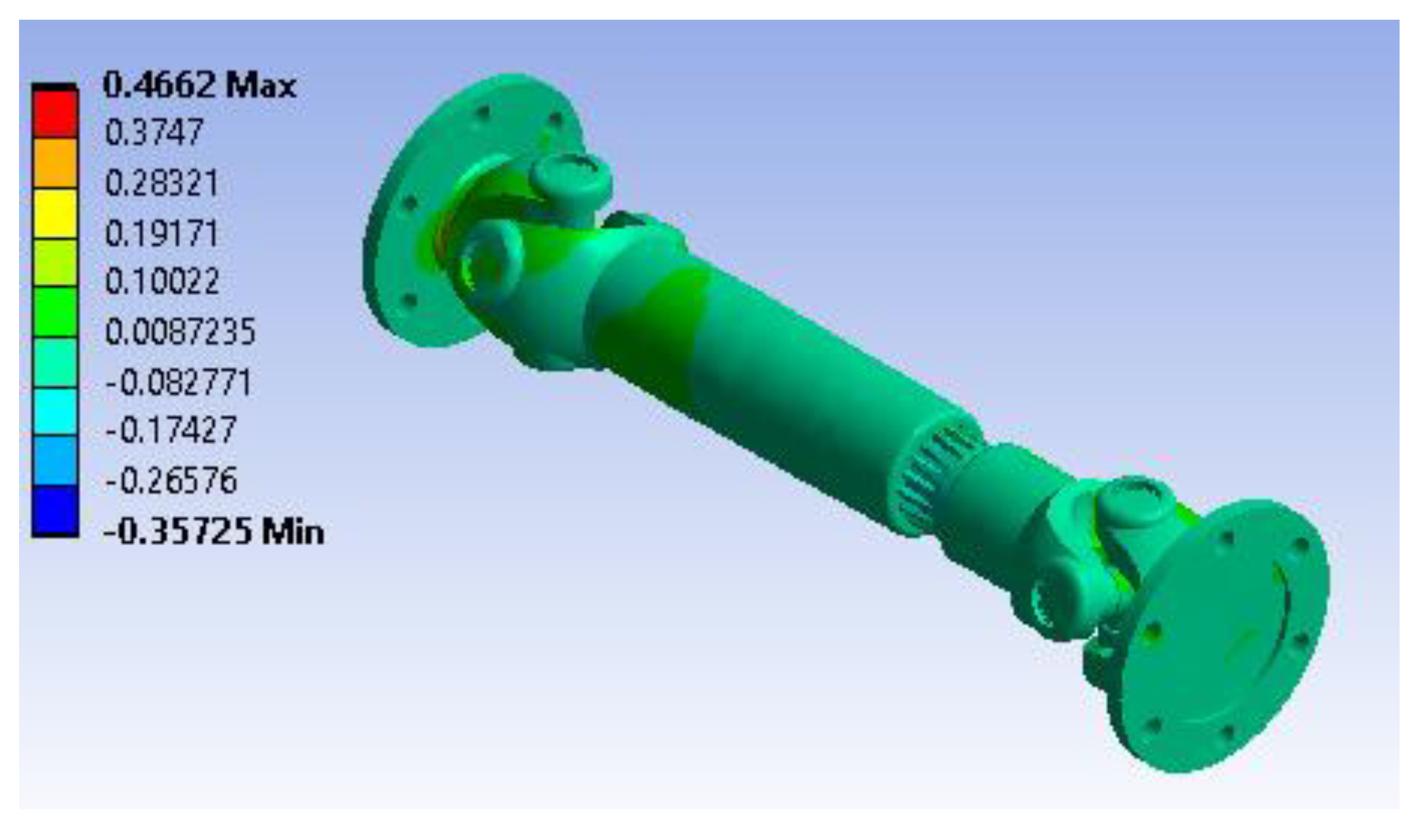

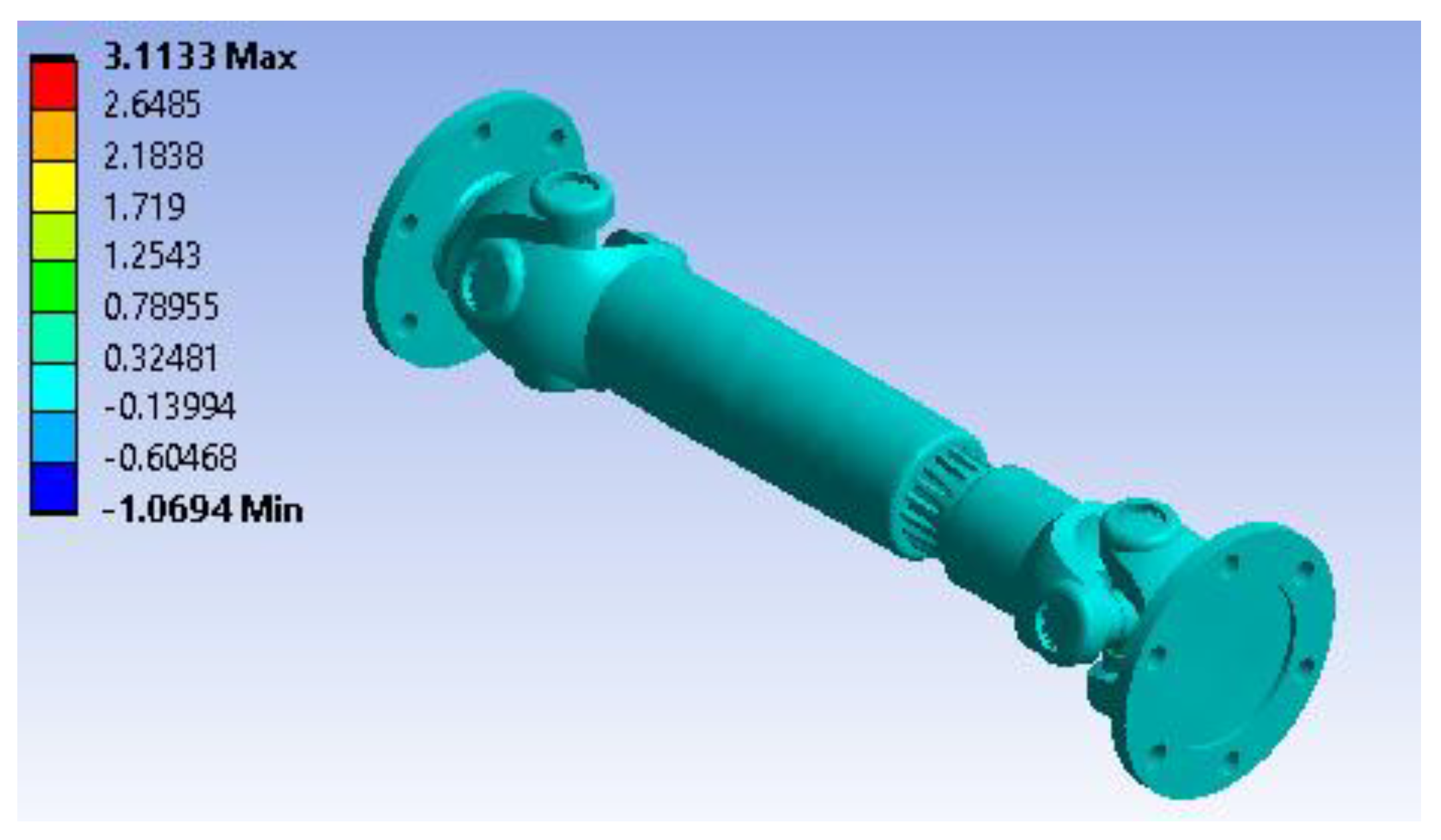

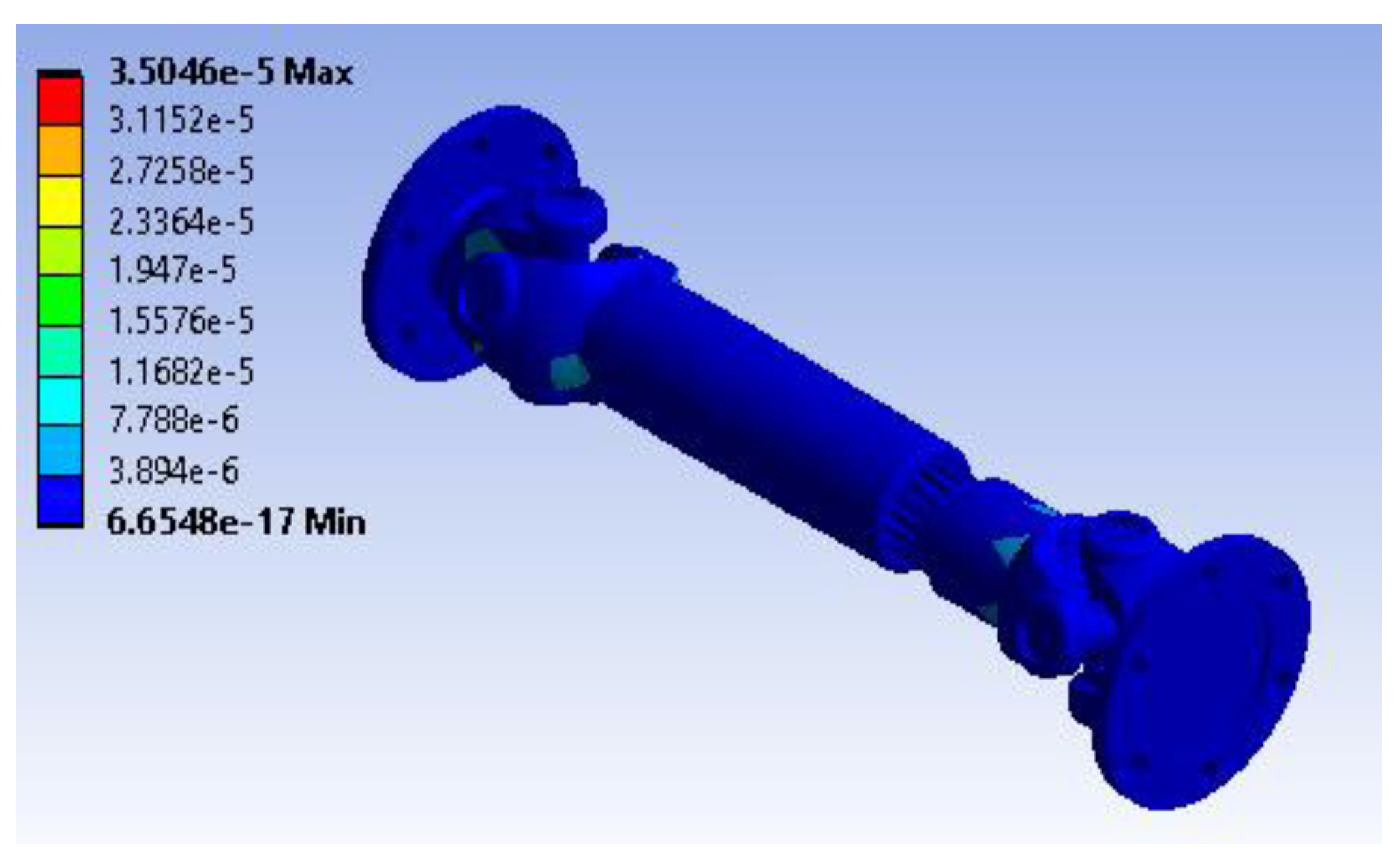

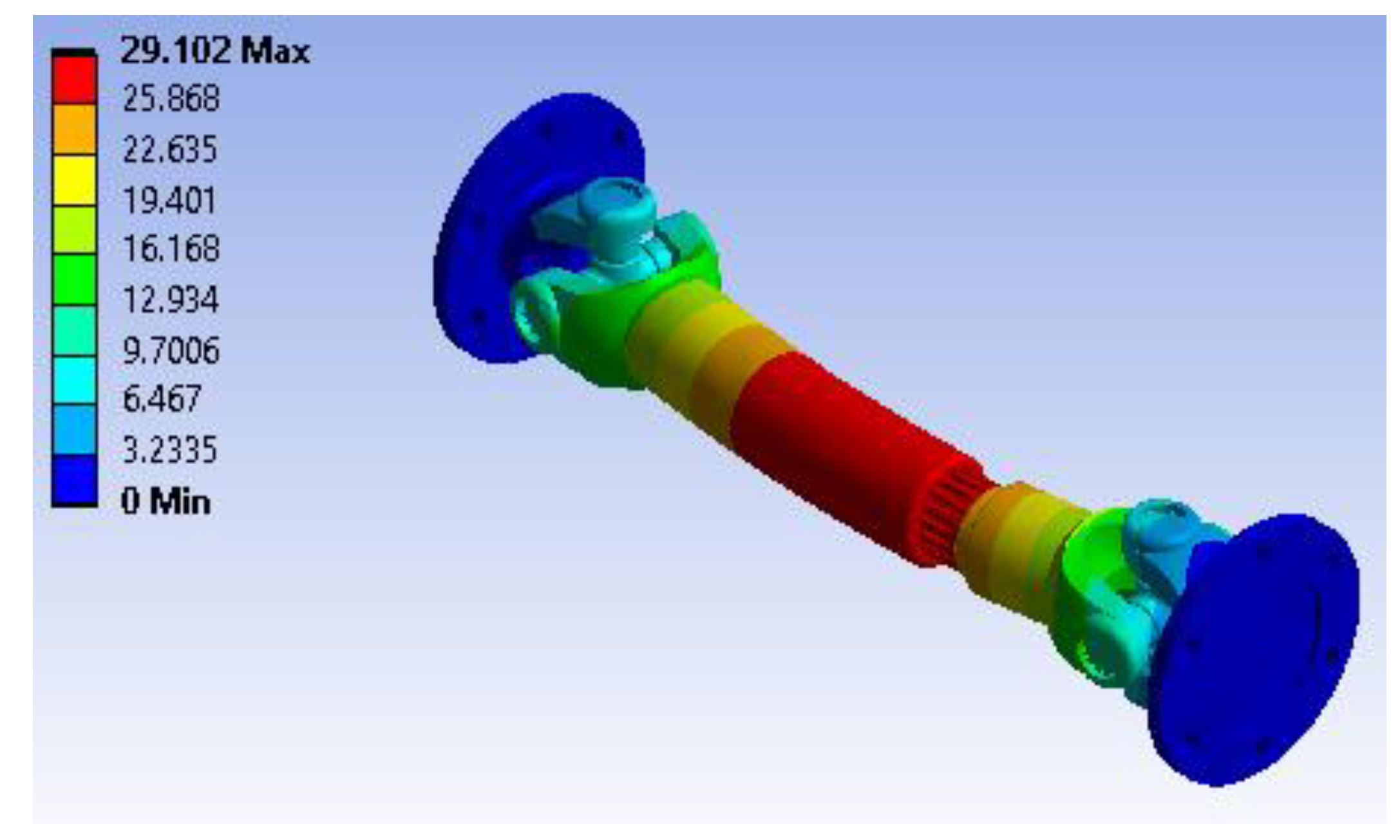

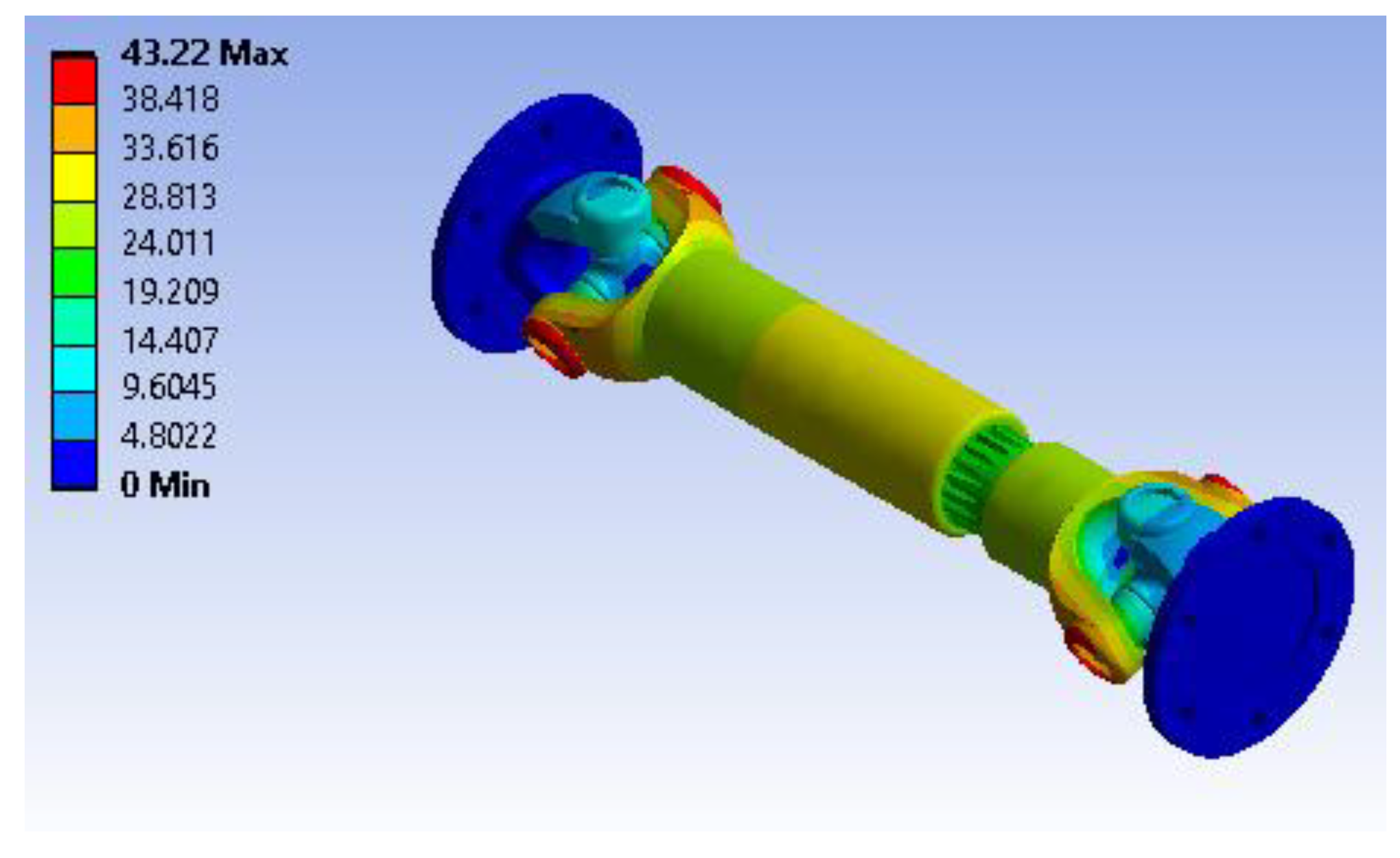

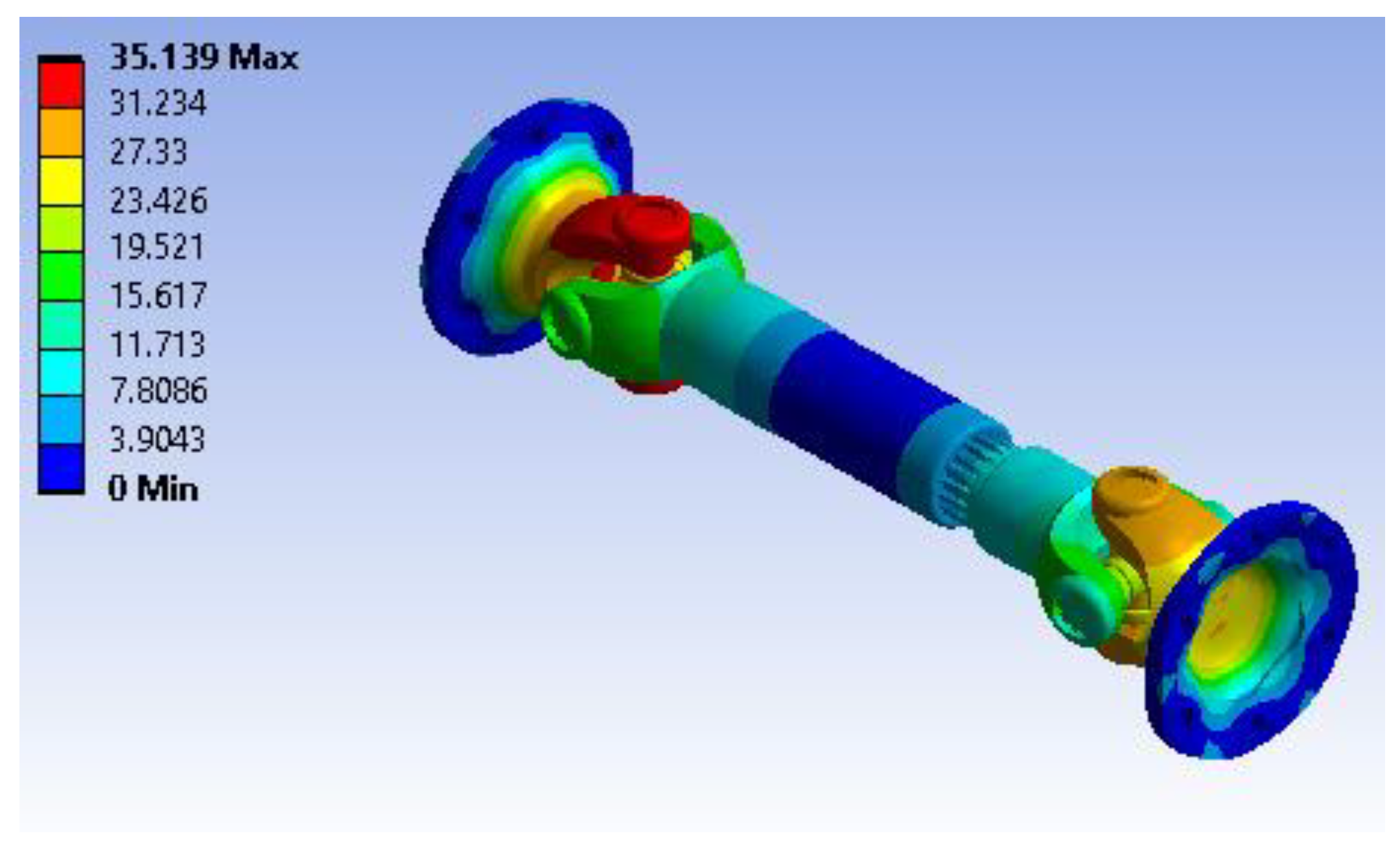

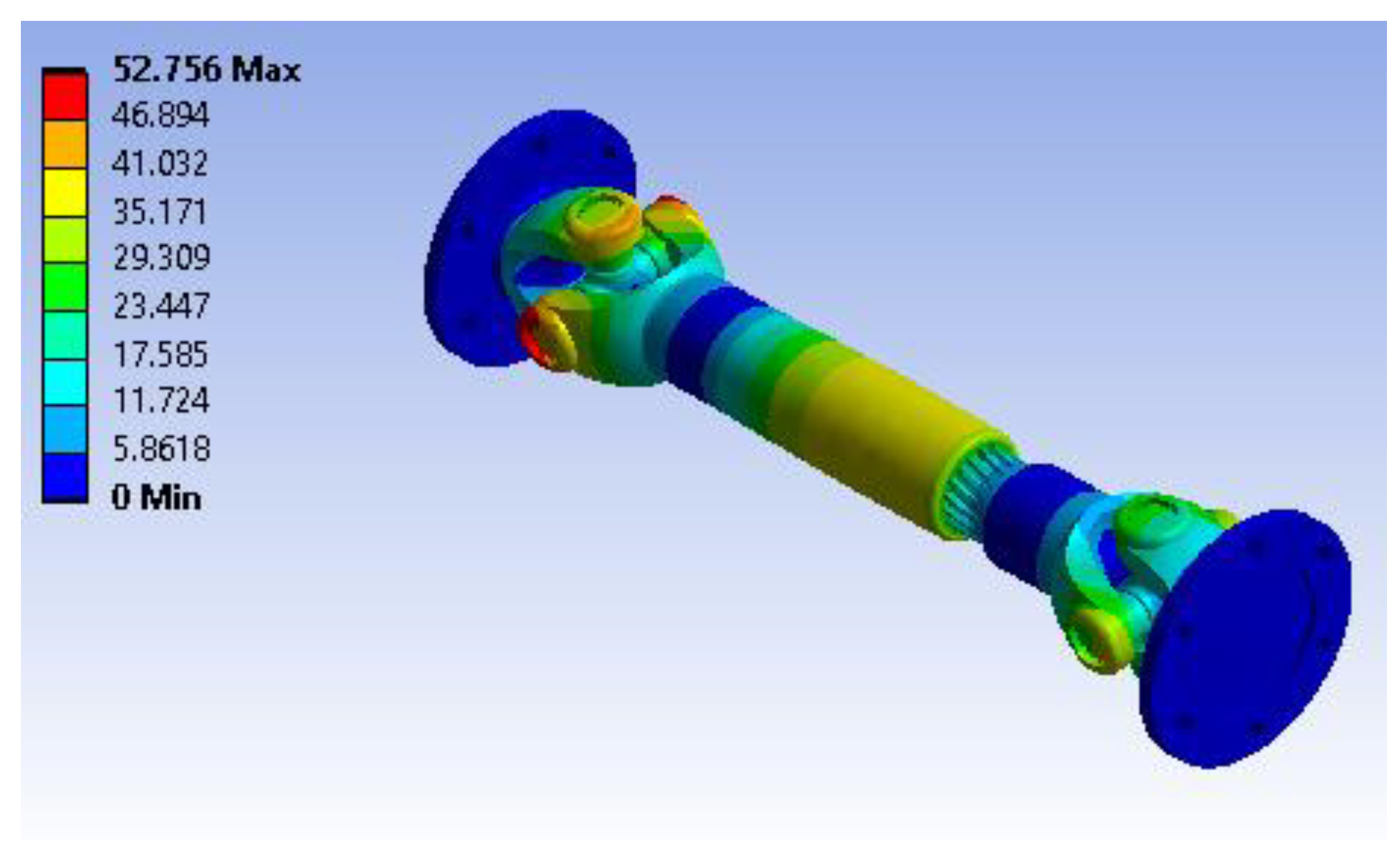

2]. The structural analysis simulation results are shown in Figure (9, 10, 11 and 12).

Figure 9 shows the total deformation of the shaft coupling under the specified loading and boundary conditions. The maximum deformation reaches approximately 0.00039813 m (0.398 mm) at the most stressed area, shown in red near the end where the torsional load is applied. The blue regions indicate minimal displacement, which corresponds to the fixed end support that restrict movement. This level of deformation is small and indicates that the assembly exhibits adequate stiffness under the imposed loads.

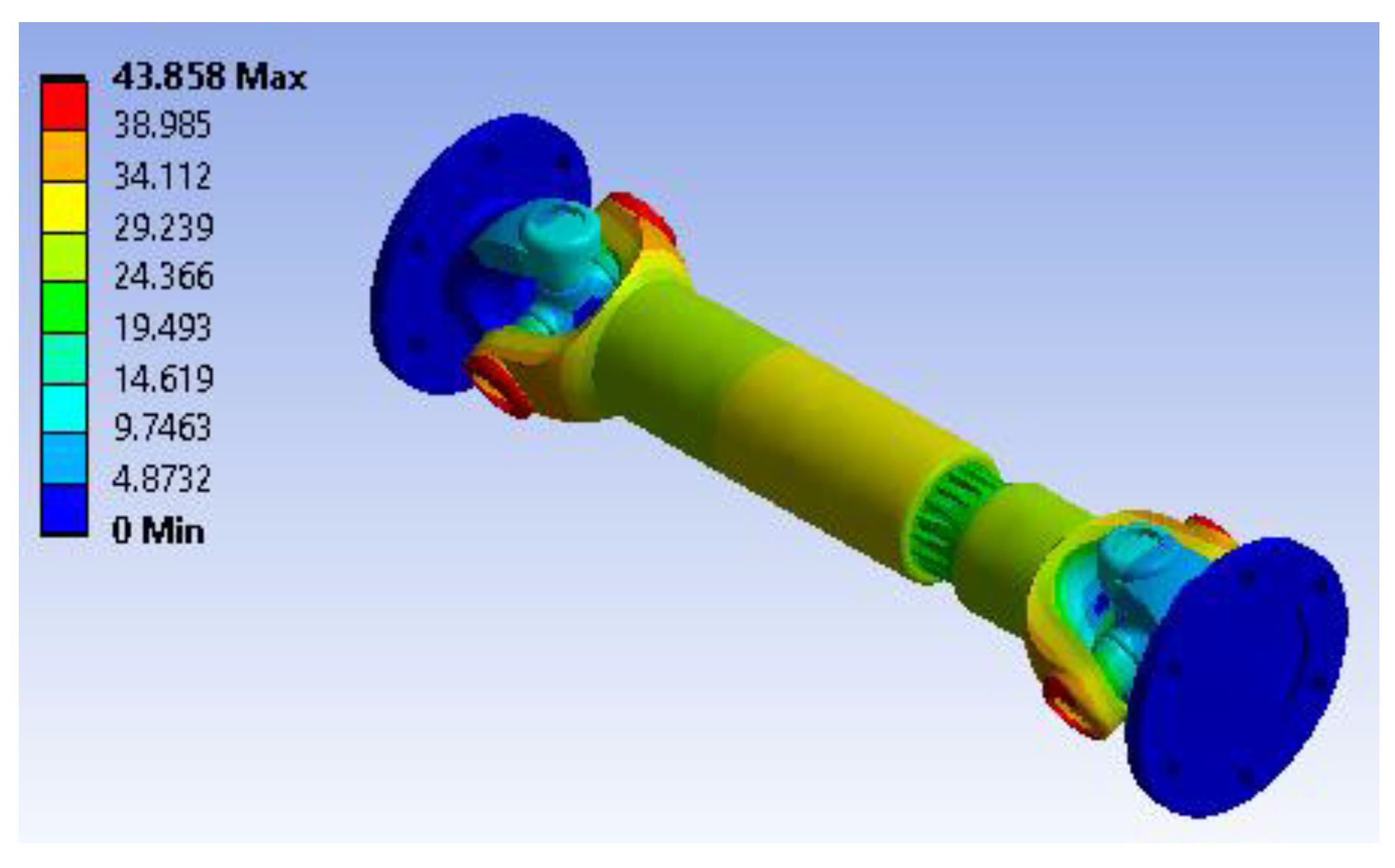

Figure 10 illustrates the shear stress distribution (XY plane) across the coupling. The highest shear stress is approximately 0.4662 MPa, as indicated by the red color around one of the flange connections. Green and blue areas show much lower shear stress levels, approaching -0.3572 MPa at the least-stressed locations. The localized high shear stresses suggest that these flange and joint areas are most critical for potential material yielding under torsional load.

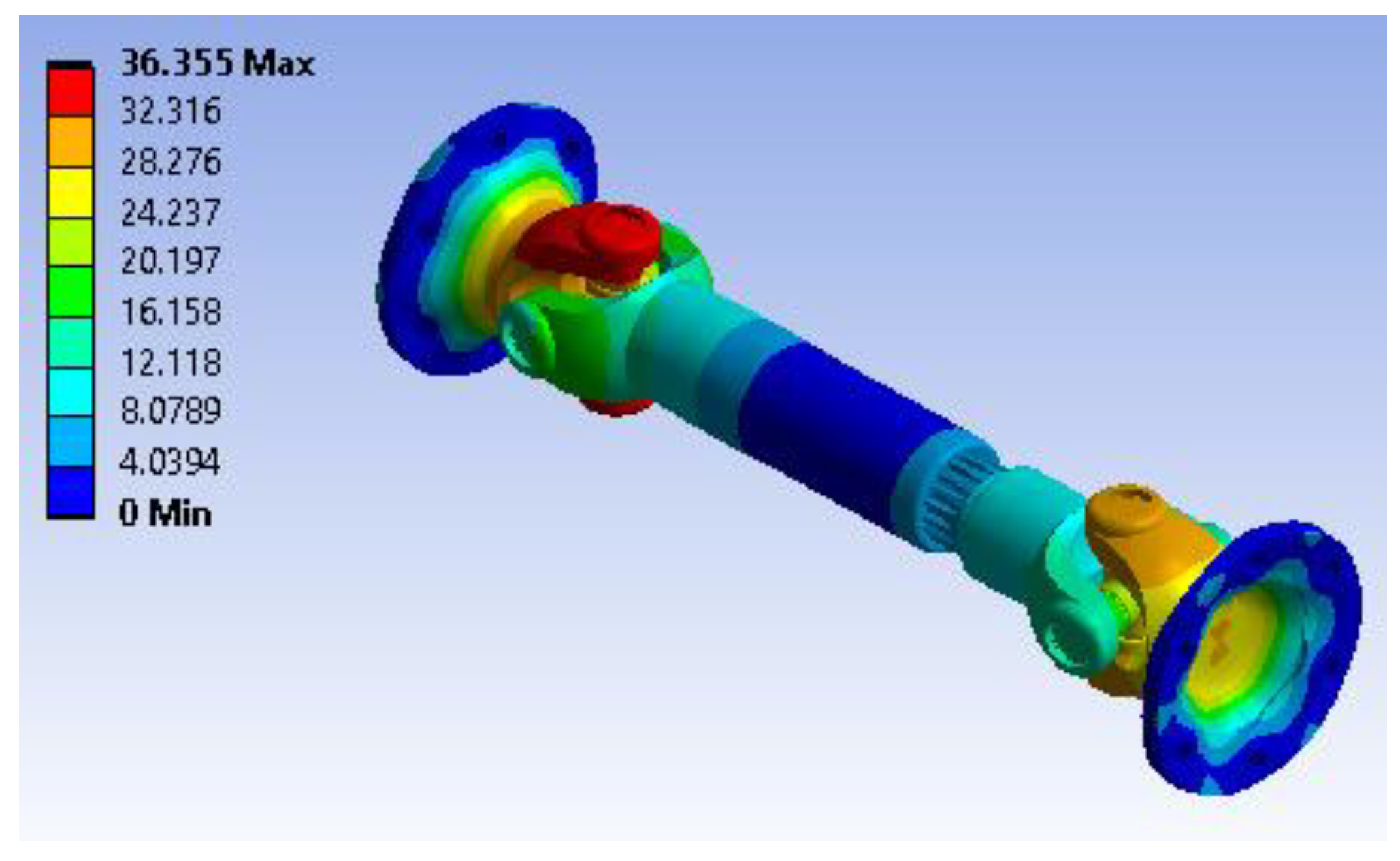

Figure 11 presents the maximum principal stress variation throughout the model. The most highly stressed region reaches a peak of 3.1133 MPa, evident in red, while the lowest value is approximately -1.0694 MPa. These principal stresses highlight areas under tension or compression, especially along the shaft and coupling connection. Evaluating these results is important for ensuring the component stays well within the material’s yield strength and fatigue limits under service loads.

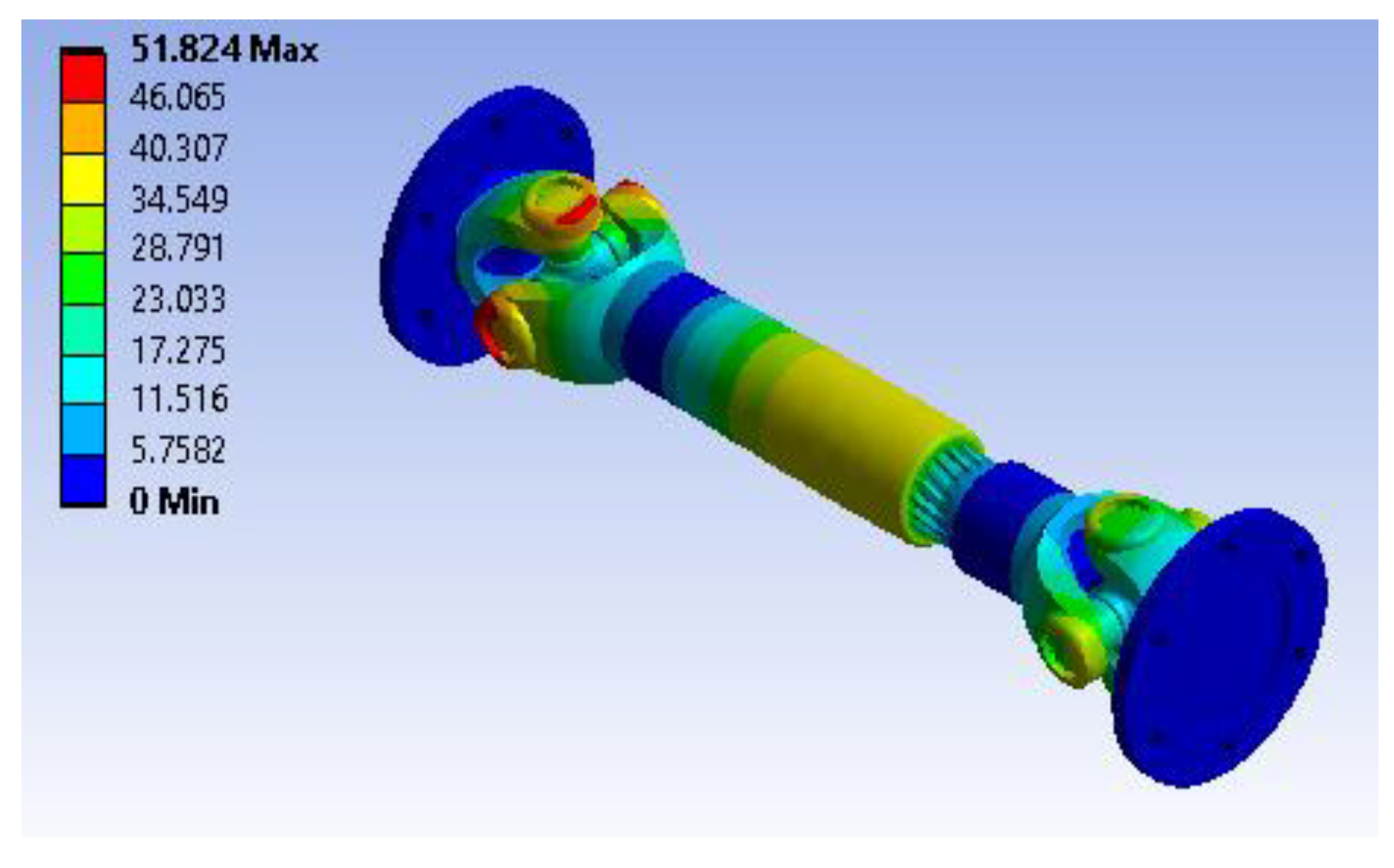

Figure 12 displays the strain energy distribution across the assembly. The maximum strain energy is around 3.5046e-5 J, concentrated in the most highly loaded section of the coupling (shown in red), while most other areas have very low energy absorption. This indicates that the structure effectively distributes and absorbs strain energy without excessive localized stress, implying a stable design under the operating torque and rotational velocity.

- 2.

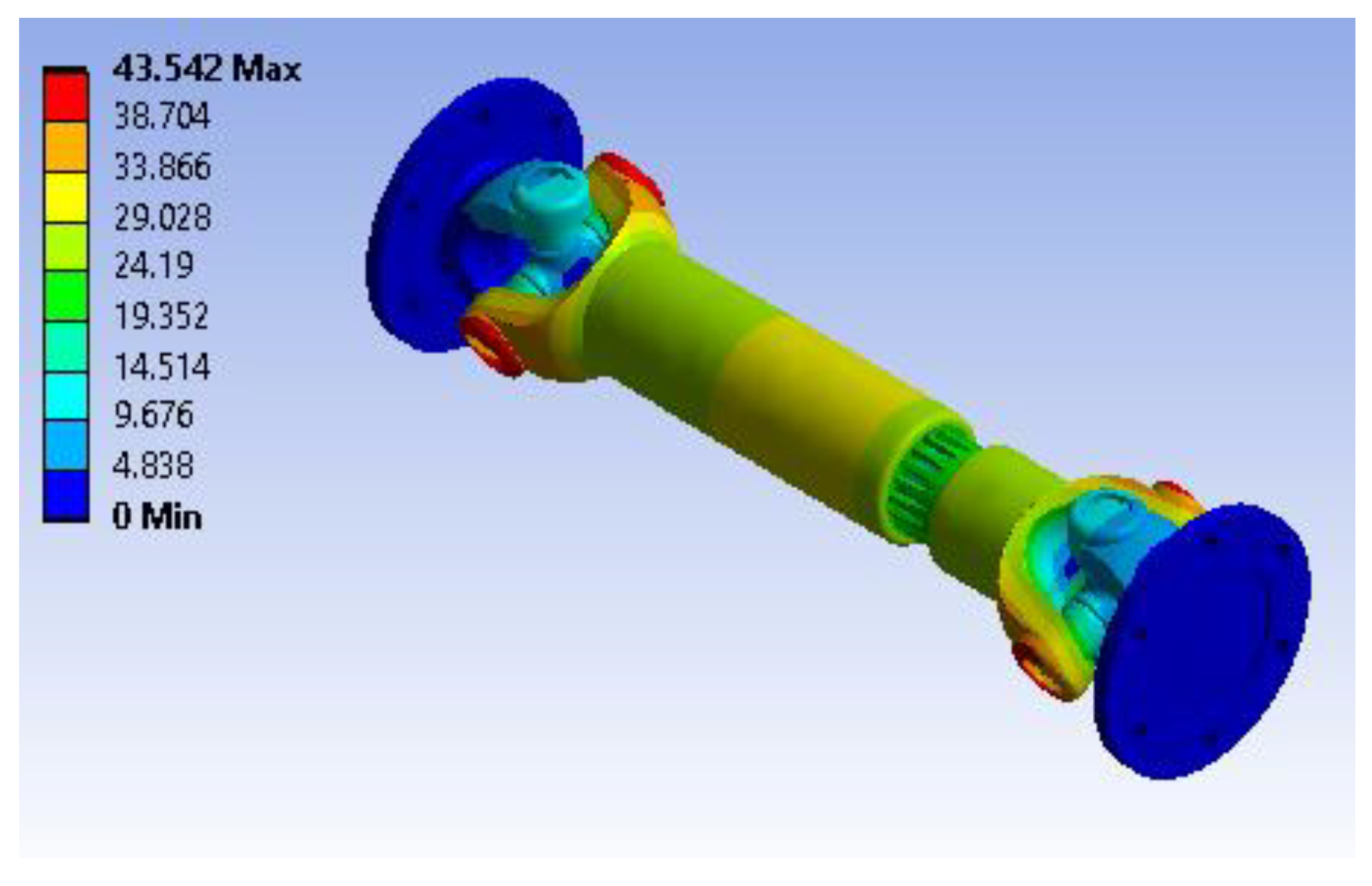

Structural analysis coating HS-Carbon Epoxy steel

As a result of analyses, the obtained HS-Carbon Epoxy steel, which is listed in table 3, and has coating layer at 0.5 mm on surface of steel, is used as conventional two-piece cardan shaft material [

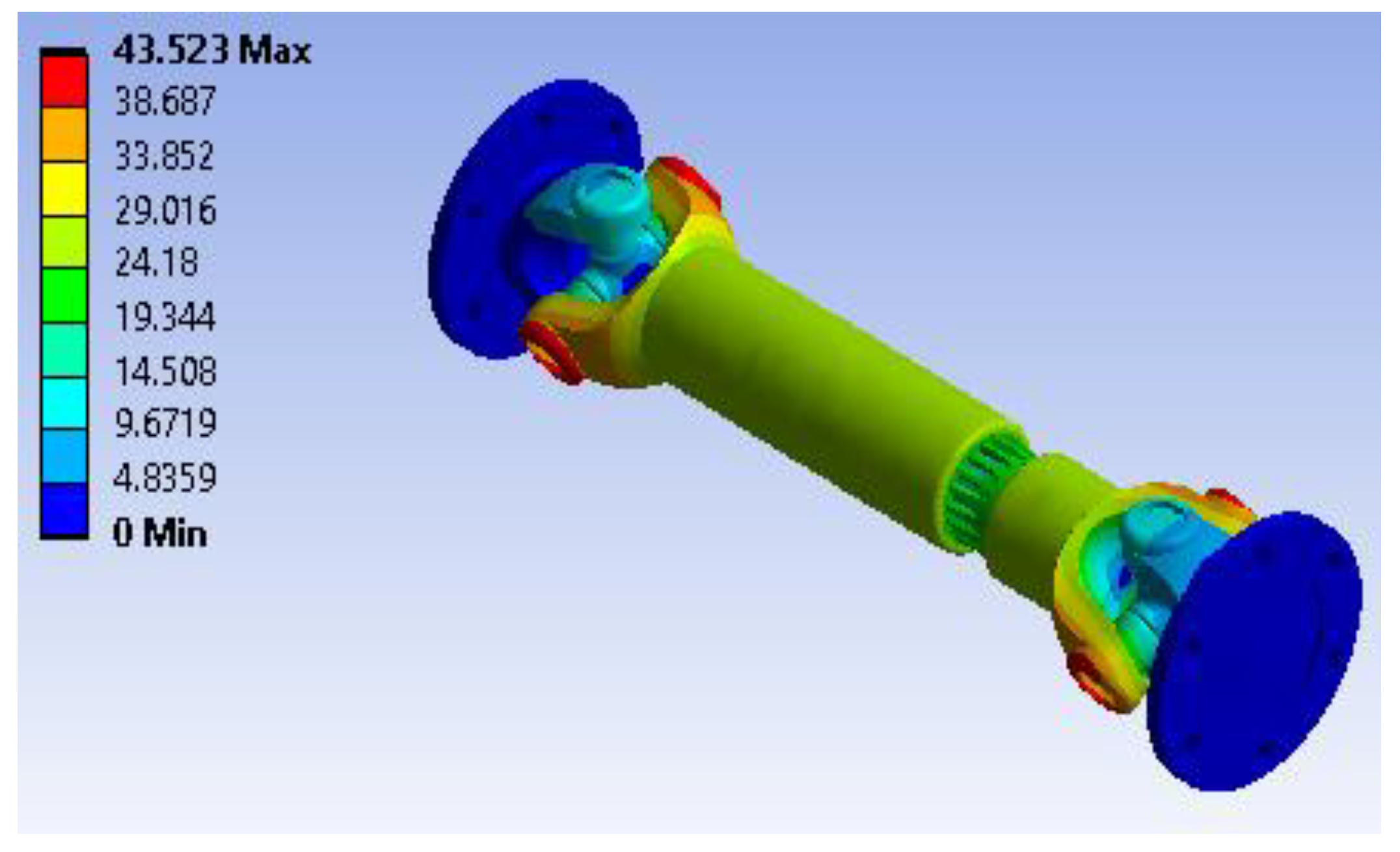

14]. The structural analysis simulation results are shown in Figure (13, 14, 15 and 16).

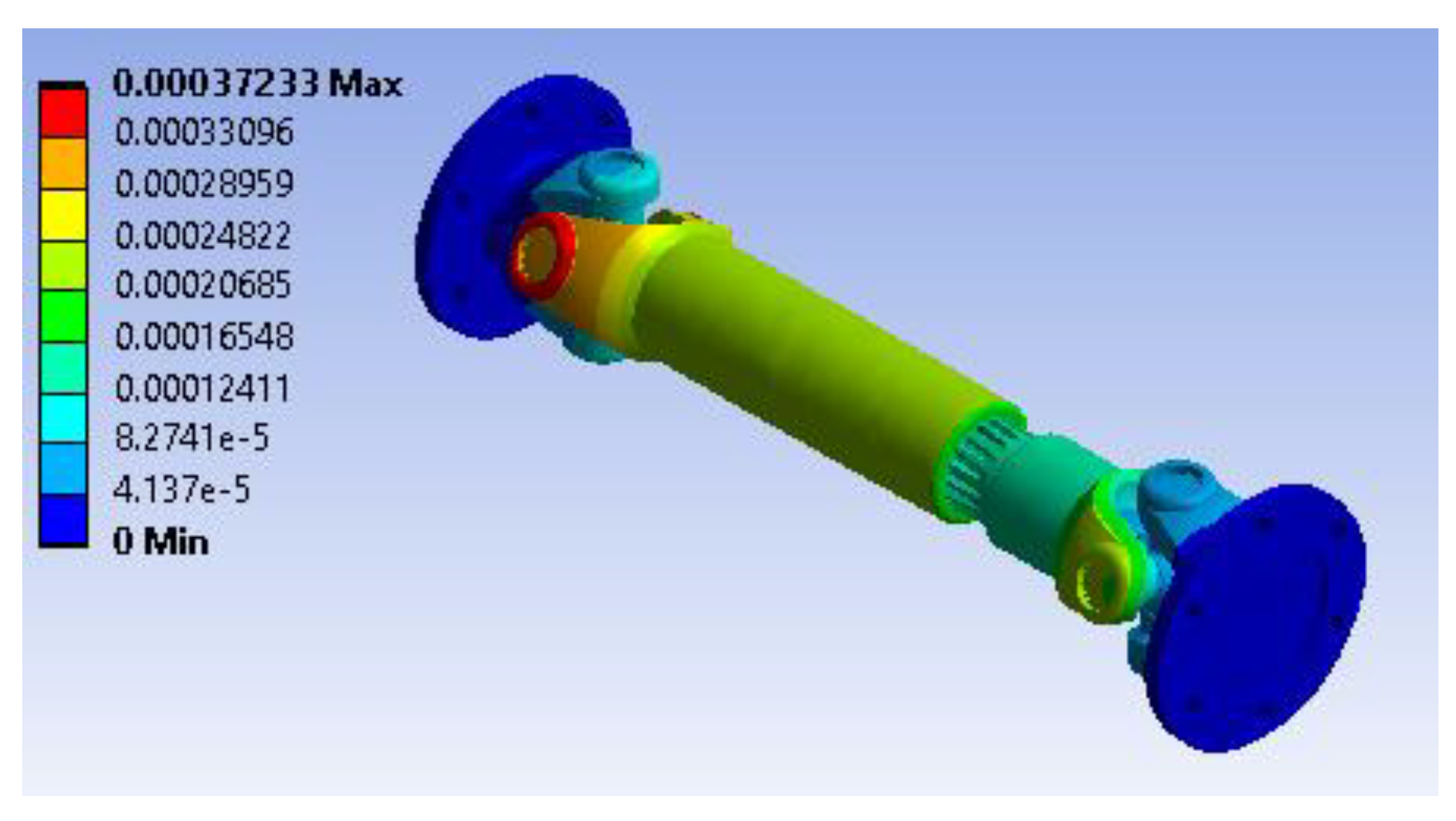

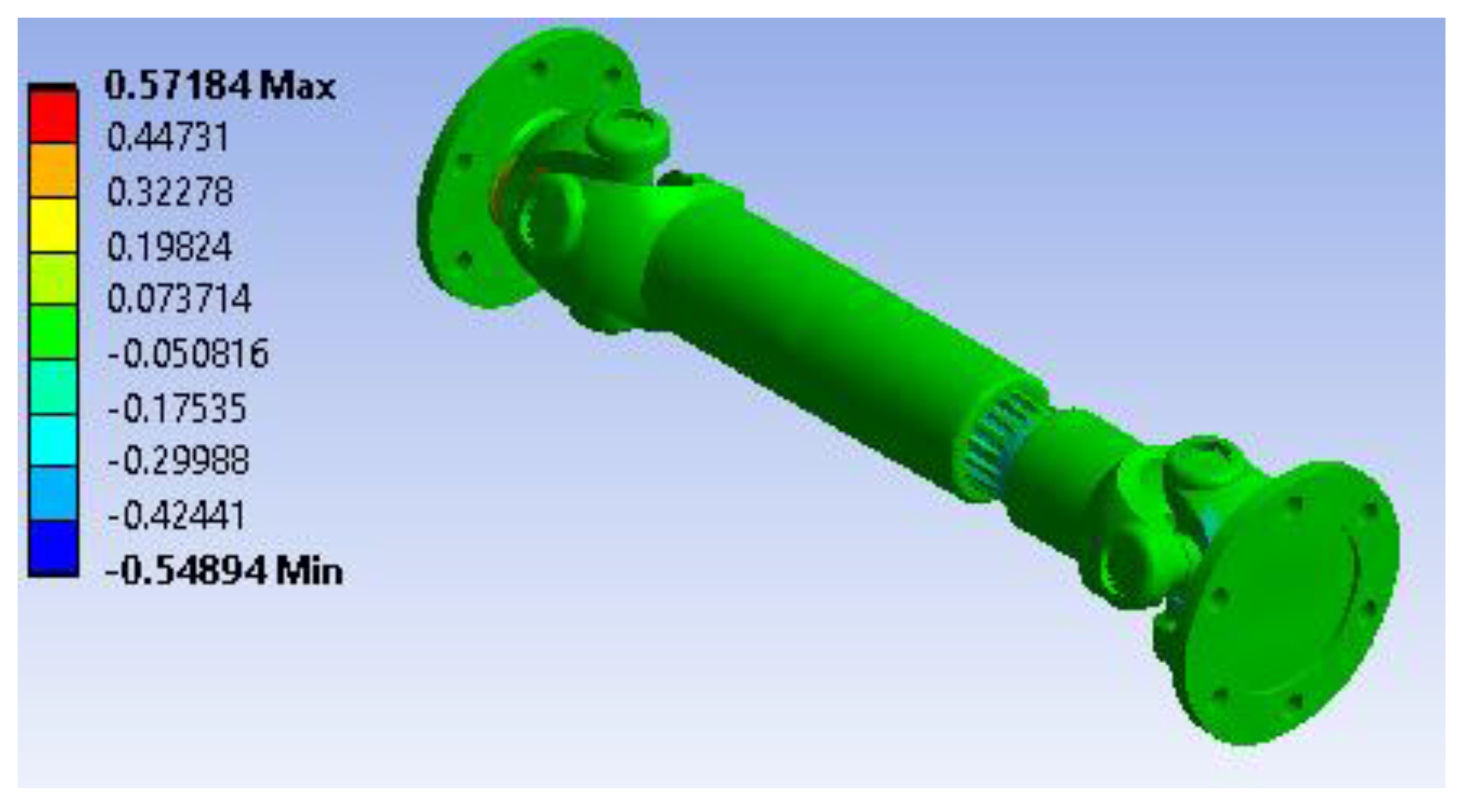

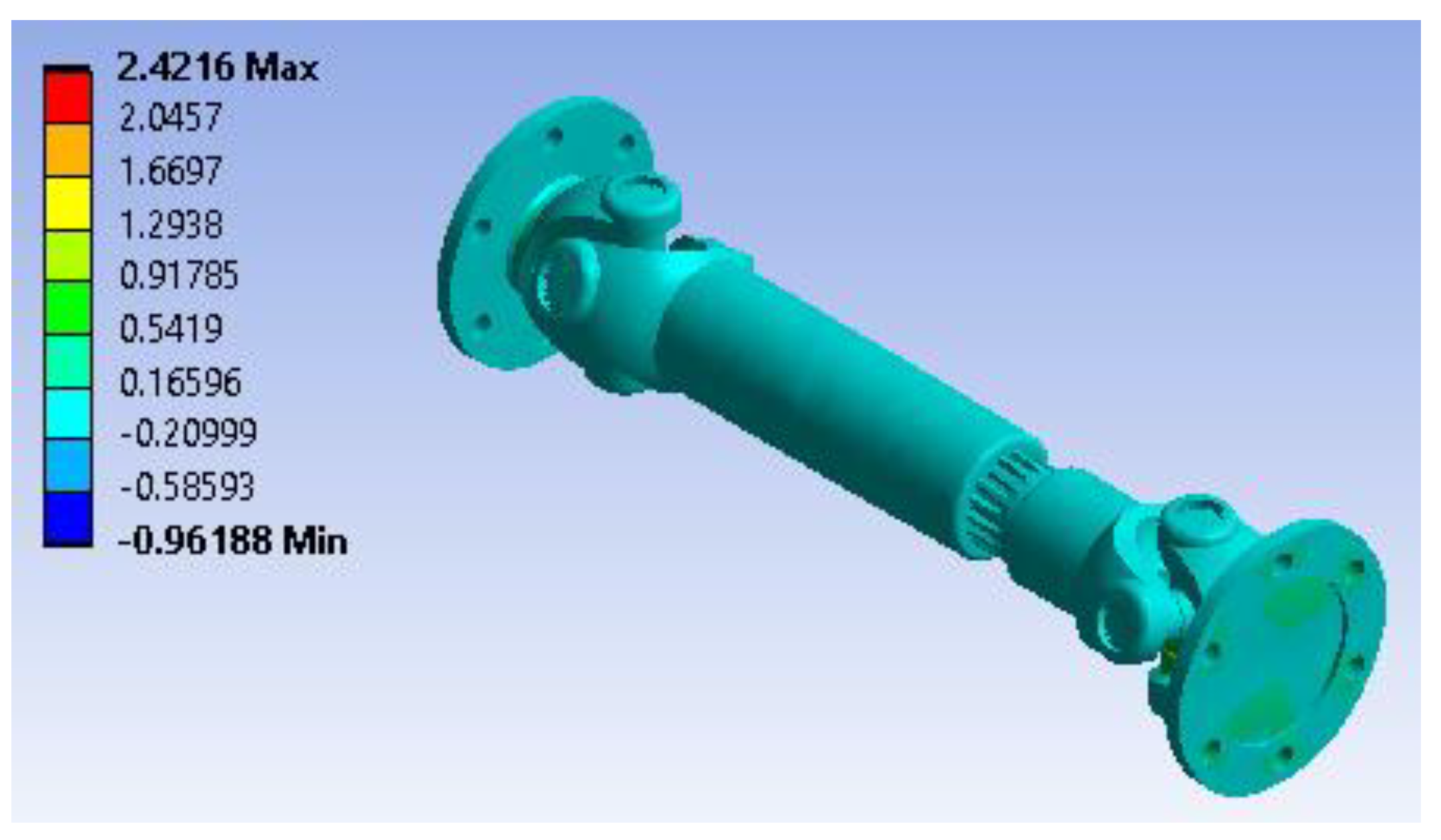

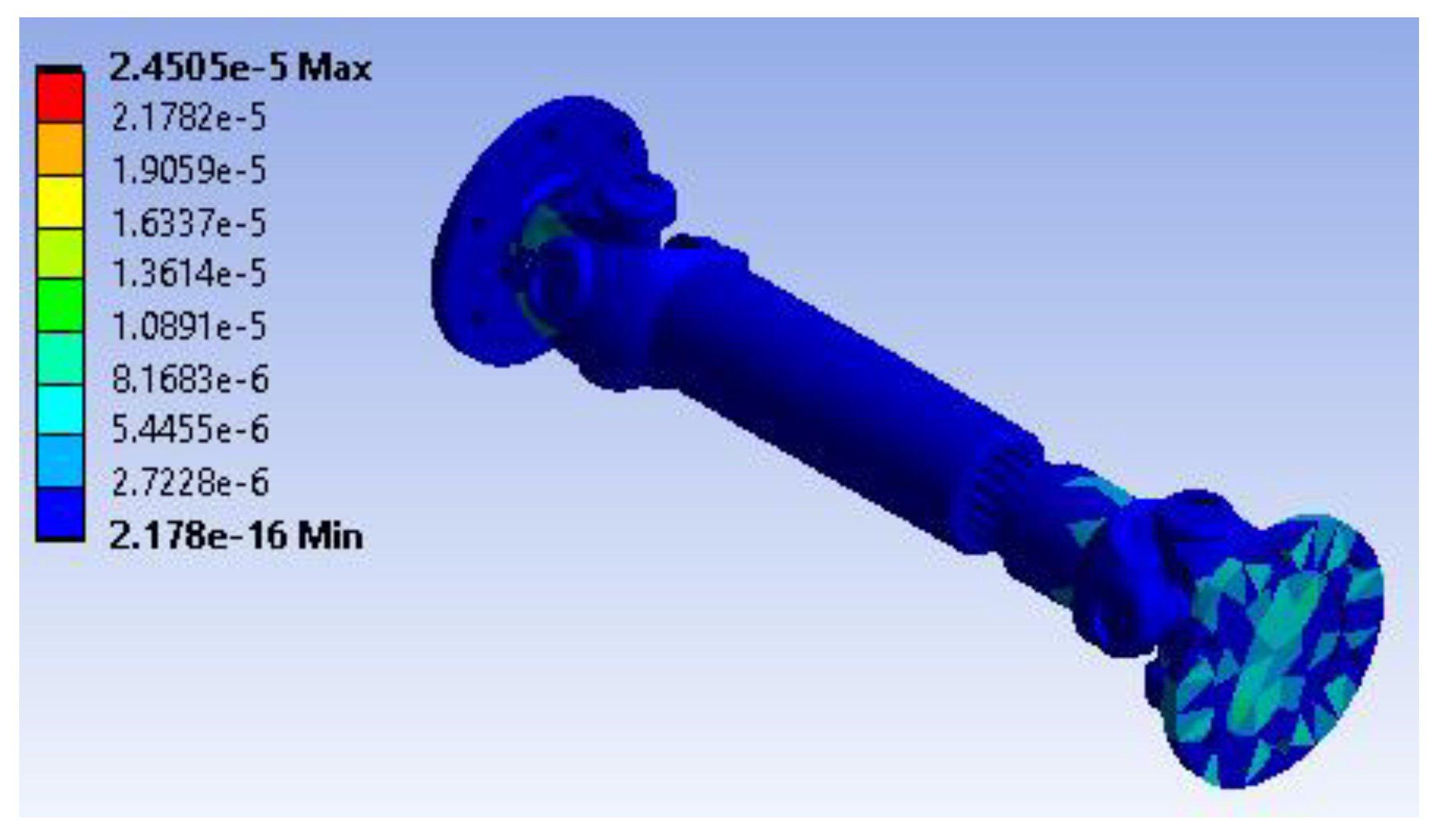

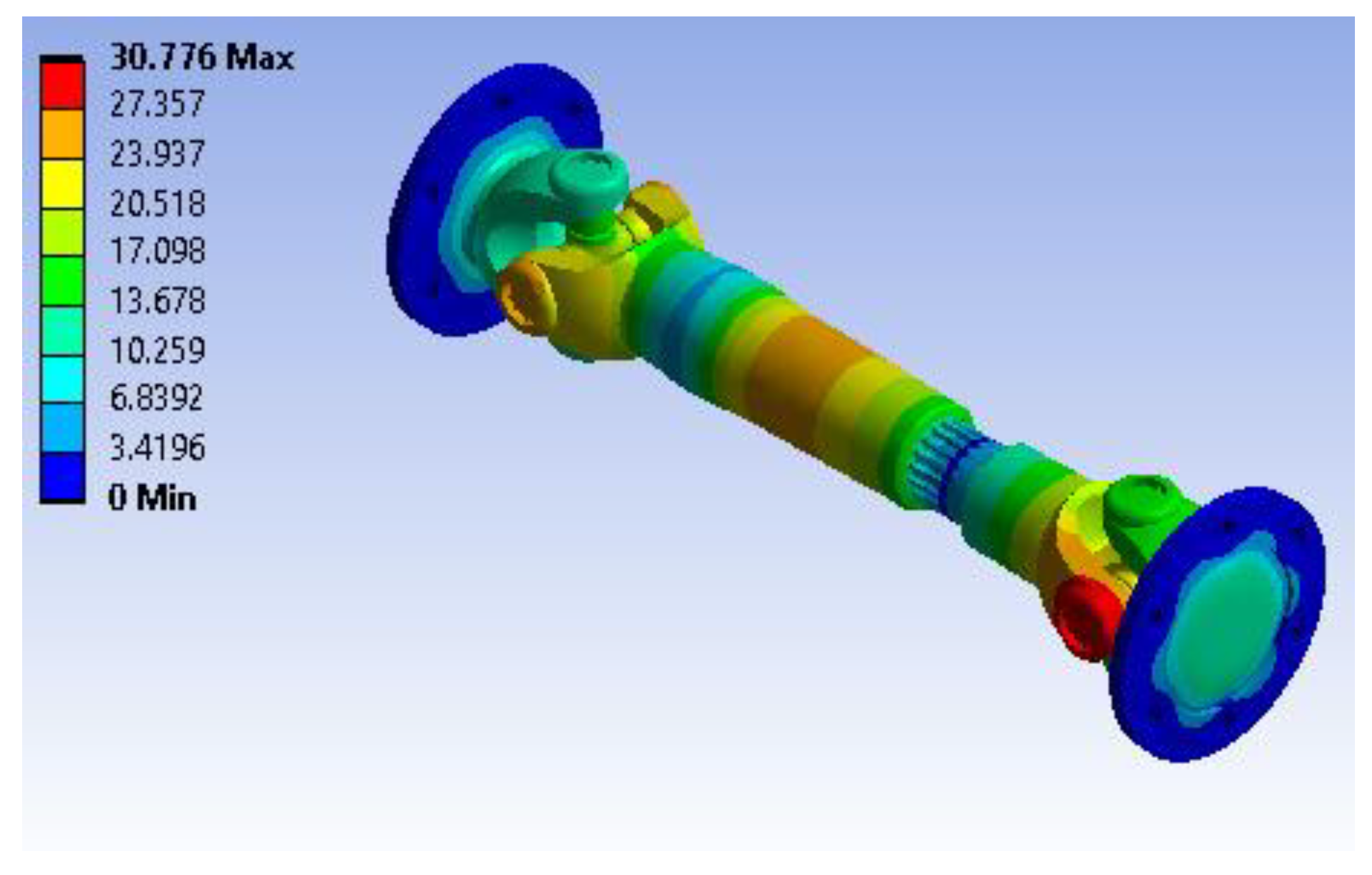

Figure 13 presents the total deformation of the shaft coupling assembly under the applied loads and boundary conditions. The maximum deformation is approximately 0.00037233 m (0.372 mm), occurring at the end where the torsional moment is applied. The deformation gradually decreases along the shaft, with the fixed support areas, shown in blue, experiencing virtually no displacement. The small magnitude of this deformation indicates that the coupling exhibits good stiffness under the imposed torsional and rotational loads.

Figure 14 illustrates the shear stress distribution on the XY plane across the assembly. The most highly stressed areas, highlighted in red, exhibit a maximum shear stress of about 0.57184 MPa, concentrated near the flange and universal joint region. Conversely, most other areas, shown in green and blue, experience much lower shear stresses, as low as approximately -0.54894 MPa. These results highlight that the highest shear stresses occur around geometric transitions and connection points, making them critical zones for structural integrity.

Figure 15 depicts the maximum principal stress variation throughout the model. The peak principal stress is approximately 2.4216 MPa, appearing at the interface between the shaft and its flange. Lower stress regions, indicated by blue and green, record values as low as -0.96188 MPa, suggesting that most of the assembly operates well within material capacity. These variations help identify stress concentration points that may require design optimization or material reinforcement to ensure long-term durability.

Figure 16 presents the strain energy distribution across the assembly. The structure absorbs up to 2.4505e-5 J in strain energy, with the most energy stored in the critical loading region shown in red. Other components exhibit much lower energy densities, as indicated by blue tones approaching the minimum value of approximately 2.1788e-16 J. This energy map underscores the areas under higher mechanical work, which correlates with increased stress and deformation, and can inform future enhancements to improve load sharing and optimize material utilization.

- 3.

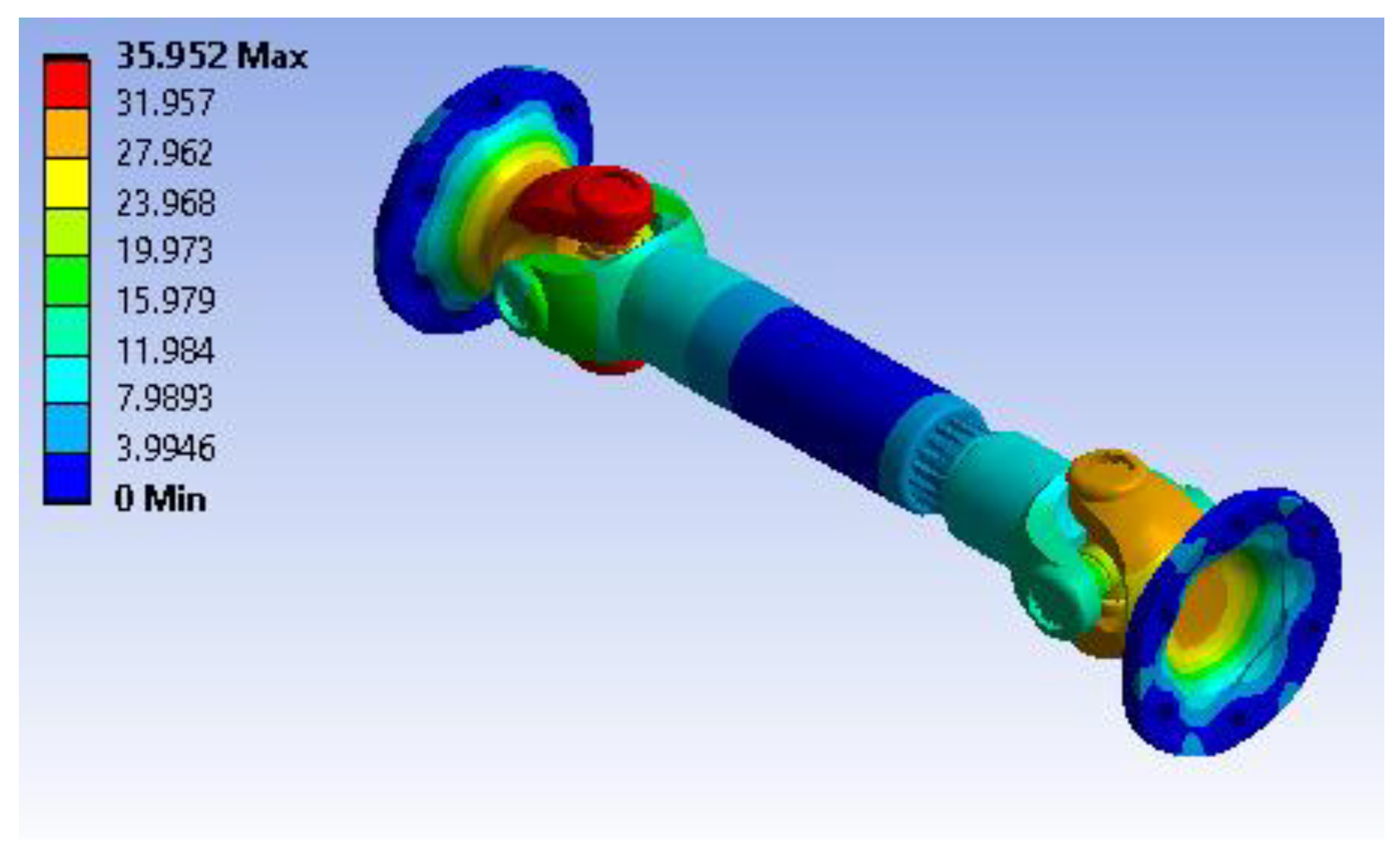

Structural analysis coating E-Glass Polyester steel

As a result of analyses, the obtained E-Glass Polyester steel which is listed in table 3 and has a coating layer at 0.5 mm on surface of steel, is used as conventional two-piece cardan shaft material [

14,

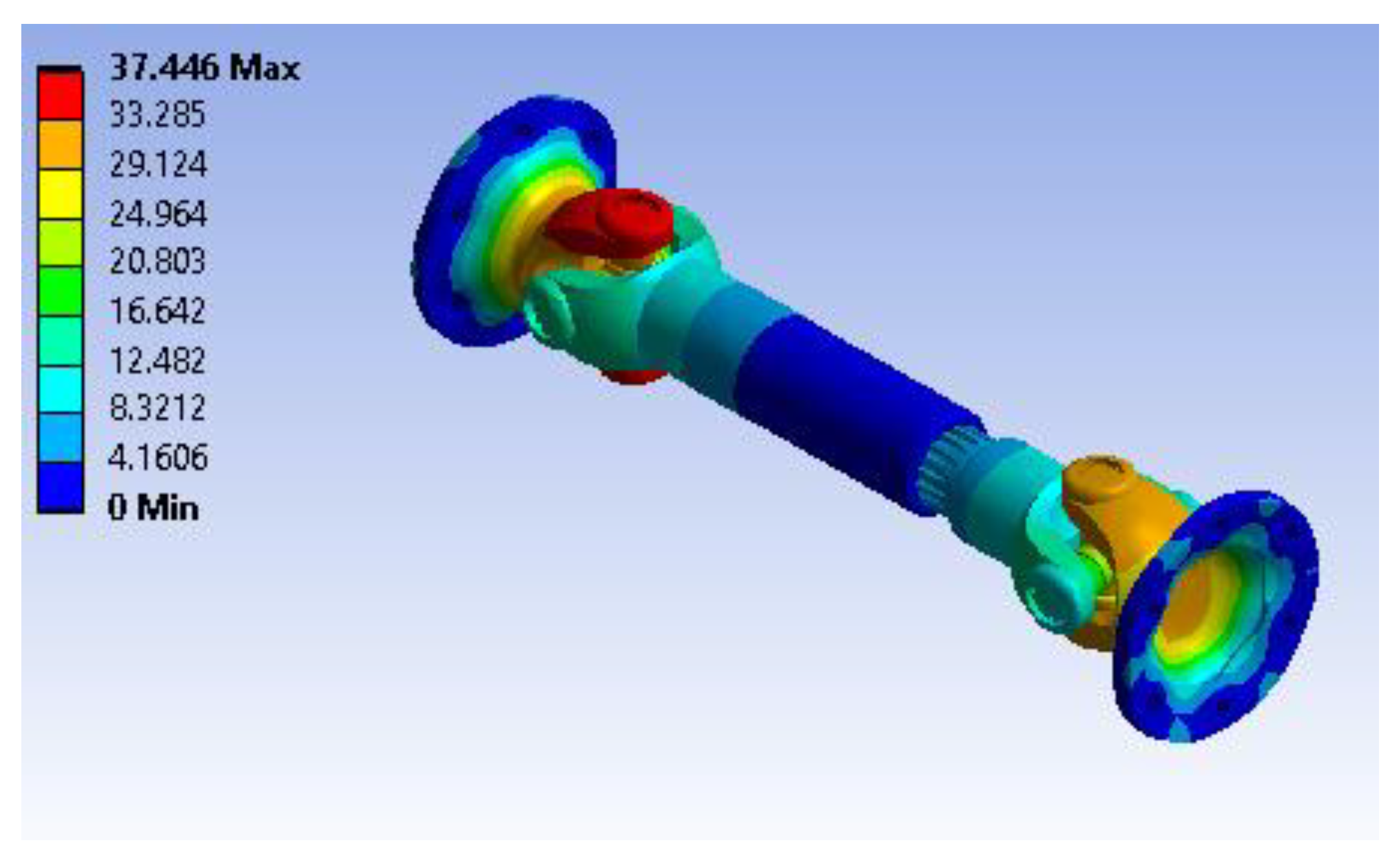

15]. The structural analysis simulation results are shown in Figures (17, 18, 19 and 20).

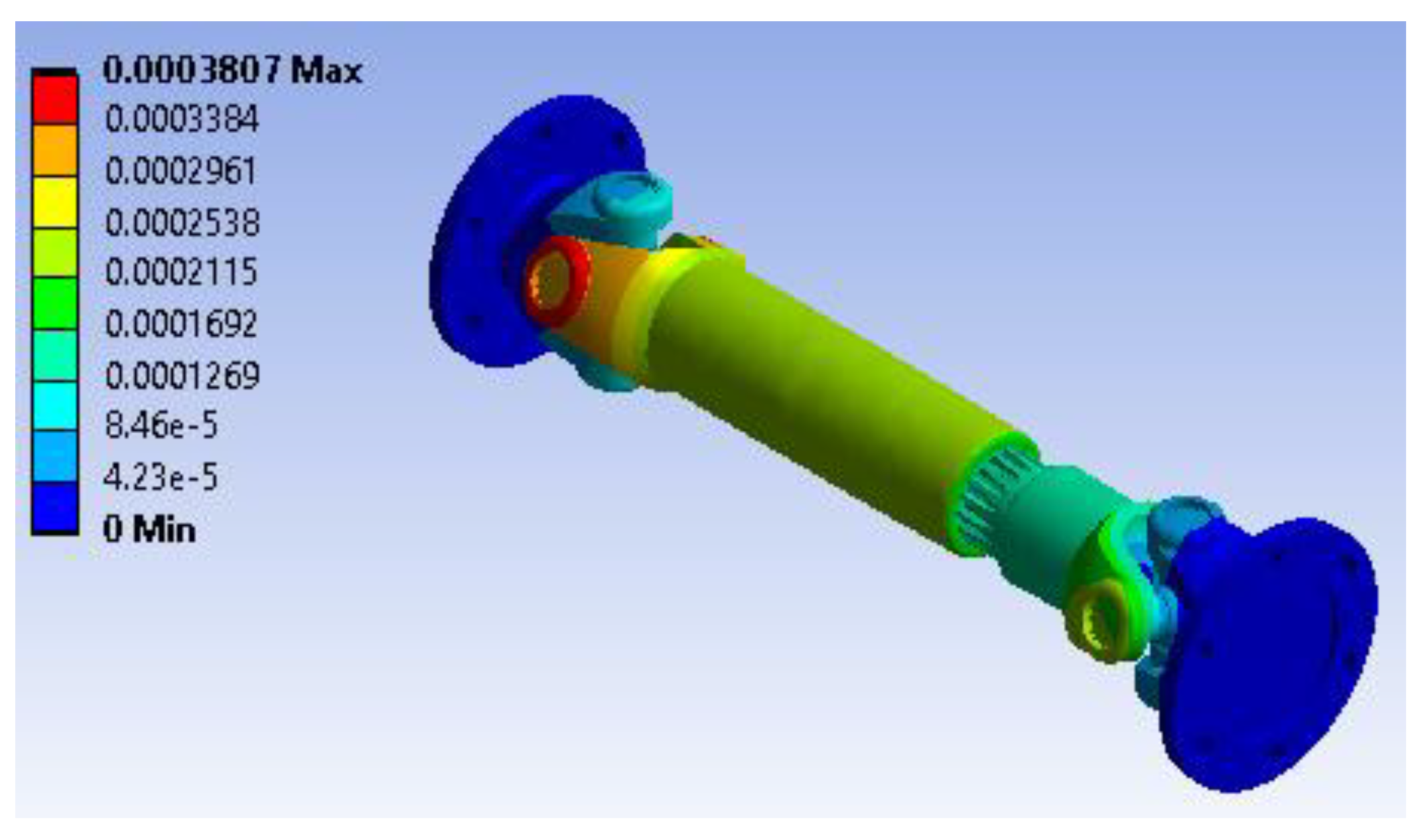

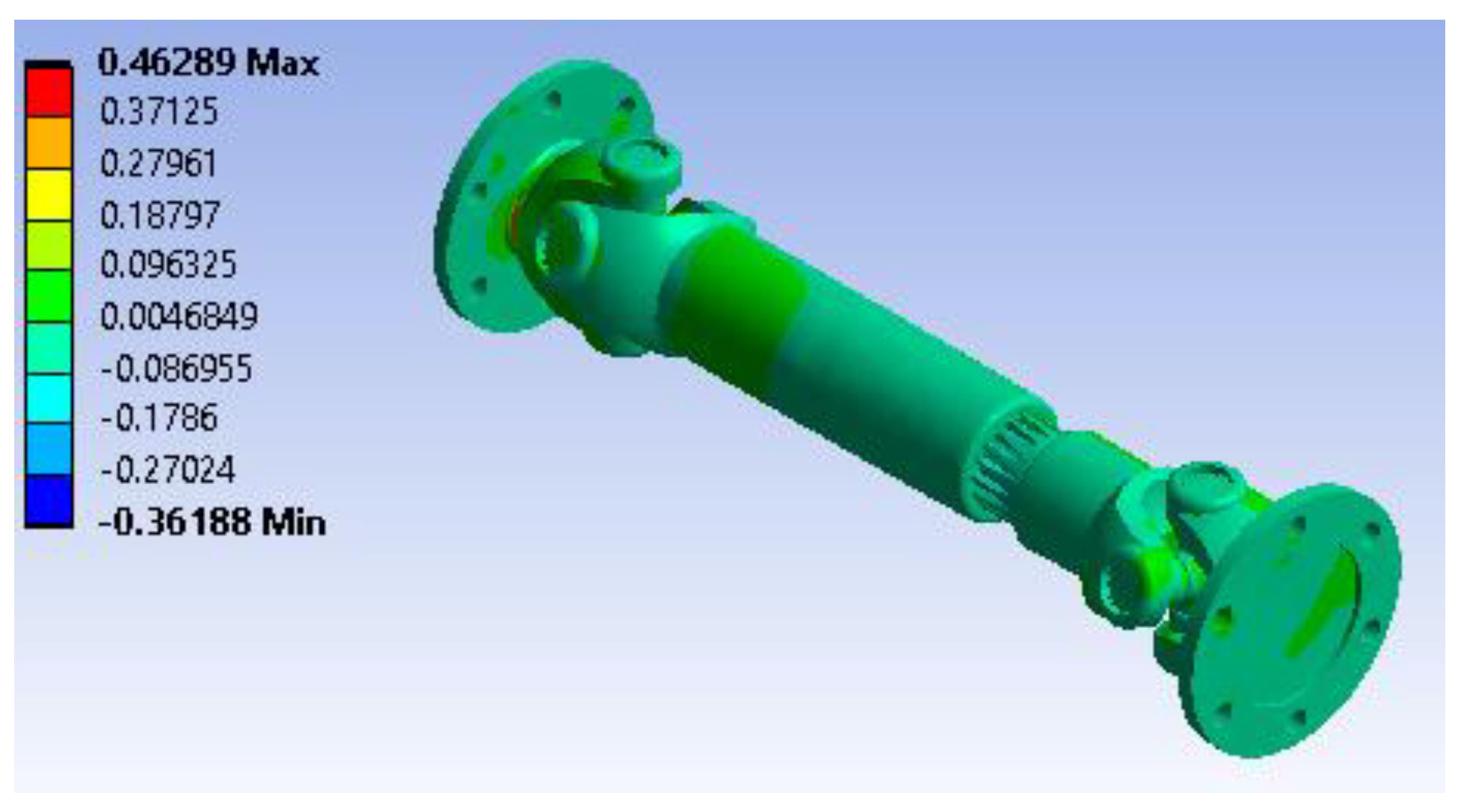

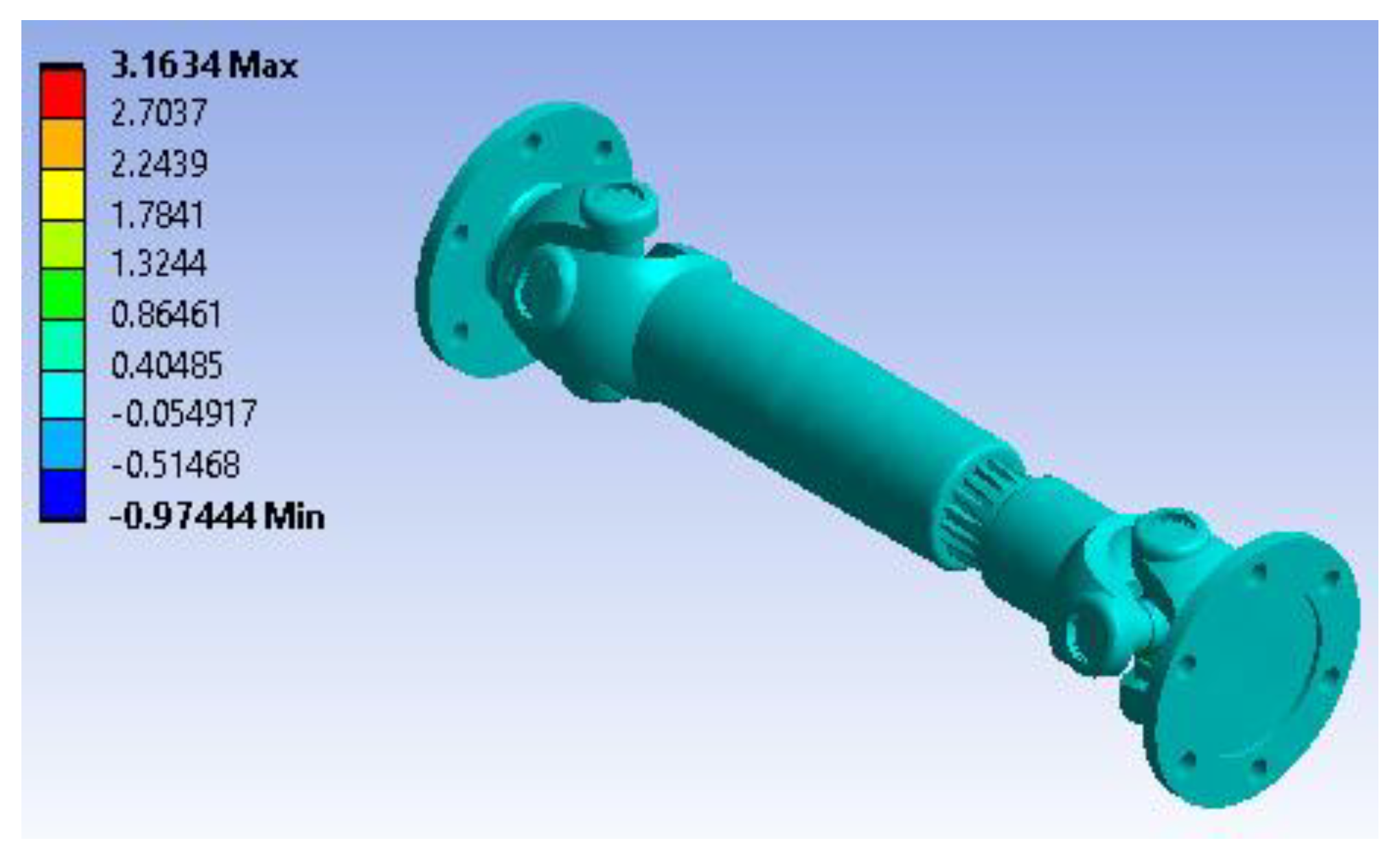

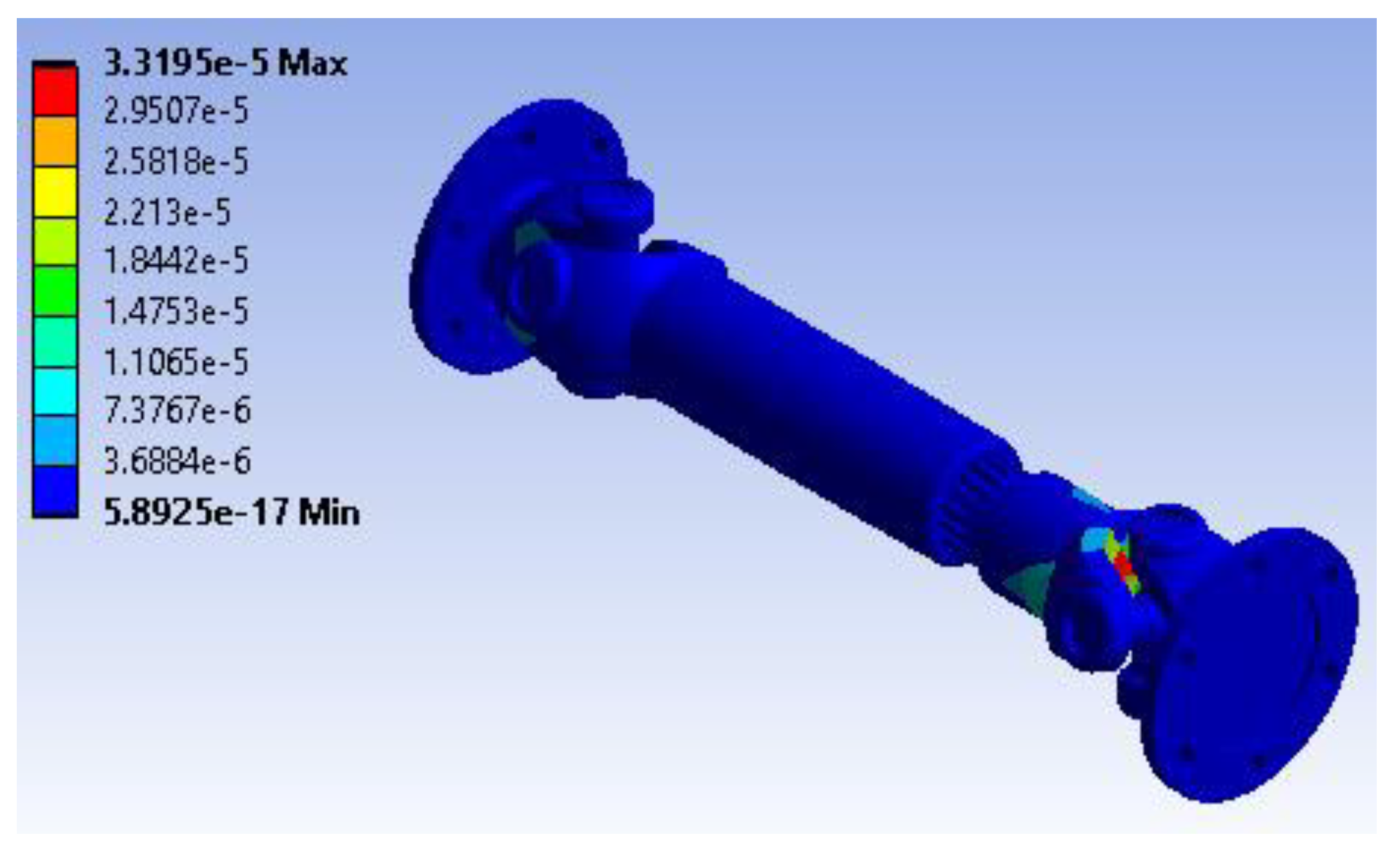

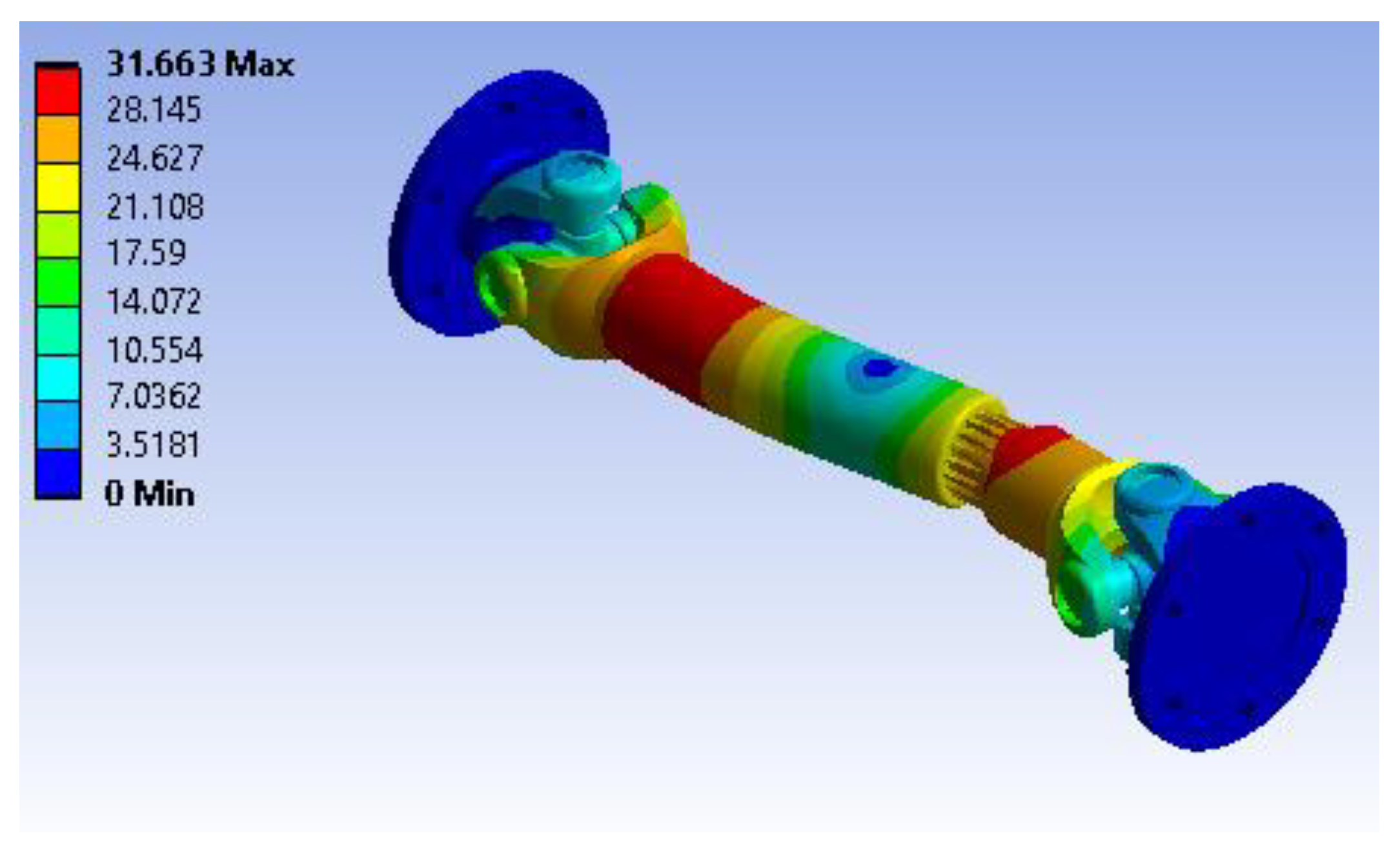

Figure 17 illustrates the total deformation of the shaft coupling assembly under the specified loading and boundary conditions. The maximum deformation reaches approximately 0.0003807 m (0.381 mm), appearing at the end where the torsional moment and rotational velocity are applied. The color gradient indicates the gradual reduction in displacement moving toward the fixed supports, which exhibit essentially zero deformation. The small magnitude of this deformation confirms that the coupling is sufficiently rigid under the working loads.

Figure 18 depicts the shear stress distribution on the XY plane across the assembly. The most highly stressed region experiences a peak shear stress of about 0.46289 MPa, highlighted in red near the flange and joint areas. In contrast, the blue and green regions show much lower shear stress levels, with the lowest value approximately -0.36188 MPa. This variation suggests that the load transfer is concentrated at the connecting areas, making them critical for evaluating shear capacity and ensuring long-term durability under cyclic torsional loads.

Figure 19 shows the maximum principal stress variation across the shaft coupling assembly. The highest principal stress reaches approximately 3.1634 MPa, appearing near the flange and at locations where geometric transitions cause stress concentrations. The most lightly stressed areas register negative principal stresses as low as -0.97444 MPa, indicating compression. These results highlight the need to ensure the material's yield strength is adequately higher than the peak stresses for safe and reliable operation.

Figure 20 presents the strain energy distribution throughout the assembly, with a peak value of around 3.3195e-5 J concentrated where the most deformation and stress occurs. The remaining components show considerably lower strain energy levels, approaching the minimum value of approximately 5.8925e-17 J in blue, indicating negligible energy absorption. This energy map is important as it reflects the locations most susceptible to material strain under torsional and rotational loads and can help guide any design enhancements to improve performance and fatigue resistance.

- 4.

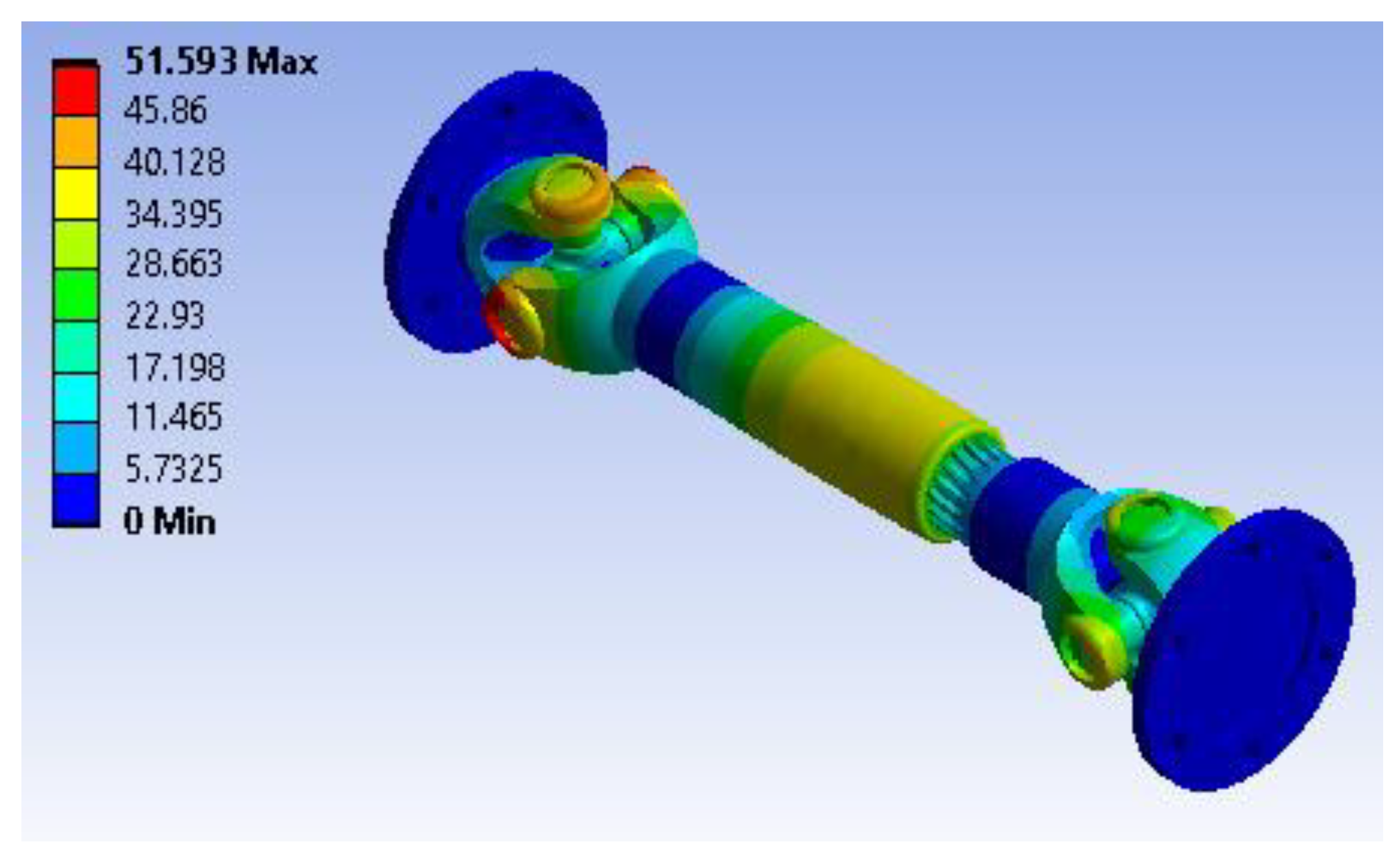

Structural analysis Stainless-steel

As a result of analyses, the obtained stainless-steel which is listed in table 3, is used as conventional two-piece cardan shaft material [

15,

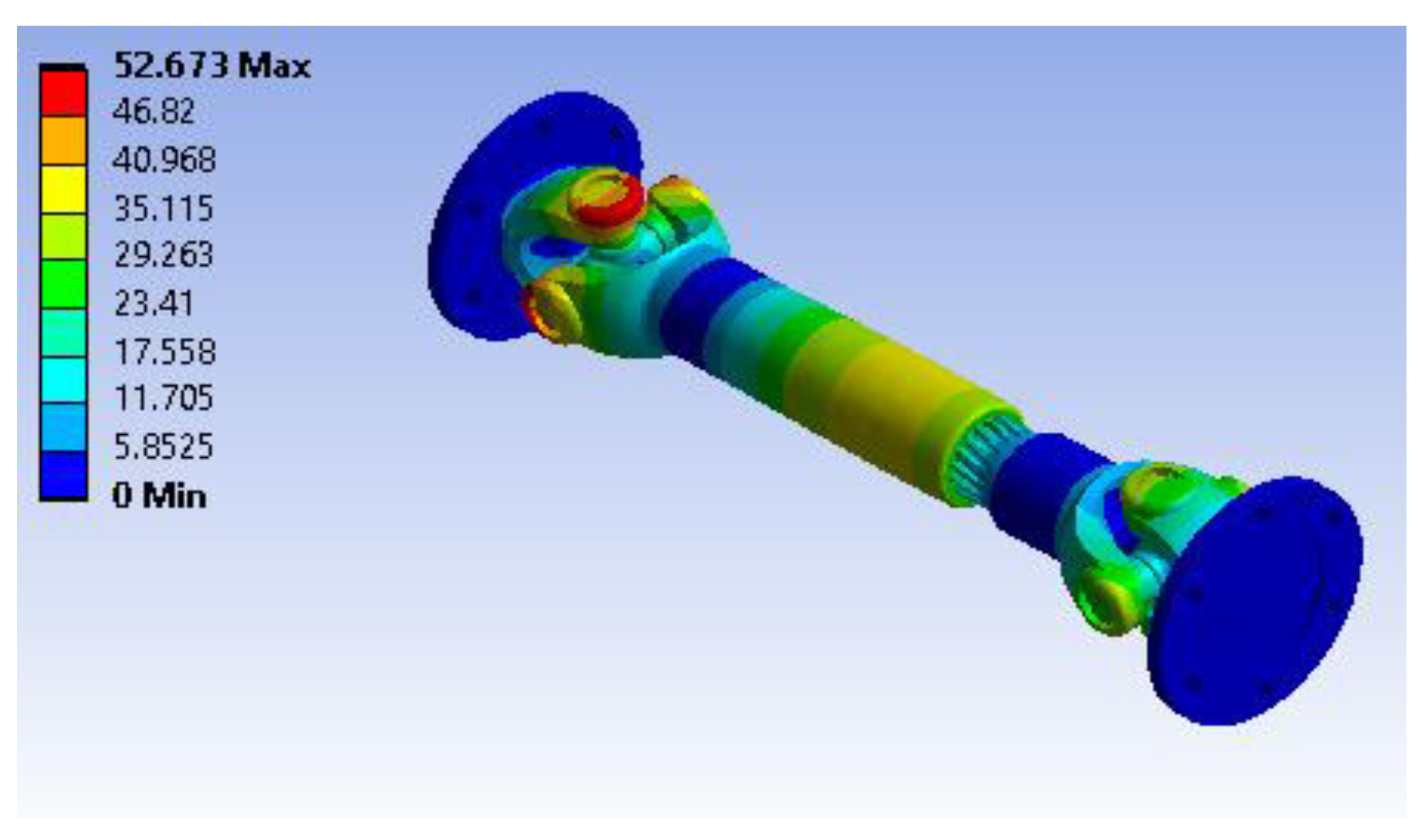

16]. The structural analysis simulation results are shown in figure (21, 22, 23 and 24).

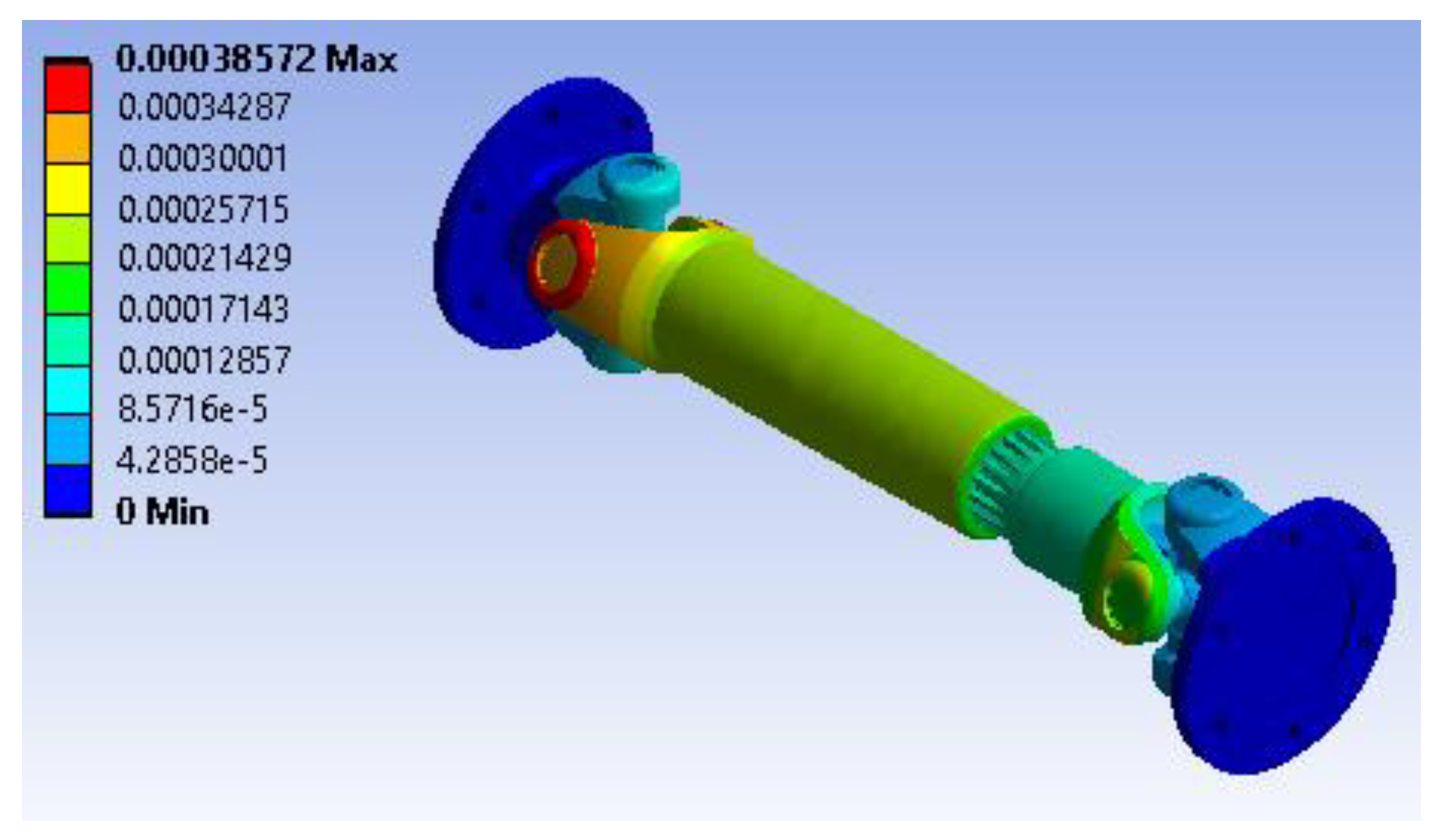

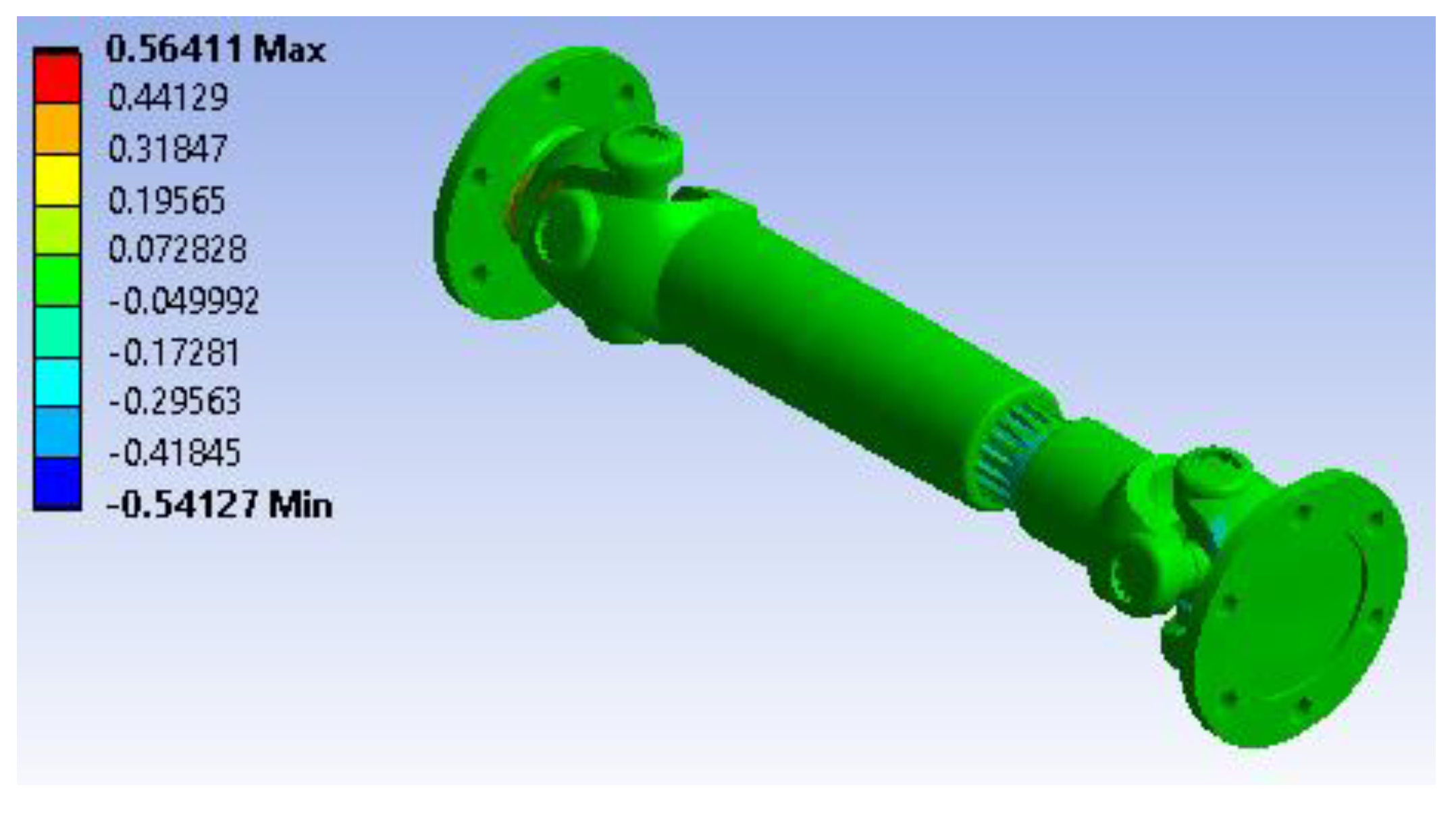

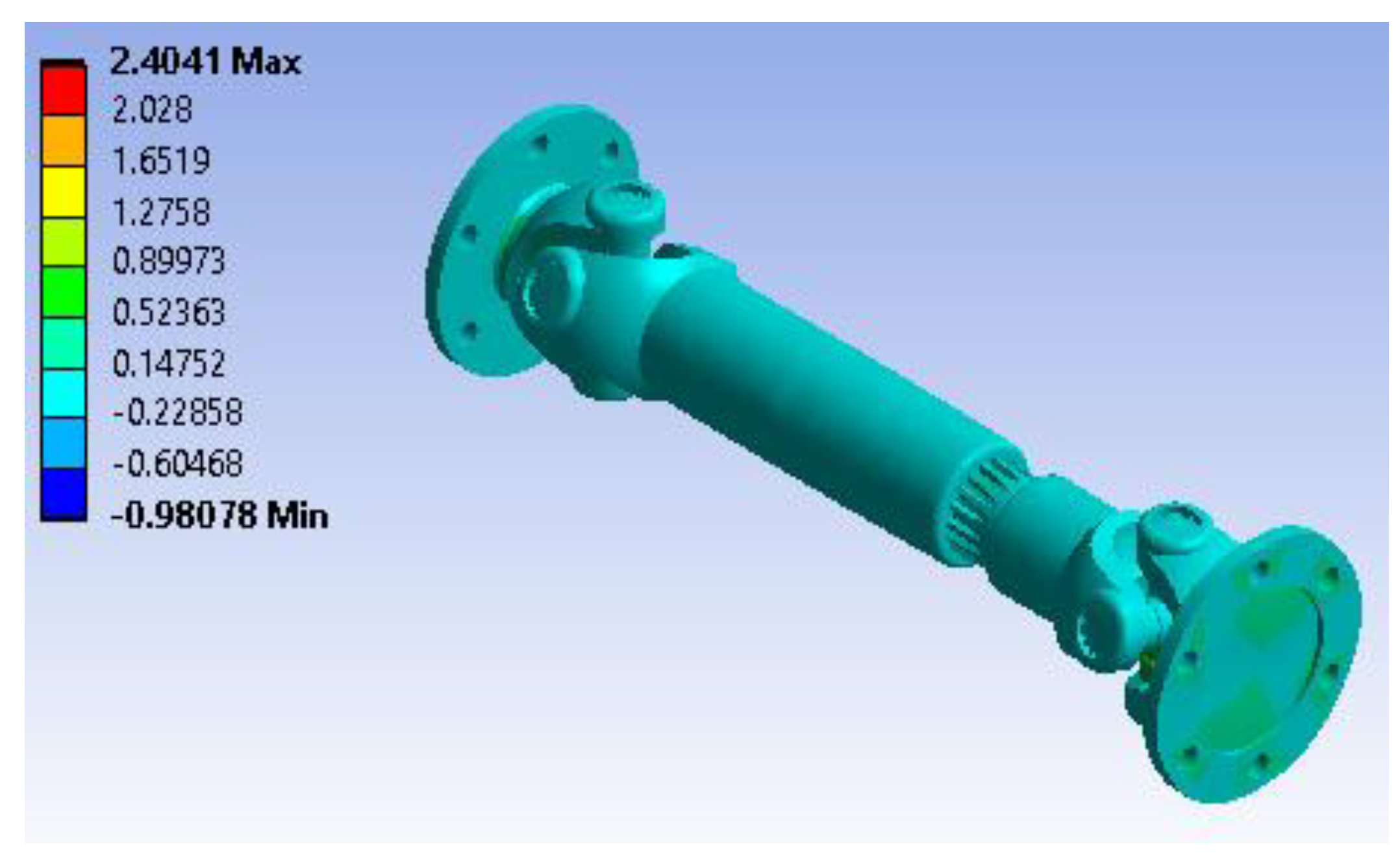

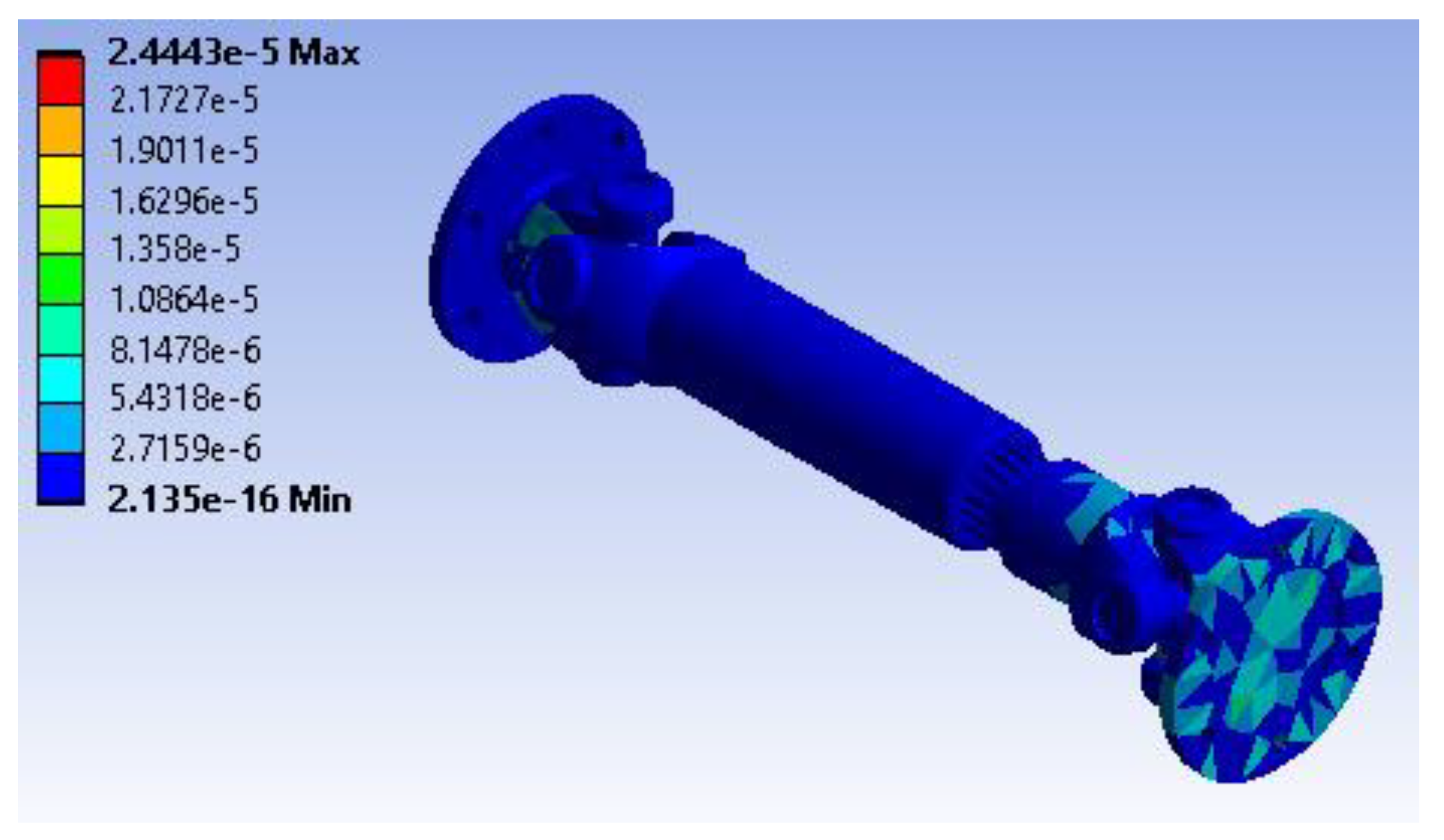

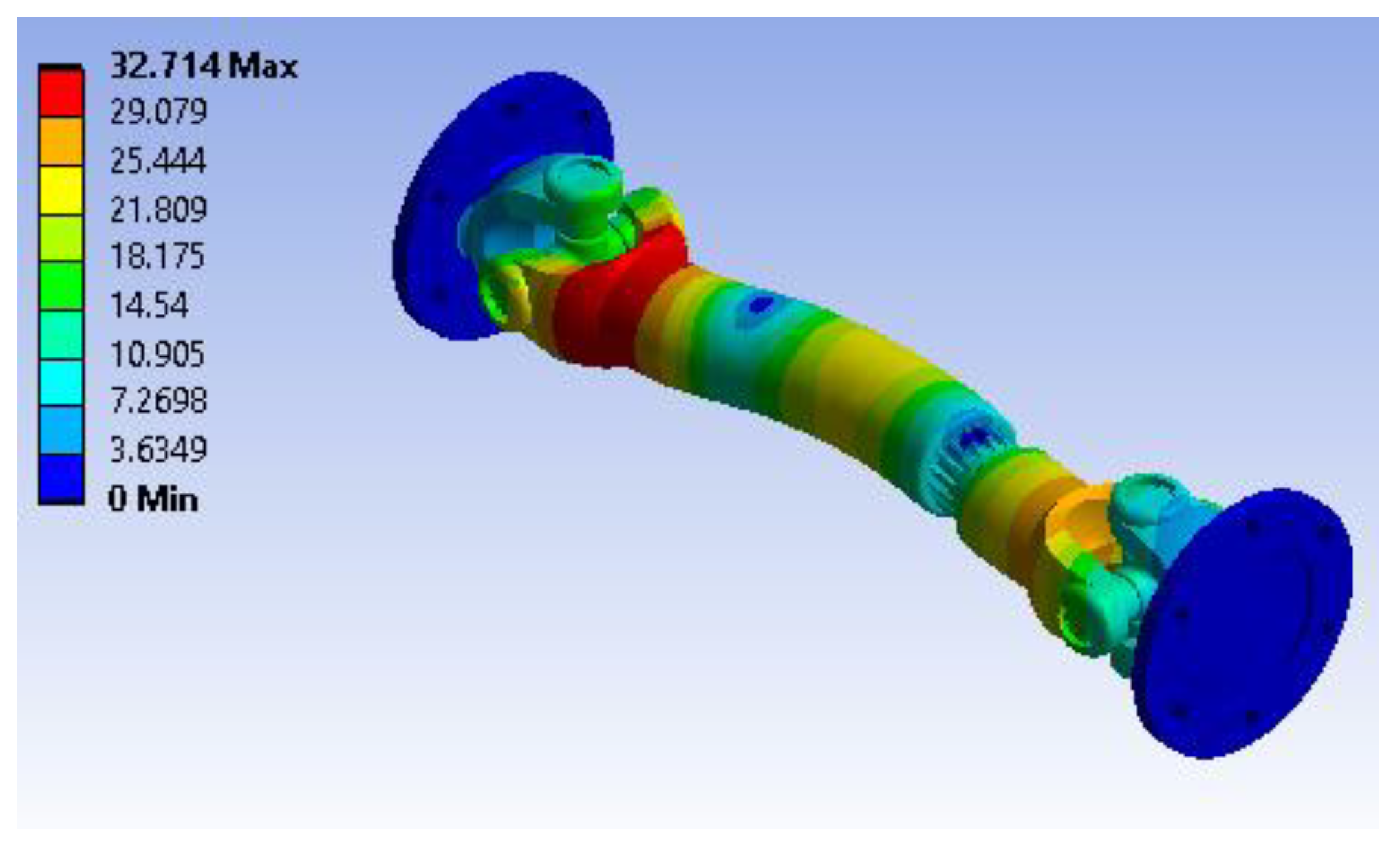

Figure 21 illustrates the total deformation of the two-piece cardan shaft made from stainless steel under the specified loads and supports. The maximum deformation is approximately 0.00038572 m (0.386 mm), observed at the region near the loading end where torsional and rotational loads have the most influence. The deformation gradually decreases toward the fixed supports, reaching essentially zero at the blue-colored regions representing the constrained sections. This small deformation value indicates that the material and geometry provide sufficient stiffness under operating conditions.

Figure 22 depicts the shear stress distribution in the XY plane. The most significant shear stress is concentrated around the flange and universal joint regions, with a peak value of approximately 0.56411 MPa. This is evident from the yellow-green coloration, while most other parts show lower shear stresses approaching a minimum of -0.54127 MPa as indicated by the green and blue colors. These results imply that stress transfer is more pronounced at geometrical transitions and attachment points, making these critical locations for further consideration in design or life estimation.

Figure 23 illustrates the maximum principal stress variation across the shaft coupling. The peak principal stress reaches approximately 2.4041 MPa, appearing mostly around the flange region and at the shaft connections. This value is well distributed across most of the shaft body as lighter blue and green tones, with the lowest value around -0.98078 MPa under compression. This distribution indicates that, under the applied loads, the component remains well within typical material limits for stainless steel, supporting its safe use in practice.

Figure 24 presents the strain of energy distribution across the assembly. The highest strain energy is concentrated at the most loaded sections, especially where the moment is introduced, with a value of 2.4443e-5 J. The blue-shaded areas reflect minimal strain energy approaching 2.135e-16 J, suggesting very little energy absorption in those sections. These findings show that most of the strain energy is localized to the shaft region where deformation is more prominent, further confirming that the design is structurally sound under the specified conditions.

- 5.

Structural analysis Hardox 400

As a result of analyses, the obtained Hardox 400 which is listed in table 3, is used as conventional two-piece cardan shaft material [

16]. The structural analysis simulation results are shown in figure (25, 26, 27 and 28).

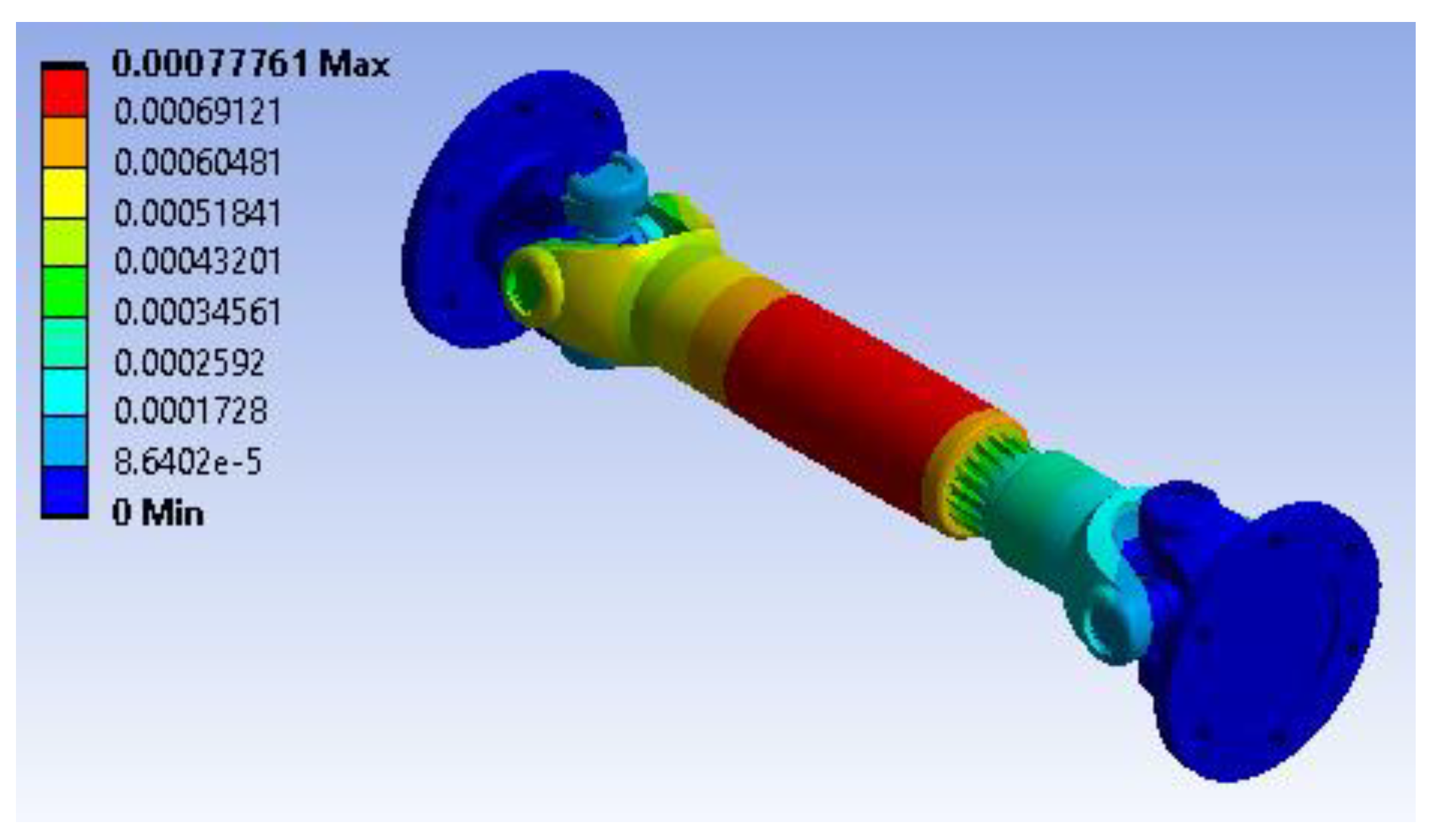

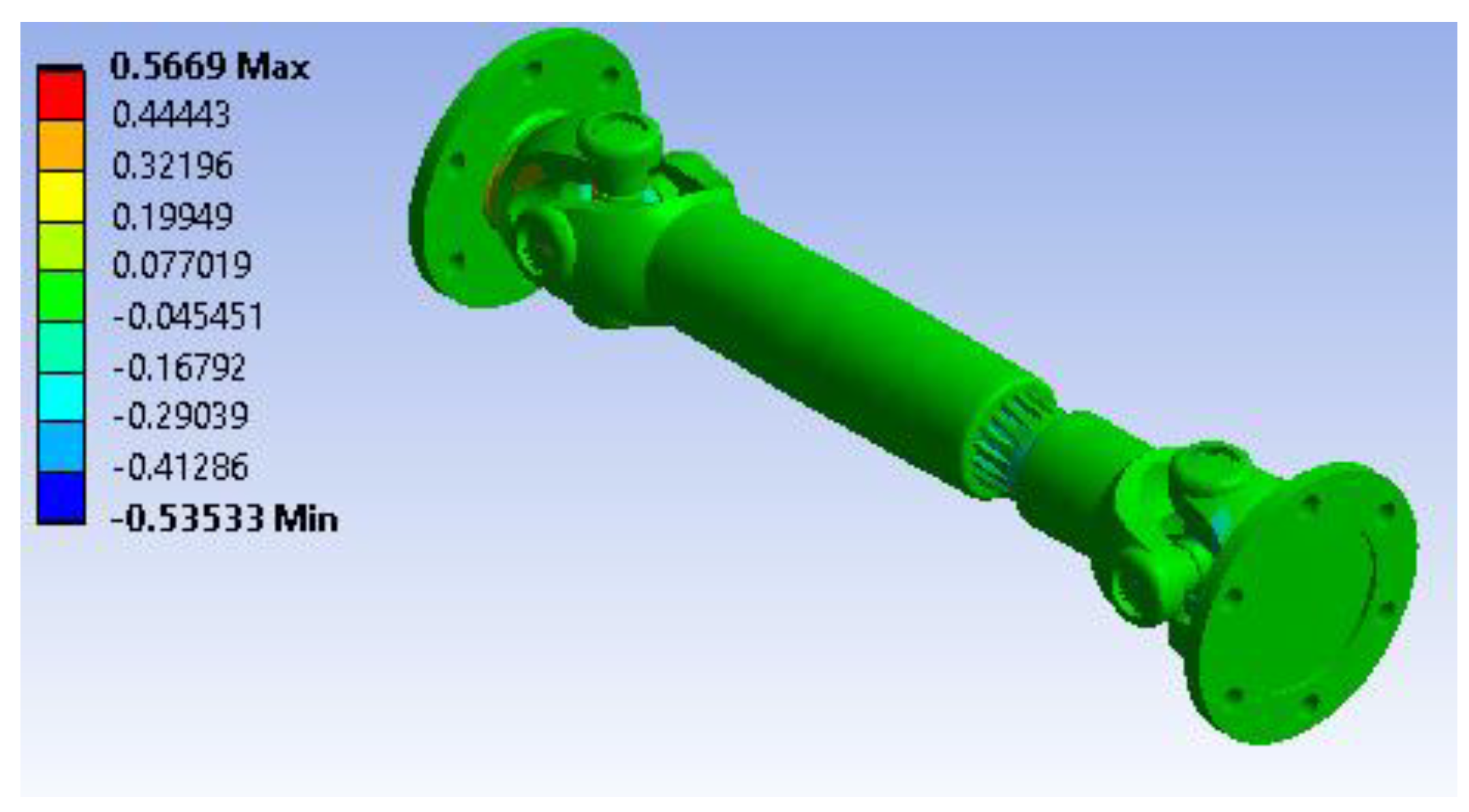

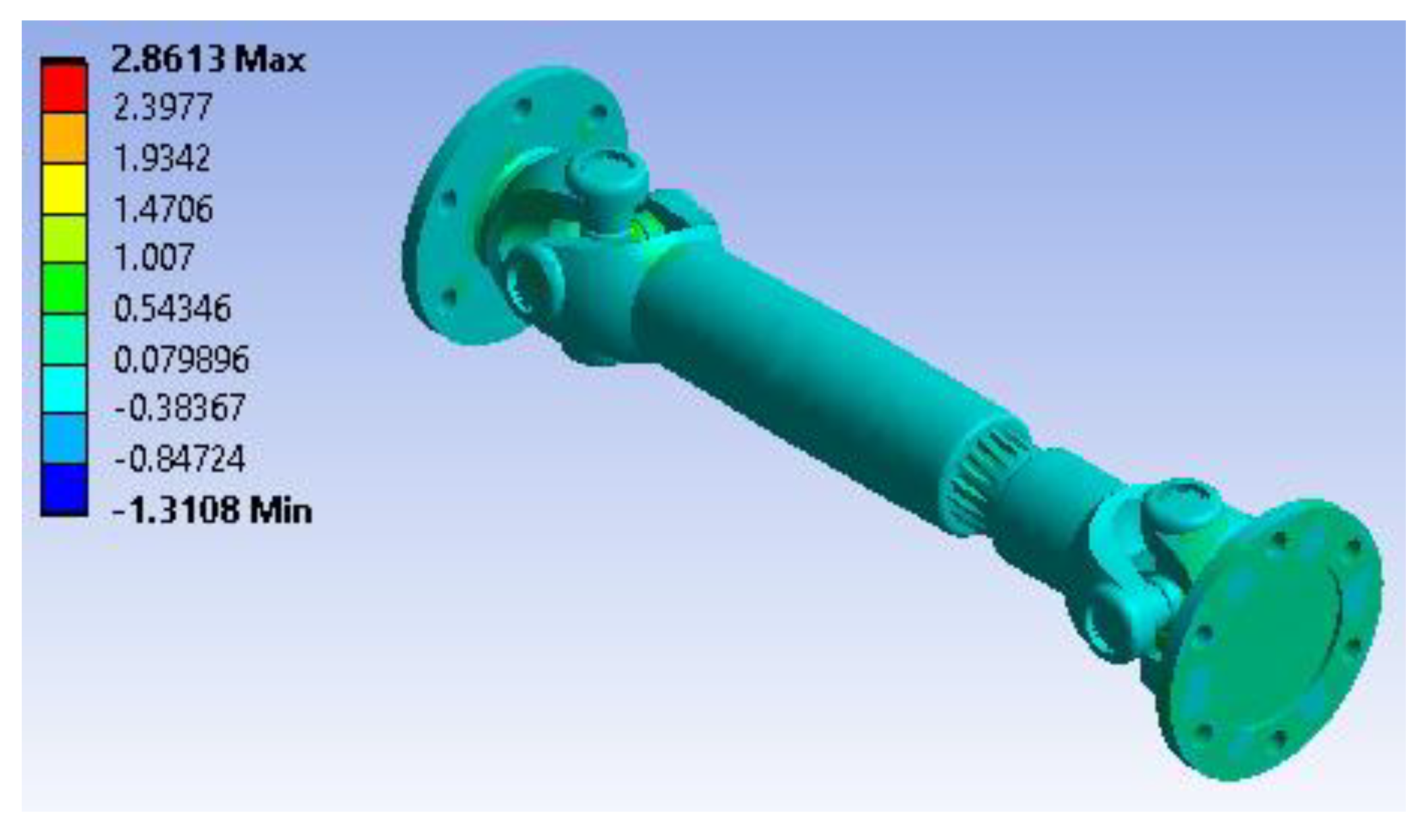

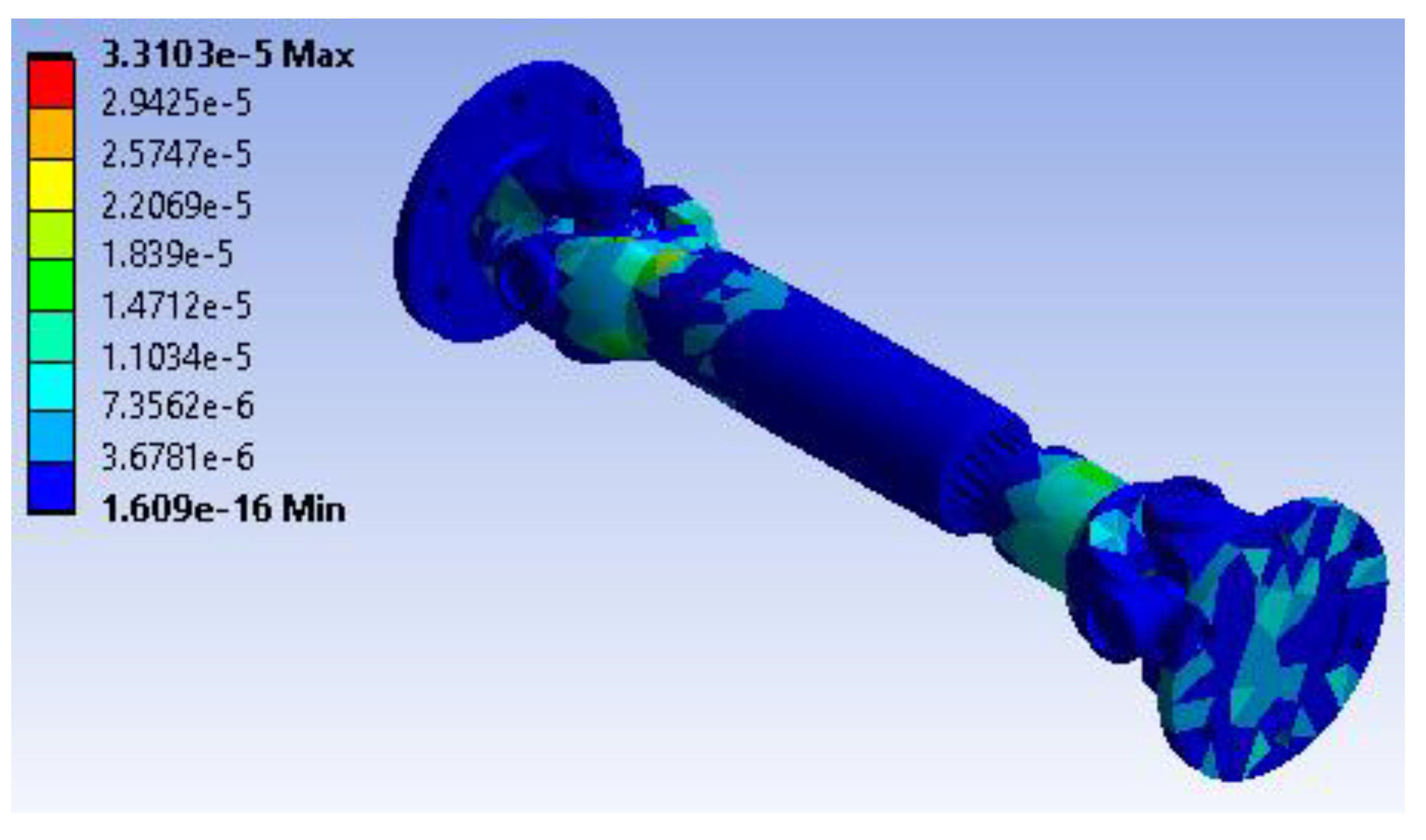

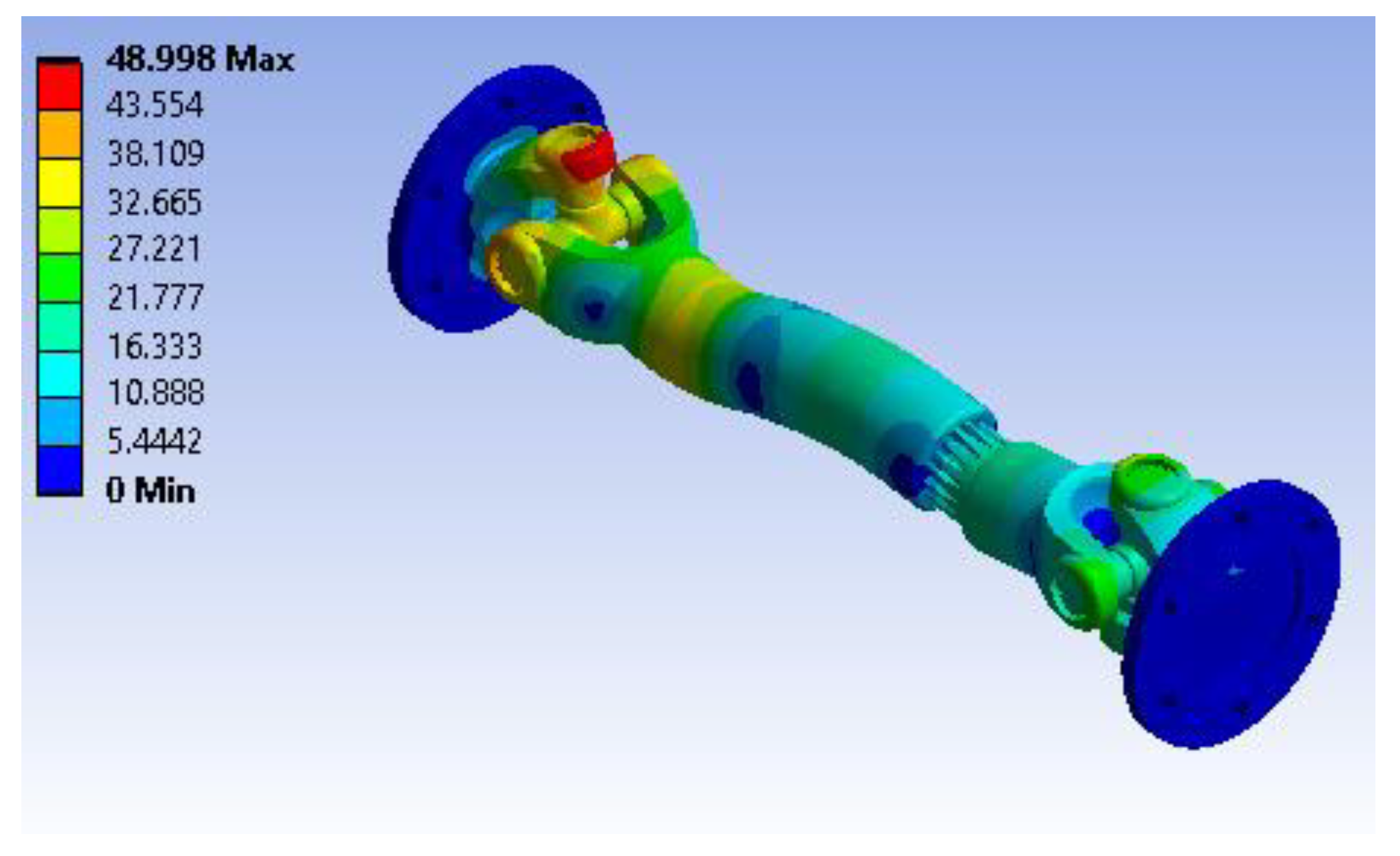

Figure 25 illustrates the total deformation of the two-piece cardan shaft constructed using Hardox 400 under the given loading and boundary conditions. The maximum deformation is approximately 0.00077761 m (0.778 mm), which occurs near the center region of the shaft where the torsional and rotational loads are most significant. The color gradient clearly shows that the fixed supports (blue areas) experience negligible displacement, confirming their constraint, while the shaft mid-section displays the highest displacement as indicated by the red areas. This magnitude of deformation is modest, suggesting the material and design provide sufficient stiffness under the specified loading.

Figure 26 presents the shear stress distribution on the XY plane across the shaft assembly. The most significant shear stress, approximately 0.5669 MPa, is concentrated around the flanges and coupling joints. Away from these regions, the shear stress drops considerably, reaching a minimum of approximately -0.5533 MPa, as indicated by green and blue colors across most of the shaft body. The result highlights these transitional areas as critical stress points, which is typical for assemblies where abrupt changes in geometry or load transfer occur.

Figure 27 depicts the maximum principal stress variation across the entire assembly. The highest principal stress reaches approximately 2.8613 MPa, located around the flange connections and the shaft interface — spots where bending and torsion create high tensile and compressive stresses. Other parts of the shaft show relatively lower stress intensities (as low as -1.3108 MPa), indicating uniform load sharing along most of its length. This range of stresses is well within the capacity of Hardox 400, confirming the shaft’s structural adequacy under operating loads.

Figure 28 illustrates the strain energy distribution within the shaft. The maximum strain energy value is approximately 3.3103e-5 J, concentrated near the critical coupling areas subjected to both torsional and rotational loads. Elsewhere, strain energy values drop sharply to 1.609e-16 J or close to zero, indicating minimal energy absorption where deformation and stresses are low. The energy map confirms that most of the strain energy is concentrated where the most deformation and stress occur, making those areas the most significant contributors to the shaft's flexibility under load.

In addition, by comparing the results with each material as shown in table 4, it was shown that the hardox 400 material is characterized by high hardness and resistance to bending and stresses. The material of hardox 400 can also be used in the manufacture of cardan shafts, as its thickness is less than that of steel and offers high performance and efficiency. The results also explain the shear stress distribution on the XY plane, the shear stress distribution, the total deformation, and the strain energy distribution.

Table 4.

Structural analysis results comparison.

Table 4.

Structural analysis results comparison.

| Materials |

Results |

| Shear Stress (MPa) |

Max. principal Stress (MPa) |

| Steel |

Min. |

-0.35725 |

-1.0694 |

| Max. |

0.4662 |

3.1133 |

| HS-Carbon Epoxy |

Min. |

-0.54894 |

-0.96188 |

| Max. |

0.57184 |

2.4216 |

| E-Glass Polyester |

Min. |

-0.36188 |

-0.97444 |

| Max. |

0.46289 |

3.1634 |

| Stainless Steel |

Min. |

-0.54127 |

-0.98078 |

| Max. |

0.56411 |

2.4041 |

| Hardox 400 |

Min. |

-0.53533 |

-1.3108 |

| Max. |

0.5669 |

2.8613 |

| Materials |

Results |

| Total Deformation (mm) |

Strain Energy (mJ) |

| Steel |

Min |

0.0 |

6.6548e-017 |

| Max |

3.9813e-004 |

3.5046e-005 |

| HS-Carbon Epoxy |

Min |

0.0 |

2.178e-016 |

| Max |

3.7233e-004 |

2.4505e-005 |

| E-Glass Polyester |

Min |

0.0 |

5.8925e-017 |

| Max |

3.807e-004 |

3.3195e-005 |

| Stainless Steel |

Min |

0.0 |

2.135e-016 |

| Max |

3.8572e-004 |

2.4443e-005 |

| Hardox 400 |

Min |

0.0 |

1.609e-016 |

| Max |

7.7761e-004 |

3.3103e-005 |

| Materials |

Results |

| Equivalent Elastic Strain(mm/mm) |

Maximum Principal Elastic Strain(mm/mm) |

| Steel |

Min |

6.559e-009 |

-2.2875e-007 |

| Max |

1.248e-005 |

1.1984e-005 |

| HS-Carbon Epoxy |

Min |

3.263e-009 |

-2.2588e-007 |

| Max |

9.881e-006 |

9.5309e-006 |

| E-Glass Polyester |

Min |

1.129e-008 |

-1.8424e-007 |

| Max |

9.998e-006 |

1.1347e-005 |

| Stainless Steel |

Min |

5.086e-009 |

-2.2198e-007 |

| Max |

1.006e-005 |

9.387e-006 |

| Hardox 400 |

Min |

4.798e-009 |

-1.7786e-007 |

| Max |

1.190e-005 |

1.0494e-005 |

3.2. Modal Analysis

In order to determine the natural frequencies and mode shapes, simulation modal analysis was done. A cardan shaft's inherent frequency is determined by its material and geometric characteristics. Torque and speed boundary conditions are constant in modal analysis with varying materials. The cardan shaft transfers torque of 1250 N.mm while rotating at a maximum speed of 2000 rpm. Resonance chances increase with external excitation, therefore determining the natural frequency is essential [

17].

Figure 29 illustrates the first natural frequency mode shape of the cardan shaft made of steel. The natural frequency at this mode is 952.96 Hz, which is the lowest frequency at which the shaft will naturally tend to vibrate under dynamic loading. This mode is characterized by an overall bending deformation where the shaft and joints flex, making it a critical parameter to monitor during operation. Avoiding excitation close to this frequency is important to reduce the risk of resonance at low operating speeds.

Figure 30 depicts the sixth natural mode, corresponding to a frequency of 2618.7 Hz. In this mode shape, the shaft exhibits more complex deformation with multiple nodes along its length, indicating higher-order bending and torsional effects. This behavior can occur when higher-speed variations or harmonic vibrations match this frequency range, necessitating careful control of operating parameters to prevent resonance.

Figure 31 presents the twelfth mode shape of the cardan shaft, with a natural frequency of 7405.3 Hz. This mode exhibits intricate deformation with pronounced localized vibrations around the coupling and flange areas. The shaft segments show significant flexing and twisting along their lengths. Vibrations at this frequency and mode shape would typically not occur during standard operation due to the high frequency range, but they could be significant if the shaft is subjected to broadband excitation or transient shock loads.

Figure 32 illustrates the sixteenth natural mode, corresponding to the highest frequency among these results at 8802.3 Hz. This mode is highly complex with numerous points of inflection, demonstrating intricate torsional and flexural deformations across the entire assembly. The deformation is more concentrated at specific features like the flange and universal joints, which may act as vibration amplifiers. Understanding this mode is especially vital for predicting dynamic responses in extreme cases or during testing to ensure long-term reliability.

- 2.

Modal analysis coating HS-Carbon Epoxy steel

Figure 33 illustrates the first natural mode shape of the cardan shaft coated with HS-carbon epoxy steel. The natural frequency of this mode is approximately 997.52 Hz, which is close to the fundamental frequency observed in the plain steel shaft. The mode shape demonstrates simple bending behavior with a single curvature across the shaft length. This relatively low frequency indicates that the shaft is most vulnerable to resonance at this fundamental frequency if subjected to periodic excitations near this range during rotation.

Figure 34 presents the sixth natural mode, which corresponds to a frequency of 2598.3 Hz. The deformation in this mode is more complex, with multiple nodes and antinodes distributed along the shaft. The flange and coupling areas show greater flexing and twisting due to localized stiffness variations introduced by the coating. This higher-order mode indicates more intricate vibration shapes under higher-speed operation and emphasizes the influence of material layering on the dynamic stiffness of the shaft.

Figure 35 depicts the twelfth natural mode at a frequency of 7565.7 Hz. This mode shape features even more intricate deformation patterns with multiple sections of the shaft and joints vibrating with different amplitudes. The increased complexity is evident by the numerous inflection points that appear across the shaft, especially around the joints and flange connections. Understanding these higher-order modes is important for identifying potential resonance or stress hotspots under impulsive or broadband dynamic loads.

Figure 36 illustrates the sixteenth mode shape with a natural frequency of 9140.2 Hz. This is the most complex mode displayed, with highly localized flexing around the universal joints and flanges. The shaft experiences substantial torsional-bending coupling behavior at these higher frequencies, which can contribute to wear and potential fatigue if harmonic excitation matches this range. The increased stiffness due to the HS-carbon epoxy coating is evident in the upward shift of these higher-order natural frequencies compared to the plain steel version.

- 3.

Modal analysis coating E-Glass Polyester steel

Figure 37 depicts the first natural mode shape of the two-piece cardan shaft coated with E-Glass Polyester on a steel core. The corresponding natural frequency is approximately 947.36 Hz, making it the lowest fundamental mode. This mode exhibits a global bending deformation with a single curvature across the shaft length, and the most displacement is concentrated toward the mid-span. The relatively low value of this first mode frequency implies that avoiding resonance in this range is important for ensuring smooth operation during low-speed rotational conditions.

Figure 38 presents the sixth natural mode, with a natural frequency of 2581.7 Hz. This higher-order mode reveals a more complex deformation pattern compared to the fundamental mode, with multiple nodal points distributed along the shaft. The flange and universal joints show localized twisting and flexing due to the material coating and its stiffness contribution. This indicates that, at mid-range operational speeds or harmonic excitation, the cardan shaft can exhibit intricate vibrational behavior that needs careful assessment for long-term fatigue resistance.

Figure 39 illustrates the twelfth mode shape, which occurs at a higher natural frequency of 7416.8 Hz. The mode shape is noticeably more intricate, with several sections vibrating out of phase along the length of the shaft. This higher-order mode reveals substantial deformation concentrated around the coupling and flange connections, where geometry and material layering effects become significant. Vibrations at this frequency are typically unlikely during standard service but could be triggered under transient impacts or high-speed rotational fluctuations.

Figure 40 depicts the sixteenth natural mode shape, corresponding to a natural frequency of 8720.7 Hz. This is the most complex deformation pattern among the presented modes. The shaft exhibits torsional and flexural distortions that are highly localized at the flange and joint areas, suggesting that the coating and substrate stiffness play a critical role at these high frequencies. The occurrence of such complex mode shapes at this high frequency is less likely under normal operating conditions but must be considered for dynamic analyses under extreme service or shock loads.

- 4.

Modal analysis Stainless-steel

Figure 41 illustrates the first natural mode shape of the stainless-steel two-piece cardan shaft, corresponding to a fundamental frequency of 923.33 Hz. The mode exhibits a primary bending deformation across the length of the shaft, with the mid-span region experiencing the most pronounced displacement. The fixed support at both ends constrain the motion, resulting in minimal deflection near the flanges. This first mode is the most critical for resonance concerns at low-speed operating conditions and must be carefully considered in the shaft design.

Figure 42 depicts the sixth natural mode shape, with a frequency of 2581.9 Hz. This higher-order mode features multiple nodal points along the shaft, producing a more complex deformation pattern involving bending and twisting effects. The color contours highlight significant stress and displacement variations around the couplings and joints, as the structure responds dynamically to increased frequencies. Vibratory behavior at this level would only manifest under higher-speed operations or transient excitation, making it a potential concern for durability under cyclic loads.

Figure 43 displays the twelfth natural mode, at a frequency of 7306.2 Hz. This mode shape reveals further complexity with multiple inflection points distributed along the shaft length. The deformation is highly localized around the coupling areas and the flanges, suggesting that these regions could be most susceptible to high-cycle fatigue if the shaft is excited near this frequency. The magnitude of displacement is much smaller at this stage due to the stiffness of the stainless-steel material, and resonance under this mode is unlikely under typical operating speeds.

Figure 44 illustrates the sixteenth natural mode, reaching a high frequency of 8510.7 Hz. The deformation pattern is extremely intricate, with several distinct nodes across the shaft assembly and significant localized twisting behavior near the couplings. Vibratory motion at this extreme frequency is highly localized, and such behavior would require significant harmonic excitation to occur in practice. These results indicate that the cardan shaft has a broad range of natural frequencies, ensuring a stiff dynamic response across the operating range.

- 5.

Modal analysis Hardox 400

Figure 45 depicts the first natural mode of the two-piece cardan shaft constructed from Hardox 400 material. The corresponding natural frequency is approximately 1191.1 Hz, making this the fundamental mode. The deformation is predominantly global bending across the shaft's length, with the greatest displacement observed toward the center. The fixed supports at both ends restrict motion, allowing the shaft to flex under dynamic loads. Given the material's strength, this first mode frequency is relatively high compared to other shaft materials, which is advantageous for avoiding resonance at lower operating speeds.

Figure 46 illustrates the sixth natural mode shape at a frequency of 2085.4 Hz. Here, the deformation pattern is more complex, characterized by multiple nodes and a mixture of bending and twisting across the shaft. The coupling and flange areas demonstrate localized stress concentrations and notable flexing. This indicates that at this higher-order mode, dynamic excitation could produce more intricate stress distributions, especially around connections, making it important to ensure these joints can withstand such dynamic effects under prolonged operation.

Figure 47 displays the twelfth natural mode at 3842.9 Hz. In this mode shape, further complexity is introduced, with several points of inflection distributed along the shaft. These inflection points produce localized torsional and bending deformations, especially at the couplings and flanges. The significantly increased frequency implies that this deformation would only occur under very rapid oscillatory excitations and is unlikely to be triggered during typical operating conditions. Nevertheless, recognizing this mode is important for avoiding unforeseen resonances at higher operating speeds or under transient impact loads.

Figure 48 represents the sixteenth natural mode with a frequency of 5314.5 Hz. The mode shape is highly intricate, and displacement patterns show small wavelength distortions across the shaft's length. The most significant dynamic effects at this frequency appear around the flange and joint areas, where multiple inflection points exist. Even though this is a very high-order mode unlikely to be exciting in practice, it provides useful insight into the behavior of the Hardox 400 shaft under extreme dynamic conditions. This highlights the material's rigidity and its capacity to support torsional and flexural vibrations without excessive deflection.

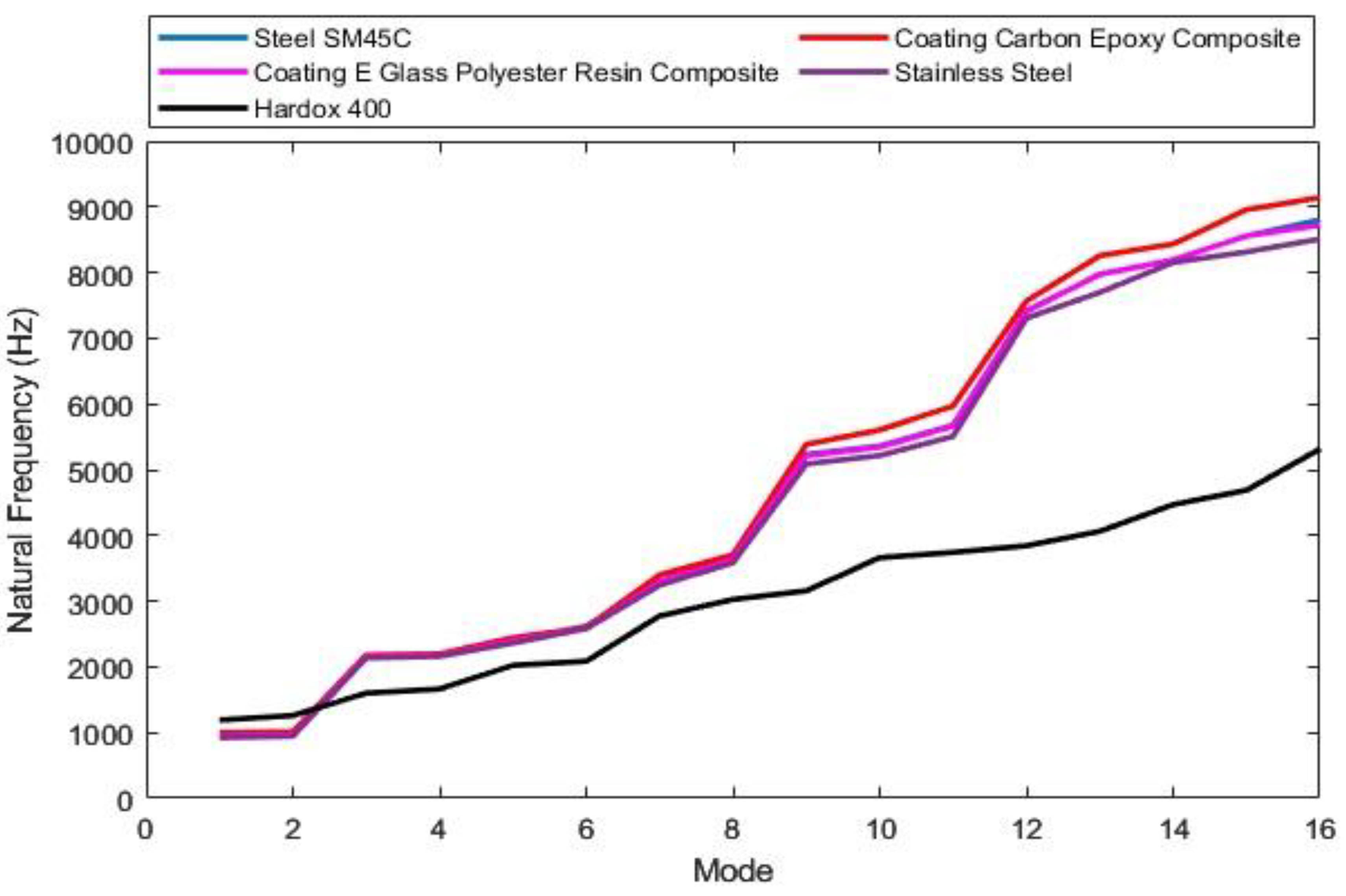

Figure 49 illustrates the natural frequency variation for different materials across the first 16 modes of the cardan shaft. The graph plots the mode number on the x-axis and the corresponding natural frequency (Hz) on the y-axis, allowing a direct comparison between shafts constructed from Steel SM45C, Coating Carbon Epoxy Composite, Coating E-Glass Polyester Resin Composite, Stainless Steel, and Hardox 400.

From the graph, we can observe that for all materials, the natural frequency generally increases as the mode number rises, which is expected because higher-order modes represent more complex shapes and require greater energy to excite [

18,

19].

A clear trend emerges showing that Hardox 400 (black) consistently yields the lowest natural frequencies across all modes. This is due to its comparatively lower stiffness relative to the other materials or possibly its higher density, which increases inertia and reduces the vibratory frequency.

On the other hand, Coating Carbon Epoxy Composite (red) and Stainless Steel (purple) shafts produce the highest natural frequencies throughout the mode range. This indicates that these materials impart greater stiffness to the shaft assembly and improve its dynamic behavior, making them highly resistant to resonance at typical operating speeds [

19].

Steel SM45C (blue) and Coating E-Glass Polyester Resin Composite (pink) follow very similar trends, producing natural frequencies that lie between those of stainless steel and Hardox 400. The proximity of these two curves implies comparable dynamic stiffness and material properties under similar geometrical configurations.

As the mode number increases especially beyond the 10

th mode the gaps between materials widen. This implies that material choice becomes even more significant at higher modes, where variations in stiffness and density greatly influence the shaft’s dynamic characteristics.

Figure 49.

Natural frequency variation for all materials.

Figure 49.

Natural frequency variation for all materials.