1. Introduction

With the acceleration of industrialization, a large number of chromium-containing pollutants enter the soil environment through industrial wastewater discharge, waste residue accumulation and atmospheric deposition. According to the latest assessment report of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the total amount of chromium emitted by industrial activities in the world exceeds 2.6×10

6 tons per year, of which China contributes more than 38% [

1]. At present, there are nearly 26 abandoned chromate manufacturers and more than 40 chromium slag fields in China, where hexavalent chromium Cr(VI) concentrations in soil and groundwater far exceed China environmental standards [

2]. Therefore, studying the migration and transformation mechanism of Cr(VI) in soil and developing efficient remediation technologies are of great significance for pollution risk control and safe reuse of land.

Trivalent chromium (Cr(III)) and Cr(VI) are the most common and relatively stable chromium states in soils [

3], and their effects on human health and the natural environment are different [

4]. Cr(VI) can accumulate in plants and animals, and eventually cause serious damage to human health through the accumulation of the food chain, so Cr(VI) is listed as the first group of human carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) [

5]. Cr(VI) can be accumulated in liver, kidney, heart, blood and endocrine glands by oral administration, skin contact and inhalation. Studies on animals and humans show that Cr(VI) has many negative effects on liver function in vivo and in vitro [

6]. Cr (VI) exposure increases the risk of cancer [

7]. Occupational exposure to Cr(VI) is associated with lung, nasal and sinus cancer in humans, and is suspected to be associated with gastric and laryngeal cancer in humans [

8]. Cr (III) has always been regarded as a pharmacologically active element in contrast to Cr(VI) toxicity, which can improve glucose metabolism [

9], affect lipid metabolism [

10,

11] , etc. However, occupational exposure to Cr(III) has been shown to cause eardrum damage, resulting in decreased hearing levels [

12]. Cr(III) is usually present in soil as a low solubility chromium hydroxide (Cr(OH)

3) precipitate with a low migration rate [

13]. Compared with Cr(III), Cr(VI) is highly soluble and mobile in a wide pH range. The main forms of Cr(VI) are dichromate (Cr

2O

72-) and chromate (CrO

42-) [

14],Rainwater, irrigation or wastewater discharge may cause Cr(VI) leachate to be continuously released into the underground environment, posing a great threat to the groundwater environment [

2]。

In the soil environment, the form of chromium is not fixed. Soil is a complex heterogeneous medium. At present, studies on the valence state changes of Cr(VI) mainly focus on factors such as soil composition, pH value and organic matter content [

15] [

16]。For example, Cr(III) may be oxidized to Cr(VI) under oxidizing and alkaline conditions, while Cr(VI) is easily reduced to Cr(III) under reducing conditions [

17]. Reducing agents (such as humic acid) can reduce Cr(VI) to less toxic Cr(III) [

18]. At the same time, soil is a complex system, in which there are complex physical, chemical and biological interactions between various elements (such as iron, manganese, aluminum, silicon, etc.) and chromium [

19], These interactions not only affect the transformation of chromium forms, but also determine the distribution characteristics of chromium and other elements in the soil microstructure. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of the distribution of Cr(VI) and Cr(III) species in soil particle microstructure is essential for understanding the environmental behavior of chromium. Moreover, it is difficult to reveal the distribution of chromium in soil and its interaction with multiple elements on a micro scale. In recent years, with the development of microanalysis techniques (such as SEM-EDS [

20,

21], synchrotron radiation [

22] , etc.), it is possible to study the distribution and morphology of elements in soil on a microscopic scale, but these techniques are often costly and require strict conditions for sample preparation and analysis. At the same time, most of the existing research is based on artificial homogeneous soil [

18], but the actual Cr slag field soil has significant heterogeneity, in which Cr(VI) mostly exists in aging form, and forms complex combination with iron and manganese oxides, clay minerals or organic matter [

23]. This difference between laboratory simulation and actual pollution scenario makes it difficult for simulation system to accurately reflect the occurrence state of Cr(VI) in real soil environment.

At present, many researches on Cr(VI) contaminated soil mainly focus on the total amount and different forms of Cr in soil and the extractable forms of chromium by chemical extraction method [

24]. At present, although there has been some progress in the study of Cr(VI) in the soil of chromium slag field, there is still a lack of systematic analysis of the influence of multiple factors. Especially, it is difficult to reveal the interaction mechanism between Cr and other elements on the micro- macroscopic scale. Based on this, this study takes the soil from actual chromium slag sites as the core research object, adopts a multi-dimensional research strategy combining macro and micro perspectives, and deeply explores the valence state change rules of Cr(VI) in real pollution environments. At the macro level, the influence of pH value, organic type (such as humic acid, fulvic acid) and reducing agent addition on Cr(VI) valence transformation was analyzed. At the micro level, the spatial distribution characteristics of Cr, Fe, Mn, Al and other related elements in soil microstructure were captured by μ-XRF micro-area analysis technology, and the correlation between elements was revealed. Which provides theoretical support for the remediation of chromium-contaminated soils.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. The Pollution Status of Chromium (VI) in the Chromium Slag Site in North China

Cr(VI) contaminated soil came from a chromium slag site in North China, known for its alkaline soil with a pH range of 8.16-9.37. This alkalinity was attributed to the production process of chromate, which includes oxidation roasting and alkaline leaching [

25]. The content of soil organic matter in chromium slag field was low, only 3.2%, which may be caused by heavy metals such as chromium inhibiting the growth and activities of soil microorganisms, preventing the decomposition, transformation and accumulation of organic matter, and the alkaline environment of chromium slag changing soil pH was not conducive to the accumulation of organic matter. In the chromium slag site, three soil samples numbered BC-36-3, BC-36-4, and BC-35 were determined 11 times repeatedly. The total chromium contents were 16484, 15326, and 15796 mg/kg, respectively, while the average Cr(VI) contents were 2124, 1926, and 3509 mg/kg in sequence. Cr(VI) accounted for 13%-22% of the total chromium content. The content of Cr(VI) was 20-40 times the screening value of 78 mg/kg for the second type of land used in China's Standard for Soil Pollution Risk Control of Soil Environmental Quality Construction Land (GB 36600-2018), indicating that there is serious Cr(VI) pollution in the investigated soil. Cr(VI) leakage from Cr(VI) contaminated soils usually originates from aqueous CrO

42-solutions, such as leachate from chromium residue piles due to rainfall. Therefore, Cr (VI) initially enters the soil as water-soluble CrO

42-, which undergoes complex adsorption and precipitation reactions with soil minerals [

26].

2.2. Influence of PH on Cr(VI)

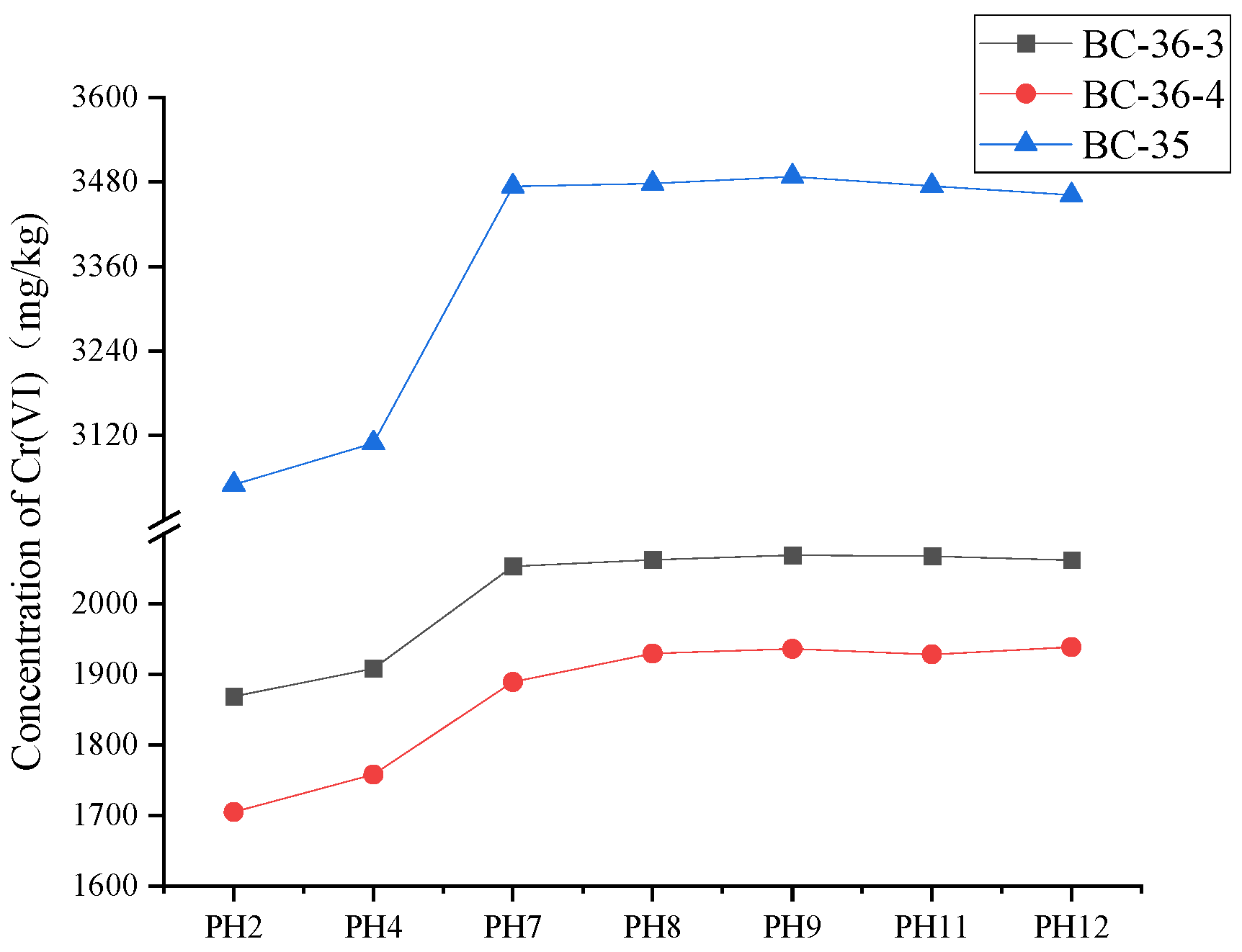

The relationship between Cr(VI) content and pH value in three kinds of soil is shown in

Figure 1. Soil pH value is an important parameter to determine Cr(VI) type and its redox ability. Under the action of pH, Cr(VI) content in three kinds of soil changed in the same way: with the decreased of pH value, Cr(VI) content in soil decreased. It was shown that acidic conditions were more conducive to Cr(VI) reduction. The change of Cr(VI) content in soil affected by pH is due to the existence of different forms of Cr(VI) at different pH conditions. When pH is in the range of 0 - 6, HCrO

4− and Cr

2O

72− dominate, CrO

42− appears at about pH 4.5, reaches a maximum at pH≥8, and maintains this state at higher pH values [

17]. Cr(VI) is a strong oxidant with a very high standard redox potential (E

0(Cr(VI)/Cr(III))=1.35V) in acidic environments [

27]. pH increases stability, especially near neutral and alkaline pH values, where the standard redox potential is -0.12V [

28]。The electrode potential of Cr(VI) reduced to Cr(III) under acidic condition is higher than that under alkaline condition. Consequently, significant disparities in Cr(VI) content was observed at pH<7, whereas such differences diminish at pH>7.

When the soil pH value was 2, the concentration of hexavalent chromium in BC-36-3, BC-36-4 and BC-35 soil samples was decreased by 9.42%, 11.42% and 12.22%, respectively, compared with the mean value of pH value 7, 8, 9, 11 and 12. When the soil pH value is adjusted to 4, the concentration of hexavalent chromium in each soil sample is also reduced to different degrees compared with the mean value of pH value 6, 8, 9, 11, 12. The concentration of hexavalent chromium in BC-36-3, BC-36-4 and BC-35 soil samples decreased by 7.50%, 8.67% and 10.52%, respectively, compared with the mean values at pH 7, 8, 9, 11 and 12.

2.3. Influence of Organic Matter on Cr(VI)

2.3.1. Influence of Fulvic Acid on Cr(VI)

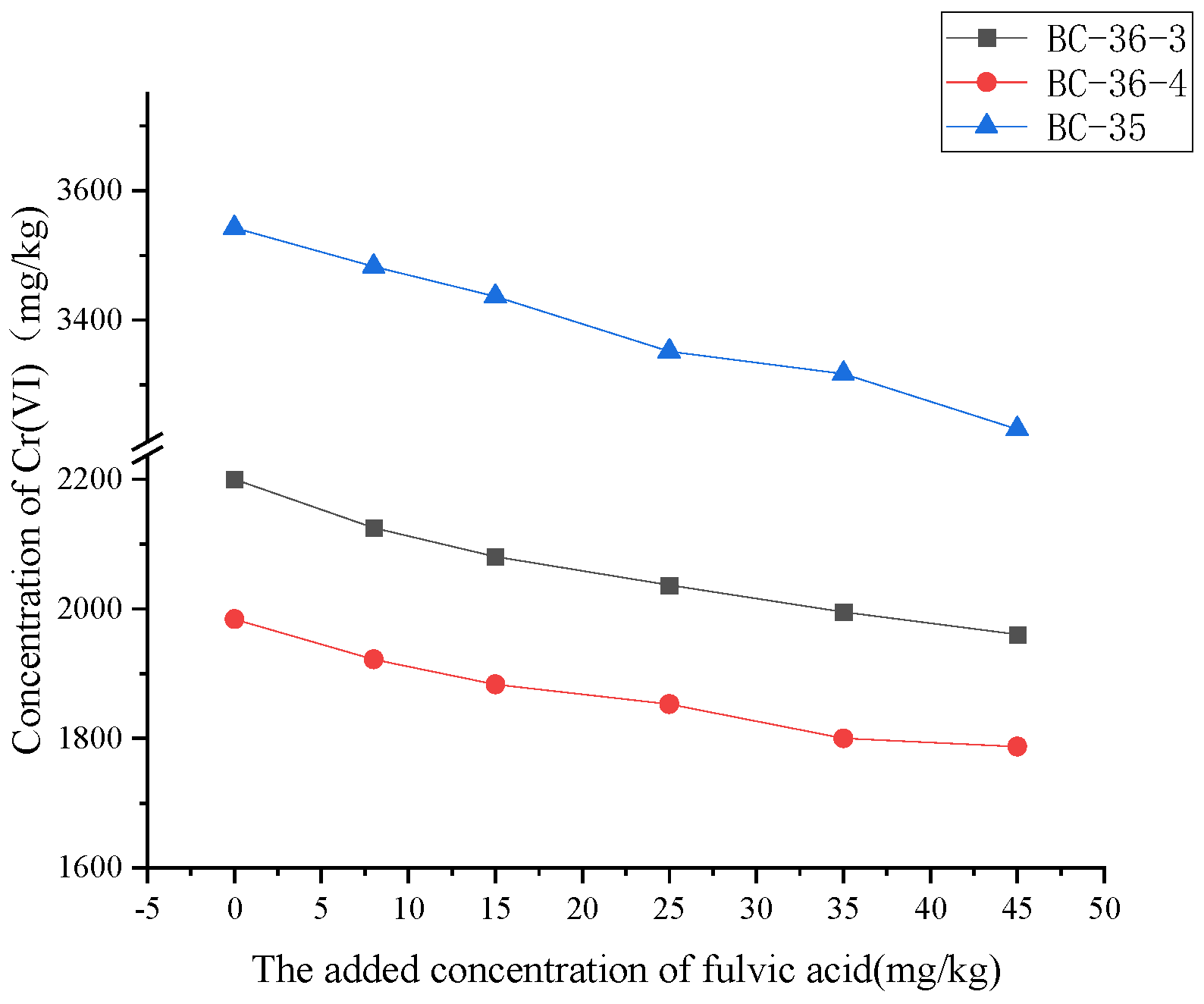

The changed of Cr(VI) content after adjusting the fulvic acid addition in the contaminated soil are shown in

Figure 2. Cr(VI) content in contaminated soil gradually decreased with the increase of fulvic acid content, indicating that fulvic acid had significant reduction effect on Cr(VI) in soil. When fulvic acid was added at 45mg/kg, the hexavalent chromium content in BC-36-3, BC-36-4 and BC-35 decreased by 10.89%, 9.90% and 8.77% respectively compared with that without fulvic acid, because fulvic acid contained a large number of active functional groups such as phenolic hydroxyl and carboxyl, which had certain reductivity. In the soil environment, fulvic acid can reduce Cr(VI), which is more toxic and mobile, to Cr(III), which is relatively low toxicity and weak mobility. In addition, when fulvic acid is added to the soil, the concentration of H

+ in the soil will increase significantly. The increase of H

+ concentration directly leads to the decrease of soil pH value, and the enhancement of acidic environment provides favorable conditions for the transformation of Cr(VI) to Cr(III). Under this environment, Cr(VI) is more likely to undergo reduction reaction, thus transforming into Cr(III), and finally leading to the decrease of Cr(VI) content in soil.

2.3.2. Influence of Citric acid on Cr(VI)

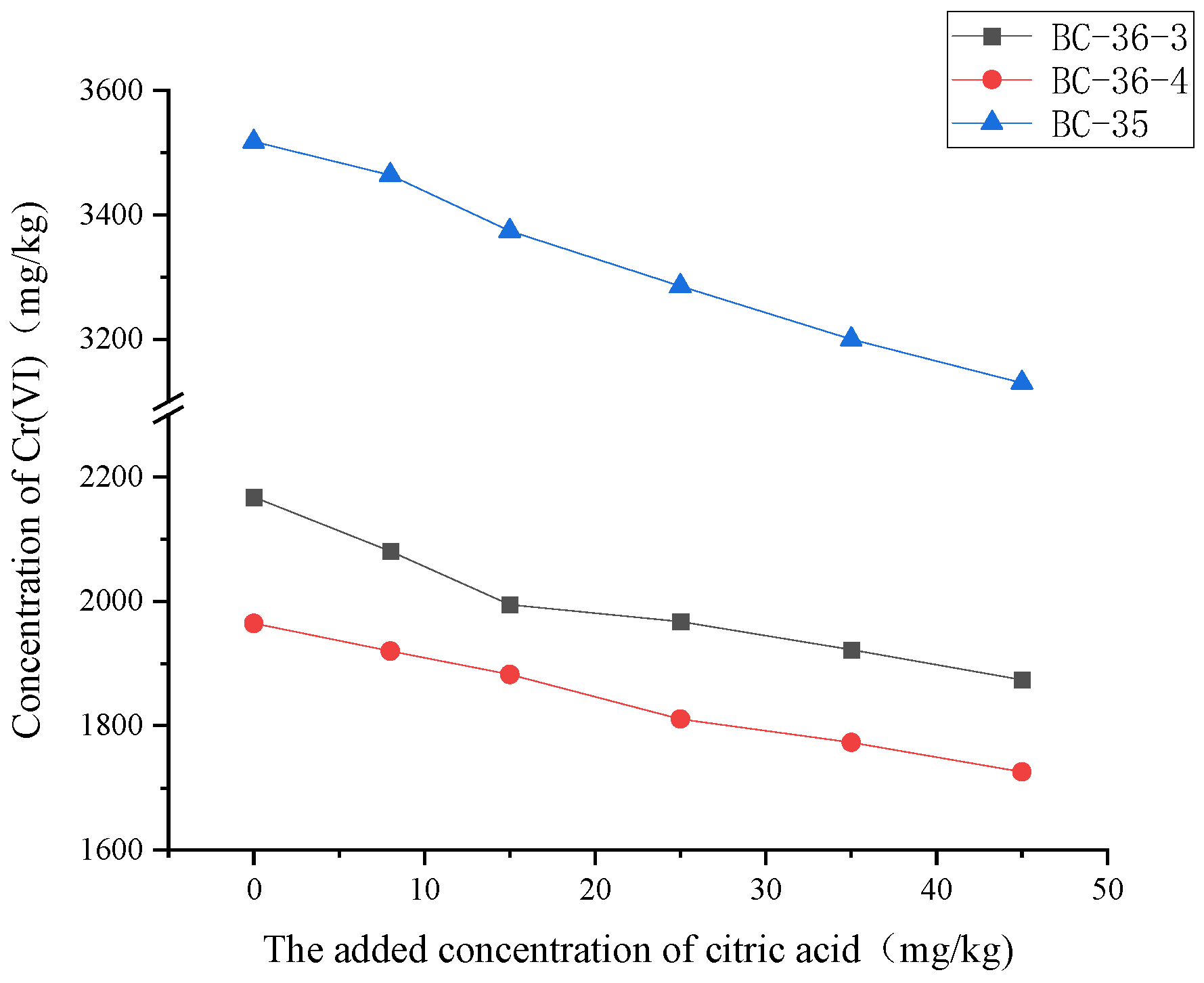

The changes of Cr(VI) content after adjusting the amount of citric acid added in chromium contaminated soil are shown in

Figure 3。Cr(VI) content in contaminated soil gradually decreased with the increase of citric acid content, indicating that citric acid had obvious reduction effect on Cr(VI) in soil. The reason for the change of Cr(VI) content is that citric acid on the one hand chelates with soluble Cr(VI), and on the other hand, the existence of small molecular organic acids improves the activation of iron and manganese oxides and enhances their ability to bind Cr. The higher the citric acid concentration, the lower the Cr(VI) concentration, because the lower the pH value, the more conducive to Cr(VI) reduction [

29]. When citric acid was added at 45mg/kg, hexavalent chromium content in BC-36-3, BC-36-4 and BC-35 decreased by 13.56%, 12.16% and 10.45%, respectively, compared with that without citric acid. The linear regression equation slope of citric acid was generally larger than fulvic acid, which may mean that citric acid had a more significant effect on Cr(VI) concentration reduction at the same addition amount, and the ability of citric acid to reduce Cr(VI) is slightly stronger than fulvic acid, which is related to its simplicity of structure. Once Cr(VI) is reduced to Cr(III), it reacts with the carboxyl group (-COOH) in citric acid to form a stable complex. The formation of this complex improves the stability of chromium in soil and effectively inhibits the re-release of Cr(VI) [

30], thus reducing the bioavailability and toxicity of chromium.

2.4. Influence of FeSO4 on Cr(VI)

Fe(II) reduction of Cr(VI) mainly occurs in anaerobic environments. In the presence of O

2, Fe(III) is the main species (Fe(II) can be rapidly oxidized to form Fe(III)), while Fe(III) cannot reduce Cr(VI), so the sample was sealed and stored after adjusting the amount of FeSO

4 added in contaminated soil, as shown in

Figure 4. With the increase of FeSO

4 content, the content of Cr(VI) in polluted soil gradually decreases, indicating that FeSO

4 had a significant reduction effect on Cr(VI) in soil. Iron plays an important role by electron giving (i.e. in the oxidation of Fe

2+ to Fe

3+) and adsorption as precipitation/adsorption, and the standard electrode potential (E

0 (Fe

3+/Fe

2+)) is relatively low at 0.77 [

28]. In addition to the direct reduction of Cr(VI), Fe

2+ can also be used as an electron transport medium to accelerate the reduction reaction between Fe

0 and Cr(VI) [

31]. The ability of FeSO

4 to reduce Cr(VI) is stronger than fulvic acid and citric acid. At the same time, it is reported that the reduction of Cr(VI) by Fe(II) is a relatively fast process (tens of seconds to several hours), which is faster than the reduction of organic matter [

28].

It can be seen from

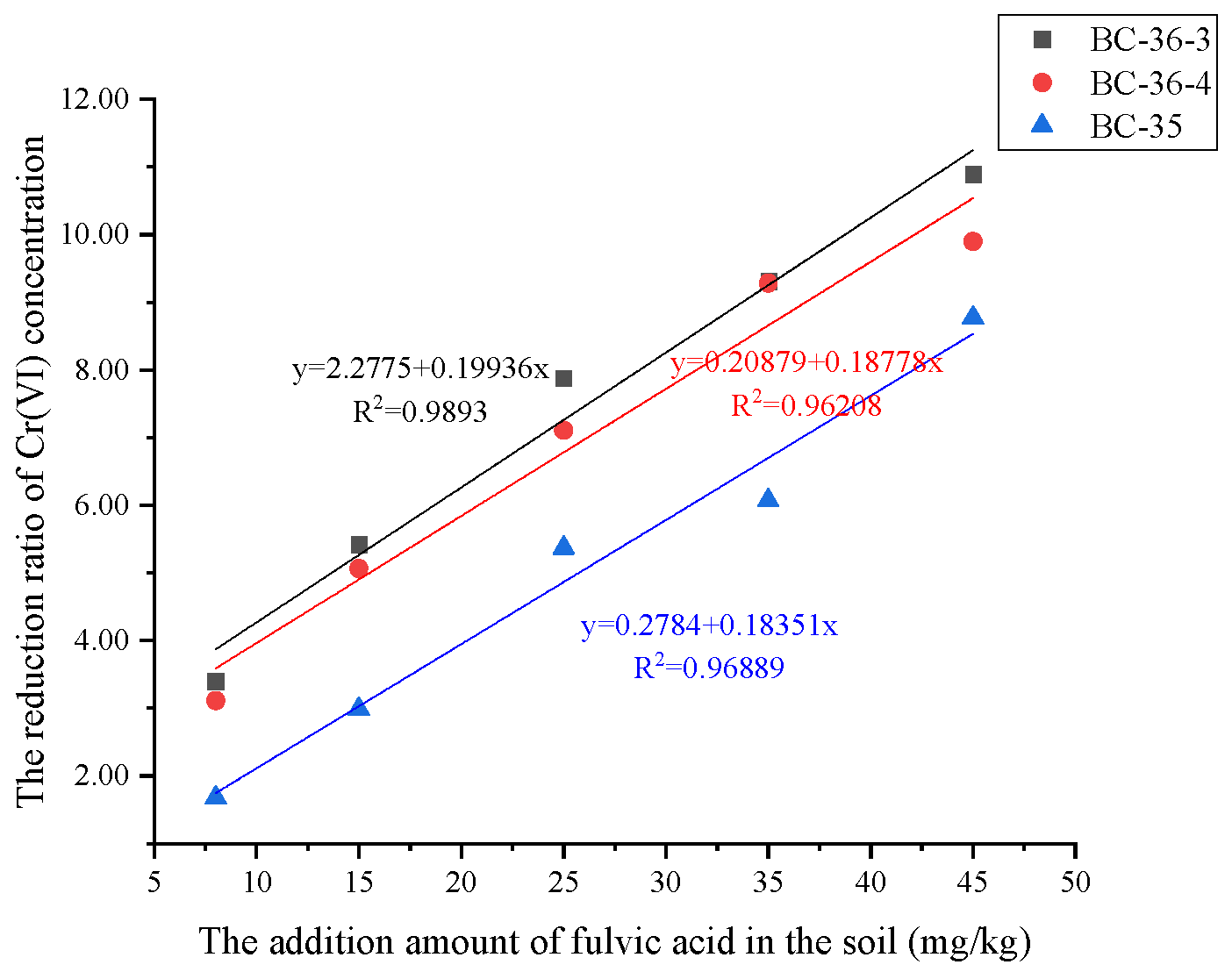

Figure 5 that with the increase in the addition of fulvic acid, citric acid and FeSO

4, the hexavalent chromium reduction ratio of the three soils all showed an upward trend, but the increase ranges were different. Among them, the addition of FeSO

4 improved the reduction ratio of hexavalent chromium most significantly. Its fitted straight line slope was much higher than that of fulvic acid and citric acid. This indicates that FeSO

4 had a strong reducing capacity for hexavalent chromium in chromium residue site soil, probably due to the efficient reduction of hexavalent chromium to trivalent chromium by the ferrous ions in FeSO

4. Citric acid had the second reduction effect, and the reduction ratio of hexavalent chromium in different soils was also obviously increased, which indicated that citric acid could promote the reduction of hexavalent chromium to a certain extent, which might be related to its acidity and complexation, which was helpful to change the soil environment and the existing form of hexavalent chromium, thus improving the reduction efficiency. Fulvic acid has a weak reduction effect, but it can still increase the reduction ratio of hexavalent chromium with the increase of additive amount. Fulvic acid may interact with hexavalent chromium through its functional groups, but its mechanism and effect are not as obvious as FeSO

4 and citric acid.

In addition, the response trends of soils with different initial hexavalent chromium concentrations to the three additives were similar, but the specific reduction effects were different. BC-35 soil with the highest initial concentration has a relatively low reduction ratio at the same addition amount, which may be that high concentrations of Cr(VI) may occupy the active site of the reductant, resulting in saturation of the reductant and inability to further reduce more Cr(VI), or high concentrations of Cr(VI) may form more stable complexes or precipitates, thus reducing the reduction efficiency. BC-36-3 with intermediate initial Cr concentration showed the best reduction effect, mainly because the reductant could react effectively with Cr(VI) in this concentration range to achieve the best reduction effect.

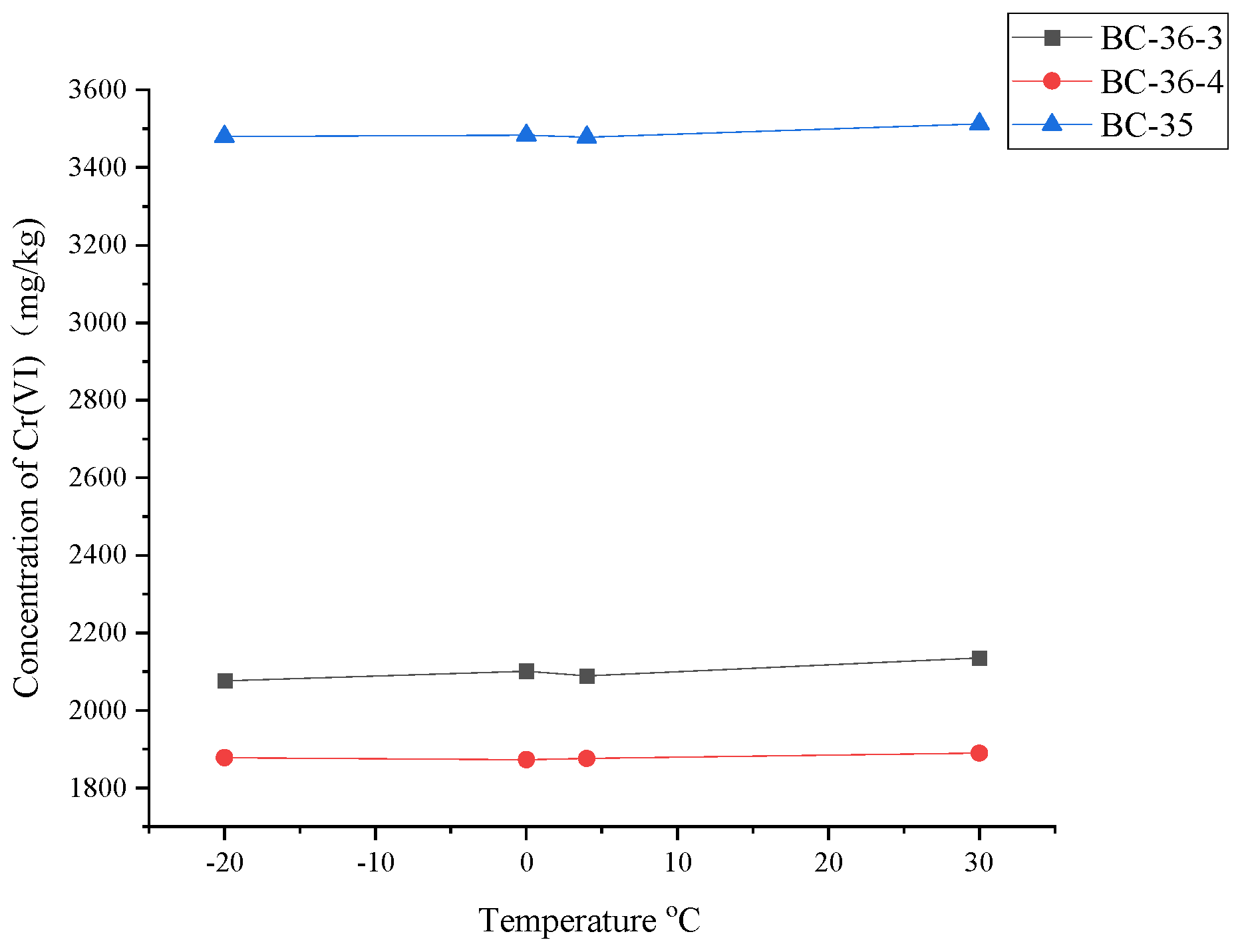

2.5. Influence of Temperature on Cr(VI)

Cr(VI) content changed after adjusting the contaminated soil temperature are shown in

Figure 6. Cr (VI) content in contaminated soil was basically unchanged with the change of temperature. The relative standard deviations (RSD) of Cr(VI) content measured in BC-36-4, BC-36-3, and BC-35 at -20 °C, 0 °C, 4 °C, and 30 °C were 0.43%, 1.20%, and 1.21%, respectively, which indicated that temperature had little effect on Cr(VI) transformation in soil within the temperature range of-20℃-30℃. However, microorganisms play an important role in Cr(VI) bioreduction. However, although experimental data showed that temperature had no significant effect on Cr(VI) content, microorganisms still play a crucial role in Cr(VI) bioreduction. Changed in temperature can significantly affect microbial growth and metabolic activities, thus indirectly affecting Cr(VI) reduction efficiency. The temperature is higher than 45℃, the microorganism will be inhibited. When the temperature is between 0 ℃ and 35℃, the metabolic rate of microorganism will accelerate with the increase of temperature, which can accelerate the decomposition of organic residues and promote the reduction reaction of Cr(VI). In addition, temperature not only affects the activity of microorganism, but also affects its adsorption characteristics in soil. For example, many parameters in Langmuir equation describing adsorption isotherm are closely related to temperature. Saturated adsorption capacity

qm and Langmuir equilibrium constant

K may change with temperature [

32]. However, no effect of temperature on Cr(VI) content was found in this study, probably because the experiment lasted only 45 days, which may not be enough to observe the long-term effect of temperature on Cr(VI) content in soil. Some microorganism-mediated Cr(VI) reduction processes may take longer to appear. Therefore, the effect of temperature change on Cr(VI) content may not be obvious in the short term. Alternatively, the nature and concentration of organic compounds in the soil that have the potential to chelate or reduce Cr(VI) may not be sufficient to trigger significant Cr(VI) reduction.

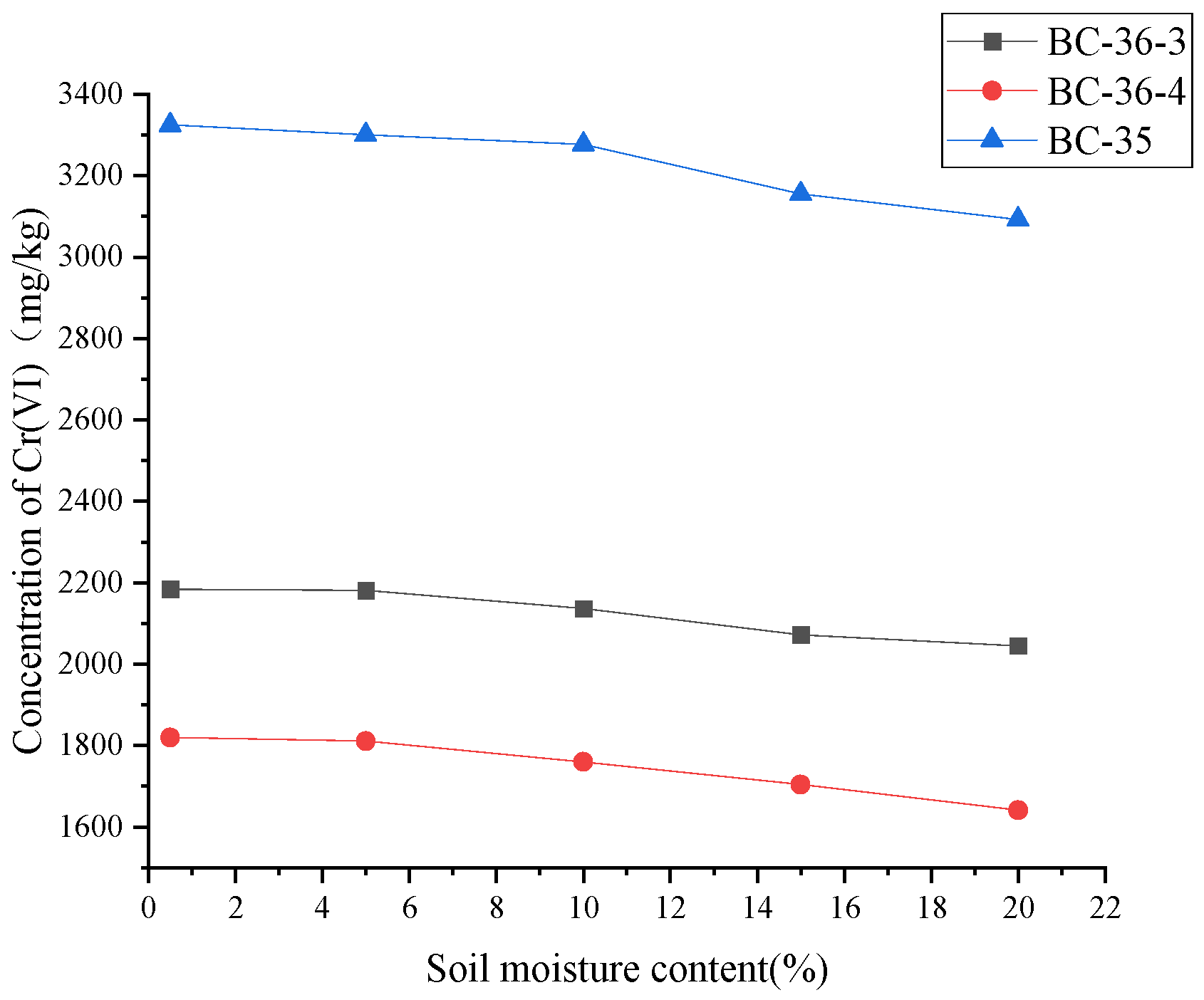

2.6. Influence of Soil Moisture on Cr(VI)

Soil moisture is an important physical property of soil, In this study, soil samples were heated in a drying oven at a low temperature (35℃) until completely dry, and then a certain amount of ultra-pure water was added to each soil sample to obtain soil samples with different moisture content. The distribution of Cr(III) and Cr(VI) species in soil depends on many factors, and soil moisture is critical for Cr(VI) reduction in addition to soil properties [

33]. Cr(VI) content changes after adjusting the contaminated soil temperature as shown in

Figure 7. Cr(VI) content in contaminated soil gradually decreased with the increase of soil moisture, indicating that soil moisture affected Cr(VI) content in soil. This may be because higher soil moisture may provide a more favorable medium environment for hexavalent chromium reduction reaction. For example, moisture can promote the dissolution and diffusion of reducing agents, making them more easily contact and react with hexavalent chromium, thus increasing the reduction ratio. And when air-dried soil is moistened with water and extracted in alkaline solution, iron-containing minerals are dissolved, Fe(III) can be first reduced to Fe(II) by humus substances, and then oxidized by Cr(VI) in redox cycle. Guidotti et al. [

34] reported the ability of Fe(II) to reduce Cr(VI) in solutions with pH values ranging from 2 to 10 and the correlation between Cr(VI) reduction and the presence of iron in soil extracts. In addition, with the increase of soil moisture, the metabolic activity of microorganisms will gradually recover. Microbes play a key role in the biological reduction of Cr(VI), and they can reduce Cr(VI) to Cr(III) through metabolic activities. Studies have shown that the microbial activity under humid conditions is enhanced [

35], which helps accelerate the reduction of Cr(VI).

Compared with organic matter (fulvic acid, citric acid) and FeSO4, moisture had a weaker effect on hexavalent chromium in soil, which may be because soil moisture does not directly react with hexavalent chromium or provide effective electron donors to promote hexavalent chromium reduction as fulvic acid and FeSO4 do.Although increased moisture may be beneficial to the growth and metabolism of soil microorganisms to a certain extent, and some microorganisms have the ability to reduce hexavalent chromium, this effect is relatively slow and limited, and is limited by other factors in the soil (such as microbial species and nutrients).

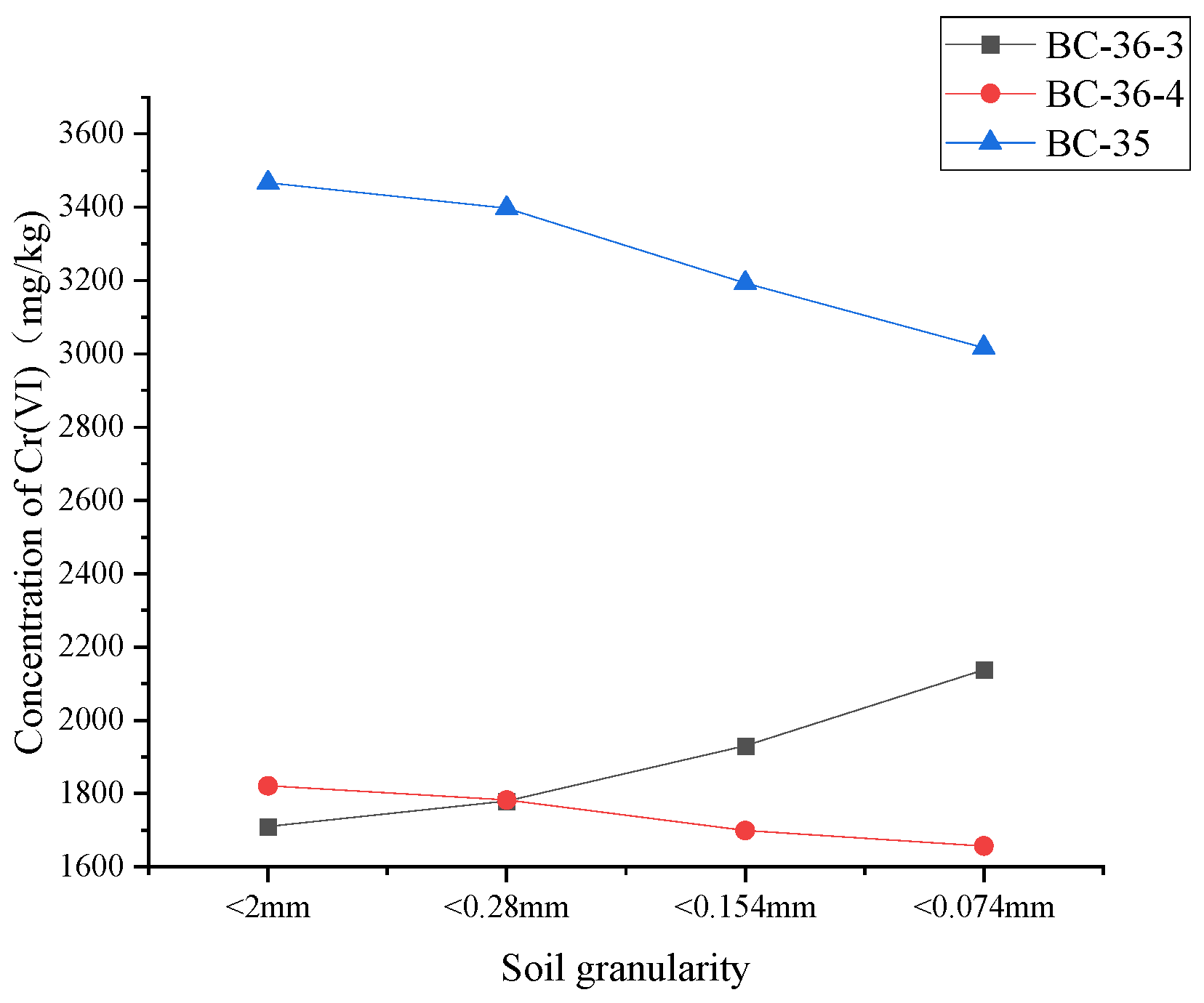

2.7. Influence of Soil Mechanical Composition on Cr(VI)

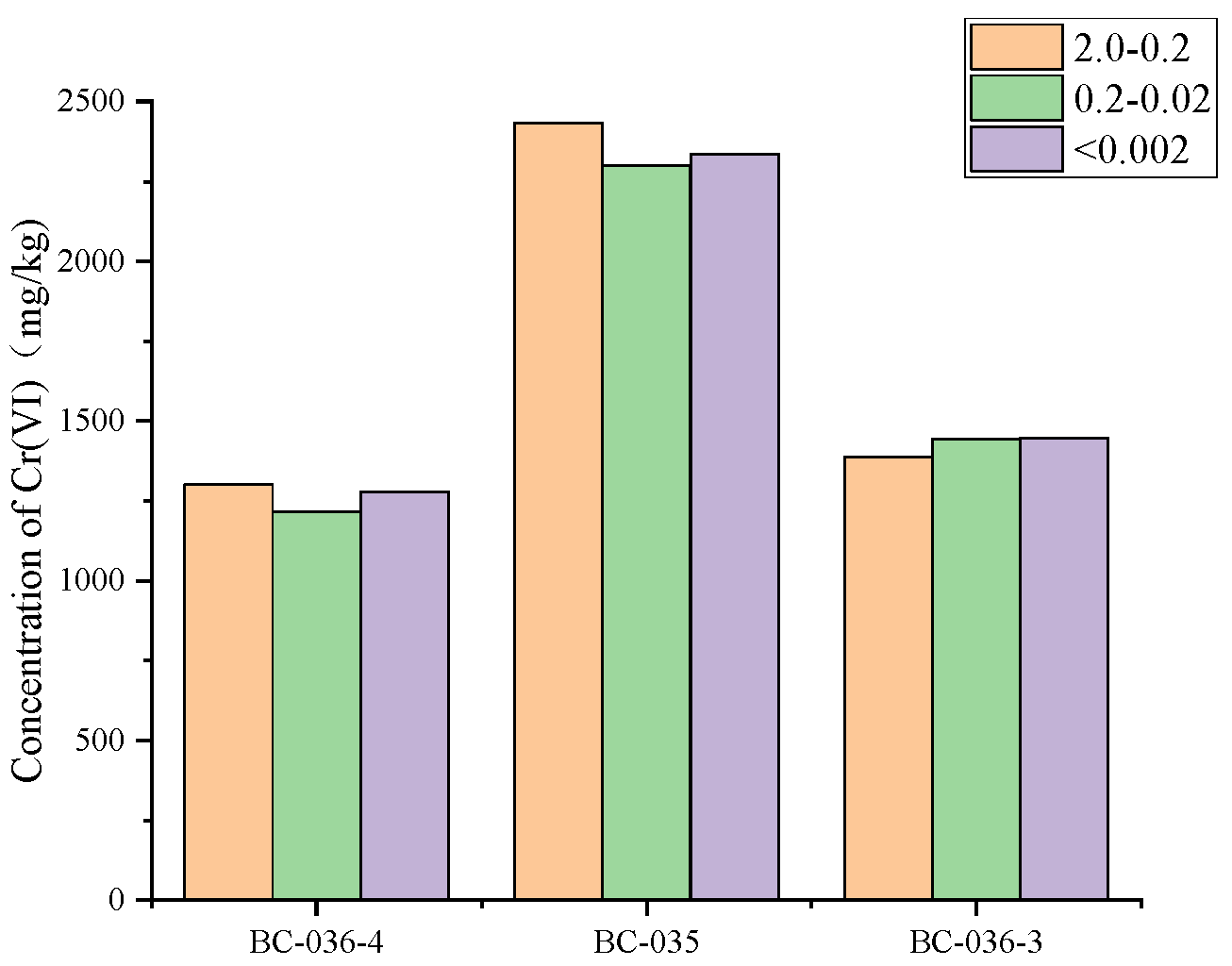

The soil samples were roughly ground and passed through the standard soil sieve of 10 mesh, 60 mesh, 100 mesh and 200 mesh respectively. The soil samples of different particle sizes were collected and divided into soil sample bottles to determine the Cr(VI) content of different mesh soil. As shown in

Figure 8, with the change of soil particle size, the content of Cr (VI) in the three soil samples showed different changing trends. When the particle size of BC-35 sample was less than 2mm, the Cr(VI) content was the highest at 3466mg/kg. As the particle size gradually decreased to less than 0.074 mm, the Cr(VI) content showed a downward trend and finally dropped to about 3016mg/kg. BC-36-4, similar to BC-36-3, showed a trend of Cr (VI) content decreasing gradually with the decrease of soil particle size. BC-36-3, contrary to BC-35 and BC-36-4, had the lowest Cr(VI) content of 1710mg/kg when soil particle size was less than 2 mm. Cr(VI) content increased gradually with the decrease of soil particle size, and reached about 2137mg/kg when the particle size was less than 0.074 mm. This indicated that Cr(VI) content in BC-36-3 sample was relatively high in smaller particle size soil particles, and Cr(VI) content increased with the decrease of particle size.

Generally, the adsorption capacity of Cr(VI) in large grain sand is limited due to its relatively small specific surface area. Therefore, Cr is considered to be difficult to be retained in coarse sand layer through adsorption [

25]. Zhang et al. [

36] also found that the smaller the soil particles, the larger the specific surface area, the stronger the adsorption capacity for Cr(VI), and the higher the Cr(VI) content. However, this study showed that the content of Cr(VI) in coarse sandy soil of BC-36-4 and BC-35 is significantly higher than that in fine grained soil, and it is speculated that the differences in mineral composition between coarse sand particles and fine particles lead to different fixation and reduction effects on Cr(VI).

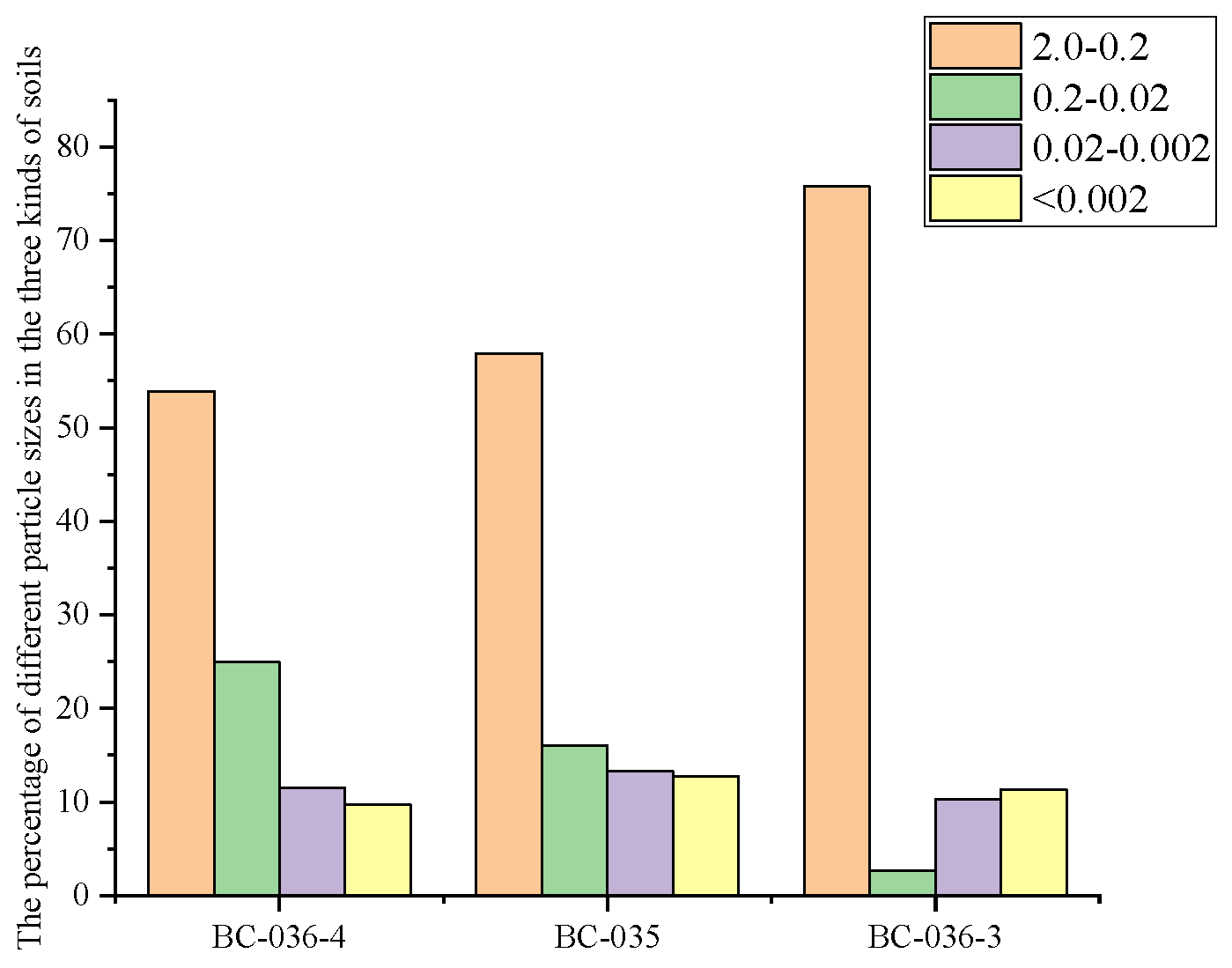

The mechanical composition of the three soils was determined and the grain size distribution of the soils was drawn into

Figure 9. It can be seen from the Figure that the three soils are typical sandy loam, and the mass fraction of soil particles larger than 0.20 mm is 53-76%. The particle size distribution of the three soils was dominated by large particles (2.0-0.2 mm), but the proportion of large particles in BC-036-3 soil was significantly higher than that in BC-036-4 and BC-035 soil. However, the proportion of medium particles (0.2-0.02 mm) in BC-036-3 soil was significantly lower than that in the other two soils. The proportion of very fine particles (< 0.002mm) in the three soils was low and the difference was not significant. The mechanical composition of BC-36-4 and BC-35 were similar, with fine sand (0.2-0.02mm), silt (0.02-0.002mm), and clay (< 0.002mm) showed a decreasing trend, while BC-36-3 was the opposite.

Subsequently, the content of Cr(VI) in the separated soils with different particle sizes was measured, and the corresponding

Figure 10 was drawn. It should be noted that since the silt grade (0.02- 0.002 mm) is calculated when the mechanical composition is determined by wet method, Therefore,

Figure 10 does not include the content of Cr(VI) in silt grade soil. The coarse sand of BC-36-4 and BC-35 samples can be seen in the figure Hexavalent chromium concentration in (2-0.2mm) is higher than fine sand (0.2-0.02mm) and clay fraction Hexavalent chromium concentration in (<0.002mm), combined with

Figure 10 coarse sand (2-0.2mm) is the largest proportion, so the soil with particle size range of 2.0-0.2mm is the main storage range of Cr(VI) in soil, and contributes the most to the total Cr(VI) in soil. BC-36-3 showed the opposite result, Cr(VI) concentration in coarse sand was the lowest, Cr(VI) content in soil was about 1388mg/kg, but this interval accounted for more than 75%. Although Cr(VI) content was not particularly high, it was still the main source of Cr(VI) in this soil because of the large particle proportion. Through the analysis of Cr(VI) distribution and concentration results in different particle size soils, the following phenomena can be well explained: in BC-36-4 and BC-35 soils, Cr(VI) content in soil presents a gradual decrease trend with the gradual decrease of soil particle size, while for BC-36-3 soil, the situation is opposite, with the continuous reduction of soil particle size, the content of Cr (VI) in soil showed a gradual increase. Meanwhile, X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) analysis showed that the iron content of coarse particles in BC-35 and BC-36-4 was 7.45% and 9.32%, respectively, which was significantly higher than that of fine particles (6.41% and 8.73%, respectively). The significant difference of iron content between coarse and fine particles is likely to be one of the key factors for the relatively high Cr content in coarse sand particles. Related studies have pointed out [

37] that iron-containing minerals such as magnetite can inhibit the reduction reaction of Cr (VI), and then affect the content distribution of Cr (VI) in soil.

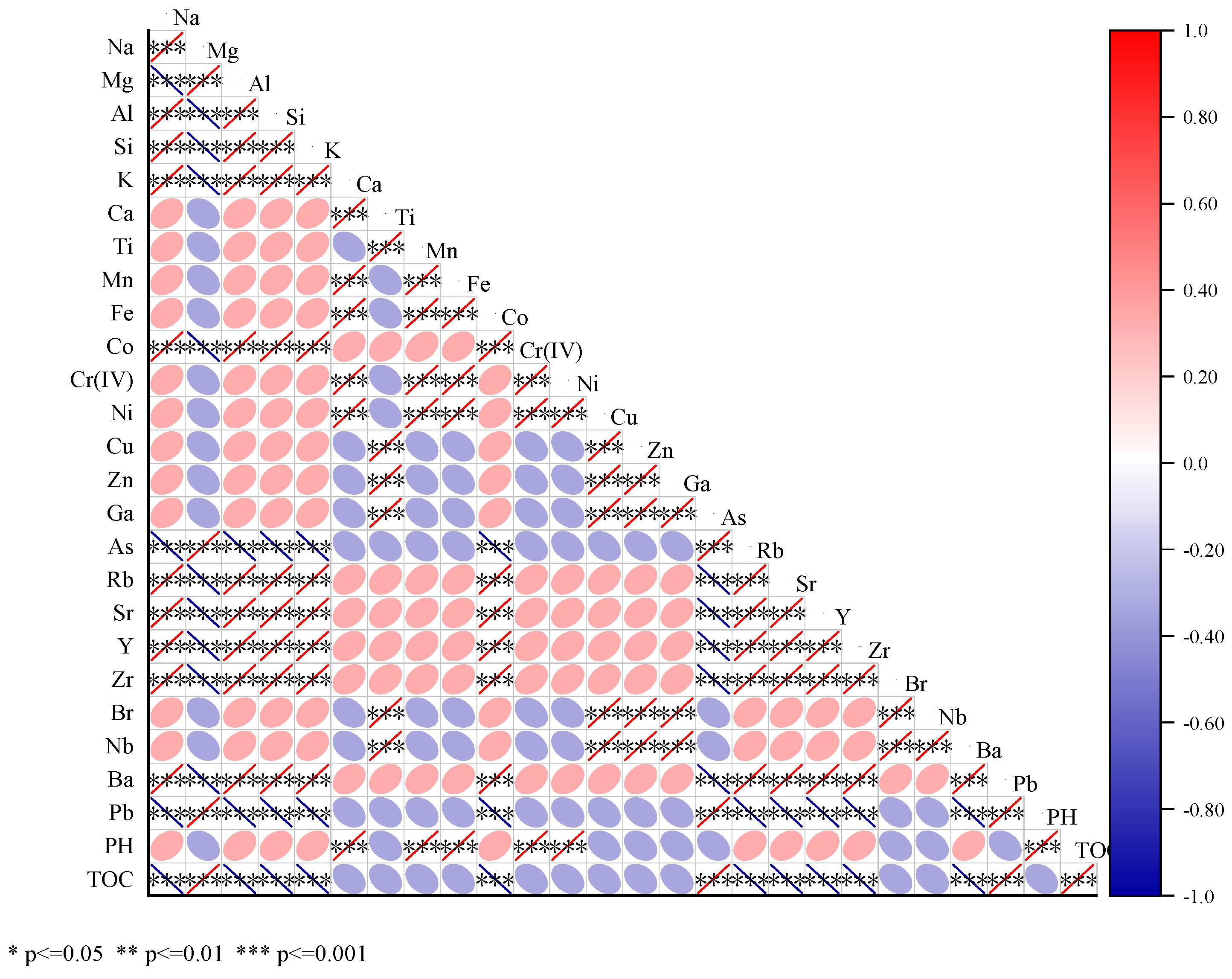

2.8. Correlation Between Chromium and Other Elements

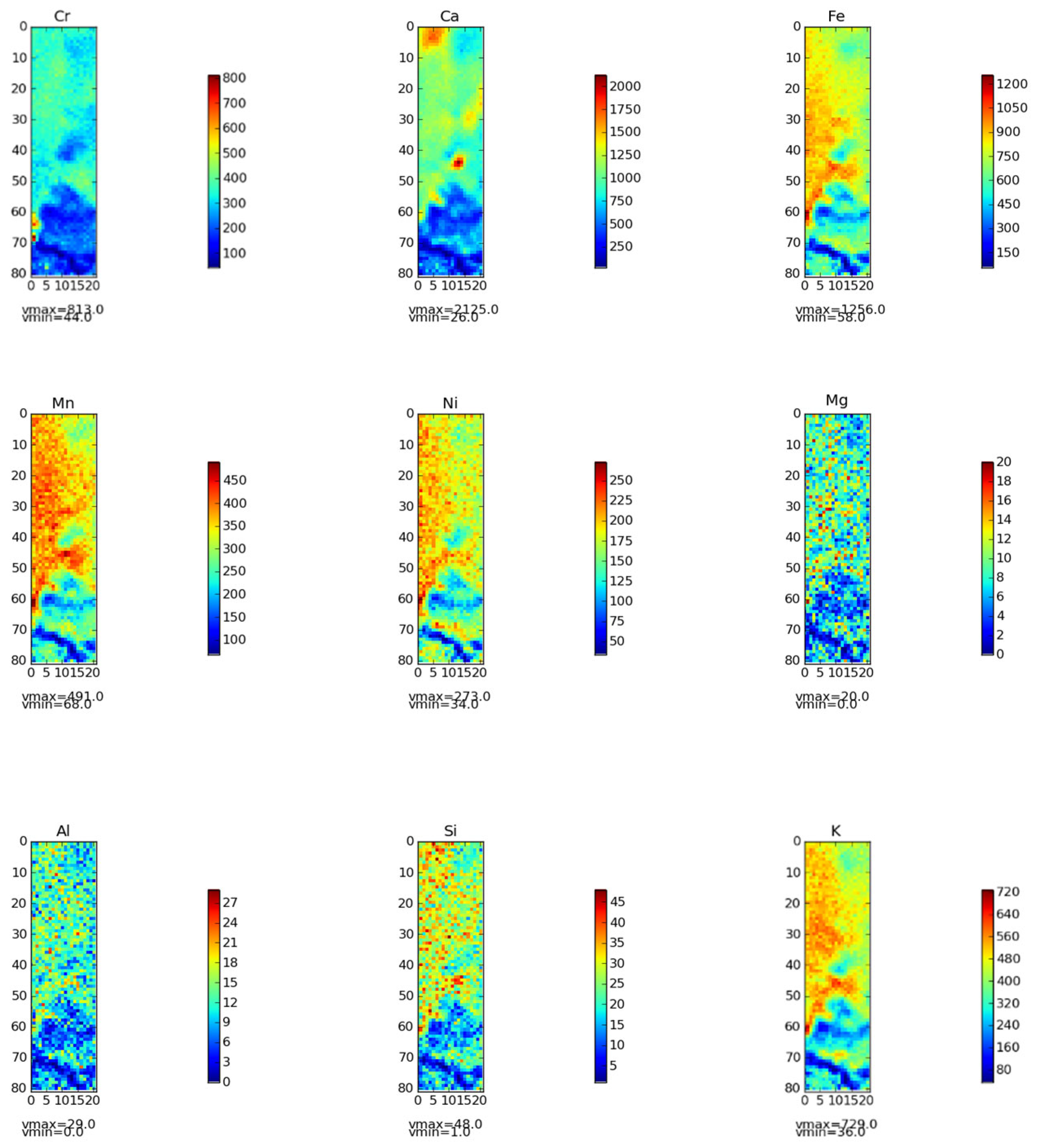

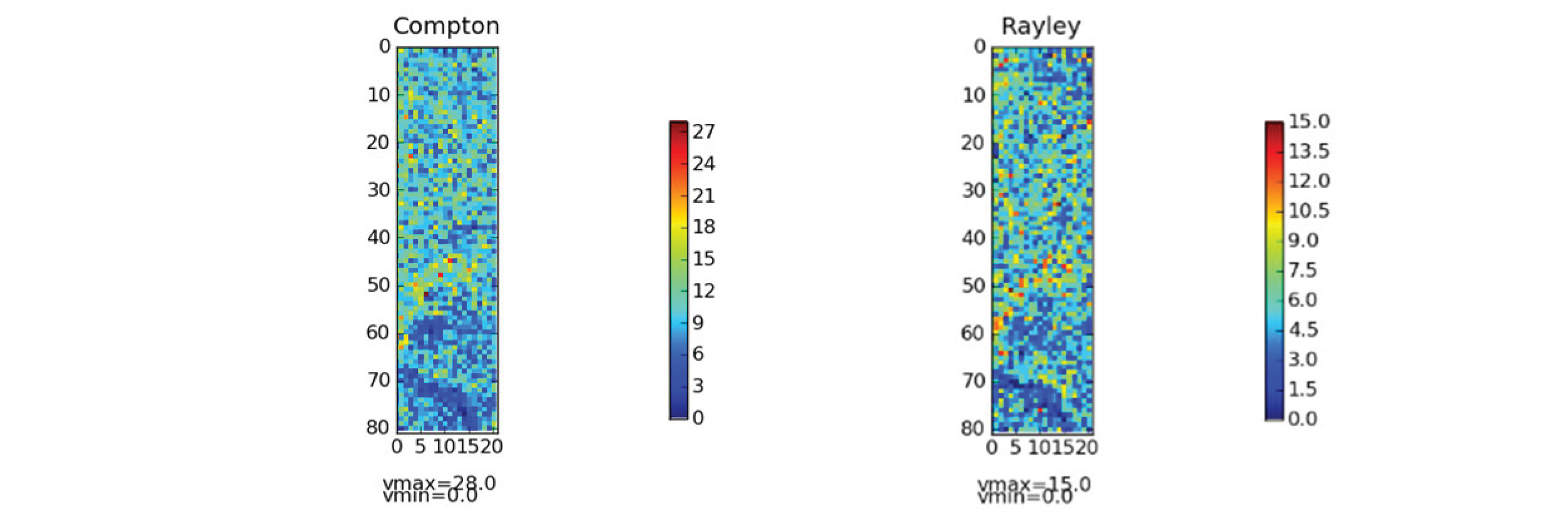

As shown in

Figure 11, a correlation analysis was conducted between the content of hexavalent chromium in the soil and the contents of other elements in the soil. Meanwhile, distribution maps(

Figure 12) of various elements were generated using in - situ micro - zones. It can be clearly observed from

Figure 12 that the distribution of Cr was remarkably similar to that of Ca, Fe, Mn and Ni. In different regions of Cr slag field soil, the positions with higher Cr content tend to have relatively higher Ca, Fe, Mn and Ni contents. This finding is highly consistent with literature reports: previous studies have confirmed that the spatial coincidence rate between Cr hotspots and soil Fe-Mn nodules exceeds 80%, revealing a strong affinity between Cr and Fe-Mn oxide minerals [

38].This indicates that Cr is not only uniformly distributed in soil particles in Cr slag field soil environment, but also closely interacts with minerals containing Ca, Fe, Mn and Ni. Cr and Ca, Fe, Mn, Ni showed positive correlation, and some of them reached significant correlation, which further confirmed the results of in-situ micro-zone distribution map, indicating that Cr and these elements in chromium slag field soil not only closely related in spatial distribution, but also had significant positive correlation in content.

This relationship may be due to the symbiotic relationship or coprecipitation between Cr minerals and minerals containing Ca, Fe, Mn and Ni. For example, some iron and manganese oxide minerals have large specific surface areas and abundant surface active sites, which can adsorb or coprecipitate Cr (VI) [

39]. At the same time, these minerals may also naturally contain Ca, Mn and Ni, resulting in their distribution in the soil showing a high degree of consistency [

40]. Or redox coupling: Fe and Mn are important oxidation-reduction elements in soil, and their oxidtion reduction state changes will affect the oxidation-reduction potential of soil. However, the stability and mobility of Cr (VI) are closely related to the oxidation-reduction environment of soil. In chromium slag field soil, there may be oxidation-reduction coupling between Cr (VI) and Fe, Mn, etc., that is, the oxidation-reduction process of Fe and Mn will affect the reduction or oxidation of Cr (VI), so that their distribution in soil has strong correlation. For example, under reducing conditions, Fe²

+ may reduce Cr (VI) to Cr (III), and this process may be influenced by elements such as Mn in the soil, resulting in similar patterns in their distribution [

41].

Cr and Mg, Al, Si, K had different degrees of close relationship, in-situ micro-zone distribution map showed that Cr and Mg, Al, Si, K distribution difference is big, there is no obvious similarity, at the same time correlation thermal map Cr and Mg, Al, Si, K correlation were weak, even may be negative correlation, and did not reach significant level. This and in-situ micro-zone distribution map results mutually confirm, it showed that Cr and these elements in chromium slag field soil correlation was not obvious. Cr (VI) has strong oxidation and mobility, and is easily affected by oxidation-reduction conditions, pH value and other factors in the soil environment, and migration and transformation, while Mg, Al, Si, K and other elements in the soil chemical behavior is relatively stable, mainly involved in soil structure construction, ion exchange and other processes [

42], their mobility and chemical activity are significantly different from Cr (VI), so the distribution in the soil does not show obvious correlation.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1 Soil Sample Collection

Three representative samples BC-36-3, BC-36-4 and BC-35 were collected to cover the Cr(VI) concentration gradient and Cr(VI)/Cr ratio difference, which provided a basis for the subsequent macro-micro mechanism study. Each group of about 1000g samples were collected strictly according to the principle of spatial heterogeneity of site pollution. After ventilation and natural drying, the soil mineral structure and Cr(VI) occurrence form were kept stable, and then litter, stones and other impurities were removed through 10 mesh sieve to ensure the purity of matrix. After coarse screening, the soil blocks are ground by mortar and sieved by 100 meshes to form fine soil samples with uniform particle size, which effectively reduces particle effect interference. Finally, the sieved samples were sealed in sterile containers and stored in the dark to isolate the influence of external environment such as humidity and oxidation conditions on Cr(VI) morphology.

A vertical soil profile was collected around the chromium slag site in north China. After collection, the soil samples were fixed and transported back to the laboratory to ensure they remained intact without loosening. Once air-dried, an in-situ micro-XRF measurement was conducted on a relatively flat vertical surface of the samples.

3.2. Chemicals and Reagents

Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, AR), dipotassium hydrogen phosphate (K₂HPO₄, AR), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH₂PO₄, AR), anhydrous sodium carbonate (Na₂CO₃, AR), hydrochloric acid (HCl, AR), citric acid (C₆H₈O₇,AR), and ferrous sulfate (FeSO4·7H2O, AR) were all purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. , China; anhydrous magnesium chloride (MgCl₂, analytical grade) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China.; fulvic acid (C₁₄H₁₂O₈, 95%) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. , China Ultrapure water was used as the experimental water.

3.3. Determination of Basic soil Properties

Sample determination method: using a pH meter (Five Easy Plus FP 20, Mettler Toledo, Switzerland) soil pH was measured at a soil: water ratio of 2:5 (g/mL). Total organic carbon (TOC) content of the soil was measured by TOC analyzer (MultiN/C3100, AnalytikJena, Germany). Cr(VI) was extracted with alkali solution using improved HJ1082-2019, combined with ICP-OES for determination of Cr(VI), as follows: 0.5 g soil sample was accurately weighed and transferred into a 250ml volumetric flask, and added 10.0 ml of alkaline extraction solution in turn.(30g/L Na

2CO

3 +20g/L NaOH), 1ml MgCl

2 solution (80mg/ml), 0.5 ml buffer solution (17.42mg/ml dipotassium hydrogen phosphate +13.6mg/ml potassium dihydrogen phosphate), heated in water bath at 94

oC, 240r/min, cooled to room temperature, filtered into 100ml volumetric flask, adjusted pH to acidic with concentrated nitric acid, then constant volume to the marking line, and tested by ICP-OES. The total chromium content in soil was determined according to EPA 3050B method [

43]。

3.4. Soil Elements Distribution DETERMINATION

To investigate the distribution patterns of chromium (Cr) and other heavy metals in soil, soil samples underwent non-destructive two-dimensional elemental scanning using an in situ micro-area X-ray fluorescence spectrometer. The analytical tool utilized was a two-dimensional bench-top in-situ micro X-ray fluorescence spectrometer developed by the National Research Center for Geoanalysis, China. It was equipped with a focusing capillary lens (Powerflux PFX-Beam, X-ray Optical Systems, USA) as a microbeam X-ray source, a rhodium target as the anode target [

44], , and had a focal spot size of approximately 30 μm × 30 μm. Silicon drift detectors (SDD, Vortex EX-60SDD, SIINano-Technologies, USA) were employed, providing a resolution of 130 eV at 5.9 keV (FWHM), with the light tube positioned at a 45° angle to the detector and mounted above a three-dimensional control sample stage. The excitation voltage was 48 kV and the current was 0.8 mA. Initially, energy calibration of the instrument was conducted using copper foil. Subsequently, soil samples were scanned at points for 300 seconds to identify characteristic spectral lines without interference from other elements [45-47], and regions of interest corresponding to characteristic peaks were outlined. A scanning range of 6000 μm ×1500 μm on the soil profile was chozen, and stepsizes were set to 100 μm both horizontally and vertically. Each scanning point was analyzed for 5 seconds.

3.5. Experiment of Influencing Factors

In order to explore the influence of various factors on Cr(VI) content in soil, experiments were carried out under the conditions of pH value, organic matter (fulvic acid, citric acid) addition, FeSO4 addition, temperature, humidity and soil particle size, and the duration of each experiment was set to 45 days.

Experiment on the influence of pH value: Three contaminated soil samples were selected, and the pH value of the soil was adjusted to different levels such as 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11 and 12 respectively by adding acid-base regulator, and the content of Cr (VI) in the soil under each pH value was determined.

Influence of organic matter experiment: Different amounts of fulvic acid and citric acid were added to the three selected polluted soils respectively, and the addition amounts were set to 0, 15, 30, 45mg/kg, etc., and the changed in the content of Cr (VI) in the soil were measured after the addition.

FeSO4 Effects Experiments: Various amounts of FeSO4 were added to the three selected contaminated soils. The addition gradients were 0, 100, 200 300mg/kg, etc. Since Fe(II) reduction of Cr(VI) mainly occurred in anaerobic environments, the samples were adjusted and sealed. The changed in the content of Cr(VI) in the soil were measured.

Temperature influence experiment: Three selected contaminated soils were cultured at -20 ℃, 0 ℃, 4 ℃ and 30℃ for 45 days, respectively, to determine the content of Cr(VI) in the soil, and analyze the influence of temperature on Cr(VI) transformation.

Humidity influence experiment: The selected three contaminated soils were first heated in a low temperature (35℃) drying oven until completely dry, and then different amounts of ultra-pure water were added to prepare soil samples with different moisture content. The content of Cr (VI) in soil was determined under different humidity conditions.

Soil particle size influence experiment: Three contaminated soils were roughly ground and passed through the standard soil test screens of 10 mesh, 60 mesh, 100 mesh and 200 mesh respectively to collect soil samples of different particle sizes. The content of Cr(VI) in soil with different particle size was determined, and the influence of soil particle size on the content of Cr(VI) was analyzed.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S. and S.Z.; methodology, S.Z., Y.Z. and B.Z.; validation, S.Z., J.C. and Z.Y.; investigation, S.Z. and Y.S.; resources, Y.S. and M.P.; data curation, S.Z., J.C. and J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.S.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z. and Y.S.; funding acquisition, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.