1. Introduction

The high production costs and environmental impacts caused by the intense use of oil and its transformation give rise to the development of alternatives based on plant biomass and its byproducts and residues, which are low-cost, sustainable and have a less harmful effect on the environment [

1,

2]. The set of renewable biomasses is composed of several products of different chemical natures, including carbohydrates, such as cellulose, hemicellulose, starch and lignin [

3,

4,

5]. These compounds are available on a larger scale as plant materials and agribusiness residues. Large volumes of wastewater and organic waste are generated in the processing of starchy agricultural products (potatoes, yams, corn, etc.). The industry in this sector has been under pressure to meet wastewater quality limits. In this context, efforts to reduce waste by recovering it through the generation of products and derivatives. Starch and lignocellulosic biomass are saccharide raw material, highlighted by its polymeric structure based mainly on glucose and complemented by other saccharides. Their degradation produces smaller molecules, particularly water-soluble, meaning potential for valorization via different chemical and biochemical processes.

For that, solid catalysts are used to decompose polymeric structures into monosaccharides, which in an operational sequence under moderate temperature and pressure can be hydrogenated to form polyhydric alcohols, especially sorbitol (polyol C6) [

7,

8]. Under more severe conditions, it is possible to process the catalytic hydrogenolysis of polyols and their derivatives, producing, in the case of sorbitol, lower-chain polyols (xylitol, arabitol, erythritol, glycerol, ...), glycols (propanediols, ethylene glycol, ...) and monoalcohols [

9].

Water waste, as low added value raw materials, require processing that can make sense in a context of low operating costs. In this area, the combination of solar energy and thermochemical processes appears to be a promising and sustainable route. Solar energy can provide thermal support for isothermal operations at moderate and high temperatures, which in addition to ensuring hydrogenation, provides the energy supply for the electrolysis that produces green H2, the process reactant.

Conventionally, the heat required for thermochemical processes can be obtained electrically or directly by the combustion of fossil fuels [

10]. However, for this purpose, the option of concentrated solar energy adds sustainability with high efficiency, in addition to reduced costs in its operations. In these cases, devices with specific design requirements serve to accommodate concentrated solar radiation [

11,

12]. For such purposes, as an operational prediction, considerable attention is recommended, through predictions based on heat transfer modeling in these systems [

13].

The use of solar energy has been adopted to promote hydrothermal processes [

14], where biomass-water mixtures maintained in the liquid phase in suspension or dissolved are heated to moderate and high temperatures (from 200 °C to 800 °C) and high pressures (from 50 to 400 bar)[

15,

16]. Soluble carbohydrate processing is carried out at moderate temperatures allowing the production of acids, polyols, glycolysis and alcohols.

Originated from starch or cellulose by chemical or enzymatic hydrolysis, or by heterogeneous catalysis, the glucose monomer or its oligomers can be transformed by hydrogenating catalytic routes that promote production of polyols and their derivatives [

17]. The hydrogenolysis of polyols occurs with the breaking of C-C and C-O bonds and addition of hydrogen. In this domain, the main activators are the catalysts Ru [

18,

19], involving the alkaline promoters CaO, Ca(OH)2 and NaOH, and prepared on different supports such as silica, zeolite, alumina, titanium dioxide, carbon nanofibers and activated carbon [

20,

21].

In the present work, the thermocatalytic hydrogenolysis of aqueous residues from the processing of starchy biomass was carried out in a slurry reactor with a Ni-Ru catalyst supported on activated carbon. The experimental results are presented and evaluated using kinetic methodology. The semi-batch reactor was operated jacketed with thermal fluid heated by concentrated solar energy, providing different isothermal conditions, characterizing the influence of temperature on product selectivity in terms of participation of polyols and glycols. The information obtained should serve as a basis for scaling the production of the selected components, constituting a continuous process, also maintained by solar energy, and offering different selectivity options through operations in a trickle-bed reactor.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Formulation of catalyst

The Ru-Ni catalyst was prepared and characterized, then formulated as powder for use in reaction evaluation. Activated carbon (AC) used as catalyst support was produced by processing the endocarp of coconut (Coccus Nucifera) with Al2(SO4)3 and steam. The ratio of activator:precursor effect on the activation were considered, as well as the carbonization temperature, retention time and type of activation.

The catalyst was prepared by the wet impregnation method of the support with a solution of the active metal precursor salt. First, the activated carbon suspended in the nickel nitrate solution (Ni(NO3)2.6H2O) remained under stirring for 48 hours, when it was subjected to slow drying at 333K for 10 hours and then at 373K for 12 hours. Then, the material was calcined in a furnace at 773K for 5 hours, under an argon atmosphere at a flow rate of 1.3 cm3/min/g of support. Subsequently, a second impregnation with ruthenium chloride (RuCl3.3H2O) was performed with the calcined material and the drying step was repeated, after which a reduction was performed for 3 hours under a H2:Ar/1:1 gas flow at a flow rate of 1.3 cm3/min/g of support.

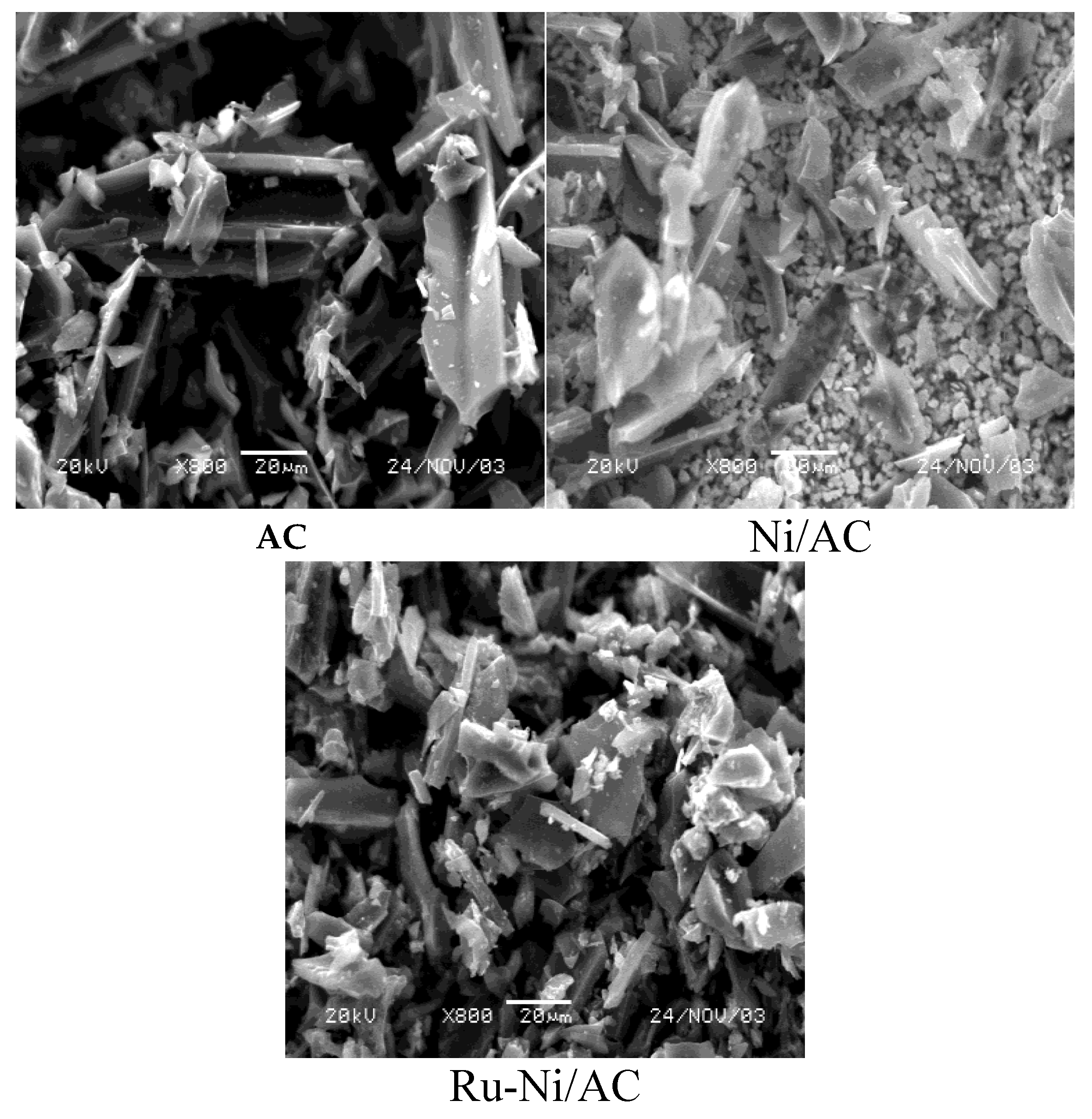

The materials, including the activated carbon (AC), supported nickel and the bimetallic catalyst were characterized. In particular for the support, thermal analysis (TG/DTG) measurements were performed, while textural analysis, X-ray diffraction and SEM were applied for AC, Ni/AC and the Ru-Ni/AC catalyst.

The stability of the material was evaluated by thermal analysis in an inert atmosphere, with respect to mass loss. The crystallinity of the materials was evaluated by XRD (Siemens, model T-5000 diffractometer) with analysis by the powder method, and detection of diffracted rays versus incidence angles. The textural characteristics of the materials were measured by gas adsorption (BET-N2, adsorption, 77 K), following the vacuum degassing procedure, using a surface area and pore volume meter ASAP 2002. The surface micrographs of the material under analysis were highlighted by SEM with a Joel model JXA 840A instrument equipped with an electron probe microanalyzer.

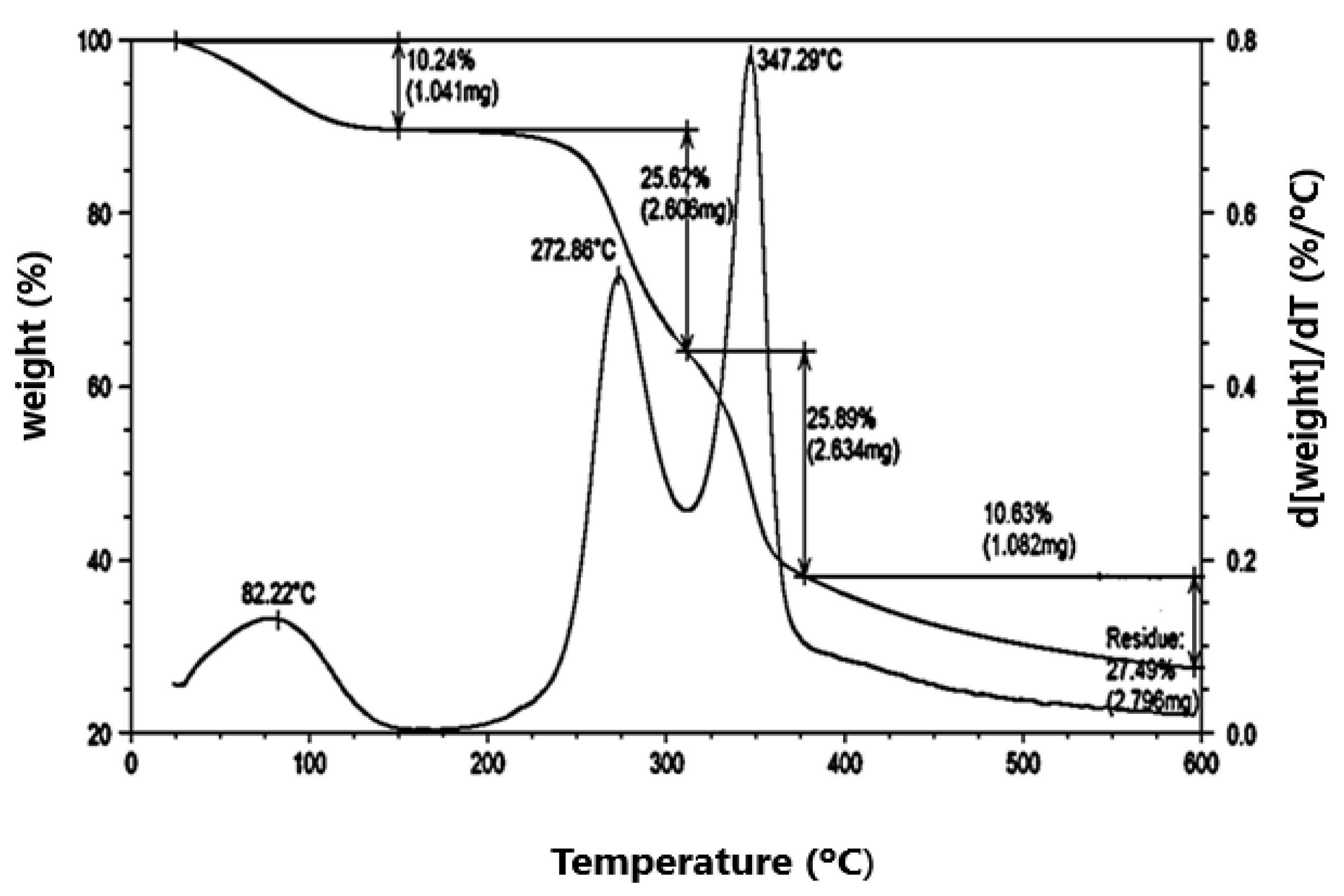

3.2. Experimental evaluation

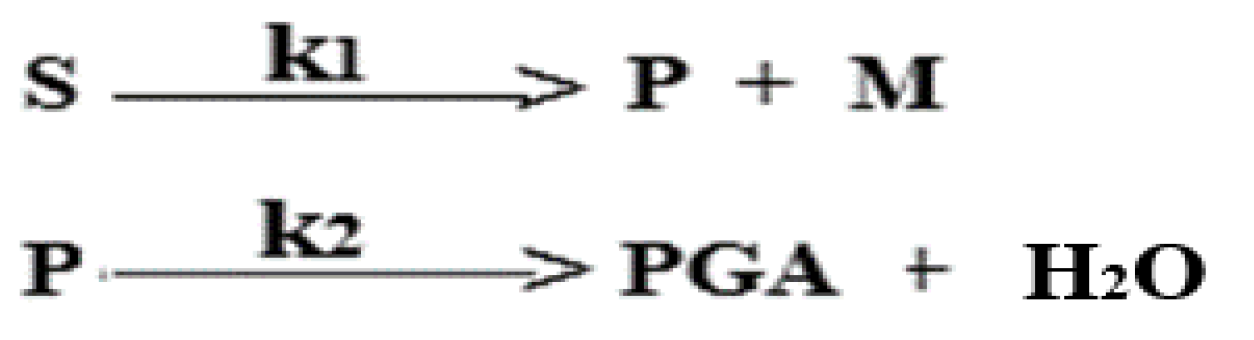

Experiments were carried out in a slurry reactor (

Figure 7a) in presence of the [Ru/1.0% - Ni/10.0%]wt./activated carbon, in order to identify its activity, through the different products and reaction steps, and establish the kinetic basis of the hydrogenolysis process. Considering the thermochemical characteristics of the hydrogenolysis process, carried out at different temperatures (453 K, 473 K, 493 K) in the range above 373 K, the use of a solar thermal system (TS,

Figure 7b), developed in the laboratory, was proposed. The carbohydrate wastewater hydrogenolysis experiments were carried out by processing an aqueous solution of saccharides (80.0 g/L) obtained by acidic starch hydrolysis (Brazilian hybrid corn, Corn Products Brasil Ltda., Cabo, PE) at 343 K with H

2SO

4 5% wt., providing a saccharide solution (oligosaccharides, glucose).

The compositions of the liquid phases obtained during the processing were determined using high liquid performance chromatography (HPLC). The samples obtained by acidic starch hydrolysis and used for the feeding saccharide solution were analyzed using a Lichrosorb column (250x8 mm od, Lichrosorb, NH2, Merck, Germany; mobile phase 80%/20%:acetonitrile/water). The analysis of hydrogenolysis products collected during the operation of the slurry reactor were performed with a Biorad column (250x8 mm od, Aminex HP-X, USA; mobile phase deionized water).

3.3. Thermal control and process evaluation

Predictions of the thermal behavior obtained with the supply of energy to the reactor were formulated. The effects on the reaction medium by heat transfer provided through the jacket occur via thermal fluid heated by the solar energy provided by the TS.

The solar thermal system (TS) operates under radiation from the parabolic trough solar concentrator using the thermal fluid in a closed cycle, including the absorber and the reactor jacket. The fluid temperature in the system parts is set and controlled according to the fluid flow rate and the absorber length (1.2 m - 3.6 m). The thermal fluid has the following properties: mineral oil, density (ρF) 824 kg/m3, specific heat (CpF) 2.34 cal/gK and heat transfer coefficient (h) 300 w/m2.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Support and catalyst characterizations

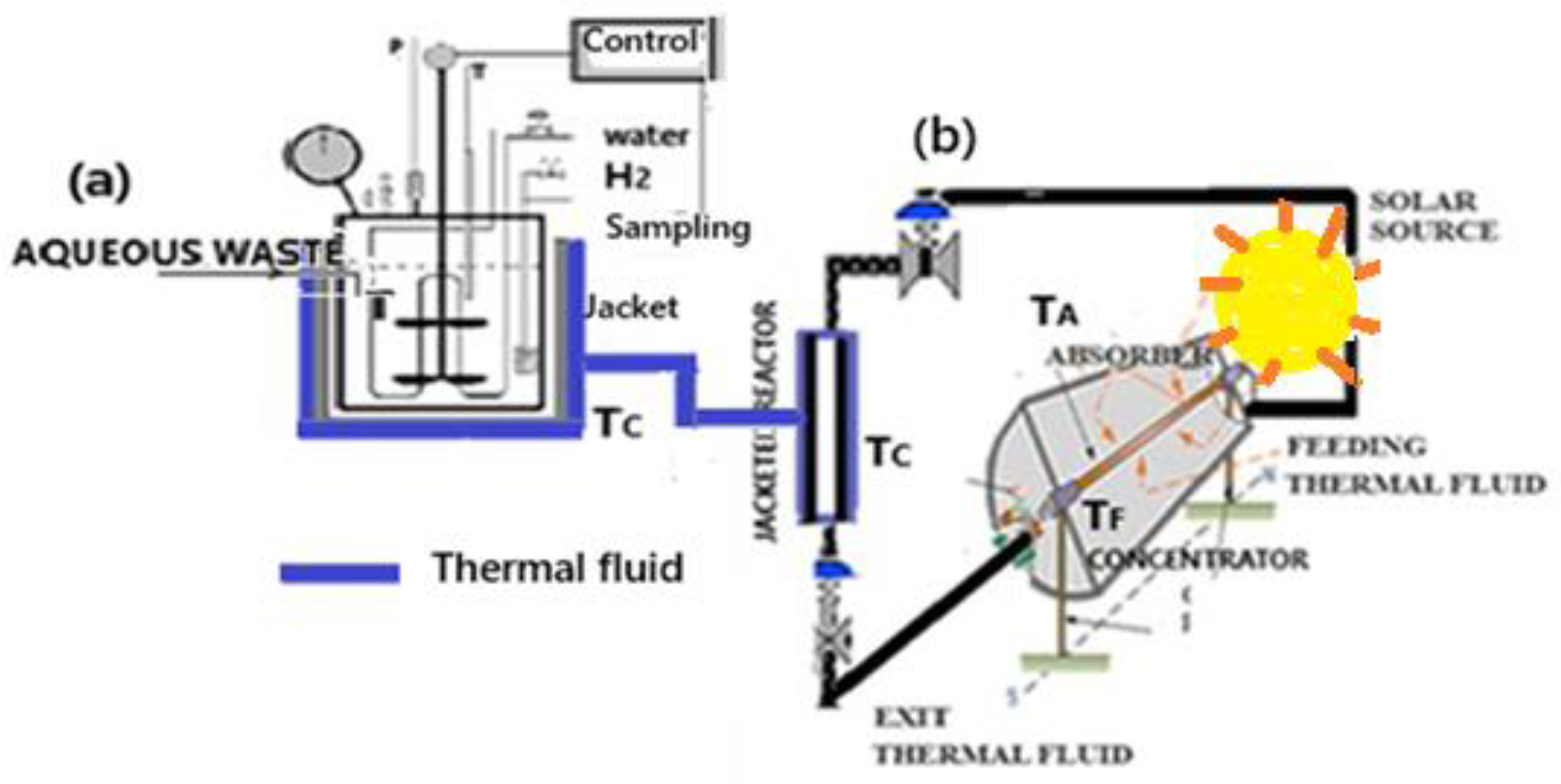

The activated carbon, prior to its use as catalyst support, had its thermal, textural and surface acidity characteristics measured. The thermograms composed of the TGA/DTG curves (

Figure 1) indicated mass losses between 25°C and 600°C, involving four stages of decomposition. The first, which varies from around 25°C to 150°C, corresponds to water loss, while the other two peaks located between 200°C and 400°C, are related to the degradation and volatilization of the components of carbonaceous materials (hemicellulose, cellulose, lignin).

The depolymerization of the predominant cellulose occurs, accompanied by the decomposition of lignin. The peaks corresponding to hemicellulose degradation are around 273ºC, and cellulose decomposition, around 347°C. The last stage is related to the loss of residue and extends up to 600°C.

In view of the use of activated carbon for the deposition of metals via wet impregnation, an analysis of its surface charge was carried out, where a positive surface charge was determined, indicated by a P

HPCZ = 6.8, which guided the use of pHs higher than this value for the impregnating solution of Ni and Ru precursor salts. Subsequently, the activated carbon subjected to textural analysis (adsorption-desorption, BET-N

2) revealed a surface area of 746 m

2/g and pore volume of 0.51 cm

3/g. After metal precursor impregnation and calcination/reduction stages, textural analyzes were carried out indicating the results in

Table 1. Variations in the textural characteristics of the CA support were observed, including a decrease in the specific surface area, consistent with the reduction in pore volume.

Comparatively, it is observed that the deposition of the metallic phases of the catalyst promoted a decrease in the surface area of the activated carbon, where the surface área of the catalyst was 22.7% lower. This reduction is compatible with the lower porous volume (21.6%). These systems have their structures observed by SEM in terms of their morphologies, revealed in

Figure 2 by the micrographs of the activated carbon, the supported nickel and and the Ru-Ni/AC catalyst.

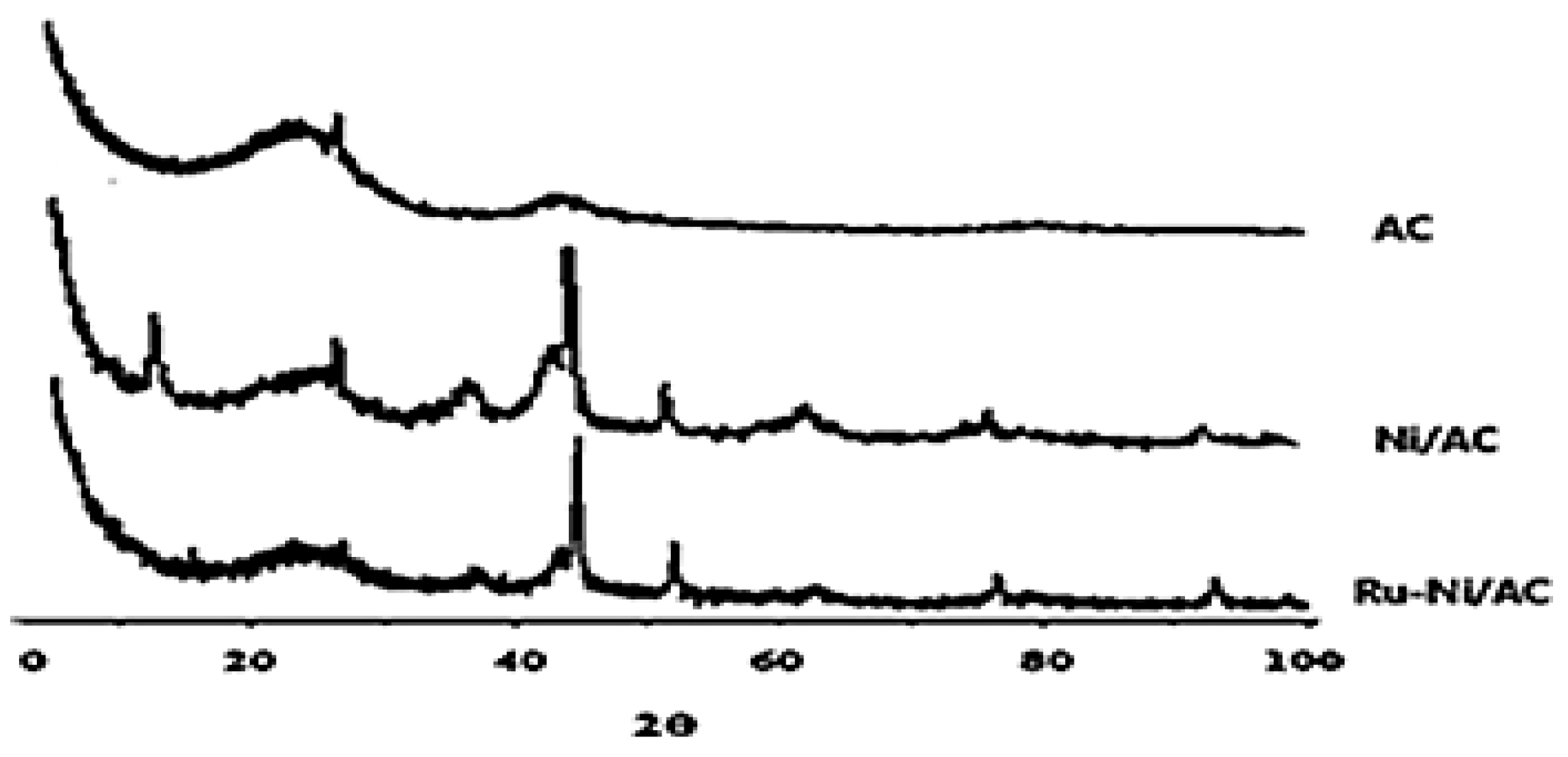

According to the micrographs, it can be observed that the activated carbon and the supported materials present moderate structural changes, considering the systems with incorporated Ni and Ru-Ni. These materials were characterized by X-ray diffraction, and their diffractograms are represented in

Figure 3.

The ruthenium phase incorporated into the supported nickel material was prepared to give rise to the catalyst [Ru(1.0 wt%)-Ni(10.0 wt%)]/AC. After the introduction of nickel, a decrease in the crystallinity of the system was observed. This may be associated with the X-ray absorption range of ruthenium (absorption coefficient of 183), compared to nickel, with a value of 286. Thus, it is indicated that ruthenium crystals, as they absorb more radiation, diffract less and reveal lower crystallinity.

4.2. Process evaluation

4.2.1. Starchy waste water

The aqueous solution of oligosaccharides, representing the waste water from starch processing, was obtained from the acid hydrolysis of starch (Brazilian hybrid corn, Corn Products Brasil Ltda., Cabo, PE, Brazil, 343 K, H

2SO

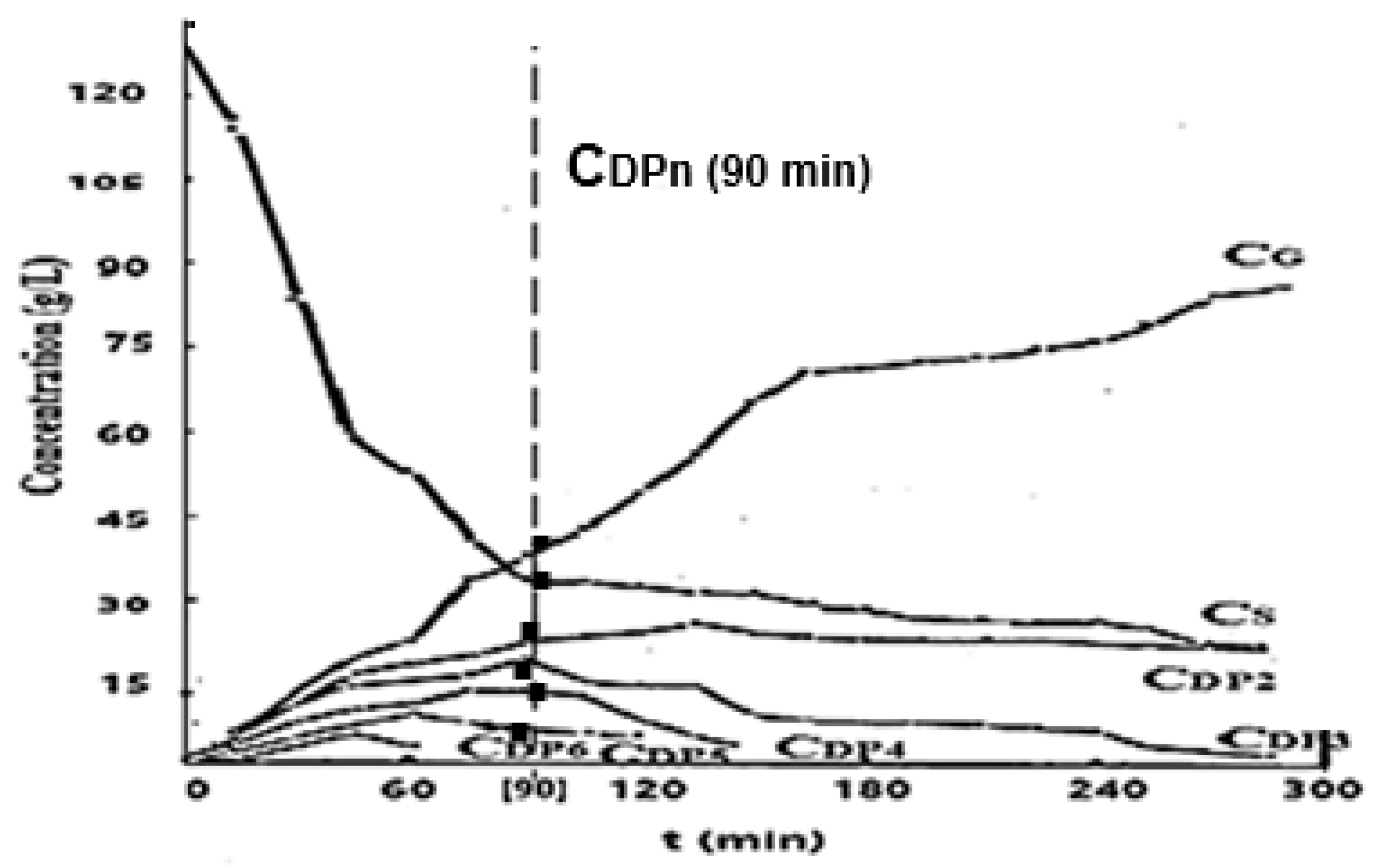

4 5% wt.), providing a saccharide solution (oligosaccharides, glucose) with an initial concentration of 130 g/L. In their analysis, mixtures of saccharides from acidic solutions showed the occurrence of oligosaccharides of different degrees of polymerization (DPn), decreasing up to the monosaccharide glucose.

Figure 4 shows the evolution of saccharide concentrations in the acid hydrolysis operating domain for up to 300 minutes.

To characterize the residual saccharide solution from the processing of starchy materials, the composition reached after 90 minutes of operation was taken as a basis (

Figure 4). The solution composed of oligosaccharides presented increasing concentrations of 4.0 g/L to 43.0 g/L, from DP

6 to glucose (DP

1).

4.2.2. Hydrogenation and thermal operation control

The thermocatalytic processing of the oligosaccharide aqueous medium from starch biomass was carried out in the slurry reactor coupled to the TS system (

Figure 5) at isothermal operation maintained by solar energy. The formulated Ru-Ni/AC catalyst was used in the following operating conditions: reactor volume 0.70 ×10

-3m

3, saccharide concentration 80.00 kg/m

3, catalyst 9.80×10

-3 kg, hydrogen pressure 50.0 bar, 620 rpm, at 453 K, 473 K and 493K, operating time 4 hours.

In the TS system, as a control of the reactor heating, the temperature (T) predicted for the hydrogenolysis operation is introduced into the thermal balance (

Figure 1), allowing to determine the temperature of the thermal fluid to be reached in the jacket. To this end, the steady-state temperatures of the thermal fluid at the absorber outlet (T

F) heated by solar energy (T

A) and supplyed in the jacket (T

C) are calculated. The temperature in the reaction medium (T) imposes a relationship with T

F and T

C (Equation 1) obtained from the calculations using the solutions of the steady state energy balance equations for the thermal fluid in the sectors of the TS System (absorber, jacket, reactor), written in the Apendix A (Equations A

1 and A

2).

where

λ’ = URAR/QρFCF, with

U the heat transfer coeficiente, and

A and

V the heat transfer área and the volume of termal absorber (

UA , AA ,VA) and of reactor jacket (

UR , AR ,VR), respectively.

The catalytic processing of hydrogenolysis was preliminarily evaluated in terms of its performance (

Xs, conversion) and according to the reaction temperature to be adopted (T) in the operation. The conversion prediction is valid as an indication for the TS system, which can thus promote the supply of energy to the thermal fluid, which is transferred to the reactor by this same fluid through the jacket, in order to reach the reaction temperature. From the mass and energy balances (Equations 2, 3) predictions of operational functionality in terms of temperature are obtained.

The run is predicted to proceed from t

0 = t at 303 K, with the process at an initial conversion level

XS ≈ 0, and continuing to reach the reaction temperature, giving the corresponding conversion (

XS(T)). As a guide to conducting reactor runs, the predicted conversion profile as a function of temperature is listed in

Table 4.

Predictions for operations at the three temperatures 453 K, 473 K and 493 K indicate conversions that should be situated at levels of 43%, 52% and 74%, showing possibilities of processing with solar energy input via thermal fluid.

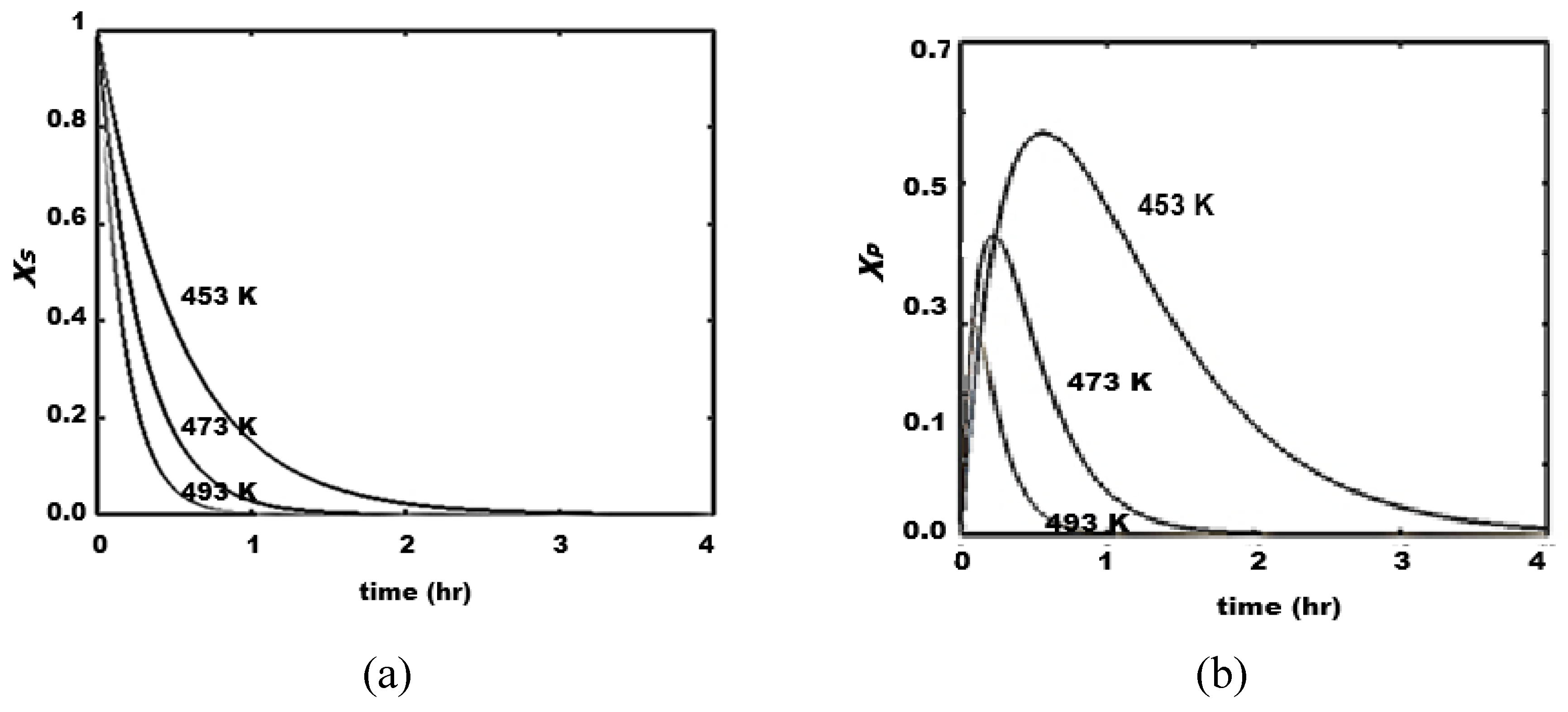

4.2.3. Hydrogenolysis evaluations

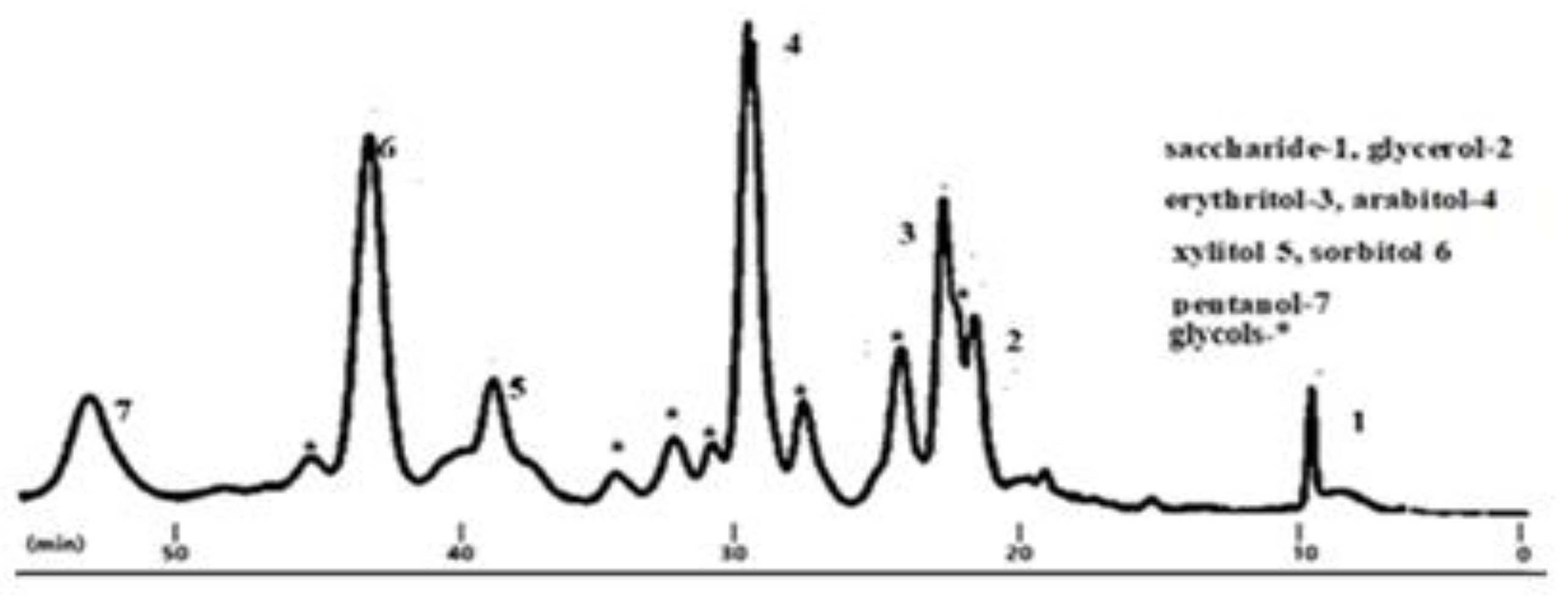

Under the isothermal conditions established at 453 K, 473 K and 493 K, hydrogenolysis operations were conducted for up to 4 hours, accompanied by sampling of the liquid phase every 60 min. In the samples, analyzed by HPLC, saccharides, polyols and glycols, were identified and quantified. Light alcohols (methanol,..) were analyzed by GC in gas phase.

Figure 2 shows type HPLC chromatograme where the products were saccharides (glucose and sorbitol), polyols (erythritol, xylitol, arabytol, glycerol), and glycols (tetrols, diols), and pentanol.

The results of the quantitative analyses of product samples from 453 K to 493 K are listed in

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4, in terms of mass concentrations as a function of operating time.

The evolution of concentrations initially indicates the decomposition of starchy oligosaccharides formed by glucose units. In this case, activated carbon, together with adsorbed hydrogen and water, exerts a hydrolytic action on the disaccharide units of amylose, which were decomposed by reaction on the glycosidic bonds to form glucose, which, under the action of nickel in its C = O bond, led to the production of sorbitol. This C6 polyol, in the presence of ruthenium, was subjected to hydrogenolysis, providing smaller polyols, glycols and monoalcohols, where methanol was predominant [

22]. The effect of Ru involve the cleavage of the –C–C– bond in short-chain polyols, and on the C-OH bond, where adjacent free OH groups in close proximity to the catalyst are deoxygenated.

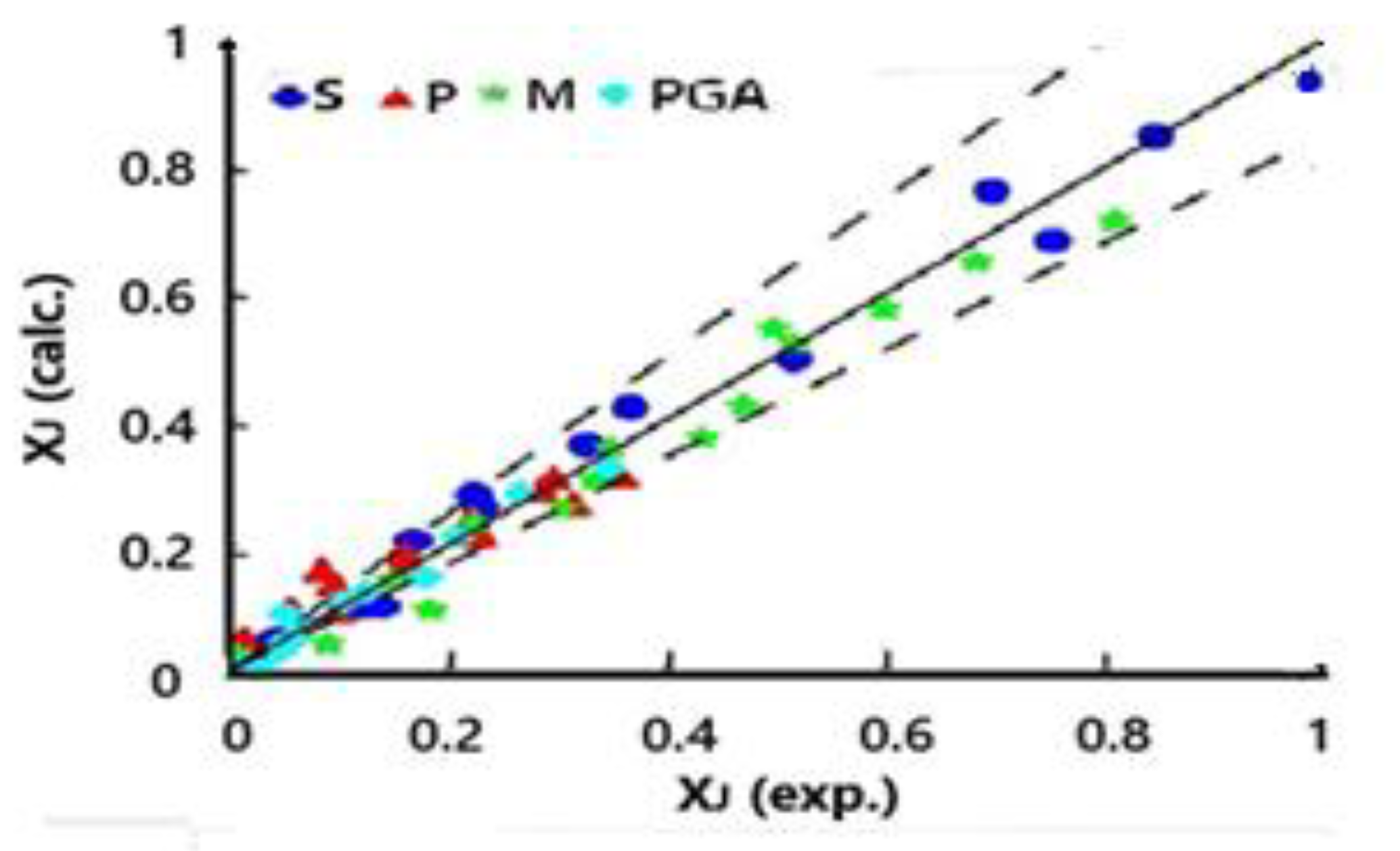

4.3. Kinetic evaluation

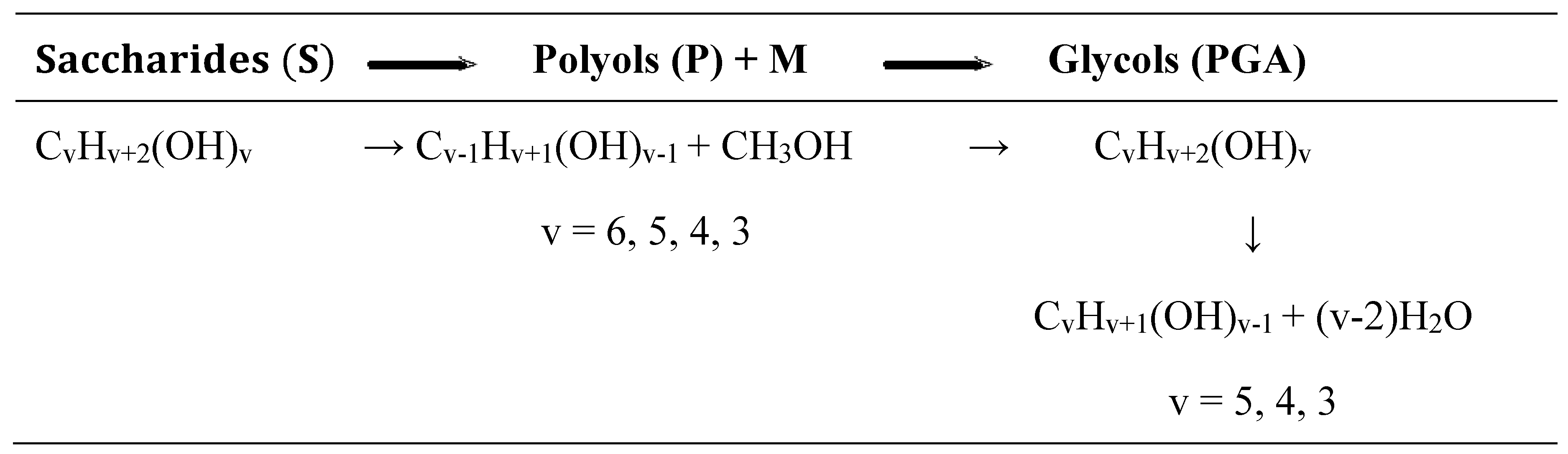

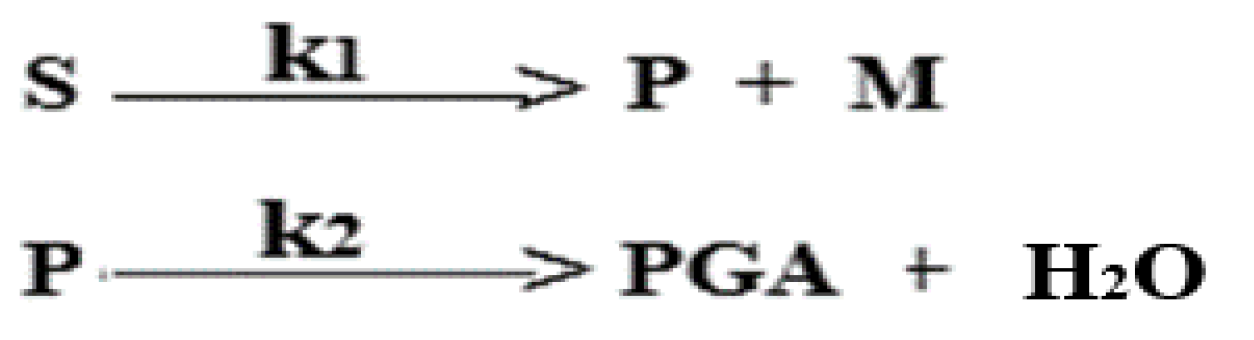

The experimental evidence led to the proposal of a reaction scheme for the process, where the chemical equations for hydrogenation of glucose and for hydrogenolysis C - C (polyols) and C - O (glycols) are written as follows:

In the reaction scheme, saccharides plus sorbitol are represented by S, methanol by M, while C5, C4, C3 polyols and glycols are identified as P and PGA, respectively. Thus, a reaction scheme to represent the kinetics evolution is summarized as:

Following the proposed mechanism of the reaction scheme represented, and in order to adapt the temporal evolution of the process in terms of its main components, the data in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 were grouped as normalized mass fractions in relation to the total mass quantified at each sampling time (X

J = C

J/∑C

J).

Considering the slurry reactor, where the liquid phase is saturated in H

2, operating in isothermal way heated by the thermal fluid supplied by the TS, the mass balance equations are written as (Equation 4):

where

ρcat is the density of catalyst, and

and

(

J = S, P, M, PGA) are the concentrations and the global reaction rates of the component based on the reaction scheme. The reaction rate expressions of each component, derived through the Langmuir-Hinshelwood approach, have the forms (Equation 5):

where

ki (

i = 1, 2) and

KJ are the pseudo reaction constants and adsorption constants, respectively.

The equation system formulated for S, P, PGA and M (Equation 15) was solved by the 4th Runge-Kutta method, where the solutions obtained for the operations at the three temperatures are expressed as in function of time.

The proposed mechanism for the process with consecutive steps passing through the intermediate P, clearly highlights the thermal sensitivity attributed to the step of its production (step 1). Thus, the highest level of P profile occurs at the lowest temperature, and it is not favorable to the production of PGA, as a consecutive step. The consumption of saccharides and the production of glycols (PGA) and methanol increase from 453 K to 493 K, while the production of P polyols reaches a higher level at intermediate times (1.5 – 2.5 hr).

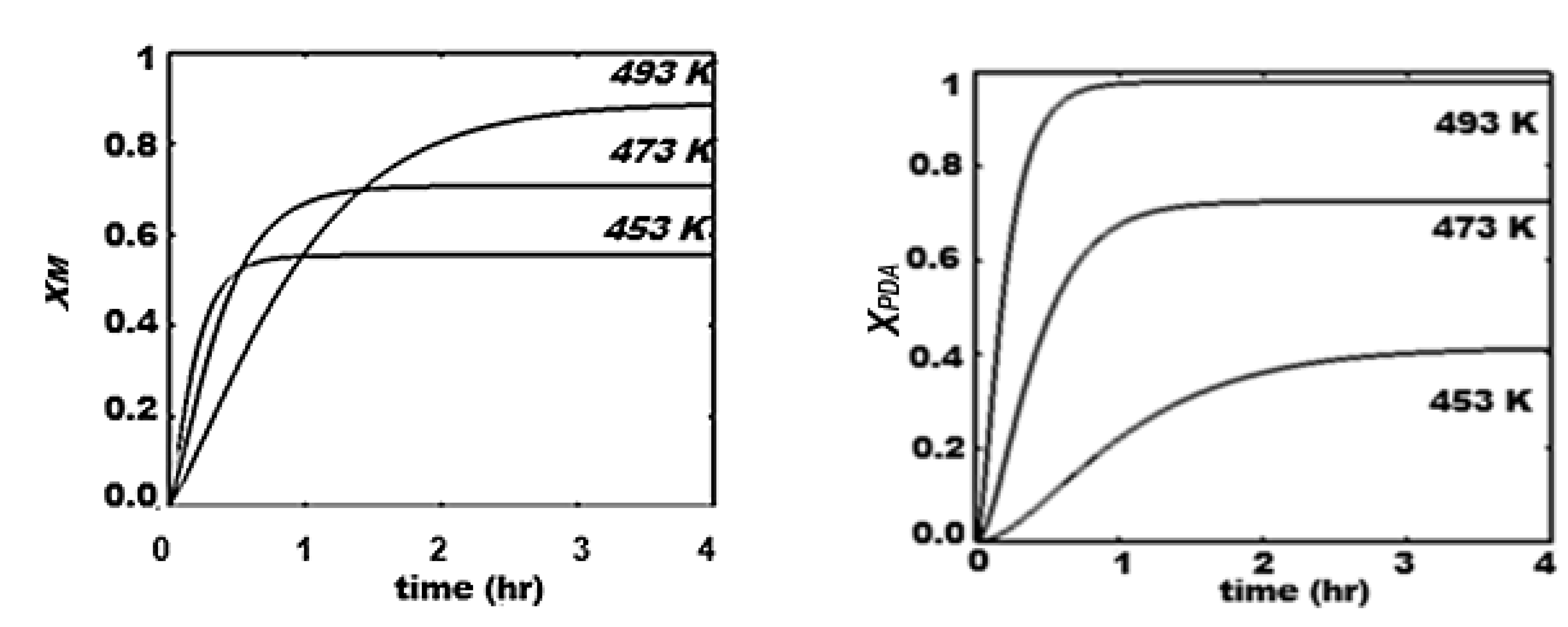

Calculated weight fractions

were compared to the experimental data (

) by using an objective function (

).

Figure 6 shows a parity graph in terms of the calculated (model’s prediction) and experimental concentrations of saccharides and products in the liquid phase for different operation times at the three temperatures.

The specific reaction rates were calculated by numerical adjustment, applying <F

ob> values as optimization criterion. In

Table 5 for the three temperatures practiced k

1 and k

2 values are listed.

Based on the values of the specific reaction rates the defined kinetic selectivities (SJ) for polyols (SP) methanol (SM) and glycols (SPGA) are calculated as follow: (, reaching their highest values: , and at 493 K.

The temperature effect provides activaton energies related for C − C hydrogenolysis on polyols, highlighted by the production of methanol, activated with 46.71 kJ/mol, higher than that of the C − O hydrogenolysis, involving a value of 26.92 kJ/mol, activation energy required in the catalysis of the steps that convert polyols into glycols [

23].

The activation energy value obtained for the hydrogenation of glucose with Ru:Ni/MCM-48 was approximately 70 kJ mol−1 [

24], indicating a reaction rate controlled by the kinetics on the metal surface, while glucose to sorbitol in the presence of ruthenium nanoparticles supported by HY zeolite was activated in the energy range of 24~49 kJ/mol, a level of values considered as apparent activation energy [

25].

4. Conclusions

Experimental data on the hydrogenolysis water waste of starchy saccharides were obtained in reaction operations performed with a supported carbon catalyst in a jacketed slurry reactor powered by solar energy using a thermal fluid.

Experimental evaluations carried out under a chemical-kinetic regime at 353 K - 393 K and 50.0 bar in the presence of the formulated Ru-Ni/activated carbon catalyst allowed the proposal of a reaction scheme used for kinetic study, including parallel and consecutive steps, involving the production of polyols (polyols, glycols) and methanol. The production rates of these two groups of compounds operated at 473 K, expressed by their specific reaction rates, were quantified in orders of magnitude of 0. 71 h-1 and 1.10 h-1, respectively.

The effect of increasing temperature, with emphasis on the kinetic parameters of the reaction, provides advances in the production stages of methanol and glycols that require the consumption of intermediate polyols.

Based on obtained products glucose, sorbitol, polyols (C5, C4, C3), glycols and methanol the activity of the catalyst in the different related sites, highlihting hydrogen participation, was characterized. The heterogeneous hydrolysis of starchy oligosaccharides in aqueous medium provided high glucose content. The hydrogenation of glucose into sorbitol occurs via the C=O bond activated on Ni, while the hydrogenolysis on sorbitol and other polyols occurs under the main effect of Ru on C-C and C-O bonds.

The information obtained should serve as a basis for scaling the production of the selected components, constituting a continuous process, also maintained by solar energy, and offering different selectivity options through operations in a trickle-bed reactor.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Cesar A. P. Abreu and M. Benachour.; methodology Antônio M. Rocha Neto; software Monica S. Araújo; validation, Nelson M. Lima-Filho, Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, Cesar A. Moraes; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing Cesar A. Moraes; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Please add: This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”.

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TS |

Thermal Solar |

| AC |

Activated Carbon |

| XRD |

X-Ray Diffraction |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscopy |

Appendix A

Appendix A

. Energy balance equations for the thermal fluid

The temperature of the thermal fluid flowing the TS system is predicted to the hydrogenolysis reactor jacket (Tc) considering the steady-state temperatures of the thermal fluid at the absorber outlet (TF) heated by solar energy (TA). The temperature in the reaction medium (T) imposes a relationship with TF and TC (Equation 1).

- in the absorber (T

F, fluid leaving the absorber, λ = U

AA

A/Qρ

FC

F, α = V

A/Q),

- in the reactor envelope jacket (T

C, fluid coming out of the jacket, λ

’ = U

RA

R/Qρ

FC

F, α‘= V

C/Q),

Table A1 shows the thermal operating profiles of the TS sectors, indicating the conditions available to be used in heating the reactor. From the absorber (T

F), under steady-state conditions, the evolution of the temperature in the jacket is observed (T

Cin,T

Cout).

Table A1.

Evolution of the temperature of the thermal fluid in the sectors of the solar thermal system.

Table A1.

Evolution of the temperature of the thermal fluid in the sectors of the solar thermal system.

| Time (min) |

TF (K) |

TCin (K) |

TCout (K) |

| 10 |

608 |

383 |

351 |

| 20 |

697 |

445 |

388 |

| 30 |

728 |

488 |

435 |

| 40 |

745 |

521 |

468 |

| 50 |

748 |

546 |

483 |

| 60 |

748 |

571 |

520 |

| 70 |

748 |

578 |

537 |

References

- Bozell, J.J.; Petersen, G.R. Technology development for the production of biobased products from biorefinery carbohydrates—the US Department of Energy’s “Top 10” revisited, Green Chem. 12 (2010) 539. [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Ruiz, C.; Luque, R. ; Sepúlveda-Escribano, A. Transformations of biomass-derived platform molecules: from high added-value chemicals to fuels via aqueous-phase processing, Chem. Soc. Rev. 40 (2011) 5266. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. The synergistic effects of Ru and WOx for aqueous-phase hydrogenation of glucose to lower diols, Appl. Catal. B Environ. 242 (2019) 100–108. [CrossRef]

- Besson, M.; Gallezot, P.; Pinel, C. Conversion of Biomass into Chemicals over Metal Catalysts, Chem. Rev. 114 (2014) 1827–1870. [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; H. Wang, H. Xin, C. Zhu, Q. Zhang, X. Zhang, C. Wang, Q. Liu, L. Ma, Hydrogenolysis of biomass-derived sorbitol over La-promoted Ni/ZrO 2 catalysts, RSC Adv. 10 (2020) 3993–4001. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. ; Z. Huang, H. Kang, X. Li, C. Xia, J. Chen, H. Liu, Efficient bimetallic NiCu-SiO2 catalysts for selective hydrogenolysis of xylitol to ethylene glycol and propylene glycol, Appl. Catal. B Environ. 220 (2018) 251–263. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S. ; X. Gao, Y. Zhu, Y. Li, Tailored mesoporous copper/ceria catalysts for the selective hydrogenolysis of biomass-derived glycerol and sugar alcohols, Green Chem. 18 (2016) 782–791. [CrossRef]

- Gumina, B. ; F. Mauriello, R. Pietropaolo, S. Galvagno, C. Espro, Hydrogenolysis of sorbitol into valuable C3-C2 alcohols at low H2 pressure promoted by the heterogeneous Pd/Fe3O4 catalyst, Mol. Catal. 446 (2018) 152–160. [CrossRef]

- Vijaya Shanthi, R. ; R. Mahalakshmy, K. Thirunavukkarasu, S. Sivasanker, Hydrogenolysis of sorbitol over Ni supported on Ca- and Ca(Sr)-hydroxyapatites, Mol. Catal. 451 (2018) 170–177. [CrossRef]

- Payakkawan, P.; Suwilai Areejit, Pitikhate Sooraksa, Design, fabrication and operation of continuous microwave biomass carbonization system, Renewable Energy, Volume 66,2014,Pages 49-55,ISSN 0960-1481. [CrossRef]

- Chuayboon, S.; Stéphane Abanades, Solar metallurgical process for high-purity Zn and syngas production using carbon or biomass feedstock in a flexible thermochemical reactor,Chemical Engineering Science,Volume 271,2023,118579,ISSN 0009-2509. [CrossRef]

- Loutzenhiser, P. G.; Anton Meier and Aldo Steinfeld. Review of the Two-Step H2O/CO2-Splitting Solar Thermochemical Cycle Based on Zn/ZnO Redox Reactions. Materials 2010, 3(11), 4922-4938. [CrossRef]

- Lapp, J.; Jane, H. Davidson, Wojciech Lipiński. Heat Transfer Analysis of a Solid-Solid Heat Recuperation System for Solar-Driven Nonstoichiometric Redox Cycles Available to Purchase. J. Sol. Energy Eng. Aug 2013, 135(3): 031004 (11 pages). [CrossRef]

- Ayala-Cortés, A.; Pedro Arcelus-Arrillaga, Marcos Millan, Camilo A. Arancibia-Bulnes, Patricio J. Valadés-Pelayo, Heidi Isabel Villafán-Vidales, Solar integrated hydrothermal processes: A review, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews,Volume 139, 2021,110575, ISSN 1364-0321. [CrossRef]

- Kan, T. et al., Hydrothermal Processing of Biomass, 2014. DOI:10.1201/b17093-7. In book: Biomass Processing Technologies (pp.155-176).

- Lucian, M.; Luca Fiori. Hydrothermal Carbonization of Waste Biomass: Process Design, Modeling, Energy Efficiency and Cost Analysis. Energies 2017, 10(2), 211. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; J. Guan, B. Li, X. Wang, X. Mu, H. Liu, Conversion of biomass-derived sorbitol to glycols over carbon-materials supported Ru-based catalysts, Sci. Rep. 5 (2015) 16451. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L. ; J.H. Zhou, Z.J. Sui, X.G. Zhou, Hydrogenolysis of sorbitol to glycols over carbon nanofiber supported ruthenium catalyst, Chem. Eng. Sci. 65 (2010) 30–35. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. ; H. Liu, Selective hydrogenolysis of biomass-derived xylitol to ethylene glycol and propylene glycol on supported Ru catalysts, Green Chem. 13 (2011) 135–142. [CrossRef]

- Leo, I. M. ; M. López Granados, J.L.G. Fierro, R. Mariscal, Selective conversion of sorbitol to glycols and stability of nickel–ruthenium supported on calcium hydroxide catalysts, Appl. Catal. B Environ. 185 (2016) 141–149. [CrossRef]

- Rivière, M; N. Perret, A. Cabiac, D. Delcroix, C. Pinel, M. Besson, Xylitol Hydrogenolysis over Ruthenium-Based Catalysts: Effect of Alkaline Promoters and Basic Oxide-Modified Catalysts, ChemCatChem. 9 (2017) 2145–2159. [CrossRef]

- Banu, M. , Venuvanalingam, P., Shanmugam, R. et al. Sorbitol Hydrogenolysis Over Ni, Pt and Ru Supported on NaY. Top Catal 55, 897–907 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Kühne, B. ; Herbert Vogel, Reinhard Meusinger, Sebastian Kunz and Markwart Kunz. Mechanistic study on –C–O– and –C–C– hydrogenolysis over Cu catalysts: identification of reaction pathways and key intermediates. Catal. Sci. Technol., 2018, 8, 755–767. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, A.; Nieto–Márquez, A. , Alonso E. Bimetallic Ru:Ni/MCM–48 catalysts for the effective hydrogenation of d–glucose into sorbitol. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017;529:49–59. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.K.; Dabbawala, A.A. , Park J.J., Jhung S.H., Hwang J.S. Selective hydrogen-ation of d–glucose to d–sorbitol over HY zeolite supported ruthenium nanoparticles catalysts. Catal. Today. 2014;232:99–107. [CrossRef]

- Gumina, B.; Francesco Mauriello, Rosario Pietropaolo, Signorino Galvagno, Claudia Espro,.

- Hydrogenolysis of sorbitol into valuable C3-C2 alcohols at low H2 pressure promoted by the heterogeneous Pd/Fe3O4 catalyst, Molecular Catalysis, 446, 2018,152-160, ISSN 2468-8231.

Figure 7.

Catalytic reactor powered by solar thermal system (TS). (a) operational slurry reactor, (b) solar thermal system.

Figure 7.

Catalytic reactor powered by solar thermal system (TS). (a) operational slurry reactor, (b) solar thermal system.

Figure 1.

Thermal analysis of activated carbon from baia coconut endocarp. Thermograms: TGA/DTG curves.

Figure 1.

Thermal analysis of activated carbon from baia coconut endocarp. Thermograms: TGA/DTG curves.

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of activated carbon, supported material (Ni/AC) and catalyst (Ru-Ni/AC).

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs of activated carbon, supported material (Ni/AC) and catalyst (Ru-Ni/AC).

Figure 3.

XRD of activated carbon, monometallic supported material (Ni/AC) and bimetallic catalyst (Ru-Ni/AC).

Figure 3.

XRD of activated carbon, monometallic supported material (Ni/AC) and bimetallic catalyst (Ru-Ni/AC).

Figure 4.

Kinetics of starch solution hydrolysis (CS). Evolution of oligosaccharide concentrations. Analyze HPLC, Lichrosorb column, UV detector, water mobile phase.

Figure 4.

Kinetics of starch solution hydrolysis (CS). Evolution of oligosaccharide concentrations. Analyze HPLC, Lichrosorb column, UV detector, water mobile phase.

Figure 2.

Hydrogenolysis product. Composition of liquid phase. HPLC analysis. Conditions: cat. Ru-Ni/AC, 473 K, 50.0 bar, 180 min.

Figure 2.

Hydrogenolysis product. Composition of liquid phase. HPLC analysis. Conditions: cat. Ru-Ni/AC, 473 K, 50.0 bar, 180 min.

Figure 5.

Concentration profiles in hydrogenolysis of saccharides. Effect of temperature. (a) S, (b) PE, (c) M, (d) PGA. Conditions: , 50.0 bar, 600.0 rpm.

Figure 5.

Concentration profiles in hydrogenolysis of saccharides. Effect of temperature. (a) S, (b) PE, (c) M, (d) PGA. Conditions: , 50.0 bar, 600.0 rpm.

Figure 6.

Parity calculated vs. experimental concentrations of hydrogenolysis components. Effect of temperature. Conditions: cat. (Ru 1.0% wt.-Ni 10.0% wt.)/)/activated carbon, 50.0 bar, 453 K, 473 K, 493 K.

Figure 6.

Parity calculated vs. experimental concentrations of hydrogenolysis components. Effect of temperature. Conditions: cat. (Ru 1.0% wt.-Ni 10.0% wt.)/)/activated carbon, 50.0 bar, 453 K, 473 K, 493 K.

Table 1.

Textural chracteristics of support activated carbon, monometalics supported and bimetalic catalyst.

Table 1.

Textural chracteristics of support activated carbon, monometalics supported and bimetalic catalyst.

| Material |

Sp

(m2/g) |

Vp×102

(m3/g) |

| AC |

746 |

51 |

| Ni/AC |

591 |

41 |

| Ru-Ni/AC |

576 |

40 |

Table 4.

Performance of carbohydrate hydrogenolysis of starch wastewater. Saccharide conversion as a function of temperature.

Table 4.

Performance of carbohydrate hydrogenolysis of starch wastewater. Saccharide conversion as a function of temperature.

| Temperature, K |

303 |

353 |

378 |

403 |

428 |

453 |

478 |

503 |

| Conversion,XS(%) |

--- |

8.4 |

11.2 |

18.7 |

26.1 |

43.0 |

56.0 |

78.6 |

Table 2.

Hydrogenolysis of the aqueous solution of starchy waste. CS0 = 80.0 kg(m-3), 453K, 50.0 bar.

Table 2.

Hydrogenolysis of the aqueous solution of starchy waste. CS0 = 80.0 kg(m-3), 453K, 50.0 bar.

| Component CJ (CJ, kg(m-3)) |

Time (hr, t0 10.4 min) |

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| monoalcohols |

0.85 |

10.0 |

17.31 |

23.75 |

29.64 |

| ethyleneglycol |

-- |

0.53 |

1.60 |

1.75 |

2.39 |

| glycerol |

-- |

0.02 |

0.84 |

1.38 |

2.91 |

| erythritol |

-- |

0.99 |

3.51 |

4.35 |

10.53 |

| xylitol/arabitol |

-- |

4.34 |

11.48 |

12.82 |

14.10 |

| glucose/sorbitol |

76.15 |

47.9 |

36.99 |

21.34 |

17.73 |

| ∑CJ

|

77.00 |

63.78 |

71.73 |

65.39 |

77.30 |

Table 3.

Hydrogenolysis of the aqueous solution of starchy waste. CS0 = 80.0 kg(m-3), 473 K, 50.0 bar.

Table 3.

Hydrogenolysis of the aqueous solution of starchy waste. CS0 = 80.0 kg(m-3), 473 K, 50.0 bar.

| Component (CJ , kg(m-3)) |

Time (hr, t0 12 min) |

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| monoalcohols |

5.51 |

22.23 |

41.38 |

52.43 |

57.38 |

| ethyleneglycol |

-- |

1.51 |

3.53 |

5.37 |

7.10 |

| glycerol |

0.34 |

1.53 |

1.80 |

1.21 |

-- |

| erythritol |

0.91 |

5.43 |

5.27 |

3.80 |

0.27 |

| xylitol/arabitol |

1.85 |

6.33 |

3.47 |

2.37 |

0.52 |

| glucose/sorbitol |

67.58 |

39.33 |

24.37 |

8.83 |

2.93 |

| ∑CJ

|

76.19 |

76.36 |

79.82 |

74.01 |

68.20 |

Table 4.

Hydrogenolysis of the aqueous solution of starchy waste. CS0 = 80.0 kg(m-3), 493 K, 50.0 bar.

Table 4.

Hydrogenolysis of the aqueous solution of starchy waste. CS0 = 80.0 kg(m-3), 493 K, 50.0 bar.

| Component CJ (CJ , kg(m-3)) |

Time (hr, t0 13.8 min) |

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

| monoalcohols |

5.51 |

22.23 |

41.38 |

52.43 |

57.38 |

| ethyleneglycol |

-- |

1.51 |

3.53 |

5.37 |

7.10 |

| glycerol |

0.34 |

1.53 |

1.80 |

1.21 |

-- |

| erythritol |

0.91 |

5.43 |

5.27 |

3.80 |

0.27 |

| xylitol/arabitol |

1.85 |

6.33 |

3.47 |

2.37 |

0.52 |

| glucose/sorbitol |

67.58 |

39.33 |

24.37 |

8.83 |

2.93 |

| ∑CJ

|

76.19 |

76.36 |

79.82 |

74.01 |

68.20 |

Table 5.

Specific reaction rates of starch water waste hydrogenolysis. Effect of temperature. Conditions: catalyst, (Ru 1.0 %wt.-Ni 10% wt.)/activated carbon, 50.0 bar.

Table 5.

Specific reaction rates of starch water waste hydrogenolysis. Effect of temperature. Conditions: catalyst, (Ru 1.0 %wt.-Ni 10% wt.)/activated carbon, 50.0 bar.

| T(K) |

×10

|

×10

|

| 453 |

3.76 |

3.87 |

| 473 |

7.08 |

11.32 |

| 493 |

11.17 |

33.55 |

| Eat (kJ/mol) |

46.71 |

26.92 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).