1. Introduction

Geochemical prospecting for oil and gas refers to the detection of surface or near-surface hydrocarbons and their alteration products, aiding in the identification of subsurface petroleum accumulations [

1]. This approach encompasses a broad set of techniques aimed at detecting hydrocarbons migrating from reservoirs or source rocks, as well as secondary geochemical changes in soils, rocks, and microbial communities. A fundamental premise of surface geochemical exploration is that hydrocarbons present at depth can migrate and leak to the surface. These exploration techniques are generally categorized into two groups: direct and indirect methods [

2]. Direct geochemical methods focus on quantifying volatile and liquid hydrocarbons within soils or unconsolidated surface sediments. In contrast, indirect techniques investigate seepage-related alterations in soil chemistry, mineralogy, microbial populations, or vegetation.

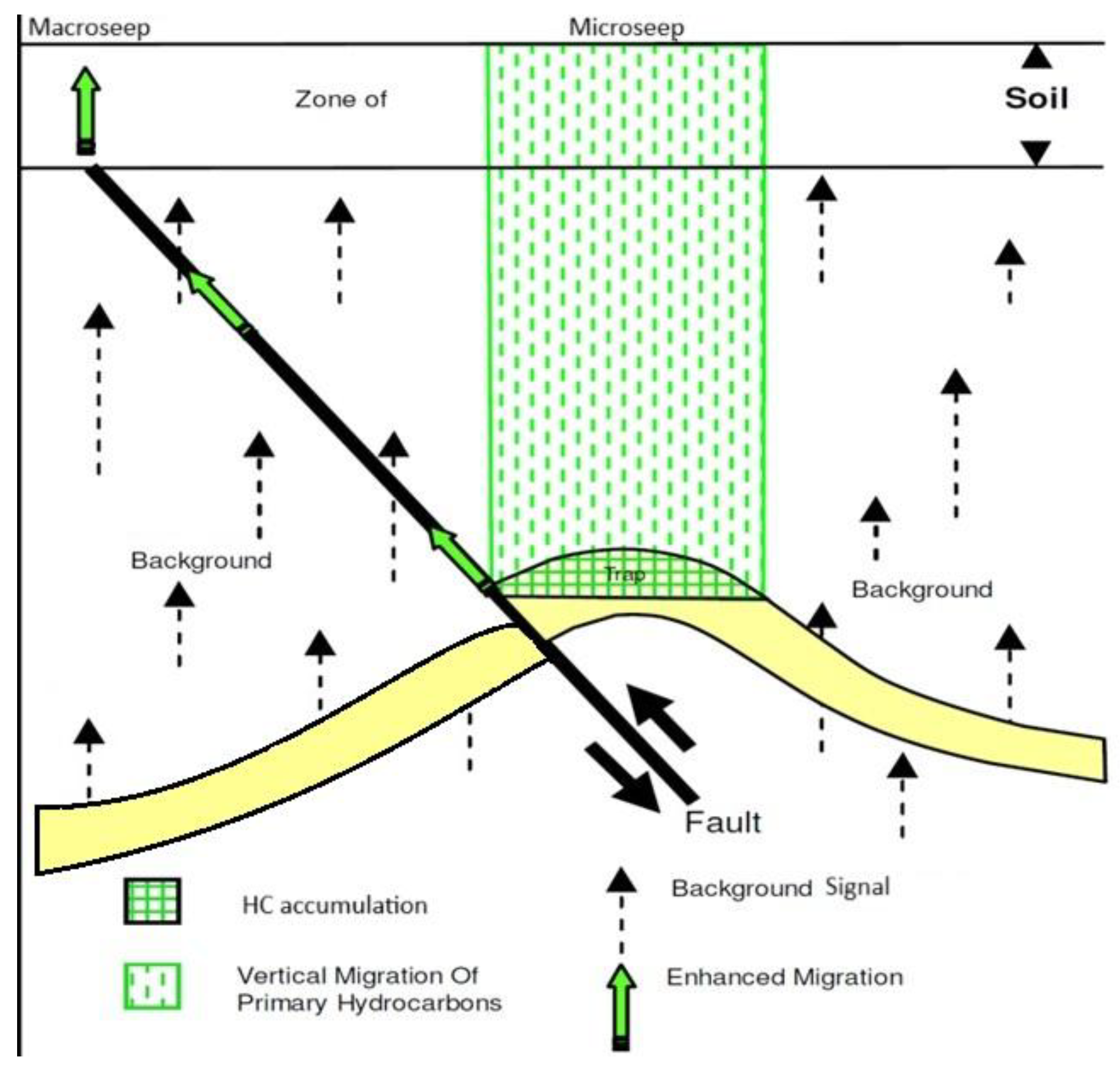

Hydrocarbon seepage manifests across a spectrum—from trace-level microseepage to conspicuous oil and gas emissions. “Macroseepage” refers to the occurrence of visible oil or gas at the surface, often associated with fault zones or fractured regions where hydrocarbons migrate readily [

3,

4]. On the other end, “microseepage” describes ultra-trace levels of volatile or semi-volatile hydrocarbons in surface media such as soils, sediments, or groundwater, detectable only through sensitive analytical instrumentation (

Figure 1) [

5].

Many current geochemical exploration approaches emphasize the collection and analysis of soil gases, integrating chemical signals from hydrocarbon microseepage with geological and geophysical (e.g., seismic) datasets [

6]. Several methods are employed to detect hydrocarbon microseepage, either by analyzing extracts from soil gas samples [

7,

8] or through the use of specially engineered materials that can adsorb and subsequently release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) accumulated from the subsurface environment [

9,

10]. A conspicuous knowledge gap exists in perfecting the best sorbents for microsepage sensing. This knowledge is proprietary and is utilized by commercial service companies; however, it has not been scientifically or systematically evaluated. Given the typically low concentrations of VOCs and their sensitivity to daily and seasonal variations, extended adsorption periods can improve detection reliability. In this study, we focused on evaluating the adsorption performance of a diverse library of commercial and custom-made materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

A wide range of adsorbents was examined for their ability to capture volatile organic compounds associated with underlying hydrocarbon systems. These included activated carbons (AC), porous polymers, composite sorbents combining both, and various types of zeolites.

Commercial activated carbons—SKT, VSK, MeKS, DAS, and FAS—were obtained from JSC “Elektrostal Scientific and Production Association Neorganika” (Elektrostal, RF). Additional carbon materials such as UPK-B, UNHT, AUkon-s, and a porous polymer sorbent based on cross-linked polystyrene with a crosslinking degree of 150% were synthesized at the Institute of Physical Chemistry, Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow, RF) and the Institute of Chemical Technologies IC SB RAS (Omsk, RF). Single-walled carbon nanotubes (TUBALL™) were supplied by OCSiAl LLC (Novosibirsk, RF). A composite sorbent combining activated carbon and porous polymer (Tenax GR™) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, as were the zeolites/molecular sieves 13X. NaX-type zeolites were obtained from Sorbis Group LLC (Moscow, RF). Crude oil samples from the Romashkinskoye field were provided by the A.V. Topchiev Institute of Petrochemical Synthesis, RAS, Russia.

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with purity ≥ 98% used in this study included a homologous series of alkanes (from pentane to docosane), aromatic hydrocarbons (toluene, xylenes, ethylbenzene, propylbenzenes, butylbenzene, hexylbenzene, and octylbenzene), and cycloalkanes (cyclopentane, methylcyclopentane, methylcyclohexane). All VOCs were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2. Method of determination of the porous structure of sorbent samples

The parameters of the porous structure of the adsorbents were analyzed using data from low-temperature nitrogen adsorption at 77 K (automatic analyzer ASAP 2020) and equilibrium adsorption of benzene vapor at 293 K (high-vacuum sorption unit with a spring quartz microbalance with a sensitivity of about 20 μg at a load of up to 0.2 g). Before measurements, the samples were preliminarily evacuated to constant weight at a residual pressure of 10⁻⁵ Pa and a temperature of 280 °C. The parameters of the microporous structure (micropore volume and size) were determined using the theory of volumetric filling of micropores according to the Dubinin–Radushkevich equation. The specific surface area was calculated in accordance with the BET equation (nitrogen). The parameters of the porous structure of the adsorbents are given in

Table 1.

2.3. Model mixture of hydrocarbons for evaluation of adsorption capacity of sorbents

To determine and evaluate the adsorption capacity of sorbents for hydrocarbons, a model mixture of volatile organic molecules was used for sorbent exposure and accumulation of VOC vapors. A mixture of standards was prepared using a Sartorius Biohit pipette (Germany) for 10–100 µL and a Huawei pipette (China) for 1–10 μL.

The composition of the model mixtures includes the following VOC volumes:

Standard Mixture №1: methylcyclopentane (10 µL), methylcyclohexane (10 µL), isooctane (15 µL), octane (15 µL), nonane (15 µL), decane (15 µL), benzene (15 µL), toluene (15 µL), ethylbenzene (15 µL), propylbenzene (15 µL), butylbenzene (15 µL), o-xylene (15 µL).

Standard Mixture №2: methylcyclopentane (10 µL), methylcyclohexane (10 µL), heptane (1 µL), isooctane (2 µL), octane (3 µL), nonane (6 µL), decane (8 µL), undecane (10 µL), dodecane (12 µL), tridecane (12 µL), tetradecane (14 µL), pentadecane (14 µL), hexadecane (14 µL), heptadecane (8 mg), octadecane (8 mg), nonadecane (8 mg), eicosane (8 mg), heneicosane (8 mg), docosane (8 mg), benzene (2 µL), toluene (4 µL), ethylbenzene (4 µL), propylbenzene (4 µL), butylbenzene (8 µL), hexylbenzene (10 µL), o-xylene (4 µL), p-xylene (4 µL).

To identify the most effective sorbents for the sorption and desorption of the model mixture, equal volumes (2 mL) of the sorbents described in the Materials section 2.1. were used. For comparison, Standard Mixture №1—containing compounds with boiling points below 200 °C—was selected. Sampling of the headspace vapors was performed at room temperature (20 °C) using a 1 μL gas-tight syringe.

A high sorbent-to-standard ratio was chosen to help isolate the most promising sorbents. Sorption was carried out over 5 days. Following this, sorbents were preheated for 40 minutes at 270 °C. Then, 60 μL of vapors above the sorbents was collected using a gas-tight syringe and injected into the GC-MS system.

2.4. Method of saturation of sorbents by hydrocarbon VOCs

Standards and sorbents were weighed on a Sartorius MC1 Analytic AC 210 S analytical balance (Germany). Sorbents with vapor mixtures of standards were kept in a dry-air thermostat. The studied sorbent, with a volume of 1 mL, was placed in a glass bottle with a volume of 28.26 cm³. An aliquot of the standard mixture was taken with a 10 μL dispenser and placed in a 2 mL glass vial. The open vial was then placed in the bottle containing the sorbent. The bottle was sealed with a lid and further isolated from the external environment using parafilm tape. The sealed bottle, containing both the standards and the sorbent, was placed in a thermostat and left for sorption for three days at a temperature of 22 °C, as shown in

Figure 2. At the end of the sorption period, the vial containing the mixture of standards was removed from the bottle. The sorbent was weighed to verify consistency in sample volume. Desorption was then performed by placing the sealed vial containing the sorbent on a hotplate preheated to 300 °C. The vial remained sealed to ensure uniform heating. Desorption was carried out over 1.5 hours. Before sampling, the gas-tight syringe was preheated on a hotplate to avoid condensation of the standard compounds. A 100 µL gas sample from the headspace above the sorbent was withdrawn using the preheated syringe through the septum of the heated vial. The sample was immediately injected into the injector for analysis.

2.5. Method for GCMS separation and detection of hydrocarbon VOCs adsorbed on sorbents

Vapor analysis was carried out using a gas chromatograph coupled with a Shimadzu TQ-8040 mass spectrometer (Japan) equipped with electron ionization and a quadrupole mass analyzer. An Agilent HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.32 mm, 0.25 μm; USA) was used for separation. Sampling was performed with a 100 µL gas-tight syringe (Hamilton, USA), and the sorbent was heated on a PL-H heating plate (Primelab, Russia). For the separation of volatile compounds, the column temperature was held at 30 °C for 5 minutes. To separate high-boiling oil components, the temperature was increased to 280 °C and held for 4 minutes. The split ratio was set at 30:1 (sample drop: flow to column). Mass spectrometric detection conditions were as follows: ionization energy 70 eV, ion source temperature 200 °C, interface temperature 250 °C, and injection volume 1 µL. Mass spectra were recorded in scanning mode over a range of 33 to 500 m/z. For analyses involving low-boiling solvents, detection was carried out starting from 2.4 minutes.

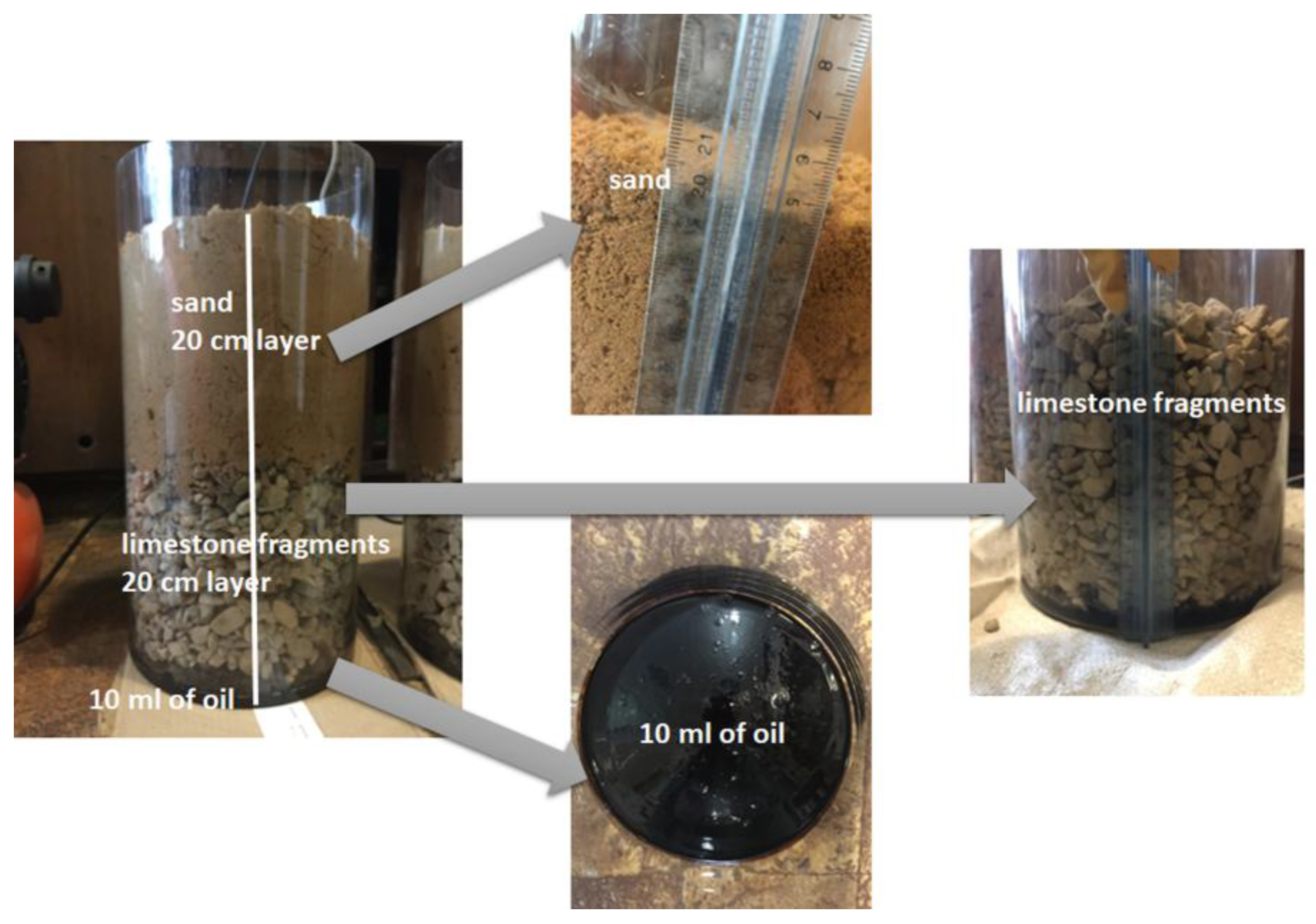

2.6. Passive sampling of crude oil VOCs

All sorption experiments were conducted using crude oil from the Romashkino field. A total of 10 mL of oil was placed at the bottom of a glass container (20 cm in diameter and 50 cm in height). The container was then filled with a 20 cm layer of limestone fragments (5–20 mm fraction) followed by a 20 cm layer of sand. Sorbent samples were enclosed in a Gore-Tex membrane made from thermo-mechanically expanded PTFE (ePTFE) and buried approximately 5 cm deep within the sand layer. The sorbents remained in the container for two weeks. The setup is shown in

Figure 3. Passive sampling of VOCs from natural oil vapors was performed by placing a sensor containing activated carbon STK, carbon nanotubes CNTs, sorbents AUkon-s and Tenax GR on the laboratory microseepage setup loaded with 10 ml of oil and saturating the sorbent with the VOCs for 1-2 weeks. Consecutive GCxGC/MS analysis of the complex mixture of adsorbate allows separation, detection and identification of the mixture composition.

2.7. Thermal desorption and GCxGC/MS analysis of crude oil VOCs

Thermal desorption and two-dimensional gas chromatography–mass spectrometry experiments were performed using a LECO Pegasus BT 4D system equipped with an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph featuring a secondary oven, a flow splitter, a two-stage cryomodulator, and a Gerstel Thermal Desorption Unit (TDU). The instrument operated in electron ionization mode (70 eV); the ion source temperature was 200 °C, mass range 45–500 Da, acquisition rate 100 spectra/s, and ion extraction rate 30 kHz. The column configuration included a polar Rxi-17Sil (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) and a non-polar Rxi-5Sil (2 m × 0.10 mm × 0.10 μm). The column oven program was as follows: initial temperature of 50 °C held for 4 minutes, ramped to 280 °C at 5 °C/min, and held at the final temperature for 5 minutes. The temperatures of the secondary oven and the cryomodulator were maintained 20 °C higher than the primary oven temperature. The modulation time was set at 6 s. TDU temperature was set to 300 °C with a desorption time of 120 s. The sample weight was 20 mg. The cooled injection system was maintained at –150 °C, and the transfer line was heated to match the TDU temperature. Compound identification was carried out using the NIST 20 mass spectral database.

3. Results and Discussion

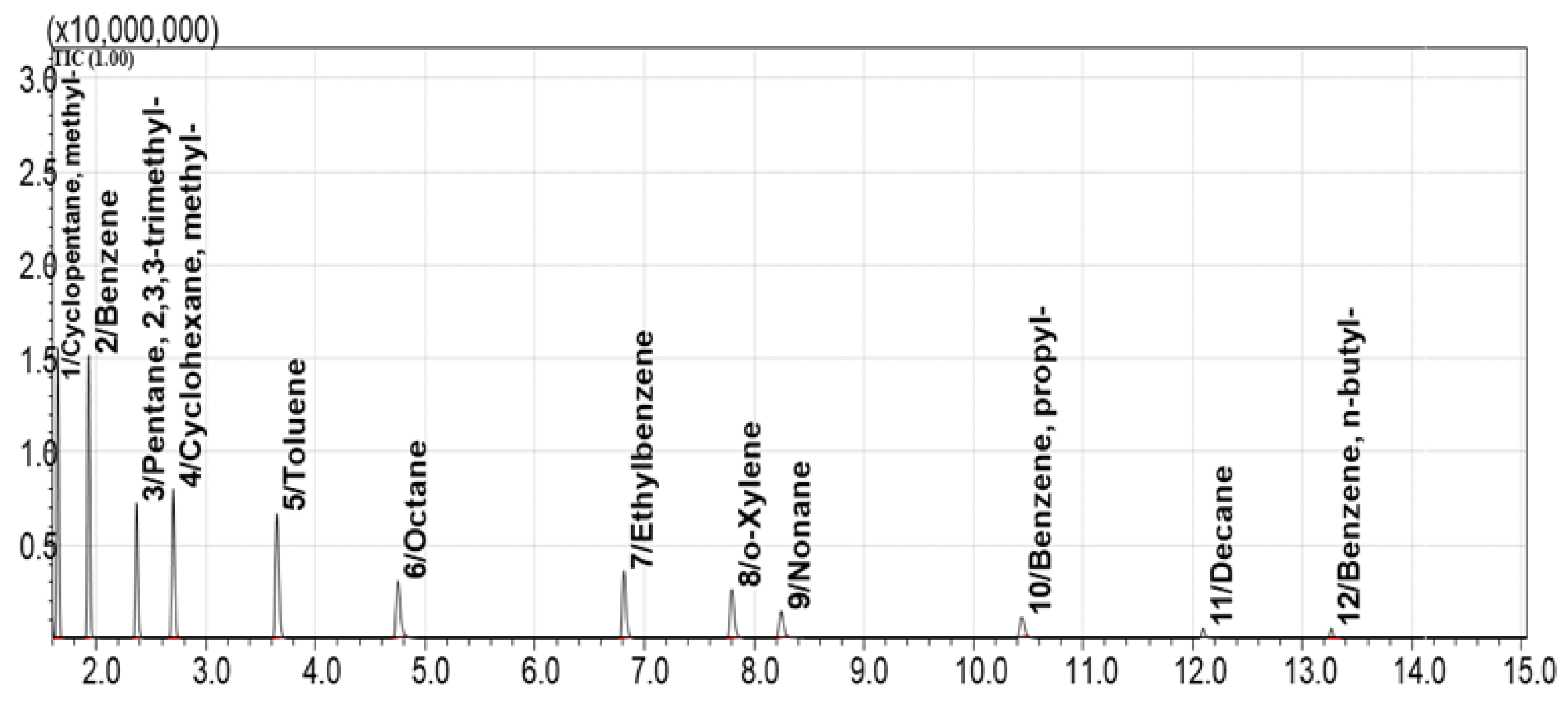

3.1. Selection of the best adsorbents from the library of porous materials

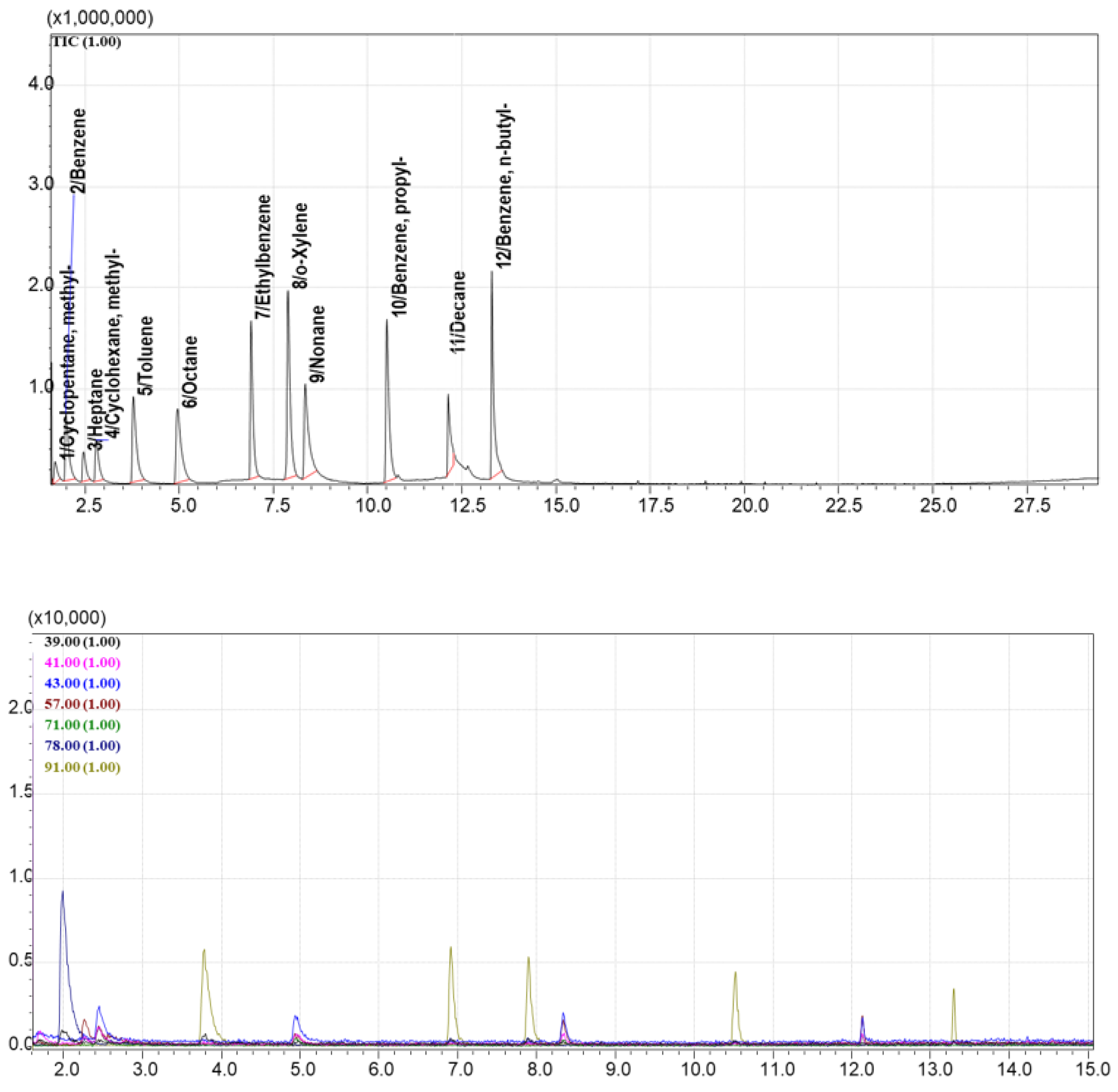

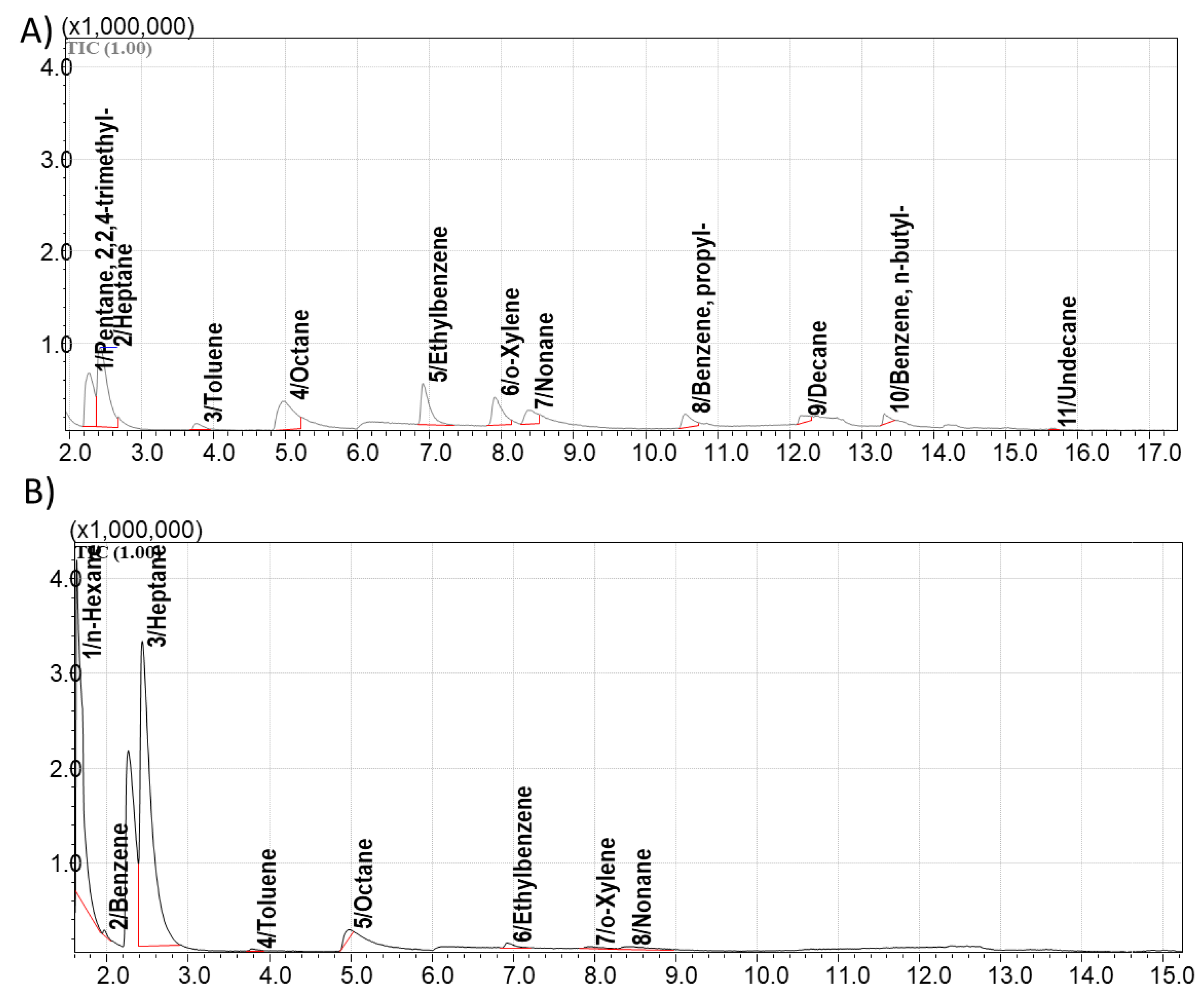

To identify the most effective sorbents for the sorption and desorption of the model mixture, equal volumes of the sorbents were used. For comparison, Standard Mixture №1 was selected. The TIC chromatographic profile of vapors above the Standard Mixture №1 is shown in

Figure 4.

This chromatogram (

Figure 4) was compared with the TIC and extracted ion chromatograms (EIC) of vapors collected after sorption on each sorbent from the tested library. EICs were generated for the following characteristic ions: 39, 41, 43, 57, 71, 78, and 91 m/z. These ions correspond to alkanes, cycloalkanes, and aromatic compounds present in Standard Mixture №1.

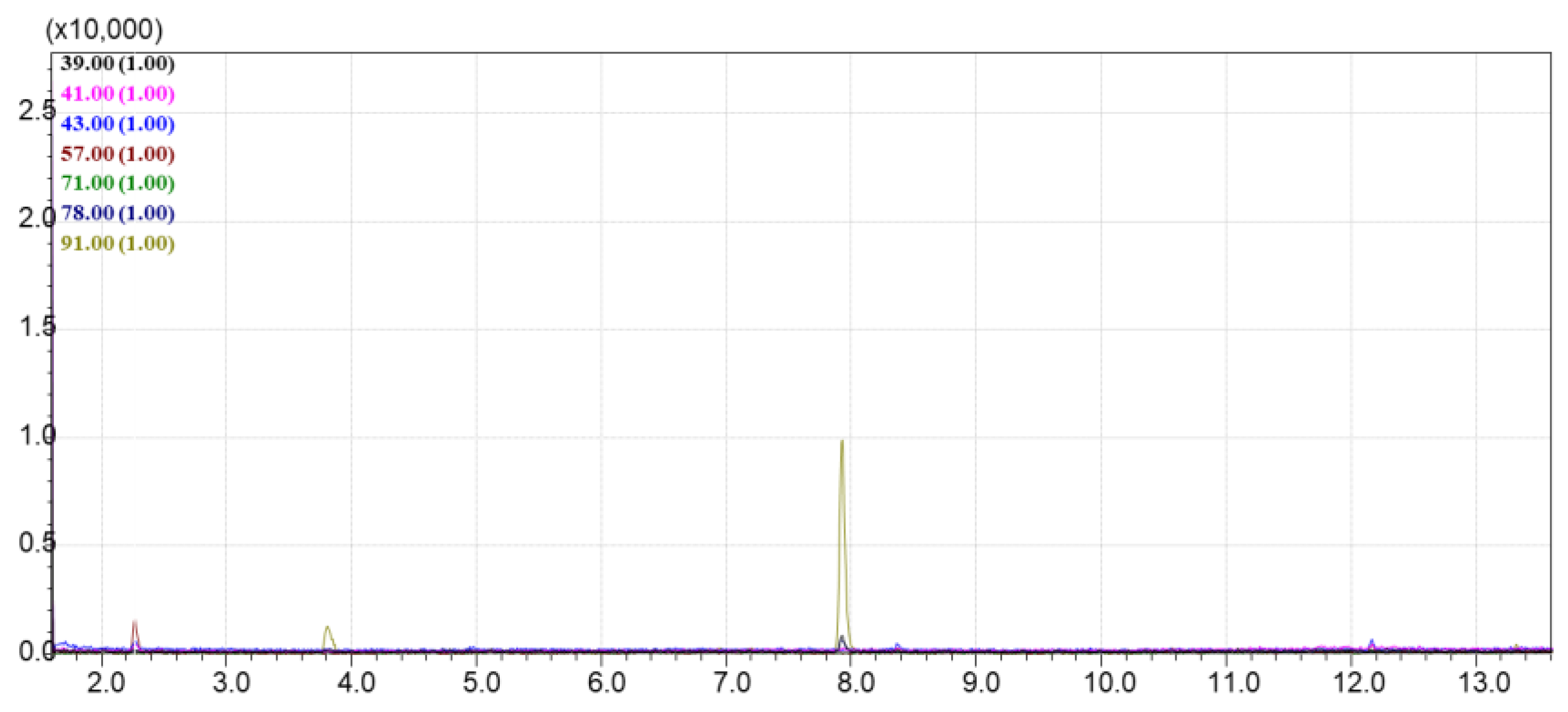

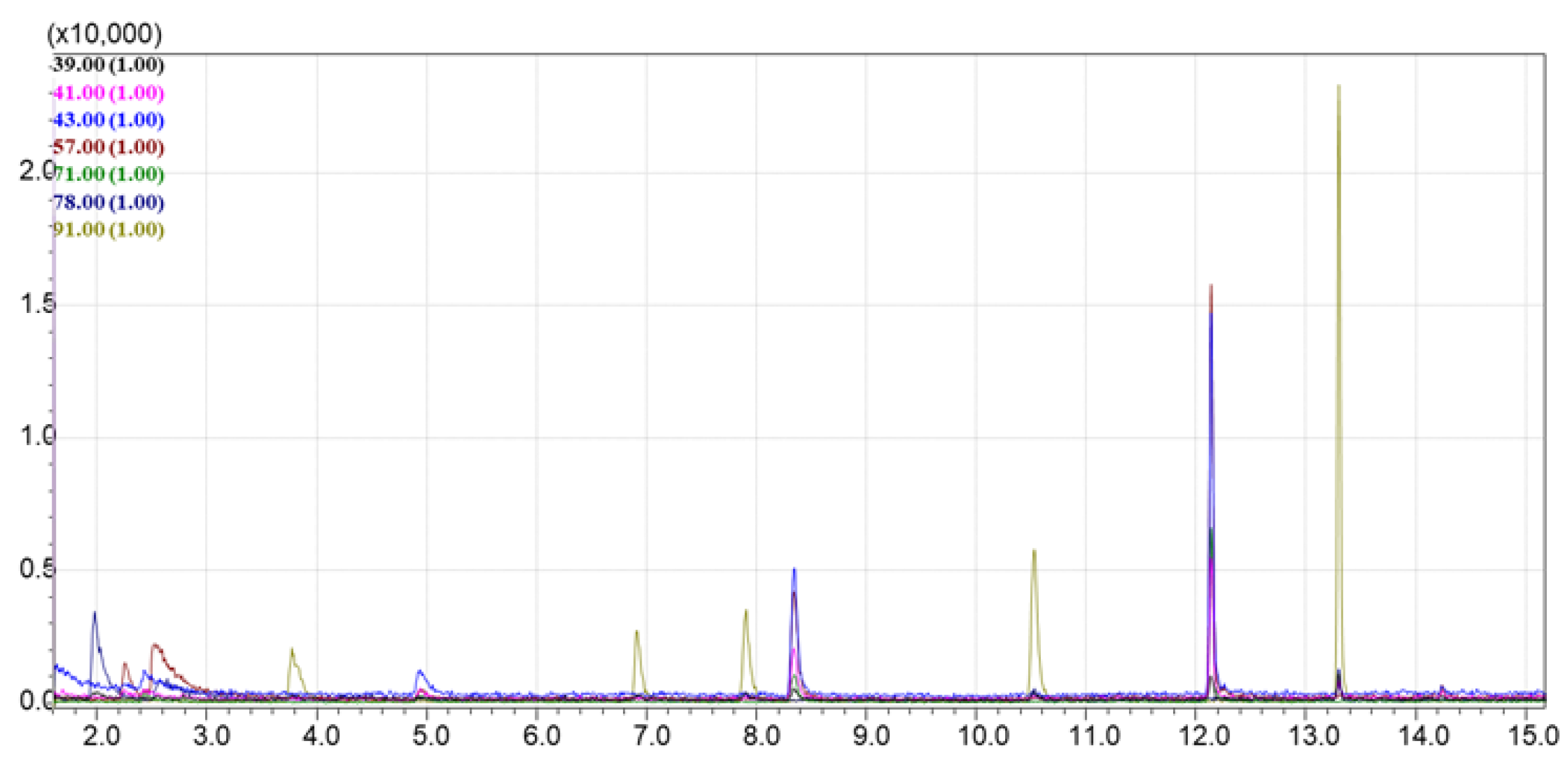

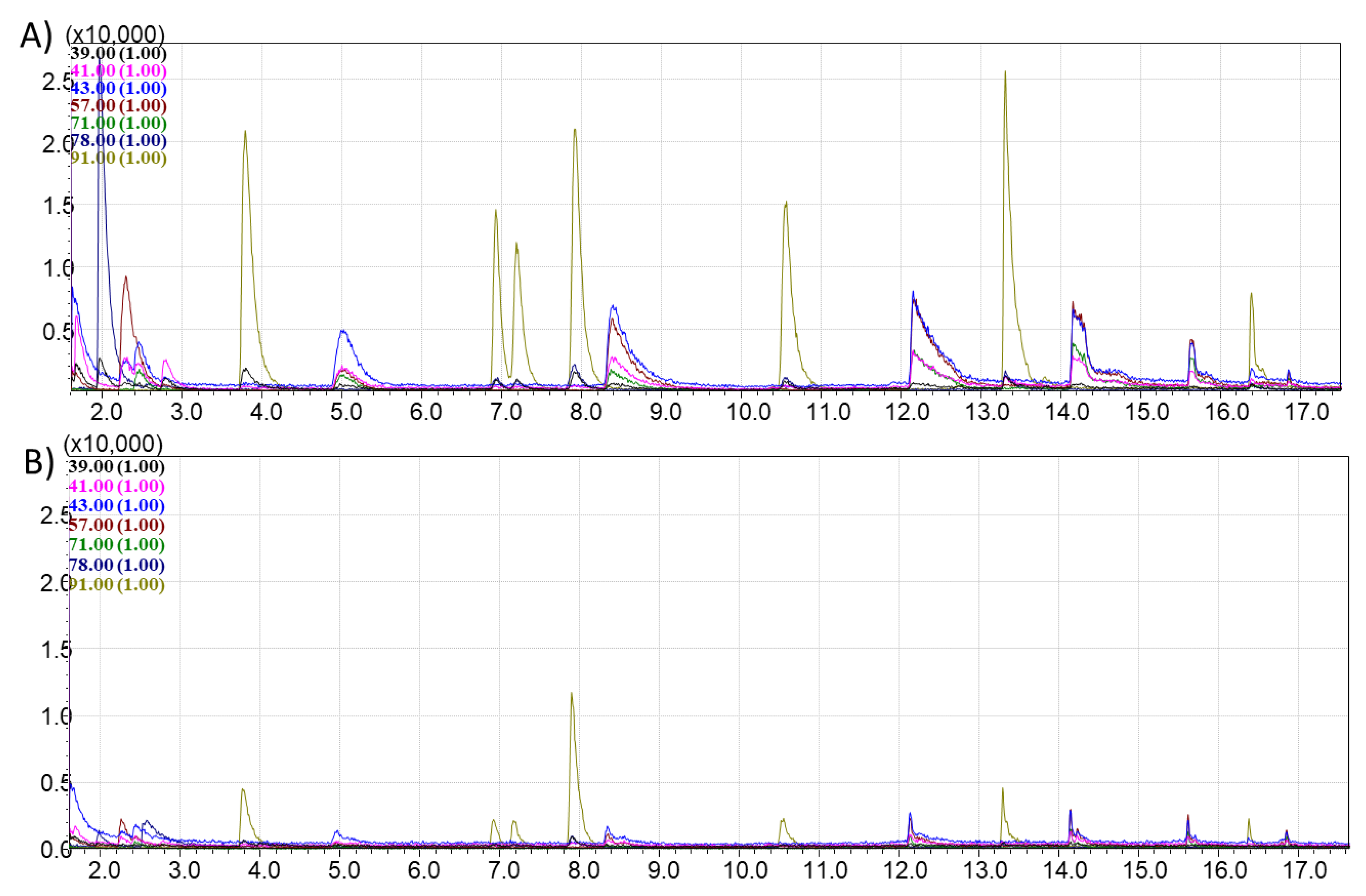

Sorbent selection was based on two key criteria: the number of resolved peaks and the intensity of those peaks. Highly cross-linked polystyrene (

Figure 5) showed selective sorption of aromatic compounds (notably ions 91 and 78 m/z); however, more universal sorbents (UNHT, AUkon-s, UPK-B, DAS) exhibited comparable or greater adsorption of aromatics, and thus polystyrene was excluded from further experiments. Zeolite 13X also showed limited sorption of aromatics, with both the number and intensity of detected compounds being low, so it was not used in subsequent tests. The chromatograms for AUkon-s and DAS (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) showed clear signals from aromatics and n-alkanes. Cycloalkanes were also detected in the chromatograms of UPK-B and UNHT (

Figure 8 and

Figure 9). Based on the preliminary screening, the sorbents selected for further investigation were: UNHT, UPK-B, DAS, and AUkon-s.

The lowest signal intensity in the TIC chromatogram was observed for the DAS sorbent; no significant volatile compounds were detected in the TIC mode, and only the EIC showed low peak intensities, mainly for benzene derivatives and decane (

Figure 7). The UPK-B sorbent also showed low intensity in the TIC chromatogram, with a bias toward heavier molecular weight compounds (

Figure 9).

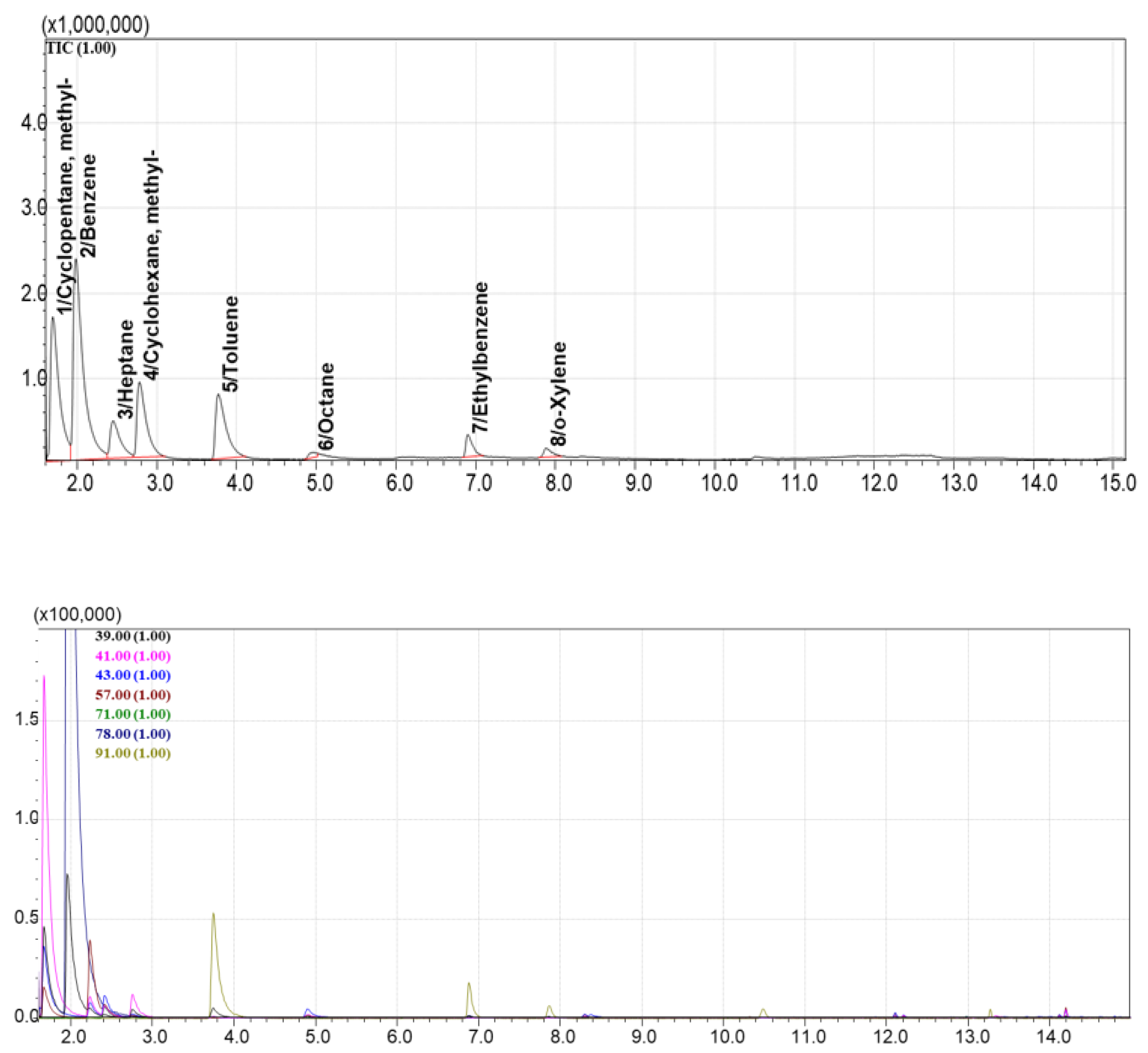

Among all tested materials, AUkon-s demonstrated the best performance, showing all 12 volatile compounds from Standard Mixture №1 in the TIC chromatogram (

Figure 6). It exhibited balanced selectivity for both light and heavy components. The UNHT sorbent showed 8 out of 12 compounds from the standard mixture in TIC mode (

Figure 8). Thus, the most promising sorbents selected from the screening were AUkon-s and UNHT, which were used in subsequent experiments.

Based on nitrogen adsorption data, AUkon-s is a microporous activated carbon with negligible mesoporosity and a high specific BET surface area of 940 m²/g. The UNHT adsorbent, in contrast, features a well-developed mesoporous structure with an average mesopore diameter of 31 nm (according to the BJH method) and moderate microporosity (

Table 1).

3.2. Evaluation of the adsorption and desorption parameters for the best selected sorbents

Varying the VOC adsorption duration for the AUkon-s and UNHT materials—using 1 day and multiple-day exposures to Standard Mixture №1—revealed that after 1 day, only a small number of compounds were detected in the chromatogram for extracted ions for the UNHT sorbent. In the chromatogram obtained for the AUkon-s sorbent, the peaks corresponding to the standard compounds were practically absent. When the sorbents were kept for 3 days and over, the chromatograms for both sorbents showed peaks corresponding to compounds from the standard mixture (

Figure 10).

To evaluate desorption kinetics, VOC-saturated sorbents exposed to Standard Mixture №1 were heated at 300 °C. Vapor samples were taken periodically and analyzed by GC-MS. The first sample was taken after one hour of heating, with additional samples collected every 30 minutes. Complete desorption was observed within 1.5 hours. The optimum vapor sample volume was found to be 100 μL. The minimum detectable mass of compounds ranged from 1 to 7µg, depending on their boiling point and ionization efficiency.

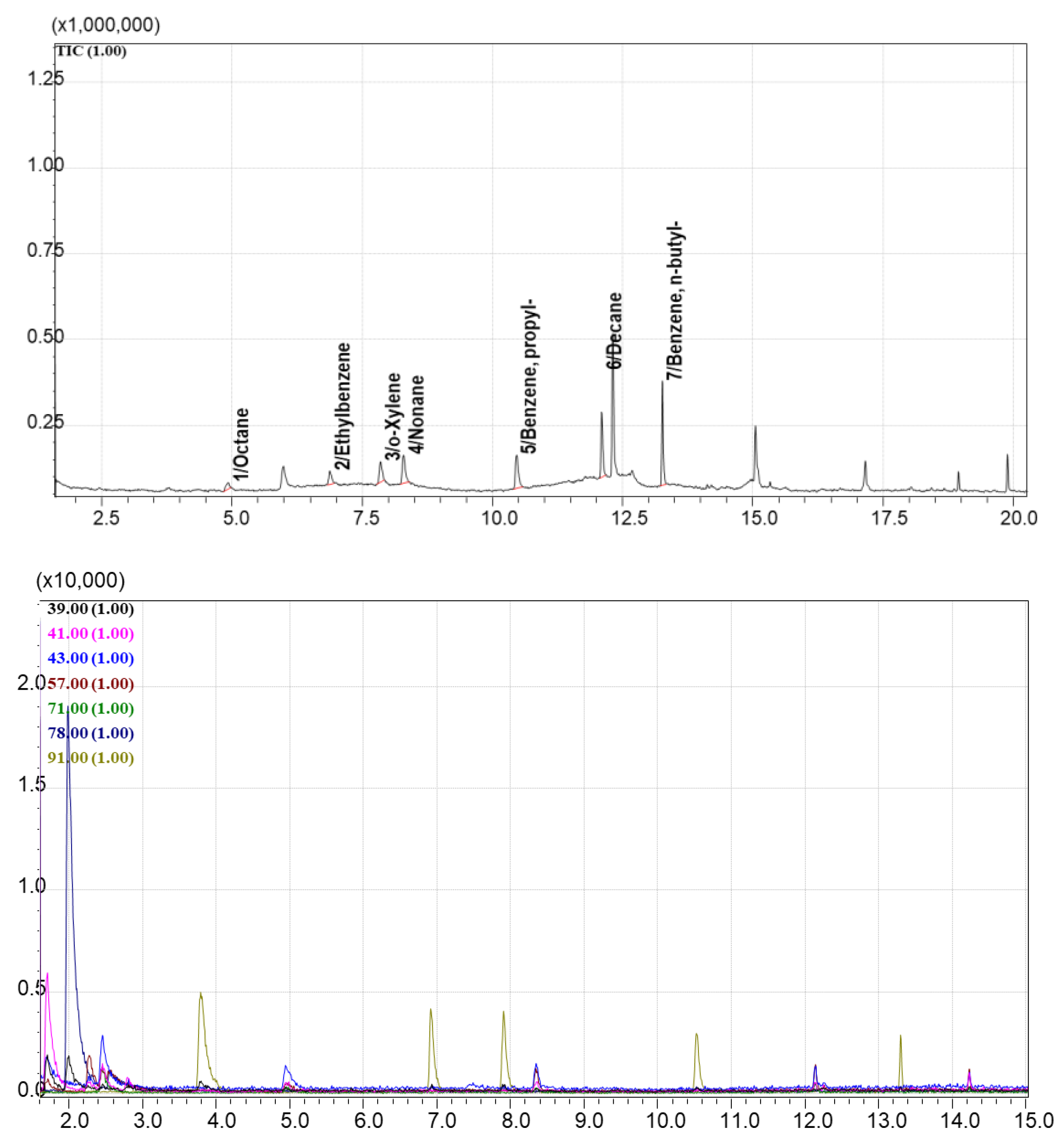

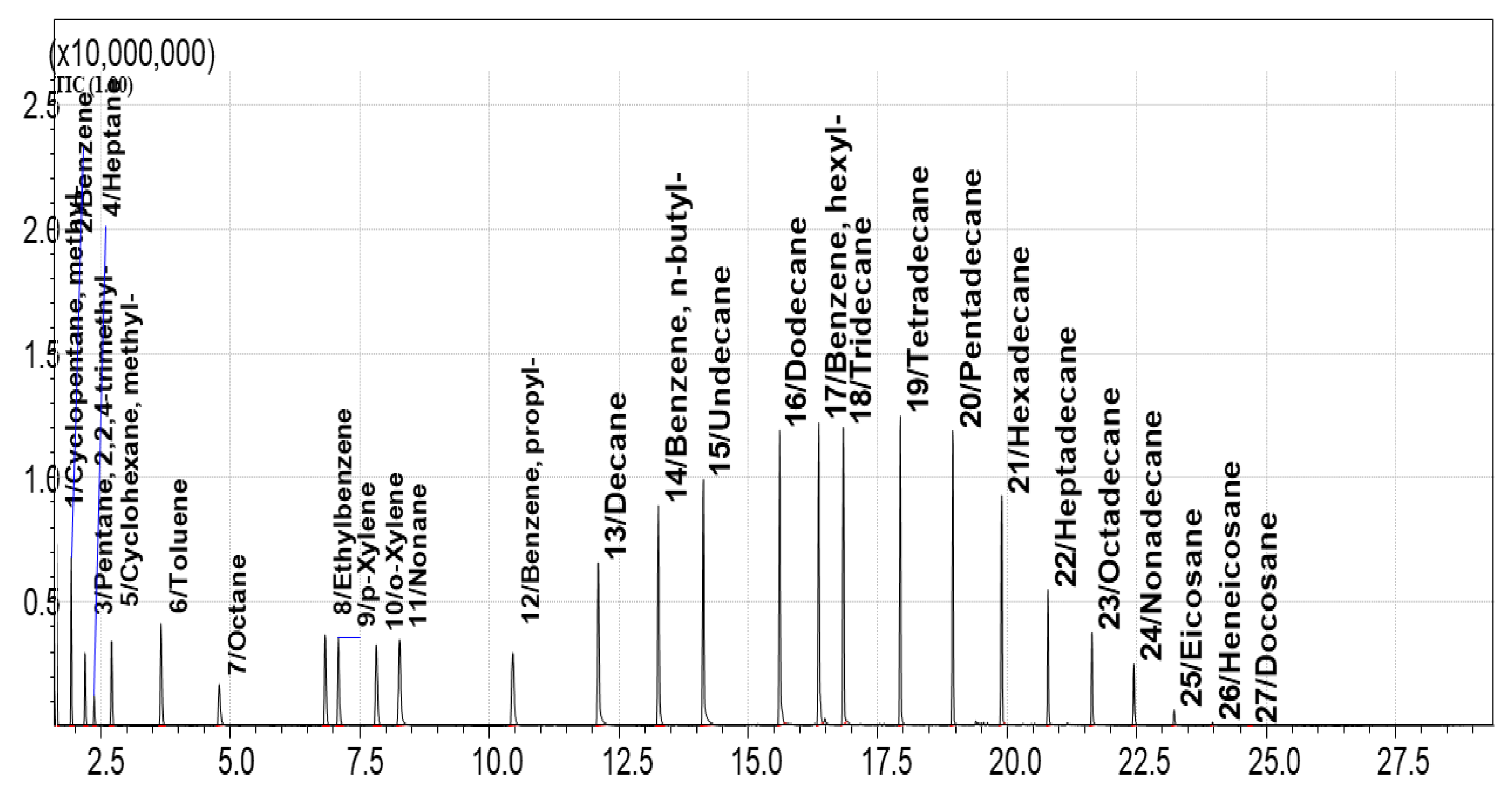

To evaluate adsorption capacity over a broader analyte range, a more complex VOC mixture (Standard Mixture №2, containing 27 compounds) was used. TIC chromatogram of vapors over this mixture are shown in

Figure 11.

Chromatograms of vapors over the sorbents after exposure to this mixture are compared with

Figure 11. The EIC chromatogram for AUkon-s showed 16 of the 27 standard compounds. For UNHT, the same compounds were detected, but with peak intensities approximately an order of magnitude lower (

Figure 12). The maximum sorbent-to-standard mixture ratio at which qualitative detection was still possible was 1 mL of sorbent per 2 μL of the 27-compound mixture. The minimum detectable mass of compounds adsorbed on AUkon-s under the applied sorption/desorption conditions was approximately 1 μg. For n-alkanes (C₇H₁₆ to C₁₂H₂₄), this value ranged from 1 to 7 μg; for aromatic compounds, from 2 to 6 μg. The optimal detection ratio was 1:2 (1 mL of sorbent per 2 μg of analyte).

Based on this extended screening, AUkon-s was identified as the most effective sorbent and selected for further studies on passive sampling of volatile compounds from crude oil. Additionally, the established VOC sorption and GC-MS analysis protocol was applied to evaluate the performance of the commercial sorbent Tenax GR, which is widely used for VOC monitoring in environmental studies [

11,

12]. Tenax GR showed good sorption efficiency, confirmed by GC-MS analysis of thermally desorbed vapors after exposure to Standard Mixture №2. The TIC chromatogram revealed detection of 18 out of 27 analytes in the mixture (

Figure 13).

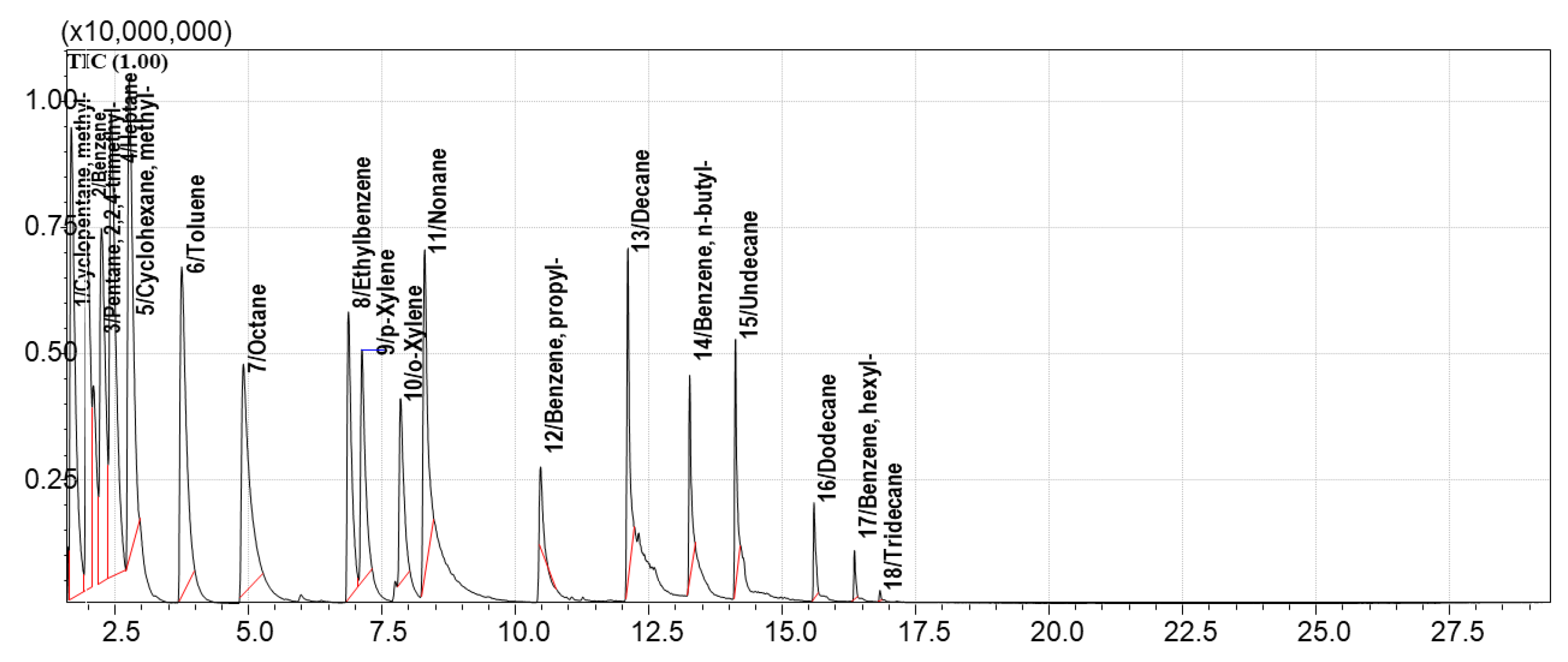

3.3. The passive sampling of VOCs from natural oils in laboratory conditions

The principle of passive sampling relies on the diffusion-driven transport of VOC molecules from air onto the sorbent, where they are retained due to higher affinity. This enables the accumulation of analytes over time, which is particularly valuable when time-averaged concentrations are low [

10].

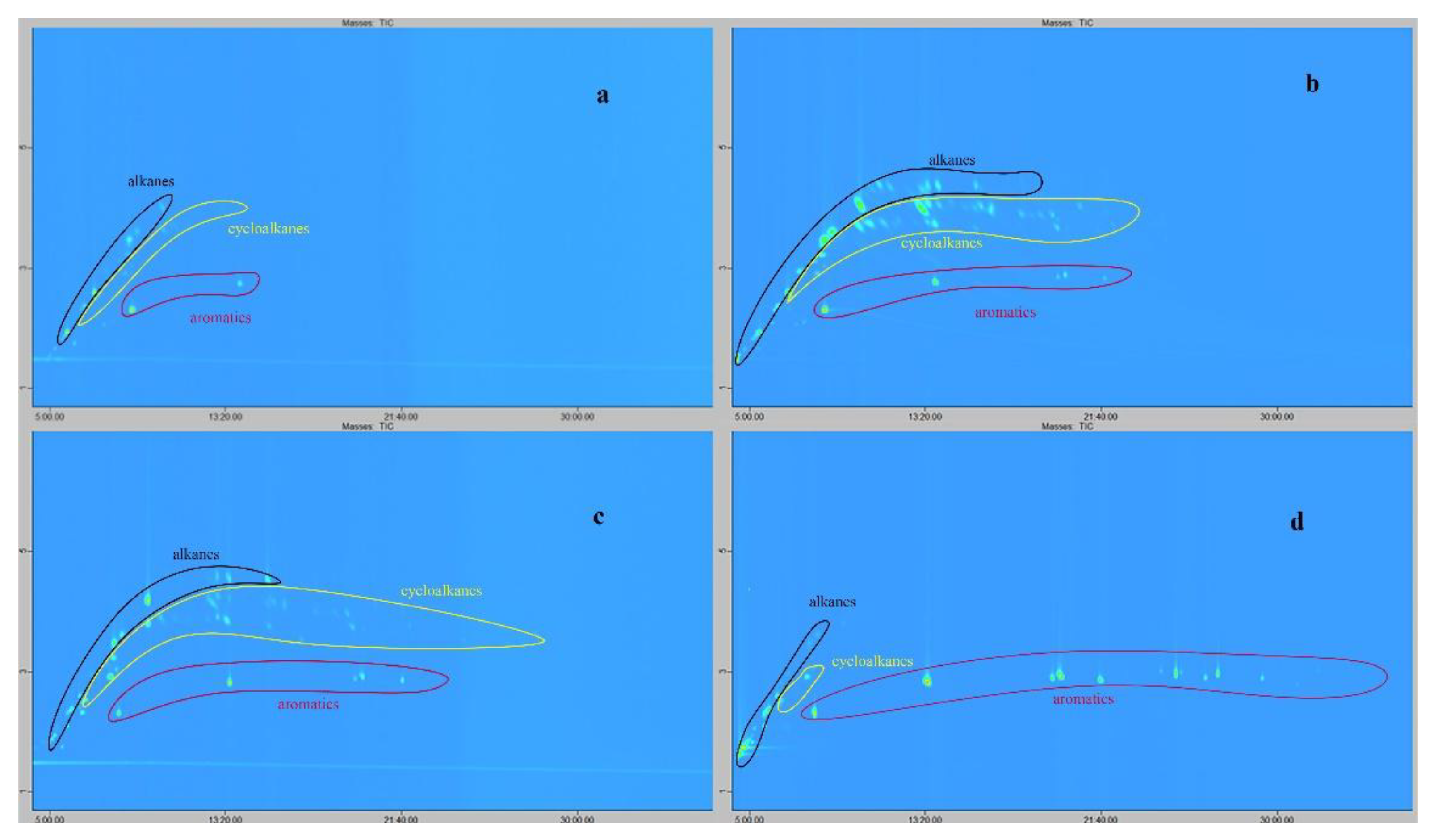

Passive sampling of VOCs from natural oil vapors and consecutive GCxGC/MS analysis of the complex mixture of adsorbate allows separation, detection and identification of the mixture composition. Three customized sorbents including activated carbon STK, carbon nanotubes CNTs, and AUkon-s were exposed to oil VOCs’ and compared with commercial benchmark Tenax GR. Results of the sensing experiments in a simulated microseepage setup showed that all selected sorbents successfully accumulated a wide range of hydrocarbons, including alkanes, cycloalkanes and aromatic compounds (Table S1,

Figure 14). A comparison of the number of identified compounds, as shown in

Figure 14 and Table S1, revealed that activated carbon STK exhibited the lowest performance. Experiments involving repeated thermal desorption indicated that the selected desorption temperature did not ensure complete analyte release, as residual compounds were still detected. Since higher desorption temperatures risk degrading thermally labile analytes, the use of this sorbent was considered less favorable. The total number of analytes identified from the tested sorbents increased in the following order: activated carbon STK – 24 compounds, commercial Tenax GR – 48 compounds, AUkon-s – 71 compounds, and TUBALL CNTs – 90 compounds.

The results for Tenax GR demonstrated its superior performance in adsorbing aromatic hydrocarbons. Although CNTs and AUkon-s enabled the detection of a greater total number of organic compounds, Tenax GR exhibited a more diverse profile of aromatic analytes. The hydrocarbon adsorption profiles for CNTs and AUkon-s were similar; however, CNTs enabled the identification of a slightly higher number of compounds.

3.4. Field Validation and Future Directions for Sorbent-Based Microseepage Detection

Given the compositional complexity of crude oil—including saturates, aromatics, resins, and asphaltenes—designing sorbents capable of capturing this full molecular range remains a critical challenge [

13,

14]. Our laboratory screening revealed that AUkon-s and TUBALL CNTs offer broad-spectrum adsorption capacity, outperforming both commercial and custom benchmarks. The next phase of research will involve field deployment of these sorbents in areas with confirmed hydrocarbon accumulations to evaluate their selectivity, durability, and efficiency under natural conditions. Such studies will build on earlier field investigations that explored the effect of sampling depth on microseepage detection fidelity [

10]. However, the present focus will shift toward understanding how sorbent type and surface properties influence VOC recovery in heterogeneous surface environments, which will be essential for refining both material design and operational protocols.

In parallel, integrating sorbent-based VOC detection with elemental geochemical approaches could significantly improve signal interpretation and anomaly resolution. Prior work has shown that linking biomarkers with trace element patterns can reveal the depositional and diagenetic controls on organic matter and hydrocarbon migration [

15]. Moreover, incorporating techniques like mobile metal ion (MMI) analysis—which has demonstrated success in mapping near-surface geochemical halos associated with subsurface mineralization—can offer a complementary perspective when adapted for petroleum systems [

16]. Combining molecular-level hydrocarbon detection with elemental anomalies may enhance our ability to distinguish true seepage from background noise, reduce false positives, and ultimately improve targeting accuracy in exploration campaigns.

Beyond the technical implications, these advancements offer meaningful contributions toward reducing the environmental impact of exploration. Improving the resolution and confidence of geochemical prospecting reduces reliance on high-risk drilling and can lower the number of dry wells—thereby cutting emissions, operational costs, and surface disturbance. In this context, the use of high-performance sorbents in passive VOC sensing represents a scalable, low-footprint alternative to conventional methods. Coupled with advanced GCxGC/MS analysis, this approach supports a more data-driven, efficient, and carbon-conscious exploration paradigm—one that aligns with the growing need to balance resource development with environmental responsibility.

4. Conclusions

A comprehensive evaluation of a library of custom-made and commercial sorbents was conducted to identify the most effective porous materials for the passive accumulation of oil field vapors under laboratory conditions. The microporous carbon-based materials AUkon-s and TUBALL CNTs demonstrated the highest performance in simulated microseepage environments. These leading sorbents exhibited high hydrocarbon adsorption capacity and well-developed specific surface areas with both micro- and mesoporosity. Sorbents with higher specific surface areas accumulated a greater number of analytes spanning aliphatic, alicyclic, and aromatic hydrocarbon classes. Based on these findings, AUkon-s and CNT-based sorbents were selected as the most promising materials for future field deployment in oil and gas exploration settings.

5. Patents

The materials presented in this work and their proposed applications are covered by IP WO2024237802A1 [

17].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S., M.O., and I.A.; methodology, G.P., R.B.; software, R.B.; validation, A.K., I.P. and R.B.; formal analysis, M.A.; investigation, I.P., R.B.; resources, V.S., M.O., I.A.; data curation, I.A., V.S., R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, G.P., R.B., V.S.; writing—review and editing, V.S., I.A.; visualization, R.B., G.P.; supervision, I.A., V.S., R.B., M.O.; project administration, I.A.; funding acquisition, V.S., M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Exclude, this study did not report any data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr. Aleksey Konstantinovich Buryak, Director of Frumkin Institute of Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry RAS, for insightful comments for the project implementation and valuable assistance with project discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”

References

- Schumacher, D. (Ed.) Hydrocarbon Migration and Its Near-Surface Expression: Overgrowth of the AAPG Hedberg Research Conference, Vancouver, British Columbia, April 24 - 28, 1994. American Association of Petroleum Geologists [u.a.]; 1996.

- Chapter 10. Geochemical Methods of Exploration for Pe- Troleum and Natural Gas. In Developments in Petroleum Science; Elsevier, 1975; Vol 1, pp. 307–341. [CrossRef]

- Abrams, M.A. Microseepage vs. Macroseeepage: Defining Seepage Type and Migration Mechanisms for Differing Levels of Seepage and Surface Expressions. In 2019 AAPG Hedberg Conference: Hydrocarbon Microseepage: Recent Advances, New Application, and Remaining Challenges. American Association of Petroleum Geologists; 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, S.; De Souza Filho, C.R. Spectral remote sensing for onshore seepage characterization: A critical overview. Earth-Sci Rev. 2017, 168, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedesco, S.A. Concepts of Microseepage. In Surface Geochemistry in Petroleum Exploration; Springer US, 1995; pp. 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, D. Integrating Hydrocarbon Microseepage Data with seismic Data Doubles Exploration Success. In Proc. Indon Petrol. Assoc., 34th Ann. Conv. Indonesian Petroleum Association (IPA); 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvitz, L. ON GEOCHEMICAL PROSPECTING—I. GEOPHYSICS 1939, 4, 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conolly, J.R.; Moffitt, R.S.; Adams, N.P. Soil-gas microseepage surveys help locate new oil and gas accumulations. In Petroleum Exploration Society of Australia (PESA); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schrynemeeckers, R. Combining Surface Geochemical Surveys and Downhole Geochemical Logging for Mapping Hydrocarbons in the Utica Shale. In Proceedings of the AAPG Annual Convention and Exhibition; AAPG Publisher, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Atwah, I.; AlSaif, M.; Yeadon, A.; Srinivasan, P. Depth dimension in seepage detection: Insights for exploration and geological gas storage surveillance. Geoenergy Sci Eng. 2024, 243, 213242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolnai, B.; Gelencsér, A.; Gál, C.; Hlavay, J. Evaluation of the reliability of diffusive sampling in environmental monitoring. Anal Chim Acta 2000, 408, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelencsér A, Kiss Gy, Hlavay J, Hafkenscheid ThL, Peters RJB, De Leer EWB. The evaluation of a tenax GR diffusive sampler for the determination of benzene and other volatile aromatics in outdoor air. Talanta 1994, 41, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwah, I.; Sweet, S.; Pantano, J.; Knap, A. Light Hydrocarbon Geochemistry: Insight into Mississippian Crude Oil Sources from the Anadarko Basin, Oklahoma, USA. Geofluids 2019, 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, P.; Arguello, E.M.E.; Atwah, I. Evaluating the reliability of solid phase extraction techniques for hydrocarbon analysis by GC–MS. J Chromatogr A. 2024, 1737, 465435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwah, I.; Adeboye, O.O.; Zhang, J.; Wilcoxson, R.; Marcantonio, F. Linking biomarkers with elemental geochemistry to reveal controls on organic richness in Devonian-Mississippian mudrocks of Oklahoma. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2023, 611, 111355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, A.W.; Birrell, R.D.; Mann, A.T.; Humphreys, D.B.; Perdrix, J.L. Application of the mobile metal ion technique to routine geochemical exploration. J Geochem Explor. 1998, 61, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atwah, I.; Solovyeva, V.; Orlov, M. Methods and systems for detecting hydrocarbon microseepage from deep geological formations. Published online November 21. 2024, 55. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).