1. Introduction

Mössbauer Spectroscopy [

1] is a highly specialized technique that investigates the resonant absorption of

rays by atomic nuclei. The Mössbauer effect, observed primarily in isotopes such as iron-57 (

), provides information on hyperfine interactions, including isomer shifts, quadrupole splittings, and magnetic hyperfine fields. These parameters offer detailed information about the electronic, magnetic, and structural environment of the sample, making the technique invaluable in materials science, chemistry, and condensed matter physics. The gamma ray of resonant absorption in

nuclei is

14.4 keV and hyperfine interactions promote the break of degeneracy at the ground and excited nuclear levels. The above cited parameters are described in the following subsections:

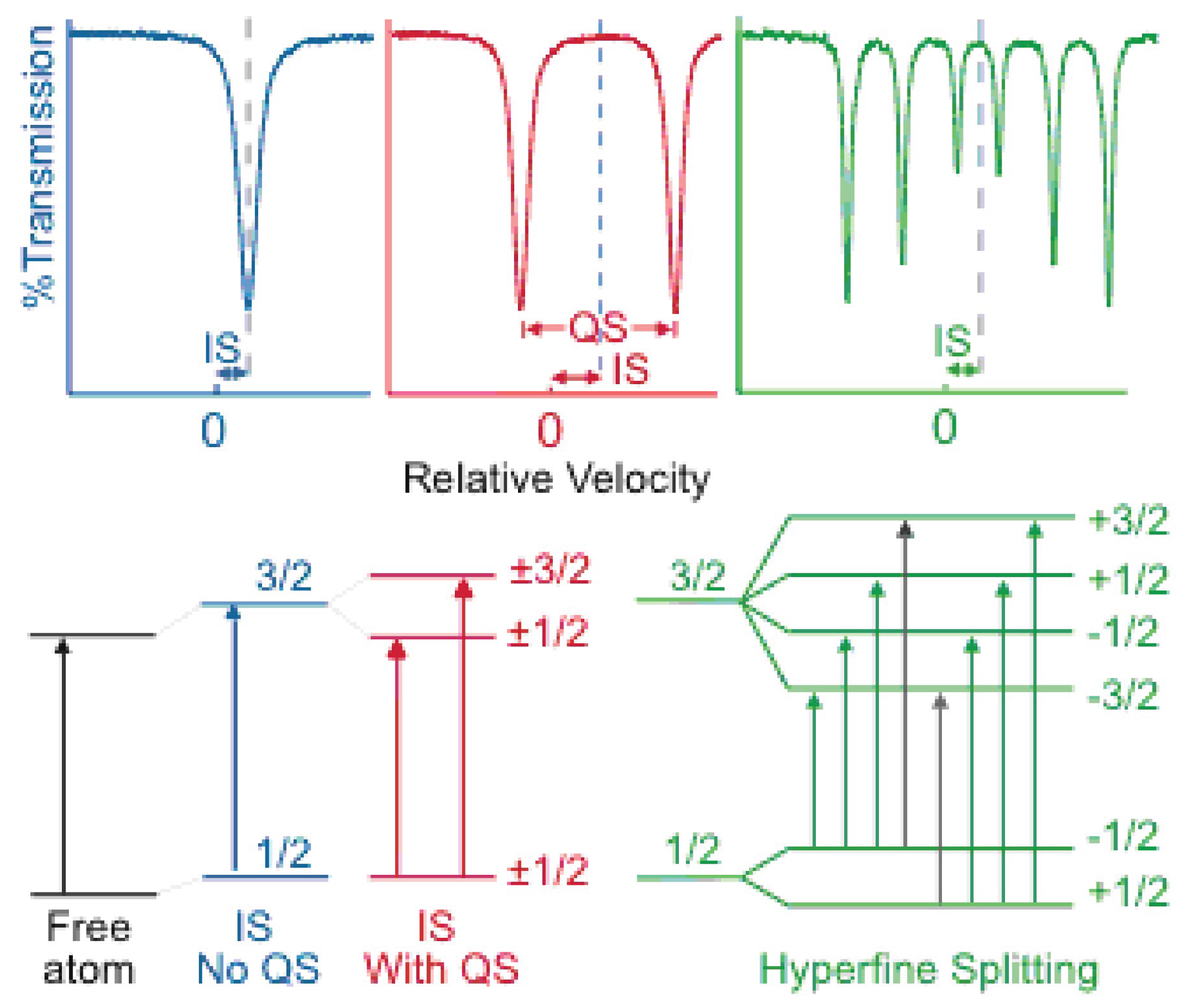

1.1. Isomer Shift, or

This phenomenon corresponds to a certain probability that s-electrons have to be inside the nucleus, an exclusive quantum event. The next equations describes this parameter

where

,

are the s-wavefunctions at the origin of the absorbent (A) and

-ray source (S) nucleus, while

is the relative nuclear radius

R change during recoilless

resonant absorption.

1.2. Quadrupole Splitting, or

This quantum effect gives account of the asymmetric electronic orbital distribution interacting with an electric field gradient (EFG). The analytical expression is

beeing

Q the quadrupolar moment,

the principal component of the EFG and

the asymmetric factor.

1.3. Magnetic Hyperfine Field,

Nucleons have an intrinsic quantum property, the spin. When the spin is coupled with the quantum orbital moment, a total moment can interact with the magnetic field originated in the dipolar electronic orbitals (Zeeman effect) giving then origin to a more complex splitting and, together with the Hund’s selection rules, allowed decays by ray emission.

The

Figure 1 shows the energy levels schemes of all of these hyperfine interactions.

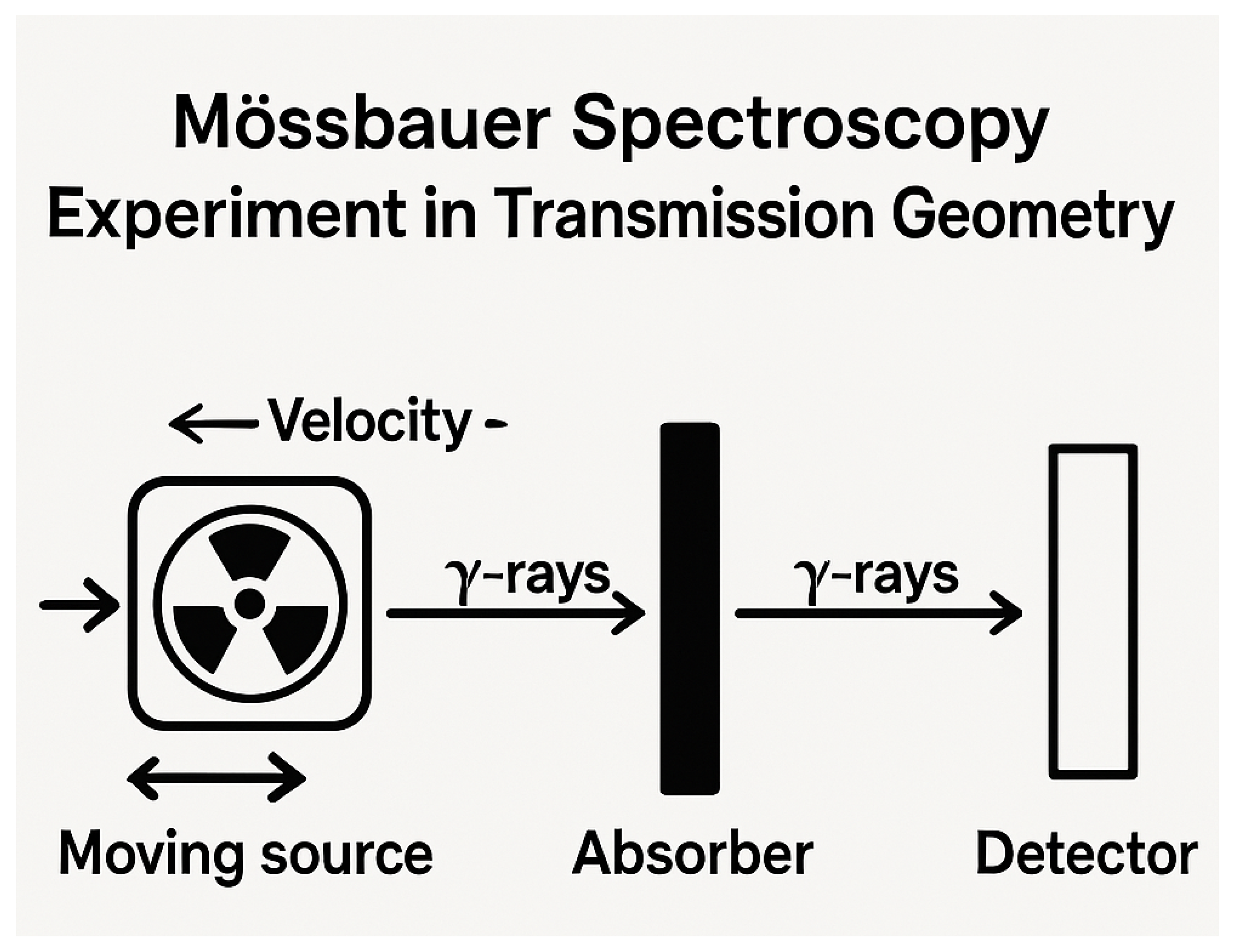

In a typical Mössbauer experiment, a radioactive source emits gamma rays, which are absorbed by the nuclei in the sample (see

Figure 2). Resonant absorption occurs, in a small fraction, when

rays hit the probe with recoilless. The detector measures the intensity of the transmitted radiation as a function of the velocity of the gamma-ray source (with an additional energy added by Doppler effect). This results in a Mössbauer spectrum, typically characterized by sharp peaks or dips at resonance frequencies corresponding to different hyperfine interactions within the sample. The most common experimental setup corresponds to

Transmission Geometry (in this case, the observed lines come from a reduction of

14.4 keV gamma counting in detector, as compared to the background signal). The other option is the

Conversion Electron Mössbauer Spectroscopy (CEMS) that corresponds to detection of back scattered electrons after gamma absorption.

1.4. Statement of Need

Recently, in a review by Grandjean et al. [

3], the authors made a series of suggestions about how good measurements should be taken, which could be a good practice for Mössbauer data treatment and its corresponding fitting presentation. Usually, thevscientists working with Mössbauer Spectroscopy manage their data and fit them with not open source softwares that run on Windows OS with poor upgrade services. The needs of an open source option with less OS or package dependency has motivated this work.

In this sense, Google Colab is a useful tool for a collaborative team job in data analysis with the advantage of no additional packages locally installed, also compatible with the fact that the user can run their codes from multiple devices.

2. Mössbauer Spectra and Curve Shapes

The shape of a Mössbauer spectrum varies depending on the nature of the hyperfine interactions in the sample. For example, a simple paramagnetic material might produce a single absorption peak (Lorentzian or Gaussian) due to the isomer shift. Materials with quadrupole splitting generate a doublet (two peaks), while materials experiencing magnetic hyperfine interactions often exhibit more complex sextet patterns. These spectral features often overlap, making it difficult to isolate and quantify each individual component.

2.1. Curve Fitting and Least Squares Method

Curve fitting plays a crucial role in Mössbauer spectral analysis, as it allows for the decomposition of these complex spectra into individual contributions, each associated with specific hyperfine parameters. The challenge lies in accurately reproducing the spectral shapes using mathematical models and adjusting the parameters until a satisfactory fit is achieved.

To accurately extract physical parameters from Mössbauer spectra, fitting procedures are applied to the experimental data. One of the most common approaches is the

least-squares method, which minimizes the difference between the experimental data points and the theoretical model curve. The objective is to adjust the parameters of the theoretical model (such as isomer shift, quadrupole splitting, and line broadening) so that the calculated spectrum fits the experimental data as closely as possible. Then, it is required a minimization of the

, defined as:

beeing

a set of selected parameters for fitting, which minimizes the distance between the experimental data,

and the modeled data points

.

In Python, this process can be implemented using libraries like Lmfit, SciPy, or NumPy, which provide robust tools for least-squares curve fit. The general approach involves defining a model function that represents the expected shape of the Mössbauer spectrum, which could be a sum of multiple Lorentzian or Gaussian functions, depending on the number and type of spectral components. Lorentzian functions are preferred with crystalline samples, while PseudoVoigts (sum of Lorentzian and Gaussian functions) are appropriated for Fe sites in disordered materials.

The least-squares fitting algorithm iteratively adjusts the model parameters until the sum of squared residuals between the experimental and calculated spectra is minimized. An example of Lorentzian function definition for Python, can be seen next,

from scipy.optimize import curve_fit

import numpy as np

# Define the model function (e.g., a sum of Lorentzian components)

def lorentzian(x, amplitude, center, width):

return amplitude * (width**2 / ((x − center)**2 + width**2))

# Generate synthetic data for fitting

x_data = np.linspace(-10, 10, 500) # Example velocity range

y_data = lorentzian(x_data, 1, 0, 1) + np.random.normal(0, 0.02,

size=len(x_data))

# Perform least-squares curve fitting

initial_guess = [1, 0, 1] # Initial guess for parameters

params, covariance = curve_fit(lorentzian, x_data, y_data,

p0=initial_guess)

# params contains the optimized parameters: amplitude, center,

and width

This example demonstrates fitting a single Lorentzian function to synthetic data, though more complex models involving sums of Lorentzians or other spectral shapes can be implemented to represent real Mössbauer spectra.

3. Description of the Python code for Google Colab (PyMossFit)

The

Python code is available in several

Jupyter notebooks as typical examples found in practice [

4]. In their names, some text is added that indicates the number and type of interactions (i.e., 1Q means one quadrupolar interaction, 2X for two magnetic sites and so on). Some selected parts of it are described throughout this page.

The code is structured in three cells. The first includes the installation in the Google Colab environment of Lmfit, the core of data fitting. Likewise, it imports some packages of Scipy, Pandas, Matplotlib and Numpy, among others. The next step includes a Drive connection that asks the user for permission.

The second cell reads the datafile (format should be inspected previously to define "delimiter", "columns" and "skiprows" parameters). The required inputs are date (in a YYYYMMDD format) and maximum velocity associated to the extreme channels, in order to define the velocity scale.

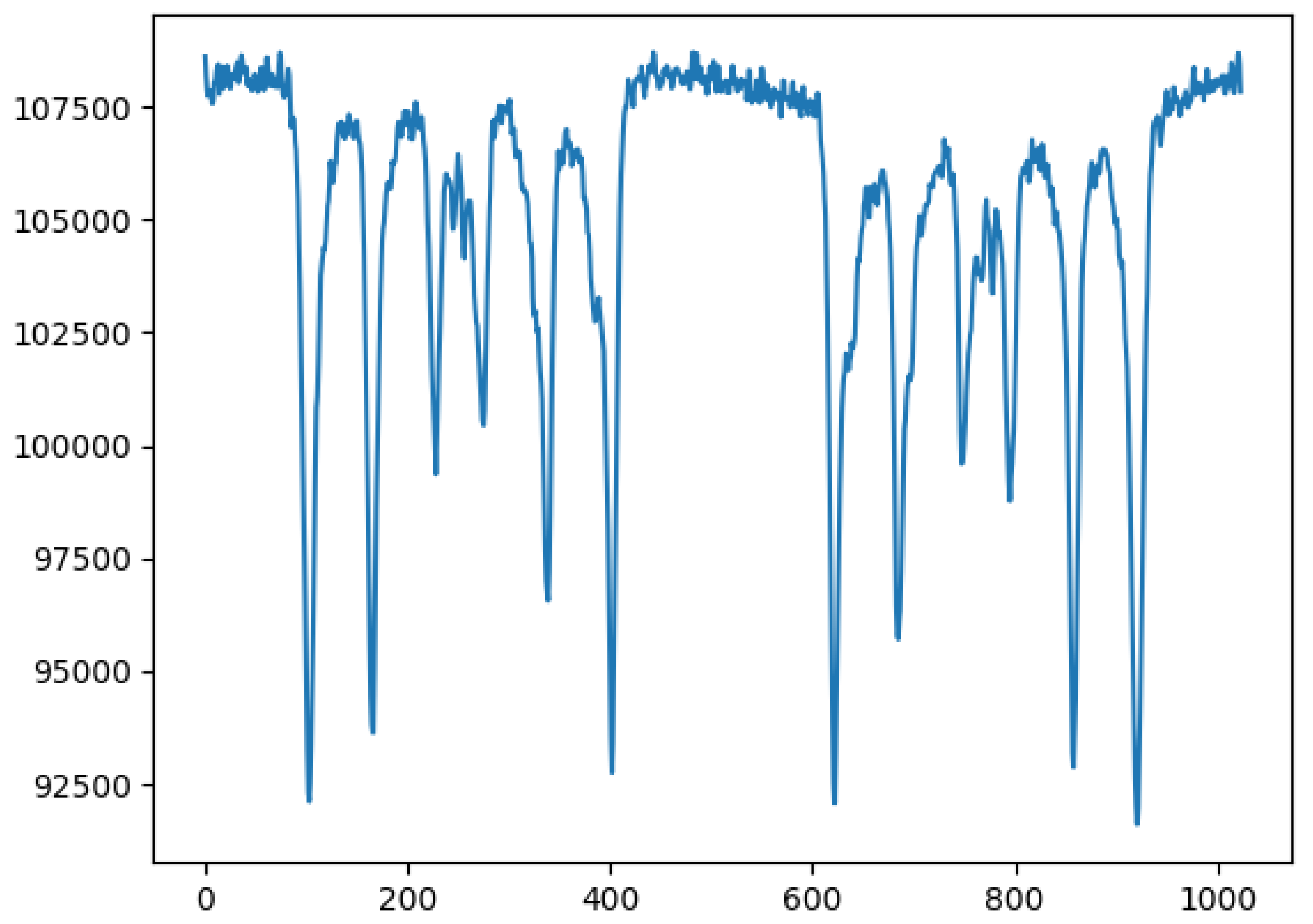

When raw data are plotted, they look as shown in the following because of the collection of absorption resonances converted to signals in a single-channel analyzer output, while the source moves back and forth.

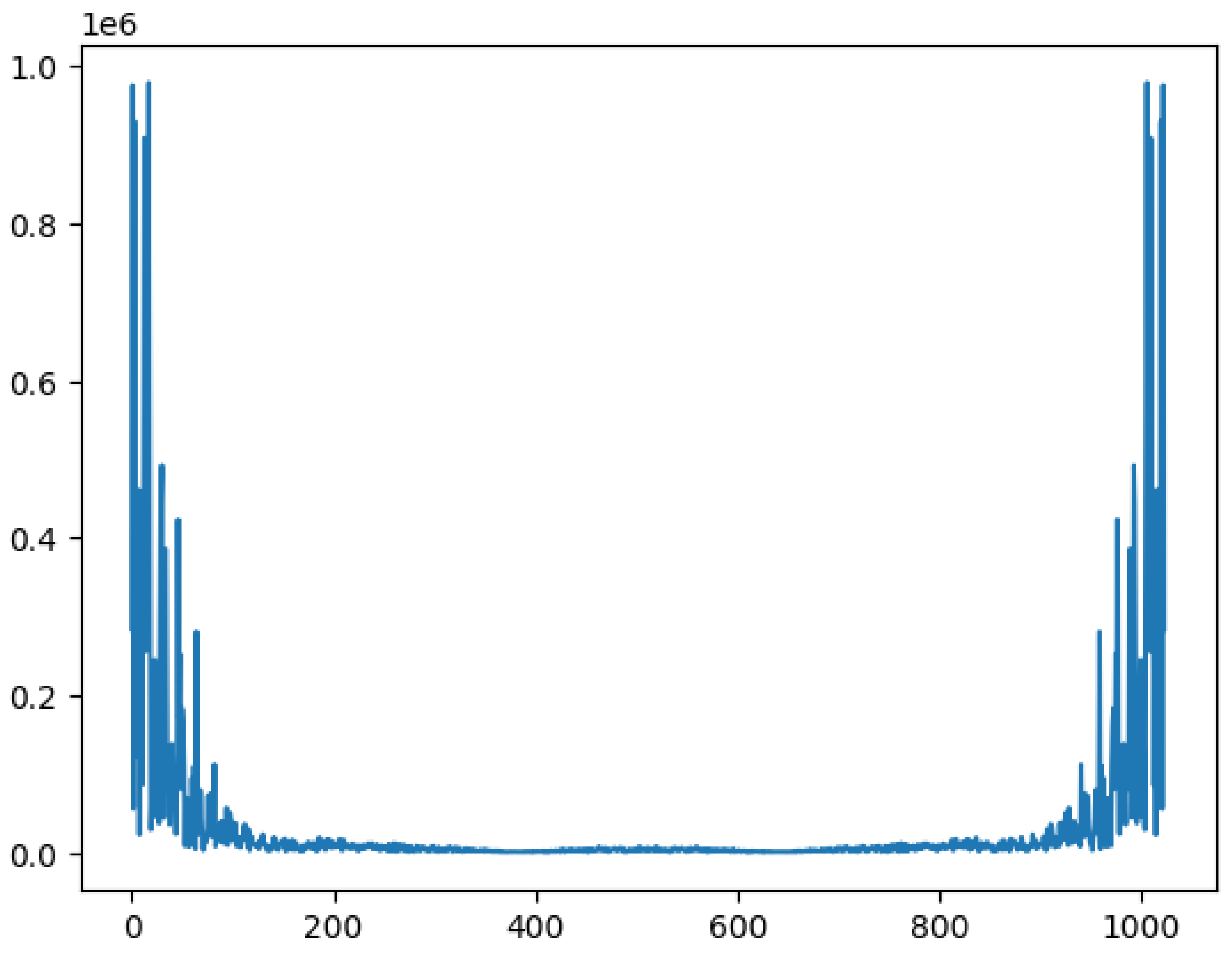

In this cell, spectrum folding is performed with a Discrete Fourier Transforming routine, the

Numpy fft. The theory of this procedure corresponds to the Nyquist-Shannon Sampling Theorem that helps to determine a folding channel from the symmetry of discrete Fourier spectra [

5].

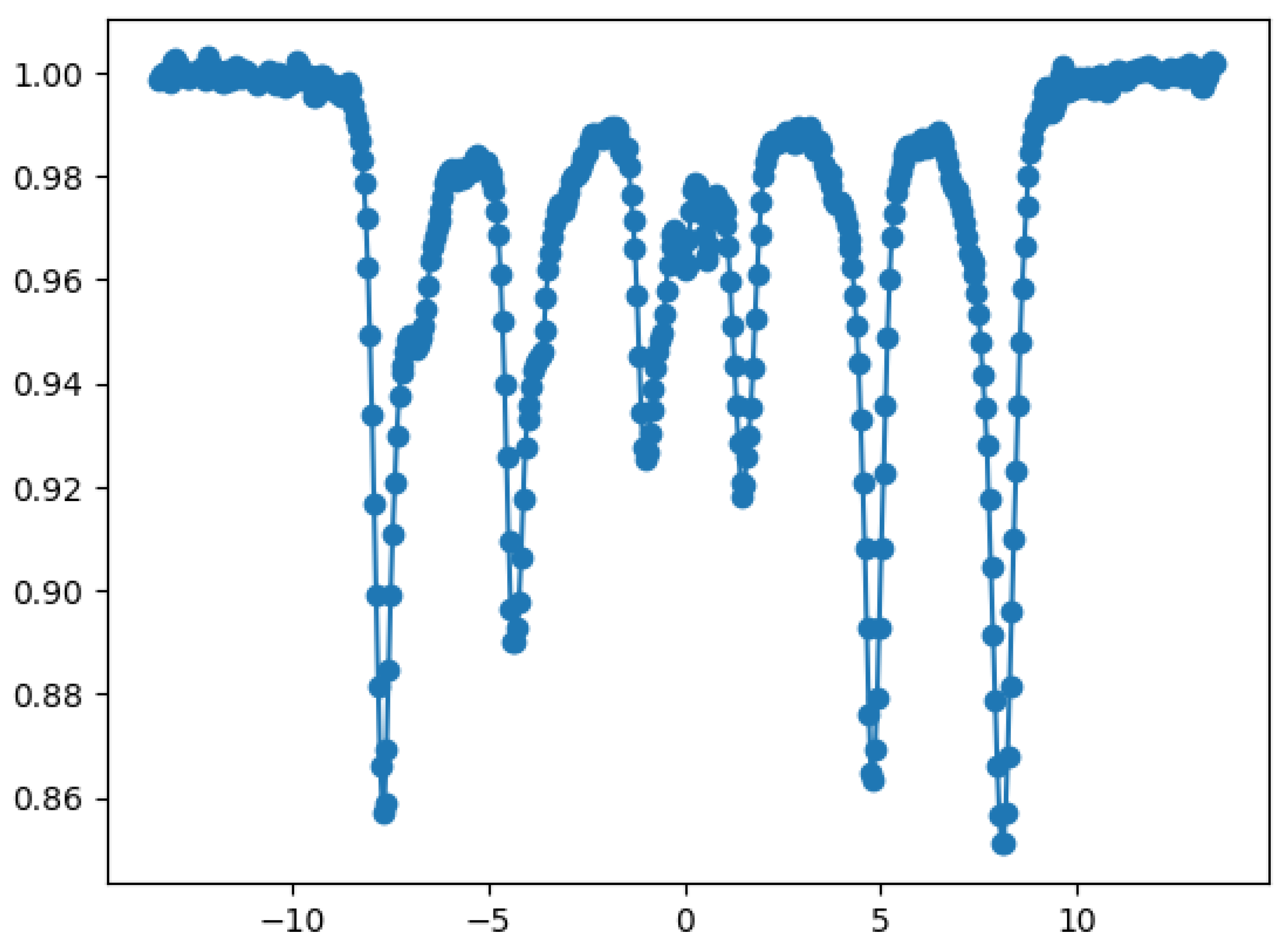

Data can also be smoothed using a Savitsky-Golay package (I use savgol from Scipy). After folding, a new datafile is saved for fit with the use of the next cell.

The next figures illustrate the partial plots of data management with this procedure.

Figure 3.

Unfolded plot of a raw Mossbauer experiment data.

Figure 3.

Unfolded plot of a raw Mossbauer experiment data.

Figure 4.

Discrete Fourier Transform of the raw Mossbauer experiment data ploted in the previous figure.

Figure 4.

Discrete Fourier Transform of the raw Mossbauer experiment data ploted in the previous figure.

Figure 5.

Final folded spectrum [

6].

Figure 5.

Final folded spectrum [

6].

The set of physical parameters such as linewidth (), isomer shifts (IS), quadrupole splitting (QS) and magnetic hyperfine field () are calculated after adjusting the amplitud (a), full width at half maximum (b), centroid (m), line shift (d) and line separation (q). Initial set of these parameters can be fitted or fixed by selecting the "True" or "False" options, respectively.

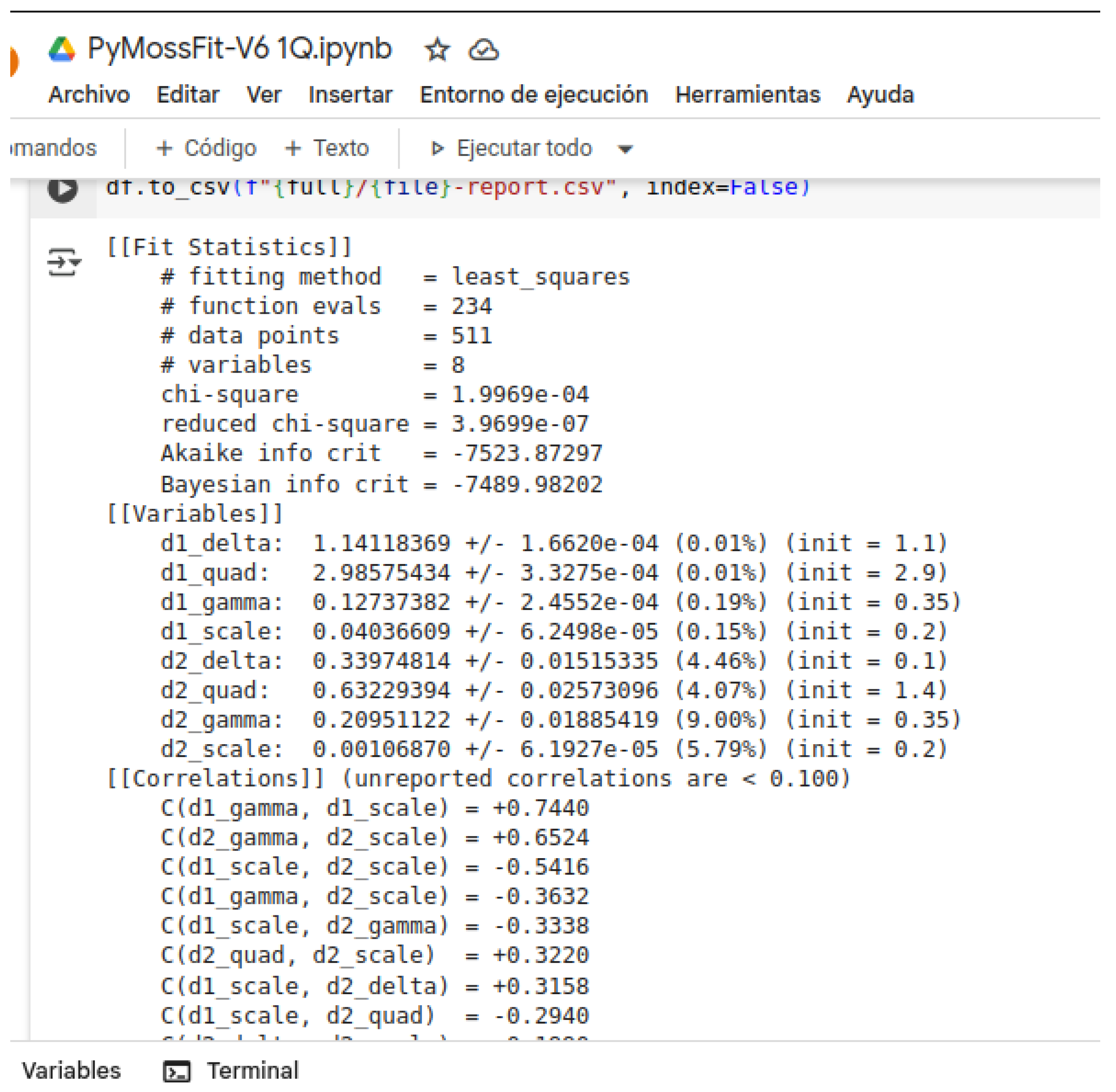

A typical fit report of the output of this cell looks as following:

Figure 6.

An example of a fit report output of a Jupyter notebook in Google Colab.

Figure 6.

An example of a fit report output of a Jupyter notebook in Google Colab.

Finally, the code saves fitted parameters, experimental and modeled sub-spectra in CSV formatted output files.

3.1. Some Examples

The following figures illustrate the fit results obtained from Mössbauer spectra of different samples. Each one exhibits several characteristics corresponding to the short range order neighborhood of probes.

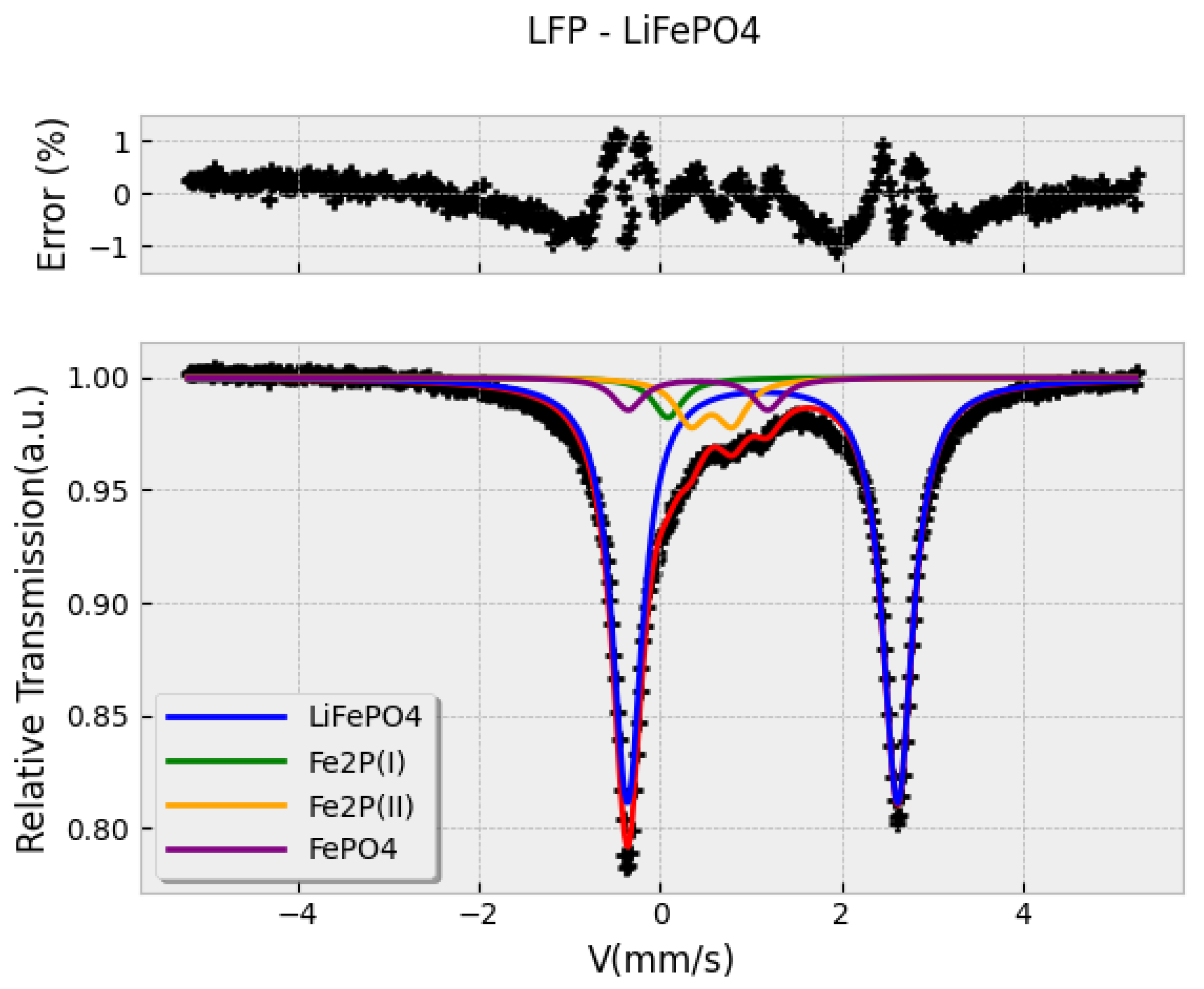

Figure 7.

Mössbauer spectrum of an aged commercial active material for batteries. Residual phases were detected, such as and . This last phase, shows the presence of in two different oxidation states, and , respectively.

Figure 7.

Mössbauer spectrum of an aged commercial active material for batteries. Residual phases were detected, such as and . This last phase, shows the presence of in two different oxidation states, and , respectively.

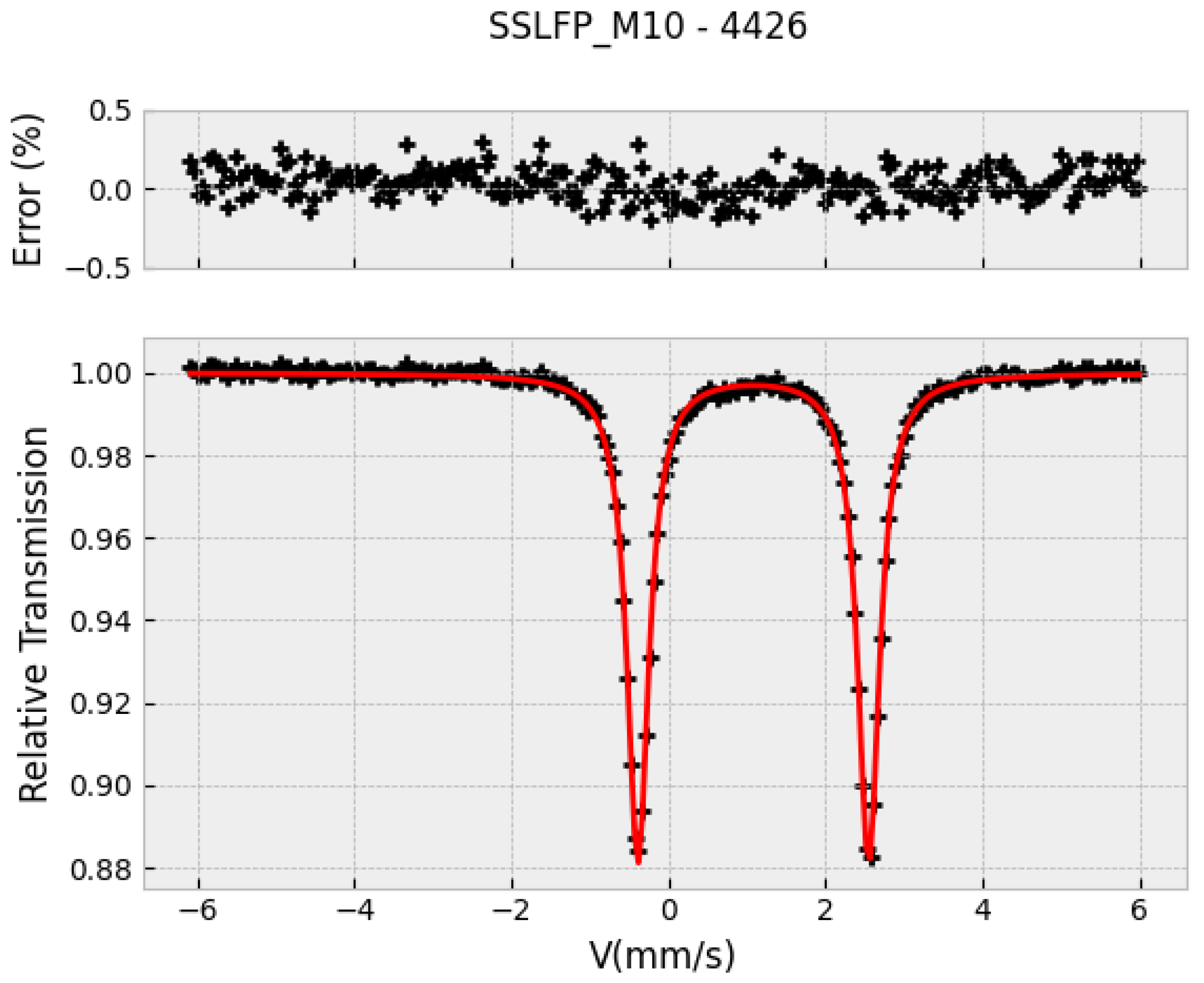

Figure 8.

Mössbauer spectrum of the active material for batteries, after synthesis at lab scale. In this case, just was detected, besides the extraordinary sensitivity of the characterization technique.

Figure 8.

Mössbauer spectrum of the active material for batteries, after synthesis at lab scale. In this case, just was detected, besides the extraordinary sensitivity of the characterization technique.

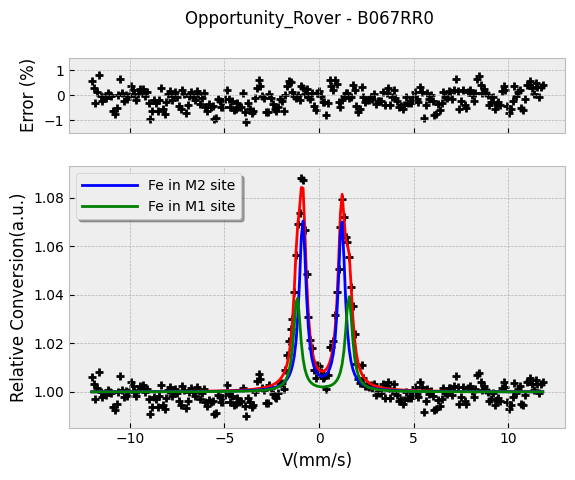

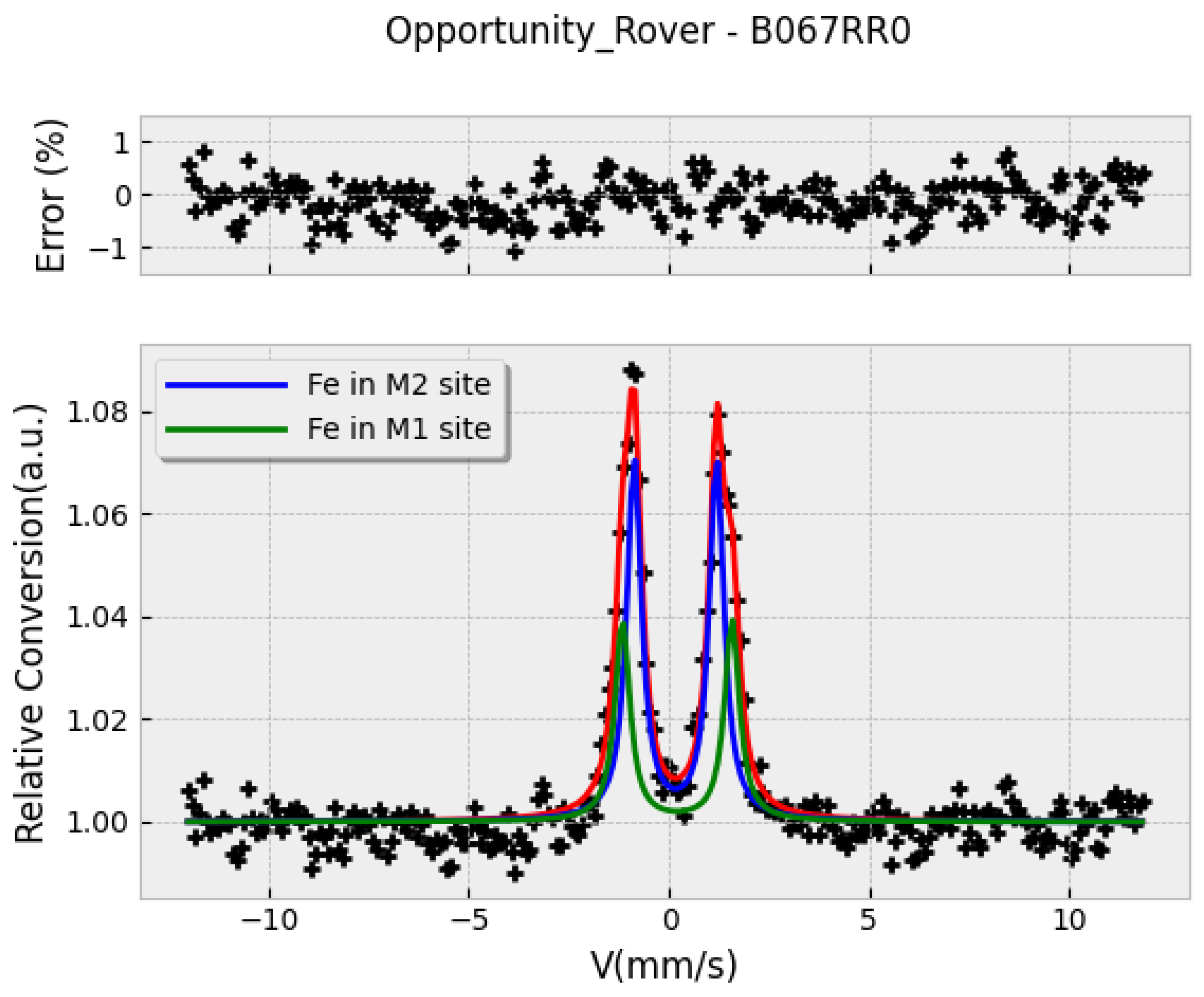

Figure 9.

CEMS spectrum of pyroxene in Mars soil (Opportunity Mission, Sept. 2004, T = 240-260K) [

7]. The subespectra correspond to two different

sites, M1 and M2, tipically found in pyroxene [

8].

Figure 9.

CEMS spectrum of pyroxene in Mars soil (Opportunity Mission, Sept. 2004, T = 240-260K) [

7]. The subespectra correspond to two different

sites, M1 and M2, tipically found in pyroxene [

8].

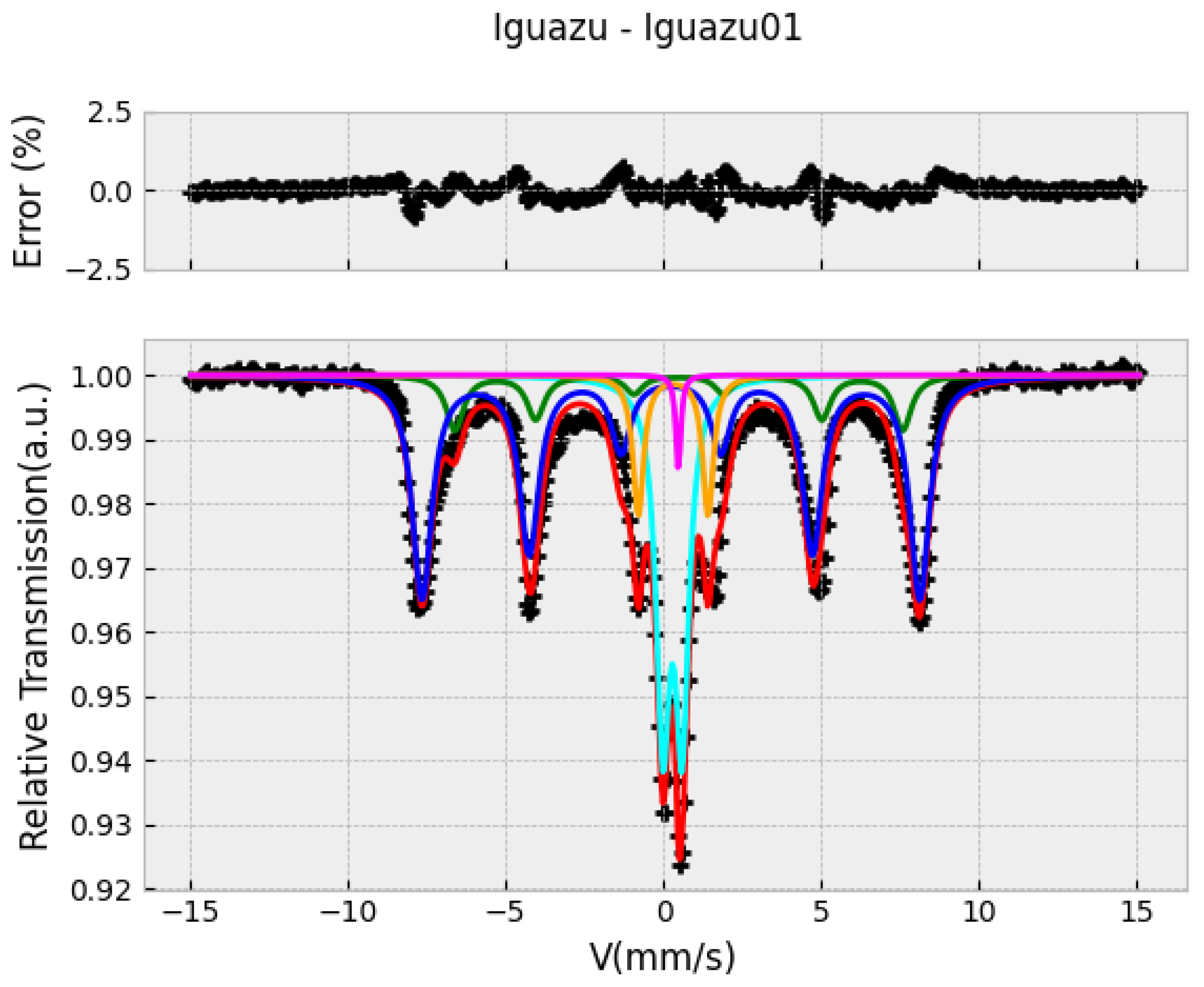

Figure 10.

Mössbauer spectra of an Iguazú falls soil sample (Argentina-Brazil border).

Figure 10.

Mössbauer spectra of an Iguazú falls soil sample (Argentina-Brazil border).

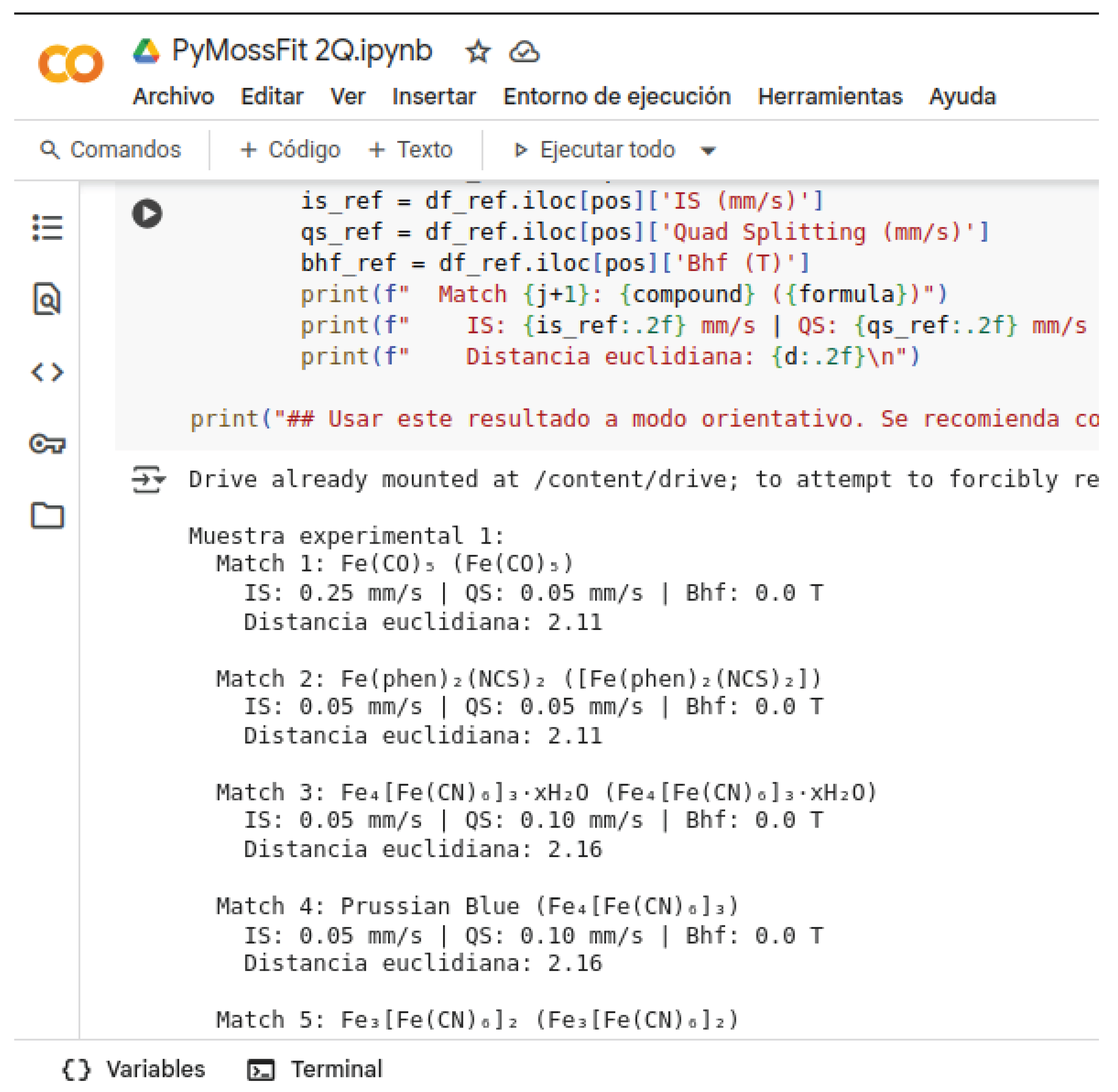

3.2. Match of Fitted Parameters with a Local Database

A final cell allows us to identify the phases from own database. This procedure is based on minimization of Eulerian distances of the set of parameters with the bibliographic collected ones collected, which can be updated or extended by the user. The Machine Learning algorithm employed to guess the present phases is based on a K-Nearest Neighbors (sklearn.neighbors). The output is a recommendation with a ranking of best-matching suggested phases.

Figure 11.

A match report obtained with a KNN algorithm for phase identification.

Figure 11.

A match report obtained with a KNN algorithm for phase identification.

4. Conclusions

PyMossFit is a tool for Mössbauer spectroscopy analysis. It was coded in Python and run in Jupyter notebook. The code requires the installation of the Lmfit package as the core of model fitting. PyMossFit was designed to work in Python environment at cloud computing services, such as Google Colab, beeing that a good choice for user update, free OS and device dependencies. Likewise, it simplifies the collaborative work during spectra analysis with the addition of a code section for phase identification based on a KNN algorithm.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks C. P. Ramos from Mōssbauer group of CNEA and the INTECIN(UBA-CONICET) team for sample measurement.

References

- Wikipedia contributors. Mössbauer spectroscopy—Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2025. [Online; accessed 19-June-2025].

- Dyar, M.D.; Agresti, D.G.; Schaefer, M.W.; Grant, C.A.; Sklute, E.C. MÖSSBAUER SPECTROSCOPY OF EARTH AND PLANETARY MATERIALS. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 2006, 34, 83–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, F.; Long, G.J. Best Practices and Protocols in Mössbauer Spectroscopy. Chemistry of Materials 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccone, F.D. Fitting code for Mössbauer Spectroscopy running in Jupyter Colab, 2025.

- Kong, Q.; Siauw, T.; Bayen, A. Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), 2020.

- Ferrari, S.; Apehesteguy, J.C.; Saccone, F.D. Structural and magnetic properties of Zn doped magnetite nanoparticles obtained by wet chemical method. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 2015, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corke, P.; Haviland, J. Mössbauer mineralogy of rock, soil, and dust at Meridiani Planum, Mars: Opportunity’s journey across sulfate-rich outcrop, basaltic sand and dust, and hematite lag deposits. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets 2006, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshtrakh, M.I.; Petrova, E.; Grokhovsky, V. Determination of quadrupole splitting for 57Fe in M1 and M2 sites of both olivine and pyroxene in ordinary chondrites using Mössbauer spectroscopy with high velocity resolution. Hyperfine Interactions 2007, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).