Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Literature Search Strategy

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Data Items

2.7. Assessment of Risk of Bias in Included Studies

2.8. Synthesis Methods

2.9. Measures of Treatment Effect

2.9.1. Dealing with Missing Data

2.9.2. Assessment of Heterogeneity

2.9.3. Sensitivity Analysis

2.10. Assessment of Reporting Bias

2.11. Assessment of the Certainty of the Evidence

3. Results

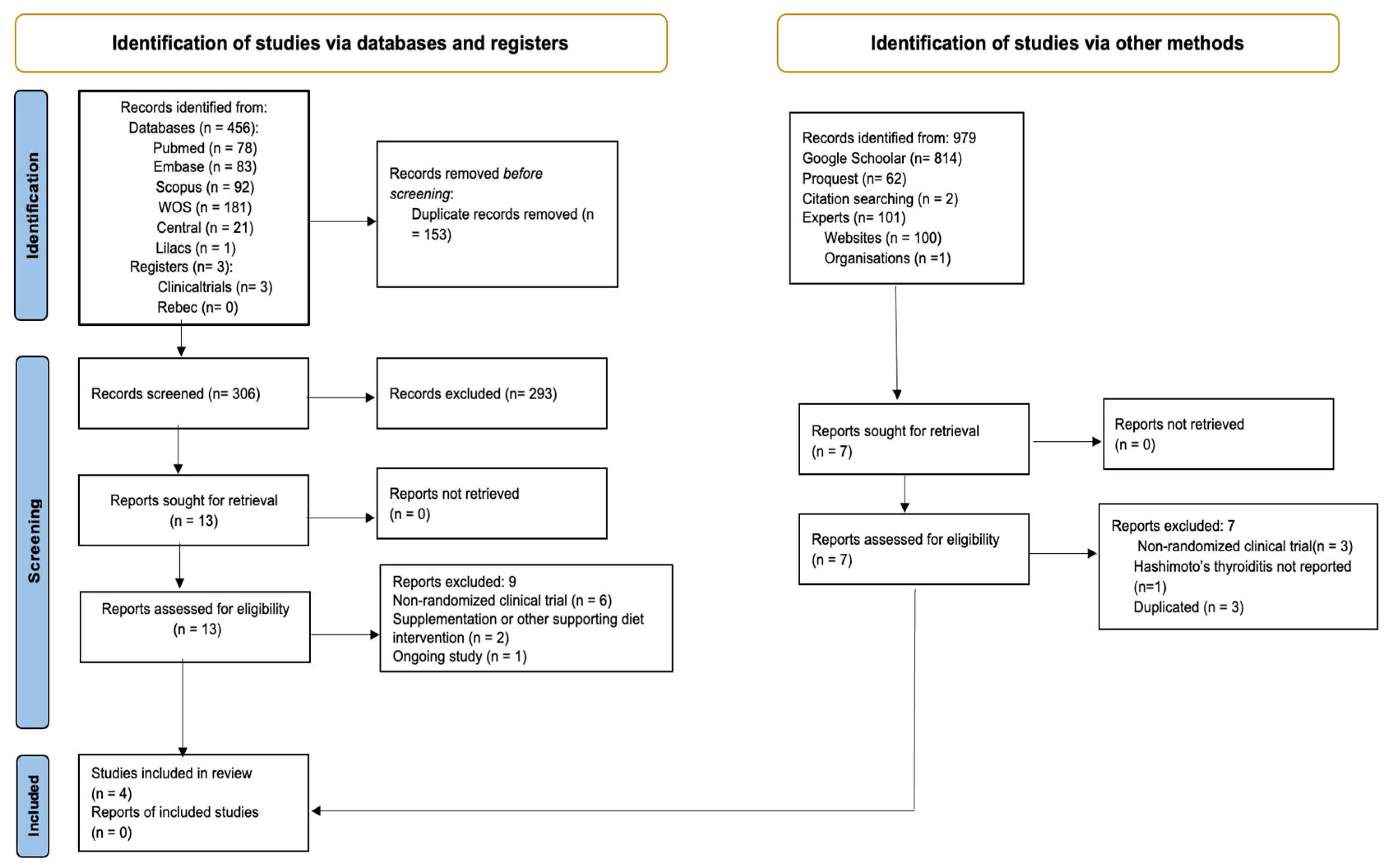

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Population Sociodemographic Characteristics

3.4. Risk of Bias in Studies

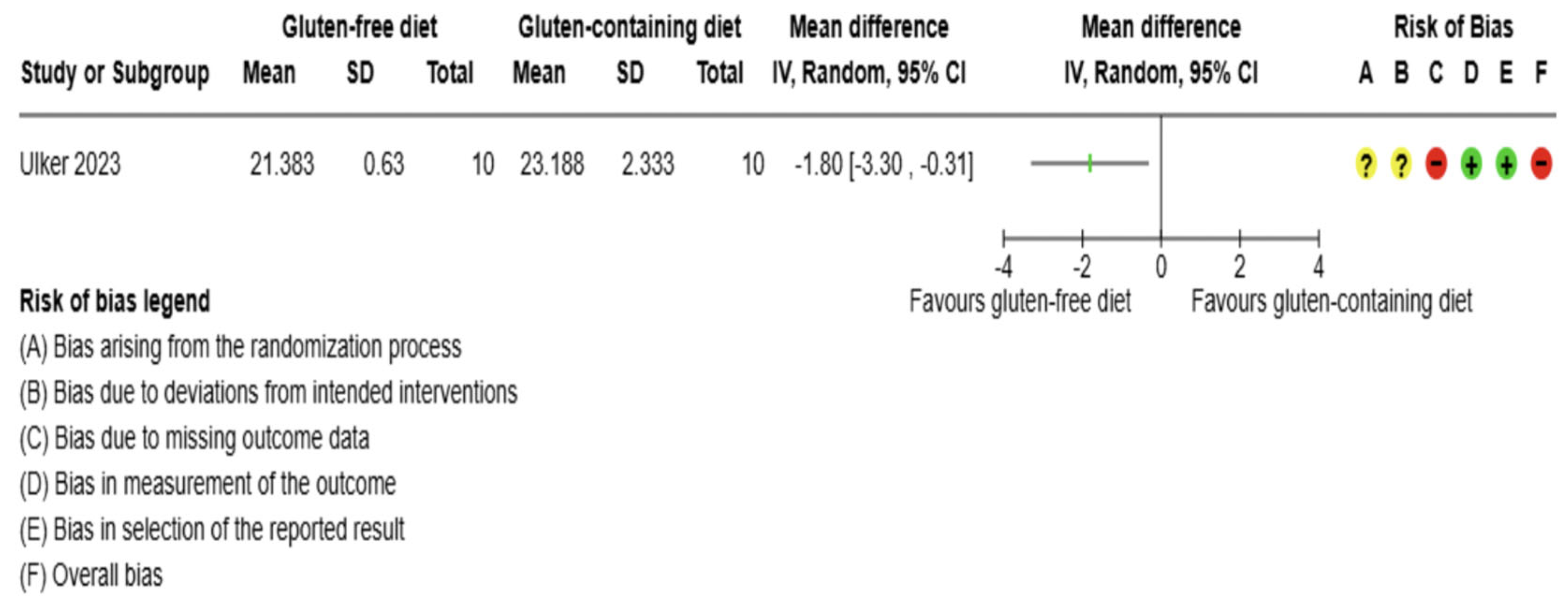

3.5. Effects of Interventions

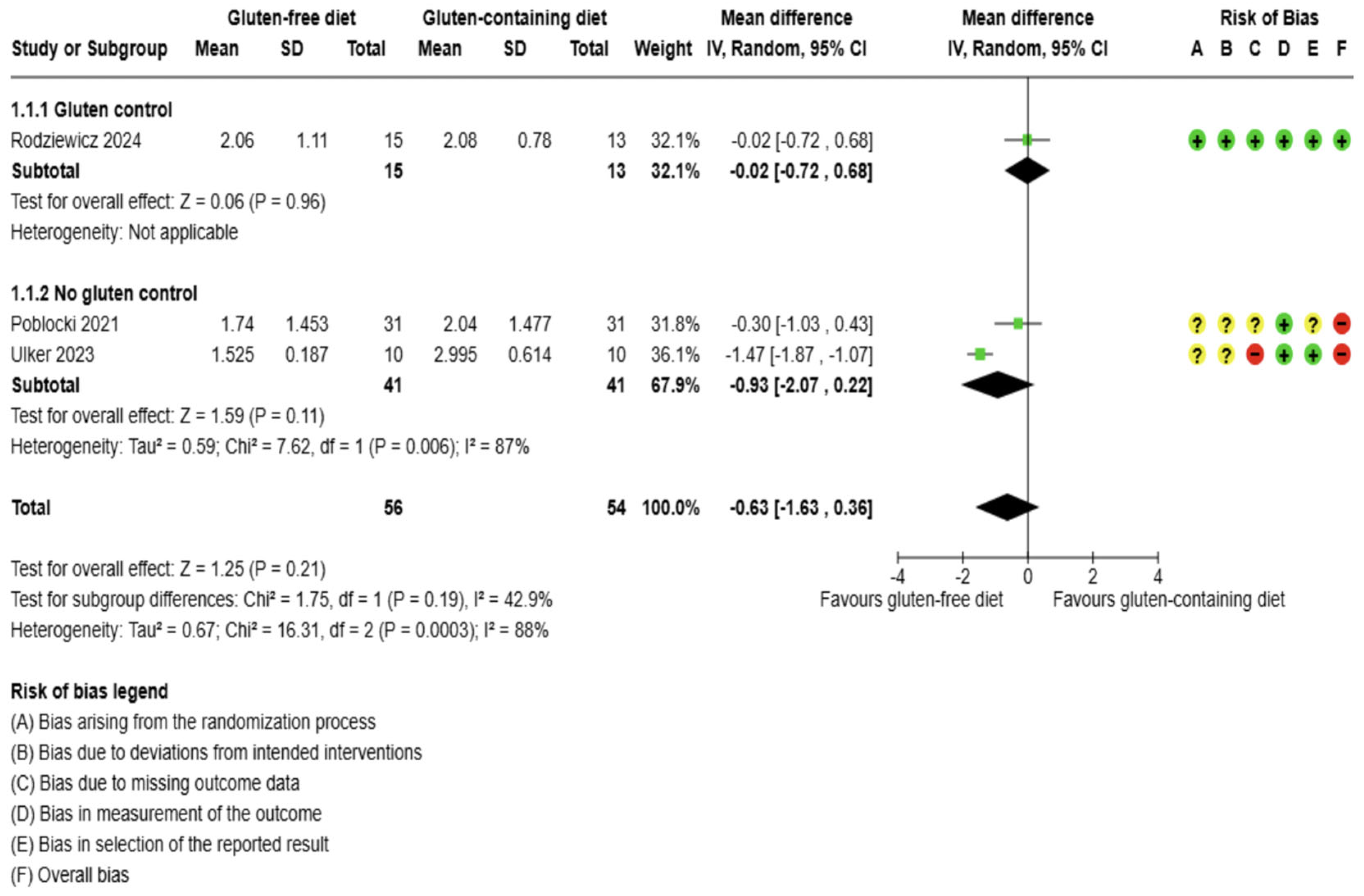

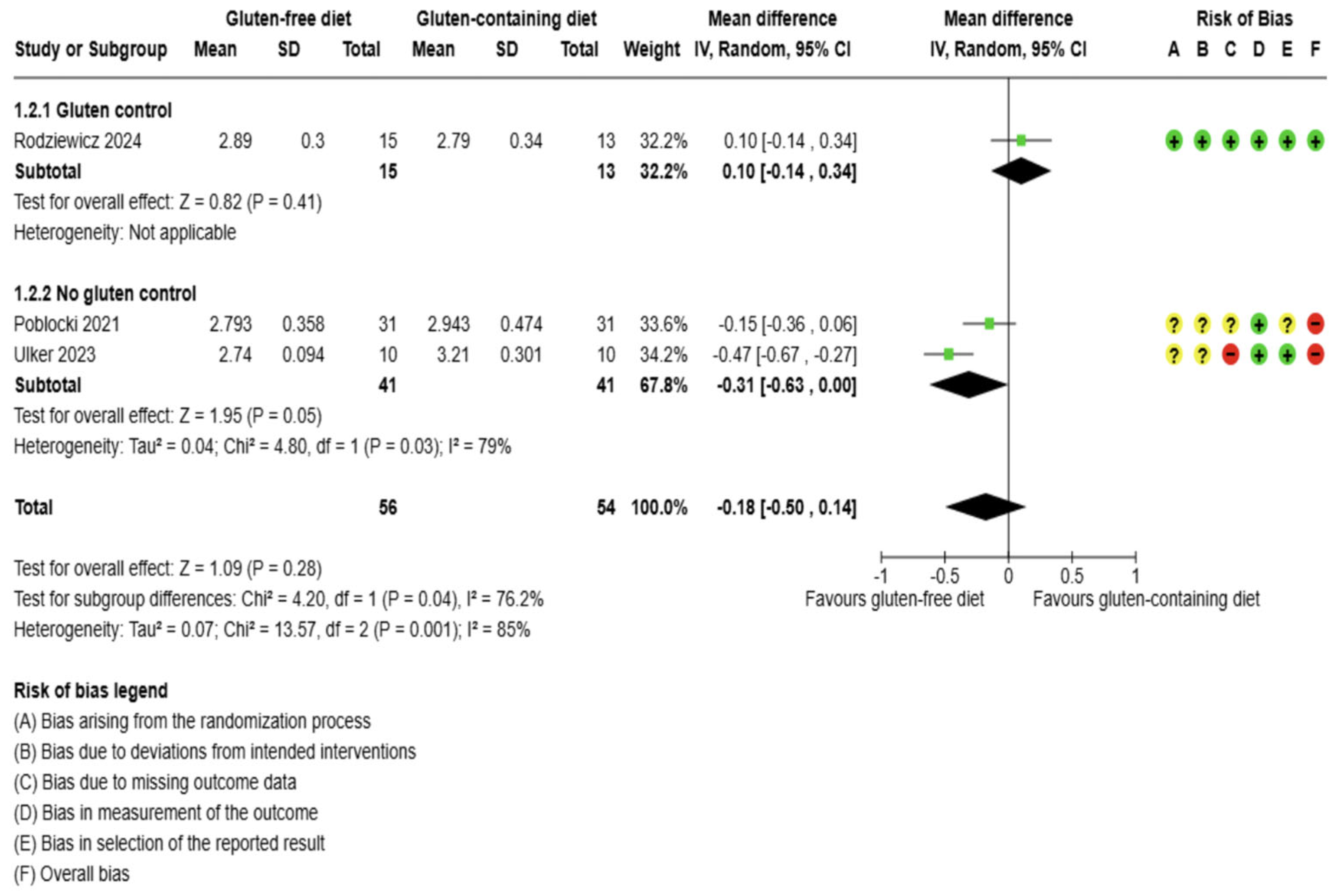

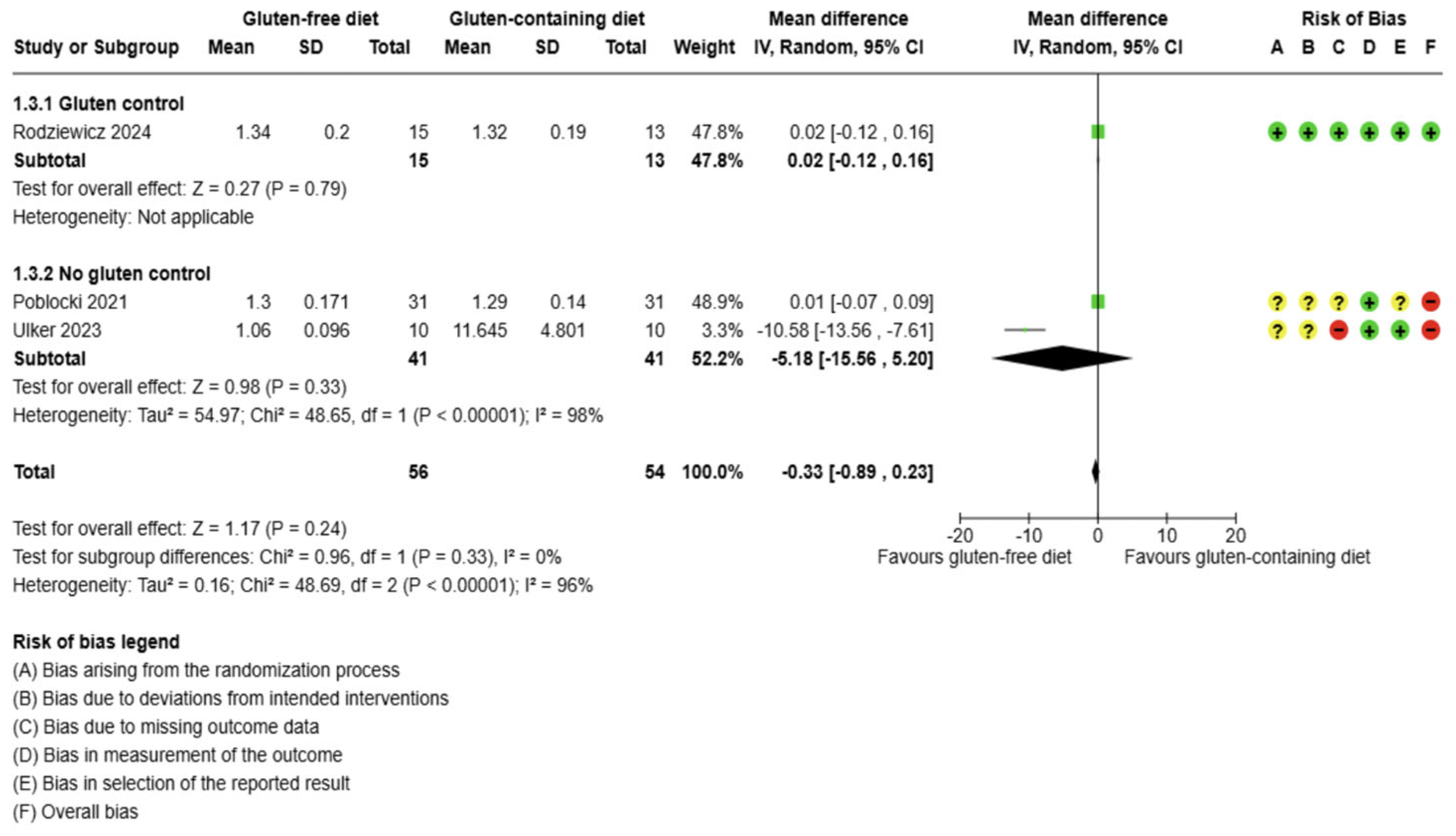

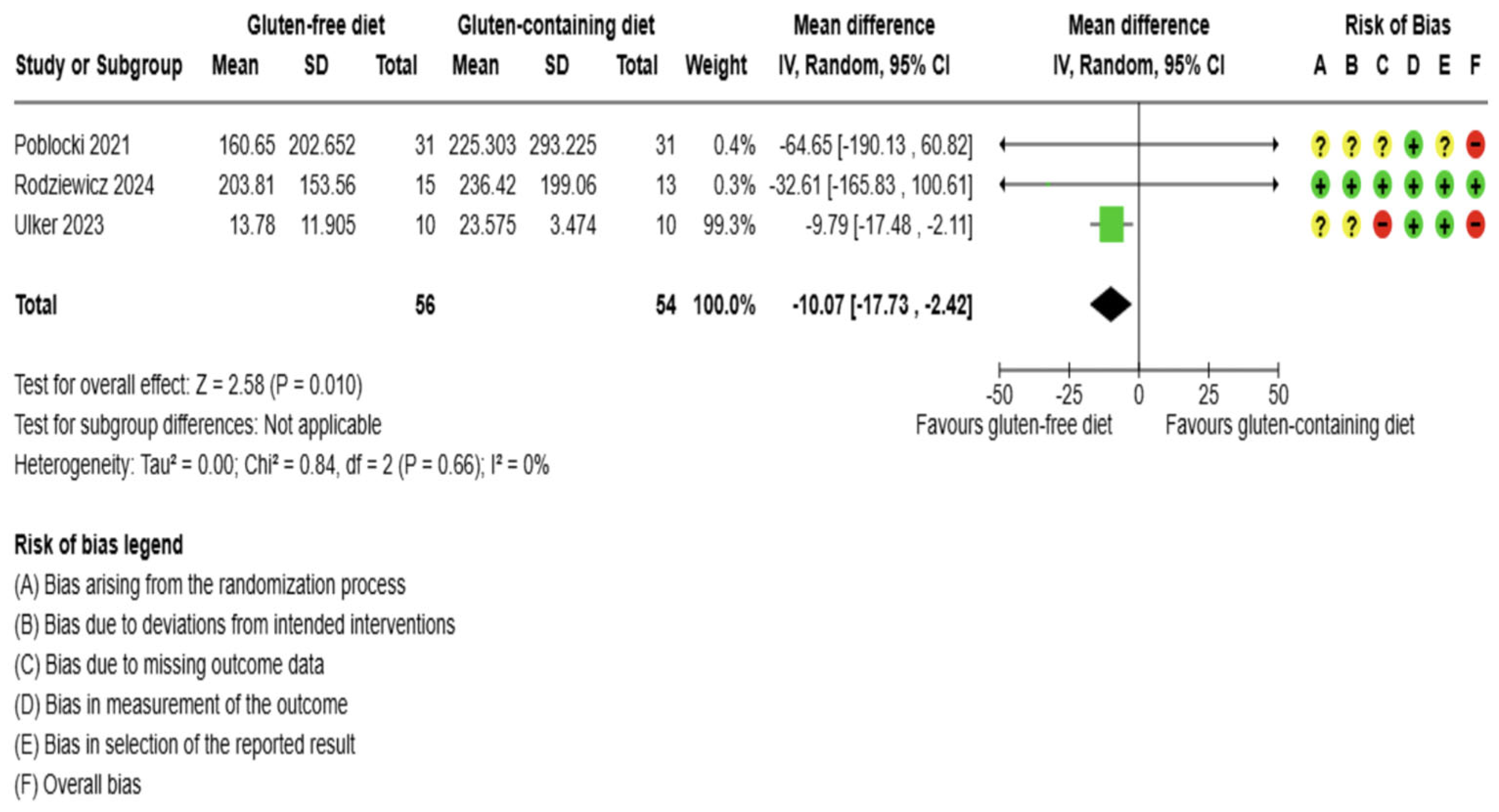

3.5.1. Thyroid Function Test Outcomes

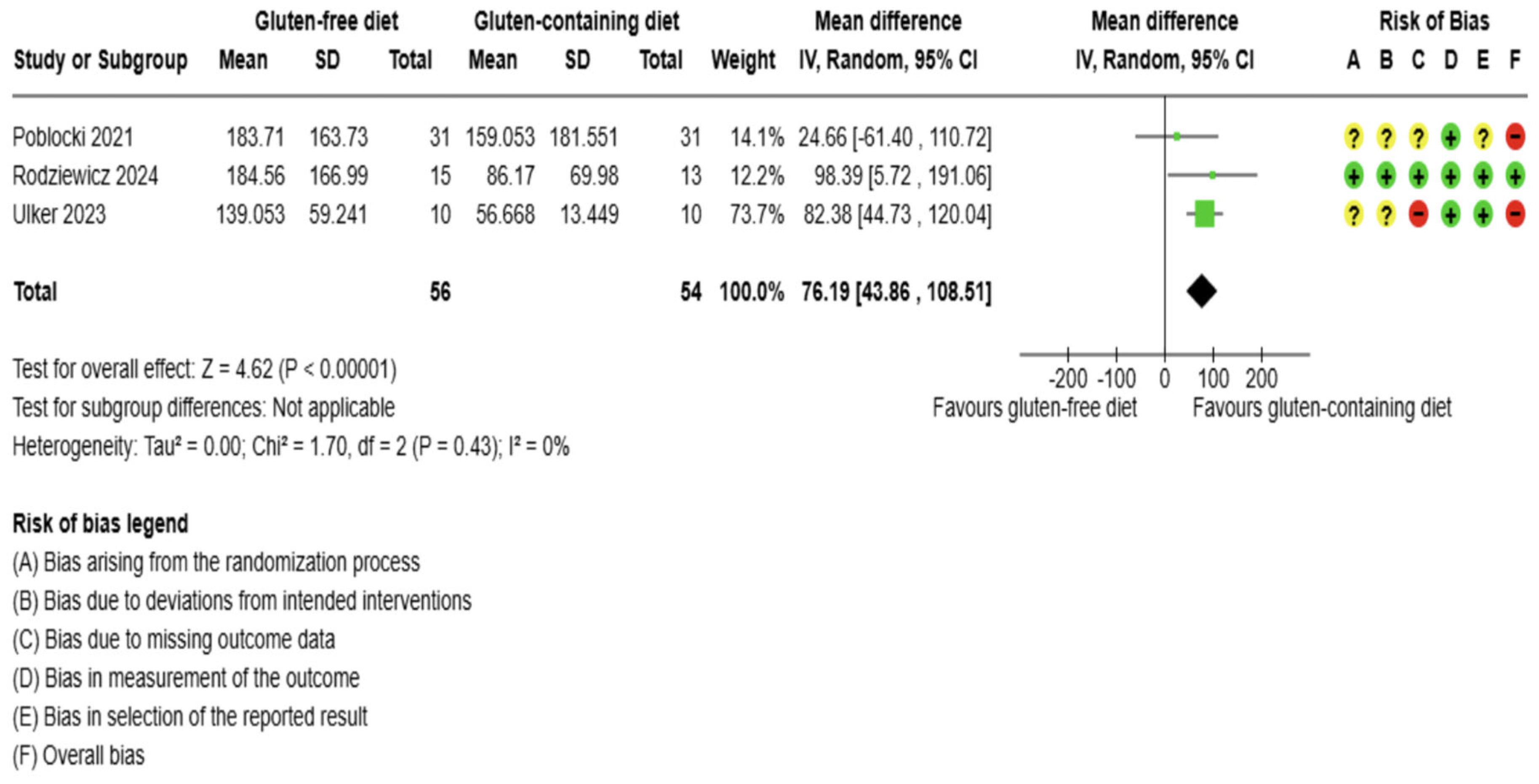

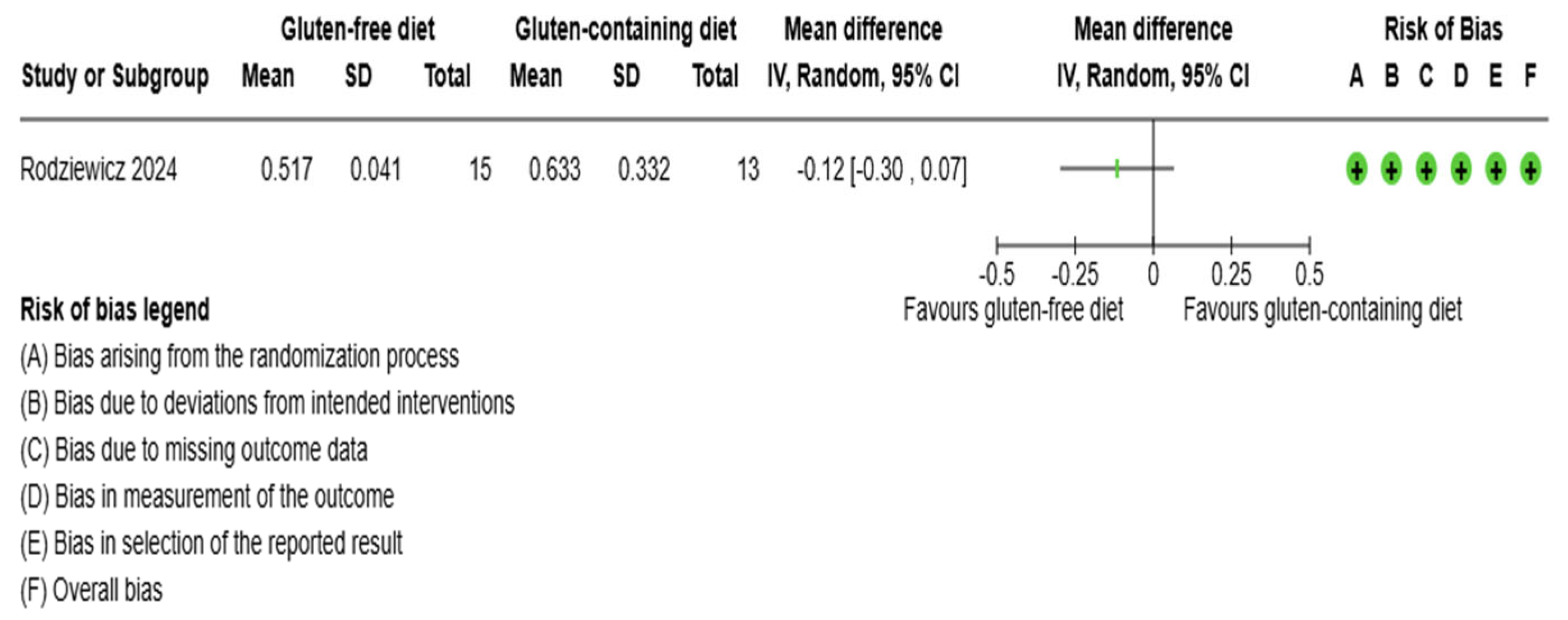

3.5.2. Immunological Biomarkers Outcomes

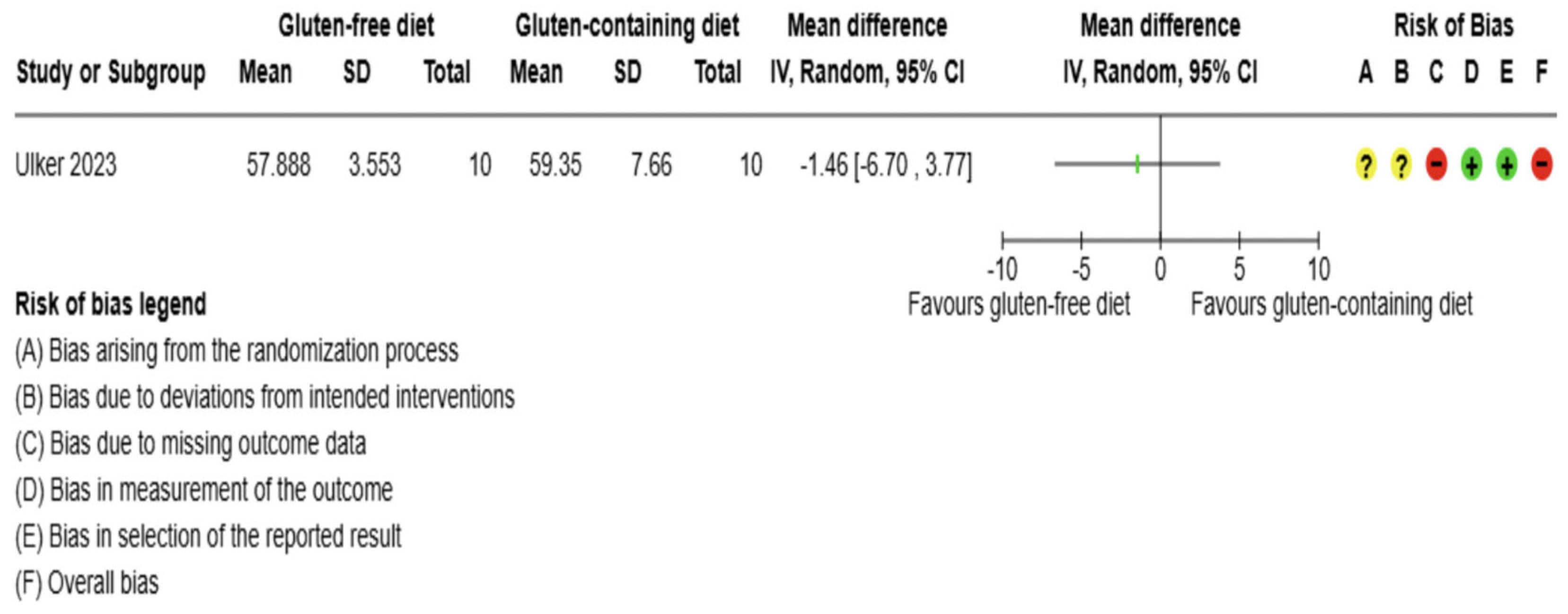

3.5.3. Inflammation Biomarker Outcome

3.5.4. Anthropometrics and Quality of Life Outcomes

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis

3.7. Assessment of Reporting Bias

3.8. Protocol Amendments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGE - Advanced Glycation end products; |

| AIP diet - Autoimmune Protocol diets; |

| AIT= Autoimmune thyroiditis; |

| BMI- body mass index; |

| CD - Celiac Disease; |

| CG - Control Group; |

| CI - confidence intervals; |

| COMET - Core Outcomes Measures in Effectiveness Trials; |

| CRP - C-reactive protein; |

| CXCR3: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 3; |

| DHA - docosahexaenoic acid; |

| DICA/BR diet - Brazilian cardio-protective diet; |

| DP - Standard deviation; |

| EPA - eicosapentaenoic acid; |

| F - Female; |

| fT3 - triiodothyronine; |

| fT4 - free tetraiodothyronine; |

| GFD - gluten-free diet; |

| GG - Gluten Group; |

| ID - Identification; |

| IP-10/CXCL10: Interferon gamma-induced protein; |

| ITT - the intention to treat; |

| Lilacs - Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature in the Virtual Health Library; |

| M - Male; |

| MD - mean difference; |

| NGS - Non-celiac gluten sensitivity; |

| OS - oxidation redox; |

| PG - Placebo Group; |

| PICOS - Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study; |

| PON-1 - antioxidant paraoxonase; |

| PRISMA - Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; |

| PRISMA-P - Reviews and Meta-Analyses Protocols; |

| PROSPERO - International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; |

| RCTs - Randomized Controlled Trial; |

| RRs - risk ratios; |

| SCFA - Short-chain fatty acids; |

| SD - Standard deviation; |

| Se - selenium; |

| SMD - standardized mean difference; |

| TAT - Thyroid antibodies; |

| TgAb - thyroglobulin antibodies; |

| Tg - Anti-thyroglobulin; |

| TH - Hashimoto’s thyroiditis; |

| TLR-2: Toll Like Receptor 2; |

| TNF: Tumor necrosis factor; |

| TPO - Anti-thyroid Peroxidase; |

| TRL-4: Toll Like Receptor 4; |

| TSH - Thyroid stimulating hormone; |

| UNEB: State University of Bahia; |

| UNIFESP: Federal University of São Paulo |

References

- Hiromatsu Y, Satoh H, Amino N. Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: History and Future Outlook. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Tywanek E, Michalak A, Świrska J, Zwolak A. Autoimmunity, New Potential Biomarkers and the Thyroid Gland-The Perspective of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis and Its Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(9). [CrossRef]

- McGrogan A, Seaman HE, Wright JW, De Vries CS. The incidence of autoimmune thyroid disease: a systematic review of the literature. Clinical endocrinology. 2008;69(5):687-96.

- Jin B, Wang S, Fan Z. Pathogenesis Markers of Hashimoto’s Disease—A Mini Review. Frontiers in Bioscience - Landmark. 2022;27(10).

- Ralli M, Angeletti D, Fiore M, D’Aguanno V, Lambiase A, Artico M, et al. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: An update on pathogenic mechanisms, diagnostic protocols, therapeutic strategies, and potential malignant transformation. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2020;19(10). [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Yuan J, Liu S, Tang M, Meng X, Wang X, et al. Investigating causal associations among gut microbiota, metabolites and autoimmune hypothyroidism: a univariable and multivariable Mendelian randomization study. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Asimi Z, Hadzovic-Dzuvo A, Al Tawil D. The effect of selenium supplementation and gluten-free diet in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism affected by autoimmune thyroiditis. Endocrine Abstracts. 2020;70(AEP906).

- Banga JP, Schott M. Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases. Hormone and metabolic research = Hormon- und Stoffwechselforschung = Hormones et metabolisme. 2018;50(12):837-9.

- Dadashi M, Guo M, First People G, Ke Ding C. Global prevalence and epidemiological trends of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers Public Health. 2022.

- Vargas-Uricoechea H. Molecular Mechanisms in Autoimmune Thyroid Disease. Cells. 2023;12(6). [CrossRef]

- Pereira C, Khan N, Ashraf GM, Kim J, Minakshi R, Rahman S, et al. Molecular Insights Into the Relationship Between Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases and Breast Cancer: A Critical Perspective on Autoimmunity and ER Stress. Frontiers in Immunology | wwwfrontiersinorg. 2019;1:344-.

- Abdalrahman S, Smail H, Shallal A. Genetic and epigenetic markers in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (Review). International Journal of Epigenetics. 2025;5(1):1-. [CrossRef]

- Lee HJ, Wun Li C, Salehi Hammerstad S, Stefan M, Tomer Y. Immunogenetics of Autoimmune Thyroid Diseases: A comprehensive Review HHS Public Access. J Autoimmun. 2015;64:82-90.

- Hu S, Rayman MP. Multiple Nutritional Factors and the Risk of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. Thyroid: Mary Ann Liebert Inc.; 2017. p. 597-610. [CrossRef]

- Osowiecka K, Myszkowska-Ryciak J. The Influence of Nutritional Intervention in the Treatment of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis-A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023;15(4). [CrossRef]

- Ajjan RA, Weetman AP. The Pathogenesis of Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: Further Developments in our Understanding. Hormone and Metabolic Research. 2015;47(10):702-10. [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri RM, Giovinazzo S, Barbalace MC, Cristani M, Alibrandi A, Vicchio TM, et al. Influence of Dietary Habits on Oxidative Stress Markers in Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. Thyroid. 2021;31(1):96-105. [CrossRef]

- Laganà M, Piticchio T, Alibrandi A, Le Moli R, Pallotti F, Campennì A, et al. Effects of Dietary Habits on Markers of Oxidative Stress in Subjects with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: Comparison Between the Mediterranean Diet and a Gluten-Free Diet. Nutrients. 2025;17(2). [CrossRef]

- Wang YS, Liang SS, Ren JJ, Wang ZY, Deng XX, Liu WD, et al. The Effects of Selenium Supplementation in the Treatment of Autoimmune Thyroiditis: An Overview of Systematic Reviews. Nutrients. 2023;15(14). [CrossRef]

- Riseh SH, Mobasseri M, Jafarabadi M-A, Farhangi MA, Ajorlou E. Nutritional intakes, lipid profile and serum apo-lipoproteins concentrations and their relationship with antithyroid, antigliadin and anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. 2016.

- Krysiak R, Kowalcze K, Okopień B. Gluten-free diet attenuates the impact of exogenous vitamin D on thyroid autoimmunity in young women with autoimmune thyroiditis: a pilot study. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2022;82(7-8):518-24. [CrossRef]

- Szczuko M, Kacprzak J, Przybylska A, Szczuko U, Pobłocki J, Syrenicz A, et al. The Influence of an Anti-Inflammatory Gluten-Free Diet with EPA and DHA on the Involvement of Maresin and Resolvins in Hashimoto’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(21). [CrossRef]

- Alahmadi AI, Al-Sowayan NS. The Impact of Gluten-Free Diet on Hormonal Balance. Journal of Biomedical Science and Engineering. 2024;17(11):225-33. [CrossRef]

- Peng Y, Liu C, Liu W, Gan R. Causal Relationship Between Gluten-Free Diet and Autoimmune-Related Disease Risk: A Comprehensive Mendelian Randomization Study. International Journal of Medical Sciences. 2025;22(2):432-40. [CrossRef]

- Niland B, Cash BD. Health Benefits and Adverse Effects of a Gluten-Free Diet in Non–Celiac Disease Patients. 2018 2018/2//.

- Ostrowska L, Gier D, Zyśk B. The influence of reducing diets on changes in thyroid parameters in women suffering from obesity and hashimoto’s disease. Nutrients. 2021;13(3):1-17. [CrossRef]

- Krysiak R, Szkróbka W, Okopień B. The Effect of Gluten-Free Diet on Thyroid Autoimmunity in Drug-Naïve Women with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis: A Pilot Study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2019;127(7):417-22. [CrossRef]

- Ihnatowicz P, Gębski J, Drywień ME. Effects of Autoimmune Protocol (AIP) diet on changes in thyroid parameters in Hashimoto’s disease. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 2023;30(3):513-21. [CrossRef]

- Cardo A, Churruca I, Lasa A, Navarro V, Vázquez-Polo M, Perez-Junkera G, et al. Nutritional Imbalances in Adult Celiac Patients Following a Gluten-Free Diet _ Enhanced Reader. Nutrients. 2021;13:2-18.

- Shulhai AM, Rotondo R, Petraroli M, Patianna V, Predieri B, Iughetti L, et al. The Role of Nutrition on Thyroid Function. Nutrients. 2024;16(15). [CrossRef]

- Drago S, El Asmar R, Di Pierro M, Clemente MG, Tripathi A, Sapone A, et al. Gliadin, zonulin and gut permeability: Effects on celiac and non-celiac intestinal mucosa and intestinal cell lines. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2006;41(4):408-19.

- Effraimidis G, Wiersinga WM. Mechanisms in endocrinology: Autoimmune thyroid disease: Old and new players. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2014;170(6). [CrossRef]

- Lerner A, Freire De Carvalho J, Kotrova A, Shoenfeld Y. Gluten-free diet can ameliorate the symptoms of non-celiac autoimmune diseases. Nutrition Reviews. 2022;80(3):525-43. [CrossRef]

- Carroccio A, Alcamo AD, Cavataio F, Soresi M, Seidita A, Sciumè C, et al. High Proportions of People With Nonceliac Wheat Sensitivity Have Autoimmune Disease or Antinuclear Antibodies. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Gong B, Wang C, Meng F, Wang H, Song B, Yang Y, et al. Association Between Gut Microbiota and Autoimmune Thyroid Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Article. 2021;12:1-. [CrossRef]

- Duan H, Wang LJ, Huangfu M, Li H. The impact of microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids on macrophage activities in disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic potentials. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy: Elsevier Masson s.r.l.; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Demir E, Önal B, Özkan H, Utku İ K, Şahtiyancı B, Kumbasar A, et al. The relationship between elevated plasma zonulin levels and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Turk J Med Sci. 2022;52(3):605-12. [CrossRef]

- Kreutz JM, Heynen L, Vreugdenhil ACE. Nutrient deficiencies in children with celiac disease during long term follow-up. Clin Nutr. 2023;42(7):1175-80. [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulou K, Nichols B, Mackinder M, Biskou O, Rizou E, Karanikolou A, et al. Alterations in Intestinal Microbiota of Children With Celiac Disease at the Time of Diagnosis and on a Gluten-free Diet. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(6):2039-51.e20. [CrossRef]

- Krzysiek U, Podgórska K, Puła A, Artykiewicz K, Urbaś W, Grodkiewicz M, et al. Does a gluten-free diet affect the course of Hashimoto’s disease? - the review of the literature. Journal of Education, Health and Sport. 2022;13(1):173-7. [CrossRef]

- Macculloch K, Rashid M, Med M. Factors affecting adherence to a gluten-free diet in children with celiac disease. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19(6):305-. [CrossRef]

- Koning F. Adverse Effects of Wheat Gluten. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;67(2):8-14. [CrossRef]

- El-Chammas K, Danner E. Gluten-Free Diet in Nonceliac Disease. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2011;26. [CrossRef]

- Diamanti A, Capriati T, Bizzarri C, Ferretti F, Ancinelli M, Romano F, et al. Autoimmune diseases and celiac disease which came first: genotype or gluten? Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12(1):67-77.

- Motazedian N, Sayadi M, Mashhadiagha A, Ali Moosavi S, Khademian F, Niknam R. Metabolic Syndrome in Celiac Disease: What Does Following a One-Year Gluten-Free Diet Bring? Iranian Association of Gastroerterology and Hepatology. 2023;15(3):185-9.

- Cosnes J, Cellier C, Viola S, Colombel JF, Michaud L, Sarles J, et al. Incidence of autoimmune diseases in celiac disease: protective effect of the gluten-free diet. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(7):753-8. [CrossRef]

- Sategna-Guidetti C, Volta U, Ciacci C, Usai P, Carlino A, De Franceschi L, et al. Prevalence of thyroid disorders in untreated adult celiac disease patients and effect of gluten withdrawal: An Italian multicenter study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;96(3):751-7.

- Piticchio T, Frasca F, Malandrino P, Trimboli P, Carrubba N, Tumminia A, et al. Effect of gluten-free diet on autoimmune thyroiditis progression in patients with no symptoms or histology of celiac disease: a meta-analysis OPEN ACCESS EDITED BY REVIEWED BY. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1200372-.

- Di Sabatino A, Giuffrida P, Fornasa G, Salvatore C, Vanoli A, Naviglio S, et al. Innate and adaptive immunity in self-reported nonceliac gluten sensitivity versus celiac disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48(7):745-52. [CrossRef]

- Di Sabatino A, Volta U, Salvatore C, Biancheri P, Caio G, De Giorgio R, et al. Small Amounts of Gluten in Subjects With Suspected Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Cross-Over Trial. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2015;13(9):1604-12.e3. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2019:1-694.

- McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, Cogo E, Foerster V, Lefebvre C. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 Guideline Statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2016;75:40-6. [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews. 2016;5(1):210. [CrossRef]

- Williamson PR, Altman DG, Blazeby JM, Clarke M, Gargon E. The COMET (Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials) Initiative. Trials. 2011(1745-6215 (Electronic)). [CrossRef]

- Ülker MT, Çolak GA, Baş M, Erdem MG. Evaluation of the effect of gluten-free diet and Mediterranean diet on autoimmune system in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Food Sci Nutr. 2024;12(2):1180-8. [CrossRef]

- Pludowski P, Takacs I, Boyanov M, Belaya Z, Diaconu CC, Mokhort T, et al. Clinical Practice in the Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Vitamin D Deficiency: A Central and Eastern European Expert Consensus Statement. Nutrients. 2022;14(7). [CrossRef]

- Higgins J, Savović J, Page M, Elbers R, Sterne J. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial [last updated October 2019]. In: Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. Cochrane, 2024. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14(1):135. [CrossRef]

- Pudar-Hozo S, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2005;13:1-10. [CrossRef]

- Page M, Higgins J, Sterne J. Chapter 13: Assessing risk of bias due to missing evidence in a meta-analysis [last updated August 2024]. Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. Cochrane, 2024. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Schünemann H, Higgins J, Vist G, Glasziou P, Akl E, Skoetz N, et al. Chapter 14: Completing ‘Summary of findings’ tables and grading the certainty of the evidence [last updated August 2023]. Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al., editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.5. Cochrane, 2024. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. New York1988. 567 p.

- Pobłocki J, Pańka T, Szczuko M, Telesiński A, Syrenicz A. Whether a Gluten-Free Diet Should Be Recommended in Chronic Autoimmune Thyroiditis or Not?-A 12-Month Follow-Up. J Clin Med. 2021;10(15). [CrossRef]

- Rodziewicz A, Szewczyk A, Bryl E. Gluten-Free Diet Alters the Gut Microbiome in Women with Autoimmune Thyroiditis. Nutrients. 2024;16(5). [CrossRef]

- Ali H, Badshah J, Sami M, Ravuthar N, Abdul A, Pathan A, et al. A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW ON MANAGEMENT OF HASHIMOTO’S DISEASE USING DIETARY APPROACHES *Corresponding Author. Certified Journal │ Badshah et al World Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2024;13:475-89.

- Tuçe Ülker M, Gözde, Çolak A, Murat B. Evaluation of the effect of gluten-free diet and Mediterranean diet on autoimmune system in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis gluten-free diet, Hashimoto, Mediterranean diet. 2023.

- Abbott RD, Sadowski A, Alt AG. Efficacy of the Autoimmune Protocol Diet as Part of a Multi-disciplinary, Supported Lifestyle Intervention for Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Henjum S, Groufh-Jacobsen S, Aakre I, Gjengedal ELF, Langfjord MM, Heen E, et al. Thyroid function and urinary concentrations of iodine, selenium, and arsenic in vegans, lacto-ovo vegetarians and pescatarians. Eur J Nutr. 2023;62(8):3329-38. [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarzyk I, Nowak-Perlak M, Woźniak M. Promising Approaches in Plant-Based Therapies for Thyroid Cancer: An Overview of In Vitro, In Vivo, and Clinical Trial Studies. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(8). [CrossRef]

- Muhammad H, Reeves S, Ishaq S, Mayberry J, Jeanes YM. Adherence to a Gluten Free Diet Is Associated with Receiving Gluten Free Foods on Prescription and Understanding Food Labelling. Nutrients. 2017;9. [CrossRef]

- de Andreis FB, Schiepatti A, Gibiino G, Fabbri C, Baiardi P, Biagi F. Is it time to rethink the burden of non-coeliac gluten sensitivity? A systematic review. Minerva Gastroenterology: Edizioni Minerva Medica; 2022. p. 442-9. [CrossRef]

- Norwood FB. Perceived impact of information signals on opinions about gluten-free diets: PLOS ONE; 2021 2021/4//.

- Bascuñán KA, Orosteguí C, Rodríguez JM, Roncoroni L, Doneda L, Elli L, et al. Heavy Metal and Rice in Gluten-Free Diets: Are They a Risk? Nutrients. 2023;15(13). [CrossRef]

- Szczuko M, Syrenicz A, Szymkowiak K, Przybylska A, Szczuko U, Pobłocki J, et al. Doubtful Justification of the Gluten-Free Diet in the Course of Hashimoto’s Disease. Nutrients: MDPI; 2022. [CrossRef]

- Araújo EMQ, Ramos HE, Trevisani VFM. Commentary: Effect of gluten-free diet on autoimmune thyroiditis progression in patients with no symptoms or histology of celiac disease: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Meneghini V, Tebar WR, Santos IS, Janovsky C, de Almeida-Pititto B, Birck MG, et al. Potential Determinants of Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies and Mortality Risk: Results From the ELSA-Brasil Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2024;109(2):e698-e710. [CrossRef]

- Lebwohl B, Cao Y, Zong G, Hu FB, Green PHR, Neugut AI, et al. Long term gluten consumption in adults without celiac disease and risk of coronary heart disease: prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2017;357:j1892-j. [CrossRef]

- Ruscio M, Guard G, Piedrahita G, D’Adamo CR. The Relationship between Gastrointestinal Health, Micronutrient Concentrations, and Autoimmunity: A Focus on the Thyroid. Nutrients. 2022;14(17):3572.

- Ihnatowicz P, Wątor P, Drywień ME. The importance of gluten exclusion in the management of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine. 2021;28(4):558-68. [CrossRef]

- Durá-Travé T, Gallinas-Victoriano F. Autoimmune Thyroiditis and Vitamin D. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024;25(6):3154.

- Sharma N, Bhatia S, Chunduri V, Kaur S, Sharma S, Kapoor P, et al. Pathogenesis of Celiac Disease and Other Gluten Related Disorders in Wheat and Strategies for Mitigating Them. Front Nutr. 2020;7:6. [CrossRef]

- Jiang W, Lu G, Gao D, Lv Z, Li D. The relationships between the gut microbiota and its metabolites with thyroid diseases. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2022;13:943408-. [CrossRef]

- Stramazzo I, Capriello S, Filardo S, Centanni M, Virili C. Microbiota and Thyroid Disease: An Updated Systematic Review. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2023;1370:125-44.

- Fenneman AC, Rampanelli E, Yin YS, Ames J, Blaser MJ, Fliers E, et al. Gut microbiota and metabolites in the pathogenesis of endocrine disease. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2020;48(3):915-31. [CrossRef]

- Cayres LCdF, de Salis LVV, Rodrigues GSP, Lengert AvH, Biondi APC, Sargentini LDB, et al. Detection of Alterations in the Gut Microbiota and Intestinal Permeability in Patients With Hashimoto Thyroiditis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2021;12.

- Köhling HL, Plummer SF, Marchesi JR, Davidge KS, Ludgate M. The microbiota and autoimmunity: Their role in thyroid autoimmune diseases. Clinical Immunology. 2017;183:63-74.

- Liu J, Qin X, Lin B, Cui J, Liao J, Zhang F, et al. Analysis of gut microbiota diversity in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients. BMC Microbiology. 2022;22(1). [CrossRef]

- Mori K, Nakagawa Y, Ozaki H. Does the gut microbiota trigger Hashimoto’s thyroiditis? Discovery medicine. 2012;14(78):321-6.

- Xiong Y, Zhu X, Luo Q. Causal relationship between gut microbiota and autoimmune thyroiditis: A mendelian study. Heliyon. 2024;10(3):e25652-e. [CrossRef]

- Zhao F, Feng J, Li J, Zhao L, Liu Y, Chen H, et al. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis Patients. Thyroid : official journal of the American Thyroid Association. 2018;28(2):175-86. [CrossRef]

- Du HX, Yue SY, Niu D, Liu C, Zhang LG, Chen J, et al. Gut Microflora Modulates Th17/Treg Cell Differentiation in Experimental Autoimmune Prostatitis via the Short-Chain Fatty Acid Propionate. Front Immunol. 2022;13:915218. [CrossRef]

- Fenneman AC, Boulund U, Collard D, Galenkamp H, Zwinderman AH, van den Born BH, et al. Comparative Analysis of Taxonomic and Functional Gut Microbiota Profiles in Relation to Seroconversion of Thyroid Peroxidase Antibodies in Euthyroid Participants. Thyroid. 2024;34(1):101-11. [CrossRef]

| P = Adults and older people diagnosed with Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis and non-celiac disease |

| I = Gluten-free diet |

| C = Any gluten dietary intervention; no dietary intervention; placebo (As long as all of them contain gluten) |

| O = Primary outcomes: serum levels of Thyroid hormones (fT3, fT4); TSH; Anti-thyroid antibodies (Anti-TPO and Anti-Tg). Secondary outcomes: serum levels of CRP and Vitamin D; adverse effects; anthropometric measurements (body weight, BMI); diet adherence; and health-related quality of life. |

| S = Randomized controlled trial, including crossover trials |

| ID | Authors | Year | Country | n | Study Design | Sex | Age means (SD or CI) | Celiac disease exclusion | Follow-up (months) | Interventions Gluten free diet /Control group |

Outcomes | Declaration of interest | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT06249074 |

Rodziewicz L, Szewczyk D, Bryl E |

2024 |

Poland |

28 |

RCT, double-blind study |

Women |

34.6 (6.3) GG; 36.6 (7.3) PG |

Patient was tested for CD: EmA, IgA tTG, total IgA, IgG AGA. |

1 |

Rice starch capsules: placebo + GFD |

Gluten (gastrosoluble capsules: 3 cap/2g/day) + GFD |

TSH, T3, T4, anti-TPO, anti-Tg, CRP |

No conflict |

| No Information |

Poblocki J et al. |

2021 |

Poland |

62 |

RCT |

Women |

36.64 (33.66-39.63) GFD; 37.07 (33.83-40.31) CG |

Patient was tested for CD: IgA-class antibodies against tTg and total IgA. If necessary: gastroscopy and duodenal biopsy |

3 |

All participants received a sample GDF menu (≤20mg of gluten per 1kg natural and processed products) |

Did not undergo any modification. They consumed gluten before and during the study. |

TSH, T3, T4, anti-TPO, anti-Tg, body weight, BMI |

No conflict |

| NCT05949671 |

Ulker M et al. |

2023 |

Turkey |

20 |

RCT, single-blind study |

Women |

39.05 (7.52) |

No symptoms of CD and no diagnosis |

3 |

All participants received a weekly diet according to individual requirements and daily energy needs. |

Did not receive any special dietary intervention. |

TSH, T3, T4, anti-TPO, anti-Tg, body weight, BMI |

No conflict |

| No Information |

Lagana M; Piticchio T et al. |

2025 |

Italy |

30 (20F; 10M) |

RCT, single-blind study |

Men/women |

43,25* (11,858**) GFD; 42,25* (12,434**) FD. |

No diagnosis nor symptoms of CD |

3 |

Patients received information according to individual recommendation by a registered dietitian. |

No change in the subjects’ dietary habits. |

TSH, T4, anti-TPO, anti-Tg, |

No conflict |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).