Submitted:

08 November 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

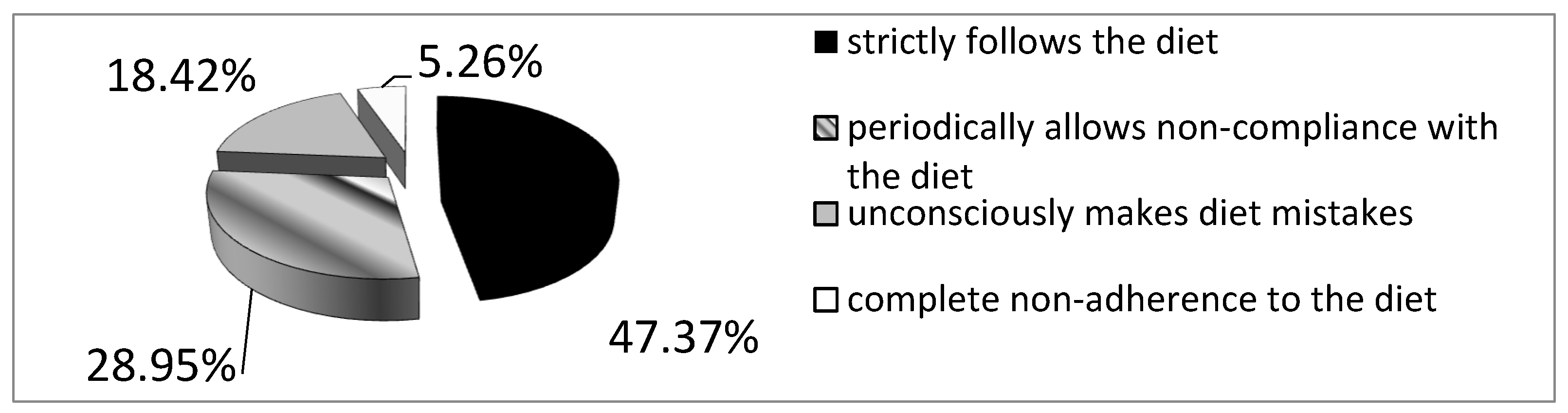

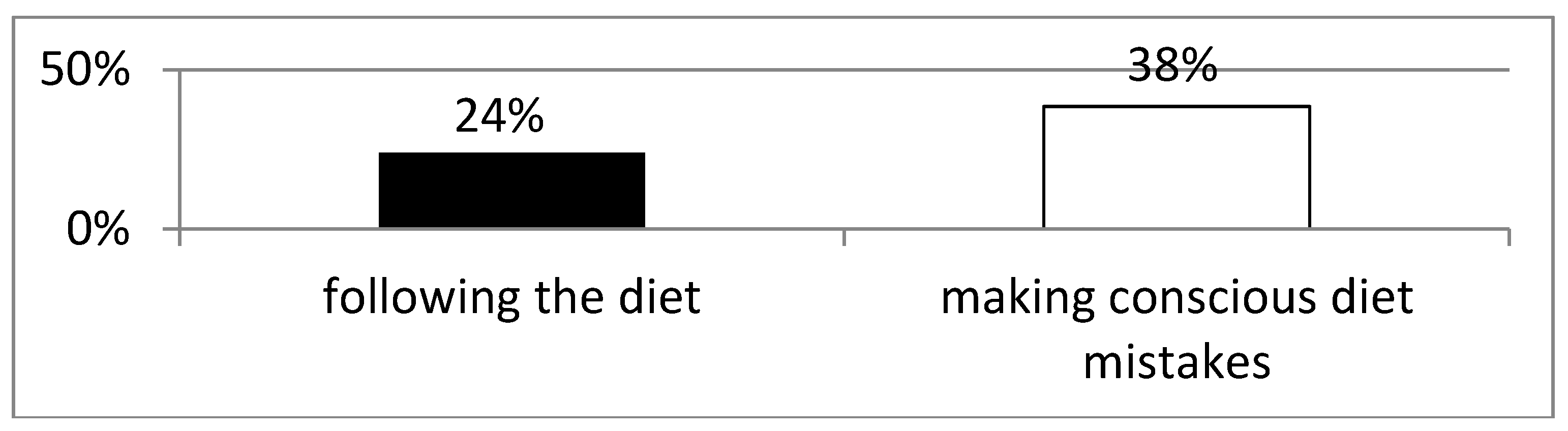

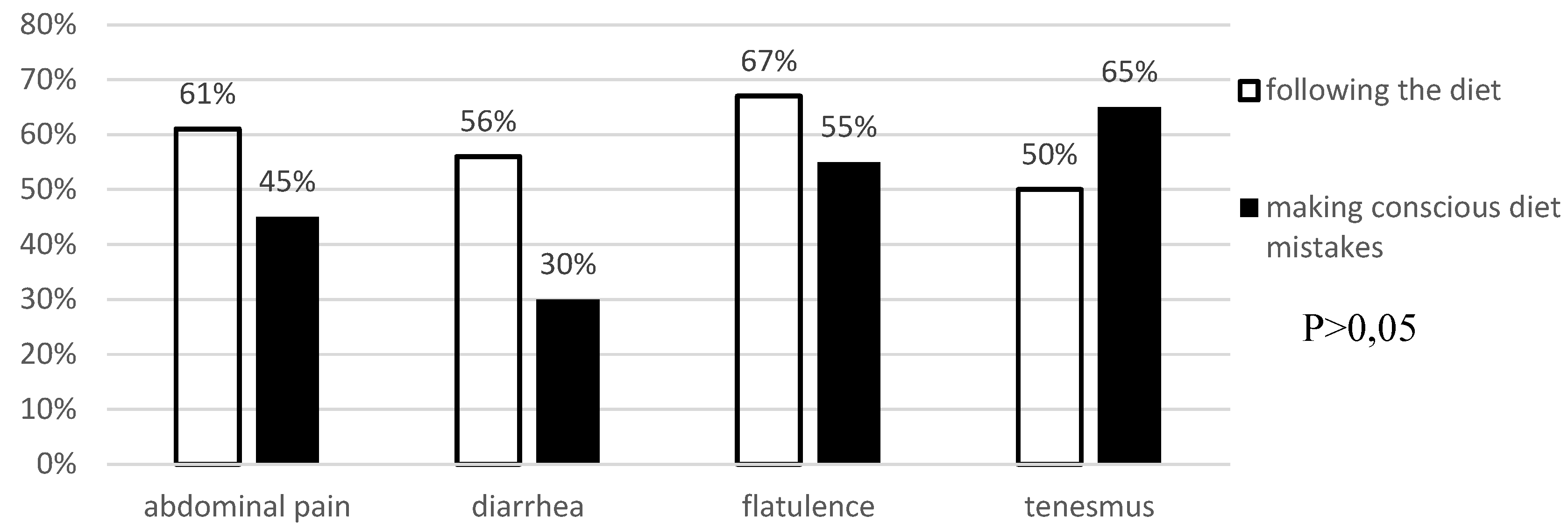

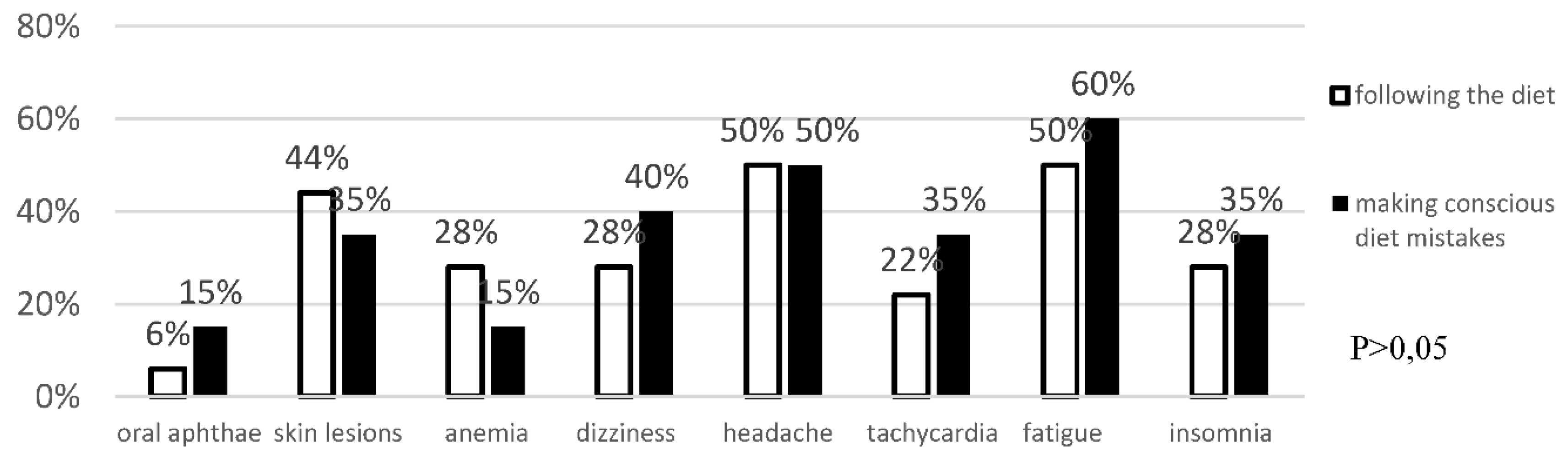

Background: Celiac disease is an autoimmune disease that results from the interaction of genetic, immune and environmental factors. According to 2020 ESPGHAN guidelines, an elimination diet (i.e. excluding products that may contain gluten) is the basic method of treating celiac disease. Following a gluten-free diet is extremely problematic and patients often make unconscious deviations from the diet. Objective: The aim of the study was to asses the frequency of conscious diet mistakes and unconscious deviations from the gluten-free diet in a group of patients with long-standing celiac disease and their impact on the frequency of typical and atypical symptoms. Methods: The study included 38 patients, 30 women and 8 men with a verified diagnosis of celiac disease. The effectiveness of the gluten-free diet was assessed in all participants. Blood was collected to determine IgA anti tissue transglutaminase II antibodies and IgG antibodies against deamidated gliadin peptides by ELISA. All survey participants provided data concerning current gastrointestinal and systemic symptoms, bowel habits, comorbidities, dietary habits, physical activity and socioeconomic conditions. Results: 25 patients (65.78%) declared strict adherence to the gluten-free diet. However, in this group, 7 (18.4%) patients had significantly increased levels of anti-tTG antibodies (mean 82.3 RU/ml ±78.9 SD at N<20 RU/ml). Among the patients who consciously made diet mistakes, 6 (46.2%) demonstrated increased levels of anti-tTG antibodies. The analysis did not reveal any difference between the frequency of intestinal and extraintestinal symptoms in patients making diet mistakes and following the gluten-free diet. Conclusions: More than half of celiac patients unconsciously or consciously make diet mistakes, which indicates an urgent need to increase their education about the diet. Regardless of whether the gluten-free diet is followed, both typical and atypical symptoms of the disease have been observed among celiac patients.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Treatment of Celiac Disease

2. Purpose of the Study

3. Aim

- Assessment of the frequency of conscious diet mistakes in a group of patients with long-standing celiac disease.

- Assessment of the frequency of unconscious deviations from the gluten-free diet in patients with celiac disease.

- Assessment of the impact of deviations from the gluten-free diet on the frequency of typical and atypical symptoms

4. Material and Methods

Study and Control Groups

Antibody Concentration Among Patients Diagnosed with Celiac Disease

Survey Study

Statistical Analysis

5. Results

Evaluation of the Effectiveness of the Gluten-Free Diet Adherence

Analysis of Anti-Tissue Transglutaminase Antibody Levels and Their Impact on Reported Symptoms

6. Discussion

7. Summary

8. Conclusions

- More than half of celiac patients unconsciously or consciously make diet mistakes, which indicates an urgent need to increase their education about the diet.

- Regardless of whether the gluten-free diet is followed, both typical and atypical symptoms of the disease have been observed among celiac patients.

References

- Garampazzi, A.; Rapa, A.; Mura, S.; Capelli, A.; Valori, A.; Boldorini, R.; Oderda, G. Clinical Pattern of Celiac Disease Is Still Changing. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2007, 45, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinler, G.; Atalay, E.; Kalaycı, A.G. Celiac disease in 87 children with typical and atypical symptoms in Black Sea region of Turkey. World J. Pediatr. 2009, 5, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottaro, G.; Failla, P.; Rotolo, N.; Sanfilippo, G.; Azzaro, F.; Spina, M.; Patane, R. Changes in coeliac disease behaviour over the years. Acta Paediatr. 1993, 82, 566–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner-Hogg, K.B.; Selby, W.S.; Loblay, R.H. Dietary Analysis in Symptomatic Patients with Coeliac Disease on a Gluten-Free Diet: the Role of Trace Amounts of Gluten and Non-Gluten Food Intolerances. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1999, 34, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalayci, A.G.; Kansu, A.; Girgin, N.; Kucuk, O.; Aras, G. Bone Mineral Density and Importance of a Gluten-Free Diet in Patients With Celiac Disease in Childhood. Pediatrics 2001, 108, e89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautalen, C.; González, D.; Mazure, R.; Vázquez, H.; Lorenzetti, M.P.; Maurino, E.; Niveloni, S.; Pedreira, S.; Smecuol, E.; A Boerr, L.; et al. Effect of treatment on bone mass, mineral metabolism, and body composition in untreated celiac disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997, 92, 313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, J.C.; Gonzalez, D.; Mautalen, C.; Mazure, R.; Pedreira, S.; Vazquez, H.; Smecuol, E.; Siccardi, A.; Cataldi, M.; Niveloni, S.; et al. Long-term effect of gluten restriction on bone mineral density of patients with coeliac disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 11, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciacci, C.; Maurelli, L.; Klain, M.; Savino, G.; Salvatore, M.; Mazzacca, G.; Cirillo, M. Effects of dietary treatment on bone mineral density in adults with celiac disease: factors predicting response. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 92, 992–996. [Google Scholar]

- Zanchetta, M.B.; Longobardi, V.; Costa, F.; Longarini, G.; Mazure, R.M.; Moreno, M.L.; Vázquez, H.; Silveira, F.; Niveloni, S.; Smecuol, E.; et al. Impaired Bone Microarchitecture Improves After One Year On Gluten-Free Diet: A Prospective Longitudinal HRpQCT Study in Women With Celiac Disease. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2016, 32, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catal, F., et al., The hematologic manifestations of pediatric celiac disease at the time of diagnosis and efficiency of gluten-free diet. Turk J Med Sci, 2015. 45(3): p. 663-7.

- Repo, M.; Lindfors, K.; Mäki, M.; Huhtala, H.; Laurila, K.; Lähdeaho, M.; Saavalainen, P.; Kaukinen, K.; Kurppa, K. Anemia and Iron Deficiency in Children With Potential Celiac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schøsler, L.; Christensen, L.A.; Hvas, C.L. Symptoms and findings in adult-onset celiac disease in a historical Danish patient cohort. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 51, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.S.; Minaya, M.T.; Cheng, J.; Connor, B.A.; Lewis, S.K.; Green, P.H.R. Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial of Rifaximin for Persistent Symptoms in Patients with Celiac Disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 2939–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucci, P., et al., Oral aphthous ulcers and dental enamel defects in children with coeliac disease. Acta Paediatr, 2006. 95(2): p. 203-7.

- Costacurta, M.; Maturo, P.; Bartolino, M.; Docimo, R. Oral manifestations of coeliac disease: A clinical-statistic study. Oral Implantol (Rome). 2010, 3, 12–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avşar, A.; Kalayci, A.G. The presence and distribution of dental enamel defects and caries in children with celiac disease. Turk J Pediatr. 2008, 50, 45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cantekin, K., D. Arslan, and E. Delikan, Presence and distribution of dental enamel defects, recurrent aphthous lesions and dental caries in children with celiac disease. Pak J Med Sci, 2015. 31(3): p. 606-9.

- Acar, S.; Yetkıner, A.A.; Ersın, N.; Oncag, O.; Aydogdu, S.; Arıkan, C. Oral Findings and Salivary Parameters in Children with Celiac Disease: A Preliminary Study. Med Princ. Pr. 2012, 21, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, D.; Fortunato, F.; Tafuri, S.; A Germinario, C.; Prato, R. Reproductive life disorders in Italian celiac women. A case-control study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Arora, S.; Lal, S.; Strand, T.A.; Makharia, G.K. Celiac Disease in Women With Infertility: A meta-Analysis. J Clin. Gastroenterol 2016, 50, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasa, J.S.; Zubiaurre, I.; Soifer, L.O. RISK OF INFERTILITY IN PATIENTS WITH CELIAC DISEASE: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Arq. de Gastroenterol. 2014, 51, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstock, L.B.; Walters, A.S.; Mullin, G.E.; Duntley, S.P. Celiac Disease Is Associated with Restless Legs Syndrome. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2010, 55, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchanda, S.; Davies, C.R.; Picchietti, D. Celiac disease as a possible cause for low serum ferritin in patients with restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 763–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, L.; Hernández-Lahoz, C.; Lauret, E.; Rodriguez-Peláez, M.; Soucek, M.; Ciccocioppo, R.; Kruzliak, P. Gluten ataxia is better classified as non-celiac gluten sensitivity than as celiac disease: a comparative clinical study. Immunol. Res. 2016, 64, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Işikay, S.; Hizli, .; Çoşkun, S.; Yilmaz, K. INCREASED TISSUE TRANSGLUTAMINASE LEVELS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH INCREASED EPILEPTIFORM ACTIVITY IN ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAPHY AMONG PATIENTS WITH CELIAC DISEASE. Arq. de Gastroenterol. 2015, 52, 272–277, https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-28032015000400005. [CrossRef]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.R.; Mearin, M.L.; Phillips, A.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Giersiepen, K.; Branski, D.; Catassi, C.; et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 54, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.; Kurppa, K.; Mearin, M.L.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lähdeaho, M.-L.; Mäki, M.; Laurila, K.; Huhtala, H.; Kaukinen, K. Small- bowel mucosal changes and antibody responses after low- and moderate-dose gluten challenge in celiac disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011, 11, 129–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catassi, C.; Fabiani, E.; Iacono, G.; D'Agate, C.; Francavilla, R.; Biagi, F.; Volta, U.; Accomando, S.; Picarelli, A.; De Vitis, I.; et al. A prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to establish a safe gluten threshold for patients with celiac disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 85, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruins, M.J. The Clinical Response to Gluten Challenge: A Review of the Literature. Nutrients 2013, 5, 4614–4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akobeng, A.K.; Thomas, A.G. Systematic review: tolerable amount of gluten for people with coeliac disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 27, 1044–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibert, A.; Espadaler, M.; Canela, M.A.; Sánchez, A.; Vaqué, C.; Rafecas, M. Consumption of gluten-free products: should the threshold value for trace amounts of gluten be at 20, 100 or 200???p.p.m.? Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 18, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanini, B.; Marullo, M.; Villanacci, V.; Salemme, M.; Lanzarotto, F.; Ricci, C.; Lanzini, A. Persistent Intraepithelial Lymphocytosis in Celiac Patients Adhering to Gluten-Free Diet Is Not Abolished Despite a Gluten Contamination Elimination Diet. Nutrients 2016, 8, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzini, A.; Lanzarotto, F.; Villanacci, V.; Mora, A.; Bertolazzi, S.; Turini, D.; Carella, G.; Malagoli, A.; Ferrante, G.; Cesana, B.M.; et al. Complete recovery of intestinal mucosa occurs very rarely in adult coeliac patients despite adherence to gluten-free diet. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tursi, A.; Brandimarte, G.; Giorgetti, G.; Elisei, W.; Inchingolo, C.; Monardo, E.; Aiello, F. Endoscopic and histological findings in the duodenum of adults with celiac disease before and after changing to a gluten-free diet: a 2-year prospective study. Endoscopy 2006, 38, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniewski, W.; Wojtasik, A.; Kunachowicz, H. [Gluten content in special dietary use gluten-free products and other food products]. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2010, 61, 51–55. [Google Scholar]

- BA, C., Problemy z rozróżnianiem żywności bezglutenowej. 2009, Pediatria Współczesna. Gastroenterologia, Hepatologia i Żywienie Dziecka. p. 117-122.

- Wojtasik, W.D., H. Kunachowicz, Zawartość glutenu (gliadyny) w wybranych produktach spożywczych. Bromat. Chem. Toksykol., 2010. XLIII(3): p. 362-371.

- Koerner, T.B., et al., Gluten contamination of naturally gluten-free flours and starches used by Canadians with celiac disease. Food Addit Contam Part A Chem Anal Control Expo Risk Assess, 2013. 30(12): p. 2017-21.

- Thompson, T.; Lee, A.R.; Grace, T. Gluten Contamination of Grains, Seeds, and Flours in the United States: A Pilot Study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 937–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.; Mcgough, N.; Urwin, H. Catering Gluten-Free When Simultaneously Using Wheat Flour. J. Food Prot. 2016, 79, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colgrave, M.L.; Goswami, H.; Byrne, K.; Blundell, M.; Howitt, C.A.; Tanner, G.J. Proteomic Profiling of 16 Cereal Grains and the Application of Targeted Proteomics To Detect Wheat Contamination. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 2659–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibert, A.; Kruizinga, A.G.; Neuhold, S.; Houben, G.F.; A Canela, M.; Fasano, A.; Catassi, C. Might gluten traces in wheat substitutes pose a risk in patients with celiac disease? A population-based probabilistic approach to risk estimation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Vieille, S., et al., Estimated levels of gluten incidentally present in a Canadian gluten-free diet. Nutrients, 2014. 6(2): p. 881-96.

- Lee, H.J.; Anderson, Z.; Ryu, D. Gluten Contamination in Foods Labeled as “Gluten Free” in the United States. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 1830–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, G.M.; Pereira, M.; Williams, K.M. Gluten detection in foods available in the United States – A market survey. Food Chem. 2015, 169, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, J.A.; Gra, L.A.; Rigaux, L.; Walker, J.R.; Duerksen, D.R. Symptomatic suspected gluten exposure is common among patients with coeliac disease on a gluten-free diet. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma, E.; Roubani, A.; Kolia, E.; Panayiotou, J.; Zellos, A.; Syriopoulou, V.P. Dietary compliance and life style of children with coeliac disease. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2010, 23, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.L.; Orfila, C. Impact of coeliac disease on dietary habits and quality of life. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvester, J.A.; Weiten, D.; Graff, L.A.; Walker, J.R.; Duerksen, D.R. Is it gluten-free? Relationship between self-reported gluten-free diet adherence and knowledge of gluten content of foods. Nutrition 2016, 32, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villafuerte-Galvez, J.; Vanga, R.R.; Dennis, M.; Hansen, J.; Leffler, D.A.; Kelly, C.P.; Mukherjee, R. Factors governing long-term adherence to a gluten-free diet in adult patients with coeliac disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 753–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarkadas, M.; Dubois, S.; MacIsaac, K.; Cantin, I.; Rashid, M.; Roberts, K.C.; La Vieille, S.; Godefroy, S.; Pulido, O.M. Living with coeliac disease and a gluten-free diet: a Canadian perspective. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 26, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvester, J.A., et al., Living gluten-free: adherence, knowledge, lifestyle adaptations and feelings towards a gluten-free diet. J Hum Nutr Diet, 2016. 29(3): p. 374-82.

- Sdepanian, V.L., M.B. de Morais, and U. Fagundes-Neto, [Celiac disease: evaluation of compliance to gluten-free diet and knowledge of disease in patients registered at the Brazilian Celiac Association (ACA)]. Arq Gastroenterol, 2001. 38(4): p. 232-9.

- Hopman, E.G.; Koopman, H.M.; Wit, J.M.; Mearin, M.L. Dietary compliance and health-related quality of life in patients with coeliac disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 21, 1056–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häuser, W.; Gold, J.; Stein, J.; Caspary, W.F.; Stallmach, A. Health-related quality of life in adult coeliac disease in Germany: results of a national survey. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2006, 18, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, J.C.; Kumar, P.; Dutta, A.K.; Basu, S.; Kumar, A. Assessment of dietary compliance to Gluten Free Diet and psychosocial problems in Indian children with celiac disease. Indian J. Pediatr. 2010, 77, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.; Cranney, A.; Zarkadas, M.; Graham, I.D.; Switzer, C.; Case, S.; Molloy, M.; Warren, R.E.; Burrows, V.; Butzner, J.D. Celiac Disease: Evaluation of the Diagnosis and Dietary Compliance in Canadian Children. Pediatrics 2005, 116, e754–e759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, H.; Lewis, T.; Violato, M.; Peters, M. The affordability and obtainability of gluten-free foods for adults with coeliac disease following their withdrawal on prescription in England: A qualitative study. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2024, 37, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurppa, K.; Lauronen, O.; Collin, P.; Ukkola, A.; Laurila, K.; Huhtala, H.; Mäki, M.; Kaukinen, K. Factors Associated with Dietary Adherence in Celiac Disease: A Nationwide Study. Digestion 2012, 86, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, C.; Myléus, A.; Norström, F.; Hammarroth, S.; Högberg, L.; Lagerqvist, C.; Rosén, A.; Sandström, O.; Stenhammar, L.; Ivarsson, A.; et al. High Adherence to a Gluten-Free Diet in Adolescents With Screening-Detected Celiac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, S.; Chamorro, M.E.; Ortíz, J.; Carpinelli, M.M.; Giménez, V.; Langjahr, P. [Anti-transglutaminase antibody in adults with celiac disease and their relation to the presence and duration of gluten-free diet]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2018, 38, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gładyś, K.; Dardzińska, J.; Guzek, M.; Adrych, K.; Małgorzewicz, S. Celiac Dietary Adherence Test and Standardized Dietician Evaluation in Assessment of Adherence to a Gluten-Free Diet in Patients with Celiac Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tursi, A.; Brandimarte, G.; Giorgetti, G.M. Lack of Usefulness of Anti-Transglutaminase Antibodies in Assessing Histologic Recovery After Gluten-Free Diet in Celiac Disease. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2003, 37, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürgin-Wolff, A.; Dahlbom, I.; Hadziselimovic, F.; Petersson, C.J. Antibodies against human tissue transglutaminase and endomysium in diagnosing and monitoring coeliac disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2002, 37, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, K., et al., Reliability of antitransglutaminase antibodies as predictors of gluten-free diet compliance in adult celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol, 2003. 98(5): p. 1079-87.

- Matysiak-Budnik, T.; Malamut, G.; de Serre, N.P.-M.; Grosdidier, E.; Seguier, S.; Brousse, N.; Caillat-Zucman, S.; Cerf-Bensussan, N.; Schmitz, J.; Cellier, C. Long-term follow-up of 61 coeliac patients diagnosed in childhood: evolution toward latency is possible on a normal diet. Gut 2007, 56, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukinen, K., et al., IgA-class transglutaminase antibodies in evaluating the efficacy of gluten-free diet in coeliac disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2002. 14(3): p. 311-5.

- Bufler, P.; Heilig, G.; Ossiander, G.; Freudenberg, F.; Grote, V.; Koletzko, S. Diagnostic performance of three serologic tests in childhood celiac disease. Z. Fur Gastroenterol. 2015, 53, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannister, E.G. , et al., Can celiac serology alone be used as a marker of duodenal mucosal recovery in children with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet? Am J Gastroenterol, 2014. 109(9): p. 1478-83.

- Galli, G.; Carabotti, M.; Conti, L.; Scalamonti, S.; Annibale, B.; Lahner, E. Comparison of Clinical, Biochemical and Histological Features between Adult Celiac Patients with High and Low Anti-Transglutaminase IgA Titer at Diagnosis and Follow-Up. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.H., The Correlation Between Serum Anti-tissue Transglutaminase (Anti-tTG) Antibody Levels and Histological Severity of Celiac Disease in Adolescents and Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Cureus, 2023. 15(12): p. e51169.

- Selby, W.S., et al., Persistent mucosal abnormalities in coeliac disease are not related to the ingestion of trace amounts of gluten. Scand J Gastroenterol, 1999. 34(9): p. 909-14.

- Sugai, E.; Nachman, F.; Váquez, H.; González, A.; Andrenacci, P.; Czech, A.; Niveloni, S.; Mazure, R.; Smecuol, E.; Cabanne, A.; et al. Dynamics of celiac disease-specific serology after initiation of a gluten-free diet and use in the assessment of compliance with treatment. Dig. Liver Dis. 2010, 42, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leer, D.A.; Edwards George, J.B.; Dennis, M.; Cook, E.F.; Schuppan, D.; Kelly, C.P. A prospective comparative study of five measures of gluten-free diet adherence in adults with coeliac disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 26, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.M.; Weir, D.C.; DeGroote, M.; Mitchell, P.D.; Singh, P.; Silvester, J.A.; Leichtner, A.M.; Fasano, A. Value of IgA tTG in Predicting Mucosal Recovery in Children With Celiac Disease on a Gluten-Free Diet. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2017, 64, 286–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvester, J.A.; Kurada, S.; Szwajcer, A.; Kelly, C.P.; Leffler, D.A.; Duerksen, D.R. Tests for Serum Transglutaminase and Endomysial Antibodies Do Not Detect Most Patients With Celiac Disease and Persistent Villous Atrophy on Gluten-free Diets: a Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2017, 153, 689–701.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-Tapia, A.; Rahim, M.W.; See, J.A.; Lahr, B.D.; Wu, T.T.; Murray, J.A. Mucosal Recovery and Mortality in Adults With Celiac Disease After Treatment With a Gluten-Free Diet. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 105, 1412–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazario, E.; Lasa, J.; Schill, A.; Duarte, B.; Berardi, D.; Paz, S.; Muryan, A.; Zubiaurre, I. IgA Deficiency Is Not Systematically Ruled Out in Patients Undergoing Celiac Disease Testing. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2022, 67, 1238–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choung, R.S.; Rostamkolaei, S.K.; Ju, J.M.; Marietta, E.V.; Van Dyke, C.T.; Rajasekaran, J.; Jayaraman, V.; Wang, T.; Bei, K.; Rajasekaran, K.E.; et al. Synthetic Neoepitopes of the Transglutaminase–Deamidated Gliadin Complex as Biomarkers for Diagnosing and Monitoring Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 582–591.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Sánchez, A.D.; Tan, I.L.; Gonera-De Jong, B.C.; Visschedijk, M.C.; Jonkers, I.; Withoff, S. Molecular Biomarkers for Celiac Disease: Past, Present and Future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Pramanik, A.; Acharya, P.; Makharia, G.K. Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Celiac Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Carnicer, .; Garzón-Benavides, M.; Fombuena, B.; Segura, V.; García-Fernández, F.; Sobrino-Rodríguez, S.; Gómez-Izquierdo, L.; A Montes-Cano, M.; Rodríguez-Herrera, A.; Millán, R.; et al. Negative predictive value of the repeated absence of gluten immunogenic peptides in the urine of treated celiac patients in predicting mucosal healing: new proposals for follow-up in celiac disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1240–1251. [CrossRef]

- Bascuñán, K.A.; Vespa, M.C.; Araya, M. Celiac disease: understanding the gluten-free diet. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 56, 449–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samasca, G.; Sur, G.; Lupan, I.; Deleanu, D. Gluten-free diet and quality of life in celiac disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2014, 7, 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Balamtekin, N.; Aksoy, .; Baysoy, G.; Uslu, N.; Demir, H.; Köksal, G.; Saltık-Temizel, I.N.; Özen, H.; Gürakan, F.; Yüce, A. Is compliance with gluten-free diet sufficient? Diet composition of celiac patients. Turk J Pediatr. 2015, 57, 374–379.

- Churruca, I.; Miranda, J.; Lasa, A.; Bustamante, M.Á.; Larretxi, I.; Simon, E. Analysis of Body Composition and Food Habits of Spanish Celiac Women. Nutrients 2015, 7, 5515–5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautto, E.; Ivarsson, A.; Norström, F.; Högberg, L.; Carlsson, A.; Hörnell, A. Nutrient intake in adolescent girls and boys diagnosed with coeliac disease at an early age is mostly comparable to their non-coeliac contemporaries. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.H.Y.; Neal, B.; Trevena, H.; Crino, M.; Stuart-Smith, W.; Faulkner-Hogg, K.; Louie, J.C.Y.; Dunford, E. Are gluten-free foods healthier than non-gluten-free foods? An evaluation of supermarket products in Australia. Br. J. Nutr. 2015, 114, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, S.J.; Gibson, P.R. Nutritional inadequacies of the gluten-free diet in both recently-diagnosed and long-term patients with coeliac disease. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2013, 26, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J., et al., Nutritional differences between a gluten-free diet and a diet containing equivalent products with gluten. Plant Foods Hum Nutr, 2014. 69(2): p. 182-7.

- Vici, G.; Belli, L.; Biondi, M.; Polzonetti, V. Gluten free diet and nutrient deficiencies: A review. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 35, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Geisel, T.; Maresch, C.; Krieger, K.; Stein, J. Inadequate Nutrient Intake in Patients with Celiac Disease: Results from a German Dietary Survey. Digestion 2013, 87, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCulloch, K.; Rashid, M. Factors affecting adherence to a gluten-free diet in children with celiac disease. Paediatr. Child Heal. 2014, 19, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burden, M.; Mooney, P.D.; Blanshard, R.J.; White, W.L.; Cambray-Deakin, D.R.; Sanders, D.S. Cost and availability of gluten-free food in the UK: in store and online. Postgrad. Med J. 2015, 91, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Missbach, B.; Schwingshackl, L.; Billmann, A.; Mystek, A.; Hickelsberger, M.; Bauer, G.; König, J. Gluten-free food database: the nutritional quality and cost of packaged gluten-free foods. PeerJ 2015, 3, e1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leffler, D.; Schuppan, D.; Pallav, K.; Najarian, R.; Goldsmith, J.D.; Hansen, J.; Kabbani, T.; Dennis, M.; Kelly, C.P. Kinetics of the histological, serological and symptomatic responses to gluten challenge in adults with coeliac disease. Gut 2013, 62, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedoto, D.; Troncone, R.; Massitti, M.; Greco, L.; Auricchio, R. Adherence to Gluten-Free Diet in Coeliac Paediatric Patients Assessed through a Questionnaire Positively Influences Growth and Quality of Life. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsahoryi, N.A.; Ibrahim, M.O.; Alhaj, O.A. Adherence to the Gluten-Free Diet Role as a Mediating and Moderating of the Relationship between Food Insecurity and Health-Related Quality of Life in Adults with Celiac Disease: Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).