Submitted:

24 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Biocementation Pathways

2.1. Ureolysis

2.2. Ammonification of Amino Acids

2.3. Photosynthesis

2.4. Denitrification

2.5. Sulphate Reduction

2.6. Methanogenesis

3. Martian Resources and Environment

3.1. Martian Regolith Chemical Composition and Simulants

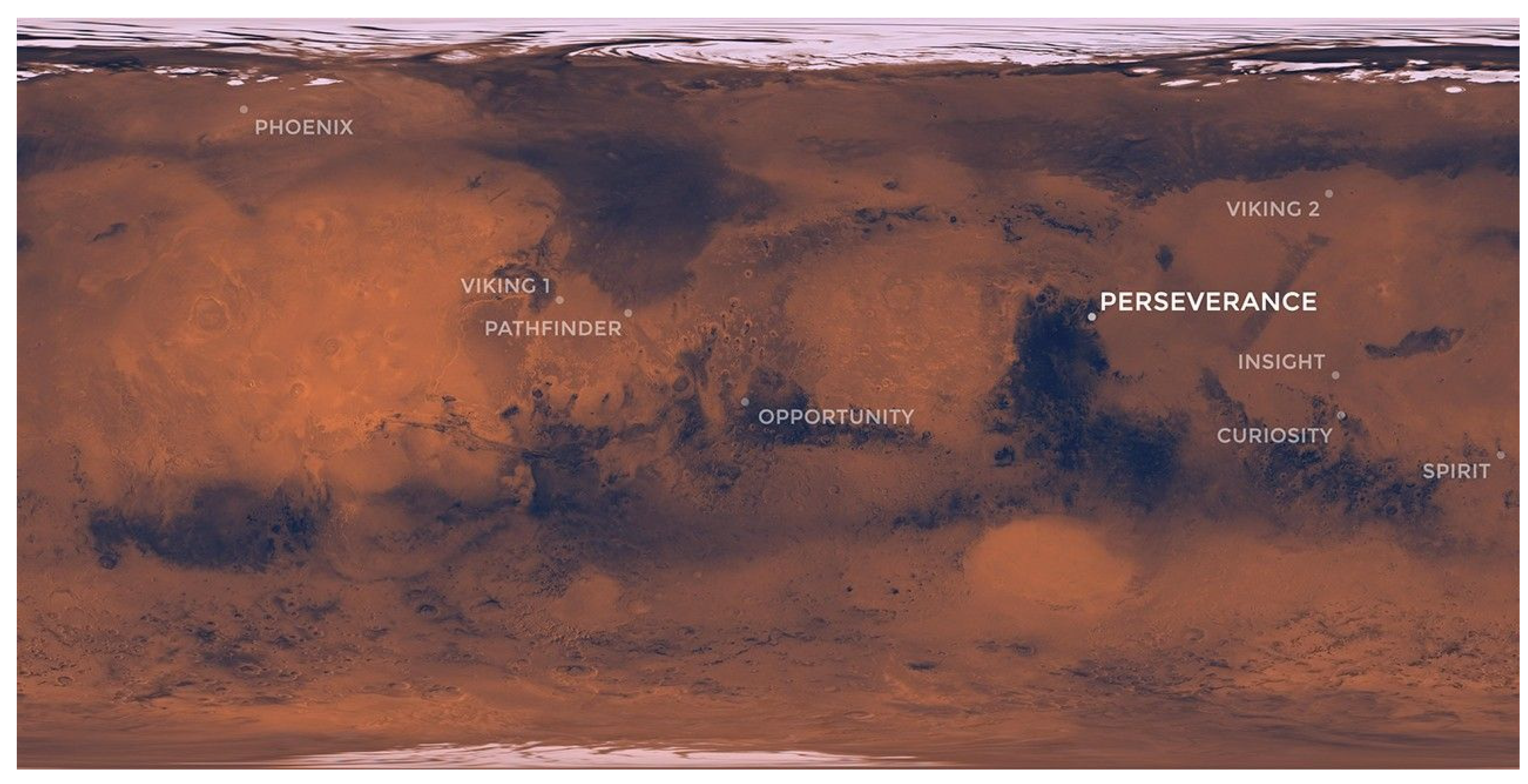

3.1.1. Martian Surface Minerology

3.1.2. Martian Regolith Simulants

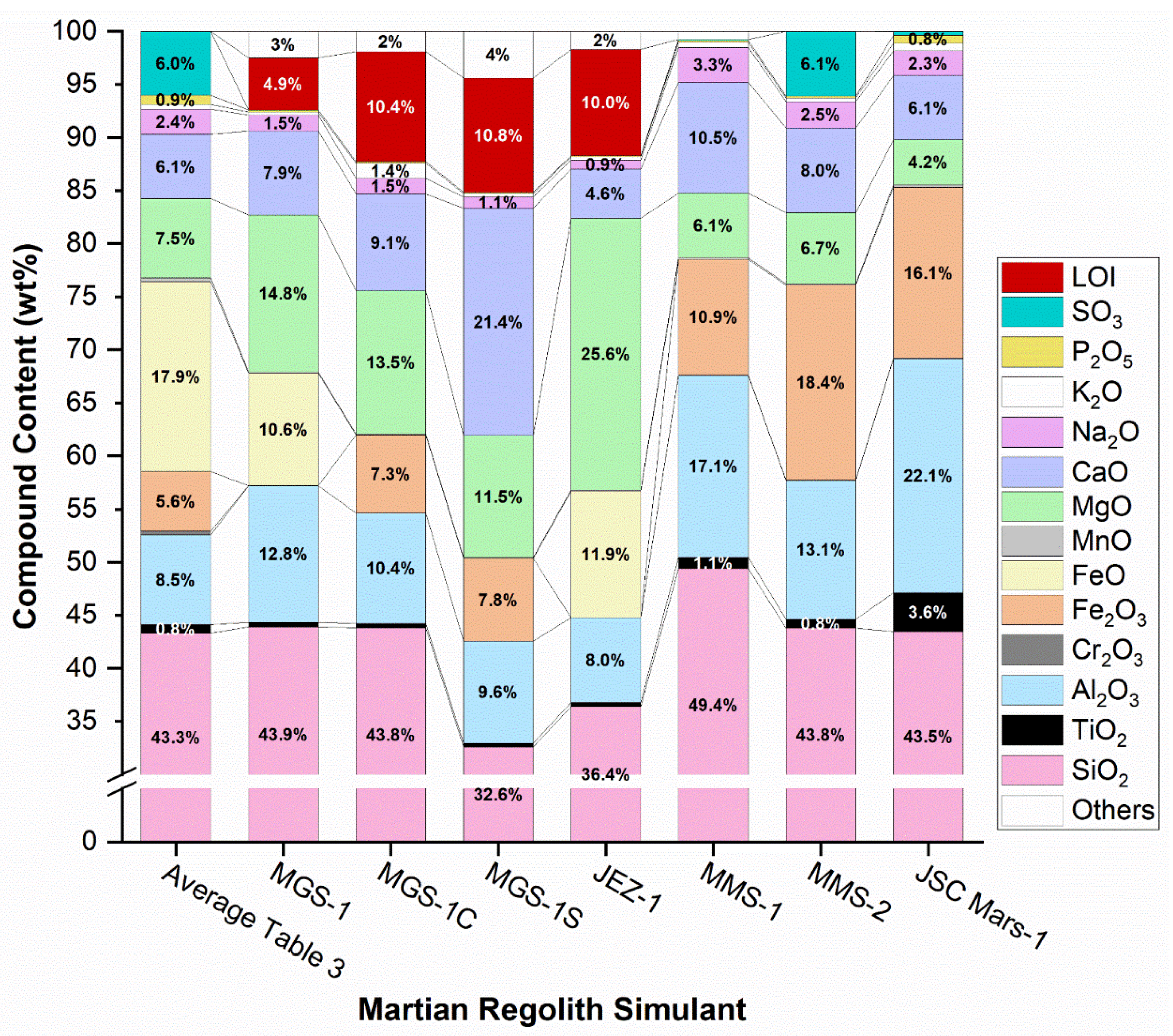

Simulants’ Chemical Composition

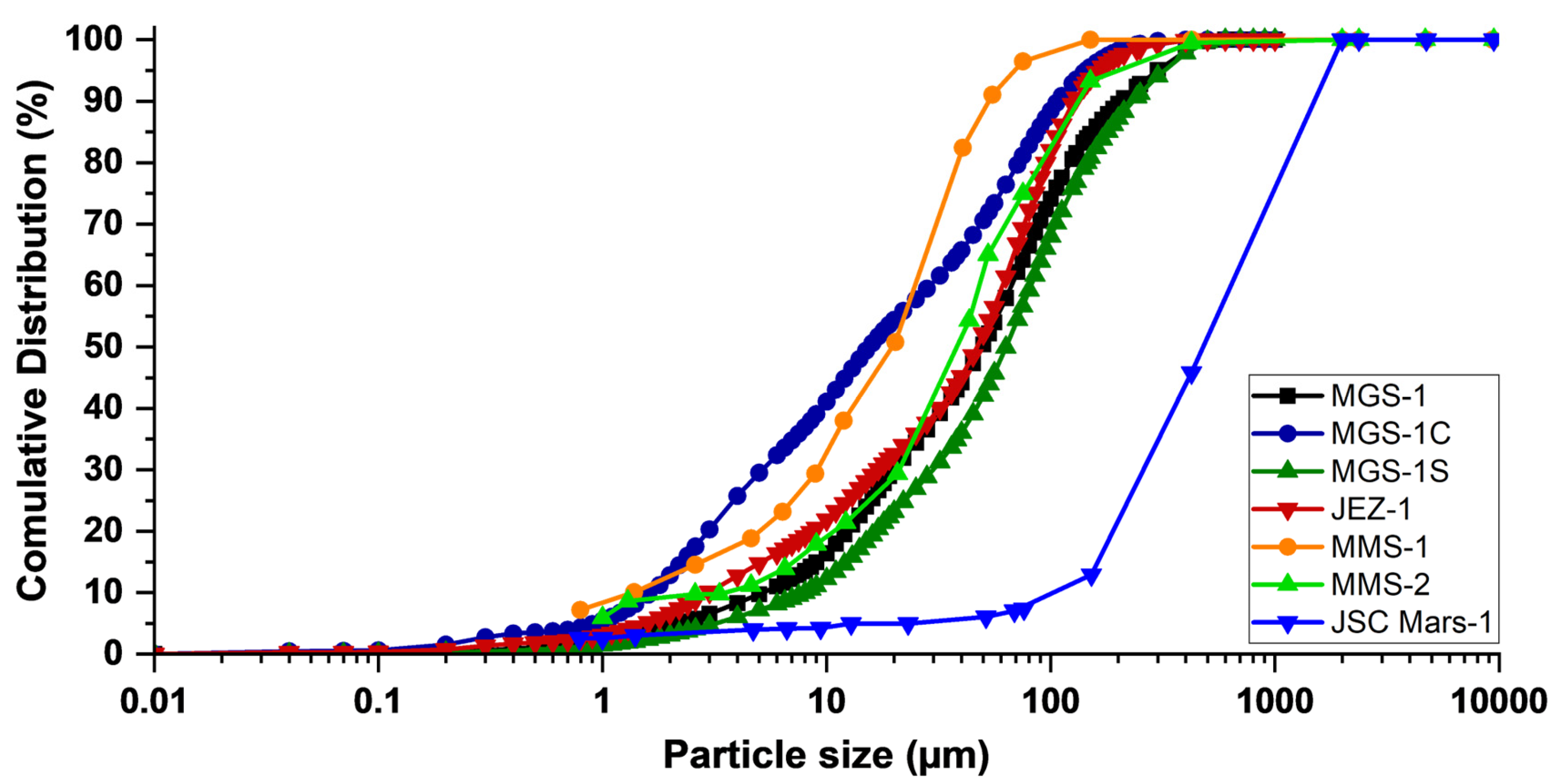

Particle Size Distribution

3.2. Water Availability

3.3. Martian Atmosphere

3.3.1. Gravity

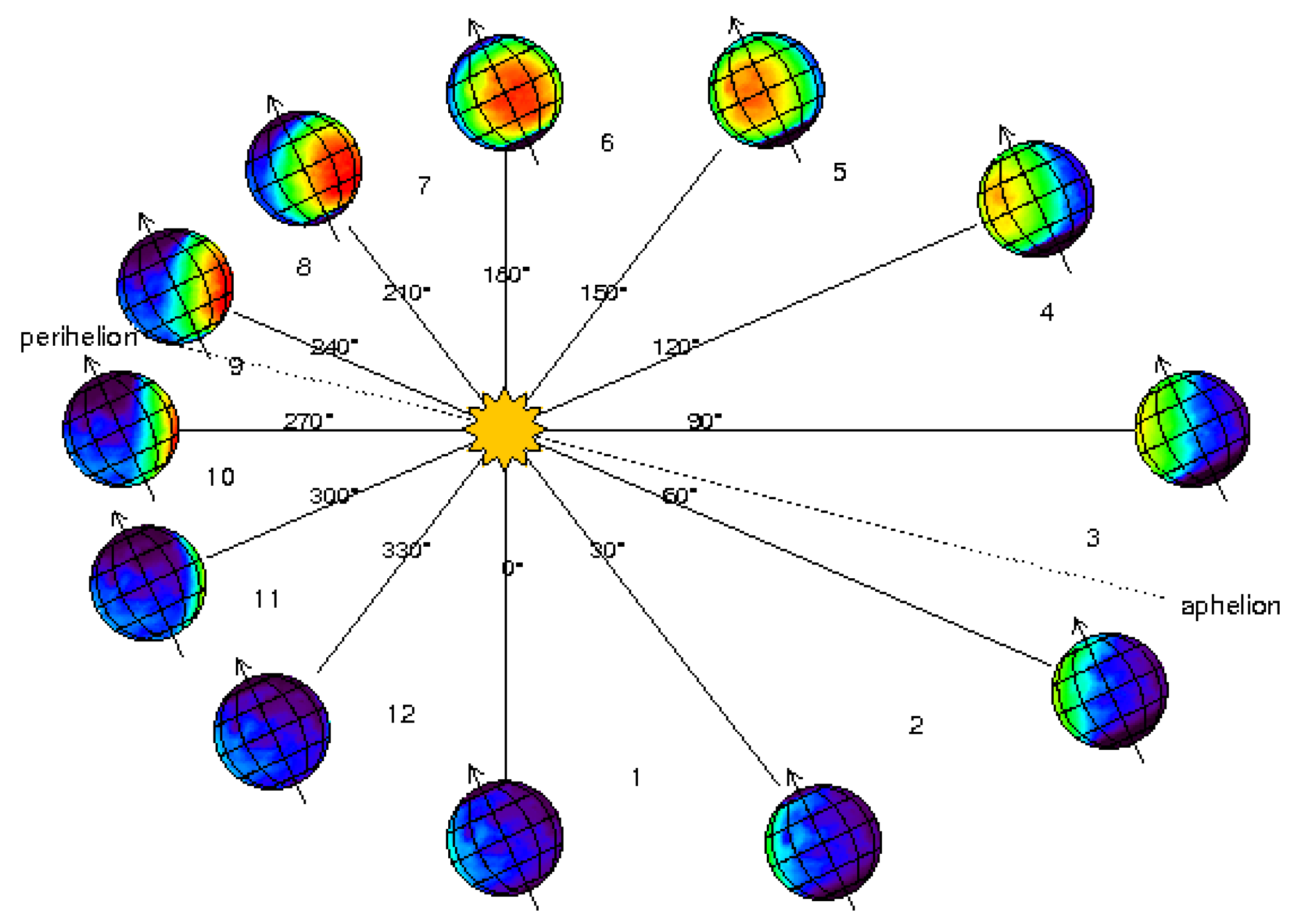

3.3.2. Extreme Temperature Fluctuations

3.3.3. High Radiation

3.3.4. Low Pressure

4. Biocementation on Mars

4.1. Recent Advances in MICP for Construction on Mars

4.2. Promising Biocementation Pathway and Approach

4.3. Road Map Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

5. Research Gaps and Future Directions

- Knowledge Gap: This refers to a fundamental lack of information or comprehensive understanding within the context of biocementation for Martian applications. The primary knowledge gap lies in the absence of an integrated, interdisciplinary overview. Biocementation inherently resides at the intersection of microbiology, materials science, and construction engineering. Even for Earth-based applications, a gap persists in effectively synthesising expertise across these disciplines. The challenge becomes even more complex in the Martian context, where additional considerations in the field of astrobiology, such as microbial survivability in extraterrestrial environments, must be addressed. Researchers with expertise in only one of these domains often find it difficult to fully account for the range of parameters that influence biocementation on Mars, such as the formulation of appropriate nutrient media for microbial viability, the effects of UV irradiation, extreme thermal fluctuations, or microgravity. This fragmented understanding impedes the design of holistic experimental campaigns that are necessary to systematically address the challenges unique to Martian biocementation.

- Theoretical Gap: The absence of robust underlying theories is primarily rooted in the interdisciplinary complexity of the problem as well as the existing knowledge gap. Biocementation encompasses a wide range of coupled processes, including microbial metabolism, geochemical precipitation, material behaviour, and structural performance, all of which must be reconsidered under the extreme and unprecedented environmental conditions of Mars. Existing theoretical models, which have been developed largely for Earth-based environments, fall short in addressing such extraterrestrial variables. They often neglect critical factors such as the influence of microgravity on microbial growth and biofilm formation, the altered thermodynamics and kinetics of carbonate precipitation at low pressures, and the long-term durability of biocemented structures exposed to Martian radiation and diurnal thermal variations.

- 3.

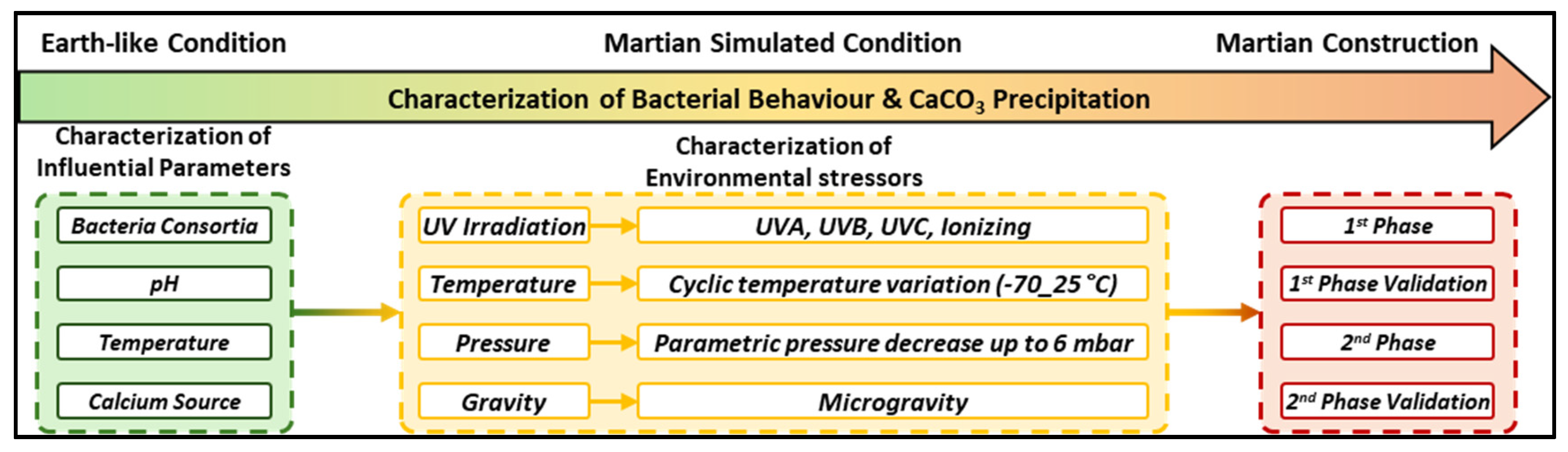

- Empirical Gap: This engages the absence of observed data or experimental validation, particularly in the context of applying biocementation to extraterrestrial environments. Given the emerging nature of this field, such a gap is expected. However, the empirical gap is further exacerbated by the previously discussed knowledge and theoretical gaps, which hinder the design and implementation of meaningful experiments. The lack of interdisciplinary understanding and robust theoretical models limits the ability to formulate relevant hypotheses and identify critical variables for testing. To bridge this gap, there is a pressing need for a comprehensive experimental framework tailored to Martian conditions (Figure 9). Such a framework should systematically evaluate the performance of biocementation under simulated environmental stressors specific to Mars, including cyclic temperature fluctuations, periodic UV irradiation, reduced gravity, and low atmospheric pressure. Controlled experiments replicating these factors, individually and in combination, are essential to generate empirical data that can validate theoretical models, guide simulation efforts, and inform practical engineering decisions for future Martian construction.

- 4.

- Evidence Gap: This type of research gap typically arises after preliminary studies or conceptual proposals have been introduced, yet the resulting data remain inconclusive, inconsistently reproduced, or insufficiently validated through rigorous peer review. In the context of biocementation for Martian construction, only a limited number of studies [60,61,62,63] have reported initial applications of MICP-based approaches using Martian regolith simulants. However, these findings have not been widely replicated, nor have they been tested under mission-relevant environmental constraints. Moreover, critical performance parameters, such as long-term durability under Martian thermal cycling (including freeze–thaw processes), low atmospheric pressure fluctuations, and mechanical stresses arising from structural pressurization or aeolian (wind-driven) forces, remain largely unexplored, even under Earth-based laboratory conditions. Consequently, the current empirical evidence is insufficient to determine whether the issue lies in an unresolved knowledge gap or in a lack of reproducibility.

- 5.

- Population Gap: In the context of biocementation for Martian applications, this gap refers to the limited diversity of microbial species that have been explored for their suitability in extraterrestrial construction contexts. To date, only two primary organisms Sporosarcina pasteurii [60,61] and Thraustochytrium striatum [62,63] have been tested for their biocementation potential in Martian regolith simulants. Both species are terrestrial in origin and have not evolved to withstand the harsh environmental stressors found on Mars, such as extreme temperature fluctuations, high UV radiation, low atmospheric pressure, and desiccation.

- 6.

- Methodological Gap: This type of gap emerges when appropriate, standardized, or sufficiently advanced research methodologies are lacking for the investigation or implementation of a given concept. In the case of biocementation for Martian applications, the methodological gap is particularly significant due to the nascent and interdisciplinary nature of the field, where conventional experimental approaches are not readily transferable to the extreme and atypical conditions of the Martian environment. Most MICP studies conducted to date utilize terrestrial laboratory protocols optimized for Earth’s gravity, atmospheric pressure, temperature ranges, and gas composition. These methods fall short in several critical aspects when adapted to Mars-oriented research, such as reliance on simplified regolith simulants, testing under Earth-like environmental conditions, short experimental timeframes, and the absence of integrated modeling–experimentation feedback loops.

- 7.

- Practical-Knowledge Gap: This gap reflects a disconnect between theoretical or laboratory-based knowledge and the practical application of that knowledge in real-world, or mission-relevant, contexts. Due to the relatively nascent state of the field, this gap remains unresolved in the context of biocementation for Martian applications. To date, the practical implementation of biocementation under simulated Martian environmental conditions has not been systematically explored, even within controlled laboratory settings. As a result, no experimental data yet exists to assess the feasibility or performance of MICP-based construction under conditions approximating the Martian surface.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Data Availability

Acknowledgements

References

- Z. Chen, L. Zhang, Y. Tang, B. Chen, Pioneering lunar habitats through comparative analysis of in-situ concrete technologies: A critical review, Constr. Build. Mater. 435 (2024) 136833. [CrossRef]

- F. Neukart, Towards sustainable horizons: A comprehensive blueprint for Mars colonization, Heliyon 10 (2024) e26180. [CrossRef]

- M.Z. Naser, Extraterrestrial construction materials, Prog. Mater. Sci. 105 (2019) 100577. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, L. Hao, Y. Li, Q. Sun, M. Sun, Y. Huang, Z. Li, D. Tang, Y. Wang, L. Xiao, In-situ utilization of regolith resource and future exploration of additive manufacturing for lunar/martian habitats: A review, Appl. Clay Sci. 229 (2022) 106673. [CrossRef]

- H. Zuo, S. Ni, M. Xu, An assumption of in situ resource utilization for “bio-bricks” in space exploration, Front. Mater. 10 (2023) 1155643. [CrossRef]

- K.W. Farries, P. Visintin, S.T. Smith, P. Van Eyk, Sintered or melted regolith for lunar construction: state-of-the-art review and future research directions, Constr. Build. Mater. 296 (2021) 123627. [CrossRef]

- H.A. Toutanji, S. Evans, R.N. Grugel, Performance of lunar sulfur concrete in lunar environments, Constr. Build. Mater. 29 (2012) 444–448. [CrossRef]

- L. Cai, L. Ding, H. Luo, X. Yi, Preparation of autoclave concrete from basaltic lunar regolith simulant: Effect of mixture and manufacture process, Constr. Build. Mater. 207 (2019) 373–386. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen, T. Wang, F. Li, S. Zhou, Preparation of geopolymer for in-situ pavement construction on the moon utilizing minimal additives and human urine in lunar regolith simulant, Front. Mater. 11 (2024) 1413432. [CrossRef]

- J.J. Sokołowska, P. Woyciechowski, M. Kalinowski, Rheological Properties of Lunar Mortars, Appl. Sci. 11 (2021) 6961. [CrossRef]

- Q. Cui, T. Wang, G. Gu, R. Zhang, T. Zhao, Z. Huang, G. Wang, F. Chen, Ultraviolet and thermal dual-curing assisted extrusion-based additive manufacturing of lunar regolith simulant for in-site construction on the Moon, Constr. Build. Mater. 425 (2024) 136010. [CrossRef]

- MARS GLOBAL SURVEYOR RAW DATA SET - CRUISE V1.0, (2025). https://catalog.data.gov/dataset/mars-global-surveyor-raw-data-set-cruise-v1-0-ad4ef?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed May 17, 2025).

- PDS Geosciences Node Data and Services: 2001 Mars Odyssey, (n.d.). https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/odyssey/ (accessed May 17, 2025).

- PDS Geosciences Node Data and Services: ESA Mars Express Mission, (n.d.). https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/mars_express/default.htm (accessed May 17, 2025).

- EMM Science Data Center, (n.d.). https://sdc.emiratesmarsmission.ae/ (accessed May 13, 2025).

- PDS Geosciences Node Data and Services: Viking Lander, (n.d.). https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/vlander/index.htm (accessed May 17, 2025).

- PDS Geosciences Node Data and Services: Mars Pathfinder, (n.d.). https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/mpf/index.htm (accessed May 17, 2025).

- PDS Geosciences Node Data and Services: Phoenix Mission, (n.d.). https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/phoenix/index.htm (accessed May 17, 2025).

- PDS Geosciences Node Data and Services: Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Mission, (n.d.). https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/msl/index.htm (accessed May 17, 2025).

- PDS Geosciences Node Data and Services: InSight Mission, (n.d.). https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/insight/index.htm (accessed May 17, 2025).

- Mars Orbiters and Landers, (n.d.). https://pds-atmospheres.nmsu.edu/data_and_services/atmospheres_data/MARS/mars_lander.html (accessed May 13, 2025).

- PDS Geosciences Node Data and Services: Mars 2020 Mission, (n.d.). https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/mars2020/index.htm (accessed May 17, 2025).

- Map of NASA’s Mars Landing Sites - NASA Science, (2020). https://science.nasa.gov/resource/map-of-nasas-mars-landing-sites/ (accessed March 27, 2025).

- M.Z. Naser, Q. Chen, Extraterrestrial Construction in Lunar and Martian Environments, in: Earth Space 2021, American Society of Civil Engineers, Virtual Conference, 2021: pp. 1200–1207. [CrossRef]

- L. Wan, R. Wendner, G. Cusatis, A novel material for in situ construction on Mars: experiments and numerical simulations, Constr. Build. Mater. 120 (2016) 222–231. [CrossRef]

- M.H. Shahsavari, M.M. Karbala, S. Iranfar, V. Vandeginste, Martian and lunar sulfur concrete mechanical and chemical properties considering regolith ingredients and sublimation, Constr. Build. Mater. 350 (2022) 128914. [CrossRef]

- H.A. Lowenstam, S. Weiner, H.A. Lowenstam, S. Weiner, On Biomineralization, Oxford University Press, Oxford, New York, 1989.

- S. Mann, Biomineralization Principles and Concepts in Bioinorganic Materials Chemistry, Oxford University Press, 2001. [CrossRef]

- S. Khoshtinat, J. Long-Fox, S.M.J. Hosseini, From Earth to Mars: A Perspective on Exploiting Biomineralization for Martian Construction, (2025). [CrossRef]

- A.I. Omoregie, E.A. Palombo, D.E.L. Ong, P.M. Nissom, A feasible scale-up production of Sporosarcina pasteurii using custom-built stirred tank reactor for in-situ soil biocementation, Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 24 (2020) 101544. [CrossRef]

- K.M.N.S. Wani, B.A. Mir, An Experimental Study on the Bio-cementation and Bio-clogging Effect of Bacteria in Improving Weak Dredged Soils, Geotech. Geol. Eng. 39 (2021) 317–334. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Sharaky, N.S. Mohamed, M.E. Elmashad, N.M. Shredah, Application of microbial biocementation to improve the physico-mechanical properties of sandy soil, Constr. Build. Mater. 190 (2018) 861–869. [CrossRef]

- K. Xu, M. Huang, C. Xu, J. Zhen, G. Jin, H. Gong, Assessment of the bio-cementation effect on shale soil using ultrasound measurement, Soils Found. 63 (2023) 101249. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Dubey, K. Ravi, A. Mukherjee, L. Sahoo, M.A. Abiala, N.K. Dhami, Biocementation mediated by native microbes from Brahmaputra riverbank for mitigation of soil erodibility, Sci. Rep. 11 (2021) 15250. [CrossRef]

- L. Cheng, M.A. Shahin, R. Cord-Ruwisch, Bio-cementation of sandy soil using microbially induced carbonate precipitation for marine environments, Géotechnique 64 (2014) 1010–1013. [CrossRef]

- H. Abdel-Aleem, T. Dishisha, A. Saafan, A.A. AbouKhadra, Y. Gaber, Biocementation of soil by calcite/aragonite precipitation using Pseudomonas azotoformans and Citrobacter freundii derived enzymes, RSC Adv. 9 (2019) 17601–17611. [CrossRef]

- J. Yin, J.-X. Wu, K. Zhang, M.A. Shahin, L. Cheng, Comparison between MICP-Based Bio-Cementation Versus Traditional Portland Cementation for Oil-Contaminated Soil Stabilisation, Sustainability 15 (2022) 434. [CrossRef]

- P.J. Venda Oliveira, J.P.G. Neves, Effect of Organic Matter Content on Enzymatic Biocementation Process Applied to Coarse-Grained Soils, J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 31 (2019) 04019121. [CrossRef]

- V.S. Whiffin, L.A. van Paassen, M.P. Harkes, Microbial carbonate precipitation as a soil improvement technique, Geomicrobiol. J. 24 (2007) 417–423. [CrossRef]

- D. Mujah, M.A. Shahin, L. Cheng, State-of-the-Art Review of Biocementation by Microbially Induced Calcite Precipitation (MICP) for Soil Stabilization, Geomicrobiol. J. 34 (2017) 524–537. [CrossRef]

- A.I. Omoregie, E.A. Palombo, P.M. Nissom, Bioprecipitation of calcium carbonate mediated by ureolysis: A review, Environ. Eng. Res. 26 (2021). [CrossRef]

- D.M. Iqbal, L.S. Wong, S.Y. Kong, Bio-Cementation in Construction Materials: A Review, Materials 14 (2021) 2175. [CrossRef]

- N.N.T. Huynh, K. Imamoto, C. Kiyohara, A Study on Biomineralization using Bacillus Subtilis Natto for Repeatability of Self-Healing Concrete and Strength Improvement, J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 17 (2019) 700–714. [CrossRef]

- M. Bagga, C. Hamley-Bennett, A. Alex, B.L. Freeman, I. Justo-Reinoso, I.C. Mihai, S. Gebhard, K. Paine, A.D. Jefferson, E. Masoero, I.D. Ofiţeru, Advancements in bacteria based self-healing concrete and the promise of modelling, Constr. Build. Mater. 358 (2022) 129412. [CrossRef]

- N.N.T. Huynh, N.M. Phuong, N.P.A. Toan, N.K. Son, Bacillus Subtilis HU58 Immobilized in Micropores of Diatomite for Using in Self-healing Concrete, Procedia Eng. 171 (2017) 598–605. [CrossRef]

- N.N.T. Huynh, K. Imamoto, C. Kiyohara, Biomineralization Analysis and Hydration Acceleration Effect in Self-healing Concrete using Bacillus subtilis natto, J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 20 (2022) 609–623. [CrossRef]

- N. Huynh, K. Imamoto, C. Kiyohara, Compressive Strength Improvement and Water Permeability of Self-Healing Concrete Using Bacillus Subtilis Natto, in: XV Int. Conf. Durab. Build. Mater. Compon. EBook Proc., CIMNE, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Joshi, S. Goyal, M.S. Reddy, Corn steep liquor as a nutritional source for biocementation and its impact on concrete structural properties, J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 45 (2018) 657–667. [CrossRef]

- M. Wu, X. Hu, Q. Zhang, D. Xue, Y. Zhao, Growth environment optimization for inducing bacterial mineralization and its application in concrete healing, Constr. Build. Mater. 209 (2019) 631–643. [CrossRef]

- S. Krishnapriya, D.L. Venkatesh Babu, P.A. G., Isolation and identification of bacteria to improve the strength of concrete, Microbiol. Res. 174 (2015) 48–55. [CrossRef]

- M.J. Castro-Alonso, L.E. Montañez-Hernandez, M.A. Sanchez-Muñoz, M.R. Macias Franco, R. Narayanasamy, N. Balagurusamy, Microbially Induced Calcium Carbonate Precipitation (MICP) and Its Potential in Bioconcrete: Microbiological and Molecular Concepts, Front. Mater. 6 (2019) 126. [CrossRef]

- R. Devrani, A.A. Dubey, K. Ravi, L. Sahoo, Applications of bio-cementation and bio-polymerization for aeolian erosion control, J. Arid Environ. 187 (2021) 104433. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Fattahi, A. Soroush, N. Huang, Biocementation Control of Sand against Wind Erosion, J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 146 (2020) 04020045. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Dubey, R. Devrani, K. Ravi, N.K. Dhami, A. Mukherjee, L. Sahoo, Experimental investigation to mitigate aeolian erosion via biocementation employed with a novel ureolytic soil isolate, Aeolian Res. 52 (2021) 100727. [CrossRef]

- S.M.A. Zomorodian, H. Ghaffari, B.C. O’Kelly, Stabilisation of crustal sand layer using biocementation technique for wind erosion control, Aeolian Res. 40 (2019) 34–41. [CrossRef]

- X. Xu, H. Guo, M. Li, X. Deng, Bio-cementation improvement via CaCO3 cementation pattern and crystal polymorph: A review, Constr. Build. Mater. 297 (2021) 123478. [CrossRef]

- K.D. Mutitu, M.O. Munyao, M.J. Wachira, R. Mwirichia, K.J. Thiong’o, M.J. Marangu, Effects of biocementation on some properties of cement-based materials incorporating Bacillus Species bacteria – a review, J. Sustain. Cem.-Based Mater. 8 (2019) 309–325. [CrossRef]

- B. Aytekin, A. Mardani, Ş. Yazıcı, State-of-art review of bacteria-based self-healing concrete: Biomineralization process, crack healing, and mechanical properties, Constr. Build. Mater. 378 (2023) 131198. [CrossRef]

- M. Amran, A.M. Onaizi, R. Fediuk, N.I. Vatin, R.S. Muhammad Rashid, H. Abdelgader, T. Ozbakkaloglu, Self-Healing Concrete as a Prospective Construction Material: A Review, Materials 15 (2022) 3214. [CrossRef]

- R. Dikshit, N. Gupta, A. Dey, K. Viswanathan, A. Kumar, Microbial induced calcite precipitation can consolidate martian and lunar regolith simulants, PLOS ONE 17 (2022) e0266415. [CrossRef]

- N. Gupta, R. Kulkarni, A.R. Naik, K. Viswanathan, A. Kumar, Bacterial bio-cementation can repair space bricks, Front. Space Technol. 6 (2025) 1550526. [CrossRef]

- J. Gleaton, R. Xiao, Z. Lai, N. McDaniel, C.A. Johnstone, B. Burden, Q. Chen, Y. Zheng, Biocementation of Martian Regolith Simulant with In Situ Resources, in: Earth Space 2018, American Society of Civil Engineers, Cleveland, Ohio, 2018: pp. 591–599. [CrossRef]

- J. Gleaton, Z. Lai, R. Xiao, Q. Chen, Y. Zheng, Microalga-induced biocementation of martian regolith simulant: Effects of biogrouting methods and calcium sources, Constr. Build. Mater. 229 (2019) 116885. [CrossRef]

- T. Perez-Gonzalez, C. Jimenez-Lopez, A.L. Neal, F. Rull-Perez, A. Rodriguez-Navarro, A. Fernandez-Vivas, E. Iañez-Pareja, Magnetite biomineralization induced by Shewanella oneidensis, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74 (2010) 967–979. [CrossRef]

- L. Fu, S.-W. Li, Z.-W. Ding, J. Ding, Y.-Z. Lu, R.J. Zeng, Iron reduction in the DAMO/Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 coculture system and the fate of Fe(II), Water Res. 88 (2016) 808–815. [CrossRef]

- L. Kong, S. Sun, B. Liu, S. Zhang, X. Zhang, Y. Liu, H. Yang, Y. Zhao, Microbial treatment of aluminosilicate solid wastes: A green technique for cementitious materials, J. Clean. Prod. 499 (2025) 145216. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, F. Li, Magnesium isotope fractionation during carbonate precipitation associated with bacteria and extracellular polymeric substances, Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 173 (2022) 105441. [CrossRef]

- H. Porter, A. Mukherjee, R. Tuladhar, N.K. Dhami, Life Cycle Assessment of Biocement: An Emerging Sustainable Solution?, Sustainability 13 (2021) 13878. [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A. Saha, D. Ghosh, B. Dam, A.K. Samanta, S. Dutta, Microbial repairing of concrete & its role in CO2 sequestration: a critical review, Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 12 (2023) 7. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Chu, S. Wu, Y. Hong, 3D characterization of microbially induced carbonate precipitation in rock fracture and the resulted permeability reduction, Eng. Geol. 249 (2019) 23–30. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, K. Soga, J.T. Dejong, A.J. Kabla, Microscale Visualization of Microbial-Induced Calcium Carbonate Precipitation Processes, J. Geotech. Geoenvironmental Eng. 145 (2019). [CrossRef]

- S. Khoshtinat, Advancements in Exploiting Sporosarcina pasteurii as Sustainable Construction Material: A Review, Sustainability 15 (2023) 13869. [CrossRef]

- . Erdmann, D. Strieth, Influencing factors on ureolytic microbiologically induced calcium carbonate precipitation for biocementation, World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39 (2022) 61. [CrossRef]

- C. Dupraz, P.T. Visscher, Microbial lithification in marine stromatolites and hypersaline mats, Trends Microbiol. 13 (2005) 429–438. [CrossRef]

- L.A. van Paassen, C.M. Daza, M. Staal, D.Y. Sorokin, W. van der Zon, Mark.C.M. van Loosdrecht, Potential soil reinforcement by biological denitrification, Ecol. Eng. 36 (2010) 168–175. [CrossRef]

- J.T. DeJong, B.M. Mortensen, B.C. Martinez, D.C. Nelson, Bio-mediated soil improvement, Ecol. Eng. 36 (2010) 197–210. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhu, M. Dittrich, Carbonate Precipitation through Microbial Activities in Natural Environment, and Their Potential in Biotechnology: A Review, Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 4 (2016). [CrossRef]

- V. Achal, A. Mukherjee, D. Kumari, Q. Zhang, Biomineralization for sustainable construction – A review of processes and applications, Earth-Sci. Rev. 148 (2015) 1–17. [CrossRef]

- B. Krajewska, Urease-aided calcium carbonate mineralization for engineering applications: A review, J. Adv. Res. 13 (2018) 59–67. [CrossRef]

- H.L. Mobley, R.P. Hausinger, Microbial ureases: significance, regulation, and molecular characterization, Microbiol. Rev. (1989). [CrossRef]

- D. Ariyanti, Feasibility of Using Microalgae for Biocement Production through Biocementation, J. Bioprocess. Biotech. 02 (2012). [CrossRef]

- J. Gleaton, Z. Lai, R. Xiao, Q. Chen, Y. Zheng, Microalga-induced biocementation of martian regolith simulant: Effects of biogrouting methods and calcium sources, Constr. Build. Mater. 229 (2019) 116885. [CrossRef]

- L.J. Mapstone, M.N. Leite, S. Purton, I.A. Crawford, L. Dartnell, Cyanobacteria and microalgae in supporting human habitation on Mars, Biotechnol. Adv. 59 (2022) 107946. [CrossRef]

- C. Fang, D. Kumari, X. Zhu, V. Achal, Role of fungal-mediated mineralization in biocementation of sand and its improved compressive strength, Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 133 (2018) 216–220. [CrossRef]

- P.G. Oktafiani, H. Putra, Erizal, D.H.Y. Yanto, Application of technical grade reagent in soybean-crude urease calcite precipitation (SCU-CP) method for soil improvement technique, Phys. Chem. Earth Parts ABC 128 (2022) 103292. [CrossRef]

- D. Guan, Y. Zhou, M.A. Shahin, H. Khodadadi Tirkolaei, L. Cheng, Assessment of urease enzyme extraction for superior and economic bio-cementation of granular materials using enzyme-induced carbonate precipitation, Acta Geotech. 18 (2023) 2263–2279. [CrossRef]

- Miftah, H. Khodadadi Tirkolaei, H. Bilsel, Biocementation of Calcareous Beach Sand Using Enzymatic Calcium Carbonate Precipitation, Crystals 10 (2020) 888. [CrossRef]

- Y.J. Phua, A. Røyne, Bio-cementation through controlled dissolution and recrystallization of calcium carbonate, Constr. Build. Mater. 167 (2018) 657–668. [CrossRef]

- G.A.M. Metwally, M. Mahdy, A.E.-R.H. Abd El-Raheem, Performance of Bio Concrete by Using Bacillus Pasteurii Bacteria, Civ. Eng. J. 6 (2020) 1443–1456. [CrossRef]

- Z. Tian, X. Tang, Z. Xiu, Z. Xue, The Spatial Distribution of Microbially Induced Carbonate Precipitation in Sand Column with Different Grouting Strategies, J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 35 (2023) 04022437. [CrossRef]

- M.V.S. Rao, V.S. Reddy, Ch. Sasikala, Performance of Microbial Concrete Developed Using Bacillus Subtilus JC3, J. Inst. Eng. India Ser. A 98 (2017) 501–510. [CrossRef]

- G. Kaur, N.K. Dhami, S. Goyal, A. Mukherjee, M.S. Reddy, Utilization of carbon dioxide as an alternative to urea in biocementation, Constr. Build. Mater. 123 (2016) 527–533. [CrossRef]

- C. Fang, J. He, V. Achal, G. Plaza, Tofu Wastewater as Efficient Nutritional Source in Biocementation for Improved Mechanical Strength of Cement Mortars, Geomicrobiol. J. 36 (2019) 515–521. [CrossRef]

- B. Perito, M. Marvasi, C. Barabesi, G. Mastromei, S. Bracci, M. Vendrell, P. Tiano, A Bacillus subtilis cell fraction (BCF) inducing calcium carbonate precipitation: Biotechnological perspectives for monumental stone reinforcement, J. Cult. Herit. 15 (2014) 345–351. [CrossRef]

- K.A. Joshi, M.B. Kumthekar, V.P. Ghodake, Bacillus Subtilis Bacteria Impregnation in Concrete for Enhancement in Compressive Strength, 03 (n.d.).

- Z.-F. Xue, W.-C. Cheng, M.M. Rahman, L. Wang, Y.-X. Xie, Immobilization of Pb(II) by Bacillus megaterium-based microbial-induced phosphate precipitation (MIPP) considering bacterial phosphorolysis ability and Ca-mediated alleviation of lead toxicity, Environ. Pollut. 355 (2024) 124229. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Andersen, H.S. Mortensen, R. Bossi, C.S. Jacobsen, Isolation and characterisation of Rhodococcus erythropolis TA57 able to degrade the triazine amine product from hydrolysis of sulfonylurea pesticides in soils, Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 24 (2001) 262–266. [CrossRef]

- C. Jansson, T. Northen, Calcifying cyanobacteria—the potential of biomineralization for carbon capture and storage, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 21 (2010) 365–371. [CrossRef]

- D.M. Hassler, C. D.M. Hassler, C. Zeitlin, R.F. Wimmer-Schweingruber, B. Ehresmann, S. Rafkin, J.L. Eigenbrode, D.E. Brinza, G. Weigle, S. Böttcher, E. Böhm, S. Burmeister, J. Guo, J. Köhler, C. Martin, G. Reitz, F.A. Cucinotta, M.-H. Kim, D. Grinspoon, M.A. Bullock, A. Posner, J. Gómez-Elvira, A. Vasavada, J.P. Grotzinger, M.S. Team, O. Kemppinen, D. Cremers, J.F. Bell, L. Edgar, J. Farmer, A. Godber, M. Wadhwa, D. Wellington, I. McEwan, C. Newman, M. Richardson, A. Charpentier, L. Peret, P. King, J. Blank, M. Schmidt, S. Li, R. Milliken, K. Robertson, V. Sun, M. Baker, C. Edwards, B. Ehlmann, K. Farley, J. Griffes, H. Miller, M. Newcombe, C. Pilorget, M. Rice, K. Siebach, K. Stack, E. Stolper, C. Brunet, V. Hipkin, R. Léveillé, G. Marchand, P.S. Sánchez, L. Favot, G. Cody, A. Steele, L. Flückiger, D. Lees, A. Nefian, M. Martin, M. Gailhanou, F. Westall, G. Israël, C. Agard, J. Baroukh, C. Donny, A. Gaboriaud, P. Guillemot, V. Lafaille, E. Lorigny, A. Paillet, R. Pérez, M. Saccoccio, C. Yana, C. Armiens-Aparicio, J.C. Rodríguez, I.C. Blázquez, F.G. Gómez, S. Hettrich, A.L. Malvitte, M.M. Jiménez, J. Martínez-Frías, J. Martín-Soler, F.J. Martín-Torres, A.M. Jurado, L. Mora-Sotomayor, G.M. Caro, S.N. López, V. Peinado-González, J. Pla-García, J.A.R. Manfredi, J.J. Romeral-Planelló, S.A.S. Fuentes, E.S. Martinez, J.T. Redondo, R. Urqui-O’Callaghan, M.-P.Z. Mier, S. Chipera, J.-L. Lacour, P. Mauchien, J.-B. Sirven, H. Manning, A. Fairén, A. Hayes, J. Joseph, S. Squyres, R. Sullivan, P. Thomas, A. Dupont, A. Lundberg, N. Melikechi, A. Mezzacappa, T. Berger, D. Matthia, B. Prats, E. Atlaskin, M. Genzer, A.-M. Harri, H. Haukka, H. Kahanpää, J. Kauhanen, O. Kemppinen, M. Paton, J. Polkko, W. Schmidt, T. Siili, C. Fabre, J. Wray, M.B. Wilhelm, F. Poitrasson, K. Patel, S. Gorevan, S. Indyk, G. Paulsen, S. Gupta, D. Bish, J. Schieber, B. Gondet, Y. Langevin, C. Geffroy, D. Baratoux, G. Berger, A. Cros, C. d’Uston, O. Forni, O. Gasnault, J. Lasue, Q.-M. Lee, S. Maurice, P.-Y. Meslin, E. Pallier, Y. Parot, P. Pinet, S. Schröder, M. Toplis, É. Lewin, W. Brunner, E. Heydari, C. Achilles, D. Oehler, B. Sutter, M. Cabane, D. Coscia, G. Israël, C. Szopa, G. Dromart, F. Robert, V. Sautter, S. Le Mouélic, N. Mangold, M. Nachon, A. Buch, F. Stalport, P. Coll, P. François, F. Raulin, S. Teinturier, J. Cameron, S. Clegg, A. Cousin, D. DeLapp, R. Dingler, R.S. Jackson, S. Johnstone, N. Lanza, C. Little, T. Nelson, R.C. Wiens, R.B. Williams, A. Jones, L. Kirkland, A. Treiman, B. Baker, B. Cantor, M. Caplinger, S. Davis, B. Duston, K. Edgett, D. Fay, C. Hardgrove, D. Harker, P. Herrera, E. Jensen, M.R. Kennedy, G. Krezoski, D. Krysak, L. Lipkaman, M. Malin, E. McCartney, S. McNair, B. Nixon, L. Posiolova, M. Ravine, A. Salamon, L. Saper, K. Stoiber, K. Supulver, J. Van Beek, T. Van Beek, R. Zimdar, K.L. French, K. Iagnemma, K. Miller, R. Summons, F. Goesmann, W. Goetz, S. Hviid, M. Johnson, M. Lefavor, E. Lyness, E. Breves, M.D. Dyar, C. Fassett, D.F. Blake, T. Bristow, D. DesMarais, L. Edwards, R. Haberle, T. Hoehler, J. Hollingsworth, M. Kahre, L. Keely, C. McKay, M.B. Wilhelm, L. Bleacher, W. Brinckerhoff, D. Choi, P. Conrad, J.P. Dworkin, M. Floyd, C. Freissinet, J. Garvin, D. Glavin, D. Harpold, A. Jones, P. Mahaffy, D.K. Martin, A. McAdam, A. Pavlov, E. Raaen, M.D. Smith, J. Stern, F. Tan, M. Trainer, M. Meyer, M. Voytek, R.C. Anderson, A. Aubrey, L.W. Beegle, A. Behar, D. Blaney, F. Calef, L. Christensen, J.A. Crisp, L. DeFlores, B. Ehlmann, J. Feldman, S. Feldman, G. Flesch, J. Hurowitz, I. Jun, D. Keymeulen, J. Maki, M. Mischna, J.M. Morookian, T. Parker, B. Pavri, M. Schoppers, A. Sengstacken, J.J. Simmonds, N. Spanovich, M.D.L.T. Juarez, C.R. Webster, A. Yen, P.D. Archer, J.H. Jones, D. Ming, R.V. Morris, P. Niles, E. Rampe, T. Nolan, M. Fisk, L. Radziemski, B. Barraclough, S. Bender, D. Berman, E.N. Dobrea, R. Tokar, D. Vaniman, R.M.E. Williams, A. Yingst, K. Lewis, L. Leshin, T. Cleghorn, W. Huntress, G. Manhès, J. Hudgins, T. Olson, N. Stewart, P. Sarrazin, J. Grant, E. Vicenzi, S.A. Wilson, V. Hamilton, J. Peterson, F. Fedosov, D. Golovin, N. Karpushkina, A. Kozyrev, M. Litvak, A. Malakhov, I. Mitrofanov, M. Mokrousov, S. Nikiforov, V. Prokhorov, A. Sanin, V. Tretyakov, A. Varenikov, A. Vostrukhin, R. Kuzmin, B. Clark, M. Wolff, S. McLennan, O. Botta, D. Drake, K. Bean, M. Lemmon, S.P. Schwenzer, R.B. Anderson, K. Herkenhoff, E.M. Lee, R. Sucharski, M.Á.D.P. Hernández, J.J.B. Ávalos, M. Ramos, C. Malespin, I. Plante, J.-P. Muller, R. Navarro-González, R. Ewing, W. Boynton, R. Downs, M. Fitzgibbon, K. Harshman, S. Morrison, W. Dietrich, O. Kortmann, M. Palucis, D.Y. Sumner, A. Williams, G. Lugmair, M.A. Wilson, D. Rubin, B. Jakosky, T. Balic-Zunic, J. Frydenvang, J.K. Jensen, K. Kinch, A. Koefoed, M.B. Madsen, S.L.S. Stipp, N. Boyd, J.L. Campbell, R. Gellert, G. Perrett, I. Pradler, S. VanBommel, S. Jacob, T. Owen, S. Rowland, E. Atlaskin, H. Savijärvi, C.M. García, R. Mueller-Mellin, J.C. Bridges, T. McConnochie, M. Benna, H. Franz, H. Bower, A. Brunner, H. Blau, T. Boucher, M. Carmosino, S. Atreya, H. Elliott, D. Halleaux, N. Rennó, M. Wong, R. Pepin, B. Elliott, J. Spray, L. Thompson, S. Gordon, H. Newsom, A. Ollila, J. Williams, P. Vasconcelos, J. Bentz, K. Nealson, R. Popa, L.C. Kah, J. Moersch, C. Tate, M. Day, G. Kocurek, B. Hallet, R. Sletten, R. Francis, E. McCullough, E. Cloutis, I.L. Ten Kate, R. Kuzmin, R. Arvidson, A. Fraeman, D. Scholes, S. Slavney, T. Stein, J. Ward, J. Berger, J.E. Moores, Mars’ Surface Radiation Environment Measured with the Mars Science Laboratory’s Curiosity Rover, Science 343 (2014) 1244797. [CrossRef]

- Temperatures Across Our Solar System - NASA Science, (2023). https://science.nasa.gov/solar-system/temperatures-across-our-solar-system/ (accessed March 15, 2025).

- With Mars Methane Mystery Unsolved, Curiosity Serves Scientists a New One: Oxygen - NASA, (2019). https://www.nasa.gov/missions/with-mars-methane-mystery-unsolved-curiosity-serves-scientists-a-new-one-oxygen/ (accessed March 15, 2025).

- Martian Seasons and Solar Longitude Ls, (n.d.). https://www-mars.lmd.jussieu.fr/mars/time/solar_longitude.html (accessed March 27, 2025).

- S.R. Taylor, S. McLennan, Planetary Crusts: Their Composition, Origin and Evolution, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Y. Roh, C.-L. Zhang, H. Vali, R.J. Lauf, J. Zhou, T.J. Phelps, Biogeochemical and Environmental Factors in Fe Biomineralization: Magnetite and Siderite Formation, Clays Clay Miner. 51 (2003) 83–95. [CrossRef]

- X. Han, F. Wang, S. Zheng, H. Qiu, Y. Liu, J. Wang, N. Menguy, E. Leroy, J. Bourgon, A. Kappler, F. Liu, Y. Pan, J. Li, Morphological, Microstructural, and In Situ Chemical Characteristics of Siderite Produced by Iron-Reducing Bacteria, Environ. Sci. Technol. 58 (2024) 11016–11026. [CrossRef]

- R.V. Morris, G. Klingelhöfer, C. Schröder, D.S. Rodionov, A. Yen, D.W. Ming, P.A. De Souza, T. Wdowiak, I. Fleischer, R. Gellert, B. Bernhardt, U. Bonnes, B.A. Cohen, E.N. Evlanov, J. Foh, P. Gütlich, E. Kankeleit, T. McCoy, D.W. Mittlefehldt, F. Renz, M.E. Schmidt, B. Zubkov, S.W. Squyres, R.E. Arvidson, Mössbauer mineralogy of rock, soil, and dust at Meridiani Planum, Mars: Opportunity’s journey across sulfate-rich outcrop, basaltic sand and dust, and hematite lag deposits, J. Geophys. Res. Planets 111 (2006) 2006JE002791. [CrossRef]

- B.C. Clark, A.K. Baird, R.J. Weldon, D.M. Tsusaki, L. Schnabel, M.P. Candelaria, Chemical composition of Martian fines, J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 87 (1982) 10059–10067. [CrossRef]

- R. Gellert, R. Rieder, R.C. Anderson, J. Brückner, B.C. Clark, G. Dreibus, T. Economou, G. Klingelhöfer, G.W. Lugmair, D.W. Ming, S.W. Squyres, C. d’Uston, H. Wänke, A. Yen, J. Zipfel, Chemistry of Rocks and Soils in Gusev Crater from the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer, Science 305 (2004) 829–832. [CrossRef]

- R. Rieder, R. Gellert, R.C. Anderson, J. Brückner, B.C. Clark, G. Dreibus, T. Economou, G. Klingelhöfer, G.W. Lugmair, D.W. Ming, S.W. Squyres, C. d’Uston, H. Wänke, A. Yen, J. Zipfel, Chemistry of Rocks and Soils at Meridiani Planum from the Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer, Science 306 (2004) 1746–1749. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C150, (n.d.). https://compass.astm.org/document/?contentCode=ASTM%7CC0150_C0150M-24%7Cen-US (accessed March 15, 2025).

- G.H. Peters, W. Abbey, G.H. Bearman, G.S. Mungas, J.A. Smith, R.C. Anderson, S. Douglas, L.W. Beegle, Mojave Mars simulant—Characterization of a new geologic Mars analog, Icarus 197 (2008) 470–479. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Long-Fox, D.T. Britt, Characterization of planetary regolith simulants for the research and development of space resource technologies, Front. Space Technol. 4 (2023) 1255535. [CrossRef]

- K.M. Cannon, D.T. Britt, T.M. Smith, R.F. Fritsche, D. Batcheldor, Mars global simulant MGS-1: A Rocknest-based open standard for basaltic martian regolith simulants, Icarus 317 (2019) 470–478. [CrossRef]

- Martian Regolith Simulants, Space Resour. Technol. (n.d.). https://spaceresourcetech.com/collections/martian-simulants (accessed March 16, 2025).

- D.P. Mason, L.A. Scuderi, Interweaving recurring slope lineae on Mars: Do they support a wet hypothesis?, Icarus 419 (2024) 115980. [CrossRef]

- F.E.G. Butcher, Water Ice at Mid-Latitudes on Mars, in: Oxf. Res. Encycl. Planet. Sci., 2022. [CrossRef]

- T.R. Watters, B.A. Campbell, C.J. Leuschen, G.A. Morgan, A. Cicchetti, R. Orosei, J.J. Plaut, Evidence of Ice-Rich Layered Deposits in the Medusae Fossae Formation of Mars, Geophys. Res. Lett. 51 (2024) e2023GL105490. [CrossRef]

- R. Orosei, S.E. Lauro, E. Pettinelli, A. Cicchetti, M. Coradini, B. Cosciotti, F. Di Paolo, E. Flamini, E. Mattei, M. Pajola, F. Soldovieri, M. Cartacci, F. Cassenti, A. Frigeri, S. Giuppi, R. Martufi, A. Masdea, G. Mitri, C. Nenna, R. Noschese, M. Restano, R. Seu, Radar evidence of subglacial liquid water on Mars, Science 361 (2018) 490–4931 (2018) 490–493. [CrossRef]

- S. Fan, F. Forget, M.D. Smith, S. Guerlet, K.M. Badri, S.A. Atwood, R.M.B. Young, C.S. Edwards, P.R. Christensen, J. Deighan, H.R. Al Matroushi, A. Bierjon, J. Liu, E. Millour, Migrating Thermal Tides in the Martian Atmosphere During Aphelion Season Observed by EMM/EMIRS, Geophys. Res. Lett. 49 (2022) e2022GL099494. [CrossRef]

- D. Atri, N. Abdelmoneim, D.B. Dhuri, M. Simoni, Diurnal variation of the surface temperature of Mars with the Emirates Mars Mission: a comparison with Curiosity and Perseverance rover measurements, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. Lett. 518 (2023) L1–L6. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, S. Jin, Diurnal temperature cycle models and performances on Martian surface using in-situ and satellite data, Planet. Space Sci. (2025) 106100. [CrossRef]

- P.J. Collins, R.J. Thomas, A. Radlińska, Influence of gravity on the micromechanical properties of portland cement and lunar regolith simulant composites, Cem. Concr. Res. 172 (2023) 107232. [CrossRef]

- J. Moraes Neves, P.J. Collins, R.P. Wilkerson, R.N. Grugel, A. Radlińska, Microgravity Effect on Microstructural Development of Tri-calcium Silicate (C3S) Paste, Front. Mater. 6 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Microgravity Investigation of Cement Solidification (MICS) - NASA Science, (n.d.). https://science.nasa.gov/image-detail/mics/ (accessed March 22, 2025).

- Z. Yan, K. Nakashima, C. Takano, S. Kawasaki, Kitchen Waste Bone-Driven Enzyme-Induced Calcium Phosphate Precipitation under Microgravity for Space Biocementation, Biogeotechnics (2024) 100156. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Peterson, R.M. Daniel, M.J. Danson, R. Eisenthal, The dependence of enzyme activity on temperature: determination and validation of parameters, Biochem. J. 402 (2007) 331–337. [CrossRef]

- S. Khoshtinat, State-of-the-Art Review of Aliphatic Polyesters and Polyolefins Biodeterioration by Microorganisms: From Mechanism to Characterization, Corros. Mater. Degrad. 4 (2023) 542–572. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, Y. Wang, K. Soga, J.T. DeJong, A.J. Kabla, Microscale investigations of temperature-dependent microbially induced carbonate precipitation (MICP) in the temperature range 4–50 °C, Acta Geotech. 18 (2023) 2239–2261. [CrossRef]

- G. Feller, E. Narinx, J.L. Arpigny, Z. Zekhnini, J. Swings, C. Gerday, Temperature dependence of growth, enzyme secretion and activity of psychrophilic Antarctic bacteria, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 41 (1994) 477–479. [CrossRef]

- C. Gerday, Psychrophily and Catalysis, Biology 2 (2013) 719–741. [CrossRef]

- D.A. Newcombe, A.C. Schuerger, J.N. Benardini, D. Dickinson, R. Tanner, K. Venkateswaran, Survival of spacecraft-associated microorganisms under simulated martian UV irradiation, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71 (2005) 8147–8156. [CrossRef]

- S. Osman, Z. Peeters, M.T. La Duc, R. Mancinelli, P. Ehrenfreund, K. Venkateswaran, Effect of Shadowing on Survival of Bacteria under Conditions Simulating the Martian Atmosphere and UV Radiation, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74 (2008) 959–970. [CrossRef]

- R. Moeller, M. Rohde, G. Reitz, Effects of ionizing radiation on the survival of bacterial spores in artificial martian regolith, Icarus 206 (2010) 783–786. [CrossRef]

- C. Mosca, L.J. Rothschild, A. Napoli, F. Ferré, M. Pietrosanto, C. Fagliarone, M. Baqué, E. Rabbow, P. Rettberg, D. Billi, Over-Expression of UV-Damage DNA Repair Genes and Ribonucleic Acid Persistence Contribute to the Resilience of Dried Biofilms of the Desert Cyanobacetrium Chroococcidiopsis Exposed to Mars-Like UV Flux and Long-Term Desiccation, Front. Microbiol. 10 (2019) 2312. [CrossRef]

- M. Baqué, J.-P. de Vera, P. Rettberg, D. Billi, The BOSS and BIOMEX space experiments on the EXPOSE-R2 mission: Endurance of the desert cyanobacterium Chroococcidiopsis under simulated space vacuum, Martian atmosphere, UVC radiation and temperature extremes., Acta Astronaut. 91 (2013) 180–186. [CrossRef]

- D. Billi, C. Staibano, C. Verseux, C. Fagliarone, C. Mosca, M. Baqué, E. Rabbow, P. Rettberg, Dried Biofilms of Desert Strains of Chroococcidiopsis Survived Prolonged Exposure to Space and Mars-like Conditions in Low Earth Orbit, Astrobiology 19 (2019) 1008–1017. [CrossRef]

- D. Billi, E.I. Friedmann, K.G. Hofer, M.G. Caiola, R. Ocampo-Friedmann, Ionizing-Radiation Resistance in the Desiccation-Tolerant CyanobacteriumChroococcidiopsis, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66 (2000) 1489–1492. [CrossRef]

- T.L. Foster, L. Winans, R.C. Casey, L.E. Kirschner, Response of terrestrial microorganisms to a simulated Martian environment., Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 35 (1978) 730–737. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC242914/ (accessed March 31, 2025).

- B.J. Berry, D.G. Jenkins, A.C. Schuerger, Effects of Simulated Mars Conditions on the Survival and Growth of Escherichia coli and Serratia liquefaciens, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76 (2010) 2377–2386. [CrossRef]

- T. Zaccaria, M.I. de Jonge, J. Domínguez-Andrés, M.G. Netea, K. Beblo-Vranesevic, P. Rettberg, Survival of Environment-Derived Opportunistic Bacterial Pathogens to Martian Conditions: Is There a Concern for Human Missions to Mars?, Astrobiology 24 (2024) 100–113. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Montaño-Salazar, J. Lizarazo-Marriaga, P.F.B. Brandão, Isolation and Potential Biocementation of Calcite Precipitation Inducing Bacteria from Colombian Buildings, Curr. Microbiol. 75 (2018) 256–265. [CrossRef]

- S. Shu, B. Yan, B. Ge, S. Li, H. Meng, Factors Affecting Soybean Crude Urease Extraction and Biocementation via Enzyme-Induced Carbonate Precipitation (EICP) for Soil Improvement, Energies 15 (2022) 5566. [CrossRef]

- H. Rohy, M. Arab, W. Zeiada, M. Omar, A. Almajed, A. Tahmaz, One Phase Soil Bio-Cementation with EICP-Soil Mixing, in: 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Zehner, A. Røyne, P. Sikorski, A sample cell for the study of enzyme-induced carbonate precipitation at the grain-scale and its implications for biocementation, Sci. Rep. 11 (2021) 13675. [CrossRef]

- T. Hoang, J. Alleman, B. Cetin, S.-G. Choi, Engineering Properties of Biocementation Coarse- and Fine-Grained Sand Catalyzed By Bacterial Cells and Bacterial Enzyme, J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 32 (2020) 04020030. [CrossRef]

- J.S. Singh, P.C. Abhilash, H.B. Singh, R.P. Singh, D.P. Singh, Genetically engineered bacteria: an emerging tool for environmental remediation and future research perspectives, Gene 480 (2011) 1–9. [CrossRef]

- G. Pant, D. Garlapati, U. Agrawal, R.G. Prasuna, T. Mathimani, A. Pugazhendhi, Biological approaches practised using genetically engineered microbes for a sustainable environment: A review, J. Hazard. Mater. 405 (2021) 124631. [CrossRef]

- Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) » COSPAR Policy on Planetary Protection, COSPAR Website (n.d.). https://cosparhq.cnes.fr/cospar-policy-on-planetary-protection/ (accessed May 10, 2025).

- M. Baqué, G. Scalzi, E. Rabbow, P. Rettberg, D. Billi, Biofilm and Planktonic Lifestyles Differently Support the Resistance of the Desert Cyanobacterium Chroococcidiopsis Under Space and Martian Simulations, Orig. Life Evol. Biospheres 43 (2013) 377–389. [CrossRef]

- Z. Fang, P. Knoll, S. McMahon, L. Qin, C.S. Cockell, Preservation of Microorganisms (Chroococcidiopsis sp. 029) in Salt Minerals under Low Atmospheric Pressure: Application to Life Detection on Mars, Planet. Sci. J. 5 (2024) 263. [CrossRef]

- J.A. Hoffman, M.H. Hecht, D. Rapp, J.J. Hartvigsen, J.G. SooHoo, A.M. Aboobaker, J.B. McClean, A.M. Liu, E.D. Hinterman, M. Nasr, S. Hariharan, K.J. Horn, F.E. Meyen, H. Okkels, P. Steen, S. Elangovan, C.R. Graves, P. Khopkar, M.B. Madsen, G.E. Voecks, P.H. Smith, T.L. Skafte, K.R. Araghi, D.J. Eisenman, Mars Oxygen ISRU Experiment (MOXIE)—Preparing for human Mars exploration, Sci. Adv. 8 (2022) eabp8636. [CrossRef]

- L.E. Fackrell, S. Humphrey, R. Loureiro, A.G. Palmer, J. Long-Fox, Overview and recommendations for research on plants and microbes in regolith-based agriculture, Npj Sustain. Agric. 2 (2024) 15. [CrossRef]

- G.W.W. Wamelink, J.Y. Frissel, W.H.J. Krijnen, M.R. Verwoert, P.W. Goedhart, Can Plants Grow on Mars and the Moon: A Growth Experiment on Mars and Moon Soil Simulants, PLOS ONE 9 (2014) e103138. [CrossRef]

- M. RAMPINI, A. BACCHIEGA, Preliminary analysis of innovative inflatable habitats for Mars surface missions, (2021). https://www.politesi.polimi.it/handle/10589/173716 (accessed June 23, 2025).

- D. Miles, ARTICLE: “Research Methods and Strategies Workshop: A Taxonomy of Research Gaps: Identifying and Defining the Seven Research Gaps,” 1 (2017) 1.

- S. Khoshtinat, C. Marano, Numerical Modeling of the pH Effect on the Calcium Carbonate Precipitation by Sporosarcina pasteurii, in: M. Kioumarsi, B. Shafei (Eds.), 1st Int. Conf. Net-Zero Built Environ., Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2025: pp. 141–153. [CrossRef]

- S. Khoshtinat, C. Marano, M. Kioumarsi, Computational modeling of biocementation by S. pasteurii: effect of initial pH, Discov. Mater. 5 (2025) 65. [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Earth | Mars | |

| Gravitational acceleration [m/s2] | 9.81 (avg.), 9.78(equator) | 3.72 (equator) | |

| Diurnal cycle [Earth days] | 1 | 1.02 | |

| Rotation period [hours] | 23.9345 | 24.6229 | |

| Surface temperature range [°C] | -89 ̶ 58 | -153 ̶ 20 | |

| Magnetic vector field (A/m) | 24 ̶ 56 | 0 | |

| Atmospheric pressure [bar] | 1 | 6×10-3 | |

| Atmospheric composition | O2 | 20.9 % | 0.16 % |

| CO2 | 0.03 % | 95 % | |

| CO | 0.06 | ||

| N2 | 78.1 % | 2.6 % | |

| Ar | - | 1.9 % | |

| Daily surface radiation [mSv/day] | 2 ̶ 3 | 200 | |

| Month number | Ls range (degrees) | Sol range | duration (in sols) | Specificities |

| 1 | 0 ̶ 30 | 0.0 ̶ 61.2 | 61.2 | Northern Hemisphere Spring Equinox at Ls=0 |

| 2 | 30 ̶ 60 | 61.2 ̶ 126.6 | 65.4 | |

| 3 | 60 ̶ 90 | 126.6 ̶ 193.3 | 66.7 | Aphelion (largest Sun-Mars distance) at Ls=71 |

| 4 | 90 ̶ 120 | 193.3 ̶ 257.8 | 64.5 | Northern Hemisphere Summer Solstice at Ls=90 |

| 5 | 120 ̶ 150 | 257.8 ̶ 317.5 | 59.7 | |

| 6 | 150 ̶ 180 | 317.5 ̶ 371.9 | 54.4 | |

| 7 | 180 ̶ 210 | 371.9 ̶ 421.6 | 49.7 | Northern Hemisphere Autumn Equinox at Ls=180 Dust Storm Season begins |

| 8 | 210 ̶ 240 | 421.6 ̶ 468.5 | 46.9 | Dust Storm Season |

| 9 | 240 ̶ 270 | 468.5 ̶ 514.6 | 46.1 | Perihelion (smallest sun-Mars distance) at Ls=251 Dust Storm Season |

| 10 | 270 ̶ 300 | 514.6 ̶ 562.0 | 47.4 | Northern hemisphere Winter Solstice at Ls=270 Dust Storm Season |

| 11 | 300 ̶ 330 | 562.0 ̶ 612.9 | 50.9 | Dust Storm Season |

| 12 | 330 ̶ 360 | 612.9 ̶ 668.6 | 55.7 | Dust Storm Season ends |

|

Element/ Compound |

Crust [103] |

Soil [106] |

Dust [106] |

Viking 1 [107] |

Spirit [108] |

Opportunity [109] |

Portland Cement ASTM C150 [110] |

| Weight % | |||||||

| SiO2 | 49.3 | 46.65 ± 1.2 | 44.84 ± 0.52 | 44 | 45.8 ± 0.44 | 42.05 ± 4.25 | 17 ̶ 25 |

| TiO2 | 0.98 | 0.95 ± 0.18 | 0.95 ± 0.08 | 0.62 | 0.81 ± 0.08 | 1 ± 0.3 | ̶ |

| Al2O3 | 10.5 | 10.07 ± 0.71 | 9.32 ± 0.18 | 7.3 | 10 ± 0.22 | 8.3 ± 1.1 | ≤ 6 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.26 | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | ̶ | 0.35 ± 0.07 | ̶ | ̶ |

| Fe2O3 | ̶ | 4.28 ± 0.74 | 7.28 ± 0.70 | ̶ | ̶ | ̶ | ≤ 6 |

| FeO | 18.2 | 12.97 ± 1 | 10.42 ± 0.11 | 17.5 | 15.8 ± 0.36 | 26.2 ± 0.36 | ̶ |

| MnO | 0.36 | 0.36 ± 0.02 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | - | 0.31 ± 0.02 | 0.31 ± 7.2 | ̶ |

| MgO | 9.06 | 8.12 ± 0.45 | 7.89 ± 0.32 | 6 | 9.3 ± 0.24 | 6.9 ± 0.5 | ≤ 6 |

| CaO | 6.92 | 6.70 ± 0.28 | 6.34 ± 0.20 | 5.7 | 6.1 ± 0.27 | 6.34 ± 1.19 | 60 ̶ 67 |

| Na2O | 2.97 | 2.63 ± 0.37 | 2.56 ± 0.33 | ̶ | 3.3 ± 0.31 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | ̶ |

| K2O | 0.45 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.07 | < 0.5 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.06 | ̶ |

| P2O5 | 0.90 | 0.83 ± 0.23 | 0.92 ± 0.09 | ̶ | 0.84 ± 0.07 | ̶ | ̶ |

| SO3 | ̶ | 4.94 ± 0.74 | 7.42 ± 0.13 | 6.7 | 5.82 ± 0.86 | 5.91 ± 1.39 | < 3 |

| Cl | ̶ | 0.59 ± 0.08 | 0.83 ± 0.05 | 0.8 | 0.53 ± 0.13 | 0.4 ± 0.07 | ̶ |

| Fe3+ / FeT | ̶ | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | ̶ | ̶ | ̶ | ̶ |

| ppm or µg/g | |||||||

| Br | ̶ | 44 ± 27 | 28 ± 22 | ̶ | 40 ± 30 | ̶ | ̶ |

| Ni | 337 | 471 ± 159 | 552 ± 85 | ̶ | 450 ± 120 | ̶ | ̶ |

| Zn | 320 | 221 ± 71 | 404 ± 32 | ̶ | 300 ± 80 | ̶ | ̶ |

|

Element/ Compound |

Range From Table 3[*]wt % | Exolith | NASA | |||||

|

MGS-1 wt % |

MGS-1C wt% |

MGS-1S wt% |

JEZ-1 wt% |

MMS-1 wt% |

MMS-2 wt% |

JSC Mars-1 wt% |

||

| SiO2 | 42.05 ̶ 46.65 | 43.9 | 43.83 | 32.6 | 36.4 | 49.4 | 43.8 | 43.48 |

| TiO2 | 0.62 ̶ 1 | 0.46 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.4 | 1.09 | 0.83 | 3.62 |

| Al2O3 | 7.3 ̶ 10.07 | 12.84 | 10.42 | 9.59 | 8 | 17.10 | 13.07 | 22.09 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.32 ̶ 0.39 | - | - | - | - | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Fe2O3 | 4.28 ̶ 7.28 | - | 7.34 | 7.79 | - | 10.87 | 18.37 | 16.08 |

| FeO | 10.42 ̶ 26.2 | 10.60 | - | - | 11.9 | - | - | - |

| MnO | 0.31 ̶ 0.36 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.26 |

| MgO | 6 ̶ 9.3 | 14.81 | 13.47 | 11.51 | 25.6 | 6.08 | 6.66 | 4.22 |

| CaO | 5.7 ̶ 6.7 | 7.91 | 9.13 | 21.39 | 4.6 | 10.45 | 7.98 | 6.05 |

| Na2O | 1.6 ̶ 3.3 | 1.49 | 1.48 | 1.08 | 0.9 | 3.28 | 2.51 | 2.34 |

| K2O | 0.41 ̶ 0.48 | 0.29 | 1.44 | 0.32 | 0.3 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.7 |

| P2O5 | 0.83 ̶ 0.92 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.125 | 0.1 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.78 |

| SO3 | 4.94 ̶ 7.42 | - | - | - | - | 0.1 | 6.11 | 0.31 |

| LOI | - | 4.9 | 10.38 | 10.76 | 10 | - | - | 0 |

| Total | - | 97.48 | 98.11 | 95.61 | 98.4 | 99.24 | 100 | 100 |

| Quantity | Exolith | NASA | |||||

| MGS-1 | MGS-1C | MGS-1S | JEZ-1 | MMS-1 | MMS-2 | JSC Mars-1 | |

| D10 | 5.19 | 1.64 | 7.99 | 2.97 | 1.45 | 3.73 | 111.82 |

| D50 | 49.3 | 15.50 | 63.13 | 46.92 | 19.74 | 39.33 | 544.42 |

| D90 | 205.48 | 107.48 | 233.17 | 127.27 | 53.09 | 136.63 | 1703.80 |

| Ref. | Microorganism | Method | Soil | Environmental Conditions | Medium | Observed Results |

| [60] | Sporosarcina pasteurii | brick | LRS MRS [*] |

|

|

|

| [61] | Sporosarcina pasteurii | brick | LRS |

|

|

|

| [62] | Thraustochytrium striatum | grouting | MRS |

|

|

|

| [63] | Thraustochytrium striatum | grouting | MRS |

|

|

|

| Pathway | Speed | Resources | Byproducts | Conditions | Terraforming Phase | ||

| Before | During | After | |||||

| Ureolysis | Fast | Urea (urine), Ca²⁺ (regolith) |

NH₃ (manageable) | Aerobic/ Anaerobic | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ammonification | Slow | Amino Acids, O2 Ca²⁺ (regolith) |

NH₃ (manageable) | Aerobic/ Anaerobic | ✓ | ||

| Photosynthesis | Slow | CO₂ (atmosphere), light, water | O2 | Anaerobic | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Denitrification | Slow | Nitrates (regolith), organic carbon | N2 | Anaerobic | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Sulphate Reduction | Slow | Sulphates (regolith), organic carbon | H₂S (toxic) | Anaerobic | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Methanogenesis | Slow | CO₂, organic carbon | CH4 (usable) | Anaerobic | ✓ | ✓ | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).