Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

26 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tea Sample Processing

2.2. Oxygenation Treatment Method in Congou Black Tea Fermentation Process

2.3. Chemical Reagents

2.4. Sensory Evaluation

2.5. Chemical Composition Determination

2.6. TFs, TRs and TBs Determination

2.7. Chromatic Aberration Analysis of Tea Liquors

2.8. Analysis of Non-Volatile Metabolites in Black Teas Using UPLCMS/MS

2.8.1. Extraction of Non-Volatiles

2.8.2. UPLC Conditions and ESI-MS/MS

2.9. Analysis of Volatile Metabolites in Black Teas Using GC-MS

2.9.1. Extraction of Volatiles

2.9.2. Thermal Desorption

2.9.3. GC–MS Analysis

2.9.4. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Volatiles

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Different Treatments on Sensory Quality of Black Tea

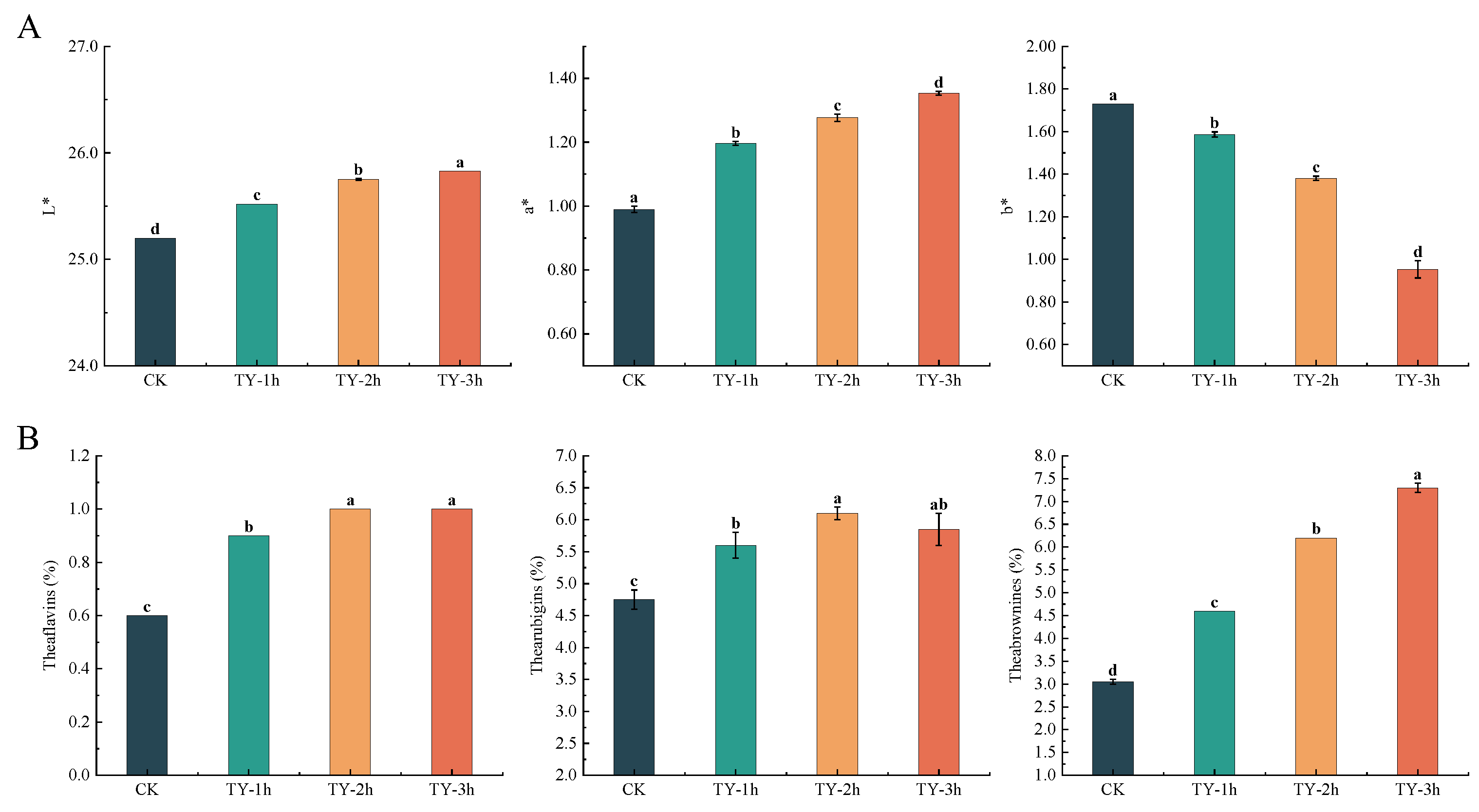

3.2. Effects of Different Treatments on the Chromatic Aberration of Tea Liquor

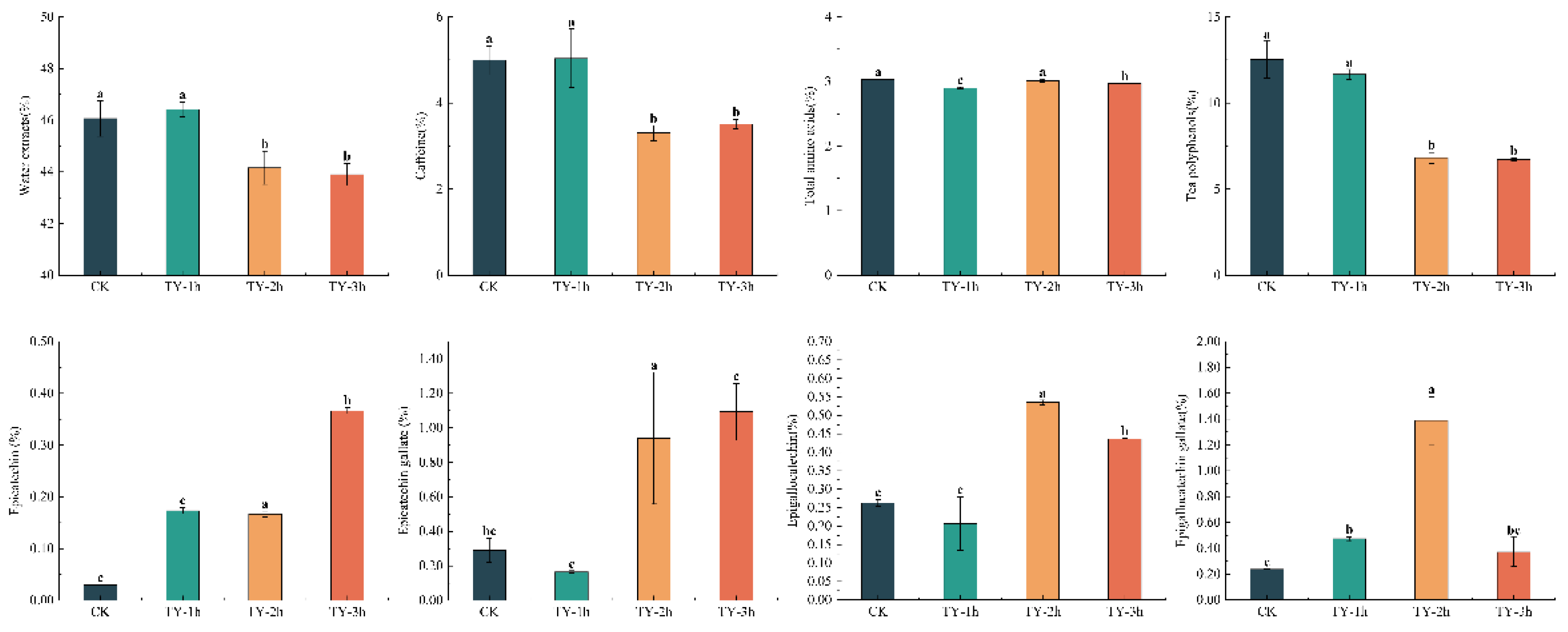

3.3. Effects of Different Treatments on the General Biochemistry Components

3.4. Effect of Increased Oxygen Treatment on Non-Targeted Metabolomics Analysis Based on UPLC-MS

3.4.1. Composition and Variation Trend of Non-Volatile Metabolites Across Four Different Treatments

3.4.2. Characterization of Differential Non-Volatile Metabolites of Four Different Treatments

3.4.3. Key Differential Non-Volatile Metabolites of Four Different Treatments

3.5. Effect of Increased Oxygen Treatment on Non-Targeted Metabolomics Analysis Based on GC-MS

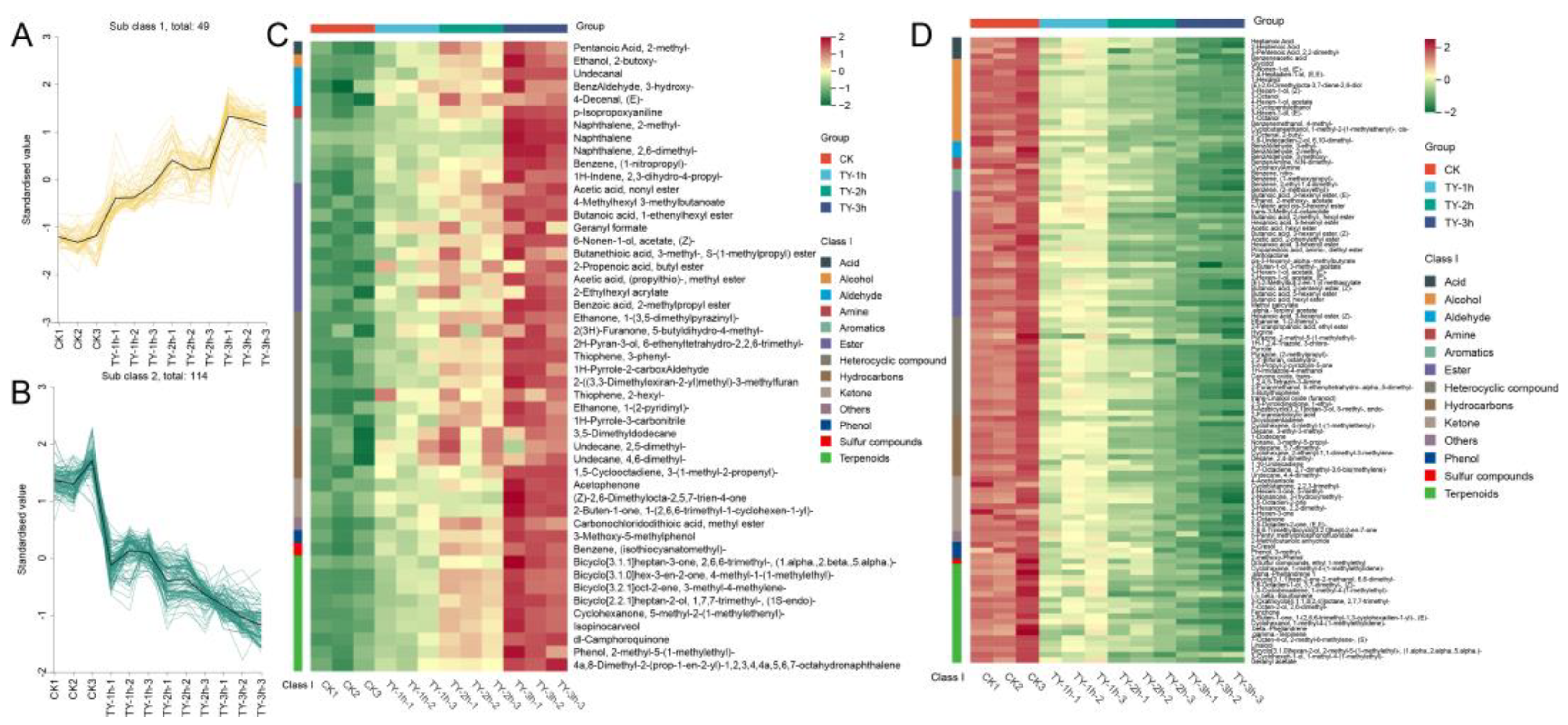

3.5.1. Composition and Variation Trend of Volatile Metabolites of Four Different Treatments

3.5.2. Key Differential Volatile Metabolites of Four Different Treatments

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y. Consumption of Coffee and Tea with All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Med 2022, 20, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, D.; Yang, L.; Hu, W.; Kuang, L.; Huang, Y.; Teng, J.; Liu, Y. Multi-Omics and Enzyme Activity Analysis of Flavour Substances Formation: Major Metabolic Pathways Alteration during Congou Black Tea Processing. Food Chemistry 2023, 403, 134263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Dong, C.; Lin, Z.; Teng, J. Black Tea Aroma Formation during the Fermentation Period. Food Chemistry 2022, 374, 131640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, N.F.; Mohamad, N.E.; Alitheen, N.B. Fermented Black Tea and Its Relationship with Gut Microbiota and Obesity: A Mini Review. Fermentation 2022, 8, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; Zeng, W.; Tong, X.; Feng, W.; Chen, Y.; Ni, D. The New Insight into the Influence of Fermentation Temperature on Quality and Bioactivities of Black Tea. LWT 2020, 117, 108646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, F.; Yang, Y.; Tu, Z.; Lin, J.; Ye, Y.; Xu, P. Oxygen-Enriched Fermentation Improves the Taste of Black Tea by Reducing the Bitter and Astringent Metabolites. Food Research International 2021, 148, 110613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Shen, S.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Hua, J.; Yuan, H. Novel Insight into the Effect of Fermentation Time on Quality of Yunnan Congou Black Tea. LWT 2022, 155, 112939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Wang, H.; Yuan, H.; Yin, P.; Wang, J.; Guo, G.; Jiang, Y. New Insights into the Effect of Fermentation Temperature and Duration on Catechins Conversion and Formation of Tea Pigments and Theasinensins in Black Tea. J Sci Food Agric 2022, 102, 2750–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R.; Vecchietti, A. Influence of Raw Material Moisture on the Synthesis of Black Tea Production Process. Journal of Food Engineering 2016, 173, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Ahmed, T.; Hossain, Md.S.; Dey, P.; Ahmed, S.; Hossain, Md.M. Optimization of the Factors Affecting BT-2 Black Tea Fermentation by Observing Their Combined Effects on the Quality Parameters of Made Tea Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM). Heliyon 2022, 8, e08948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, H.; Pollov Sarmah, P.; Devi, A.; Tamuly, P.; Karak, T. Changes in Major Catechins, Caffeine, and Antioxidant Activity during CTC Processing of Black Tea from North East India. RSC Advances 2021, 11, 11457–11467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntezimana, B.; Li, Y.; He, C.; Yu, X.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Z.; Ni, D. Different Withering Times Affect Sensory Qualities, Chemical Components, and Nutritional Characteristics of Black Tea. Foods 2021, 10, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Yu, X.; He, C.; Qiu, A.; Li, Y.; Shu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Ni, D. Withering Degree Affects Flavor and Biological Activity of Black Tea: A Non-Targeted Metabolomics Approach. LWT 2020, 130, 109535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gong, L.; Guo, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; … Luo, J. A novel integrated method for large-scale detection, identification, and quantification of widely targeted metabolites: Application in the study of rice metabolomics. Molecular Plant 2013, 6(6), 1769–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.Q.; Ma, W.J.; Shi, J.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Lv, H.P. Characterization of the key aroma compounds in Longjing tea using stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE)combined with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS), gas chromatography-olfactometry (GC-O), odor activity value (OAV), and aroma recombination. Food Research International 2020, 130, 108908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.L.; Liang, Y.R.; Gong, S.Y.; Gu, Z.R.; Zhang, L.Y.; Xu, Y.R. Studies on Relationship between Liquor Chromaticity and Organoleptic Quality of Tea. Journal of Tea Science 2002, 22(1), 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Yu, Q.; Shen, S.; Shan, X.; Hua, J.; Zhu, J.; Li, J. Non-targeted metabolomics and electronic tongue analysis reveal the effect of rolling time on the sensory quality and nonvolatile metabolites of congou black tea. Lwt-Food Science and Technology 169, 113971. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ho, C.T.; Zhou, J.; Santos, J.S.; Armstrong, L.; Granato, D. Chemistry and biological activities of processed Camellia sinensis teas: A comprehensive review. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2019, 18(5), 1474–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.S.; Li, N.; Zhong, X.G. Analysis of quality formation and catechin oxidation kinetics of congou black tea through natural fermentation. Food and Fermentation Industries. Food and fermentation industry 2023, 49(08), 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, D.; Peng, J.; Xie, D.; Lin, Z.; Dai, W. Metabolomic characterization of the chemical compositions of Dracocephalum rupestre Hance. Food Research International 2022, 161, Article111871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Qiu, X.; Ye, N.; Qian, J.; Wang, D.; Zhou, P.; Chen, M. Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole-orbitrap ultra high resolution mass spectrometry to quantitate nucleobases, nucleosides, and nucleotides during white tea withering process. Food Chemistry 2018, 266, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.J.; Liu, P.P.; Yin, J.F.; Wang, W.W.; Zhang, J.Y.; Wang, W.; Le, T.; Ni, D.J.; Jiang, H.Y. Dynamic changes in volatile compounds of shaken black tea during its manufacture by GC x GC-TOFMS and multivariate data analysis. Foods 2022, 11(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, J.M.; Fang, J.T.; Zhu, X.Y.; Sun, J.J.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Huang, C.W. Analysis of catechins and aromatic of Keemun black tea during processing based on metabolic spectrum technology[J]. Science and Technology of Food Industry 2016, (09), 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Ho, C.T.; Zhou, J.; et al. Chemistry and biological activities of processed Camellia sinensis teas: a comprehensive review[J]. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2019, 18(5), 1474–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zeng, L.; Liao, Y.; et al. Enzymatic reaction-related protein degradation and proteinaceous amino acid metabolism during the black tea (Camellia sinensis) manufacturing process[J]. Foods 2020, 9(1), 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Yang, Z. Understanding different regulatory mechanisms of proteinaceous and non-proteinaceous amino acid formation in tea (Camellia sinensis) provides new insights into the safe and effective alteration of tea flavor and function[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2020, 60(5), 844–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).