Submitted:

25 June 2025

Posted:

25 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Relevance of the Topic and Research Motivation

1.2. Analysis of the Latest Research and Publications

1.3. Aim, Objectives, Object and Subject of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- accuracy of system operation in accordance with a given reference trajectory;

- -

- computation time;

- -

- energy consumption.

3. Results

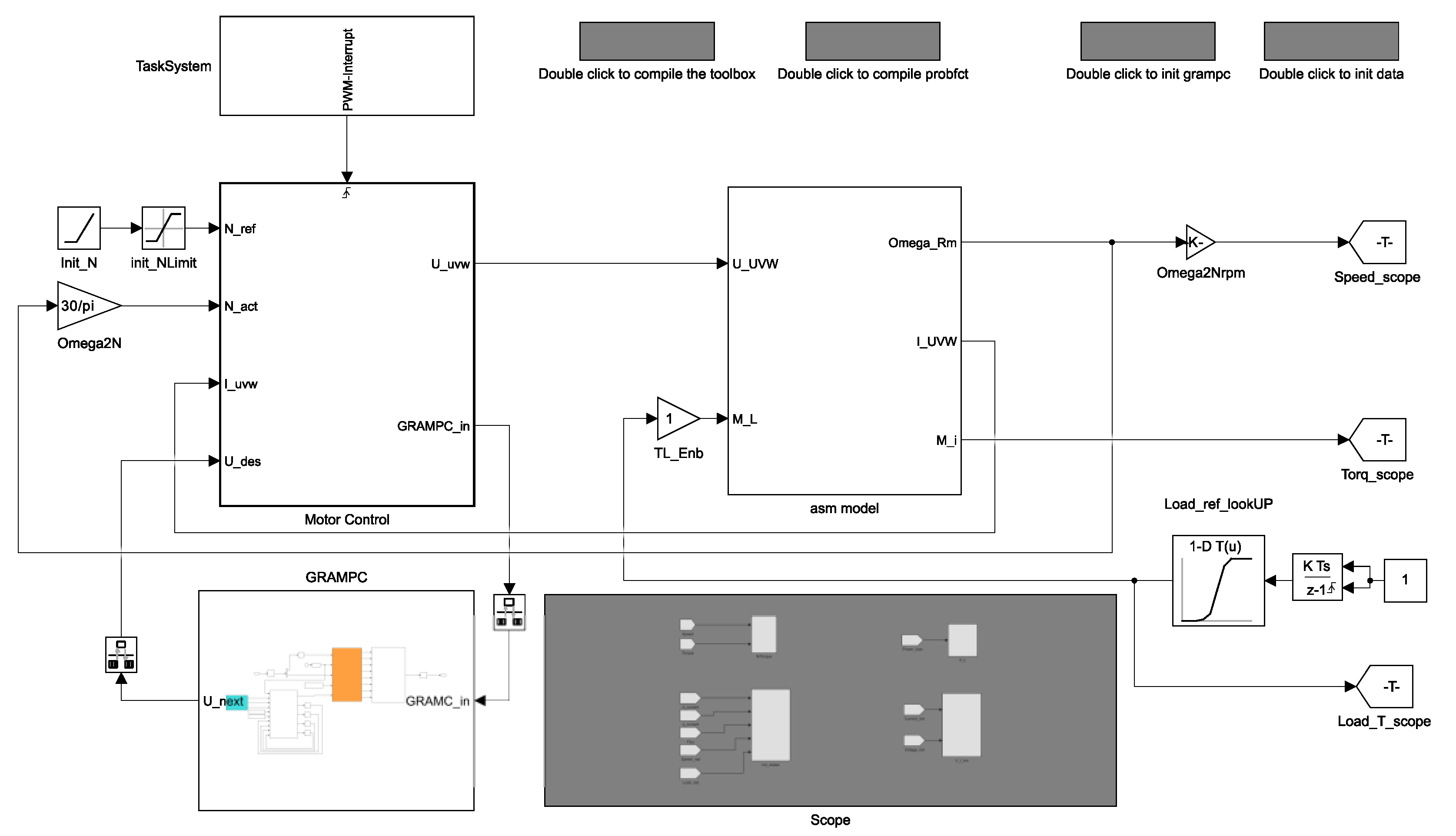

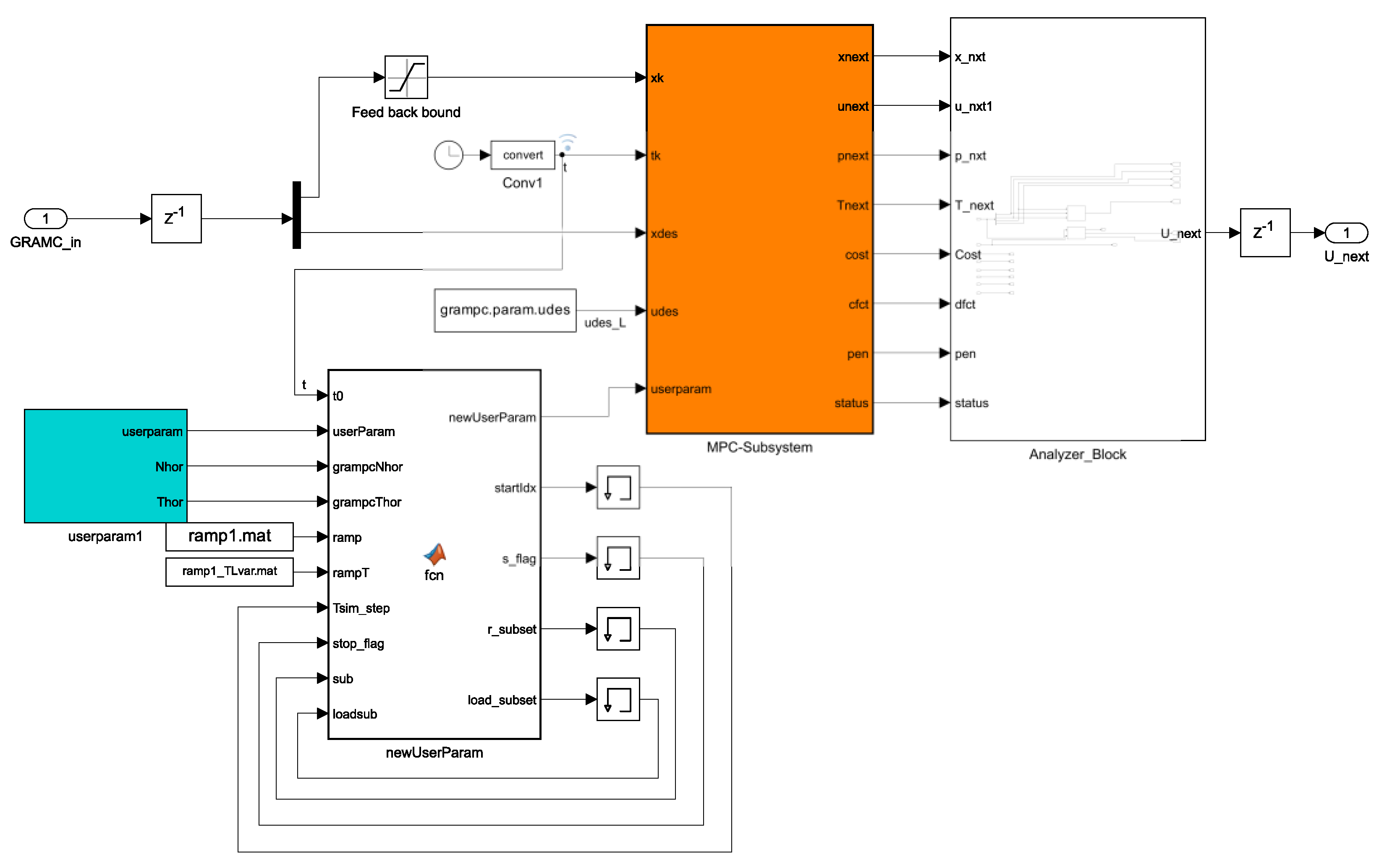

3.1. Computer Model

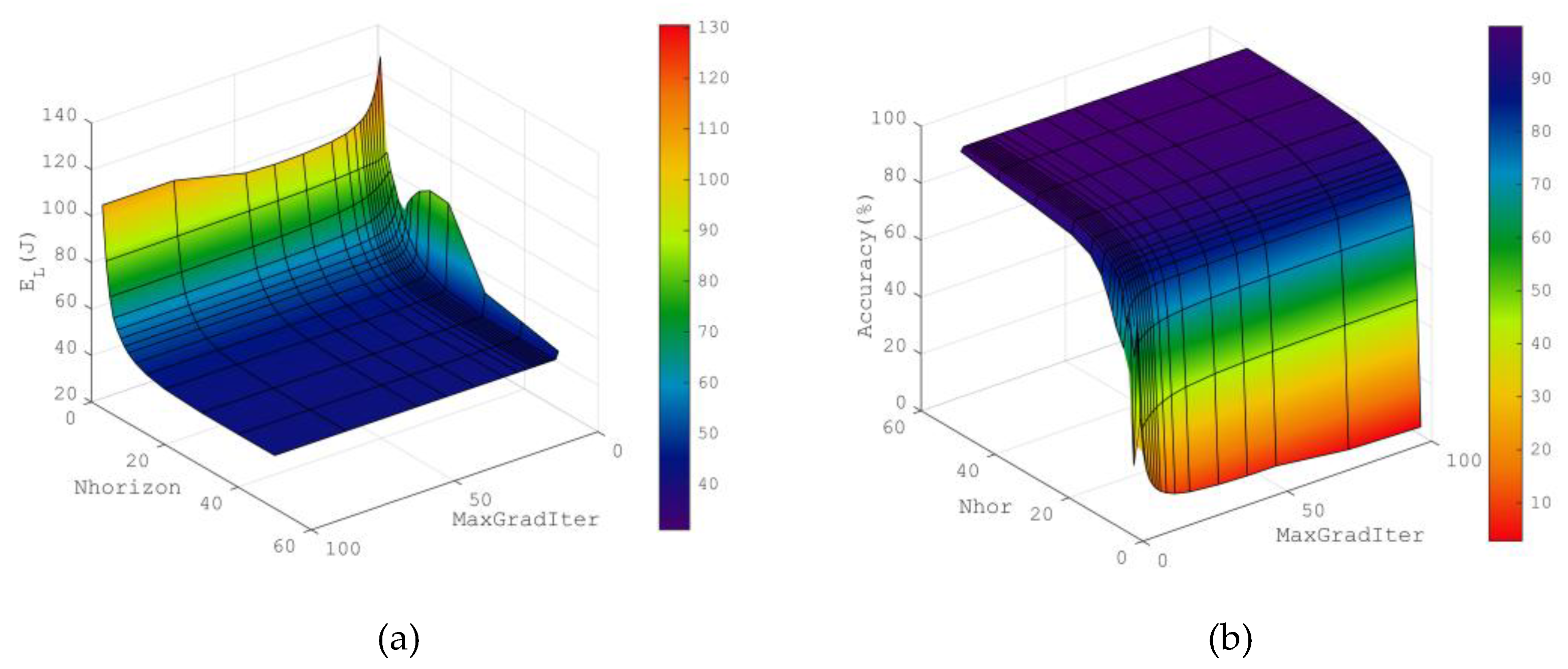

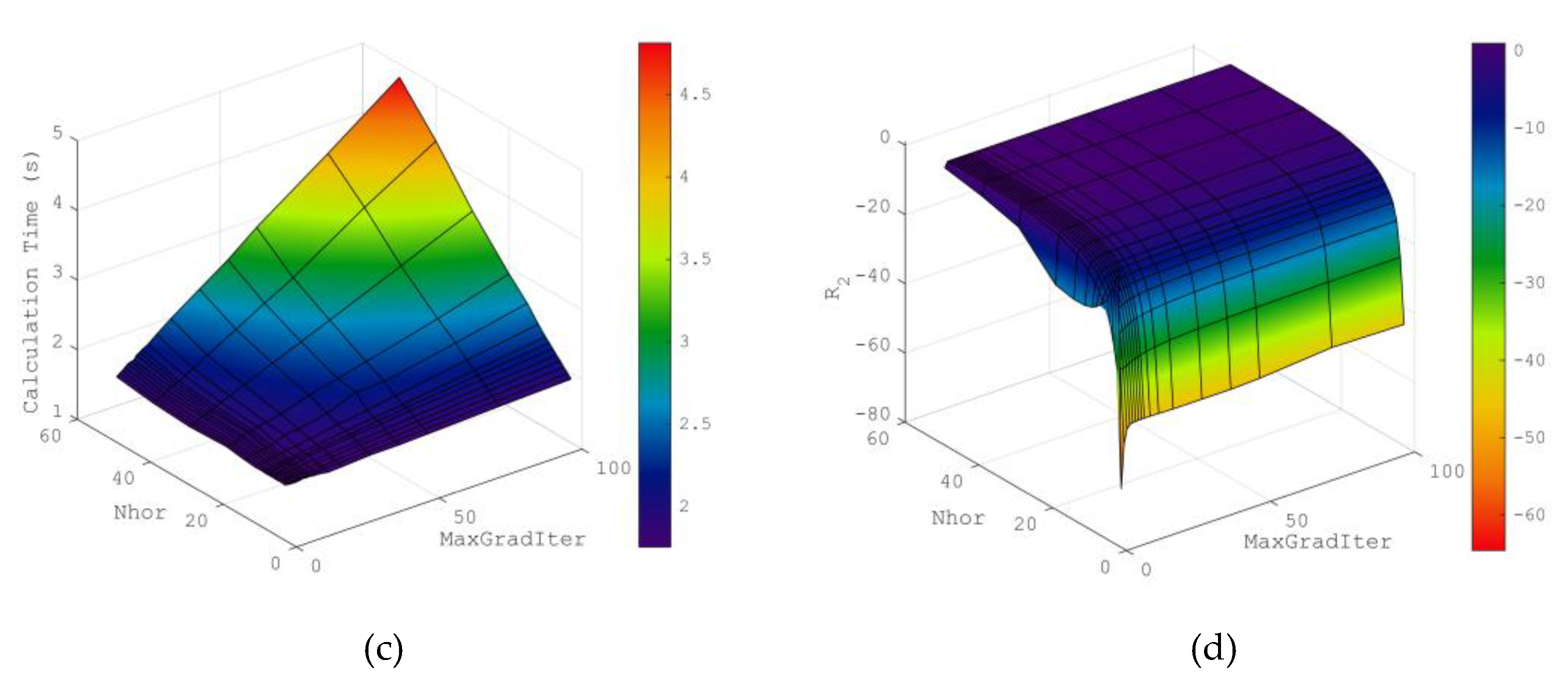

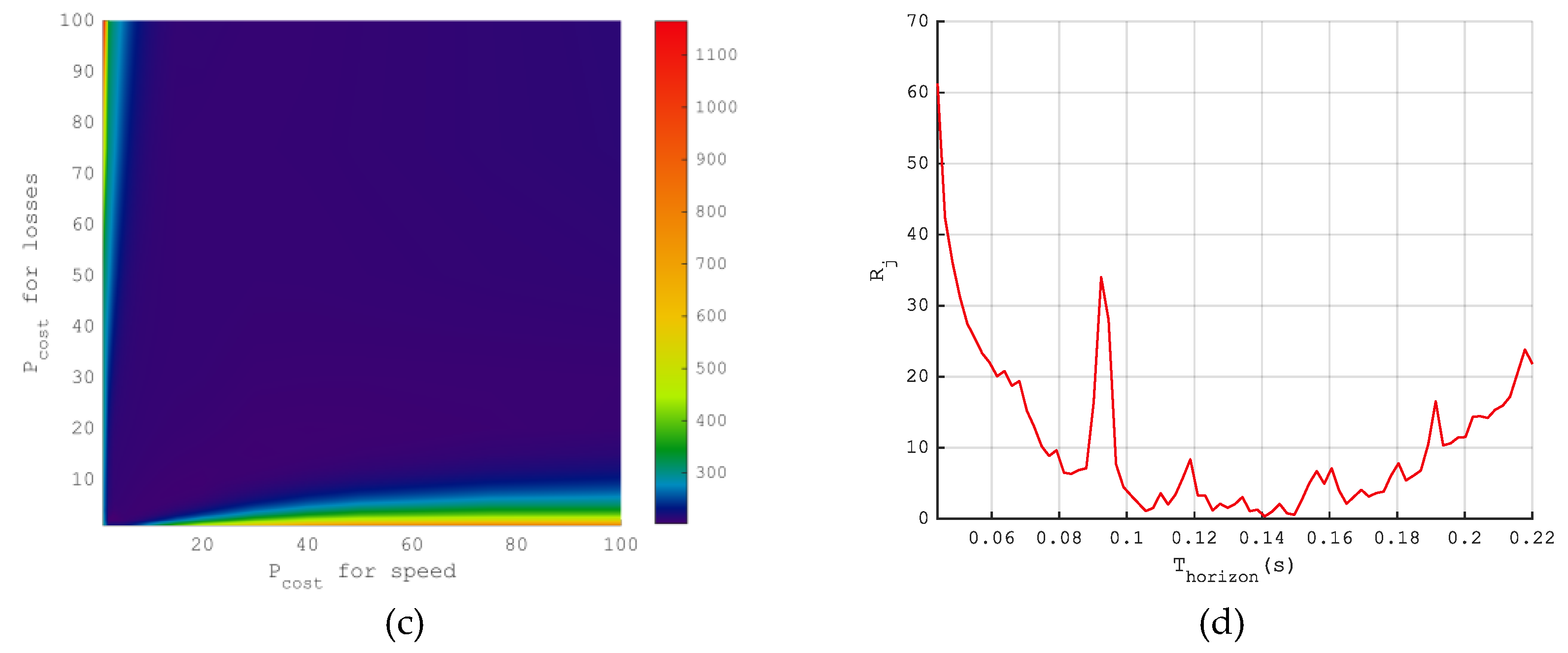

3.2. Results of the Analysis of the Influence of the Prediction Algorithm Parameters

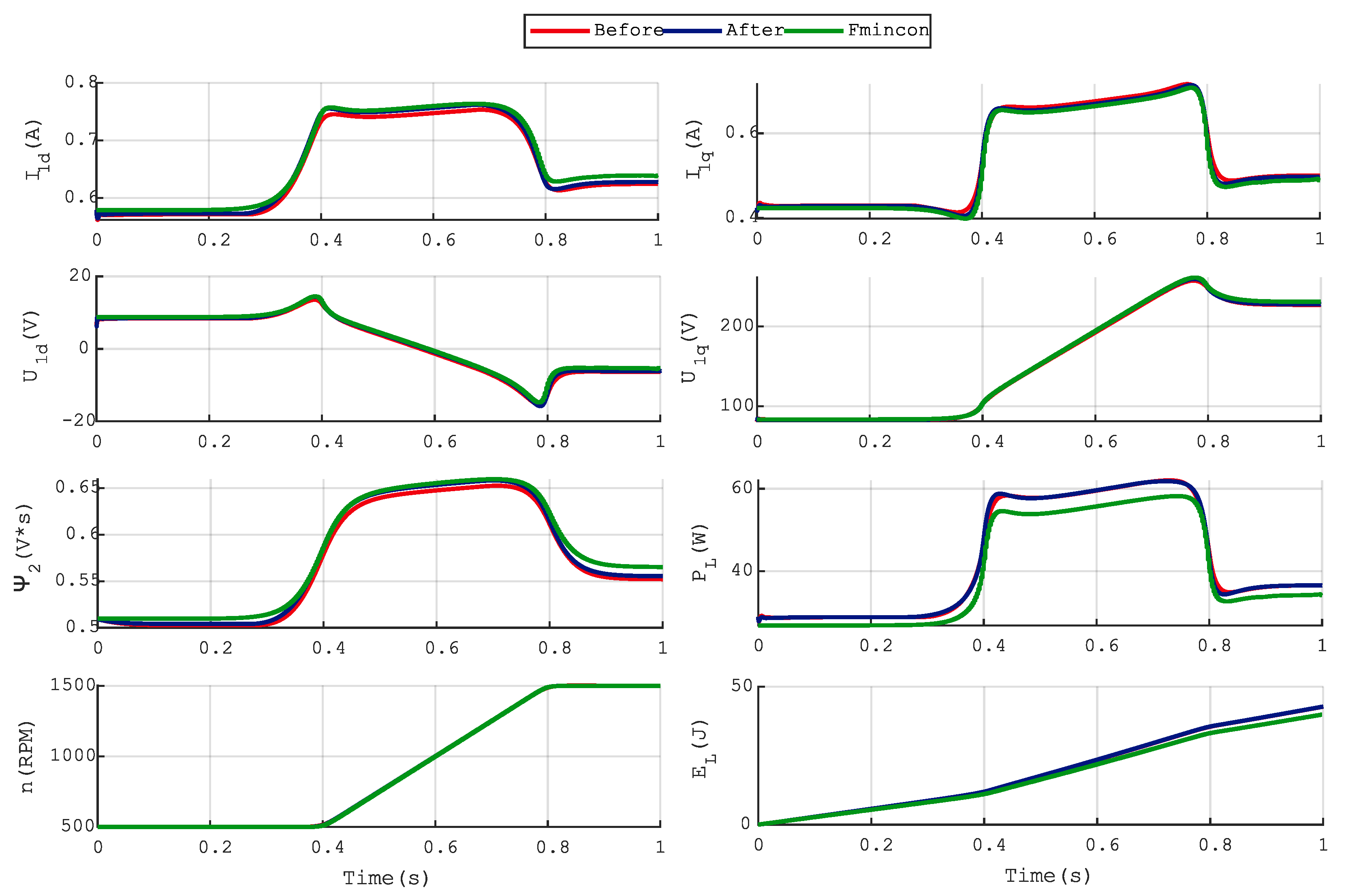

3.3. Results of Applying the Taxonomic Approach and Simulation Experiment

4. Discussion and Prospects for Further Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Koval, V.; Kryshtal, H.; Udovychenko, V.; Soloviova, O.; Froter, O.; Kokorina, V.; Veretin, L. Review of mineral resource management in a circular economy infrastructure. Mining of Mineral Deposits 2023, 17(2), 61–70. [CrossRef]

- Farrag, M.; Lai, C.S.; Darwish, M.; Taylor, G. Improving the Efficiency of Electric Vehicles: Advancements in Hybrid Energy Storage Systems. Vehicles 2024, 6 (3), 1089–1113. [CrossRef]

- Rjabtšikov, V.; Rassõlkin, A.; Kudelina, K.; Kallaste, A.; Vaimann, T. Review of Electric Vehicle Testing Procedures for Digital Twin Development: A Comprehensive Analysis. Energies 2023, 16 (19), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Pandey, R. A Review on Motor and Drive System for Electric Vehicle”, In: Bohre, A.K., Chaturvedi, P., Kolhe, M.L., Singh, S.N. (eds) Planning of Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems, Electric Vehicles and Microgrid. Energy Systems in Electrical Engineering, Springer, Singapore, 2022; pp. 601–628. [CrossRef]

- Statista: Estimated number of electric vehicles in use worldwide between 2016 and 2023. available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1101415/number-of-electric-vehicles-by-type/#statisticContainer (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Gallert, B.; Choi, G.; Jing, X.; Lee, K.; Son, Y. Maximum efficiency control strategy of PM traction machine drives in GM hybrid and electric vehicles. In 2017 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Cincinnati, OH, USA, 01-05 October 2017; pp. 566–571. [CrossRef]

- Piriienko, S.; Ammann, U.; Neuburger, M.; Bertele, F.; Röser, T.; Balakhontsev, A.; Neuberger, N.; Cheng, P.-W. Influence of the control strategy on the efficiency of SynRM-based small-scale wind generators”, In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 13-15 February 2019; pp.280–285. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Ma, H.; Zhu, G.; Luo, J. Improved MTPA and MTPV optimal criteria analysis based on IPMSM nonlinear flux-linkage model. Energies 2024, 17 (14), 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Sinchuk, O.; Strzelecki, R.; Beridze, T.; Peresunko, I.; Baranovskyi, V.; Kobeliatskyi, D.; Zapalskyi, V. Model studies to identify input parameters of an algorithm controlling electric supply/consumption process by underground iron ore enterprises. Mining of Mineral Deposits 2023, 17 (3), 93–101. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, R.D.; Yang, S.M. Efficiency–Optimized Flux Trajectories for Closed–Cycle Operation of Field-Orientation Induction Machine Drives. In Conference Record of the 1988 IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 02-07 October 1988; pp. 457–462. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, R.D.; Yang, S.M. AC Induction Servo Sizing for Motion Control Applications via Loss Minimizing Real–Time Flux Control IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 1992, 28 (3), 589–593. [CrossRef]

- Klenke, F.; Hofmann, W. Energy-Efficient Control of Induction Motor Servo Drives With Optimized Motion and Flux Trajectories”. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications, Birmingham, UK, 30 August - 01 September 2011; pp. 1–7, URL: ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6020629.

- Weis, R.; Gensior, A. A Model-Based Loss-Reduction Scheme for Transient Operation of Induction Machines. In 2016 18th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications (EPE’16 ECCE Europe), Karlsruhe, Germany, 05-09 September 2016; pp. 1–8, . [CrossRef]

- Alitasb, G.K. Integer PI, Fractional PI and Fractional PI data trained ANFIS Speed Controllers for Indirect Field Oriented Control of Induction Motor. Heliyon 2024, 10 (18), 1–15, . [CrossRef]

- Nandy, S.; Das, S.; Pal, A. Online Golden Section Method based Loss Minimization Scheme for Direct Torque Controlled Induction Motor Drive. In 2018 8th IEEE India International Conference on Power Electronics (IICPE), Jaipur, India, 13-15 December 2018; pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, A.; Jena, R. Loss model based controller of fuzzy DTC driven induction motor for electric vehicles using optimal stator flux. e-Prime – Advances in Electrical Engineering, Electronics and Energy 2023, 6, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Englert, T.; Graichen, K. Nonlinear model predictive torque control and setpoint computation of induction machines for high performance applications. Control Engineering Practice 2020, 99, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Janisch, G.; Kugi, A.; Kemmetmüller, W. A high-performance model predictive torque control concept for induction machines for electric vehicle applications. Control Engineering Practice 2024, 153, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Brix, A.; Muller, V.; Hofmann, W. Energy Efficient Predictive Rotor Flux Control of Induction Machines in Autonomous Driving Electric Vehicles. In: 2019 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), Detroit, MI, USA, 19-21 June 2019; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Abdelati, R.; Mimouni, M.F. Optimal control strategy of an induction motor for loss minimization using Pontryaguin principle. European Journal of Control 2019, 49, 94–106. [CrossRef]

- Meleshko, Y.; Raskin, L.; Semenov, S.; Sira, O. Methodology of probabilistic analysis of state dynamics of multi-dimensional semi-Markov dynamic systems. Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies 2019, 6 (4 (102), 6–13. [CrossRef]

- Moskalenko, V.; Kharchenko, V.; Semenov, S. Model and Method for Providing Resilience to Resource-Constrained AI-System. Sensors 2024, 24 (18), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Q.; Dong, S.; Xiao, A. Research on Simplified Design of Model Predictive Control. Actuators 2025, 14 (4), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Jaguemont, J.; Darwiche, A.; Bardé, F. Model Predictive Control Using an Artificial Neural Network for Fast-Charging Lithium-Ion Batteries. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2025, 16 (4), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, L. Physics-Informed Neural Network-Based Nonlinear Model Predictive Control for Automated Guided Vehicle Trajectory Tracking. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2024, 15 (10), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Diachenko, G.; Schullerus, G.; Dominic, A.; Aziukovskyi, O. Energy-efficient predictive control for field-orientation induction machine drives. Naukovyi Visnyk Natsionalnoho Hirnychoho Universytetu 2020, 6, 61–67. [CrossRef]

- Schullerus, G. Modellprädiktive dynamisch energieeffiziente Betriebsführung einer Asynchronmaschine. In Proceedings of the SPS IPC DRIVES 2014, Nürnberg, 25.11.2014 - 27.11.2014., 366–374.

- GRAMPC documentation version 2.2. Available online: https://sourceforge.net/p/grampc/blog/2019/10/grampc-v22/ (accessed on 05 June 2025).

- Samorodov, B.V. Modification of the taxonomic method with regard to the competence of experts in the rating of banks. Bulletin of the Ukrainian Academy of Banking 2011, 2 (31), 62–67. URL: https://essuir.sumdu.edu.ua/bitstream-download/123456789/57800/5/Samorodov_Modyfikatsiia_taksonometrychnoho_metodu.pdf;jsessionid=987554DEB0E25827A65559A506529F62 (in Ukrainian).

- Diachenko, G. Model predictive control for energy-efficient operation of an induction machine in transient behavior: PhD dissertation, Dnipro, Ukraine, 185 p. (in Ukrainian).

- Dominic, A., Schullerus, G., Winter, M. Optimal Flux and Current Trajectories for Efficient Operation of Induction Machines. 2019 20th International Symposium on Power Electronics (Ee), Novi Sad, Serbia, 2019, 1–6. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

PN Zp nN |

370 W 2 1370 rpm |

TN JM |

2.59 Nm 22·10-4 kg·m2 |

|

R1 R2 |

27.8 Ω 20 Ω |

Lσ Lμ |

0.142 H 0.88 H |

|

P1 P2 P3 |

-0.669 3.606 -6.622 |

P4 P5 P6 |

4.415 -0.743 0.754 |

| C1 | 0.0013 | C2 | 0.5778 |

| 52.36 rad/s 500 rpm | 157 rad/s 1500 rpm |

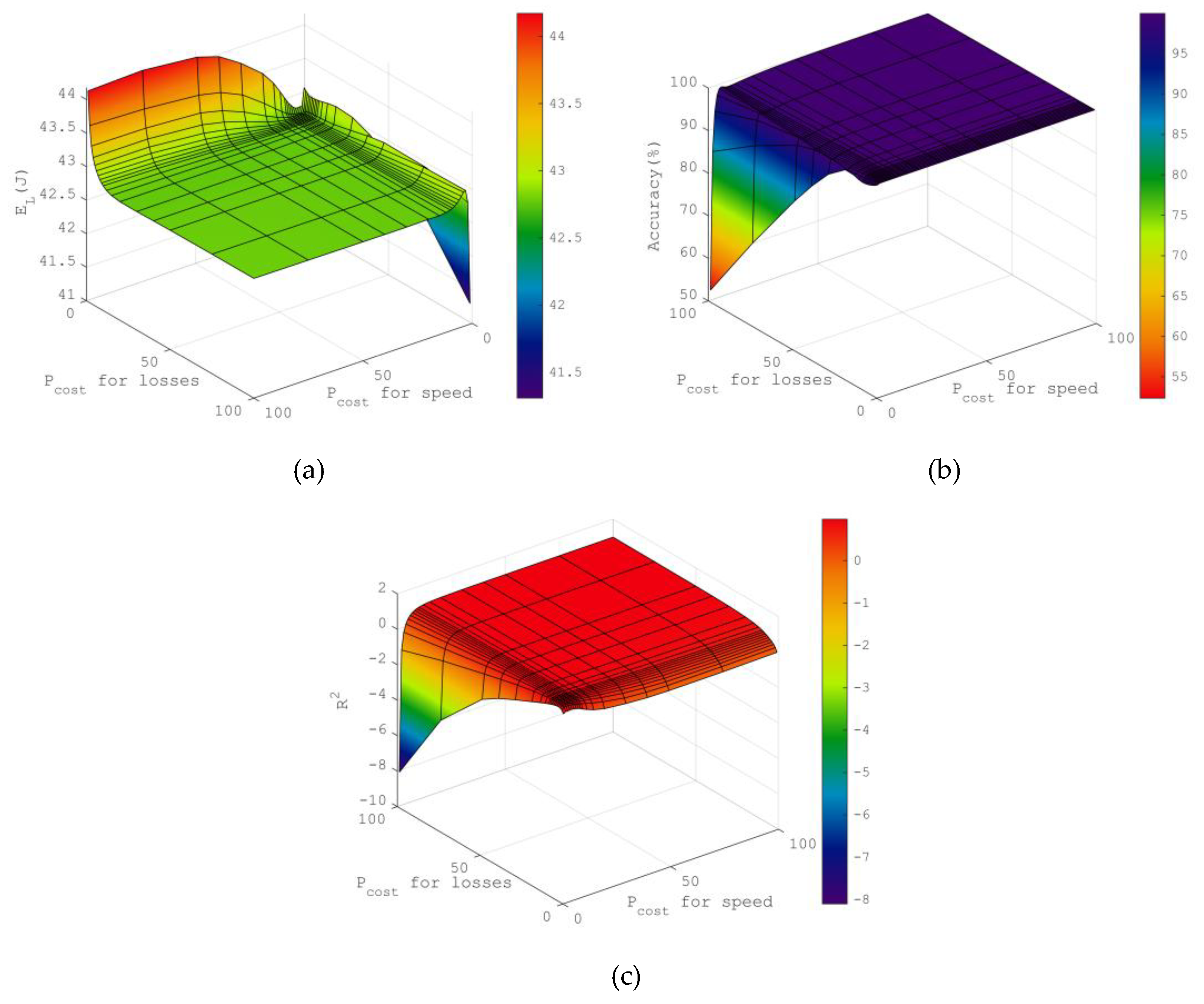

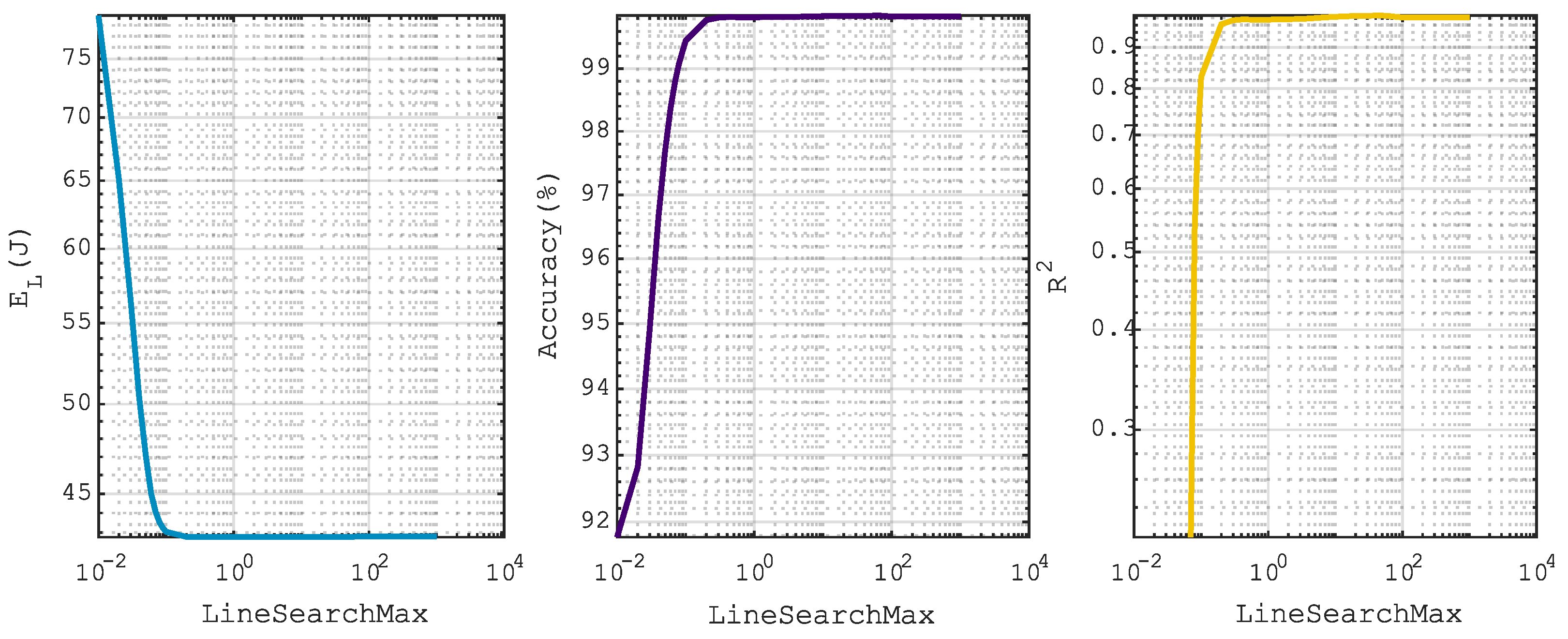

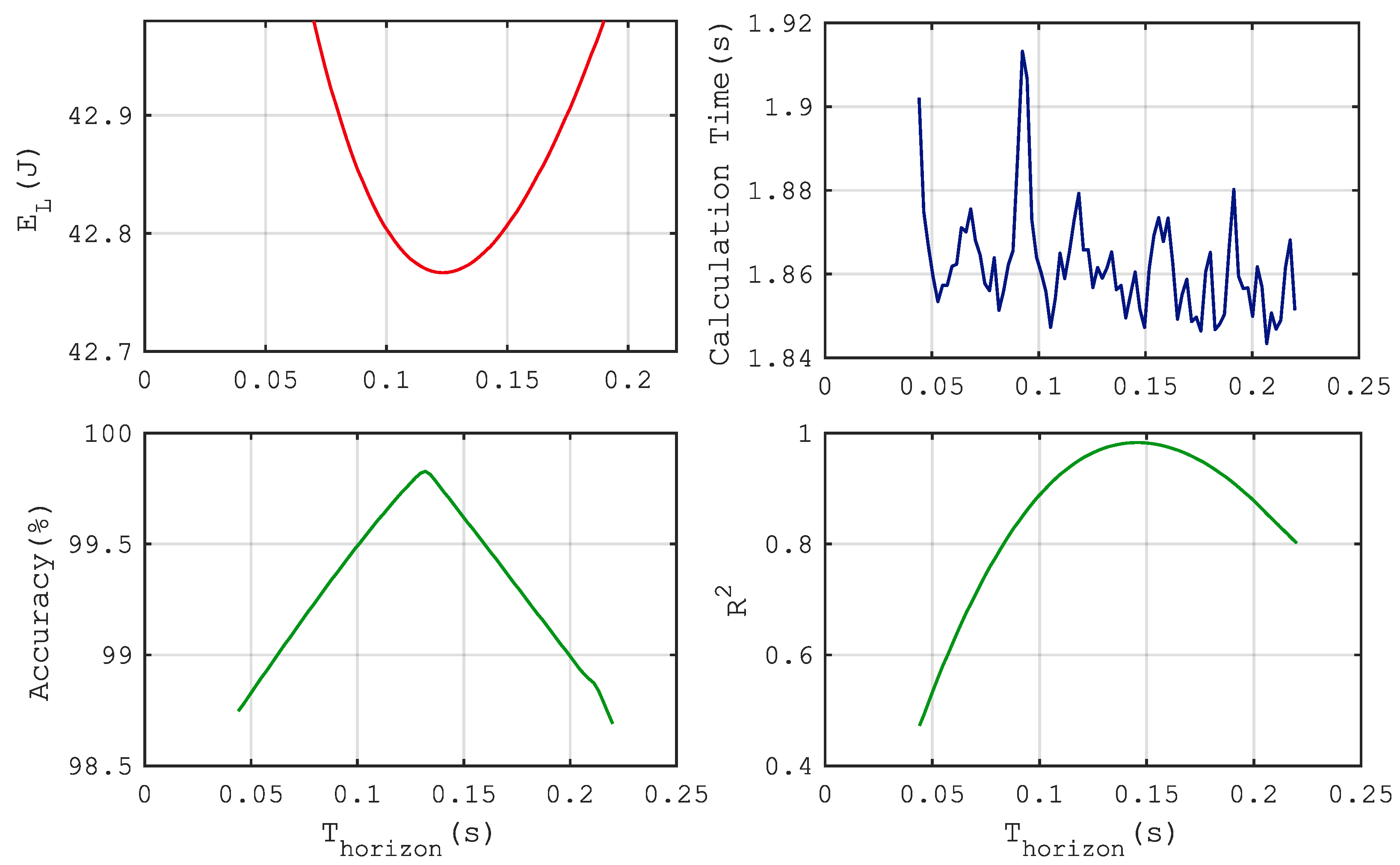

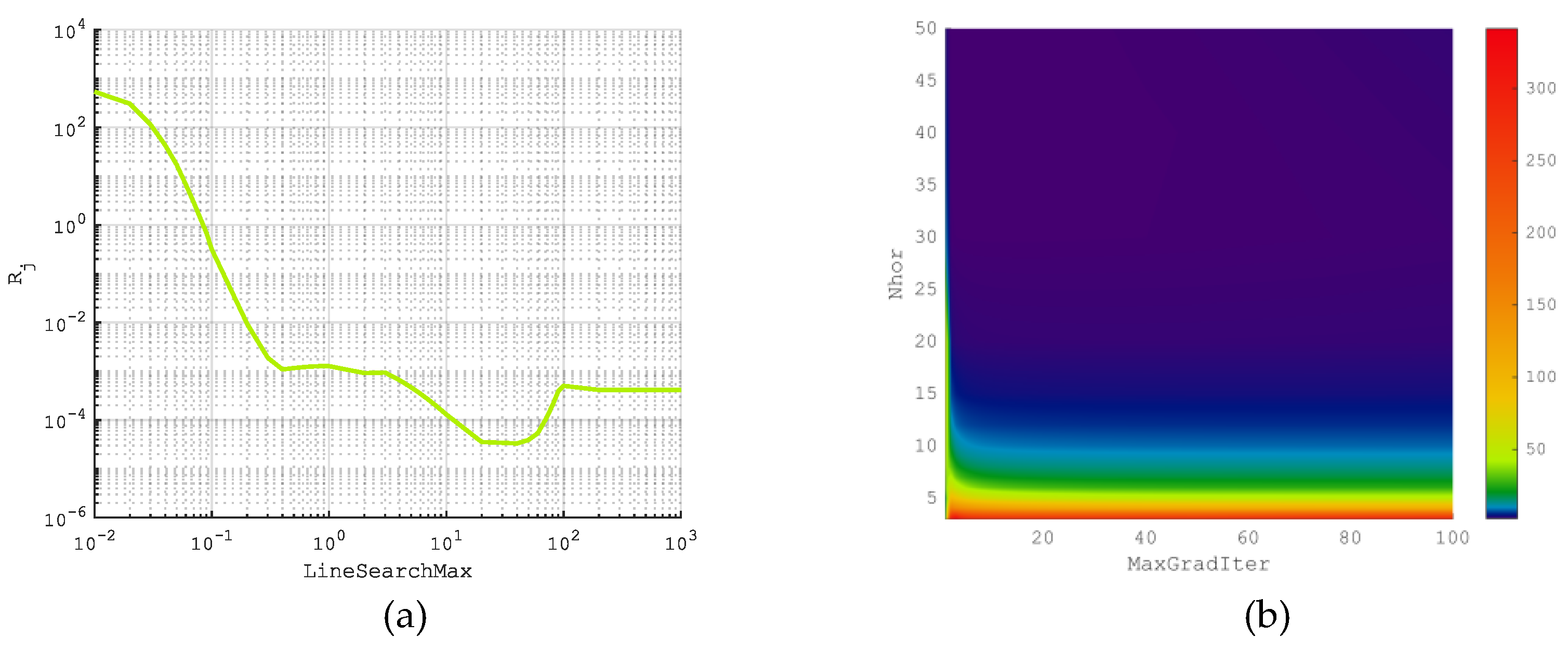

| Nhorizon + NMaxGradIter | PCosts | Thorizon | LineSearchMax | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EL (J) | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Ns, Accuracy (%) | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Ts, Calculation time (s) | 0.01 | - | 1 | 0 |

| R2 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Parameter | Initial guess | Optimal values |

| Nhorizon | 50 | 50 |

| NMaxGradIter | 2 | 2 |

| PСost (loss) | 10 | 2 |

| PСost (speed) | 5 | 2 |

| Thorizon | 0.1302 | 0.1408 |

| LineSearchMax | 0.5 | 40 |

| Parameter | Before | After |

| I1d (A) | 97.54 | 99.01 |

| I1q (A) | 98.89 | 99.61 |

| Ψ2 (V*s) | 97.72 | 99.05 |

| n (rpm) | 100.00 | 100.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).