1. Introduction

Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA) remains a major diagnostic challenge, especially when the tumor exhibits an infiltrative, non-mass-forming pattern [

1,

2]. The diagnosis is further complicated in patients with morbid obesity, which may preclude advanced imaging such as MRI [

3]. Paraneoplastic hypercoagulability, manifesting as idiopathic DVT, is a well-described but frequently underappreciated early sign in hepatobiliary malignancies [

4]. Here we present a case where all these factors contributed to a delayed diagnosis and fatal outcome, with final diagnosis and extent established only at autopsy.

2. Case Presentation

A 56-year-old male (BMI 43 kg/m²), with a recent history of idiopathic DVT (December 2024, treated with rivaroxaban), presented on 13 February 2025 for rapidly progressive, painless jaundice, pruritus, and dark urine. Physical examination confirmed intense jaundice without abdominal tenderness or palpable organomegaly.

Laboratory findings: Marked cholestatic syndrome (ALT 411 U/L, AST 205 U/L, ALP 488 U/L, GGT 699 U/L, total bilirubin 8.9 mg/dL), mild inflammatory markers (CRP 3.9 mg/dL), and negative viral and autoimmune panels (HAV, HBV, HCV, HEV, ANA, AMA, ANCA).

Imaging:

13.02: Abdominal ultrasound identified only gallbladder microlithiasis, without bile duct dilation (

Figure 1).

14.02: First ERCP showed normal bile ducts and papilla, no strictures or filling defects (

Figure 2A).

Following days: Laboratory cholestasis decreased minimally, but jaundice persisted.

Repeat ultrasound revealed discrete hilar ductal dilation.

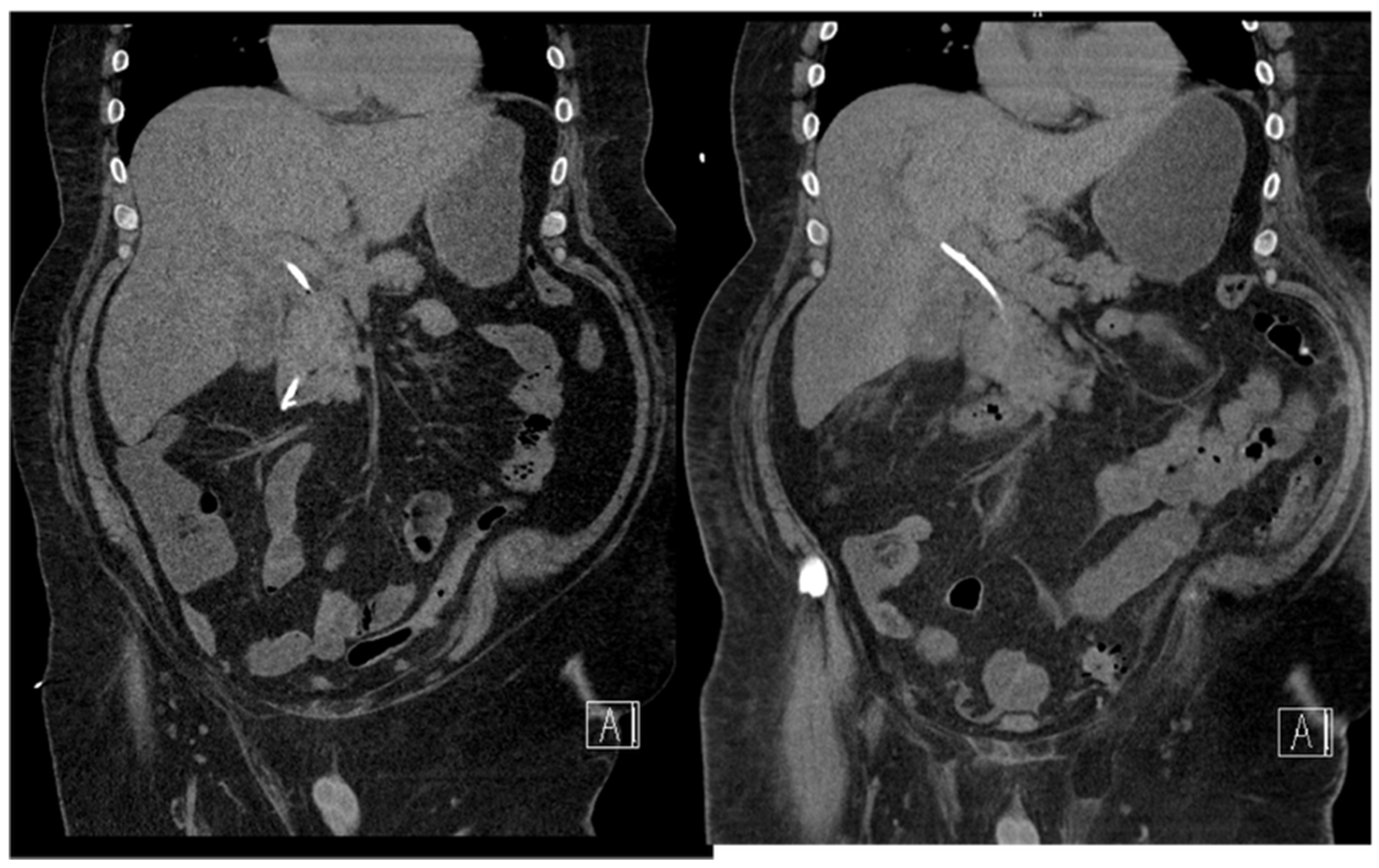

18.02: Contrast-enhanced CT demonstrated only mild hilar bile duct dilation, with no mass or lymphadenopathy (

Figure 3).

18.02: Longitudinal endoscopic ultrasound did not demonstrate any focal mass lesions; only a slight thickening of the bile duct wall was observed.

18.02: Second ERCP again found no obstructive lesion; a 10Fr/10cm plastic stent was placed empirically (

Figure 2B). No clinical or biochemical improvement was observed.

Serial sonography showed no new findings post-stenting.

Further workup: Like already mentioned, all usual causes of diffuse liver disease (viral, autoimmune, metabolic) were excluded.

25.02: A third ERCP was performed. Fluoroscopy showed a chain of short, irregular strictures proximally (

Figure 5). Digital cholangioscopy visualized irregular, friable mucosa at the hilum (

Figure 6). Multiple biopsies were obtained, and a new stent was placed.

Figure 1.

Abdominal ultrasound (13.02.2025): gallbladder microlithiasis, no bile duct dilation.

Figure 1.

Abdominal ultrasound (13.02.2025): gallbladder microlithiasis, no bile duct dilation.

Figure 2.

First ERCP (14.02.2025): normal bile ducts, no strictures or filling defects.

Figure 2.

First ERCP (14.02.2025): normal bile ducts, no strictures or filling defects.

Figure 3.

CT scan (18.02.2025): discrete hilar duct dilation, no visible mass.

Figure 3.

CT scan (18.02.2025): discrete hilar duct dilation, no visible mass.

Figure 4.

Second ERCP (18.02.2025): no obstruction, plastic stent inserted empirically.

Figure 4.

Second ERCP (18.02.2025): no obstruction, plastic stent inserted empirically.

Figure 5.

Third ERCP (25.02.2025): chain of short, irregular hilar strictures, suspected infiltration.

Figure 5.

Third ERCP (25.02.2025): chain of short, irregular hilar strictures, suspected infiltration.

Figure 6.

Digital cholangioscopy (25.02.2025): irregular, friable mucosa at hilar confluence.

Figure 6.

Digital cholangioscopy (25.02.2025): irregular, friable mucosa at hilar confluence.

Histology: Biopsies suggested poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma but were inconclusive for full characterization ante-mortem.

The patient was discharged clinically stable, pending multidisciplinary tumor board evaluation.

1.03: The patient was urgently readmitted with worsening jaundice, hypotension, fever, lactic acidosis, AKI, and profound sepsis biomarkers (bilirubin 20 mg/dL, CRP 34 mg/dL, PCT >100 ng/mL).

- ○

CT at readmission: No significant interval change, plastc stent in itu, no evidence of ductal dilation or masses (

Figure 4).

-

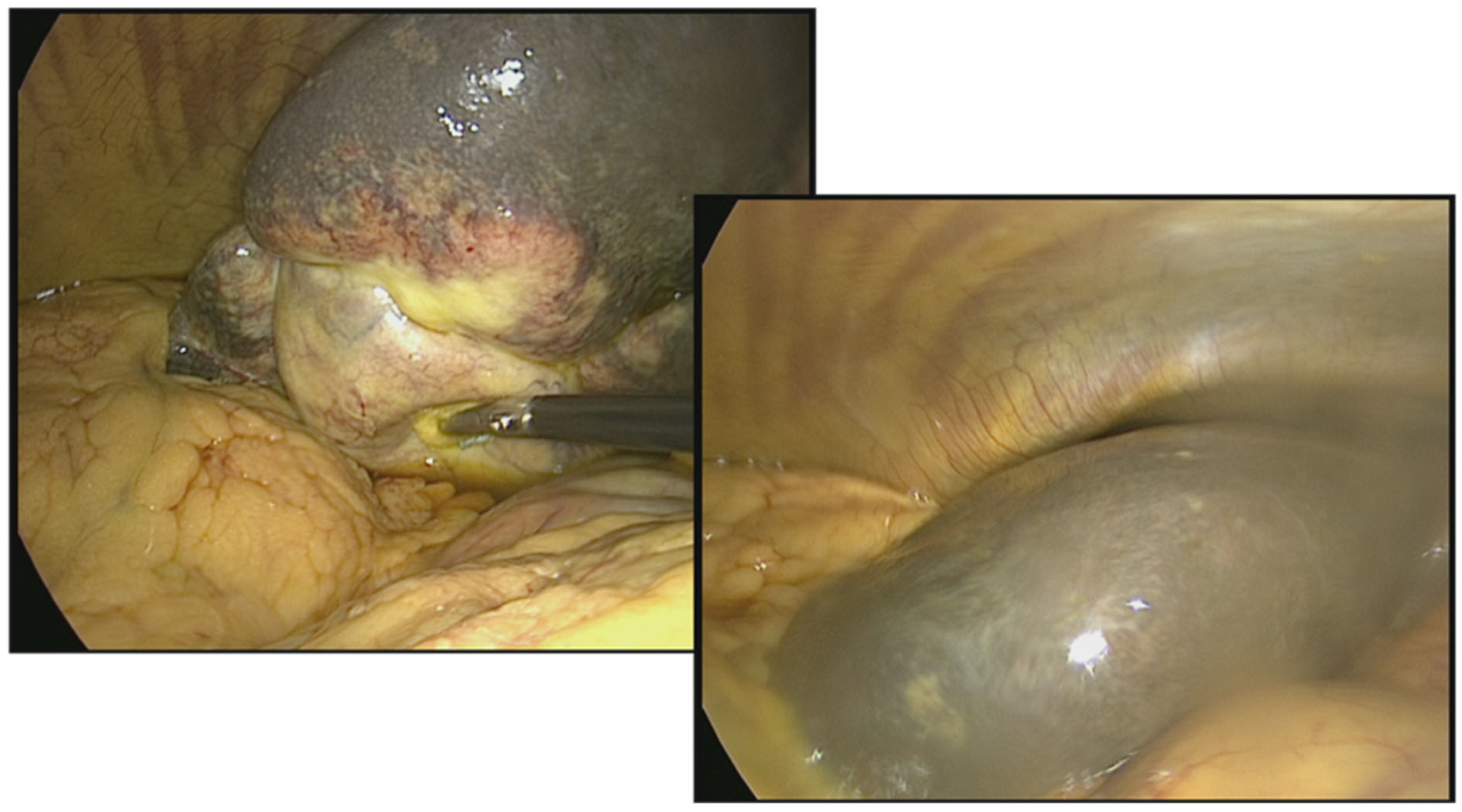

4.03: Diagnostic laparoscopy excluded cholecystitis and cirrhosis; the liver appeared soft, non-cirrhotic, the gallbladder was normal, and no peritonitis or abscess was identified.

Despite maximal therapy, the patient died on 5 March 2025.

Autopsy:

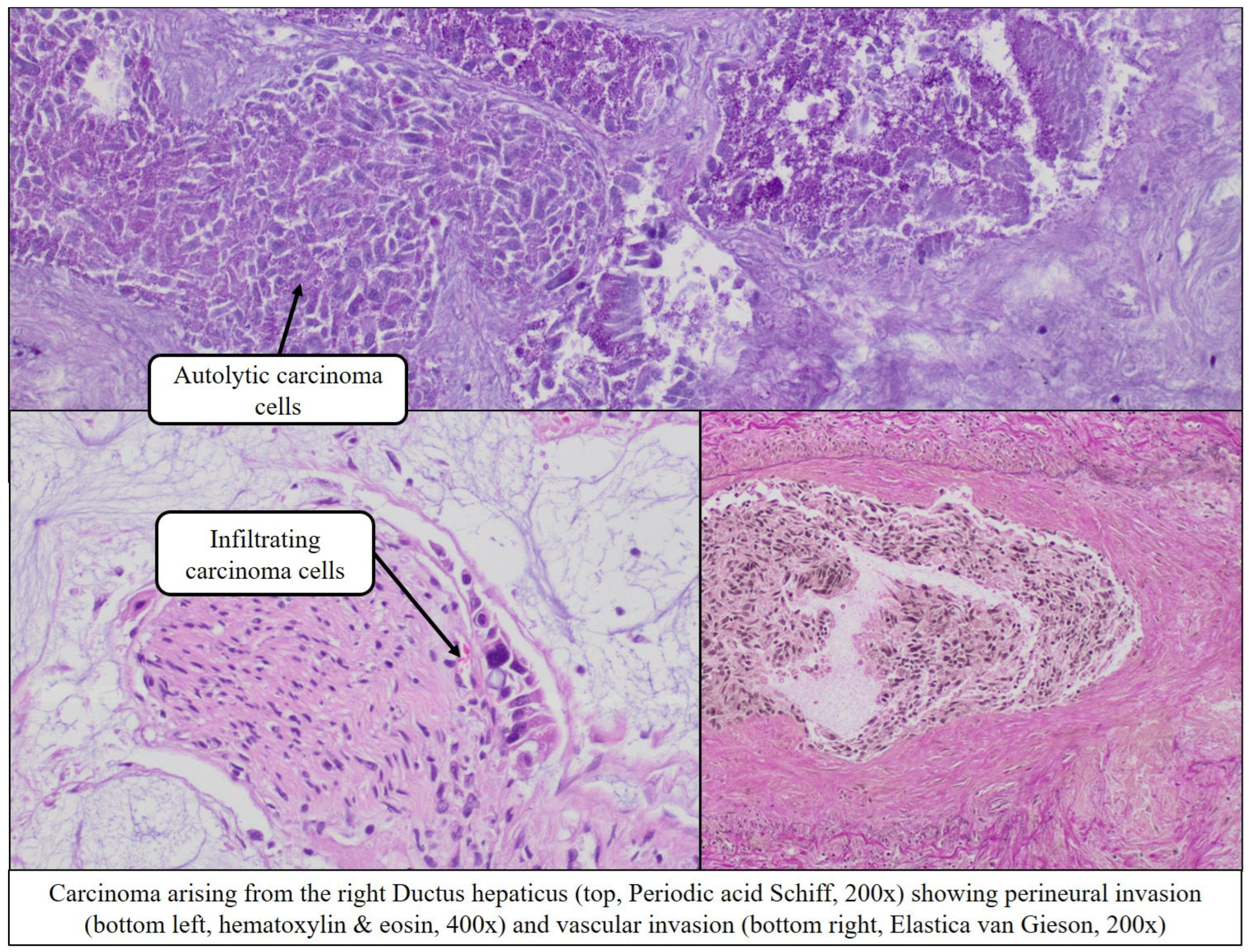

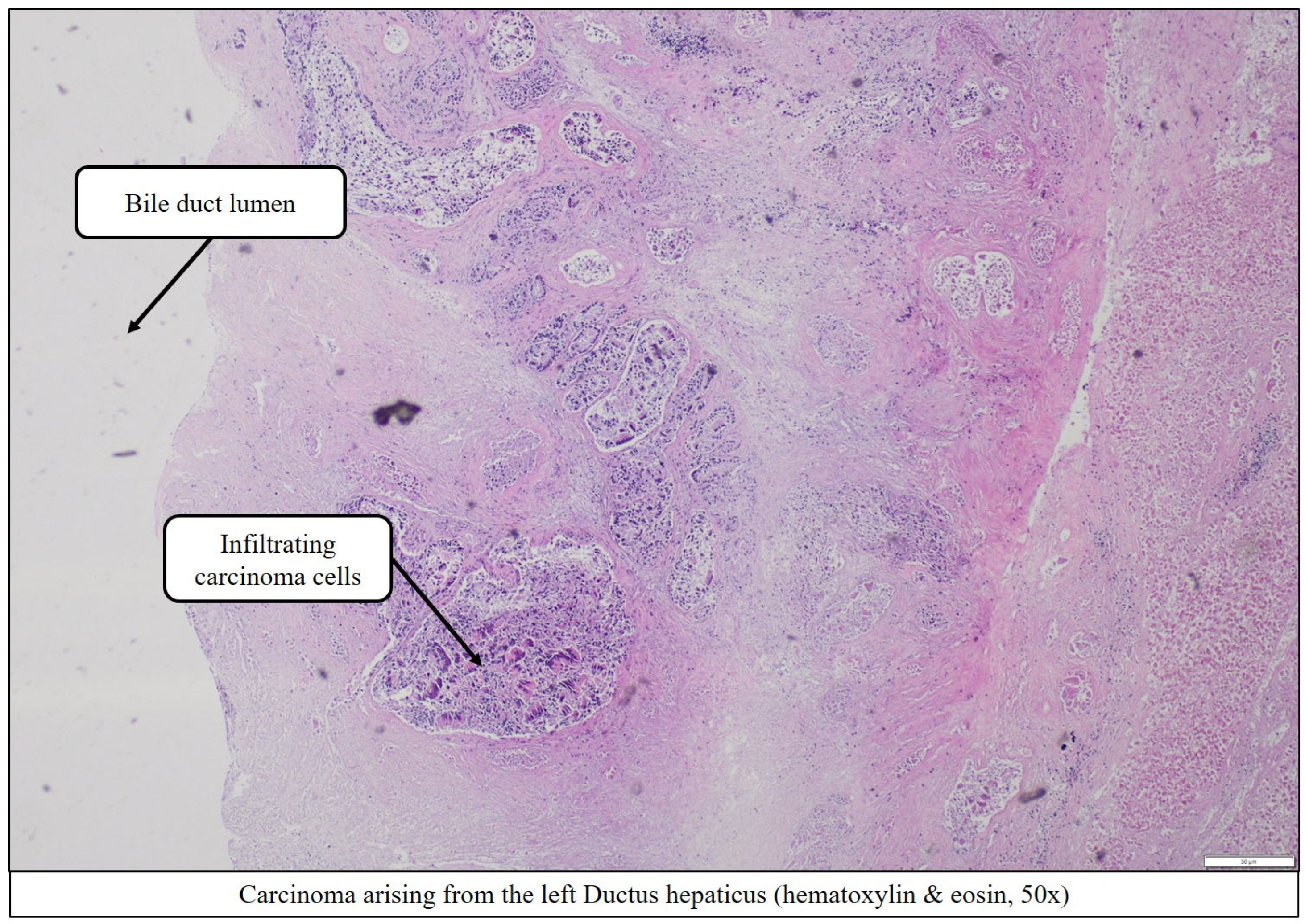

Extensive periductal tumor infiltration of the right and left hepatic ducts (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8),

Marked regional lymph node metastases (

Figure 9),

Right-sided pulmonary thromb- and tumorembolism (

Figure 10).

All histopathological images are from autopsy specimens (March 2025).

No liver abscess or intra-abdominal infection was identified.

Thus, the definitive diagnosis in our patient was acute liver failure with clinically direct hyperbilirubinemia due to mucin-producing adenocarcinoma in the area of the right, left, and common hepatic duct:

With infiltration into adjacent soft tissue and neighboring liver parenchyma

With regional lymph node metastases (5/5; apN2)

With lymphangiosis carcinomatosa (L1)

With local hemangioinvasion (including larger branches of the hepatic artery/portal vein) and evidence of tumor cells in the area of the right-sided pulmonary artery embolism (V1)

With perineural infiltration (Pn1)

- ○

UICC Classification (8th edition, 2020):

- ▪

apT3, apN2, apM0, GX, L1, V1, Pn1

- ○

Stage IVA T3, N2, M0 (UICC/AJCC 8th edition)

- ○

Bismuth-Corlette Classification Type IV

3. Discussion

This case underscores several key diagnostic and management challenges inherent to perihilar, periductal-infiltrating cholangiocarcinoma (pCCA). The fatal outcome, despite the use of advanced endoscopy and a multidisciplinary approach, prompts critical reflection on what was done, what could have been improved, and how current evidence should guide clinicians facing similar diagnostic dilemmas.

4. Diagnostic Delay and Imaging Pitfalls

Periductal-infiltrating pCCA is notorious for its insidious onset and the paucity of clear imaging features in early or even intermediate disease [

1,

2,

3]. Our patient underwent a classic diagnostic cascade:

initial ultrasound and CT scans were essentially normal, showing only minimal hilar ductal dilation. These findings are not unusual; recent studies confirm that in 20–30% of pCCA cases, cross-sectional imaging and even ERCP may fail to reveal a definite mass or stricture, especially in the periductal-infiltrating subtype [

2,

4].

A major limitation in our case was the

inability to perform MRI/MRCP due to morbid obesity. MRI is generally superior to CT for evaluating subtle ductal wall thickening and periductal spread [

3,

5], and its absence undoubtedly delayed tissue diagnosis. In obese patients, clinicians should be prepared to escalate early to alternative modalities, such as digital cholangioscopy, when MRI is technically unfeasible.

5. ERCP and the Timing of Advanced Endoscopy

The patient underwent

two standard ERCPs and one EUS with empiric stenting before a third, dagnostic ERCP with cholangioscopy was performed. This sequence reflects real-world practice but also highlights a common pitfall: “diagnostic inertia,” or the repetition of standard procedures despite a lack of new findings [

6].The lack of clue findings at longitudinal EUS did not initially raise suspicion of a malignant etiology, as it is well recognized that similar EUS features can also be seen in inflammatory processes such as primary sclerosing cholangitis or chronic bacterial cholangitis [

2,

5,

6]. This diagnostic ambiguity is supported by recent studies indicating that EUS has limited sensitivity for detecting periductal-infiltrating or diffuse perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, especially in the absence of a discrete mass lesion [

2,

5].

Guidelines and recent meta-analyses strongly suggest that if two ERCPs fail to explain persistent cholestasis,

early referral for digital cholangioscopy should be prioritized [

7,

8]. Had cholangioscopy been performed earlier (e.g., at the second ERCP), tissue diagnosis may have been obtained days sooner, potentially allowing for more rapid MDT planning and oncologic workup [

7,

8,

9].

However, it must be acknowledged that even with direct visualization,

patchy tumor infiltration can yield false negatives on forceps biopsy. Thus, a negative or inconclusive biopsy should not delay referral to an MDT or repeat sampling if clinical suspicion remains high [

7].

6. Paraneoplastic Clues and Missed Opportunities

An often-overlooked aspect is the

history of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). This event, occurring two months prior to jaundice, should have raised suspicion for an underlying malignancy. Multiple population-based studies recommend a structured cancer screening protocol in patients >50 years with idiopathic DVT, as up to 10% may harbor occult cancer, including cholangiocarcinoma [

10,

11]. In hindsight, earlier cross-sectional imaging or tumor marker assessment might have expedited the diagnosis. The presence of DVT also raises important considerations for the selection and timing of surgical or interventional procedures, as these patients are at increased risk for both thrombosis and bleeding [

12].

7. Multidisciplinary Management and System Delays

The patient was discharged in stable condition after tissue diagnosis,

pending discussion at a multidisciplinary tumor board (MDT). While MDT review is best practice for all biliary tract cancers [

13], this interval between diagnosis and oncology planning may be critical in aggressive, infiltrative disease. There is increasing support for

“rapid” pathways that immediately refer newly diagnosed or highly suspected pCCA cases to hepatobiliary surgery and oncology, rather than waiting for routine outpatient MDT scheduling [

13,

14]. It is a matter of speculation whether this would have altered the fatal trajectory in our patient, but a shorter time to MDT review and staging workup could have allowed for earlier consideration of palliative or pre-emptive interventions (e.g., metal stenting, early antibiotics).

Biliary Sepsis and Limitations of Stenting

The clinical deterioration was characterized by severe sepsis, lactic acidosis, and anuria,

despite broad-spectrum antibiotics and empiric biliary stenting. Latest studies highlight that plastic stents may provide suboptimal drainage in diffuse, multifocal pCCA [

9,

15]. Incomplete biliary decompression is a major risk factor for post-ERCP cholangitis and rapid progression to multiorgan failure, even in the absence of microbiological confirmation [

15,

16]. This was not the case in our patient, at least by no evidence of contrast retainement. Some centers advocate for early use of self-expandable metal stents (SEMS) or bilateral drainage in complex hilar strictures, but evidence remains mixed [

15]. One of the main issues was that the possibility of a biliary neoplasm was not considered until late in the clinical course, and the use of a metal stent was not discussed prior to obtaining a definitive diagnosis.

In our patient, the lack of clinical improvement after two stents should have prompted urgent re-evaluation and perhaps more aggressive or alternative drainage strategies.

Laparoscopy was performed to exclude surgical sources of sepsis and revealed a soft, non-cirrhotic liver, ruling out hepatic decompensation and acute cholecystitis. This demonstrates the utility of minimally invasive exploration in critically ill patients with diagnostic uncertainty [

17].

8. Autopsy Findings and Lessons Learned

The

autopsy revealed the true extent of disease, with periductal infiltration, hemangioinvasion and massive regional nodal spread. Additionally a right-sided pulmonary embolism was revealed. Histologically there where sign of resorption and neovascularization, thus indicating weeks- to month-old history of thromboembolism. As clinically described the patient did show bilateral deep vein thrombosis at an older stage with signs of organization and revascularization. Strikingly however, there were also nests of carcinoma cells within the pulmonary emboli showing a direct involvement of the tumor distinguishing it from a conventional thromboembolism originating from the deep vein thrombosis —. Such emboli are an under-recognized but well-described cause of sudden death in biliary tract cancer. The entity is seldom diagnosed ante-mortem and highlights the aggressive biology of advanced pCCA [

18,

19]. Moreover, the patient has been constantly anticoagulated since December 2024 and never showed any signs of pulmonary insufficiency.

Reflecting on the clinical course, it is uncertain if

earlier diagnosis or MDT review would have definitively changed the fatal outcome given the advanced (Stage IVA disease), multifocal, aggressive, and infiltrative tumor. However, expedited tissue diagnosis, more aggressive biliary drainage, and closer inpatient monitoring after diagnosis may have reduced the risk of catastrophic sepsis or allowed for timely transition to palliative care [

14,

20]. Importantly, the

role of autopsy remains invaluable in confirming cause of death and providing critical feedback for clinical teams.

Recent literature strongly emphasizes the diagnostic difficulties faced in cases of periductal-infiltrating perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, such as the one presented here. Recent contemporary cohort studies and expert reviews have demonstrated that this tumor subtype is particularly prone to delayed recognition, primarily due to its diffuse, non-mass-forming pattern and the lack of distinctive features on conventional imaging, endoscopic, or even repeated ERCP studies [

1,

2,

3,

5,

6]. Sensitivity for early detection remains limited: cross-sectional imaging, EUS, and standard cytology frequently fail to reveal definitive malignant changes, especially when MRI is not feasible [

3,

5]. Even digital cholangioscopy, though superior for direct mucosal visualization and targeted biopsies, can yield false negatives due to patchy, submucosal infiltration [

6]. These diagnostic issues, as also seen in our patient, are repeatedly highlighted in the latest guidelines and meta-analyses, which now advocate for early escalation to advanced endoscopy and suggest early multidisciplinary team discussion to improve outcomes [

2,

5,

13]. Nevertheless, delays in diagnosis remain common and are associated with poorer prognoses in large-scale studies [

11].

9. Key Takeaways for Clinical Practice

Early escalation to digital cholangioscopy is essential in unresolved, unexplained cholestasis, particularly when MRI is unavailable or inconclusive.

Structured cancer screening should be considered in patients with idiopathic DVT, especially in those over 50 or with other risk factors.

Repeated negative ERCPs should not delay referral to advanced endoscopy or MDT.

Plastic stenting may be insufficient in diffuse, infiltrative pCCA; alternative drainage or SEMS should be considered when feasible.

MDT and fast-track pathways are crucial to reduce delays between tissue diagnosis and oncology management, though the impact on outcomes in advanced cases remains debated.

Autopsy remains essential for learning and quality assurance in complex oncological cases.

In conclusion, this patient’s tragic outcome serves as a reminder that, even with all the remarkable advances in modern medicine, few situations are ever purely black or white; instead, we are constantly confronted with innumerable shades of grey.

10. Figure Legends

Figure 11.

Histopathology (autopsy): Regional lymph node metastasis within a conglomerate of several infiltrated lymph nodes located next to the large extrahepatic bile ducts (hematoxylin & eosin, 50x).

Figure 11.

Histopathology (autopsy): Regional lymph node metastasis within a conglomerate of several infiltrated lymph nodes located next to the large extrahepatic bile ducts (hematoxylin & eosin, 50x).

Figure 12.

Histopathology (autopsy): Pulmonary embolism in the lower lobe (left, hematoxylin & eosin, 100x) and upper lobe of the right lung (right, hematoxylin & eosin, 100x) with evidence of tumor embolism.

Figure 12.

Histopathology (autopsy): Pulmonary embolism in the lower lobe (left, hematoxylin & eosin, 100x) and upper lobe of the right lung (right, hematoxylin & eosin, 100x) with evidence of tumor embolism.

References

- Banales, J.M.; Marin, J.J.G.; Lamarca, A.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: the next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020, 17, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.; Gores, G.J. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013, 145, 1215–1229.e1. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J.M.; Visser, B.C. Cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Clin North Am. 2024, 104, 1281–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorana, A.A. Cancer-associated thrombosis: Updates and controversies. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2012, 2012, 626–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauro, A.; Mazza, S.; Scalvini, D.; Lusetti, F.; et al. The Role of Cholangioscopy in Biliary Diseases. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023, 13, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navaneethan, U.; Hasan, M.K.; Lourdusamy, V.; et al. Single-operator cholangioscopy and targeted biopsies in the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015, 82, 608–614.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portillo-Romero, A.; et al. Acute pulmonary tumour embolism and right systolic dysfunction in a hidden intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2023, 7, ytad29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luca, T.; et al. Intraductal Papillary Neoplasms of the Bile Duct: Clinical Case Insights and Literature Review. Clin Pract. 2024, 14, 1669–1681. [Google Scholar]

- Sayama, H.; et al. TOKYO criteria 2024 for the assessment of clinical outcomes of endoscopic biliary drainage. Dig Endosc 2024, 36, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, M.; Deutschman, C.S.; Seymour, C.W.; et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016, 315, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Affarah, L.; et al. Still elusive: Developments in the accurate diagnosis of indeterminate biliarystrictures. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2024, 16, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, J.J.; Chen, S.C.; Huang, S.S.; et al. Pulmonary tumor embolism from cholangiocarcinoma: a case report and literature review. Thorac Cancer. 2016, 7, 674–678. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, K.E.; Hamele-Bena, D.; Saqi, A.; Stein, C.A.; Cole, R.P. Pulmonary tumor embolism: a review of the literature. Am J Med. 2003, 115, 228–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2023, 79, 768–828.

- Zhang, D.; et al. Endoscopic treatment of unresectable perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: beyond biliary drainage. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2025, 18, 17562848251328595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, R.S.Y. Endoscopic evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures: Cholangioscopy, endoscopic ultrasound, or both? Dig Endosc. 2024, 36, 778–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ietto, G.; Amico, F.; Pettinato, G.; Iori, V.; Carcano, G. Laparoscopy in Emergency: Why Not? Advantages of Laparoscopy in Major Emergency: A Review. Life (Basel). 2021, 11, 917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yuri, T.; et al. Trousseau’s Syndrome Caused by Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: An Autopsy Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep Oncol. 2014, 7, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfrepper, C.; et al. Predictors for thromboembolism in patients with cholangiocarcinoma. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology 148, 2415–2426. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohaegbulam, K.C.; Koethe, Y.; Fung, A.; Mayo, S.C.; Grossberg, A.J.; Chen, E.Y.; Sharzehi, K.; Kardosh, A.; Farsad, K.; Rocha, F.G.; Thomas, C.R.; Nabavizadeh, N. The multidisciplinary management of cholangiocarcinoma. Epub 2022 Nov 16. Cancer. 2023, 129, 184–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).